Introduction

In 2015, a conference at a luxury hotel in Dubai welcomed over two hundred guests for a series of panels on the international mobility of people and money. Tax advisors discussed the implications of sharia law on investment structures, bureaucrats outlined recent changes in migration policies, lawyers reviewed the latest in anti-money laundering regulations, a marketing expert offered tips on branding corporations and countries, and real estate developers pitched investment opportunities in hotel projects. Some in the audience—professionals similar to those on stage—appeared tired, either jet lagged or recovering from the previous night’s reception. There they had witnessed a tribute to the charitable giving of the conference’s main sponsor: donations to the UNHCR to facilitate the production of identity documents for refugee populations. Outside the ballroom, around a dozen businesses had set up tables to advertise condo projects, insurance options, and background investigation services. Though a busy site for networking, this holding area drained when the headline speaker took to the podium. The Prime Minister of a small island gathered all eyes as he pitched his country: “It’s a safe haven to invest in and to reach other destinations,” where people combine “an Anglo-Saxon work ethic with a Mediterranean lifestyle.” Investors could expect to be part of a “small and exclusive program” aimed at attracting “only the best of the best.” What was the product on offer? Citizenship.

How does a sovereign function, such as granting citizenship, become marketized? Like government debt and flags of convenience, citizenship too, though issued through sovereign prerogative, can be bought and sold. Over the past ten years a substantial industry has grown around—and pushed forward—the market in multiple citizenships. In 2012, two countries offered formalized citizenship by investment programs; by 2020, they numbered around a dozen, and several more are in consultations to adopt the tool. Yet it is challenging to grasp this development through standard economic sociology assumptions about the relationship between states and markets. When a traded good is a sovereign prerogative, the state becomes not only the rule-maker of the market, but also the sole direct producer of the product, raising questions about the legitimacy and credibility that market actors must manage.Footnote 1 Given these challenges, the proliferation of formal investment citizenship schemes is a productive area for enhancing our understanding of state-market relations and revisiting conventional assumptions about citizenship.

This article advances a novel account of how sovereign prerogatives are brought to market by analyzing citizenship by investment. First, I identify the challenges of commodifying sovereign privileges. Notably, the state is the sole producer of the good, as well as the key rule-maker of the market—multiple roles that generate conflicts of interest. For sovereigns alone, this matters little but, once credibility becomes a concern, states address the issue by (1) creating a division of labor in product-production, and (2) outsourcing elements of supervision to third-party actors. The case of citizenship highlights these challenges. Conventional accounts of citizenship focus on what it gains its holder within a state—effectively the difference between citizens and non-citizens. But as a commodity in its current form, citizenship’s value is determined primarily by what it gains an incumbent outside the state through extra-territorial privileges. As a result, third countries can curtail its worth, rendering crucial the credibility of such programs in the eyes of third powers.

Focusing on supply [for demand, see Surak Reference Surak2020b], this study draws on three years of fieldwork to offer the first analysis of citizenship by investment programs not only on paper but also in practice. Service providers retooled murky discretionary grants of citizenship in peripheral countries into formal citizenship by investment schemes, which could be offered as mobility planning tools alongside the investment residence programs available in global core countries. They established a clearly defined division of labor and an extended application process that distanced the grant of citizenship from the office of the executive, formalizing the procedure. The result enhanced the viability and credibility of the programs to other market actors, enabling the programs to grow. The conclusion addresses how these mechanisms apply in the markets for other sovereign prerogatives, and government debt in particular, and discusses the implications for our understandings of citizenship and neoliberalism.

Investment Citizenship and its Limits

Sketching the Phenomenon

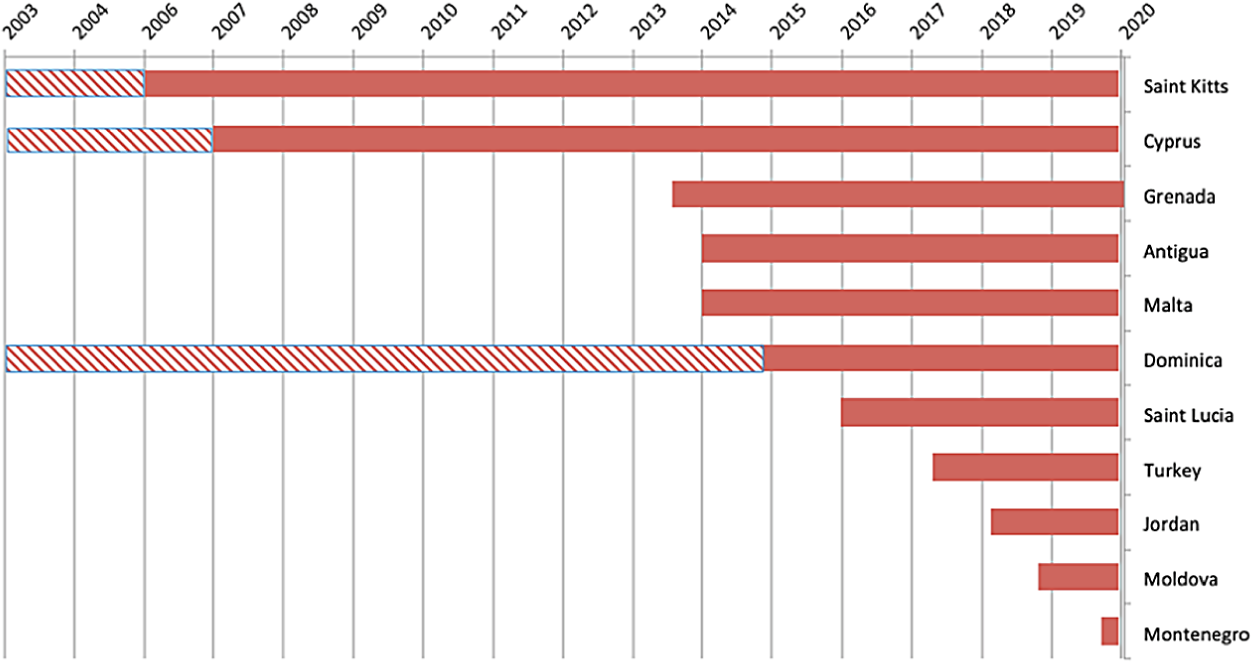

Due to the novelty of citizenship by investment, I will first introduce the phenomenon, as well as the general contours of supply and demand. Citizenship in the contemporary world is a sovereign prerogative—the domaine réservé of states—as the dearth of regulatory provisions in international law attests (see de Groot and Vonk Reference De Groot and Vonk2016). In addition to ascribing citizenship at birth, states can admit members through naturalization. Economic contributions are one option within the common array of over two dozen grounds for doing so.Footnote 2 The extension of citizenship on economic grounds may be made on an exceptional basis, as when New Zealand granted membership to Peter Thiel after he purchased several luxury properties and donated to an earthquake relief fund. Citizenship by investment programs, however, stand in contrast to such discretionary grants, for they provide a clearly delineated, relatively swift route to applying for citizenship outright in exchange for a defined financial contribution. The timeframe, cost schedule, investment options, application procedures, and due diligence expectations are plainly specified in a publicly available policy, transparent and formal, that can be replicated. Unlike investor visa programs, also known as “golden visa” schemes, the intermediary step of legal permanent residence is eliminated or reduced to bureaucratic box-ticking.Footnote 3 Several Caribbean countries offer formal citizenship by investment options, along with Cyprus and Malta in the Mediterranean, Jordan and Turkey in the Middle East, and Moldova and Montenegro in the former Soviet space (see Figure 1).Footnote 4 Typically, licensed service providers and international due diligence firms are involved in implementing the programs. Qualification is usually dependent on an investment in a specified project, monetary contribution to the government, or a combination of the two, and the minimum cost ranges from around $100,000 to $2.5 million, plus fees.

Figure 1 Citizenship by investment programs by date of launch*

*Shaded areas indicate discretionary economic citizenship options.

Exact numbers of naturalizations via citizenship by investment are difficult to deduce: many countries are reluctant to release statistics, and the figures in government reports do not always align with those announced publicly by officials. Based on government sources, newspaper reports, and interviews, I estimate that, by 2019, countries were approving nearly 14,000 applications per year (Figure 2). As family members can be included when filing, the actual number of naturalizations is significantly higher. According to government reports, Malta sees an average of 2.56 family members added to each application, and Grenada sees 2.03. As such, it is likely that, in 2019 alone, approximately 20,000 individuals gained citizenship in the Caribbean, 3000 in the Mediterranean EU countries, and 16,000 in the Middle East through these programs.

Figure 2 Approved citizenship by investment applications

SOURCES:

Antigua: Citizenship by Investment Unit Reports

Cyprus: Cyprus Daily Mail newspaper

Dominica: National Gazette, statements by officials

Grenada: Citizenship by Investment Unit Reports

Jordan: Jordan Times newspaper

Malta: Immigrant Investor Program Reports

Saint Lucia: Saint Lucia Star newspaper

Saint Kitts: Prime Minister’s Report to the National Assembly, statements by officials

Turkey: Hürriyet Daily newspaper, statements by officials

These figures may appear derisory in comparison to the world’s population, but their significance increases when placed in context. First, naturalization is not common. In the absence of comprehensive statistics, a sense of its rarity can be gleaned from the cases where one might expect to find it: countries with large migrant populations. The United States, the world’s greatest recipient of international migrants, naturalizes around 750,000 people per year, or about 0.25% of its population. The next five largest migrant-receiving countries––Saudi Arabia, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United Arab Emirates–– naturalize a total of approximately 400,000 individuals annually, an even smaller proportion at just 0.12%. The rate is similar to that of the EU member states, where liberal democratic norms, if uneven, may make for more open naturalization policies.

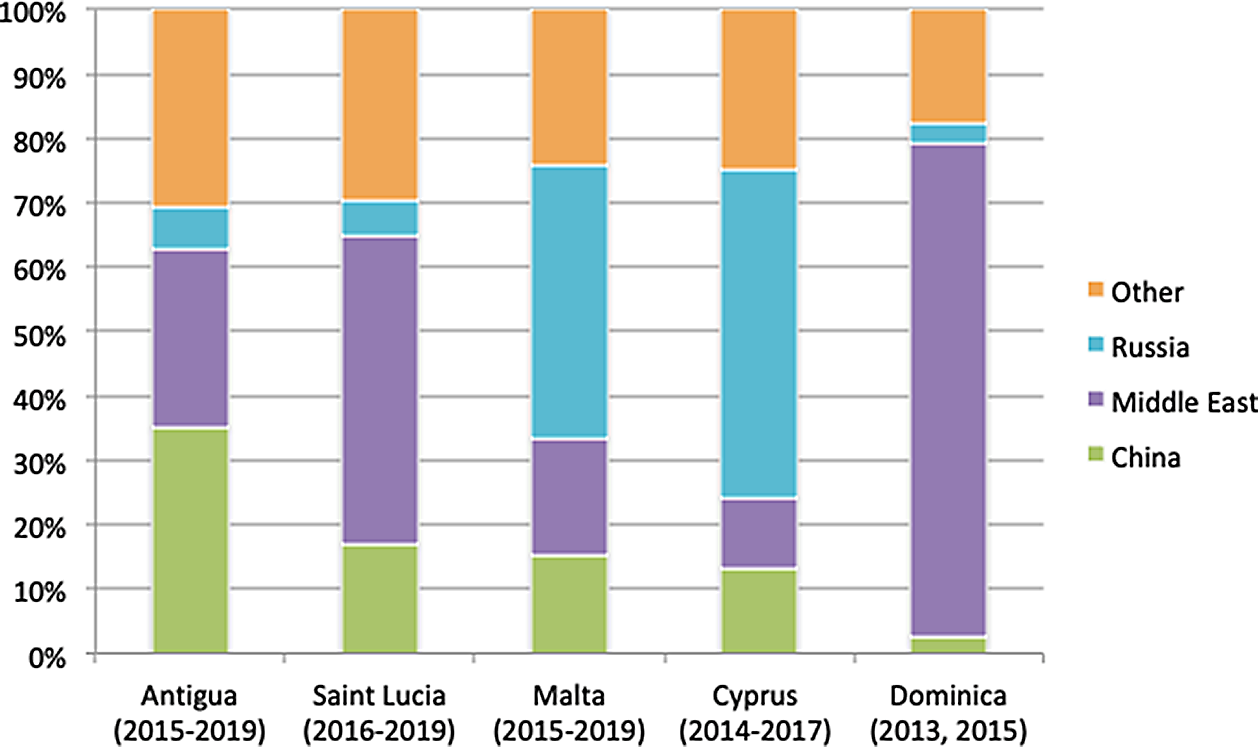

Second, the population of people likely to participate in citizenship by investment programs is relatively small. As shown in Figure 3, demand comes largely from three areas––China, the Middle East, and Russia—areas outside the North Atlantic where economic and geopolitical transformations have produced a growing set of wealthy individuals.

Figure 3 Naturalized main applicants by region of origin

SOURCES:

Antigua: Citizenship by Investment Unit Reports

Cyprus: Cyprus Daily Mail newspaper

Dominica: National Gazette

Malta: Immigrant Investor Program Reports

Saint Lucia: Saint Lucia Star newspaper.

Though interest in citizenship options may be greater, investment migration is not cheap. Service providers confirm that those with a serious interest usually hold at least $5 million in assets and tend to be the first generation in their family to have substantial wealth. Figures estimating the size of this population are imprecise, but wealth reports gesture toward the scale. According to Credit Suisse Research Institute [2018: 16], over 4.3 million “new millionaires” have emerged outside North America and Europe since 2000. This generous appraisal should be significantly trimmed, however, as the global population of those with at least $5 million in assets is one-tenth the size of that in the $1 million to $5 million band [Capgemini 2018: 11], yielding a population of around 430,000 that may be interested in and able to afford such options. These broad-brush estimates point in the same direction as the limited survey data available. Based on interviews with 500 private bankers and wealth advisors, KnightFrank [2018] reported that 34% of individuals with at least $30 million in assets hold more than one citizenship, and a further 29% are thinking of acquiring an additional one.

Connecting supply and demand is a diverse and competitive migration industry of service providers who convert the economic capital of the wealthy into benefits provided by states. Despite the popular image that elites possess the discretion of seamless movement and expansive rights, carte blanche does not come freely: flattening borders demands substantial work. As Bourdieu [Reference Bourdieu and Richardson1986] emphasizes, the conversion of capital requires expenditure, which become the profits of the migration industry that has flourished as the critical middlemen of elite mobility. To understand the micro-mechanics of how the wealthy leverage their superior position on the scale of economic inequality to overcome the limits of particular citizenships requires analyzing the creative and connective function of this migration industry [see Surak Reference Surak2022].

Citizenship Between States and Markets

This bare-bones sketch of supply and demand tells us little of how a market in citizenship operates in practice. Economists working on the issue have concentrated on the potential for market mechanisms to efficiently screen people for membership in a nation [Borna and Stearns Reference Borna and Stearns2002, Becker Reference Becker Gary, Becker and Becker1998: 58-59; see also Hidalgo Reference Hidalgo2016]. Differences come down to program design: whether citizenship is best distributed through auctions [Simon Reference Simon Julian1989], floating price systems [Chiswick Reference Chiswick Barry and Chiswick1982], direct trades [Johnson Reference Johnson2018], or other means. Yet in these accounts, the market remains an abstract mechanism for allocating naturalizers to countries that functions in a vacuum beyond interstate relations, specific “product” characteristics, and a distinctive historical backdrop. It tells us little about the origins or spread of these schemes, the structure of supply and demand, the conditions under which countries might start such programs, or the production of value.

To address these issues requires, in the first instance, unpacking the relationship between states––the producers of citizenship—and markets, a topic long central to economic sociology. Within this field, a broad group of scholars working in a neo-institutionalist mode views the state as a market-enabler: it sets the rules that structure the market and facilitates play within it [Fligstein Reference Fligstein2001; Dobbin Reference Dobbin, Granovetter and Swedberg2001; Krippner Reference Krippner Greta2012]. Its regulations may affect the type of producers in the market, the forms of competition among them [Roy Reference Roy William1999; Polanyi Reference Polanyi2001; Beckert Reference Beckert2009], and their possibilities of failure [Carruthers and Halliday Reference Carruthers Bruce and Halliday1998], as well as the kinds of goods available and how they are exchanged, whether legally [Fligstein Reference Fligstein1993; Ingram and Rao Reference Ingram and Rao2004; Healy Reference Healy Kieran2006; Quinn Reference Quinn2008], or illegally [Beckert and Dewey Reference Beckert and Dewey2017]. Though the state may provide the backing that sustains trust between market actors [Heimer Reference Heimer Carol1985], it is itself never disinterested and may be persuaded by market actors to alter the rules in their favor [Drutman Reference Drutman2015]. States may serve not only as the guardians of markets, but also their fallouts, and can shield populaces from their worst effects by compensating for market failures [Polanyi Reference Polanyi2001; Crouch Reference Crouch2011].

Where neo-institutionalist approaches have taught us much about the state’s role in shaping and sustaining markets, debates around neoliberal transformations have underscored the changing relationship between them. Early research questioned whether the state has ceded too much—or not enough—control to markets [Strange Reference Strange1988; Becker and Becker Reference Becker Gary, Becker and Becker1998]. More recently, analysts have focused on how the political sphere itself has become colonized and re-written by market logics [Harvey Reference Harvey2007; Ong Reference Ong2006; Somers Reference Somers Margaret2008; Brown Reference Browne Gaston2016]. One outcome is the contractualization of membership as neoliberal transformations rework what were once guaranteed rights into a privilege secured through quid pro quo exchanges [Somers Reference Somers Margaret2008]. States increasingly turn to private actors to supply once taken-for-granted social support programs, while individuals are expected to become more enterprising and entrepreneurial in structuring their lives [Ong Reference Ong2006]. The result is that people have become more reliant on markets, putatively efficient but often biased, to secure their life chances [Peck Reference Peck2001].

Similar concerns motivate much social science and normative-theoretical scholarship on the sale of citizenship. Several authors diagnose investment citizenship as a symptom of broader neoliberalizing trends that blur the boundary between states and markets [Boatcă Reference Boatcă2015; Mavelli Reference Mavelli2018; Shachar Reference Shachar2018]. Some maintain that it is the active, entrepreneurial state that adopts programs to enhance financial competitiveness [Mavelli Reference Mavelli2018] as governments contend to attract capital [Parker Reference Parker2017]. Others argue that, in contrast, the state falls victim to private interests as companies invade and establish programs [Dzankic Reference Dzankic2012; Carrera Reference Carrera2014; Grell-Brisk Reference Grell-Brisk2018], ultimately undercutting the state’s domain [Shachar Reference Shachar2018]. Scholars propose that states with such naturalization channels will increasingly apply economic logics toward their populaces in a range of areas [Shachar Reference Shachar, Shachar, Bauböck, Bloemraad and Vink2017, Reference Shachar2018]. The effects are predicted either to erode the state’s political power and independence [Krakat Reference Krakat Michael2018] or to transform its behavior as it concentrates efforts to sustain the market and promote competitiveness [Mavelli Reference Mavelli2018].

Whether they view the state as facilitating, capitulating to, or being recast by markets, neither the neo-institutionalist nor neoliberal perspectives explain the dynamics involved when the state takes a sovereign prerogative to market. Here the state wears two hats, as both the sole direct producer of the product and the ultimate rule-maker, which presents challenges to conventional assumptions that a separation of these roles mitigates conflicts of interest and stabilizes transactions. In the case of sovereign debt, for example, the possibility of default without compensation remains a looming risk because sovereign immunity greatly limits the available mechanisms for enforcing payments or seizing assets. Governments can also influence macroeconomic indicators, making it difficult for creditors to verify the level of economic health [Aguiar and Amador Reference Aguiar and Amador2013]. To protect against such threats and secure liquidity, intermediaries with separate reputational risks enter into the transaction, a role that banks and corporations have historically played [Carruthers and Stinchcombe Reference Carruthers Bruce and Stinchcombe1999; Flandreau and Flores Reference Flandreau and Flores2009].

More recently, the financialization of sovereign debt has re-enlivened concerns about the actions of states in markets that trade in sovereign prerogatives [Bruner and Abdelal 2005; Fastenrath et al. Reference Fastenrath, Schwan and Trampusch2017]. Tracing the Israeli case, Livne and Yonay [Reference Livne and Yonay2016] point to the tensions that emerge when the state moves from issuing debt through negotiated deals behind closed doors to relying on financial markets. In the process, the state begins to react as homo economicus, pursuing its own financial benefit even as it serves as the key market regulator. The result of the conflicting roles is a “Janus-faced” agency—that of sovereign and market actor—as the state balances conflicting interests [Livne and Yonay Reference Livne and Yonay2016: 340, 359; see also Trampusch Reference Trampusch2019]. The authors let the observation stand as symptomatic of neoliberalization in order to explore other questions; they do not highlight how it challenges market-making itself or probe how it is resolved to the satisfaction of other market actors, enabling business to continue. However, they trace two developments in their paper that offer clues: the establishment of a separate unit, autonomous from politics, to handle the transactions, and the reliance on professional third-party debt managers in issuance. These trends are not limited to the Israeli case they focus on, but can be found across the OECD [Fastenrath et al. Reference Fastenrath, Schwan and Trampusch2017], and suggest mechanisms that the state might employ to secure legitimacy by creating distance between its conflicting roles and reducing “the multiple-hat problem” to a sufficient degree for markets to operate.

Unpacking Citizenship as a Commodity

To dissect the dynamics of the citizenship market, we need also to know how citizenship operates in commodity form and its impact on market formation. First to note is the dual role of the state, discussed above.Footnote 5 The state’s multiple roles have at times yielded ethically questionable, yet entirely legal, cases of countries selling citizenship to criminals. Imelda Marcos, who traveled on Vanuatuan documents [Van Fossen 2007], and Japanese Mafia boss Tadamasa Goto, who became Cambodian for a fee, are just two examples.

Product differentiation also marks citizenship as a commodity: not all versions are equal. The use-value of citizenship can be regarded as the rights and privileges it offers its holder. Historically, the benefits of citizenship within the granting state have received the most attention, a predisposition that dates as far back as T. H. Marshall’s [Reference Marshall1950] canonical analysis of citizenship and the gradual accretion of rights. But the utility of citizenship does not end at the national border: citizenship secures benefits outside a state as well. Reputation plays no small part: people with more prestigious citizenships benefit when abroad from the stature accorded to their associated state—and vice versa. States also have a duty to safeguard their citizens away from home, with protection offered at embassies worldwide. For global movers, however, of more immediate concern is visa-free access [see also Surak Reference Surak2020b]. On this measure, the most powerful passports, such as those from Germany and Japan, allow their holders to enter over 190 countries without requiring a visa in advance; the worst, Iraq and Afghanistan, will grant access to less than 30. Of course, not all countries are equally desired—for most people, easy entry to the United States is worth far more than entry to Tuvalu, as the Quality of Nationality Index [Henley & Partners Kochenov Reference Kochenov2019] captures.

More than access to other states, citizenship can secure rights within them [Surak Reference Surak2016; Harpaz Reference Harpaz2019; Dzankic Reference Dzankic2019]. Citizens of regional groups, including the European Union (EU), Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Caribbean Community and Common Market (CARICOM), Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR), Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), and the Nordic Council gain expansive benefits in member countries, which can include investment rights, business ownership, limited franchise, and claims to social welfare provision. Beyond regional clubs, states can negotiate extended rights on a bilateral or multilateral basis. Notable pairings include Switzerland and the European Union, Monaco and France, Lesotho and contemporary South Africa. Such alliances, formed to encourage the free flow of capital and goods in the first instance and labor in the second, operate as federation-like clubs that grant rights and privileges to mobile individuals by virtue of membership, not in the region, but within a constituent country. Thus for an Egyptian, citizenship in Dominica means visa-free access to Europe. For a Burmese businessperson, citizenship in Malta opens investment possibilities in Germany, residence and voting options in the United Kingdom, and visa-free access to the United States. Unsurprisingly, the difference in benefits in this segmented market is reflected in the prices: $100,000 for Dominica and $1 million for Malta. The upshot for the resulting multizens is “citizenship à la carte” [FitzGerald Reference Fitzgerald2006] or “citizenship constellations” [Bauböck Reference Bauböck2010] that allow them to select the best option from an array of membership benefits, or—even better—from improved options in core states [Boatcă Reference Boatcă, Wallerstein, Chase-Dunn and Suter2014]. As a residence-planning tool, citizenship is the right to more rights.

Because the utility of citizenship is determined not only internally, but also externally, the granting government does not retain exclusive control over its value. Foreign states can expand or curtail the worth of another state’s citizenship by altering access to and rights within them. The utility of Polish citizenship, for example, increased substantially when the country joined the EU, reflected in a rise in naturalizations [Harpaz Reference Harpaz2013]. The point is crucial for understanding the market dynamics of citizenship because it gives foreign countries leverage over the value of what is, at heart, a sovereign prerogative. Though a state has the discretion to sell membership, other countries may regard the transaction as dubious, illegitimate, or a security threat, and can react, for example, by removing visa-free access. This indeed occurred when two Iranian businessmen entered Canada on diplomatic passports issued by Saint Kitts—but without diplomatic business—in 2014. Ottawa responded by revoking visa-free access for all Kittitian citizens, resulting in a decline in citizenship sales. As such, we can expect countries that hope to capitalize on the international value of their citizenship and expand market share will look to maintain good relationships with regional powers and seek out strategies to increase credibility and protect “product value.”

Before moving on, a caveat is needed to clarify two related concerns. First, dual citizenship laws, though they can facilitate the packaging, purchase, and use of a second passport, do not determine outright whether or not citizenship is bought and sold [cf. Veteto Reference Veteto2014]. Despite prohibitions on dual citizenship, China is home to the largest consumer market for second passports [Surak Reference Surak2020b]. Much of the Middle East too, with similar bans, remains a key source region, especially among the ultra wealthy. If demand is not blocked, neither is supply. Liechtenstein, for example, proscribed dual citizenship during the years it operated its “fiscal naturalization” option. Notably, though, it did not require proof in all instances that the prior membership had been renounced [Schwalbach Reference Schwalbach2013].

Second, it is important to note that the discussion thus far has focused on the rights and benefits—but not duties—of citizenship. The omission is deliberate: key obligations typically fall on all individuals resident or present in a territory, not merely on its citizens. Income taxes are levied on resident foreigners and nationals alike, and even short-term visitors pay sales tax. With the decline of conscription armies, military service is no longer expected of most national populations and, in many places, foreigners can find employment in the armed defenses—and sometimes receive postmortem citizenship if killed in the line of duty. In the United States, only jury duty remains entirely in the hands of citizens—and even then with the qualification that service is obligatory only if resident in the country [Spiro Reference Spiro Peter2008: 97-99]. The shift has been long in the making. Over 65 years ago, T. H. Marshall [Reference Marshall1950: 9, 77-80] observed that, on balance, the rights of citizenship were superseding its duties, a trend that appears durable.

Within the duties often associated with citizenship, tax bears special mention as many presume that tax evasion or avoidance is a key attraction of citizenship by investment. The reality, however, is more complicated. Many countries where demand originates have long been comparatively inefficient when collecting income taxes and often have low income tax rates in the first place. Though some tax benefits may accrue to new citizens—such as inheritance tax benefits and the reduction of import taxes to third countries—these are not a key factor driving demand globally [see Surak Reference Surak and Fassin2020a, Reference Surak2020b]. Indeed, most wealth structuring and tax evasion happens readily without these tools [see Harrington Reference Harrington2016]. Notably, all of the traditional countries of citizenship by investment analyzed here also have a financial service industry—a legacy of British rule as newly independent microstates sought to capitalize on the conveniences of the common law provisions they inherited, a strategy that London encouraged [see Palan, Murphy and Chavagneux 2010; Ogle Reference Ogle2020]. The link between offshore financial centers and the sale of citizenship, however, is not direct. The biggest, most important offshore locations are in substantial and powerful countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland [Bullough Reference Bullough2018; see also the Global Financial Centres IndexFootnote 6]. Furthermore, highly specialized and high-volume offshore hubs, like the Cayman Islands and the British Virgin Islands, are dependent territories, which cannot sell citizenship. The Financial Secrecy Index by the Tax Justice Network ranks countries based on the scale of their offshore financial activities and secrecy, yet countries offering citizenship by investment fail to stand out. The highest ranked is Malta, which appears at number 18, between Thailand and Canada.Footnote 7 To the extent that there is a connection between citizenship by investment and offshore finance, it is largely through network advantages. Service providers who work in wealth structuring are connected to the wealthy individuals (if often via other service providers) who may desire a second citizenship.

Methods

This investigation draws on a larger body of primary and secondary sources collected on investment migration. For over a decade, actors in the business of residence planning have hosted industry conferences on citizenship by investment. From 2015 to 2018, I participated in twenty major conferences and two information sessions in London, Zurich, Geneva, Monaco, Sveti Stefan (Montenegro), Athens, Moscow, Dubai, Frigate Bay (Saint Kitts), Bangkok, Shanghai, and Hong Kong. Hosted by leading service providers in the industry, the conferences lasted two to three days and offered a valuable overview of industry trends. Over three years, I spoke with more than 350 people involved in all aspects of the industry, including lawyers, bureaucrats, due diligence providers, real estate developers, and personal wealth managers. The interactions ranged from ten-minute targeted chats to longer discussions lasting several hours, as well as multiple meetings.

To understand the industry outside the space dominated by international firms, as well as the history of the programs and how they operate on the ground, I conducted fieldwork in countries with citizenship by investment programs including Antigua (Reference Browne Gaston2016), Saint Kitts (2016, 2018), Cyprus (Reference Cyprus2018), and Malta (2018). In all countries, I visited government offices, service providers, and real estate developments, as well as talked to locals about their impressions of the program. In key hubs, including London, Dubai, New York, Montreal, Moscow, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Hong Kong, I conducted over 100 interviews typically lasting between thirty minutes and two hours with industry players, including lawyers, service providers, bureaucrats, government ministers, due diligence providers, real estate developers, and private wealth managers. I also conducted 16 interviews with individuals who had become investor citizens or residents, or were shopping for options.

To substantiate and expand on the interviews, I collected information from the available primary and secondary sources on investment migration, which included government documents, government reports, third-party reports, and newspaper articles. Interviews and secondary sources sometimes contained spin or conflicting accounts. I therefore triangulated the information obtained to improve the accuracy and reliability of the findings, supplying new details about and corrections to official narratives. I also point the reader toward publicly available primary and secondary sources where they confirm the information gathered through interviews.

The Emergence of Citizenship by Investment

The mechanics that enable the market around investor citizenship are best understood by comparing citizenship by investment programs to cases where such formal programs are absent, namely the discretionary grant of economic citizenship. These channels also enable citizenship to be exchanged for financial contributions, but through a less formal system that operates without clearly defined expectations or external oversight [Surak Reference Surak2016]. Such grants can be extended in an individualized manner, as when Angelina Jolie was granted citizenship in Cambodia in recognition of her charitable work, or they can be unconnected to individualized characteristics and occur on a wider basis. It is the latter—a depersonalized sale—that is of interest here as it facilitates marketization.

Discretionary economic citizenship sales spread as a revenue source among small countries from the early 1980s when microstates in the Pacific, including Nauru, Tonga, Vanuatu, Samoa, and the Marshall Islands, began selling both passports of convenience and full citizenship to Chinese clients seeking greater freedom of travel and wealth protection. Between 1982 and 2002, an estimated 14,000 passports of Pacific microstates were purchased for $4,000 to $50,000 each [Van Fossen 2007: 140-141]. Tonga is indicative of the trend. In 1984 the government amended the Nationality Act to grant the King full discretion to naturalize foreigners. Middlemen opened offices in Hong Kong and elsewhere and sold an estimated 8,000 passports, largely outside the knowledge of the Tongan Immigration Office [South China Morning Post 1991]. Though the Act was found unconstitutional in 1988, sales continued. By 1991, an overseas trust fund, outside ordinary public accounting, held over $20 million in proceeds from the sales in a San Francisco bank account, with reports of much higher figures hidden elsewhere [Los Angeles Times 1991]. As information spread, public outrage and unprecedented mass street protests eventually forced the Prime Minister to resign. Across the region, the largely secretive sales were defined by ambiguity and absence of background checks—a number of international criminals have been found carrying Nauran and Tongan documents, and thousands of passports remain unaccounted for [Van Fossen 2007].

During this time, the bulk of sales remained in the Pacific, though several countries in the Caribbean and Central America joined the ranks of those offering sought-after state membership. As early as 1983, the Prime Minister of Dominica undertook trips to Hong Kong where she advertised the discretionary authority of the minister holding the immigration portfolio to grant citizenship in exchange for financial investments [South China Morning Post 1983], a practice the country regularized by 1993. Saint Kitts, a year after receiving independence from the United Kingdom, included a channel for jus pecuniae in its 1984 Citizenship Act. Uptake, however, remained limited, and those I interviewed who were involved with the program at the time aver that only a few dozen passports were issued to investor citizens each year. Processing was also informal and blank passports circulated to figures involved in criminal activities [Bullough Reference Bullough2018].

Ireland, too, opened a pathway in 1989 by broadly interpreting Article 16(a) of its Nationality and Citizenship act to include financial investments as sufficient to fulfill the requirement of “Irish descent or Irish association.” The government did not publicly announce the expanded channel or its specifics, and its implementation was marked by arbitrariness. In 1998, it closed the channel following controversy and reports of fraud [Assembly of Ireland 1998]. As Parliamentarian Feargal Quinn described it:

The scheme was apparently perfectly legal in that it broke no law, but the basis for it was not set down either in the form of legislation or a ministerial order. It worked entirely within the scope of the discretion available to the Minister of the day under the nationality and citizenship legislation. It came into being with an informality that is quite staggering, particularly in view of the importance of the issues involved. There seemed to have been no rules governing the scheme at all. A number of unofficial rules were applied later, but these made no difference. It is a matter of record that little or no effort was made to keep to those rules or to discover whether they were being observed

[Senate of Ireland 2002].Clearly, too, it was the passport rather than citizenship that was most often on sale. If a program went under, or was axed after a change of party in power, the new government would either declare the citizenships null and void or would not renew the passports, effectively invalidating the membership. According to service providers operating at the time, there was little guarantee that the countries would continue to recognize the citizenship status of clients. As one based in London described, “officials might sell them and then the next regime would come along and cancel all of them, saying that they didn’t follow the statutory procedures.” In addition, there was no question that the status would not be passed down to future generations. One Europe-based intermediary I interviewed described the schemes at the time as “quasi-official”; as another put it, the scene was “under the radar,” without many taking notice. Another at a global accountancy noted, “They weren’t seen as programs back in the day. They were seen as shady,” adding that even minimal due diligence was lacking. In some places, overseas consulates sold passports without the full recognition of the issuing government and unclear interactions among its ministries—a situation that ended in scandal for the Lesotho Consulate in Hong Kong [South China Morning Post 1992]. The discretionary channels remained murky and insecure, without a transparent process, external oversight, and a division of labor to separate vested interests and ensure solidity.

In the main, numbers for these opaque options remained small and programs short-lived. Ireland for example, naturalized only 156 individuals over ten years [Assembly of Ireland 1998]. Volumes in the Pacific were greater, but the channels were more unstable. The Marshall Islands sold 2,000 passports, but operated a program for only one year; Vanuatu issued 300 over a similarly short-lived scheme. Nauru’s option was open for four years and naturalized 1,000 individuals [Van Fossen 2007: 141]. According to service providers operating at the time, there was little guarantee that the countries would continue to recognize the citizenship status of clients. As one based in London described, if a program closed or a new regime was elected, the government might simply “cancel all of them” by fiat. This occurred when Grenada, under US pressure, closed its channel in 2001. The state could not be trusted.

Yet more stable examples were available in global core countries, albeit offering not citizenship but residence by investment: investors still had to spend several years on permanent resident status before they could be naturalized. Canada set the pace when it reworked its Business Immigration Program, launched in 1978, into the Federal Immigrant Investor Program (FIIP) in 1986. No longer was active involvement in running a business required, as with entrepreneurial schemes; applicants could simply make a passive investment of CA$150,000 (increased to CA$250,000 in 1988 and eventually to CA$800,000) and in exchange receive a conditional residence visa that became permanent residence after three years. Financial contributions went into an approved business or a government-administered venture capital fund. Private actors organized the paperwork and investment options, regional governments selected the applicants, and the central government gave the final approval. The banks involved in the transfer of funds were responsible for ensuring that the money arose from legitimate means and adhered to securities legislation. Problems remained, but these centered mainly on unscrupulous intermediaries bilking money from investors [e.g. DeRosa Reference DeRosa1995; Steier Reference Steier1998], rather than the credibility of the program itself, which was structured by a standardized, transparent process involving multiple actors and oversight points. For market actors, there was little doubt that the program was solid and that the state would follow through. As a Dubai-based service provider described his motivation for selecting it at the time, it was “the most transparent and smoothly running” program.

Notably, major law firms and banks with sizeable legal departments assessing risk, along with migration service providers, found Canada’s program viable enough to offer it to their broad base of clients. Where only a few hundred individuals made use of the entrepreneurial Business Immigration Program, numbers soared to the thousands annually under the new passive investment scheme, driven by demand from Hong Kong and Taiwan [Citizenship and Immigration Canada 2003:11].Footnote 8 Within a few years, the United States and the United Kingdom followed suit with, respectively, the EB-5 program in 1990 and the Tier 1 Investor Visa program in 1994. Other countries, including New Zealand, Australia, and Singapore developed or elaborated programs along similar lines, diversifying the options that international law firms, banks, and private wealth managers could offer.

Program Formalization

Murky discretionary economic citizenship channels on the periphery and formal residence by investment programs in the global core readied the ground for citizenship by investment schemes. Saint Kitts was the pioneer. Since 1984, the country possessed a law enabling citizenship to be granted in exchange for investment in real estate or government bonds. Yet, as described above, numbers remained small and the program shrouded in secrecy and questionable practices. As a London-based service provider who assisted clients with the option in the 1990s described, “it was opaque, like a lot of the programs then.” This changed in 2006 when the government took guidance from the residency planning firm Henley & Partners—which previously advised clients about tax planning and residence options in Europe—to expand its economic citizenship stream into a marketable citizenship by investment program.

Scaling up required formalization, including the elaboration of a more transparent process with oversight and a separation of interests through a division of labor. Under Henley’s advice, the government undertook a series of reforms. It moved from a minimal three-page application to a more lengthy and detailed form that was more in line with international standards, and it included tighter screening of health, criminal activities, and the source of funds. The government created a dedicated “Economic Citizenship Processing Unit” (now Citizenship Investment Unit (CIU)) under the Ministry of Finance to handle applicant screenings and approvals. My archival works shows that it set an official timeframe for assessing applications and guidelines for communication to improve processing. To manage the flow of money, it established the Sugar Industry Diversification Fund (SIDF), a private entity, to monitor and distribute government donations. And to “enhanc[e] its reputation and minimize[e] any possible risk,” it called for tighter due diligence procedures (Cabinet Submission No. 195/2006). As a due diligence professional working in the scene in the early 2000s put it, the governments at that point claimed they were doing background checks, “but they weren’t doing much.” Under criticism from the United States over possible money laundering, the Kittitian government suspended the government bond option and established two qualifying investment possibilities: a contribution of $250,000 to the SIDF, or the purchase of $400,000 in approved real estate projects, in addition to what would become approximately $60,000 in processing fees, contingent on the number of family members naturalizing (Cabinet Submission No. 195/2006).

The government contracted Henley & Partners to check applications and promote the program internationally, for it doubted that it had the infrastructural capacity to reach a substantial client base alone (Cabinet Submission No. 195/2006). In exchange, the firm received a commission of 10% of every contribution to the SIDF. In 2007, Henley & Partners hosted its first international conference to tout the program, which soon appeared among the financial planning tools on offer at large multinational banks. The company also lobbied Members of the European Parliament to grant Saint Kitts visa-free access to the Schengen area. By 2012, the government added an additional layer of screening by appointing a dedicated international due diligence firm to carry out background checks.

The result of the formalization process was a scalable product and a revenue-generating success. What had been a murky channel was now a clearer process, and a far more transparent one, structured by a division of labor, involving third-party oversight, and appeasing regional powers to a sufficient degree.Footnote 9 In 2009, the country gained visa-free access to the Schengen Zone, which proved a boon to the program.Footnote 10 Thereafter a Kittitian passport would allow its bearer smoother mobility within Europe than a Russian or Chinese equivalent. My interviews with financial planners and legal advisors at major international banks and accounting firms reveal that they began pairing Kittitian passports with Canadian investor visas to guarantee their clients easy access to Europe while they waited for citizenship in Canada. The results for Saint Kitts were stunning. In 2006, program receipts constituted about 1% of the country’s GDP; by 2015 the figure rose to over 35% [Abrahamian Reference Abrahamian2015: 80]. Today, the program’s processing fees alone account for a quarter of the government’s recurrent revenue [Saint Christopher and Nevis Budget Address 2019: 8]. The steady growth seen over the past decade dropped slightly in 2015 after Saint Kitts lost visa-free access to Canada following a scandal involving diplomatic passports (see figure 4). However, with naturalization rates for investor citizens several times higher than those of its neighbors, the country still leads the Caribbean programs.

Figure 4 Saint Kitts: annual citizenship by investment applications

SOURCE: The Prime Minister’s Report to the National Assembly.

The formalized scheme, championed by service providers, spread quickly in a region of microstates with little economic potential beyond tourism. As one lawyer in Saint Kitts complained, “We gave Henley exclusivity, but they didn’t give it to us.” Antigua followed the Kittitian model in 2013, offering a similar array of options: $250,000 to a national development fund (quickly lowered to $200,000), $400,000 invested in real estate, or a pooled investment of $1.5 million in a local business. Initially it took guidance from Henley & Partners, but broke with the firm—and its 10% fee for marketing—shortly before the program launched. Applications are handled by thirty local service providers, licensed yearly, which process the papers before turning them over to the CIU, while international due diligence firms carry out background checks on the candidates. As in Saint Kitts, the government channels real estate investments into one of forty approved development projects. In 2013, Grenada established a program similar to its neighbors, requiring a $200,000 donation to a government trust or a $500,000 investment in real estate to qualify. By 2014, Dominica reformed its long-standing economic citizenship channel to offer a range of comparable options under a new CIU, and Saint Lucia announced a new program in 2016, following established lines. Industry actors involved affirm that the anticipation of visa-free access to the EU, known around a year in advance, was a driver behind the reforms, as governments and private actors hoped to capitalize on this key source of citizenship’s “product value” that lies outside the granting state.

Amidst these transformations, it was crucial to maintain credibility in the eyes of Global North powers, for the EU held the key to value and the US had a history of shutting down programs in the region for final approval. To ensure this—and to guard against security risks to “international partners”—countries began to run their lists of applicants on the cusp of approval past the US presence in the region for final approval. They also launched the Citizenship by Investment Programs Association (CIPA) in 2015 to organize regular meetings with “stakeholders,” including representatives from the United States, Canada, and the IMF, in order to share best practices, develop strategies to sustain the schemes, and ensure the toleration of regional powers.

During these years, the Mediterranean also became a center for sales, with not merely access to the Schengen Area, but EU citizenship itself at stake. In the early 2000s, Cyprus offered economic citizenship on a discretionary basis for around €25 million, aimed at a small set of investors with pre-existing economic interests in the country. According to officials, the impetus was to ensure that those with assets in Cyprus would keep them in Cyprus. By 2007, it began to formalize the channel by adjusting its Civil Registry Laws to lower the minimum price point to €17 million and introducing a range of qualifying investment channels, a process that came into full form with further reforms in 2011. When the global economic crisis hit Cyprus’s financial sector and restricted the state’s access to global money markets, the citizenship stream was retooled into a larger, money-generating program aimed at attracting foreign direct investment and facilitating state borrowing through government bonds. The scheme specified a package of investment options, including businesses, bonds, and real estate, and set a clear price, initially €10 million, followed by drops to €5 million, €3 million, and €2.5 million, to arrive at a minimum investment of €2 million. Though no physical presence is required after filing the application (initially everything could be done overseas), investors must maintain a residence worth at least €500,000 to retain citizenship. Following the financial “haircut” in 2013, Cyprus offered those who lost more than €3 million in deposits the opportunity to apply for citizenship as well.

Yet Cyprus has not escaped criticism from the EU. The troika of the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund raised queries about the program in 2018, in addition to regular criticism from the European Parliament. Notably, the EU has no legal mechanisms for influencing the naturalization policies of members states. However, Cyprus responded to concerns in 2019 by instituting greater oversight and new divisions of labor: it lengthened the application process, established a supervision committee, outsourced government-level due diligence to international firms, created a registry of service providers and required them to carry out due diligence checks on clients, and required real estate developers to operate separately from program marketers.

Even with more hoops to pass, demand still continued to rise. In 2014, the country approved 214 applications in total, and by 2019 its annual cap of 700 was reached by October [Cyprus Mail Reference Cyprus2018; Kathimerini Cyprus 2019]. With major international accounting firms processing over one quarter of the files [Cyprus Mail Reference Cyprus2018], no longer was Cyprus’s scheme an individualized program for the select few. Formalization, too, made the status more resilient. When Cyprus attempted to revoke the citizenships of 26 investor citizens in 2020 over irregularities in the application process and faulty due diligence, it ran into legal challenges that still remain tied up in the courts—a situation quite different to the wholesale revocation of investor naturalizations by Vanuatu in the 1990s and Grenada in 2001.

Malta, too, faced similar challenges from the European Union when introducing its program. In 2013, a newly elected Labour government suddenly announced plans for a citizenship by investment program and awarded the contract to Henley & Partners. In the initial design, investors could apply for citizenship based on a donation of €650,000 to a government fund and applications would be processed within six months. However, the opposition party pushed back and catapulted the debate into the European Parliament. For the Parliament, this was a new area of concern: in 2011, the Commissioner for Justice had dismissed discussion Cyprus’s program as outside the EU’s purview since citizenship is a “competence” of member states, not the EU.Footnote 11 But two years later, the same Justice Commissioner, extending the Union’s reach into a new domain, took up the question of Malta’s program. Championing it was a former Member of the European Parliament (MEP) who had led the Nationalist Party, long in power, to defeat against Labour in Malta’s 2013 general elections. In the new venue of debate, criticism was sharp. The European Commission and European Parliament raised concerns over the practice in general, as well as conflicts of interest in due diligence checks, leading to a substantial reformulation of program requirements. The ensuing reforms were tailored to assuage the European Commission’s concerns that investor citizens lack a “genuine connection” to the country and address apprehensions about the independence of due diligence processes. In addition to the government donation, applicants under the revised scheme needed to buy or rent property of a minimum value and invest in a government-approved local enterprise, raising the total price to around €1 million. The application process was extended from six months to one year, and required the naturalizer to intend to make Malta her new home. An ombudsman was appointed to carry out annual reviews of the program, producing a publicly available report. Even with the adjustments, the program, limited to 1,800 main applicants and expected to generate over €2 billion, far exceeded initial expectations of 100 to 200 new citizens each year: within the first 18 months the government received over 400 applications representing over 1,000 main applicants and family members [Office of the Regulator 2014: 22, Office of the Regulator 2015: 6]. By summer 2020, it had reached the cap and stopped accepting submissions.

Transformations across all cases have brought transparency, divisions of labor, and third-party oversight, increasing the credibility of the programs for market actors. A partner at a major international accounting firm encapsulated the shift from discretionary channels to formal schemes at a presentation in 2015. In the late 1990s, a long-time client asked about purchasing an additional passport from the Caribbean. Unfamiliar with shadowy business, she conducted a risk analysis, which threw up red flags. A fact-finding mission left her just as mystified: no public information was available, the steps were unclear, and it was impossible to determine how much was paid to whom. “There was no transparency,” she said. Five days later, and under international pressure, the island closed its channel for selling citizenship. But much has changed since, she stated. “All the things that were so wrong then are so good now.” When the same client recently approached her again about the programs, she was able to offer an array options, some with solid investment opportunities, and none raised the risk flags of the firm’s legal division. The change in stance on the programs is not unusual. Indeed by the 2010s, the London branches of three of the Big Four accounting firms deemed the now formalized programs credible enough to regularly assist clients with investment-based naturalization. A former Swiss banker described the shift in legitimacy: ten or fifteen years ago if a client came in with a Saint Kitts passport to open a bank account, no one knew where it was and they wouldn’t do it. “Now all the compliance departments know all about it, and know where the islands are.” A service provider in London captured the transition from the 1990s to the present: “They didn’t have a dedicated team like the CIU… they didn’t have a system of licensed agents. That’s all a lot more transparent now.”

Yet the proliferation of citizenship by investment schemes has not gone undisputed by actors who have an interest in the market but remain outside its core operation. As discussed above, regional players like the European Union and the United States have actively pressured countries by closing down discretionary channels or pushing for the revision of formal programs. The European Union in particular has taken a strong stance against the programs within its purview, though it has not, for example, revoked visa-free access to the Caribbean countries offering such schemes—a move that would greatly cut demand for their offerings. The United States has also made no direct moves against the current programs—even though it could revoke visa-free access for Maltese citizens, and even though it has shut down programs in the past. Taken as a whole, there has been more passive—though not complete—toleration than in comparison to the interventions of the past.

Challenges can arise within states as well. Opposition parties often liken the programs to cash cows for the party in power, and the local media may attack governments for carelessly prostituting the nation or siphoning funds from the programs. In election years, investor citizenship programs are always a hot-button issue. Yet despite several regime changes in recent years—the opposition won elections in Grenada and Cyprus in 2013, Antigua in 2014, Saint Kitts in 2015, and Saint Lucia in 2016—no newly elected party has implemented pre-election promises to end the programs that have become a vital source of revenue. Public opinion ranges from supportive to critical [Surak Reference Surak2022], yet the programs have not attracted large-scale demonstrations targeted specifically at citizenship programs of the sort witnessed in Tonga.Footnote 12 Thus even if legitimacy is not complete, it is still sufficient for the market to operate.

Now that citizenship by investment is an established policy concept, larger states have begun their own programs. In 2018, Turkey, Jordan, and Moldova opened or relaunched citizenship by investment schemes. A cursory examination of these infant programs suggests that the field may be diversifying into new domains. Turkey opened a legal channel in 2016 in a bid to revive the housing and construction sector, but received a negligible number of applicants. In 2018, it dropped the minimum investment from $1 million to $250,000 and reportedly received over 250 applications in the first seven months [Hürriyet Daily News 2019], with individuals from Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan showing the greatest interest [Pitel Reference Pitel2019]. According to service providers working with the program, driving demand are wealthy people from the region who have moved base to Turkey—a center point of refugees—as a result of political pressure or turmoil at home. By the close of 2019, its popularity was soaring: according to statements from the Ministry of the Interior, over 5000 individuals had naturalized and up to 9000 applications were pending. Jordan, too, opened a program in 2018 that focuses on wealthy expats with a base in the country [Royal News 2018]. In the first seven months, it saw over 100 applications submitted and at least 15 approvals [Ghazal Reference Ghazal2018]. With citizenship by investment now an established form, these much larger states, borrowing from their neighbors, show greater independence from established service providers in the development and marketing of their programs, which are aimed at a different consumer base: wealthy, displaced foreigners with a degree of presence in the country. Though assessment of such young programs in rapid transition is difficult, these new developments suggest that the market in citizenship by investment may be further segmenting to include also options where rights secured within the granting state are considered as valuable as those granted by third countries.

Finally, legitimacy can be lost as well. In October 2020, undercover reporters for Al Jazeera broke a story that exposed high-ranking politicians in Cyprus facilitating a special citizenship “solution” for a bogus Chinese businessman with a criminal record. The report revealed a two-track operation. Corrupt politicians would facilitate naturalization on a case-by-case basis, circumventing the official procedures and bureaucratic vetting—for a very hefty price. That is, alongside the formal program, there was a discretionary route that took the applications straight to the government’s executive branch, the Council of Ministers, for approval. The revelation led the government to suspend the citizenship by investment option and incurred further demands from Brussels to end the scheme.Footnote 13 It also brought the long-standing program into great public debate within Cyprus for the first time, as high-profile politicians faced corruption allegations. Yet the scandal did little to quell interest among buyers. The program’s final weeks saw over 400 new applications—nearly a dozen each day—arrive at the Ministry of Interior.Footnote 14 On November 1, the government suspended the program and launched an investigation that is still underway. The events lend support to the argument advanced here about the crucial role of bureaucratic divisions of labor and third-party vetting in securing credibility. When such mechanisms are circumvented through payoffs, the result can severely damage the reputation of a program, particularly in the eyes of powerful third-party actors, as well as civil society, resulting in its closure.

Conclusion

This article unpacked the dynamics of marketizing sovereign prerogatives and showed how states address concomitant multiple-hat problems. In these cases, the state does not merely structure the market, but also serves as the sole direct producer of the product, a configuration that generates conflicts of interest and raises credibility issues that produce risk for other market actors. Revealing the workings of the “Janus-faced” state observed by Livne and Yonay [Reference Livne and Yonay2016; see also Trampusch Reference Trampusch2019: 4], it showed that these concerns are addressed by developing an extended issuance process involving a division of labor and oversight by third-party actors.

In the case of citizenship by investment, it showed that far greater complexity defines the citizenship market than characterizations of “brute and unfettered cash-for-passport exchanges” [Shachar and Hirschl Reference Shachar and Bauböck2014: 246] or of mere neoliberal transformations [Boatcă Reference Boatcă, Wallerstein, Chase-Dunn and Suter2014, Reference Boatcă2015; Mavelli Reference Mavelli2018; Shachar Reference Shachar2018, Parker Reference Parker2017] would suggest. Its rise can be explained only by disaggregating the field into attendant offerings. The spread of discretionary economic citizenship channels in the periphery and formal residence by investment programs in the global core supplied the material that dominant consultancies could retool into citizenship by investment programs. To formalize investor citizenship into a scalable product, they established a division of labor and extended application procedure, including third-party oversight, that distanced the grant of citizenship from the office of the executive. Formalization also meant that states could no longer easily cancel the status en masse—they could be held to account. States continued to revise programs along these lines when addressing concerns raised by regional powers. The result was a more transparent process—one that was no longer seen as “quasi-official” or as raising warning flags for risk divisions at multinationals—that enabled market expansion.

The solutions arrived at when building a market around the sovereign prerogative of citizenship can also be found in both early issuances of sovereign debt and more recent cases. As with citizenship, the state wears multiple hats as both key market regulator and sole direct producer of the good, raising questions of credibility and reliability, particularly against sovereign default. To solve the dilemma in 18th century London, joint-stock companies became involved in the issuance of government bonds. The reputation of these third-party actors, which effectively sold sovereign debt, was the vital indication to investors that the deal was solid and they would be repaid [Carruthers and Stinchcombe Reference Carruthers Bruce and Stinchcombe1999: 370-374]. By the 19th century, buyers offered premiums for “big name” underwriters—firms that would have more to lose if their brand were sullied by sovereign default—to certify the debt and guarantee the return [Flandreau et al. Reference Flandreau, Flores, Gaillard and Nieto-Parra2009, Flandreau and Flores Reference Flandreau and Flores2009]. Today credit rating agencies perform a similar function, evaluating a state’s ability to make good on a loan and indicating the riskiness of default [Bruner and Abdelal 2005; Fourcade Reference Fourcade, Morgan and Orloff2017]. Divisions of labor also mitigate conflicts of interest that arise from the multiple hat problem. States today, for example, commonly establish debt management offices that separate debt management from monetary policy, which could be used to lower the amount owed through inflation [Trampusch Reference Trampusch2019]. Divisions of labor in the surrounding environment also bolster integrity: countries with checks and balances, as well as independent judiciaries, are deemed more creditworthy than others [Biglaiser and Staats Reference Biglaiser and Staats2012; Saiegh Reference Saiegh2009]. Where the executive issues citizenship directly, without an extended process, one can expect legitimacy to be compromised.

Is the state’s reliance on private actors in these cases symptomatic of growing neoliberalization? The long history of third-party involvement in sovereign debt issuance suggests that more is going on. The commodification of sovereign prerogatives is a specific form of state-market interpenetration in which governments are not merely involved in structuring the market [see Hockett and Omarova Reference Hockett and Omarova2014] or incorporating market forces into modes of governance [Harvey Reference Harvey2007; Ong Reference Ong2006; Somers Reference Somers Margaret2008; Brown Reference Browne Gaston2016], but are the sole direct producer of the good traded on the market, and therefore, as has been shown here, reliant on third parties for credibility. Private actors may simply facilitate market development, or they may drive it, with the latter characteristic of neoliberalization. Yet no matter the degree of cooperation or cooptation, the sovereign remains the seat of rule and sole product-producer across cases: in the contemporary world, only a state can issue citizenship. Still private actors play a critical role in enabling the market to operate. This co-dependence is markedly apparent in, for example, how states respond to statements by credit rating agencies, even adjusting economic policy to improve rankings [Fourcade Reference Fourcade, Morgan and Orloff2017: 117]. In effect, these actors transfer their own credibility to the sovereign, but are able to do so precisely because states “deputize” them in the first place.

The analysis also suggests ways to rethink common understandings of citizenship. Conventional accounts regard citizenship in terms of the rights it gains incumbents within a state. In contrast, citizenship by investment throws into relief the privileges it secures outside a state [see also Surak Reference Surak2016; Harpaz Reference Harpaz2019]. Although citizenship attribution is a domaine réservé of the state, this extra-territorial dimension provides foreign states with leverage over citizenship programs. The analysis illuminates two ways in which third parties wield influence over citizenship policies, an outcome favored by the characteristics of citizenship as a commodity. International service providers proactively craft policy templates and advise governments, pushing the industry forward. Furthermore, global core states and regional alliances wield reactive influence over the design, implementation, and existence of programs. As such, citizenship policy is more susceptible to external influence than is often presumed. Not merely a politics of legitimacy but a geopolitics of legitimacy—ensuring that more powerful third-states countenance the offerings and are involved in program operation—is required to secure the market and ensure its continued operation. To the growing literature on migration industries, the outcomes show that not merely immigration policy, but citizenship policy too, is subject to the broader trend toward public-private partnerships.

If the trends to date hold, we can expect to see citizenship by investment programs spread to new states, championed by global service providers. The most probable targets are fully independent microstates with limited income sources. They are more likely both to look beyond traditional revenue streams to secure foreign exchange and investment, and to reap significant economic benefits from such programs. Countries with a mixture of civil and common law elements in their legal system—a combination that feeds offshore financial centers—are more susceptible to such programs as they will already have links to the lawyers, private wealth managers, and accountants that service the affluent and provide auxiliary assistance with the implications of additional citizenships for wealth structuring. Yet now that the concept and format have become established, larger countries, as seen with Turkey, may increasingly implement these programs, either as a means to capitalize on wealthy foreigners within their borders or an additional lure to attract new capital injections.