‘The European Parliament … Calls for the European Union … to utilise all its diplomatic weight and to mobilise the EU delegations, not only in New York and Geneva, but also in other key countries, notably developing countries, whose effective participation in the process is of critical importance …, and should be facilitated by the EU, in order to ensure the success of the process.’ (European Parliament resolution of 18 April 2018 on progress on the UN Global Compacts for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration and on Refugees, 2018/2642(RSP))

1 Introduction

The EU portrays itself as a major global actor in migration. The EU pursues such ambitions in the UN context as well, despite not being a UN member (only enjoying an ‘enhanced observer’ status).Footnote 1 Recent examples of its role as an active player in global migration governance include its contribution to the UN International Law Commission (ILC)'s work on the expulsion of aliens (Molnár, Reference Molnár2017); the conclusion of an increasing number of readmission agreements and arrangements with third countriesFootnote 2 (for the informal readmission-related EU arrangements with third countries, see Cassarino, Reference Cassarino2020); and its ever-closer co-operation with the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (Beqiraj et al., Reference Beqiraj, Gauci, Khalfaoui, Wessel and Odermatt2019) as well as other international organisations dealing with migration management.Footnote 3 Although not a stateFootnote 4 but still a ‘regional integration organisation’, the EU's prominent role in migration issues has been acknowledged, to some extent, by the international community, in a policy field that is fairly state-centric and where state sovereignty's bridgeheads remain strong.

This paper seeks to scrutinise the EU's role and impact during the preparatory and inter-governmental talks (including the ‘consultation’ and ‘stocktaking’ phases) leading to the adoption of the UN Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular MigrationFootnote 5 (‘Global Compact for Migration’ or ‘GCM’) in December 2018. The central question is the degree to which the EU influenced negotiations and their outcome; and how international partners, primarily UN Member States, understood and received – or criticised and opposed – the EU's external action in this matter. Next to mapping the EU's substantive input and arguments shaping the negotiation process and the content of the Compact, the EU's internal machinery and intricacies involved in formulating its common position, as well as the challenges faced within the bloc, including the absence of unity, are also briefly explored. These challenges stem from the catchall material scope of the GCM, which covers diverse subject matters falling under EU exclusive, shared, and pure Member State competences (see also e.g. García Andrade, Reference García2018).Footnote 6

The paper first provides a brief introduction to the GCM (Section 2), followed by a discussion of the EU's procedural standing in the process, as well as internal EU co-ordination to formulate its own position and a brief outline of the EU's contribution (Section 3). Section 4 attempts to measure the EU's actual impact on the Compact, while flagging some challenges in exploring the views of the ‘rest of the world’ on EU external action in this matter. This case-study illustrates the willingness of the international community – or the lack of it – to elevate European values and normative standards to the global level, in the highly complex and politicised domain of migration management. Section 5 formulates some conclusions and presents an outlook for the future.

2 The Global Compact for Migration: a new instrument on the bloc

Piecing together as well as clarifying and consolidating rules and principles in quite heterogeneous fields of international law has recently become a popular standard-setting approach under the UN aegis. ‘Defragging international law’ (Yong, Reference Yong2018), to use the metaphor of ‘defragging’ computer programs consolidating fragmented files on a hard drive, has also been sought by the Global Pact on the Environment,Footnote 7 similar to the Global Compact for Migration (Gombeer et al., Reference Gombeer2019).

The GCM's symbolic power as a universal instrument has raised expectations that it might embody potential responses to the fragmentation of the international legal regime governing international movement of people. Notwithstanding its non-legally binding (‘soft-law’) nature, it may impact existing rules of international law and affect the legal position of migrants under international law. Peters has summarised the functions and possible legal effects of the GCM as ‘pre-law’ (a forerunner of hard law, paving the way for a formal treaty); ‘para-law’ (substituting missing hard law); and possibly serving as a guideline for the interpretation of hard law, fleshing out hard-law commitments and making them more concrete (‘law-plus function’) (Peters, Reference Peters2018). Others identified similar functions of the agreed commitments (e.g. Labayle, Reference Labayle2019, p. 254). Chetail underscores that the document does not create new norms, but restates and reinforces existing international legal standards (Chetail, Reference Chetail2019, pp. 334–335). Further legal scholarship has analysed its legal nature and contribution to international (migration) law (e.g. Bufalini, Reference Bufalini2019; Gavouneli, Reference Gavouneli2019; Labayle, Reference Labayle2019). What is clear is that states’ commitment to international law radiates through the document: respect for international law in general and human rights law in particular is mentioned fifty-six times across the text (calculated by Chetail, Reference Chetail2019, p. 334). This reaffirmation underscores the continuing centrality of international law to governing the diverse phenomenon of migration across borders.

The GCM set up various fora and mechanisms to support and monitor the implementation of the commitments set out therein and to review the document if need be (paras 40–54; further detail in Guild and Basaran, Reference Guild and Basaran2019). It established a capacity-building mechanism including a ‘connection hub’ facilitating demand-driven, tailor-made and integrated solutions, and a start-up fund, called a Migration Multi-Partner Trust Fund,Footnote 8 complemented by an online global knowledge platform. In line with the UN Secretary-General's decision, the GCM also endorsed the creation of the UN Network on Migration replacing the Global Migration Group (GMG),Footnote 9 which aims to ensure effective and coherent system-wide support for implementation, including the capacity-building mechanism, as well as follow-up and review of the Global Compact, while being fully aligned with existing co-ordination mechanisms and the repositioning of the UN development system (GCM, para. 45). The IOM serves as the co-ordinator and secretariat of the Network. The UN Secretary-General, drawing on the Network, is tasked with reporting to the General Assembly (UNGA) on a biennial basis concerning the implementation of the Compact and the activities of the UN system in this regard (GCM, para. 46). In addition, the Compact invited

‘the Global Forum on Migration and Development [GFMD], regional consultative processes and other global, regional and subregional forums to provide platforms to exchange experiences on [its] implementation … share good practices on policies and cooperation, promote innovative approaches, and foster multi-stakeholder partnerships around specific policy issues.’ (GCM, para. 47)

The EU is thus also an addressee of the above call. Beginning in 2022 and meeting every four years, the International Migration Review ForumFootnote 10 (IMRF) will serve as the primary inter-governmental global platform for UN Member States to discuss and share progress in implementing the Compact, which will result in an inter-governmentally agreed Progress Declaration (GCM, para. 49). In the interim, the GFMD will provide the space for an annual informal exchange on migration in a global context, channelling the issues, best practices and innovative approaches discussed there to the IMRF (GCM, para. 50).

3 EU input to the Global Compact for Migration: from the consultation phase to the Marrakech Intergovernmental Conference

3.1 The EU's procedural standing in the GCM process: a view from the UN

After committing itself and its Member States to the GCM in 2017,Footnote 11 the EU became heavily engaged in the process of elaboration. Indeed, under the European Commission's 2017 annual work programme, the Directorate-General for International Cooperation and Development earmarked €1.7 million to support the migration compact (Apap, Reference Apap2019, p. 7). The EU's self-asserted leading role in the process was strengthened by the US's withdrawal from negotiations in December 2017,Footnote 12 even though, on some occasions, the EU struggled to speak with one voice, primarily due to one single EU country having vetoed the common EU position from 2018 onwards (see Section 3.2 below).

The April 2017 Modalities for the inter-governmental negotiations of the GCM,Footnote 13 setting out the three phases of the process elaborating the GCM, did not assign a key role to international organisations, the EU included, although the preparatory talks did show a greater openness to involvement of non-state entities than other UN conferences had done in the past. Subsequently, the December 2017 Modalities for the Intergovernmental Conference to adopt the GCM, amended in August 2018, displayed greater inclusiveness, expressly granting the EU, as a regional group, standing status to participate in the final (formal) stage of bringing about the GCM.Footnote 14

At the Marrakech Intergovernmental Conference, the EU participated as an observer pursuant to the modalities set forth earlier by the UNGA, which assigned to it an elevated formal standing, including the right to speak – with special rules on its statements – and the right to reply, as well as representation in the Main Committee as the lone non-state entity. Still, formally speaking, the EU was one amongst other inter-governmental organisations present, including the African Union, the Council of Europe and the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD). The extended EU delegation to the conference, led by the Commissioner for Migration and Home Affairs, included Commission/European External Action Service officials and several Members of the European Parliament (MEPs)Footnote 15 and actively took part in the debates, making several general statements.Footnote 16 Given the rather formal nature of the inter-governmental event, which essentially rubber-stamped the agreed text, statements of this kind could not – and actually did not aim to – shape the outcome document, which was now considered to be final and not open for further amendments. Nonetheless, the size and the composition of the EU delegation boosted the EU's international visibility and lent it symbolic power through the magnifying glass of the Marrakech Conference.

It is important to note, however, that, in accordance with the modalities laid down by the UNGA, only the ‘states’ participating in the Marrakech Intergovernmental Conference were entitled to vote on the outcome document.Footnote 17 The EU's ‘enhanced observer’ status did not grant the regional bloc the right to vote, but only the right to speak at this high-level event of multilateral diplomacy. Therefore, the EU could not officially endorse the outcome document in Marrakech or afterwards at the UNGA in New York.

In spite of all the formal, procedural constraints and internal hiccups in formulating its own position (as discussed in the next subsection), the EU strived to exercise a tangible influence from the consultation (preparatory) phase, through the stocktaking phase and during the inter-governmental negotiations starting with the ‘zero draft’ until the December 2018 Marrakech Intergovernmental Conference.

3.2 Formulating and representing a common EU position in the process of elaborating the GCM

This section provides a chronological overview of how the EU formulated and represented its own position vis-à-vis the GCM. In the course of the so-called ‘consultation phase’ (phase I), which started in spring 2017, the European External Action Service made statements on behalf of the EU – based on guidelines commonly agreed by the UN Working Party (CONUN) and the High-Level Working Party on Migration and Asylum (HLWG) of the EU CouncilFootnote 18 – at a series of informal thematic sessions organised at different UN headquarters across the globe by the co-facilitators of the preparatory process.Footnote 19 These structured consultations with active EU involvement began with the thematic session on the human rights of all migrants (May 2017)Footnote 20 and included a session addressing drivers of migration (May 2017),Footnote 21 a session focusing on international co-operation and migration governance (June 2017),Footnote 22 as well as preparatory events on the contribution of migrants and diasporas (July 2017),Footnote 23 on the smuggling of migrants and trafficking in human beings (September 2017)Footnote 24 and on irregular migration and regular pathways, including labour mobility (October 2017).Footnote 25

The EU also substantially contributed to the stocktaking phase (phase II), which assessed and compiled the wide-ranging inputs received during the consultation phase. This second phase culminated in a high-level meeting held in December 2017 in Mexico where the UN Secretary-General presented a report, Making Migration Work for All,Footnote 26 to take stock and to provide states with recommendations before the beginning of the inter-governmental negotiations. The EU input to phase II resembled an ‘alternative (mini-)summary’ of the proceedings thus far, geared towards its preferences. It covered a wide range of issues, from the desired non-binding legal nature of the outcome document through setting out priorities, to be accompanied by result-oriented and actionable commitments, to the establishment of a dedicated follow-up and review mechanism of the implementation of the action-oriented commitments.Footnote 27 Many of these were reiterated by the EU Statement during the debate of the UN Secretary-General's above report in the UNGA at the beginning of 2018.Footnote 28

The third and final phase comprised the stricto sensu inter-governmental negotiations. These commenced in early 2018 with a ‘zero draft’ of the GCM as a basis, discussed thereafter in six rounds of closed-doors inter-governmental talks, at the end of which an inter-governmental conference was convened in Marrakech (Morocco) on 10–11 December 2018 to formally adopt the GCM. This traditional inter-governmental phase, the terrain of classic multilateral diplomacy, was steered by the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for International Migration, who also acted later as the Secretary-General of the Marrakech Conference.Footnote 29

Unlike the negotiations of international treaties by the EU that are governed by Article 218 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) (for a detailed and recent analysis, see Heliskoski, Reference Heliskoski2020), the negotiations of international soft-law instruments are not regulated by a clear EU legal framework (Melin, Reference Melin2019, p. 214; Wessel, Reference Wessel2020, pp. 5–6), though the CJEU has provided some guidance.Footnote 30 Using the existing grey zones in EU law, the European Commission presented, soon after the ‘zero draft plus’ had been published in March 2018, two proposals of identical substance – owing to different legal bases under the EU treaties – for Council decisions. These proposals intended to provide for exceptional, ‘well-in-advance’ authorisation from the Council for the Commission to approve the GCM on behalf of the EU at the end of the process.Footnote 31 Seemingly, the Commission wanted to secure its mandate not only in respect of the approval of the instrument, but also for the negotiations of the text. In the words of the proposals, the aim of the authorisation to be given to the Commission – which represents the EU's supranational interests and not those of the Member States – was to ensure a unified EU approach. Likewise, the proposals also aimed to ensure that the Compact was consistent with the EU acquis and policy in this domain, as well as the foreign-policy objective of multilateralism.Footnote 32 However, due to one EU Member State's stark disagreementFootnote 33 and legal concerns raised by the Council Legal Service about the ‘two-in-one’ nature of the authorisation sought, the Council of the EU ultimately did not adopt the aforementioned proposals aimed at authorising the Commission to approve the GCM on behalf of the EU (see also Melin, Reference Melin2019, p. 214).Footnote 34

Despite these political (and legal) controversies impeding the formal adoption of an EU position in the last phase of the process, EU co-ordinated statements – delivered by the rotating Presidency of the EU Council – continued to provide input and influenced the rounds of negotiations conducted in 2018 to reach agreement on the text. This EU input was informed by an EU Framework Document, prepared within the Council but officially never approved, outlining the main objectives of the EU and its Member States throughout the negotiations phase.Footnote 35 This co-ordination tool, providing a strategic steer for the negotiations, set out the main goals that the EU aimed to achieve and the main aspects that should be included in and omitted from the final version of the text. The Draft EU Framework Document also indicated, whenever possible, relevant EU acquis and policy documents that EU negotiators should use for justifying EU proposals or for seeking alternative formulations in the text. Yet again, due to the lack of consensus within the Council, this ‘lines-to-take’ document was never formally approved. Reflecting on the lack of its official endorsement, commentators differ on whether the EU was speaking with one voice during the phase of inter-governmental negotiations (February–July 2018). In Melin's view, the EU Statement of May 2018 adopted on behalf of twenty-seven EU Member States suggests that the EU lacked a common position during the negotiations phase (Melin, Reference Melin2018). In contrast, Gatti argues that it demonstrates that the EU did have a common position until May 2018 (Gatti, Reference Gatti2018). I share the latter standpoint, given that previous EU statements were indeed adopted on behalf of all EU Member States, including Hungary. At the end of February 2018, Hungary even protested against that externally represented unity.Footnote 36 As a result, it appears that a common EU position existed between 2017 and May 2018, but then Hungary openly dissociated from it for political reasons.Footnote 37

3.3 A snapshot of the EU's substantive contribution to the GCM process

Turning to the substantive contribution that the EU made throughout the whole process of elaborating the GCM, I start with three preliminary remarks. The first concerns the nature of the statements and contributions that – due to the political character of the Compact – were not primarily legalistic, but predominantly used policy language. This predetermines the depth and elaboration of the EU's legal input, which were thus not articulated in fully accurate legal terms and arguments.

The second general observation is that the aforementioned Draft EU Framework Document, in spite of its lack of formal authority, still served as a central resource to inform the EU position and statements that indicated a strong desire to keep the standards and commitments in the GCM strictly within the boundaries of existing EU acquis. The EU thereby sought to ensure the greatest coherence of this UN compilation with the existing EU migration acquis, taking also into account the importance of not prejudging ongoing EU negotiations and future developments of EU law in this area.

Third, and more broadly, instead of coming up with proposals to progressively develop international migration law, EU positions centred rather on restating existing international standards and called for adherence to already agreed legal instruments and principles. This ‘basic regulatory toolkit’, besides norms of customary international law (e.g. mainly in the field of international human rights law), includes the universal and regional treaties on fighting against trafficking in human beings, the UN Protocol against smuggling of migrants, numerous instruments adopted under the aegis of the International Labour Organization (ILO) and various conventions on the law of the sea and international maritime law with respect to search-and-rescue obligations. Developing international law governing migration is typically about extending the rights and entitlements enjoyed by migrants. The EU statements did not go in this direction and essentially aspired to keep the legal-protection regime as it is (Baretto Maia et al., Reference Baretto, Morales and Cetra2018). Positioned as a leader in global migration governance, the EU's ambitions to set new standards were well below the expectations of many stakeholders and observers.

Following the logic of the Draft EU Framework Document, the main points and priorities that the EU representatives highlighted in relation to the GCM throughout the whole process can be grouped into six thematic clusters. These thematic blocks are as follows: human rights and the protection of migrants in vulnerable situations (related to Objectives 3, 4, 7, 8, 12, 13, 14 and 15); root causes and drivers of migration including climate change, natural disasters and man-made crises (related to Objectives 2 and 19); pathways for legal migration and inclusion policies (related to Objectives 5, 6, 16, 17, 18, 20 and 22); addressing irregular migration, including return and readmission (related to Objectives 9, 10 and 21); governance issues, including border management (related to Objectives 1 and 11); implementation and follow-up; as well as general/cross-cutting aspects, including the GCM's legal nature. The detailed EU priorities, grouped by the above clusters, are set out in Table 1 in Section 4 below. Equally interesting are those issues and actions that the EU did not want to see in the document. These ‘points to avoid’ are presented separately in Table 2.

Table 1. Provisions of the GCM (most likely) reflecting EU influence – by thematic clusters

* = only partially reflecting the EU position; ** = wording (almost) verbatim taken from an EU Statement. Source: Own compilation, based on EU Statement – First Consultation; EU Statement – Second Consultation; EU Statement – Third Consultation; EU Statement – Fourth Consultation; EU Statement – Fifth Consultation; EU Statement – Sixth Consultation; EU Statement – Stocktaking; EU Statement – UNGA Jan. 2018; and EU Framework Document (April 2018).

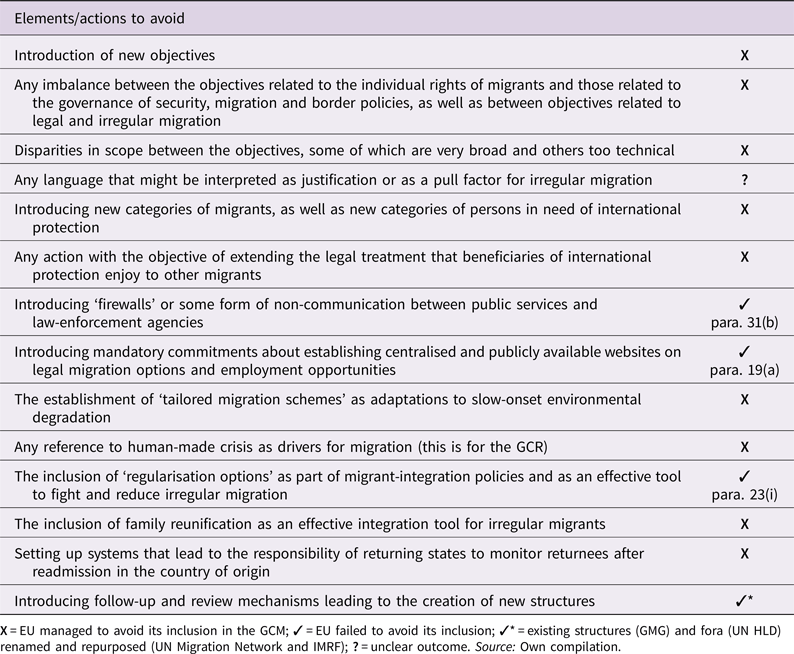

Table 2. Elements/issues that the EU insisted on not including in the GCM

X = EU managed to avoid its inclusion in the GCM; ✓ = EU failed to avoid its inclusion; ✓* = existing structures (GMG) and fora (UN HLD) renamed and repurposed (UN Migration Network and IMRF); ? = unclear outcome. Source: Own compilation.

4 Measuring the EU's actual impact on the Global Compact for Migration: finding proof of ‘dark matter’?

The next step of the analysis is to compare the EU's substantive input to the agreed commitments and concrete actions in the final text of the GCM. This aims to understand to what extent EU priorities made inroads into the outcome document and to which degree the international community welcomed them – the ‘dark-matter’ metaphor will help to elucidate the inherent limitations of this exercise.

It must be noted at the very outset that the official or summary records of the inter-governmental talks (phase III) are not publicly available. This secrecy is contrary to the basic requirement of transparency and public diplomacy, even if negotiating a soft-law UN instrument does not follow the same rules as for UN conventions adopted at diplomatic conferences. Hence, unlike the consultation phase (phase I), which ensured rather transparent proceedings, the inter-governmental talks (phase III) became very non-transparent and were carried out in a way of old-fashioned closed-door diplomacy. Essentially, the only documents available and accessible from the six rounds of inter-governmental talks held between February and July 2018 are the various revised drafts that were produced based on the initial ‘zero draft’ of the GCM. Therefore, no statements, comments or reactions from states made at this stage are publicly available. The internal dynamics and alliances formed during the negotiations, possible package deals as well as answers to the question concerning which issues or suggestions made it or did not make it into the text and for what reasons remain hidden from the outside word.

Therefore, reconstructing states’ and other actors’ particular positions, especially towards the EU policy agenda, as well as the degree of influence that the EU has actually exerted on the content and wording of the final document, is hardly an exact science. Some of the additions to the text during the inter-governmental talks and the final outcome document itself match, to a great degree, what the EU had advocated for. Yet, the aforementioned circumstances constitute limitations in shedding more light on the dynamics between players across the process and on how the international community reacted to EU external action. Due to the publicly non-available nature of UN summary records and other diplomatic preparatory materials during the inter-governmental talks, no direct and official evidence has been at my disposal to understand the approach of the international community towards EU efforts in advancing its own policy agenda. Even though I could gain some insights by conducting background discussions with EU actors involved in the GCM process (who spoke on condition of anonymity), my requests for interviews with representatives of selected ‘third countries’ and UN officials remained unanswered. Many of my findings and conclusions are therefore based on indirect evidence, unofficial summaries of the proceedings and deductions therefrom. That is why this quest was akin to finding (indirect) evidence for the existence of ‘dark matter’.Footnote 38

In this context, the official records of the debates on the draft GCM resolution before the UNGA at the very end of the process during which over fifty UN Member States took the floorFootnote 39 and that include the explanation of votes are valuable indications of UN Member States’ red lines and major concerns, alongside their priorities and preferences. In the absence of more authentic sources that could have been considered as travaux préparatoires, these UNGA Official Records serve as ‘ex post facto mirrors’ to what was most likely said, represented and discussed by certain countries throughout the closed inter-governmental talks. Nonetheless, they do not directly refer to, reflect on or speak to EU proposals either. Such closing statements from UN members address the GCM as a whole, without singling out any particular stakeholder or their priorities. What has been of help, however, is that the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), an independent think-tank, prepared informative summary notes of all six negotiation rounds, which by and large reconstruct the proceedings and states’ positions.Footnote 40 This is thus an alternative source providing valuable insights into the position of states and regional blocks as well as their evolution and the dynamics throughout the talks. In the following, I use these unofficial IISD summaries when assessing the EU's influence on the outcome of the GCM process.

Against this backdrop, Table 1, while not being exhaustive, presents – according to thematic clusters – the identified and, to some degree, corroborated impact of the EU contributions on the adopted final text of the GCM.

The table, read in light of the unofficial summaries of the proceedings prepared by the IISD, clearly displays that EU priorities and suggestions were widely endorsed in the final text of the GCM, in relation to a broad range of issues in which the EU possesses at least shared competence. This success can be at least partially explained by the EU's quite lowered ambitions in terms of standard-setting, sticking mainly to existing international obligations and standards without seeking to go beyond the established legal boundaries. What we cannot say definitively is whether this concordance is mostly thanks to EU efforts and effective external action or whether, for example, other states had similar priorities and advanced them jointly with the EU. For instance, Ferris and Donato (Reference Ferris and Donato2020, p. 116) note that, although some countries opposed including the issue of the consequences of disasters and climate change on migration in the GCM, strong voices from the EU, the Pacific, Africa and Latin America prevailed and the result is a ‘text that reflects a sophisticated understanding of the disaster-migration nexus’ (Kälin, Reference Kälin2018, p. 665). Another similar example is that the EU, alongside Canada, South Africa, Jamaica, Bangladesh, El Salvador and Pakistan, stressed the need for human rights to be respected during the return process.Footnote 41 This dimension, supported by the great majority of delegations, expressly features under Objective 21.

Be that as it may, the adoption of the GCM as an international ‘co-operative framework’ in itself fulfils one overall objective of EU external migration policies, namely to establish a multilateral governance regime for international migration in full co-operation with the UN. A general objective of the EU, namely preventing uncontrolled migration flows while continuing to work towards better management of global migration,Footnote 42 is equally well reflected in the final outcome document. The Compact's legally non-binding character was also achieved, although this was never in question.

Here, I examine three concrete examples from the GCM showcasing the EU's influence. The first is return and readmission (Objective 21), which was a key priority area for the EU since the inception of the process. The EU input on this matter has been considerably reflected in the final text of the GCM, some pieces of which even largely inspired the adopted wording. See, for instance, states’ strongly emphasised responsibility under international law to readmit their own nationals, without any condition, and to enhance their co-operation on readmission. In general, the readmission component under Objective 21 has been expanded, advocated not only by the EU, but also by Australia.Footnote 43 On the other hand, the EU continuously argued until the last stages of inter-governmental talksFootnote 44 for expressly referring to the principle of non-refoulement in the document. An explicit reference featured in the second revised draft (March 2018), but was replaced in the adopted version by a broader commitment. This general formulation forbids returning migrants ‘when there is a real and foreseeable risk of death, torture and other cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment or punishment, or other irreparable harm’ (see also Guild et al., Reference Guild, Basaran and Allinson2019, pp. 43, 50; Majcher, Reference Majcher2018). The reason behind this wording was the lack of agreement between states as to the scope and meaning of this concept as applicable to migrants (beyond the international-refugee-law context) and whether it could be considered as customary international law.Footnote 45 Some delegations, while recognising the concept, did not want to use the expression itself in the text.Footnote 46 Likewise, up to the second revision of the draft, Objective 21 prioritised voluntary return over forced return, which was also strongly supported by the African Group.Footnote 47 As a result of successive modifications, the final text became silent in this regard. Although states should promote voluntary-return schemes (GCM, para. 37(b)), they are not bound to give priority to voluntary return over forcibly returning the person by virtue of the GCM (Majcher, Reference Majcher2018).

The second example concerns immigration detention (Objective 13). A noteworthy change in the text is that the firm commitment to end immigration detention of children (an obligation of result), as contained in the ‘zero draft’ and advocated by the African Group, Latin American countries as well as Bangladesh and the Philippines,Footnote 48 was gradually replaced by the vague formulation of ‘working to end the practice of child detention’ (an obligation of means) (Chetail, Reference Chetail2019, p. 335). This shift reflects the EU position on this matter: never arguing for a complete ban on immigration detention of children, but keeping it as an option in the legal toolbox of national return policies,Footnote 49 albeit subject to a very high threshold of safeguards and limited to exceptional situations. Again, although the official records of the inter-governmental discussions are not publicly available, the changes and the final outcome match what the EU sought to achieve – reflecting thus the tacit agreement of the international community, despite some strong voices criticising the softened language concerning child immigration detention.Footnote 50

The third example relates to pathways for legal migration, specifically academic mobility. The EU negotiators advocated for fostering mobility schemes for students and researchers from the beginning of the process, which finally resulted in a new clause added into the third revised draft (May 2018) as paragraph 21(j) under Objective 5 (Groenendijk, Reference Groenendijk2018). This encourages states to expand existing facilities for academic exchanges such as scholarships for students and academics, visiting professorships, joint training programmes and international research opportunities. The new commitment has not been changed in the subsequent rounds of talks, hence the final outcome closely reflects what the EU sought to achieve in relation to academic mobility.

Besides the EU's achievement of what has been included in the GCM, the flipside of the coin is what the EU was unable to succeed in excluding from the text. Illustrative in this regard is the Draft EU Framework Document (April 2018), which not only set out the priorities, but also identified those issues and actions that the GCM should not contain. These efforts are primarily explained by the EU's endeavours to keep all commitments of the Compact that fall within the purview of EU competences inside the perimeters of the EU migration acquis, so as to avoid additional and possibly conflicting obligations, even in the form of soft law. In this context, the EU paid particular attention to actions pertaining to status determination, issuing of documents, family reunification, immigration detention (including child detention), access to basic public services, as well as access to the labour market and relevant social benefits.Footnote 51 Table 2 outlines what the EU sought to exclude from the text.

When analysing the overview, one can find that the EU was quite successful in keeping certain issues out of the text. Still, a few important commitments and actions that the EU opposed have been retained or finally found their way into the text. These include the establishment of ‘firewalls’ between public services and law-enforcement agencies. An action agreed under Objective 15 requires a prohibition on disclosing the migration status of clients by service providers to immigration authorities, and prohibits immigration authorities from conducting enforcement activities near service locations (Hastie, Reference Hastie2019). Similarly, regularisation timidly but clearly appears under Objective 8 in which states commit to ‘build on existing practices to facilitate access for migrants in an irregular status to an individual assessment that may lead to regular status’ (para. 23(i)). Actions of this kind have been kept in the text most likely due to the strong insistence from countries of origin conscious of upholding the interests of their own nationals if found in an irregular situation in a destination country, notably in the Global North (African Union, 2017, p. 13).Footnote 52 Unfortunately, the absence of publicly available travaux of the inter-governmental negotiations limits the options to accurately identify the actual reasons behind such choices.

Looking at another, not so clear-cut, issue, it is debatable whether the GCM uses language that might be interpreted as justification or a pull factor for irregular migration. One might claim that certain restatements of existing law point in this direction. For instance, the GCM echoes the protective provisions of the 2000 UN Anti-smuggling ProtocolFootnote 53 according to which smuggled migrants cannot become liable to criminal prosecution for the fact of having been the object of smuggling (Art. 5 of the Protocol). However, given that the EU is also party to the UN Anti-smuggling Protocol,Footnote 54 this safeguard is already part of the EU legal order, even trumping any possibly conflicting secondary EU law.Footnote 55 Hence, arguably, there is technically nothing new that would create further incentives to migrate irregularly from the EU perspective.

5 Conclusion

The European Parliament, in its resolution quoted at the beginning of this paper, called for the EU to ‘show leadership in [the GCM] process and … to live up to its responsibility as a global actor and to work to ensure the successful completion of the negotiations’. The preceding tour d'horizon and analysis of the ways and means the EU contributed to the elaboration of the GCM show that this call was not in vain, and underpins the aspiration of this ‘regional integration organisation’ to be a major player in global migration governance. On the one hand, the EU undoubtedly enjoyed a stronger procedural standing than other non-state entities engaged in the process. UN documents clearly articulated that enhanced position. This is noteworthy in the still predominantly state-centred and conservative setting of UN multilateral diplomacy, dealing with a highly politicised and sensitive subject matter like migration. On the other hand, measuring the EU's substantive impact on the Compact is not an easy task, primarily owing to the lack of publicly available travaux préparatoires of the inter-governmental talks (February–July 2018). Consequently, little is officially known about the dynamics of carving out and fixing the objectives, principles, commitments and envisaged actions of this cornerstone UN-level ‘toolkit’ and ‘co-operative framework’ governing migration management. Nonetheless, some unofficial summaries proved to be very useful source materials in unveiling the talks behind closed doors. As the foregoing has revealed, the final outcome document corresponds to and reflects a great number of EU priorities, even echoing the language of EU migration law and policy in respect of certain issues. In a similar vein, the agreed text omits quite a few things that the EU considered undesirable. The EU argued for their non-inclusion, mainly to shield its own existing migration acquis and to keep commitments under the GCM within the realm of its existing international obligations.

A cursory look at these features might prompt the conclusion that the glass is more than half full. Yet, one needs to draw the balance with caution: sights are hindered from the outside as to what the EU has actually achieved during the negotiations and what changes, additions or omissions can be attributed to its efforts made in the arena of multilateral diplomacy. The absence of direct evidence (i.e. official UN records) makes it harder to confirm whether the EU achieved something on its own or whether what seems to be an EU achievement merely coincides with the priorities of other states or regional groups. Ultimately, only indirect evidence and unofficial summaries of the inter-governmental talks were at my disposal to assess the degree of the EU's influence on the final product – akin to finding indirect evidence for the existence of ‘dark matter’. Time might unveil it further. Despite some uncertainties and limits in our knowledge, and the internal challenges for the EU to speak with one voice, I submit in light of the foregoing analysis that the EU has been the most successful advocate of the interests and priorities of the Global North – where the main countries of destination are located – in an attempt to redraw the lines of multilateral migration governance.

Content-wise, however, it is noticeable that the EU's underlying goal was to stick to existing international obligations under both treaty law and customary law, as evidenced by the Draft EU Framework Document and the consistent reference to existing instruments in EU statements throughout the process. All this served to stay on the safe side and to avoid any new international obligations beyond what has already been codified in the EU migration acquis. The EU's relative and visible success in leaving its footprint on this global instrument needs to be nuanced against its ambitions. The EU input throughout the process only satisfied the first limb of Article 3(5) of the Treaty on European Union, which commits the EU in its ‘relations with the wider world’ to ‘uphold and promote its values and interests’. It did not truly endeavour to ‘develop international law’ as articulated in the second limb of the same provision. This is clearly a missed opportunity and a half-hearted operationalisation of this external relations objective of constitutional importance. Presumably, this was the compromise outcome of the EU efforts to find a common position that was acceptable for all Member States on the one hand and the obligation under the EU treaties to develop international law on the other. It seems that the first consideration prevailed over the second in an attempt to find common ground and internal unity. Consequently, the EU failed to use the GCM as an opportunity to further develop international migration law.

What comes next is implementation at all levels (national, regional and universal), the result of which will be fed into and discussed first and foremost in the quadrennial International Migration Review Forum, starting in 2022. Such follow-up and implementation mechanisms are capable of revealing the more precise contours of the positions and priorities of UN Member States, international organisations and other players in the GCM-elaboration process. By the same token, these mechanisms might equally provide post factum insights into how the EU's priorities, preferences and attempts to exert its influence were actually received by the international community when crafting the Compact. Similarly, preparation of the inter-governmentally agreed first Progress Declaration to be adopted by the IMRF in 2022 may open another window of opportunity to better understand in retrospect who wanted to achieve what, why and how in 2018 during the genesis of this roadmap promoting safe, orderly and regular migration.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Acknowledgements

The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views or the position of the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights. The author monitored the elaboration process of the Global Compact for Migration on behalf of the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights but the Agency did not engage in the preparation of the Compact (due to mandate limitations) and only submitted to the UN Secretariat a compilation of its own publications speaking to various objectives of the draft compact.