Forms are plastic, names cannot determine the essence of living things, and ceaselessly changing organisms cannot be conceived as elements within a signifying system. Each of these precepts of evolutionary theory finds itself reflected in Lewis Carroll's Alice books: Alice grows bigger and smaller without relation to any notion of a normal or standard size, fantastic organisms such as the “bread-and-butterfly” are generated out of metaphors and puns on taxonomic names, and the Queen's croquet game cannot function properly because the animals do not fulfill their prescribed roles. Lewis Carroll familiarized himself thoroughly with Darwinian theory in the years leading up to his composition of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1871). He “read widely on the subject of evolution” (Woolf 191), possessing “nineteen books on Darwin, his theories and his critics” (Smith 8), as well as five works of social evolutionist Herbert Spencer, including First Principles (1862), which put Darwinian theory in dialogue with religious understandings of the world (Cohen 350; Stern 17). As a lecturer in mathematics at Christchurch Oxford from 1855 to 1881, he was present during the famous 1860 debate at Oxford University Museum between Thomas Henry Huxley, one of the main proponents of evolutionary theory in the late nineteenth century, and Bishop of Oxford William Wilberforce, one of its major critics.Footnote 1

Carroll's response to the “Darwinian trauma”Footnote 2 was a fraught one: he was a devout Christian (he took deacon's orders in 1861, though he eventually refused the priesthood) who was also scornful of humanity's self-importance and deeply suspicious of the belief in a world made in the image of man and according to the dictates of human reason, attitudes which his anti-vivisection writings in the 1870s would make more explicit.Footnote 3 While Carroll may have publicly dissociated himself from the camp of Darwinists and supposedly atheistic men of science, the Alice books and their critique of anthropocentric logic can be read as a mode of engagement with Darwinian theory generally, and The Origin of Species in particular.Footnote 4 In broad terms, both Alice and The Origin of Species reorder the world outside of the standard representational confines of human subjectivity and the anthropocentric model of time as ordered, comprehensible, and linear progression. In The Origin of Species, the living world is produced in aleatoriness, the result of gradual, unintentional, and untraceable modifications to organisms over “tens of thousands” of generations, and shot through with the monstrosity that cannot be encapsulated by conceptual designations. In the Alice books, events are detached from a sense of progressive necessity and time becomes endlessly reversible. Here the conflict between the ordered and monstrous takes place upon the terrain of language, where bodies (whether human, animal, vegetal, or inanimate) and words become immanent with one another. Metaphors, puns, and portmanteau words destabilize the distinctions between word and reality, immaterial and material, sound and sense. The anthropocentric logic of representation, as what upholds the form of the (human) subject and the ordering of events into narrative, becomes ungrounded.

Appropriately enough, the manuscript that later developed into Alice's Adventures in Wonderland was titled Alice's Adventures Under Ground (completed by Carroll in 1863), and this motif of exploring the repressed underside of the dominant order of sense and meaning would inhere in the published Alice books. The “Under Ground” is also the place from which to subvert the linearity of time. In Gilles Deleuze's analysis in The Logic of Sense, the Alice books detach the “event” from any specific spatio-temporal order: events do not just occur in the present out of the past, but alter the past out of which they emerge as much as the present in which they take place. When Alice “grows” or “shrinks,” it is what Deleuze calls a “pure event” that belongs neither to the past nor the present order of things. There is no stable “Alice-before-growing” and “Alice-after-growing,” since Alice, after the plunge down the rabbit-hole, never exists within a specific set of spatio-temporal coordinates (3). The fall into the Under Ground, according to Deleuze, also marks the “loss of her proper name” and an end to the “permanence of savoir,” by which the “personal self” is granted an identity rooted in “God and the world in general” (5). This stripping of identity, of time, place, and world from the subject, speaks to the revolutionized contours of the post-Darwinian world, the end of formal consistency, teleological progress, and the transcendent, divinely ordained separation between things. The Alice books, as Donald Rackin points out, take place at a time when “natural moral progress, the sense of unitary, purposeful, God-given order and natural motion” are becoming outmoded ways of thinking about the world (93). Novelistic form, narrative progression, and plot, therefore, are the first casualties of Carroll's world. As Carroll writes in “Alice on the Stage”: “ ‘Alice’ and the ‘Looking-Glass’ are made up almost wholly of bits and scraps, single ideas which came of themselves” (294). It is as if the bare elements of plot (Alice's becoming older at the end of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Alice's becoming Queen at the end of Through the Looking-Glass) exist only to provide some kind of minimal framework for the profusion of events and becomings that comprise the bulk of the works.

The immanence of human and animal life introduced into popular contemporary discourse by Darwin allowed Carroll to rethink the place of the human in the world, particularly in opposition to the fictions of development and logical edifice upon which it is constructed and by which it is separated from the rest of the living world. The Origin of Species, with its critique of the conceptual reality by which the living world is understood, and its exploration of the irrepressible play of the organic world that anthropocentric logic fails to capture, offers Carroll a ground (or “Under Ground”) from which to unground the dominance of “sense” as the primary structuring category of experience. This ungrounding begins, in my analysis, with Darwin's and Carroll's reconceptualization of metaphor from its traditional application as an instrument of knowledge-production to a mode of engagement with the living world's unknowability, and proceeds to Carroll's mobilization of Darwinian theory through the expression of “nonsense” in the Alice books.Footnote 5

I. Metaphor and Monstrosity

A passage fromThe Origin of Species reads,

In North America the black bear was seen by Hearne swimming for hours with widely open mouth, thus catching, like a whale, insects in the water. Even in so extreme a case as this, if the supply of insects were constant, and if better adapted competitors did not already exist in the country, I can see no difficulty in a race of bears being rendered, by natural selection, more and more aquatic in their structure and habits, with larger and larger mouths, till a creature was produced as monstrous as a whale.Footnote 6 (210)

In the first sentence, Darwin makes a comparison between bear and whale based on physical resemblance and shared actions and capacities: some bears are “like” whales insofar as they are large mammals that swim through the water and ingest prey simply by catching it in their open mouths. His comparison foregrounds the fundamental difference between these species, which can resemble or be “like” each other, but cannot become one another, or cannot break the boundary of species that separates them. The two can share certain actions and capacities, but cannot share the same essence.

But the second sentence overturns this more conventional use of metaphor completely. Here Darwin surmises that the bear, by the action of natural selection, might become “rendered” into a creature “as monstrous as a whale” over centuries of time (time during which the bears that were most whale-like in their habits of consumption became the most successful in passing on their traits to future generations). This metaphor is what we might call an immanent metaphor: it employs two terms, bear and whale, but does not leave intact the formal consistency of either. It is not that the species of bear in question will simply evolve into a whale, one entity transmuting into another, but that it will develop into a “monstrous” creature that carries traits of both bear and whale but is reducible to neither. Entities are deprived of essences, of any kind of formal or bodily consistency that is preserved across time, and species come to be defined not by physical traits and characteristics, but by actions and capacities in relation to an environment and to other species (the black bear could only become such a “monstrous” creature in future generations if it had rivers in which to swim and a steady supply of insects to consume). This is opposed to what we might call “conceptual metaphor,” or metaphor that compares two entities by extracting a trait from one and applying it to the other while maintaining the formal separation between them (“he is a sloth”).

Metaphor, in Darwin's second usage, is not necessarily composed of two distinct terms bearing a passing resemblance or set of resemblances to one another, but of two formless, mobile, and malleable terms in ceaseless interaction with one another, and capable of producing a third, “monstrous” term that cannot be subordinated to either. To make a metaphor is to call into question the formal divisions between things, with the full knowledge that, within the space of comparison, one entity may well, somewhere in the vast span of geological time, take on the physical traits of another, become more like the other than itself, or give rise to a monstrosity that is neither self nor other. Immanent metaphor, then, takes place in a realm governed by non-transcendence, in which the forms of things are ceaselessly fluctuating because their consistency is not guaranteed by some external (transcendent) agency. Both terms act upon, affect, and reshape one another within the immanent field in which they are situated, thus undermining the grounds for species difference and creating new modes of interconnection between living things.

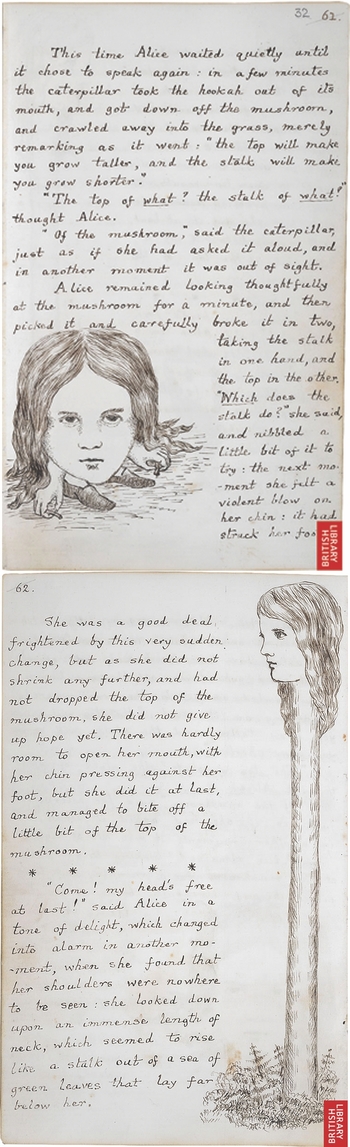

In the Alice books, Alice's bodily fluctuations bear directly on the question of species and the expression of species through metaphor, as we see when three-inch-high Alice, who finds herself without response to the Caterpillar's question, “Who are you?,” starts to shrink and grow alternately as she nibbles on the “right-hand” and “left-hand” sides of a mushroom (Carroll, AAIW 46). Lewis Carroll's own illustrations for this scene suggest the traumatic dimension of this fluctuation more explicitly than the published Tenniel illustrations (Figure 11).Footnote 7 In the first, Alice's body simply ceases to exist: the shrunken Alice is depicted as a disproportionately large head attached to a pair of shoes, with arms emerging from the bottoms of her cheeks. In the illustration of Alice's growth, we see her head growing directly out of her long stem-shaped neck, which in turn emerges from a patch of shrubbery. Her only “body” in this illustration is the earth itself. In both illustrations, the body is completely alienated from the head, invisible and uncontrollable, and made incorporate with the bodies around it (the earth, the trees, etc.). The language of representation here shifts into the register of immanence: as in Darwin, metaphors become a mode of breaking down the barriers of species and other forms of transcendent separation between things. In performing this function, metaphors also introduce monstrosity into the supposedly stable order of being: “[A]ll she could see, when she looked down, was an immense length of neck, which seemed to rise like a stalk out of a sea of green leaves that lay far below her” (47). In the space of this metaphorical comparison between neck and stalk, the neck becomes impersonal (“an immense length of neck”) and morphed into something not quite vegetal and not quite human: a monstrous “length” that arises neither from the human body, nor from the ground itself (as a “stalk” would), but from a groundless “sea” of “leaves.” The terms “neck” and “stalk” reshape one another within the space of the metaphor to form something removed from existing orders of bodies. In this sense, Carroll's characterization of his illustrations as “designs that rebelled against every law of Anatomy or Art” can be taken literally: they oppose bodily form as well as the laws of perspective and proportion (Carroll, “AOTS” 294).

Figure 11. Lewis Carroll, illustrations for Chapter III of Alice's Adventures Under Ground (1864). Images courtesy of the British Library. © British Library Board (46700, f. 60, 62).

A second immanent metaphor here further sets Alice's bodily composition into confusion. Carroll writes, “As there seemed to be no chance of getting her hands up to her head, she tried to get her head down to them, and was delighted to find that her neck would bend about easily in any direction, like a serpent” (AAIW 47). The serpent simile, however, takes on a new dimension when a nearby pigeon mistakes Alice for an actual serpent. Alice tries to assure her that this is not the case, but her stammers do not satisfy the Pigeon, who asks, “Well! What are you? I can see you’re trying to invent something?” Alice responds, “I – I’m a little girl,” but “rather doubtfully, as she remembered the number of changes she had gone through, that day” (48). Her “invention” collapses, however, when it comes to light that she has eaten eggs in the past, an act which she justifies by the fact that “little girls eat eggs quite as much as serpents do,” to which the Pigeon replies, “I don't believe it, but if they do, why, then they’re a kind of serpent: that's all I can say. . . . You’re looking for eggs. I know that well enough; and what does it matter to me whether you’re a little girl or a serpent” (48). The question of species becomes redefined according to actions and capacities and not by any idea of formal consistency. In this case, “species” is merely an unsatisfactory “invention” that fails to account for the appearance of life from a nonhuman vantage point, such as the Pigeon’s, in which the constitutive distinctions are based on the capacities and not the composition of the organism in question.

This introduction of difference into our understanding of life is exactly what is at stake in Darwin's use of metaphor in The Origin of Species. This is not difference that can be measured or standardized, and not difference that can be encapsulated by concepts such as “species,” “sub-species,” “varieties,” and “monstrosities”: these are hazy distinctions that imply a homogenously similar degree of difference among organisms, when in reality they merely cover over and supplant the vastly varying degrees of difference between organisms. Within larger genera, in Darwin's analysis, we define as separate “species” those organisms that would have been defined as “varieties” (implying a smaller degree of difference) if they had existed within a smaller genus. “[T]he amount of difference considered necessary to give to two forms the rank of species is quite indefinite,” Darwin writes, and goes on to tell us,

Certainly no clear line of demarcation has as yet been drawn between species and sub-species – that is, the forms which in the opinion of some naturalists come very near to, but do not quite arrive at the rank of species; or, again, between sub-species and well-marked varieties, or between lesser varieties and individual differences. These differences blend into each other in an insensible series; and series impresses the mind with the idea of an actual passage. (OS 131, 126)

In the same vein, Darwin writes at the end of Chapter Two of The Origin of Species,

Varieties have the same general characters as species, for they cannot be distinguished from species, – except, firstly by the discovery of intermediate linking forms, and the occurrence of such links cannot affect the actual characters of the forms which they connect; and except, secondly, by a certain amount of difference, for two forms, if differing very little, are generally ranked as varieties, notwithstanding that intermediate linking forms have not been discovered; but the amount of difference considered necessary to give to two forms the rank of species is quite indefinite. (131)

To say that something is of a certain species does not provide that organism with a proper “identity,” only a working differentiation from other organisms that may share traits with it, a differentiation that is always subject to collapse as the criteria for marking groups of animals as “varieties” or as “species” change.

The construction of species and varieties as categories also results from an inescapable anthropocentric bias on the part of scientists and observers, as Darwin notes:

I have been struck with the fact, that if any animal or plant in a state of nature be highly useful to man, or from any cause closely attract his attention, varieties of it will almost universally be found recorded. These varieties, moreover, will be often ranked by some authors as species. (125–26)

So, if the difference that produces metaphor consists of an “insensible series” that allows for the “actual passage” between conceptual distinctions, then it is our task to reveal what this difference is “in-itself,” in Gilles Deleuze's terms. Deleuze's analysis in Difference and Repetition (1968) is based on the idea that one of the dominant tendencies in Western philosophy is to erase the real differences between things (or “difference-in-itself”) by sublimating them into conceptual differences, and Darwin's Origin of Species seems to participate in the same general project of affirming difference and variation as forces that inhere within all things and that cannot be adequately encompassed by the conceptual register.

Darwin theorizes these two types of metaphor (what I am calling conceptual and immanent), somewhat messily, in a lengthy passage in Chapter XIII of the Origin, “Classification”:

Naturalists frequently speak of the skull as formed of metamorphosed vertebrae: the jaws of crabs as metamorphosed legs; the stamens and pistils of flowers as metamorphosed leaves; but it would in these cases probably be more correct, as Professor Huxley has remarked, to speak of both skull and vertebrae, both jaws and legs, &c., – as having been metamorphosed, not one from the other, but from some common element. Naturalists, however, use such language in a metaphorical sense: they are far from meaning that during a long course of descent, primordial organs of any kind – vertebrae in one case and legs in the other – have actually been modified into skulls or jaws. Yet so strong is the appearance of a modification of this nature having occurred, that naturalists can hardly avoid employing language having this plain signification. On my view, these terms may be used literally; and the wonderful fact of the jaws, for instance, of a crab retaining numerous characters, which they would probably have retained through inheritance, if they had really been metamorphosed during a long course of descent from true legs, or from some simple appendage, is explained. (366–67)

What literary scholar Jeff Wallace, in his discussion of this passage, calls an “inconsistency” in Darwin's use of the word “metamorphosis” as both a “metaphor” and a “plain signification,” I consider a grasping for a more nuanced understanding of metaphorical expression and of difference itself (Wallace 26). In this context, the “metaphorical sense” of the Naturalists refers to their use of the word “metamorphosis” as a metaphor to mean an abstract comparison of one thing to another based on resemblance: the jaws of a crab look as if they have metamorphosed from legs, for example. They employ this metaphor without realizing that they are not just making an abstract comparison, but literally describing the growth and development of existing life-forms from common, but unknown, origins (“from some common element,” or from “primordial organs of any kind”). Vertebrae and skull, legs and jaws, stamens and leaves, then, do not necessarily pre-date one another and do not actualize some prior concept of themselves (as legs, jaws, vertebrae, skulls, etc.), but only come into being through their differentiation from a common element and thus from one another, a differentiation that can easily collapse back into the sameness of the common element over the span of geological time. This precarious differentiation is what we might call the “origin” of species.

In this sense, metaphor is a literal metamorphosis or transformation, but one without a singular direction (legs do not become jaws, nor jaws legs, but both emerge out of a common element) and in which the entities in relation do not have the formal guarantee of self-consistency to fall back upon (the leg is not a leg, the jaw not a jaw, prior to its differentiation from the common element, into which it might one day be absorbed again). The term “metaphor” originates from a combination of the Greek words μετά (meta) for “between” and φέρω (phero) for “to carry”: the “carrying” of one thing into another in metaphor, we might say, is only ever a “carrying between,” without fixed origins and endpoints.

The entire metaphorical apparatus of the Origin of Species is indexed by a single metaphor: this is the “great Tree of Life,” the diagram illustrating the action of natural selection on species in terms of the unpredictable and multidirectional growth of branches on a tree (Figure 12). The vast number of existing species are shown to have developed from a set of hypothetical ancient progenitors, numbered A through L, over the course of “thousands of generations,” each interval of a thousand generations marked by a Roman numeral from I-XIV. It is a metaphor for the irrepressible difference and multiplicity of life that, in itself, has no singular origin and no teleological finality: the Tree of Life persistently exceeds the parameters of the diagram in which it is placed; it signifies only its own signification-in-excess. In other words, it is a metaphor that is overwhelmed by the ceaseless interconnectivity and recombinatory play of what it metaphorizes. All species and life-forms are branches upon the Tree of Life, but the Tree of Life has no singular origin and its structure continually fluctuates based on the uncontrollable growth of its branches.

Figure 12. Charles Darwin, “The Tree of Life,” in The Origin of Species. Reproduced with permission from John van Wyhe, ed., The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online (http://darwin-online.org.uk).

The Tree of Life metaphorizes the inadequacy of conceptual comparisons between organisms by which to comprehend the living world, since metaphors based on a shared identity, physical resemblance, or analogical correspondence presuppose an originary and stable essence for each organism. As Darwin explains,

The affinities of all the beings of the same class have sometimes been represented by a great tree. I believe this simile largely speaks the truth. The green and budding twigs may represent existing species; and those produced during each former year may represent the long succession of extinct species. At each period of growth all the growing twigs have tried to branch out on all sides, and to overtop and kill the surrounding twigs and branches, in the same manner as species and groups of species have tried to overmaster other species in the great battle for life. (OS 176)

As buds give rise by growth to fresh buds, and these, if vigorous, branch out and overtop on all sides many a feebler branch, so by generation I believe it has been with the great Tree of Life, which fills with its dead and broken branches the crust of the earth, and covers the surface with its ever branching and beautiful ramifications. (177)

At no point does Darwin answer, or attempt to answer, the question of the origin of the tree or the precise nature of the ancient progenitors of the current living species. In The Descent of Man (1871), the unknown ancestors of the human race are always known as “ape-like progenitors,” not as a singular and definite form (Darwin does not simply say “ape” because he is uncertain whether humanity descended from a progenitor closer to the family of the gorilla or the chimpanzee): the common “origin” is both indistinct and plural, and there is no transcendent position from which to determine the proper identity of the human race, or of any other existing organism (DOM 154). In later instances, Darwin speaks of “the advancement of man from a semi-human condition” and tells us that “man is the co-descendant with other mammals of some unknown and lower form” (158; 173). We know nothing, Darwin implies, of the origin of the Tree of Life, and even less of its finished or completed form, but are only privy to its “surface” effects: the “beautiful ramifications” on the surface of the earth that have not yet been covered over by the weight of history and sedimented into the depths. It is a knowledge-disabling rather than a knowledge-producing metaphor, since it only describes the bare aspects of multiplicity, difference, and variation prior to their fixing into (and erasure under) conceptual distinctions: in the last sentence, the noun “branches” becomes transmuted into the verb “branching,” the image that ends the “Natural Selection” chapter, and suggests the continual production of an infinite degree of variation and difference (“ever branching”).

The Tree of Life, then, is a metaphor that consists of the upheaval of conceptual metaphor, and conceptual language, itself. Language cannot contain the signification-in-excess of the ever ramifying Tree of Life, and the concepts of species, genus, and varieties that are meant to adjudicate and standardize the difference between organisms from a metaphysical position are always subject to fluctuation by the organisms themselves and the myriad forms they take over the course of “thousands” or “tens of thousands” of generations under natural selection. Organisms signify from a location somewhere outside the endpoint of the concept (the species) and the origin of the first progenitors, an origin that is not only shrouded but irrevocably lost in the layers of evolutionary and linguistic history. Metaphor, for Darwin, is a mode of reintroducing the force of difference that language, in its nominalist function, covers over or sublimates into conceptual difference. Metaphor injects the monstrous back into metaphysical language; it introduces the trauma of immanence that ungrounds every conceptual designation of what species are and relates language back to the material world with which and through which it has evolved.

But this association of metaphysical language with the material world is not the same as “grounding” it in the material world, because language has no traceable or “definite” origin in this world. Metaphor is a process of persistent ungrounding, but its end result is not to reground metaphysical language in the material particulars from which it emerged (since the “definite origin” of these material particulars, like the heuristic fiction of the primordial progenitor(s), is impossible to trace), but to hold open the space outside of pure materiality and pure conceptuality where all bodies and words co-exist, cohere, and interact. This is the space of immanent metaphor, in which organic forms are made infinitely malleable or “plastic” and in which comparisons between two entities can amalgamate them into a “monstrous” third beyond the formal nature of either: a bear that swims becomes “as monstrous as a whale” over the course of thousands of generations simply by its continued actualization of certain capacities.

If Darwin's Tree of Life is the metaphor of metaphor (albeit a metaphor that itself is overwhelmed by the ceaseless interconnectivity and recombinatory play of what it metaphorizes; or a metaphor that only metaphorizes its own sweeping away), it is also a metaphor without ground, based on the fiction or absent origin of a set of progenitors that remain unknown and unknowable to us. As such, it is the immanent metaphor par excellence; it is immanent metaphor itself: the groundless ground upon which immanent metaphors, as modes of connection between two or more living things that do not take into account or leave intact the formal consistency of any of them, come into being. Form itself is a fiction predicated upon an absent origin, a mode of measuring difference that fluctuates based on the action of organisms in time and their persistent introduction of difference that exceeds the demarcations of the formal categories of genus, species, sub-species, and variety.Footnote 8 The Origin's revolutionary upheavals of conceptual language, the logic of representation, and the anthropocentric model of cognition and knowledge-production are precisely, I want to argue, the substance of Carroll's engagement with evolutionary theory in the Alice books.

II. “A very difficult game indeed”: Evolution in Wonderland

“Get to your places!” shouted the Queen in a voice of thunder, and people began running about in all directions, tumbling up against each other: however, they got settled down in a minute or two, and the game began.

Alice thought she had never seen such a curious croquet-ground in her life: it was all ridges and furrows: the croquet balls were live hedgehogs and the mallets live flamingoes, and the soldiers had to double themselves up and stand on their hands and feet to make the arches. (AAIW 73)

In “The Queen's Croquet-Ground” chapter of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, we have all the elements of evolutionary theory in microcosm: an arbitrarily ridged and furrowed terrain upon which varying species coexist; the formation of organisms as species (balls, mallets) according to certain contingent characteristics; the propulsion of life into motion (via an incomprehensible injunction to order) issued by the voice of an inaccessible, unreasonable, and mindless force (the Queen of Hearts, or Natural Selection); the chaotic interactivity and multi-directional movement among organisms that do not and know not how to adhere to a fixed position or code of behavior; and the persistent threat of extinction by the Queen of Hearts’ arbitrary (and frequent) command, “Off with their heads!” (72). Carroll suggests as much in his description of the Queen in “Alice on the Stage”: “I pictured to myself the Queen of Hearts as a sort of embodiment of ungovernable passion – a blind and aimless Fury” (296). If the Croquet-Ground is the microcosm of a world, it is a world made not in the image of human reason and not driven by intention or “design,” those dogma Darwin spent his life's work undermining. As with The Origin of Species, the chaos of the Croquet-Ground results from the animals’ incongruity with the concept, or with the linguistic systems of order and classification imposed on them:

The chief difficulty Alice found at first was in managing her flamingo: she succeeded in getting its body tucked away, comfortably enough, under her arm, with its legs hanging down, but generally, just as she had got its neck nicely straightened out, and was going to give the hedgehog a blow with its head, it would twist itself round and look up in her face, with such a puzzled expression that she could not help bursting out laughing; and, when she had got its head down, and was going to begin again, it was very provoking to find that the hedgehog had unrolled itself, and was in the act of crawling away: besides all this, there was generally a ridge or a furrow in the way wherever she wanted to send the hedgehog to, and, as the doubled-up soldiers were always getting up and walking off to other parts of the ground, Alice soon came to the conclusion that it was a very difficult game indeed. (73–74)

While the flamingo is conceived as a mallet, the hedgehog a croquet-ball, the human as an arch, the organisms resist these conceptual designations by simple motion, by asserting the minimal degree of difference that makes them non-functional within the signifying system or the taxonomic order in which they are placed: moving from straightened to twisted neck, rolled to unrolled body, arched to straight back. A hedgehog becomes something other than its designation (as a ball) when it interacts with its environment and with the organisms around it. This is the motion that cannot be incorporated into the game, and that makes order impossible by denaturing the laws of the game from within. Nothing remains what it is: static nouns become transfixed by the twisting, rolling, and arching of verbs. “[Y]ou’ve no idea how confusing it is all the things being alive,” complains Alice (75). This takes place over seconds of the croquet game, seconds which, I am arguing, stand in for thousands of generations of the evolutionary time-scale.

Carroll's illustration of this scene, which does not appear in the published Alice books, gestures towards the idea of the Croquet-Ground as a crowded, microcosmic world-in-flux (Figure 13). It is centered on the menacing Queen of Hearts, who holds up a (real) croquet mallet with which she threatens a plaintive-looking hedgehog on the left edge of the illustration, the only one among several not rolled into a ball. In the midst of a terrain overpopulated with hedgehogs, the Queen marks the destructive and “blind” force that acts indiscriminately as a check on the hyper-productivity of organisms. As Darwin writes concerning nature's necessary destructive side in the “Struggle for Existence” chapter of The Origin of Species:

Figure 13. Lewis Carroll, illustration for Chapter IV of Alice's Adventures Under Ground (1864). Image courtesy of the British Library. © British Library Board (46700, f. 75).

Lighten any check, mitigate the destruction ever so little, and the number of the species will almost instantaneously increase to any amount. The face of Nature may be compared to a yielding surface, with ten thousand sharp wedges packed close together and driven inwards by incessant blows, sometimes one wedge being struck, and then another with greater force. (64)

The specter of violence in the croquet scene reflects nature's potentially violent modes of regulating, by destroying, populations of species: the hedgehog runs the literal risk of being “driven inwards by incessant blows,” if we take the mallet-wielding Queen as an embodiment of Darwin's metaphor of nature's destructivity.

Between the Queen and the hedgehog we see a wildly flapping, shrieking flamingo that a courtesan attempts to hold in place by grasping the animal's legs. This flamingo, on the left side of the illustration, is mirrored by another one of its species flailing in the top right corner as a matronly figure clutches it to her breast. Constraint into concept is impossible in this image, since the direction of movement and modes of interaction between beings and among orders of being are unpredictable. The game has no logical outcome that would accord with its own internal laws, but is continually remade by the aleatory actions of its players. Alice stands mute, passive, and helpless, unable to intervene into the chaos and powerless to prevent it. This crowded, chaotic vision of disorderly bodies in motion expresses both the immanence of humans and animals, as organisms subject to evolutionary pressures and deprived of bodily agency, and the incongruity of the world with the calculable, logical processes and systems of order (whether linguistic, biological, mathematical, or other) by which we have conceived it.

III. Body-Words and the Failure of Order

This inability to impose order on the chaotic movement of life is mapped onto Carroll's use of nonsensical language in the Alice books. The pun and the portmanteau word, particularly, introduce monstrosity into the order of conceptual language and dismantle the anthropocentric order of meaning that divides speaking and reasoning humans from mute, instinctual animals. Puns portend the collapse of conceptual distinctions by which reality is upheld and the remaking of transcendent language as agglutinative material. Portmanteau words concatenate multiple words but strip them of any referential sense or grounding in metaphysical meaning, so that words encounter other words in the absence of a stable, self-evident identity to fall back upon.

In Chapter IX, “The Mock Turtle's Story,” we encounter two imaginary creatures, the Mock Turtle and the Gryphon, who speak entirely in puns and whose very existence throws into question both the ordered composition of bodies and the ordered constitution of words. In Greek mythology, the Gryphon is an amalgamation of an eagle and lion, and in the peculiar etymology lesson given by the Queen, the Mock Turtle is “the thing Mock Turtle Soup is made from” (AAIW 81), Mock Turtle Soup being “Calf's head dressed with sauces and condiments so as to resemble turtle” (OED). Carroll's Mock Turtle, then, emerges directly out of language and into the physical world; he is the embodiment of a pun who can only reflect his fractured origins through the act of punning, or employing a mode of language that collapses the distinction between intended meaning and derived counter-meaning. The most immediate pun is the word “mock,” which suggests that the Mock Turtle is both a confused culinary product come to life and the imitation, or “mockery,” of a real turtle. In the process of making this pun, Carroll confounds the distinction between original and copy, between real and linguistically produced turtle: as the sobbing Mock Turtle claims, “Once, I was a real Turtle” (AAIW 83).Footnote 9 His schoolmaster was “an Old Turtle” whom they used to call “Tortoise,” because, as he explains to Alice, “he taught us” (83). Teacher and tortoise, and soon reading/“reeling,” writing/“writhing,” Latin/“Laughing” and Greek/“Grief,” and lessons/“lessens” among others, collapse into one another and disrupt the networks of meaning upon which language is based.

As Derek Attridge writes in his analysis of puns in Finnegans Wake,

As speakers, we construct our sentences in such a way as to eradicate any possible ambiguities, and as hearers, we assume single meanings in the sentences we interpret. The pun, however, is not just an ambiguity that has crept into an utterance unawares, to embarrass or amuse before being dismissed; it is ambiguity unashamed of itself, and this is what makes it a scandal and not just an inconvenience. In place of a context designed to suppress latent ambiguity, the pun is the product of a context deliberately constructed to enforce an ambiguity, to render impossible the choice between meanings, to leave the reader or hearer endlessly oscillating in semantic space. (141)

I would qualify Attridge's conception of the pun's ambiguity by noting that the pun always runs the risk not only of being “dismissed” after the intended semantic meaning is comprehended, but of enshrining the “real” semantic meaning even more forcefully, now that the divergent possibility posed by the pun has been met, overcome, and expiated from the intended meaning. The binary structures of original/artificial, intended/accidental, etc., then become all the more firmly upheld. To make the ambiguity of the pun inhere, however, Carroll employs puns as pieces of embodied language that disrupt the abstract transmission of knowledge: each mode of knowing is countered by a form of bodily motion (reading/“reeling,” writing/“writhing”) or bodily affection (Latin/“Laughing,” Greek/“Grief”) that the Mock Turtle has apparently been taught. As the punning language of the Mock Turtle collapses the abstract sense and material sound of words into one another, language itself (as a mode of abstract knowledge transmission) becomes conflated with the material counterpart of what it purports to represent, or “be master” over, in Humpty Dumpty's words. The distinction between concepts and the embodied, concrete particulars that concepts try to contain comes to be undermined, or “lessened,” as Carroll's puns implode the binary logic that structures this separation. The pun undermines both terms as self-consistent units of knowledge and estranges semantic space from itself. “Meaning,” then, encompasses more than just “semantic meaning” or “sense,” but neither is it reducible to its material referent. As Jonathan Culler proposes in his analysis of punning in “The Call of the Phoneme,” “Puns present us with a model of language as phonemes or letters combining in various ways to evoke prior meaning and to produce effects of meaning with a looseness, unpredictability, [and] excessiveness . . . that cannot but disrupt the model of language as nomenclature” (22). The end result of Carroll's puns in this chapter is to place readers not only outside semantic space, but a space outside of both carnal and linguistic reality, or what carnal and linguistic modes of knowing can contain.

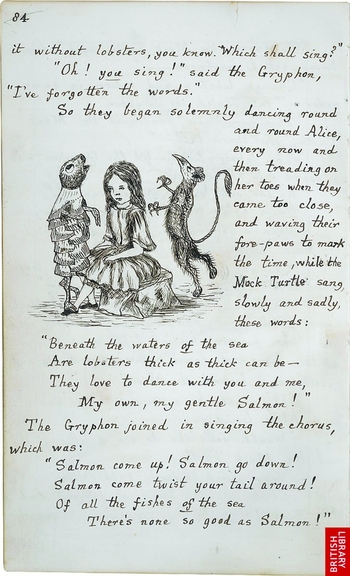

The binary logic that Carroll implodes with this series of puns is not just the logic of sense and sound, abstraction and materiality, but the logic of separation between human and nonhuman life. Carroll couples this ambiguity of linguistic identity with a fundamental ambiguity at the core of bodily composition, which we see in his illustrations. In the Tenniel illustrations, the Mock Turtle and Gryphon are amalgamations of multiple forms, but these forms maintain the conceptual distinctions of “calf,” “turtle,” “eagle,” and “lion” (Figure 14). Carroll's illustrations (Figure 15) give us creatures without concept, monstrous floating forms open-throated in agony, figuratively deprived of formal consistency and literally detached from the ground itself. The flying Mock Turtle throws wide its pitchfork-shaped arms and legs in every direction, the series of stony flaps that make up the shell bending backwards with the “writhing” of its body. The creatures appear to be melded into one another: the Mock Turtle's head seems to grow organically from the side of the Gryphon's body while the Gryphon's tail snakes into the shell of the Mock Turtle at the point where the Mock Turtle's body bends in half, emerging out of an opening on the other side. These are illusions of depth, of course, but all sense of proportion is thrown out of order when we look to the dwarfed Alice, who measures not even a tenth of creatures’ size in this image but has to sit to make herself eye-level with them in the next (Figure 16). Here the creatures threaten to squash the tiny Alice as soon as they make their way back down to earth.

Figure 14. John Tenniel, illustration for Chapter X (“The Lobster Quadrille”) of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (London, Penguin: 1998 [orig. 1865]), 88.

Figure 15. Lewis Carroll, illustration for Chapter IV of Alice's Adventures Under Ground (1864). Image courtesy of the British Library. © British Library Board (46700, f. 82).

Figure 16. Lewis Carroll, illustration for Chapter IV of Alice's Adventures Under Ground (1864). Image courtesy of the British Library. © British Library Board (46700, f. 84).

For Carroll, the “animal” generally is not a legible, manageable, and receptive entity inscribed into human discourse, but a monster that corresponds to no existing “species” and responds to no name; in other words, Carroll's animals refuse both bodily form and linguistic order, and by so doing reveal the contingency of anthropocentric logic. The language Alice believed to be a neutral medium of designation becomes shot through with carnality, with bodily action (“reeling and writhing”) and disfigured bodies that refuse to operate within the limits of sense or of species. The only resolution to the Mock Turtle's dilemma, as both a creature of linguistic fabrication as well as a “real Turtle,” poised between the orders of the semantic and the material, is to dissolve (metaphorically) into the primordial “soup” from which it emerged, a soup that is both “Mock Turtle Soup” (in Alice's Adventures Under Ground) and real “Turtle Soup” (in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland). The Mock Turtle sings a song with the “melancholy” refrain of “Beau – ootiful Soo – oop!/ Beau – ootiful Soo – oop!/ Soo – oop of the e – e – evening,/ Beautiful, beauti – FUL Soup!”, in the process both doubling semantic meaning over upon itself (by breaking the words at the middle) and converting semantic meaning into bare sound (the detached syllables “eau,” “oo,” “ee,” etc.) (AAIW 93). The song urges the consumption of Mock Turtle/Turtle Soup (“Who would not give all else for two p/ ennyworth only of beautiful Soup?”), and by extension marks the self-dissolution of the Mock Turtle into the confused linguistic and material origins out of which all life, human and nonhuman alike, emerges (94).

If the pun produces an ambiguity between the linguistic and the physical, abstract name and bodily referent, semantic order and the order of species, the portmanteau word produces an ambiguity in the interactions of words with one another. The portmanteau word does not amalgamate words and bodies (such as the girl-serpent mutation we explored earlier), but concatenates multiple words into a single word. This has the effect of estranging words from their own origins, or de-ontologizing the process by which meaning is attached to words. The portmanteau word, then, strips words of semantic meaning and denatures the relationship between word/thing and meaning/sense by multiplying the valences through which this relationship occurs. We can couple the portmanteau's concatenation of multiple words unmoored from semantic security with the analysis of immanent metaphor as that which strips organisms of stable and essential form or identity as it puts them into interaction with one another. Words, in this way, are biologized, and made akin to Darwin's idea of species as fluctuating categories without the transcendental guarantee of preservation over time. In a portmanteau word such as “slithy,” for example, there is no way to isolate any of the words “slither,” “lithe,” “slide,” “slimy,” and “sly,” and the various senses that adhere to each word along with the ways that these words relate to one other, out of the larger space of the portmanteau word. In immanent metaphor, as we saw, the formal definitions of organisms, such as “bear” and “whale,” were thrown into confusion at the possibility of a creature formed over the course of centuries of natural selection that would exist as a monstrous amalgamation of many existing organisms (a creature both bear-like and “monstrous as a whale”). Evolutionary theory produces monstrous amalgamations of organisms by undermining (or “ramifying,” in Darwin's words) the one-to-one correspondence between organism and form, just as the portmanteau word produces nonsensical concatenations of words by stripping words of their grounding in stable meanings.

This, I want to argue, is what is at stake for Carroll in the portmanteau word: a redefinition of life away from the stability of plan, progress, and development, and towards the aleatory, disjunctive, and non-teleological. We can read Carroll's Jabberwock as a “portmanteau organism”: as the messy coagulation of non-conceptual, nonsensical, inhuman language and bodily form in the body of a single monstrous creature (Figure 17). According to Carroll, the term “Jabberwock” condenses both “jabber,” as “excited and voluble discussion” and “woce,” or “to bear fruit,” to make what Carroll refers to as “the result of much excited and voluble discussion” (qtd. in Cohen 443).Footnote 10 To “jabber” is also “to talk rapidly and indistinctly or unintelligibly; to speak volubly and with little sense; to chatter, gabble, prattle,” “to utter inarticulate sounds rapidly and volubly; to chatter, as monkeys, birds, etc.,” and “to speak (a foreign language), with the implication that it is unintelligible to the hearer” (OED). The origins of words are buried beneath endless layers of animal and human “chatter.” The Jabberwock then expresses the uncontrollable growth of nonsense words and the production of unintelligible sound and syllables that denature human networks of meaning from within. As such, it stands as the index of both linguistic and bodily possibility in the Alice books, much like that other “fruit-bearing” and “ever branching” figure we discussed earlier, Darwin's Tree of Life, which was the index of all metaphorical possibility in The Origin of Species and of which Carroll must have been at least minimally aware from his studies of Darwinism. The Jabberwock, finally, is also what must be slain in order for language to resume a designating function, without collapsing into the inarticulacy of the cry. “Woce” is also an archaic word for “voice,” with its etymology in the Latin word voce (“voice”), which would make the Jabberwock a creature in whom the “voice,” that supposedly objective, and exclusively human-owned, indicator of individual and biological identity, is continually threatened by the indiscriminate “jabber” that we humans attempt to disavow as “nonsense.”Footnote 11

Figure 17. John Tenniel, “The Jabberwocky.” Illustration for Chapter I (“Looking-Glass House”) of Through the Looking-Glass (London, Penguin: 1998 [orig. 1872]), 133.

We can read “Jabberwocky” and its constitutive unknowability and refusal of formal consistency (of the word, body, and meaning alike) as an expression of the post-Darwinian landscape, in which the present state of things has been produced from an illegible set of primogenitors and thus bears an uneasy relationship to its history and pre-history. Consider Alice's response to the poem: “Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideas – only I don't know exactly what they are! However, somebody killed something: that's clear, at any rate” (TTLG 134). The evolutionary terrain is vast and endlessly productive, but what it produces is unknowable in itself, in its particular spatio-temporal realization. Instead, its products are only comprehensible through the hollowed-out categories of “[s]omehow,” “somebody,” and “something,” which cover over the unknown particulars of the processes by which organisms have come to be what they are. Because bodies, species, and words in the present have been formed out of untraceable biological and philological dynamics in the past, the present is something alien to itself. If words, as I have been suggesting, have achieved a stable form and fixed set of meanings in the present, this is only ever the result of excluding millions of other possibilities that did not become actualized in its present form. This process runs parallel to the course of evolutionary change, in which countless mutations and adaptations within a single species occur ceaselessly throughout the lifespan of the species, but only a tiny fraction are taken up by Natural Selection and thus inhere in its present form. “Jabberwocky” speaks to our ignorance of the conditions by which words, bodies, and species have become themselves by differentiating themselves from other words, bodies, and species, and from the “beautiful soup” of the undifferentiated and non-conceptual from which they have emerged. Its portmanteau words create new modes of relation between words stripped of their supposedly ontological grounding in sense, in the process moving our understanding of language and life away from the model of progressive development and towards the forces of accident and aleatory play. We can think of the Jabberwock as the source of all portmanteau and nonsense expression in the Alice books: here is the “fruit-bearing” organism, the metaphor of hyper-production of words, bodies, and senses that multiply beyond the grasp of what can be counted, mapped, and ordered by anthropic sense, and the body-word by which all bodily and linguistic contortion in the Alice books is indexed.

But the Jabberwocky is beheaded, Alice leaves childhood, words settle into articulacy, and Wonderland thrives only in the recesses of what Carroll, in the opening poem of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, calls “Memory's mystic band” (6). All the temporal, spatial, and bodily unbinding we have experienced in the Alice books seems bound to the time of childhood, for Carroll, a temporality in which the ceaseless fluctuation of bodies, things, and words is not only a possible but a desirable state of affairs. To become individuated, which seems almost synonymous with growing old for Carroll, is to accept foreclosure from the world and its multifarious and transformative possibilities as a condition of being in it, as Alice does when she becomes a mother-figure at the end of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and becomes Queen in Through the Looking-Glass. As the latter she is empowered over her surroundings and capable not only of reducing them to order, but making her version of order correspond with a version of objective reality: “The Red Queen made no resistance whatever: only her face grew very small, and her eyes got large and green: and still, as Alice went on shaking her, she kept on growing shorter – and fatter – and softer – and rounder – and – [.] – and it really was a kitten after all” (TTLG 235–36). This fixation into form and resolution into stable order is what the events of the Alice books resist, but we still seem to close with a capitulation to the logic of bildung.

Or at least we would if the tale ended here. Instead, the final chapter, “Which Dreamed It?,” features Alice speaking to Dinah and her kittens and closes with a scene of Alice posing an irresolvable paradox to the Queen (newly transformed into a kitten):

“Now Kitty, let's consider who it was that dreamed it all. . . . You see, Kitty, it must have been either me or the Red King. He was part of my dream, of course – but then I was part of his dream, too! Was it the Red King, Kitty? You were his wife, my dear, so you ought to know – Oh, Kitty, do help to settle it! I’m sure your paw can wait.” But the provoking kitten only began on the other paw, and pretended it hadn't heard the question.

In the closing line, the object of address slips from the kitten to us, the audience, who are put in the same position of being confronted with a question to which we lack the capacity to respond. It is all we can do to oscillate between opposing, irremediable possibilities, the movement of our thought akin to the kitten's licking one paw and then another.

In a letter to physician and mathematician Daniel Biddle on Zeno's Paradox, Carroll writes, “[B]ut a thing is not impossible, merely because it is inconceivable. The human reason has very definite limits” (Letters I: 589). These limits are perhaps what Carroll plays upon in the closing lines of the Alice books, in which the entire anthropic order assumes the condition of the kitten in its ignorance of its own origin (brought into existence via transformation from one being to another) and its inability (or refusal) to respond to the question in the same idiom in which it was phrased: following this metaphor, human reason operates only by the excision of the unanswerable question, the paradoxical instance, or the nonsensical statement from its purview, under the pretense that “the question” never existed (or was never “heard”). Being “Queen,” or assuming the position of mastery, is circuitously equated with Alice's ignorance of her proper name and bodily composition at the opening of the Alice books, her queenly condition providing only ignorance of her own ontology (the dreamer or the dream?) and mirrored in the devolution of the Red Queen into a kitten.

In the intersecting images of Alice transformed into a Queen and another Queen transformed into a kitten, Carroll affirms an evolutionary vision that resonates with Darwin's troubling metaphorical concatenation of bears and whale-like creatures in The Origin of Species. If such transformations and mutations are inconceivable, that is only because the limits of human reason and the doctrine of anthropocentric sense cannot encompass the reversibility of time and the fungibility of subject-positions that govern the evolutionary world and the world of nonsense alike.