1. Introduction

India's incumbent Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, stormed to power with a resounding electoral majority in May 2014. The election manifesto of the party he leads – Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) – emphasized the importance of India following a foreign policy that would position the country's ‘global strategic engagement in a new paradigm and wider canvas’ leading to an ‘economically stronger India’, whose ‘voice is heard in the international fora’.Footnote 1

During his first term, Modi pursued a vigorous foreign policy aiming to expand India's global outreach in a result-oriented fashion. This involved India engaging actively with major and middle powers and articulating its views on multiple global affairs. As Modi prepared to lead his party into another general election during April–May 2019, the BJP manifesto proclaimed: ‘We believe that India's time has come. She is emerging as a power and connecting stakeholders in a multi-polar world. The rise of India is the new reality and we shall play a major role in shaping global agenda in the twenty-first century.’Footnote 2 With Modi being elected for a second term in office, expectations regarding India's prominence in global affairs remain high. Such expectations, though, need to be realistically calibrated in the backdrop of India's external trade policy. Driven by domestic politics, India's trade policy has become conspicuously inward and disengaging, which contrasts with the signals conveyed by its foreign policy.

The dichotomy between India's foreign and trade policy outlooks can be best understood from the following example. Addressing the World Economic Forum's Annual meeting at Davos in January 2018, Prime Minister Modi identified three ‘greatest threats to civilization’: climate change, terrorism, and the backlash against globalization. Expressing concern over countries becoming ‘more and more focused on themselves’, he described the impact as being no ‘less dangerous than climate change or terrorism’. He alluded to ‘forces of protectionism … raising their heads against globalization’ and for ‘reversing’ the process (Chainey, Reference Chainey2018). His defense of economic globalization and criticism of trade protectionism was echoed in a broadly similar message delivered by the Chinese President Xi Jinping the year before at Davos. However, Modi's forceful defense of globalization failed to convince skeptics about India's commitment to the cause (Bradsher, Reference Bradsher2018). The skepticism was vindicated, when within a couple of weeks of the Davos speech, India unveiled a new round of trade protectionism by raising customs tariffs on several items to provide ‘adequate protection to domestic industry’.Footnote 3

The contradiction between what the Prime Minister pitched to the world's most elite gathering of business leaders, and his government's subsequent trade policy actions, reflects the divergence between the progressive and proactive role India wants to play on the global stage, and the character of its trade policy. The former demands a strong and engaging foreign policy, including commitment to addressing major global concerns. India is seen to be doing so on climate change and sustainable development,Footnote 4 but on trade it continues to remain affected by hesitation arising from mindsets shaped by cynicism and resistance to competition. Lack of political support for trade along with unfamiliarity with modern trade issues also contributes to the tendency to disengage.

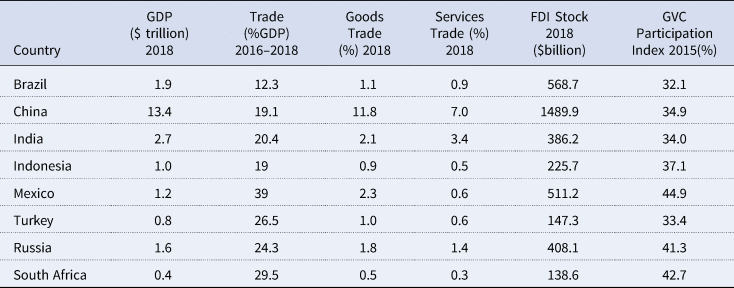

Domestic concerns often influence external policies of large economies. While a long way behind China, India is ahead of most of its peer emerging market economies in economic size, as reflected by GDP (Table 1). It is also ahead of most of the rest – Brazil, Indonesia, Russia, and South Africa – in its share of goods and services trade. It lags some of its peers – Mexico, Turkey, Russia, and South Africa – in the share of overall trade as a proportion of GDP. Higher trade GDP ratios for these economies, notwithstanding their economic sizes being smaller than India's, reflects the greater significance of trade in GDP for the former. India's success in attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) has also been mixed in this regard. While much smaller than China's inward FDI stock, India's inward FDI has been less than those of Brazil, Mexico, and Russia. The character of such FDI has been primarily domestic market seeking, rather than export-oriented (Guha and Ray, Reference Guha and Ray2004; Palit and Nawani, Reference Palit and Nawani2007). India's participation in global supply chains too is among the lowest in the group of economies mentioned in Table 1, underscoring its relatively modest engagement in global cross-border production networks.

Table 1. India and major emerging market economies: domestic market and external integration

Source: Compiled from (a) WTO Member Profiles, www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/org6_e.htm and (b) World Investment Report, UNCTAD, https://unctad.org/en/Pages/DIAE/World%20Investment%20Report/Annex-Tables.aspx.

The above comparisons point to the much greater importance of the domestic economic sectors in spearheading the Indian economy, as opposed to external sectors. For India, trade plays a relatively smaller role in the shaping of its GDP, highlighting the more prominent role of ‘non-trade’ sectors, or the domestic economy, in its GDP. This is particularly similar to China and Brazil, underscoring the pivotal role of the domestic economy in their GDPs. The United States too, has a trade–GDP ratio of only 13.4%, and a much greater non-trade domestic economy. The US, China, India, and Brazil are identical in being large economies with preponderant domestic economies. Understandably, domestic interests and sensitivities are uppermost in various external negotiations they engage in. Occasionally, such interests might not align with greater objectives of their foreign policies, as is evident for India. It is notable, however, that the US and China can command greater geo-strategic influences, certainly far more than India's, notwithstanding adopting trade policies designed for protecting domestic interests that are inconsistent with their foreign policy outreaches.Footnote 5Their ability to command greater geo-strategic influences are characteristic with their identities of being larger ‘powers’ than India. The distinction is not just in terms of their having larger economies, but also much greater shares in global trade, capital flows, production networks, intellectual property, diplomatic engagement, and presence in major forums (e.g. UN Security Council).

This paper probes factors determining the tendency of India's trade policies to turn inward and disengage from trade negotiations. These include the relative lack of competitiveness of its domestic industry compared with several major global economies that have captured large shares of world markets, with low competitiveness being an inevitable outcome of India's economic structure; the absence of influential domestic lobby groups that benefit from trade and can pressurize the government to pursue a liberal trade policy agenda; and, finally, a distinct unfamiliarity and discomfort in dealing with modern trade agreements that address several complex issues. This paper examines all these issues and argues India's quest for greater global strategic influence will be adversely affected by its restrictive trade policies conditioned by these factors.

2. Domestic Competitiveness, Economic Structure and Trade Outlook

Indian industry has mostly discouraged efforts of the country to engage in bilateral and regional free trade agreements (FTAs). The reluctance stems from the realization of its lack of competitiveness in most segments of manufacturing. In the few areas where Indian producers have captured large shares of global markets, such as generic pharmaceutical products, Indian exporters have occasionally lobbied the government to remove certain foreign trade barriers such as in China, where multiple non-tariff barriers (NTBs) constrain access for Indian generic drugs.Footnote 6 Such examples of Indian producers lobbying for greater access for exports are rare with industry hardly indicating active interest in trade negotiations.

Along with the marked reluctance of Indian industry to engage in trade negotiations, the latter have also been discouraged strongly by Indian agriculture producer groups and lobbies. Such groups have resisted India's engagement in various FTAs, including the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), as well as India's bilateral trade negotiations with the US. For large segments of Indian industry and agriculture, relative lack of competitiveness has precipitated disengagement with global trade.

An indication of the state of India's overall domestic competitiveness can be gleaned from various assessments of competitiveness by different global agencies. The World Economic Forum (WEF)'s latest Global Competitiveness Rankings ranks India at 68 among 141 countries. Various indicators reflect specific weaknesses of the Indian economy that adversely influence competitiveness of its producers and exporters (Appendix).

Information and communications technology (ICT) adoption, health, skills, and product and labour markets are indicators of why India ranks among the poorest (Appendix). Some sub-categories of these indicators have direct bearing on production costs and producer competitiveness. India, for example, remains among the more backward of the surveyed countries in all indicators of ICT adoption (Appendix). This is a major hindrance to India's efforts to digitalize economic transactions for households and businesses, as limited and uneven internet penetration restrict development. Greater delay in ICT adoption would hinder digitalization and continue imposing higher costs of doing business for both manufacturing and service industries. With respect to costs of production and their influence on perspectives for foreign trade, other indicators like skills, trade openness, and ease of hiring foreign labour have important implications – India's ranks are low in them all (Appendix). The realization reinforces reluctance of domestic industry and negotiating agencies in India to posturize positively in trade negotiations.

It is important, though, in this context, to look closely at some other aspects of the competitiveness parameters and the impact they have on India's outlook on trade. These include market size, where India is ranked among the highest in the world at 3, following China and the US, and ahead of the rest of the G7 OECD economies, as well as the G20 and its peer group of emerging market economies. The sheer size of the Indian economy – third largest after China and the US in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms – is an indicator of its ‘lure’ as far as other countries are concerned. The realization of this appeal perhaps emboldens India to act tough and be uncompromising in trade negotiations, by resisting pressures for opening up, knowing well that notwithstanding policies that are inward-looking for suiting domestic interests, it would continue to be engaged by other countries that visualize large gains from getting access to a hitherto ‘closed’ Indian market.

2.1 Structural Features and Lack of Competitiveness

The lack of competitiveness of domestic producers in India in manufacturing, and their resultant reluctance to engage with global and regional trade talks, can be traced to the structural characteristics of the Indian economy. Manufacturing contributes around 17% of India's economic output, while services contribute around 54%.Footnote 7 The rapid expansion of the Indian economy since introduction of economic liberalization and market-friendly policies in the early 1990s has been largely driven by services. The current share of manufacturing in India's GDP represents a tiny fractional increase from 15.2% in 1991. The share of services has expanded from 45.2% in 1991 to 54% at present, contradicting the view that economic liberalization would unshackle manufacturing and boost industrial output (Kumar, Reference Kumar, Rai and Palit2018). Services compensated for the almost entire decline in share of agriculture in India's GDP, which dropped from 27.3% in 1991 to 16.3% in 2018.Footnote 8 This structural change, notwithstanding introduction of outward-oriented policies, including lowering of tariffs and liberal conditions for foreign investment, needs to be viewed with respect to an odd fact. Manufacturing has a much larger share in India's foreign trade than services. Indeed, the predominance of services in national output, looked at in conjunction with their lower share in trade, points to the large share of the ‘non-trade’ domestic segment in the GDP, noted earlier.

Is the structural feature unique to India? With respect to its peer economies, as mentioned in the Table 1, there is nothing unusual in services being the predominant contributor to GDP.Footnote 9 However, India is in marked contrast in its share of agriculture in GDP being higher than that of manufacturing. But even with a relatively higher share in the GDP, India's agricultural exports are much less than manufacturing exports, in their relative share to total exports.Footnote 10 This, again, underscores the greater domestic and ‘non-trade’ orientation of the agriculture sector.

2.2 Defensive Posturing in Manufacturing and Agriculture

During 2018, India's merchandise exports to the rest of the world were $325.6 billion, making it the 19th largest merchandise exporter. India's commercial service exports for the same year were US$204.5 billion, just more than 60% of merchandise exports. The share becomes even smaller if imports are added and total merchandise trade is compared with total commercial services trade: for 2018, India's merchandise trade was $836.3 billion compared with commercial services trade of $380 billion, making the latter less than half of the former. More than 60% of India's merchandise trade is manufacturing,Footnote 11 which has significant implications for India's posturing in trade negotiations.

The Indian industry's lukewarm interest to external trade engagement is largely due to the structural characteristic of India's trade. Merchandise trade, particularly manufacturing, is a much greater contributor to India's overall trade compared with services, notwithstanding impressive strides by India in developing strong capacities in ICT and professional services. These trade characteristics have shaped perceptions with which Indian FTA negotiations are identified. These include, in manufacturing, reluctance to lower import tariffs and, in services, excessive focus on obtaining access for Indian IT and other professionals in external markets. Both perceptions have featured prominently in FTAs that India has negotiated, or is currently engaged in, such as with the ASEAN, RCEP,Footnote 12 EU, US, Japan, Korea, Canada, and Australia.

The ‘defensive’ posturing in manufacturing arises from manufacturing imports being much larger than such exports. India depends on large imports of crude oil, notwithstanding strong domestic capacities for refining that have enabled it to export refined petroleum products, which are among its major exports. India also imports several manufactured products, both for final consumption, as well as intermediates for further processing in various supply chains. The reliance on imports has been extensive for facilitating industrial and manufacturing growth since the early years of the current century, a period that saw India's rate of GDP growth rising by more than 7%Footnote 13 (Figure 1). The legacy of controlled and regulated economic policies discouraging scale and innovation by private entrepreneurs continue to force India's widespread dependence on manufacturing imports. On the other hand, consumption has been the main driver of aggregate demand and GDP growth in India, which is unsurprising, as domestic services have expanded fast. Sectors such as hospitality, tourism, transport, retail, education, and entertainment have grown rapidly, necessitating consumer goods imports, such as smartphones, primarily from China, without which India's mobile phone revolution could not have been sustained (Palit, Reference Palit2012).

Figure 1. India's non-oil exports, imports, and trade balance ($’000).

Source: Compiled from Handbook of Statistics on the Indian Economy, Reserve Bank of India.

India's GDP growth of around 7% during the last couple of decades has been accompanied by rising demand for non-oil imports (Figure 1), accentuating the difference between such imports and exports, and enlarging the trade deficit. Notwithstanding several imports being necessary, they have resulted in various segments of the Indian industry demanding greater protection. India's FTAs with ASEAN, Japan, and Korea specifically have been held responsible for accelerating imports. The demands for greater protection, however, have conveniently overlooked two facts: (a) the imports have maintained both India's consumption demand and industrial growth and (b) they would have been far less had India developed broad-based local manufacturing capacities as have several economies in Asia-Pacific, beginning with Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, and extending later to Thailand, Malaysia, China, and Vietnam. The demands also ignore India's retention of the flexibility to impose tariffs on several electronic items by not being a part of the second phase of the WTO's Information Technology Agreement (ITA),Footnote 14 and that India's tariffs are higher than most of its peer economies (Table 2).Footnote 15

Table 2. Applied and bound tariffs for India and other major emerging market economies (%)

Source: Compiled from Member Tariff Profiles in WTO.

India's heavy reliance on a variety of imports due to lack of adequate broad-based indigenous manufacturing capacities will continue until it develops requisite large scales for making the imported products at home. Doing so presupposes enabling business conditions. Absence of such conditions would inhibit growth of domestic capacities and continue to force reliance on imports perpetuating a vicious cycle of imperfections and dependencies.

Unfavourable business conditions adversely affect efficiencies and competitiveness of Indian producers making them uncompetitive, both in the domestic market against imports, as well as in most overseas markets, against competing exports. Notwithstanding significant developments such as introduction of a national Goods and Services Tax (GST) structure integrating indirect taxes on goods and services into a composite national space and facilitating easier movement of goods among states within India through digital clearance mechanisms,Footnote 16 several business conditions remain adverse, particularly those reflected in the Appendix 1. Nonetheless, there are industries, for example gems and jewellery, pharmaceuticals, and leather, where Indian manufacturers have penetrated major OECD markets such as that of the US and Europe. In these markets, their access, to some extent, has also been facilitated by non-reciprocal preferential schemes such as the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP).Footnote 17 The relative lack of competitiveness of Indian producers, particularly manufacturers, remains a problem for India when negotiating FTAs. Fear that the Indian market would be swamped by cheaper and more competitive goods from other countries, particularly China, has been a compelling factor refraining India from joining the RCEP.

More on India's disengagement from the RCEP and postures in FTAs are discussed in the next section. However, at this stage it is pertinent to reflect on the impact of lack of competitiveness on India's reluctance to withdraw protection from agriculture as well. India's tariffs on agriculture are among the highest in its peer group of economies (Table 2), particularly the high bound rates, which enable it to raise the applied tariffs to much higher levels in the event of a surge in agricultural imports. The ostensible reason behind such protection is to safeguard domestic agriculture and food producing lobbies, who have dominated India's huge domestic market due to lack of external competition, and by selling products at assured procurement prices fixed by the government. The pressure on trade negotiators not to open up the agriculture sector, such as cereals, beverages, oilseeds, and dairy, have been high, compounding India's defensive postures at FTA talks, leading to eventual disengagement, such as with the RCEP.

India's ‘domestic’ focus in trade talks, preponderance of non-trade sectors in its economy, and the resultant impact on competitiveness for export-oriented production are evident from the country's lack of success in using Special Economic Zones (SEZs) to enhance exports. Aiming to capitalize on China's success in expanding exports and attracting export-oriented FDI through SEZs, India introduced the Special Economic Zones Act of 2005.Footnote 18 More than 250 such zones function in the country now.Footnote 19 However, their contribution to exports has hardly been significant.Footnote 20 Indeed, the SEZs have also been unsuccessful in attracting large-scale export-oriented FDI. This is evident from the industrial concentration of FDI inflows in India. Services (including financial and banking services), computer software and hardware, telecom, trading, construction, and hotels and tourism, account for around half of India's total inward FDI stock.Footnote 21 These are prominently domestic market-focused sectors, highlighting the inclination of incoming FDI to be primarily of the market-seeking variety, as mentioned earlier in the paper, for capitalizing the large customer base that India provides. If SEZs had indeed been able to offer business conditions enabling producers to overcome India's lack of competitiveness, they clearly would have encouraged more FDI inflows into export-oriented sectors.

3. Absence of Domestic Pro-Trade Constituencies

Notwithstanding a burst of economic reforms precipitated by the balance of payments (BOP) crisis in 1991, India has been a hesitant liberalizer. After the first rounds of deregulation and decontrol manifesting through major changes in industrial and trade policies, the pace of reforms has been at best incremental, largely due to several domestic constituencies remaining unconvinced about the benefits of market-friendly policies and greater integration with the world economy.

Since 1991, deep and far-reaching economic reforms in India have happened mostly on occasions of noticeable economic slowdown. These include the early years of the 2000s, when annual GDP growth dropped to as low as 3.8%, and the government led by Prime Minister Vajpayee significantly liberalized foreign investment policies and introduced major changes to the financial and fiscal management of the country. A subsequent example of economic slowdown triggering reforms was in September 2012 when, faced with industrial stagnation and the prospect of downgrade by credit rating agencies, several reforms were announced. The Modi government has not been an exception in this regard. Soon after it was re-elected to office in May 2019, deceleration of economic growth to around 5% and negative industrial sentiments generated by poor employment prospects and depressed domestic demand, led to it announcing several major policies. These included liberalizing tax regimes for foreign portfolio investors, easier sourcing norms for single-brand retail, fiscal incentives for exporters, and a cut in corporate income tax rates for improving competitiveness of Indian businesses.Footnote 22 The deep economic contraction following the outbreak of COVID19 has been utilized by the government for announcing far-reaching reforms in agriculture marketing and labour laws.

Difficult economic situations, like those illustrated above, have clearly been taken as opportunities by incumbent governments to introduce significant reforms and minimize the adverse political implications of such situations (Palit, Reference Palit2012). This indicates that notwithstanding official pronouncements to the contrary, pro-market and pro-external trade constituencies in India are limited. The latter are grossly outnumbered by the vociferous majority opposed to outward-oriented policies.

Much of the business and industrial lobbying in India on trade, such as by the Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers (SIAM) or the country's largest dairy cooperative group, Amul,Footnote 23 has been defensive with the goal of retaining trade barriers.Footnote 24 The defensive agenda is hardly surprising given the concerns over competitiveness reflecting in market access deliberations for both manufacturing and agriculture, as discussed in the previous section. The tendency has acquired formidable proportions over the years and has been precipitating India's disengagement from FTAs. The situation could have been different had influential pro-trade lobbies championed greater external engagement. This could have partly countered the protective impulses generated by competitiveness concerns.

India's withdrawal from the RCEP in November 2019 is the most recent example of disengagement decisively influenced by anti-trade constituencies (Palit, Reference Palit2019). Swadeshi Jagran Manch (SJM) – a group with nationalist views on economic policy, including strongly negative views on India's engagement in FTAs – began a countrywide agitation from mid-October 2019 on India's decision to join the RCEP. The timing of the agitation was significant with the RCEP talks scheduled to conclude at the ASEAN Summit in Bangkok from 31 October to 4 November 2019. After prolonged hesitation and defensive posturing for nearly seven years, India was finally looking to agree to the deal. The significance of the protests was not just on timing. The SJM is affiliated to the politically influential Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) – the main proponent of the nationalist pro-Hindu political and economic ideologies in India, enjoying strong and intrinsic links with the Modi government.Footnote 25 Eventually, the SJM, backed by influential domestic industry lobbies like Amul, who whipped up import phobia, was successful in preventing India from joining the RCEP. The political cost of committing to the RCEP would have been substantial for the Modi government if it had committed to the pact notwithstanding opposition from RSS affiliates such as the SJM. However, by backing out, the government failed to make use of the ‘enabling' context of an economic slowdown threatening to assume major proportions for pushing a forward-looking trade agenda. The slowdown could've been used by the government to justify RCEP by emphasizing the ‘necessity’ for encouraging exports and attracting export-inducing investments for reviving economic growth, for which, lowering tariffs were a required trade off!

Unwillingness to engage in trade negotiations reflects a change in India's attitude to external engagement that has become increasingly noticeable over the last few years. This change contrasts with the role that India played in deliberations at the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT) during the decades of 1980s and 1990s leading to establishment of the WTO. While emphasizing concerns of developing countries over implementation issues at the Uruguay Round, India cautiously supported trade liberalization in the early years of the WTO, mindful of its own still early transition from a largely protected inward-looking economy (Ray, 2011). India's most proactive role at the WTO was probably the substantive contributions it made to shaping of the Doha Development Agenda (DDA) by promoting developmental multilateralism (Efstathopoulos and Kelly, Reference Efstathopoulos and Kelly2014). During the first decade of the current century, India also made efforts to engage proactively in FTAs, including those with its neighbours in South Asia, ASEAN, EU, and major Asia-Pacific economies like Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Malaysia. Notwithstanding long negotiations, these FTAs were concluded and are operational except for the one with EU. However, most of India's early FTAs, particularly those with immediate neighbours – Afghanistan, Bhutan, Nepal, Sri Lanka – were motivated largely by non-economic, strategic factors (Wignaraja, Reference Wignaraja2011).Footnote 26

During the last decade, India became noticeably more reluctant to engage in trade negotiations. During its first term in office (2014–2019), the Modi government stalled FTA negotiations with EU, as well as with Australia and Canada, despite making progress on all. The RCEP was the only FTA with which India stayed engaged, but with considerable cynicism, and eventually withdrew. It is notable that the disengagement with FTAs comes at a time when India's foreign policy has become markedly robust. It is strange that notwithstanding the warm outreach on foreign policy, trade engagement has not only lagged behind, but has displayed a negative trajectory.

Whether it be the frustration over the lack of movement on DDA at the WTO, or the skepticism over economic globalization and outward-oriented policies following the global financial crisis of 2008, India's disengagement from FTAs is part of an overall disinclination to liberalize critical sectors and industries, such as telecom, insurance, banking, retail, and agriculture. Even before the Modi government came to power, the aversion was visible in the political arena with some regional parties, including those supporting the Congress Party and Manmohan Singh-led government, criticizing decisions to allow FDI in domestic retail.Footnote 27 The BJP, which was a proponent of FDI in domestic retail during its tenure in government in the early years of the century, changed position and subscribed to an anti-FDI view. With general elections to be held within less than two years, the BJP did not want to antagonize the vast number of small retailers, many belonging to the informal sector, whose votes could have been significant in deciding the electoral outcome.

Since returning to power in 2014, the BJP has taken incremental steps in liberalizing FDI, including in retail. The incrementalism, while driven by economic pragmatism, has not been welcomed across-the-board. Political parties – small and large alike – have publicly shied away from endorsing such policies in their efforts to hold on to specific domestic constituencies like informal retail traders, labour unions, and farmers. The tendency to hesitate on reforms and refrain from political commitment has been noted not just for coalition governments, where regional parties commanded weights far in excess of their vote shares given their ‘importance’ in mustering numerical majority in the Parliament, and where small domestic lobbies backed by local political parties staged strong protests on FTA talks,Footnote 28 as seen with the Manmohan-Singh government. Even the mighty BJP under Modi, elected by large popular mandates, has balked at the prospect of agitating core constituencies by encouraging imports and opening-up to the rest of the world – the withdrawal from RCEP being the most relevant example!

Reservations in engaging with FTAs, arising from the disinclination to open up the economy and adopt market-oriented policies, symbolize a strong polarization between opinions favouring an inward-looking, domestic priority focused character in India's economic growth strategy, and those championing aggressive market-based reforms, many of which entail greater integration with the world economy. The BJP's ascent to power has further pushed back the latter group. Indeed, the fact that Prime Minister Vajpayee's BJP government during the early years of the current century was able to push through wide-ranging liberal FDI policies, despite having much lower strength in the Parliament compared with the current Modi government, draws attention to whether the latter, characteristically, has become a BJP far less comfortable with globalization and market-centric economic policies than its predecessor. The drift from the market to greater state management of the economy is evident from the widening of scope and coverage of welfare-centric state subsidy programmes, which began being implemented during the Manmohan Singh government. Ambitious welfare programmes, such as the national food security programme aiming to provide food grain to around 800 million Indians at subsidized rates, has raised questions over whether it will result in India overstepping the ceiling on agricultural subsidies under the Agreement on Agriculture (AoA) at the WTO.Footnote 29 The nearly unbridgeable gap between pro-market, outward-oriented policy views and the current, more influential inward-looking policy proponents – such as the SJM – marks fast dilution of pro-trade constituencies in India.

Unlike the US, where interests of agricultural lobbies have encouraged negotiators to hunt for market access in other countries, or in China, where trade policy emphasis draws strength from efforts to capitalize comparative advantages of manufacturer exporters, Indian exporters, crippled by lack of competitiveness and limited support at home, have failed to positively influence trade negotiations. Exports, and trade as such, lack champions espousing their cause, largely due to India's policy preoccupation with the domestic economy. Defensive lobbying for retaining import protection in FTA negotiations for safeguarding domestic interests has deflected Indian negotiating focus from the goal of securing greater access for exports.Footnote 30 Pro-protection lobbies, such as those in auto components and dairy, have prevailed over less influential industry groups with offensive export interests.

Organized lobbies, can indeed, make considerable difference to negotiating outcomes, as evident from foreign automobile assemblers (e.g. Suzuki, Toyota, Hyundai) based in India lobbying for tariff cuts in FTAs for intermediate imports for reducing production costs, while at the same time demanding higher import duties on finished cars.Footnote 31 Demands for lower tariffs on intermediate imports can be linked to the FDI in the Indian automobile industry, where foreign assemblers seek duty cuts for efficiency across supply chains. One of the major industrial supply chains where there hardly has been any demand for greater protection is pharmaceuticals. Indian industry depends heavily on China for sourcing of intermediates such as bulk drugs and active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in its large-scale manufacture and export of generic formulations. Given India's large global exports of generic drugs and the reliance on imported inputs, the industry has never demanded tariff protection on either imported inputs or local sales. However, pharmaceuticals are a rare example. In most other industries, the supply chain characteristics, in terms of domestic contribution to exports, clearly highlight the urge for protection. In primary products such as agriculture and food, the domestic contribution, measured in terms of domestic value added to exports, is remarkably high at more than 90%, while for manufacturing and services, the shares are more than 70% and 90%, respectively.Footnote 32 In Indian agriculture and service exports, the direct domestic value addition of the exporting industry is significantly higher than those by other domestic industries, reflecting lower diversification of supply chains domestically. The concomitant protectiveness of these sectors from imports as a result of the heavy domestic orientation is clearly understandable, for example with the dairy industry, as it is for several segments of manufacturing, barring significant exceptions like pharmaceuticals!

More FDI and greater integration with global supply chains in other industries might, over time, witness greater lobbying on India reducing import tariffs on intermediate goods, along with lobbying for increasing market access for its exports, if the incoming foreign investments are more export-inducing as opposed to being entirely domestic market-oriented.Footnote 33 Greater integration of Indian industries in value chains run and managed by global firms should infuse greater export-oriented investments in India, and also produce more pro-export domestic constituencies. At the same time, more new generation industries exploiting India's comparative advantages in knowledge-intensive services (e.g. IT and IT-enabled products and services), such as the National Association of Software and Service Companies (NASSCOM), are expected to develop greater lobbying influence in FTA negotiations.

The combination of comparative advantage in services, and greater presence of foreign businesses and their affiliates in the country, might, in the foreseeable future, see India employing strategies that are more constructive in FTAs. However, it must be noted that industry bodies like NASSCOM, are yet to gain as much political traction as other lobbies with defensive interests in manufacturing and agriculture. The political headwind is firmly in favour of the latter groups and is unlikely to change substantively in the medium term.

The challenge of obtaining political legitimacy remains fundamental to all offensive trade and export lobbying efforts. The challenge is particularly serious in the current context, where the ruling BJP and the Modi government have prospered and are sustained by deep-rooted support from groups that are inherently nationalist and inward looking. Selling a positive trade agenda to these constituencies is an extremely difficult task as the struggle with RCEP has revealed.

4. Discomfort with New Generation Trade Agreements

Since the inception of the WTO, India has engaged proactively in trade talks both at the WTO, as well as outside of it. At the WTO, India's emphasis has primarily been on the implementation of the DDA, in pursuing special & differential (S&D) treatment for developing countries. The WTO's success on the DDA has been limited, except for implementation of the Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA).Footnote 34

As such, much of India's negotiating energy at the WTO has been deployed on traditional trade issues of market access in agriculture and non-agricultural products. This has also been the focus in most of its early FTAs. FTAs with South Asian neighbours, such as Afghanistan, Bhutan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, as well as with the MERCOSUR, were largely motivated by strategic factors, as mentioned earlier. These FTAs focused largely on tariffs and rules of origin and were limited in their coverage of market access and the scope of other trade issues, such as services, investment, and intellectual property (IP). Over time, India's FTAs have become more comprehensive and broad-based by including modern trade issues such as services, investment, competition, government procurement, and IP, which have featured in India's FTAs with Singapore, Malaysia, Japan, Korea, and ASEAN.

Notwithstanding more new-generation and typically ‘WTO plus’Footnote 35 issues in its later FTAs, the scope of these issues in the latter are hardly as deep as they are in standard US and EU FTAs, or in contemporary mega-FTAs like the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). India's FTAs have limited content on WTO plus issues due to India's discomfort in negotiating and discussing these subjects. Investment and competition policy, for example, despite figuring at the WTO, are hardly discussed at WTO at as much length as other traditional subjects. India's engagement at the WTO has been primarily on the DDA, where ‘new generation’ trade issues are mostly absent. Its negotiating discomfort, naturally, enhances when FTA partners expand the scope of the discussions to include issues that are relatively under-discussed at the WTO, like financial services, state owned enterprises (SOEs), environment, and labour standards. India's uneasiness in negotiating these issues is pronounced due to its unfamiliarity with most of these subjects, which again is due to excessive preoccupation with traditional trade issues such as tariffs both at the WTO and in FTAs. The discomfort is also because market access commitments on most of these subjects entail changes in ‘behind the border’ domestic regulations, involving political complications.

One of the most illustrative examples of India's discomfort in taking part in trade talks on new-generation trade issues is its refusal to join the multi-country talks involving almost half of WTO's members on global ecommerce rules. Launched at the annual World Leaders’ meeting of the World Economic Forum (WEF) at Davos on 25 January 2019, the talks include India's peer emerging market economies (e.g. Brazil, China, Mexico, Nigeria, Russia, Turkey), along with low-income economies such as Lao and Myanmar, aiming to ‘commence WTO negotiations on trade-related aspects of electronic commerce’ for a ‘high standard outcome that builds on existing WTO agreements and frameworks with the participation of as many WTO Members as possible’.Footnote 36 India has also decided to stay away from the ‘Osaka Declaration on Digital Economy’ backed by almost all G20 members at the latest Osaka Summit of the G20 during from 28–29 June 2019.Footnote 37

The large number of countries agreeing to commence ecommerce talks at the WTO and the movement on establishing regulations for the global digital economy set off by the G20 point to the discussion on ecommerce and digital trade rules as no longer representing the typical ‘North–South Divide’ in global trade. India has often alluded to such a divide in global trade issues at the WTO, while presenting an alternative perspective from the South. However, the South itself now looks fractured on the subject with many developing countries willing to participate in these talks, even if India and some of the other developing countries (e.g. South Africa, Indonesia) are not. Even on continuation of the WTO's moratorium on not imposing taxes on cross-border electronic transmissions, the fracture is evident among India's peers. While India and South Africa have steadfastly opposed the moratorium, Indonesia has proposed inclusion of downloaded electronic content in the moratorium.Footnote 38

India's refusal to join the global ecommerce talks taking place outside the WTO is again, primarily, a result of its discomfort in negotiating digital trade rules. The discomfort, apart from the obvious issue of lack of negotiating capacity, also arises from the apprehension that by joining the talks it would have little option other than relenting to a rules agenda driven by offensive interests of the world's largest ecommerce businesses from the US, Europe, and China. The disengagement also reflects influence of sentiments created by a strong sense of inward-looking protectionism, contributed to by the paranoia over competitiveness and lack of pro-trade lobbies. These further resonate in decisions to tightly regulate cross-border digital trade flows by proposing measures to localize user data and their close surveillance.

The disengagement, as expected, is isolating India, both in the WTO, as well as in major global forums such as the G20. The ground on which India is disengaging – S&D treatment for developing countries – is unlikely to receive substantial support from many among the community of developing countries whose concerns it reportedly claims to address. In fact, it runs the risk of distancing itself on trade, not only from major powers, but also from its core fraternity of developing and economically backward countries.

Discomfort with new generation trade issues has also affected India's trade negotiations with the EU and the US. India's discomfort with investment rules, particularly investor–state dispute settlement (ISDS)Footnote 39 rules, SOE reforms, and data security, remain important impediments in moving ahead on these trade talks. Its reluctance to discuss ISDS is due to it being taken to arbitration on multiple occasions by foreign investors by invoking bilateral investment treaties with other countries.Footnote 40 It is now refraining from ratifying most of these treaties and proposing to restructure them in line with regulations giving it greater flexibility in avoiding arbitrations. SOEs – in spite of ongoing efforts to modernize and privatize – remain prominent economic actors in India, in key sectors such as banking, energy, aviation, railways, and heavy industry. The historical legacy of the prominence of SOEs in the domestic economy, somewhat like China, has been difficult to dispense given the mutually reinforcing system of incentives SOEs create, where enterprises and select groups of domestic producers benefit from well-defined buyer–seller relationships. The relationships create perverse disincentives for avoiding reforms, particularly through FTAs, where foreign businesses demand access to domestic turfs like state procurement. And finally, the inability to ensure greater security for personal data, along with optimization of revenues from the great amount of digital data that India can generate, has held it back from proceeding further with the EU and US on digital trade issues. The EU's notification of General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) has made progress on data issues more challenging as EU businesses would find it difficult to engage with India unless its domestic data laws align with the EU standards. On the other hand, India's trade talks with the US on a bilateral deal have been affected by contrasting positions on data security accentuated by India's purported thrust on data localization (Desai, Reference Desai2019).

4. Final Thoughts

This paper argues India's quest for becoming a country whose ‘voice is heard in the international fora’ contradicts with its external trade policy. The trade policy has failed to become engaging, result-oriented, and economically meaningful. With global geo-strategic influence – as gleaned from a country's contribution to shaping critical global narratives – being a function of its economic progress, a low-profile disengaging trade policy is counterproductive to India's aspirations. At the same time, it is also important to reflect on whether the foreign policy has become overtly engaging, by positing India to play a role in global affairs, which is not commensurate with its domestic capacities and outlook on trade. Indeed, India's recent policy initiative of collaborating with Japan and Australia to restructure regional supply chainsFootnote 41 by drawing them out of China must be realistically viewed in the light of India's internal conditions suitable for hosting such investments. The geopolitical push behind the multi-country initiative might again, fall short of expectations, if India is unsuccessful in curbing domestic protectionist tendencies.

From a broader international perspective, there are examples of prominently nationalist tendencies beginning to decisively fashion trade policies around the world. The US is the most significant instance. The Brexit movement in the UK is yet another. However, the US and UK examples are contrasted by the greater proclivity shown by the UK to engage in FTAs following its formal separation from the EU. Among India's peer economies, such as Brazil, Indonesia, and South Africa, notwithstanding the emergence of nationalist narratives, trade engagement has not meant as much dissociation from FTAs, as it has for India. Even the US under President Trump has continued talking trade with partners, albeit for refashioning trade deals in a manner more conducive for maximization of American interests. For India, however, the dissociation and disengagement from FTAs has been far more noticeable and exhaustive. Indeed, India’ withdrawal from RCEP, and its reservations on engaging with partner countries on trade, has caused significant disappointment among the latter over India's willingness to work closely on trade. From a foreign policy perspective, the current global cynicism over India's trade posturing could be a major obstacle in expanding India's geo-strategic influence.

The opportunity for turning around the trade policy does exist. Taking a positive trade agenda to domestic constituencies by highlighting its economic and strategic benefits should work, albeit in a gradual fashion. The Modi government is well-positioned to do so given its political legitimacy. Whether it would actually do so depends significantly on the long-term political benefits it envisages. Currently, a forward-looking and outward-oriented trade policy is considered damaging for India's national interests. This is clearly a result of preponderance of such views within the policy establishment influencing trade policy decisions. Changing the perspective presupposes changes in political vision and economic outlook. Otherwise, driven by domestic politics, India's trade policy would remain fundamentally disengaging and antithetical to the country's global ambitions.

Appendix

India: Global Competitiveness Index Ranks and Indicators