Introduction

Protected areas have become the main instrument for addressing biodiversity loss (Chape et al. Reference Chape, Harrison, Spalding and Lysenko2005). Aichi Target 11 of the Convention on Biological Diversity, which includes a commitment to expand the global area coverage of terrestrial protected areas to 17% (CBD 2011), could drive the most rapid expansion of the global protected area network in history (Venter Reference Venter, Fuller, Segan, Carwardine, Brooks and Butchart2014). However, the establishment of these areas has socially impacted local populations, giving rise to conservation conflicts and compromising the effectiveness of these protected areas (Woodhouse et al. Reference Woodhouse, Bedelian, Dawson, Barnes, Schreckenberg, Mace and Poudyal2018). Conservation conflicts refer to the clashes of interests and opinions about conservation between two or more parties and when one of the parties feels impaired by the other, which is perceived to be asserting its interests at the expense of the other’s (Redpath et al. Reference Redpath, Young, Evely, Adams, Sutherland and Whitehouse2013). Central to such conflicts is that stakeholders have differing opinions about how to manage or use natural resources (Young et al. Reference Young, Marzano, White, McCracken, Redpath and Carss2010). Some stakeholders (e.g., protected area managers) foster biodiversity protection, while others (e.g., local populations) are keen to use natural resources, frequently for subsistence purposes (Dower Reference Dower, Redpath, Gutiérrez, Wood and Young2015).

When measures demarcating protected areas are imposed on the local population, there is often an enduring sense of loss and deprivation resulting from local people being displaced, excluded and/or restricted from the use of natural resources (de Pourcq et al. Reference de Pourcq, Thomas, Arts, Vranckx, León-Sicard and Van Damme2015). Even when protected areas implement diverse measures to compensate for the social impact (e.g., promoting local participation, payment for ecosystem services, ecotourism), the strategies frequently fail to help local people establish new livelihood strategies (Masterson et al. Reference Masterson, Spierenburg and Tengö2019) and, on the contrary, result in the persistence or even reinforcement of the local feeling of being negatively affected.

Having a shared understanding among parties is key for conflict management (Redpath et al. Reference Redpath, Young, Evely, Adams, Sutherland and Whitehouse2013, Young et al. Reference Young, Searle, Butler, Simmons, Watt and Jordan2016); it encompasses how different actors perceive both the conflict and the options for managing it and the level of agreement on these subjects among actors (Young et al. Reference Young, Searle, Butler, Simmons, Watt and Jordan2016). Similarly, parties must acknowledge that conflicts are a shared problem, and that the responsibility for seeking solutions must also be shared. The management of conservation conflicts aims to reconcile conservation goals with local livelihoods and to generate processes to promote understanding between parties (Redpath et al. Reference Redpath, Young, Evely, Adams, Sutherland and Whitehouse2013, Young et al. Reference Young, Searle, Butler, Simmons, Watt and Jordan2016). Among protected areas, biosphere reserves precisely aim at achieving conservation and local well-being, explicitly considering local interests (Halffter Reference Halffter2011). Perceptions of local inhabitants inside or near biosphere reserves therefore represent a key factor in conflict management (García-Frapolli et al. Reference García-Frapolli, Ramos-Fernández, Galicia and Serrano2009), as these perceptions provide fundamental input into analysing shared understanding.

To date, there has been only a limited exploration of the role played by shared understanding in conflict management within exclusionary or imposed protected areas. Some studies have explored related topics in varied environmental management scenarios, though not necessarily in conservation conflict contexts, nor within exclusionary biosphere reserves (e.g., Elias Reference Elias2008, Bathia et al. Reference Bhatia, Athreya, Grenyer and Macdonald2013, Ranger et al. Reference Ranger, Kenterb, Bryce, Cumming, Dapling, Lawes and Richardson2016). On the other hand, few studies have addressed related topics specifically in conflict management (e.g., Young et al. Reference Young, Searle, Butler, Simmons, Watt and Jordan2016, Lecuyer et al. Reference Lecuyer, White, Schmook and Calmé2018).

Imposed/exclusionary biosphere reserves depict a particular scenario for analysing the role played by shared understanding in conflict management, because biosphere reserves aim to involve local expectations in their definition and operation. Shared understanding is key to achieving a genuine inclusion of local interests and expectations (Redpath et al. Reference Redpath, Young, Evely, Adams, Sutherland and Whitehouse2013). When a biosphere reserve operates through imposition and local exclusion, there is no shared understanding, and feelings of impairments of local populations prevail.

The prevalence of feelings of impairment among local populations casts doubt on the role of shared understanding for conflict management. We hypothesized that this is because: (1) local impairment undermines trust and willingness to enter into dialogue (Young et al. Reference Young, Searle, Butler, Simmons, Watt and Jordan2016); and b) alternatives to repair the impacts of imposition and exclusion are often tied to competences beyond parties directly involved in a conflict, diminishing the relevance of shared understanding for solving conflicts.

The purpose of this paper is to better understand the role played by shared understanding in conservation conflict management. In particular, the goals of this study were: (1) to understand the main parties’ perspectives on the conflicts; (2) to determine whether there is a shared understanding on the conflicts; and (3) to analyse the role shared understanding plays in conflict management when protected areas are imposed or operate in an exclusionary way. For that purpose, we describe and disentangle the elements of two different conservation conflicts in the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve (CBR), an emblematic exclusionary-decreed reserve (Ericson Reference Ericson2006).

Materials and methods

Area and study communities

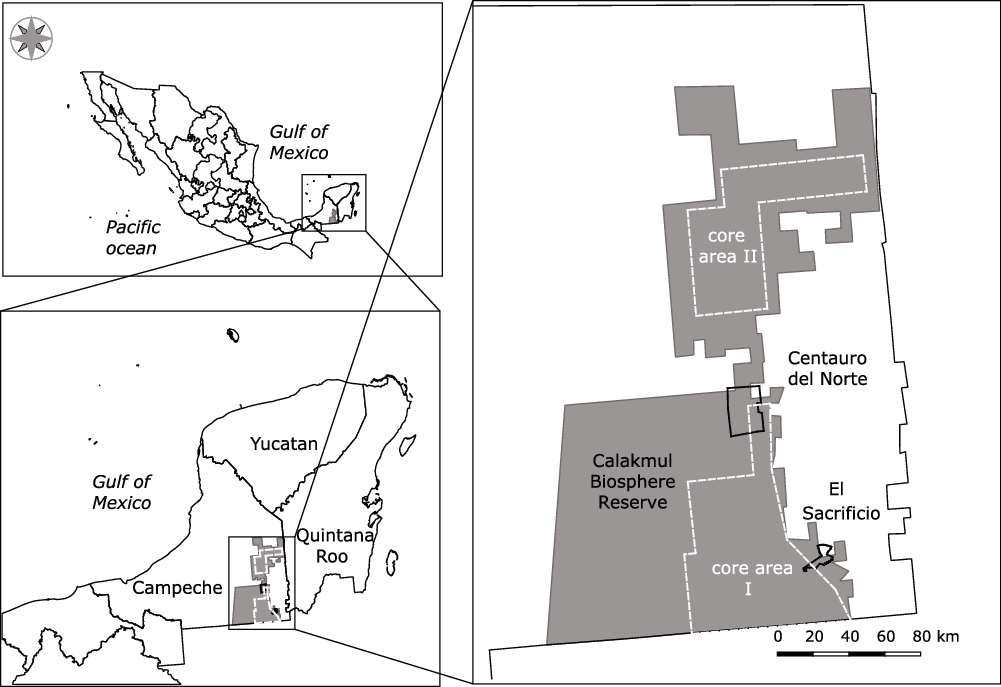

The CBR was decreed in 1989 through a non-participative process (Galindo-Leal Reference Galindo-Leal1999). Its 723 185 ha harbours the most important tropical forest relict in Mexico (CONANP 1999). From the start, it has also had a large human population, whose non-participation in the planning and decision-making processes has triggered several conflicts (Ruiz-Mallén et al. Reference Ruiz-Mallén, Corbera, Calvo-Boyero, Reyes-García and Brown2015a). The two communities where the study took place are Centauro del Norte (CN) and El Sacrificio (ELS), both located in the south of the CBR and both of which have a part of their territory within the Reserve (Fig. 1). These communities were selected because they are where two of the most salient conflicts in the CBR are located.

Fig. 1. Study area location in the Mexican state of Campeche. The Calakmul Biosphere Reserve (CBR) is denoted by the grey area. The conservation core areas I and II are denoted by white dashed lines. The communities of Centauro del Norte and El Sacrificio are denoted by black lines.

CN was established in 1987, 2 years before the Reserve was decreed, and has a communal land tenure regime, known in Mexico as an ejido, and a population of 236 people (INEGI 2010). The ejido spans 10 024 ha, of which 26% is within the Reserve’s core area. The other 74% is part of the buffer zone of the Reserve (INEGI 1996). Each ejidatario (landholder) has rights to a 100-ha plot. In 1992, the community won a juicio de amparo (lawsuit) that guarantees the protection of an individual’s constitutional rights against the Mexican Federal Government, upholding their prior rights to land as they had been living in the area 2 years before the Reserve was created in 1989 (Fig. 2). Winning the lawsuit meant that the community became exempt from the Reserve’s regulations, although their land is still within the Reserve.

Fig. 2. Timeline of the conservation conflicts in Centauro del Norte and El Sacrificio, Calakmul, Campeche. CBR = Calakmul Biosphere Reserve; ELS = El Sacrificio; SEDATU = Secretariat of Agrarian, Territorial and Urban Development.

ELS was created in 1999 through the relocation of four other communities that had originally been located in what became, with the creation of the CBR in 1989, the core area of the Reserve. ELS has a population of 540, mainly from Chol, Tzeltal and Tzotzil indigenous groups (INEGI 2010), whose land tenure regime is ‘small private property’. However, local people do not have official land deeds (Fig. 2), which has been a problematic issue since the establishment of the settlement. Despite being a relocation site, part of the community’s territory fell within the CBR. For this reason, property titles were never given out to families. The lack of documents supporting their legal land tenure has hindered the community’s participation in the development and conservation projects implemented by the government and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). As well as this legal uncertainty, the community is also restricted in its use of natural resources. Community land spans 2160 ha, of which 10% is within the Reserve’s core area and 90% is in its buffer zone (Periódico Oficial Reference Periódico2000, CONANP 2015). Family plots each comprise 20 ha.

Data collection and fieldwork

We conducted 33 semi-structured interviews in each community, 66 in total, with both landholders (6 women and 14 men in CN and 7 women and 13 men in ELS) and those without land rights (7 women and 13 men in CN and 6 women and 7 men in ELS), selected through simple random sampling from population lists provided by local authorities. Through these interviews, devised from similar studies (Lecuyer et al. Reference Lecuyer, White, Schmook and Calmé2018, Oliva et al. Reference Oliva, García-Frapolli, Porter-Bolland and Montiel2019) and the literature on conservation conflicts (Young et al. Reference Young, Marzano, White, McCracken, Redpath and Carss2010, Redpath et al. Reference Redpath, Young, Evely, Adams, Sutherland and Whitehouse2013, Reference Redpath, Gutiérrez, Wood, Sidaway, Young, Redpath, Gutiérrez, Wood and Young2015a), we collected data on: (1) the community context (e.g., local livelihoods, NGO operations and the history of the community’s relationship with the Reserve); (2) the impact of the Reserve and its regulations on local livelihoods; and (3) local perspectives regarding conflicts. We draw on these data to describe prevailing conflicts and to assess the extent of any shared understanding between the communities and the Reserve authorities. We also conducted semi-structured interviews with community authorities, mainly focused on the history of conflict management in the area.

To understand conflicts from the perspective of the CBR management, we carried out an in-depth interview with the director of the Reserve. This was aimed at understanding whether or not the Reserve recognized the conflicts perceived by the communities and how the manager viewed the roles that different actors played, as well as the causes of the conflicts and their management constraints. Another in-depth interview was held with the head of an NGO that has been partnering with the ELS community in different social and development processes. Additionally, we carried out two unstructured interviews with agrarian authorities (the Secretariat of Agrarian, Territorial and Urban Development (SEDATU) and the Agrarian Attorney (PA)) in order to document their position regarding the land tenure situation of each community.

Finally, we carried out participant observation throughout the fieldwork in order to support and verify the data obtained through interviews. Participant observation generated invaluable insights that helped us to understand the organizational context within the communities, as well as perceptions regarding other actors. Research was conducted over 3 years (2015–2017), and during this time, the first author resided in the study region, which also allowed in-depth participant observation of the different institutions involved (i.e., federal agencies, NGOs, local organizations and the CBR). Living in the study area also generated the opportunity for multiple unstructured interactions with CBR personnel, as well as with local stakeholders (NGOs, people from the communities), and promoted a wider understanding of the complex multi-institutional framework that characterizes the region.

Data analysis

Conflict mapping

Following Redpath et al. (Reference Redpath, Young, Evely, Adams, Sutherland and Whitehouse2013), we mapped the conflicts by: (1) identifying the stakeholders and their positions; (2) determining the sociopolitical context; (3) ascertaining evidence of conflicts; (4) identifying the social and ecological impacts of the conflicts; and (5) determining the willingness for dialogue between the parties.

Coding, patterns and statistical analysis

Interview responses were coded in order to identify key themes and patterns (Newing Reference Newing2011). A first set of codes was predefined in interview guides, and a second set emerged through the database elaboration. Codes were also used to carry out homogeneity tests in order to compare perspectives between communities. When conditions for performing a homogeneity test were not met (i.e., when >20% of the expected frequencies were <5), we used the test to determine the differences between two population cohorts instead. We used α = 0.05 for all analyses.

Shared perspectives

Shared understanding was determined by comparing six relevant topics for conservation conflict management: (1) definition of the conflict; (2) responsibilities for finding solutions; (3) main obstacles for conflict management; (4) type of interest in territory and natural resources; (5) need to conserve natural resources; and (6) alternatives for conflict management. These topics were derived from conservation conflict literature (Redpath et al. Reference Redpath, Young, Evely, Adams, Sutherland and Whitehouse2013, Reference Redpath, Gutiérrez, Wood, Sidaway, Young, Redpath, Gutiérrez, Wood and Young2015a, Reference Redpath, Gutiérrez, Wood, Young, Redpath, Gutiérrez, Wood and Young2015b, Mathevet et al. Reference Mathevet, Thompson, Folke and Chapin2016, Young et al. Reference Young, Searle, Butler, Simmons, Watt and Jordan2016) and from salient socioecological issues associated with the studied communities. Three possible outcomes for shared understanding were established: (1) ‘positive’ when perspectives were similar or compatible; (2) ‘negative’ when they were not; and (3) ‘intermediate’ when there was a certain level of overlap between parties’ perspectives, but not complete agreement.

Results

Describing the main parties’ perspectives on the conflicts enabled us to identify barriers and enablers to conflict management processes. By analysing the context of the conflict, we found that different actors’ functions played a significant role in locking or unlocking conflict resolution processes. Drawing on the case of ELS, we use a specific example to show how international conservation policy has had a detrimental effect on the management of the conflict. Finally, by contrasting different parties’ perspectives, we determined the extent of shared understanding and the role this plays in conflict management.

Conflict mapping

Following Redpath et al. (Reference Redpath, Young, Evely, Adams, Sutherland and Whitehouse2013), we defined categories for conflict mapping. In each community, we found that the conflict centred on the overlapping of community borders with the Reserve (Fig. 3) and the restrictions on natural resource use imposed by the Reserve management (Table 1). These restrictions (e.g., limited area allowed for subsistence agriculture of up to 3 ha, no hunting, no wood extraction) have resulted in permanent tension between CBR development and conservation objectives. Willingness for dialogue with the communities has been shaped by proposals for how to establish effective conflict management strategies. The Reserve’s position is to only approach communities once they have concrete measures in place for addressing the conflicts. We also found a general lack of ecological evidence of conflicts.

Fig. 3. Locations of Centauro del Norte and El Sacrifio and their surfaces overlapping with the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve.

Table 1. Conflict mapping in two communities within the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve (CBR).

Stakeholders’ perspectives

Local people

In general, we found that local residents had a negative perception of the CBR, especially in ELS, where interviewees said that the Reserve does not consider local interests or generate benefits, but, on the contrary, creates difficulties for them. When asked about their willingness to engage in dialogue, all of the interviewees answered in the affirmative (Table 2). This shows that the community is well disposed towards interacting with the Reserve authorities, even though there is a sense of resentment and a feeling that they should be compensated for their past forced relocation by government.

Table 2. Comparison of local perspectives in both study communities; ‘Yes’ means the community receives subsidies from the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve (CBR). Following each answer, we show the percentage of respondents that held that opinion.

*p < 0.05.

a ‘Yes’ here means that the community receives monetary subsidies from the CBR.

In CN, the absence of markets for local produce was acknowledged as one of the obstacles for developing productive activities. In contrast, in ELS, a lack of economic opportunities was identified. According to local residents in ELS, this was largely because of the poor quality of the soil and because most plots had been deforested. In addition, 27% of interviewees in ELS mentioned that the plot size (20 ha) was a factor that limited a family’s livelihood. In CN, plots were as large as 100 ha, and local residents considered them large enough to sustain subsistence activities and still leave a portion of the plot without productive or extractive use, where the forest could be preserved. In ELS, however, the plot sizes were not considered to be big enough to sustain both conservation and livelihood activities, but interviewees mentioned that both activities would be possible if the plots were larger. In both communities, interviewees said that conservation prevented the use of natural resources and that there should be compensation for the forest conservation they were carrying out if they did not use all of the natural resources on their plots.

A total of 25% of interviewees in CN said that they felt deceived by the Reserve. In both ELS and CN, a quarter of interviewees mentioned distrusting the CBR and third parties (such as the NGO that was working in ELS), and that there had been broken promises from the government, the Reserve and NGOs. An interviewee (24 years old) in ELS expressed: ‘People no longer trust [the reserve] … they have promised and broken their promises many times’. In general, there was a feeling of fatigue among community members regarding the government’s and other stakeholders’ interventions.

Both communities identified the restriction on the use of their natural resources as central to the conflict, as CBR only allowed them to use a small portion of their land for subsistence purposes. In CN, an interviewee (54 years old) said: ‘They [the Reserve] do prohibit a bit. But they don’t say “don’t do it” because, you have to do something for a living! But always what the Reserve says is respected. It says “this you can do”, up to there. You cannot cross the line. … Is the law’. Additionally, in the case of ELS, 33% of the interviewees mentioned that they could not get subsidies and implement development programmes due to the lack of land titles.

In CN, 27% of interviewees stated that they would be willing to collaborate with the Reserve if there was a good proposal. Additionally, c. 15% mentioned that the Reserve was not giving enough financial support to the community and that the government should help them to develop productive activities. In both CN and ELS, interviewees mentioned that there was a lack of clarity regarding the functions of different government agencies, including those responsible for conflict resolution.

CBR authority

The CBR officials interviewed recognized the deprivation that the establishment of the Reserve had caused for the local communities, as well as the problems caused by the lack of official land rights for ELS residents. Both issues were seen as sources of the conflicts between the Reserve and the communities. As an officer of CBR said: ‘As long as we don’t solve the conflicts that the reserve’s decree generated, even when there is willingness from both parties, there’s always going to be that [local] anger’.

In order to address the conflict with ELS, the director of the Reserve proposed redrawing the borders of the Reserve so that ELS would no longer be inside it. The main argument was that plots in ELS had already been deforested. The proposal was not accepted by the National Commission of Natural Protected Areas (CONANP) because, it was argued, Mexico needed to comply with the Aichi agreements, which means increasing and not decreasing the percentage of land under conservation. In this regard, the Reserve director stated, ‘In every country they think that … losing a single metre of PA is going backward in the [conservation] model’. The CBR’s administration acknowledges that local people play a critical role in conserving/depleting natural resources.

Regarding the obstacles for managing the conflicts, the Reserve director acknowledged four main issues: (1) the NGO, considered to be an illegitimate third party representing ELS, was impeding direct dialogue with the local people; (2) the conservation policy only allowed the area under protection to be increased; (3) there were institutional limitations for implementing management measures (e.g., land titles could only be granted by the agrarian authority SEDATU, which does not have jurisdiction in a federal protected area); and (4) there had been a lack of will from the state government and the local communities to manage the conflicts.

Other parties

Agrarian authorities (PA and SEDATU) did not assume any responsibility for land deeds in ELS because the land was located inside a federal protected area. Furthermore, the PA authority said that it would be highly detrimental for the Reserve’s public image if its area was reduced through dis-incorporating ELS.

According to the NGO that was working closely with ELS, when the community was relocated, an agreement was signed by the community and the state government. This established that: (1) the state government would give local people construction materials for building new houses; (2) people would be allowed to use the forest for subsistence purposes; and (3) the federal and state governments would pay for all the land titling expenses. According to the NGO’s representative and community members, this agreement was not upheld: construction materials were not delivered to families, and 24 out of 73 plots did not receive government payments for the land titling process.

Shared understanding

Through comparing the main stakeholders’ perspectives of the conflicts and considering the topics that were key for conflict management, we identified different levels of shared understanding (Table 3) and found that stakeholders had contrasting perceptions. Of a total of six issues identified, three did not have any shared understanding, and for two there was no clear agreement or disagreement among the parties involved.

Table 3. Shared understanding of relevant topics for conflict management in the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve (CBR).

SEDATU = Secretariat of Agrarian, Territorial and Urban Development.

Discussion

While shared understanding may not resolve a conflict, it does aid in conflict management and help to establish some level of tolerance among parties. Our research found partial shared understanding that did help the global process of conflict management and that its role was limited (1) by the persistence of local feelings of impairment resulting from the exclusionary creation and operation of the Reserve and (2) when conflict resolution demanded actions that exceeded key stakeholders’ functions. We discuss the factors that resulted in these outcomes.

Stakeholders’ perspectives on conflict management

In each case study, stakeholders’ perspectives of the conflicts were mainly about restrictions to local livelihoods because of the CBR. Impact on livelihoods has been identified as one of the main negative effects that protected areas have on local populations (Woodhouse et al. Reference Woodhouse, Homewood, Beauchamp, Clements, McCabe, Wilkie and Milner-Gulland2015), and this has previously been reported in Calakmul (Ericson Reference Ericson2006, Sosa-Montes et al. Reference Sosa-Montes, Durán-Ferman and Hernández-García2012). A lack of prior consultation with local communities over the establishment of the Reserve resulted in local people feeling aggrieved and resentful. This feeling did not seem to diminish over the years; on the contrary, time seems to have strengthened resentment and sapped local willingness to collaborate with the Reserve.

The lack of prior consultation, together with the forest conservation that communities currently practise on their land, led to a demand for compensation from the government. Such compensation, locals argued, is perceived as imperative. Indeed, costs of conservation are frequently borne locally through livelihood restrictions (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Teisl and Noblet2016). Even where there is official recognition that the establishment of the CBR was top-down and non-participatory, there is not necessarily the acknowledgement on the part of the CBR that its operations remain exclusionary and top-down (Ruiz-Mallén et al. Reference Ruiz-Mallén, Corbera, Calvo-Boyero, Reyes-García and Brown2015a).

There is no shared understanding regarding who is responsible for conflict resolution. On the one hand, the CBR and agrarian authorities argue that land deeds in the case of ELS are not their responsibility. On the other hand, local communities believe that the CBR is responsible for conflict resolution. However, political and bureaucratic obstacles have resulted in the CBR not having enough power to solve conflicts, as is the case in other protected areas (Karst & Nepal Reference Karst and Nepal2019, Oliva et al. Reference Oliva, García-Frapolli, Porter-Bolland and Montiel2019). It would seem that those same bureaucratic and financial obstacles facing protected areas in Mexico demand a more active involvement of local communities (García-Frapolli et al. Reference García-Frapolli, Ramos-Fernández, Galicia and Serrano2009, Bennett & Dearden Reference Bennett and Dearden2014). In this regard, a local understanding of these institutional operational limitations could help in the conflict management process.

Legal support has been used to manage conflicts (Baynham-Herd et al. Reference Baynham-Herd, Redpath, Bunnefeld, Molony and Keane2018). In the case of CN, despite having ‘legal protection’ (through winning the lawsuit), there is still conflict over the perceived restrictions to the community’s use of natural resources. This indicates that solving the legal aspect of a conflict does not necessarily mean that the conflict itself is resolved (Trouwborst Reference Trouwborst, Redpath, Gutiérrez, Wood and Young2015). We believe that, for ELS, a legal solution (i.e., obtaining land deeds) would be a step forward for conflict management and community well-being, as secure land tenure is a cornerstone for conservation (Pacheco & Benatti Reference Pacheco and Benatti2015). However, this would not necessarily mean an end to the conflict, given that the community might still face restrictions to their livelihoods.

The primary strategy that the CBR proposed for solving the land issue with ELS was to dis-incorporate that land from the Reserve, a strategy supported partly by the fact that the plots no longer had enough ecological value to justify their being part of a biosphere reserve. Re-evaluating the socioecological conditions of protected areas to determine their relevance is therefore of critical importance (Cumming Reference Cumming2016). The dis-incorporation proposal was roundly dismissed by CONANP because it goes against the federal conservation policy, aligned with Aichi Target 11, which aims to increase the size of protected areas nationwide. Our fieldwork found that wholesale subscription to such international conservation policies, without considering local contexts, hinders conflict management and has severe consequences for conservation in the long run. The quantitative criteria bias in applying Aichi Target 11 by prioritizing protection area goals (Visconti et al. Reference Visconti, Butchart, Brooks, Langhammer, Marnewick and Vergara2019) has been detrimental to community–reserve relations and, as is shown with the ELS case, could hamper conflict management.

Shared understanding and its role in conflict management

We found that even when there was a shared understanding at the individual level on some issues, the kind of topics that needed to be addressed for conflict resolution resulted in the need for actions that exceeded key stakeholders’ functions. Thus, we argue that shared understanding, although important for conflict management, might be secondary in aiding conflict resolution if the actions required are beyond stakeholders’ authority.

The only aspect in which we found shared interests was the acknowledgement of the need for conserving biodiversity: local populations were willing to maintain their environment and to support the Reserve’s aims to preserve biodiversity. This highlights how the conflict is not about different interests regarding conservation as a general idea (Holland Reference Holland, Redpath, Gutiérrez, Wood and Young2015), but rather about how to meet livelihood needs without depleting ecosystems. We highlight the importance of these shared views as starting points to develop conflict management processes (Lecuyer et al. Reference Lecuyer, White, Schmook and Calmé2018).

However, it is also necessary to address other aspects than those on which agreement exists. Focusing on topics over which there is no shared understanding might be a cornerstone in the conflict management process, given that a lack of shared understanding is one of the main factors hindering it. Identifying disagreements between parties is essential because this reveals sensitive aspects that require special treatment (Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, White and Fischer2007).

One of the main aspects that we found needed a shared understanding was the actual mandates and limitations of the parties involved in the conflict. For instance, the lack of clarity regarding the Reserve’s mandate hindered local residents’ understanding of the Reserve administration’s position and the options it suggested for conflict management. Consequently, local people were not willing to negotiate, as they blamed the Reserve for not solving the conflict, assuming that the Reserve had the power and capacity to do so. We suggest that being aware of the constraints other parties face might improve stakeholders’ tolerance in conflict management processes.

Shared understanding has been described as the level of agreement among stakeholders regarding what a conflict is about and how to manage it (Young et al. Reference Young, Searle, Butler, Simmons, Watt and Jordan2016). From our findings, we propose that it might be useful to conceive of shared understanding not only as agreement on particular issues, as previously defined (Redpath et al. Reference Redpath, Young, Evely, Adams, Sutherland and Whitehouse2013, Lecuyer et al. Reference Lecuyer, White, Schmook and Calmé2018), but also as knowing the reasons underlying the position of the other party, concentrating on understanding what the other party is able and not able to do.

Conclusions

While shared understanding is essential for conflict management, we found that it might not be the main strategy to address conflicts when (1) the actions required to solve a conflict exceed the mandates of key stakeholders and (2) local impairment due to exclusion from protected areas persists. Our study has contributed to the conservation conflict literature by identifying key general topics in which a shared understanding is useful for conflict management in protected areas.

We have also contributed by evaluating the limitations that shared understanding has for conflict management. In this regard, we suggest that shared understanding is both difficult to attain and insufficient by itself for solving conflicts when dealing with protected areas that have been imposed and/or operate through an exclusionary process. While we encourage efforts to seek shared understanding among parties in conflict, we also highlight the importance of addressing key factors that hinder conflict management, especially when such constraints are beyond stakeholders’ capacities and call for actions at levels they cannot reach.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the people from the study communities who participated and who shared valuable information for this study. We are also grateful to Professor Stephen Redpath for advising the first author during a research stay at the University of Aberdeen and to CONACYT for funding her through a mobility grant. We acknowledge the suggestions and relevant observations made by the anonymous reviewers and the editor. Mary-Ann Hall translated the manuscript into English and Sarah Bologna carried out the final English editing of the manuscript.

Financial support

The first author extends acknowledgment to the PhD programme in Sustainability Sciences, UNAM ‘Doctorado en Ciencias de la Sostenibilidad, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México’, and a PhD scholarship received from CONACYT, Mexico. This research was funded by UNAM–PAPIIT, grant number IN302517.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

None.