Residents of Bapu Nagar, a slum in the Indian city of Jaipur, Rajasthan, had long struggled to secure electricity connections from the state government. During the summer of 2017, after being repeatedly dismissed by electricity department officials, residents approached Banwari, an informal leader in Bapu Nagar, for assistance with petitioning the department for connections. Banwari’s efforts proved successful. One resident remarked, “The wires have been laid and the meters are about to be installed. We went to Banwari and don’t know if he met someone or called someone, but our work was done.” Footnote 1 And yet, despite this success, residents of Bapu Nagar hold pessimistic views about their ability to gain attention from public officials, absent assistance from a political broker like Banwari. As one resident put it, “[Public officials] don’t listen. We don’t even get to see their faces.” Footnote 2

Travel seven hours south to Rajasthan’s rural district of Udaipur and patterns of citizen-state engagement look quite different. There, rural citizens also seek services from the state, but do so most often by turning directly to local public officials. A Scheduled Caste woman residing in a remote village, for example, recounted how she and her neighbors mobilized in the face of water shortages: “Now, there is a government tank … We made it by telling the panchayat [elected local council] time and time again.” She went on to explain that “we made the panchayat … We said, we gave you our votes, now bring us water!” Footnote 3

These accounts highlight two divergent patterns that are reflected in the broader data upon which we draw. First, similarly poor rural and urban residents in this region of India hold different expectations of state responsiveness, which are diminished in the urban setting compared to the rural. Second, these varied expectations are manifest in different approaches to the state, which are more likely to be mediated by political brokers in urban slums compared to villages. Our study rests on a comparison of data drawn from two surveys—one conducted across 105 villages in Rajasthan and one conducted across 80 slums in the cities of Jaipur and Bhopal (capitals, respectively, of Rajasthan and neighboring Madhya Pradesh)—as well as qualitative fieldwork in the same settings. Through this joint analysis, we observe that the urban poor are almost four times less likely to believe they will get a response if they directly contact a public official, compared to their rural counterparts. Slum residents, moreover, are over two times more likely to report that political brokers are active in their community. We find that these differences cannot be adequately explained by socioeconomic factors such as relative material wellbeing or education; by ascriptive characteristics such as caste or gender; or by land tenure, migration, or proximity to administrative centers.

Our findings from northern India invert widely held conceptions of political engagement in the urban core versus the rural periphery. From Karl Marx to classical modernization theorists, scholars have predicted that city dwellers would participate more in politics and demand more from their representatives than those in more remote rural settings (Marx Reference Marx1852; Lerner Reference Lerner1958; Lipset Reference Lipset1959). More recently, scholars have argued that cities are the sites of greater state capacity and resources that both raise citizens’ expectations and make it easier for them to make claims, compared to more distant and under-resourced rural settings that are portrayed as fertile ground for rent-seeking middlemen (Krishna and Schober Reference Krishna and Schober2014; Brinkerhoff et al. Reference Brinkerhoff, Wetterberg and Wibbels2018; Berenschot Reference Berenschot2018). Our study suggests a more complex picture, revealing higher levels of despondency, and a greater prevalence of intermediation, in urban slums compared to similarly poor rural settings.

Reflecting on these patterns, we have two related aims. First, we seek in the northern Indian context to illuminate the institutional features that set the stage for such divergent patterns of citizen-state engagement. Building inductively from our fieldwork, we highlight three such features: the relative visibility and accessibility of public welfare services in villages compared to urban slums; the relative depth of rural compared to urban decentralization; and the vigor of party organizations—and hence glut of politically connected brokers—in cities compared to villages. Together, these relative strengths and weaknesses of local government and of party organization push and pull poor rural and urban residents toward different strategies, reflecting uneven expectations of and pathways to the state. Our article’s second and broader aim, extending beyond our research sites, is to develop an analytical framework for the study of local citizenship practice. We do so by highlighting the power of place-based analysis that considers the institutional differences in local governance that set the stage for divergent patterns of citizen-state engagement.

In the following section we highlight a gap in the study of how the poor encounter and make claims on the state in India and beyond—and propose an analytical framework for exploring how and why these experiences vary sub-nationally. We then introduce our research settings in northern India and the data on which we draw. Next we describe the puzzling variation in citizens’ expectations, marked by higher pessimism regarding government responsiveness in urban slums compared to rural villages. This expectations gap is coupled, as we then show, with a more pronounced presence and use of political brokers in slums. The next section examines a range of characteristics—from poverty, education, caste, and gender, to landownership, migration, and distance to a town—that might drive variation in citizens’ beliefs and practices. We then explore the institutional roots of that same divergence—underscoring the importance of the varied local terrain of the state. We conclude by exploring the potential for both virtuous and vicious feedback loops between government performance and citizenship practice, and the implications—in India and beyond—for the study of democratization and distributive politics.

Rethinking the Rural-Urban Divide

The political economy literature is replete with examples of urban bias, highlighting pro-urban policies and a decline in the quality of services with distance from the city (Bates Reference Bates1981; Brinkerhoff et al. Reference Brinkerhoff, Wetterberg and Wibbels2018). In India, where democratization preceded industrialization, the rural sector has retained considerable electoral and policy influence. And yet both public and private capital are concentrated in urban India, revealing a persistent gap in human development between India’s cities and villages. Given this gap, scholarship on distributive politics in India suggests that rural citizens expect less in terms of public service delivery than urban residents (Krishna and Schober Reference Krishna and Schober2014). Urban residents are generally also thought to have greater capabilities to express political voice, in part because of exposure to information and ideas in densely populated, heterogeneous settings (Lerner Reference Lerner1958; Evans Reference Evans2018). In electoral terms, India is a noted exception, since rural voters turn out at rates as high or higher than urban elites. However, beyond the voting booth, India’s villagers have long been described as “docile,” “passive,” and “politically accepting.” Footnote 4

Studies also predict higher levels of political mediation in rural settings compared to cities, driven in part by greater distances to state agencies and by poorer local administration. Cities, in contrast, are home to greater numbers of government agencies, and have more developed transportation and communication networks relative to the countryside. It follows that accessing the local state should, in theory, be easier for urbanites (Krishna and Schober Reference Krishna and Schober2014). Rural villages, in contrast, are home to precisely the concentration of poor residents, typically lacking a middle class, which many predict should be most susceptible to clientelism. Footnote 5 Rural India is often described in precisely these terms: to the extent that rural residents engage the state, they are expected to do so by leaning on political intermediaries (Manor Reference Manor2000; Krishna Reference Krishna2002; Corbridge et al. Reference Corbridge, Williams, Srivastava and Véron2005; Krishna and Schober Reference Krishna and Schober2014).

Our findings from northern India complicate these priors by shifting the frame of reference to examine the political behavior of the poor in both urban and rural settings. There is little comparative work to date that examines the political behavior of the poor across the rural-urban divide; most analyses instead compare broad urban aggregates to the rural. However, urban slums are—like villages—sites of large concentrations of poverty and of social and political exclusion (Chatterjee Reference Chatterjee2004; Auerbach Reference Auerbach2016, Reference Auerbach2020). It is thus critical to ask which residents are the beneficiaries of the resources and shortened pathways to government that are presumed of cities. Indeed, the slum residents in our study, we will show, often have more in common with rural villagers than with the urban middle and upper classes.

What might explain these gaps in expectations and citizenship practice between similarly poor rural and urban residents? Reflecting on our study sites, we argue that sub-national variation in the institutional terrain of the state (Kruks-Wisner Reference Kruks-Wisner2018a; Bertorelli et al. Reference Bertorelli, Heller, Swaminathan and Varshney2014)—that is, in the performance, visibility, and accessibility of public resources and personnel—generates unevenness in citizens’ expectations of and approaches to public officials. Citizens’ engagement of the state is iteratively influenced by what they observe and come to believe about the governance institutions in their localities.

In building this theory, our research offers two contributions to the broader study of citizen-state relations. First, we present a framework for examining how citizens’ local experiences of state institutions influence sub-national patterns of participation. This framework, we suggest, is particularly powerful in non-programmatic settings, where the gap between de jure policy and de facto implementation and distribution looms large. Studies of welfare provision in advanced industrial settings have long documented policy feedback loops, wherein new policies, once enacted, reshape citizens’ interests, galvanizing new constituencies (Campbell Reference Campbell2003; Mettler and Soss Reference Mettler and Soss2004; Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2019). In less programmatic and less developed settings with more “truncated” welfare systems, studies find the opposite kind of feedback, as the poor “receive less, expect less, and demand less from the welfare state” (Holland Reference Holland2018, 2). To date, however, the scholarship on feedback loops has largely focused at the macro scale, examining how national policies mobilize “mass” politics, without often considering how citizens’ encounters of the state might vary sub-nationally. Footnote 6

Second, we highlight three interconnected factors in India that inform and mediate the gap between national and state policies on the one hand and citizens’ local experiences of policy implementation on the other: the breadth of social spending, the depth of decentralization; and the strength of political party organization. In so doing, we emphasize the varied channels that influence citizens’ encounters of and approaches to the state. Studies of distributive politics very often model the poor’s access to the state as mediated and conditional on political support (Stokes et al. Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Brusco2013), while a separate but resonant literature emphasizes the poor’s exclusion from formal state institutions, and hence their dependence on systems of political patronage (Chatterjee Reference Chatterjee2004; Harriss Reference Harriss2005). However, these class-framed analyses of “differently placed” citizens (Corbridge et al. Reference Corbridge, Williams, Srivastava and Véron2005, 15) shed little light on variation among similarly poor citizens. Our study, accordingly, investigates the sub-national geography of citizenship practice among the poor—highlighting unevenness in patterns of political intermediation.

Context and Methods

We draw on data from Rajasthan (population 68 million) and neighboring Madhya Pradesh (MP) (73 million), both of which fall in the bottom quarter of Indian states ranked by human development standing (UNDP 2011). Between 2009 and 2011, Kruks-Wisner carried out over eighteen months of fieldwork in rural Rajasthan, including a survey administered to 2,210 households in 105 villages. Footnote 7 This was accompanied by roughly 500 interviews with residents and officials, including extended fieldwork in six case study villages. Between 2010 and 2012, Auerbach conducted twenty months of fieldwork in slums in Jaipur (capital of Rajasthan) and Bhopal (capital of MP), including fifteen months of fieldwork in eight case study settlements and a survey of 1,925 residents across eighty settlements.

Our surveys, while conducted independently, both sought to capture citizens’ expectations concerning state responsiveness and their strategies of claim-making. Both surveys, moreover, were built upon sustained fieldwork that enabled the careful construction of survey instruments appropriate to their particular contexts (Tsai Reference Tsai, Carlson, Gallagher, Lieberthal and Manion2010; Thachil Reference Thachil2018). Footnote 8 This enables us to engage in contextualized comparative analysis of citizens’ beliefs and strategies as they unfold in particular settings (Locke and Thelen Reference Locke and Thelen1995)—a necessary practice when fielding surveys in distinct social environments. Our joint analysis further benefits from the ability to hold constant key regional variables as well as the timing of our fieldwork, which was carried out under the same state and central government administrations.

Our two surveys thus provide an important opportunity to compare citizenship practice in this region of India. We acknowledge, however, the tradeoffs that exist between our approach—centered on contextually embedded surveys—and the design of a cohesive single survey which, if uniformly administered across all settings, might avoid potential discrepancies in design that could limit the precision of comparison. As such, we are careful in what follows to highlight the specificities of our two survey instruments.

The remainder of this section lays out the bases for our comparisons, arguing, first, that rural villages and urban slums are marked by similar levels of deprivation across a number of dimensions and, second, that slums and villages—despite differences in geography and demography—operate within similar formal governance structures.

Urban Slums and Rural Villages: Apples and Oranges?

Is it fair to compare citizen expectations in urban slums, which are among the poorest and least well served in a city, to those in rural villages? We argue that the comparison is valid, since slums and villages are home to similarly marginalized populations (table 1). Just over one-quarter of both our rural and urban respondents possessed a “Below Poverty Line” (BPL) card. Analysis of asset ownership reveals similarly low average rural and urban scores of just over 2 and 3 respectively on a seven-point index. Of the sampled slum residents, 40% were illiterate, with a sample-wide average of five years of formal education. The rural sample averaged 4.3 years of education, with 46% reporting that they had no formal schooling.

Table 1 Socioeconomic standing in urban slums and rural villages

* Asset index includes ownership of motorcycle, car, TV, radio, refrigerator, gas stove, and mobile phone.

These aggregate statistics, though, mask substantial variation in the experience of poverty within both samples. Thus, to ensure that we are comparing similarly marginalized groups, we disaggregate our findings in the analysis that follows, comparing the “asset poor” (those in the lowest quintile) across both samples. We also compare those without any formal education, as well as those with so-called “lower” caste standing. The slum sample includes over 300 distinct sub-castes (jati), representing all strata of the Hindu caste hierarchy and a range of Muslim castes (zat); 36% are Scheduled Castes (SC) and 7% are Scheduled Tribes (ST). Footnote 9 Hindus constitute 75% of the urban respondents, while 23% are Muslim. The rural sample is 98% Hindu but represents a diversity of jati including 19% each from the SCs and STs. We also consider gender, disaggregating our findings for women and men, and explore the intersection of sex and other markers of social standing across and within the two samples.

It is within this comparative framework—examining rural and urban residents with similar indicators of socioeconomic standing—that we ask three interlinked sets of questions. The first two are empirical questions, for which we draw directly on our survey data and qualitative research. First, how responsive do citizens believe officials to be? Second, how do citizens with different sets of expectations make claims on the state? Third, why do citizens’ experiences of the state—reflected in their beliefs and claim-making practices—differ? We approach this last question from a theory-building perspective, triangulating between our survey data, fieldwork observations, and reading of the broader literature on rural and urban governance in India to highlight an interconnected set of factors that play a powerful role in shaping citizens’ expectations of and approaches to the state.

Local Governance in India’s Cities and Villages

A concern in asking these questions might arise if formal systems of local governance are so different in cities and villages that the targets of claim-making are simply distinct. This, though, is not the case. In both rural and urban contexts, decentralization reforms in the early 1990s created similarly structured elected local governments—rural panchayats and urban municipal councils—that are mandated to hold elections every five years and feature electoral reservations for women, SCs, and STs. In addition to these elected local representatives, both settings are also home to a constellation of appointed officials who work in various government departments that oversee public service provision—for example, Public Health and Engineering Department officials, sanitary inspectors, Electricity Department officials, District Collectors, and block/zonal officials. The formal structure of both elected and appointed local governance is thus similar across rural and urban India.

Could it be, though, that rural and urban slum residents are simply seeking different things from the state, thus driving them to interact with different agencies? Far from it, we find that the conception of the state—as a target of claim-making—articulated by citizens is broadly similar. Both rural villagers and urban slum residents petition the state for “selective” goods (e.g., rations, pensions, and other subsidies) as well as “collective” goods in the form of local infrastructure (e.g., roads, water sources). We also observe high rates of state-targeted claim-making in both settings. Footnote 10 A full 76% of rural survey respondents reported having personally engaged in efforts to claim public services from local officials. Footnote 11 This included majorities among the asset-poor, and among SCs and STs, as well as women. Footnote 12 Residents of the eighty sampled slums in Jaipur and Bhopal also routinely made claims on the state––80% of those surveyed reported that people in their settlement had come together to voice problems to government officials related to local development, Footnote 13 while 52% reported that they themselves had been involved in such efforts within the last twelve months. This activity persisted across those with and without land titles, Footnote 14 as well as across respondents from different economic and social backgrounds. Footnote 15 Similarly, 48% of urban female respondents reported having been involved in acts of claim-making within the last twelve months. Yet despite these broad commonalities in levels of claim-making, in underlying needs, and in formal governance structures, citizens’ beliefs about state responsiveness varied dramatically across slums and villages.

Uneven Expectations

Rural and urban residents expressed very different opinions about their ability to command state responsiveness when directly approaching public officials. Respondents in both surveys were asked whether they thought they would be ignored or get a response if they themselves contacted or approached a government official. Footnote 16 In both of our questions, the nature of an “official” was cast broadly, referring to both elected representatives and unelected bureaucrats, in order to inquire about the widest possible range of state actors. Our data suggest an expectations gap from slums to villages in this corner of north India.

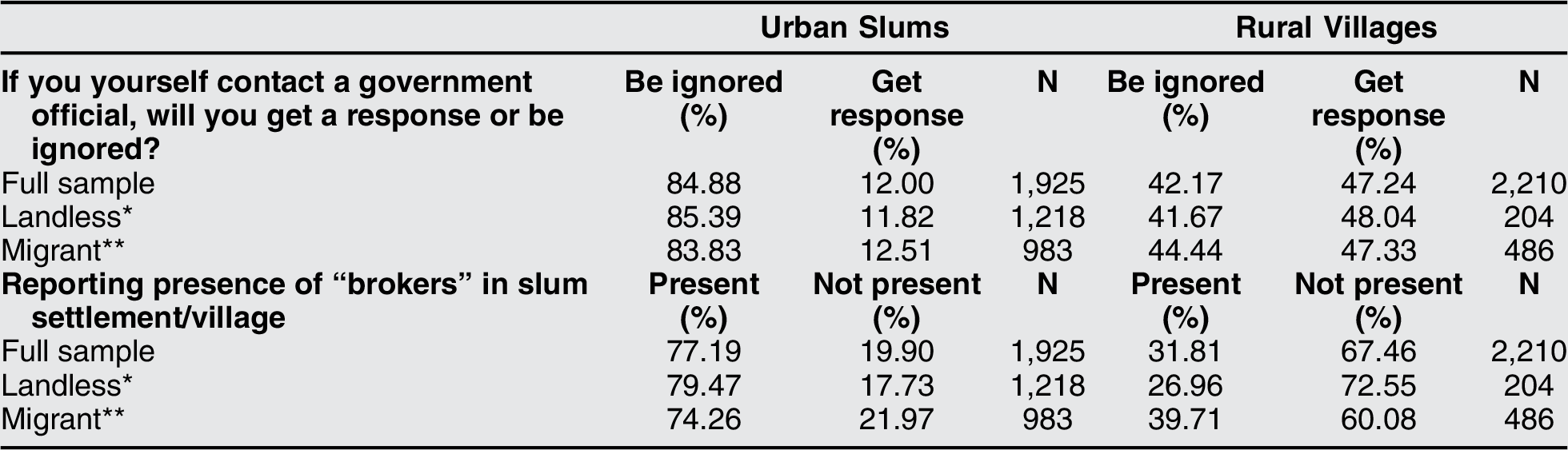

An overwhelming majority (85%) of those surveyed in Jaipur and Bhopal said they expected to be ignored, while only 12% believed they would get a response upon contacting an official (table 2). Footnote 17

Remarks from slum residents in Jaipur illustrate this bleak outlook:

Nobody listens to us … they say, where have these people come from? And they shoo us away. Footnote 18

They don’t listen to us because we live in a slum. They don’t respect us; they look down on us. Footnote 19

Hopes of responsiveness remained consistently low in the sampled slums, regardless of socioeconomic standing. The most marginalized (those with the least assets, and those without any formal education, as well as members of the SCs, STs, and Muslims) hardly differed from the sample mean. Footnote 20 Women expressed even greater pessimism, with just 10.26% believing they would command the attention of officials. This reveals a small but statistically significant gender gap, compared to 13.50% of men who expected attention (p < 0.05). We also find remarkably low expectations when examining the intersection of sex and markers of socioeconomic status. Footnote 21

Forty-two percent of those surveyed in rural Rajasthan thought they would be ignored if they directly contacted an official, while 47% expected that they would get a response—a rate of optimism that is almost four times higher than in the urban slums. Footnote 22 Rural expectations did decline among the poorest (those in the lowest quintile of asset ownership), the least educated, and the lower castes and tribes. Footnote 23 There is also a large and significant gender gap within the rural sample; just over 35% of female respondents expected a response, compared to just over 55% of men (p = 0.000). Footnote 24 But even these most marginalized rural residents remained less likely to think they would be ignored compared to similarly disadvantaged slum residents. As table 2 shows, substantially larger numbers among the rural asset poor, the rural SC and ST, as well as those with no formal schooling, expected a response compared to their counterparts in slums. Similarly, rural women are 3.5 times more likely to expect a response than female slum residents.

Table 2 Expectations of government responsiveness

Note: Where totals do not add to 100%, additional respondents reported “don’t know” or data is missing.

* Asset poor = first quintile of asset ownership, on 7-point index

The implications of these stated expectations are subject to interpretation. On one hand, the fact that more than two-fifths of rural respondents expected to be ignored by officials could be seen as a democratic deficiency. Statements by some village residents certainly support this view. An SC man in an Udaipur village, for example, complained: “Why waste your breath? Sarkar [the state] does nothing for us. They come at elections, they eat the votes, then they go away again and we are forgotten.” Footnote 25 On the other hand, the fact that almost half of all rural residents believed they would get a response is also striking—particularly when compared to the much smaller number who declared the same in slums. In sum, while it is important not to oversell rural citizens’ optimism, it is clear that there is a different set of beliefs about the state at play between our rural and urban study settings, extending across similarly disadvantaged groups.

The Local Presence and Use of Political Intermediaries

Rural and urban citizens’ expectations of the state are not simply expressed through their reported beliefs, but are also revealed through differences in how residents engage the state. Slum residents and villagers report the presence of political brokers at strikingly different rates. In both surveys, brokers are understood as informal, non-state actors who assist citizens in accessing public officials but who do not themselves have any formal jurisdiction over public distribution. Footnote 26 Direct practices, in contrast, are those that involve personal engagement with public officials—including both elected representatives and appointed bureaucrats. While the lines between direct and mediated practices can at times be blurry (local officials, for example, can play gatekeeper roles to higher-level officials Footnote 27 ), we maintain that there is an important substantive distinction between contacting state and non-state actors. It matters for citizenship practice whether one turns to informal brokers or engages with officials who have codified mandates in representation and service provision. As Bertorelli et al. (2014, 9) put it, the difference is in engaging the state as “a bearer of rights, and not as a supplicant, client or subject.”

Our surveys probed this distinction, asking about the local presence and use of informal brokers in claim-making. Differences in context required that questions be phrased differently in order to operationalize the concept of a broker in locally meaningful terms. Footnote 28 In the urban survey, respondents were asked whether they or someone in their household had contacted “slum leaders” (kachi basti neta), who were described as

people who do leadership activities (netagiri). I’m not talking about the area ward councilor or member of the legislative assembly. I’m talking about small community leaders that live inside the slum. These leaders go by several names, like slum leader, slum president, don, slum headman, or a party worker in the settlement. They are socially prominent people in the settlement.

These slum leaders are otherwise ordinary residents who climb into a position of authority by demonstrating local problem-solving abilities (Auerbach Reference Auerbach2017; Auerbach and Thachil Reference Auerbach and Thachil2018). They frequently do so by leading groups of residents to the offices of officials, and by submitting petitions demanding public services. Frequently, they are grassroots members of party organizations (karyakarta). Slum leaders thus occupy influential leadership roles within their settlements, yet their status is not derived from winning formal elections or occupying a position in government.

In the rural setting, where a diverse array of different types of informal leader can be found, the survey asked whether respondents had contacted “problem-solving” leaders, who were defined as

people in a village who are well connected, meaning they know how to get things done both inside and outside the village. These people can help others with their problems, helping them to make contact with government agencies and to access government schemes and benefits.

The survey further specified that these are actors “who have influence in the village and are able to get work done, but who do not hold any elected or official position in village government.”

Our data suggest a key difference in the prevalence of local political brokers and, by extension, a divergence in the rates at which rural and urban respondents turn to intermediaries. A large majority (77%) of our urban respondents reported that brokers (“slum leaders”) were active in their settlements. Footnote 29 These slum leaders, however, may be variably visible and accessible to different groups. Table 3 therefore reports the rates at which various types of residents note the presence of slum leaders. Rates are consistently high, and do not vary significantly from the sample mean, across groups set apart by asset ownership, caste, religion, and gender. Footnote 30 These same patterns are reflected in the rates at which respondents replied that they or someone in their household had visited an informal leader to seek assistance—as reported by 35% of all slum respondents. Strikingly, this rate of contacting brokers is nearly uniform across different types of respondents, including the asset poor, the uneducated, and SC, ST, and Muslim respondents, as well as women. Footnote 31

Table 3 Reported presence of informal political brokers

Note: Where totals do not add to 100%, additional respondents reported “don’t know” or data is missing.

* Asset poor = first quintile of asset ownership, on 7-point index.

In contrast to the slums where brokers pervade the local landscape, just 32% of rural respondents reported that brokers (“problem-solving” leaders) were active in their villages. Footnote 32 This rate was even lower, around one quarter, for those rural respondents with the fewest assets and the least education. Footnote 33 The same is true for women, who were 33% less likely than men to report being aware of brokers (p = 0.000). It follows that relatively small numbers (18% of the full rural sample) reported personally contacting these problem-solvers for assistance. Footnote 34 This ranged from just 11–14% among the asset poor and those with no formal education, Footnote 35 to 16% of SC respondents, 20% of STs, and just 9% of Muslims—although these differences are not statistically significant. There is, however, a significant gender gap: rural women are (at 10%) 55.5% less likely than rural men (at 22%) to reporting seeking help from brokers (p = 0.000). Footnote 36

Why Might Citizenship Practice Diverge from Town to Country?

Why do slum residents believe they are more likely to be ignored by public officials, and why are they more likely to acknowledge local brokers, than villagers? This section examines extant scholarship on political behavior to consider a range of socioeconomic and demographic factors that might influence citizens’ attitudes toward and engagement with the state. While illuminating in many respects, we find—reflecting on our study sites—that this literature cannot adequately account for the variation we observe.

Scholars have long suggested that poverty inhibits active citizenship practice, predicting that the poor will have fewer opportunities and lesser capacity for the effective exercise of voice (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995; Appadurai Reference Appadurai, Rao and Walton2004). Could, then, the divergences we observe point to the intensity of urban, as opposed to rural, poverty? We argue that this is not the case since indicators of deprivation are similar across the two samples. Moreover, restricting ourselves to poor-poor comparisons (as presented in tables 2 and 3), we observe higher expectations among the rural sample, as well as higher rates of reporting brokers among the urban sample.

A related body of work examines the role of education, suggesting that higher levels of attainment enable greater levels of political participation since more educated citizens ought to have greater ability to navigate the political system (Wolfinger and Rosenstone Reference Wolfinger and Rosenstone1980; MacLean Reference MacLean2011). And yet our data reveal an inconsistent effect of education. In both the rural and urban settings, there is indeed a gap in expectations between those with the highest (tertiary-level) schooling and those with lower levels. Footnote 37 However, examining those with zero formal education across both samples, the expectation gap continues to loom large: uneducated urban residents are more than three times less likely to expect a response from officials than uneducated rural residents. In both samples, moreover, the most educated were no less likely to contact brokers.

Ascriptive characteristics related to ethnicity are also unable to adequately explain the observed variation. As noted earlier, both the slums and villages are home to substantial numbers from marginalized groups such as the SCs, STs, and (in the urban settings) Muslims. However, none of these groups differ substantially from their sample averages in either expectations of officials or approach to brokers. Moreover, SC and ST slum residents were three and four times less likely, respectively, to expect responses from officials (table 2), and were roughly two-and-a-half times more likely to report the presence of brokers than SC and ST villagers (table 3). Footnote 38

Gender is another often-cited dimension in studies of citizen-state relations (Rai and Lievesely Reference Rai and Lievesley2013; Behl Reference Behl2019). While early studies observed higher levels of political activity among men compared to women, this global gap has begun to close in recent decades (Norris Reference Norris2002). In India, though, women continue to fall behind men across an array of political activities—although the gap is narrowing in the electoral arena (Vaishnav Reference Vaishnav2015). It is thus not surprising to observe that both rural and urban women are less likely than men to expect responses from public officials. And yet we have also observed that broad rural-urban divergences persist controlling for gender: rural women have notably higher expectations of government responsiveness than women in urban slums.

We must, then, look beyond socioeconomic and ascriptive attributes at other structural factors that might shape citizen-state relations. The rural and urban samples diverge notably along two such dimensions that are important markers of informality and of residential stability: formal landownership and rates of migration. A striking 71% of respondents in the sampled slums either had no form of legal land title (despite owning their home’s physical structure) or were renters, compared to just 9% of rural respondents who did not formally own any land. Similarly, more than half of the slum sample reported having migrated to the city, while almost all in the rural sample had lived their adult life in the village. However, almost one-quarter of rural respondents reported migration of a more short-term and circular nature, stating that they or a member of their household lived outside the village for more than thirty days per year.

Table 4 examines our two central variables of interest (expectations of government responsiveness and the reported presence of brokers) along the dimensions of landownership and migration. Informality pervades slums in the areas of housing, employment, and associated documentation (Heller et al. Reference Heller, Mukhopadhyay, Banda and Sheikh2015), and these differences in formal status and recognition doubtless do influence residents’ relationship to the state. And yet certain visible markers of formality, such as formal landownership, do remarkably little to demarcate citizens’ expectations of public officials. A comparison of those without land in both samples leaves the rural-urban gap undiminished: the rural landless are four times more likely to expect officials to respond to their direct claims compared to those without land titles in slums. Landless villagers are also markedly less likely to report brokers than slum residents without land titles. Footnote 39 Thus, while informality is certainly an important factor, it cannot, in and of itself, account for the variation we observe. Footnote 40

Table 4 Informality and residential stability

Note: Where totals do not add to 100%, additional respondents reported “don’t know” or data is missing.

* Landless = in urban sample, those with no formal land title (excludes renters); in rural sample, those with no formal landownership.

** Migrant = in urban sample, those born outside of Jaipur and Bhopal districts; in rural sample, those where household member lived outside village for thirty days or more/year.

Migration, like informality, also might influence an individual’s relationship to the state. Dramatic flows of rural-urban migration within India are well documented and, indeed, a majority of our urban respondents were born outside of either Bhopal or Jaipur district. Footnote 41 It follows that these migrants might, as relative newcomers, expect less from officials, or that they might be more likely to seek out brokers because of unfamiliarity with the local environment. Alternatively, if migrants—because of having been willing to move—are by nature less risk adverse, they might also be more politically assertive, and therefore more likely to engage in direct claim-making. We find, however, remarkable uniformity in the responses of migrants and non-migrants within the slum sample (table 4). While migrants are less likely to acknowledge slum leaders than non-migrants (p < 0.05), the former are not significantly less likely than the latter to report that they or someone in their home have turned to those brokers for help. The difference in means in the rates at which migrants and non-migrants in our slum sample expect responses from officials is also statistically insignificant. The rural-urban differences we observe are therefore not simply driven by the subset of our urban respondents who were born outside of Jaipur and Bhopal. Footnote 42

An additional factor with the potential to influence citizens’ stances towards the state might be physical distance to an administrative center (Krishna and Schober Reference Krishna and Schober2014). In the rural setting, this refers to towns with block and district seats where public agencies and personnel are concentrated. We find, however, no significant change in expectations or in rates of brokerage among rural respondents living at different distances to towns. Footnote 43 This has much to do with the nature of rural decentralization, which, as we discuss later, has brought administration closer to the village. Urban slums are located in closer physical proximity to government offices, and yet slum residents express diminished expectations compared to rural residents.

To summarize, our data cast up a set of puzzles: citizens’ expectations of and approaches to public officials diverge across the rural-urban divide in ways that complicate much of the conventional wisdom about patterns of participation and citizen-state engagement. The remainder of our article reflects on these puzzles, drawing on our field experiences (cumulatively thirty-eight months) and our reading of scholarship on local governance in rural and urban India. Our aims are twofold: first, to inductively build an argument about the conditions in northern India that might provoke such divergent patterns of citizenship practice, and second to consider the generalizable implications for the broader study of citizen-state relations.

The Terrain of the State in Northern India

Our central argument is that citizens’ engagement of the state is influenced by their encounters with governance institutions in their particular locality, and the expectations and strategies that those encounters engender. In this section, we develop this claim regarding our study settings in northern India, identifying a set of institutional features—the distribution of social spending, the depth of decentralization, and the strength of party organization—that differ sharply across the rural-urban divide, and which, we argue, drive variation in local citizenship practice. More research is required to test these propositions, as well as to probe their generalizability—charges to which we return in the concluding section.

Unevenness in Social Spending

Recently, India’s villages have been the beneficiaries of an influx of social spending, expanding through the 2000s. Footnote 44 This influx was driven in part by a wave of welfare legislation including the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), the Right to Education Act, and the National Food Security Act. While not exclusively focused on the rural sector, many components of these acts—and all of MGNREGA—are targeted to India’s villages, as are other programs such as the National Rural Health Mission, the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (a rural roads program), and Indira Awas Yojana (a rural housing program), to name a few.

Social spending also increased in urban India in the same time period, although the relative gains have been more muted. Indeed, as Bhan, Goswami, and Revi (Reference Bhan, Goswami and Revi2014, 83) observed, “programs of social security in India—ranging from enabling and rights-based entitlements to basic transfers seeking to prevent destitution—have been and remain focused on rural poverty and vulnerability, with budget allocations that reflect such priorities.” In addition, urban social spending is highly differentiated between regularized neighborhoods and slums. A national survey found, for example, that—despite their concentrations of poverty—only 24% of slums in India had benefitted from urban development programs such as Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission or Rajiv Awas Yojana (an urban housing program). Footnote 45 Similarly, a study of an urban employment program in Rajasthan found that only 0.02% of slum residents in the sampled cities (including Jaipur) had been exposed to the program (Tewari Reference Tewari2002). In comparison, MGNREGA is the largest rural employment program of its kind in the world, with a budget that accounts for roughly 0.5% of total GDP, reaching more than one-quarter of rural households (Sukhtankar Reference Sukhtankar2016). A full two-thirds of our rural sample reported having a household member who worked under MGNREGA.

The rural poor, then, have begun to encounter the state in public programs and through local service provision in ways that have remained comparatively underdeveloped in slums. As a result, the local state is becoming more visible in rural citizens’ lives compared to slum residents’. Footnote 46 These relative improvements in rural service delivery, coupled with persistent failure to deliver in slums, have played a key role in shaping residents’ perception of and engagement with the state.

Unevenness in Decentralization

At the same time that new patterns of social spending worked to expand the presence of the state in rural settings, the state also pushed deeper into the local arena through decentralization. In 1992, the seventy-third and seventy-fourth amendments to the Indian constitution mandated the creation of local elected bodies in both villages and cities, establishing Gram Panchayats and municipal councils, respectively, in each setting. The formal parameters of decentralization are similar; in both, panchayat members and ward councilors are directly elected every five years. Both sets of elected local bodies, moreover, co-exist with a wide array of appointed bureaucrats active at the state and local levels. However, significant differences have emerged over the past two-and-a-half decades in the depth of decentralization. The rural Gram Panchayat (GP) has emerged as a key node for public welfare distribution and, consequently, as a central site for citizen-state engagement. Municipal councils, in contrast, have remained relatively moribund, starved for resources and stretched thin in their capacity and personnel.

There are currently close to 10,000 GPs in Rajasthan, each with average population of about 5,000. Each panchayat has between five to twenty elected members (including a president and ward members), all directly elected every five years. Seats are reserved for women (at 50%), and for members of the SCs, STs, and “Other Backward Classes” in proportion to their local share of population. Panchayats have also experienced an increased flow of public resources, stemming from the influx of social spending noted earlier. This infusion of funds and expansion of responsibilities has “combined to enliven local politics considerably. For the first time in most states, almost all local groups (including the poor) see that local panchayat decisions can make a material difference in their lives” (Jenkins and Manor Reference Jenkins and Manor2017, 63).

The cumulative effect of these changes is an increase in the visibility and relevance of panchayats. Early on, the GPs were referred to as “paper tiger” institutions (Mathew Reference Mathew1994, 36), and were widely perceived as lacking local autonomy. Indeed, a study of rural Rajasthan in the late 1990s, carried out just a few years after the first round of panchayat elections, revealed that very few citizens even considered the GP as a potential source of assistance; when asked who they expected to help in accessing public services, no more than 18% of survey respondents referenced the GP (Krishna Reference Krishna2011, 110). In our data, collected almost fifteen years later, a full 62% reported having personally contacted GP officials for assistance when seeking goods and services. Footnote 47 This dramatic shift speaks to the changing landscape of local governance, where citizens access the GP with increasing frequency. Footnote 48

India’s urban municipalities are divided into wards, with the voting population in each ward directly electing a councilor every five years. Jaipur, a city of three million people, currently has ninety-one wards; Bhopal, with two million people, currently has eighty-five. Councilors across these wards collectively make up the municipal council. As in the rural setting, municipal elections also feature reservation of seats for SCs, STs, and Other Backward Classes in proportion to their population share, as well as reservations for women in at least a third of seats. And yet despite these formal similarities, the relative weakness of India’s municipal councils, compared to the panchayats, is manifest in a variety of ways.

Most strikingly, the urban wards in our study cities are much larger in terms of population than GP constituencies. In Jaipur and Bhopal, the average ward populations during the study period were, respectively, 39,557 and 25,689 people—a constituency size that is eight and five times larger than that of the average rural GP in our sample. A ward councilor thus has substantially more constituents vying for his or her attention. The result is that urban local governments remain less accessible for most urban residents compared to villagers, despite the shorter physical distances that urban residents need to travel to reach their elected representatives. Reflecting on similar dynamics, Ramanathan (Reference Ramanathan2007, 674) remarks that “the base of the pyramid is expanding only for rural local government … caught in the penumbra of the spotlight on their rural brethren, urban dwellers are finding themselves in a governance vacuum.”

In comparison to rural GPs, then, local elected bodies in India’s cities are less accessible to their constituents. These shortcomings are most pronounced in poor neighborhoods, and in slums in particular. Footnote 49 Indeed, Banda et al. (Reference Banda, Bhaik, Jha, Mandelkern and Sheikh2014, 12) go so far as to describe slum residents as “a population that does not approach the state as citizens with rights”, but rather as “supplicants in a woefully unbalanced bargaining equation.” The same deficiencies in local governance produces a larger demand in slum settlements for political intermediaries with the skills and connections to assist residents in gaining access to public resources. Chatterjee describes this as a process of “paralegal” brokerage and “bending and stretching of rules” by local leaders and politicians who mediate access to the state (Chatterjee Reference Chatterjee2004, 73). This demand for intermediaries is met by a large supply of brokers who navigate the dense partisan networks that flourish in India’s slums.

Uneven Strength of Party Organizations

Studies of Indian politics have long described party organizations as weak and fleeting in their local presence, particularly in the countryside (Kohli Reference Kohli1990; Manor Reference Manor2010). This description resonates with what we find in our rural sample, in which respondents reported that they are not very likely to encounter, let alone make claims on, higher-level politicians (above the GP). Seventy-seven percent of those surveyed, for example, reported that “politicians or party members” visited their village just once in the last year (which, at the time of the survey, was an election year). This, in large part, reflects the physical distance of party organizations, which are typically located in towns and cities. It follows that relatively small numbers—just 22% of the rural sample—reported turning to politicians or to rank-and-file party workers for claim-making purposes. To be clear, these patterns should not be interpreted as an absence of partisan ties in the rural settings. It is well established that GP members maintain strong ties to parties, despite their nominally non-partisan status. The key difference that we underscore, then, is not in levels of partisanship, but rather in level of party organization—manifest in local party workers who are scarce in villages but abound in urban settings.

Our data from slums in Bhopal and Jaipur render a picture of active and structured party organizations. At the time of the survey, 513 position-holding party workers (padadhikari) lived and operated within the eighty sampled settlements in Jaipur and Bhopal. Importantly, these party workers are unelected, and do not hold any formal position in the bureaucracy. They are archetypal informal brokers, mobilizing residents for parties and mediating access to the state for residents. The Indian National Congress and Bharatiya Janata Party, the two parties that dominate electoral politics in MP and Rajasthan, are organized and staffed in a similar pyramidal fashion in Bhopal and Jaipur, from the grassroots “booth” led by a president and a small team of workers, to ward, block, city, and district level committees. Both parties also organize organize morcha (wings) and prakosht (cells) to mobilize various interest groups, including the kachi basti prakosht (slum cell). The structured nature of party organizations in these cities, and the pervasiveness of street-level party workers in slums, increase the opportunities for the urban poor to turn to party workers when seeking access to the state. These partisan channels are made all the more appealing given slum residents’ low stated expectations of responsiveness should they directly approach an official.

In sum, residents of slums seek to improve their wellbeing in a context where formal local governance institutions (elected municipal councils) are less directly accessible (due to large constituencies), and less powerful (due to the anemic capacity and diminished resources of municipalities relative to their large populations). At the same time, organized political parties offer a means of accessing the state through grassroots workers who serve as informal brokers. In our rural setting, quite the opposite conditions prevail; more deeply institutionalized local governance bodies (the elected panchayats), serving notably smaller constituencies, offer spaces for direct citizen-state engagement over an expanding pool of public resources. Political parties, in contrast, remain weakly organized on the ground, with only sporadic visits by politicians and thinly spread party workers. Footnote 50 These conspicuous sub-national institutional differences, we argue, play an important role in driving rural-urban variation in citizens’ expectations of the state, and are reflected in the varying degrees to which our two samples acknowledge and engage political intermediaries.

Conclusion: A Place-Based Analysis of Citizen-State Relations

Our study has revealed geographically variegated citizenship practice among rural and urban residents in our northern Indian study sites. Urban slum residents, we have demonstrated, are substantially less likely than similarly poor rural villagers to believe they will get attention if they directly approach either an elected or an appointed government official. These low expectations among the urban poor are coupled with a high prevalence of informal brokers, who fill the void in settings marked by what are perceived to be largely unresponsive local governments. These patterns, we have argued, reflect three interconnected factors: uneven distribution of social spending, uneven depth of decentralization, and uneven strength of party organization. The combined result, we have proposed, is a relative thickening of the state in rural areas, compared to urban slums. Footnote 51

And yet cities are typically seen as possessing higher levels of state capacity, easier and more direct access to state offices and personnel, as well as higher concentrations of public resources. This is true to an extent of India, where private capital and public resources, as well as most public offices, are concentrated in urban centers (Krishna and Bajpai Reference Krishna and Bajpai2011; Krishna and Schober Reference Krishna and Schober2014). But India’s urban bias in public policy and spending is less pronounced than in many other countries, in part reflecting the agrarian nature of its early democracy (Varshney Reference Varshney1998). Our findings sit alongside a growing body of work emerging from India that challenge—and in some cases invert—long-held theoretical priors that link urbanization and democratization (Krishna Reference Krishna2008). Looming urban inequality, moreover, means that capital and resources are unevenly spread within India’s cities. We thus look beyond the rural-urban divide at the particular institutional features that influence the felt local presence and visibility of the state, and so which give shape to different forms of citizenship practice in different sub-national contexts.

We conclude by examining the implications of our findings, and of the broader theoretical framework they suggest, for the study of citizen-state relations in India and beyond. The slums in our study reveal an acute deficit in public accountability, where almost 85% of respondents think public officials will simply ignore them. This, we have suggested, reflects the relatively thin presence of the state in these settings, which depresses citizens’ hope of being able to directly make demands on officials, and so necessitates a larger role for brokers—the supply of which is guaranteed by dense and structured party organizations. Important questions arise in the Indian context about the long-term political consequences of these brokered partisan channels. How will they influence citizens’ sense of political efficacy, their perceptions of government accountability and, ultimately, their continued engagement in the political system? Our rural study settings are also marked by low expectations, but are, compared to slums, sites of relative political optimism on the part of citizens. Whether or not this can be sustained depends on how well the state is able to respond to growing levels of citizen demand. If citizens’ expectations outpace local government capacity, a different equilibrium—marked by exit—may take hold. A virtuous cycle of improved public performance and rising citizen expectations is thus a fragile one and may shift with changes in social spending and bureaucratic capacity.

Further research is required to probe the depth and reach of our findings. Future studies, building from our findings, might investigate whether the patterns we observe are robust to alternative forms of survey design—including a joint design that spans both settings. Additional research is also needed to investigate the generalizability of our findings to other settings elsewhere in India. However, we broadly predict a similar inversion of urban bias—reflected in the expression of higher expectations of government responsiveness by the rural as opposed to urban poor—where the following conditions prevail: first, where substantial public funds are channeled through rural local bodies and, second, where slums remain underserved relative to the broader cities in which they are embedded. These conditions ring true across most of India, where rural decentralization is more deeply rooted than urban, and where rural social spending outpaces urban—especially when diluted by population size. We might, though, also expect sub-national variation across states with different histories of decentralization as well as varied levels of party competition (Bohlken Reference Bohlken2016) or with different parastatal institutions and arrangements for service delivery (Post, Bronsoler, and Salman Reference Post, Bronsoler and Salman2017), in addition to local variation in the capacity and responsiveness of public institutions within states (Kapur and Mehta Reference Kapur and Mehta2007)—all avenues for future research.

Beyond India, different patterns are likely to emerge in settings with different histories of state formation, many of which are marked by more pronounced urban biases. Our aim is not to suggest that the same forms of rural-urban divergence that we observe across our study sites should obtain in all places or under all conditions. Rather, our goal is to demonstrate how citizens’ local engagement of the state is influenced by their expectations of governance institutions in their localities. Our analytical framework—which calls for an examination of the local institutional terrain of the state—is generalizable, while the particular patterns of citizenship practice should be place-specific.

More comparative research is thus needed to examine both sub-national and cross-national differences in patterns of citizen-state engagement. Studies from across the Global South have demonstrated that persistently low expectations can lead to political withdrawal and demobilization (MacLean Reference MacLean2011; Holland Reference Holland2018). On the other hand, relative improvements in local government performance—and, critically, the visibility of these improvements—can provoke higher expectations and, in turn, increase the likelihood of citizen mobilization (Kruks-Wisner Reference Kruks-Wisner2018b; Evans Reference Evans2018). There is, thus, the potential for both vicious and virtuous cycles, driven by the dynamic processes through which citizens’ expectations of government responsiveness are built and revised. Investigating the nature of these feedback loops and the conditions under which they vary—leading to despondency in some settings but to demand-making in others—is among the most important lines of inquiry for scholars of democracy and of distributive politics. A focus on the geography of citizenship practice—on place-based patterns of citizen-state relations—offers a crucial path for future inquiry.

Supplementary Materials

S.1 Survey Design

S.2. Comparative Survey Questions

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592720000043