Introduction

On 16 April 1973, Antonio Monteforte, a photojournalist from the Italian news agency ANSA, took a photograph that would later be described as ‘live death’. It showed the burnt corpse of 22-year-old Virgilio Mattei at his bedroom window; obscured from view was the body of his younger brother Stefano, aged 10, who died clutching his legs. The image was published in the daily paper Il Messaggero and subsequently reprinted in other Italian media. Not only did it show the violence of the acts of terrorism that characterised Italy's anni di piombo (Years of Lead), it also captured what set apart the Rogo di Primavalle (the Primavalle Pyre)Footnote 1 from the acts of violence that preceded it: the domestic setting and the child victim.

Stefano and Virgilio Mattei were killed in an arson attack on the family home in Primavalle, Rome, perpetrated by three members of the extra-parliamentary extreme left group Potere Operaio (Workers’ Power). Their father, Mario Mattei, was the leader of the local branch of the neofascist party Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI). He lived in the third-floor flat of a block on via Bernardo da Bibbiena with his wife, Anna, and six children. Virgilio, the eldest, was a member of the Volontari Nazionali (National Volunteers), the militant arm of the MSI that made its first public appearance at the funeral of Fascist marshal Rodolfo Graziani in 1955. Mario, his wife Anna, and their two youngest children, Antonella, 9, and Giampaolo, 4, escaped the fire in the flat. His daughters Silvia, 19, and Lucia, 15, escaped by climbing from a window to the balcony below. Virgilio, 22, and Stefano, 10, burned to death at their window in front of crowds below. Their bodies remained at the window for much of the day. An estimated 5,000 people gathered in the gardens below after the attack: an article in Il Messaggero on 17 April quoted one of them describing a local priest's blessing of the two corpses, which he referred to as ‘like a coal statue’ (di Dio Reference di Dio1973, 5).

From the late 1960s to 1980, Italy lived through a long decade of political violence. More than 12,000 instances of political violence were recorded, primarily taking place in the streets, on public transport or in public buildings, putting the period ‘among the most dramatic in the history of the Italian nation’ (Hajek Reference Hajek2012, 289). Though the Piazza Fontana bombing of 1969 may mark the start of the period in Italian collective memory, it was not the first instance of terrorism that year; its ‘exceptional nature’ may have eclipsed two smaller explosions that occurred in 1969, but it was in fact part of a wider series of attacks (Cento Bull and Cooke Reference Cento Bull and Cooke2013, 2). By 1969, the so-called ‘strategy of tension’ had emerged as a feature of Italian political life. This term, which first appeared in the British newspaper The Observer a few days before the Piazza Fontana massacre (Hajek Reference Hajek2010, 203–204), noted the collusion between neofascists and the Italian state, which worked together to commit acts that could be framed as the work of the left in order ‘to demonstrate the validity of the “might-is-right” thesis, and to point to the need for repressive action on the part of the state to control civil unrest’ (Weinberg and Eubank Reference Weinberg and Eubank1987, 59).

This article will not reconstruct the events of 16 April 1973, nor will it question the subsequent judicial failures, though both elements have contributed to the ‘divided memory’ (Foot Reference Foot2009) of the tragedy. Instead, I analyse how the Mattei brothers’ deaths were immediately cast as political sacrifice by more radical factions within the MSI and examine the later instrumentalisation of that narrative of martyrdom by present-day neofascist groups. I will argue that in 1973 three elements combined to confine commemoration of the attack to far-right communities: firstly, a campaign of misinformation that blamed internal divisions within the MSI for the attack; secondly, the failure of the first trial to deliver justice; and finally, the immediate patronage of memory by the MSI. Motivated by a sense of injustice in the face of these incorrect dominant narratives relating to the Rogo, the MSI quickly constructed a politically expedient ‘counter-memory’ (Foucault cited in Bouchard, Reference Bouchard1980) of events. Foucault defines counter-memory as ‘a transformation of history into a totally different form of time’ (1980, 160), which challenges the understanding of historical consciousness as ‘neutral, devoid of passions, and committed solely to truth’ (1980, 162). It is disruptive and questions the very possibility of ‘history as knowledge’ (1980, 160), showing instead ‘knowledge as perspective’ (1980, 156). This article examines the construction of this counter-memory in 1973 as a means of drawing attention to the suffering inflicted on the party by those on the far left, following the recent implication of party members in the killing of a police officer.

The second part of this article addresses the ongoing instrumentalisation of memory by neofascist groups since the admission of guilt by one of the perpetrators in 2005. Despite this confession and the work of the victims’ surviving brother, Giampaolo Mattei, to work alongside institutions to integrate his brothers’ memory within wider narratives of victimhood relating to the Years of Lead, contemporary neofascist groups continue to claim the brothers’ memory as part of their heritage, tying commemoration to far-right identity. The commemoration ceremony they organise is highly performative, and incites emotions of anger and reverence among participants, whose collective identity is repeatedly staged and historicised through Fascist symbols and rituals. Their approach to memory reflects the antagonistic mode of remembering examined by scholars including Cento Bull and Hansen (Reference Cento Bull and Hansen2016), Erll (Reference Erll, Lamberti and Fortunati2011, Reference Erll2009) and Leerssen (Reference Leerssen and McBride2001). This mode of remembering is exclusionary and divisive; it ‘privileges emotions in order to cement a sense of belonging to a particularistic community, focusing on the suffering inflicted by the “evil” enemies upon this same community’ (Cento Bull and Hansen Reference Cento Bull and Hansen2016, 398). The final part of this article will examine the memorial initiatives organised by Giampaolo Mattei, who seeks to prevent any further commemoration of his brothers within the antagonistic mode of remembering. I will begin with an overview of Primavalle and the socio-political tensions that culminated in the attack.

Unrest in Rome's poorest suburb

Located outside Rome's old city walls, Primavalle was one of the suburbs built by the Fascist administration to rehouse those who had been displaced as a result of demolition in the city centre carried out on Mussolini's orders. The 91-acre suburb was inaugurated in 1939, but the programme of social housing was curtailed by the Second World War; just 515 of the planned 1,498 housing units were ever constructed, the promised services (such as shops and laundrettes) were never delivered, and public transport was left undeveloped (Trabalzi Reference Trabalzi2010, 138). According to an exhibition on the history of Primavalle, in 1950 many of the social housing units had neither running water nor sanitation, with only 25 toilets available for the population of 5,000 (Mostra sul Quartiere di Primavalle, 2007).

By 1973, Primavalle was the poorest of the Roman suburbs and its inhabitants may even have had the lowest income per capita across Italy (Telese Reference Telese2006, 66). It was a predominantly left-wing community, though some inhabitants remained loyal to the MSI. Founded in 1946 for those who still identified with fascist values, the MSI had a dual aim: to revive and rethink fascism, and fight communism. It was politically, ideologically and geographically divided from the outset (Ignazi Reference Ignazi, Jones and Pasquino2015, 213). On the one hand, a group concentrated predominantly in the north of Italy (which had experienced the Italian Social Republic) wanted to precipitate a return to Fascism. The second group – the party's primary electoral base – favoured a more conservative approach. Narratives relating to this radical-moderate split would come to play an important part in the attribution of blame for the Primavalle Arson.

The early 1970s was an important era for the MSI. After a period of moderate leadership under Augusto de Marsanich and Arturo Michelini, the radical branch of the party was reintegrated. When Giorgio Almirante returned to the party's helm after the death of Michelini in 1969, he strengthened ties with more militant groups (even granting a seat on the central committee to Pino Rauti, who was suspected of involvement in the Piazza Fontana massacre). The party achieved its highest ever proportion of votes in the 1972 general election, taking 8.7 per cent – an ‘electoral breakthrough’ (Mammone Reference Mammone2015, 141). That same year, violent clashes took place in Primavalle between the police and students belonging to left-wing extra-parliamentary groups that had occupied the Istituto Tecnico Genovesi the day before a planned demonstration to mark the anniversary of Piazza Fontana. Furthermore, in January 1973, a rudimentary explosive device was set off in the local MSI headquarters four days before the party conference in Rome. Tensions came to a head in the Rogo di Primavalle.

On 18 April, Achille Lollo, Manlio Grillo and Mario Clavo, members of the extreme left-wing group Potere Operaio, were arrested on suspicion of manslaughter. Influential left-wing intellectuals including Franca Rame and Alberto Moravia publicly protested the innocence of the suspects, and Il Messaggero launched a campaign in their defence (Diana Perrone, daughter of the owner of the paper, was later discovered to have given a false alibi for Clavo, with whom she shared a flat). Rumours began to circulate that MSI members were responsible for the arson, which was the result of an internal power struggle between members with different ideological stances. More moderate members who, like Mattei, supported Almirante, were rumoured to have set fire to the flat in order to frame the extremist historic militant groups within the MSI. The rumour emerged immediately; the day after the arson, the newspaper Lotta Continua (Continuous Struggle, published by the eponymous extreme left group) suggested extreme MSI members had set fire to the Mattei family home in order to frame the opposing faction. The headline read: ‘Fascist provocation beyond all bounds: now they are murdering their own children!’ (Lotta Continua 1973).

A book entitled Primavalle, incendio a porte chiuse concentrated on these rumours of ‘internal divisions’ within the MSI as the primary motivation for the attack. It was published with a bellyband that read: ‘Achille Lollo is innocent. HERE IS THE PROOF’. The book stated:

There is enough evidence to state that the fascist headquarters in Primavalle has been, for some time now, one of the least tranquil, and in fact torn apart by ever-increasing internal struggles. There is also enough to say that some of these attacks, truly very ‘strange’, were nothing more than the final act of violent internal divisions. (Potere Operaio 1974, 32)

The first trial began on 24 February 1975; the MSI initially tried to act as plaintiff, but this was rejected by the courts. On 5 June 1975, Lollo, Clavo and Grillo were acquitted on the grounds of insufficient evidence. The trial prompted violent political protests, one of which led to the death of a right-wing Greek student, Mikis Mantakas, who was shot outside the MSI headquarters in via Ottaviano, Rome.Footnote 2 Lollo, Grillo and Clavo would later be judged guilty in absentia of arson and involuntary manslaughter during the second trial, which concluded in December 1986 when the three were sentenced to 18 years’ imprisonment. There were no ambiguities; the defendants had been found guilty of having started the fire that killed Virgilio and Stefano. However, the courts found that they did not intend to kill. Having fled abroad, none of the three spent any time in jail. In 2005 the sentence lapsed, restoring freedom to the convicted. Had the original charge been one of omicidio di strage (mass murder), this could not have happened. Certain of his freedom while living in Brazil (where he held political refugee status), and safe in the knowledge that he could no longer be prosecuted for the arson, Lollo gave an interview to Corriere della Sera in 2005 in which he admitted responsibility for the tragedy and gave the names of five others involved (Cotroneo Reference Cotroneo2005, 6).

Casting death as political sacrifice

On 18 April 1973, crowds gathered outside the local headquarters of the MSI on via Alessandria, where local councillors, right-wing deputies and the public paid their respects to the brothers during a vigil. At 16.30, the two caskets were carried out of the building by the MSI youth division, and were met by crowds holding tricolour wreaths, white flowers and black flags, many of whom stretched out their arms in the Roman salute. The funeral procession began its slow pace; ahead of the caskets walked Giulio Caradonna, a MSI deputy and a former adherent of Mussolini's Italian Social Republic known for his violent past; in 1995, he was described as ‘l'ex picchiatore per antonomasia’ – the ultimate batterer – in Corriere della Sera, referring to his participation in National Volunteers brawls (Fertilio Reference Fertilio1995, 31). With the boys’ father still in hospital, Giorgio Almirante, party leader and founder, walked beside their mother. Gianfranco Fini and Maurizio Gasparri are said to have met for the first time that day; both went on to be seminal figures in the history of the MSI and its successor party, Alleanza Nazionale (National Alliance) (Garibaldi Reference Garibaldi2010, 10). The funeral signified that the right, too, was under attack, and marked an important part of the early construction of a counter-memory to challenge the dominant narrative that attributed the arson to internal party divisions. An article published by La Stampa the following day described ‘a huge presence from the top of the MSI’ (Carbone Reference Carbone1973a, 2). Their participation revealed an acute awareness of the political capital of martyrdom at a time when the party had been discredited.

Five days before, on 12 April, an explosion during an MSI demonstration against ‘red violence’ in Milan had killed policeman Antonio Marino. The Milanese prefecture had initially authorised the demonstration but had imposed a last-minute ban on all public demonstrations (with the exception of the Liberation Day ceremonies on 25 April) for reasons of public order. Members of extreme right-wing groups including Ordine Nuovo (New Order) and Avanguardia Nazionale (National Vanguard) gathered on 12 April regardless, and marched towards the police station to protest the ban. Clashes between the police and demonstrators ensued; protestors threw two grenades, one of which killed Marino immediately. The next day, three workers’ unions – CGIL, CSIL and UIL – declared a strike in protest against ‘fascist provocation’ and several political groups and parties, including the student movement and the Italian Socialist Party, issued statements condemning the violence (Corriere della Sera 1973a, 9). The policeman's death prompted sustained debates in the media regarding the MSI's links to violent extra-parliamentary militants. Indeed, the event was named ‘the march on Milan’ by Corriere della Sera (1973c, 1) – a clear reference to Mussolini's march on Rome. Journalists questioned to what extent Almirante's party had left behind its Fascist roots (see Montanelli Reference Montanelli1973, 2; Piazzesi Reference Piazzesi1973c, 1) in favour of a moderate conservatism.

Attempting to distance the party from the killing, the MSI offered a financial reward to anyone able to identify the culprit. Police investigators quickly focused on two demonstrators from Reggio Calabria (the same city as senator Ciccio Franco who had been due to speak at the event) who were thought to have travelled to Milan with the senator – a claim he denied (Corriere della Sera 1973b, 2). On 13 April, Sandro Pertini, president of the Chamber of Deputies, denounced MSI violence in parliament and compared it with the Fascist squadrismo of the 1920s (Melani Reference Melani1973, 1). The violent demonstration had cast the party in a negative light, prompting comparisons between Mussolini and Almirante who, at that point, was under investigation for ‘reconstitution of the Fascist party’ (Piazzesi Reference Piazzesi1973a, 1). By 16 April, the names of those involved in the grenade attack had been published by the media; some national newspapers published the report of the Primavalle fire alongside the story revealing the names of Marino's killers. All four were fully paid-up members of the MSI. On 19 April, Almirante called a press conference in the MSI headquarters in response to ‘the gravity of this moment’. According to La Stampa journalist Fabrizio Carbone, he spent just three minutes discussing the Primavalle attack (in response to a question), dedicating an hour to discussion of Marino's death and denying demonstrators’ membership of the MSI (Carbone Reference Carbone1973b, 2).

The Mattei funeral began in the nearby Chiesa dei Sette Santi Fondatori, which was decorated by flowers sent by the President of the Republic, Giovanni Leone, government members and the local council. The Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Villot sent a message on behalf of the Pope, which was read to mourners. The ceremony concluded with an emotive speech given by Almirante, standing on the exterior steps of the church. He focused on the notion of sacrifice in a speech that marked the first public application of the term ‘martyrdom’ to the deaths:

Virgilio e Stefano Mattei. You are the dearest Rome to us, the humble and high Rome, the proletarian and national Rome of the working-class suburbs; from the sweet suburbs that clasp the sacred and imperial city like you, Stefano, clasped Virgilio: so as not to suffocate, so as not to die, to breathe. Primavalle has become the real front line, as we used to say years ago, when our branch was born. The front line of martyrdom is always the front line of redemption in the name of civilisation. (Mattei Reference Mattei2008, 23).

Almirante's words echoed the nostalgia for empire and the revered status of the city of Rome that had defined much rhetoric of the Fascist period. ‘From the pyre of hatred the flame of martyrdom, the light of justice,’ Almirante continued, emphasising the concepts of sacrifice and rebirth typical of the classic, Christian martyr paradigm. His words were interrupted as a group of motorcyclists drove into the piazza, throwing bottles at mourners (Carbone Reference Carbone1973a, 2).

Given the persistent discussion of the MSI's links to extra-parliamentary violence, this language and iconography of martyrdom was an important component in the construction of a politically expedient counter-memory. The words sent by Cardinal Villot on behalf of the Pope further strengthened the martyrological narrative, which included explicit references to the boys’ martyrdom made by Almirante and the formalised rituals of mourning enacted by the MSI community. Mourning was neither private nor confined to the family. Rather, through a combination of rituals, a heavy political presence and the iconography of the right, the funeral positioned the boys not as private victims, but as sacrificial martyrs of the party. This counter-memory emphasised the suffering of the party and challenged the dominant, incorrect narrative that attributed the arson to factions within the MSI. Today, we can see the legacy of this sense of injustice upon which the counter-memory was founded; in the period leading up to the 2018 grassroots neofascist march organised in Primavalle, several posters were affixed to buildings in the local area declaring ‘45 anni di verità negata’ (‘45 years of truth denied’) – an incorrect assertion, given the results of the second trial when the three perpetrators were judged guilty of manslaughter and Lollo's confession in 2005.

The next section will address one example of the inclusion of the boys’ deaths within historic Fascist martyrology, which draws a line of continuity from the ‘cult of the martyrs’ that originated under Mussolini's regime – transforming political action into a quasi-religious act (Foot Reference Foot2009, 56) – to the present day.

Fascist martyr cults

Since the initial incorporation of the Mattei brothers’ deaths into the martyrology of the MSI, the rituals and rhetoric of martyrdom have been constant in far-right commemoration of the brothers. However, although Virgilio Mattei was involved in extreme right politics, he did not die in the name of belief nor in a public space during a political struggle. Ten-year old Stefano cannot be said to have lived in the name of politics. Why, then, has the term ‘martyr’ been so consistently used to describe the brothers?

Martyrdom creates binaries – the ‘good’ victim, and the ‘evil’ perpetrator. As Portelli argues, the suggestion of sacrifice indicates the presence of a sacrificer; the term means the dead share the spotlight with the perpetrator (Reference Portelli2007, 196). Commemoration of the boys as martyrs by the far right was established immediately after their deaths by the MSI and reasserted the ‘good’ victim and ‘evil’ perpetrator binary that had been undermined by the killing of a policeman by individuals associated with the MSI some days before. The subsequent failure of the 1975 trial sustained the narrative of suffering and sacrifice so inherent to martyrdom that Almirante had expressed during the funeral. The brothers’ status as martyrs for the far right was constructed in the immediate aftermath of the attack; after the 1995 dissolution of the MSI, they would be commemorated by neofascist groups within a broader tradition of fascist martyrs, building on the cult of Fascist martyrs that originated under Mussolini's regime, as the following example shows.

Designed on the orders of the National Fascist Party, the Mausoleum of the Fascist Martyrs was unveiled in Rome's monumental Verano cemetery on 23 March 1933 to coincide with the Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution. Its construction was significant in the development of Fascism's glorification of its dead, marking the transition of shrines to the Fascist dead – or martyrs, as they called them – out of the church and into public space (Staderini Reference Staderini2008). It was built to honour those who had sacrificed their lives during Fascism's rise to power in an attempt to create some historical memory of a relatively new movement. The mausoleum had space for 12 martyrs, but since only four Romans had died in the battles of 1920–1922 the remit had to be widened to include those who died later as a result of injuries sustained during the rise to power, or those killed many years later abroad.

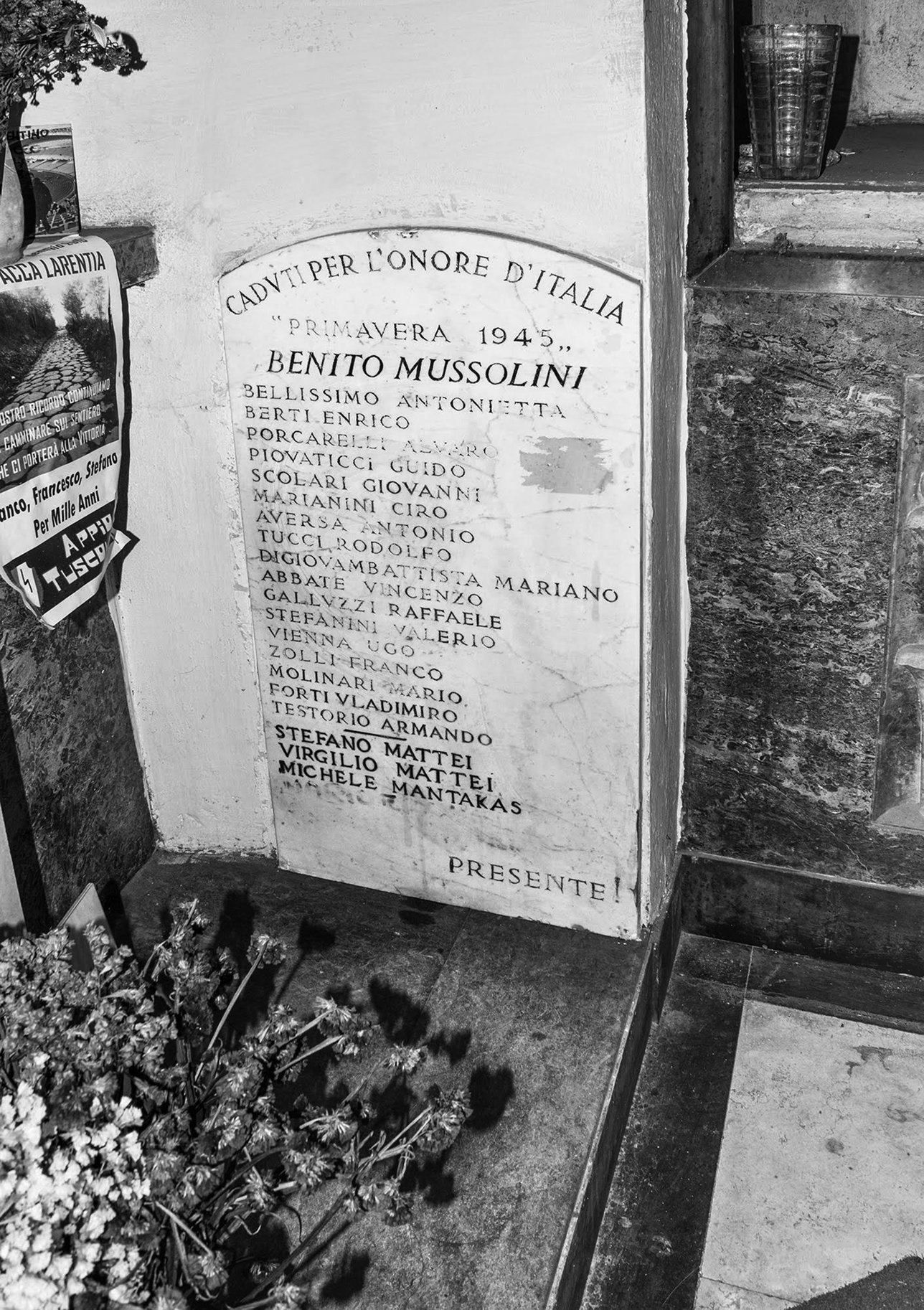

Inside is a dark marble altar with a torch, one of Fascism's many symbols, etched into it (Fig. 1). Above the altar, a cross-shaped window lets in a little light and underneath there is an inscription ‘to the fascist martyrs’, linking the regime with religion through iconography and the language of sacrifice. Beside the altar, at ground level, is a headstone-shaped plaque dedicated to the ‘fallen for the honour of Italy’ (Fig. 2). The second line reads ‘Primavera 1945’, a reference to the period of Italy's liberation from Fascism and Nazi occupation, which led to the murder of many Fascists at the hands of partisans. At the head of the list of the fallen is Benito Mussolini, whose name is written in large, bold letters. A further 17 names of fallen Blackshirts and Fascist supporters are listed below.

Fig. 1. Inside the Mausoleum of the Fascist Martyrs (author’s own image).

Fig. 2. The plaque dedicated to ‘the fallen for the honour of Italy’ (author’s own image).

At the foot of the plaque, beneath a line that seems to demarcate a new temporal period, are the names Stefano Mattei, Virgilio Mattei, and Michele Mantakas (the aforementioned Greek student killed in the clashes that took place during the Primavalle trial). The final word on the plaque – PRESENTE! – is closely tied to Fascist martyrs; Foot highlights its ‘obsessive use’ on monuments dedicated to the fascist dead across Italy (2009, 56). The appearance of the Mattei brothers’ names alongside Mussolini and his squadristi on a commemorative plaque within a mausoleum built to honour those who died during Fascism's rise to power shows an attempt to frame the brothers as two of many Fascist martyrs. No other names from after 1945 feature permanently in the mausoleum.

It is not known for certain who added the Mattei brothers’ names to the plaque. When I asked the Mattei family about it in 2018, they were unaware of its existence and unhappy about the inclusion of the boys’ names within the mausoleum. Giampaolo Mattei has since made further enquiries, and has been told by an institutional figure linked to a far-right group in Rome loyal to Fabio Rampelli – current vice president of the Chamber of Deputies and co-founder of Fratelli d'Italia, former Youth Front militant and ex-member of the MSI – that they added the boys’ names to the plaque. The group in question participates in an annual ceremony held at the Verano cemetery to honour the memory of important ‘sons of Italy’. The ceremony involves a procession through the cemetery, stopping to honour those deemed part of Italy's right-wing heritage. The Mausoleum of the Fascist Martyrs is part of the ceremony.

The inclusion of Stefano, Virgilio and Michele Mantakas – whose real name, Mikis, has been Italianised to blend into the list of Italian martyrs – is evidence of the continued centrality of martyrology in the construction of far-right political identity. It shows an attempt to historicise the Mattei brothers’ deaths within broader fascist martyrology, and the ongoing claiming of their memory by groups associated with the radical, rather than conservative, right as part of their heritage. Their memory has been included in order to draw continuity between the Fascist memory of the 1920s, deaths during Italy's liberation, the right-wing dead of the 1970s and the radical right today.

The next section addresses the possessiveness that contemporary neofascist groups show towards the memory of the Mattei brothers, and the antagonistic mode of remembering they adopt in commemoration. Braunstein's theory of ‘possessive memory’ (Reference Braunstein1997), as examined by Hajek in relation to the left's hold on the memory of 1968 (Reference Hajek2013, 51), can be applied to describe the relationship of extra-parliamentary far-right groups to the memory of the Primavalle Arson, despite the fact they had no involvement in the events of 1973. It is my contention that since the dissolution of the MSI in 1995, neofascist groups have claimed the memory of the brothers as their own because of the initial narrative that presented them as sacrificial martyrs of the party. Analysis of commemoration ceremonies is particularly relevant in studies of contested events like the Primavalle Arson, since public enactments of meaning – which require a level of interpretation – show the contemporary significance of the tragedy for different, and often competing, groups.

Performing martyrological heritage

In the years following the tragedy, commemoration ceremonies were organised by New Order and members of the local MSI. In the 1990s, however, groups of younger neofascists who had not lived through the political violence of the 1970s began to commemorate the brothers. The 1995 ceremony was unusually violent and caught the attention of several newspapers as a result. The date is important; it took place the year after significant changes in Italy's political spectrum. In 1994 the MSI's debate around its heritage reached a climax as the party adopted a new name – Alleanza Nazionale (AN) – and distanced itself from Fascism. This led to a split headed by Pino Rauti, who protested against what he deemed a betrayal. AN was officially launched in January 1995 at its inaugural convention in Fiuggi (a development that became known as the ‘svolta di Fiuggi’); the official congress documents presented ‘an alternative genealogy’ (Tarchi Reference Tarchi2003, 140) for the party, emphasising democratic right-wing values that predated Fascism. The party enjoyed great success in the 1996 parliamentary elections, taking 15.7 per cent of the vote, up 2.2 per cent on the previous election (Ignazi Reference Ignazi, Jones and Pasquino2015, 222).

On 16 April 1995, around a hundred young neofascists gathered in Primavalle. The majority wore black bomber jackets, and several had their faces covered and carried weapons including knives and pickaxes (Grignetti Reference Grignetti1995, 13). Along with the flowers they intended to lay beneath the former Mattei flat, many carried large bats (Bongini Reference Bongini1995, 15), which they used to smash parked cars and intimidate the public (Grignetti Reference Grignetti1995, 13). Fearing clashes with Break Out, a nearby left-wing social centre, local residents called the police. Three arrests were made, and five policemen were injured. According to the police, while in custody each detainee made reference to the dissolved group Movimento Politico Occidentale (Western Political Movement) – the political strand of a radical right skinhead movement comprised of gangs that extol violence (Ferraresi Reference Ferraresi1996, 201). Fascist symbolism had featured heavily during the commemorative march; skinheads dressed in black enacted the Roman salute and carried flags bearing Fascist iconography (Grignetti Reference Grignetti1995, 13). As institutional politics shifted away from the far right with the birth of AN, extreme right radicals disappointed by the perceived dissolution of Italy's Fascist heritage in institutional politics reasserted their ideological beliefs by incorporating the rituals and iconography of Fascism into commemoration of the Matteis.

Violence featured throughout the commemorative ceremonies of the late 1990s. The event was organised by groups including the youth division of AN, the far-right political party Forza Nuova (New Force) and the far-right coalition Alternativa Sociale (Social Alternative), established by Mussolini's granddaughter, Alessandra, in 2004. More recently, the task has fallen not to an official party or coalition, but to Roma Nord-Magnitudo Italia, a neofascist militant group made up primarily of young people. The group is based in the former MSI headquarters in via Assarotti, Monte Mario.

The group meets in Piazza Clemente XI in Primavalle in the early evening of 16 April. Accompanied by police, they walk through Primavalle behind a wide banner decorated with the Celtic cross that reads: honour to the Mattei brothers. As they walk towards via Bibbiena, the group chants, and many participants perform the Fascist salute. Shouts include ‘Contro il sistema, la gioventù si scaglia, boia chi molla, è il grido di battaglia!’ (‘Youth lashes out against the system, death to traitors is our battle cry!’). This slogan was first used by the squadristi and then the Fascist military of the Italian Social Republic, then, in the 1970s, by neofascist groups and the football ultràs of the extreme right as ideological (and generational) conflict shifted into sports arenas (Testa and Armstrong Reference Testa and Armstrong2008, 474–475). In keeping with other protests, the chant follows the typical template of 3/3/7 syllables, highlighted by Portelli, who writes of the ‘emotional community’ formed at a rally or march, ‘which moves and speaks collectively, and generates specific oral forms in order to synchronize these actions’ (Reference Portelli1991, 177). The chant is one example of the way the ceremony binds collective identity through emotion – a typical feature of the antagonistic mode of remembering. The orality of the event contrasts with the quieter institutional commemoration ceremony that takes place earlier in the day, which is addressed in the final section of this article.

In her study of the changing role of violence in the construction of neofascist culture within far-right youth divisions (defined as such by their respective parent organisations) in Italy, Dechezelles analyses the impact of the dissolution of the MSI and the subsequent shift towards moderate conservatism required of its successor party, AN, following its participation in the institutions of government (2011). She argues that the institutionalisation of AN delegitimised any recourse to violent political action; instead, neofascist youths were to pay their respects to the glorious dead who came before them by honouring their memory (2011, 105). This created a hierarchical structure, whereby youth groups repeatedly showed their loyalty and obedience to their fallen predecessors through commemoration, creating a ‘macabre fascination’ with lives sacrificed that creates a permanent connection between young militants and their heroic predecessors; consequently, nostalgia is one of the most important units of the group's emotional economy (Dechezelles Reference Dechezelles2011, 107). Internally, these stories act as an important foundation of the group's collective memory, mirroring Fascism's construction of ‘a myth of its own past’ through the cult of the Fascist martyrs.Footnote 3 These stories of martyrdom are a foundation of collective identity, but they also serve as a reminder of the group's suffering inflicted by the barbarity of their adversaries (Dechezelles Reference Dechezelles2011, 109).

Throughout the march, slogans defaming the left are shouted, which underline the barbarity of the perpetrators. Upon reaching the flat in via Bibbiena, a few words are spoken by the group leader about the ‘cowardly assassins’ of Stefano and Virgilio to mourners, who stand to attention in the organised lines of a military formation. A member of the group then walks through the gardens below the window at which Virgilio died to leave a wreath. Upon his return, the leader of the group shouts ‘Comrades, Stefano and Virgilio Mattei!’ and the group responds with ‘presenti!’ three times, each shout accompanied by the Roman salute. The group is then told to stand down. Drawing on the rituals and symbolism of the Fascist period, the group reaffirms the value of sacrifice for the far right.

An exclusionary, antagonistic mode of remembering is promoted by contemporary neofascist memory choreographers, with the effect of reinforcing political binaries. The lines between ‘us’ and ‘them’ typical of the antagonistic mode of remembering are clear here. According to Cento Bull and Hansen:

Across Europe, populist nationalist and/or radical right movements have developed counter-memories in a strongly antagonistic mode, reimagined territory in exclusionary terms and constructed rigid symbolic boundaries between ‘us’ and ‘them’. In direct opposition to current processes of critical reflection on past conflicts and injustices, these movements promote memories which essentialize, as opposed to problematizing, a collective sense of sameness and we-ness, with accompanying sentiments of they-ness. (2016, 393)

Commemoration of the Matteis as neofascist martyrs is an occasion to stage this antagonistic approach to remembering. This approach is, I believe, both a reaction against the perceived weakening of neofascist heritage in the wake of the dissolution of the MSI and reflective of the need of contemporary neofascist groups to represent themselves as a continuation of an earlier tradition by honouring martyrological heritage. Since 1995, neofascist groups have shown an increasing possessiveness towards the memory of the Mattei brothers – two figures whose deaths were so quickly absorbed into the martyrology of the now-defunct MSI. I believe that the Mattei brothers hold a particular place in the pantheon of neofascist martyrs for contemporary Roman far-right groups for two reasons: firstly, due to the injustice of their deaths, which were caused by an attack on a domestic space, creating a very clear narrative that expresses the innocence of the victim and the evil of the perpetrators, as is typical of the antagonistic approach to remembering. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, because of their immediate commemoration as sacrificial martyrs for the MSI during the construction of a counter-memory, the brothers are considered symbols of a lost heritage. By honouring a heritage that ceased to exist in 1995 (at least officially), contemporary neofascist groups are able to position themselves as a continuation of an existing political tradition and condemn their historic and current adversaries. The final part of this article will address the memorial work of the victims’ surviving brother, Giampaolo Mattei, to combat this antagonistic approach to remembering adopted by the extreme right.

Reclaiming memory from the far right

In 2008, the first official ceremony was held to commemorate the Mattei brothers, with support from local government. It is worth contextualising this event here. Lollo's admission of guilt came in 2005, and the first Day of Memory for the Victims of Terrorism was held in 2007. By Giampaolo Mattei's own admission, the greatest steps towards inclusionary commemoration were taken by a centre-left mayor, Walter Veltroni (Mattei Reference Mattei2010). During his tenure, Veltroni dedicated a number of public spaces to victims of terrorism from the left and right. In 2005, he dedicated a road running through Rome's Villa Chigi park to Paolo Di Nella, a 22-year-old member of the MSI's Youth Front who was attacked while leafletting and died a week later. He also proposed the construction of a monument to all those who died in the period, regardless of political identity. In 2004, he approached the Mattei family with a proposal to name a street after Stefano and Virgilio, but they rejected the offer, concerned that it was a political move ahead of upcoming mayoral elections (Caccia Reference Caccia2004, 15). However, he did secure premises for and preside over the inauguration of the Mattei Brothers Association, established by Giampaolo to promote the sharing of bipartisan memories of the Years of Lead. In 2008, Veltroni invited Mattei to participate in an event to commemorate the victims of terrorism, during which he asked Mattei to join him onstage to meet Carla Verbano, mother of the far-left student Valerio Verbano who was killed in 1980. The subsequent spontaneous embrace between two people whose relatives were political opposites caught the attention of the media, and parallels were drawn with the famous handshake between Licia Rognini, the wife of Giuseppe Pinelli, and Gemma Capra, the wife of Luigi Calabresi.

Giampaolo Mattei has participated in the official, institutional commemoration ceremony held in the afternoon of 16 April each year since 2013. Organised by local government, members of the community and institutional figures also attend the event. It takes place at the foot of the building in which the arson occurred and involves a short ceremony led by officials and the laying of a wreath in the garden below the former Mattei flat (joining flowers brought by the community). This memory community's claim to the site is temporary; the wreath is removed after a certain period, and the flowers are cleared. It is the temporary memorial investment of those attending the ceremony that gives the building its mnemonic quality. It is not, therefore, a permanent monument that could become the focus of neofascist pilgrimage.

The ceremony is one element of ‘state memory-making’ as examined by Conway, who includes judicial enquiries in the ways in which official institutions can make memory (Reference Conway2010, 7). Given the failure of Italy's judicial system with regards to the Mattei case, sponsorship of this occasion is the sole institutional act of memory-making. This memorial approach is inclusionary and aims to insert the brothers’ memory within the wider collective memory of the victims of the Years of Lead. It is one of many memorial initiatives promoted by Giampaolo Mattei in an attempt to create a bipartisan ‘shared memory’ of the period (2010). It is, therefore, the opposite of the antagonistic approach to remembering adopted by the far right today. In 2007, Giampaolo established the Mattei Brothers Association, which organises events and exhibitions relating to the victims on the left and right, and an online video channel that interviews people from across the political spectrum who were affected by Italian terrorism.Footnote 4 In 2013, he opened an exhibition documenting the deaths of Roman victims from across the political spectrum. He is staunchly opposed to the neofascist commemoration ceremony, and the creation of physical sites of memory, which could become the focus of neofascist commemoration (Mattei Reference Mattei2016).Footnote 5 These inclusionary memorial initiatives are thus designed to counterbalance the antagonistic mode of remembering that has long characterised commemoration of his brothers by the extreme right.

Galvanised by the support of the local government, the memorial work of Giampaolo Mattei, and Lollo's admission of guilt, in the late 2000s a more inclusionary approach to remembering dominated. However, more recently, the antagonistic mode has threatened to reclaim its grip on memory, bolstered by the resurgence of extreme right populist fringe groups and the reincorporation of the far right into institutional politics. The success of the far-right Lega Nord and Fratelli d'Italia in the last general election showed that the extreme right is no longer marginalised, and the public demonstrations organised by grassroots groups like CasaPound have grown larger and more visible. Extremism has returned to the mainstream. Given the trends outlined throughout this article, it seems likely that we will see renewed momentum in the commemoration of the Mattei brothers by contemporary neofascist groups buoyed by developments in institutional politics.

This was evident in the official commemoration ceremony I attended on 16 April 2018. As occurs each year, attendees gathered on via Bibbiena while state representatives from Roma Capitale and the Lazio region prepared for the laying of the wreath. Preparations were interrupted by the arrival of ex-mayor Gianni Alemanno (once a member of the MSI, and the first mayor to have laid a wreath in Primavalle during his tenure in the late 2000s), accompanied by Guido Zappavigna, a known leader of the Roman ultràs, and Luigi Ciavardini – the former Armed Revolution Nuclei terrorist who was convicted for his involvement in the Bologna massacre and the assassination of magistrate Mario Amato in 1980. Mattei immediately refused to participate in the ceremony, insisting that the two local school groups in attendance follow him away from the building. He then gave an impromptu speech about the attack on his family, outlining his incredulity that the officiators would continue the ceremony alongside these extreme right figures: ‘They are laying a wreath with former assassins. It's really, truly shameful.’ Later that day, around 250 people participated in the unofficial neofascist march, including members of CasaPound, Roma Nord, and Forza Nuova, as well as some far-right councillors. As the formerly marginalised grassroots groups of the extreme right strengthen, so too does their commemoration of the Mattei brothers, whose memory has been so historically intertwined with far-right identity.

Conclusion

From the MSI's construction of a counter-memory of the attack to the present-day appropriation of memory by contemporary neofascist groups seeking to position themselves as a continuation of the neofascism of the 1970s, and, by extension, the earlier Fascist regime, this article has shown the role of the Mattei brothers’ martyrdom in the construction of far-right identity. Though a more bipartisan approach to memory may have dominated commemorative practices in the late 2000s, as political binaries become acute in Italy once again, memory of this Primavalle Arson has returned to the symbolic battleground. At an antifascist demonstration in Macerata in February 2018, militants from Aktion Antifascista chanted a slogan that evoked the memory of 16 April 1973: ‘Fire closes fascist dens, unless the fascists are inside it's not enough’ (Grignetti Reference Grignetti2018). Not only does it seem likely contemporary neofascists will continue to claim the brothers’ memory as their own, as exemplified by their appearance at the official commemoration ceremony in 2018, militants on the far left have made explicit reference to the Rogo in a chant that seemingly justified the killing of the brothers with reference to their perceived political identity. Giampaolo Mattei faces an uphill battle in his attempt to prevent continued commemoration of his brothers as historic martyrs of the far right.

Quotations translated by the author

Acknowledgements

The research for this article was undertaken as part of a PhD project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. I would like to thank John Foot and Anna Cento Bull for their comments on an early version of this article. Sincere thanks are also due to the two anonymous reviewers for their comprehensive and constructive feedback. I am also grateful to Giampaolo Mattei for meeting with me on several occasions.

Notes on contributor

Dr Amy King is a Senior Teaching Associate in Italian at the University of Bristol, where she completed her PhD in 2019. Her doctoral research examined the construction and role of secular martyrdom in Italy from the twentieth century to the present day. She holds an MA in Cultural Memory from the Institute of Germanic and Romance Studies, University of London, and has had fellowships at the Kluge Center, Library of Congress, and the British School at Rome. She was previously a financial journalist, covering Italian markets.