The zarzuela Chin-Chun-Chan: Conflicto chino en un acto y tres cuadras premiered at the venerable Teatro Principal in Mexico City on April 9, 1904.Footnote 1 The plot is generic enough: a Mexican man, on the run from his hectoring wife, disguises himself as a stereotypical “Chinaman” and checks into an upscale Mexico City hotel, where he's mistaken for a Chinese dignitary, Chin Chun Chan, whose imminent arrival has the hotel management in a tizzy. Predictable too is the chaos that ensues when the unsuspecting dignitary and the suspicious wife appear to expose the impostor. The plot device may have been nothing new, but the author added enough local spice to keep things interesting, with a picaresque Mexican protagonist whose verbal virtuosity challenges the limits of conventional syntax—a style later perfected by the inimitable Cantinflas—and a mostly good-humored take on the controversial presence of Chinese men in Mexico.

The combination of generic convention, nativist appeal, and topical resonance proved irresistible. By late June, Chin-Chun-Chan had been performed over 100 times (not always in reputable venues) and would go on to become the first Mexican theatrical work to surpass a thousand performances.Footnote 2 Within a month of the inaugural performance, aficionados could purchase paraphernalia that ranged from copies of the libretto with photographs of the cast in costume to a host of new lyrics for its most popular songs, produced by the indefatigable “people's publisher” Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, illustrated by master printmaker José Guadalupe Posada, and sold as colorful chapbooks and broadsides on the streets of downtown Mexico City (see Figures 1 and 2).Footnote 3

Figure 1 “La calavera del editor popular Antonio Vanegas Arroyo.” Mexico City: Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, [1917]. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division (https://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsc.03445/). Illustration signed by José Guadalupe Posada.

Figure 2 “Nuevas coplas del Chín-Chún-Chán: El charamusquero.” Mexico City: Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, [between 1904 and 1909]. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division (https://www.loc.gov/item/99615879/). Illustration unsigned, but probably José Guadalupe Posada.

That November, Vanegas Arroyo and Posada collaborated on a broadsheet, “La Gran Calavera del Chin Chun Chan,” for the annual Day of the Dead celebrations, a sign that the zarzuela and its memorable title had already made the transition from passing fad to cultural icon (see Figure 3).Footnote 4

Figure 3 “La Gran Calavera del ‘Chin Chun Chan.’” Mexico City: Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, 1904. Courtesy of the Jean Charlot Collection, University of Hawai'i at Ma¯noa Library (Inventory no. JCC.JGP:C43). The bottom cover image is signed by José Guadalupe Posada, who probably contributed most if not all the others.

An overnight sensation, Chin-Chun-Chan would soon become an everyday referent for Mexicans from all walks of life. Most Mexicans these days don't remember Chin-Chun-Chan and can no longer sing its once catchy tunes, but the phrase “Chin-Chun-Chan” has taken on a life of its own as—among many other seemingly unrelated things—the name of a famous Tacuba cantina, the title of a children's book, and the refrain for a popular technobanda song.Footnote 5

Theater historians have remarked on the zarzuela's iconic status in the popular culture of the period, but few have attempted to explain its enduring appeal.Footnote 6 In most accounts, Chin-Chun-Chan appears as an interlude of mildly racist, playfully misogynistic, risqué frivolity in soon-to-be troubled times—a nostalgic perspective captured perfectly in the 1940s feature film, Yo bailé con Don Porfirio (I Danced with Don Porfirio), which includes a vaudevillesque version of the “Cakewalk” finale with flirty chorus girls and a high-stepping blackface minstrel.Footnote 7 Musicologists have noted the skillful exploitation of zarzuela conventions by the librettists and composer—nativist themes, tongue-in-cheek humor, mistaken identities, accessible music, pretty dancers, stock characters (including a Polichinela from the commedia dell'arte)—expressed in a cosmopolitan but distinctly Mexican idiom with liberal doses of slapstick, sexual innuendo, language games, and albures (word play). The more thorough of these accounts have situated Chin-Chun-Chan in historical context, pointing out its playful references to symbols of Porfirian progress (railroads, streetcars, telephones, modern hotels, working girls, and others), international initiatives like the 1899 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation between Mexico and China, concern over the sudden influx of American-owned businesses all over Mexico, and the confusing hodgepodge of foreign languages, regional dialects, and alien customs that had suddenly appeared on the streets of what Mexico City elites liked to call “our cultured capital.”Footnote 8

These explanations are essential to understanding the Chin-Chun-Chan phenomenon. Taken together, they reveal the particular circumstances that were central to the zarzuela's astonishing success: a sizeable general public with the desire and leisure time to consume self-consciously modern entertainments, the artistic skills of in-house librettists and composers, the anxieties produced by Porfirian modernization efforts, and so on. What they don't adequately address, however, are the complex ways Chin-Chun-Chan played out in the period's popular culture or the reasons for the title's persistence as a catchphrase into the present era. That the zarzuela was popular in its day is no longer in doubt, but the specific contours of its enduring attraction have yet to attract sustained attention.

This essay, then, looks at popular responses to the zarzuela Chin-Chun-Chan and the issues that surfaced around its timely subject and catchy title in early twentieth-century Mexico City. The principal source for this study is the satiric penny press for workers, supplemented by the somewhat less political Vanegas Arroyo broadsides. Aimed for the most part at working-class Mexicans, these sources offer a glimpse at popular attitudes circulating in a public sphere otherwise dominated by the perspective of educated elites.Footnote 9 Seen through this unconventional lens, the zarzuela itself recedes into the background as Chin-Chun-Chan transitions seamlessly from theatrical sensation to semiotic sign.Footnote 10

For Mexico City workers—or more precisely for their self-appointed spokesmen from the penny press—the artistic work had only transient appeal. Its suggestive title, however, conjured up a host of concerns that showed (and still show) no signs of dissipating. If Chin-Chun-Chan was popular with the working classes, it wasn't just as musical theater but also as a touchstone for their growing discontent. In this first cultural iteration, the political resonance of both the zarzuela and the semiotic sign it generated was obvious—despite significant differences of interpretation and connotation with regard to their meaning. After the fall of Porfirio Díaz and the political upheaval that followed his departure, the catchphrase “Chin-Chun-Chan” would take on additional meanings, many of them seemingly unrelated to the tensions sparked by Chinese immigration to Mexico but still linked in subtle ways to the “Chinese problem,” however that might be understood.

The article has four sections. First, it briefly reviews social commentary—stimulated by Chin-Chun-Chan's popularity—on the democratization of musical theater, especially género chico (light musical theater), a phenomenon elite social commentators condemned as a prelude to social and cultural degeneration, but penny-press editors more often praised as harmless, even salutary, entertainment after a hard day at work. Second, the essay examines Chin-Chun-Chan—still loosely linked to the zarzuela—as a political symbol that crystalized around working-class complaints about the Porfirian regime, especially its alleged disregard for Mexican workers and Mexican national identity. Third, it analyzes the ways in which the phrase “Chin-Chun-Chan” entered into popular language as a racial signifier for a range of things, some of which bore little relation to its theatrical origins. Finally, it links popular Sinophobia in late Porfirian Mexico City to the virulent anti-Chinese campaigns in northern Mexico, which played a key role in defining national identity after the 1910 Revolution, and to the “hemispheric orientalism” that has characterized anti-Asian sentiments throughout the Americas.Footnote 11

Chin-Chun-Chan and the Democratization of Musical Theater

Popular entertainment in Mexico City underwent a radical change in the late fall of 1880 when impresarios at the major theaters, including the Teatro Principal (which would later premiere Chin-Chun-Chan), began to rent their venues on an hourly basis, by tandas or shows, to accommodate a broader range of productions and clientele.Footnote 12 The shift to a tanda system brought ticket prices within reach of working-class Mexicans, exposing them to the latest in imported and domestic musical theater, especially the popular one-act zarzuelas—often referred to as género chico that soon came to dominate Mexico City theaters.Footnote 13 As was the case in major metropolises elsewhere, Mexico City already had a vibrant if ephemeral working-class theater culture, much indebted to traditional entertainments like the circus and puppet shows but increasingly influenced by the cosmopolitan conventions of mainstream theater.Footnote 14 Before 1880, theatrical productions aimed at the working classes appeared most often in transient jacalones (literally “shacks,” figuratively “fleapits”) located for the most part in the city's seedier barrios. The switch to tandas made it possible for enterprising owners of respectable theaters to tap into this potential market without losing their middle- and upper-class clientele, who had the option of attending higher-priced shows.

The tanda system proved a financial success, but upset some influential patrons. In a newspaper column on “The Tandas of the Principal,” acclaimed poet Manuel Gutiérrez Nájera noted with his inimitable combination of snobbery and sarcasm that: “[The theater] reeks of tacky people [gente cursi]. The public wave their arms and stomp their feet just like the good old days of the jacalones [fleapits], and obscene jokes are received with crude guffaws … the obstreperous outbursts of men who only attend the theater when it costs one real.”Footnote 15 Unruly working-class men weren't the only problem. Efforts to reach a popular audience accustomed to raunchy jacalón shows further shredded the tattered remnants of bourgeois propriety that still clung to mainstream musical theater in Mexico City.Footnote 16 Less acerbic than Gutiérrez Nájera, fellow poet and social commentator Luis Urbina shared his distaste for the decline in artistic standards, especially at established theaters:

God spare me from sermonizing here against the género chico. In all parts of the civilized world there are places for insane gaiety. What I do say is that a theater of the first order, like the Principal, with its venerable artistic traditions, with its central and advantageous location, with the decided preference the public bestows upon it, should not be the home of nor the propagandist for pornography and poor taste.Footnote 17

Criticism aside, the tanda system opened up zarzuela production for Mexican writers and composers, whose ability to draw on current events, local themes, and colorful national stereotypes gave them a decided advantage over their Spanish counterparts. For critics like Gutiérrez Nájera and Urbina the drawbacks of commercial and aesthetic democratization outweighed any nativist benefit, but increased profits and tolerant government censors worked against a return to the status quo ante. Indeed, an article in Mexico City's major daily newspaper El Imparcial on the eve of Chin-Chun-Chan's premiere, alerted readers that the Teatro Principal had decided to restore its old (cheaper) ticket prices for the Easter season “taking into account that poor people are the ones who need easy access to the theater.”Footnote 18

Penny-press editors also fretted over the perceived decline in artistic standards. Four months after the Chin-Chun-Chan premiere, Fernando Torroella devoted most of an issue of El Papagayo to a critique of “El arte (?) moderno.” The front page leads with a satirical poem about a fictional zarzuela, Todo por el mono (All for the Monkey), illustrated by a Posada print of a soprano and baritone singing a love duet accompanied by a scruffy male chorus, big-legged dancing girls, a disheveled conductor, and a disgusted Apollo showering the company from backstage with roosters, frogs, and snakes (see Figure 4).Footnote 19

Figure 4 “El arte (?) moderno.” El Papagayo, July 17, 1904. Courtesy of the Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin. Cover image unsigned but probably José Guadalupe Posada.

A page-two editorial begins with a florid reaffirmation of the paper's commitment to working-class men—“our brothers, who like us, have had the disgrace to have been born without fortune”—followed by an equally overwrought denunciation of “criminals who wielding the dagger of little shame, take to the stage of the jacalones or theaters to murder with impunity, and the aggravating circumstances of premeditation, treachery, and advantage, the goddesses Thalia, Euterpe, and Terpsichore.”Footnote 20 The feature story provides mock reviews of the current musical offerings at the major theaters, including a passing reference to “Chin-Chun-Chan” (deliberately misidentified as a Japanese general) and a dig at the Moriones sisters, owners of the Teatro Principal (aka “Jacalón de los escándalos” or “Scandal Shack”), who had been forced by a judge to postpone the opening of the zarzuela Congreso Feminista over a dispute with the authors.Footnote 21 A month later, Torroella—now the editor of La Araña—followed up with a front page poem, “El Arte,” illustrated in this instance by a split-frame image with an elegantly dressed singer on the left side and a bare-legged dancing girl cheered on by a theater full of excited men on the right.Footnote 22 The caption below the image leaves no doubt as to the message:

Despite these concerns about the aesthetic shortcomings of what critics back in Spain had begun to refer to as género ínfimo (negligible genre), Torroella was an inveterate género chico aficionado. In a jokey list of fictional titles and authors, his successor at El Papagayo, Antonio Negrete, included “Chin-Chun-Chan Chintarará, poems to la Catarina by Fernando P. Torroella,” in recognition of his colleague's obsession.Footnote 23 Notably, Torroella shared none of Gutiérrez Nájera's disgust with the unrestrained behavior of working-class theatergoers. In a September 1, 1904, editorial on the “Prensa pequeña” (small press), he contrasted the experience of a hypothetical worker with the two genres. The first week, the worker takes in a serious theatrical work “overflowing with morality, sadness, and proper sentiments,” an experience that leaves him with “his mind depressed and his heart in pieces” and a lingering malaise that he unwittingly inflicts on his poor family.Footnote 24 The next week is a different story: “… he passes by a theater offering lighter fare [género chico], he goes in and watches Enseñanza Libre, S. Juan de Luz, or something in that style. Grotesque characters cross the stage, provoking laughter; they utter unseemly phrases and act in crude ways; the artisan laughs, enjoys himself, and forgets his troubles; he returns home and shares his happiness with his family.”Footnote 25

For Torroella, the contrast between the two theatrical genres mirrored the differences between the government-subsidized “big” press and the independent “small” penny press: “As with serious theater, it's the big press that instructs and reforms and the small press that distracts and diverts.”Footnote 26 In the eyes of penny-press editors such as Torroella, the aesthetic failings of the género chico were a small, if regrettable, price to pay for the opening up of the city's major theaters to all but the poorest workers and its welcome contributions to the psychological well-being of Mexico City's hard-working men (and sometimes women). For better or worse, working-class access to mainstream musical theater would make Chin-Chun-Chan's transition from theatrical sensation to semiotic sign an easy one.

A Sign for the Times

On the surface, popular concern over the Chinese presence in Mexico—one of the principal drivers of the Chin-Chun-Chan phenomenon—is somewhat puzzling. The overall number of Chinese immigrants in Porfirian Mexico wasn't especially high, around 1,000 in 1895, just under 3,000 in 1900, and slightly over 13,000 in 1910, and most settled in northern Mexico near the US border rather than in the capital.Footnote 27 Nonetheless, exponential increases in the number of Chinese migrant workers during these years and their alleged inability or unwillingness to fit into Mexican society gave the topic a salience it might otherwise have lacked. This was true even in the federal district, which had relatively few Chinese residents. The 1910 census reported just under 1,500 Chinese in a total population of over 720,000 people—and more than half of Mexico City's 471,000 people were migrants themselves, albeit mostly from other places in Mexico.Footnote 28

At its heart, popular concern about Chinese immigration had more to do with the politics of transnational labor recruitment and ongoing struggles to consolidate the nation-state than with the actual number of Chinese immigrants. Even government policy makers charged with developing economic ties to China and recruiting its workers expressed ambivalence about the project. An 1891 article in El Economista Mexicano noted:

Sly cunning, limitless perseverance, and a moral sense entirely foreign to our own shape the character of the sons of Confucius … they are a very close-knit people, which is what makes them so formidable and prejudicial to the public good [causa pública] of any society that unwittingly admits these strange elements into its bosom. If one adds in the disagreeable and repulsive qualities that characterize these Mongols, considered ethically and aesthetically in their physical appearance, their morals, their habits, their monstrous language, a veritable rattle of monosyllables, one understands … the general and instinctive antagonism against them.Footnote 29

Qualities like perseverance, endurance, and docility might make Chinese immigrants ideal workers for the henequen plantations of Yucatán or for building railroads in the country's tropical zones, but their perceived defects—described here in the hyperbolic racist language that would characterize later anti-Chinese propaganda—argued against any permanent settlement. A 1904 article in the Revista Positiva by José Covarrubias, member of a presidential commission to study Chinese immigration, supported this judgment: “Since we are unable to think about assimilating or dominating them [Chinese immigrants], we should treat them only as temporary associates, advising the government not to systematically exclude them as has been done in other countries … but rather to exercise a continual intervention that channels this immigration to the places it is needed, reduces it to appropriate levels, and conserves in government hands the direction of its movement.”Footnote 30

This was easier said than done. Circumstances north of the border—and out of the hands of the Mexican government—were playing a decisive role in shaping Chinese immigration into Mexico. By 1900, the US Chinese Exclusion Acts (1882, 1892, 1902) had pushed many Chinese immigrants from the western United States into northern Mexico and encouraged new arrivals to travel to the Mexican border states either as part of family migration networks or to facilitate their illegal entry into the United States.Footnote 31 Rumors that expelled Chinese workers were headed to Mexico fueled popular unrest in the northern borderlands. As early as 1886, Mazatlán police were forced to confiscate dozens of Chinese Judas effigies destined to be exploded during Holy Week, because they feared that the public celebration might incite a race riot.Footnote 32

Despite recurring signs of popular discontent, the Porfirian regime and the Chinese government negotiated and signed the Treaty of Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation (1900), which committed the two countries to “perpetual, firm, and sincere friendship … between their respective citizens and subjects” and signaled continued Mexican government support for Chinese immigration.Footnote 33 The treaty was consistent with Mexico's liberal immigration laws, which extended to all foreigners the basic rights and protections accorded Mexican citizens.Footnote 34 Although intended primarily to attract white European immigrants, especially from Catholic “Latin” countries, immigration policies were more often blamed for the intrusion of undesirable foreign workers from other places, who allegedly took jobs from Mexican nationals and disrupted the social order in any number of ways. Whatever the truth of the allegations, the government's presumed refusal to support Mexican workers against their foreign rivals added to a growing list of working-class (and other) grievances.

During the prosperous early decades of the Porfiriato, increased employment opportunities, rising wages, and effective government labor policies had damped long-standing working-class complaints, especially in urban areas such as Mexico City. By 1890, however, wages had peaked and the cost of living had begun to rise, sometimes precipitously. In response, even regime-friendly labor organizations began to express tentative opposition to Porfirian labor policies, especially with regard to foreign workers.Footnote 35

Penny-press editors were less reticent. Although they avoided overt revolutionary sentiments and seldom attacked Porfirio Díaz himself, these self-appointed spokesmen for the clase obrera (working class) had no trouble reviling the hated bourgeoisie, the exploitative gringos, and the president's select cadre of científicos (technocratic advisers) on a regular basis.Footnote 36 Prominent on this blacklist of working-class enemies were racialized foreign workers, especially white North American men (who were generally paid more than their mostly mestizo Mexican counterparts) and Chinese men (who were generally paid less).Footnote 37 Although labor and immigration politics played no obvious role in the zarzuela—the only “Chinaman” is a visiting dignitary—Chin-Chun-Chan's remarkable popularity proved an irresistible excuse to voice working-class discontent with the Porfirian regime.

The opportunity was obvious early on. Just five months after the zarzuela's mid-April premiere, La Guacamaya led off with a satirical poem about a “spontaneous protest against a son of the Celestial Kingdom” entitled: “Chin-Chun-Chan in the City of Martyrs” (see Figure 5).Footnote 38

Figure 5 “Chin-Chun-Chan en la Ciudad de los Mártires.” La Guacamaya, August 18, 1904. Courtesy of the Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin. Cover image signed by José Guadalupe Posada.

The center-page Posada illustration foregrounds four Mexican men harassing a Chinese man as a policeman approaches from behind with a raised truncheon. The Mexican men wear clothing and hats associated with different working-class occupations; the Chinese man wears the loose cotton jacket and trousers typical of a culi (coolie) laborer.Footnote 39 Two assailants tug at their victim's pigtail while a third, a hatless paper boy, dances in front of him making obscene gestures. Although the image shows the persecuted man's fearful attempt to escape his tormentors and the poem includes his plaintive query—“What I do to you?”—there is no hint of sympathy for his plight. Instead, the poem ends with the assailants hauled off to the police station where they are “deceived” by the authorities. To emphasize the point, the Spanish idiom “meter la mula”—which derives from the deceptive practice of adding the weight of the mule to the weight of the freight—is interrupted by ellipses, hinting at a much cruder idiom, “meter la verga,” which translates literally as “to stick the dick (into someone or something)” or “to screw someone over.” That someone was a Mexican worker. And the person ultimately responsible for his plight was not the policeman—the quotidian face of state policy—but the unfortunate “hijo de la … china,” a euphemism for “hijo de la chingada,” which translates literally as “son of the fucked one” or colloquially in English as “motherfucker.”Footnote 40

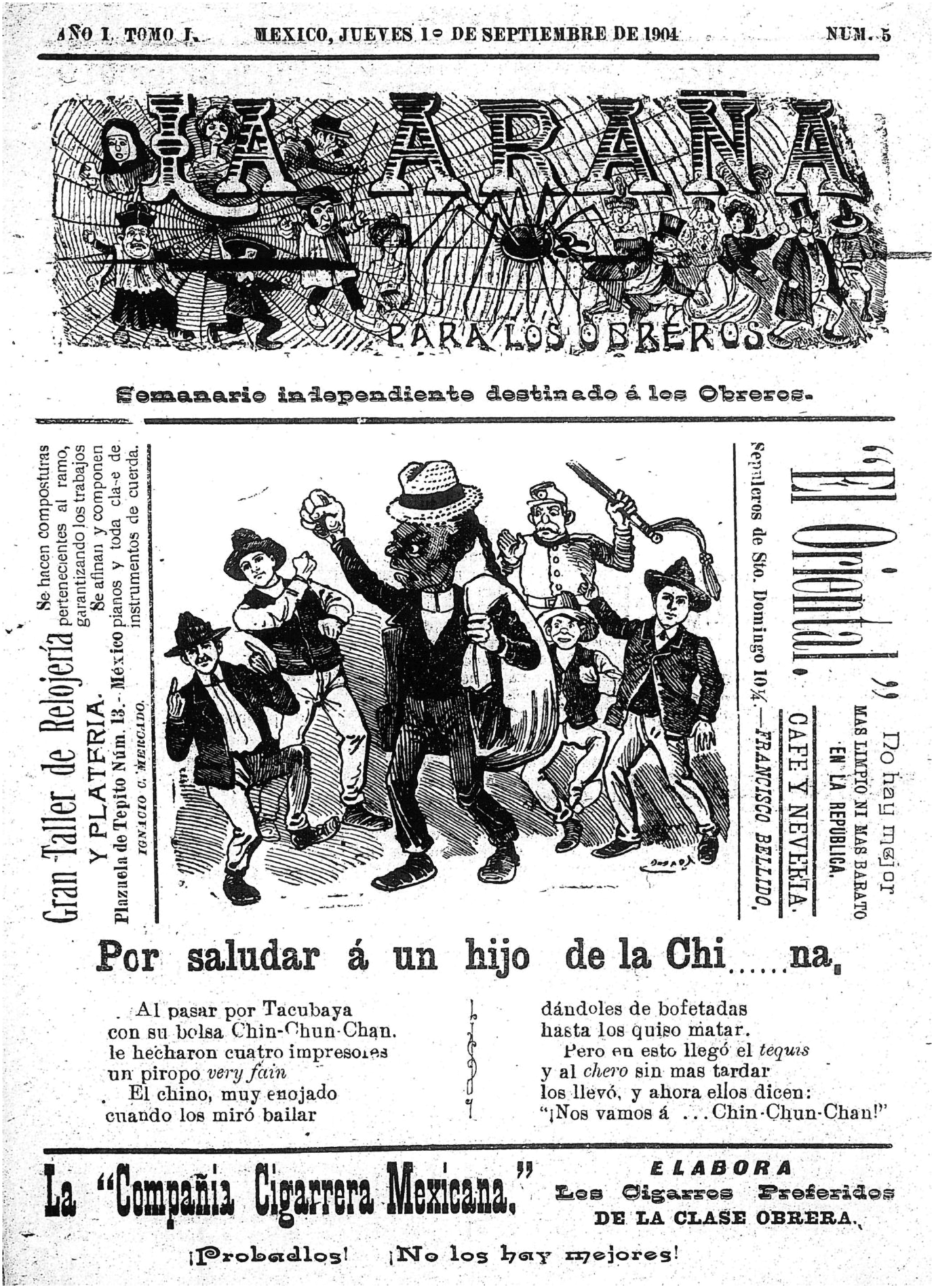

Two weeks later, La Araña followed suit with a cover illustration and poem on an identical theme, “Por saludar á un hijo de la Chi … na” (Greeting a son of Chi … na), shown in Figure 6.Footnote 41

Figure 6 “Por saludar á un hijo de la Chi … na.” La Araña, September 1, 1904. Courtesy of the Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin. Cover image signed by José Guadalupe Posada.

The cover image, also by Posada, features the same protagonists and basic plot as the earlier version: four working-class Mexican men threaten a Chinese man as a policeman runs up with raised truncheon to stop the altercation. In this instance, however, the persecuted Chinese man is dressed in more conventional clothing, including a hat, and glares at his harassers with a raised fist. The poem advises the reader:

Although the Chinese man in this instance is angry rather than fearful, the result is the same: a policeman hauls the Mexican harassers off to jail. Here too, ellipses in the text gesture to a common obscene phrase, “vámonos a la chingada” or “let's get the fuck out of here.” And the mock English “very fain” suggests a not so subtle link between North American and Chinese penetration of Mexican geographic and cultural spaces.

Penny-press editorials made the link between Porfirian labor policies, Chinese immigration, and Chin Chun Chan even more explicit. A subsequent commentary in El Pinche protested the replacement of older women workers and the lowering of wages in a Mexico City workshop with the comment: “They assume [the women] are slaves, and those of us born under the tricolor flag have never been that. Slaves? Let them bring in the sons of Chin-Chun-Chan to see if they're willing [to be slaves].”Footnote 42 A 1907 editorial in El Diablito Bromista tied the problem unequivocally to official policies designed to encourage the Chinese migration.Footnote 43 The author begins with a complaint: “You can't take a step with tripping over a monkey face, in other words a Chinaman. Turn the corner, there's the inevitable Chinaman. Enter a restaurant, the inevitable Chinaman. Your wife goes out to spend time in the plaza, she encounters a filthy Chinese pig.”

This generalized racist screed is followed by a more pointed comment from his neighbor, a widowed washerwoman “with not a bad moustache”: “Ay, Little Devil, I just don't know how the Government can allow so many of these people to enter [the country]; seeing as they're letting them in, they should send them to the agricultural colonies, they would be better off there and not here where it runs the risk of race mixture and [threatens] the work of those like me who live from taking in laundry.” To which the author responds: “That's washing with brush and soap [telling it like it is]. I agree with the widow woman.”Footnote 44

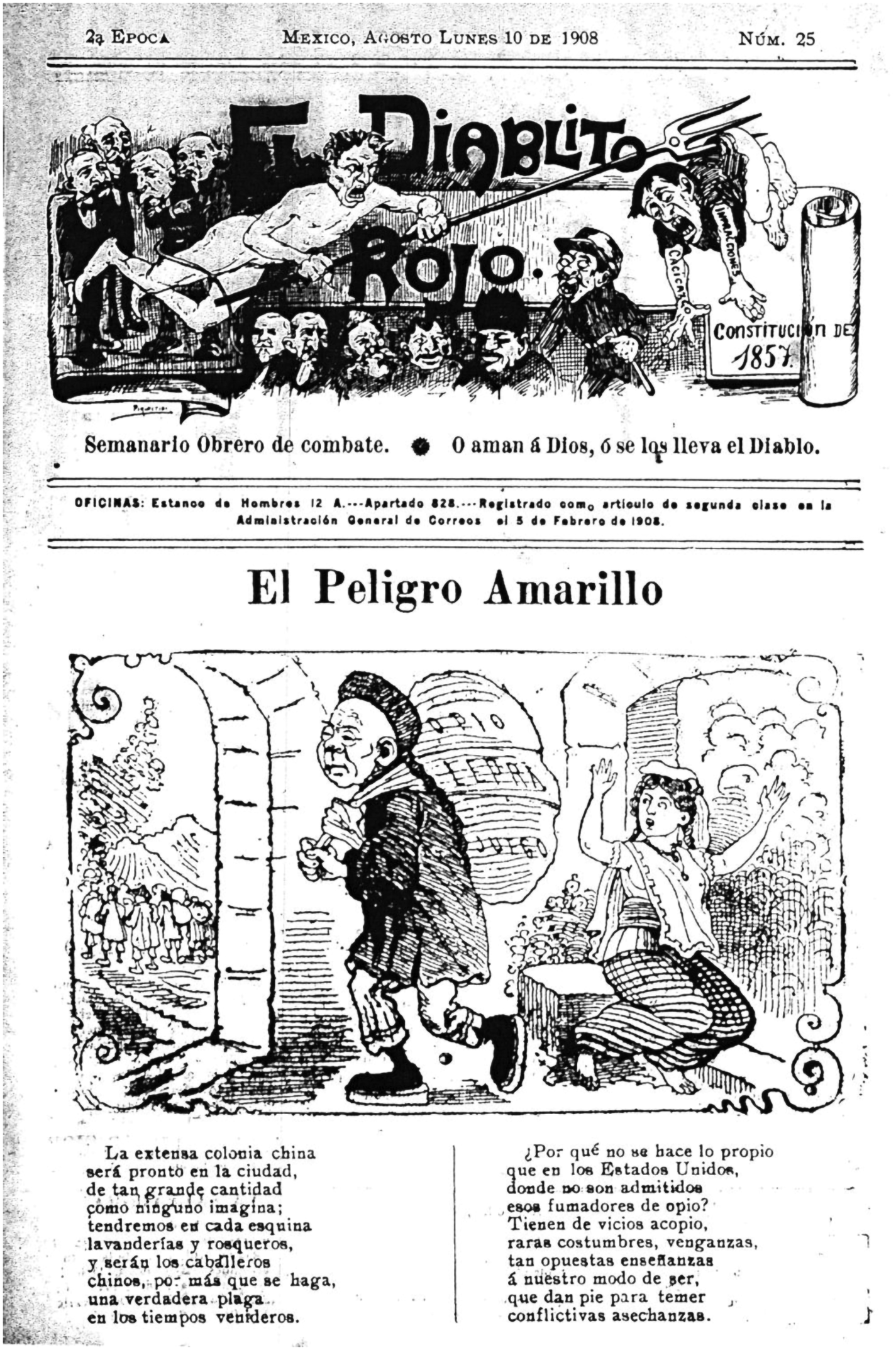

By 1908 complaints about Chinese immigrants had expanded beyond their role in lowering wages and replacing Mexican workers to include a range of alleged vices—typically cast as epidemic diseases—that threatened the nation as a whole. A 1908 El Diablito Rojo cover titled “The Yellow Peril” features yet another image by the ubiquitous Posada: a stereotypical Chinese man toting a large sack labeled opium, leprosy, and gambling (see Figure 7).Footnote 45

Figure 7 “El Peligro Amarillo.” El Diablito Rojo, August 10, 1908. Courtesy of the Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin. Cover image unsigned by probably by José Guadalupe Posada.

The Chinese man has just passed through a portal despite the protestations of a female personification of Mexico—dressed as a stereotypical china poblana—who sits helplessly on a bench, waving her arms and looking distressed. He is about to pass through a second portal into a stream of people, many of them also carrying sacks, an obvious representation of Chinese immigration—and the “perils” it was bringing in its wake.Footnote 46 The poem beneath the image warns:

In this image, Chinese immigrants not only replace Mexican businesses (laundries and pastry shops) and take Mexican jobs (from women and men), but they also disrupt Mexican culture with “vices aplenty, strange customs, vendettas, [and] teachings so opposed to our way of being.” A short poem on the next page, “El amor amarillo” (Yellow Love), adds yet another charge to the list, one of special concern to Mexican working-class men:

In this instance, the gendered nature of the “yellow peril” comes to the fore as Chinese men seduce Mexican women, including with sweet pastries, into unwholesome relationships that age and disfigure them—presumably rendering them unfit for reproduction and motherhood. Present too is the specter of race mixture, mentioned explicitly in the previous anecdote of the widowed washerwoman, a somewhat surprising concern in a society that even Mexican elites had begun to characterize as “mestizo.” However, for this author, as for most of his compatriots, Mexican mestizaje (race mixture) did not and should not include “foreign” races like the Asian Chinese, despite the country's long history of miscegenation and transpacific connections to the Philippines and China. The apparent irony of mestizo working-class subjects deploying racist language to speak truth to Porfirian power went unremarked, and likely unnoticed.Footnote 48

As evident from the foregoing examples, working-class Sinophobia was more than a simple matter of lost jobs, eroding wages, and declining living standards. Indeed, the images, language, and arguments deployed here are deliberately offensive, and penny-press editors made no attempt to engage readers in a straightforward debate over the detrimental consequences of official labor and immigration policies. Instead, they played to deep-seated and often unconscious cultural fears of filth and disease, vice and corruption, foreigners and miscegenation, loss of manhood and female betrayal, and so on.

Disgusting Objects, Disgusted Subjects

This preference for the loaded language of moral panic over reasoned political critique requires some explanation. In The Cultural Politics of Emotion, social theorist Sara Ahmed notes how certain attributes come to “stick” to objects, including foreign bodies. Stickiness, she argues, is not a property of the object itself but rather “an effect of the histories of contact between bodies, objects, and signs.” “What sticks,” she adds, “shows us where the object has travelled through what it has gathered onto its surface.”Footnote 49 By the early twentieth century, Mexico City penny-press editors could draw on a deep reservoir of stereotypes that dated back to the late medieval accounts of European travelers like Marco Polo and the sixteenth-century beginnings of Spanish imperial trade with China—a trade fueled by Mexican silver that ran from China to the Philippines to Spain via Acapulco. Tracing this convoluted history across the longue durée is far beyond the scope of this essay. But it is worth noting that the stickiness of Chinese bodies was well-established by the period in question. So too were most of the traits that stuck to those bodies.

In Ahmed's account, the emotion of disgust is essential to the historical process through which objects—Chinese male bodies in this instance—become sticky. The disgust evoked by the “sticky” bodies of Chinese migrant workers is represented in a number of time-tested ways in Mexican working-class Sinophobia (and in its bourgeois counterpart, as seen earlier). The most obvious is the near constant recourse to disease metaphors “as if their presence makes ‘us sick.’”Footnote 50 “The Yellow Peril” cover, for example, labels the influx of Chinese a “veritable plague,” a term that encompasses not only epidemic disease but also contagious vices—opium smoking, vendettas, gambling—and the distressing but not particularly contagious disease, leprosy. The “Yellow Love” poem goes a step further, linking disease to adulterated Chinese pastries that sicken the women foolish enough to be seduced by them (and by Chinese men). Earlier examples exploit the connections between disease, food, and “filthy” animals such as mice and pigs. The poem-caption for “Chin Chun Chan in the City of Martyrs,” for instance, identifies its Chinese protagonist simply as someone “who eats a lot of mice.” And the rhyming metonymic slide from chino (Chinese man) to cochino (pig) proves irresistible to more than one author.Footnote 51

All of these metaphors—epidemic disease, sexual relations, food, filthy animals (as food and conveyors of disease)—derive much of their power from fears of bodily penetration.Footnote 52 Ahmed points out: “Food is significant not only because disgust is a matter of taste as well as touch … but also because food is ‘taken into’ the body.”Footnote 53 The same sensory qualities (including smell) apply to the other sources of bodily penetration as well. And it is these tactile (and olfactory) sensations, which enter the body of the “host,” rather than visual cues, which rely on physical separation from the viewer, that provoke the visceral nausea characteristic of disgust.

More so than other emotions, Ahmed argues: “Disgust is clearly dependent upon contact … . while disgust over takes the body, it also takes over the object that apparently gives rise to it.”Footnote 54 The El Diablito Bromista editorial quoted earlier, for example, revolves precisely around the threat of physical contact and the disgust “you” experience in the encounter with disgusting Chinese bodies —and the possibility that “your wife” might come into contact with “a filthy Chinese pig.” Moreover, this unwanted contact occurs in everyday public spaces—street, plaza, restaurant, laundry, pastry shop—and the disgust it provokes is an instinctive rather than reflexive response, one that “over takes” the Mexican body and “takes over” the Chinese body, as happens in the two Posada images, where working-class Mexican men spontaneously harass a passing Chinese man. Disgust thus marks the moment when instinctual response shifts into political action in an act of expulsion that the subject justifies as righteous self-defense.

As Ahmed makes clear, even though the subject most often experiences disgust as an instinctual rather than reasoned response, labelling an object “disgusting” is fundamentally a speech act that generates both the subject and its object.Footnote 55 Moreover, “the speech act is never simply an address the subject makes to itself … [it] is always spoken to others, whose shared witnessing of the disgusting thing is required for the affect to have an effect.”Footnote 56 This shared witnessing, then “generates a community of those who are bound together through the shared condemnation of a disgusting object or event.”Footnote 57 In the first two Posada images, that community is visually represented as working-class Mexican men; in the other examples, a similar community (which may have included women) is interpolated as “dear reader” and constituted by members of a working-class identified “public” (that wasn't limited to working classes)—a public produced in this instance through shared disgust and the collective expulsion of disgusting foreign bodies.Footnote 58

The Everyday Language of Racism

Popular Sinophobia in early twentieth-century Mexico City drew readily and easily on “the histories of contact between bodies, objects, and signs” that marked Chinese bodies as disgusting and deserving of expulsion.Footnote 59 But if penny-press editors and collaborators had little to add to the hoary repertoire of Chinese stereotypes, their contributions to the everyday language of racism in Mexican culture were significant, enduring, and closely tied to the ephemeral success of the zarzuela Chin-Chun-Chan. In her work on The Everyday Language of White Racism, linguistic anthropologist Jane H. Hill notes: “Stereotypes and slurs are visible as ‘racist’ to most people … But other kinds of talk and text that are not visible, so called covert racist discourse, may be just as important to reproducing the culturally shared ideas that underpin racism. Indeed, they may be even more important, because they do their work while passing unnoticed.”Footnote 60

She argues further that the seemingly innocent incorporation of Spanish words like cerveza or mangled phrases like “no problemo” or “mucho grassy-ass” into everyday English produces “a particular kind of [White] American identity, a desirable colloquial persona that is informal and easygoing, with an all-important sense of humor and a hint … of cosmopolitanism.”Footnote 61 The very fain reference noted earlier suggests that penny-press authors used mock English in much the same way. In this instance, however mangled, English words and phrases also function to lampoon pretentious Mexicans who sought to link themselves linguistically to Anglophone interlopers. This twist adds a layer of ironic self-mockery that is less evident, but perhaps not altogether absent, in contemporary American usage.Footnote 62

While speakers may deploy mock Spanish primarily to construct individual personas, Hill alerts us that “such utterances are [also] part of a collective project, in which negative stereotypes are constantly naturalized and made normal, circulating without drawing attention to themselves … living in interactional space created in mutual engagement, as people get jokes, apprehend stances, and orient towards identities.”Footnote 63 The role of mock English in Mexican social satire, grounded in social anxieties around cultural imperialism, served a similar collective purpose, although penny-press authors differentiated their “interactional space of mutual engagement” from its bourgeois counterpart through a range of class markers, including colloquial language, in-jokes, countercultural attitudes, and repeated invocations of working-class identities.Footnote 64

Mock Chinese was yet more complicated. At one level, its recurring use in the wake of the Chin-Chun-Chan phenomenon contributed to penny-press efforts to conjure up a modern mestizo working-class identity. Racial hierarchies in Mexico had never been as stable as elites might have liked, especially after independence from Spain in 1821.Footnote 65 By the early twentieth century, the need for an inclusive postcolonial national identity, coupled with the prestige of indigenous and mixed-race liberal heroes such as José María Morelos, Benito Juárez, and Porfirio Díaz, had encouraged an officially sanctioned discourse of mestizaje that openly acknowledged (and sometimes celebrated) the nation's mixed indigenous and white European heritage, reluctantly accepted African influences, but emphatically rejected any Asian role in the forging of the Mexican race.Footnote 66 In this context, penny-press efforts to construct a coherent working-class identity stood to benefit from shifting the focus of racial anxieties from the internal contradictions of mestizaje to the clear and present danger of “Asian microbes.”Footnote 67 So, while the satiric use of mock English reflected anxieties around Anglophone linguistic imperialism, mock Chinese conjured up an incomprehensible linguistic Other that worked to reinforce penny-press (and other) attempts to lay claim to lo mexicano through language.

Mock Chinese differed from mock English at other levels as well. The humor behind mock English relied on misspellings and fractured syntax that reproduced the Spanish-inflected pronunciation of the speaker, thereby exposing the inadequacy of their clumsy attempts at mimicry. This strategy required that the English words and phrases be comprehensible to non-Anglophone readers; otherwise, they might not get the joke. In contrast, mock Chinese stressed the fundamental incomprehensibility of the spoken language, which was typically rendered as a string of nonsensical monosyllables.Footnote 68

The case of mistaken identity at the heart of Chin-Chun-Chan depends on this rhetorical device. When Columbo, a Mexican man on the run from his hectoring wife, enters an elegant Mexico City hotel disguised as a stereotypical “Chinaman,” he soon realizes that the hotel manager has mistaken him for a visiting Chinese dignitary named Chin-Chun-Chan. He responds to the manager's effusive greeting with mock Chinese, “Tzanchin-lai-chú … la … la … ran,” then switches to fractured, Chinese-inflected Spanish: “Quiele sopa come, cualto descansa, cama” (I want soup eat, room rest, bed).Footnote 69 An interpreter who appears later in the zarzuela reads a Chinese message from the dignitary's entourage as “Chin-Chan-La-Fi-Yo-Fo.” And when the real Chin-Chun-Chan finally appears, he addresses the hotel staff with “Yut-mot-fu-tzu-ya,” then turns to the disguised Columbo, who he presumes is a fellow countryman, and asks: “¿Y ta-mu-fu-tzu-jim … Tzau-li-fo-fo?” Columbo responds “¡Ah! ¿Fo-fo? Sí, fo-fo.”Footnote 70 The underlying message behind these nonsensical syllabic chains—as a provincial hotel guest explains to his new bride—is that “the Chinese aren't people like us: they don't hear or see or understand.”Footnote 71

Penny-press authors happily borrowed the monosyllabic chain from Chin-Chun-Chan as a rhetorical device for mock Chinese, along with its repeated references to the language's fundamental incomprehensibility. A list of silly book titles in La Araña, for example, includes “Chin-La-Su-Ja-Li-Fo-Fó: Reminiscencias sobre la guerra” (Chin-La-Su-Ja-Li-Fo-Fó: Memories of War).Footnote 72 A flirty “street talk” dialogue between a working-class man and woman in the same paper includes this passing reference to the syllabic sameness of spoken Chinese:

Mujer: Pos vamos al Bombardeo y aluego nos piramos al Chin-Chun-Chia.

Hombre: Chan, muger, no seas bagre.

Mujer: Te adigo ansina por que lo mesmo da atrás que anancas.Footnote 73

Woman: Let's go to the Bombardeo and then check out Chin-Chun-Chia.

Man: Chan, woman, don't be cute (lit: a catfish).

Woman: I say it that way because it's the same backwards as forwards.

Mock Chinese veers into comprehensibility only is when it functions as a euphemism for a Spanish obscenity, most often some variant of the verb chingar, a strategy noted earlier in the poems that accompanied the first two Posada images. Another pair of “street talk” dialogues provides additional examples. A column from La Guacamaya includes the following exchange between two working-class friends:

In this example, the first speaker confuses “Chin-Chun-Chan” with the popular obscenity “chinsumá” (a truncated version of “chinga su madre” or “fuck your mother”), because, as he tells his friend, since he's not a poet he can't distinguish one rhyming syllable from another. Another dialogue from El Papagayo uses the same play on words but the speaker goes on to explain his deliberate replacement of the zarzuela title with the popular obscenity, which suggests that the substitution was commonplace among working-class theater goers:

In other cases, the metonymic slide into obscenity was common enough that a clever author could skip straight to the euphemism, as happens in this opening to a La Guacamaya dialogue: “¡Que viva la penca, Chin-Chun-Chan, rotos piojosos! (“Long live the maguey, Chin-Chun-Chan, lousy dandies!”)Footnote 76 Here, Chin-Chun-Chan transforms the popular toast “chin” into a curse, “chinsumá” (colloquially: “up yours”), directed by a working-class man drinking pulque—a traditional working-class drink made from fermented cactus juice—at the much despised “rotos piojosos,” working-class dandies with middle-class pretensions who turn their backs on their own kind.

Chin-Chun-Chan's versatility as a semiotic sign was apparent early on, as was its connection to abject bodies. The following La Guacamaya dialogue between a working-class woman, doña Gertrudes, and a male acquaintance, don Pitacio, provides an illustrative example.

DP: ¿Pos qué no le gusta el Triato? [El Teatro Popular]

DG: Pero no en ese.

DP: ¿Por qué chula?

DG: Pos, por que anuncia una cosa y aluego dan otra.

DP: ¡Ah! Güeno, pos ya esa ya es otra vicoca; ansina es ora el modelo.

DG: Pos si Don Pitacio, el otro día que fui con mi viejo decía en los prospeito que iban á dar El Rosquete de San Antonio y aluego que sale un jaño y dice: respeitable público, por incontrarse muy malo de catarra inglés el Minino, se cambia la función por la que saque la cuchara.

DP: Güeno y ¿qué hasta los gatos trabajan allí?

DG: ¿Por qué me lo apreguntaste?

DP: Pos como ¿por qué? pos por eso del Minino.

DG: Pos a que usté tan piedra pos el Minino no es un gato ni mucho menos, es un jaño que le hace de cuarenta y uno en la Compañía.

DP: ¡Ah, ora si ya entendí pero no le hace, vámonos a pirando pallantos.

DG: No: más mejor vámonos al Triato de los Diarrea.

DP: ¿Diraste, Lelo de Larrea?

DG: Pos eso, que alcabucil, es lo mesmo, pos hora dan Chintarará.

DP: ¿Diraste, Chin-Chun-Chan?

DG: Pos eso es lo que quero dicer, sino que como soy cialtiro majada, no sé como se dice.Footnote 77

DP: So you don't like the [Teatro Popular]?

DG: It's not that.

DP: Then why [are you upset], sweet thing?

DG: Well, they advertise one thing and then do another.

DP: Ah! I see, well that's another deal, that's the way they do things these days.

DG: Well, yes, don Pitacio, the other day, when I went with my old man, the program said that they were going to present The Sweetcakes of San Antonio and then out comes a guy who says: honorable public, because el Minino finds himself very sick from an English cold, we're changing the show you came for [literally: took your spoon out for].

DP: Fine, but since when did cats start working there?

DG: Why did you ask me that?

DP: What do you mean why? Well because of the el Minino thing.

DG: Then you're just being dense [lit: you're a rock], since el Minino isn't a cat, far from it; he's a guy who plays the forty-one [character] in the Company.

DP: Ah, now I understand! But never mind, let's go complain about it.

DG: No: let's go to the Theater of the Diarrhea instead.

DP: You mean [Teatro] Lelo de Larrea?

DG: That's what I'm trying to say, since now they're showing Chintarará.

DP: You mean, Chin-Chun-Chan?

DG: Well that's what I mean to say, but since my mind is so full of nonsense, I don't know how to say it.

The humorous thrust of the dialogue revolves around don Pitacio's persistent attempts to convince a coy doña Gertrudes to go to the theater with him, even though both have other partners. And indeed, the possibly adulterous flirtation culminates in the two heading off together to see Chin-Chun-Chan at the well-known Teatro Lelo de Larrea, phonetically linked by a possibly illiterate patron to slimy excrement—a classic sign of abjection.

In this exchange, simple word substitution blossoms into full-blown parapraxes, inadvertent slips of the tongue that reveal repressed meanings. At the beginning of the excerpt, the principal object of derision is not a Chinaman but the abject figure of a queer male body—a move that deflects attention from the transgressive sexual behavior of the two heterosexual protagonists to the “unnatural” desires of homosexual men. The queer coding is subtle but unmistakable. At the same time that doña Gertrudis vents her annoyance with the Teatro Popular to don Pitacio because “they advertise one thing and then do another,” she also reveals that she went to see El Rosquete de San Antonio with her “old man,” but the lead actor, El Minino, had caught an “English” cold, and so the theater had to replace it with another show. At first glance, the author seems to be alerting the reader that doña Gertrudes is carrying on a flirtation with don Pitacio behind her old man's back. However, the reader's attention is simultaneously displaced by a series of queer referents: rosquete which translates as “sweetcakes” but is also slang for an effeminate man, an actor named El Minino whose name is a common stand-in for “pussycat” (hence don Pitacio's confusion), an “English cold,” which hints at both foreignness and male sexual deviance in the wake of the 1895 international scandal around playwright Oscar Wilde (whose work was performed regularly in Mexico City), and false advertising associated with male effeminacy (men not acting like men).

Doña Gertrudes clarifies these not-so-subtle innuendos for the clueless don Pitacio—he thinks Minino is a real cat—by explaining that the actor plays the “forty-one” character in the theater troupe, a reference to the notorious “Famous 41” scandal which followed a 1901 Mexico City police raid on an all-male private party where half of the attendees were dressed as women.Footnote 78 When don Pitacio suggests that they go back to the Teatro Popular to lodge a complaint, she counters with “let's go to the Theater of the Diarrhea instead,” a classic Freudian slip that substitutes the names of an abject bodily response to tainted food for the otherwise respectable Teatro Lelo de Larrea, which happens to be showing “Chintarará.” Don Pitacio responds: “You mean Chin-Chun-Chan?”Footnote 79 The accumulation of semiotic signs of disgust around abject male bodies here is hardly a coincidence, with Famous 41 references working to queer the Chinaman, whose sudden appearance at the end of the dialogue (as Chin-Chun-Chan) coincides with the hesitant doña Gertrudes's decision to go off with don Pitacio. In this story, then, the fatuous woman is seduced not by adulterated Chinese pastries or queer Chinese men with steady jobs but through the wiles of a persistent working-class Mexican man.

Conclusion

On the surface, the penny-press response to Chin-Chun-Chan seems little more than a curious, if disturbing, episode in the cultural history of late Porfirian Mexico City. Put in broader historical context, however, it helps explain the popular appeal and paradoxical centrality of Sinophobia to racial politics and nationalist discourses in postrevolutionary Mexico and throughout much of Latin America, even in places like central Mexico (and Brazil) with relatively little Chinese immigration.

With regard to Mexico, the presence of a deeply ingrained working-class Sinophobia in Mexico City in the decade before the outbreak of revolution provides useful background for understanding postrevolutionary racial politics and their role in national consolidation. Gerardo Rénique has argued convincingly that an especially virulent and often violent strain of Sinophobia, forged in the northern borderlands during and after the Mexican Revolution, rose to national prominence in the postrevolutionary period, “galvanized by the cultural and intellectual debates of the 1920s and 1930s, which redefined Mexican national identity.”Footnote 80 For Rénique, the 1924 election of former Sonoran governor Plutarco Elías Calles as president, in particular, signaled the emergence of “anti-Chinese racism … as a nationally organized political movement with broad political appeal among the popular classes and middle sectors of Mexican society … [which] became a catalyst for the consolidation of Mexico's postrevolutionary racial formation.”Footnote 81 This periphery-to-center, top-down trajectory might suggest a certain innocence on the part of the urban popular classes in central Mexico. To the contrary, the enthusiastically racist response of penny-press editors to the Chin-Chun-Chan phenomenon reveals that postrevolutionary norteño Sinophobia fell on willing and well-tuned ears.

One instance of this advance preparation stands out: widespread concern about race mixing between willing Mexican women and predatory Chinese men. Rénique notes that “national/racial anxiety found forceful expression in the gendered, sexist, and class-biased understandings of anti-Chinese discourse and popular common sense, depicting working-class Mexican women as the vehicle for the penetration and contamination of the national organism.”Footnote 82 These anxieties around racial miscegenation would find regular expression in Mexican popular culture during and after the Revolution, as Robert Chao Romero explains:

Even though popular Mexican culture sometimes found humor in the courtship antics of Chinese male immigrants, Mexican women who married Chinese suitors were shunned and scolded as “dirty,” “lazy,” “unpatriotic,” and “shameless.” Chinese-Mexican marital unions were condemned as marriages of convenience in which lazy Mexican women avoided work thanks to financial support from their Chinese husbands. Such cross-cultural relationships, moreover, were said to threaten the ruin of Mexican womanhood and to defile the Mexican nation.Footnote 83

These visceral fears of societal pollution and masculine inadequacy would have come as no surprise to readers of the prerevolutionary Mexico City penny press. What distinguishes late Porfirian popular Sinophobia from its influential norteño counterpart, then, was the endorsement of powerful political figures like President Calles and the postrevolutionary ideological imperative to consolidate a national mestizo identity, against which “the Chinese served as a convenient scapegoat and ethnic “other” that the larger mestizo population could rally around and against.”Footnote 84 Under the circumstances, the apparent anomaly of racialized working-class men turning to the classic tropes of scientific racism—most often derived from long-standing popular stereotypes in the first place—to reinforce their sense of national belonging makes perfect sense, as does the ease with which the popular classes throughout Mexico took up norteño Sinophobia.

The centrality of Sinophobia to the construction of national racial identity was hardly unique to Mexico. As immigration historian Erika Lee explains, “national ideas about racial difference and systems of racial ordering were, in fact, highly interactive and transnational processes. Nation-states developed their own understandings of ethnic and cultural differences through transnational connections and comparisons.”Footnote 85 This was certainly true in turn-of-the-century Mexico with its long history of racial hierarchies and transpacific commerce, and its close contemporary connections to transnational industries like mining and railroads, including those in the western United States, where racist exclusion of Chinese workers was the law of the land. And it was true in other parts of Latin America as well.

In the introduction to her history of Sinophobia in Brazil, Ana Paulina Lee argues that “[US-based] narratives that constructed the idea of a yellow race made possible the psychological and cultural landscape that paved the way for race-based restrictions and exclusions that were then applied to Chinese people throughout the Americas and around the rest of the globe. Discourses of Chineseness did the cultural work of defining the exclusionary logic of racialized nationalisms that determines not only access to full citizenship rights but also recognition within the state's ethical responsibility to life.”Footnote 86 The ephemeral contribution of the turn-of-the-century Mexico City penny press to these hemispheric discourses of Chineseness lies not in its authoritative role in “defining the exclusionary logic of racialized nationalism,” but through its insidious insertion of Sinophobic attitudes into the everyday language of racism, where it prepared the ground for elite-driven consolidation of national racial formations in Mexico and elsewhere in the Americas.