INTRODUCTION

In terms of the known corpus of painted mural art from Epiclassic Xochicalco (ca. a.d. 650–1000), three benches, which have so far received surprisingly little attention, play an important role in understanding the once vibrant tradition of mural painting at the site. The beautiful execution, color scheme, and iconographic content of these benches strikingly evoke the splendour of the paintings that once embellished several of Xochicalco's structures (Garza Tarazona et al. Reference Tarazona, Silvia, León and Limón2009:24).

The focus of this study is thus on the benches found within the monumental epicenter of Xochicalco. Additional bench-like features have been uncovered in two residential sites, on the lower terraces of the Cerro Xochicalco, during excavations directed by Hirth. These are features designated as H-F30 and K-F27, which exhibit talud-tablero profiles as well as red-painted designs, and are discussed at length by Hirth and Webb (Reference Hirth, Webb and Hirth2006). Thus, despite the emphasis on the polychromatic benches of the epicenter, the presence of benches in various architectural contexts speaks of a polyvalence of functions as well as architectural features that crosscut social and hierarchical boundaries. Nevertheless, we surmise that these benches are analogous to those found within the monumental epicenter, having equally served as seats of power for the respective heads of households.

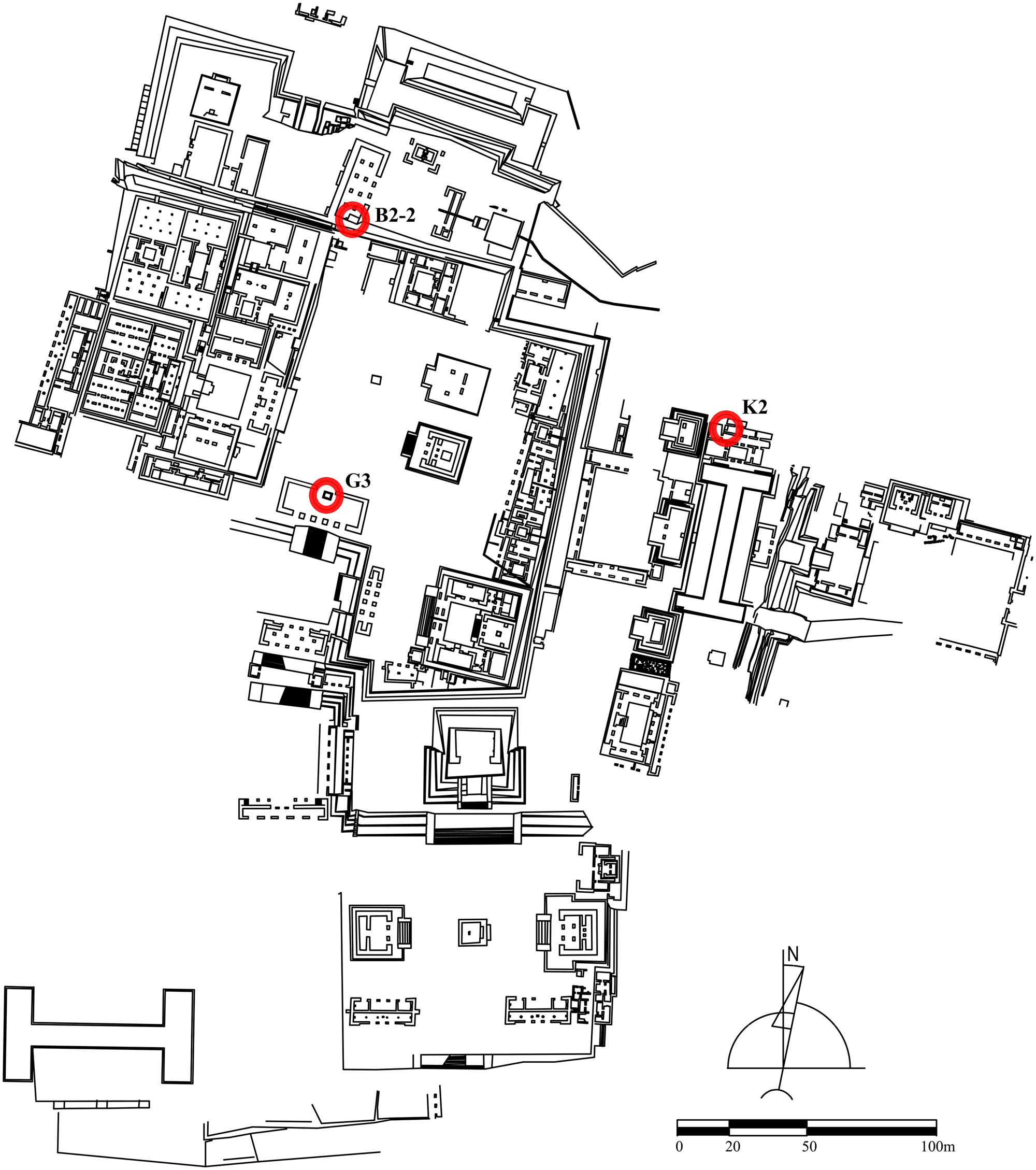

The three stuccoed and painted benches that we will focus on were found in Structures B2-2, G3, and K2 (Figure 1) have only been described briefly in the existing literature, almost in passing, and with little attempt of further analysis or interpretation (Garza Tarazona Reference Garza Tarazona2015b; Garza Tarazona and González Crespo Reference Garza Tarazona, Crespo and Wimer1995:120–123; Solís Reference Solís and la Fuente1999:135–136). In the present work, we provide a basic documentation of the three benches, along with a detailed description and analysis of the imagery and text of the benches. Although these display very different designs and imagery, the iconographic themes of the three benches can all be said to center on authority and its mythological, religious, and sociopolitical foundations. The glyphs accompanying a row of individuals depicted on the bench Structure K2 add significantly to the existing corpus of named individuals at Xochicalco (see Helmke and Nielsen Reference Helmke and Nielsen2020) and, together with the recently published studies of a recently discovered Epiclassic stela from nearby Tetlama (Garza Tarazona Reference Garza Tarazona2015a; Helmke et al. Reference Helmke, Nielsen and Guzmán2017), it consolidates the role of public and semipublic monuments in displaying the mythological origins and the power of the Xochicalco ruling elite.

Figure 1. Map of the site of Xochicalco, showing the location of the structures and associted benches discussed in the text. Map by Claudia I. Alvarado León, courtesy of Silvia Garza Tarazona and the Proyecto Arqueológico de Xochicalco.

What we here designate as benches have mostly been referred to as “altars” in the existing literature on Xochicalco, and thus a few words on the terminology applied to these small, low platforms are in order. Essentially, we are dealing with low platforms that are built abutting the walls or terraces of a building (although some examples are free-standing), and they have the appearance of a bench or seat rather than an altar, and hence used as places where humans were seated, or objects were placed (see discussions in Boot [Reference Boot2000, Reference Boot2005:389–416], Harrison [Reference Harrison1970, Reference Harrison, Inomata and Houston2001], Kaplan [Reference Kaplan1995], and Noble [Reference Noble1999]). It is highly uncertain if they were used as altars in the sense that they were involved in ritual actions involving offerings or sacrifices, and to our knowledge, there is no concrete evidence that this was the case. In part, the interpretation of these low platforms as benches rests on the fact that matching ones have been found within the palatial acropolis of the site, rather than in the sanctuary of evident ritual structures, such as temples. This dichotomy is furthered by the fact that what can be called benches, have been found constructed in the corners of rooms, whereas altars would tend to be erected in central positions in-line with the primary axis of a temple structure. In this regard, it is important to remark that as many as seven such stuccoed benches have been found within the acropolis, of which two exhibited traces of red and/or blue pigmentation (Structures Ac4 and Ac6), one was built with faces in talud-tablero (Structure Ac6), and an additional two exhibit horizontal medial outsets that can be broadly characterized as atadura mouldings (Structure Ac8). What helps to integrate these benches into a common category of architectural features are their physical characteristics (Table 1).

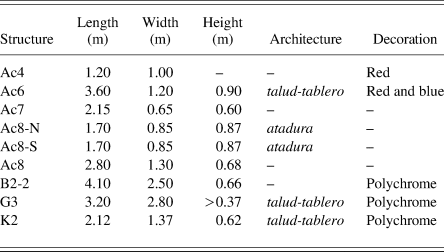

Table 1. The physical characteristics of the masonry benches discovered at Xochicalco.

While otherwise rare in the architecture of central Mexico, very similar benches are quite commonly encountered in the Maya area (Harrison Reference Harrison1970, Reference Harrison, Inomata and Houston2001; Noble Reference Noble1999), at El Tajín in Veracruz (Brüggeman et al. Reference Brüggeman, de Guevara, Bonilla and Doniz1992), and, in terms of size and execution, they bear strong similarities to the three examples from Xochicalco (for comparison see Harrison [Reference Harrison1970:152–175]). In the Maya area the surfaces of such benches have been interpreted as elevated multipurpose activity areas, whose functions include domestic, craft production and scribal activities (Inomata Reference Inomata2001), sleeping areas (Harrison Reference Harrison1970:175–183, Reference Harrison, Inomata and Houston2001), and as seats or thrones (Hammond Reference Hammond1999; Harrison Reference Harrison, Inomata and Houston2001; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Triadan, Ponciano, Terry and Beaubien2001:298, 301–302). Noble (Reference Noble1999:64) notes that 75 percent of seats depicted in Maya iconography are formed of masonry, and that: “These are at times located in exterior positions associated with particular buildings, but much more frequently are found in interior rooms were they are almost inevitably attached to at least one wall.” As we shall see, examples of both types of locations are found at Xochicalco. We examine three individual benches in the alphanumeric order of the structure designations with which the benches are associated.

THE BENCH OF STRUCTURE B2-2

The first painted bench to be discussed was found within Structure B2-2 (Figure 2a), also referred to as the Salón del Altar Policromado, which is situated on the terrace at the northern end of the acropolis, just below the level of the Plaza Principal and as such very close to the well-preserved sweatbath (or temazcal) and the water drainage system of the terrace (Garza Tarazona and González Crespo Reference Garza Tarazona, Crespo and Wimer1995:122–124). Access to the building is gained through three entrances on the east side, and the interior dimensions of the room are such that it was necessary to place eight pillars in two rows all along the length room to support the thick, terrado roof. The so-called “Altar Policromado,” which we here to refer to as a bench, was built against the east and south walls, occupying the corresponding southeastern corner of the building. The bench is constructed in the local talud-tablero style of architecture, and made from cut stone and mortar and measures 4.10 × 2.50 m, reaching a height of 66 cm. On its western side is a small stair of three steps, presumably serving as a means of access to the surface of the bench. Structure B2-2 appears to have been subject to modifications over time and the bench may well have been erected relatively late in the history of Xochicalco (ca. a.d. 1000), a situation that also applies to the two other benches to be discussed.

Figure 2. The B2-2 Bench. (a) The bench in situ in the southeastern corner of the building. Note the talud-tablero and the small stair on the west side of the bench. (b) Detail of the west side of the bench, showing the chaalchiwitl circlets and the vertical undulating lines on the talud. The red lines are much faded but can still be discerned. Photographs by Ricardo Alvarado, courtesy of the Archivo del proyecto La Pintura Mural Prehispánica en México, Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Reproduction authorized by the Insituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

The Iconography of the B2-2 Bench

The upper tablero is painted with a dark blue frame filled in with white rings or chaalchiw (“chalchihuites”) on a lighter blue background (Figure 2b). The chaalchiwitl circlets have long been regarded as symbolizing water in several Mesoamerican cultures from Teotihuacan and onwards (Angulo V. Reference Angulo V. and de la Fuente1995:77; Langley Reference Langley1986:282), and we follow this general line of interpretation here. The white background of the talud is painted with alternating, undulating dark-blue and red lines running vertically, seemingly alluding to liquids such as water and blood. With the chaalchiwitl circlets and streams of water, the bench is reminiscent of other seats or thrones associated with water and rain. The earliest example of this is the “cloud throne” of Monument 1 (“El Rey”) at Chalcatzingo in Morelos. The Olmec symbol for clouds (the so-called “Lazy-S”) marks not only the seat, but also the bar-like object held by the individual who is seated in the mouth of a personified cave (Angulo V. Reference Angulo V. and Grove1987:135–139). Significantly, this “Lazy-S” symbol is substituted for more naturalistic clouds elsewhere at Chalcatzingo (Taube Reference Taube and Guthrie1995:101, Figure 24c), leaving little doubt that this is a reference to clouds. From the mouth of the mountain-cave, large cloud scrolls emanate and above the scene are rain clouds, raindrops, and concentric circles. The whole imagery clearly associates the mountain-cave as the source of rain clouds, and it is worth noting that “El Rey” faces the volcano Popocatepetl, a mountain still widely believed to be responsible for rain among the Nawa of the surrounding areas (Glockner Reference Glockner2009). As is clear from several of the carvings and reliefs along the path leading up to the El Rey, sacrifice and the shedding of blood was apparently a prerequisite for the coming of the rains (e.g., Monuments 2, 4, and 5), and the exchange of “blood for water” may be what is also hinted at by the streams of blue and red liquid on the B2-2 Bench.

In the much later Mixtec Codex Vaticanus 3773, we find another telling juxtaposition of the blue and red streams of liquid. On page 44, a yellow Tlaalok figure is surrounded by water streams on his one side, while blood is gushing from a sun disk on his other side (Figure 3a). Whereas water is frequently marked by aquatic beings in the same codex (as in nearly all Mesoamerican iconographic traditions), the blood stream is marked with references to war and sacrifice: a dart, shield, human heart, and a skull and crossbones. It is thus tempting to view the alternating blue and red lines of the Xochicalco bench as alluding to this fundamental exchange between supernatural entities (responsible for rain) and humans (responsible for the appropriate offerings, in this case blood). In the same vein, Solís (Reference Solís and la Fuente1999:136) suggested that the bench of Structure B2-2 “shows designs that are probably related to the worship of aquatic gods,” although he did not mention the streams of red liquid. Thus, the imagery may play on the life-giving qualities of both liquids, and referring to the obligations of the Xochicalco elite to sacrifice blood, including their own, in order to secure the exchange with the supernatural world, and in this case, presumably the rain entities.

Figure 3. (a) Detail of the Codex Vaticanus 3773, p. 44 (Anders Reference Ferdinand (editor)1972), showing the rain deity Tlaalok amidst streams of blue and red liquid, undoubtedly references to water and blood. (b) The famous scene of the Historia tolteca-chichimeca (Kirchhoff et al. Reference Kirchhoff, Güemes and García1976:f. 16v) depicting a pool of water and blood associated with the Place of Reeds possibly serving as a reference to a “Lagoon of Primordial Blood” (after Leibsohn Reference Leibsohn2009:124, Plate 6).

An alternative interpretation of the relatively rare combination of blue and red liquid can also be put forth. An interesting reference to blue and red waters is found in a version of the Mexica foundation myth recorded by Durán. Here it is narrated that the Mexica migrants at one point come across two streams emerging from a cave: “one red like blood, the other so blue and thick that it filled them with awe” (Durán Reference Durán, Heyden and Horcasitas1964:ch. V, p. 31; see also Heyden Reference Heyden, Carrasco, Jones and Sessions2000:176–182). Soon after this event, the migrants saw an eagle seated on a nopal cactus and they had reached their final destination. Thus, the two liquids also seem to be closely related to places associated with origins, and in the sixteenth-century Nawa manuscript known as Historia tolteca-chichimeca, the scene of folio 16v shows a ballcourt and an U-shaped rectangular enclosure, from which blossoms, grasses, and reeds sprout and which also contains “both blue liquid, referring to water, and red liquid alluding to blood” (Leibsohn Reference Leibsohn2009:123; see also Figure 3b; Kirchhoff et al. Reference Kirchhoff, Güemes and García1976).

Oudijk (Reference Oudijk and Blomster2008, Reference Oudijk, Boone and Urton2011) has noted that the combination of pools of water and blood in the Historia tolteca-chichimeca recurs elsewhere in the Colonial sources in both central Mexico and Oaxaca. Thus, he shows that Oaxacan sources refer to a “Lagoon of Primordial Blood” (Quilatinizoo), and that this was a place of origin paired not only with the Nine Caves and Seven Caves, both places of origins, but also with Toollaan, “The Place of Reeds” (Oudijk Reference Oudijk and Blomster2008:107–110). Also, an early seventeenth-century land title from the Zapotec town of San Juan Comaltepec claimed that its founder came from the “Hill in the Middle of the Water, Lagoon of Blood, and Place of Reed” (guiag lachui niza, guelarenee, zaguita; Oudijk Reference Oudijk, Boone and Urton2011:158), making it highly probable that the “Lagoon of Primordial Blood” is a “conceptual place like Chicomoztoc or Tollan and that it is related to such a place of origin” (Oudijk Reference Oudijk and Blomster2008:110). The association between a ruling family or lineage and the cave and lagoon complex is visually represented in the Genealogy of Quiaviní (Oudijk Reference Oudijk and Blomster2008:Figure 3.2), and the combination of reeds and scrolls of water and blood is also shown in the Relación geográfica de Cholula, the latter being specifically cited as Tollan Cholula (Boone Reference Boone, Carrasco, Jones and Sessions2000:378–380). Oudijk's (Reference Oudijk and Blomster2008:111) interpretation of the already mentioned folio from Historia tolteca-chichimeca is as follows: “The central scene is Tollan, or Place of Reeds, plants growing in a lagoon of which the water is divided into two parts. One side is blue and the other side is red—again, an association of Tollan with water and blood” (see also Leibsohn Reference Leibsohn2009:166).

Returning to our analysis of the iconography of the B2-2 Bench at Xochicalco, the concept of the “Lagoon of Primordial Blood” and its close association with Toollaan and a place of origin thus provides a possible frame of interpretation for the streams of blue and red liquid. If the bench in fact served as a seat of authority, the association with concepts of origins, founders, and the Place of Reeds would all be of great relevance for the ruling members at Xochicalco. Thus, it would not be surprising if the elite of Xochicalco strove to establish Xochicalco as a new “Place of Reeds” after the fall of Teotihuacan, the first and original Toollaan (Boone Reference Boone, Carrasco, Jones and Sessions2000; Stuart Reference Stuart, Carrasco, Jones and Sessions2000:501–506). In light of the emphasis on primordial times and places of origins, it is also worth noting that Structure B2-2 is situated near the series of artificial caves excavated under the northern part of the acropolis, among them the famous Observatorio Cave. The main purpose of most of these caves appears to have been the extraction of stone for construction, but we would still point to the fact that caves at many other Mesoamerican sites, both natural and artificial, are known to have been emulating and recreating the sacred caves mentioned in the creation and migration narratives (Aguilar et al. Reference Aguilar, Jaen, Tucker, Brady, Brady and Prufer2005; Brady Reference Brady1991, Reference Brady, Breton, Becquelin and Ruz2003). We thus cannot completely exclude the possibility that the caves had a secondary and more symbolic function. The nearby temazcal and the northern ballcourt further suggest that this was a restricted and private area of the site where rituals centered on the origins and ancestry of the Xochicalco elite, and the B2-2 Bench may have played a central role in these events.

THE BENCH OF STRUCTURE G3

The structure in front of which the bench or platform known as Altar de las Olas was originally discovered is Structure G3, and it was encountered during the excavations led by Ledesma Gallegos (Reference Ledesma Gallegos1994:27) of the Proyecto Especial Xochicalco in 1993–1994. Located at the southern end of the Plaza Principal, Structure G3 has a rectangular plan measuring 33.40 × 13.50 m and has five entrances to the south and one to the north. As with so many structures in Xochicalco, G3 underwent considerable changes over time, with major transformations apparently taking place around a.d. 1000–1100 (Alvarado León and Garza Tarazona Reference Alvarado León and Tarazona2010; González Crespo et al. Reference González Crespo, Garza Tarazona, Palvacini and Alvarado Léon2008). Originally G3 was a symmetrical building with five openings to the north and south, yielding four piers in each of its façades. Later, the five entrances to the plaza on the north side were reduced to one by blocking the lateral doorways, thereby leaving only the central opening untouched, whereas the five entrances on the southern façade were retained. The bench discussed in detail here was found in alignment to the northern entrance, but it remains unclear if the constructions of the bench dates to the time before or after the four entrances were sealed off.

The bench is a rectangular, adobe, talud-tablero construction measuring 3.20 × 2.80 m, reaching a height of 37 cm, but since the upper portion was destroyed during the collapse of the adjoining structure, the bench must originally have been somewhat higher (Figure 4a; González Crespo et al. Reference González Crespo, Garza, Alvarado, Melgar, Palavicini, de Ángeles, Sánchez and Albaitero1993–1994:179). The bench is stuccoed and painted on its northern and eastern side, but is assumed to originally have been embellished on all four sides (González Crespo et al. Reference González Crespo, Garza, Alvarado, Melgar, Palavicini, de Ángeles, Sánchez and Albaitero1993–1994:179). After excavation and reinforcement, the bench was removed to a less exposed and more secure location, and subsequent to curation has been placed on permanent display at the site museum, where it can be viewed today.

Figure 4. The G3 Bench. (a) Photo of the frontal talud of the G3 Bench, showing the well-rendered bands of waves. (b) Lateral view of the bench, showing the waves on the talud and what may be a mat-design painted along the tablero Photographs by Ricardo Alvarado, courtesy of the Archivo del proyecto La Pintura Mural Prehispánica en México, Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Reproduction authorized by the Insituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

The Iconography of the G3 Bench

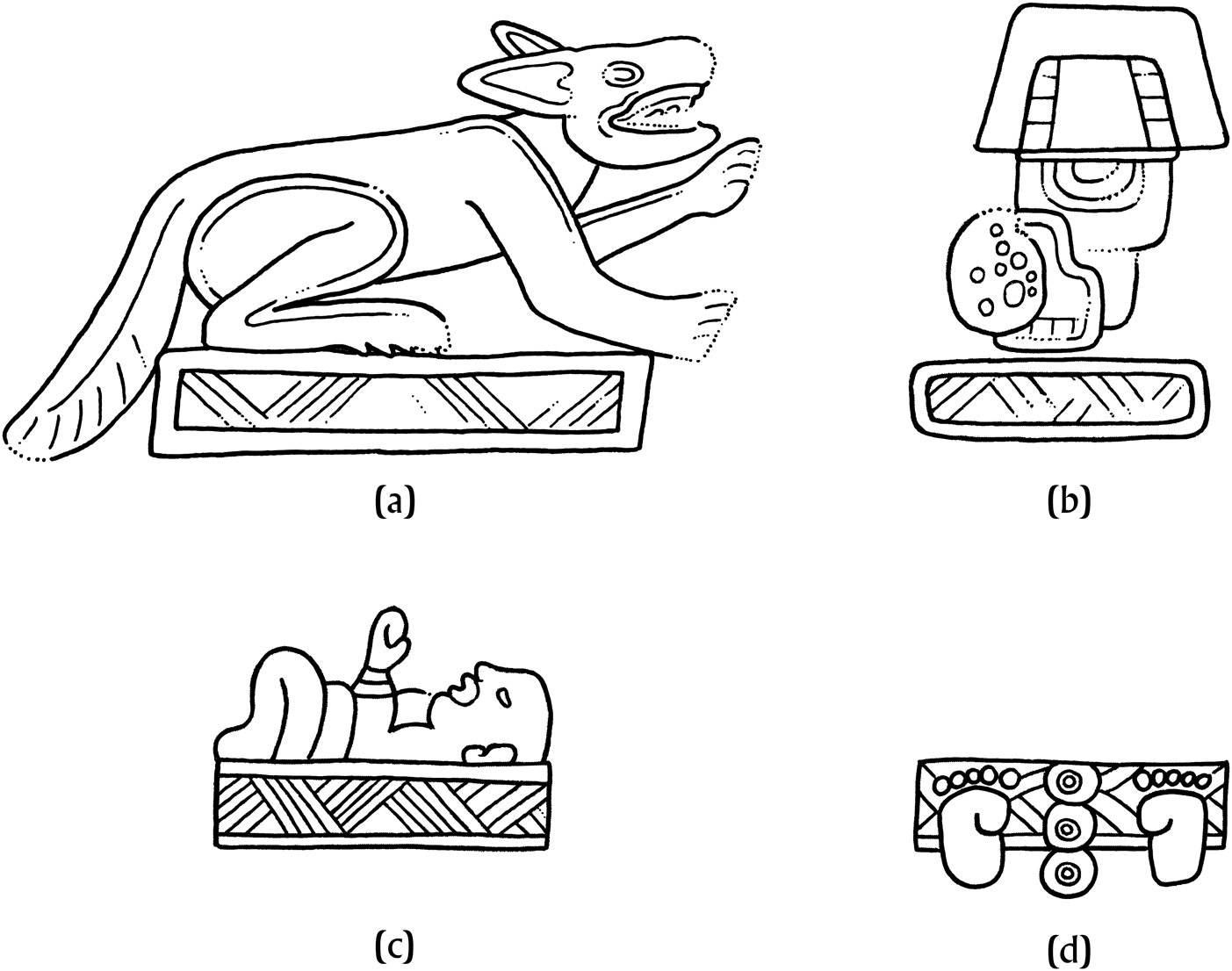

The bench is constituted by a lower talud surmounted by the upper tablero, and both parts where originally stuccoed and painted. Very little of the badly damaged decoration of the upper tablero survives, but enough is preserved to suggest that a possible mat design embellished at least part of the tablero (Figure 4b). Two bands, one painted red and blue, the other green, intertwine in a manner that may be comparable to the mat motifs carved on two reliefs (BW1 and BW4) of the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent (Smith Reference Smith and Hirth2000:58, 66, Figures 4.1 and 4.3) and on Xochicalco Stelae 1 and 3 (Figure 5; Smith Reference Smith and Hirth2000:23–25, Figures 3.3 and 3.5). The combination of a bench and a mat design suggests that the bench could have had a throne-like function, as indicated by the Nawatl difrasismo “petlapan ikpalpan,” which includes petlatl, “mat,” and ikpalli, “seat, throne,” which can best translated as “mat and throne,” a metaphorical expression for “rulership, governance” (Boot Reference Boot2000; Taube Reference Taube2000:19, 36, 51, n10, Reference Taube and Braswell2003:293–295). The woven mat thrones of local rulers are commonly depicted in the Late Postclassic and Early Colonial sources of the central Mexican and Oaxacan cultures, but the importance of the mat as a symbol of rulership or high office can be traced back at least to Early Classic Teotihuacan (Nielsen and Helmke Reference Nielsen and Helmke2014:125–130; Sugiyama Reference Sugiyama, Carrasco, Jones and Sessions2000:121, Figure 3.8; Taube Reference Taube2002), is also found in the Maya area (Boot Reference Boot2000), and may find its origins in Middle Preclassic Olmec culture (Rodríguez Martínez et al. Reference Rodríguez Martínez, Ceballo, Coe, Diehl and Houston2006). These observations suggest that the mat design is indeed a pan-Mesoamerican convention for referring to the highest seat of political power and authority.

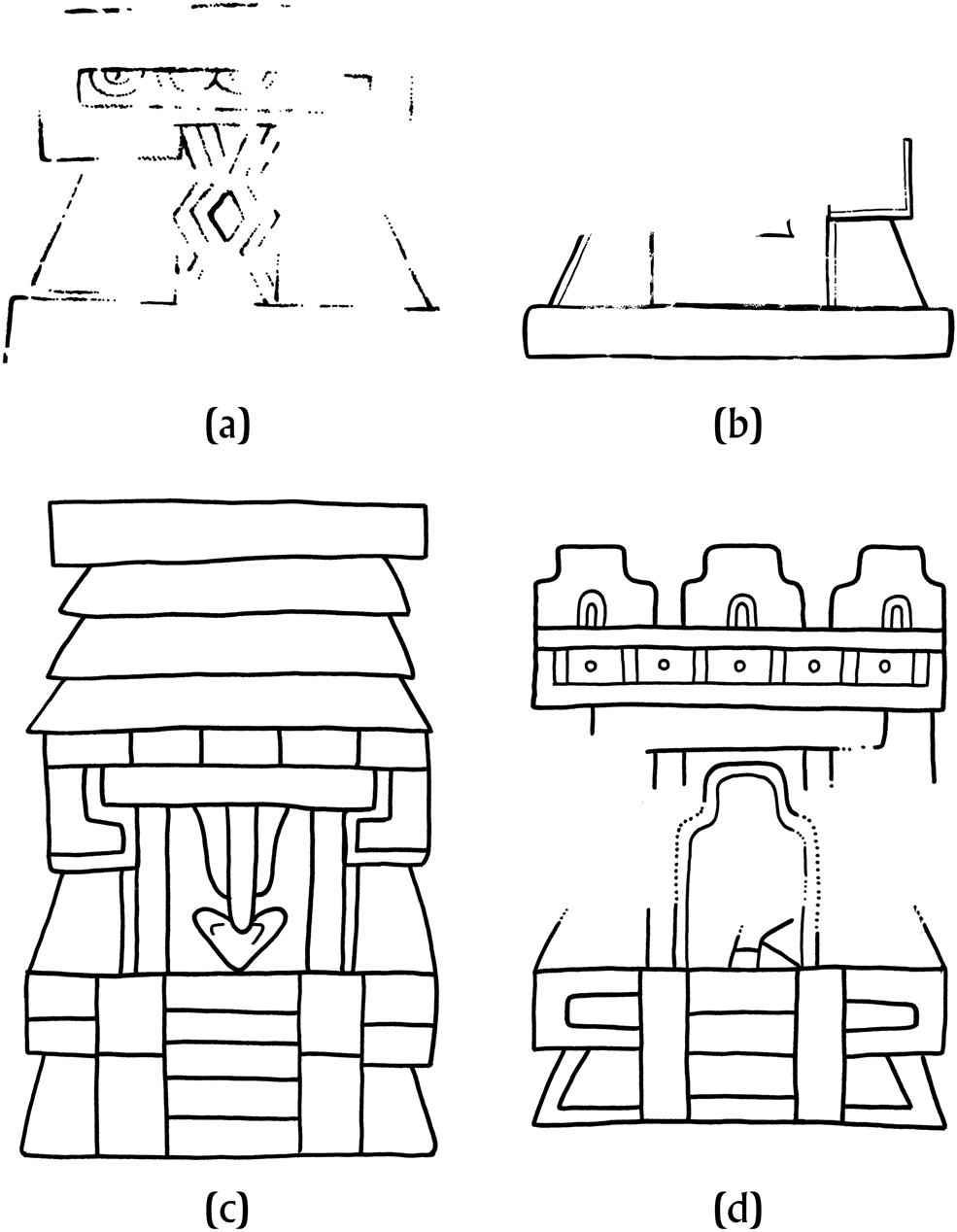

Figure 5. Representations of woven reed mats on carved reliefs at Xochicalco. (a) BW1. (b) BW4 from the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent. (c) Stela 1 (D14). (d) Stela 3 (C11). Drawings by Nielsen.

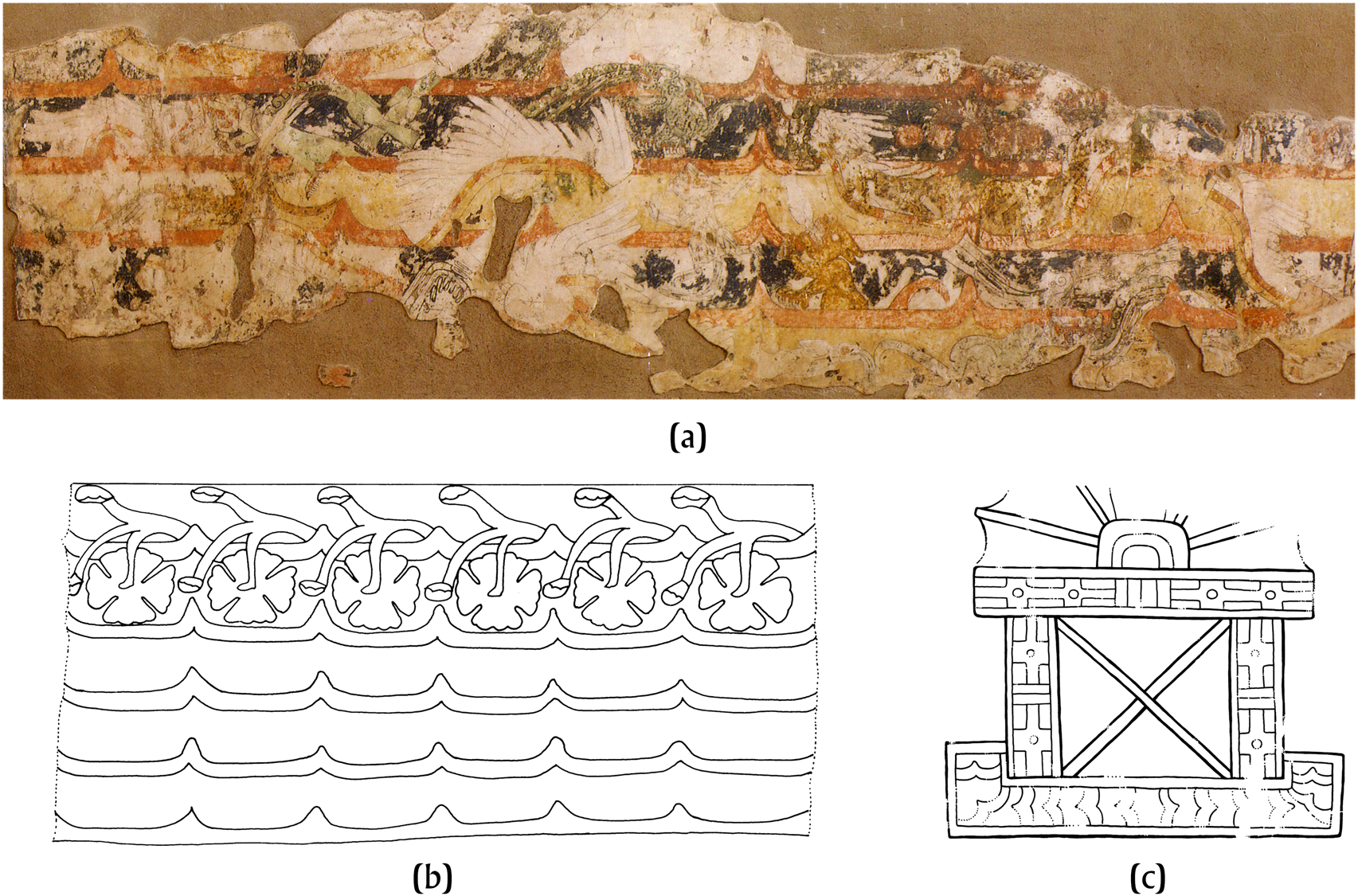

On the talud, a total of eight bands of waves painted in alternating light and dark blue, with one exception as the fourth wave, that besides being slightly broader than the others, is painted with a light-greenish color. The outlines of the waves are painted with red (Figure 4a). Similar waves can be found as early as the Middle Preclassic (Taube Reference Taube and Guthrie1995:87, Figures 5a–5c), but the waves of the G3 Bench find their nearest counterparts in the Teotihuacan murals known as the Mythological Animals (Figure 6a; de la Fuente Reference de la Fuente and la Fuente1995a:Laminas 1–4) and those from the Temple of Agriculture (Figure 6b; de la Fuente Reference de la Fuente and la Fuente1995b:Laminas 2 and 3), and at Epiclassic Cacaxtla in Glyph A of the hieroglyphic stair of the Red Temple (Figure 6c; Helmke and Nielsen Reference Helmke and Nielsen2011:Figure 19).

Figure 6. (a) Waves as the setting of the mural of the Mythological Animals (Teotihuacan). After de la Fuente (Reference de la Fuente and la Fuente1995a:95, Lámina 1). (b) Reconstruction drawing of a section of the mural from the Temple of Agriculture (Teotihuacan) with numerous bands of waves below a row of stylized water lilies. After de la Fuente (Reference de la Fuente and la Fuente1995b:104, Figure 10.2). (c) Glyph A from the hieroglyphic stair of the Red Temple (Cacaxtla), showing wave-designs in the lower part. Drawing by Helmke.

Whereas the mat design of the tablero readily brings to mind the mat thrones of Late Postclassic rulers, the water imagery does not, at first sight, have the same immediate association with rulership and political power. We have already seen, however, that the B2-2 Bench also displayed aquatic elements, and Kaplan (Reference Kaplan1995:186) has shown how stone thrones from the southern Preclassic Maya area carry representations of water, as for example the so-called Trono Incienso from Guatemala that has wave-shaped carvings on its sides. Furthermore, Reents-Budet (Reference Reents-Budet, Inomata and Houston2001:219–220) has noted that ceramic vessels from the Tikal-Uaxactun area and the Mirador region, depicting palace scenes have several occurrences of what she calls “water thrones.” These are all elite seats or benches marked with “liquid” or “water” signs. The examples illustrated by Reents-Budet show the use of dots and concentric circles to denote streams of water, and are not unlike the chaalchiwitl circlets that we saw earlier on the tablero of the B2-2 Bench (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Examples of Classic Maya “water thrones” on painted vessels. After Reents-Budet (Reference Reents-Budet, Inomata and Houston2001:Figures 7.11a, 7.11c, 7.11e). (a) Detail from K4550. (b) Detail from K7998 (Tikal Burial 116). (c) Detail from K2794. From Kerr Reference Kerr2010.

In her paper, Reents-Budet does not venture further into the significance and meaning of such water thrones, but here we would like to put forward some initial ideas regarding the apparent relationship between seats of authority and water. Thus, we may note that since the Preclassic there has been a persistent belief that clouds and rains were brought inland by winged and/or feathered serpent creatures, and such ideas are widespread in Mesoamerica and beyond (Helmke and Nielsen Reference Nielsen, Helmke and Sachse2014:26–28; Monaghan Reference Monaghan1995:105–108; Taube Reference Taube and Guthrie1995; Schaafsma and Taube Reference Schaafsma, Taube, Quilter and Miller2006). When we next consider the placement of the important individuals, possibly rulers, in the coils of the great feathered serpents marked by sea shells of the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent (Smith Reference Smith and Hirth2000), this suggests that the leaders of Xochicalco consciously invested a huge amount of effort in creating an image of themselves and their forebears as bringers of rain, sharing a close association with the feathered serpent. This also recalls the Feathered Serpent Pyramid at Teotihuacan, with its feathered serpents shown in an aquatic milieu, the depictions of feathered serpents with water streams emanating from their mouths found in the murals from Techinatitla (Berrin Reference Berrin1988), and the Epiclassic murals of the Red Temple and Structure A at Cacaxtla (Brittenham Reference Brittenham2015; Foncerrada de Molina Reference Foncerrada de Molina1993). As shown by Taube (Reference Taube2002) and others, the feathered serpent served as a symbol of political power, and the office of rulership was thus intricately linked with both life-giving waters and rain-bringing supernatural entities.

We thus suggest that the iconography and sculptures of the ceremonial precinct of Xochicalco, with its emphasis on feathered serpents and water imagery (also evident in the architectural elements in the shape of starfish, seashell, and fish), sought to underscore this area's close relationship to water and fertility, signaling that this was in a sense the place where the rulers and ritual specialists of Xochicalco controlled and secured the rains. Thus, the location of the most important structures of Xochicalco at the summit of a mountain not only reflects the armed and violent conflicts endemic of the Epiclassic and the concomitant wish to settle at easily defensible sites, but also that this was essentially a place where rain and abundance were secured since the iconography of the same structures so strongly emphasize these topics and themes. In a sense, Xochicalco's Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent materialized in architecture the same idea that we saw expressed at Chalcatzingo's “El Rey” and which can still be encountered so many places in Mesoamerica to this day, namely that contact with rain-bringing deities is best made at the summits of hills and mountains (Broda and Robles Reference Broda, Robles, Broda and Eshelman2004; Gómez Martínez Reference Gómez Martínez, Broda and Eshelman2004a, Reference Gómez Martínez, Broda and Eshelman2004b; Glockner Reference Glockner2009). The combination of the mat design and the lush, blue waves of the G3 Bench bring together the concepts of good rulership, fertility, and abundance.

THE BENCH OF STRUCTURE K2

The modest building known as Structure K2 abuts the northern end of the East Ballcourt, and was excavated by Mario Córdova during the Proyecto Especial Xochicalco (1993–1994), directed by González Crespo. Structure K2 is situated on a low platform (1.10 m high), and consists of a group of rooms arranged around an open patio. As with so many other structures at Xochicalco, K2 underwent architectural modifications resulting in the subdivision of rooms and blocking of passages. Apparently, the original plan was that of a central patio surrounded by three rooms to the east, north, and west. At a later period, the large northern room was divided into five separate rooms by a longitudinal wall running east-west, thereby creating Room 3, essentially a long corridor leading into Room 4. The east-west wall has three openings to the north, each of which provides access to Rooms 5–7. Through Room 5 there is further access to Room 8 that originally connected to another area to the north. The stuccoed and painted bench was discovered in a corner of Room 5, built against the west and north walls of the room (Figure 8). The bench is a rectangular talud-tablero construction (built of small rocks and mud coated in stucco) measuring 2.12 × 1.37 m and with a maximum height of 62 cm. On the south side of the bench is a well-made niche and, although there is no report that anything was found within the bench, it seems likely that it was used to store specific objects (Eberl Reference Eberl2000; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Triadan, Ponciano, Terry and Beaubien2001:292). Whereas the chronology of Structure K2 remains to be accurately defined, it appears to have been built around the same time as the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent, that is, sometime around a.d. 700–900. It was only later, between a.d. 1000–1100, that Structure K2 was modified and the bench was constructed (for a more recent discussion of the chronology of Xochicalco, see González Crespo et al. Reference González Crespo, Garza Tarazona, Palvacini and Alvarado Léon2008).

Figure 8. The K2 Bench in its setting in Structure K2. Photograph by Ricardo Alvarado, courtesy of the Archivo del proyecto La Pintura Mural Prehispánica en México, Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Reproduction authorized by the Insituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

The Iconography and Hieroglyphic Text of the K2 Bench

The exterior of the bench was coated with a layer of plaster and the eastern side of the tablero was embellished with a finely painted iconographic program rendered in various colors, accompanied by glyphic signs, the whole framed by a bright blue border (Figure 9; Garza Tarazona Reference Garza Tarazona2015b; Garza Tarazona and González Crespo Reference Garza Tarazona, Crespo and Wimer1995:120–121; Solís Reference Solís and la Fuente1999:135). Unfortunately, the paintings have faded considerably since their initial discovery, and it is difficult to identify with certainty the motifs represented as well as the entire composition. A number of interesting details can still be made out, however, and enough is preserved to allow us to make some preliminary observations. The imagery shares some notable compositional features with the iconography of the tablero reliefs of the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent, and is an example of a continuous iconographic tradition in both composition and content at Xochicalco.

Figure 9. The iconographic program and associated glyphic signs of the tablero of the K2 Bench. Drawing by Helmke and Nielsen.

A total of 14 individuals, all shown seated cross-legged and in profile, can be identified. What appears to be a diminutive and stylized representation of a talud-tablero structure, perhaps a temple, is shown in the middle of the composition, with nine individuals seated to the south, and five figures to the north, all facing towards the structure at the center. The central structure is reminiscent of the architectural style at Xochicalco and is almost identical to the building shown on Xochicalco Stela 3 and in Glyph E of the hieroglyphic stair of the Red Temple at Cacaxtla (Figure 10; Helmke and Nielsen Reference Helmke and Nielsen2011:34–35, Figure 19; Smith Reference Smith and Hirth2000:25, Figure 3.5). The lintel of the doorway is painted red and further marked by a row of semicircles. Within the entrance to the temple is a lozenge or rhomboid motif that also appears on the central part of the northern, eastern, and southern taluds of the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent (Garza Tarazona Reference Garza Tarazona2010a, Reference Garza Tarazona2010b; Smith Reference Smith and Hirth2000:Figure 4.2), thus possibly indicating that the structure represented is intended to refer to that particular temple, or at least to a comparable building.

Figure 10. (a) Detail from the K2 Bench showing the central structure. Comparative examples from (b) Glyph E of the hieroglyphic stair of the Red Temple, Cacaxtla. Drawings by Helmke. (c) Xochicalco Stela 1 (C12) and (d) Stela 3 (C12). Drawings by Nielsen.

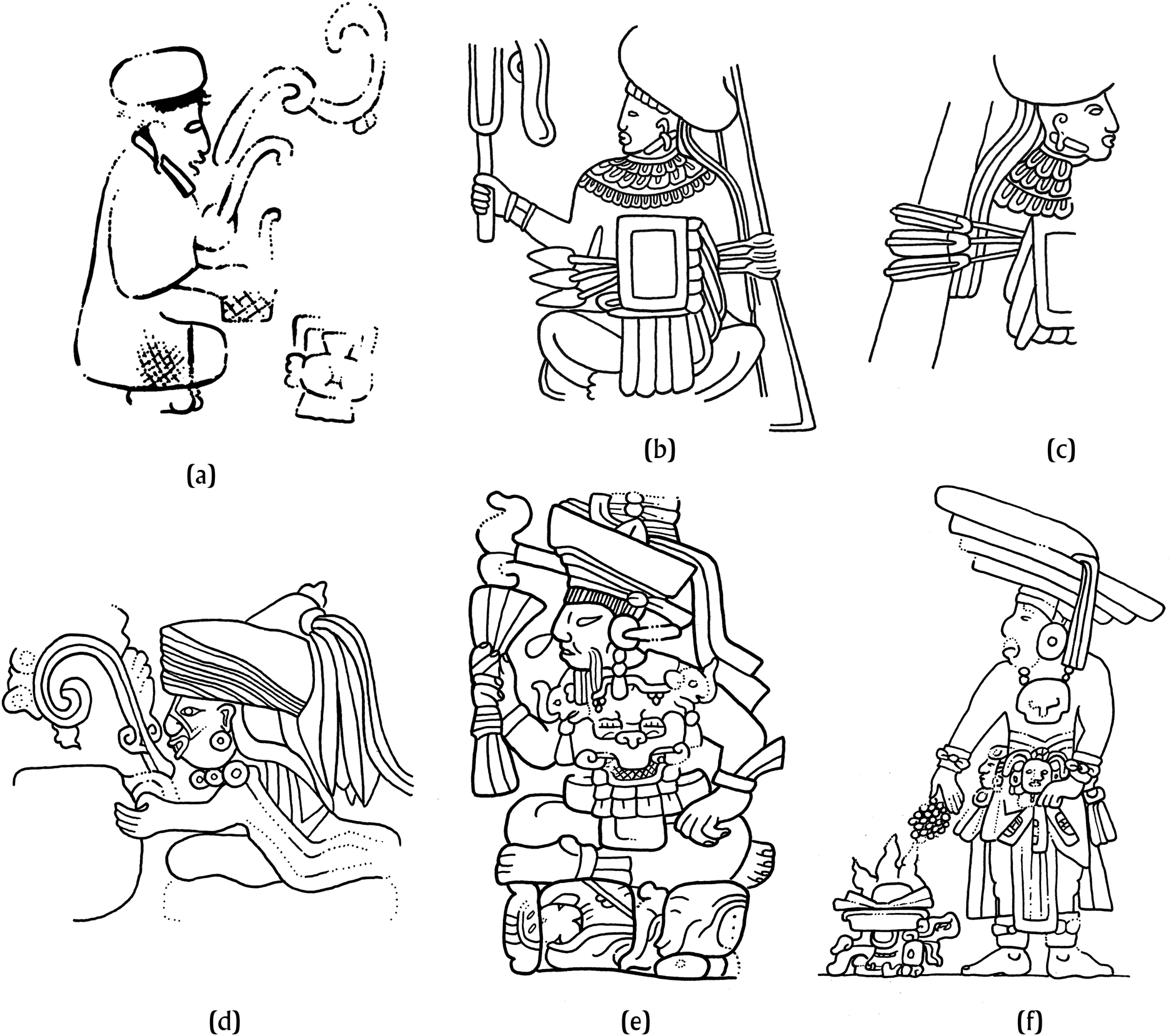

The 14 seated figures are here designated as 1S to 9S and 1N to 5N (wherein S and N refer to the southern and northern halves of the composition, i.e., to the viewer's left and right of the temple, respectively), with figures counted outwards from the center. Most of them appear to wear similar white clothing, consisting of a tunic-like shirt and a distinctive cape, some of which have finely woven or painted patterns and edges. Both Individuals S1 and S8 wear turban-like headdresses, but it is the well-preserved figure immediately to the south of the temple (1S) that exhibits the clearest example (Figure 11a). The turbans bear some resemblance to the headdresses worn by the warriors on the exterior façades of the summit building of the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent (Figure 11b and 11c), Smith Reference Smith and Hirth2000:73–75, Figure 4.7) but also call to mind a set of figures in the murals from Atetelco (ca. a.d. 500–600) at Teotihuacan. Thus, Murals 1 and 2 of Room 4, Patio 3 repeat a scene in which two individuals are seated facing each other (Figure 11d; Cabrera Castro Reference Cabrera Castro and de la Fuente1995:256, Laminas 61–69). Both wear large turbans embellished with feathers and capes with a woven or dyed design. From their mouths issue elaborate speech scrolls, and in front of them are large drinking vessels or jars, and the scenery is thus quite similar to that of the Structure K2 Bench at Xochicalco. Unfortunately, we know very little about the significance of the Teotihuacan drinking ceremony, if that is in fact what it represents, although comparable representations of pulque-drinking rituals are found at Cholula and in later Aztec sources (for an in-depth treatment of pulque-drinking scenes at Teotihuacan, see Nielsen and Helmke Reference Nielsen, Helmke, Cicero and Helmke2017a). Turbans are also represented in the corpus of ceramic figurines from Teotihuacan (see, for example, Séjourné Reference Séjourné1966:Figures 35, 38, 39), and a particular kind of coiled turban is known to have been worn by rulers of the Maya cities of Copan, Quirigua, and Nimlipunit (Figure 11e and 11f), and, although a detailed study of this specific type of headdress is still lacking, it would seem that it was associated with male individuals of high rank. Individual S4 seems to be wearing a broad Teotihuacan-style headdress marked by a large knot and the elderly, wrinkled figure N2 wears a distinctive kind of headband that is also worn by a priestly figure on the Palace Stone from Xochicalco (Caso Reference Caso1962; Helmke et al. Reference Helmke, Nielsen and Guzmán2017:98–102), as well as the prominent captives depicted on the tread of the hieroglyphic stair of the Red Temple at Cacaxtla (Figure 12; Helmke and Nielsen Reference Helmke and Nielsen2011:30–31, Figure 16). The fact that N2 is one of the only two individuals holding incense pouches may suggest that he holds a special rank, perhaps a ritual specialist of high status, and that the headdress is associated with this office at Xochicalco. This, in turn, could indicate that the captives from Cacaxtla were equally priests, and the tantalizing possibility exists that these individuals are in fact from Xochicalco (Helmke and Nielsen Reference Helmke and Nielsen2011:41; Nielsen and Helmke Reference Nielsen and Helmke2015). Several of the other individuals have long hair reaching down their back (3S, 6S, 7S, N1, and N5), and a single figure, S5, has a string of beads, serving as a counterweight to a heavy necklace, hanging down his back.

Figure 11. Classic-period depictions of individuals wearing turban-like headdresses. (a) Individual 1S, detail of the K2 Bench. Comparable headdresses worn by individuals on the carved reliefs of the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent (Xochicalco) (b) BS2 and (c) BN2. After Smith (Reference Smith and Hirth2000:Figure 4.7). (d) Room 4, Patio 3 at Atetelco (Teotihuacan), Mural 1, showing seated individual wearing decorated cape and turban. After Cabrera Castro (Reference Cabrera Castro and de la Fuente1995:246, Lámina 69). (e) Detail of Altar L (Copan), dated to a.d. 822, providing a posthumous depiction of the ruler Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat wearing a kind of turban. (f) Detail of Stela 15 (Nimlipunit), dated to a.d. 721, depicting a ruler in a ritual scattering act during a period-ending ceremony. Drawings by Nielsen.

Figure 12. (a) Detail of the K2 Bench showing Individual N2 wearing a distinctive headband. (b) Detail of one of the captives (Indivual 2) painted on the tread on the hieroglyphic stair of the Red Temple at Cacaxtla, wearing the same kind of headband. Drawings by Helmke.

About half of the figures (S1–S5, N3, and N4) are shown next to ollas with strap handles similar to those held by the seated individuals depicted four times on the eastern tablero (TE3-6) of the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent (Smith Reference Smith and Hirth2000:70–72; Figure 4.5). Smith (Reference Smith and Hirth2000:72–73) has interpreted these figures as warriors and representatives of specific places, offering jars on specific days of the ritual calendar. This interpretation is closely related to the hypothesis that the tableros show tribute-paying regions or individuals, which ultimately hinges on the hypothesis that the so-called “mouth and disk” collocation found on the majority of the tablero panels refer to “tribute” (Hirth Reference Hirth, Diehl and Berlo1989:72–75, Reference Hirth2000:255–257). In a later publication, Garza Tarazona and González Crespo (Reference Garza Tarazona and Crespo1998:25) described the same individuals as priests. More recently, we have presented evidence that this glyphic collocation probably refers to a priestly warrior title shared by all the depicted individuals (Helmke and Nielsen Reference Helmke and Nielsen2011:25–28; Taube Reference Taube2000:17–18). Here, we will confine ourselves to the observation that several of the figures depicted on the bench are shown with handled jars similar to those seen on the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent. It should also be noted that, while most of the jars are marked with small dots, possibly perforations, the jar of S1 appears to be marked with a sign that compares to the syllabogram po, sometimes used in Maya writing to cue the word pom, “copal” (Figures 13a–13f). At times the syllabogram is placed in incense burners (e.g., in the Dresden Codex, p. 25 [Anders Reference Ferdinand (editor)1975]; Figure 13d), and both individuals S3 and S4 appear to be scattering pellets of incense, or some other substance, towards the jars. Two individuals (1N and 2N) hold so-called incense pouches, which are also very similar to those seen on several of the tablero reliefs of the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent (Smith Reference Smith and Hirth2000:70, Figure 4.5), suggesting that these two figures were somehow of a different status or role than the others, or that they performed a task differing from that of their counterparts. The five first individuals to the south are also shown with what appears to be offerings in front of them, and these seem to have been stacked atop ceramic vessels or wooden containers, or boxes, with feet (or as in the case with S5 an everted bowl). While it is difficult to recognize the offerings associated with S1 and S2, the objects in front of S3 and S4 are strikingly similar to how screen-fold books are represented in Maya iconography (Figures 14a–14c). Furthermore, the row of individuals presenting offerings finds a close parallel in Teotihuacan mural art. Thus, the little-studied Murals 1–5 in Room 1 of Platform 14 (Zona 3) display a “procesión de sacerdotes” (de la Fuente Reference de la Fuente and la Fuente1995c:86–91, Figures 8.1–8.5). The six individuals are all clad in extraordinarily rich attire and are wearing kechkeemitl-style garments comparable to those seen on many of the figures on the K2 Bench. The figures are holding incense pouches in the one hand while with the other hand presenting different objects that, in two instances, resemble the flat, rectangular, box-like objects seen in the Xochicalco mural (Figure 14d). In one case, the object is further marked with what could be designated the “Opposing Scroll” sign (Langley [Reference Langley1986:302, n11] refers to the same sign as “Bar Hooked”) that is identical in all respects to the logogram ilwitl , “day, feast day,” used in Nawa writing, with the best examples stemming from a carved boulder from Coatlan, the Codex Telleriano-Remensis, and the Codex Mendoza, where it marks a stylized codex that is being painted by a scribe (Figure 15; Berdan and Anawalt Reference Berdan and Anawalt1997:145; Krickeberg Reference Krickeberg1969:Abbildung 59; Quiñones Keber Reference Quiñones Keber1995:63). This strongly suggests that the offerings or gifts presented in the Teotihuacan scene from Platform 14 included books, and based on this comparison with that of the Maya convention for depicting codices, we find it quite possible that Individuals S3 and S4 are indeed shown with screen-fold books. Finally, at least four of the individuals on the south side (S1, S3, S4, and S8) are holding some kind of curving object, possibly a cutting implement comparable to the obsidian knives of Teotihuacan (Sugiyama Reference Sugiyama2005:132–134, Figures 56 and 58; see also Latsanopoulos Reference Latsanopoulos and Giorgi2005) or a wooden scepter-like staff or baton akin to that discovered in the Feathered Serpent Pyramid at Teotihuacan (Sugiyama Reference Sugiyama2005:182–184, Figure 93a).

Figure 13. (a) Detail of the K2 Bench, showing Individuals S1–S4 and the associated vessels. Note the subtle differences between the ollas, which may have been used as incense burners. (b) The Maya syllabogram po. (c) Syllabic spelling [po]mo for pom, “copal,” in Maya writing. Incense burner with the syllabogram po amidst swirls of flames to indicate the burning of pom, “copal,” in the Dresden Codex on (d) p. 25 (e) p. 28 compared with (f) the jar in front of Individual S1 from the K2 Bench (see Anders Reference Ferdinand (editor)1975). Drawings by Helmke.

Figure 14. (a) Detail of the K2 Bench, showing Individuals S2, S3, and S4 and the objects in front of them. Examples of scribes with screen fold books in Classic Maya art. (b) K1196 and (c) K1523. Drawings by Helmke based on photographs by Justin Kerr (Kerr Reference Kerr2010). (d) Two individuals (3 and 6) from Murals 1–5, Room 1, Platform 14 Zona 3 (Teotihuacan) that carry what may be wooden boxes used for storing codices. After de la Fuente (Reference de la Fuente and la Fuente1995c:87, Figures 8.3 and 8.5). Note the Opposing Scroll sign on the object held by latter individual.

Figure 15. Examples of Nawa scribes in the act of writing codices marked with the Opposing Scroll or ilwitl logogram, designating these as almanacs or day counts. (a) Old male scribe, probably the deity Sipaktoonal, on a carved boulder at Coatlan, Morelos. After Houston and Taube (Reference Houston and Taube2000:Figure 11g). (b) Female scribe (“la pintora”), as represented in the Codex Telleriano-Remensis, folio 30r Drawing by Christophe Helmke after Quiñones Keber (Reference Quiñones Keber1995:63). (c) Male scribe in the Codex Mendoza, folio 70r. After Berdan and Anawalt (Reference Berdan and Anawalt1997:145).

Many, if not all, of the figures appear to have had elaborate speech scrolls emanating from their mouths. The scrolls are adorned with the kind of small beads that are distinctive of speech scrolls at Teotihuacan and Xochicalco, and are nearly identical to those associated with the previously mentioned seated individuals of the tablero reliefs of the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent. Some of the scrolls, however, are further marked with small affixed objects or signs, as in the case of 2S, whose speech scroll is further affixed with a small cross-hatched element and what may be “flint” or “obsidian” blades or “flames,” as it is known from the Mixtec Codex Selden 7 and the Guatemalan site of Cotzumalhuapa, where this type of marked speech has been argued to signify either “cutting words or insults” (Houston and Taube Reference Houston and Taube2000:278–279; Marcus Reference Marcus1992:379–380, Figure 11.23; Taube Reference Taube2000:31–33) or “fiery speech” (Chinchilla Mazariegos Reference Chinchilla Mazariegos, Boone and Urton2011:61–62). Another possibility is that the elements attached to the speech scroll of individual 2S are in fact flowers, thus qualifying the utterance as “flowery speech,” which would perhaps better fit the context and be more in-line with the common occurrence of flowery speech scrolls at Xochicalco's predecessor, Teotihuacan (Angulo V. Reference Angulo V. and de la Fuente1995:160, Figure 4.28; Houston and Taube Reference Houston and Taube2000:276–278; Nielsen Reference Nielsen, Helmke and Sachse2014). The speech scroll of N1 has what may be either a small almena sign attached (Nielsen and Helmke Reference Nielsen and Helmke2014:118–125), perhaps indicating that he is making an utterance about the building in front of him. Alternatively, it could be a simplified “year sign,” suggesting a plausible reference to rulership and power, since we now know that the “year sign” was used from Teotihuacan and onwards as a headdress element worn by high-ranking individuals as well as calendrical signs to mark them as year bearers (Nielsen and Helmke Reference Nielsen and Helmke2017b, Reference Nielsen and Helmke2019).

Despite the fact that the uppermost part of the mural was already faded at the time of its discovery, it can still be ascertained that glyphic signs originally accompanied at least 11, and in all likelihood all, of the seated individuals (Figure 16). Thus, the outlines of rounded cartouches can still be recognized above 1S, 2S, 3S, 5S, 8S, 9S, and 1N–4N, and the faint traces of two dots can furthermore be seen above and in front of figure 5N. Below the rounded cartouches of 1S, 3S, 1N, and 2N are the bars that are used to designate the numbers “5,” and at 2N and 5N are two dots for “2,” and together these confirm that the glyphs are calendrical notations. The placement of the numerals below the day signs are in accordance with other calendrical notations at Xochicalco, and also follows the pattern observable at Teotihuacan and central Mexican Epiclassic texts found at sites such as Cacaxtla, Teotenango, and Tula (Helmke et al. Reference Helmke, Nielsen, Leni and Campos2013; Helmke and Nielsen Reference Helmke and Nielsen2011:3–20). In all, three day signs can be identified on the bench. S1 is thus combined with the date “5 Glyph A” (Figure 16e; Caso Reference Caso1962:60–61), which Taube (Reference Taube, Boone and Urton2011:82–84) recently proposed is an early form of the “Water” day sign based on comparisons to contemporary monuments at sites in Guerrero and Oaxaca. A reevaluation, however, of the four calendrical glyphs on the so-called “Lápida de los Cuatro Glifos” from Xochicalco, suggests that Glyph A ought to correspond to the day sign “Flint,” as it appears together with the three other year bearers of Set III, namely “House,” “Rabbit,” and “Reed” (Helmke and Nielsen Reference Helmke and Nielsen2011:12–20, Reference Helmke and Nielsen2020). The hieroglyphs above S3 and N2 can be identified as a coiled serpent, and when combined with the numeral below, these can be read as “5 Serpent” and “7 Serpent,” respectively (Figures 16a and 16b). These renditions of the day sign “Serpent” are highly similar to other versions of the same day sign in the corpus of Epiclassic writing, most notably at Cacaxtla, where the individual depicted on the North Pier of Structure A is named “1 Serpent” (Figure 16d; Helmke and Nielsen Reference Helmke and Nielsen2011:44). A very similar “Serpent” day sign also occurs on the recently discovered stela from Cerro de la Tortuga on Oaxaca's Pacific Coast (Figure 16c; Rivera Guzmán Reference Rivera Guzmán and Iván2007; see also Urcid's [Reference Urcid2001:213–217] discussion of Glyph Y in Zapotec writing).

Figure 16. The preserved glyphic signs from the K2 Bench, with comparative examples from other Classic and Epiclassic sites. Drawings by Christophe Helmke. Examples of dates on the K2 Bench: (a) 5 “Serpent” and (b) 7 “Serpent.” (c) 9 “Serpent” from Monument 2, Cerro Tortuga, Tepenixtlahuaca, Oaxaca. After Rivera Guzmán (Reference Rivera Guzmán and Iván2007:Figure 3). (d) 1 “Serpent” (N-A2), Northern Pier, portico of Structure A, Cacaxtla. (e) 5 Glyph A, K2 Bench. (f) 7 Glyph A, Lápida L3, Xochicalco. Glyph A in Teotihuacan writing: (g) 10 Glyph A, section of a marcador and (h) 13 Glyph A, detail of fragmentary vessel. After Taube (Reference Taube, Boone and Urton2011:Figures 5.4b and 5.4c).

Having identified the surviving glyphs above the individuals as numbered day signs of the Mesoamerica. 260-day calendar, we must now consider the function and meaning of this row of glyphs. To these ends, we would like to call attention to an unprovenanced incised travertine vessel published by Kerr (Reference Kerr1989:11) as vessel K0319 (Figure 17). Although aspects of the style and execution of the incised lines are reminiscent of Maya iconography, the scene has definite non-Maya features, prompting Kerr (Reference Kerr2010:K0319) to note that it is “probably quite late and from the central Mexican area.” As such, it is a possible syncretic product of the contacts between the Maya area and central Mexico of the Epiclassic period. Of the 11 figures shown on the vessel, four persons are seated on scaffold seats or thrones (Boot Reference Boot2005:398, Figure 5.14) and one is a dwarf-like figure, which together strongly suggest that this is a palatial scene. Highly relevant in terms of understanding the K2 Bench are the calendrical signs that appear above the heads of nine of the individuals. The clearly non-Maya glyphs are all calendrical and each combines a day sign in a rounded cartouche with a numeral placed not below, as would perhaps be expected, but above it. From right to left the extant glyphs can be tentatively be identified as: “1 Foot,” “9 Iguana/Crocodile,” “3 Rabbit?,” “2 Gopher?,” “7 Dog,” “1 Water,” “2 ?,” “1 Foot,” and “6 Death?”. As the majority of calendrical constructions are not those of year bearers, and since there is no detectable pattern in these dates that would suggest that they refer to a calendrical sequence such as a series or count of years, we are left to conclude that they are personal calendrical names of the portrayed individuals. If we are correct in this, the scene would follow the conventional way in Mesoamerica of placing personal names close to the heads of the persons to which they refer (Helmke and Nielsen Reference Helmke and Nielsen2011:22; Houston et al. Reference Houston, Taube and Stuart2006:60–68). When we further note that at least five of the individuals wear turbans, the overall similarity between this scene and the text and imagery of the K2 Bench from Xochicalco becomes even clearer, and we thus suggest that the calendrical dates associated with the seated persons on the Xochicalco bench also record their personal names.

Figure 17. Unprovenanced travertine vessel (K0319) with calendrical signs conforming to those of Epiclassic writing and with individuals displaying non-Maya features. Photograph © Justin Kerr (Reference Kerr1989:11).

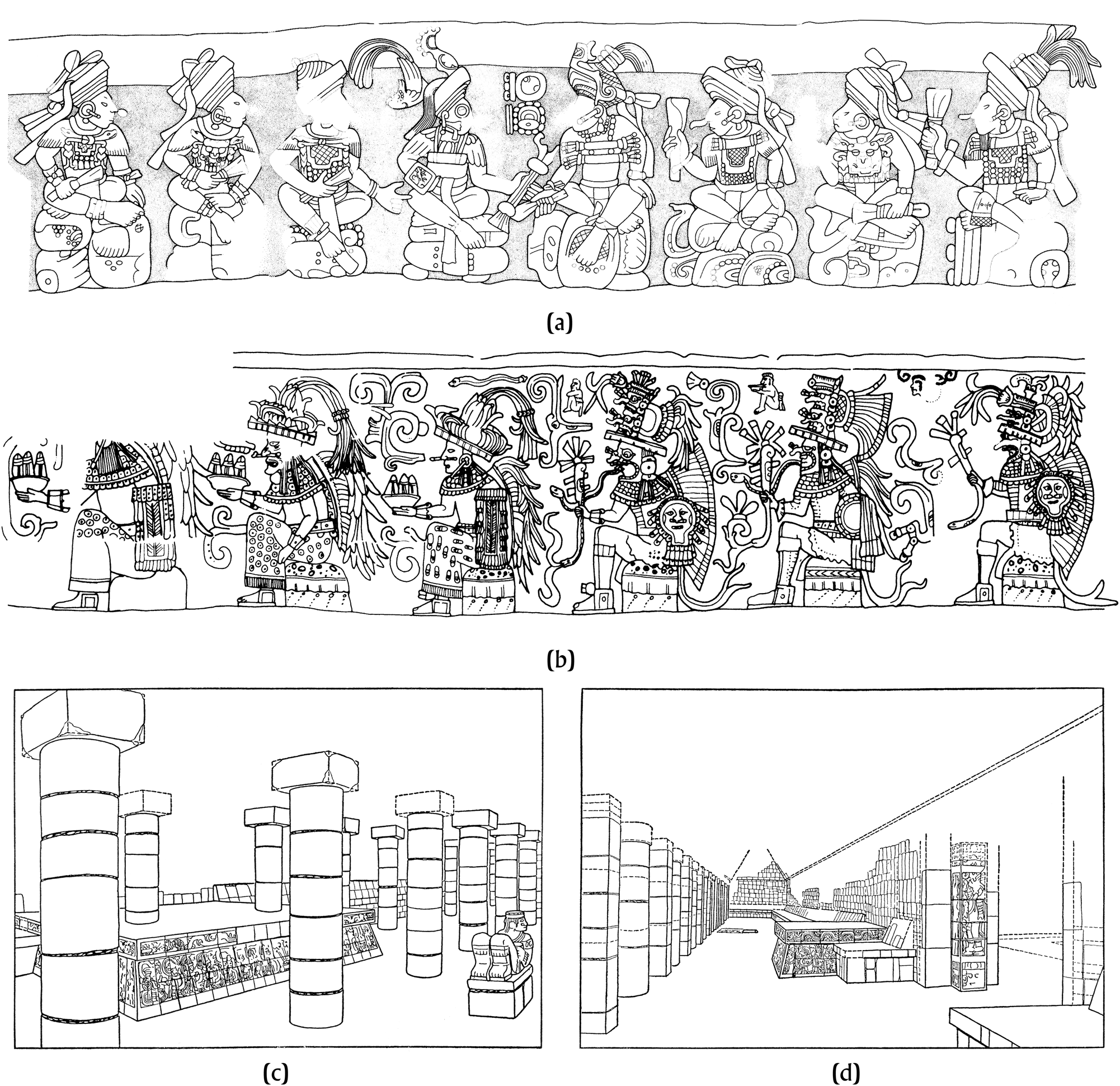

The representation of several named individuals at one time is most likely to depict a congregation of individuals either from one specific site or from different places. As such, the image and text of the K2 Bench may well represent a type of palatial scene on par with the travertine vase just examined. Alternatively, such a composition could also represent a genealogical or dynastic sequence with the inherent understanding that not all these individuals were alive at the same point in time. Scenes of this type are, as far as we can ascertain, rare at Teotihuacan. Thus, the row of named individuals from the murals of Techinantitla wearing Tasselled Headdresses and the five seated individuals shown on a Teotihuacan plano-relief vessel (Millon Reference Millon and Berrin1988; Taube Reference Taube and Braswell2003:284, Figure 11.6a), probably depict a sequence of individuals in the same office or a congregation of equally ranked members of Teotihuacan society participating in a singular historical event. For the Late and Terminal Classic Maya, we have, however, good evidence for an iconographic and compositional template in which several lords are centered on an event or a structure and where these represent a dynastic sequence. There are some notable exceptions to this pattern. Two beautifully decorated platforms were recently discovered in Temples XIX and XXI at Palenque (González Cruz and Bernal Romero Reference González Cruz and Romero2003; Stuart Reference Stuart2005), and the south face of the platform of Temple XIX shows the Palenque ruler K'inich Ahku'l Mo’ Naahb seated on his throne or platform surrounded by court attendants, three on each side, taking part in the accession ceremony in a.d. 722. Thus, the scene has the paramount ruler represented centrally, and with his named subordinates flanking him symmetrically. In the case of Copan, the famous Altar Q (but see also Altars T and L and the Sculptured Bench of Temple 11 [Baudez Reference Baudez1994]) dedicated by Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat in a.d. 776 to commemorate his accession, shows all 16 Copan rulers seated in sequence around the four sides of the square altar, each ruler being seated on his hieroglyphic name (Figure 18a; Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008:209–210; Stuart and Schele Reference Stuart and Schele1986). On the front of Altar Q, the sixteenth ruler, Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat, faces K'inich Yax K'uk’ Mo’, the founder of the Copan ruling lineage, who posthumously hands him a torch-like scepter. Interestingly, the Copan rulers all wear the distinctive turban-like headdress mentioned above.

Figure 18. Examples of rows of seated individuals and throne benches from the Maya area. (a) Eight of the 16 rulers depicted on Copan Altar Q. After Baudez (Reference Baudez1994:96, Figure 40). (b) The South Bench of the Temple of the Chac Mool at Chichen Itza showing six of the 14 figures carved on the side. Note the subtle differences in the individuals’ headdresses, garments, and the objects they hold. Drawing by Linda Schele © David Schele, courtesy of Ancient Americas at LACMA (http://ancientamericas.org). The so-called “altars” from the (c) North Colonnade and the (d) Mercado Gallery at Chichen Itza. After Proskouriakoff (Reference Proskouriakoff1963:100, 104).

From the Terminal Classic Maya city of Chichen Itza, which had its apogee between a.d. 800 and 1050, we encounter similar images depicting rows of individuals, and in some cases, these also seem to be named. Thus, Boot (Reference Boot2005:405, 411–412, 461, Figures 5.21a, 5.21b, 5.28) suggested that the depictions of nearly identical persons seated on jaguar thrones and cushions covered in jaguar pelt on the North and South Benches of the Temple of the Chac Mool, as well as the North Wall Mural in the North Building of the Great Ballcourt are not evidence of joint-rule government at Chichen Itza, as has long been assumed, but rather a sequence of paramount rulers akin to what we know from Copan (Figure 18b). With regard to the North Wall Mural, Boot (Reference Boot2005:412–413) noted that:

The middle row consists of two lines of human figures, each with a large feathered headdress and seated on cushions or pillows. These seated figures are turned toward a center scene, depicted directly above the empty jaguar throne…It has been suggested that this particular part of the scene “may be compared with the assembly of “the principal people and noblemen” (Durán Reference Durán1967:[vol. II, p.]249) which gathered in Tenochtitlan four days after the death of a ruler in order to elect a successor” (Wren Reference Wren and Fields1994:27) or “depicts the council lords of Chichén Itza flanking a central pair of figures” (Schele and Mathews Reference Schele and Matthews1998:252). The rows of seated human figures on either side of this central scene, however, are quite reminiscent of the composition of the Temple 11 sculptured bench panel and Altar Q at Copan.

These observations on the template for representing dynastic sequences coupled with references to accession rituals in Maya culture in the Late to Terminal Classic period, are pertinent, not only on account of broad contemporaneity with the bench of Structure K2 at Xochicalco, but also because nearly identical benches or thrones are known from Chichen Itza and Early Postclassic Tula and El Cerrito, Queretaro (Nielsen et al. Reference Nielsen, Helmke and Fenoglio2018). For example, in the North Colonnade as well as in the Mercado Gallery at Chichen Itza, a talud-tablero bench or seat was built against the wall (Figures 18c and 18d; Noble Reference Noble1999:224; Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1963:100–101, 104–105). A similar bench was discovered in Structure 4 (i.e., the “Palace to the East of the Vestibule”) at Tula, Hidalgo, and located between Pyramids B and C (Mastache et al. Reference Mastache, Cobean and Healan2002:111–114, Reference Mastache, Healan, Cobean, Fash and Luján2009:302–304). What is striking is not only the shape of the Tula bench, but also the sculptured friezes on the talud and tablero parts that are almost identical to the examples from Chichen Itza. Thus, the larger talud depicts processions of warriors, whereas the narrower tablero shows undulating feathered serpents (Mastache et al. Reference Mastache, Cobean and Healan2002:113, Figure 5.28). Mastache and her coauthors (Mastache et al. Reference Mastache, Cobean and Healan2002:113) note that, in the case at Tula, the warriors are walking towards a central figure that they suggest could be the king of Tula. At both Chichen Itza and Tula, the talud-tablero bench was integrated in a lower, long bench running along the wall, strongly suggesting that the individual seated on the larger bench was of some higher rank, possibly even the rulers of the sites (Báez Urincho Reference Báez Urincho2007).

These examples suggest that in more-or-less symmetrical compositions with several individuals, seated or standing, the more important ones are placed centrally, often being the focus of a specific object or event. It follows that the individuals of central importance on the K2 Bench are seated on either side of the diminutive temple structure, and perhaps with N1 and N2, being the only ones holding incense pouches, as the two most central figures on the entire bench. Furthermore, the total of 14 individuals centered on the temple can be compared to the sequence of 28 seated persons of the tableros of Xochicalco's Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent that envelop the building, and thus in a similar fashion face onto and are centered on the front of the building and the central stair leading to the summit of the temple. In sum, whereas a comparison with related iconography may support the interpretation of the named individuals on the K2 Bench as a dynastic sequence, possibly centered on the accession of a late Xochicalco ruler, we believe that the many subtle but clear differences among the portrayed individuals, in terms of clothing, headdresses as well as the kinds of offerings or gifts they present, strongly suggest that we are faced with a unique historical scene with a large number of contemporaneous, high-ranking participants. Another distinguishing feature that we have not yet mentioned is the differentiation in the body color of the individuals. While the majority of the figures have an orange-brown skin color, a few of the individuals, including the prominently situated N1 and possibly also S2 and S6, have a much darker brown-black coloration suggesting body paint. Cross-culturally in Mesoamerica, such dark skin coloration is normally indicative of either a priestly or military function (Nehammer Knub Reference Nehammer Knub2010:53–76). Thus, it seems most likely that the composition represents a gathering of individuals of elevated rank, including priests and possibly warrior-priests, participating in an important ritual. When viewed in the light of the comparative data mentioned above, it remains a possibility that this is a scene of investiture taking place at the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on a comparative approach involving similar benches from other regions of Mesoamerica in combination with a careful iconographic analysis of the surviving motifs, we suggest that the benches of Structures B2-2, G3, and K2 were essentially seats or thrones serving high-ranking Xochicalco individuals, quite possibly the rulers of the city. While their locations and decoration would seem to exclude that the benches had a basic domestic function, we do not have enough evidence to definitely conclude that any of them served as a throne for a ruler, although the possible mat design of the G3 Bench makes this the best candidate. The iconography as well as the remaining glyphs of the three benches clearly conforms to the cultural traditions inherited from earlier central Mexican cultures. Considering what has previously been commented on the Maya influence at Cacaxtla (Foncerrada de Molina Reference Foncerrada de Molina and Robertson1980, Reference Foncerrada de Molina1993; Helmke and Nielsen Reference Nielsen, Helmke and Sachse2014; Kubler Reference Kubler and Robertson1980; Quirarte Reference Quirarte and Miller1983) and Xochicalco (Coe and Koontz Reference Coe and Koontz2002:132–139; Hirth Reference Hirth2000:264–266; Townsend Reference Townsend2009:38–41), however, and most notably the cross-legged figures on the lower talud platform of the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent (Nagao Reference Nagao, Diehl and Berlo1989:93–96, 98, Figure 15; see also Litvak King Reference Litvak King1972), it is worth noting that the benches and their imagery also display certain similarities to Maya benches and iconography, in particular with the Terminal Classic city of Chichen Itza. This raises the intriguing possibility that Tula was not alone in exchanging ideas and practices with Chichen Itza, but that Xochicalco also was an important player in this network stretching from northern Yucatan to present-day Hidalgo, Querétaro, and Guanajuato. Perhaps, Tula (or more precisely Tula Chico) and Xochicalco were both involved in this system, and it was only later, in the Early Postclassic and after the demise of Xochicalco, that the relationship between Chichen Itza, Tula Grande, and El Cerrito reached the intensity that the architecture and iconography of the three cities seem to indicate (Nielsen et al. Reference Nielsen, Helmke and Fenoglio2018). Fragments of monuments with calendrical signs that clearly date to the Epiclassic have been found at Tula (de la Fuente et al. Reference de la Fuente, Trejo and Solana1988:Figures 147, 155–155a, 161), and recent excavations at Tula Chico has revealed numerous sculptured reliefs from the same time period (Mastache et al. Reference Mastache, Healan, Cobean, Fash and Luján2009:311–316; Suárez Cortés et al. Reference Suárez Cortés, Healan and Cobean2007). The exact types of relationship between these cities probably varied, and may have encompassed trade, traveling artisans, and inter-elite interaction, but we are only just beginning to understand these complex relations. As such, the painted benches of Xochicalco and their rich iconography provide us with a rare, but very important glimpse onto the city's interaction with a wider Mesoamerican sphere, and serve to remind us about the continuous relationship between central Mexico and the Maya area throughout much of the history of Mesoamerica.

RESUMEN

La tradición cultural de murales policromados en el centro de México se remonta al clásico temprano en Teotihuacán y continúa hasta el epiclásico con los impresionantes murales de Cacaxtla, siendo éstos los ejemplos más famosos y mejor estudiados. En este trabajo presentamos tres ejemplos de bancas o tronos estucados y ricamente pintados del importante sitio epiclásico de Xochicalco, Morelos, México. Un análisis iconográfico y epigráfico cuidadoso de las imágenes, así como de los signos jeroglíficos asociados a una de las bancas, nos lleva a sugerir que éstas desempeñaron un papel esencial en el despliegue de los aspectos religiosos, mitológicos e históricos que fundamentaron el poder jerárquico en Xochicalco. Con base en comparaciones con las bancas y los asientos de la cultura maya clásica y, en particular, con las de la ciudad contemporánea del clásico terminal, Chichén Itzá, cuyas relaciones interregionales con el centro de México trascendieron, también sugerimos que las bancas de Xochicalco pudieron haber servido como asientos o tronos reales.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to extend our gratitude to the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, and to the members of the Consejo de Arqueología, for issuing a research permit [P.A. 14/09, 401-1-666] allowing us to conduct our documentation project at Xochicalco. In particular, we would like to thank the late Arqlgo. Roberto García Moll, Lic. Alfonso de María y Campos Castello, Arqlgo. Salvador Guilliem Arroyo, Lic. María del Perpetuo Socorro Villareal Escárrega, Norberto González Crespo, and Silvia Garza Tarazona. For letters of introduction, assistance, and encouragement, we thank her Excellency Martha Bárcena Coquí, former Ambassador of Mexico to Denmark. In matters of correspondence and accounting of project finances, we also thank Arqlgo. Pablo Sereno, Patricia Apáez Legorreta, Dolorez Juárez, as well as Lykke Ditlefsen and Jane Engelund Poulsen. This project would not have been possible without funding from the Research Council for the Humanities of the Danish Ministry of Science Technology and Innovation, as well as funds from the Institute of Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies of the University of Copenhagen. An earlier version of this work was presented at the Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, Universidad Autónoma de México and the University of Riverside in California, and we wish to thank all participants of the two seminars for their valuable suggestions and comments. Many heartfelt thanks to Dra. María Teresa Uriarte, director of the Proyecto La Pintura Mural Prehispánica en México, for her generosity, kindness, and help over the years, and for her permission to include photographs from the archives of the the Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas. For assistance and help with crucial references, we wish to thank Fernanda Salazar, Katarzyna Mikulska-Dabrowska, Michel Oudijk, Ángel Iván Rivera Guzmán, Dorie Reents-Budet, Karl Taube, Rex Koontz, and Casper Jacobsen. We would also like to acknowledge the editors, the anonymous reviewer, and Kenneth Hirth for reviewing this paper and for their insightful comments. The present paper was finalized as part of the research program The Origins and Developments of Central Mexican Calendars and Writing Systems (ca. a.d. 200–1600), funded by the Velux Foundation (Grant No. 00021802).