Students of the Transcendental Deduction of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason face an interpretative dilemma.Footnote 1 On the one hand, there are good reasons to think that Kant sought, in this chapter of the Critique, to implicate the faculty of understanding in our so much as having pure intuitions of space and time. This interpretation helps explain Kant’s goal of defending the ‘objective validity’ of the categories and accounts for the way in which Kant invokes our representations of space and time in the course of this defence, especially in the B-Deduction. On the other hand, many passages, directly or indirectly, suggest that Kant saw our pure intuitions of space and time as independent of the operation of the understanding, i.e. of synthesis. I shall borrow labels from James Messina and call these readings the Synthesis Reading and Brute Given Reading of our pure intuitions of space and time, respectively (Messina Reference Messina2014: 7, 8). These readings are, specifically, about our most fundamental, most primitive representations of space and time – what Kant calls our original representations thereof (B40, A32/B48)

For the most part, scholarship on the Transcendental Deduction has not yet recognized the debate between these readings as at an impasse. Commentators tend to take one of the two foregoing sides.Footnote 2 I have come to think that this strategy is a mistake.

In what follows, I offer an account of Kant’s goals in the Transcendental Deduction. I will argue that we must indeed accept that our original representations of space and time are independent of the understanding, as the Brute Given Reading would have it. At the same time, I think we must do better than advocates of this reading have done at appreciating the insights of the Synthesis Reading. Specifically, I attempt to develop an account of the Deduction that allows, despite the concession to the Brute Given Reading, a genuine sense in which instantiations of the categories are given to consciousness.

1. The Synthesis Reading

I begin by motivating the dilemma that I sketch above. There are many reasons to endorse the Synthesis Reading. Plainly by the beginning of the Transcendental Deduction, one of the clearest takeaways is that our original representations of space and time are pure intuitions. Kant writes the following in the A-Deduction:

[The] synthesis of apprehension must … be exercised a priori, i.e., in regard to representations that are not empirical. For without it we could have a priori neither the representations of space nor of time, since these can be generated only through the synthesis of the manifold that sensibility in its original receptivity provides. (A99–100)

It is hard not to read the mention of ‘representations of space [and] of time’ as referring to these pure intuitions.Footnote 3 Likewise, in the culmination of the B-Deduction, Kant claims that the unity of our ‘formal intuition’ of space ‘presupposes a synthesis’.Footnote 4

Such passages, however, are not, to my mind, the strongest reasons for endorsing a Synthesis Reading. The most powerful consideration in its favour derives from reflection on the goals of the Transcendental Deduction.

The Transcendental Deduction is a deduction of Kant’s categories, twelve concepts, including those of causation and substance, unity and negation, whose use is supposed to be ineliminable from our thinking. They are ‘a priori’ concepts, derived not from experience but ultimately from our forms of judgement. More importantly, they are not derivable from experience, at least on previous conceptions of experience, for familiar reasons owed to Kant’s empiricist predecessors.Footnote 5 Neither our five senses nor inner reflection nor some construction from just these sources represent any object of the categories. This fact gives rise to the problematic of the Deduction. If we cannot experience instantiations of the categories, why think that the world that we experience contains any? Such reflections call into question the ‘objective validity’ of the categories. Here is a good expression of Kant’s commitments, even if it occurs after the Deduction itself:

For every concept there is requisite, first, the logical form of a concept (of thinking) in general, and then, second, the possibility of giving it an object to which it is to be related. Without this latter it has no sense, and is entirely empty of content … Now the object cannot be given to a concept otherwise than in intuition, and, even if a pure intuition is possible a priori prior to the object, then even this can acquire its object, thus its objective validity, only through empirical intuition [see also B147], of which it is the mere form. Thus all concepts and with them all principles, however a priori they may be, are nevertheless related to empirical intuitions … Without this they have no objective validity at all, but are rather a mere play …Footnote 6

In the Deduction, we see the same concern about the categories specifically:

[A] difficulty is revealed here that we did not encounter in the field of sensibility, namely how subjective conditions of thinking should have objective validity, i.e., yield conditions of the possibility of all cognition of objects; for appearances can certainly be given in intuition without functions of the understanding. I take, e.g., the concept of cause, which signifies a particular kind of synthesis, in which given something A something entirely different B is posited according to a rule. It is not clear a priori why appearances should contain anything of this sort (one cannot adduce experiences for the proof, for the objective validity of this a priori concept must be able to be demonstrated), and it is therefore a priori doubtful whether such a concept is not perhaps entirely empty and finds no object anywhere among the appearances. For that objects of sensible intuition must accord with the formal conditions of sensibility that lie in the mind a priori is clear from the fact that otherwise they would not be objects for us; but that they must also accord with the conditions that the understanding requires for the synthetic unity of thinking is a conclusion that is not so easily seen. For appearances could after all be so constituted that the understanding would not find them in accord with the conditions of its unity, and everything would then lie in such confusion that, e.g., in the succession of appearances nothing would offer itself that would furnish a rule of synthesis and thus correspond to the concept of cause and effect, so that this concept would therefore be entirely empty, nugatory, and without significance.Footnote 7

Because ‘[i]t is not clear a priori why appearances should contain’ instantiations of the categories, the categories can seem to have the same status that the concepts of fortune and fate (A84/B116–17), and (anachronistically) perhaps those of phlogiston and aether, have: they do not belong among the concepts that one uses to understand the world. This would indeed be some difficulty when the concepts are ones that we cannot help but use!Footnote 8

There is another problem, I think, that the Deduction is meant to address, although it is a problem only once one has taken on board much of Kant’s project. Kant thinks that we can know a priori certain substantive (synthetic) facts about objects of experience. I have in mind here the theses that he defends in the Analytic of Principles, such as that the world contains (permanent) substances of which everything else is a determination and that every event has a cause. As Kant states on several occasions,Footnote 9 his transcendental idealism is central to explaining how we can know these principles a priori. The world that makes these principles true is the world of appearances, not of things in themselves.

Idealisms of perhaps any sort are controversial, but like Berkeley Kant does not want to deny one component of common sense: that the (ideal) world that makes his principles true is a world that is given to us, a world that we confront. There is no threat to this commitment in the Transcendental Aesthetic. In the Aesthetic, Kant contends that we can know certain synthetic a priori truths about space and time only if space and time are transcendentally ideal. But Kant is clear that space and time are given to us; our original representations of them are pure intuitions.Footnote 10 Now compare the project of explaining our a priori knowledge of certain synthetic truths about the world when what would make these principles true is not obviously given (or give-able) to us. Whereas our original representations of space and time are pure intuitions, our original representations of substances, causes, etc. are pure concepts. If there is a real difficulty explaining how we can encounter objects of the categories, then there is also a problem explaining how the theses of the Principles of Pure Understanding can be true.

The concern about the objective validity of the categories, along with the difficulty of explaining how the theses of the Principles might be true, would be overcome by establishing a single result. If Kant could show that in fact the representations of space and time – our pure intuitions of space and time – themselves require a structuring that ultimately derives from the understanding, then it would turn out that the spatiotemporal structure imposed by our pure intuitions of space and time on all objects of possible experience would also include this structure from the understanding.Footnote 11 This structure would be categorial: it would make objects present themselves as substantival, causal, etc.Footnote 12 The categories would be just as objectively valid as our concepts of space and time. And we would have a general account of how Kant’s arguments in the Analytic of Principles are supposed to yield truths about the world that we experience. For the details, we would have to look at Kant’s arguments in the Principles of Pure Understanding.Footnote 13

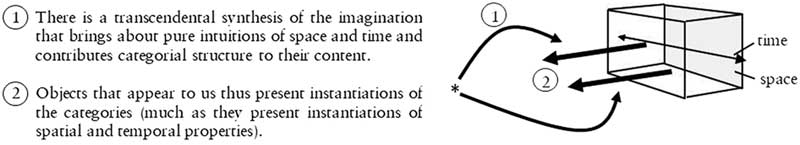

The foregoing interpretation supports the Synthesis Reading, for the structure that the understanding adds to our pure intuitions of space and time would be by way of a kind of synthesis. In the B-Deduction, Kant’s argument turns on the represented unity of space and time. This unity, he seems to argue, can exist only as the output of a pre-judgmental ‘figurative synthesis’ (B151–2).Footnote 14 Figurative synthesis, because it is an activity of the understanding, despite not being an act of judgement, must apply categorial structure to the manifold of intuition (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Synthesis on the Synthesis Reading

This reading constitutes, as Béatrice Longuenesse says of her own analysis, a ‘rereading’ of the doctrines of the Transcendental Aesthetic.Footnote 15 Kant rescinds nothing from the Aesthetic; but he does argue that features of our pure intuitions of space and time, such as their unity, require a deeper explanation that appeals to the operations of the understanding.

I endorse virtually all of the foregoing. But I take as definitive of the Synthesis Reading that the representations of space and time that require an imaginative synthesis are our original representations of space and time which, Kant argues in the Transcendental Aesthetic, are pure intuitions. As I explain below, there are good grounds to deny this. The challenge will be explaining how to retain the insights of the Synthesis Reading.

2. The Brute Given Reading

What concerns speak against a Synthesis Reading? Here I shall note several.

-

(1) At least one passage of which I am aware indicates that we can have an intuition without synthesis, and the form of this intuition is ‘nothing but receptivity’ (B129). Our original representations of space and time make possible our other (empirical) intuitions. So they would seem to be independent of synthesis.

-

(2) An obvious implication of the Synthesis Reading is that non-human animals (and perhaps very young children), whom Kant would not credit with an understanding,Footnote 16 could not intuit space or time.Footnote 17 Considering also that Kant claims that the representation of space is a precondition for the representation of spaces,Footnote 18 it would seem that such animals have no representation of locations or areas in space at all (mutatis mutandis for time/times). We can add to this concern about the philosophical implication of this reading that there are passages in Kant’s corpus that prima facie suggest that non-human animals possess at least rudimentary representations of spaces and times. For example, in a well-known passage from the Jäsche Logic, Kant holds that non-human animals are ‘acquainted with [kennen]’ objects (Log, 9: 65, emphasis removed). If this is intuition of objects, then there is some pressure to credit animals with pure intuitions of space and time since, for humans, it is a precondition on empirical intuitions that we represent objects of empirical intuitions in space and time (e.g. A26/B42). Why would animals be different?

-

(3) Kant claims that our original representation of space is a precondition for the representation of particular spaces (mutatis mutandis for time/times). Thus, the representations of spaces cannot be inputs into a combinatorial process, which according to Kant must proceed part to wholeFootnote 19 and which yields the pure intuition of space as an output: our original representation of space could no longer function as a precondition.Footnote 20

-

(4) Kant claims that our original representations of space and time represent an infinitude.Footnote 21 But our finite minds cannot synthesize infinitely many representations of spaces or times.Footnote 22

-

(5) I have proposed that the syntheses that Kant defends in the second half of the B-Deduction are elaborated on and defended in greater detail in the Principles sections. But the Axioms of Intuition and Anticipations of Perception are not plausibly arguments that articulate syntheses necessary for the representation, let alone the pure intuition, of space or time. Their focus is on the preconditions of (determinate) empirical intuitions.

-

(6) And even if they did plausibly articulate syntheses necessary for the representations of space and time, there is the further difficulty that the synthesis described in the Axioms explicitly proceeds part to whole – which would exacerbate the difficulty of (3).Footnote 23

-

(7) The syntheses described in the Principles seem to presuppose some representation of space and time (e.g. the successiveness of one’s perceptions), so these syntheses cannot be preconditions for these representations of space and time.

All together these objections place a considerable explanatory burden on the Synthesis Reading, one that I am not convinced that it can shoulder. Still, can the Brute Given Reading be squared with the argument of the Transcendental Deduction?

I have in mind, in particular, two sets of passages to which any plausible reading of the Transcendental Deduction must do justice. The first set of passages is precisely the set of passages to which I appealed in section 1, according to which the threat facing the categories is that we cannot be given instantiations of them; that these instantiations are not contained among appearances. The second set of passages are those of §26 of the B-Deduction that explicitly appeal to the unity of space and time to leverage Kant’s defence of the categories’ objective validity. I have already described how the Synthesis Reading neatly incorporates these passages. How does the Brute Given Reading do so?

Not easily, in my opinion. Many advocates of the Brute Given Reading see Kant’s appeal to the unity of space and time as grounds not for an argument according to which our original representations of space and time must be a product of synthesis (as on the Synthesis Reading) but rather as grounds for an argument according to which some taking or grasping of space and time, or of a space or a time, is a product of synthesis.Footnote 24 And a prima facie difficulty for such a proposal is its inability to make sense of Kant’s concern to establish that we are given, that appearances contain, instantiations of the categories. Kant does not merely want to establish that we must conceive of the world (or ‘grasp’ the world) as containing categorial features; he wants to show that the world (admittedly an ideal world) really does contain them.Footnote 25

3. An Initial Proposal

It seems that we need a reading that makes sense of Kant’s endgame of incorporating categorial features into appearances by way of a transcendental synthesis of the imagination while accepting that our original representations of space and time are independent of the understanding and the imagination. It would be congenial to the Brute Given Reading if an F could appear to me simply because I apply the concept of an F. This would encourage thinking that Kant’s goal is just to show that we must apply the categories – thereby, without further ado, categorial features would appear to us. But it is not plausible that an F appears to me simply because I apply the concept of an F. The Synthesis Reading offers an elegant way of explaining how categorial features appear to us: a synthesis of the imagination adds structure to the manifold of intuition at the same lower ‘level’ as our pure forms of intuition. But the reading is too much at variance with Kant’s texts. What we need is a more liberal conception of both appearances and givenness. It must allow that we can be genuinely given categorial features even if they are added to experience at a higher ‘level’, though not as high as the level of concept-application.

Lanier Anderson has a helpful analogy of a map layered over by transparency pages that contain different kinds of topographical information, and I will appropriate the analogy here (Anderson Reference Anderson2001: 288). Up to now, I have worked on the assumption that there is, so to speak, but one map and one transparency page over it. The map is the spatiotemporal manifold of intuition; the transparency page is the ‘higher’ level of applied concepts. On the Synthesis Reading, a transcendental synthesis of the imagination structures our pure intuitions of space and time – it affects, as it were, the map itself. Brute Given Readings tend to see the work available for synthesis at the level of concepts, affecting, as it were, the transparency page, not the map.

I want to propose, to expand on this analogy, that there must be a second transparency page in between the one at the level of concepts and the map below, and it is at this level that figurative synthesis works. We need not deny that empirical objects, space, and time are given to us independently of synthesis. This is the truth of the Brute Given Reading. But we do need the synthesis of the imagination to operate a level ‘lower’ than concepts to explain how one is genuinely given instantiations of the categories (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Synthesis on the Initial Proposal

This reading avoids all of the objections that I considered against the Synthesis Reading. (1) It allows that we have representations of space and time independently of synthesis, including (5 and 7 above) those described in the Principles sections.Footnote 26 (2) It allows that non-human animals can possess pure intuitions of space and time, as well as empirical intuitions of objects. (3) It does not violate Kant’s insistence that the representations of space and time are preconditions for the representation of spaces and times, respectively. (4) It allows that the representation of the infinitude of space and time (not well captured in my diagrams, admittedly) is a brute feature of our original representations of space and time. And (responding to 6 above) it does not put the Axioms section into conflict with Kant’s view that our representations of space and time are preconditions of our representations of their parts.

4. B160–1 and B160–1n.

But can this reading do justice to the argument of the Transcendental Deduction in the way that the Synthesis Reading can? The Synthesis Reading had a straightforward explanation of Kant’s argument at B160–1. At this point in the Critique, it is a datum that we possess pure intuitions of space and time. These are intuitions of single particulars: they possess a kind of ‘unity’. Kant argues that for these intuitions to possess this unity, they must be products of a transcendental synthesis of the imagination.

My analysis seems to deny this. With the Brute Given Reading, I claim that our original representations of space and time are independent of synthesis. But then how does Kant’s argument work? What representations of space and time are at issue at B160–1? And in what sense do they possess a kind of ‘unity’?

Kant draws two distinctions at B160–1 and at B160–1n., and these have been sources of extended controversy. The first is between the forms of intuition and our intuitions of space and time – a curious distinction, considering that in the Aesthetic Kant seems to identify these (A20/B34–5). The second distinction, which seems another way of stating the first, is between the form of intuition and a formal intuition. He says that the ‘form of intuition merely gives the manifold, but the formal intuition gives unity of the representation’ (B160n.). He then adds: ‘In the Aesthetic I ascribed this unity merely to sensibility, only in order to note that it precedes all concepts, though to be sure it presupposes a synthesis …’ (B160–1n.).

The latter passage is grist for the mill of an advocate of the Synthesis Reading because where Kant actually talks about the unity of (the representation of) space in the Aesthetic is in his argument that our original representation of space is an intuition, not a concept (A24–5/B39–40). So his point can seem to be that the original, pure intuition of space that is the subject of the Metaphysical Exposition is the formal intuition and that it and its unity are a product of synthesis.

I want to suggest another way of understanding Kant’s claims. Let us grant what advocates of the Brute Given Reading insist on: our original representations of space and time are independent of synthesis, as are all of the features of our original representations of space and time articulated in the Metaphysical Expositions. This means, for instance, that the representation of a single space as ‘an infinite given magnitude’ (A25/B39) is no consequence of synthesis.

I look at the earth. It appears as part of a single space (as we might put it, Space). Now I look at the moon. It also appears as part of a single space (Space). These are the sort of facts to which Kant appeals in the Transcendental Aesthetic. But it does not follow that it is a matter of mere intuition that it appears to me that the space of which the earth was a part at t 1 appears to be the same space of which the moon is a part at t 2. I propose that it is precisely the role of the transcendental synthesis of the imagination to account for this appearance: we represent in experience but one space throughout time, not just at any given moment. My representation of this one space throughout time is the (synthesized) formal intuition of space.

Similarly, any given moment of time appears to be after and before an indefinitely (perhaps infinitely) long stretch of moments (A31–2/B47–8). This is a matter of mere intuition, and as far as the unity of time goes, it is all that Kant’s argument requires in the Metaphysical Exposition. It does not follow, however, that at t 1 the time of which this moment is a part (or a limit) must appear to be part of the same time of which t 2 is a part at t 2. My suggestion is that we represent but one time throughout time – all of these moments, at those distinct moments, as part of the same time – as a result of a transcendental synthesis of the imagination. The resulting representation is the formal intuition of time. The objects of our formal intuitions are space and time qua ‘enduring’, determinate particulars.Footnote 27

Here I quote the second half of the note at B160–1, since on its face it recommends the Synthesis Reading, and it is important that my account be able to accommodate it:

In the Aesthetic I ascribed [the unity of the formal intuition] merely to sensibility, only in order to note that it precedes all concepts, though to be sure it presupposes a synthesis, which does not belong to the senses but through which all concepts of space and time first become possible. For since through it (as the understanding determines the sensibility) space or time are first given as intuitions, the unity of this a priori intuition belongs to space and time, and not to the concept of the understanding (§24).

Kant is here acknowledging an infelicity in his presentation in the Aesthetic. On the Synthesis Reading, he is claiming that, although he did not say as much in the Aesthetic, our original representations of space and time really do require a synthesis. But I would like to suggest that he is acknowledging that in the Aesthetic he conflated (probably so as not to complicate further an already complicated discussion) what he is now distinguishing as the form of intuition and a formal intuition. Because of this conflation, we may have thought that the original representation of space was the formal intuition of space and that the representation of space over time is a matter of mere intuition. We should read Kant’s claim that he ‘ascribed’ the unity of the formal intuition merely to sensibility as the claim that he ‘gave the impression’ that this unity comes from sensibility.Footnote 28

So the culmination of Kant’s argument in the B-Deduction turns not on our original, pure intuitions (= forms of intuition) of space and time from the Aesthetic. It turns rather on our ‘formal’ intuitions of space and time, which depict one space and one time throughout time, not merely at any given moment (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Synthesis on the Considered Proposal

I have now offered an interpretation of Kant’s distinction between forms of intuition and formal intuitions (B160–1n.). There is great diversity of opinion about how to understand it. I lack the space to offer a thorough review of the literature, but I would like, in admittedly summary fashion, to note what advantages I think my analysis has over those espoused in Synthesis and Brute Given Readings.Footnote 29 It will help to have all of B160–1n. before us:

Space, represented as object (as is really required in geometry), contains more than the mere form of intuition, namely the comprehension [Zusammenfassung] of the manifold given in accordance with the form of sensibility in an intuitive representation, so that the form of intuition merely gives the manifold, but the formal intuition gives unity of the representation. In the Aesthetic I ascribed this unity merely to sensibility, only in order to note that it precedes all concepts, though to be sure it presupposes a synthesis, which does not belong to the senses but through which all concepts of space and time first become possible. For since through it (as the understanding determines the sensibility) space or time are first given as intuitions, the unity of this a priori intuition belongs to space and time, and not to the concept of the understanding (§24).

To the best of my knowledge, all parties take formal intuitions to be, in some sense, more processed or ‘higher’ representations.

I begin with Synthesis Readings. They have in common identifying formal intuitions with our original representations of space and time.Footnote 30 So the basic difficulty that they face is explaining how the form of intuition could be more primitive and less processed than these. Wayne Waxman claims that forms of intuition are ‘the innate nonrepresentational faculty ground of space and time, the peculiar constitution of human receptivity that determines imagination to synthesize apprehended perceptions in conformity with the forms of synthesis space and time’ (Waxman Reference Waxman1991: 95; see also 80 and 90).Footnote 31 Longuenesse characterizes the form of intuition at B160–1n. as a ‘merely potential form’ (Longuenesse Reference Longuenesse1998: 221; emphasis removed). With an act of figurative synthesis, it is actualized into the formal intuition.

But consider some of Kant’s remarks about the form of intuition at B160–1n. He claims that the form of intuition ‘gives the manifold’, and it also seems that the formal intuition (‘Space, represented as object’) is in part constituted by our form of intuition. The formal intuition ‘contains more than the mere form of intuition’ (my emphasis) – the implication being that it contains at least this – ‘namely the comprehension of the manifold given in accordance with the form of sensibility’. The picture is thus that the form of intuition presents the world as spatial, and the representation of a spatial world is further worked over to yield the formal intuition of space.

If the form of intuition is not itself (actually) representational, then it seems that at most one could say that it somehow constrains the content of the formal intuition. But it is unclear what it would be for the formal intuition to ‘contain’ this nonrepresentational ground (Waxman) or potential (Longuenesse).Footnote 32 It is also unclear what the relationship would be between the form of intuition and the synthesis that yields or actualizes the formal intuition of space. Is the form of intuition itself subject to a synthesis? But Kant bills synthesis as a synthesis of representations, not of nonrepresentational grounds or potentials (A77/B103). Is there a synthesis only of empirical representations? If so, it seems mysterious how the form of intuition plays any role at all in the production of the formal intuition.Footnote 33

Brute Given Readings identify our original representations of space and time with the forms of intuition. One way that they distinguish themselves from each other is in how they understand the formal intuition. Focusing for now on space rather than time, some maintain that the formal intuition is a ‘synthesized’ intuition of a space or of a spatial figure.Footnote 34 Others maintain that it is a synthesized intuition of space itself.Footnote 35

It matters how this synthesis is understood. Many Brute Given Readings hold that the synthesis in one way or another involves the application of concepts. A longstanding objection to this view is that Kant claims that the unity of the formal intuition ‘precedes all concepts’ (B160–1n.). I will not press the concern here; most contemporary advocates of the Brute Given Reading have accounts that attempt to circumvent it. I will note that neither the Synthesis Readings that I have considered, nor my own analysis, because of each’s embrace of a pre-discursive synthesis, is even prima facie subject to the worry.

More fundamentally, it seems fair to say that Brute Given Readings hold that the unity of a formal intuition requires some ‘taking’ or ‘grasping’ of what is given. There is the wholly sensible unity of the form of intuition; the unity at issue in §26 of the B-Deduction – the unity of the formal intuition – is the distinct unity of the grasping. This analysis is explicit, for example, in recent work by Colin McLear and by Christian Onof and Dennis Schulting. For McLear, the synthesis at issue in §26 allows one to intuit space as an object; for Onof and Schulting, it allows one to grasp the unity that the form of intuition otherwise has.Footnote 36

Now I think that we must acknowledge that the relevant synthesis is a kind of ‘taking together’ (Zusammenfassung) of a manifold of intuition (B160n.). What matters crucially, however, is whether this taking, or its product, is also given to consciousness. I attempted to establish an affirmative answer as a desideratum in section 1, but it is also demanded by the text of §26 itself. Kant writes that ‘the formal intuition gives unity of the representation [die formale Anschauung … Einheit der Vorstellung giebt]’. He claims that ‘through [this synthesis] (as the understanding determines the sensibility) space or time are first given as intuitions [der Raum oder die Zeit als Anschauungen zuerst gegeben werden]’. His point seems to be that it is through synthesis that space and time (as, I propose, reidentifiable particulars) are first truly given at all – i.e. our intuitions of them require this synthesis. A ‘combination … is already given [gegeben] a priori’ along with our formal intuitions, Kant writes (B161).Footnote 37 As he puts it in the A-Deduction, without the requisite synthesis, the ‘necessary unity of consciousness would not be encountered [angetroffen] in the manifold perceptions’ (A112, my emphasis).

Synthesis Readings can account for the given unity of the formal intuition, and I have constructed my own analysis around making sense of it too. The Brute Given Readings of which I am aware, however, do not seem designed to do so. At a minimum, their rhetoric suggests that ‘taking’ or ‘grasping’ is a relatively far-downstream event – at the level of the upper transparency page, to return to Anderson’s analogy. To represent space and time ‘as objects’, as McLear describes it, or to grasp the sensible unity represented by the form of intuition, as Onof and Schulting might put it, sounds like it could involve merely the application of the appropriate concepts.Footnote 38 While in fact both McLear and Onof and Schulting hold that this grasping includes a synthesis of the imagination,Footnote 39 I see no interest on their part in making the unity of the formal intuition itself something given.

If they did, then we reach the main outlines of my own reading. What might remain in dispute are the details: for example, the difference between what is given in the form of intuition and what is given in the formal intuition.Footnote 40

5. Two Objections Reconsidered

I close by reconsidering two objections that I presented against the Synthesis Reading. The first is objection (5) from section 2. I have encouraged the view that the syntheses abstractly described at the end of the Transcendental Deduction are precisely the syntheses that Kant defends in greater detail in the Principles sections. It seems implausible, however, that the Axioms of Intuition or the Anticipations of Perception (sections corresponding to the ‘mathematical’ categories) articulate conditions on our so much as having pure intuitions of space or time. My account may allow that we can have pure intuitions of space and time (forms of intuition) independently of synthesis, but it may seem equally implausible that the Axioms or the Anticipations articulate conditions on our having ‘formal’ intuitions of space or time. Rather, they articulate conditions on our having determinate empirical intuitions.

But is it implausible? What is obvious is that the Axioms and Anticipations do not directly articulate conditions on our having representations of space or time. But I would like to propose, admittedly somewhat speculatively, that we can and should read these sections as indirectly articulating conditions on our having formal intuitions of space and time.

I cannot defend in detail the admittedly contentious view that the Analogies of Experience articulate the conditions on our possessing formal intuitions of space and time. But I hope for the present that such a view seems at least worthy of consideration. In the First Analogy, Kant does seem to make the experience of substance a precondition for a representation of time (see especially A182–3/B224–6). Since we cannot perceive time ‘by itself’ (B225), there must be a surrogate in the content of our experiences that embodies the persistence of time, namely, substance.Footnote 41 We can read the Second Analogy as articulating a further condition on a representation of time: to experience time as an enduring particular, its moments must be connected together serially by the relation of cause and effect. With regard to the Third Analogy, I am moved by Margaret Morrison’s reading according to which the representation of substances as in thoroughgoing interaction makes possible the representation of a single space.Footnote 42 I would simply qualify that this single space is one space (Space) over time.

But it is hard to see how these conditions for the formal intuitions of space and time could be in place absent empirical content – specifically, empirical intuitions of objects. In the First Analogy, there must be empirical matter given in intuition that is interpreted either as (permanent) substance or as a determination thereof. Regarding the Second Analogy, there is no causal relationship between one location of pure space-time and a later location of pure space-time. Nor, now considering the Third Analogy, can there be interactions between two points in pure space-time. Thus, I would agree with those who have dismissed the proposal that syntheses operative in making experience possible work on pure manifolds of space or time.Footnote 43 Our formal intuitions of space and time require the determinate empirical intuitions the conditions for which Kant articulates in the Axioms of Intuition and the Anticipations of Perception. Consequently, we need not see a tension between Kant’s commitment, in the Deduction, to synthesis in accord with the mathematical categories making possible our formal intuitions of space and time and Kant’s arguments in the Axioms and the Anticipations.

The second objection that may seem to apply to my reading, which may also be encouraged by my response to the foregoing, is (7) from section 2. It derives from details of the Analogies and the Axioms. Kant’s arguments in these sections seem to take some representation of space and time as a presupposition for the syntheses for which he advocates. And it can seem that these representations must be (by my lights) formal intuitions. Here I shall focus on the Axioms of Intuition, since I think that this section produces the thornier version of the difficulty.

Kant opens the Axioms as follows:

All appearances contain, as regards their form, an intuition in space and time, which grounds all of them a priori. They cannot be apprehended, therefore, i.e., taken up into empirical consciousness, except through the synthesis of the manifold through which the representations of a determinate space or time are generated … (B202)

Kant’s example of generating a determinate space and time – or perhaps an object in a determinate space and time – includes the drawing of a line (A162/B203). Since this takes place over time, surely Kant takes for granted that what is making this possible are intuitions of space and time understood as enduring particulars – i.e. formal intuitions. Otherwise, there could be no sense in talking about a single line generated over time.

And now there seems to be a problem. If the Axioms help articulate how it is that we have determinate empirical intuitions, which, I have urged, are preconditions for the syntheses depicted in the Analogies that make possible our formal intuitions of space and time, but the Axioms themselves take for granted formal intuitions of space and time, then we seem caught in a circle.

This would indeed be a problem if Kant were offering a developmental psychology, explaining the temporal order in which we come by the representations that make experience possible. But here I would like to borrow an insight from Wilfrid Sellars, who claims that we cannot have the concept green without having a host of other concepts too. We are credited with concepts in bunches, he thinks, not piecemeal (Sellars Reference Sellars2003: 44). Maybe it is hard to say when to credit a child with the concept green, but when we may, we are likewise entitled to credit her with many other concepts besides. Similarly, I would like to suggest that it is a mistake to look at the above circle as one into which we must break. Rather, on the Kantian picture we have formal intuitions of space and time and determinate empirical intuitions together or not at all. There is no first. Each is a condition of the other.

6. Conclusion

In this article I have tried to work out a way of understanding the relationship between the unity of (our representations of) space and time and synthesis in Kant’s Critique that can accommodate what motivates the Brute Given and Synthesis Readings. Clearly the analysis, if correct, has implications for our understanding of the Transcendental Deduction. It also has implications for our understanding of the Analytic of Principles, which I have only begun to address here. I hope to pursue those implications in future work.Footnote 44