Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is characterised by re-experiencing through sensory modalities of traumatic event(s) in the form of nightmares or flashbacks, avoidance of trauma-related stimuli, negative alterations in cognitions and mood, and trauma-related changes in arousal following exposure to a traumatic stressor. The cognitive model suggests that PTSD is maintained by avoidance of thoughts, memories and reminders associated with the event(s) (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000). PTSD sufferers may experience hypervigilance to threat and, untreated, symptoms tend to persist, which can impact psychosocial functioning (Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Hill, O’Ryan, Udwin, Boyle and Yule2004). It is essential to treat PTSD given the long-term health and functioning implications (McFarlane, Reference McFarlane2010; Mulvihill, Reference Mulvihill2005), alongside the potential impacts on the developing brain (Herringa, Reference Herringa2017). PTSD is also associated with increased likelihood for co-morbidities such as depression, chronic physical illness, alcohol misuse and suicidality (Karatzias et al., Reference Karatzias, Hyland, Bradley, Cloitre, Roberts, Bisson and Shevlin2019).

In an epidemiological study of a representative cohort of young people in England and Wales, it was found that, of the 31.1% of children who were exposed to trauma (defined using DSM-5 criteria), the lifetime prevalence of PTSD by age 18 was 25.0% (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Arseneault, Caspi, Fisher, Matthews, Moffitt, Odgers, Stahl, Teng and Danese2019). For those who were trauma-exposed, more than half had experienced or witnessed some form of interpersonal trauma (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Arseneault, Caspi, Fisher, Matthews, Moffitt, Odgers, Stahl, Teng and Danese2019). However, prevalence estimates are likely to differ depending on the diagnostic system used.

A variety of risk factors have been found to increase the likelihood of a young person experiencing PTSD, including low social support, peri-trauma fear, social withdrawal and poor family functioning, amongst others (Trickey et al., Reference Trickey, Siddaway, Meiser-Stedman, Serpell and Field2012). Insecure attachment with caregivers is also associated with a greater severity of PTSD symptoms (Kimerling et al., Reference Kimerling, Allen and Duncan2018; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Zhen and Wu2020). The range of relational risk factors suggest it may be important to incorporate consideration of such factors into formulations of the development and maintenance of PTSD.

For adolescents, NICE recommends that an individual TF-CBT intervention is offered, with more than 12 sessions if there are multiple traumas (NICE, 2018). TF-CBT involves stabilisation, reliving work on the trauma memories, and reconnecting with valued aspects of life (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Mannarino and Deblinger2006; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Perrin, Yule and Clark2010). A meta-analysis identified that TF-CBT produced medium to large effect sizes compared with control conditions for child and adolescent PTSD, as well as small to medium effect sizes in reducing co-morbid depression symptoms (Morina et al., Reference Morina, Koerssen and Pollet2016). The PRACTICE (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Mannarino and Deblinger2006) acronym summarising the trauma-focused CBT protocol for children incorporates parenting skills and conjoint child–parent sessions to help elaborate and process trauma memories. It is known that caregiver involvement has an influence on outcomes in TF-CBT (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Cohen and Mannarino2020).

As argued by Dummett (Dummett, Reference Dummett2006; Dummett, Reference Dummett2010), CBT with children and adolescents should incorporate interpersonal, family and systemic factors, together with developmental and attachment issues. A systemic CBT approach can improve interactional patterns, promote parental attunement, increase openness in communication, and provide new evidence for belief in key appraisals to change (Koch et al., Reference Koch, Stewart, Stuart, Mueller, Kennerley, McManus and Westbrook2010). This approach involves utilising standard cognitive behavioural techniques to intervene within a family system by promoting change in interpersonal maintenance factors (Dummett, Reference Dummett2006). It is known that communication between young people and their caregivers and caregiver support promotes recovery from exposure to traumatic events (Berkowitz et al., Reference Berkowitz, Stover and Marans2011). It is also understood that the onset, symptoms and treatment of PTSD can be impacted by interpersonal relationships; for instance, lack of social support is one of the largest predictors of developing PTSD (Brewin et al., Reference Brewin, Andrews and Valentine2000; Markowitz et al., Reference Markowitz, Milrod, Bleiberg and Marshall2009). The relevance of interpersonal factors to PTSD suggests that systemic interventions may be of benefit. A recent systematic review found that 10 of the 11 studies of systemic youth–caregiver interventions for young people exposed to trauma were successful at reducing trauma symptoms in young people, as well as improving relationships (McWey, Reference McWey2022). Many of the studies relied on CBT as a theoretical underpinning, which lends support to a systemic CBT approach, despite this being limited by the small number of studies conducted to date.

The following case report describes how Dummett’s systemic CBT formulation facilitated intervention planning such that systemic sessions were incorporated into TF-CBT with an adolescent who had developed PTSD following traumas within the family home.

Case study

Client characteristics and presenting problem

Isla (pseudonym) is a 16-year-old, white British female who was referred to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) via her GP, who identified her difficulties as low mood, poor sleep and suicidal ideation.

Isla lives at home with her mum and dad. Her 19-year-old sister has a diagnosis of emotionally unstable personality disorder (EUPD) and had recently moved out of the family home to live independently. Following this, Isla developed symptoms of PTSD where she re-experienced memories of conflict and suicide attempts by her sister and experienced frequent nightmares related to these events. This was coupled with other traumatic experiences, including sexual assault by a peer.

Course of therapy

Treatment plan

Treatment was conducted over 18 sessions, which were completed during the coronavirus pandemic under lockdown. Sessions were conducted face-to-face wearing personal protective equipment and socially distanced with no notable impact of this on treatment. Phase A (assessment) consisted of three sessions, which focused on assessment, formulation and goal setting. During this phase, a stable baseline was established on the CRIES-8. Phase B (TF-CBT) consisted of seven sessions, focused on stabilisation, nightmare rescripting and cognitive reappraisal of maintaining beliefs. Phase C (systemic CBT) consisted of seven sessions, and focused on elaboration of trauma memories, enactment, interactional vicious cycles and behavioural change within the family. A final session was allocated to creation of a therapy blueprint.

Phase A: Assessment

Isla’s initial assessment was conducted by the therapist’s supervisor (C.H.). Clinical interview identified PTSD as the primary presenting problem (based on DSM-5 criteria), which was believed to be a leading cause of the low mood, poor sleep and suicidal ideation Isla had been referred for. Following a short period of time on a waiting list, Isla had three further assessment sessions with the therapist (B.V.), during which baseline scores on the Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale (CRIES-8) were established. Isla scored well above the clinical cut-off on this measure of trauma symptoms (Perrin et al., Reference Perrin, Meiser-Stedman and Smith2005). Information was gathered on PTSD symptoms, maintenance and severity; systemic factors, such as interpersonal relationships and conflict, and daily functioning at home and at school. Two SMART goals were developed with Isla: (1) to reduce the frequency and distress of intrusive thoughts and memories, particularly nightmares, and (2) to reduce the severity of anxiety and low mood. Isla’s history of traumatic experiences was obtained using a visual timeline created collaboratively in sessions. Key aspects of her history are summarised in Fig. 1, with the two major traumatic incidents of concern to Isla labelled as incident one and incident two.

Figure 1. Timeline produced with Isla of key life events.

Formulation

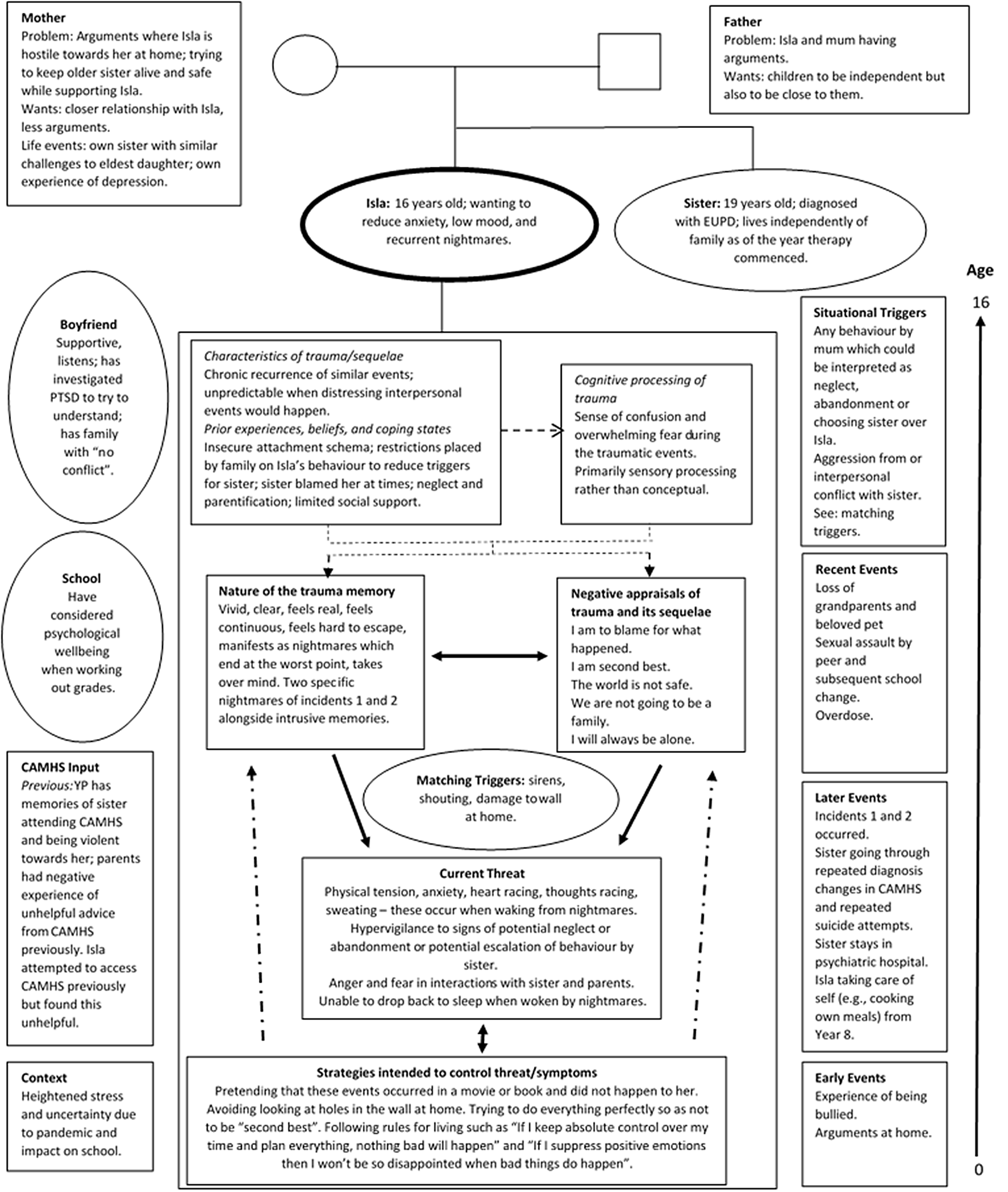

The Ehlers and Clark (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) model of PTSD was drawn with Isla to create an individualised formulation following on from psychoeducation around the dual representation theory of traumatic memories (Brewin et al., Reference Brewin, Dalgleish and Joseph1996). This was embedded in the systemic CBT formulation shown in Fig. 2, which incorporates the influence of parental perceptions of the problem and a timeline of Isla’s chronic experience of interpersonal stress and trauma.

Figure 2. Dummett’s (Reference Dummett2006) systemic CBT formulation incorporating Ehlers and Clark’s (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) model of PTSD.

The explanation of the brain regions and memory processes which may be implicated in PTSD was valued by Isla due to her wish to understand the rationale behind CBT intervention and why this works. It may be that this explanation provides both normalisation and externalisation of PTSD for young people. Similarly, collaborative development of the Ehlers and Clark (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) formulation facilitated understanding of the cognitive behavioural mechanisms contributing to the maintenance of PTSD. It also enabled shared agreement about the targets of intervention.

At the time of the key traumas, Isla reported being overwhelmed by fear and anger. She recalled being asked to take on age-inappropriate levels of responsibility during some of these events. Isla was asked to not discuss these events, which may have prevented her from processing the traumatic memories and eliciting social support, which is known to increase the risk of PTSD (Trickey et al., Reference Trickey, Siddaway, Meiser-Stedman, Serpell and Field2012).

Her parents’ understandable concern for the welfare of her sister meant that at times Isla’s physical and emotional needs went unmet, which may have contributed to the development of beliefs Isla held such as ‘I am second best’ and ‘I will always be alone’.

To cope, Isla avoided sleep, adhered to a rigid daily schedule, suppressed positive and negative affect, tried to behave perfectly, and tried to suppress intrusive memories. All these strategies prevented the processing of her traumatic memories and change in associated appraisals.

Information gathering and formulating, using Dummett’s systemic CBT template, began in Phase A. This continued throughout Phase B, as more information was gathered as a product of the intervention. This enabled systemic hypotheses to be developed which informed the planning of Phase C. For example, it was formulated that some of Isla’s negative appraisals of the traumas were being inadvertently maintained by the frequent arguments between Isla and her mother, which then contributed to the maintenance of unhelpful behavioural strategies, such as trying to do everything perfectly to avoid being second best and planning day-to-day life exactly to prevent negative events occurring.

Intervention Phase B: TF-CBT

Guided discovery was used to help Isla understand her difficulties and to embed learning. The therapeutic alliance was fostered through warmth, empathy, use of appropriate humour and curiosity. The review of Isla’s week and wellbeing each session provided opportunities for her to express her feelings and thoughts, instead of suppressing these, which helped build the therapeutic alliance (Ovenstad et al., Reference Ovenstad, Ormhaug, Shirk and Jensen2020). Agendas were collaboratively set every session and homework was reviewed. The frequency of nightmares each week was elicited via verbal report. Grounding techniques were introduced early during intervention to support Isla with managing affect and arousal following flashbacks and nightmares, in line with the stabilisation phase of TF-CBT.

The key techniques used in this TF-CBT intervention are listed in Table 1, alongside a brief description. Nightmares were prioritised for intervention as these were more frequent than flashbacks and Isla identified these as more impactful on her day-to-day functioning.

Table 1. Summary of the key TF-CBT techniques used in this study

Rescripting the nightmare of incident two enabled identification of the belief that she was to blame for her sister’s suicide attempt. Subsequent sessions focused on cognitive restructuring of this self-blaming belief. A ‘taking the thought to court’ metaphor was chosen, as Isla had expressed an interest in studying law. The therapist produced a video where she interviewed a dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) therapist from the CAMHS team using the questions Isla had suggested. The rationale for this was that the DBT therapist was ‘an expert’ in EUPD and may be able to provide insight into common factors associated with suicide attempts. This contributed to the evidence used in re-evaluating Isla’s appraisal that she was to blame for one of the traumatic events, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. ‘Taking the thought to court’ cognitive restructuring worksheet, adapted from Psychology Tools, which the therapist subscribes to

Throughout Phases A and B, Isla’s mother or father joined the final 10 minutes of therapy sessions. The purpose of this was to enhance shared understanding of the formulation and treatment; to encourage parental support during treatment; to provide opportunities to improve familial communication; and finally, to offer socialisation to treatment and support the transition to systemic CBT sessions. The therapist initially led on sharing session summary and facilitating discussion with Isla and her parents; however, consistent encouragement of Isla to take on the role of sharing feedback with her parents led to Isla beginning to do this in the latter half of Phase B.

Intervention Phase C: Systemic CBT

Isla became angry when her mother expressed doubt about the conceptualisation of EUPD offered by the DBT therapist. This initiated the start of the systemic CBT phase.

Interactional vicious cycles were collaboratively developed during systemic sessions using recent relational interactions. An abstract version summarising a characteristic argument between Isla and her mother is shown in Fig. 3. Isla recognised that her mother’s behavioural response to her in different situations unintentionally tended to reinforce her belief that she is second best, alone, and being let down. Her mother recognised that Isla tended to become angry due to believing she is being let down, rejected or abandoned. Formulating these cycles within sessions formed part of the intervention in Phase C.

Figure 3. Interactional vicious cycle showing general pattern which recurs in arguments between Isla and her mum, and the impact of this on reinforcing negative beliefs about herself and others.

In total, the systemic CBT sessions consisted of one parental session, two sessions with both parents and Isla, one session with Isla and her mother, and three individual systemic CBT sessions with Isla which involved trauma-focused elements. Key systemic techniques used are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3. Summary of the key systemic CBT techniques used

Therapy blueprint

A therapy blueprint was created which demonstrated the range of learning Isla gained from therapy, what had changed, and what she could do to manage setbacks.

Measures

PTSD symptoms were tracked each session using the Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale (CRIES-8) (Perrin et al., Reference Perrin, Meiser-Stedman and Smith2005). It was chosen due to acceptability and brevity. It has good construct validity and correlates well with other indices of post-traumatic stress. A clinical cut-off score of 17 maximises sensitivity and specificity for identification of PTSD.

Trauma cognitions were measured using the Child Post Traumatic Cognitions Inventory, Short Form (CPTCI-S) (Meiser-Stedman et al., Reference Meiser-Stedman, Smith, Bryant, Salmon, Yule, Dalgleish and Nixon2009). It has excellent internal consistency, moderate-high test–retest reliability and an excellent fit factor structure, with scores between 16 and 18 recognised as the optimal cut-off point for clinically significant negative appraisals (McKinnon et al., Reference McKinnon, Smith, Bryant, Salmon, Yule, Dalgleish, Dixon, Nixon and Meiser-Stedman2016). This was used in over half of the sessions (10/18) to ensure regular data collection while balancing a reduction in the burden of measure completion for Isla.

The full Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS) (Chorpita et al., Reference Chorpita, Moffitt and Gray2005) was administered at the start and end of therapy. The 10-item depression subscale was used every session to track changes. RCADS subscales have been shown to have good internal consistency. The depression subscale has good convergent validity identified by a significant, positive correlation with the Child Depression Inventory (Chorpita et al., Reference Chorpita, Moffitt and Gray2005). It has a clinical cut-off score of 13 for Isla’s age group (CORC, 2022).

The Systemic Clinical Outcome and Routine Evaluation (SCORE-15) (Stratton et al., Reference Stratton, Lask, Bland, Nowotny, Evans, Singh, Janes and Peppiatt2014) was used at the start and end of Phase C. It was administered to both Isla and her mother. This assesses aspects of family life and functioning which may be targets for therapeutic change. It consists of 15 Likert-scale items assessing family members’ perceptions of family life, such as ‘We seem to go from one crisis to another in my family’. There are six further items, three of which are qualitative. The SCORE-15 was found to have good criterion validity, good internal consistency, and good test–retest reliability (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Carr, Cahill, Cassells and Hartnett2015). Scores range from 15 to 75, with lower scores indicating better family functioning.

All outcome measures used are accepted by the CAMHS Outcome Research Consortium (CORC). The CAMHS session feedback questionnaire, obtained from the CORC website, was used repeatedly throughout to monitor Isla’s experience of sessions.

Outcome

Recovery from depression and PTSD

Isla’s score on the CRIES-8 at assessment was 38. This reduced over the course of treatment and at the end of treatment, Isla’s score was 11 – below the clinical cut-off score of 17, indicating recovery from PTSD (see Fig. 4). The reliable change index (Jacobson and Truax, Reference Jacobson and Truax1991) obtained for Isla’s scores on the CRIES-8 was 3.68 as calculated using data from Verlinden et al. (Reference Verlinden, van Meijel, Opmeer, Beer, de Roos, Bicanic, Lamers-Winkelman, Olff, Boer and Lindauer2014). Indices greater than 1.96 are likely to reflect real change. The calculation used is provided in Appendix A (see Supplementary material). This suggests a reliable change in PTSD symptoms. The reduction in avoidance and intrusions over time lends some support to the hypothesis that nightmare exposure, rescripting and rehearsal, alongside cognitive change facilitated by restructuring and systemic intervention, facilitated this decrease. Idiosyncratic data collected in sessions indicated that Isla’s nightmares reduced in frequency from two to three times per night at the start of therapy, to one to two per week by the end of therapy.

Figure 4. Graph displaying the change in CRIES-8 total score by session number. The black horizontal line indicates the clinical cut-off score for the CRIES-8.

At assessment Isla scored 36 on the CPTCI-S. This showed a reliable decrease over the course of treatment and reduced to 15 at the end of treatment, below the clinical cut-off of 16–18 (see Fig. 5). The RCI obtained for Isla’s scores on the CPTCI-S was 3.19 using data from McKinnon et al. (Reference McKinnon, Smith, Bryant, Salmon, Yule, Dalgleish, Dixon, Nixon and Meiser-Stedman2016). This suggests a reliable change endorsement of trauma-related cognitions. At the end of therapy, Isla did not feel she had sufficient evidence from her experiences for cognitions on the CPTCI-S, such as ‘bad things always happen’, to change. However, we discussed that these might change with further experiences.

Figure 5. Graph displaying CPTCI-S total score by session number. The black horizontal line indicates the clinical cut-off score for the CPTCI-S.

On the RCADS Depression Subscale, Isla scored 18 at assessment and this reduced to 6 at the end of treatment – below the clinical cut-off of 13. The RCI for the RCADS Depression Subscale was 4.19, as calculated using data from Klaufus et al. (Reference Klaufus, Verlinden, van der Wal, Kosters, Cuijpers and Chinapaw2020).

Isla’s mood improved over the course of therapy, as shown in Fig. 6, in conjunction with nightmare frequency decreasing and sleep improving.

Figure 6. Graph displaying RCADS depression subscale scores by session number. The black horizontal line indicates the clinical cut-off score for the RCADS Depression subscale.

There were no notable sources of measurement error when Isla completed measures.

Improvement in family functioning

The scores of both Isla and her mother on the SCORE-15 reduced between the start and end of Phase C. A lower score indicates better family functioning. These are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Isla and her mother’s scores on the SCORE-15

The scores show that Isla perceived there to be a greater improvement in family functioning over the course of Phase C compared with her mother. There were differences in the perceived severity of the problem, degree to which the problem was managed together by family members, and therapy helpfulness as shown in Table 5. Isla perceived the problem as more severe and therapy as more helpful than her mother and she showed the greatest change in belief that the family were managing problems together, going from believing they were hardly managing together at all to managing well together. Over a period of 3 weeks between sessions 16 and 18, Isla and her mother reported having just one argument, whereas previously they had two to three per week on average.

Table 5. Summary of scores related to problem severity, management within the family, and therapy helpfulness

Isla completed the session feedback questionnaire most weeks. The average score for sessions was 19.8 out of 20, suggesting Isla felt listened to, understood the content of sessions, and came away with ideas of what to do to move forwards.

Discussion

This case study describes treatment of an adolescent with PTSD, using both individual TF-CBT and systemic CBT sessions. Following 18 sessions, several improvements were identified in relation to Isla’s goals for treatment, including a reduction in nightmare frequency. The severity of Isla’s PTSD symptoms markedly reduced and dropped below the clinical threshold, and her low mood also improved to below clinical threshold.

Isla’s belief about being to blame for what happened in her traumatic memories reduced from 100% to 0%, and her associated feelings of guilt diminished. Both Isla and her mother indicated that there was an improvement in family functioning, as measured by the SCORE-15, over the course of Phase C alongside a reduction in the frequency of arguments. In the therapy blueprint, Isla wrote that she now believed ‘Mum and dad are trying. They were trying their best when the traumas happened’ and ‘I am not on my own’. In her plans for managing setbacks, Isla wrote ‘If I have an argument with mum, I will remember what I have learnt about mum since having therapy and we will find a time to talk about it’.

Clinical implications

This report has shown that systemic CBT sessions as part of TF-CBT were helpful in promoting changes in key appraisals of traumatic memories which were formulated as having been developed and maintained relationally for Isla. Specific items on the SCORE-15 highlight what Isla felt changed. Initially she reported that ‘when one of us is upset, they get looked after’ described her family ‘not well’, but she rated this as describing her family ‘very well’ at the end of Phase C. She also noted improvements in how much she felt listened to and how problems were dealt with within the family. She reported a reduction in blame, a reduction in nastiness and miserableness, and increase in trust within the family. Her mother noticed similar changes, although to a lesser extent. These changes also provided new evidence for Isla which altered her hotspot appraisals ‘We are not going to be together as a family’ and ‘I will always be alone’.

The sessions provided opportunities for parental attunement and for a new understanding to be developed relating to trauma. The change in appraisals associated with the systemic sessions suggests this strategy may have clinical relevance for treating PTSD in other, similar cases. Clinicians may find it useful to consider a systemic CBT formulation (Dummett, Reference Dummett2006) when formulating with an adolescent who has experienced interpersonal trauma and who holds some beliefs which have developed and been maintained relationally. The use of systemic sessions incorporating interactional vicious cycles within TF-CBT may warrant further research into how these can be applied in other instances of adolescent PTSD arising from interpersonal trauma occurring within the family.

It is known that nightmares are linked to more severe distress and impairment in those who have developed them post-trauma compared with adolescents with idiopathic or no nightmares (Langston et al., Reference Langston, Davis and Swopes2010). Nightmare frequency and poor sleep for adolescents are exacerbated by trauma exposure during developmental periods when these symptoms naturally occur more frequently (Langston, Reference Langston2007). These studies indicate the importance of addressing trauma-related nightmares in adolescent PTSD. This study indicates that nightmare exposure, rescripting and rehearsal can be effective in achieving a reduction in nightmares, but further empirical data are needed.

Ethical considerations

The power held by the therapist in the therapeutic relationship was reflected upon throughout. This was especially important when explaining and conducting nightmare exposure, rescripting and rehearsal, as Isla was anxious about these interventions. She was supported to understand what they would involve and what the advantages and disadvantages might be. This promoted autonomy in her decision-making. This was essential given that the family had historical adverse experiences with CAMHS and this had affected their relationship to help (Reder and Fredman, Reference Reder and Fredman2007).

At the end of therapy, a recent murder case had led to public outcry about violence against women (Topping, Reference Topping2021). This coincided with the anniversary of the sexual assault Isla was victim of. This impacted the end of the intervention, as it was important for time to be reallocated to discussing Isla’s distress due to these events, the response of peers, and ongoing sexism at school. The therapist would have allocated more time to this had further sessions been available to support Isla to manage this setback in her recovery, as Isla noted she had recently experienced a nightmare of the assault. However, Isla’s mum was proactive in supporting Isla with her distress related to this, providing an opportunity for them to strengthen their relationship following the end of therapy.

Limitations

This study would have benefited from demonstrating the level of family functioning at the start of therapy and through the initial phases to robustly support the influence of the Phase C intervention on family functioning. Likewise, it would have benefited from follow-up assessment of PTSD symptoms, mood and family functioning, to demonstrate whether the effects of therapy were sustained. Collection of follow-up data was not possible in this case.

As with all single case studies, it is unclear to what degree the results are generalisable to other cases, and as such more research is required.

Conclusion

This case report has demonstrated through a single-case design that TF-CBT with systemic CBT sessions is a potentially helpful adaptation to the treatment of PTSD and an effective way to treat PTSD which has arisen in the context of interpersonal trauma. It has highlighted the need for further research into the incorporation of such systemic sessions into TF-CBT for adolescents.

Key practice points

-

(1) Practitioners could consider using Dummett’s systemic cognitive behavioural formulation to plan interventions for adolescents with PTSD which has developed as a result of interpersonal trauma.

-

(2) Practitioners could consider the utility of systemic interventions to facilitate change in trauma appraisals which have developed relationally.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X2200054X

Data availability statement

The scores on measures used within this study are provided in the graphs and tables within the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Isla and her family for their trust in us and engagement with the therapeutic process. We would also like to thank the three anonymous peer reviewers for their helpful suggestions on this manuscript. B.V. would like to thank Dr Maria Loades for her support and advice regarding style for an early iteration of this case report.

Author contributions

Bethany O'Brien-Venus: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (lead), Project administration (lead), Visualization (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (equal); Cara Haines: Conceptualization (equal), Project administration (supporting), Supervision (lead), Writing – review & editing (equal).

Financial support

No additional financial support was received for this study beyond the full-time employment of each author within the NHS.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

The Authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the British Psychological Society and the British Association of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies. Ethical approval was not obtained for this case study as the therapeutic work was part of routine clinical work conducted in a CAMHS setting rather than being conducted as part of a research study. Case study consent was obtained in accordance with the requirements for the University of Bath DClinPsy Doctoral Programme which included consent to publish anonymously in a journal. It was verified with the Associate Director of Psychological Therapies within Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust that the Trust’s only requirement was acknowledgement of affiliation and notification of the communications team should the case study be published. Parental and child consent were given to participate in therapy, and for this work to be written up and submitted for publication. The client saw a version of this case study. Names used have been changed to preserve confidentiality.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.