Introduction

Cholesteatoma is characterised by a cyst-like, expansile lesion of the temporal bone, lined with stratified squamous epithelium that contains desquamated keratin.Reference Dornelles, Costa, Meurer and Schweiger1 Eustachian tube dysfunction with negative pressure of the middle ear is the most likely mechanism for cholesteatoma development and recurrence after surgery.Reference Alves, Pereira, Ribeiro and Fregnan2–Reference Schuknecht10

Studies have also suggested that there is abnormal proliferation of epithelium in cholesteatoma patients. Some reseachers,Reference Michaels11–Reference Jove, Vassalli, Raslan and Applebaum23 including Bujia et al.,Reference Bujia, Sudhoff, Holly, Hildmann and Kastenbauer20 found that cholesteatoma epithelium proliferates at a higher rate than normal epidermis. Previous studies on cholesteatoma formationReference Huang, Yan and Huang24–Reference Hulka and McElveen33 have indicated the possible involvement of: cytokeratins (e.g. Weiss et al.Reference Weiss, Eichner and Sun25), epidermal growth factor (e.g. Kojima et al.,Reference Kojima, Shiwa, Kamide and Moriyama26 Li et al.Reference Li, Jiang and Wang27 and Barbara et al.Reference Barbara, Raffa, Murè, Manni, Ronchetti and Monini28) and its receptor, and keratinocyte growth factor (e.g. Kojima et al.,Reference Kojima, Matsuhisa, Shiwa, Kamide, Nakamura and Ohno29 and Yamamoto-Fukuda et al.Reference Yammamoto-Fukuda, Aoki, Hishikawa, Kobayashi, Takahashi and Koji30) and its receptor.

Most previous studies that assessed patients after canal wall down mastoidectomy focused on cholesteatoma recurrence rates, causes of recurrence,Reference Gantz, Wilkinson and Hansen34–Reference Segalla, Nakao, Anjos and Penido38 hearing outcomes (pre- and post-operatively)Reference Vartianinen and Nuutinen39,Reference Harkness, Brown, Fowler, Grant, Ryan and Topham40 and surgery-related complications.Reference Hirsch, Kamerer and Doshi17–Reference Proops, Hawak and Parkinson22,Reference Abramson and Huang35

Materials and methods

This cross-sectional study involved the clinical observation and evaluation of middle-ear aeration in patients who had undergone canal wall down mastoidectomy for cholesteatoma and other pathologies at least six months previously at a tertiary centre (KPJ Tawakkal Specialist Hospital or University Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre).

We identified the post-operative canal wall down mastoidectomy patients with dry, non-discharging ears on follow up. Patients who presented with recurrence, discharge or granulation on follow up were excluded.

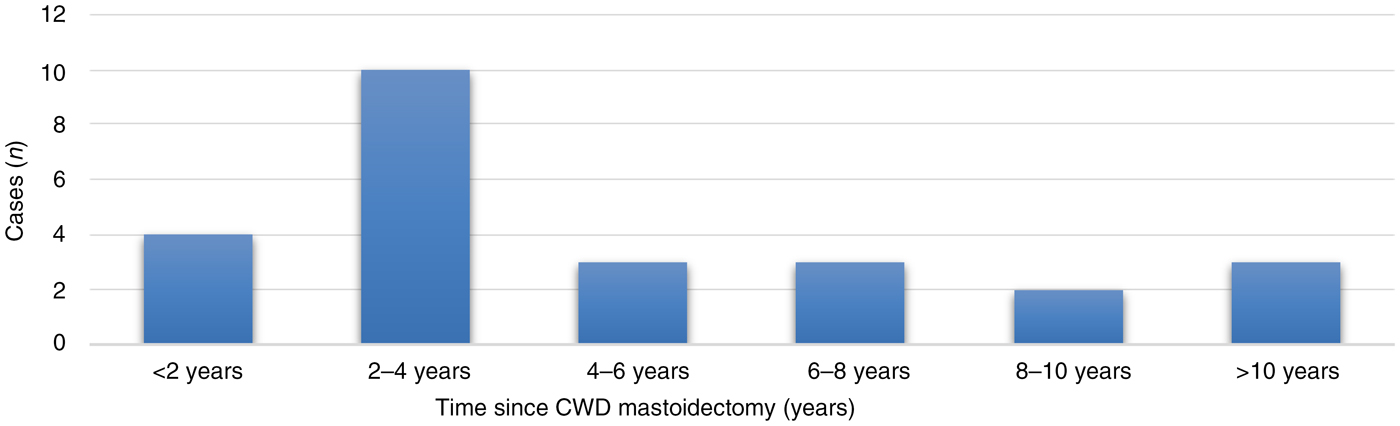

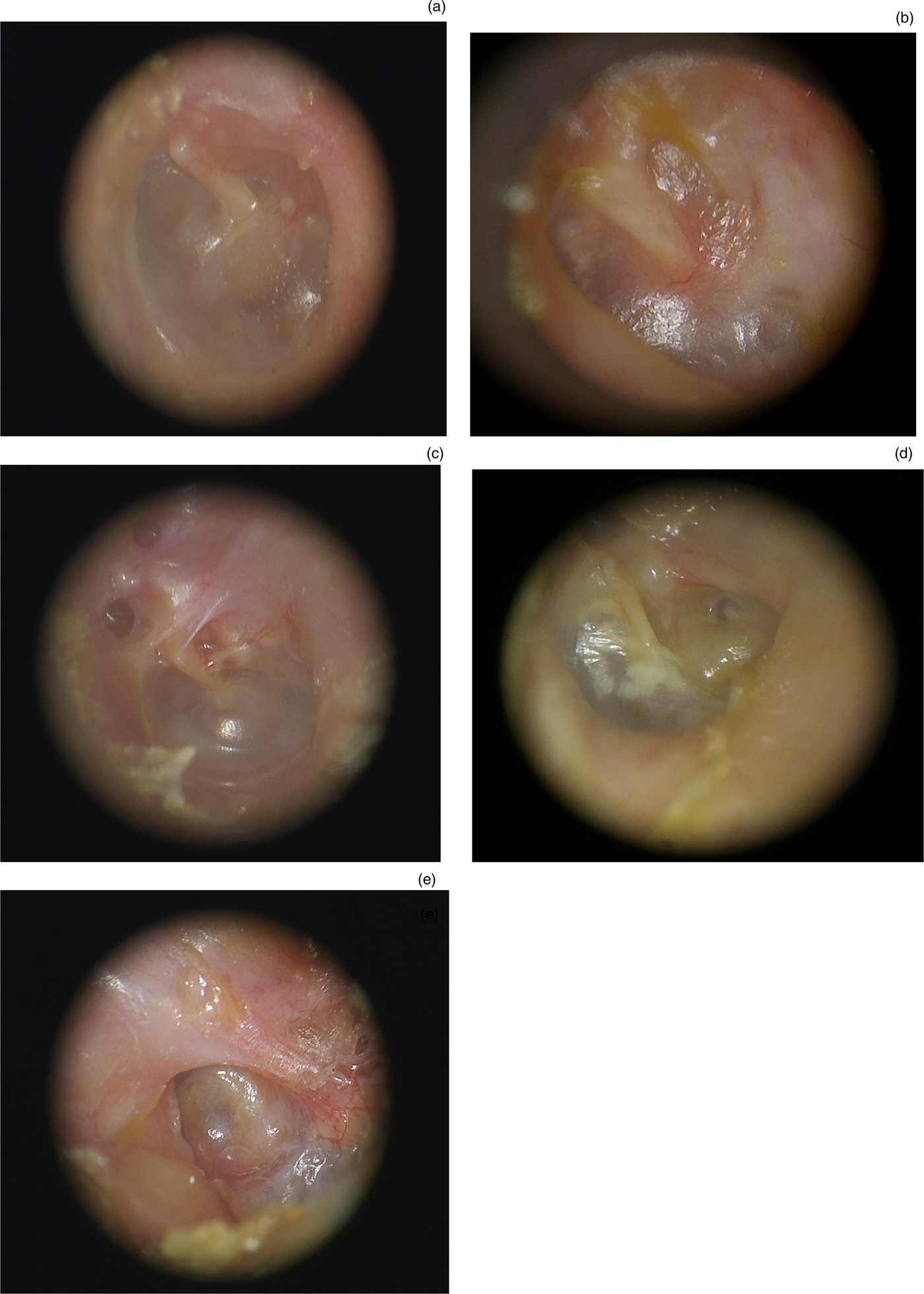

Otoendoscopic findings were categorised according to Sade's modified (1979) classification for pars tensa retractions of the neo-tympanic membrane,Reference Sade and Sade41 and Tos and Poulsen's modified (1980) classification for attic retractions,Reference Tos and Poulsen42 as shown in Figures 1 and 2 respectively.

Fig. 1. Representative clinical photographs showing the status of the neo-tympanic membrane following canal wall down mastoidectomy (modified Sade classificationReference Sade and Sade41): (a) normal (no retraction); (b) mild (dimple or slight retraction); (c) moderate (deeper retraction not reaching promontory); (d) severe (localised retraction reaching promontory); and (e) very severe (complete retraction to the promontory (atelectasis)).

Fig. 2. Representative clinical photographs showing the status of the exteriorised attic following canal wall down mastoidectomy (modified Tos and Poulsen classificationReference Tos and Poulsen42): (a) normal (no retraction); (b) mild (single shallow pocket); (c) moderate (multiple shallow pockets); (d) severe (single deep pocket); and (e) very severe (multiple deep pockets).

Results

Demographics

A total of 24 patients were recruited; 1 patient had undergone bilateral canal wall down mastoidectomy, hence the study included 25 ears. The age of the sample population ranged from 7 to 69 years (mean age of 39 years). Nine patients (37.5 per cent) were female and 15 (62.5 per cent) were male. The majority of the study population were Malaysian (66.6 per cent); the remainder were Chinese (16.6 per cent), Indian (13.2 per cent) or other (0.4 per cent).

Data for 14 ears (56 per cent) were collected from KPJ Tawakkal Specialist Hospital during the period from 1st May 2014 to 31st November 2014. Data for 11 ears (44 per cent) were collected from the Otorhinolaryngology Clinic at the University Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre during the period from 1st December 2014 to 31st May 2015.

There was an almost equal distribution of left and right ears. The left ear was affected in 52 per cent of cases, and the right ear was implicated in 48 per cent.

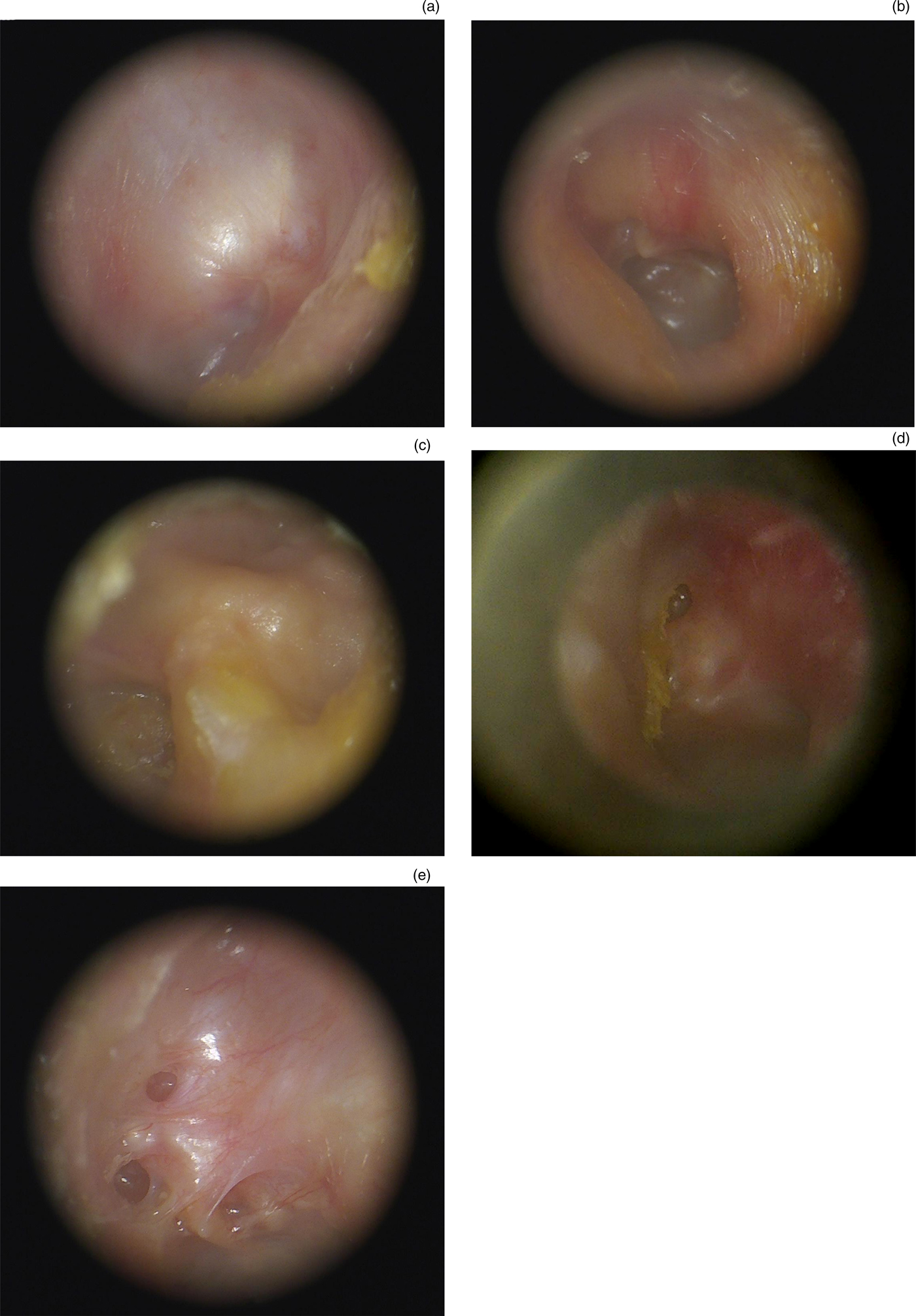

Of the 25 ears, canal wall down mastoidectomy was performed for: cholesteatoma in 22 ears (88 per cent), chronic mastoiditis in 2 ears, and mastoid abscess secondary to recurrent otitis media in 1 ear. The time since canal wall down mastoidectomy amongst our study population is shown in Figure 3. Most of the patients had undergone the canal wall down procedure between two and four years previously (40 per cent).

Fig. 3. Time since canal wall down (CWD) mastoidectomy.

Neo-tympanic membrane status

The status of the neo-tympanic membrane after canal wall down mastoidectomy, for the 25 ears in this study, is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Status of neo-tympanic membrane post canal wall down mastoidectomy in this study

The data show that 92 per cent of ears had some degree of neo-tympanic membrane retraction (ranging from mild to very severe). *Total n = 25

Exteriorised attic status

Table 2 shows the status of the exteriorised attic following canal wall down mastoidectomy for the 25 ears in this study.

Table 2. Status of exteriorised attic post canal wall down mastoidectomy in this study

*Total n = 25

Middle-ear aeration

As aeration of the middle ear following canal wall down mastoidectomy is dependent on both the neo-tympanic membrane and exteriorised attic, we combined the findings for both the neo-tympanic membrane and the exteriorised attic. Thus, we devised a new means of classifying middle-ear aeration post canal wall down mastoidectomy. Our proposed classification is shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Ezulia et al. classification of middle-ear aeration post canal wall down mastoidectomy

The classification of middle-ear aeration post canal wall down mastoidectomy for the 25 ears in this study is shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Classification of middle-ear aeration post canal wall down mastoidectomy in this study

*Total n = 25

Discussion

Several classifications of tympanic membrane retraction exist, more of which concern the pars tensa than the pars flaccida. However, there has been no previous attempt to grade the status of the neo-tympanic membrane after canal wall down mastoidectomy. The traditional Sade classification demonstrates the progression of retraction in the non-operated ear,Reference Sade and Sade41 and can be used as a basis for a new classification.

In our attempt to arrive at a reasonable grading for the status of the neo-tympanic membrane after canal wall down mastoidectomy, based on our review of 25 ears, we used Sade's classification,Reference Sade and Sade41 which has been accepted universally and is often used to grade otitis media effusion. Sade's classification was used as a basis for our grading because the (neo)tympanic membrane and middle-ear cleft may still be present post canal wall down mastoidectomy. Presumably, there was still aeration of the middle ear following canal wall down mastoidectomy. However, in the neo-tympanic membrane, the pars tensa was stiffer, possibly because of scarring. The volume of the middle ear was also smaller. The ossicles might be eroded or abnormal.

We used retraction pockets as the basis for our grading because the majority of the epithelial cover of the exteriorised attic developed retraction. Initially, we suspected that this factor might be related to pre-operative findings, regardless of whether the ossicles were present, absent or malformed intra-operatively. We assumed that the post-operative exteriorised attic might not appear as retraction pockets in patients with an absent or eroded head of malleus and body of incus. We suspected that patients who still had remnants of either the malleus or body of incus would show retraction pockets. However, there was no correlation between the intra-operative reports and post-operative findings. In our study, some patients who had remnants of the head of malleus and short process of the incus intra-operatively still developed a non-retracted exteriorised attic post-operatively, and vice versa. Thus, the presence or absence of ossicles might not be a strong determining factor for the degree of exteriorised attic retraction.

Theoretically, the desquamated keratin debris forms cholesteatoma at the retraction site. Nevertheless, in our study, some of the patients developed the debris faster than others. It was assumed that retractions of the neo-tympanic membrane and exteriorised attic were severe if middle-ear aeration was poorer, requiring more frequent ear toileting to clear the debris at the retraction site. However, no association was found between the grade of middle-ear aeration and the frequency of ear toileting in our sample.

Eustachian tube dysfunction and poor middle-ear aeration were persistent after canal wall down mastoidectomy, as evidenced by all of our 25 ears. In this study, there was no new cholesteatoma development. This may support the theory that retraction pockets and negative pressure in the middle ear are not the only determinants of cholesteatoma development. Cytokeratins and keratinocyte growth factors have a possible role in cholesteatoma development.Reference de Zinis, Tonni and Barezzani18–Reference Bujia, Sudhoff, Holly, Hildmann and Kastenbauer20

• Neo-tympanic membrane and exteriorised attic retraction was significant in patients with a longer duration since canal wall down mastoidectomy

• Eustachian tube dysfunction leading to negative middle-ear aeration persisted after a canal wall down procedure

• However, these patients never fully developed cholesteatoma despite persistent retraction

• The findings suggest that retraction pockets are not the only factor determining cholesteatoma formation

Our classification of middle-ear aeration was based on clinical assessment. A combination of clinical assessment and objective measurement of middle-ear pressure would allow more accurate determination and classification of middle-ear aeration. Ikeda et al. used computed tomography (CT) scanning to measure the middle-ear aeration in a reconstructed middle-ear cavity post canal wall down mastoidectomy.Reference Ikeda, Yoshida, Ikui and Shigihara43 The CT scan evaluation was conducted approximately one year post-operatively. The state of re-aeration of the reconstructed middle-ear cavity was classified as: ‘re-aerated’, in cases where the CT scan showed obvious aeration, or ‘non-aerated’, in cases where no aerated space could be identified. In 73 of the 103 ears, re-aeration in the reconstructed mastoid cavity, epitympanum and middle ear could be evaluated post-operatively. In their study, the rate of re-aeration in the middle ear (82.4 per cent) was better than that in the epitympanum and mastoid cavity (63.5 per cent and 36.5 per cent respectively). Our study was comparably more cost effective.

Conclusion

There was no statistically significant association between the severity of middle-ear aeration and the frequency of ear toileting in our study. There was also no association between the time since the canal wall down mastoidectomy and the severity of middle-ear aeration. In patients who underwent canal wall down mastoidectomy a long time previously, most still had a retracted neo-tympanic membrane and exteriorised attic. Eustachian tube dysfunction leading to negative middle-ear aeration persisted after the canal wall down procedure. In this study, even those patients with a high degree of middle-ear aeration and longer follow up did not develop cholesteatoma post-operatively. This suggests that retraction pockets may not be the only factor that determines cholesteatoma formation. Our findings may support recent studies that propose a significant role for cytokeratin and keratinocyte growth factor in the proliferation of primary cholesteatoma. However, once the canal wall down procedure has been performed, the local environment changes. The open cavity may suppress cytokeratins and keratinocyte growth factor; thus, cholesteatoma never fully develops in these patients.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to express their utmost gratitude to Prof AB Zulkiflee, a senior researcher from the University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, who kindly edited and suggested ideas to improve the manuscript.

Competing interests

None declared