Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 December 2005

Objective: To identify factors associated with internal medicine interns' self-assessed competency in death pronouncement and to evaluate the effectiveness of a 10-minute death pronouncement module and pocket card guidelines.

Methods: In June 2003 at the Birmingham VAMC, Alabama, 48 internal medicine interns completed a survey of medical school education, training, and experience in death pronouncement and a self-assessment of death pronouncement competency. In September 2003, 33 of the 48 interns completed a follow-up training/education survey and rated their post-intervention competency. Using chi-square and paired t-tests, we identified factors associated with variations among baseline and post-intervention variables and examined pre-post changes in self-assessed competency levels.

Results: At baseline, less than 30% of the interns had medical school instruction in the process of death pronouncement. More than 70% reported needing basic instruction/close supervision. Post-intervention, close to 90% interns needed minimal or no assistance. Over 50% reported using pocket card guidelines. We found significant pre-post increases in mean rankings in each of the 5 self-assessed competencies (p < .001). Factors associated with differences in baseline and post-intervention assessments included medical school training/experience and use of the pocket card guidelines.

Significance of results: When interns began training, most had no instruction in death pronouncement and felt unprepared for this task. With brief instruction, pocket card guidelines, and 3-months experience, the majority of interns reported needing minimal/no assistance in pronouncing death. A larger sample from multiple sites is needed to confirm these findings.

When a person dies there are statutory and regulatory processes for attesting that death has occurred and for documenting the death on the medical record and death certificate. The prompt and accurate documentation of death and completion of the death certificate is important to surviving families who need these documents as they work through the financial, regulatory, insurance, and benefit issues arising after the death of a loved one. For bereaved families, however, the medical acts that occur at the time of death can have implications that transcend legality. Waiting for a physician to examine and confirm that a loved one has died is an emotion-laden experience. How this information is relayed to the surviving family and how family bereavement is managed in the time immediately following death are important components of the death pronouncement process.

In teaching hospitals today, the role of death pronouncement is typically relegated to interns. The more senior residents routinely assign death pronouncement work to their intern who will be almost exclusively responsible for this work. Because current regulations stipulate that only the physician has the authority to fulfill this task, interns cannot pass off such work to medical students. Typically, interns receive no instruction in death pronouncement and have to turn to senior residents or nurses as their only source of information. Performing this task alone and without supervision can be an anxiety-provoking and distressing event for interns, especially when there is no standard process or protocol for them to follow (Lerman, 2003; Marchard & Kushner, 2004). Although medical educators have developed death-pronouncement guidelines and programs to train residents in the art and science of death pronouncement (Schmidt et al., 1992; Marshall & Jones, 1993; Marchard et al., 1998; Marchard & Kushner, 2004), and researchers have examined the practice and protocol of death pronouncement (Magrane et al., 1997; Ellison & Ptacek, 2002), to our knowledge no one has conducted research on interns' perceptions of their readiness to engage in the death pronouncement process or evaluated the impact of a death pronouncement educational intervention on self-assessed competency in this area. While Pollack (1999) reported on the effectiveness of a lecture format for instructing interns on death notification, the process of death pronouncement was not specifically addressed (Pollack, 1999). The purpose of this study was to identify factors associated with self-assessed death-pronouncement competency and to determine the effect of a short educational program and pocket card guidelines on post-intervention self-assessment competency in first-year residents in an urban teaching hospital.

IRB approval was obtained from VAMC for this study. During orientation before beginning clinical duties at the Birmingham VAMC in Birmingham, Alabama in June of 2003, 48 interns (84% white and 63% male) completed an anonymous survey of their medical school experience and training in death pronouncement (See Survey 1 in Appendix). For the purpose of this study, the elements of medical school death pronouncement experience/training were delineated as having pronouncement instruction as a medical student, having accompanied a resident for death pronouncement, and having accompanied a resident to meet the bereaved family. The frequency of exposure to death pronouncement procedures and meeting with bereaved family members was also taken into account.

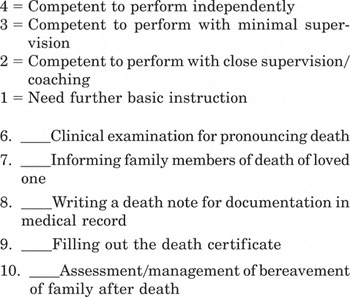

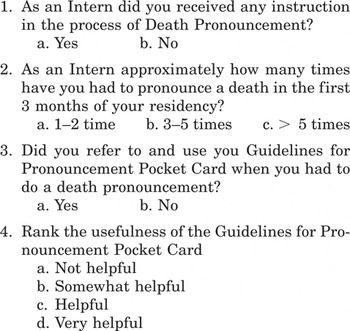

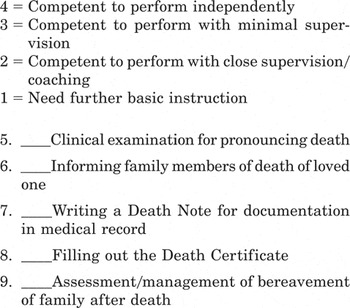

In Survey 1 the interns were also asked to rate their pre-intervention competency in 5 components of the death pronouncement process. Three of the components focused on the procedural skills of clinical examination for pronouncing death, writing the death note, and filling in the death certificate, and two of the components focused on the interpersonal skills of informing the family of death and assessing/managing the family bereavement in the time immediately after death. Rating was on a scale of 1–4 (1 = need further instruction; 2 = need close supervision; 3 = need minimal supervision; 4 = need no supervision). For purposes of bivariate analysis, the rating scale was dichotomized into 1 = need instruction or close supervision and 2 = need minimal or no supervision.

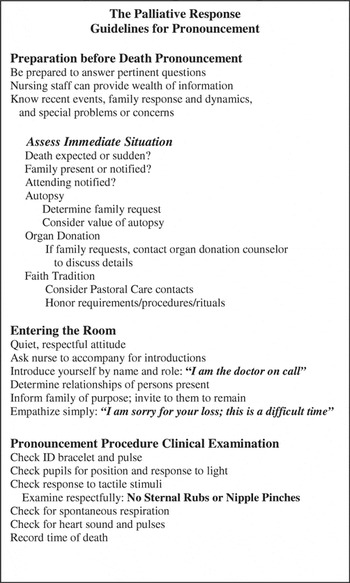

The educational intervention consisted of a 10-minute presentation during the orientation of the internal medicine interns before beginning clinical rotations. The presentation delineated the components of the death pronouncement process using materials developed for the educational component of the Safe Harbor Palliative Care Project, an end-of-life care initiative at the Birmingham VAMC (Bailey, 2003). At the conclusion of the presentation, the interns were given a Guideline for Death Pronouncement Pocket Card summarizing the educational material (see Pocket Card in Appendix).

Three months later in September 2003, 33 of the 48 interns completed a second voluntary and anonymous 9-item survey regarding their experiences with death pronouncement as an intern (see Survey 2 in Appendix). Chief medical residents administered the surveys during the routine quarterly review. The investigators were blinded to which residents had completed the survey that contained no individual identifying information. Residency experience/training was defined as having pronouncement instruction as an intern, pronouncing death during the first 3 months of residency, and referring to guidelines for pronouncement on the pocket card. The frequency of death pronouncement and the perceived helpfulness of the pocket card guidelines were also considered. In Survey 2, interns also completed a post-intervention self-assessment of competency in the same 5 areas of the death pronouncement process examined in Survey 1.

We used descriptive statistics to determine the frequency of medical school and interns' death pronouncement experience and training. Using chi square, we examined differences among the components of death pronouncement experience/training in medical school and as an intern. We also looked at the association between medical school and intern experience and self-assessed death pronouncement competencies. We performed paired t-tests to examine differences in mean ratings on self-assessed competencies and to identify pre/post-intervention differences.

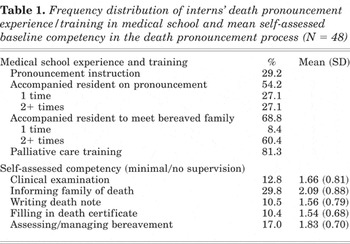

The frequency of medical school death pronouncement education/training is found in Table 1. Death pronouncement instruction was significantly less frequent than palliative care training in medical school (P = .033). While over 80% of interns reported receiving prior training in palliative care and over 50% had accompanied a resident to pronounce death or to inform the family of death, less than 30% of those surveyed reported formal instruction in the process of death pronouncement as a medical student. All 14 participants with medical school instruction in death pronouncement also had palliative care training.

Frequency distribution of interns' death pronouncement experience/training in medical school and mean self-assessed baseline competency in the death pronouncement process (N = 48)

In the self-assessment section of Survey 1, less than 20% of participants indicated they could function with minimal or no instruction/supervision in the clinical examination for pronouncing death, writing the death note, filling in the death certificate, or assessing/managing family bereavement. Less than 30% felt competent to inform the family of death without assistance or direction (Table 1).

Mean ratings for Survey 1 self-assessed death pronouncement competencies are in Table 1. On a scale of 1–4, they ranged from 1.54 for filling in the death certificate to 2.09 for informing family of death. Using t-tests, we found that mean competency ratings for the 3 procedural components of the death pronouncement process were not significantly different from one another. The mean rating for informing family of death was significantly higher than those for the clinical examination for pronouncing death (p = .003), writing the death note (p = .000), filling out death certificate (p = .001), and assessing/managing bereavement after death (p = .017). In addition, the competency rating for assessing/managing family bereavement was significantly higher than those for writing the death note (p = .027), and filling in the death certificate (p = .041).

The association between medical school education/training and self-assessed death pronouncement competencies is summarized in Table 1. Death pronouncement instruction in medical school was positively associated with self-assessed competency in writing the death note (p = .008), filling out the death certificate (p = .008), and assessing/managing family bereavement (p = .002). Accompanying a resident on death pronouncement in medical school was positively associated with self-assessed competency in the clinical examination for pronouncing death (p = .014) and in informing the family of death (p = .027), but frequency of the death pronouncement observations in medical school was not associated with variation in self-assessed competency ratings.

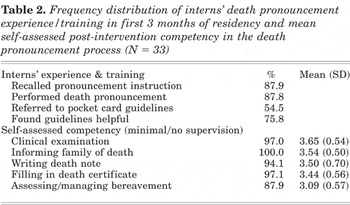

Survey 1 respondents that did not take Survey 2 (n = 15) were excluded from the post-intervention analysis (N = 33). Excluded subjects were not significantly different from the included subjects in any of the pre-intervention experience/training or self-assessment variables. The results of Survey 2 are summarized in Table 2.

Frequency distribution of interns' death pronouncement experience/training in first 3 months of residency and mean self-assessed post-intervention competency in the death pronouncement process (N = 33)

Nearly 90% of interns recalled having pronouncement instruction during pre-clinical orientation and pronouncing death at least once in the first 3 months of residency. 75% found the guidelines to be helpful. Over 50% recalled referring to guidelines in the pocket card. We found that the reported use of the death pronouncement pocket card was significantly related to perceptions of the usefulness of the guidelines (p = .003). Among those who used the guidelines, 81.1% perceived them as helpful/very helpful.

Percent of pocket card utilization was significantly higher among interns reporting multiple occasions of death pronouncement (p = .033). 83% of those who pronounced death 3 or more times during the first three months of residency reported utilizing the pocket card.

Post-intervention mean self-assessed competency ratings for the clinical examination for pronouncing death, informing family of death, writing the death note, and filling out the death certificate were not significantly different from one another. The mean competency rating for assessing/managing family bereavement was significantly lower than mean competency ratings for the clinical examination for pronouncing death (p = .005), informing the family of death (p = .005), writing the death note (p = .004), and filling in the death certificate (p = .005).

Perception of the helpfulness of the pocket card guidelines had a significant positive association with post-intervention competency in the clinical examination for pronouncing death (p = .038). 100% of those who found the card helpful reported needing minimal or no supervision in the clinical examination. Referring to the guidelines when pronouncing death was positively associated with post-intervention self-assessed competency in writing the note (p = .049). 100% of those who referred to the guidelines when pronouncing death reported needing minimal or no supervision with the death note (Table 2).

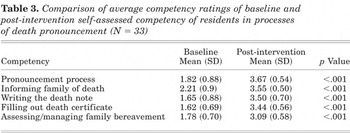

Significant pre-post increases were found in mean self-assessed rankings in each of the 5 competencies for the 33 subjects who took both the pre and post test (Table 3).

Comparison of average competency ratings of baseline and post-intervention self-assessed competency of residents in processes of death pronouncement (N = 33)

The process of death pronouncement can be a difficult, anxiety-provoking, and emotionally charged task for interns who typically receive little education or training in this process. At the outset of the study, over 80% of the interns indicated they needed further basic instruction or close supervision in 4 of the 5 death pronouncement competencies. Although 81.3% of participants reported medical school training in palliative care, less than 30% of the interns had formal instruction in the process of death pronouncement and less than 50% had accompanied a resident in a death pronouncement during medical school.

Before the intervention, interns assessed themselves as more competent in the interpersonal aspects of the death pronouncement process than in the procedural ones. These differences may be a function of medical school training in communication skills and perhaps palliative care instruction that did not incorporate formal instruction and training in death pronouncement.

Formal instruction and training in death pronouncement in medical school appears to make a difference in how interns assess their competency for this process. In our research, interns with previous education or training in death pronouncement rated their pre-intervention competency significantly higher than their peers in writing the death note, filling out the death certificate, and assessing/managing family bereavement. Those who had accompanied a resident to a death pronouncement during medical school assessed their pre-intervention competency in the clinical examination for pronouncing death significantly higher than their peers.

After the educational intervention, interns reported greater improvement in the procedural components of the death pronouncement competency than the interpersonal ones. While palliative care training has the potential to prepare medical students for the interpersonal component of the death pronouncement process, the educational intervention described here was useful for all interns since instruction in procedural aspects of the death pronouncement process is not currently a formal part of the medical education curriculum.

Use of the pocket card and perceiving the guidelines as helpful appear to make the most important contributions to post-intervention sense of competency in the death pronouncement process. Those who used the pocket card rated themselves significantly more competent than their counterparts in writing the death note; while those who found the card helpful, rated themselves significantly more competent than their peers in the clinical examination for pronouncing death. Percent of pocket card utilization was significantly higher among interns with multiple occasions of death pronouncement. Interns who pronounced death once or twice during the first 3 months of residency were less likely to report using the pocket card than those who pronounced death 3 or more times during the post-intervention period. This appears to be counterintuitive, because we tend to assume that those with less experience would rely more than the more experienced on the pocket card to guide them through the process. However, this research suggests that the pocket card remains useful in the face of increased experience in the death pronouncement.

Our findings are limited by several factors. During the 3 months of the survey, interns had numerous competency-enhancing medical experiences that could not be controlled for in this study, any of which could have affected their post-intervention survey responses. In addition, because we used a convenience sample composed of one class of interns in a single institution, we cannot generalize our findings to the entire intern population. However, the findings presented here have sensitized us to some of the important issues associated with interns' perception of competency in carrying out the death pronouncement process. By attending to the concerns identified in this study, we may be able to enhance competency and reduce the frequency of the emotional discomfort associated with the death pronouncement. Case control studies are planned to test these educational materials and analyze outcomes with other intern classes both at UAB at other institutions.

Survey 1: Baseline Self-Assessment of Clinical Competency and Concerns in End-of-Life Care: Resident Preparation for Death Pronouncement, Birmingham VA Medical Center, Birmingham, Alabama, June 2003 (Interns' Orientation Session).

Please rank your degree of competence with the following patient/family processes at the time of and after a death in the hospital, using the following scale:

Comments:

Survey 2: Post-Intervention Self-Assessment of Clinical Competency and Concerns in End-of-Life Care: Resident Preparation for Death Pronouncement, Birmingham VA Medical Center, Birmingham, Alabama, September 2003 (Interns Follow-up Session).

Please rank your degree of competence with the following patient/family processes at the time of and after a death in the hospital, using the following scale:

Comments:

Death often occurs at night when the primary team is unavailable and the intern on call is the only one available. You should expect that you will be called upon to perform this task at least once in the next few months. When called upon to pronounce death, some general knowledge of the patient's case will enhance your comfort level and sense of competency. Consult briefly with the nursing staff before entering the room to determine whether the attending physician has been notified. The nurses can fill you in on the patient's cause of death, recent history, family preferences concerning autopsy, organ donation (if appropriate), and pastoral care, as well as alert you to any long-term or emergent problems/concerns with patient care or family dynamics.

It is also important to know something about the immediate circumstances of the death. Was the death expected or sudden? Was the patient a DNR? Did death occur during a code? Was the patient comfortable or distressed? Were family members present at the time of death? If so, did they exhibit distress? If the family was not present at the time of death, determine if they have been informed. They may want to spend some private time with the patient before he/she is removed from the room.

If you have had no previous contact with the patient or family, ask the nurse to fill you in on the relationships of the family members present in the room. Request that the nurse accompany you into the room to facilitate your initial interaction with family members. When entering the patient's room, it is important to assume a calm and respectful demeanor. Introduce yourself by saying “I am Dr. … , the doctor on call.” Tell the family that you are there to perform the official death pronouncement and invite them to remain in the room.

The clinical examination for pronouncing a death serves not only to confirm that physiological death has occurred, but it provides the family with a sense of ritual closure with the medical care the patient has received. It should be carried out in a way that upholds the dignity of the patient and communicates the seriousness of the occasion. It is important that you do not allow any unease you may feel to detract from the solemnity of these final medical acts.

The following medical procedures should be carried out during the clinical examination for pronouncing death: (1) Check the ID bracelet to make sure the name on the bracelet corresponds with the name on the patient record. (2) Check the pulse for signs of life. (3)Check the pupils for position and response to light. (4) Check response to tactile stimuli—examine respectfully and refrain from sternal rubs or nipple pinches as they may upset the family. (5) Check for spontaneous respiration. (6) Check for heart sound and pulses. (7) Record the time of death.

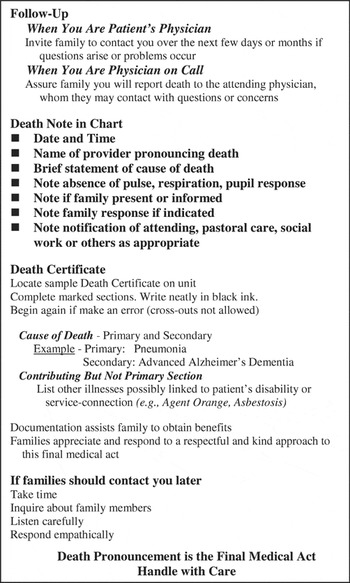

If you are the patient's physician, invite the family to contact you over the next few days or months if they have any questions or concerns that need addressing. If you are the physician on call, inform the family that you will report the death to the attending physician. Assure the family that they may contact the patient's physician with questions or concerns. If family members are present in the patient's room, you should be prepared to address any simple questions that they may have. Often, family members want a simple explanation of the cause of death. They may also ask if you think their loved suffered at the time of death or was aware of their presence in the room. Be honest, yet, reassuring in your responses. Before taking leave from the room, offer your condolences in a warm and dignified way such as “I am sorry for loss; this is a difficult time.” Finally, offer to address any concerns or questions they may have and/or to facilitate contact with others. Some families may ask you to contact pastoral care staff, social workers or other physicians on the treatment team.

After leaving the patient's room, it is your duty to document the death in the patient's chart and death certificate. Because the information contained in these documents carry legal import and have implications for family medical history, it should be entered accurately, completely and legibly.

The following items are part of the death note: (1) Date and time of death, (2) Name of provider pronouncing death, (3) Brief statement of cause of death, (4) Notation of the absence of a pulse, respiration, and pupil response, (5) Notation of family presence at the death and/or family notification the death, (6) Notation of family response if indicated, (7) Notation of notification of attending physician, pastoral care staff, social work staff or other staff as appropriate.

A sample death certificate can be found on the unit. It is important to complete all marked sections using black ink. When recording information on the death certificate, do not use abbreviations or cross out any entries. If you make an error, discard the certificate and begin again with a fresh copy.

When recording the cause of death on the death certificate, you will be asked to document both a primary (proximate) and secondary (ultimate) cause of death. Although many patients die following a terminal cardiopulmonary event, cardiopulmonary arrest is not the primary cause of death in all cases. In the case of a patient with Advanced Alzheimer's Dementia who develops pneumonia followed by cardiopulmonary arrest, the primary cause of death is Pneumonia while the secondary cause of death is Alzheimer's Dementia.

There are also contributing causes of death that, if known, should be recorded on the death certificate. These include other illnesses or disabilities. In a VA hospital, it is especially important to document any service-connected illnesses or disabilities that contributed to the patient's death. This will assist families in obtaining VA death benefits without undue delay.

Families are often too distressed or fatigued at the time of death to obtain all the information they may need. If a family member should contact you in the weeks and months following the death pronouncement, respond in a timely and empathetic manner. Bereavement is a difficult time for family members. They often appreciate it when the physician offers kind words about their loved one and inquires about their wellbeing. Listen carefully to their questions and assure them of your continuing availability to address their concerns.

Frequency distribution of interns' death pronouncement experience/training in medical school and mean self-assessed baseline competency in the death pronouncement process (N = 48)

Frequency distribution of interns' death pronouncement experience/training in first 3 months of residency and mean self-assessed post-intervention competency in the death pronouncement process (N = 33)

Comparison of average competency ratings of baseline and post-intervention self-assessed competency of residents in processes of death pronouncement (N = 33)