1. Introduction

This paper investigates how companies build dynamic capabilities through business portfolio reconfiguration and how organizational slack, capability, and ownership structure moderate the relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance in the context of an emerging economy (Arndt, Reference Arndt2019). Specifically, we suggest that companies develop and build their dynamic capabilities by adding, deleting, reorganizing, and combining their business units (Chakrabarti, Reference Chakrabarti2015; Eisenhardt & Brown, Reference Eisenhardt and Brown1999; Hamel, Doz, & Prahalad, Reference Hamel, Doz and Prahalad1989; Karim, Reference Karim2006; Karim & Capron, Reference Karim and Capron2016). In addition, in an emerging economy, the development and growth of companies also might largely rely on their organizational slack, capability, and social networks (Barney, Reference Barney1991; DeVanna & Tichy, Reference DeVanna and Tichy1990; Galaskiewicz & Zaheer, Reference Galaskiewicz and Zaheer1999; Granovetter, Reference Granovetter1985; Gulati, Reference Gulati1998, Reference Gulati1999; Gulati, Nohria, & Zaheer, Reference Gulati, Nohria and Zaheer2000; Perry-Smith & Shalley, Reference Perry-Smith and Shalley2003; Sharfman, Wolf, Chase, & Tansik, Reference Sharfman, Wolf, Chase and Tansik1988; Van Gundy, Reference Van Gundy and Isaksen1987). In this study, we translate a company's social network into the structure of ownership, including state, domestic, and foreign entities (Ozer & Zhang, Reference Ozer and Zhang2015; Xia & Walker, Reference Xia and Walker2015). Accordingly, the primary research question in this study asks: What is the effect of business portfolio reconfiguration on firm performance in an emerging economy? Our second research question also is addressed: What are the moderating effects of organizational slack, capability, and ownership structure on the relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance?

Dynamic capability has become an influential theory in business studies, with a considerable body of literature devoted to the subject since the 1990s (Barreto, Reference Barreto2010). Companies can build up their dynamic capabilities by acquiring, reshaping, and reorganizing resources to learn or create new value and shape the implementation of strategies to reconfigure their business portfolios (Karim, Reference Karim2006; Karim & Capron, Reference Karim and Capron2016). Specifically, for reconfiguring a company's dynamic capabilities, two streams of research emerge (Eisenhardt & Martin, Reference Eisenhardt and Martin2000). One stream focuses on the integration and reconfiguration of internal resources and processes (Clark & Fujimoto, Reference Clark and Fujimoto1991; Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt1989; Eisenhardt & Martin, Reference Eisenhardt and Martin2000; Helfat & Raubitschek, Reference Helfat and Raubitschek2000). In other words, companies can build their dynamic capabilities by integrating internal resources such as learning and benchmarking from best practices within their organizations (Helfat, Reference Helfat1997; Helfat & Raubitschek, Reference Helfat and Raubitschek2000) or reconfiguring the embedded knowledge and managerial expertise to shape the quality of their strategic choices and actions (Eisenhardt & Brown, Reference Eisenhardt and Brown1999; Girod & Whittington, Reference Girod and Whittington2015, Reference Girod and Whittington2017). The other stream of research tackles the gain or release of resources to external organizations, learning from external partners, or forming alliances (Bakker, Reference Bakker2016; Capron, Dussauge, & Mitchell, Reference Capron, Dussauge and Mitchell1998; Chakrabarti, Reference Chakrabarti2015; Eisenhardt & Brown, Reference Eisenhardt and Brown1999; Eisenhardt & Martin, Reference Eisenhardt and Martin2000; Gulati, Reference Gulati1999; Hamel, Doz, & Prahalad, Reference Hamel, Doz and Prahalad1989; Karim, Reference Karim2006; Karim & Capron, Reference Karim and Capron2016; Karim & Mitchell, Reference Karim and Mitchell2000, Reference Karim and Mitchell2004; Sull, Reference Sull1999).

However, little research has explored how business portfolio reconfiguration shapes a company's dynamic capabilities in emerging economies (Karim & Capron, Reference Karim and Capron2016). The current literature on reconfiguration mostly investigates issues regarding the use of reconfiguration as a process for growth (Karim, Reference Karim2006; Karim & Mitchell, Reference Karim and Mitchell2000), retrenchment (Bergh, Reference Bergh1997; Capron, Mitchell, & Swaminathan, Reference Capron, Mitchell and Swaminathan2001), or globalization (Chakrabarti, Vidal, & Mitchell, Reference Chakrabarti, Vidal and Mitchell2011; Koza, Tallman, & Ataay, Reference Koza, Tallman and Ataay2011). However, few efforts have been devoted to the interplay of growth and retrenchment, achieved by implementing business portfolio reconfiguration (Karim & Capron, Reference Karim and Capron2016; Kaul, Reference Kaul2012). Similarly, the moderating roles of organizational slack and capabilities embedded within the company have not yet been widely considered by researchers. Compared to the existing research, studies generally focus on environmental dynamisms driving the consequences of reconfigurations (Girod & Whittington, Reference Girod and Whittington2017); however, this study stresses the importance of the roles of internal resources and capabilities. Furthermore, in emerging economies, social networks play an important role in business practices and also might deserve attention (Chen, Lei, & Hsu, Reference Chen, Lei and Hsu2019; Kurt & Kurt, Reference Kurt and Kurt2020; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Sánchez-Riofrío, Guerras-Martín, & Forcadell, Reference Sánchez-Riofrío, Guerras-Martín and Forcadell2015). Finally, prior research on business portfolio reconfiguration has shown mixed results on subsequent firm performance. Although some have suggested that reconfiguration creates value by improving efficiency and economies of scope (Karim & Capron, Reference Karim and Capron2016), others have submitted that reconfiguration might actually impede a company's performance (Bakker, Reference Bakker2016; Feldman, Reference Feldman2014; Girod & Whittington, Reference Girod and Whittington2017; Vidal & Mitchell, Reference Vidal and Mitchell2015). Neutral relationships also have been observed in the literature (Vidal & Mitchell, Reference Vidal and Mitchell2015). This study intends to fill these research gaps and contribute to the literature by proposing a U-shaped relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance; it also considers the influence of organizational slack, capability, and ownership structure on business portfolio reconfiguration.

Accordingly, we use the perspectives of dynamic capabilities (Barreto, Reference Barreto2010; Teece & Pisano, Reference Teece and Pisano1994; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, Reference Teece, Pisano and Shuen1997), the resource-based view (RBV) (Barney, Reference Barney1991; Mahoney & Pandian, Reference Mahoney and Pandian1992; Penrose, Reference Penrose1959; Prahalad & Hamel, Reference Prahalad and Hamel1990; Wernerfelt, Reference Wernerfelt1984), and social networks (Arndt, Reference Arndt2019; DeVanna & Tichy, Reference DeVanna and Tichy1990; Galaskiewicz & Zaheer, Reference Galaskiewicz and Zaheer1999; Granovetter, Reference Granovetter1985; Gulati, Reference Gulati1998; Gulati, Nohria, & Zaheer, Reference Gulati, Nohria and Zaheer2000; Perry-Smith & Shalley, Reference Perry-Smith and Shalley2003; Van Gundy, Reference Van Gundy and Isaksen1987) to construct our theoretical foundation and propose hypotheses. To test these hypotheses, we draw on the Taiwan Economy Journal (TEJ) database and include observations from both the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets in China from 2008 to 2017. This database has been widely adopted by researchers in management fields (e.g., Chen and Jaw, Reference Chen and Jaw2014; Chung and Luo, Reference Chung and Luo2013; Li, Reference Li2018; Su and Lee, Reference Su and Lee2013), which ensures its credibility for conducting empirical research in both Taiwan and China.

Our empirical results suggest a U-shaped relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance because of the interactions among the negative effects of explicit and implicit costs as well as the positive effects of building dynamic capabilities and optimizing efficiency. In addition, this study utilizes the RBV perspective to discuss the moderating roles of organizational slack and capabilities. Organizational slack is generally considered the cushion of actual or potential resources that allow an organization to adapt successfully to internal pressures for adjustment or to external pressures for change (Bourgeois, Reference Bourgeois1981: 30). Our empirical results suggest that more organizational slack available within an organization makes the U-shaped relationship less pronounced, whereas research and development (R&D) and marketing capability make the U-shaped relationship more pronounced. More organizational slack available within a company could give managers more freedom to select strategic moves and decrease the scrutiny for conducting reviews to invest in new projects, which increases the explicit and implicit costs of identifying better targets for adding or withdrawing resources. Nonetheless, R&D and marketing capabilities can enhance a company's knowledge about technological value and breakthroughs and offer the necessary market intelligence for directing resource allocation, which potentially reduces the negative effects of explicit and implicit costs. Finally, by considering social network theory, we investigate the interactions of ownership structure on the relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance in the context of developing countries. Both state and domestic ownership make the U-shaped relationship less pronounced, whereas foreign ownership makes the relationship more pronounced, with an insignificant coefficient to empirically support this observation. State and domestic ownership can become constraints on a company's selections of businesses in which to add or reduce investment and force the company to choose undisciplined investments, which increase the explicit and implicit costs to successfully arrange resources for building dynamic capabilities by investing in new businesses or withdrawing resources from current units. Finally, although foreign ownership potentially offers advantages for building dynamic capabilities through better managerial recommendations, the complications of local markets make those effects less effective in an emerging economy such as China. The empirical results generally support our hypotheses and generate some theoretical and practical implications.

We fill this research gap by addressing ways to build dynamic capabilities through business portfolio reconfiguration (Teece, Reference Teece2018). A company can learn to develop new technology and gain market intelligence from the invested organizations, thereby keeping up to date with industry trends for better performance (Girod & Whittington, Reference Girod and Whittington2015, Reference Girod and Whittington2017; Karim, Reference Karim2006). In addition, we provide another perspective on a company owned by other entities. The ownership structure constructs both business and political ties, which have been suggested to positively affect firm performance (Beckman & Haunschild, Reference Beckman and Haunschild2002; Chen, Li, Liu, & Peng, Reference Chen, Li, Liu and Peng2014; Chen, Li, Su, & Sun, Reference Chen, Li, Su and Sun2011; Hillman, Withers, & Collins, Reference Hillman, Withers and Collins2009; Kor & Sundaramurthy, Reference Kor and Sundaramurthy2009; Xia & Walker, Reference Xia and Walker2015). However, when the focal issue changes to the effects of business portfolio reconfiguration on firm performance, a company's business and political ties can reduce the company's autonomy to select appropriate targets for allocating resources and making investments (Gu, Hung, & Tse, Reference Gu, Hung and Tse2008; Uzzi, Reference Uzzi1997; Warren, Dunfee, & Li, Reference Warren, Dunfee and Li2004).

In terms of practice, managers in an emerging economy should consider business portfolio reconfiguration as a venue for building their dynamic capabilities to better improve firm performance (Eisenhardt & Martin, Reference Eisenhardt and Martin2000). They also should be aware of the influences of their business and political ties to minimize any negative impacts on selecting suitable investment targets to secure the benefit for their business portfolio reconfiguration (Filatotchev, Liu, Buck, & Wright, Reference Filatotchev, Liu, Buck and Wright2009; Gu, Hung, & Tse, Reference Gu, Hung and Tse2008; Hillman, Reference Hillman2005; Uzzi, Reference Uzzi1997; Warren, Dunfee, & Li, Reference Warren, Dunfee and Li2004).

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next two sections present the research hypotheses and the study's methodology. A presentation of the empirical results of our study follows, and the last section proposes theoretical and managerial implications and offers suggestions for further research.

2. Research background and hypotheses

In an emerging economy, the business environment is dynamic and complex (Acquaah, Reference Acquaah2007; Filatotchev et al., Reference Filatotchev, Liu, Buck and Wright2009; Peng & Heath, Reference Peng and Heath1996; Sheng, Zhou, & Li, Reference Sheng, Zhou and Li2011). To quickly catch up to industry trends, companies can try to build their dynamic capabilities by adjusting business units to reconfigure their business portfolios (Andrevski, Brass, & Ferrier, Reference Andrevski, Brass and Ferrier2016; Asgari, Singh, & Mitchell, Reference Asgari, Singh and Mitchell2017; Bakker, Reference Bakker2016). Moreover, to exploit the advantages generated by the reconfiguration of the business portfolio, organizational slack and capabilities can play critical roles in driving the interactions between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance (Girod & Whittington, Reference Girod and Whittington2015, Reference Girod and Whittington2017; Helfat, Reference Helfat1997; Karim, Reference Karim2006; Karim & Capron, Reference Karim and Capron2016). More importantly, in an emerging economy such as China, social networks among companies, managers, and political entities also might develop varying relationships between business portfolio reconfiguration and companies' performance (Acquaah, Reference Acquaah2007; Beckman & Haunschild, Reference Beckman and Haunschild2002; Gulati, Reference Gulati1999; Luo, Reference Luo2003). This study merges the perspectives of dynamic capabilities (Barreto, Reference Barreto2010; Teece & Pisano, Reference Teece and Pisano1994; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, Reference Teece, Pisano and Shuen1997), RBV (Barney, Reference Barney1991; Mahoney & Pandian, Reference Mahoney and Pandian1992; Penrose, Reference Penrose1959; Prahalad & Hamel, Reference Prahalad and Hamel1990; Wernerfelt, Reference Wernerfelt1984), and social networks (DeVanna & Tichy, Reference DeVanna and Tichy1990; Galaskiewicz & Zaheer, Reference Galaskiewicz and Zaheer1999; Granovetter, Reference Granovetter1985; Gulati, Reference Gulati1998; Gulati, Nohria, & Zaheer, Reference Gulati, Nohria and Zaheer2000; Perry-Smith & Shalley, Reference Perry-Smith and Shalley2003; Van Gundy, Reference Van Gundy and Isaksen1987) to outline our research framework and propose hypotheses.

The following section begins by hypothesizing a U-shaped relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance. It then presents hypotheses related to two groups of moderators in this relationship. One group is explained by RBV and includes the effects of organizational slack, R&D capability, and marketing capability. The other group is associated with different types of social networks and includes the effects of state ownership, domestic ownership, and foreign ownership.

2.1 Business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance

This study defines business portfolio reconfiguration as a company pursuing strategic alignment among strategic goals, resources, and dynamic capabilities by adding, splitting, transferring, merging, or eliminating business units without changing the fundamental structural principles (Barreto, Reference Barreto2010; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, Reference Teece, Pisano and Shuen1997). Dynamic capability refers to a firm's ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address the rapidly changing environment and create competitive advantages to improve firm performance (Barreto, Reference Barreto2010; Teece, Reference Teece2007, Reference Teece2018; Teece & Pisano, Reference Teece and Pisano1994; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, Reference Teece, Pisano and Shuen1997). Specifically, companies try to maximize their value by reconfiguring their business portfolio to explore the optimal combination of resources and capabilities (Teece, Reference Teece2018). In other words, business portfolio reconfiguration is a strategic move that can help companies generate further dynamic capabilities through a continuous search for the optimal combinations of resources and capabilities. In such a way, companies can add, delete, reorganize, or combine internal business units to optimize performance. In this sense, reconfiguration encompasses sensing and seizing capabilities to enhance long-run performance and can be seen as the microfoundation of dynamic capabilities (Karim & Capron, Reference Karim and Capron2016; Teece, Reference Teece2007). Therefore, the dynamic capabilities built by implementing the strategic moves of business portfolio reconfigurations provide companies with ‘distinct skills, processes, procedures, organizational structures, decision rules, and disciplines’ (Teece, Reference Teece2007: 1319). If the market approaches the new strategic moves as risky, irrelevant, or unprofitable, it will negatively react to the new business portfolio, and managers will adjust them accordingly to optimize stock prices (Bergh, Reference Bergh1995; Holzmayer & Schmidt, Reference Holzmayer and Schmidt2020; Montgomery & Singh, Reference Montgomery and Singh1984). Additionally, managers also might consider where they can allocate resources and apply their capabilities to effectively manage those resources and consistently find the optimal combination of resources and capabilities to ensure their profitability (Markides, Reference Markides1992; Schommer, Richter, & Karna, Reference Schommer, Richter and Karna2019). Therefore, we maintain that in an emerging economy, the reconfiguration of business portfolios better captures the expansion and development of dynamic capabilities within an organization, which potentially impacts the company's financial performance (Allen, Qian, & Qian, Reference Allen, Qian and Qian2005).

Some researchers have suggested that reconfiguration allows companies to establish better dynamic capabilities to improve firm performance (Karim, Reference Karim2006; Karim & Mitchell, Reference Karim and Mitchell2004); other researchers have found that reconfiguration exposes a company to some managerial risks, which potentially reduce the company's opportunities to gain advantages by the reconfiguration of its business (Bakker, Reference Bakker2016; Vidal & Mitchell, Reference Vidal and Mitchell2015). To address these mixed findings in the literature, we suggest that a U-shaped relationship exists between a company's reconfiguration and its performance. We explain this relationship by considering the costs and benefits associated with business portfolio reconfiguration and their dynamics across lower, intermediate, and higher levels of business portfolio reconfiguration.

The negative impacts of reconfiguration can be categorized as explicit and implicit costs. Explicit costs directly link to the financial outlay of investing in a new company, and in many cases, the company can overestimate the value of the investment. Overinvesting in the target could result from information asymmetry, which drives the company to overestimate the benefits that the target will bring to its business. To invest in more valuable targets, companies can pay more when bidding for available shares against other potential buyers. Finally, if companies close a current business, severance payments or compensation also could contribute to the direct financial outflow (Joy, Reference Joy2018).

Implicit costs refer to the expenses associated with searching for, evaluating, and managing suitable targets for reconfiguring businesses (Asgari, Singh, & Mitchell, Reference Asgari, Singh and Mitchell2017). Information asymmetry makes it costly for companies to determine which targets are valuable investments. In particular, acquiring complete information about a new investment target is nearly impossible and very expensive (Bass, McGregor, & Walters, Reference Bass, McGregor and Walters1977). Additionally, it also is costly for companies to manage the chaos and employee dissatisfaction that arise after business units are cut (Joy, Reference Joy2018).

When reconfiguring their business portfolio to improve firm performance, companies could see two potential benefits: building dynamic capability and optimizing efficiency. A company could build its dynamic capability by managing its business portfolio and learning from its businesses in different industries or market segments (Barreto, Reference Barreto2010; Sánchez-Riofrío, Guerras-Martín, & Forcadell, Reference Sánchez-Riofrío, Guerras-Martín and Forcadell2015; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, Reference Teece, Pisano and Shuen1997). Managers also can manage their business portfolios to strengthen the competitive advantage of their companies and receive the advantage of diversification (Amit & Livnat, Reference Amit and Livnat1988; Bettis, Reference Bettis1981; O'Brien, David, Yoshikawa, & Delios, Reference O'Brien, David, Yoshikawa and Delios2014; Rumelt, Reference Rumelt1982). Optimizing efficiency indicates that by investing in or withdrawing resources from the invested companies or business units, a company builds a more appropriate investment portfolio to optimize its managerial efficiency, which eventually contributes to better performance (Karim & Capron, Reference Karim and Capron2016). In such a way, the company shares risks with its invested companies, thereby becoming more flexible in gaining new industrial knowledge, recognizing business trends and moving to other potential markets to pursue better profitability (Pennings, Barkema, & Douma, Reference Pennings, Barkema and Douma1994; Zollo & Winter, Reference Zollo and Winter2002). Additionally, in an emerging economy, it is critical to capture industry trends to profit by investing in innovative companies (Danneels, Reference Danneels2002; Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt1989; Eisenhardt & Tabrizi, Reference Eisenhardt and Tabrizi1995; Galunic & Eisenhardt, Reference Galunic and Eisenhardt2001; Galunic & Rodan, Reference Galunic and Rodan1998; Powell, Koput, & Smith-Doerr, Reference Powell, Koput and Smith-Doerr1996).

Different scenarios apply at different levels of business portfolio reconfiguration. With a lower level of business portfolio reconfiguration, companies continue conducting business within their original industries and market segments and implement a limited number of business unit changes. Companies doing business within the same fields might have enjoyed a comfortable profit and have valuable resources with which to compete in the marketplace. Accordingly, if they are successful with their current business portfolio, they will not consider changing it as a strategic choice (Wernerfelt & Karnani, Reference Wernerfelt and Karnani1987). Under this scenario, we suggest that the costs and benefits associated with business portfolio reconfiguration are limited. However, since the company's current business portfolio could produce sufficient profits based on the available resources and current capabilities within the company, we propose better firm performance in this scenario.

Implementing more business unit changes implies that companies want to acquire new knowledge or business opportunities or to leave their current business and reallocate resources to other areas in which the marginal benefit is higher. At this intermediate level of business portfolio reconfiguration, the explicit and implicit costs are high, but the opportunities for building dynamic capability or optimizing efficiency are limited. In particular, the explicit costs for adding or eliminating business units are directly incurred (Joy, Reference Joy2018; Weber & Camerer, Reference Weber and Camerer2003), which could hinder the companies' performance at the intermediate level of business portfolio reconfiguration. Additionally, as the number of units changed is limited, companies do not have enough opportunities to learn or exploit advantages from these limited changes. As a result, a lower degree of firm performance is proposed under this scenario.

When companies pursue a higher level of business portfolio reconfiguration, the opportunities for building dynamic capability and optimizing efficiency may be stronger, and the explicit and implicit costs may be controlled. At this higher level of business portfolio reconfiguration, companies quickly absorb or release resources to build up dynamic capability by learning from the new business units in other industries or to optimize efficiency by adding or eliminating business units (Arthur & Huntley, Reference Arthur and Huntley2005; Lieberman, Reference Lieberman1987). In addition, as managers gain more experience managing the strategy of investing in new businesses or withdrawing resources from existing investments, they should be more capable of finding profitable investment opportunities to control explicit costs and to explore, evaluate, and manage their businesses to reduce the implicit costs associated with business portfolio reconfiguration.

As a result, firm performance is positive at the lower level of business portfolio reconfiguration. When business portfolio reconfiguration is at the intermediate level, costs are directly incurred, but benefits are not guaranteed. Therefore, the corresponding firm performance is reduced. Finally, at a higher level of business portfolio reconfiguration, the opportunities for building dynamic capability and optimizing efficiency become greater (Karim & Capron, Reference Karim and Capron2016). Additionally, as managers become more experienced in managing business reconfiguration, explicit and implicit costs are likely to be well controlled. Therefore, the aggregated effects increase the positive impacts on firm performance at the higher level of business portfolio reconfiguration. Following this line of logic, we propose our first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: There will be a U-shaped relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance.

2.2. The moderating roles of organizational slack and capabilities

The theoretical foundation of RBV emerged in the late 1950s (Penrose, Reference Penrose1959) and became influential in the early 1990s (Barney, Reference Barney1991; Mahoney & Pandian, Reference Mahoney and Pandian1992; Prahalad & Hamel, Reference Prahalad and Hamel1990; Wernerfelt, Reference Wernerfelt1984). Building on this stream of research, organizational slack and capabilities have been identified as key drivers influencing firm performance (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Li, Su and Sun2011; Guo, Zhou, Zhang, Hu, & Song, Reference Guo, Zhou, Zhang, Hu and Song2020; Kotabe, Srinivasan, & Aulakh, Reference Kotabe, Srinivasan and Aulakh2002; Morgan, Vorhies, & Mason, Reference Morgan, Vorhies and Mason2009; Tan & Peng, Reference Tan and Peng2003; Wu, Lin, & Chen, Reference Wu, Lin and Chen2007; Zaheer & Bell, Reference Zaheer and Bell2005).

2.2.1. The moderating effect of organizational slack on the U-shaped relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance

A higher level of organizational slack gives an organization more flexibility to make strategic moves, offering top management teams more freedom (Chen & Huang, Reference Chen and Huang2010; Tan & Peng, Reference Tan and Peng2003). Managers can exploit the slack and invest it in projects that could generate greater returns with higher risk or provide immediate profits when the uncertainty of the environment is high if their companies are driven by short-term profits (Chen & Huang, Reference Chen and Huang2010; Tan & Peng, Reference Tan and Peng2003). As a result, unrealistic expectations for greater returns and competition for resources among managers can decrease the benefit of organizational slack and potentially jeopardize firm performance. We submit that the unrealistic expectations for greater returns with higher risk and undisciplined investment strategies increase the explicit costs for a company to make new investments when more organizational slack is available. Moreover, competition among managers increases the implicit costs for a company to plan for, manage, and evaluate new investment opportunities efficiently and effectively (Jensen, Reference Jensen1986, Reference Jensen1993).

Under this scenario, we maintain that the higher the slack available within an organization, the lower the performance the organization may achieve. In other words, managers take risks for unrealistic investments with great returns or devote too much attention to competing for slack against other departments or projects, which does not maximize long-term firm performance. Accordingly, we suggest that the higher levels of organizational slack available within an organization, the lower performance the company achieves, which results from the higher explicit cost for unrealistic and undisciplined investments in new businesses and the implicit cost associated with planning, managing, and evaluating new investment opportunities for business portfolio reconfiguration.

Hypothesis 2a: Organizational slack moderates the U-shaped relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance in such a way that higher levels of organizational slack available within an organization make the U-shaped relationship less pronounced than with lower levels of organizational slack.

2.2.2. The moderating effect of R&D capability on the U-shaped relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance

R&D capability is an important factor in making a company a leader within an industry in developing countries (Fan, Reference Fan2006). In addition, a company's large investment of resources in R&D activities also implies its leadership within a field, which results from the capability to push forward the technological development of its industry. As a result, we maintain that an industry leader is more capable of gathering information on relevant new technological developments (Chesbrough, Reference Chesbrough2010). In this way, such a leader is more likely to detect which new startups or business opportunities offer more potential for profit (Utterback, Reference Utterback1994).

Based on this reasoning, this study suggests that a company with higher levels of R&D capability has the managerial knowledge and capability to share and detect new technological trends and business opportunities, which reduce the explicit costs and implicit costs associated with business reconfiguration (Arun, Reference Arun, Jain and Mnjama2017; Zhou, Zhou, Feng, & Jiang, Reference Zhou, Zhou, Feng and Jiang2019). The company has better knowledge about new technological trends, so it will know which startups or existing companies are developing valuable innovation, thus reducing the possibility of overestimation of the investment value. In addition, the company's increased technological insights help reduce uncertainty regarding whether and where it should arrange resources for reconfiguring its business portfolio, which potentially decreases the implicit costs of its business portfolio reconfiguration.

In summary, a company with higher levels of R&D capability has lower explicit costs associated with business portfolio reconfiguration because of its knowledge about technological trends and the value of new technological breakthroughs, as this knowledge reduces the probability for the company to overestimate the value of new investments. In addition, because the company with higher levels of innovative capability also is more knowledgeable about the industry, the company will be more likely to search for and find suitable investing targets, which generally reduces the implicit costs associated with business portfolio reconfiguration. Accordingly, we suggest the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2b: R&D capability moderates the U-shaped relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance in such a way that higher levels of R&D capability within an organization make the U-shaped relationship more pronounced than do lower levels of R&D capability.

2.2.3. The moderating effect of marketing capability on the U-shaped relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance

A company with higher levels of marketing capability could essentially strengthen its processes of product development, supply chain management, and customer relationship management (Srivastava, Shervani, & Fahey, Reference Srivastava, Shervani and Fahey1999). In particular, a company with higher levels of marketing capability places greater importance on facilitating its business environment for knowledge diffusion and interpersonal relationships among its stakeholders (Bruni & Verona, Reference Bruni and Verona2009; Easterby-Smith, Lyles, & Peteraf, Reference Easterby-Smith, Lyles and Peteraf2009). By doing so, a more marketing-oriented company gains greater comprehensive market intelligence for its industry and stakeholders. As a result, it is more likely to evaluate accurately the potential benefits and value of the current and new business opportunities based on its knowledge of the industry and stakeholders (Vorhies, Orr, & Bush, Reference Vorhies, Orr and Bush2011).

It is critical for a company to control the explicit and implicit costs associated with its business reconfiguration. Having more comprehensive market intelligence to evaluate the value of new business opportunities reduces the likelihood of overpaying for new investments, and therefore, it better manages its explicit costs. In addition, marketing capability also enhances the company's ability to select suitable targets for investment efficiently and effectively, which reduces the implicit costs of searching for and evaluating potential targets for reconfiguration.

In brief, we maintain that a company with better marketing capability has the managerial skills to control the explicit and implicit costs associated with its business portfolio reconfiguration because of its more comprehensive market intelligence and interpersonal relationships among stakeholders. These observations lead to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2c: Marketing capability moderates the U-shaped relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance in such a way that higher levels of marketing capability within an organization make the U-shaped relationship more pronounced than do lower levels of marketing capability

2.3. The moderating role of ownership structure

A company consists of interpersonal and interorganizational relationships and several kinds of social networks (Gulati, Nohria, & Zaheer, Reference Gulati, Nohria and Zaheer2000; Karim, Reference Karim2006; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Xia & Walker, Reference Xia and Walker2015). The literature suggests the existence of at least three types of ties or social networks connecting a company with other individuals and organizations: political, domestic, and foreign (Acquaah, Reference Acquaah2007; Bass, McGregor, & Walters, Reference Bass, McGregor and Walters1977; Douma, George, & Kabir, Reference Douma, George and Kabir2006; Florin, Lubatkin, & Schulze, Reference Florin, Lubatkin and Schulze2003; Li, Zhou, & Shao, Reference Li, Zhou and Shao2009; Luo & Chung, Reference Luo and Chung2013; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Sheng, Zhou, & Li, Reference Sheng, Zhou and Li2011). We discuss each type within this section.

2.3.1. The moderating effect of state ownership on the U-shaped relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance

In a developing economy such as China, the state plays an important role in influencing the development of industries (Guillen, Reference Guillen2000; Hillman, Reference Hillman2005). In some cases, state ownership of a company helps the company gain market power to enjoy better firm performance due to regulations and policies (Faccio, Reference Faccio2006; Hillman, Reference Hillman2005; Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Wu, Li, & Li, Reference Wu, Li and Li2013; Zheng, Singh, & Mitchell, Reference Zheng, Singh and Mitchell2015). However, in terms of business portfolio reconfiguration, state ownership could lose its upsides and reduce managerial freedom to select suitable targets for investment or withdraw resources (Chung, Wang, Huang, & Yang, Reference Chung, Wang, Huang and Yang2016; Faccio, Reference Faccio2010; Fan, Wong, & Zhang, Reference Fan, Wong and Zhang2007; Lin & Si, Reference Lin and Si2010). A greater proportion of state ownership implies stronger influences from the state that might force the company to make decisions based not on professional analyses and market forecasts but largely on the influences of political ties among the party members or state policies (Wu, Li, & Li, Reference Wu, Li and Li2013; Zhang, Tan, & Wong, Reference Zhang, Tan and Wong2015).

Building on the above discussion, we maintain that higher levels of state ownership potentially increase the explicit and implicit costs associated with business portfolio reconfiguration. Managers in highly state-owned companies are likely to lose their freedom to evaluate the true value of a new investment, which might increase the explicit costs associated with investing in other companies. Moreover, because decisions for making new investments could be largely influenced by political interests among the party members or the state's policies, the implicit costs for managing and evaluating the outcomes of those investments also could increase (Sheng, Zhou, & Li, Reference Sheng, Zhou and Li2011).

Therefore, we suggest that while the state ownership of a company could be a positive driver for improving firm performance in some situations (Acquaah, Reference Acquaah2007; Claessens, Feijen, & Laeven, Reference Claessens, Feijen and Laeven2008; Hillman, Withers, & Collins, Reference Hillman, Withers and Collins2009), it also might be a negative factor when the company starts to invest in other companies. Managers might be influenced by political ties and state policies rather than depending on professional analyses and focusing on maximizing shareholders' value, which drives up the explicit and implicit costs of business portfolio reconfiguration. We hereby provide the next hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3a: State ownership moderates the U-shaped relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance in such a way that higher levels of state ownership within an organization make the U-shaped relationship less pronounced than do lower levels of state ownership.

2.3.2. The moderating effect of domestic ownership on the U-shaped relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance

The interrelationships among local companies and individual investors can be a venue for a company to exploit necessary resources and social capital to enhance its operations in the market (Hillman, Withers, & Collins, Reference Hillman, Withers and Collins2009). Especially in an emerging economy, maintaining good relationships with domestic institutions and individuals can provide the company with more competitive advantages (Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000). In many cases, however, the relationships among local companies or individual investors also have downsides for a company's operations (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Wang, Huang and Yang2016). In this study, we explore the relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance. It is most likely that a company's social networks among domestic companies and individuals influence its operations by the reciprocal obligations required by its network partners, which increase the firm's explicit costs for investing in new businesses or withdrawing resources, because its decisions largely result from local connections and the requirements of its social ties (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Wang, Huang and Yang2016; Wang & Chung, Reference Wang and Chung2013). In addition, because of special connections among new businesses and the company, managers are less likely to manage those investments efficiently, which results in higher implicit costs associated with those new investments.

Hypothesis 3b: Domestic ownership moderates the U-shaped relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance in such a way that higher levels of domestic ownership within an organization make the U-shaped relationship less pronounced than do lower levels of domestic ownership.

2.3.3. The moderating effect of foreign ownership on the U-shaped relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance

In developing countries, a company with investments by foreign companies, institutes, or individuals is generally considered to have better potential for future development (Carney, Estrin, Liang, & Shapiro, Reference Carney, Estrin, Liang and Shapiro2018; Forsgren & Johanson, Reference Forsgren and Johanson2014). Such investments also make it likely that the company has more opportunities and connections for entering foreign markets, which can improve the company's performance (Armario, Ruiz, & Armario, Reference Armario, Ruiz and Armario2008; Choi & Beamish, Reference Choi and Beamish2013). Because foreign investors have better managerial and market knowledge (Johanson & Mattsson, Reference Johanson, Mattsson, Forsgren, Holm and Johanson2015; Johanson & Vahlne, Reference Johanson and Vahlne1977), they will try to affect the invested companies' decisions on selecting investment targets to secure their returns.

Because foreign investors tend to influence companies to ensure profitability, they are more willing to share their market intelligence, which reduces the explicit costs for local companies' business reconfiguration. In addition, they also can try to transfer managerial skills to local companies for managing their business portfolios and thus better control the implicit costs associated with managing a more diversified business portfolio, which ultimately will improve the performance of their investment.

In summary, this study maintains that foreign investors help companies in developing countries learn better market intelligence and managerial skills to reduce the explicit and implicit costs associated with business portfolio reconfiguration. Better market intelligence transferred from foreign investors will reduce the possibility that a company will overestimate the value of a potential investment. In addition, skills for managing a widely diversified business portfolio can decrease the implicit costs for tackling the business portfolio reconfiguration for the local companies. Hence, we propose our final hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 3c: Foreign ownership moderates the U-shaped relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance in such a way that higher levels of foreign ownership within an organization make the U-shaped relationship more pronounced than do lower levels of foreign ownership.

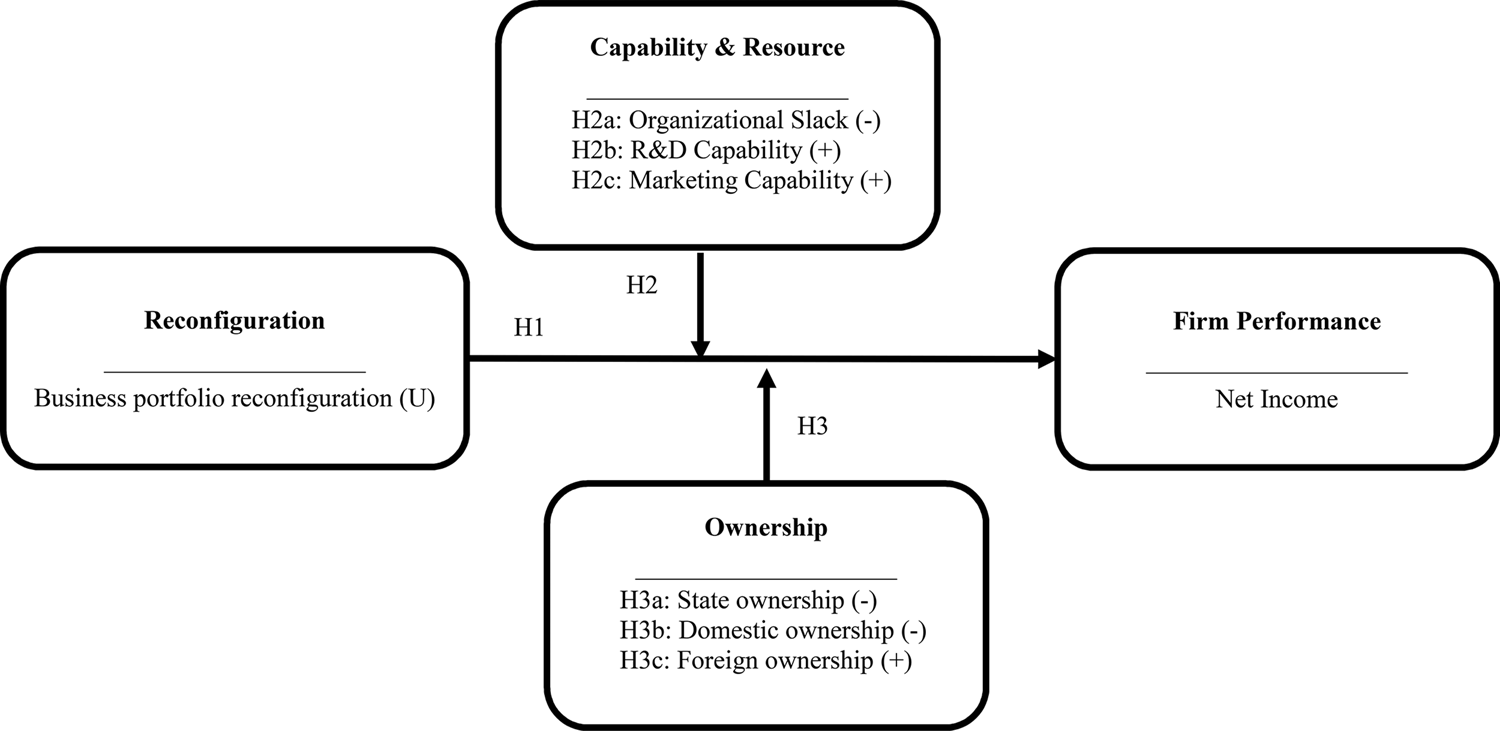

Figure 1 shows the research framework of this study, which examines the curvilinear relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance as well as the moderating roles played by organizational slack, capabilities, and ownership structure.

Figure 1. Conceptual model.

3. Model and methodology

3.1 Data collection and sample

The primary data source for this study is drawn from the TEJ database founded in 1990. Similar to the COMPUSTAT database in the US, TEJ collects firm-level information in Taiwan and recently extended its scope to China and major economies around Southeast Asia (Chen & Jaw, Reference Chen and Jaw2014). Therefore, TEJ has become one of the reliable resources for conducting empirical research in both China and Taiwan, and many articles using this data source have been published in peer-reviewed journals (e.g., Chen and Jaw, Reference Chen and Jaw2014; Chung and Luo, Reference Chung and Luo2013; Li, Reference Li2018; Su and Lee, Reference Su and Lee2013). We draw data from the Chinese market due to its rapid economic development and the dynamic growth of industries and companies (Barboza, Reference Barboza2010; Zhang, Tse, Dai, & Chan, Reference Zhang, Tse, Dai and Chan2017), which provide some advantages for studying business portfolio reconfiguration. Moreover, the literature on reconfiguration generally pays attention to developed economies, and relatively fewer efforts have been made to study reconfiguration issues in the contexts of emerging economies (Karim & Capron, Reference Karim and Capron2016). Therefore, because these observations are from the Chinese market, the sampling population may enhance the significance and generalizability of this study and capture our focal interests.

We collect data from a ten-year window between 2008 and 2017 and obtain 26,151 firm-year observations. The final dataset consists of 3,508 individual firms publicly traded on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets in China, with an average of 7.46 years listed on this panel (standard deviation 3.34) to test our hypotheses.

3.2 Measures

3.2.1 Dependent variable: Firm performance (FP)

In this study, firm performance is measured by net income, which is operationalized by taking revenues and adjusting for interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization in a given year t + 1 (Acquaah, Reference Acquaah2007; Barth, Beaver, & Landsman, Reference Barth, Beaver and Landsman1998). We employ net income to capture firm performance because it is suggested that ratio measures (i.e., ROA or ROE) may be more likely to exaggerate the results of focal relationships (Wiseman, Reference Wiseman, Ketchen and Berg2009). Moreover, we maintain that in developing countries, a ratio measurement may be more likely to be affected by a firm's accounting standards and principles (Firth, Mo, & Wong, Reference Firth, Mo and Wong2005; Wang & Wu, Reference Wang and Wu2011).

3.2.2 Independent variable: Business portfolio reconfiguration

Overall, there are two approaches to measuring reconfiguration. Some studies use news databases and press releases to search for potential reconfiguration activities under the terms ‘reorganization,’ ‘restructuring,’ ‘appointments,’ ‘executive moves,’ and ‘mergers and acquisitions’ to count reconfiguration numbers (Girod & Whittington, Reference Girod and Whittington2015, Reference Girod and Whittington2017). Others measure partner reconfiguration by directly counting add and delete numbers using related databases (Bakker, Reference Bakker2016; Karim, Reference Karim2006). This research adopts the second approach because this study focuses only on business portfolio reconfiguration, not all reconfiguration activities. This research assesses the business portfolio reconfiguration by calculating the absolute difference in business portfolio numbers between year t and year t-1 (Bergh & Lawless, Reference Bergh and Lawless1998). For example, in 2007, Sinopec, the China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation, invested in 10 companies. In 2006, Sinopec invested in 13 companies. The investment number change in 2007 is thus 3. Accordingly, by using this measurement, we may better capture the effects of business portfolio reconfiguration as defined in this study. This research measures the reconfiguration data from 2007 to 2017, and all the relevant investment information is gathered from the TEJ database.

3.2.3 Moderator group 1: Organizational slack, R&D capability, and Marketing capability

Organizational slack is captured by the function of the current ratio, which is current assets divided by current liabilities (Cheng & Kesner, Reference Cheng and Kesner1997; Singh, Reference Singh1986). This form of slack is more likely to be redeployed to other places and usages. As a result, it allows higher levels of managerial freedom for managers to allocate resources to projects, which may positively affect the performance of their departments. Although it may positively affect a specific department's performance, it is more likely to jeopardize firm performance as a whole due to the emphasis on short-term profit, higher levels of environmental uncertainty, and the competition for resource allocation among managers (Chen & Huang, Reference Chen and Huang2010). R&D capability is measured by the total number of R&D staff divided by the total number of employees within an organization (Fritsch & Lukas, Reference Fritsch and Lukas2001). Marketing capability is the ratio measured by the total number of marketing staff over the total number of employees within an organization (Carlin, Estrin, & Schaffer, Reference Carlin, Estrin and Schaffer2000). We access the firm characteristics from the TEJ database to compute these moderators.

3.2.4 Moderator Group 2: State ownership, Domestic ownership, and Foreign ownership

State ownership, domestic ownership, and foreign ownership are the percentage of restricted shares that are owned by state, domestic, and foreign individuals and institutes, respectively. State ownership includes the ownership of the national and local government entities as well as other state-owned institutes (Faccio, Masulis, & McConnell, Reference Faccio, Masulis and McConnell2006). Domestic ownership is the ownership of domestic entities other than those of state ownership, which includes domestic individual investors and institutes (Douma, George, & Kabir, Reference Douma, George and Kabir2006). Foreign ownership is the ownership of foreign individuals and institutes (Douma, George, & Kabir, Reference Douma, George and Kabir2006). There are generally two approaches to calculate the percentage of ownership. One is utilizing the survey questionnaire to ask respondents about the percentage of ownership (Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Sheng, Zhou, & Li, Reference Sheng, Zhou and Li2011). The other approach is to calculate the percentage by archival data (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Li, Su and Sun2011; Douma, George, & Kabir, Reference Douma, George and Kabir2006; Faccio, Masulis, & McConnell, Reference Faccio, Masulis and McConnell2006). This study adopts the second approach to better capture the changes in ownership structure across different years, which is relatively harder to achieve by survey questionnaires.

3.2.5 Control variables

In addition to the dependent and independent variables used to test the hypotheses in this study, we also include several control variables to ensure the robustness of the empirical results. First, we control for the salience of companies, which might potentially influence firm performance, which is captured by three variables, including sales volume, firm size and return on equity (ROE). Sales volume is the total revenue in the given year with log transformation. Firm size is the total number of employees with log transformation (Filatotchev et al., Reference Filatotchev, Liu, Buck and Wright2009). ROE, however, is the ratio calculated as net income divided by shareholders' equity. Second, Firm age controls for managerial skills and experience in managing business reconfigurations, which is calculated by the number of years in operation (Luo, Reference Luo2003). Third, we include year and industrial effects by adopting year dummies and the two digits of the industry classification code categorized by the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC). Finally, we also control for the fixed effects of the firm by introducing the firm's company code assigned by the CSRC.

3.3 Analytical method

Regression models are employed in this paper to empirically test our hypotheses. We are interested in knowing the influence of business portfolio reconfiguration on firm performance and the interactions of organizational slack, capabilities, and ownership on this relationship. Because all the variables are contingent, regression models are appropriate for testing our hypotheses, which have also been utilized by many studies within the strategic management literature (Ketchen, Boyd, & Bergh, Reference Ketchen, Boyd and Bergh2008; Shook, Ketchen, Cycyota, & Crockett, Reference Shook, Ketchen, Cycyota and Crockett2003). Specifically, we control for firm-specific effects to better obtain more reliable estimations, and exclude the time-invariant firm-specific factors as well as the effect of regional differences among observed companies (Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge2002).

4. Results

The primary interest of this study is to investigate the interactions between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance as well as the moderating effects of organizational slack, capabilities and ownership on these relationships. In Table 1, we summarize the descriptive statistics of our sample. Table 2 shows the regression results of each model. Model 1 is the baseline model with all control variables. Model 2 and 3 compute the variable of Business portfolio reconfiguration and its squared term, respectively. The coefficient of Business portfolio reconfiguration squared is positive and significant, which statistically supports Hypothesis 1 (p < .001). It suggests that the relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance is curvilinear. In model 6, the interaction terms of Organizational slack (negative, p < .001), R&D capability (positive, p < .001), as well as Marketing capability (positive, p < .01) and Business portfolio reconfiguration squared on Firm performance are all significant, which empirically support Hypothesis 2a 2b 2c. Hypothesis 2a predicts that the higher levels of organizational slack available within an organization may make the curvilinear relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance less pronounced, which is collaborated. Hypothesis 2b concerns that higher levels of R&D capability may make the curvilinear relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance more pronounced, which is held. Hypothesis 2c hypothesizes that higher levels marketing capability may make the U-shaped relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance more pronounced.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and correlationsa

a N = 26,151 (two-tailed test). with absolute value greater than .09 are significant at p < .05.

Table 2. The effects of business portfolio reconfiguration on firm performance in t + 1

IV, Reconfiguration, Reconfiguration SQ; M, Organizational Slack, R&D Capacity, Marketing Capacity, State Ownership %, Domestic Ownership %, Foreign Ownership %.

Note:*** = significant at .001** = significant at .01* = significant at .05 † = significant at .1.

In Model 9, the coefficient of the interaction term of Domestic ownership and business portfolio reconfiguration on Firm performance is negative and significant (p < .05). Hypothesis 3b is, therefore, suggested. Hypothesis 3b predicts that higher levels of domestic ownership may make the U-shaped relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance less pronounced. Finally, however, the coefficients of the interaction terms of State and Foreign ownership and Business portfolio reconfiguration on Firm performance are consistent with the hypothesized directionality but insignificant. The statistical results, therefore, cannot fully support our Hypothesis 3a and 3c. We visualize the moderating effects on the relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance in Figures 2a, 2b, 2c, 3a, 3b and 3c.

Figure 2. (a) The moderating effect of organizational slack on business portfolio reconfiguration to firm performance. (b) The moderating effect of R&D capability on business portfolio reconfiguration to firm performance. (c) The moderating effect of marketing capability on business portfolio reconfiguration to firm performance.

Figure 3. (a) The moderating effect of state ownership on business portfolio reconfiguration to firm performance. (b) The moderating effect of domestic ownership on business portfolio reconfiguration to firm performance. (c) The moderating effect of foreign ownership on business portfolio reconfiguration to firm performance.

In order to ensure the robustness of our results and capture the longer-term effects of business portfolio reconfiguration on firm performance, this study further computes regressions on three-year time lag of net income. In Table 3, we provide the estimations using the dependent variable of net income in time t + 3. The results are generally robust and suggest similar relationships. These results of the robustness test further support our hypotheses, which indicate the direct effect of business portfolio reconfiguration and the moderating effect of organizational capability and slack, and ownership structure on firm performance.

Table 3. The effects of business portfolio reconfiguration on firm performance in t + 3

IV, Reconfiguration, Reconfiguration SQ; M, Organizational Slack, R&D Capacity, Marketing Capacity, State Ownership %, Domestic Ownership %, Foreign Ownership %.

Note:*** = significant at .001** = significant at .01* = significant at .05† = significant at .1.

5. Discussion and conclusion

This research examines the relationships between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance, including the moderating effects of organizational slack, capabilities, and ownership structure. In general, our empirical results support most of our hypotheses, with several interesting findings.

Our empirical results suggest a U-shaped relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance. We maintain that this finding helps to explain the mixed results reported by previous research (Bakker, Reference Bakker2016; Feldman, Reference Feldman2014; Girod & Whittington, Reference Girod and Whittington2017; Karim & Capron, Reference Karim and Capron2016; Vidal & Mitchell, Reference Vidal and Mitchell2015) and implies that the negative effects of reconfiguration gradually diminish as levels of reconfiguration increase. As described in the literature review, the negative effects of reconfiguration come from explicit and implicit costs. The explicit costs are the direct financial outlay and inflated prices for investing in new businesses. The implicit costs include searching for, evaluating, and managing the business portfolio (Asgari, Singh, & Mitchell, Reference Asgari, Singh and Mitchell2017). Moreover, acquiring complete information about new investments is impossible and costly (Bass, McGregor, & Walters, Reference Bass, McGregor and Walters1977). Nevertheless, throughout the reconfiguration process, the negative effects are better controlled when organizational learning is applied. The learning here can be gained either from affinity to the context (Pennings, Barkema, & Douma, Reference Pennings, Barkema and Douma1994) or from cumulative experience (Lieberman, Reference Lieberman1987; Pennings & Harianto, Reference Pennings and Harianto1992). The searching and managing costs are likely to drop as the learning effect rises (Arthur & Huntley, Reference Arthur and Huntley2005; Lieberman, Reference Lieberman1987). Furthermore, the opportunities for building dynamic capacity and optimizing efficiency also gain momentum when a company adopts a higher level of business portfolio reconfiguration. The aggregate effects on the relationship between reconfiguration and performance become positive at a high level of business portfolio reconfiguration, thereby bringing the firm positive effects and keeping the firm aligned with the business environment.

The moderating effects of organizational slack, capability, and ownership structure are also empirically tested in this article. Previous studies tend to focus on the impacts of the business environment when they discuss reconfiguration (Girod & Whittington, Reference Girod and Whittington2017). This study, however, tests several internal factors that have potential moderating effects on the relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance and reveals that organizational slack and domestic ownership negatively moderate the U-shaped relationship between firm performance and business portfolio reconfiguration. However, R&D and marketing capabilities could positively moderate the U-shaped relationship. Although the moderating effects of state ownership and foreign ownership are consistent in direction with our expectations, they are insignificant to fully support the hypothesis.

Organizational slack could be an uncommitted resource allowing managers to invest without considerable constraints. As a result, with abundant resources available within their organizations, managers are more likely to take more risks (Chen & Huang, Reference Chen and Huang2010; Singh, Reference Singh1986) and thus to participate in undisciplined investments in reconfiguration activities (Jensen, Reference Jensen1986, Reference Jensen1993). The risk-taking behaviors and undisciplined investment decisions could lead to inefficient investments that hinder the firm from receiving the benefits from reconfiguration and increase the investment cost due to the loss of managerial control. Domestic ownership and state ownership also have negative moderating effects on the U-shaped relationship. Undisciplined investment decisions can come from administrative interventions by state governments (Yiu, Bruton, & Lu, Reference Yiu, Bruton and Lu2005). Additionally, government owners tend to focus more on allocating financial resources for a nonprofit goal instead of for-profit maximization. Furthermore, in the case of more domestic or state ownership, more related party transactions and investments are performed. Investment decisions that lack discipline and strategy inevitably lead to weak investment performance and thus diminish the benefit of reconfiguration.

R&D and marketing capabilities have been considered key drivers of firm performance (Bruni & Verona, Reference Bruni and Verona2009; Chesbrough, Reference Chesbrough2010; Easterby-Smith, Lyles, & Peteraf, Reference Easterby-Smith, Lyles and Peteraf2009; Utterback, Reference Utterback1994; Vorhies, Orr, & Bush, Reference Vorhies, Orr and Bush2011). A company with higher R&D or marketing capabilities can better capture the technological trends or market intelligence within its industry. As a result, the company is better able to evaluate the value of new business opportunities and has a better capability to manage new businesses. Although we expect higher rates of foreign ownership to lead a company to demonstrate better firm performance, the empirical results do not statistically support this hypothesis. We maintain that in the Chinese market, governmental intervention and local connections are much more influential and outweigh the positive impacts of foreign partners (Li, Poppo, & Zhou, Reference Li, Poppo and Zhou2008).

5.1. Theoretical and managerial implications

The theoretical and managerial implications of this study provide researchers and managers with new directions and insights for emerging countries. This study uses Chinese firms as a sampling population to test our hypotheses. We bring together dynamic capability, RBV, and social network theories to construct our research framework.

We fill the gap in theory and research on building dynamic capabilities through business portfolio reconfiguration in an emerging economy (Teece, Reference Teece2018), which allows a company to quickly respond to changes in the business environment. From the companies it invests in, a firm learns how to develop new technology, gain market intelligence, and keep up to date with industry trends for better performance (Girod & Whittington, Reference Girod and Whittington2015, Reference Girod and Whittington2017; Karim, Reference Karim2006). In addition, we provide another perspective on a company owned by other entities. The ownership structure creates business and political ties to third parties, which have been suggested to have a positive influence on firm performance (Beckman & Haunschild, Reference Beckman and Haunschild2002; Hillman, Withers, & Collins, Reference Hillman, Withers and Collins2009; Kor & Sundaramurthy, Reference Kor and Sundaramurthy2009; Xia & Walker, Reference Xia and Walker2015). However, when the focal issue changes to the effects of business portfolio reconfiguration on firm performance, a company's business and political ties can reduce the company's autonomy in selecting appropriate targets for allocating resources and making or withdrawing investments (Gu, Hung, & Tse, Reference Gu, Hung and Tse2008; Uzzi, Reference Uzzi1997; Warren, Dunfee, & Li, Reference Warren, Dunfee and Li2004).

For managers in an emerging economy, industries transform quickly, and business portfolio reconfiguration is another venue for building their dynamic capabilities to improve their firms' performance (Eisenhardt & Martin, Reference Eisenhardt and Martin2000). Similarly, in developed countries, compared to restructuring, reconfigurations within organizations can also provide companies with more flexibility and responses that are better suited to the environment. Companies in a more dynamic environment can consider reconfigurations as strategic alternatives to pursue better firm performance in more mature industries (Girod & Whittington, Reference Girod and Whittington2017; Hildebrandt, Oehmichen, Pidun, & Wolff, Reference Hildebrandt, Oehmichen, Pidun and Wolff2018; Karim, Reference Karim2006). In addition, companies with better R&D and marketing capabilities can further strengthen their ability to improve firm performance through reconfigurations, thus enabling those companies to respond rapidly to technological trends and business opportunities in their industries. Finally, business and political ties can become constraints for some companies to select suitable investment targets, which then secure a benefit for their business portfolio reconfiguration (Filatotchev et al., Reference Filatotchev, Liu, Buck and Wright2009; Gu, Hung, & Tse, Reference Gu, Hung and Tse2008; Hillman, Reference Hillman2005; Uzzi, Reference Uzzi1997; Warren, Dunfee, & Li, Reference Warren, Dunfee and Li2004). Stronger political ties reduce company autonomy, even if they fulfill their obligations related to political policies. Domestic ties can also increase the possibility of unnecessary and inefficient reconfiguration decisions affected by social ties (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Wang, Huang and Yang2016; Wang & Chung, Reference Wang and Chung2013).

5.2. Limitations and future research

This study reveals the impact of business portfolio reconfiguration on firm performance under different types of contingencies set by organizational slack, capability, and ownership. Our research framework provides a comprehensive range of research settings; however, it also has some limitations that can be addressed through future research.

First, the literature suggests that other theories, such as institutional-based theory, provide perspectives for discussing the relationships among business portfolio reconfiguration, slack, capability, social network, and ownership structure (e.g., Girod and Whittington, Reference Girod and Whittington2017). However, the major interest of this study centered on firm-level theories to explain these relationships and deepen our knowledge in this line of research. We suggest that future studies explore related issues based on institutional-based theory to shed light on the relationships between businesses, state government, and the complex business environment in developing countries.

Second, the empirical data are limited to firms listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges. Therefore, the findings in this research may not reflect the Chinese context as a whole.

Third, business portfolio reconfiguration in this study is measured only in terms of changes in absolute value. Other indicators, such as shareholding percentage change and investment cost change, could be used as research variables in future studies. Researchers could also investigate the effects of adding or eliminating businesses to gain a more comprehensive view of the impacts of business portfolio reconfigurations on firm performance.

Fourth, the strategic management literature has also suggested that the CEO, board, and top management team play a prominent role in directing firms' strategies. Future research might consider the roles these entities play in the relationship between business portfolio reconfiguration and firm performance.

Last, although previous research has indicated a performance lag in reconfiguration (Girod & Whittington, Reference Girod and Whittington2017), the extant theories have not explicitly discussed it. Future studies can further examine and explain time lag issues in business portfolio reconfiguration and test other measurements for long-term firm performance.

With these limitations, this study nevertheless concludes that reconfiguration has both negative and positive effects on firm performance and that organizational slack, capability, and ownership are important criteria for managers to make decisions and better control their strategies of reconfiguration. More specifically, managers should carefully recognize the possible negative effect of reconfiguration before seeking the benefits of its application.