Introduction: The Culture Wars as Worldview Wars

Christian conservative thinkers and activists have taken great pains to articulate what they call a “Christian worldview” and to compare it to its intellectual and spiritual competitors, such as liberal secularism.Footnote 1 They have also carefully articulated the Christian worldview's theological, cultural, and social implications in a number of key public documents, such as the Hartford Appeal,Footnote 2 and the Manhattan Declaration.Footnote 3 This notion of a Christian worldview includes theological content, such as the existence of a personal, Trinitarian God, the accuracy of the biblical witness to the life and teachings of Jesus, and the salvific effect of his crucifixion and resurrection. But the idea of a Christian worldview goes much further, extrapolating from these theological tenets detailed principles at the heart of many social controversies: principles like the significance and dignity of human life from conception to natural death,Footnote 4 the meaning and proper exercise of human gender and sexuality,Footnote 5 and the proper function of government.Footnote 6

Through these principles, the Christian worldview motivates legal organizations and activists to advance and defend Christian conservative positions in various legal controversies, such as the ability of Christian business owners to serve same-sex couples looking to celebrate their weddings, the availability of bathrooms for transgender students, or new restrictions on the right to abortion. On these and other issues, Christian conservative legal thinkers, lawyers, and activists argue that they are motivated by a cohesive and comprehensive worldview.Footnote 7 Groups like the American Center for Law and Justice, the Alliance Defending Freedom, and Liberty Counsel specialize in what could be called Christian worldview litigation—that is, defending people “who have a Christian worldview [and] are facing significant harassment and discrimination.”Footnote 8 In short, Christian conservative legal organizations see their mission as making sure that American law is still safe for the Christian worldview.Footnote 9

In the wake of several high-profile legal defeats—most notably the US Supreme Court's decision to constitutionally protect same-sex marriages—there was a significant degree of pushback in Christian conservative circles to the idea of aggressively advancing their worldview in this long-running culture war.Footnote 10 But these calls for strategic withdrawal appear to have now been matched by an equally strong retrenchment of Christian worldview claims.Footnote 11 Especially after the election of Donald Trump and his successful nomination of three socially conservative Supreme Court Justices, Christian conservatives have pursued new avenues in the culture wars, such as engaging in civil disobedience against laws protecting same-sex marriageFootnote 12 and providing access to contraception or abortion,Footnote 13 discrediting and defunding Planned Parenthood,Footnote 14 and fighting against legal protections for the transgender community.Footnote 15

Given the evident importance of the Christian worldview as a motivator for Christian conservative legal efforts, scholars of the movement have paid precious little attention to the concept of worldview. This article fills that gap by tracing the historical, philosophical, and theological roots of worldview theory and assessing the way this theory is employed by Christian conservative legal activists.

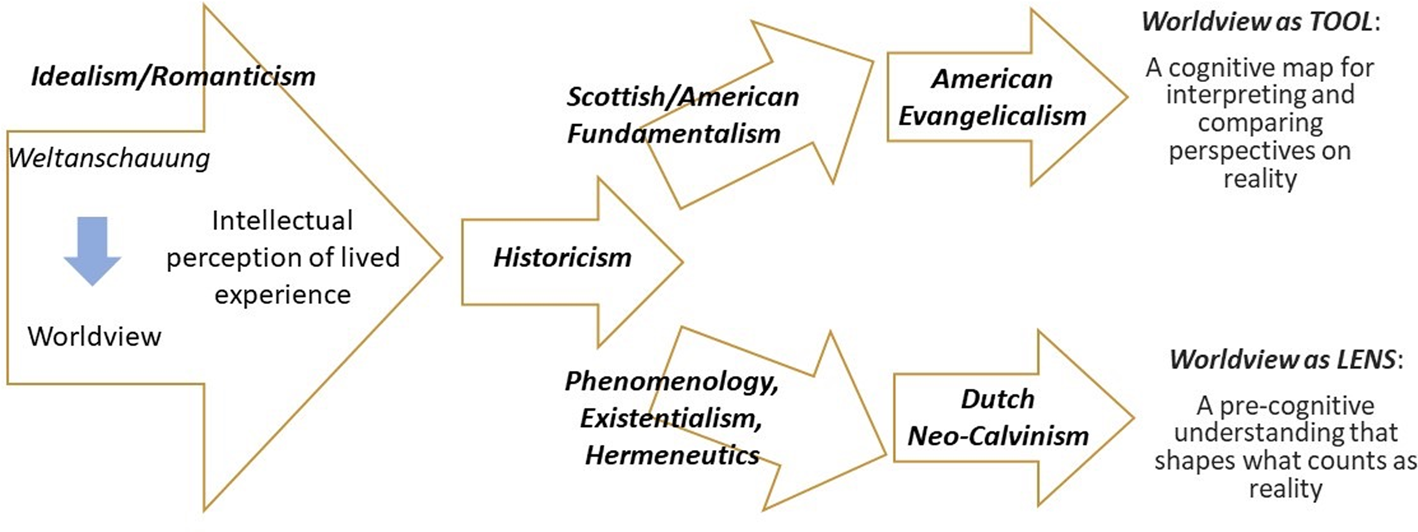

First, using primarily Christian scholarly sources, I trace the roots of the “worldview” concept from Immanuel Kant through Martin Heidegger and Ludwig Wittgenstein, showing how two strands of worldview theory wound up producing two different worldview traditions. One tradition, influenced by Scottish and American evangelicalism, used worldview as an analytic “tool” to rationally explain and defend Christian ideas. The other worldview tradition, influenced by Dutch Neo-Calvinism, saw worldview as a constitutive “lens” made up of pre-theoretical ideas and commitments.

Second, I describe how influential Christian conservative legal thinkers, lawyers, and activists rely on the first worldview tradition, as an analytic tool, to understand issues like sexuality and gender identity in an essentialist way and to demonstrate with foundationalist logic the rational superiority of their legal conclusions about these issues.

Third, I analyze the Christian conservative use of worldview as a tool in legal controversies, especially in the controversy over laws relating to sexual orientation and gender identity laws. Drawing on the tradition of worldview as a pre-theoretical lens, I argue that Christian conservatives fail to appreciate the context-dependent and socially constructed nature of human understanding and identity. Because we do not have access to a neutral perspective or standpoint outside of any worldview, I argue, substantive legal theories or arguments informed by different worldviews cannot be objectively compared, nor demonstrated superior, to one another. However, I argue, embracing the particular worldviews that construct our understanding of reality and our standards of appropriate evidence can be a productive enterprise. Using narrative and storytelling to describe the truth about sexuality, gender identity, and other issues we see through our particular worldview lenses can help Christian conservative groups, as well as those they oppose, to better engage and evaluate the underlying grievances that often motivate litigation—but only if Christian conservatives can get past their fears of relativism.

My goal here is not legally instrumental, at least not in a direct way. I do not seek primarily to improve the quality of legal argumentation or to convince lawyers and judges that certain types of legal arguments are better or worse than others. As will become clear in my defense of the concept of worldview as a lens, I believe legal arguments are largely epiphenomenal; they are the specific effects of much more general beliefs and assumptions about the social and political goals that are proper to seek through the legal system and the argumentative means by which those goals should be pursued. In taking seriously the worldview beliefs and assumptions that lie behind the substantive legal positions of Christian conservatives, and in challenging those beliefs and assumptions, my goal is to promote a more humble and productive dialogue outside the courtroom between potential legal disputants. Ultimately, as I argue in the conclusion, if both Christian conservatives and their opponentsFootnote 16 can understand what a worldview is and how it shapes their cultural and social disputes, they might tell their own stories in a way that is more socially and culturally persuasive. This will naturally have effects on what issues they sue over and how they argue in court about those issues. But my main concern is with the social and cultural conversation that lies at the root of the legal conversation.

A Genealogy of the Worldview Concept: Tool versus Lens

As with most contested intellectual concepts, there are nearly as many different definitions of “worldview” as there are different scholars studying the concept.Footnote 17 Still, the definition provided by James W. Sire captures many of the common aspects discussed by Christian worldview scholars. A worldview, he proposes, is “a commitment, a fundamental orientation of the heart, that can be expressed as a story or in a set of presuppositions (assumptions which may be true, partially true, or entirely false) which we hold (consciously or subconsciously, consistently or inconsistently) about the basic constitution of reality, and that provides the foundation on which we live and move and have our being.”Footnote 18

Whether Christian, Buddhist, Islamic, humanist, atheist, or scientific naturalist, everyone has a worldview, asserts Sire, and their worldview answers each of the following seven questions:

1. What is prime reality—the really real? . . .

2. What is the nature of external reality, that is, the world around us? . . .

3. What is a human being? . . .

4. What happens to persons at death? . . .

5. Why is it possible to know anything at all? . . .

6. How do we know what is right and wrong? . . .

7. What is the meaning of human history?Footnote 19

The worldview concept has a rich and interesting history. The English word worldview appears to be a copy of the German word weltanschauung, which was coined by Immanuel Kant.Footnote 20 Several Evangelical scholars, including James Sire,Footnote 21 but also David NaugleFootnote 22 and Albert Wolters,Footnote 23 have traced the evolution of the worldview concept since Kant's time with a great deal of insight into and knowledge of the relevant primary sources. The concept of worldview has also been used and analyzed by scholars in many academic disciplines, including philosophy, sociology, and psychology.Footnote 24 But since my goal is ultimately to uncover how the worldview concept is understood within the Christian conservative community, discussion of those other scholarly treatments is beyond the scope of this article. Nor do I provide my own intellectual history of the worldview concept. Instead, in what follows, I rely mainly on the general contours of Christian scholarship on those aspects of the history and meaning of worldview that matter most to Christian conservatives themselves, citing some of their major texts on the subject and the primary sources those texts rely on. Along the way, I supplement and amplify where necessary, especially to make clear what I see as a crucial distinction between two senses of worldview that Christian scholars have not been attentive enough to: (1) worldview as an instrumental tool that we use to interact with the world and make our place within it; and (2) worldview as a constitutive lens that shapes our understanding of the world—frequently without our even being aware of it.

Worldview as Tool

Kant used the word weltanschauung in his Critique of Judgment as a way of simply describing our “sense perception of the world.”Footnote 25 But very soon the term began to be appropriated by German idealist and romantic philosophers to mean something deeper and more comprehensive. In Johann Gottlieb Fichte's hands, for example, weltanschauung became a term that denoted the perception of “the principle of ‘higher legislation’ that harmonizes the tension between moral freedom and natural causality.”Footnote 26 This intellectual understanding of weltanschauung seems to have become part of the common parlance of prominent German intellectuals of the nineteenth century, including Friedrich Schleiermacher, August Wilhelm Schlegel, Novalis, Jean Paul, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Joseph Görres, Johann Wolfgang Goethe, and others.Footnote 27 By the late nineteenth century, its meaning had become nearly synonymous with philosophy, but without philosophy's rational pretensions.Footnote 28

With Hegel and later scholars, weltanschauung began to transform from a term describing the collective philosophy of a time and place to an individual viewpoint on the world embedded in both the societal and the individual consciousness.Footnote 29 Schelling, for example, used the term to mean something like “a self-realized, productive as well as conscious way of apprehending and interpreting the universe of beings.”Footnote 30 Wilhelm Dilthey used the term in a similar way, beginning with the objective world itself but focusing primarily on the “lived experience” of that world.Footnote 31 He argued that worldview questions—the same ones that continue to animate Christian worldview thinkers today—emerge out of the individual's limited knowledge of the objective historical world: “[W]hat I am supposed to do in this world, why I am in it, and how my life in it will end. Where did I come from? Why do I exist? What will become of me?”Footnote 32

In fact, a specifically Christian worldview is routinely traced back to a group of mostly Reformed theologians who adapted German idealist weltanschauung philosophy from this era— especially of Dilthey's variety—to construct a rational defense of the Christian faith. Scottish Presbyterian theologian James Orr was the first in this line of thinkers.Footnote 33 Quite familiar with weltanschauung philosophy, Orr interpreted the English word, “worldview” in much the same way that Dilthey would soon use the German term, to denote “the widest view which the mind can take of things in the effort to grasp them together as a whole from the standpoint of some particular philosophy or theology.”Footnote 34 For Orr, grasping reality whole meant holding a certain set of propositions to be true and comparing these propositions to those offered by competing worldviews in order to demonstrate the rational superiority of Christianity.Footnote 35 He took great pains to articulate nine of these Christian worldview propositions in the appendix to his first Kerr lecture, “The Christian View of the World in General.”Footnote 36 These propositions are as follows:

1. “[T]he existence of a Personal, Ethical, Self-Revealing God.”

2. “[T]he creation of the world by God, His immanent presence in it, His transcendence over it, and His holy and wise government of it for moral ends.”

3. “[T]he spiritual nature and dignity of man.”

4. “[T]he fact of the sin and disorder of the world . . . which has entered it by the voluntary turning aside of man from his allegiance to his Creator, and from the path of his normal development.”

5. “[T]he historical Self-Revelation of God to the patriarchs and in the line of Israel, and . . . a gracious purpose of God for the salvation of the world, centring in Jesus Christ.”

6. “[T]hat Jesus Christ was not mere man, but the eternal Son of God—a truly Divine Person—who . . . took upon Him our humanity, and who . . . is to be honoured, worshipped, and trusted, even as God is.”

7. “[T]he Redemption of the world through a great act of Atonement.”

8. “[T]hat the historical aim of Christ's work was the founding of a Kingdom of God on earth, which includes not only the spiritual salvation of individuals, but a new order of society.” and

9. “[T]hat history has a goal, and that the present order of things will be terminated by the appearance of the Son of Man for judgment, the resurrection of the dead, and the final separation of righteous and wicked.”Footnote 37

Of course, the theological content of these propositions was not new; Orr restated claims here that have been affirmed by Christians since the early creeds.Footnote 38 Nor was Orr's idea of defending the rational integrity of these claims against their rivals new. This task had been taken up by Christian philosophers and apologists since at least Saint Justin Martyr,Footnote 39 and had arguably been perfected by Saint AugustineFootnote 40 and Saint Thomas Aquinas.Footnote 41 The real novelty of Orr's approach lay in the fact that, notwithstanding his insistence on “a deep and radical antagonism” between Christianity and modernity,Footnote 42 he nevertheless sought to articulate and defend Christian propositions on the ostensibly neutral terms set by the age of “modern science.”Footnote 43 That is, Orr sought to present Christianity as a rational response to the modern, inductive empirical quest for “the unity which pervades all orders of existence,” for a sense of “the coherence of the universe,” and for a grasp of “the one set of laws [that] holds the whole together.”Footnote 44 In other words, Orr proposed the Christian worldview as a rational analytic tool: a system of ideas and practices that Christians could articulate and compare to rival systems such as agnosticism, humanism, social Darwinism, and positivism in order to demonstrate the truth of Christianity and the errors of other creeds and beliefs.Footnote 45

Greatly influenced by Orr's appropriation of weltanschauung philosophy for apologetic purposes, American theologians Gordon Clark and Carl F. H. Henry also began to embrace worldview as a weapon in their struggle against modernist currents in the United States. If Christianity was to meet the challenge of modernism, Clark argued, “it must be explained and defended in comprehensive terms.”Footnote 46 This meant analyzing “history, politics, ethics, science, religion, and epistemology” from a “Christian perspective.”Footnote 47 Since this perspective was “the most comprehensive, coherent, and meaningful” one, he argued, it was “the clear logical choice.”Footnote 48 Similarly, Carl F. H. Henry argued “for a resurgence of Christian perspectives across the whole spectrum of life.”Footnote 49 Defending the Christian worldview against its secular critics, Henry sought to present a rationally compelling alternative that would persuade modern people. In other words, Clark and Henry sought to systematize Christian theological beliefs as a means to an end: to give them an advantage over modern beliefs that they saw as increasingly non-Christian or anti-Christian. This instrumentalist style of apologetics would prove wildly influential for the next generation of American Christian worldview thinkers and activists.Footnote 50

Worldview as Lens

The idea of worldview began as an intellectual “tool”—a comprehensive system of ideas through which society attempted to accomplish the task of objective rational self-understanding. After Hegel, and, particularly, after Schelling and Dilthey, this societal or cultural self-understanding transformed into an individual tool through which people tried to accomplish the task of subjectively making sense of their place in the objective order of society or nature. But when this individualism merged with historicism, it changed the very nature of the worldview idea.

The shift from a collective to an individual philosophy focusing on lived experience was hugely significant because it corresponded with the “rise of historical consciousness.”Footnote 51 Rather than focusing on universal essences and objective metaphysics, as philosophy had since the Greeks, post-Hegelian philosophy focused more on the historical development of ideas and consciousness. The weltanschauung concept aided this transformation because it came to represent “a point of view on the world, a perspective on things, a way of looking at the cosmos from a particular vantage point which cannot transcend its own historicity.”Footnote 52 In this historicist transformation, weltanschauung “forfeits all claim to universal validity, and becomes enmeshed in the problems of historical relativity.”Footnote 53

The individual's lived experience of the world increasingly took center stage in existentialist and phenomenological uses of weltanschauung. Kierkegaard, for example, used a Danish translation of “worldview” along with his own concept of “lifeview” to denote the individual's “natural” and “essential” need “to formulate . . . a conception of the meaning of life and its purpose.”Footnote 54 According to Kierkegaard, one arrives at a satisfactory worldview not through rational reflection and logical development of thought, but through an “unusual illumination about life, which is granted at a kairos moment in one's experience.”Footnote 55 Individual experience comes first, and a worldview is constructed through retrospective reflection on this experience.Footnote 56

Nietzsche, Heidegger, and the whole existential-phenomenological tradition made this connection between lived experience and weltanschauung a central theme. Nietzsche made copious use of weltanschauung, divorcing the term completely from objective reality and anchoring it instead in one's particular perspective—a perspective thoroughly infused with the will to power.Footnote 57 His “complete perspectivism”Footnote 58 denied the objective or universal truth of any worldview.Footnote 59 The truth of any worldview, said Nietzsche, is merely “a mobile army of metaphors, metonyms, and anthropomorphisms . . . illusions about which one has forgotten that this is what they are.”Footnote 60

The father of phenomenology, Edmund Husserl, rejected this Nietzschean perspectivism and all “sceptical historicism” as self-defeating.Footnote 61 He sought instead to separate, or bracket, not only the physical world but also all individual subjective views of the world, including our personal outlook on life, so that we could more clearly apprehend the objects of our consciousness.Footnote 62 Husserl greatly despaired over the advance of weltanschauung philosophy in Europe during his time, seeing it as an unscientific, relativistic, and individualistic accomplishment in contrast to the objective approach to consciousness he championed.Footnote 63

Husserl's most famous student, Martin Heidegger, joined Nietzsche in rejecting the attempt to arrive at an abstract, objective view of reality and in embracing a more perspectivist view. But like Husserl, Heidegger saw existing weltanschauung philosophy as an obstacle to authentic understanding of human existence and its relation to the world.Footnote 64 Indeed, Heidegger used a related term, “world picture” (weltbild), to describe the modern urge to represent the whole of “the world itself; the totality of beings taken” in a way that “stands . . . before us” as an image.Footnote 65 Using a “world picture” meant trying to “place . . . being itself before one just as things are with it, and, as so placed, to keep it permanently before one.”Footnote 66 A modern person characteristically sought to place not only the rest of the world in the picture, but also to “put oneself in the picture,”Footnote 67 Heidegger asserted. But the modern “‘world picture’ does not [really] mean” that we are able to have a true “picture of the world,” including ourselves, in our minds, but rather that we understand “the world grasped as picture.”Footnote 68 In other words, “[w]henever we have a world picture, an essential decision occurs” to turn away from lived experience and toward that portion of life that can be represented.Footnote 69 For Heidegger then, a worldview was really an attempt to objectify and immobilize us at a certain point of understanding our world, whereas Heidegger's own phenomenology sought instead an “always provisional” understanding of our existence from the perspective of “absolute immersion in life.”Footnote 70

Heidegger thus transformed the German concept of weltanschauung by attempting to investigate human existence at a level below Schelling and Dilthey's idea of worldview, as “a self-realized, productive as well as conscious way of apprehending and interpreting the universe of beings.”Footnote 71 But this apprehension and interpretation, Heidegger argued, is “not just a matter of theoretical knowledge . . . held in memory as if it were a piece of cognitive property.”Footnote 72 Instead, understanding of Being arises, Heidegger argued, “in and from ‘the particular factical existence of the human being in accordance with his factical possibilities of thoughtful reflection and attitude-formation.’”Footnote 73 Heidegger sought an understanding of the “structure and its possibilities” of our being as such—not only our ability to represent the world to ourselves in a worldview or world picture, but also our deeper ability to navigate the world in which we are immersed.Footnote 74

Wittgenstein supplemented this phenomenological-existential critique of the old Kantian-Hegelian notion of weltanschauung with a focus on linguistic practices. He agreed with prior worldview thinkers that a “perspicuous representation” of the world “is of fundamental significance.”Footnote 75 But he also agreed with Heidegger that modern versions of weltanschauung problematically vaunt seeing the world over living in the world and miss the fact that our language practices construct a “multiplicity of mutually exclusive world pictures.”Footnote 76 For this reason, Wittgenstein also preferred the term “world picture” to the term “worldview.”Footnote 77 But he defined world pictures differently from Heidegger: as “established patterns of [meaningful] action shared in by members of a group.”Footnote 78 “Language games” arise out of these forms of life, Wittgenstein noted, and give concrete expression to the patterns.Footnote 79 For example, a language of “orders” and “reports” arises out of and implies a military form of life; and a language of “yes and no” answers arises out of and implies a Socratic form of life.Footnote 80

Similar to Heidegger, then, Wittgenstein posited a realm of primary existence or being that lies beneath the level of conscious articulation and representation. This being in the world is the true basis of our understanding how to act, think, and speak. World pictures rest on taken-for-granted “frameworks” and “worldview facts” that are inherited or “swallowed down” from our form of life rather than rationally weighed and verified.Footnote 81

Here, in sum, is the crucial innovation in worldview thinking wrought by this whole tradition: Rather than worldview constituting a rational ground for believing that certain facts are true, we accept certain facts as being true because they are consistent with our worldview.Footnote 82 Comparing worldviews on a purely logical basis is thus ruled out. People do indeed exchange one view for another; but they do so by becoming persuaded to “accept[] in faith” another's picture of the world, not by understanding its logical truth.Footnote 83

This existential-phenomenological-linguistic reformation of weltanschauung philosophy, influenced a host of contemporary social theorists to focus on the tacit, taken-for-granted understructure of worldviews. Charles Taylor, for example, asserts that we make sense of the world and our place within it by interacting with the norms and expectations of others through a “social imaginary.”Footnote 84 This imaginary consists of “the way we collectively imagine, even pretheoretically, our social life.”Footnote 85 A social imaginary “incorporates a sense of the normal expectations that we have of each other; the kind of common understanding which enables us to carry out the collective practices that make up our social life.”Footnote 86 The ways in which people “imagine their social existence, how they fit together with others, how things go on between them and their fellows, the expectations which are normally met, and the deeper normative notions and images which underlie these expectations” structure and guide human actions in a deep way, Taylor argues.Footnote 87

In much the same vein, Peter Berger describes a “plausibility structure,” which tells us what is credible to believe about the world.Footnote 88 “[W]hat people actually find credible” regarding “views of reality . . . depends in turn on the social support these [views of reality] receive.”Footnote 89 The value choices that are embodied in worldviews understood as social imaginaries and plausibility structures are culturally and socially constructed achievements: like all forms of human thought and action, they are situated within particular cultural, linguistic, political, or other contexts.Footnote 90

In contrast to Christian conservatives like James Orr, Gordon Clark, and Carl F. H. Henry, and their progeny, who use worldview as an intellectual tool with which to demonstrate the superiority of the Christian way of life, other Christian thinkers have embraced the idea of worldview as a constitutive lens. This tradition of Christian worldview thinking can be traced back to Dutch neo-Calvinist theologian and politician Abraham Kuyper, who inherited the mantle of neo-Calvinist leadership from James Orr.Footnote 91 Kuyper initially used the Dutch translation of weltanschauung in an instrumental way, arguing that Calvinist Christianity was a complete philosophy “with implications for all of life” including “politics, art, and scholarship.”Footnote 92 In outlining those implications, Kuyper agreed with Orr that Christianity could be presented “as an alternative to . . . [secular] ideologies” and that Christians could use their philosophy to “provide cultural leadership in the modern world.”Footnote 93

But the alternative neo-Calvinist worldview Kuyper eventually juxtaposed to the modern worldview was not a mere analytic tool to compare arguments and evidences; it was a deeper understanding of the “presuppositions” that made these arguments and evidences persuasive for their adherents.Footnote 94 Put in simple terms, “regenerate people” (Christians who are experiencing the life of God) “produce a roughly theistic interpretation of science” (and politics, philosophy, and the like) “and nonregenerate people . . . produce an idolatrous” version of these activities.Footnote 95 The key difference between worldviews for Kuyper and the rest of the presuppositionalist tradition he inaugurated was not the propositional content of the alternative views but rather “the antecedent assumptions that condition all thinking and acting.”Footnote 96 In the hands of Kuyper and the presuppositionalists, the Christian worldview became a lens rather than a tool because of their conviction that “[a]ll theorizing arises out of a priori faith commitments” that lie beneath the surface of rational argumentation.Footnote 97

Herman Dooyeweerd was next in the line of Neo-Calvinist worldview thinkers, and maybe even its “most creative and influential.”Footnote 98 He refined and polished Kuyper's presuppositionalist lens by identifying two basic “ground motives” or spiritual commitments: “the spirit of holiness” and “the spirit of apostasy.”Footnote 99 Out of these two ground motives flow two different ways of living and thinking. Seen in this way, he claimed, a worldview is “not so much a matter of theoretical thought expressed in propositions but . . . a deeply rooted commitment of the heart.”Footnote 100

By thus rooting worldview in a “pre-theoretical” commitment,Footnote 101 Kuyper, Dooyeweerd, and the entire neo-Calvinist tradition (including thinkers like Herman Bavinck, D. H. T. Vollenhoven, and Cornelius Van Til)Footnote 102 appear to have influenced this alternative strand of Christian worldview thinking in a direction substantially close to the existential-phenomenological-linguistic worldview tradition of Kierkegaard, Heidegger, and Wittgenstein. The contrast between the worldview thinking of these scholars and the worldview thinking of Orr, Clark, and Henry is clear. Rather than seeing worldview as a tool or a weapon used to demonstrate the superiority of Christian ideas and practices and to advance or defend it in the cultural marketplace, this other tradition sees worldview as a constitutive lens that conditions and even determines how an individual understands reality, often in an unconscious way. The lens consists of contingent factors such as time, place, language, etc., that deliver the facts of the world to the individual but are by no means universal since the “view” of the “world” will depend on the glasses one wears. Being part of a world is an ontological condition of our seeing anything at all and, as such, cannot be examined and compared to another way of seeing. It can only be lived authentically or inauthentically.

In figure 1, I summarize this historical-philosophical genealogy of the two concepts of worldview visually.

Figure 1 History of worldview concept

The Christian Conservative Legal Worldview: Tool Over Lens

Christian conservative thinkers, activists, and lawyers define and utilize the Christian worldview in ways that are mostly consistent with the top branch of figure 1 as a kind of tool for understanding and acting in the world in a Christian manner. Within the Christian conservative movement, the Christian worldview assumes four distinct instrumental modalities: (1) as a generator of theological, social, and legal ideas; (2) as the scales by which those ideas are weighed against rival ideas; (3) as an incubator of intellectual talent whereby people are socialized into the right mindset and sent out into the political and legal marketplace equipped to spread the Christian worldview to others; and (4) as a synthesizer of Christian legal argumentation, through which the above ideas, comparisons, and conclusions, are applied to concrete legal disputes.

Worldview Idea Generation

One of the primary intellectual purposes of Christian scholars and thinkers writing about and discussing the Christian worldview is to generate and clarify ideas and principles that provide distinctly Christian answers to basic theological, social, and legal questions. As noted above, at the most general level is Sire's list of the seven questions that he claims everyone asks: (1) “What is prime reality—the really real?” (2) “What is the nature of external reality, that is, the world around us?” (3) “What is a human being?” (4) “What happens to persons at death?” (5) “Why is it possible to know anything at all?” (6) “How do we know what is right and wrong?” and (7) “What is the meaning of human history?”Footnote 103

More philosophically and theologically minded Christian worldview thinkers understand the Christian worldview as a means to the end of posing substantive theological answers to these questions. Their answers, to summarize Sire, run something like the following:

1. An infinite personal triune God is the author and source of prime reality.

2. External reality is an originally good creation of God, which has been deformed by human sinfulness.

3. Human beings are rational creatures originally made in the image of God who have also been deformed through sin.

4. At death, all persons are judged by God and based on this judgment either spend eternity in the presence of God (Heaven) or outside the presence of God (Hell).

5. It is possible to know things because God has either revealed them directly in scripture and/or tradition (special revelation) or has revealed them indirectly in nature (general revelation), and because God has created persons with the ability to discern each of these.

6. We know right from wrong because God has given us specific moral commands as well as general moral laws, both of which can be known through the use of human reason.

7. Human history is the story of God's creation and redemption of the world, which includes his miraculous intervention in human affairs over many centuries, culminating in his incarnation, death, resurrection, and glorification, and his invitation for all to share in his divine life.Footnote 104

Moving from these theological worldview ideas to Christian conservative social and cultural ideas, we can easily see the same instrumental dynamics at work. God has created the world a certain way, to operate according to certain natural laws and certain moral laws that are an extension of his own life. Because he wants us to participate in that life, he has given us the capacity to know and follow those laws, which are conducive to our ultimate happiness in this life and the next. It follows, then, according to this Christian conservative understanding, that any human social or political arrangement based on God's moral law is to be valued and promoted by Christians in the interest of the common good, and that any social or political arrangement conflicting with that moral law is to be resisted by Christians for the sake of the common good.

Francis Schaeffer was perhaps the most influential figure in the development of this line of modern Christian conservative cultural and social thought.Footnote 105 A former reformed pastor who in the 1950s established an intellectual retreat and spiritual community for questioning young people in L'Abri, Switzerland, Schaeffer's books traced the advance and retreat of Christian philosophy and social thinking down through the centuries.Footnote 106 He argued that the Christian worldview had fostered and sustained the greatest ideas of the Western sociopolitical tradition, but that these ideas were now being challenged and undermined by an anti-Christian worldview, animated by a different set of presuppositions than the ones listed above.Footnote 107 Especially in the 1970s and 1980s, Schaeffer argued for a revivification and defense of social and political action consistent with the Christian worldview, especially in the areas of political philosophy, law, and the arts.Footnote 108

Many Christian conservatives accepted Schaeffer's challenge to translate their theological beliefs into articulate and clear Christian sociopolitical ideals that could compete with and defeat secular worldviews on the cultural battlefield. Schaeffer's influence on contemporary Christian worldview thinkers and activists is illustrated well by Charles Colson's and Nancy Pearcey's book, How Now Shall We Live? The title itself is a play on the words of Schaeffer's famous book title, How Should We Then Live? Colson's dedication to the volume reads as follows: “We dedicate this book to the memory of Francis A. Schaeffer, whose ministry at L'Abri was instrumental in Nancy's conversion and whose works have had a profound influence on my own understanding of Christianity as a total worldview.”Footnote 109 The content of the book provides a detailed and exhaustive catalogue of answers and action plans that the authors generated based on their understanding of the Christian worldview. Addressing a host of issues like test-tube babies, creationism, abortion, sex education, substance abuse, poverty, foreign policy, and even music and pop culture, the book even includes a detailed appendix listing hundreds of other books addressing every issue imaginable from the perspective of the Christian worldview, categorized by issue area.Footnote 110

Christian worldview-oriented centers and ministries pick up where books like this leave off, dispensing practical worldview advice in classes, seminars, podcasts, and webinars. The Colson Center for Christian Worldview, for example, identifies itself online as “a ministry that equips Christians to live out their faith with clarity, confidence, and courage in this cultural moment.”Footnote 111 Summit Ministries is another great example: Its “mission is to equip and support rising generations to resolutely champion a biblical worldview.”Footnote 112 That “biblical worldview” includes, in addition to all the theological answers sketched above, the conviction that, when government “oversteps its bounds by failing to recognize the value of each person, or by constraining conscience, or by calling good what God calls evil and calling evil what God calls good, we must call it to account.”Footnote 113

Some of the main social and cultural principles generated by the Christian worldview were encapsulated well by the authors of the Manhattan Declaration, who affirmed three basic ideas: (1) people are created in the image of God and so they possess inherent dignity and the right to life; (2) marriage is a conjugal union of one man and one woman, and is the most basic building block of society; and (3) religious liberty, or the right of all people to believe and practice their faith, is inherent in God's nature and in the nature of the human person.Footnote 114

More concretely, Christian conservatives use the Christian worldview to generate legal principles that flow naturally from some of the above social and cultural principles. At the most general level, Christian conservatives believe that the Christian worldview “includes a distinctive and identifiable Christian view of law.”Footnote 115 They begin with the premise that God's eternal law is the foundation for all human law such that the latter cannot be legitimate unless it accords with the former.Footnote 116 In keeping with earlier worldview thinkers like James Orr, contemporary Christian conservatives also argue that “a society inevitably must choose between” Christian legal principles and merely human legal principles.Footnote 117

In these ways, Christian conservative thinkers and activists treat the Christian worldview as an analytic tool to generate distinctly Christian understandings of reality, society, and law.

Worldview Comparison

Once Christian conservative thinkers have settled on theological, social, and legal ideas, they also use the Christian worldview instrumentally to rationally compare their ideas with those of other worldviews. In fact, this focus on the rational comparability of different worldviews seems to be at the very center of Christian worldview thinking. Theologically and philosophically, for example, James Sire's The Universe Next Door, one of the most popularly cited worldview texts among Christians, carefully catalogues the substantive claims of various worldviews like “deism,” “naturalism,” “nihilism,” and “postmodernism” and tries to demonstrate the intellectual differences between them and Christianity.Footnote 118 Mary Poplin does something similar in her book Is Reality Secular? although she goes much further in defending the rational superiority of the Christian worldview against these other claimants.Footnote 119

Moving beyond theological and philosophical analysis, Francis Schaeffer engaged in a pioneering comparison of the cultural and artistic effects of the Christian worldview to the cultural and artistic effects of other worldviews. For example, he attempted to demonstrate that modern art, including music, poetry, painting, and literature, demonstrated the futility of Western culture's increasing desperation and aloneness.Footnote 120 But, for Schaeffer, art and popular culture only illustrated the devolution of social practices, such as sexuality, education, and law, as human beings increasingly cut themselves off from the objective, biblical source of divine human meaning and embrace alternative worldviews like existentialism and nihilism instead.Footnote 121

Taking up this same instrumental project of comparing how society looks when guided by a Christian worldview to how it looks when guided by non-Christian worldviews, Colson and Pearcey compare the transcendent, objective social standards of the Christian worldview against the subjective relativism of worldviews such as multiculturalism, pragmatism, utopianism, and postmodernism.Footnote 122 Their overall goal here is to “understand the great ideas that … inform the mind, fire the imagination, move the heart . . . shape a culture” and “move us to act.” Rational comparison of the social implications of these worldviews is essential, they argue, precisely because these social ideas lie beneath the legal controversies in which Christian conservatives are engaged: ‘The culture war is not just about abortion, homosexual rights, or the decline of public education. These are only the skirmishes. The real war is a cosmic struggle between worldviews—between the Christian worldview and the various secular and spiritual worldviews arrayed against it.’Footnote 123

Legal philosopher and Christian apologist Francis Beckwith is another good example of a thinker who uses the Christian worldview as a tool for objectively comparing and defending Christian conservative social positions against rival ones. In fact, the main goal of his book Taking Rites Seriously is to show that legal claims motivated by Christian faith are not only rational and defensible but that they have great instrumental value in supporting a flourishing liberal society.Footnote 124 For instance, Beckwith defends the Christian conception of human dignity against its materialist critics, and he applies this conception to socio-cultural debates over issues like embryonic stem cell research and abortion, showing in each case how the Christian conservative position is rationally superior to the alternatives.Footnote 125 More specifically, Beckwith defends a Christian understanding of human nature against both the worldview of scientific materialism and the worldview of secular liberalism, drawing out the ways that the Christian worldview generates better answers on education, same-sex marriage, adoption, and public accommodations.Footnote 126

In this comparison between conflicting social foundations, Christian worldview thinkers conclude that the Christian view of society and law is “vastly superior to all alternatives: it is empirically defensible, internally logical, [and] comprehensive in scope.”Footnote 127 In keeping with earlier worldview thinkers like James Orr, contemporary Christian conservatives also argue that “a society inevitably must choose between” Christian socio-legal principles and merely human ones.Footnote 128

Worldview Talent Incubation

Countless Christian ministries, churches, and other organizations engage in practical worldview training courses, workshops, seminars, and other encounters. At the theological level, groups with names like the “Biblical Worldview Institute”Footnote 129 and “Worldview Matters”Footnote 130 offer courses such as “Worldview Basics”Footnote 131 and “The Worldview Course”Footnote 132 with the mission of training people to understand and utilize the answers provided by the Christian worldview, compare Christian answers to those of other worldviews, and demonstrate the superiority of the former.

Translating Christian worldview ideas onto the social level, one group even offers a worldview testing instrument that purportedly measures the match between a Christian's personal beliefs and the Christian worldview in “five key areas: Politics, Economics, Education, Religion and Social Issues [PEERS].”Footnote 133 Like “an eye chart at the doctor's office,” they note, “the goal isn't to beat the test, but to identify where there's room for improvement. PEERS is about bringing all of life into focus through the objective standard of God's word.”Footnote 134

Reaching a broader audience than do these smaller Christian ministries, some of the national social and political organizations already mentioned also offer worldview training. The Colson Center offers the Colson Fellows Program, which “equips Christians with a robust Christian worldview so they can thoughtfully engage with post-Christian culture, inspire reflection in others, and work effectively toward re-shaping the world in the light of God's kingdom.”Footnote 135 Summit Ministries is probably the biggest organization conducting such training and the one with the greatest reach. It holds a variety of seminars and training programs, including a renowned residential summer program aimed at teenagers, and they publish Christian school curriculum aimed especially at teenagers and young adults, educating them, in part, to “defend a Christian worldview against other belief systems” and to use that worldview to “stand for truth and justice.”Footnote 136

Moving from theology to society to law, some Christian conservative legal organizations also train young people to become social and legal activists who know how to translate the Christian worldview into practical action. For example, Alliance Defending Freedom runs the Areté Academy, “a one-week leadership development training program for highly accomplished college students and recent graduates who are interested in future careers in law, government, and public policy.”Footnote 137 In this program, “[d]elegates . . . engage the foundations of law and justice, natural law principles, and biblical worldview training [and] explore how these foundational principles apply to some of the most pressing issues facing society today, including religious freedom, intellectual tolerance and academic diversity, marriage and family, as well as the right of conscience and the sanctity of life.”Footnote 138

These sorts of worldview training programs do not just propagate and teach ideas consistent with the Christian worldview. They socialize people into the Christian worldview as a way of life. None of this practical training would be necessary if these groups thought of the Christian worldview as a preexisting lens through which Christians see the world. Training is seen as necessary because these ministries and groups assume that the Christian worldview is an externally acquired tool with which trainees need to be “equipped” so that those trainees can, in turn, use that worldview tool to “re-shape” the world.

Worldview-Legal Argument Synthesis

Moving from theory to practice, Christian conservative groups and leaders use their worldview as an intellectual tool for connecting Christian theological and social ideas to live legal controversies. The Colson Center, for example, often urges Christians through its radio program and blog Breakpoint to apply worldview ideas in favor of or against substantive legal positions.

A recent Breakpoint episode, for example, recounted particular cases involving Christian photographers from Wisconsin and Minnesota, a Christian t-shirt maker from Kentucky, and Christian bakers from Washington and Colorado.Footnote 139 All of these cases involved Christians who defied state civil rights laws by refusing to provide products and services to gay customers seeking to use those products or services in an activity the Colson Center finds contrary to the Christian worldview. These cases, says the Breakpoint host, “point to the enormous importance of the [then-pending] Supreme Court case, Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission [which] might very well be the religious freedom equivalent of Roe v. Wade.”Footnote 140

Another major example of the Colson Center translating the Christian worldview into a legal position was their 2017 statement in opposition to sexual orientation and gender identity (or SOGI) laws protecting gay and transgender people from public and private discrimination.Footnote 141 The statement began with an affirmation of one of the principles discussed above, coming from the Christian worldview idea-generator, regarding sexual identity and gender expression: “[P]eople are created male and female, [and] this complementarity is the basis for the family centered on the marital union of a man and a woman, and . . . the family is the wellspring of human flourishing.”Footnote 142 Having established the correct principles and ideas, the Colson Center then moved to a discussion of how to apply those principles and ideas: Christian “professionals, wedding chapels, non-profit organizations, ministries serving the needy, adoption agencies, businesses, schools, religious colleges, and even churches,” they informed the reader, who hold to Christian conservative views of sexuality, gender identity, and marriage, are increasingly being subjected to “personal and professional ruin, fines, and even jail time.”Footnote 143 Because of this conflict between the demands of the Christian worldview and the demands of the alternative worldview underlying SOGI laws, the Colson Center's statement concludes, “SOGI laws . . . threaten fundamental freedoms, and . . . should be rejected.”Footnote 144

Christian conservative law firms and legal groups perfect this instrumental modality of the Christian worldview by bringing lawsuits and making legal arguments on behalf of Christian conservative parties. Groups like the American Center for Law and Justice, the Alliance Defending Freedom, Liberty Counsel, and other legal organizations are daily engaged in the work of Christian worldview litigation.Footnote 145 For example, before he made the news as President Trump's personal lawyer, Jay Sekulow founded the American Center for Law and Justice, and he described its mission as defending people “who have a Christian worldview [and] are facing significant harassment and discrimination.”Footnote 146

Through these and other lawyers and law firms, Christian worldview ideas find their way into legal briefs filed in cases of interest to Christian conservatives. For example, in the years before the Supreme Court established the constitutional right of same-sex couples to marry, several Christian Conservative organizations filed amicus briefs in Hollingsworth v. Perry Footnote 147 and United States v. Windsor,Footnote 148 both of which involved challenges to bans on recognizing same-sex marriage. One brief articulated a series of substantive theological positions informed by the Christian worldview, and then compared that worldview with a rival worldview:

Christianity teaches that God affirmed sexuality as a fundamental element of the created order when He created male and female in His image (Genesis 1:26–27, 2:7, 2:18–23). He ordained their union in the covenant of marriage, to bear children and instruct them in His law (Genesis 2:24–25; Deuteronomy 4:9–10). New Testament Scripture draws an analogy between husband-wife and Jesus Christ's relationship to His church (Ephesians 5:31–32). For many Christians, erasure of the male-female distinction is tantamount to a pantheistic worldview that blurs the distinction between God the Creator and His creation, and homosexuality is not a minor aberration.Footnote 149

In Obergefell v. Hodges, where the Supreme Court finally established a same-sex marriage right, a number of amicus briefs by Christian conservative organizations followed the same line of logic, using substantive elements of the Christian worldview to support legal arguments against rival claims.Footnote 150 One amicus brief, filed by Texas Values, illustrates the way that the concept of worldview can be used as a tool to explain and compare the different legal outcomes preferred by each side:

The disagreements over whether same-sex marriage should be legal arise from differences in value judgments. . . . The petitioners’ arguments are based on the ideology of the sexual revolution, which views marriage and human sexuality as existing primarily for love and personal fulfillment. Same-sex marriage follows naturally from that worldview. . . . Others, however, believe that marriage and human sexuality should be used primarily to generate positive externalities for society. . . . [This view] is correlated with religious belief, and this is unsurprising given that most faith traditions teach their adherents to exalt the needs of others and society over individualized pursuits of happiness or personal gratification.Footnote 151

The same pattern can be observed in the religious exemption cases, starting with Burwell v. Hobby Lobby.Footnote 152

Of course, it makes sense that Christian conservative individuals and groups might mention the Christian worldview as evidence of their religious reasons for refusing to engage in actions that they consider sinful, such as funding insurance policies that cover birth control and/or abortion. As a group of Christian radio and television broadcasters noted, for example, in their Hobby Lobby amicus brief, “[t]he fact that some Americans, or even many of them, no longer integrate a Bible-centered, Christian worldview into their everyday lives does not change the fact that the owners of Hobby Lobby and Conestoga, as well as many others who operate closely held companies, still do.”Footnote 153 But the broadcasters went further in their brief, identifying the Bible-centered, Christian worldview as the main historical foundation for the religious conscience protections built into the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment. Citing John Jay's comments as the head of the American Bible Society and Alexis de Tocqueville's observations of the place of Christianity in early American life, the broadcasters argued that the Christian worldview was not only “vibrant and pervasive” at the time of the writing of the First Amendment, but also that the Christian worldview is “joined at the hip” to legal protections of religious liberty under US law.Footnote 154 Therefore, “[t]he restraining force of religious conscience upon the practical, business decisions and actions of the owners of Hobby Lobby and Conestoga is in keeping with the earliest American experience, and must surely be deemed to be part of the ‘historical function’ of the guarantee of free exercise, going back to the Founding.”Footnote 155

More recently, in Arlene's Flowers, Inc. v. Washington,Footnote 156 where a Christian florist was suing to overturn state fines punishing her for refusing to serve a gay couple, the Family Research Council co-filed an amicus brief, identifying itself as an organization “that exists to advance faith, family and freedom in public policy and the culture from a Christian worldview.”Footnote 157 They then argued on the basis of the Christian worldview that Christian business owners have a First Amendment right to be exempt from obeying civil rights laws.Footnote 158 Just like the Christian broadcasters had argued in Hobby Lobby that the Christian worldview had shaped the American conception of religious liberty, the Family Research Council argued in Arlene's that the Christian worldview has “shaped views of sexual morality for centuries,” such that “[g]overnment has no right to legislate a novel view of sexual morality and demand that religious citizens facilitate it.”Footnote 159

This trend of Christian conservatives using their worldview as a tool to achieve legal leverage continues to the present. Just last year, in a trio of cases, the Supreme Court decided that Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which prohibits employment discrimination “on the basis of sex,” protects gay and transgender individuals.Footnote 160 Over forty religious colleges and universities, most of them Christian institutions, filed an amicus brief in those cases, in which they noted their obligation to defend a “Christian worldview” and, on the basis of that worldview, argued against the proposed interpretation of Title VII.Footnote 161

In sum, then, Christian conservatives heartily embrace the idea of worldview as a tool. That is, they believe that their worldview is a comprehensive and systematic set of propositions that provides answers to all relevant metaphysical and theological questions as well as all social, political, and legal questions. Further, Christian conservatives believe that this worldview can be objectively compared to other rival worldviews that offer competing answers. When this comparison is made, they believe, the Christian legal worldview will be vindicated as intellectually and legally persuasive. They actively seek to train people to engage in this intellectual and legal vindication, and this training eventually bears fruit in court cases and legal briefs where Christian conservative lawyers use these worldview ideas to persuade judges of the legal merits of Christian positions. Whether Christian conservatives win or lose in court, their practice of treating the Christian worldview as a tool or instrument that is superior to other worldviews resembles a kind of intellectual arms race that continually spills over into actual conflict on legal issues such as religious freedom exemptions, abortion restrictions, transgender rights, and many other issues.

Assessing the Christian Conservative Legal Worldview: Lens over Tool

Along with my discussion above of Christian worldview culture and the way that this culture provides the intellectual and social infrastructure of Christian conservative litigation, below I offer an assessment of the instrumental way Christian conservatives employ the concept of worldview. In making this assessment, I have tried to steer clear of two extremes. On the practical level, this assessment is not a direct attempt to convince Christian conservative activists or their lawyers to change the substantive legal arguments they make in court. Such legal arguments are intentionally instrumental for a good reason: the lawyer's job is to use argument as a means of persuading the court to rule in a manner favorable to the interests of the client. In critiquing the instrumental logic of Christian conservative worldview thinking, I seek to confront the more general logic and the theoretical assumptions that lie behind such legal arguments. A change in this logic or these assumptions may indirectly have the practical effect of changing the substance of Christian conservative legal argumentation, but in ways that are beyond the scope of my analysis. But neither is my assessment of Christian conservative worldview thinking merely an abstract, conceptual exercise. Taking the infrastructure of Christian conservative social and legal ideas seriously, and pointing out their flaws, will help demonstrate how the Christian conservative relationship and dialogue with the rest of the culture outside the courtroom could be improved. Indeed, by changing their conception of worldview, Christian conservatives might actually make their way of life more persuasive to those subscribing to other worldviews. At a minimum, my goal is to show that replacing the concept of worldview as a tool with an understanding of worldview as a socially constructed lens makes more sense and is truer to the humanity of those involved on both sides of the discussion.

Critiquing the Christian Worldview's Instrumental Logic

The general concept of worldview has not been universally embraced by Christian thinkers and scholars.Footnote 162 Some critics have rejected worldview thinking wholesale, arguing that its inherently philosophical orientation is antithetical to the Christian way of life.Footnote 163 Other thinkers, while not rejecting the concept of a Christian worldview entirely, have nevertheless been critical of an overly broad formulation of the Christian worldview as a single system of metaphysical ideas that one can access through a transcendent mode of reason.Footnote 164 Still others have taken this critique of totalism and transcendent logic a step further, arguing that all views of the world, including the Christian view, are products of contingent cultural and historical perspectives.Footnote 165

These are compelling critiques of the Christian worldview idea in the abstract, but they are almost uniformly aimed at the Christian use of worldview as a tool. Too little attention has been paid to the implications of seeing the Christian worldview as a lens, and as far as I know, no attention has been paid to the implications of this alternative understanding of worldview for Christian conservative social, political, and legal activism. In what follows, I adapt the existing critiques of an instrumentalist conception of worldview to Christian conservative legal logic. But rather than reject worldview thinking outright, I defend an alternative version of worldview as a contingent, socially, and culturally constructed lens. As I demonstrate, this alternative understanding of worldview as a lens is compatible with the authentic aims of Christianity. Even more, by appreciating the contingent, partial manner in which we humans come to know things and establish standards of credibility, understanding worldview as a lens may be the only way to respect Christianity's fundamental injunction to respect the dignity of the other as a person created in the image of God.

Using worldview as a tool, on the other hand, is less a Christian project than it is a modernist project: it commits its adherents to “a subject/object dichotomy and a dualistic relationship with the world.”Footnote 166 Using a worldview as an intellectual tool for generating answers to theological, social, and legal questions, comparing those answers to others, training others in those answers, and synthesizing those answers into legal arguments assumes the ability of the person using the tool to transcend their existing worldview, assuming a neutral and objective stance on reality. For example, the reason I would need to become “equipped” with a particular worldview is because I am not already equipped with it, meaning that I stand outside of it in some way. For someone who is already a Christian to become so “equipped” would mean setting aside their already existing way of thinking and taking on a new way of thinking. But even seeing the need to take on a new way of thinking requires an ability to transcend the old way of thinking—to stand apart from it at least enough to be able to judge its soundness. The same is true for comparing one worldview to another. I have to be able to stand apart from my worldview, assess the evidence for the claims of alternative worldviews, and decide which one is superior. Even in the case of a more gradual and fluid transition from partial acceptance of a worldview to a more complete acceptance of it, the worldview holder must still be able to stand aside from it enough to judge its completeness. On the other end of the process, in order to pass on a worldview in a training session or in a legal brief, I have to be able to stand aside from that worldview enough to be able to evaluate its value and usefulness.

But the neutral space required to perform these instrumental worldview moves, along with the neutrality and objectivity necessary to pull them off, simply does not exist. A worldview is not something I can stand apart from, but something in which I am always enmeshed, something that constitutes the unarticulated background precondition for my knowing anything in the first place.Footnote 167 A worldview is coextensive with “the totality of the culturally structured images and assumptions . . . in terms of which people both perceive and respond to reality.”Footnote 168 Even a worldview held by an individual “is communal in scope and structure” because it results from community expectations and norms about what it is appropriate to believe, do, and say.Footnote 169 Since the “basic tenets” of a worldview “are not argued to but argued from”Footnote 170 in this way, we cannot arrive at the right understanding of marriage or sexuality, for example, as we would calculate the proper weight-bearing tolerance of steel for a bridge. We simply do not have that kind of “present-at-hand” access to the value and qualities of these social practices that we do with objects in the world.Footnote 171

The persuasiveness of this lens-like understanding over the instrumental view cannot be demonstrated through an objective, propositional, approach. That would be self-refuting because it would employ the same sort of transcendent logic that the lens-like understanding denies. Instead, in what follows, I illustrate the persuasiveness of worldview as a lens by describing its negative and positive implications for assessing Christian conservative socio-legal claims—showing how it rules one project out but leaves open the possibility of another.

What We Cannot Do: Objectively Compare Worldviews

The impossibility of objectively comparing worldviews in the way Christian conservative activists seek to do becomes apparent once we examine their claims more closely. To do this, I examine two socio-legal issues of great importance to Christian conservative legal activists: opposition to SOGI laws and support for religious conscience protections. The stand that Christian conservative activists take on both issues is based on several premises that lead to particular legal conclusions. Consider the Colson Center's argument, for example, which runs as follows:

1. People have a fixed biological sex—they “are created male and female.”

2. This fixed biological sex corresponds to a fixed biological and social relationship—“the family centered on the marital union of a man and a woman.”

3. This fixed biological/social relationship is necessary for societal survival—“the family is the wellspring of human flourishing.”

4. New anti-discrimination laws punish people and organizations who prefer this fixed biological/social relationship—they are increasingly being subjected to “personal and professional ruin, fines, and even jail time.”

5. Therefore,

(a) these laws threaten societal survival and “should be rejected” or

(b) Christians should be exempted from them.Footnote 172

In this argument, the Christian worldview could act as a tool—an intellectual device that rationally demonstrates the superiority of the Christian position—only if it were possible to take up a position outside of any worldview and examine the evidence for the propositions contained within different worldviews. And this is precisely what many Christian conservative legal groups purport to do in speeches, interviews, legal briefs, and other writings: they point out the overwhelming and incontrovertible evidence that male and female biological sexes actually exist, that the vast majority of people have one or the other before they are even born, that heterosexual marriage and parenting have been the norm for centuries, and so on.Footnote 173

But the real question is not whether evidence for these propositions could be adduced. The real question is what legitimately counts as evidence in favor of or against these prevailing cultural norms. And what counts as evidence will depend on one's background presuppositions and assumptions about the world—in other words, the way one's worldview acts as a lens to enable one to see some things and not others as significant and persuasive.

Christian views of sexuality, gender identity, and marriage are presented in articles, books, and legal briefs by Christian conservatives as ideas and practices that should be preferred because they are more in touch with the reality of how things actually are. Thus, we are told that, for the Christian worldview, marriage, government, and church are not merely social constructions that can be shaped in any way . . . but rather are natural institutions in which and by which human beings ought to learn what is good, true, and beautiful. . . . They are part of the furniture of the universe, and their continued existence is essential to maintaining the moral ecology of human society.Footnote 174

The same is true for issues like abortion, religious conscience protection, lower taxes, and a host of other positions: these positions are not presented as the products of a dialogue where people from different worldviews interpret reality as they see it, but rather are presented as the practical implications of a factually accurate and comprehensive understanding of how the world really is.

Consider, though, how the same issue—antidiscrimination laws protecting sexual and gender expression or identity—looks through the lens of an alternative Queer Theory worldview. For a person situated within this worldview, the evidence cited by Christian conservatives concerning the existence of biological sex and reproductive complementarity is merely an illustration of how culturally powerful the discourse about binary sex and gender categories has become. However, according to Nikki Sullivan, Queer Theory opposes the notion that sexual identity, gender identity—or any other identity for that matter—is a clear and unambiguous result of physical reality.Footnote 175 Queer Theory seeks to subvert all binary divisions and to demonstrate the inherent instability of all seemingly natural distinctions,Footnote 176 seeing “the existence of transparent, natural, timeless, and purely descriptive” identity categories like male/female and even homosexual/heterosexual as “a modernist myth.”Footnote 177 As for external behavior and action, its “forms, meanings, and social formations . . . are culturally and historically contingent.”Footnote 178 Rather than being fixed, “identity and subject position are multiply determined, dynamic, and fluid.”Footnote 179

For Queer Theory, “the existence of a unitary and coherent” gay, straight, homosexual, heterosexual, male, or female category is an illusion.Footnote 180 Indeed, Queer Theory, at least in the hands of leading legal theorists like Susan Burgess, “contends that there is no tidy resolution of the problem of sexual identity” because the “instability of identity” in general and the exercise of social power “make stable resolutions of that sort impossible.”Footnote 181 Instead of “identifying an authentic self” upon which policies and laws may be staked, “queer theorists opt for creating performances that reveal the irony of the search for the authentic self and the ideal political order.”Footnote 182 The creation of such ironic performances plays such a big role because of the more basic Queer Theory claim—building on Simone de Beauvoir's foundational insight—that identity itself is performative through and through.Footnote 183

While binary terms like male and female or heterosexual and homosexual may appear natural, obvious, objective, and universal, Susan Burgess and other Queer Theorists claim that these distinctions are instead contingent products of specific times, places, communities, and circumstances.Footnote 184 Communities and groups “tend to reproduce themselves” and so preferred categories like male and female prevail over time, making “the meaning of their central binaries appear to be given or natural, rather than politically contingent.”Footnote 185 This, Judith Butler argues, is why the evidence of traditional male and female roles seems so strong even though such identities are really quite plastic: because the performance of these roles helps to regulate and channel sexuality in ways that further biological reproduction and reproduction of the gender hierarchy and power dynamic.Footnote 186

Given the performative quality of all identities, a Queer Theorist might argue, SOGI laws make perfect sense. Such laws create a legal space that protects the ability to experiment with the construction of and performance of new identities. Such laws also partially disrupt the (re)production of binary social identity categories by suspending the social privilege associated with adhering to and promoting these categories.

Deciding between these Christian conservative and Queer Theory worldviews as applied to the new antidiscrimination laws cannot involve neutrally comparing evidence for and against their claims and logically deducing the correct policy option. In fact, Christian conservatives and Queer Theorists have very different ontological ideas about what is real and very different epistemological ideas about how logic works in this context. As for what is real, Christian conservatives assume an essentialist ontologyFootnote 187 by claiming that certain human traits and qualities, such as biological sex, gender expression, sexual complementarity, heteronormativity, etc., are real truths about human beings that transcend cultural and individual preferences. Queer Theorists, by contrast, have an anti-essentialist view of these same traits and qualities, seeing them as socially constructed discourses that privilege one identity performance over others that are equally valid. As for logic, Christian conservatives prefer a foundationalist epistemology,Footnote 188 constructing legal conclusions (opposition to SOGI laws and support for religious exemptions to those laws) based on what they believe are objective truths. Queer Theorists, on the other hand, adopt an anti-foundationalist epistemology, using reason in an ironic and playful way to deconstruct the apparent objectivity of truth claims and legal outcomes, attempting to demonstrate the subjectivity of these things.

The difference between these two ontological and epistemological views on the issue of SOGI laws is just one example among many that could be given to demonstrate the futility of the Christian conservative idea of worldview as a tool—a way of rationally and neutrally comparing claims. Demonstrating the superiority of one substantive legal claim over another would require, first, proving to the other side that a wholly different view of reality and logic are superior to the views they already hold. But there is no neutral space of no reality in which someone can exist while they choose which alternative vision of reality they prefer.Footnote 189 Relatedly, the only ways to choose between two alternative forms of logic are to adopt a third form of logic or to choose in a non-logical way. Both choices, between different visions of reality and between different forms of logic, can still be made, but the crucial point is that the choices can only be made by using criteria for evaluation that exist independently of the options being chosen between. But those criteria are not free-floating outside of any worldview; they are themselves based on certain assumptions and convictions about reality and certain ways of knowing and thinking about that reality. Thus, Christian conservatives are right that the controversy between themselves and the LGBTQ community, like so many other controversies that plague our culture, is premised on a deeper conflict between different worldviews. But they are wrong to think that these worldviews can be objectively and neutrally compared to one another. Any sort of comparison and evaluation of worldview lenses would involve the use of another, different worldview lens consisting of different commitments and presuppositions about what counts as evidence and different ways of reasoning based on that evidence.Footnote 190

What We Can Do: Listen and Learn

The fact that we have different worldview lenses does not mean that communication and persuasion are impossible. To facilitate this communication and persuasion, some Christian critics of modern worldview thinking have embraced a postmodern understanding of worldviews as cultural and historical perspectives on reality and have abandoned the search for a single, unified knowledge of all reality.Footnote 191 Such perspectivism, including the acknowledgment that Christian conservatives and their antagonists both begin from a particular socially and historically constructed place, is a helpful antidote to the instrumental understanding of worldview. But perspectivism can be just as much of a dead end as instrumentalism if we focus only on the fact that we each have a perspective and do not focus on the substance of what each of us sees through our perspective. The perspectives of foundationalism and essentialism certainly matter to Christian conservatives as the seemingly necessary philosophical conditions for making and recognizing true statements about reality. But while philosophical conditions can enable someone to know the truth about God, nature, sexuality, gender, marriage, and the like, philosophical conditions cannot bring about a personal encounter with, and acceptance of, these truths. Similarly, the perspectives of anti-foundationalism and anti-essentialism matter to many in the LGBTQ community as the seemingly necessary philosophical conditions for rejecting traditionally accepted gender and sexuality norms and opening up a space for repressed identities to emerge and flourish. But while philosophical conditions can enable this critique and clear the way for new expressions, they cannot bring about the personal understanding and acceptance of new identity claims that the movement most desires.