Introduction

Hoarding disorder is defined as a persistent difficulty in discarding or parting with possessions, accompanied by a persistent need to save items, resulting in cluttered living areas, such that these spaces cannot serve their intended use (APA, 2013). Hoarding disorder is common, with approximately 2.5% of the general population meeting diagnostic criteria for hoarding disorder (Postlethwaite et al., Reference Postlethwaite, Kellett and Mataix-Cols2019).

Hoarding problems commonly arise in adolescence, with a median age of onset between 11 and 15 years (Tolin et al., Reference Tolin, Meunier, Frost and Steketee2010). However, although hoarding has an early age of onset, people with hoarding problems are typically seen by community service providers in later life, which may suggest a longer treatment-onset gap than other anxiety disorders (Thew and Salkovskis, Reference Thew and Salkovskis2016).

Whilst our understanding of hoarding difficulties is not well-developed, cognitive behavioural models and treatments predominate and attempt to describe the underlying mechanisms of the hoarding disorder and guide treatment (Frost and Hartl, Reference Frost and Hartl1996; Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Salkovskis and Oldfield2013; Seaman et al., Reference Seaman, Oldfield, Gordon, Forrester and Salkovskis2010).

Frost and Hartl (Reference Frost and Hartl1996) propose that hoarding arises from multiple components, including information processing and cognitive deficits, emotional attachment to possessions, and behavioural avoidance (including postponing decisions and avoiding distress associated with discarding possessions). Seaman et al. (Reference Seaman, Oldfield, Gordon, Forrester and Salkovskis2010) and Gordon et al. (Reference Gordon, Salkovskis and Oldfield2013) propose that hoarding difficulties can arise from at least three cognitive processes, which may act in isolation or in interaction with one another. These processes include (a) the intention to prevent harm (harm avoidance), (b) to save due to previous experiences of deprivation (material deprivation), and (c) where being separated from items will likely result in an experience of significant personal loss (attachment disturbance).

These theoretical frameworks strongly suggest that hoarding behaviour can be the outcome of multiple different psychological processes and may, therefore, represent a ‘final common pathway’. This means that there may be some complexity to the treatment approaches required for hoarding difficulties; such treatments either take the form of CBT or are more practically focused, informed by CBT principles.

Community-based professional services (such as local authorities, housing agencies, and fire and rescue) deal with the physical reality of hoarding, often entirely independently of mental health services (Chapin et al., Reference Chapin, Sergeant, Landry, Koenig, Leiste and Reynolds2010). Due to the complex health and safety risks, people who hoard typically have multiple agencies involved in their care and for community services, issues of risk may predominate (Ayers and Dozier, Reference Ayers and Dozier2015; Frost et al., Reference Frost, Steketee and Williams2000). For example, fire and rescue services may see people with hoarding problems due to the risk posed to people in adjoining properties and emergency responders, blocking of entry and escape routes, and accumulation of combustible materials making fires more likely to spread faster and become more difficult to suppress (Kwok et al., Reference Kwok, Bratiotis, Luu, Lauster, Kysow and Wood2018). Similarly, environmental health services may see people with hoarding difficulties due to them being at a greater risk of falls, mould accumulation, rodent infestation, and insanitary living conditions (Steketee et al., Reference Steketee, Frost and Kim2001). It is, therefore, important to understand how services work together to meet the needs of people with hoarding problems and for such services to have a better understanding of the psychological (cognitive behavioural) factors involved in the maintenance of problems with acquisition and discarding.

There are a wide range of different protocols which have been suggested by different agencies to assist in understanding how best to support people with hoarding issues in the UK (e.g. Slough Borough Council, 2021; Lincolnshire Safeguarding Adults Board, 2020). However, at present, there are no formal evidence-based guidelines in the management of risk and provision of support by and from community-based services, or for the treatment of hoarding disorder from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). The integration of mental health services providing CBT tends to be weak or absent.

In practical terms, there are few psychological treatment options in the UK except for a small number of specialist centres, which often leaves other services without specific psychological expertise working closely and individually with people with hoarding difficulties (Koenig et al., Reference Koenig, Leiste, Spano and Chapin2013; McGuire et al., Reference McGuire, Kaercher, Park and Storch2013).

There is little in the way of consistency to guide the individual or coordinated efforts of community services and how these might relate to mental health services (Koenig et al., Reference Koenig, Leiste, Spano and Chapin2013). Whilst there has been some evaluation of the successes of cross-disciplinary teams in working with people with hoarding problems (Kysow et al., Reference Kysow, Bratiotis, Lauster and Woody2020) and the impact of hoarding task forces (Bratiotis, Reference Bratiotis2013), to our knowledge, there are no models of how distinct agencies might work together more effectively. We propose that (a) closer working relationships are essential and (b) that such work needs to be psychologically informed from a CBT perspective.

The present study seeks to answer the following research questions:

-

(1) Does an explicitly multi-agency hoarding conference with a predominantly CBT focus and including people with personal experience of hoarding problems increase professionals’ understanding and confidence in working with people with hoarding difficulties?

-

(2) What are professionals’ perceptions of improvements that could be made to multi-agency service provision within such a context?

-

(3) What can we learn from service users’ perspectives on the improvement of multi-agency service provision?

Method

Design

This study involved a mixed methods design, with two phases:

-

Phase 1: A quantitative analysis of conference data, primarily to assess the level of change in professionals’ understanding and confidence from participation, and a qualitative content analysis of professionals’ perceptions of improvements that could be made to service provision.

-

Phase 2: A qualitative thematic analysis of focus group data from people with personal experience of hoarding problems, who were asked to comment on professionals’ responses and contribute their own ideas of how multi-agency service provision could be improved.

Participants

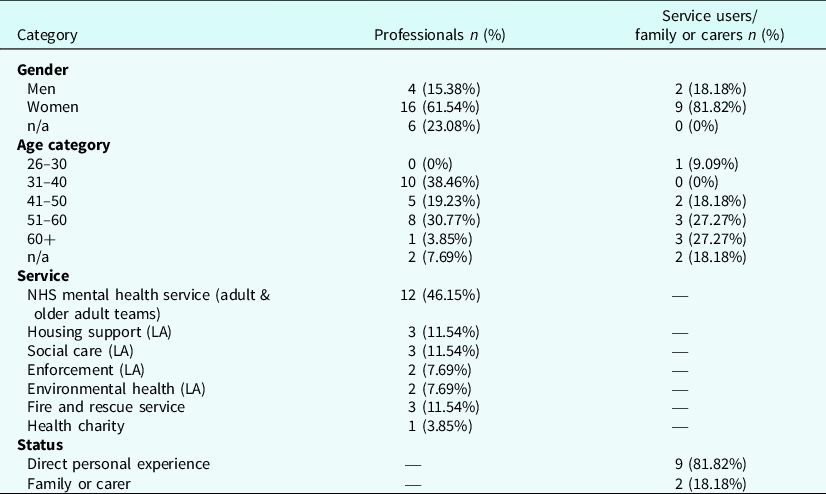

Demographic status and characteristics of professionals (phase 1) and people with personal experience of hoarding difficulties (phase 2) is presented in Table 1. Professionals from mental health services, the local authority, local charities supporting people with hoarding problems, and the fire and rescue service were invited by email to attend the in-person conference.

Table 1. Demographic information on pre–post professional conference completers (n=26) and focus group participants, including service users, their family, or carers (n=11)

All percentages are rounded to 2 decimal places. LA = local authority.

Of 48 professional attendees, 38 (79.17%) completed the pre-conference questionnaires, and 26 (68.5%) of these completed the post-conference questionnaires. Analyses within this report are based on delegates with paired (pre- and post-conference) data. Respondents reported seeing a career mean average of 12.08 (SD = 22.69) people with hoarding problems and completing a home visit with a career mean average of 9.96 (SD = 21.86).

People with personal experience of hoarding difficulties were invited by email to attend a focus group via the Buckinghamshire and Milton Keynes hoarding support group (Buckinghamshire Fire and Rescue Service). All 25 members of this support group were invited, with 11 (44%) choosing to take part.

Completers vs non-completers

Statistical analyses on pre-conference questionnaires indicated that completers of the post-conference questionnaire were initially less confident in helping people with hoarding and rated their understanding of national and local policy as less advanced than non-completers (p < .05), but scores did not significantly differ from non-completers in any other domains.

Measures

A semi-idiographic, researcher-created questionnaire was developed and provided to professionals exploring confidence and understanding in working with hoarding at pre- and post-conference, and open-ended questions for content analysis were provided at post-conference. Validity and reliability data are not available for this questionnaire, and internal consistency has not been computed due to the heterogeneous nature of questionnaire items.

For the focus group, after a presentation on the results of phase 1, a schedule of open-ended questions was asked relating to participants’ perspectives on what professionals had said and then, their unique perspectives on improvements to multi-disciplinary service provision, with open-ended prompts, where appropriate, inspired by recommendations on focus group interviewing from Krueger and Casey (Reference Krueger and Casey2010).

Procedure

Phase 1

Professionals participated in a one-day conference, with the aim of (1) building professionals’ knowledge, confidence and understanding in working with hoarding problems, (2) bringing together agencies to reflect on working with hoarding problems, and (3) enabling conversations between agencies on joint working, and including experts by experience in those conversations.

Participants completed pre-conference questionnaires prior to participation. Presentations then focused on building a psychological understanding of hoarding based on CBT principles, national and local policies, reducing risks associated with hoarding (fire safety and environmental health), and hearing from experts by experience. Group exercises and roundtable discussions were held between professionals, with a focus on how to address barriers and better support people with hoarding problems. Following the conference, participants completed a post-conference questionnaire.

Phase 2

Participants participated in a hybrid focus group, such that all participants were invited to attend either in person (n = 1) or online via Zoom video conferencing (n = 10), with interaction between the two formats. Participants in phase 2 were presented with a 15-minute PowerPoint presentation on the results of phase 1 prior to the focus group. Participants were encouraged to speak to each other, within minimal unobtrusive control exercised by facilitators. The focus group lasted for 1 hour and 24 minutes, and was recorded, transcribed verbatim, and anonymised.

Analyses

Phase 1

All quantitative summaries and statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 28. Bonferroni-corrected thresholds (α) for all t-tests were set to .007 to reduce the familywise (type 1) error rate. Individual t-tests were conducted without imputation, such that missing responses were excluded from individual comparisons. Questionnaire items were heterogenous in nature and, therefore, internal consistency could not be meaningfully calculated.

A manifest content analysis was completed on professionals’ open-ended questionnaire responses, such that surface-level descriptions of responses are presented, due to limited open-ended responses and to remain close to the original meanings of the respondents (Bengtsson, Reference Bengtsson2016; Burnard, Reference Burnard1991).

After reading all questionnaire responses carefully, the first researcher generated a codebook, consisting of a list of codes and their definitions. A second researcher independently categorised participant responses into codes. The initial inter-rater coding agreement was 93.75%, and rose to 100% following a resolution meeting.

Phase 2

A thematic analysis was conducted to understand the shared perceptions (derived from the focus group) of improvements that could be made to service provision from the participants’ unique personal experiences of hoarding. The thematic analysis was independently completed by two separate researchers in accordance with the following steps of thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006): (1) data familiarisation, (2) generation of initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, and (5) defining and naming themes. Both researchers held a triangulation meeting to increase the precision of the analysis and decided on the final over-arching and subthemes, with 100% agreement.

Results

Phase 1: Professionals’ responses to the conference

Impact of the conference on professionals’ confidence and understanding

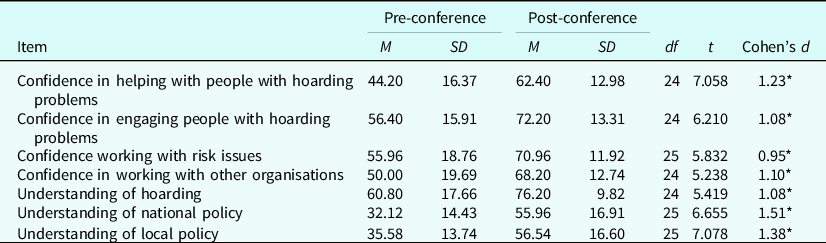

Professionals’ confidence and understanding in all domains significantly increased over the course of the conference. All statistical analyses are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Impact of the hoarding conference on understanding and confidence

*p<.001.

Usefulness of the conference and future interest

The mean average rating of the usefulness of the workshop in relation to direct work with people with hoarding difficulties was 72.69 out of 100 (SD = 16.93), and the mean average rating of the usefulness of the workshop in improving general knowledge of the subject was 75.19 out of 100 (SD = 13.96).

Improvements to multi-agency service provision

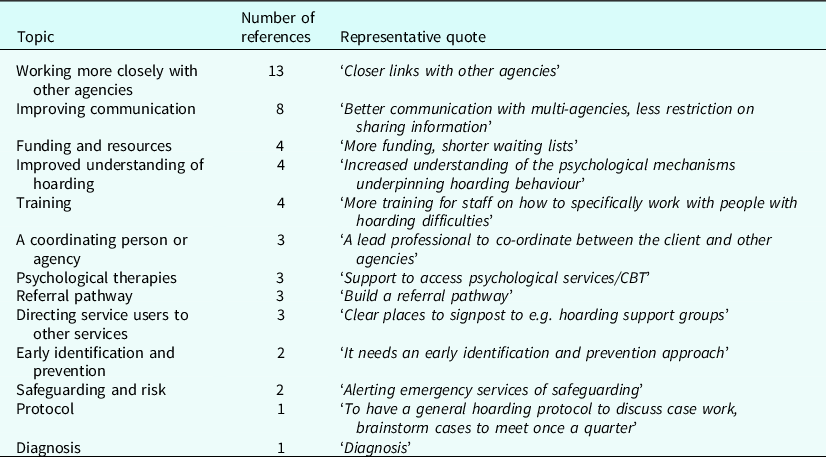

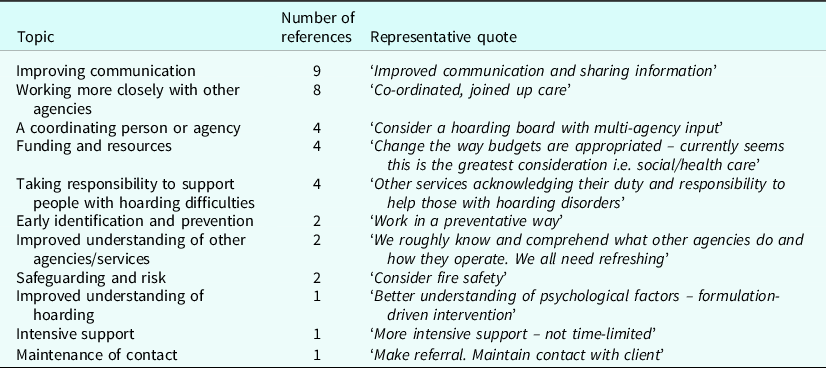

Professionals’ perceptions of improvements that could be made to their own service are presented in Table 3, and perceptions of improvements that could be made to other services are presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Professionals’ responses detailing their most important improvements to their own service

Table 4. Professionals’ responses to the question ‘Could you identify how other services might be able to work in better ways with yours to help people with hoarding difficulties?’

The most cited improvements that could be made to participants’ own service were to work more closely and improve communication with other agencies, increase funding and resources, develop an improved understanding of hoarding, and receive greater access to training.

The most commonly cited ways in which other services could make improvements were improving communication and working more closely with other agencies, increasing funding and resources, having a coordinating person or agency, and taking responsibility to support people with hoarding problems.

Phase 2: Responses of people with personal experience

Three main over-arching themes were identified from people with personal experience of hoarding:

-

Improved understanding of hoarding;

-

Need for improved resources;

-

Improved inter-agency working.

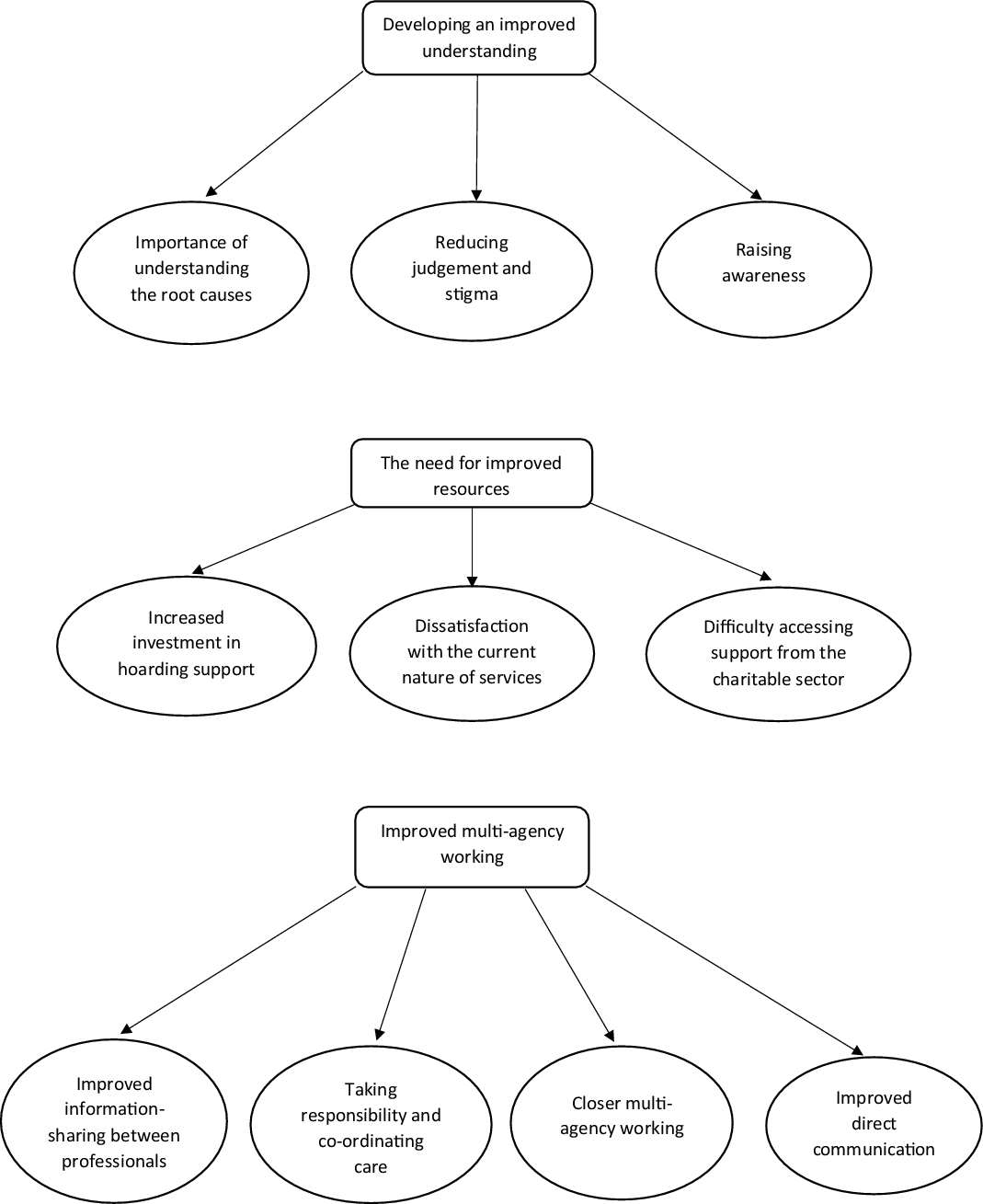

These three themes and their subthemes, along with representative quotes, are presented in prose and via a thematic map (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Thematic map of responses from people with personal experience of hoarding.

Over-arching theme 1: Developing an improved understanding

Subtheme 1.1: Importance of understanding the root causes

During the focus group, four participants identified the need and importance of both themselves and professionals identifying the core reasons which have given rise to their hoarding difficulties:

‘Well I quite agree I mean I think and until you get to the bottom of um why somebody’s doing what they’re doing, it’s very difficult to get out of that um vicious circle, and I don’t know how you get to that point’ [Participant 9]

Subtheme 1.2: Reducing judgement and stigma

Five participants highlighted the impact and need for reduced judgement and stigma associated with hoarding difficulties, from both professionals and on a societal level:

‘If you compare it with how a physical illness would be treated, with sort of, the sort of sympathy, lack of, the lack of judgement that someone who had a physical illness would be treated with, doesn’t necessarily follow through to someone that would have, um, a hoarding problem…’ [Participant 4]

‘Family don’t understand, friends don’t understand, because it is an issue that is quite laughed at really, in society’ [Participant 8]

Subtheme 1.3: Raising awareness

Three participants reported the need for raised awareness of hoarding problems among professionals and in wider society:

‘… so when they go into people’s houses, they have an extra awareness of the fact that … it’s going to be difficult. People don’t really want you to come in or if they do, they might only want to show you certain places…’ [Participant 5]

‘Get a spot on one of those popular magazine programmes’ [Participant 3]

Over-arching theme 2: The need for improved resources

Subtheme 2.1: Increased investment in hoarding support

Four participants identified the need for greater funding and resources for mental health support:

‘… I do feel that obviously normally with mental health you do only get six sessions, twelve if you’re very lucky and that basically only hits the surface’ [Participant 6]

‘… I think there needs to be more funding and shorter waiting lists for um you know mental health counselling um, I think a few of us have been on, several times, waiting lists for sort of two and a half years…’ [Participant 8]

Subtheme 2.2: Dissatisfaction with the current nature of services

Four participants spoke to being offered interventions which were ineffective and discussed difficulties arising from the way in which services were structured when they did make attempts to access support:

‘…I had offers from the council to help clear some areas of my place, and I said well what would happen, and they said oh well somebody will just come in and throw everything out…’ [Participant 7]

‘… but you take that step and put yourself out there, but it doesn’t quite work out because of the convoluted nature of the services um so you look to other options’ [Participant 4]

Subtheme 2.3: Difficulty accessing support from the charitable sector

Five participants indicated some difficulties accessing support from some charities and a lack of clarity on what such charities might be able to offer:

‘I’ve contacted [Charity X], they never call, they never answer the phone, they never call back’ [Participant 8]

Over-arching theme 3: Improved multi-agency working

Subtheme 3.1: Improved information-sharing between professionals

Two participants highlighted the need to remedy problems with information-sharing between agencies so that the emphasis was not on them to supply the same information to a different agency:

‘…the agencies all capture their own separate information and don’t want to rely on each other’s information, so they don’t for whatever reason or data protection they don’t pass on the relevant details to each other, so very often I was sort of having to deal with different people having to go through the same information yet again… things were being dropped between agencies um so there is something about information-sharing’ [Participant 2]

Subtheme 3.2: Taking responsibility and co-ordinating care

Two participants identified the need for services to take responsibility in supporting people with hoarding problems and to take a lead in coordinating their care:

‘… I noticed that under other services it has taking responsibility to support people with hoarding difficulties but that’s not a top answer under my service… it looks as if there’s a sort of bias towards well somebody needs to take responsibility however it’s not necessarily my service’ [Participant 3]

Subtheme 3.3: Closer multi-agency working

Two participants identified the need for the communication between agencies to go beyond information-sharing, such that services actively work and collaborate to resolve hoarding difficulties:

‘… If the mental health people work with the fire service and other services, maybe they would all get to sort of understand hoarding issues better’ [Participant 6]

Subtheme 3.4: Improved direct communication

Two participants highlighted the importance of improving direct communication with people with hoarding problems:

‘… you’re having to chase people and reiterate what you’ve said before…’ [Participant 1]

Discussion

The current study found that professionals’ confidence and understanding increased significantly following a multi-agency hoarding conference with a CBT focus, and professionals had a range of suggestions for how to improve services (most commonly, working more closely and improving communication with other services). People with personal experience of hoarding also suggested improvements to understanding, resources and multi-agency working.

The increases observed in professionals’ confidence and understanding from pre- to post-conference highlight the beneficial effect of multi-disciplinary training incorporating cognitive behavioural conceptualisations of hoarding (Frost and Hartl, Reference Frost and Hartl1996; Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Salkovskis and Oldfield2013), perspectives of people with personal experience, and multi-agency advice on risk reduction, for professionals to be better informed to support people with hoarding problems.

Professionals most frequently identified that their service could improve the way it supports people with hoarding difficulties by working more closely and improving communication with other agencies, receiving access to further funding and resources, improving their understanding of hoarding, and accessing training opportunities. They similarly commonly identified that other services would benefit from working more closely with other agencies and improving communication, having greater access to funding and resources, having a coordinating person or agency, and taking responsibility to support people with hoarding problems.

These recommendations are not surprising, given the complex health and safety risks associated with working with hoarding problems (Kwok et al., Reference Kwok, Bratiotis, Luu, Lauster, Kysow and Wood2018; Steketee et al., Reference Steketee, Frost and Kim2001), which typically leads people with hoarding problems to have multiple services involved in their care (Ayers and Dozier, Reference Ayers and Dozier2015; Frost et al., Reference Frost, Steketee and Williams2000), and the successes of integrated, cross-disciplinary teams in working with hoarding problems (Kysow et al., Reference Kysow, Bratiotis, Lauster and Woody2020). It may, therefore, be important for services to identify mechanisms which may aid communication, coordination, and closer multi-agency working to facilitate lasting and meaningful change for people with hoarding problems.

People with personal experience of hoarding highlighted improvements to be made in three domains: developing an improved understanding of hoarding, the need for improved resources, and improved inter-agency working, echoing some commonly cited improvements from professionals. It is particularly important for those with personal experience to feel understood, be provided with appropriate resources, and have the belief that professionals are working together to support them, as there appears to be a longer treatment-onset gap in hoarding than is seen in other anxiety disorders, which may account for why people with hoarding problems are typically seen in later life (Thew and Salkovskis, Reference Thew and Salkovskis2016).

Limitations

The present study was limited by a small sample size of professionals and people with personal experience of hoarding, in addition to the low number of professionals opting to complete both pre- and post-conference questionnaires from the total number of attendees (45.83%), which may place limitations on the generalisability of findings. Participants were also from one region in the UK and professionals participated in a single conference, which may further limit the generalisability and external validity of the study to other regions, for conclusions to be reached as to how services could improve on a national level.

It should also be noted that people with direct personal experience of hoarding did not complete diagnostic interviews or questionnaires to verify their current diagnostic status, but had met service criteria for inclusion in a hoarding support group.

Another limitation to note is the question of how meaningful and sustainable changes in understanding and confidence were post-conference. As follow-up data were not collected, it is not known whether this change in understanding and confidence could be sustained for a longer period after the event and if self-reported improvements to confidence and understanding were meaningful and led to behavioural changes.

However, this study provides an important first step in understanding professional and service user perspectives on improvements that could be made to clinical services to better support people with hoarding problems.

As with much qualitative research, content and thematic analyses may have been influenced by the subjective biases of the researchers. However, the manifest nature of content analysis (remaining close to the text), and the involvement of two researchers in both qualitative analyses may have increased the inter-rater reliability and therefore accuracy of qualitative analyses.

Directions for future research

Future research may profit from exploring how multi-disciplinary working may be of benefit to people with hoarding problems, most preferably through the implementation of randomised controlled trials exploring the additive effect of joint-working or consultation relative to usual care. However, this may also be explored on the level of service evaluation or single case experimental design studies, by assessing how patient outcomes have been affected by the implementation of multi-agency working.

Key practice points

-

(1) A multi-agency conference with a CBT focus seems to improve understanding and confidence in professionals working with hoarding problems.

-

(2) Professionals provided a range of suggested improvements which serve as a useful guide to clinicians working in this field. Most commonly cited improvements included working more closely and improving communication with other agencies.

-

(3) People with personal experience of hoarding problems suggested a range of improvements across three over-arching themes: developing an improved understanding of hoarding, the need for improved resources, and improved multi-agency working.

Data availability statement

Data and questionnaires are available upon reasonable request to author P.S.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Buckinghamshire and Milton Keynes hoarding support group and professionals from all organisations for their participation in this research.

Author contributions

Sam French: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (lead), Resources (lead), Software (equal), Visualization (equal), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead); Karen Lock: Conceptualization (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Resources (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Tiago Zortea: Data curation (supporting), Formal analysis (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Validation (supporting), Visualization (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Elaine Hassall: Conceptualization (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Resources (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Victoria Bream: Conceptualization (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Kathryn Webb: Formal analysis (supporting), Validation (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Paul Salkovskis: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (supporting), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Software (equal), Supervision (lead), Visualization (equal), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting).

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

Professor Paul Salkovskis is Editor of tCBT’s sister journal, Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy.

Ethical standards

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. All participants were informed and gave consent that their responses may be used for research purposes. This project was considered to meet criteria for service evaluation, delivered as part of usual practice, and therefore did not meet the NHS Health Research Authority’s definition of research requiring research ethics committee review (NHS Health Research Authority, 2013). The research was approved by an internal committee within The Oxford Institute of Clinical Psychology Training and Research.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.