Introduction

Sri Lanka, an island nation in the Indian Ocean located between 5.083°N and 9.083°N and 79.7°E and 81.88°E, is a beneficiary of the “Green Revolution.” The crop-yield increments attributed to the “Green Revolution” are directly tied to intensified input, such as seeds and planting materials, fertilizer, and pesticides, which have transformed the agricultural landscape (Ramankutty et al. Reference Ramankutty, Mehrabi, Waha, Jarvis, Kremen, Herrero and Rieseberg2018). The development and adoption of high-yielding rice (Oryza sativa L.) varieties and other related technologies, including use of agrochemicals over the past seven decades since independence, have enabled the country to achieve almost complete self-sufficiency in rice production. The use of agrochemicals has become popular owing to their potential for and quick action in destroying pests under a wide range of ecological conditions (Marambe et al. Reference Marambe, Abeysekara, Herath, Rao, Yaduraju, Chandrasena, Hassan and Sharma2015; Mohottige et al. Reference Mohottige, Sivayoganathan and Wanigasundera2002). Intensified input in agriculture has increased over the years at the global scale (Foley et al. Reference Foley, Ramankutty, Brauman, Cassidy, Gerber, Johnston, Mueller, O’Connell, Ray, West, Balzer, Bennett, Carpenter, Hill and Monfreda2011), exceeding the rates of agricultural expansion. However, this has also led to substantial concerns surrounding agrochemicals’ impact on production costs and human and environmental health (Mohottige et al. Reference Mohottige, Sivayoganathan and Wanigasundera2002).

The government of Sri Lanka (GoSL) has imposed stringent regulations to control the importation and use of pesticides and has shown serious concern about global and national reports on human health impacts of these agrochemicals. The complete ban on import and use of glyphosate in Sri Lanka in 2015, which was done without a scientifically valid risk assessment and justification, had a significant negative impact across the agricultural industry, scientists, academia, and practitioners, and the overall weed management and crop production. This review thus focuses on the impact of the ban imposed on glyphosate on the agricultural sector in Sri Lanka.

Weed management in Sri Lankan agriculture

Insect pests, weeds, and diseases negatively impact crop farming. Crop losses due to pests and diseases, despite efforts made to control them, range from 10% to 90% (Oerke Reference Oerke2006). Weeds have evolved to be the most troublesome biological constraint to any form of crop production (De Silva et al. Reference De Silva, Liyanage, Wijesekera, Prematunga and Pushpakumari2018; Marambe et al. Reference Marambe, Abeysekara, Herath, Rao, Yaduraju, Chandrasena, Hassan and Sharma2015; Rao et al. Reference Rao, Wani, Ahmed, Ali, Marambe, Rao and Matsumoto2017). In an island-wide survey, about 80% of Sri Lankan farmers reported weeds as the main constraint in rice production (Ratnasekera Reference Ratnasekera2010). In Sri Lanka, weeds have reduced the quantity of crop yields by 40% to 50% (Amarasinghe et al. Reference Amarasinghe, Marambe and Rajapakse1999) or even higher (Chauhan Reference Chauhan2013; Marambe Reference Marambe2009) and also the quality of the crops produced, thereby reducing overall land productivity and farmers’ incomes (Amarasinghe and Marambe Reference Amarasinghe and Marambe1998; Rajapakse et al. Reference Rajapakse, Chandrasena, Marambe and Amarasinghe2012).

The Sri Lanka Council for Agricultural Research Policy (SLCARP) of the Ministry of Agriculture has identified weeds of national significance (WONS) (Marambe et al. Reference Marambe, Jayasekera, Amarasinghe, Ahangama and De Soyza2008, Reference Marambe, Jayasekera, Samarasinghe and Kumara2011), prioritizing WONS in the overall weed management strategies in the country. The latest WONS list included weeds in major crop sectors such as rice, other field crops, waterways, and plantation crops (SLCARP 2017). The negative impacts caused by weeds have prompted farmers to take all possible measures to control them to safeguard farming interests. Among the different weed control techniques available, herbicides are the main tool for weed control selected by the farming community in south Asia, with the aim being economic and optimal productivity (Marambe et al. Reference Marambe, Abeysekara, Herath, Rao, Yaduraju, Chandrasena, Hassan and Sharma2015; Rao et al. Reference Rao, Johnson, Sivaprasad, Ladha and Mortimer2007, Reference Rao, Wani, Ahmed, Ali, Marambe, Rao and Matsumoto2017). Based on efficacy and economics, global herbicide use has increased by 2.5 times from 54 to 136 million kg of formulated herbicides during the period of 2005 to 2015 (Das Gupta et al. Reference Das Gupta, Minten, Rao and Reardon2017). The use of glyphosate for weed control in agriculture in Sri Lanka is presented later in this review.

Pesticide regulations in Sri Lanka

Pesticides are either imported to Sri Lanka in bulk for repackaging or as technical-grade material for local formulation before being sold. The Sri Lanka Customs Ordinance No. 17 of 1869 and Sri Lanka Customs (Amendment) Act No. 9 of 2013 made an import license a requirement for every consignment of pesticides. The Control of Pesticides Act No. 33 of 1980, implemented by the Registrar of Pesticides (RoP), makes regulatory provisions for quantities/volumes of pesticides imported and used in the country and for introduction of pesticides with lower mammalian toxicity. Under section 17 of the Sri Lanka Customs Act No. 9 of 2013, the Imports Controller of Sri Lanka issues import licenses on a consignment basis only upon receiving written approval from the RoP.

By the authority vested under the Control of Pesticides Act (as amended), the RoP of the government Department of Agriculture (DoA) implements laws and regulations, including compulsory registration, to govern pesticide importation and use in conformation with international conventions relevant to pesticides. A statutory body, the Pesticides Technical and Advisory Committee, comprising 15 members (representing government agencies and five members appointed by the Hon. Minister of Agriculture who have no vested interests in pesticide imports and marketing in Sri Lanka), is responsible for providing required advice to the RoP on policy and technical matters regarding pesticides. The regulatory process is also focused on safeguarding food quality and human and environment health against pesticides. Sri Lanka has implemented necessary measures to replace all persistent pesticides with safer chemical alternatives (Sumith Reference Sumith2005). The number of currently registered active ingredients and pesticide products marketed are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Registered and marketed agro-pesticide active ingredients in Sri Lanka (2017).a

a From S Jayakody, Registrar of Pesticides, personal communication.

Sri Lanka is a party to the Basel, Rotterdam, and Stockholm Conventions, which share the common objective of protecting human health and the environment from hazardous chemicals and wastes. The country has banned Class 1a and Ib pesticide products (WHO 2005) from being imported and used, and thus the majority of pesticides allowed in Sri Lanka are WHO Class II or III (RoP 2017). From 2002 to 2016, the number of Class II pesticide products was reduced by 29% either by nonissuance of the import licenses or by banning the product from being imported, while the number of Class III and Class IV products increased by 91% and 41%, respectively.

Herbicides banned from importation and use in Sri Lanka

Pesticides are banned by different governments in response to problems experienced within a country or in other countries. When a range of products are banned or withdrawn for health or environmental reasons, the fate of existing stocks is often given scarce consideration by many countries where such stocks remain stored and eventually deteriorate (Food and Agriculture Organization [FAO] 2019). The Pesticide Action Network (2017) reported that one or more of 106 countries surveyed have banned a total of 370 pesticide active ingredients or groups of active ingredients, of which, about 51 are herbicides. Among the herbicides banned, alachlor tops the list by being banned in 48 countries worldwide (including 5 South and Southeast Asian countries), while Sri Lanka has banned six herbicides (Table 2).

Table 2. Herbicides banned from importation and use in Sri Lanka.

a EC, European Commission; SL, Sri Lanka.

b Ban of registration by the government Extraordinary Gazette No. 1190/24 of June 29, 2001, under the Control of Pesticides Act No. 33 of 1980.

c Ban of registration by the government Extraordinary Gazette No. 1854/47 of March 21, 2014, under the Control of Pesticides Act No. 33 of 1980.

d Regional restriction for sale, offer for sale, and use as per the government Extraordinary Gazette No. 1894/4 of December 22, 2014, under the Control of Pesticides Act No. 33 of 1980.

e Ban of importation by the Gazette Extraordinary No. 1813/14 of June 5, 2015, under the Import and Export (Control) Act No. 01 of 1969 and Gazette Extraordinary No. 1937/35 of October 23, 2015.

Herbicide imports to Sri Lanka have fluctuated over the years (Figure 1) due to stringent control on volumes imported. For example, a reduction of about 25% of total pesticides imported to Sri Lanka was observed in 2015 due to the bans imposed on paraquat in 2014 and glyphosate in 2015. The ban on paraquat was imposed after a detailed study on self-poisoning (Gunnell et al. Reference Gunnell, Fernando, Hewagama, Priyangika, Konradsen and Eddleston2007) with the product. A phase-out program was initiated in 2008 with the introduction of a formulation with 6.5 g L–1 paraquat replacing the 200 g L–1 formulation until the complete ban was imposed. However, the ban on glyphosate in Sri Lanka shocked scientists and agriculturists in the country, as the decision taken by the GoSL did not go through a proper consultative process and was not evidence based, but resulted from social pressure linked to classification of the herbicide as “probably carcinogenic to humans” by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC 2015). The GoSL lifted the ban 2 yr after its imposition for 36 mo for two selected perennial crops, highlighting the need to have scientifically valid justification for decision making that affects the agriculture and food security of the country. Hence, the following sections of this paper will focus on the glyphosate ban in Sri Lanka.

Figure 1. Herbicides imported to Sri Lanka from 2000–2016. (A) Regulatory ban of paraquat 200 g L–1 SL). (B) Regulatory ban of paraquat (65 g L–1 SL). (C) Regional restriction of sale on propanil (360 g L–1 EC). (D) Regional restriction of sale on glyphosate (360 g L–1 SL). (E) Regulatory and legal ban on importation of glyphosate (360 g L–1 EC). From RoP (2018). EC, European Commission; SL, Sri Lanka.

The case of glyphosate in Sri Lanka

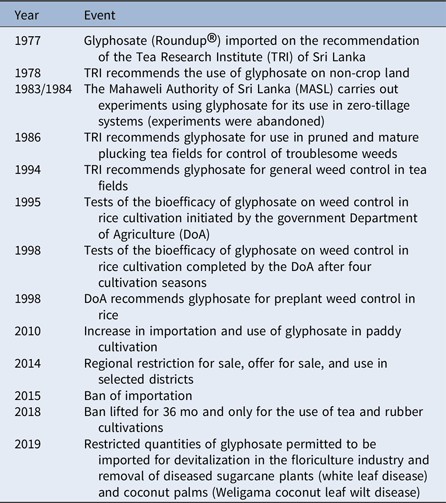

Glyphosate was first imported to Sri Lanka in 1977 through the intervention of the Tea Research Institute (TRI) of Sri Lanka, with initial use being confined to experimental use on roadsides, ravines, boundaries, and abandoned tea [Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntz.] fields for the control of problem weeds such as torpedograss (Panicum repens L.). The chronology for events since its introduction is presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Chronological events on the use of glyphosate in Sri Lanka.

Based on successful bioefficacy and herbicide residue studies, the TRI recommended glyphosate in pruned tea fields and mature plucking fields (after three pruning cycles) to control troublesome weeds in 1988 and for general weed control in tea in 1994. The DoA evaluated the herbicide for weed control during land preparation of rice in 1995 and recommended the herbicide for preplant weed control in rice in 1998. However, the herbicide did not initially attract rice farmers due to the availability of the low-cost and quick-acting herbicide paraquat. According to the RoP (2018), in 1987, Sri Lanka imported 120,000 kg of the formulated product of paraquat (200 g L–1) for 570,000 ha and 16,000 kg of glyphosate (360 g L–1) for 10,000 ha of land. Tea plantations consumed about 10% of the glyphosate products imported in 1987, while 408,000 ha of tea lands used 82,000 kg of imported paraquat for weed control. During the late 1980 s, about 250,000 ha of paddy fields used 50,000 kg of paraquat (20% w/v) with no records of the use of glyphosate for preplant weed control in paddy cultivation. However, in the late 1990 s, the annual importation of glyphosate (360 g L–1) increased to about 129,000 kg, and paraquat (200 g L–1) importation decreased to 21,000 kg. Glyphosate use has shown an increase in preplant weed control, replacing paraquat.

Glyphosate importation and use increased dramatically following first the paraquat phase-out process initiated in 2008 (due to historical records on self-poisoning using the herbicide) and then the complete ban imposed in 2014 (Figure 2). Glyphosate was also identified as an effective alternative to control paraquat-resistant tall fleabane [Erigeron floribundus (Kunth) Sch. Bip.] (Marambe et al. Reference Marambe, Nissanka, De Silva, Anandacoomaraswamy and Priyantha2002) and redflower ragleaf [Crassocephalum crepidioides (Benth.) S. Moore] (Marambe et al. Reference Marambe, Jayaweera and Hitinayake2003). However, Prematillake (Reference Prematillake2013) reported speculation that both these weeds may have developed resistance to glyphosate (Prematillake Reference Prematillake2013). Further, since the beginning of the 21st century, a large number of glyphosate-based products were imported to Sri Lanka at a cheaper price and, consequently, glyphosate became popular among paddy and maize (Zea mays L.) growers, in addition to tea planters.

Figure 2. Importation of glyphosate to Sri Lanka since 2005.

Herbicides have been identified as a main causal factor of the noncommunicable disease reported in several paddy growing areas in Sri Lanka: chronic kidney disease of uncertain etiology. Jayasumana et al. (Reference Jayasumana, Gunatilake and Senanayake2014) hypothesized that glyphosate may destroy the renal tissues of farmers by forming complexes with a localized geo-environmental factor (hard water) and nephrotoxic metals. Though not scientifically proven, owing to social pressure created in the country, the government of Sri Lanka via Gazette Extraordinary No. 1894/4 of December 22, 2014, restricted glyphosate use in five main districts, namely, Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa, Kurunegala, Moneragala, and within the Divisional Secretariat Divisions of Mahiyanganaya, Rideemaliyadda, Kandaketiya, in the Badulla District of Sri Lanka (Gazette Extraordinary No. 1894/4), where paddy is mainly cultivated. The herbicide was later banned from importation and use in 2015 by the Gazette Extraordinary No. 1813/14 of June 5, 2015, under the Import and Export (Control) Act No. 01 of 1969 as amended, and Gazette Extraordinary No. 1937/35 of October 23, 2015, under the Control of Pesticides Act. However, FAO-WHO (2017) reported that glyphosate is unlikely to be genotoxic and unlikely to pose a carcinogenic risk to humans from exposure through the diet. According to CropLife Sri Lanka, of the glyphosate imported in 2014 (Table 4), tea consumed the highest (29%) quantity followed by maize (23%), paddy (17%), and vegetables (14%). On average, about 60% to 70% of the rice farmers (DoA 2018) and all maize growers in selected dry zone districts (Abeywickrama et al. Reference Abeywickrama, Sandika, Sooriyaarachchi and Vidanapathirana2017) used glyphosate before imposition of the herbicide ban. All major plantations and about 50% of tea smallholders used glyphosate for weed control (TRI 2017). This highlights the significant contribution of glyphosate to weed control under different crop-production systems. Further, paddy cultivated in the wet zone (>2,500 mm annual average rainfall) of Sri Lanka has consumed 12.6%, while that in the dry zone (<1,750 mm of annual average rainfall), where 70% of the paddy land is located (Chithranarayana and Punyawardena Reference Chithranarayana and Punyawardena2014), consumed only 4.4% of the glyphosate products imported.

Table 4. Use of glyphosate in Sri Lanka in 2014.a

a From CropLife Sri Lanka (C Fernando, personal communication).

b According to the Tea Research Institute (TRI), the requirement of glyphosate is approx. 500,000 L following the recommendation to apply the herbicide only twice per year.

The impact of the glyphosate ban in Sri Lanka

Several studies have been conducted in Sri Lanka to detail the impact of the ban of glyphosate on crop production and the national economy. A recent study concluded that nonavailability of glyphosate for preplant weed control in paddy cultivation has increased the cost of weed control from 1.29% of the total cost of production to 4.58%, and the majority of the study sample (56%) has shifted to other less effective herbicides (Malkanthi et al. Reference Malkanthi, Sandareka, Wijerathne and Sivashankar2019). Further, the FAO–World Food Program (2017) highlighted the presence of high weed populations in paddy fields due to the absence of glyphosate as a preplant weed control measure.

The glyphosate ban has reduced the cultivated acreage of maize in Anuradhapura District (the main agricultural district in Sri Lanka’s North Central Province) from 10,900 ha to just above 4,050 ha in 2017 (DoA 2017). Part of this reduction in cultivated acreage should be attributed to water-deficit conditions as well. The cost of maize production has increased from Rs 113,135 ha−1 in the 2013/2014 Maha season (October to February; approx. US$636 ha−1 at the current exchange rate) at a time when glyphosate was readily available for preplant weed control, to Rs 157,096 ha−1 in the 2015/2016 Maha season (approx. US$883) (DoA 2017), mainly due to the absence of glyphosate for weed control and/or use of manual labor for weed control. Due to the absence of a cost-effective weed control measure, the profits for maize cultivation have been reduced by about 25%, while about 89% of smallholders and 73% of larger-scale maize farmers have reduced their cultivated acreage due to higher costs of cultivation, thus decreasing Sri Lanka’s domestic maize production (Abeywickrama et al. Reference Abeywickrama, Sandika, Sooriyaarachchi and Vidanapathirana2017). This combined effect has impacted maize production in Sri Lanka, with the country importing 179.6 million kg of maize for animal feed in 2017, a 428% increase compared with 2016, to fulfill the annual requirement for animal feed (DoA 2018). A study on the impact of the ban on glyphosate has revealed a reduced family income for more than 94% of smallholder maize farmers, while reduced family income and increased production costs were reported for more than 86% of maize farmers in 2016 (Abeywickrama et al. Reference Abeywickrama, Sandika, Sooriyaarachchi and Vidanapathirana2017).

The loss of tea production without weed control has been estimated as 33.2 million kg yr−1, causing an economic loss (reduction in export earnings) of Rs 26.7 billion yr−1. The ban on broad-spectrum herbicides, including glyphosate and paraquat, is one of the key factors in reducing total tea production since 2014 (Figure 3). The unfavorable climate in 2016 reduced tea yield drastically, but the yield did not totally recover even in a favorable climate in 2017. Thus, it is justifiable to conclude that the ban imposed on herbicides is the main contributor to the yield reduction in tea.

Figure 3. Total made tea production in Sri Lanka (2014–2017). From De Silva et al. (Reference De Silva, Liyanage, Wijesekera, Prematunga and Pushpakumari2018).

The ban has triggered the heavy use of more hazardous and nonrecommended herbicides and has also promoted smuggled products in the country (Abeywickrama et al. Reference Abeywickrama, Sandika, Sooriyaarachchi and Vidanapathirana2017). The price of a 4-L container of smuggled glyphosate has increased by 300% to 350%, from Rs 4,000 (approx. US$22.50) before the ban was imposed to Rs 12,000 to 14,000 (approx. US$67.40 to US$78.70) at present. The impact of the absence of an effective weed control technique in tea cultivation has been discussed and debated heavily. De Silva et al. (Reference De Silva, Liyanage, Wijesekera, Prematunga and Pushpakumari2018) reported that the ban on glyphosate has compelled tea planters to use alternate chemicals such as diuron and MCPA, leading to detection of residues from these herbicides in made tea exported from Sri Lanka, affecting the country’s economy. The maximum residue limits for MCPA in Japan and the European Union are 0.01 and 0.05 ppm, respectively, while those for diuron are 1 ppm and 0.05 ppm, respectively (EU 2013; Japan Food Chemical Research Foundation 2017). The costs associated with the return of several consignments of tea owing to detection of these herbicides were a staggering Sri Lankan Rs 1 billion (approx. US$5.6 million). The Planters’ Association of Sri Lanka estimated a loss of Rs 10 to 20 billion yr−1 (Y Silva, personal communication) due to the ban of glyphosate. This is mainly owing to the increased cost of production with the use of labor-intensive alternate weed control techniques or abandoning weed control in tea fields as a result of scarce and costly labor resources. Additional cost for manual weeding in tea compared with a combination of chemical and manual weeding has been calculated as Rs 2.70 to 19.01 kg−1 of made tea (approx. US$0.015 to US$0.106; Shyamalie Reference Shyamalie2016)

In rubber tree [Hevia brasiliensis (Willd. ex A. Juss.) Müll. Arg.] cultivation in Sri Lanka, a cost–benefit comparison of weed control with glyphosate against manual weeding has revealed ratios of 1.3 and 1.17, respectively (RRI 2016). In coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) cultivation, the highest return on investment (benefit:cost ratio of 7.51) was reported by the application of glyphosate as a weed control tool compared with other mechanical and agronomic techniques (Senarathne and Perera Reference Senarathne and Perera2011). Further, the Coconut Research Institute (CRI) of Sri Lanka has identified use of glyphosate as the most successful and cost-effective approach to destroy disease-affected plants by injecting glyphosate into trees to prevent dispersion of Weligama coconut leaf wilt disease (Office of the Cabinet of Ministers of Sri Lanka [OCM] 2019). In sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.) cultivation in Sri Lanka, the cost of weed control has increased by Rs 5,000 to 10,000 ha−1 (approx. US$28 to US$56) due to adoption of different weed control methods in response to the ban on glyphosate (S Keerthipala, Sugarcane Research Institute [SRI], personal communication). Further, absence of glyphosate has affected stool eradication and disease management through destruction of diseased clumps infected by the devastating white leaf disease. Cut-flower and foliage exports from Sri Lanka to Australia were stopped, as all plant parts exported to Australia must be devitalized (propagation inhibited) by treatment with glyphosate (Government of Australia 2019). Australia does not accept any alternative treatment. Absence of glyphosate-based products has thus affected floriculture exports and their further expansion in Australia (Export Development Board of Sri Lanka 2017).

Abeywickrama et al. (Reference Abeywickrama, Sandika, Sooriyaarachchi and Vidanapathirana2017), assessing the situation after the glyphosate ban was imposed, reported that the ban is not effective and the objectives of the ban have not been achieved, as about 50% of farmers are using glyphosate smuggled to Sri Lanka in the form of different, unknown, but still expensive formulations. Further, pesticide dealers have also been reported to be selling unlabeled adulterated glyphosate products directly to farmers.

Lifting the glyphosate ban for a limited time period

The irrational decision taken to ban the herbicide glyphosate in Sri Lanka has not only negatively affected the agricultural sector and national economy, but has led to increased damage to human and environmental health due to the alternative herbicides required for weed control. A broader stakeholder consultation held in this regard resulted in the GoSL lifting the ban on glyphosate in 2018 through Gazette Extraordinary No. 2076/4 of June 18, 2018, under the Import Export Control Act No 1 of 196 (as amended) and Gazette Extraordinary No. 2079/37 of July 11, 2018, under the Control of Pesticides Act. The lifting of the ban, however, is only for a period of 36 mo, and the herbicide is only to be used in tea and rubber cultivation (requirement approx. 520,000 L of glyphosate products at 360 g L–1). Following the gazette notification, a special circular issued by the RoP also banned the importation of any polyethoxylated tallow amine (POEA)-containing glyphosate formulations. This follows from the European Commission’s ban of the co-formulant POEA from glyphosate-based products (EC 2016). With the new regulations imposed in Sri Lanka, only three private companies have been allowed to provide financial bids for importation of glyphosate. However, once procured, glyphosate can only be distributed by Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (Ceypetco®), which is a government-owned business undertaking with the authority to sell pesticides. Recently, a joint proposal was made by the Hon. Minister of Plantation Industries and the Hon. Minister of Development Strategies and International Trade to the Cabinet of Ministers in Sri Lanka to extend the use of glyphosate in agriculture (OCM 2019). Accordingly, approval has been granted to import 200 L of glyphosate (360 g L–1) for use in devitalization of propagatable floriculture items on the recommendation of the Export Development Board; 31,815 L to the SRI to destroy sugarcane plants infected with white leaf disease; and 200 L to the CRI to kill coconut palms infected with Weligama coconut leaf wilt disease. For these purposes, glyphosate will be imported and distributed through Ceypetco®.

Conclusion

The ban on glyphosate was imposed without scientific evidence. The agricultural sector and the Sri Lankan economy have taken the brunt of this disastrous and abrupt policy decision. Climate change has further exacerbated the impact of the glyphosate ban. By nature, weeds thrive and compete vigorously with crops when resources are limited and negatively impact final harvests. Sri Lanka has stringent regulations imposed on legal importation of pesticides. Glyphosate was imported to Sri Lanka from the early 1980 s to 2014 at 36% w/v concentration. The ban imposed on importation of glyphosate to the country opened the door to entry of illegal products with no quality control. Hence, agricultural practitioners have become the victims again. The societal forces based on political and spiritual ideologies have unfortunately continued to succeed in Sri Lanka, overruling even the most basic scientific principles. Policy makers must follow science and make evidence-based decisions, considering the totality rather than focusing on reaping political gains out of the situation. Scientists, too, need to support the policy makers by being open and providing conclusive and scientifically valid data to facilitate decision making.

The FAO (2019) clearly stated that a good practice when banning a pesticide requires pesticide regulatory authorities to allow a phase-out period to support the uses of stocks and also to give practitioners and scientists time to look for economically and practically effective alternatives. Corrective measures have now been taken after few disastrous years, and the country is hopeful that no such abrupt decision will be taken in the future without a proper consultative process, ignoring vested political interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the research officers of the Department of Agriculture and the four commodity research institutes, namely, the Tea Research institute, Rubber Research Institute, Coconut Research Institute, and Sugarcane Research Institute, for the support extended in preparing this article. Preparation of this paper received no specific grant from any funding agency or the commercial or not-for-profit sectors. No conflicts of interest have been declared.