Cognitive restructuring is a therapeutic approach, traditionally been used in cognitive therapy and cognitive behavior therapy, that includes a set of procedures oriented to teach individuals how to evaluate, identify and change their maladaptive thoughts (Clark, Reference Clark and Hoffman2013). One of the most relevant tools of cognitive restructuring is the Socratic method: A dialogue to promote new insight and emerging perspectives (Overholser, Reference Overholser2018a).

Although cognitive techniques have been proven effective (Hollon et al., Reference Hollon, DeRubeis, Shelton, Amsterdam, Salomon, O’Reardon, Lovett, Young, Haman, Freeman and Gallop2005), and there are detailed contributions regarding how to question (e.g., Beck, Reference Beck1967; Beck et al., Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979; Ellis & Grieger, Reference Ellis and Grieger1977; Overholser, Reference Overholser2011; Overholser, Reference Overholser2018b); none of the guidelines are based on empirical evidence to support it, and more importantly, the lack of clarity about the mechanisms by which this technique works remains an unresolved issue (Clark & Egan, Reference Clark and Egan2015).

Socratic method consists essentially of speaking, therefore, a behavioral perspective on verbal processes can clarify how the procedure works. Thoughts, as an individual’s private verbal behavior, are studied in behavioral science by inferring control relationships with respect to behavior that we either cannot observe or we do not know their conditioning history (Schlinger, Reference Schlinger2011). Private events are as any other behavior, they do not have any special status (Moore, Reference Moore2000; Skinner, Reference Skinner1963). Thoughts could function either as responses or as stimuli; they can be explained based on principles of operant and classical learning. Therefore, cognitive techniques do not imply any special or different learning principle.

So, how is Socratic method explained by behavior analysis? From a broad perspective on verbal interaction, some authors believe verbal conditioning is ongoing in a therapy setting and verbal shaping as a key element for the change in therapy (Kohlenberg & Tsai, Reference Kohlenberg and Tsai1991; Schlinger & Alessi, Reference Schlinger and Alessi2011). Specifically, the dialogue in Socratic method could be understood as verbal shaping, results in verbal reinforcement through which the patient’s rules are modified (Abreu et al., Reference Abreu, Hübner and Lucchese2012; Poppen, Reference Poppen and Hayes1989). In a debate, the therapist’s questions discriminate the client’s verbalizations that precede and reinforce the following ones: A process that closely resembles verbal shaping (Froján-Parga et al., Reference Froján-Parga, Calero-Elvira, Pardo-Cebrián and Núñez de Prado-Gordillo2018).

In addition to the theoretical proposals, what has been empirically proven has so far come from the line of work that precedes this study and focuses on the analysis of the verbal interaction between therapist and patient (Calero-Elvira et al., Reference Calero-Elvira, Froján-Parga, Ruiz-Sancho and Alpañés-Freitag2013; Froján-Parga et al., Reference Froján-Parga, Calero-Elvira and Montaño-Fidalgo2011). It was found that when therapists asked questions preceded by certain information, the Socratic method was also more effective. It would appear that the therapists’ suggestion of certain information before questioning could be understood as a greater indication or guidance by therapists, which is contrary to what some of the classic authors of cognitive therapy, such as Beck, had proposed. Furthermore, these observational studies evidenced that there was a more successful shaping when therapists acted contingently with all verbalizations. A debate episode was classified as highly successful in occasions when the client makes at least one statement consistent with the goals of the debate (e.g., "I absolutely agree") and there is no recurrence of the target irrational verbalization. A debate was classified as partially successful in occasions when the client makes at least one statement that is partially consistent with the goals and there is no recurrence of the target irrational verbalization. Statements may include autoclitics denoting lack of emphasis (e.g., "Maybe I was a bit suspicious"). A debate may also be classified as partially successful if (a) the verbalization consistent with the debate goals occur on several occasions without emphasis incurring in subsequent recurrences of the target irrational belief, and (b) the verbalization consistent with the debate goals occurs only once with emphasis autoclitics and with subsequent recurrence of the target irrational belief. The debate is classified as a miss in occasions when the client fails to utter a single verbalization that would be fully or partially consistent with the debate goals. A debate could also be classified as a miss in occasions when a non-emphatic verbalization is partially consistent with the debate goal but there is a subsequent verbalization that contradicts it (i.e., recurrence of the irrational belief).

Considering shaping also as a process occurring in the other protagonist of the Socratic method, the therapist’s behavior could be modified through numerous trials (clinical practice). The divergences of different studies which define therapist’s experience and isolate related variables such as age, training, etc., have led to a great deal of confusion interpreting the data (Beutler, Reference Beutler1997; Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Roddy, Scott, Lewis and Jensen-Doss2018). However, beyond this confusion, some studies show therapists can benefit from their experience in certain conditions (Leon et al., Reference Leon, Martinovich, Lutz and Lyons2005). Also, the guidelines of Division 12 of the American Psychological Association (APA), Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice (2006), highlighted the importance of understanding the role of experience in clinical practice as a way to improve intervention outcomes.

Taking into account this background, the aim of this paper is to elucidate in detail what and why one type of therapist’s verbal performances during the Socratic method is associated with effective discussions due to the different mechanisms of change that occur. We proposed to study morphological aspects and their potential functional implications of verbal interaction in Socratic debate by looking at the clinical performance of experienced and inexperienced therapists through the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. Regarding the success of the Socratic method:

1. The expert therapists will have a higher percentage of total success Socratic method fragments and the inexperienced therapists will have more failure fragments.

2. The expert therapists will be reaching more approximation responses than opposite responses per Socratic fragment. There will be a higher rate of patient’s responses approximating the therapeutic objective and a lower rate of patient’s responses opposing this objective in expert Socratic method fragments.

Hypothesis 2. Regarding the degree of guidance or indication, in total success fragments of the Socratic method:

1. There will be differences in the specificity of the discriminative verbal stimuli presented: The expert therapists will use more questions with an indication component (exploring and questioning indicating) and will give their patients the solution more frequently (providing goal verbalization).

2. Experts will make a greater use of explanations that accompany the debate questions (“didactic strategies”): Explaining, using analogies, and training in reasoning rules; than inexperienced therapists, who will use it less.

Hypothesis 3. Regarding the way of questioning, since the training in applying the Socratic method is not based on functional, but on morphological aspects:

1. The inexperienced therapists will employ more debate questions (questioning).

2. The inexperienced therapists will follow an order in the sequencing of questions more frequently than the expert therapists: In the first and second part of the Socratic method there will be more questions that evaluate evidence and logic (questioning validity) and in the third part there will be questions that evaluate severity and/or utility (questioning severity and questioning utility).

Hypothesis 4. Regarding the use of the aversive component:

1. The expert therapists will use it more than the inexperienced therapists.

2. Experts will use it with a higher probability than expected by chance after the patients’ responses opposing the therapeutic objective, or intermediate with respect to the objective, and not at all after patient’s responses approximating this objective.

Hypothesis 5. Regarding other aspects of the Socratic method:

1. The experts will use technical explanations, motivating verbalizations and analogies more frequently than the inexperienced therapists.

2. In total success Socratic method fragments, experts will combine motivating verbalizations with reasoning rules.

Method

Sample

The sample consisted of 113 video recordings of Socratic method fragments (10 hours, 6 minutes and 39 seconds) from 18 clinical cases, and 11 therapists (90.9% were women) with different levels of experience: 10 cases correspond to the expert therapists and 8 to the inexperienced therapists. The experts had a continuous clinical experience of more than 6 years, and the inexperienced therapists had less than 2 years. Of the expert therapists, Therapist 1 was a Doctor in Psychology and clinical psychologist, and Therapists 2 and 3 were Masters in Clinical Psychology who worked mainly in psychological care. By contrast, all the inexperienced therapists were completing their masters training and received supervision in all their sessions by expert therapists. All therapists had a behavioral orientation and performed their clinical practice performed their clinical practice in a private psychological center. Both, expert and inexperience therapists have similar cultural background, ethnicity and they were native speakers in Spanish.

The applicants for psychological services were all adults (the average age was 28.7 years and 77.7% were women) and received individual psychological treatment. The problems for which they came to therapy were: Depression (33.3%); marital problems (16.6%); hypochondria (11.1%); problems in the workplace (11.1%); eating disorder and body image (11.1%); social skills (5.5%); relationship problems (5.5%); and general emotional problems (5.5%).

The study fully complied with the ethical requirements approved by the ethics committee of the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (Spain). It was a blinded study and none of the observers or supervisors had been therapists in the sample.

Instruments

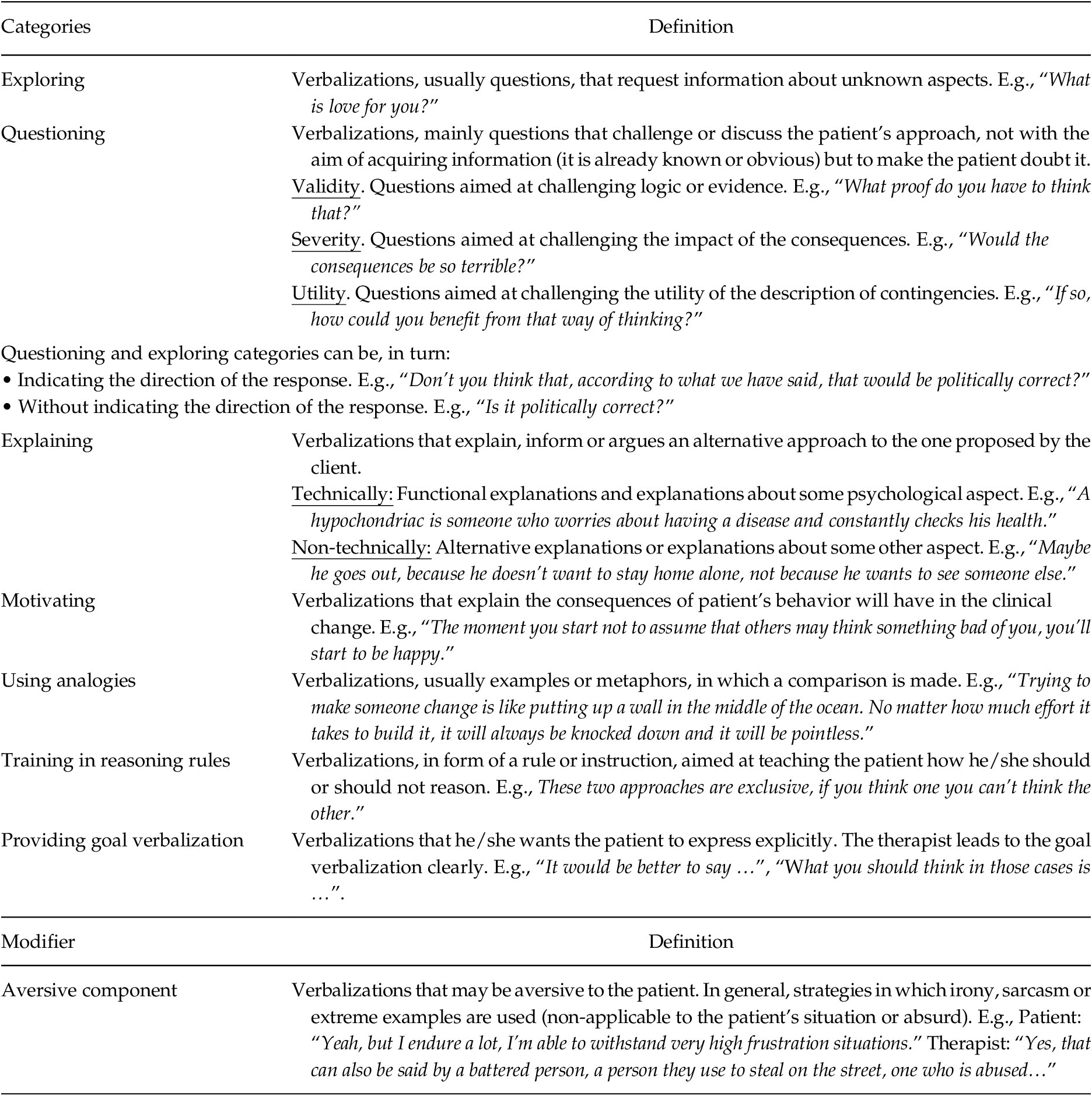

Therapist’s verbal behavior during Socratic fragments were categorized according to the Therapist System of Categories developed ad hoc for this study. The categories included in this system are included in Table 1.

Table 1. Therapist System of Categories

Patient’s utterances were coded following the Patient System of Categories developed in Calero-Elvira et al. (Reference Calero-Elvira, Froján-Parga, Ruiz-Sancho and Alpañés-Freitag2013) (p. 628): Verbalizations approximating the therapeutic objective of the Socratic method (VAT); Verbalizations opposing the therapeutic objective of the Socratic method (VOT); Intermediate Verbalizations with respect to the therapeutic objective of the Socratic method (VIT).

Finally, each debate fragment was categorized according to the Verbal Effectiveness Scale developed in Calero-Elvira et al. (Reference Calero-Elvira, Froján-Parga, Ruiz-Sancho and Alpañés-Freitag2013) (p. 629). This scale categorizes each debates fragment on an effectiveness scale according to three levels: Total success; Partial success and Failure, that involved the grade in which client’s verbalizations approximate to the Socratic method goals.

All session fragments were observed and coded through The Observer XT 12.5 software (Noldus®). This software was also used for the calculation of percentage of agreement and inter- and intra-rater reliability index. The Generalized Sequential Querier 5.1 (GSEQ®) (Bakeman & Quera, Reference Bakeman and Quera1995) was used for sequential analysis of recorded data and SPSS Stadistics 22 (IBM®) for other statistical analysis of the data.

Procedure

The Development of the Therapist System of Categories

This study is based on previous research with the same methodology and theme: A verbal interaction analysis during the Socratic method in cognitive restructuring; more precisely it was based on its categorization systems (Calero-Elvira et al., Reference Calero-Elvira, Froján-Parga, Ruiz-Sancho and Alpañés-Freitag2013; Froján-Parga et al., Reference Froján-Parga, Calero-Elvira and Montaño-Fidalgo2011). The present study delves into some of the categories not previously explored in order to test new hypotheses.

Observations and transcripts of the Socratic method fragments were made by 3 different observers: Observer 1, an expert in behavioral therapy and also expert in research from a verbal behavior analysis perspective; and Observers 2 and 3, graduates in psychology and with clinical training. Meetings were held periodically between the three observers and the supervisor of the team, a professor in Clinical Psychology. The team analyzed and refined the proposed definitions and categories, working on the definition of the categories until a preliminary categorization system was created. At that point, Observer 2 began to categorize the fragments that Observer 1 had registered, and the percentages of agreement and the Cohen’s Kappa coefficient of the fragments were calculated. The final version was achieved once the appropriate agreement levels and Kappa coefficient were reached (Cohen κ, .53 to .92).

Training and Reliability in the Patient System of Categories and the Verbal Effectiveness Scale

To analyze the patient’s behavior and the effectiveness of the Socratic method fragments, it was not necessary to develop new systems of categories because existing categorization systems were used. Instead, Observers 1 and 2 were trained in the following systems: The Patient System of Categories and the Verbal Effectiveness Scale (Calero-Elvira et al., Reference Calero-Elvira, Froján-Parga, Ruiz-Sancho and Alpañés-Freitag2013). They were trained until they achieved, according to the Patient System of Categories, at least 10 consecutive sessions with a Cohen’s Kappa coefficient of at least .60, which is the minimum value required to consider a good agreement (Bakeman, Reference Bakeman, Reis and Judd2000; Landis & Koch, Reference Landis and Koch1977); and, in the Verbal Effectiveness Scale, a Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) that was at least .80 in at least 6 consecutive records. This value was taken as the criteria because the intraclass correlation coefficient values can range between 0 and 1, and those that exceed .80 are considered optimal (Quera, Reference Quera, del Hierro and Baro1997).

Sample Registration

The sample was registered once adequate levels of reliability were guaranteed for all the categorization systems. The Therapist System of Categories and the Patient System of Categories were combined to record the therapist’s and the patient’s verbal behavior during the Socratic method. Reliability analysis was submitted to more than 10 % of the total study sample and records were maintained as long as the level of reliability achieved was at least .60 (Cohen κ, .61 to .90).

Once the verbal behavior of therapist and patient was recorded, the effectiveness of the Socratic method fragments was recorded using the Verbal Effectiveness Scale. The ICC was .947 (F =18.78, p = < .001) for intra-rater comparisons and for inter-rater comparisons the value was 1.00 (due the determinant of the covariance matrix is 0, the statistic program SPSS does not calculate the value of the F test neither the critical value of the statistic p).

Results

Differences in the Success of the Socratic Method Fragments (Hypothesis 1)

Statistically significant differences were found in partial success fragments and in failure fragments according to Pearson’s Chi Square test, as shown in Table 2. The experts had more fragments categorized as partial success than the inexperienced therapists, and fewer fragments classified as failure. However, there were no differences between total success fragments. Adjusted standardized residuals enabled us to see which comparison differences are found, and the direction of the relationship; those values lower than –1.96 i.e., a negative relationship, or higher than +1.96 i.e., a positive relationship.

Table 2. Experts and the Inexperienced Therapists in the Success of Socratic Method Fragments

Note. R = Adjusted standardized residuals.

The Mann-Witney U test was applied to find out the differences in the rate of patient verbalization that approach the therapeutic objective (VAT) and that move away from it (VOT). No statistically significant differences were found in the VAT rate between the expert and inexperienced therapist fragments (z = –1.748; p = .08). However, statistically significant differences were found in the rate of VOT (z = –2.549; p = .01), with the inexperienced therapists having a higher rate in their fragments.

Differences in the Degree of Guidance of the Socratic Method Fragments (Hypothesis 2)

In order to elucidate the differences between experts and inexperienced therapists in the issuance of verbalizations related to the degree of guidance in total success fragments, the fragments classified as a total success were selected, and the Mann-Witney U test was applied to establish if there were any differences in the degree of indication. Statistically significant differences were found: Expert therapists used fewer questions with an indication component, and inexperienced therapists used more questions indicating the direction of the response. Likewise, in order to interpret this hypothesis more completely, the use of the questions without indicating was also taken into account. It was found that inexperienced therapists used more questions without indicating the direction of the response; i.e., the inexperienced therapists used more questions, both indicating and without indicating, than the experts. Regarding the effect sizes found which were measured according to Cohen’s d index, they are considered to be medium at between .50 and .80 (McGraw & Wong, Reference McGraw and Wong1992). On the other hand, no statistically significant differences were found between experts and inexperienced therapists in providing the goal verbalization to the patient.

Finally, regarding the use of explanations that accompany and guide debate questions, statistically significant differences were found between the use of ‘didactic’ strategies (explaining, using analogies, training in reasoning rules), between expert and inexperienced therapists, although the effect size of this relationship is considered to be small at between .20 and .50. Table 3 shows the data related to this second hypothesis.

Table 3. Verbalizations Related of Guidance in Total Success Fragments

Differences in the Way of Questioning (Hypothesis 3)

Figure 1 shows that inexperienced therapists employed more questions aimed at questioning validity, severity and utility than experts. These differences are statistically significant as indicated by the values of the Mann-Witney U test. On the other hand, a nominal variable (order) was created to check whether the therapists followed any order throughout the Socratic method in question sequencing. It was classified that an order was followed as long as questioning validity appeared in the first or second part, but not in the third part and, in turn, questioning severity and utility appeared in the second or third, but not in the first part (following the traditional proposals for the Socratic method). Although it was found that the general trend was not to follow an order, the inexperienced therapists followed it to a greater extent (15.22 %) than the experts (0 %). These differences are statistically significant as proven by the Mann-Witney U test (χ 2 = 8.45; p = .04).

Figure 1. Types of Questioning During the Socratic Method by Expert and Inexperienced Therapists

Note: Absolute frequency of verbalisations aimed at questioning issued in each Socratic fragment. Mean, standard deviation and results of the Mann-Whitney U test are specified in each of the categories: Validity, severity and utility.

Differences in the Use of the Aversive Component between Expert and Inexperienced Therapists (Hypothesis 4)

Firstly, we wanted to determine whether expert and inexperienced therapists used the aversive component with the same frequency in the Socratic method. The frequency of use of this category was 14 for inexperience therapists and 75 for experience therapists. The results indicated that experts used it more frequently (M = .67; SD = .12) than inexperienced therapists (M = .05; SD = .04). These differences are statistically significant, as shown by the Mann-Witney U test values (z = 1240.5; p = .01).

Secondly, although it was not part of the hypotheses of the study, we also wanted to investigate whether the differences in use by experts and inexperienced therapists occurred in all the Socratic method fragment groups according to their success. Therefore, fragments classified with either total success, partial success and failure were selected, and the use of the aversive component was compared according to experience. Statistically significant differences were found in total success fragments, in terms of their frequency of use, using the Mann-Witney U test (z = –2.16; p = .03). No differences were found in the partial success fragments (z = –1.193; p = .30) or the failure fragments (z = –.93; p = .63).

Regarding the sequences of interaction between the therapist and the patient in the use of the aversive component, sequential analysis was used to verify if there was a relationship between the behavior that occurred adjacent to another by calculating the probability of the transition of one certain behavior and another behavior occurring either before (positive delay) or after (negative delay).

Thus, statistical significance associated with the probabilities of +1 delay between the patient’s behavior categorized as VAT, VOT and VIT and the therapist’s verbalizations with an aversive component, was analyzed. Statistically significant differences were found: Expert therapists used this component contingently only after intermediate patient verbalizations or verbalizations opposing the therapeutic objective (VIT and VOT). By contrast the inexperienced therapists used it after verbalizations approximating the therapeutic objective (VAT), as can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Transition Diagrams between Therapist’s Aversive Component and Client’s Verbalizations

Note. Q = Yule’s Q; R = adjusted standardized residuals; p = p value.

* Significant contingencies.

Differences in the Use of Analogies and Technical Explanations between the Expert and the Inexperienced Therapists (Hypothesis 5)

The frequency emission of analogies was 39 for inexperience therapists and 25 for expert therapists; motivating verbalization was 26 and 38, respectively; and 117 and 171 for explanation techniques. No statistically significant differences were found between the inexperienced therapists and the experts in the use of analogies (z = –.74; p = .476), motivating verbalizations (z = –1.36; p = .17), or explanation techniques (z = – 1.02; p = .229). Regarding the sequential analysis, we investigated whether the training in reasoning rules was followed by motivating verbalizations in total success fragments. In the case of the inexperienced therapists, it was not found that with a greater probability than expected by chance, they chained these sequences (R = –.21; p = .841). However, this contrasted with the results of the expert therapists (R = 6.16; Q = .91; p = .01).

Discussion

The present study shows interesting differences in the way in which the Socratic method is carried out by experts and inexperienced, although not always in the expected direction. We found before (Calero-Elvira et al., Reference Calero-Elvira, Froján-Parga, Ruiz-Sancho and Alpañés-Freitag2013) that Socratic method could be understood as a verbal shaping. In the present study, we have tried to study morphological aspects of the verbal interaction to know how this verbal shaping could be more successful and with this aim we have analyzed differences between expert and inexperienced therapists. In this section, we analyze the differenced we have found in the proposed morphological categories and we also indicate the potential functional implications.

Contrary to our hypothesis, both expert and inexperienced therapists had total success with Socratic method fragments. However, experts failed less often, had very few failure fragments but did have more partial success fragments. There was also no difference regarding the VAT rate, but the fragments of inexperienced therapists contained more VOT than the experts’ fragments. Thus, Hypothesis 1 (a and b), were partially confirmed. It could be that despite the difficulties that expert may encounter in changing patient’s verbalizations, most of them continue with their questioning and probably use better arguments and strategies until the patient’s approximation response is achieved. In this case, it seems that experience does at least help to make fewer mistakes or to fail less often. There is a certain parallelism with outcome studies of experts and inexperienced therapists, in which the differences are not so much by being more successful, but the fact that the experts have fewer dropouts (Stein & Lambert, Reference Stein and Lambert1995). As a result of these findings, observing the performance of expert therapists in partial success Socratic method fragments could be taken as a model to guide novice therapists or therapists in training to be able to identify the performances that may enhance their success.

A classical controversial aspect of the Socratic method in cognitive restructuring is whether it is preferable to provide the solution to the patient or let them discover it by themselves. Both styles can be identified with each of the ‘fathers’ of cognitive restructuring: The didactic dispute is the style proposed by Ellis (Ellis & Grieger, Reference Ellis and Grieger1977) and the non-confrontational style of guided discovery through the Socratic method proposed by Beck (Beck, Reference Beck1967; Beck et al., Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979). The findings of this study suggest that in the successful fragments of the Socratic method, both expert and inexperienced therapists guide their patients to the solution, although they use different methods. There were no differences in the frequency in which they gave their patients the goal verbalization, but the inexperienced therapists tended to suggest or indicated the response when they questioned more than experts did, which leads us to reject hypothesis 2(a). However, the experts use strategies that are more didactic, which supports Hypothesis 2(b).

When it comes to questioning, the inexperienced therapists did this to a greater extent and also tended to follow an order in the sequencing of questions compared with the performance of the experts. These data support Hypothesis 3 and concur with the data found in a previous study on the use of the Socratic method, which also found that the inexperienced therapists used an order in questioning to a greater extent (Pardo-Cebrián & Calero-Elvira, Reference Pardo-Cebrián and Calero-Elvira2017). However, none of these performances relates to total success fragments of Socratic method. It is possible that inexperienced therapists used it to a greater extent because they have recently been trained in the application of the Socratic method and they follow the few existing guidelines. For example, Beck et al. (Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979) talk about specific types of questions i.e. validity, severity and utility, and the importance of ordering them carefully. It is more likely that the inexperienced therapists tend to follow rules and instructions when applying a new technique in the beginning. This leads us to consider whether during their training it would be more effective to teach novice therapists: (a) Knowledge about the functional analysis of verbal behavior; together with (b) argumentation and logic techniques to improve their questioning; instead of using Beck or Ellis’s model guidelines that have no functional perspective that support them.

Based on the results of this study, we can confirm Hypothesis 4: The experts use the aversive component more, and after patient verbalization they want to reduce or modify. Regarding the interaction, it is very striking that inexperienced therapists pair the aversive component with patients’ adaptive verbalizations. Inexperienced therapists may not know how to discriminate that these verbalizations are an approximation to the therapeutic objective. This could indicate that one of the aspects that may be learned through practice is to identify, properly and at every moment, when patients’ verbalizations approach or move away from the therapeutic objective of the Socratic method.

Another possible reason is that the use of the aversive component in therapy does not have a good reputation. Outside the scope of behavior analysis, psychologists often do not know the meaning, or technical use of the term punishment and relate it to aversive stimulation and responses of discomfort and suffering. Therefore, inexperienced therapists may have some fear of using it.

Finally, both experts and inexperienced therapists use analogies and technical explanations with a significantly similar frequency in the total success fragments of the Socratic method, which leads us to reject Hypothesis 5(a). On the other hand, the results allow us to confirm Hypothesis 5(b), because the successful fragments of the expert therapists are characterized by chains of instructions, and motivating verbalizations, which is unlike what happens with the fragments of the inexperienced therapists. As has been shown in studies of instructions (De Pascual Verdú & Trujillo Sánchez, Reference De Pascual Verdú and Trujillo Sánchez2018; Marchena Giráldez, Reference Marchena Giráldez2017), when these are accompanied by motivating verbalizations, their compliance is more likely outside the clinical context. It makes sense that using the instructions in this way, the experts have been reinforced by a greater accomplishment of them by the patients.

Some studies have not found any differences in the differential efficacy of therapy when comparing the level of therapist experience (Norton et al., Reference Norton, Little and Wetterneck2014; Okiishi et al., Reference Okiishi, Lambert, Eggett, Nielsen, Dayton and Vermeersch2006). However, some differences were found in finer analyses (Leon et al., Reference Leon, Martinovich, Lutz and Lyons2005). We believe that this is the case of the present study, in which the analysis type on the specific performance of clinicians, enabled us to find specific differences that otherwise might not be visible.

Taking up the contributions of the APA Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice (2006), the data from this study can provide a brief guideline on how to use the Socratic method in cognitive restructuring based on morphological and functional aspects: (a) To use the aversive component, both classical conditioning pairings or operant conditioning consequences (verbalizations with morphology as: Extreme examples, irony, etc.), frequently and contingently on those verbalizations that are subject of; (b) to conduct a Socratic method full of explanations, analogies and reasoning rules (“didactic strategies”) as a way to discriminate more specific client responses; and (c) to accompany instructions about how to reason with motivating verbalizations (establishment or abolition operations), describing the consequences that will follow the behavior. All these indications would be framed and linked to those indicated in previous studies (Calero-Elvira et al., Reference Calero-Elvira, Froján-Parga, Ruiz-Sancho and Alpañés-Freitag2013), in which the steps for proper verbal shaping have been proposed.

The above results should be taken with caution taking into consideration the limitations of this study. On the one hand, when comparing the results according to the level of experience, it is better that the therapist’s variables are specified and controlled (Leon et al., Reference Leon, Martinovich, Lutz and Lyons2005). Therefore, it would have been desirable to specify and control more the type of therapists’ training analyzed and the type of concrete experience, like the number of cases, specialization by clinical areas and educational level. On the other hand, for future studies it would be desirable to know if the success of the Socratic method also translates into a change in the patients’ behavior out of session.

To date, this study is the first in which the performance of expert and inexperienced therapists in cognitive restructuring technique has been analyzed in a comparative way. The findings presented here represent a contribution towards the creation of a guideline based on evidence and not only on morphological but also potential functional aspects of verbal interaction on how to apply the Socratic method.