Introduction

Frontal sinus outflow tract restenosis constitutes a significant problem following endoscopic frontal sinusotomy.Reference Orlandi and Knight1 The concept of frontal sinus stenting has long been advocated in the prevention of post-operative scarring and narrowing of the neo-ostia.Reference Freeman and Blom2 This technical note illustrates our experience of using simple and cost-effective frontal sinus stents made out of modified silicone rubber nasal splints.

Technical description

Endoscopic frontal sinusotomy (a Draf II/III procedure) is performed in a standard fashion, preserving mucosa where possible. At the end of the procedure, the diameter of the frontal sinus opening should be the maximum that the patient's anatomy allows.

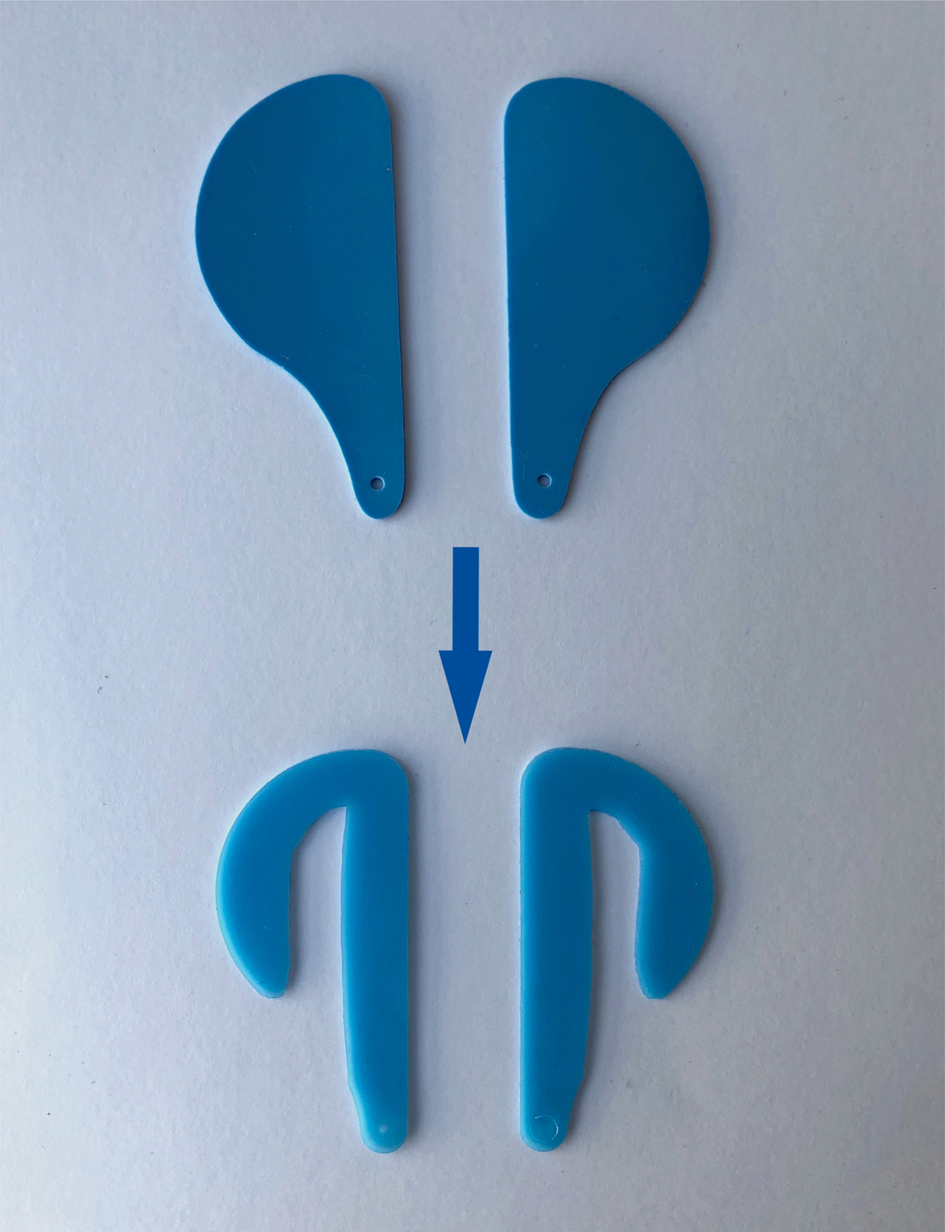

Two silicone rubber nasal splints (Medasil Surgical, Leeds, UK) are cut to shape to form the stents (Figure 1). The stents are introduced endonasally and advanced into the frontal sinuses. The winged end of each stent is retained within the contralateral frontal sinus, thereby intersecting at the ‘frontal T’ (Figure 2). The lower ends of the stents are secured to the anterior nasal septum using a size 2–0 silk suture.

Fig. 1. Preparation of the stents using two silicone rubber nasal splints (Medasil Surgical).

Fig. 2. Endoscopic view of the stents placed within the frontal sinuses. The winged ends of the stents intersect at the ‘frontal T’.

Immediately after surgery, the patient is advised to use nasal irrigation four times a day and apply topical nasal steroids twice a day. The stents are removed during a subsequent follow-up visit to the out-patient clinic after a minimum period of four weeks. The senior author does not routinely undertake post-operative nasal debridement.

Discussion

Effective surgical management of medically refractory chronic rhinosinusitis relies on the establishment of patent and durable openings into the paranasal sinuses, to allow for the efficient drainage of sinus secretions and delivery of topical therapies.Reference Kohanski, Toskala and Kennedy3

Given the idiosyncrasies of the frontal sinus outflow tract anatomy, surgery on the frontal sinuses is notoriously difficult and remains a challenge for the endoscopic sinus surgeon. Instrumentation may lead to iatrogenic scarring and adhesions, with resulting sinus outflow tract re-occlusion and recurrence of frontal sinus disease.Reference Wormald4 Failure rates of up to one-third, necessitating revision surgery, have been reported in some case series.Reference Ting, Wu and Metson5,Reference Samaha, Cosenza and Metson6

Over the years, frontal sinus stents made from a variety of materials have been developed and utilised to address this problem. Their use offers a method of draining the frontal sinuses and maintaining the patency of the outflow tract. Indications for using them include: a diameter of the opening of less than 5 mm, purulence, osteitic bone, granulomatous inflammation due to vasculitis, stenosis from previously failed sinus surgery, middle turbinate lateralisation, and denuded mucosa within the frontal recess. Evidence from the literature suggests that soft materials such as Silastic are considered superior in terms of scarring prevention and improved patency rates, compared to more rigid tubing. However, there remains a lack of consensus on the recommended duration of stenting.Reference O'Brien, Lal and Hwang7

The current technique offers a significant advantage over commercially available stents. Soft silicone rubber nasal splints are inexpensive and universally available. Furthermore, the technique is well tolerated by patients, relatively simple to reproduce and can be performed safely by the experienced endoscopic sinus surgeon.

Upon removal of the stents, the winged ends carry with them a layer of crust and debris from within the frontal sinuses, while the drainage pathway has already begun to mucosalise. The senior author has been using the current method of frontal sinus stenting for a number of years and reports no complications as a result.

Competing interests

None declared