Introduction

The order Trigoniida arose in the late Silurian, maintaining a low diversity until the Permian when it experienced a radiation (Newell and Boyd, Reference Newell and Boyd1975). It was highly successful during Mesozoic times, when it was the most conspicuous and diverse group of shallow-burrowing bivalves (Stanley, Reference Stanley1977). It was considered a highly resilient taxon (Ros and Echevarría, Reference Ros Franch and Echevarría2011) that swiftly recovered after being strongly affected by the end-Permian and end-Triassic mass extinctions. On the other hand, after the end-Cretaceous extinction event, trigoniids were confined to epicontinental seas of Australia and New Guinea, where they are nowadays represented by a single genus (Darragh, Reference Darragh1986).

During most of the Early Jurassic the Trigoniida seems to have been largely restricted to the Pacific coast of the Americas and to Japan (Ziegler, Reference Ziegler1971; Aberhan, Reference Aberhan, Crame and Owen2002, appendices 1, 2; Francis and Hallam, Reference Francis and Hallam2003; Ros Franch et al., Reference Ros Franch, Márquez Aliaga and Damborenea2014, fig. 41; Echevarría and Ros Franch, Reference Echevarría and Ros Franch2019); although some authors mentioned the presence of lower Early Jurassic trigoniids elsewhere (e.g., Deecke, Reference Deecke1925; Hallam, Reference Hallam1977, appendix, p. 72). By the late Early Jurassic–early Middle Jurassic they experienced a wide dispersion, reaching the European Tethys (Francis, Reference Francis2000; Francis and Hallam, Reference Francis and Hallam2003) and South East Asian Tethys (Wandel, Reference Wandel1936; Hayami, Reference Hayami1972) by the Toarcian, the high latitudes of Antarctica by the Pliensbachian–Toarcian (Kelly, Reference Kelly1995), New Zealand by the Aalenian (Fleming, Reference Fleming1987), and eastern Africa by the Bajocian (Cox, Reference Cox1965). After the Triassic/Jurassic extinction event, the Trigoniida are well recorded and relatively abundant in South American Early Jurassic deposits (Leanza, Reference Leanza1942; Pérez and Reyes, Reference Pérez and Reyes1977; Ishikawa et al., Reference Ishikawa, Maeda, Kawabe and Rangel Zavala1983; Leanza, Reference Leanza1993; Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008). The present paper deals with this particularly interesting place and time-span for the study of Trigoniida systematics and evolution, and documents the rapid radiation of the group.

The systematics of the group has been variably treated, but a stable taxonomic framework has remained elusive. The genus Trigonia was first described by Bruguière (Reference Bruguière1789) and characterized mostly by its particular hinge; soon, several species were recognized within it and the genus was subdivided into sections (Agassiz, Reference Agassiz1840; Lycett, Reference Lycett1872–1879), which were the base for the recognition of many new genera (Bayle, Reference Bayle1878; van Hoepen, Reference van Hoepen1929; Crickmay, Reference Crickmay1930; Dietrich, Reference Dietrich1933). Cox (Reference Cox1952, see also Cox et al., Reference Cox, Newell, Boyd, Branson, Casey, Chavan and Coogan1969) differentiated the family Trigoniidae from the family Myophoriidae on the basis of hinge characters, particularly the broad and prominent median tooth of the left valve with transverse ridges on both occluding surfaces in the former. Later authors (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1954; Saveliev, Reference Saveliev1958; Poulton, Reference Poulton1979; Leanza, Reference Leanza1993; Francis, Reference Francis2000) maintained that scheme of a single family, subdividing it into several subfamilies. Although Newell and Boyd (Reference Newell and Boyd1975) suggested a polyphyletic origin for trigoniid hinge characters, few authors followed their scheme. Boyd and Newell (Reference Boyd and Newell1997) themselves returned to the distinction between Myophoriidae and Trigoniidae.

Cooper (Reference Cooper1991) considered that, given the high variability within the Trigoniida, the systematic scheme was inadequate. He proposed two suborders within the order Trigoniida: Trigoniina and Myophorellina. The first one included the superfamilies Myophoriacea (equivalent to Myophoriidae sensu Cox, Reference Cox1952) and Trigoniacea. The second one included the superfamilies Myophorellacea and Megatrigoniacea. Many of the subfamilies were raised in rank to families.

Because the Early Jurassic stock is the basis for the main Mesozoic radiation of the group, the detailed study of the faunas here presented is fundamental in order to understand the evolution (and, as a consequence, the systematics) of the order. To infer evolutionary relationships among the studied species we employed a stratophenetic approach (Gingerich, Reference Gingerich, Cracraft and Eldredge1979) whenever possible, based mostly on a qualitative assessment of characters. We tried to maintain a phylogenetic criterion on supraspecific taxa, avoiding polyphyletic groups. In contrast, since ancestor-descendant relationships were inferred in some cases, paraphyly could not be avoided.

The systematics of Early Jurassic Trigoniida still needs to be supported by a phylogenetic analysis of the Triassic representatives (work in progress, but out of the scope of this contribution). The systematic arrangement followed here is thus tentative, and is based on Bieler et al. (Reference Bieler, Carter and Coan2010) and Carter et al. (Reference Carter, Altaba, Anderson, Araujo, Biakov, Bogan and Campbell2011), with some modifications. We accept the superfamily Trigonioidea in the sense of Bieler et al. (Reference Bieler, Carter and Coan2010) and Carter et al. (Reference Carter, Altaba, Anderson, Araujo, Biakov, Bogan and Campbell2011), including, among others, the families Groeberellidae, Trigoniidae, and Prosogyrotrigoniidae, and the family Myophoriidae as the ancestral stock for the others. The superfamily Myophorelloidea includes, in this report, the families Frenguelliellidae and Myophorellidae. We regard Frenguelliellidae as ancestral to Myophorellidae. Since we were not able to thoroughly analyze the later diversification of the suprageneric taxa here included, we refrained from providing proper diagnoses for them. The subfamily category sometimes has been used in excess in this group, resulting in lots of monogeneric subfamilies. Therefore, we prefer to avoid the use of subfamilies until further systematic revision is carried out.

The oldest paleontological papers describing Early Jurassic marine macrofossils from Argentina contain records of Trigoniida (Behrendsen, Reference Behrendsen1891; Burckhardt, Reference Burckhardt1902; Jaworski, Reference Jaworski1915), even though a few of the earliest described species were erroneously assigned stratigraphically to the Early Cretaceous (Jaworski, Reference Jaworski1915) or the Late Triassic (Groeber, Reference Groeber1924). Further descriptions were included in papers dealing with diverse invertebrate faunas (Weaver, Reference Weaver1931; Feruglio, Reference Feruglio1934; Carral-Tolosa, Reference Carral-Tolosa1942; Leanza, Reference Leanza1942), and later in papers specifically concerning the Trigoniida (Lambert, Reference Lambert1944; Levy, Reference Levy1966, Reference Levy1967; Leanza and Garate-Zubillaga, Reference Leanza, Garate-Zubillaga and Volkheimer1987; Leanza et al., Reference Leanza, Pérez and Reyes1987; Leanza, Reference Leanza1993). Early Jurassic Trigoniida from Chile were recently revised by Pérez et al. (Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008).

We present here a comprehensive systematic analysis based on collections gathered during decades, by detailed sampling of a geographically extensive area across the entire Early Jurassic stratigraphy. Specimens from old collections made in Argentina are scattered in several European repositories; these specimens were examined whenever possible. The large amount of material available enabled us to pay particular attention to morphologic variability within many of the taxa described, an aspect somewhat neglected in the past, although its importance has been highlighted by some authors (e.g., Francis, Reference Francis2000; Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Fürsich and Werner2011).

Geological setting

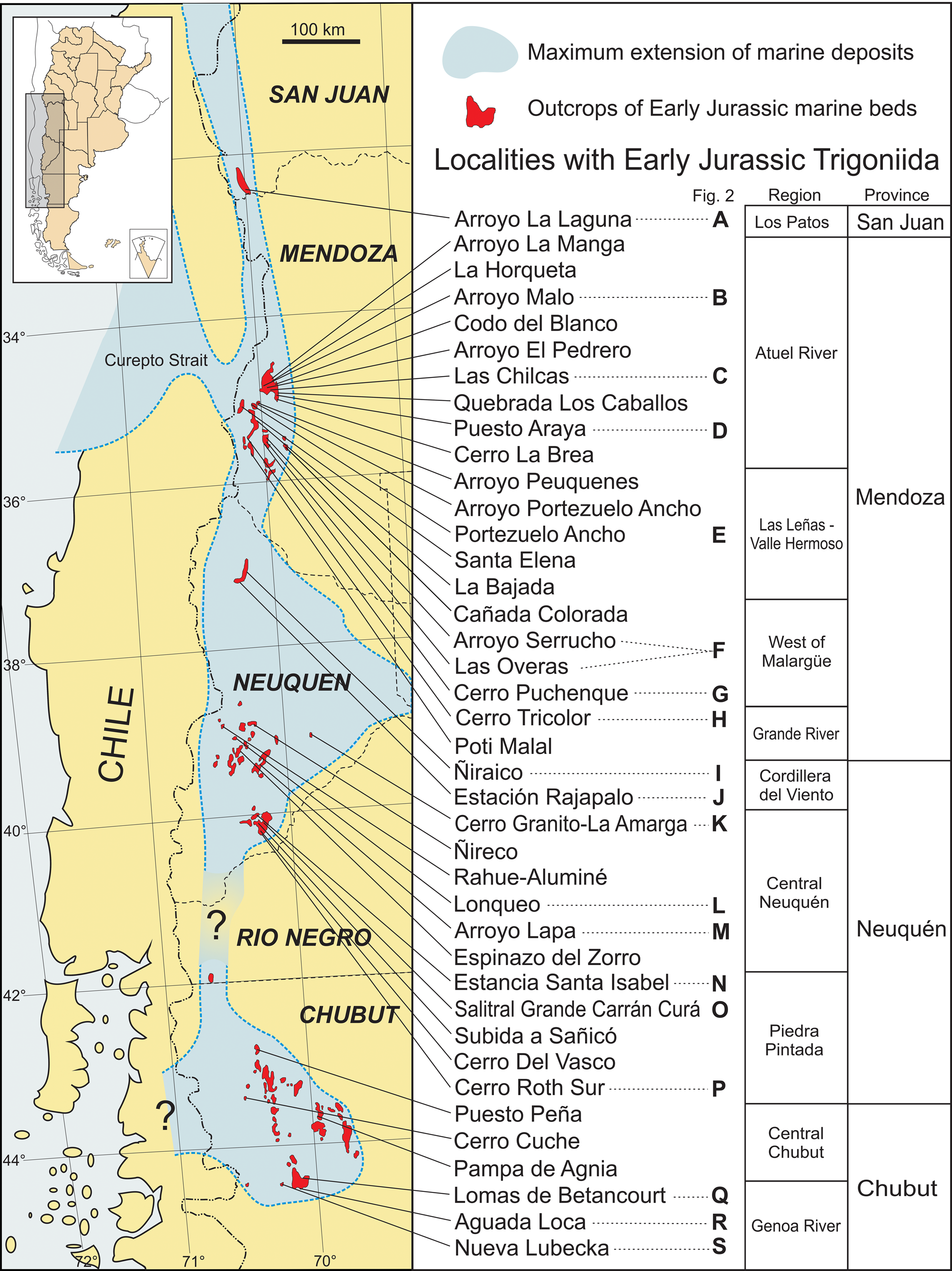

Marine Lower Jurassic beds in Argentina were widely deposited in the west-center of the country from southern San Juan to Chubut provinces (Fig. 1). Two main basins, probably interconnected, developed (i.e., Neuquén and Chubut). They both contain widespread deposits exhibiting a variety of paleoenvironments. The Aconcagua-Neuquén depocenter (Riccardi, Reference Riccardi, Moullade and Nairn1983) developed during the Late Triassic–Eocene (Howell et al., Reference Howell, Schwarz, Spalletti, Veiga, Veiga, Spalletti, Howell and Schwarz2005; Lanés, Reference Lanés2005) between 30° and 41°S latitude, with an eastward expansion towards the southeast (the Neuquén Embayment) that can be regarded as an epeiric sea. The onset of this basin is related to a rifting phase from the Middle Triassic to the Sinemurian (Ramos, Reference Ramos1992; Manceda and Figueroa, Reference Manceda, Figueroa, Tankard, Suárez Soruco and Welsink1995) that led to the evolution of a series of narrow and isolated depocenters (Uliana and Biddle, Reference Uliana and Biddle1988; Legarreta and Uliana, Reference Legarreta and Uliana1996). Marine sediments of this first stage crop out only in the Atuel River region (southern Mendoza) (Riccardi et al., Reference Riccardi, Damborenea, Manceñido and Ballent1988), close to the so-called Curepto Strait, which was one of the main connections of the basin with the Paleopacific (Vicente, Reference Vicente2005). After that, a sag stage developed from late early Sinemurian to Toarcian, causing the coalescence of the initial depocenters during the late Sinemurian–Pliensbachian, and thus enlargement of the area under marine influence (Legarreta and Gulisano, Reference Legarreta, Gulisano, Chebli and Spalletti1989; Legarreta and Uliana, Reference Legarreta and Uliana1996). From this time on, the Neuquén Basin developed as a back-arc basin related to circum-Pacific convergence (Legarreta and Uliana, Reference Legarreta and Uliana1996), with pyroclastic and volcanic content especially common in Lower Jurassic deposits. During the early Pliensbachian the basin expanded southward, reaching its maximum extension in the late Pliensbachian. Although the basin was partially barred from the open ocean, the well-diversified faunas indicate that free oceanic connections occurred through gaps in the arc (Legarreta and Uliana, Reference Legarreta and Uliana1996). By Middle Jurassic times, proximal deltaic and alluvial facies started to prograde, reducing the depositional area (Legarreta and Uliana, Reference Legarreta, Uliana and Caminos1999, p. 405).

Figure 1. Map of the localities mentioned in the text, in the context of general Pliensbachian–Toarcian paleobiogeography, compiled from various sources, mainly Legarreta and Uliana (Reference Legarreta and Uliana1996), and Vicente (Reference Vicente2005). Localities are grouped by region and province as used in the text. Stratigraphical sections depicted in Figure 2 are indicated by capital letters.

The Chubut Basin is a NNW-SSE elongated depocenter (Fig. 1) with marine and continental sedimentary deposits of Early Jurassic age, mainly exposed in the western region of Chubut Province and extending northwards into Río Negro Province (41°00’–46°30′S) (Suárez and Márquez, Reference Suárez and Márquez2007). The sedimentary succession of the Chubut Basin accumulated under an extensional tectonic regime (Lizuain, Reference Lizuain and Caminos1999; Uliana and Legarreta, Reference Uliana, Legarreta and Caminos1999), starting with continental deposits overlain by shallow-marine and continental successions. To the east, these marine beds interfinger with mainly pyroclastic continental facies (Franchi et al., Reference Franchi, Panza, De Barrio, Chebli and Spalletti1989). Early Jurassic marine sediments lie unconformably over late Paleozoic rocks, but contrary to Carral-Tolosa's (Reference Carral-Tolosa1942, p. 22, 67) assumption of a complete Early Jurassic marine sequence in Chubut, most marine beds seem to have been deposited during the short interval from the late Pliensbachian to the early Toarcian (Riccardi Reference Riccardi2008a, Reference Riccardib).

Thus, by late Pliensbachian times, there was an elongate marine encroachment with two expanded basins (Neuquén and Chubut) that were connected with the Pacific Ocean (Legarreta and Uliana, Reference Legarreta and Uliana1996). Their sedimentary successions maintained local variations in thickness and lithology due to an uneven basin floor related to active rifting and a variety of depositional environments (Legarreta and Uliana, Reference Legarreta, Uliana and Caminos1999). The basinal successions are punctuated by turbiditic strata and by shallower water deposits (lowstand wedges). Syntheses of paleogeographic reconstructions for different time intervals were published by Legarreta and Uliana (Reference Legarreta and Uliana1996, fig. 9, Reference Legarreta, Uliana and Caminos1999, figs. 5–7), Vicente (Reference Vicente2005, Reference Vicente2012), and Arregui et al. (Reference Arregui, Carbone, Martínez, Leanza, Arregui, Carbone, Danieli and Vallés2011, figs. 5, 6), among others.

Ammonite faunas are abundant and diverse in both the Neuquén and Chubut basins. A detailed local biostratigraphy, which is well correlated to the standard zonation, was developed by Riccardi (Reference Riccardi2008a, Reference Riccardib) and Riccardi et al. (Reference Riccardi, Damborenea, Manceñido, Leanza, Leanza, Arregui, Carbone, Danieli and Vallés2011). This is the age framework used as reference in this paper (as shown in Figs. 2, 3).

Figure 2. Selected sections arranged from north to south, with the distribution in space and time of the genus-group taxa treated in this paper. Biostratigraphic framework from Riccardi (Reference Riccardi2008a, Reference Riccardib) and Riccardi et al. (Reference Riccardi, Damborenea, Manceñido, Leanza, Leanza, Arregui, Carbone, Danieli and Vallés2011). All sections sketched to the same scale and leveled to the base of the Toarcian.

Figure 3. Stratigraphic distribution in Argentina of species described. Local ammonite biozonation and its equivalence to the standard zonation from Riccardi (Reference Riccardi2008a, Reference Riccardib).

Materials and methods

Stratigraphic sections were logged at most of the localities listed in Figure 1, but only the most relevant to this study are sketched in Figure 2. The entire fauna was recorded and/or sampled at each fossiliferous bed, but only those horizons containing Trigoniida are indicated in the figure. A synthesis of the stratigraphic range for each species is depicted on Figure 3.

Terminology

We follow Carter et al. (Reference Carter, Harries, Malchus, Sartori, Anderson, Bieler and Bogan2012) for general morphologic terminology (Fig. 4). Accordingly, we use “costae” or “ribs” for shell surface ornamentation structures that are not expressed in the interior of the shell, and “folds” for undulations that affect the entire thickness of the shell. Some of the terms used here need explanation. For instance, the marginal and escutcheon carinae are typical characters of the group, to the point that sometimes they have been described even when the shell lacks an actual carina. Because these differences may bear importance in the phylogenetic study of the group, we distinguish and apply the following terms: (1) “carina” when a protruding elevation is developed (Fig. 4.3), sometimes (though not always) as a fold in the shell; (2) “angulation” (sensu Cooper, Reference Cooper1989) when there is a sharp change in orientation between the area and the other surfaces (Fig. 4.4), developing a linear structure equivalent in position to the carina, but not a carina strictly speaking; and (3) “bend” (see Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008, p. 66 under “Description” for Prosogyrotrigonia tenuis Pérez and Reyes in Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008) for a gentle change in orientation between the area and the other surfaces (Fig. 4.5). The term “stepped angulation” is used when the boundary between the area and the escutcheon is an angulation, but because the escutcheon is depressed, a small step between both surfaces is developed (Fig. 4.4). Similar to the carinae, an antecarinal sulcus occasionally has been described, even when there is no actual depression. Thus, the term “antecarinal sulcus” is restricted to a true depression anterior to the marginal carina, angulation, or bend (Fig. 4.2), and “antecarinal space” is used for flat surfaces (leveled with the flank) showing an abrupt difference in ornamentation relative to the flank (Fig. 4.1).

Figure 4. Morphology and terminology. (1, 2) Main descriptive terminology for trigoniid shell features; (3–5) transverse sections of valve, showing different types of contact between escutcheon (es) and area (a), and between area and flank (fl): (3) prominent escutcheon and marginal carinae, (4) stepped escutcheon angulation and marginal angulation, (5) escutcheon and marginal bends; (6, 7) trigonian-grade hinge in left and right valves, showing hinge notation, m.b. = myophoric buttress.

In addition to the usual kinds of costae orientation in shell ornamentation (e.g., radial, commarginal, and oblique), the term “sub-commarginal” is here used to refer to flank costae where the costal segment on the central part of the flank is commarginal, but on the anterior part, it cuts across growth lines and meets the anterior margin at high angles (see Poulton, Reference Poulton1979, p. 12, text-fig. 4, characterized as “pseudoconcentric”; Fig. 4.1).

Some genera may develop an “internal radial ridge” (sensu Cox, Reference Cox1952, p. 57–58, under Prorotrigonia, and p. 59–60, under Pterotrigonia) on the posterior part of the inner surface of the shell, which is approximately coincident with the midline of the area. According to Gould and Jones (Reference Gould and Jones1974), this internal radial ridge may have helped these bivalves separate inhalant from exhalant currents.

Dentition notation is the most generally used for the group (Fig. 4.6, 4.7). Trigonian-grade hinge has been characterized by the presence of a prominent, subtriangular, and extremely broad median tooth on the left valve (tooth 2 on Fig. 4.6), with a concave ventral surface giving it a bifid aspect, and with anterior and posterior faces bearing strong transverse ridges or striae (Cox, Reference Cox1952; Newell and Boyd, Reference Newell and Boyd1975; Poulton, Reference Poulton1979; Boyd and Newell, Reference Boyd and Newell1997). The two main teeth of the right valve (teeth 3a and 3b; Fig. 4.7) are widely divergent and more or less symmetrically disposed, also with transverse ridges (Cox, Reference Cox1952; Newell and Boyd, Reference Newell and Boyd1975; Poulton, Reference Poulton1979). Other characters usually mentioned are a gap or hiatus in the right valve hinge plate and the presence of a myophoric buttress (“m.b.” on Fig. 4.6, 4.7) posterior to the anterior adductor muscle scar. This myophoric buttress is fused with tooth 3a in the right valve and with the hinge plate, which forms the socket for this tooth in the left valve (Cox, Reference Cox1952; Fleming, Reference Fleming1964; Newell and Boyd, Reference Newell and Boyd1975).

In contrast, the myophorian-grade hinge (see Newell and Boyd, Reference Newell and Boyd1975, fig. 12.C, 12.D) has been characterized as having a simple (Cox, Reference Cox1952) or bifid tooth 2, which is not particularly prominent (Cox, Reference Cox1952; Fleming, Reference Fleming1964; Newell and Boyd, Reference Newell and Boyd1975). Teeth 3a and 3b are more unequally and asymmetrically arranged than in the trigonian-grade hinge, and are placed on a hinge plate (Cox, Reference Cox1952; Fleming, Reference Fleming1964; although Newell and Boyd, Reference Newell and Boyd1975, mentioned that some species may have a hiatus). Dental striations are variably developed in the myophorian-grade hinge, although the striation is less conspicuous than that of the trigonian-grade hinge (Cox, Reference Cox1952; Newell and Boyd, Reference Newell and Boyd1975). Newell and Boyd (Reference Newell and Boyd1975) and Boyd and Newell (Reference Boyd and Newell1997) also mentioned, as a distinctive character of myophorian-grade hinge, the elongation of the posterior limb of the tooth 2, which functioned as a second inner pseudolateral tooth.

Although the trigonian-grade hinge definition provided above fits well for the hinges of most, if not all, post-Triassic Trigoniida, that is not the case for Triassic representatives, where the different elements may be variably combined (e.g., Boyd and Newell, Reference Boyd and Newell1997; Hautmann, Reference Hautmann2003). This mosaic combination of characters may be indicative of a polyphyletic origin for the trigonian-grade hinge, as suggested by Newell and Boyd (Reference Newell and Boyd1975). Although the subject is beyond the scope of this study, when discussing some Triassic representatives of the group, we follow Boyd and Newell (Reference Boyd and Newell1997) and consider that the minimum requirements for a hinge to be defined as trigonian-grade are: (1) to have well-developed striation on both surfaces of teeth 2 and 3a (and on the corresponding sockets), and (2) the absence of the elongate posterior limb on tooth 2.

Shell size is characterized by length according to the following scheme: length <20 mm = very small shell; 20 to <40 mm = small shell; 40 to <60 mm = medium-sized shell; 60 to <80 mm = large shell; length ≥80 mm = very large shell. Measurements are given in mm, and the following abbreviations are used: L = length, H = height, W = width of both valves, V = width of a single valve.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

Specimens collected by the authors are housed in the following repositories: IANIGLA-PI = Instituto Argentino de Nivología, Glaciología y Ciencias Ambientales, Mendoza, Argentina; MCF-PIPH = Museo Municipal Carmen Funes, Plaza Huincul, Argentina; MLP = División Paleontología Invertebrados, Museo de Ciencias Naturales de La Plata, La Plata, Argentina; MOZ-PI = Museo Provincial de Ciencias Naturales “Dr. Prof. Juan A. Olsacher”, Zapala, Argentina; and MPEF-PI, Museo Paleontológico Egidio Feruglio, Chubut, Argentina. Further specimens examined are housed in: BMNH = Burke Museum of Natural History, Seattle, USA; CPBA = Geology Department, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina; SIRAME-SEGEMAR and DNGM = Dirección Nacional de Geología y Minería, Buenos Aires, Argentina; GSC = Geological Survey of Canada, Calgary, Canada; IGPB = Institute of Geosciences, Paleontology Section, Bonn, Germany; NHMB = Naturhistorisches Museum Basel, Basel, Switzerland; SNGM = Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería, Santiago, Chile; MNHN = Muséum Nationale d’ Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France. A list of Argentinian Trigoniida specimens included in this study by species, locality, repository abbreviation, and local zonation is provided in Appendix 1.

The synonymy lists were prepared according to Matthews (Reference Matthews1973) to indicate the degree of confidence in allocation of each entry. They include only published records.

Systematic paleontology

Order Trigoniida Dall, Reference Dall1889

Superfamily Trigonioidea Lamarck, Reference Lamarck1819

Remarks

According to Bieler et al. (Reference Bieler, Carter and Coan2010) and Carter et al. (Reference Carter, Altaba, Anderson, Araujo, Biakov, Bogan and Campbell2011), this superfamily includes members representing the three hinge grades (schizodian-grade, myophorian-grade, and trigonian-grade). Of interest for this report are the families Groeberellidae, Trigoniidae, and Prosogyrotrigoniidae, all with a trigonian-grade hinge, and the family Myophoriidae, with a myophorian-grade hinge and without any Jurassic representatives, but probably ancestral to the other three.

Family Groeberellidae Pérez, Reyes, and Damborenea, Reference Pérez, Reyes and Damborenea1995

Remarks

The family Groeberellidae was characterized by Pérez et al. (Reference Pérez, Reyes and Damborenea1995) as having a myophoriform shell (i.e., subquadrate, inflated, orthogyrate to slightly prosogyrate), trigonian-grade hinge and a flank ornamentation dominated by radial costae. They inferred an origin from myophorid ancestors independent from that of other trigoniids.

General shell morphology in Groeberella corresponds well to that of some Triassic species with myophorian-grade hinges, and for this reason Groeber (Reference Groeber1924) assigned a Triassic age to the beds bearing the type material. Costatoria, for example, is characterized by the presence of well-developed radial costation, in some species with wide concave interspaces (see Hautmann, Reference Hautmann2001, figs. 26.10, 26.11, 27.1–27.11 for some examples). Although being most abundant in the Tethys and in Japan (Ros Franch et al., Reference Ros Franch, Márquez Aliaga and Damborenea2014, p.120, fig. 42), there are also a few mentions from the American Pacific margin (Chong and Hillebrandt, Reference Chong and von Hillebrandt1985, Costatoria sp., Norian or Rhaetian from Quebrada San Juan, Antofagasta Region, North Chile; Damborenea and González-León, Reference Damborenea and González-León1997, Costatoria? sp., Upper Triassic, probably Norian, of Sierra del Álamo, Sonora, Mexico). The record from Mexico shows poorly developed striation on hinge teeth not covering the entire occluding surfaces, but, as in Groeberella, striation does not develop on the posterior face of 3b (Damborenea and González-León, Reference Damborenea and González-León1997, p. 192, fig. 8.3, 8.4).

In contrast, some authors (e.g., Levy, Reference Levy1967; Leanza, Reference Leanza1993) related Groeberella to the Minetrigoniinae, with a trigonian-grade hinge, flank sculpture of intersecting radial and commarginal costae, and trellised ornament on the area (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1954; Fleming, Reference Fleming1987).

Genus Groeberella Leanza, Reference Leanza1993

Type species

Myophoria neuquensis Groeber, Reference Groeber1924, Pliensbachian, Neuquén, Argentina.

Diagnosis

Subquadrangular, inequivalve, palmate shell. Orthogyrate to slightly prosogyrate umbos. Prominent escutcheon and marginal carinae, and few widely spaced radial costae on the flank. Intercostal (and intercarinal) spaces concave. Trigonian-grade hinge.

Remarks

The diagnosis of the genus is adapted from Pérez et al. (Reference Pérez, Reyes and Damborenea1995). Besides the type species, early Sinemurian material from Chile was referred to Groeberella sp. (Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Reyes and Damborenea1995). Also, an early Pliensbachian left valve from Mexico was described as Groeberella sp. A (Scholz et al., Reference Scholz, Aberhan, González-León, Blodgett and Stanley2008), and a fragmentary specimen from Neuquén referred to the Bajocian was likewise left in open nomenclature as Groeberella sp. by Leanza (Reference Leanza1993, p. 19).

Groeberella neuquensis (Groeber, Reference Groeber1924)

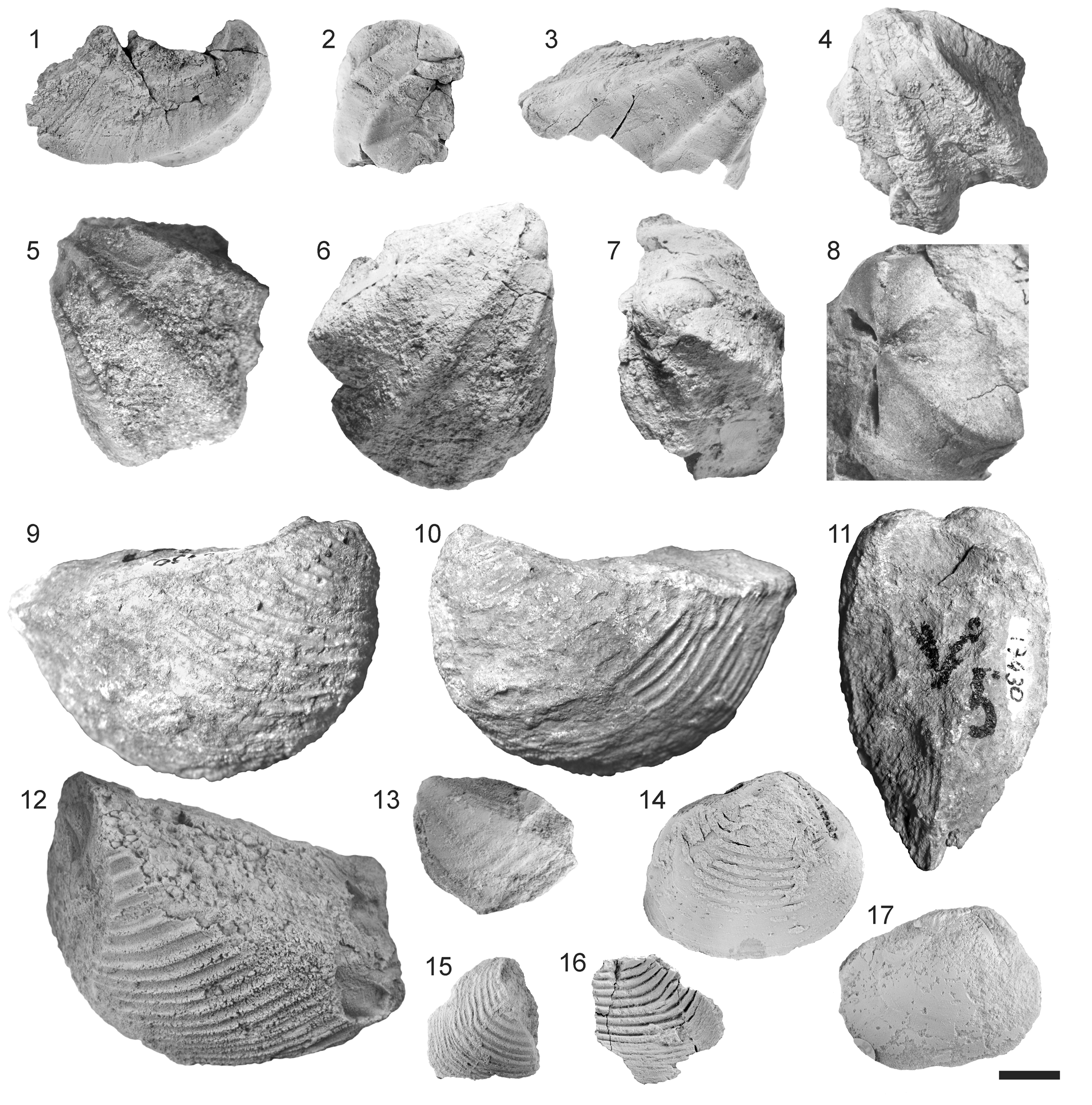

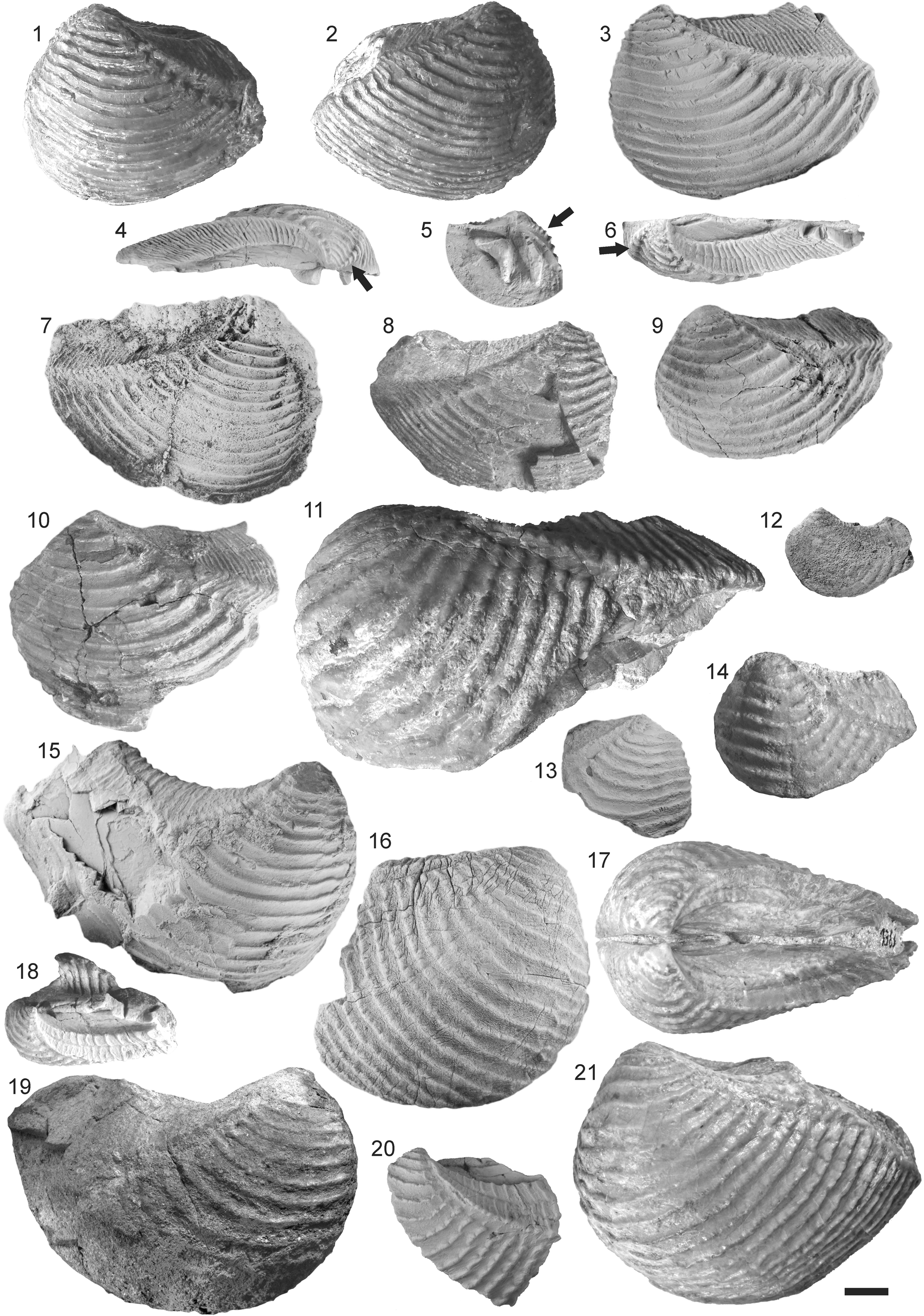

Figure 5.1–5.8

- v* Reference Groeber1924

Myophoria neuquensis Groeber, p. 92, pl. 1, figs. a, b.

- v Reference Windhausen1931

Myophoria neuquensis; Windhausen, p. 179, fig. 71. [reproduced from Groeber, Reference Groeber1924]

- v Reference Carral-Tolosa1942

Myophoria neuquensis; Carral-Tolosa, p. 59, pl. 6, figs. 3a–c.

- v Reference Levy1967

Myophorigonia neuquensis; Levy, p. 14, figs. 1a–f.

- Reference von Hillebrandt and Schmidt-Effing1981

Myophorigonia neuquensis; Hillebrandt and Schmidt-Effing, p. 10.

- Reference Pérez1982

Myophorigonia aff. M. neuquensis; Pérez, p. 40, pl. 15, figs. 2–5, appendix 1.

- v Reference Damborenea and Manceñido1992

‘Myophorigonia’ neuquensis; Damborenea and Manceñido, p. 134, pl. 1, fig. 5a.

- v Reference Damborenea and Manceñido1992

Myophorigonia neuquensis; Damborenea et al., pl. 115, fig. 14.

- Reference Leanza1993

Groeberella neuquensis; Leanza, p. 18, pl. 1, figs. 2, 3.

- Reference Pérez, Reyes and Damborenea1995

Groeberella neuquensis; Pérez et al., p. 147, pl. 1, figs. 1–3, 5–13, 15, 16, 18–22.

- Reference Pérez and Reyes1997

Groeberella neuquensis; Pérez and Reyes, p. 573.

- v Reference Pérez and Reyes2008

Groeberella neuquensis; Pérez and Reyes in Pérez et al., p. 58, pl. 1, figs. 1–13, 15, 17–18.

- v Reference Riccardi, Damborenea, Manceñido, Leanza, Leanza, Arregui, Carbone, Danieli and Vallés2011

Groeberella neuquensis; Riccardi et al., fig. 7.3.

Type materials

Holotype: DNGM 7337 (= casts SNGM 7366, MLP 24324); right valve from the Pliensbachian of Puruvé-Pehuén, Neuquén Province, Argentina. Figured by Groeber (Reference Groeber1924, pl. 1, figs. a, b), Damborenea and Manceñido (Reference Damborenea and Manceñido1992, pl. 1, fig. 5a), Damborenea et al. (Reference Damborenea, Polubotko, Sey, Paraketsov and Westermann1992, pl. 115, fig. 14), Pérez et al. (Reference Pérez, Reyes and Damborenea1995, pl. 1, fig. 1), and Figure 5.1–5.3 herein.

Occurrence

The type locality is Puruvé-Pehuén (somewhere between Ñireco and Lonqueo in central Neuquén). Also recorded from: Las Chilcas, Puesto Araya, Quebrada de los Caballos (Atuel River region); La Bajada, Portezuelo Ancho (Las Leñas/Valle Hermoso region); Estancia Santa Isabel, Salitral Grande Carrán Curá, Cerro Roth Sur (Piedra Pintada region); and Nueva Lubecka (Genoa River region). Leanza (Reference Leanza1993, p. 10) mentioned the presence of this species at La Amarga, near Rincón del Águila (central Neuquén), but he listed neither this locality when describing the species (p. 19) nor this species among the fauna from that locality (p. 68). In Argentina, its stratigraphical range is late Sinemurian to late Pliensbachian (Fig. 3). This species seems to have had a wider stratigraphical range in Chile, extending at least to early Aalenian according to Pérez et al. (Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008, p. 55).

Description

Medium-sized, subquadrangular, orthogyrate to slightly prosogyrate shell. Umbos anteriorly located, slightly displaced from each other (Fig. 5.8). Escutcheon margin feebly convex; posterior margin slightly concave. Ventral margin palmate due to the presence of two radial ribs (Fig. 5.4). Anterior margin slightly convex. Escutcheon wide, smooth or with growth lines; escutcheon carina prominent. Area smooth (or with growth lines), slightly concave (Fig. 5.1, 5.4); prominent marginal carina. Area and flank meet at an angle of ~90°. Flank with two prominent radial ribs; spaces between the ribs (and marginal carina) wide and concave. Flank ribs and carinae as folds of the shell, shell thicker on the costae than on the interspaces. Costae and carinae on the left valve with transverse crenulations (Fig. 5.4, 5.5); intercostal spaces on the flank with thin commarginal costellae, more densely arranged than the crenulations. Costae sharper on the right valve (Fig. 5.1–5.3), lacking transverse ornamentation.

Figure 5. Trigoniida from the Early Jurassic of Argentina. Scale bar = 10 mm. (1–8) Groeberella neuquensis (Groeber): (1–3) holotype, DNGM 7337, right valve, dorsal, anterior and right lateral views, Pliensbachian, Puruvé-Pehuén; (4) DNGM 7340a, left valve, lateral view, Pliensbachian, Nueva Lubecka; (5) MPEF-PI 6401, left valve, Pliensbachian, Nueva Lubecka; (6, 7) DNGM 7339, right valve, lateral and dorsal views, Pliensbachian, Nueva Lubecka; (8) MLP 27844, internal molds of both valves open in butterfly position, early Pliensbachian, Puesto Araya; (9–11) Trigonia? sp. 2, CPBA 17430, right lateral, left lateral and dorsal views, early Toarcian, Arroyo La Laguna; (12, 13) Trigonia? sp. 1, early Toarcian, Arroyo La Laguna: (12) MLP 36312a, left valve; (13) MLP 36311, juvenile? left valve; (14–17) Prosogyrotrigonia tenuis Pérez and Reyes, early Sinemurian, Arroyo Malo: (14) MLP 32789, composite mold with shell remains, right lateral view; (15) MLP 32802, postero-ventral fragment of right valve composite mold; (16) MLP 32828, postero-ventral fragment of right valve external mold; (17) MLP 32805, internal mold, right lateral view.

Trigonian-grade hinge (sensu Boyd and Newell, Reference Boyd and Newell1997). Tooth 2 broad and conspicuous, ventrally bifid; teeth 4a and 4b relatively short. Tooth 3a thicker than tooth 3b. Few strong ridges on both occluding surfaces of 2 and 3a, on the anterior face of 3b, and on the posterior face of 4a. Nymph short.

Materials

Thirty-five specimens were examined: the holotype and DNGM 7338–7340, MLP 16387, 17478, 17724, 27246–27253, 27844, 27931, 28683, 36194; MPEF-PI 2913, 2918, 2993, 3392, 6397, 6435; IANIGLA-PI 3344; plus the specimen MOZ-PI 4060 figured by Leanza (Reference Leanza1993).

Measurements

Holotype (DNGM 7337): L = 42 mm (broken ventrally); DNGM 7339: L = 47 mm, H = 44 mm; DNGM 7340: H = 47 mm.

Remarks

The species is endemic to South America (Damborenea et al., Reference Damborenea, Echevarría and Ros-Franch2013).

Family Trigoniidae Lamarck, Reference Lamarck1819

Remarks

The Trigoniidae were described by Cooper (Reference Cooper1991) as having a trigonal to rhomboidal shell shape, a trigonian-grade hinge, subcommarginal flank ornamentation, a prominent marginal carina, and an area with radial ornamentation (at least on early stages). Some previous authors (e.g., Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1954; Poulton, Reference Poulton1979), provided a similar characterization for the subfamily Trigoniinae.

The earliest representatives of this family are included in the genus Primatrigonia (defined as a subgenus of Trigonia by Repin in Paevskaya et al., Reference Paevskaya, Polubotko, Repin, Rozanov and Shevyrev2001; see Echevarría et al., Reference Echevarría, Ros Franch and Manceñido2018 for a nomenclatural revision of this taxon). All the species included in Primatrigonia share a subdued ornamentation pattern, with weak radial costellae on the area and very subtle commarginal costellae or prominent growth lines on the flank (nearly smooth in some cases). Trigonia tabacoensis Barthel, Reference Barthel1958 (see also Pérez and Reyes, Reference Pérez and Reyes2008, fig. 1) from the Anisian of Chile, and Trigonia n. sp. A of Fleming (Reference Fleming1987), from the Anisian of New Zealand, may well be included in Primatrigonia. The Chilean species is the oldest within the order with a recognizable trigonian-grade hinge. Other Late Triassic species are Primatrigonia yunnanensis (Guo, Reference Guo1985), from southwestern China, Primatrigonia zlambachiensis (Haas, Reference Haas1909), from Austria, Iran, and Vietnam (Hautmann, Reference Hautmann2001), and Primatrigonia gaytani (von Klipstein, Reference von Klipstein1843) from Austria. The hinge shows some variability among these species (Hautmann, Reference Hautmann2001, p. 120–122). The genus Trigonia probably evolved from Primatrigonia by the development of a stronger ornamentation pattern.

Genus Trigonia Bruguière, Reference Bruguière1789

Type species

Venus sulcata Hermann, Reference Hermann1781, pl. 4, figs. 2–4, 9, 10 (see ICZN, 1955), late Early Jurassic (Toarcian), Gundershoffen, Alsace, France.

Diagnosis

Shell trigonal to trigonally ovate, inequilateral, opisthogyrate. Area bipartite, with reticulate ornament, composed of radial and commarginal costellae. Prominent marginal carina; antecarinal sulcus present on the left valve. Flank with sub-commarginal costae. Escutcheon smooth or with striae.

Remarks

The diagnosis of the genus was compiled from Crickmay (Reference Crickmay1932), Leanza (Reference Leanza1993), and Francis (Reference Francis2000). If Primatrigonia is regarded as a different genus, then the oldest Trigonia representative is the species Trigonia senex Kobayashi and Mori, Reference Kobayashi and Mori1954, from the Hettangian of Japan. During most of the Early Jurassic, the genus occurred in the Pacific (Kobayashi and Mori, Reference Kobayashi and Mori1954; Poulton, Reference Poulton1976, Reference Poulton1979, Ishikawa et al., Reference Ishikawa, Maeda, Kawabe and Rangel Zavala1983; Pérez and Reyes, Reference Pérez and Reyes1991; Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008). By the Toarcian it reached the European Tethys (Hermann, Reference Hermann1781; Agassiz, Reference Agassiz1840; Fürsich et al., Reference Fürsich, Berndt, Scheuer and Gahr2001, Francis and Hallam, Reference Francis and Hallam2003).

Trigonia? sp. 1

Figure 5.12, 5.13

Occurrence

Arroyo La Laguna (Los Patos region), San Juan Province. Early Toarcian (D. hoelderi Biozone [≈ Serpentinum Biozone]) (Fig. 3).

Description

Medium-sized, slightly opisthogyrate shell. Escutcheon poorly preserved, apparently wide. Area wide, ~1/3 of shell surface (Fig. 5.12), with mid radial stepped angulation and thin radial costellae intersected by thin commarginal costellae (Fig. 5.12, 5.13). Marginal carina poorly preserved, prominent (at least in juvenile stages). Flank with sharp sub-commarginal costae, more densely arranged as shell grows.

Materials

Three left valves, MLP 36311, 36312a, 36313.

Measurements

MLP 36311, composite mold: L = 25 mm, H = 24 mm; MLP 36313, composite mold: L = 28 mm, H = 23 mm; MLP 36312a, single valve: L = 55 mm, H = 45 mm, V = 18 mm.

Remarks

Poor preservation of the material prevents a specific taxonomic assignment. Neuquenitrigonia Leanza and Garate-Zubillaga, Reference Leanza, Garate-Zubillaga and Volkheimer1987 was distinguished from Trigonia mainly due to flank ornamentation (oblique to growth lines), but Pérez et al. (Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008) later included material with sub-commarginal flank costae. Unfortunately, they did not discuss the diagnosis for the genus. Yet, based on the material they included, the main difference from Trigonia seems to be the transverse costellae on the escutcheon that occur in Neuquenitrigonia. Escutcheon ornamentation is not preserved in our material; hence, an assignment to Neuquenitrigonia cannot be ruled out. Only two species of Neuquenitrigonia are known: N. hunickeni (Leanza and Garate-Zubillaga, Reference Leanza and Garate-Zubillaga1985), from the Bajocian of Neuquén, Argentina, and middle Toarcian–early Aalenian of Atacama, Chile; and N. plazaensis Pérez and Reyes in Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008, from the middle Toarcian of Atacama, Chile. The second one seems closer in morphology to the material here described. However, Trigonia? sp. 1 is larger, has a wider area, and is somewhat more elongate. Trigonia sp. 1 in Pérez et al. (Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008), from the middle Toarcian of Atacama (Chile), is also similar in morphology, although it is smaller and with middle flank costae more densely arranged; the area ornamentation pattern, on the other hand, is strikingly similar in both taxa. The Toarcian unfigured material from northern Chile referred to Trigonia aff. T. bella Lycett, Reference Lycett1877 (Möricke, Reference Möricke1894, p. 48; see also Pérez and Reyes, Reference Pérez and Reyes1977, p. 11) may be related to this record, according to that broad description. Trigonia sp. B of Ishikawa et al. (Reference Ishikawa, Maeda, Kawabe and Rangel Zavala1983), from the Lower Jurassic of south central Perú, is a rather fragmentary specimen, but the observable characters agree with those of Trigonia? sp. 1.

Most Middle Jurassic Trigonia species from the Neuquén Basin can be distinguished easily from Trigonia? sp. 1. Trigonia stelzneri Gottsche, Reference Gottsche and Stelzner1878, has a narrower area, a more clearly opisthogyrate shell, and is relatively shorter. Trigonia corderoi Lambert, Reference Lambert1944, is larger, much more opisthogyrate, and with stronger and blunter flank costae. Trigonia mollensis Lambert, Reference Lambert1944, is more similar to Trigonia? sp. 1 in general shell shape, but the flank costae show some undulations that are absent in the Toarcian material. Trigonia losadai Leanza, Reference Leanza1993 has stronger and more sparsely arranged flank costae.

Trigonia senex from the Hettangian of Japan (Kobayashi and Mori, Reference Kobayashi and Mori1954) bears a large area and an ornamentation pattern similar to that in Trigonia? sp. 1. According to its original description, the Japanese species is particular in having an insignificant marginal carina; unfortunately, the marginal carina is not preserved in any of our specimens. Trigonia sp. described by Poulton (Reference Poulton1976), based on probably Pliensbachian material from south-western British Columbia (Canada), is similar in general shell shape (though slightly smaller); the most noticeable differences are a closer spacing of flank costae and a coarser commarginal ornamentation on the area in the North American taxon. The type species, Trigonia sulcata (Hermann, Reference Hermann1781), and its probable synonym, Trigonia similis Agassiz, Reference Agassiz1840 (see also Bayle Reference Bayle1878, pl. 119, figs. 3–5, as Lyriodon simile; Cox et al., Reference Cox, Newell, Boyd, Branson, Casey, Chavan and Coogan1969, fig. D66.1), both from the late Early Jurassic of Alsace, are similar in general ornamentation pattern, but they differ from Trigonia? sp. 1 by their more opisthogyrate shell shape.

Trigonia? sp. 2

Figure 5.9–5.11

Occurrence

Arroyo La Laguna (San Juan Province), early Toarcian (D. hoelderi ? Biozone [≈ Serpentinum Biozone]) (Fig. 3).

Description

Large, clearly opisthogyrate shell. Escutcheon wide, poorly preserved. Area narrow, ~1/4 of shell surface (Fig. 5.11), and almost at right angles to the flank; with thin radial costellae intersected by thin commarginal costellae. Mid radial stepped angulation on the area. Marginal carina poorly preserved, seemingly prominent. Antecarinal sulcus narrow. Semicircular flank margin, though in one of the shells the ventral margin is clearly longer than the anterior one. Flank with sub-commarginal sharp costae, less closely spaced as shell grows (8–9 costae/cm on umbonal region, 3–5 costae/cm in middle flank), in late growth stages dense again (6 costae/cm).

Materials

Two shells, CPBA 17430, 17478.

Measurements

CPBA 17430; L = 65 mm, H = 44 mm, W = 36 mm.

Remarks

Although similar to Trigonia? sp. 1, Trigonia? sp. 2 shows some differences that suggest a different species. In Trigonia? sp. 2, the shell is larger and more opisthogyrate; besides, the area is narrower, and area and flank surfaces are almost perpendicular. Both taxa share a pattern of flank costae growing closer at later growth stages; anyhow, this is an age-related character.

As in Trigonia? sp. 1, the assignment to Neuquenitrigonia cannot be ruled out. Trigonia? sp. 2 is similar to Neuquenitrigonia plazaensis, but larger and more opisthogyrate. Trigonia sp. 1 in Pérez et al. (Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008), from the middle Toarcian of Atacama (Chile), is smaller and less opisthogyrate.

Trigonia stelzneri Gottsche, Reference Gottsche and Stelzner1878, from the Bajocian of Paso del Espinacito (San Juan Province), seems close to Trigonia? sp. 2, though it has a subtriangular flank; it is also relatively shorter. Besides, flank costae in T. stelzneri tend to bend ventrally at their anteriormost portion. Trigonia corderoi Lambert, Reference Lambert1944, also has a subtriangular flank with stronger and blunter costae. Trigonia mollesensis Lambert, Reference Lambert1944, bears flank costae with some undulations absent in the Toarcian material. The two species described by Lambert also have a relatively narrower area with stronger radial costellae. Trigonia losadai Leanza, Reference Leanza1993, has stronger and more sparsely spaced flank costae.

This taxon seems close to Trigonia sulcata, although it appears to have a narrower area and, if the illustrations of the European species (Hermann, Reference Hermann1781, pl. 4, figs. 2–4, 9, 10) are to be trusted, Trigonia? sp. 2 differs also by its area orthogonal to the flank. The specimen from Normandy illustrated by Hermann (Reference Hermann1781, pl. 4, figs. 13, 14) as intermediate between T. sulcata and T. dubia (Hermann, Reference Hermann1781) is quite similar to Trigonia? sp. 2.

Family Prosogyrotrigoniidae Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1954

Remarks

Kobayashi (Reference Kobayashi1954) characterized the Prosogyrotrigoniidae as lacking a prominent marginal carina and having smooth shell or ornamented by commarginal costae. Cooper (Reference Cooper1991) also considered the prosogyrate umbo and rounded posterior margin as characteristic of the family, and he assumed an origin from the Trigoniidae. Nevertheless, other authors (e.g., Kobayashi and Tamura, Reference Kobayashi and Tamura1968, p. 129–130, table 7) considered the possibility of an independent origin from myophorid genera.

Genus Prosogyrotrigonia Krumbeck, Reference Krumbeck and Wanner1924

Type species

Prosogyrotrigonia timorensis Krumbeck, Reference Krumbeck and Wanner1924, p. 245, by monotypy. Late Triassic, Timor.

Diagnosis

Subovate shell with prosogyrate beaks, trigonian-grade hinge, commarginal ornamentation throughout the shell surface, and with marginal bend, usually associated with a change in costae density between the flank and the area.

Remarks

The diagnosis is modified from Cox (Reference Cox1952) and Cox et al. (Reference Cox, Newell, Boyd, Branson, Casey, Chavan and Coogan1969). The type species, Prosogyrotrigonia timorensis, was recorded from the Late Triassic of Timor (late Norian, according to Hasibuan, Reference Hasibuan2010); it shows the typical prosogyrate shell shape, commarginal ornamentation, and marginal bend of other species (Kobayashi and Mori, Reference Kobayashi and Mori1954). Prosogyrotrigonia iranica Fallahi et al., Reference Fallahi, Gruber, Tichy and Zapfe1983, from the Norian–Rhaetian of Iran and Late Triassic of Yunnan in China (Hautmann, Reference Hautmann2001, fig. 11), has a subtriangular shell shape, thin and dense commarginal costae, and a rounded marginal bend.

Early Jurassic species included in Prosogyrotrigonia show few differences from Triassic representatives. In this sense, Prosogyrotrigonia can be considered a conservative lineage during the Triassic/Jurassic transition. Early Jurassic records include the species P. tenuis Pérez and Reyes in Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008, from southern South America, and P. inouyei (Yehara, Reference Yehara1921), from the Hettangian or early Sinemurian of Japan (Kobayashi and Mori, Reference Kobayashi and Mori1954). Frebold and Poulton (Reference Frebold and Poulton1977) and Poulton (Reference Poulton1991, p. 45, 48) also reported P.? cf. P. inouyei from the early Hettangian of Yukon, in northern Canada. From the early Sinemurian of Sonora, Mexico, Scholz et al. (Reference Scholz, Aberhan, González-León, Blodgett and Stanley2008, p. 292–293, figs. 10.L, 10.M) illustrated Prosogyrotrigonia sp. A, comparable to both species mentioned above. Pérez et al. (Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008) also mentioned three other undetermined species of Prosogyrotrigonia, mostly from the Sinemurian of Chile, two of which have the commarginal costae broken into irregular tubercles. Considering this appearance of tubercles in the genus, the unusual Hettangian Quadratojaworskiella acarinata Pérez and Reyes in Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008, p. 78, from Chile, is here referred to Prosogyrotrigonia (see Remarks under Quadratojaworskiella).

Prosogyrotrigonia tenuis Pérez and Reyes in Pérez et al., Reference Pérez and Reyes2008

Figure 5.14–5.17

- Reference Pérez and Reyes1997

Prosogyrotrigonia sp.; Pérez and Reyes, p. 574.

- *v Reference Pérez and Reyes2008

Prosogyrotrigonia tenuis Pérez and Reyes in Pérez et al., p. 64, pl. 3, figs. 1–3, 5–7, 11, 12, pl. 4, figs. 1–12, 14, 15, pl. 5, figs. 2, 5.

- v Reference Damborenea and Echevarría2015

Prosogyrotrigonia tenuis; Damborenea and Echevarría, appendix 2.

- v Reference Damborenea, Echevarría and Ros-Franch2017

Prosogyrotrigonia tenuis; Damborenea et al., p. 101, fig. 4, table 2.

Type material

Holotype: SNGM 486 (Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008, pl. 4, figs. 11, 12), right valve with ventral margin incomplete; hinge partly visible. From Cerros de Cuevitas, northern Chile.

Occurrence

Arroyo Malo section (Atuel River region), Mendoza Province. Early Sinemurian (Coroniceras-Arnioceras Biozone [≈ Bucklandi-Semicostatum Biozone]) (Fig. 3). The species was first described from Chile, where it occurs in the late Hettangian west of Quillagua and late Hettangian and earliest Sinemurian of Cerros de Cuevitas, Antofagasta (Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008).

Description

Poorly preserved material. Small, weakly inflated, orthogyrate to slightly prosogyrate shell (Fig. 5.14). Escutcheon margin straight to slightly convex, at an obtuse angle with the anterior margin (~117–118°). Anterior margin strongly convex, gradually merging with the convex ventral margin. Postero-ventral angle rounded; posterior margin straight to slightly convex. Rounded marginal bend separating flank from area (Fig. 5.15, 5.16). Area occupying 1/4–1/3 of shell surface (Fig. 5.14).

Shell ornamented with commarginal costae, continuous through flank and area (escutcheon not preserved). Intercostal spaces similar in width to costae, sometimes slightly wider; ~6–7 costae/cm at mid-flank. Costae sometimes thinner on the area than on the flank (Fig. 5.15). Area occasionally with bifurcated or extra costellae (Fig. 5.15, 5.16). Costae end abruptly at the escutcheon edge. Costae thinner, more densely packed, and somewhat irregular at late growth stages (Fig. 5.15, 5.16).

Crenulated tooth 3a poorly preserved in one internal mold (Fig. 5.14). Adductor muscle scars very slightly impressed; continuous pallial line (Fig. 5.17).

Materials

Five fragmentary and sometimes strongly corroded shells, one composite mold, one internal mold, and one external mold: MLP 32711, 32786, 32789, 32802, 32803, 32805, 32815, and 32828.

Measurements

MLP 32786: L = 38 mm, H = 31 mm; MLP 32789: L = 39 mm, H = 31 mm; MLP 32805: L = 34 mm, H = 27 mm.

Remarks

The characters observed on the studied specimens show no significant differences from the material described by Pérez et al. (Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008) from Chile. The shell seems to be less rectangular in some Argentinian specimens, with the anterior margin slightly more protruding (Fig. 5.14) and narrower area, but such differences are here regarded as intraspecific. Although Pérez et al. (Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008) described thin flank costae separated by much wider intercostal spaces, some of their figured specimens (e.g., pl. 4, figs. 9, 15, pl. 5, fig. 2) show costae as wide as the intercostal spaces. Within the bounds of intraspecific variability accepted by Pérez et al. (Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008), the material from west of Quillagua (late Hettangian) is remarkable: shells are orthogyrate to slightly prosogyrate, with a relatively large area (1/3–2/5 of shell surface) and flank costae are densely spaced (8 or more costae/cm). In these shells, area costae are thinner than those from the flank, they are more frequently dichotomous, and the flank costae tend to swell over the marginal bend (Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008, pl. 4, fig. 3). All these characters closely resemble the genus Frenguelliella, hinting to a possible phylogenetic relationship between both genera, as suggested by Poulton (Reference Poulton1979, p. 18; see also Remarks under Frenguelliella).

Prosogyrotrigonia tenuis has been recorded from the late Hettangian–early Sinemurian of southern South America (Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008; this paper). The contemporary species, Prosogyrotrigonia sp. A, is smaller than P. tenuis and more variable in elongation/shell shape (Scholz et al., Reference Scholz, Aberhan, González-León, Blodgett and Stanley2008, figs. 10L, 10M), with costae thinner and more densely packed. Shells of P.? cf. P. inouyei in Frebold and Poulton (Reference Frebold and Poulton1977, pl. 2, figs. 5–9) are somewhat larger and coarser, with a somewhat narrower area. The only known specimen of Prosogyrotrigonia sp. 1 of Pérez and Reyes in Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008, is very similar to P. tenuis, and was found in the same locality where the Hettangian record of that species appeared; the main difference between both taxa is the breaking up of commarginal costae into irregular tubercles in P. sp. 1.

Superfamily Myophorelloidea Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1954

Remarks

Cooper (Reference Cooper1991) described the superfamily Myophorelloidea as having posteriorly produced shells with nodate marginal and escutcheon carinae. He characterized the area as broad, with transverse ornamentation and a longitudinal groove. According to his description, flank costae are subcommarginal and entire in primitive forms, but strongly oblique and nodate in more derived forms. The species we describe here share as a distinctive character an area with transverse costellae and a radial median groove (replaced by a row of pustules in certain derived forms, such as Poultoniella new genus).

Family Frenguelliellidae Nakano, Reference Nakano1960

Remarks

Frenguelliellinae has been regarded as a subfamily of the Laevitrigoniidae (Bieler et al., Reference Bieler, Carter and Coan2010; Carter et al., Reference Carter, Altaba, Anderson, Araujo, Biakov, Bogan and Campbell2011). The subfamily Laevitrigoniinae includes mainly genera characterized by weak sculpture, being most likely a polyphyletic group (see Fleming, Reference Fleming1987, p. 37–38 for a discussion on the Laevitrigoniinae). For the time being, we prefer to maintain Frenguelliellidae and Laevitrigoniidae as two different families. The Frenguelliellidae are characterized by shells ornamented with subcommarginal costae (occasionally nodate and oblique), interrupted or attenuated at the antecarinal space (Cooper, Reference Cooper1991).

Genus Frenguelliella Leanza, Reference Leanza1942

Type species

Trigonia inexspectata Jaworski, Reference Jaworski1915, p. 377–380. Pliensbachian, Piedra Pintada (Neuquén, Argentina).

Diagnosis

Shell orthogyrate to clearly opisthogyrate. Well-defined sharp angulations bordering the area, slightly protruding marginal carina in early growth stages. Area with fine commarginal costellae, usually densely spaced. Flank with sub-commarginal costae reaching anterior margin, usually stronger but fewer than in the area. Antecarinal space smooth or delicately ornamented. Escutcheon smooth or with commarginal costellae crossing from the area (though in fewer numbers).

Remarks

Leanza (Reference Leanza1942, p. 164–166) proposed Frenguelliella as a subgenus of Trigonia, and this status was maintained by Cox (Reference Cox1952, p. 54) and Cox in Cox et al. (Reference Cox, Newell, Boyd, Branson, Casey, Chavan and Coogan1969, p. N478). Tamura (Reference Tamura1959) regarded it as a different genus, and this was followed by most subsequent authors. The original diagnosis by Jaworski (Reference Jaworski1915, Reference Jaworski1925) for Trigonia inexspectata and by Leanza (Reference Leanza1942) for the genus is here amended to encompass the observed range of morphological variability displayed in this genus. Frenguelliella was considered a survivor from the Triassic by Tamura (Reference Tamura1959), who described the subgenus Frenguelliella (Kumatrigonia) Tamura, Reference Tamura1959, based on F. (K.) tanourensis Tamura, Reference Tamura1959, from the Upper Triassic of Japan. He distinguished it from Frenguelliella s.s. by the continuity of flank and area costae in the former. Later, Kobayashi and Tamura (Reference Kobayashi and Tamura1968, p. 107) found shells with more numerous costae on the area than on the flank, and hence considered Frenguelliella and Kumatrigonia as synonyms. Nevertheless, there are some differences between Frenguelliella (Kumatrigonia) tanourensis and the Early Jurassic representatives of Frenguelliella. In Kumatrigonia, there is a prominent marginal carina and an antecarinal sulcus (both as folds of the shell surface, Tamura Reference Tamura1959, pl. 2, figs. 1, 4, discernible even on the internal mold, Tamura Reference Tamura1959, pl. 2, fig. 3). Conversely, Early Jurassic Frenguelliella species bear a prominent carina in the earliest juvenile stages, which is replaced by a sharp marginal angulation and a flat antecarinal space in late juvenile and adult stages. Also, the area in the Triassic species is strongly concave, while in the Jurassic species it is flat. Furthermore, according to Poulton (Reference Poulton1979), there is a transition in the Early Jurassic from Prosogyrotrigonia to Frenguelliella species in North America, expressed as a progressive differentiation of area, flank, marginal angulations, and antecarinal space in Frenguelliella, as well as the development of finer commarginal ornament on the area. According to this view, the distinction of Frenguelliella from the probably ancestral Prosogyrotrigonia is arbitrary and mainly based on the prosogyrate umbos, the simple ovate outline, and the absence of marginal carina or angulation in the types species of Prosogyrotrigonia (Poulton, Reference Poulton1979, p. 18).

On the other hand, the species included in Frenguelliella have an internal radial ridge on the posterior part of the inner surface of the shell. This ridge is not present in Prosogyrotrigonia tenuis, but it seems to occur in Kumatrigonia nemtinovi (Bychkov, Reference Bychkov and Pokhialainen1985, p. 14–15, pl. 4, fig. 8). Given this uncertainty, Kumatrigonia is regarded here as a different genus, containing only Triassic species (K. tanourensis [Tamura, Reference Tamura1959], K. nemtinovi Bychkov, Reference Bychkov and Pokhialainen1985, and probably Frenguelliella? sp. of Newton et al., Reference Newton, Whalen, Thompson, Prins and Delalla1987), and Frenguelliella is considered to have appeared during the Early Jurassic.

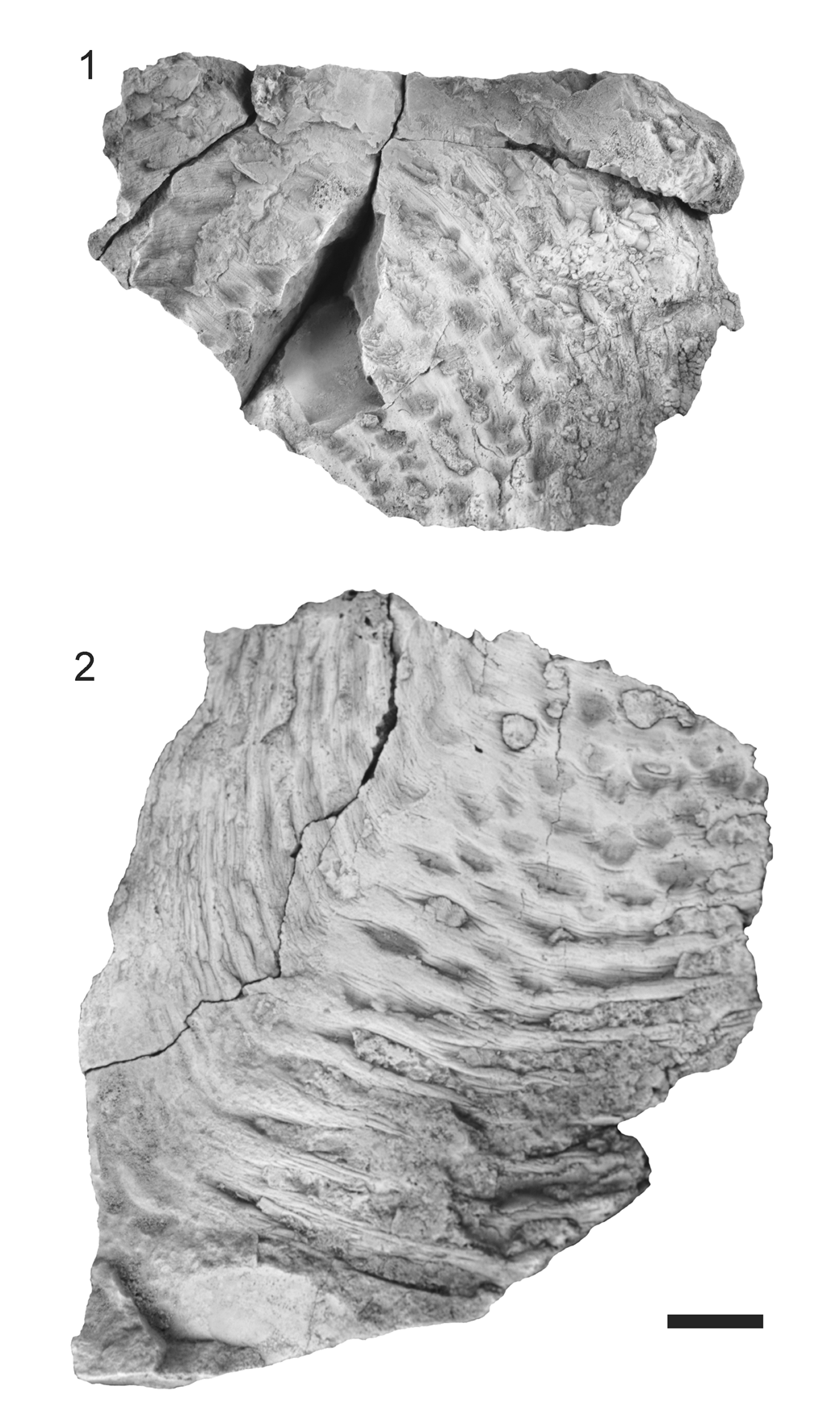

Frenguelliella seems to have been restricted to the Pacific coast of the Americas during the Early Jurassic (Feruglio, Reference Feruglio1934; Leanza, Reference Leanza1942; Lambert, Reference Lambert1944; Poulton, Reference Poulton1979; Ishikawa et al., Reference Ishikawa, Maeda, Kawabe and Rangel Zavala1983; Leanza, Reference Leanza1993; Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008). The earliest representatives appeared during the Sinemurian and were widely distributed. According to Leanza (Reference Leanza1993, Reference Leanza1996), the genus extended to the early Bajocian in the Andes, but records younger than Toarcian proved to be doubtful. The species Frenguelliella perezreyesi Leanza (Reference Leanza1993, p. 27, pl. 2, figs. 1, 2, 7, 8) was described based on two incomplete specimens from early Bajocian beds at Barda Negra Sur, Neuquén. The morphology of the paratype (Fig. 6.4, 6.5; MOZ-PI 3030/2) and of well-preserved topotypic material personally collected at that locality (Fig. 6.1–6.3; MLP 36314) reveals that this species has prosogyrate umbos, a large smooth lunule, and crenulated margin. This is clearly not a trigoniid, and instead is here referred to the crassatelloidean genus Trigonastarte Bigot, Reference Bigot1895.

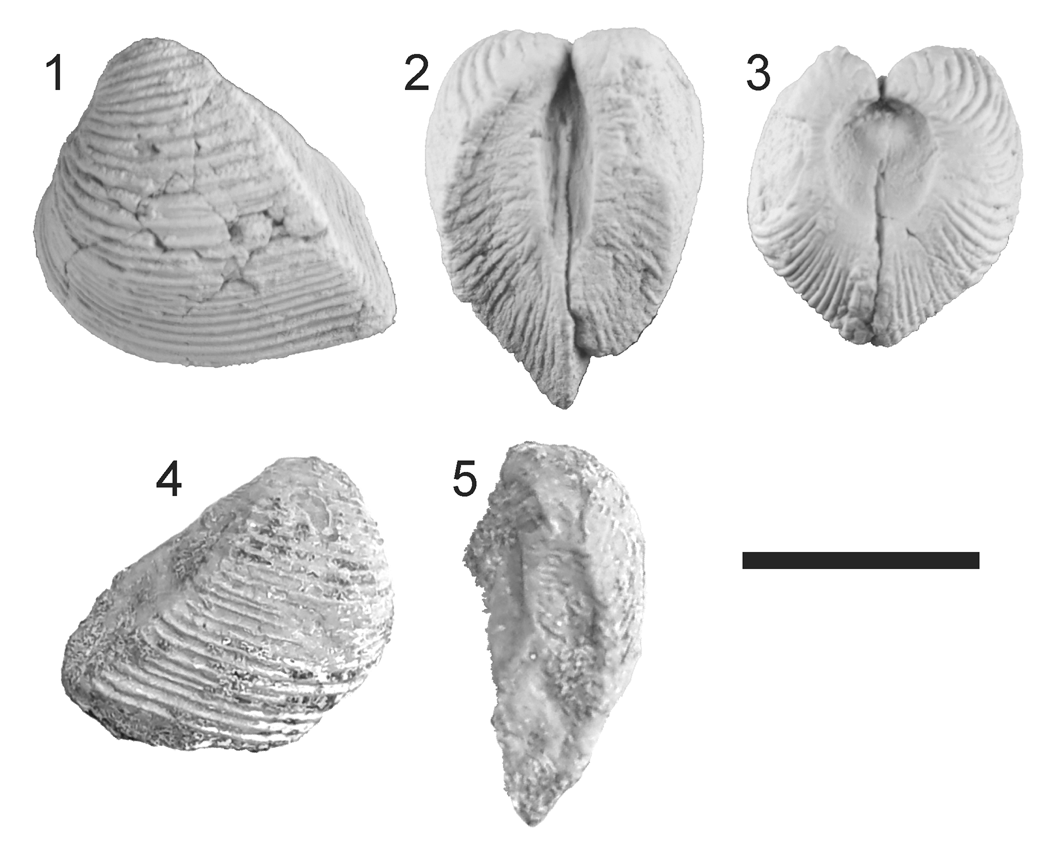

Figure 6. Trigonastarte perezreyesi (Leanza) n. comb., early Bajocian, Barda Negra Sur. Scale bar = 10 mm. (1–3) MLP 36314, complete specimen left lateral, dorsal, and anterior views; (4, 5) paratype, MOZ-PI 3030/2, incomplete right valve right lateral and dorsal views (photographs courtesy of B. Boilini).

Frenguelliella eopacifica new species

Figure 7

- Reference Lees1934

Trigonia aff. T. costatula; Lees, p. 42, pl. 4, fig. 6.

- Reference Frebold1964

Trigonia aff. T. costatula; Frebold, p. 14, pl. 5, fig. 6.

- Reference Poulton1979

Frenguelliella sp. B; Poulton, p. 18, pl. 1, fig. 10.

- v Reference Damborenea and Lanés2007

Frenguelliella cf. F. poultoni; Damborenea and Lanés, p. 78, table 3.B, 3.C.

- v Reference Pérez and Reyes2008

Frenguelliella poultoni; Pérez and Reyes in Pérez et al., p. 72, pl. 5, figs. 6–8.

- p ?Reference Scholz, Aberhan, González-León, Blodgett and Stanley2008

Frenguelliella poultoni; Scholz et al., p. 291, fig.10I, 10J.

- v Reference Damborenea and Echevarría2015

Frenguelliella poultoni; Damborenea and Echevarría, appendix 2.

- v Reference Damborenea, Echevarría and Ros-Franch2017

Frenguelliella cf. F. poultoni; Damborenea et al., p. 101, fig. 4, table 2.

Type materials

Holotype: SNGM 541 from Quebrada Pan de Azúcar, 10 km SW of Las Bombas, Atacama Region, Chile; Sinemurian (probably Obtusum Biozone, Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008), figured here in Figure 7.5. Paratypes SNGM 561 from Quebrada Pan de Azúcar, 10 km SW of Las Bombas, Atacama Region, Chile, Sinemurian (Fig. 7.1), and MLP 32837 from Las Chilcas, Atuel River region, Mendoza Province, late Sinemurian (Fig. 7.7).

Diagnosis

Small, subtriangular to subrectangular, orthogyrate to slightly opisthogyrate shell. Escutcheon smooth; escutcheon angulation stepped. Area with commarginal costellae; shallow radial groove interrupting them. Prominent marginal carina in early growth stages; sharp angulation in later growth stages. Antecarinal space flat, widening posteriorly. Flank with densely spaced sub-commarginal costae.

Occurrence

Las Chilcas, Arroyo El Pedrero and Codo del Blanco (Atuel River region), Mendoza Province. Sinemurian (≈ Bucklandi–Raricostatum biozones): one specimen (Fig. 7.8) from Coroniceras-Arnioceras Biozone?; all other specimens from Orthechioceras-Paltechioceras Biozone (Fig. 3). The species is also recorded from the early Sinemurian of Yukon, Canada (Poulton, Reference Poulton1979), early Sinemurian of Sierra del Álamo, Mexico (Scholz et al., Reference Scholz, Aberhan, González-León, Blodgett and Stanley2008, figs. 10.I, 10.J), and late Sinemurian of Atacama, Chile (Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008).

Description

Very small to small, subtriangular (Fig. 7.4) to subrectangular (Fig. 7.3); orthogyrate to slightly opisthogyrate shell. Escutcheon angulation stepped; escutcheon rarely preserved, smooth (Fig. 7.6). Area, ~1/3–1/4 of general shell surface, with fine commarginal costellae, densely spaced (14–19 costae/cm), separated into two sets by a shallow radial groove; costellae dorsal and ventral to the groove may alternate (Fig. 7.4). Prominent marginal carina at early growth stages (Fig. 7.8); a sharp angulation at late growth stages, though highlighted by tubercles corresponding to the costellae on the area (Fig. 7.4, 7.5). Antecarinal space flat, widening posteriorly; somewhat depressed in some shells (Fig. 7.7), most likely a preservational artifact. Antecarinal space barely invaded by area ornamentation (Fig. 7.4), some costellae continuous with the costae of the flank. Flank with densely spaced subcommarginal costae (8–10 or more costae/cm). Flank costae departing from the antecarinal sulcus at right to slightly acute angles (Fig. 7.2).

Etymology

The Greek prefix eo- (from eos = dawn), implying both the eastern horizon and earliness, and -pacifica for the Paleopacific Ocean: “early Frenguelliella from the Eastern Pacific.”

Materials

MLP 18387a, 18389, 32823, 32834, 32843, 32848, 32850, 32851, 32860, 32864, 32875, 32881, 32891: 10 right valves, 7 left valves, and one specimen with both valves, preserved as composite, external, or internal molds, one specimen (Fig. 7.6, 7.9) with shell fragments preserved.

Figure 7. Frenguelliella eopacifica n. sp., Sinemurian of Argentina and Chile. Scale bar = 10 mm. (1) Paratype, SNGM 561, composite mold of left valve, Sinemurian, Quebrada Pan de Azúcar, Chile; (2) MLP 32864a, right valve, late Sinemurian, Las Chilcas; (3) MLP 32875, composite mold of left valve, late Sinemurian, Las Chilcas; (4) MLP 32848, rubber cast of right valve, late Sinemurian, Las Chilcas; (5) holotype, SNGM 541, external mold of left valve, Sinemurian, Quebrada Pan de Azúcar, near Las Bombas, Atacama, Chile; (6, 9) MLP 32864c, fragmented right valve and internal mold, dorsal and right lateral views, late Sinemurian, Las Chilcas; (7) paratype, MLP 32837, right valve, late Sinemurian, Las Chilcas; (8) MLP 32823, rubber cast of right valve, early Sinemurian, Arroyo El Pedrero.

Measurements

Holotype (SNGM 541): L = 11 mm, H = 8 mm. Paratypes: SNGM 561: L = 17 mm, H = 12 mm, and MLP 32837: L = 19 mm, H = 15 mm. MLP 18387a: L = 20 mm, H = 14 mm; MLP 32851: L = 23 mm, H = 17 mm; MLP 32875: L = 13 mm, H = 9 mm; MLP 32881: L = 19 mm, H = 15 mm.

Remarks

Frenguelliella eopacifica n. sp. differs from other Frenguelliella species by its: (1) small size, (2) smooth escutcheon, (3) relatively large area, and (4) orthogyrate to slightly opisthogyrate shell shape. Material assigned to this new species was often referred to as F. poultoni or F. cf. F. poultoni in the literature. Frenguelliella poultoni Leanza, Reference Leanza1993, is regarded here as a junior synonym of Frenguelliella chubutensis (Feruglio, Reference Feruglio1934) (see Remarks under F. chubutensis). The main differences here recognized between F. eopacifica n. sp. and F. chubutensis are the lack of ornamentation on the escutcheon in F. eopacifica n. sp. together with its smaller size. The species is rather homogeneous with regard to these characters throughout the eastern margin of the Paleopacific, from NW Canada to Neuquén. Frenguelliella eopacifica n. sp. differs from F. inexspectata by its much smaller size and proportionally larger area; also, the type species is strongly opisthogyrate.

Although F. eopacifica n. sp. clearly occurs in Argentina, it is more abundant and better preserved in Chile (Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Aberhan, Reyes and von Hillebrandt2008). Specimens from Chile show a smooth escutcheon (Fig. 7.5), a wide area (~1/3 of general shell surface, Fig. 7.1, 7.5), with a shallow radial groove dorsally displaced. Their marginal carina is slightly protruding at the beginning, developing in later growth stages as a sharp angulation, sometimes highlighted by small tubercles arising from the swelling of each area costella (Fig. 7.5). Area costellae and flank costae are closely spaced (16–24 costellae/cm and 9–12 costae/cm, respectively). Area costellae are usually interrupted by the radial groove, and the ventral and dorsal portions of the costellae may alternate (Fig. 7.5). Shell elongation is variable within the species; interestingly, in longer shells the anterior angle between flank costae and antecarinal space tends to be acute, while in short ones it is almost 90°.

Frenguelliella sp. B described by Poulton (Reference Poulton1979) from the early Sinemurian of Yukon (NW Canada) shows no significant differences with the South American specimens. Material referred to Frenguelliella poultoni was also recorded from lower Sinemurian to lower Pliensbachian beds in Sonora (NW Mexico) by Scholz et al. (Reference Scholz, Aberhan, González-León, Blodgett and Stanley2008). Their figured specimens (Scholz et al., Reference Scholz, Aberhan, González-León, Blodgett and Stanley2008, fig. 10.I, 10.J, from lower Sinemurian of Sierra del Álamo) agree in shape and size with the material here described. Nevertheless, they considered their specimens as “apparently identical” (Scholz et al., Reference Scholz, Aberhan, González-León, Blodgett and Stanley2008, p. 291) to Trigonia cf. T. inexspectata Jaworski, Reference Jaworski1929, which shows significant differences with the material they illustrated (see Remarks under Poultoniella new genus). Since they also included some larger shells up to 45 mm long (Scholz et al., Reference Scholz, Aberhan, González-León, Blodgett and Stanley2008, fig. 11), an unusual size for F. eopacifica n. sp., we only refer the two specimens figured by Scholz et al. (Reference Scholz, Aberhan, González-León, Blodgett and Stanley2008, fig. 10.I, 10.J) to F. eopacifica n. sp. The assignment of the remaining specimens will depend on further study.

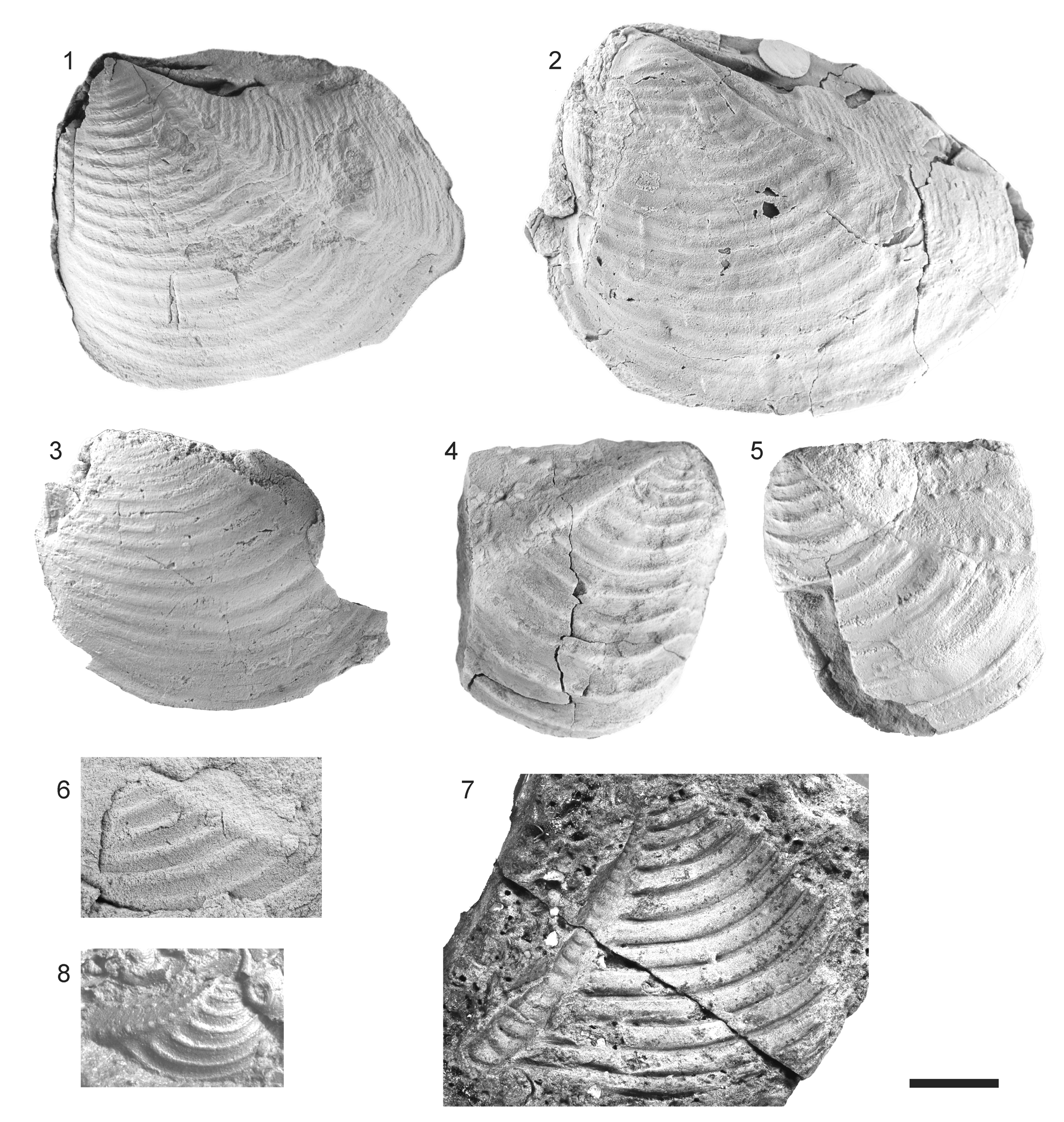

Frenguelliella chubutensis (Feruglio, Reference Feruglio1934)

Figure 8

- p Reference Jaworski1915

Trigonia inexspectata Jaworski, p. 377 (part; not pl. 5, fig. 2).

- p Reference Jaworski1925

Trigonia inexpectata [sic]; Jaworski, p. 79 (part; not pl. 1, fig. 2).

- Reference Jaworski1926a

Trigonia inexspectata var. densecostata Jaworski, p. 396 (not Trigonia densicostata Röder, Reference Röder1882; nec Trigonia densicostata Marshall, Reference Marshall1919).

- Reference Jaworski1926b

Trigonia inexspectata var. densecostata; Jaworski, p. 180.

- Reference Weaver1931

Trigonia inexspectata var. densecostata; Weaver, p. 233.

- *v Reference Feruglio1934

Trigonia chubutensis Feruglio, p. 34, pl. 4, figs. 9, 11.

- Reference Feruglio1934

Trigonia sp.; Feruglio, p. 36, pl. 4, figs. 10a, b.

- Reference Lambert1944

Trigonia tapiai Lambert, p. 358, pl. 13, fig. 1.

- Reference Pérez and Reyes1977

Trigonia (Frenguelliella) tapiai; Pérez and Reyes, p. 12, pl. 1, fig. 2. [reproduced from Lambert, Reference Lambert1944]

- Reference Volkheimer, Manceñido and Damborenea1978b

Trigonia (Frenguelliella) sp.; Volkheimer et al., p. 212 (table 2).

- v Reference von Hillebrandt and Zeil1980

Frenguelliella tapiai; Hillebrandt, pl. 2, figs. 8a, b.

- v Reference Cuerda, Schauer and Sunesen1982

Frenguelliella tapiai; Cuerda et al., p. 331.

- v Reference Leanza, Garate-Zubillaga and Volkheimer1987

Frenguelliella tapiai; Leanza and Garate-Zubillaga, p. 210, pl. 1, fig. 5.

- v Reference Leanza and Blasco1990

Frenguelliella tapiai; Leanza and Blasco, p. 163.

- v Reference Damborenea and Manceñido1992

Frenguelliella chubutensis; Damborenea et al., pl. 116, fig. 17.

- v Reference Damborenea and Manceñido1992

Frenguelliella tapiai; Damborenea et al., pl. 116, fig. 18.

- Reference Leanza1993

Frenguelliella tapiai; Leanza, p. 26, pl. 1, fig. 8.

- v Reference Leanza1993

Frenguelliella poultoni Leanza, p. 26, pl. 2, figs. 3–6.

- Reference Pérez and Reyes1997

Frenguelliella tapiai; Pérez and Reyes, p. 574.

- v Reference Pérez and Reyes2008

Frenguelliella tapiai; Pérez and Reyes in Pérez et al., p. 70, pl. 5, figs. 1, 3, 4, 9–13.

- v Reference Riccardi, Damborenea, Manceñido, Leanza, Leanza, Arregui, Carbone, Danieli and Vallés2011

Frenguelliella tapiai; Riccardi et al., fig. 7.14.

- v Reference Pagani, Manceñido, Damborenea and Ferrari2012

Frenguelliella sp.; Pagani et al., p. 413, fig. 3c.

Type materials

Lectotype: MLP 3729. Riccardi and Martín (Reference Riccardi and Martín1987, p. 61) listed this specimen as “Holotipo”; yet, since Feruglio (Reference Feruglio1934, p. 34, pl. 4, figs. 9, 11) had established the taxon based on two specimens, their action may be regarded as fixation of lectotype by inference of holotype (ICZN, 1999, Art. 74.6.1.2). The specimen is a composite mold of a right valve, collected by Piatnizky in the Genoa River region (Chubut Province), “lote 20” (most likely the locality now known as Aguada Loca). This is undoubtedly one of Feruglio's syntypes, illustrated by Feruglio (Reference Feruglio1934, pl. 4, fig. 11), by Damborenea et al. (Reference Damborenea, Polubotko, Sey, Paraketsov and Westermann1992, pl. 116, fig. 17), and here (Fig. 8.2). The whereabouts of Feruglio's second specimen (paralectotype) is unknown.

Holotype of Trigonia inexspectata var. densecostata Jaworski

An external mold of a right valve at the Institute of Geosciences, Paleontology Section, Bonn (Germany), IGPB-Jaworski-74, from Cerro Puchenque, Mendoza Province (Figure 8.1).

Type of Trigonia tapiai Lambert

DNGM 43-109, from a bend of arroyo Pichi Picún Leufú, east of Cerro Chachil, Neuquén Province, figured by Lambert (Reference Lambert1944, pl. 13, fig. 1).

Holotype of Frenguelliella poultoni Leanza

MOZ-PI 5315, from Ñireco, east of Cerro Chachil, Neuquén, figured by Leanza (Reference Leanza1993, pl. 2, fig. 3) and here (Fig. 8.3).

Diagnosis

Ovate-subquadrangular to ovate-subrectangular shell, slightly opisthogyrate to orthogyrate. Escutcheon with commarginal costellae crossing from the area. Area wide, with costellae densely arranged, with a submedian radial groove dorsally displaced and sometimes interrupting the costellae. Flank with densely but evenly spaced fine and sharp sub-commarginal costae (up to 20–25 in adult shells), fewer than area costellae (usually about half). Escutcheon angulation stepped; prominent marginal carina at early growth stages, sharp angulation at later ones.

Occurrence

Arroyo La Laguna (Los Patos region) San Juan Province; La Horqueta, Codo del Blanco, Las Chilcas, Quebrada Los Caballos, Puesto Araya, Cerro La Brea (Atuel River region), Arroyo Peuquenes, Arroyo Portezuelo Ancho (Las Leñas/Valle Hermoso region), Arroyo Serrucho, Cerro Puchenque (west of Malargüe region), Mendoza Province; Estación Rajapalo (Cordillera del Viento region), Ñireco, Rahue-Aluminé (Cuerda et al., Reference Cuerda, Schauer and Sunesen1982), Lonqueo (Central Neuquén region), Estancia Santa Isabel (Piedra Pintada region), Neuquén Province; Puesto Peña (central Chubut region), Lomas de Betancourt, Aguada Loca, Nueva Lubecka (Genoa River region), Chubut Province. Early Pliensbachian to late Pliensbachian (M. chilcaense–F. disciforme biozones [≈ Jamesoni–Spinatum biozones]) (Fig. 3), early Toarcian? (Tenuicostatum Biozone).

Description

Small to medium-sized, subquadrangular (Fig. 8.18, 8.19) to subrectangular (Fig. 8.2, 8.15, 8.20) shell. Slightly opisthogyrate to orthogyrate, with umbo anteriorly located. Escutcheon margin slightly convex (Fig. 8.7, 8.19). Area margin long, gently convex or almost straight (Fig. 8.14, 8.19), ventral portion sometimes projected posteriorly (Fig. 8.10, 8.12). Area margin generating right to slightly obtuse angles with escutcheon and ventral margins (Fig. 8.1, 8.2, 8.15, 8.19, 8.20). Ventral margin convex, at a slightly obtuse angle with anterior convex margin. Escutcheon with commarginal costellae crossing from the area (sometimes two area costellae joining into one escutcheon costella; Fig. 8.22); escutcheon margin slightly raised. Escutcheon angulation stepped. Area wide (~1/3–2/5 of general shell surface), with barely impressed radial groove; ventral part slightly wider. Area with fine commarginal costellae, very densely spaced (7–20 costellae/cm; most values 10–16 costellae/cm); sometimes interrupted by the radial groove; dorsal and ventral costellae often alternating (Fig. 8.22); ventral costellae frequently more numerous. Prominent marginal carina at initial growth stages, later as a sharp angulation. Area costellae slightly swollen over the angulations, and most conspicuously tending to bend posteriorly, rendering a pustulose appearance to the marginal angulation (Fig. 8.5, 8.7, 8.9, 8.21, 8.22), which even resembles a prominent carina (Fig. 8.7, 8.10). Antecarinal space widening posteriorly, frequently with flank costae conspicuously weakening; posterior portion usually invaded by area costellae (especially in later growth stages). Costae occasionally deviating when crossing the antecarinal space (Fig. 8.10). Antecarinal space slightly concave in early growth stages, flat in later stages, yet forming a slight angle with the flank (some molds with truly concave sulcus; Fig. 8.10, 8.12, 8.13). Flank with thin, densely spaced (5–15 costae/cm; most values 6–10 costae/cm), sub-commarginal costae (Fig. 8.7, 8.9). Costae sometimes with a rounded posterior bend (Fig. 8.6); most frequently, anterior angle between costa and antecarinal space nearly right (Fig. 8.3, 8.6, 8.12) to slightly acute (Fig. 8.2, 8.5, 8.15, 8.20).