By the rivers of Babylon we sat down and wept when we remembered Zion. There by the willows we hung up our harps…How could we sing the Lord's song on foreign soil?

For centuries, the musical soundscape of the Ashkenazi synagogue remained essentially insular. The core of the service was the “reading” of the Bible utilizing a set of fixed traditional cantillation motifs, performed modally and monophonically by a soloist in free rhythm. The rest of the service, the chanting of prayers, allowed for slightly more improvisation, but, like biblical cantillation, was based on traditional modes, in free rhythm, with no harmony or instrumental accompaniment.1 The emphasis was on piety rather than on beauty. At the same time, music in Catholic churches was evolving in a strikingly different direction, with the addition of new compositions by professional composers complementing the ancient chant, with harmony and counterpoint in performances by trained choirs, organists, and other instrumentalists.

Christians visiting synagogues were often puzzled by a music that seemed primitive, alien, even ugly in comparison with what they were used to hearing in church. The Frenchman François Tissard wrote of his experience visiting a synagogue in Ferrara, Italy, around 1502, “One might hear one man howling, another braying and another bellowing. Such a cacophony of discordant sounds do they make! Weighing this with the rest of their rites, I was almost brought to nausea.”2

The eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Enlightenment (Haskalah) would bring tremendous changes to the synagogue ritual and its music. But several centuries before that, in the early modern era, there were a few isolated instances of musical innovation in Jewish worship, the most striking of which occurred in Mantua, Italy, at the end of the sixteenth century. Italy had a relatively large Jewish population, and was home to the oldest diaspora community in Europe. The original indigenous population had recently been enlarged by immigrations from Spain and from the lands of Ashkenaz. In the city of Mantua at the beginning of the seventeenth century there were nine synagogues for a population of 2,325 Jews, representing about 4 percent of the general population.3

Under the influence of the humanistic spirit of the Renaissance, many Italian Christians expressed more tolerant attitudes towards their Jewish neighbors. There was also a growing amount of commerce connecting the two communities, with Jews rising to significant positions as bankers, moneylenders, pawnbrokers, and traders of second-hand merchandise. In 1516 Jews were permitted for the first time to establish permanent residences in the city of Venice, on an island that was the former site of a foundry, called “ghetto” in Italian (or “getto” in the Venetian dialect).

Many Jews were becoming increasingly bicultural, fluent in the language, customs, literature, dance, and music of Italy, while at the same time retaining adherence to their ancestral religious traditions. Perhaps the most famous of these bicultural Jews was Rabbi Leon Modena (1571–1648), who served as an intermediary between the Jewish and Christian communities.4 Modena was a skilled author of poetry and prose in both Hebrew and Italian. He was well-versed in rabbinic literature, as well as the Christian Bible, philosophy, scientific theory, and Renaissance literature. He advocated for reforms in the synagogue liturgy but also passionately defended traditional Jewish practice. His Historia de gli riti hebraici, commissioned by an English lord, was the first book to explain the Jewish religion to a general audience. He experimented with alchemy, magic, and astrology, and was a compulsive gambler. Modena was also an accomplished amateur musician, and is credited with encouraging his friend, Salamone Rossi, to compose an unprecedented collection of polyphonic motets in Hebrew for the synagogue.

We don't know very much about Salamone Rossi. He was born circa 1570. His first published music is a book of nineteen canzonets printed in 1589.5 His last published music is dated 1628, a book of two-part madrigaletti. And after that there is nothing. Perhaps he died in the plague of 1628. Perhaps he died during the Austrian invasion in 1630. We just don't know. His published output consists of six books of madrigals, one book of canzonets, one balletto from an opera, one book of madrigaletti, four books of instrumental works (sonatas, sinfonias, and various dance pieces), and a path-breaking book of synagogue motets – in all, some 313 compositions between 1589 and 1628.

***

Most people are principally aware of one culture, one setting, one home; exiles are aware of at least two, and this plurality of vision gives rise to an awareness of simultaneous dimensions, an awareness that – to borrow a phrase from music – is contrapuntal.

In sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Italy, religion was a significant marker of identity. And those who were not situated within the borders of Catholicism were required to signify their status of alterity in their clothing, in their locus of residence, and in their name. Salamone Rossi enjoyed a contrapuntal life in two distinct domains, each set off by its boundaries, both physical and political.

Rossi was employed at the ducal palace in Mantua, where he served as a violinist and composer. He was quite the avant-garde composer. He was the first composer to publish trio sonatas.7 Rossi's madrigals are based on texts by the most modern poets of his time, and he was the first composer to publish madrigals with continuo accompaniment.8 There were many other notable musicians at the Mantuan court, including Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643) and Giovanni Gastoldi (1554–1609). But as far as we know, Rossi was the only Jew. In August 1606, acknowledging Rossi's stature, the Mantuan Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga (1562–1612) issued an edict that stated, “As we wish to express our gratitude for the services in composing and performing provided for many years by Salamone Rossi Ebreo, we grant him unrestricted freedom to move about town without the customary orange mark on his hat.”9 And yet, as we see in the edict, Rossi still bore the epithet “Ebreo” – Jew.

At the Mantuan court, Rossi worked alongside as many as thirty Christian composers, instrumentalists, and singers. Then each night Rossi switched to his Jewish identity, returning to his home in the Jewish ghetto of Mantua, where he lived, and where he worshipped.10 But influenced by Rabbi Modena, Rossi would poke a hole in the cultural boundary line. In a daring innovation, Rossi introduced polyphonic music into the synagogue, bringing the extramural music of the Christian world into the ghetto. In 1622, thirty-three of Rossi's Hebrew motets were published in Venice. The title of the collection, Ha-shirim asher lishlomo (The Songs of Solomon), not only refers to the name of the author (Salamone is the Italian form of Shelomo, or Solomon), but also, by playing on the name of a book of the Hebrew Bible, Shir ha-shirim asher lishlomo (The Song of Songs of Solomon), gives the music an implied intertextual stamp of approval.

As far as we know there were no precedents for Rossi's innovation. Certainly the composer himself believed that was the case. Figure 9.1 shows the title page of Rossi's 1622 publication of his thirty-three polyphonic motets for the synagogue. Notice the words “an innovation (Hebrew: ḥadashah) in the land.” The title page, like the rest of the book, is written almost totally in Hebrew. Here is a translation:

Figure 9.1 Title page of Salamone Rossi, Ha-shirim asher lishlomo (1622).

We can see on this title page some of the challenges of a bi-cultural identity. To describe what they were creating, the authors had to borrow or invent words that did not exist in the Hebrew language. The first word on the page is basso, the Italian word meaning bass, spelled out in Hebrew letters.11 There was no word for harmony or polyphony in Hebrew, so the authors used the Italian word “musica,” again spelled with Hebrew letters. Elsewhere in the book, in order to express musical terminology, Hebrew words were given new meanings. Thus meter was translated as mishkal and music theory as hokhmat ha-shir. This macaronic text with its linguistic code-switching reflected a radical change of culture and musical style.

Indeed the very concept of this book is predicated on both its authors’ and its readers’ ability to negotiate multiple identities. In these polyphonic motets the lyrics are in Hebrew, and the context is the synagogue worship service. But the musical styles, the convention of notation, the musical terminology, and the performative aspect are all borrowed from the culture of Christian Europe.

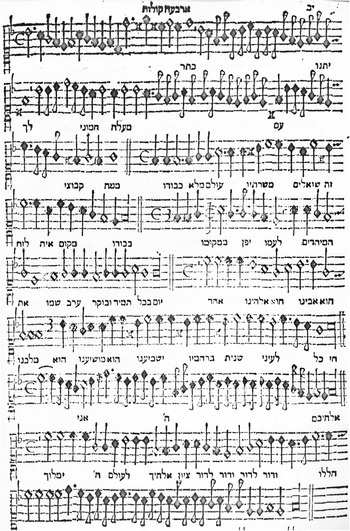

Rossi's bilingual (or bi-directional) identity can be seen most strikingly in a page of music from the 1622 publication (Example 9.1). The musical notation is read from left to right; each word of the Hebrew lyrics, however, must be read from right to left. This manifestation of battling orthographies made for very complicated code-switching.

Example 9.1 Rossi, Keter, canto part book.

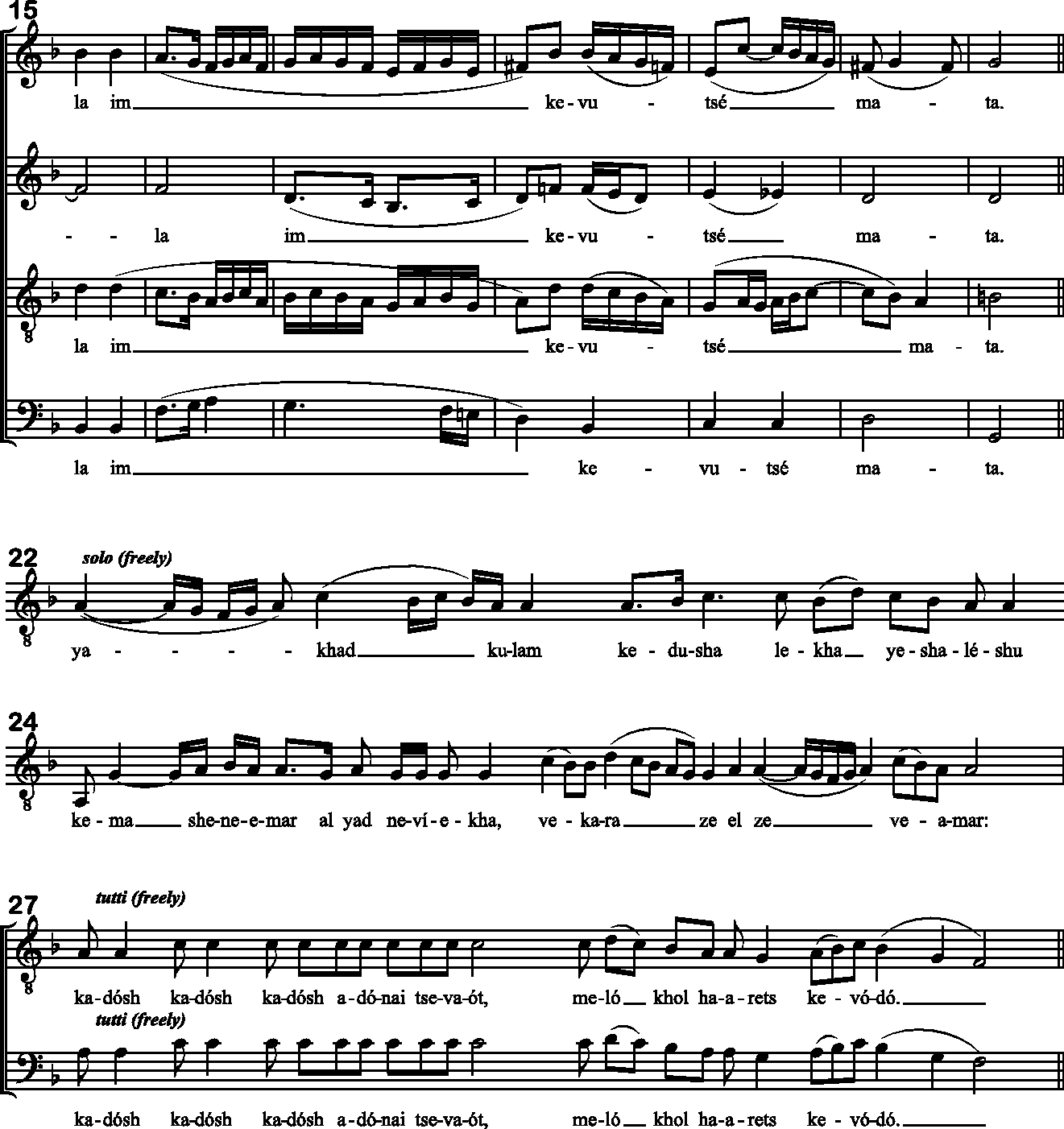

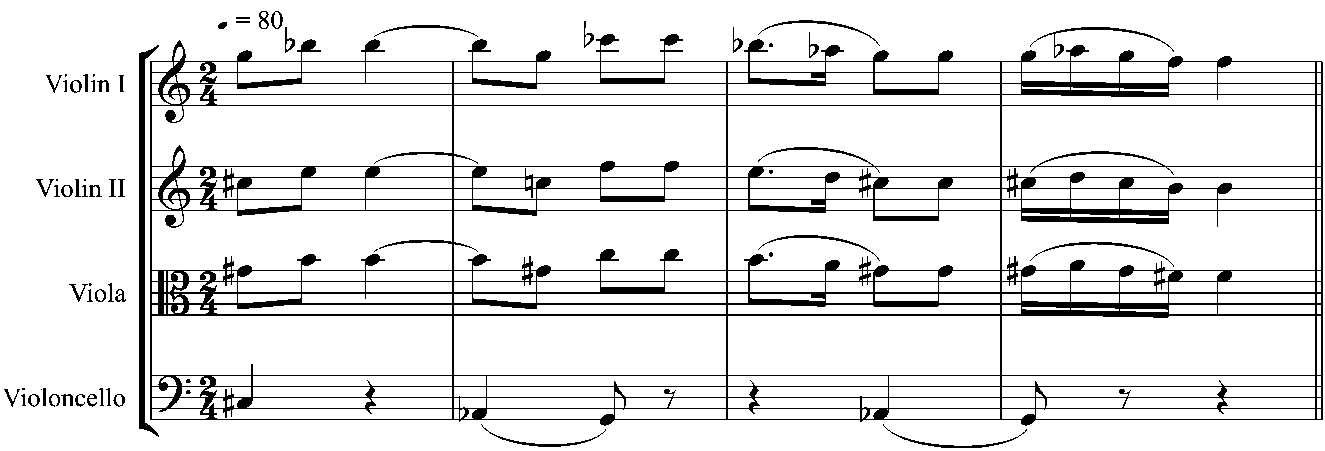

Code-switching also occurs in several of the motets in which the choir would sing certain parts of the prayer in the new polyphonic Italian style, while other sections of the prayer would be chanted by the congregation or the cantor using the traditional monophonic modal melodies. In accordance with the conventions of church music of his time, Rossi inserted double bar lines in the middle of a composition as a signal for the choir to pause while the cantor or the congregation sang the traditional chant. Example 9.2 shows a portion of the present author's attempt to reconstruct a performance of Rossi's Keter.12 Rossi composed music for only a portion of the liturgical text, leaving the rest to be chanted by cantor and congregation in the traditional manner. Rossi's original is shown in Example 9.1.

Example 9.2 Pages 1 and 2 of Rossi's Keter, edited by Joshua Jacobson. Reproduced by permission of Broude Brothers Limited.

Other conventions of Italian polyphony can be found in Ha-shirim. Nine of the thirty-three motets are in the style of cori spezzati, a polychoral format in which singers are divided into two groups in physical opposition, singing at times in alternation, and at times together. This style is commonly associated with the Cathedral of San Marco in Venice, and was widespread in churches throughout Italy and beyond. One of Rossi's polychoral motets, the wedding ode Lemi eḥpots, is set in the “echo” format, well known to choral singers from Orlando di Lasso's “Echo Song” (1581). Lemi eḥpots also features intriguing wordplay between its Hebrew lyrics and Italian homophones. For example, one of the Hebrew lines ends with the phrase kegever be'alma, “as a man with a maid.” The echo chorus then repeats just the last two syllables, alma, which in Italian means “soul.”

One of Rossi's motets suggests a style of dance music that was extremely popular in his time. The Kaddish a5 was composed as a balletto, modeled after his colleague Giovanni Giacomo Gastoldi's 1591 collection Balletti a cinque voci con li suoi versi per cantare, sonare e ballare, which was among the best-selling sheet music of the sixteenth century. Like many balletti, but unique among Rossi's motets, Kaddish is in strophic form, with sharply defined rhythms in a largely homophonic texture. It is also the only motet in the collection in triple meter, which was often used for joyous dancing.

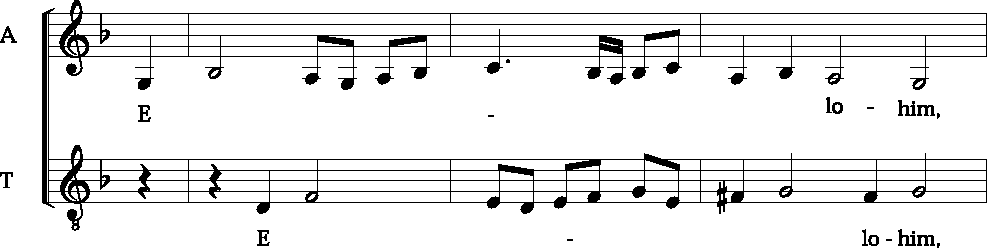

Some of Rossi's melodies link him to his Christian contemporaries. The main theme of Rossi's Elohim hashivenu bears a strong resemblance to Lasso's Cum essem parvulus (Examples 9.3a–b). And the bass line of Rossi's Al naharot bavel is nearly identical to that of his colleague Lodovico Viadana's Super flumina Babylonis, a setting of the same text (Psalm 137) in Latin (Examples 9.4a–b).

Example 9.3a Rossi, Elohim Hashivenu (first phrase).

Example 9.3b Orlando Lasso, Cum essem parvulus (first phrase).

Example 9.4a Rossi, Al naharot bavel, basso (first phrase).

Example 9.4b Lodovico Viadana, Super flumina Babylonis (first phrase).

There was bound to be a conflict between modern Jews who had been influenced by the Italian Renaissance, and those with a more conservative theology and praxis. Rabbi Leon Modena described what happened when Rossi's choral music was sung in a synagogue in Ferrara in 1605:13

We have six or eight knowledgeable men who know something about the science of song, i.e. “[polyphonic] music,” men of our congregation (may their Rock keep and save them), who on holidays and festivals raise their voices in the synagogue and joyfully sing songs, praises, hymns, and melodies such as Ein keloheinu, Aleinu leshabeah, Yigdal, Adon olam, etc. to the glory of the Lord in an orderly relationship of the voices according to this science [music].

Now a man stood up to drive them out with the utterance of his lips, answering [those who enjoyed the music], saying that it is not proper to do this, for rejoicing is forbidden, and song is forbidden, and hymns set to artful music have been forbidden since the Temple was destroyed.14

The objections to choral singing were based on several rabbinic rulings. Living as a tiny minority community in exile, Jews were expected to maintain their unique ancestral culture, and refrain from imitating the practices of the Gentiles among whom they lived. Furthermore, as a sign of mourning for the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem and its renowned music, Jews were expected to refrain from performing or listening to any joyous music. Mar ‘Ukba (early third century) is quoted in the Talmud decreeing, “it is forbidden to sing [at parties].”15 And his contemporary, Rav, ruled, “The ear that listens to song should be torn off.”16

The great philosopher Moses Maimonides (late twelfth-century Spain and Egypt) stressed the historical reasons for Jews refraining from music:

[The rabbis at the time of the destruction of the Second Temple] prohibited playing all musical instruments, any kind of instrument, and anything that makes any kind of music. It is forbidden to have any pleasure therein, and it is forbidden to listen to them because of the destruction [of the Temple].17

But there were exceptions to this ban on music. Music was allowed, even required, to enhance a religious imperative (mitzvah). The medieval Rabbis known as the Tosafists clarified that there are no restrictions on singing at a wedding: “Singing which is associated with a mitzvah is permitted: for example, rejoicing with bride and groom at the wedding feast.”18 Nor would there be any restriction on singing God's praises in a liturgical service, as this Midrash makes clear: “If you have a pleasant voice, chant the liturgy and stand before the Ark [as leader], for it is written, ‘Honor the Lord with your wealth’ (Proverbs 3:9), i.e. with that [talent] which God has endowed you.”19

But the antagonism towards music, especially non-traditional music, remained strong. Anticipating objections over the publication of Rossi's music, Rabbi Modena wrote a lengthy preface in which he refuted the arguments against polyphony in the synagogue:

To remove all criticism from misguided hearts, should there be among our exiles some over-pious soul (of the kind who reject everything new and seek to forbid all knowledge which they cannot share) who may declare this [style of sacred music] forbidden because of things he has learned without understanding, I have found it advisable to include in this book a responsum that I wrote eighteen years ago when I taught the Torah in the Holy Congregation of Ferrara (may He protect them, Amen) to silence one who made confused statements about the same matter.20

He immediately cites the liturgical exception to the ban on music:

Who does not know that all authorities agree that all forms of singing are completely permissible in connection with the observance of the ritual commandments? I do not see how anyone with a brain in his skull could cast any doubt on the propriety of praising God in song in the synagogue on special Sabbaths and on festivals. The cantor is urged to intone his prayers in a pleasant voice. If he were able to make his one voice sound like ten singers, would this not be desirable?…And if it happens that they harmonize well with him, should this be considered a sin? Are these individuals on whom the Lord has bestowed the talent to master the technique of music to be condemned if they use it for His glory? For if they are, then cantors should bray like asses and refrain from singing sweetly lest we invoke the prohibition against vocal music.21

But Modena goes even further in his defense. He argues that if Jews are imitating the music of Christians, it is only to reclaim their own lost heritage. Modena is using here a classic Renaissance argument. Restoring the glorious culture of antiquity was at the heart of the Italian Renaissance. The Florentines who invented opera claimed that they were reviving the art of ancient Greek theater. Modena claimed that Rossi was actually reviving the musical practice of the ancient Temple in Jerusalem, “restoring the crown of music to its original state as in the days of the Levites on their platforms.”22 Modena asserted that the music of Christian churches was derived from the practice of the Levitical choir and orchestra in the ancient Temple in Jerusalem. He quotes Immanuel of Rome, who wrote that Christian music “was stolen from the land of the Hebrews.”23 Therefore, he and Rossi were merely reclaiming the lost heritage of the ancient Israelites.24

Modena indulges in hyperbolic praise in his description of the culture of ancient Israel:

For wise men in all fields of learning flourished in Israel in former times. All noble sciences sprang from them; therefore the nations honored them and held them in high esteem so that they soared as if on eagles’ wings. Music was not lacking among these sciences; they possessed it in all its perfection and others learned it from them. However, when it became their lot to dwell among strangers and to wander to distant lands where they were dispersed among alien peoples, these vicissitudes caused them to forget all their knowledge and to be devoid of all wisdom.25

There is no record of Rossi after 1628, when there was an outbreak of the plague in Mantua. In 1630 the ghetto was evacuated during the Austrian invasion, and some of the residents relocated to Venice. Leon Modena established a Jewish musical academy in Venice that functioned from 1628 until around 1638, but there is no mention of Salamone Rossi.

There is no evidence of any other collection of polyphonic synagogue music of the size and quality of Ha-shirim until the nineteenth century. The musicologist Israel Adler discovered several isolated instances of art music that were performed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in the synagogues of Venice, Siena, Casale Monferrato, Amsterdam, and Comtat Venaissin.26 These are delightful works, most of them composed by Christian musicians for special occasions, but none having the depth of Rossi's Ha-shirim.

Ha-shirim seems to have been largely forgotten after Rossi's death until the middle of the nineteenth century. While on vacation in Italy, Baron Edmond de Rothschild was given an unusual collection of old part books of music with Hebrew lyrics. Rothschild thought they might be of interest to his synagogue choir director Samuel David, who passed them along to Samuel Naumbourg, Cantor of the Great Synagogue of Paris. With the assistance of a young music student named Vincent D'Indy, Naumbourg prepared the first modern edition of Rossi's music in an anthology that included thirty of the thirty-three motets and was published in 1876. Naumbourg chose modernization over historical accuracy. In accord with nineteenth-century standards, he felt free to add his interpretations for tempo and dynamics, transpose to a different key, rearrange for a different number of voice parts, alter rhythms, even substitute different lyrics. But his edition did instigate a revival and brought Rossi's music to a wider audience. In the twentieth century several new editions of Ha-shirim were published, for both scholars and performers, and numerous recordings were issued. The most significant scholarship on Rossi to date has come from musicologist Don Harrán, who has written an impressive monograph, and edited all of Rossi's music for the American Institute of Musicology's Corpus Mensurabilis Musicae.

Sing unto him a new song; play skilfully.

A new meaning for “Jewish music”

From February 1850 onwards a series of increasingly vituperative articles, attacking the opera Le prohète by Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791–1864) following its debut (in German) in Dresden, began to appear in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. They were written by the friend, disciple, and correspondent of Richard Wagner (1813–83), the Dresden musician Theodor Uhlig (1822–53). They culminated in a series of six essays, Zeitgemässe Betrachtungen (Contemporary Observations), attacking Meyerbeer's pretensions to the creation of musical drama or beauty; as opposed, of course, to the compositions of Uhlig's hero Wagner. The first of these “Observations,” entitled “Dramatic,”1 swiftly highlights the writer's objective; despite his success, the “false Prophet” Meyerbeer, as a Jew, can be no true German, and his music is a betrayal of German art. Uhlig cites three two- or three-bar snippets from the opera's last act, which he claims “belch out” (aufstossen) at us, for their allegedly unnatural word-setting and crudity of expression. These are scarcely representative of the opera as a whole (and no worse than similar examples that could be extracted from Wagner's Lohengrin). Uhlig then comments:

If that is dramatic song, then Gluck, Mozart, and Cherubini carried out their studies at the Neumarkt in Dresden or the Brühl in Leipzig [i.e., in those cities’ Jewish quarters]…[T]his way of singing is to a good Christian at best contrived, exaggerated, unnatural and slick [raffinirt]…[I]t is not possible that the practised propaganda of the Hebrew art-taste [hebräisches Kunstgeschmack] can succeed by such means.2

It is perhaps needless to say that none of the musical examples cited by Uhlig bear the slightest resemblance to Jewish music, either of the synagogue or the klezmorim. But when Wagner adopted Uhlig's formulation of a “Hebrew art-taste” in his anti-Jewish assault “Das Judentum in der Musik”3 (initially published anonymously in the Neue Zeitschrift as a “response” to Uhlig), he shrewdly refrained from giving examples or even attempting to define this concept in musical terms; instead he relied on traditional Jew-baiting principles. Just as a Jew cannot speak German properly, but can only produce a “creaking, squeaking, buzzing snuffle,” Wagner concludes that inevitably his attempts at creating song, which is “talk aroused to highest passion,” must be even more insupportable.4 Music produced by Jews, decreed Wagner, was thereby inherently corrupted into “Jewish music,” and hence a false art, even in the more sophisticated compositions of Felix Mendelssohn (whom Wagner oleaginously damns with faint praise).5 Moreover, Jews treat art just like any other commercial commodity and are only interested in exploiting the public's lack of taste by making money from it.6

Thus was initiated a concept of “Jewish music,” quite independent of Jewish musical traditions, and musicologically indefinable, that would lead ultimately to the bible of National Socialist musicologists, the Lexikon der Juden in der Musik,7 and, ironically by the same process, to the quasi-martyrological status in the present day of those musicians who, whether or not they had any interest in or knowledge of Judaism, perished as a consequence of their ancestry and Nazi Germany's criminal racial politics. The genesis of this concept must be sought, therefore, not in any definable characteristics observable in the music of those concerned, but in the remarkable success of Jews in making a reputation for themselves in the world of music in the period from the late eighteenth-century onwards, and the reception of this success among their contemporaries.

Advent of Jews to the world of art music

Taste and employment in the arts, in an age predating global publicity, were determined by patronage. It is therefore no surprise that while such patronage was monopolized in Europe by the Church and the aristocracy, Jews were not to be found in the realm of art music. They had no means of learning or acquiring its techniques, and in any case their semi-feudal status in most of the continent would not have permitted employment outside their permitted trades. Indeed the only notable manifestation of Jews in the world of musique savante before the eighteenth century was the brief period 1600–30 when the community of Mantua was indulged by the Gonzaga family and produced not only the composer Salamone Rossi (c. 1570–c. 1628), whose Monteverdian output included both secular madrigals and settings of Hebrew prayers (see Chapter 9), but a host of other Jewish musicians, singers and dancers.8

As a caste living at the fringes of Western European society, Jews were moreover held to be beyond the cultural pale, a people, as Voltaire put it, “without arts or laws.”9 Music of the synagogue was caustically derided by Gentile commentators who bothered to investigate it with comments such as “a Hebrew gasconade…a few garbled and conjectural curiosities,”10 or “It is impossible for me to divine what idea the Jews themselves annex to this vociferation.”11 As to Jewish folk music, it was, like all others, overlooked by the cognoscenti. The cliché that the Jews were a “musical people,” commonplace by the end of the nineteenth century, would have seemed absurd at its commencement.

The disdain evinced towards Jewish music was not only an expression of traditional Jew-hatred. Parts of the synagogue services had remained “icons” of those of the Temple, and still retained (and retain today) elements of chants, modes, inflexions, and rhythms not reducible to the ideas of harmony and form that musical theoreticians were beginning to systematize in the eighteenth century. This “otherness” was more simply dealt with by dismissal than analysis. It was also easy to equate this non-conformity with an immoral betrayal of the duty of music to purvey a noble Affekt; this “moralistic” distaste for music of the Jews can still be found underlying Wagner's “Judentum in der Musik.”12 It is in this context that we must read the genuine surprise of Carl Zelter (1758–1832) at the talent of his new pupil Felix Mendelssohn (1809–47) in an 1821 letter to his friend Goethe: “It would really be something special if for once a Jewboy [Judensohn] became an artist.”13

Nonetheless, from around the beginning of the eighteenth century we begin to see an increasing interplay between Jewish urban communities and the musical life of their hosts in western Europe. At the end of the seventeenth century, the synagogue at Altona issued a series of decrees deterring members from attending the opera at nearby Hamburg (where Singspiels – works of musical theater combining German singing and speech – in the early eighteenth century featured caricature Jews speaking in mauscheln, the crude word used by non-Jewish Germans to discuss Jewish-German speech mannerisms).14 In the same period Jews in Frankfurt and Metz began to complain about the inclusion of music from the theater in synagogue services,15 and wealthy Sephardic Jews in Amsterdam became noted musical patrons (and even commissioned settings for their synagogues from Gentile composers).16 It is scarcely surprising that early evidence of Jews as active in the world of Gentile music comes from the two urban centers, Amsterdam and London, within states whose constitutions were least prejudiced against Jews.

As with many immigrant communities seeking entry to society (even today), musical entertainment was a popular career option for Jews. For such a profession capital requirements are low and all that may be necessary for success is some talent (and perhaps chutzpah). The very exoticness of the aspirant may be in itself an advantage where an audience, freed from the restrictions of ordained taste, seeks novelty. We see a harbinger of this in “Mrs. Manuel the Jew's wife,” who caught the eye and ear of Samuel Pepys in 1667/8 (just some ten years after Cromwell allowed the Jews to return to England following the 1290 expulsion) – “[she] sings very finely and is a mighty discreet, sober-carriage woman.”17 Hanna Norsa (c. 1712–84), the daughter of a Jewish tavern-keeper, made the classic transition from stage success in 1732 (as Polly in John Gay's Beggar's Opera), to mistress of an aristocrat (the Earl of Orford, Horace Walpole's brother).18 David Garrick introduced Harriett Abrams (c. 1760–1821) as the title role in his 1775 May Day: or the Little Gypsy, causing a newspaper to exclaim, “The Little Gipsy is a Jewess…the numbers of Jews at the Theatre is incredible.” This was the start of a long and distinguished profession for Abrams as a singer and a songwriter – and also an early example of Jewish audiences in London “supporting their own.”19 The notable operatic careers of the ḥazzan (cantor) Myer Lyon (c. 1748–97) (who appeared at Covent Garden as “Michael Leoni” and was allowed Friday nights off for his synagogue duties) and his protégé and sometime meshorer (descant) John Braham (c. 1774–1856) arose from their singing at London's Great Synagogue; the unusual qualities of their voices are likely to have arisen from the synagogue musical tradition.20 Yet another form of musical fame founded in the synagogue was that of the egregious Isaac Nathan (c. 1792–1864), son of a ḥazzan, who, cashing in on the trend for esoteric folk music, was able to publish his arrangements of synagogue tunes through his improbable partnership with Lord Byron, whom he persuaded to write the words for his Hebrew Melodies (published in 1815). Cannily, Nathan persuaded Braham to allow his name to be placed in the front page in return for 50 percent of the profits. Nathan's turbulent career led to his retreat to Australia, where his musical pioneering earned him the accolade of “the father of Australian music.”21

Jewish musicians of Germany and France

While after the 1820s we find few significant home-grown Jewish musicians in England, a new generation of Jewish musicians emerged on the Continent of a very different type from those who, from Norsa to Braham, had chanced their way up virtually from the pavements. Typically they were, like the opera composer Giacomo Meyerbeer (born Jakob Beer, 1791–1864) or Felix Mendelssohn and his sister Fanny (1805–47), the offspring of merchant or extremely wealthy German-Jewish families whose parents had provided them with a musical education as part of an increasing fashion for acculturation with their host country. Lesser lights in this category include Ferdinand Hiller (né Hildesheim, 1811–85), Julius Benedict (1804–85), and the Prague-born Ignaz Moscheles (1794–1870), who became a close colleague of Mendelssohn.

The trend to German culture in this class had commenced in the mid-eighteenth century with the advance of Enlightenment ideas amongst progressive Jewish thinkers, notably Felix's grandfather Moses Mendelssohn (1729–86), which flourished amongst the wealthy Jewish elite in Germany and Austria who had associated themselves with Court and state finances. This movement inevitably accelerated as the French Revolutionary Army moving through continental Europe opened the ghettos and transformed the previous status of Jews, which had been virtually feudal, to that of (more or less) equal citizens. The education of the new generation of privileged Jews (for the mass of European Jewry was still extremely poor) coincided with a transfer of patronage in the arts towards the moneyed bourgeois – thus providing many opportunities for change, access, and career opportunities, notably (for Jews) in literature and music. In the fashionable Jewish salons of Berlin and Vienna of the early nineteenth century (among which the Mendelssohn and Beer families, and their Austrian relatives the Arnsteins and Eskeleses, were prominent), Gentiles from the worlds of the arts and politics mingled with the social newcomers, testifying to these changes. In the fashion of Romanticism, the exotic Jews, newcomers to cultured society, became a fashionable trend before the vogue of völkisch nationalism from the 1820s onwards began to disturb their status.

In these circumstances it is scarcely surprising that traditional Jewish music played little or no part in the musical upbringing of this generation. Felix Mendelssohn and his sister were brought up as Christians; most others of a German background (with the notable exception of Meyerbeer) converted to Christianity at some stage, as a matter of convenience if not deep belief. Moreover it was clear from an early stage that the traditional synagogue turned its back on contemporary Western culture. When the Vienna congregation commissioned a cantata to celebrate the Treaty of Paris in 1814 from the young Moscheles, the Pressburg (Bratislava) Rabbi Moses Schreiber issued a ruling that it was quite unacceptable for women's and men's voices to be heard together in a synagogue.22 It was left to the Jewish Reform movement to later populate synagogue services with quasi-Schubertian or Mendelssohnian strains such as those penned by the cantors Salomon Sulzer (1804–90) or Louis Lewandowski (1821–94) (see Chapter 12).

In France, a different route to musical careers was enabled by the confirmation of full citizenship to Jews following the decision of the National Assembly in 1791. This entitled those with the ability, even if from poor backgrounds, to attend the Paris Conservatoire; amongst those to take advantage of this opportunity were the opera composer Fromental Halévy (1799–1862) and the piano virtuoso and composer Charles-Valentin Alkan (1813–88) (neither of whom converted).

It is the latter who, in some of his Préludes op. 31 (1844), and in the melodies of his Sonate de concert for cello op. 47 (1857), created perhaps the first published artworks based on Jewish music.23 That is not to say that other Jewish composers ignored such music. We know from correspondence that Mendelssohn, who it appears never so much as entered a synagogue, and his sister Fanny were fascinated by the music of the klezmer Joseph Gusikov (1806–37),24 and that Hiller was to introduce his (non-Jewish) pupil Max Bruch (1838–1920) to the Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement) hymn Kol Nidre, which in 1881 the latter made into one of his greatest successes.25 But, other than in the works of Alkan, we may seek in vain, despite the most energetic efforts of some scholars, to find a note of Jewish melody, or even idiom, in works of this generation. The search for such links ranges from Eric Werner's exotically optimistic attribution of a key melody in Mendelssohn's 1847 Elijah,26 to the quite unfounded statement that the Passover meal scene in Halévy's 1835 opera La Juive “reflect[s] an awareness of traditional Jewish practice” and is “an authentic treatment…of ceremony”27 (although indeed Halévy, who came from a practicing Jewish household, certainly knew how a seder ought to be conducted). Indeed the libretto of La Juive, in its presentation of the vengeful, money-obsessed, and secretive Eléazar, seems to truckle to the basest prejudices of Judaeophobia. Significantly, contemporary reviews of the opera do not relate the storyline in any way to the social situation of Jews of France in the 1830s (or even mention that the composer is a Jew), being more concerned with its attitude to the Church.28

Where a “Jewish” sympathy may be found in the operas of Meyerbeer is not in their music, but in their storylines. Meyerbeer's Robert le diable came to the stage the year after the July Revolution of 1830, which ushered in a new era for France of bourgeois liberalism in reaction to the conservative world of Charles X. Nothing could have been more attuned to the new spirit than this brash, novel, and spectacular work, produced with the finest singers of the day, using all the technical resources of the Opéra stage; Meyerbeer became an instant Europe-wide celebrity, and remained as such with the similar successes of his further grand operas, all to librettos by Eugène Scribe: Les Huguenots (1826), Le prophète (1849), and the posthumously produced L'Africaine (1864). Uniquely, because of his wealth and authority, Meyerbeer had the opportunity to choose and shape his libretti; and it is no accident that each of his works in this form has a hero (in sequence Robert, Raoul, Jean of Leyden, and Vasco da Gama) who, for reasons of birth, religion, or belief is a neurotic outsider in his own society – Meyerbeer himself retained with his Judaism an excessive sensitivity to slights, both real and imagined, to his origins, as his diaries and correspondence reveal.

Reception of Jewish musicians

The German writer and convert Ludwig Boerne (1786–1837; born Judah Loew Baruch) wrote in 1832, “Some people criticize me for being a Jew; others forgive me for being one; a third even praises me for it; but all are thinking about it.”29 This is the atmosphere in which all musicians of Jewish extraction operated throughout the nineteenth century and beyond. Inevitably this was to affect their careers, status and public perception – and their music – in ways both direct and indirect.

“Jewishness” is not merely a matter of practiced religion, but also of yiddishkeit – the secular customs, use of Yiddish, shared humor, and mutual identification – which persisted as much amongst those who, like Felix Mendelssohn, were never circumcised, as those who, like Meyerbeer, remained (more or less) practicing Jews. Not least of the consequences was the tendency of such musicians, whether they attended church or synagogue, to associate closely with friends and collaborators of a similar status. Felix and the Mendelssohn family continued to have in their circle Moscheles, Benedict, Hiller, the violinists Ferdinand David (1810–73) and Joseph Joachim (1831–1907), the composer and writer Adolf Bernhard (né Samuel Moses) Marx (1799–1866) and many other Neuchristen; not only that, they can still be found in the company of many of their contemporary Neuchristen in the same section of the Dreifaltigkeit Cemetery in Berlin. Also striking was the connection of many Jewish composers to the successful music publisher Adolf Martin (né Aron Moses) Schlesinger (1769–1838) in Berlin (and to his son Maurice Schlesinger [1798–1871] in the Paris branch of the business). Schlesinger, who began his bookselling business in 1810, became the publisher of many of Beethoven's late masterpieces, made a fortune from his early “spotting” of Carl Maria von Weber,30 and was Mendelssohn's first publisher. Schlesinger-owned music journals in Berlin (edited by A. B. Marx) and Paris naturally supported “house” composers.31 Apart from publishing Meyerbeer and Halévy, Maurice also published works of Liszt, Berlioz, and many other leading Parisian musical celebrities. He incidentally employed the impoverished Wagner in 1840–1 to write articles for his Gazette musicale and to make arrangements of opera arias; and indeed he was responsible for introducing Wagner personally to Liszt in his shop.32 It was perhaps this sense of an extra-musical cartel amongst his contemporaries that prompted Robert Schumann to comment in his wedding diaries that he was fed up with promoting Mendelssohn: “Jews remain Jews: first they take a seat ten times for themselves, then comes the Christian's turn.”33

Apart from this clannish dimension of yiddishkeit, other factors demarcated these musical newcomers in the minds of their Gentile colleagues; notably, as regarded the German musicians, their often wealthy (or at least comfortable) origins. Whereas, for example, Wagner was only able to dream of traveling to Italy to study,34 Meyerbeer was comfortably subsidized by his family to study and write his early operas there for seven years. Berlioz noted, “I can't forget that Meyerbeer was only able to persuade [the Paris Opéra] to put on Robert le diable…by paying the administration sixty thousand francs of his own money”35 (an allegation that is in fact unfounded). Robert Schumann wrote to Clara Wieck of Mendelssohn in 1838, “If I had grown up under circumstances similar to his, and had been destined for music since childhood, I'd surpass each and every one of you.”36

Not only this, but in the growing ethos of musical nationalism, Jews were difficult to “place.” When Meyerbeer's friend Weber had written, in 1820, about the former's Italian operas, “My heart bleeds to see how a German artist, gifted with unique creative powers, is willing to degrade himself in imitation for the sake of the miserable applause of the crowd,”37 he could of course hardly have foreseen how such comments could be recast under the more strident nationalism of later decades, when the “Germanness” of the artist concerned might become the crux of the issue. Once again, it is Schumann, in his vituperative 1837 review of Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots, who gives a foretaste of the critique of Uhlig and Wagner: “What is left after Les Huguenots but actually to execute criminals on the stage and make a public exhibition of whores?…One may search in vain for…a truly Christian sentiment…It is all make-believe and hypocrisy…The shrewdest of composers rubs his hands with glee.”38

And of course the extraordinary success of Jewish musicians was bound to excite pure envy. Following the successes of La Juive and Les Huguenots at the Paris Opéra, the truculent opera composer Gaspare Spontini (1774–1851) (whom Meyerbeer was in fact to replace as Kapellmeister in Berlin in 1842) was satirically said to have been observed weeping at the mummies of the Pharaohs at the Louvre, complaining that they had let the Jews go free.39 Mendelssohn's appointments as musical director in Düsseldorf (1833) and later Leipzig (1835), and the appointments of both Meyerbeer and Mendelssohn at the more liberal court in Berlin of Frederick William IV after 1843, signified their influence in Germany, where the support of Meyerbeer enabled the production of Wagner's Rienzi in Dresden in 1842, and the indifference of Mendelssohn to Wagner's offer of his Symphony in Leipzig in 1836 was another source of the latter's sense of grievance.40

What Jewish musicians contributed to European musical life was indeed to some extent associated with a change of public taste to grandeur and sensation. The works of Meyerbeer, whose musical innovation was to combine the colorful orchestral romanticism of Weber with the vocal pyrotechnics of Italian opera, fitted well with this trend. So did the pianists who became, in the words of Heine, “a plague of locusts swarming to pick Paris clean” in the 1830s and 1840s, many of them as juvenile prodigies – amongst the Jewish-born exemplars being Jakob Rosenhain (1813–94), Julius Schulhoff (1825–98), Louis Gottschalk (1829–69), and Anton Rubinstein (1829–94) (who partnered Halévy's student Jacques Offenbach [1819–80] in the latter's debut Paris recital as a cellist in 1841). It may be that the status of Jews as “newcomers” freed them to some extent both from allegiance to the supposedly more refined tastes of earlier generations, and from the dictates of the self-appointed bearers of the standards of “true art” of German nationalist romanticism, so as to meet the demand and taste of the expanding audiences of the bourgeois. Perhaps this is part of what suggested Wagner's accusation of commercialism (the word “Judentum,” in the title of his tirade, in colloquial German of the time carried not only the meaning of “Jewry,” but also “haggling”.41

But on the other hand the serious and scholarly approach of Mendelssohn, Moscheles, and their school – to whom, in fact, the music of Meyerbeer and the piano virtuosi were anathema – scarcely fitted this characterization of commercialism. Mendelssohn himself was indeed a prime mover in the rehabilitation of the music of the great German masters, Bach and Handel, and Moscheles was a pioneer of the “historical recital,” including performances on the harpsichord.42 To Wagner, and to other advocates of new music, however, such “classicism” was as much a threat as the popularity of grand opera in alienating the affection of potential audiences for their own art. Wagner indeed succeeded in coupling this dedication to tradition with his more traditional Jew-baiting approach in a repulsive metaphor of the decaying flesh of German art dissolving into “a swarming colony of insect-life.”43

Despite all the above, however, only in Germany is there significant evidence of Jewish musicians and their music being a source of contention for their contemporaries. Berlioz in an 1852 article derided the notion of “Hebraic elements” compromising Mendelssohn's music.44 In Britain, Mendelssohn became an honored guest in his ten visits, and his descent from Moses Mendelssohn was noted with approval. Indeed after his death he was incarnated in thin disguise as the Chevalier Seraphael, in the very popular novel Charles Auchester (1855), by the teenaged Elizabeth Sheppard, in which his Jewishness was cited as the source of his musical genius.45 In the concert halls and opera houses of London and Paris, music that Jews wrote or played was not distinguished as a separate category. Only later in the century, with the birth of political anti-Semitism as a mass movement, and Wagner's later return to the fray in 1869 with a lengthened version of his attack (this time published under his own name), began the transformation of the notable musical achievements of Mendelssohn, Meyerbeer, and their generation into a stick with which to beat them. And not until the end of the century, and partly in reaction to this development, would Jewish musicians, notably the activists of the St. Petersburg Society for Jewish Folk Music, begin at last a musical exploration of their own ancestral heritage.

Introduction

In his memoirs, the Russian Jewish poet and translator Leon Mandelshtam (1819–89) describes an 1840 visit he paid to the legendary Minsk cantor Sender Poliachek (1786–1869). A musical illiterate, Poliachek had won fame for his liturgical compositions that were said to evoke the “soul” of the Jewish past. Mandelshtam himself had fled a small-town life of religious traditionalism for Moscow, where he would become the first Jew to graduate from a Russian university. Yet he felt compelled to stop en route in Minsk to ask the venerable cantor a question: Where did this music of the Jews come from? Was it a product of the East, signifying that the Jews of Russia were descended from the medieval Khazars who had converted to Judaism? Or was it derived from Western Europe, proving that the Jews had migrated to eastern Europe from Spain and Germany, pushed on by the violence of the Crusades? Perhaps, Poliachek replied, since the Jews had lived under both Muslims and Christians, their music was a cultural hybrid: East and West had fused together to produce the distinctive “binational Jewish melody.”

The conversation did not end there. For the cantor then surprised Mandelshtam with a question of his own. Why, he wished to know, would such a nice and talented young man abandon his people to go live in Moscow like a Christian? Mandelshtam replied with a pithy rabbinic maxim: “Better to be last among lions, than first among hares.” Poliachek was unimpressed. He too had once felt the lure of Western music, he explained, before concluding that such a career would have ruined his distinctive Jewish voice: “A spring quenches the thirsty man if he is on dry land; let him be in the sea, and it is of little use. The moonlight dazzles your eyes at night; during the day it is but a pale patch in the sky. In my primitive national form I am distinct; mixed together with all the colors, I would become lost in the crowd.” Undeterred, Mandelshtam countered that the modern world did not scare him: “A country is only a miniature image from space; a year is only time in a smaller form; the same is true of virtue, which, similar to genius, lies above space and time, and fears neither foreign lands on the road of wandering nor temptation in the era of modern life.”1

This exchange between the cantor and the poet neatly summarizes the main themes of the history of Jewish art music from the middle of the nineteenth century through the first quarter of the twentieth. Before 1800, only a handful of European Jews had ventured beyond the confines of the Jewish community into the world of European art music. Many rabbinical authorities frowned on secular musical education as a dangerously seductive pathway to heresy. Even knowledge of Western musical notation was regarded in some quarters with suspicion. In turn, Christian Europeans looked on Jews as an alien culture whose musical practices threatened to contaminate Western art. Yet, at the same time, late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Jewish liturgical and folk music professionals – cantors and klezmorim – exhibited increasing interest in Baroque vocal genres, opera and operetta, and European court dances. The allure of art music proved quite strong. From the middle of the nineteenth century onwards, Jewish musicians flocked in extraordinarily high numbers to conservatories across Europe with profound consequences for both Western music and modern Jewish identity.

Mandelshtam's query about the historical origins of the music of the Jews and the cantor's expansive yet curious reply (Christian-Muslim “binational Jewish melody”) also point to the ambiguous place of “Jewish music” in the modern European imagination – both Jewish and Christian. From Richard Wagner's famous 1850 anti-Semitic essay “Das Judentum in der Musik” to the racialist theories of fin-de-siècle French and Russian critics, ideological fantasies about the essentialist character of Jewish music – and its indelible imprint in the works of composers of Jewish origin, and even in the styles of Jewish performers – surfaced repeatedly in European culture. Likewise, early twentieth-century Jewish nationalists produced elaborate musical theories of their own. Indeed, the entire project of modern Jewish art music can be characterized as an ongoing search for an answer to the question of how to define the genre of Jewish music horizontally – belonging to the “Oriental” East or Christian West – and vertically – as an autochthonous tradition extending from biblical antiquity to the modern times. Just as Mandelshtam's anecdote suggests, the modern dialogue with the Jewish musical past emerged as a constant theme across the first several generations of Jewish composers. For some of these artists, Jewish religious sonorities required delicate refinement to meet the new aesthetic dictates of Enlightenment rationalism in nineteenth-century Europe (“the era of modern life”). For others, modernity demanded a radical re-imagination of Jewish vernacular and liturgical traditions into a secular form of national art music (at once “primitive” and “modern”). Still other composers gravitated to modernism as a utopian quest to liberate all art and artists – from the particularistic confines of nation and religion (“above time and space”).

This chapter explores these developments through a chronological survey of the period between 1850 and 1925, highlighting major figures as well as shifts in cultural ideas of Jewish music and musicianship down through time. It is divided into three sub-periods: Hebrew Melodies: Virtuosity and Antiquarianism, 1850–1900; Aural Emancipations: Renaissance and Modernisms, 1900–17; and Revolutionary Echoes: Affirmations and Ambiguities, 1917–25.

Hebrew melodies: virtuosity and antiquarianism, 1850–1900

At the dawn of the nineteenth century, the idea that a Jew might excel in the realm of European art music constituted an odd, if not unnatural, proposition. Over the next half-century, however, western and central European Jews began a dramatic ascent into the ranks of professional musicians. This socio-cultural trend, already visible in nucleo before 1800, swelled into a remarkable – and much remarked upon – pattern of Jewish virtuosos by the middle of the nineteenth century. Jewish child prodigies became the norm for the next seventy-five years, with hundreds upon hundreds of pianists, violinists, cellists, and other musicians concertizing across Europe at very young ages. Some of these notable performers went on to notable careers as composers, including the likes of Ignaz Moscheles (1790–1870), Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791–1864), Charles-Valentin Alkan (1813–88), and Anton Rubinstein (1829–94). Many others swelled the ranks of the new conservatory faculties, symphony orchestras, and other musical institutions that emerged as prime features of nineteenth-century European musical life.2 All contributed to an image of Jews as singularly talented in the field of art music, though contemporary observers differed widely in their estimation of the sources and meaning of that talent.

In hindsight, historians have explained the rapid gravitation of Jews to art music and extraordinary professional success as stemming from the confluence of several factors: the long-established pattern of music as a hereditary profession in pre-modern European Jewish life; the relative openness of new cultural spheres that catered to a newly ascendant urban bourgeoisie with a strong appetite for secular entertainment; the concrete economic opportunities represented by these new cultural realms, which also attracted a considerable quotient of Jewish musical entrepreneurs, sheet-music publishers, concert impresarios, and critics; the broader pattern of Jewish embourgeoisement, reflected in the popularity of both childhood musical training and amateur chamber music performance as key features of European salon life; and the identification of many leading classical musical figures (though certainly not all) with the cause of political liberalism. In a larger sense, the Jewish movement into art music was a legacy of the late eighteenth-century Enlightenment, which framed music as a secular activity, musical talent as an innate human gift irrespective of particular origin, and art as a path to moral self-cultivation and modern individualism.3

Significantly, what does not appear to have played a strong role in this process, contrary to popular perception, was the force of Jewish religious tradition or traditional rabbinic cultural values. In spite of its significance in pre-modern Jewish life, including in synagogue and wedding rituals, music remained a low-status profession with musicians occupying an ambivalent position in the social hierarchy of the Ashkenazic Jewish community.4 Nor, with a few notable exceptions, did most of these first few generations of nineteenth-century concert musicians evince much direct self-consciousness about their Jewish musical heritage or active compositional engagement with Jewish themes. Indeed, music beckoned precisely as an ostensibly unobtrusive path of acculturation and social advancement in mainstream European bourgeois society.

That religion was not the motivating force drawing Jews to classical music did not mean that art lacked spiritual significance. On the contrary, for many Jews – both professional performers and dedicated concert patrons – classical music constituted a veritable alternative religion. A case in point is the legendary Hungarian-born violinist Joseph Joachim (1831–1907). A pioneering force in European concert life and musical pedagogy, long a fixture of German musical life, and a close collaborator of Brahms, Schumann, and others, Joachim redefined the nature of violin playing and chamber music during his long career. A nominal convert to Christianity, he remained identified as Jewish yet practiced neither religion. Listening to Beethoven's music, he once wrote, was like listening to the “Religion of the Future” (Zukunftsreligion).5 In this way, absolute music – instrumental music without words – offered an attractive ideal of a universalist realm beyond language, religion, and national differences that otherwise defined so much of the Jewish experience in modern Europe. A later quip retold by the German Jewish humorist Alexander Moszkowski, brother of the noted composer and pianist Moritz Moszkowski, conveyed a similar sentiment: “[I have] no sympathies for any ritual aspects of our religion. Of all the Jewish holidays the only one I keep is the concert of Gruenfeld [a famous Austrian Jewish pianist].”6

When Jewishness did surface as a specific theme in nineteenth-century European art music it came clothed in the Romantic garb of a virtuous antiquarianism. Like Jewish visual artists of the day, Jewish composers looked backwards to biblical antiquity in search of religious themes suitable for a modern era of rational religion and improved Jewish-Christian relations. This trend might be said to have officially begun with the British Jewish composer Isaac Nathan's 1815 collection of song settings of the poet Lord Byron's “Hebrew Melodies,” a common touchstone for many later composers of Jewish-themed music, both Jewish and Christian.7 Like Nathan's work, these aural imaginaries often took the form of compositions that addressed the historic borderlines and commonalities between Judaism and Christianity, such as Felix Mendelssohn's oratorios Elijah (1846) and St. Paul (1836), Jacques-François-Fromental-Élie Halévy's opera La Juive (1840), Ferdinand Hiller's oratorios The Destruction of Jerusalem (1840) and Saul (1858), Joachim's “Hebrew Melodies” (1854) for viola and piano, Karl Goldmark's opera The Queen of Sheba (1875), and Friedrich Gerns-heim's Symphony No. 3 in C minor, “Miriam” (1888), inspired by Handel's Israel in Egypt oratorio.

Particularly notable exemplars of this pattern came in the works of two of the greatest pianist-composers of the nineteenth century: Anton Rubinstein (1829–94) and Charles-Valentin Alkan (1813–88). Born in the Jewish Pale of Settlement and baptized in the Russian Orthodox Church as an infant, Rubinstein went on to global fame as a concert performer, composer, and artistic celebrity. At the same time, he introduced a modern conservatory system into the Russian Empire that generated a unique social pathway for two generations of Russian Jewish musicians to achieve an unprecedented professional status and legal freedom in an otherwise tightly regimented, illiberal society with onerous legal restrictions on its Jewish population. In his art, Rubinstein opposed both the Romantic nationalism of his Russian contemporaries and the growing cult of Wagner. Instead he often stressed biblical themes such as in his various “spiritual operas,” including Sulamith (1883), The Maccabees (1884), Moses (1894), and Christus (1895). In the end, his oft-quoted self-evaluation came to summarize his estrangement from a musical world that increasingly insisted on assigning composers to national and religious categories: “To the Jews I am a Christian. To the Christians – a Jew. To the Russians I am a German, and to the Germans – a Russian. For the classicists I am a musical innovator, and for the musical innovators I am an artistic reactionary and so on. The conclusion: I am neither fish nor fowl, in essence a pitiful creature!”8

In contrast to Rubinstein's restless performance career, colorful personality, and complex personal identity, Alkan lived his entire life as a traditionally observant religious Jew who abandoned public performance. He rarely, if ever, left his native Paris, and for much of his later life lived as an enigmatic recluse. A graduate of the Paris Conservatoire, he emerged early on as one of the great pianistic talents of French musical life. He became close friends with Chopin, Liszt, and George Sand. Though he vanished from public view, Alkan produced a large body of technically demanding piano music that sits comfortably alongside that of Liszt and Chopin as some of the most expressive, technically forbidding piano music of the Romantic era. Alkan's piety surfaced in his work with the main Paris synagogue and his compositional efforts to set both the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Bible to music. He framed his Jewishness nearly exclusively in terms of religious referents, chiefly in the form of synagogue texts – and occasionally liturgical melodies – transposed for voice and piano or integrated into biblically themed works such as his “By the Rivers of Babylon” (1859).9

The notion of re-harmonizing Jewish and Christian sonorities took a much different form in the music of nineteenth-century Jewish cantor-composers, who reshaped the Jewish liturgical repertoire to reflect the contemporary norms of Romantic style and Christian liturgical music. Chief among these was Salomon Sulzer (1804–90), “father of the modern cantorate,” whose career as a prominent cantor in Vienna stretched from the 1820s to 1880s. In his compendium Schir Zion, he created an enormously influential style of modern liturgy that amounted to a wholesale aesthetic reformation of Jewish synagogue music.10 Sulzer trimmed Jewish liturgical music of its perceived Oriental characteristics, such as melisma, extended recitative, modal character, and flowing meter, in favor of a style that conformed more to Christian church hymnody. He adopted fixed meters, four-part choral singing, and conventional European tonal practices for the arrangements of Hebrew-language prayers. His talents as a composer and cantorial soloist earned the respect, praise, and curiosity of the leading critics and composers of his day. Outside the synagogue, Sulzer's career also epitomized the other growing artistic links between central European cantors and the world of modern classical music. He was a well-respected vocal interpreter of Schubert's Lieder and served as professor at the Imperial Conservatory in Vienna.11

Sulzer's pattern of liturgical reform spread gradually throughout European Jewish synagogue music, particularly in larger urban communities identified with the nascent Jewish Reform religious movement. Across England, France, and the Netherlands, cantors introduced four-part chorale-style singing, organ instrumental accompaniment, and standard Western harmonic practices.12 Under the leadership of Cantor Samuel Naumbourg (1817–80), the Paris synagogue became a second major center for liturgical composition, and the composers Alkan, Halévy, and Meyerbeer all contributed choral settings of liturgical texts for use there.13 So too in Berlin, where Louis Lewandowski (1821–94) emerged as a formidable choral composer, putting his German conservatory training to use in building a repertoire of psalm settings that became staples of synagogue music in his generation and long after.14 The transformation of oral traditions into textualized repertoires through musical notation had a profound effect on the self-understanding of Jewish communities in nineteenth-century Europe. This was equally true of the Sephardic religious communities of France, Germany, and Austria, which followed the same pattern of assimilating orally based liturgical traditions into the stylistic conventions of the surrounding European musical culture.15

Alongside this Jewish recasting of cantorial music in terms of modern European aesthetics, nineteenth-century Christian composers turned to the Jewish musical corpus in search of source material with which to color biblical-themed works and other exotic Oriental fantasies. This phenomenon appeared most strikingly in the Russian Empire, where from Mikhail Glinka onwards, composers transcribed contemporary Jewish melodies for use in their compositions, frequently titled “Hebrew Melody” or “Hebrew Song.” These typically elegiac compositions by the likes of Rimskii-Korsakov, Balakirev, Mussorgsky, and others evoked a lost Hebraic melos from antiquity sometimes contrasted implicitly with a calcified or degenerated present-day Jewish folklore.16 Though this philo-Semitic trend of Jewish folkloric melodies set by Christian composers continued on in later compositions such as “Chanson hébraïque” (1910) and “Deux mélodies hébraïques” (1914) by Maurice Ravel (1875–1937), a key turning point emerged with the 1881 “Kol Nidrei” of Max Bruch (1838–1920). Bruch's setting of the traditional Yom Kippur prayer for cello and piano, inspired by his musical contacts with the Jewish communities of Berlin and Liverpool, achieved tremendous popularity as a concert piece and aural symbol of Jewish identity (so much so that Bruch, a German Protestant, has often been erroneously claimed as a Jew by birth). Its continued presence in the classical repertoire speaks to its potent appeal as a document of Jewish liturgical tradition refashioned as modern art music.

Even as Romanticism prompted composers to experiment with elements of Jewish musical folklore, the idea of a distinctively Jewish strain of modern art music did not appear until the end of the nineteenth century. It would take two further developments for the notion of “Jewish music” to emerge in European discourse: the rise of Jewish ethnic nationalism and a hardening of the racial lines in European thought. A decisive factor in this process was the appearance of the explosive modern anti-Semitic musical myth propagated by Richard Wagner. In his 1850 essay “Das Judentum in der Musik,” published anonymously in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, then again under his own name in 1869, Wagner presented a brutally racist diatribe against the alien Jewish presence in the world of European music and the other arts. For decades before Wagner's pamphlet the concentration of acculturated Jews in the classical music profession as both performers and composers – and the ambiguous relationship between composition and performance as ideational poles in the Romantic artistic imagination – had existed as a locus for anti-Jewish ideologies. So too did the medieval “music libel” of Jewish musicians as noise polluters of Christian harmony persist into the modern era.17 Wagner amplified these preexisting negative tropes, blending them with Romantic nationalism and modern racism to craft a new ideology of full-blown musical anti-Semitism.18 For Wagner, Jewish racial identity was inescapable in music. Further, since diasporic Jews possessed no common national language or authentic folk culture of their own from which to generate original art, they were doomed to be imitators, manipulators, and defilers of German, French, and other European music. He thus condemned Mendelssohn and Meyerbeer for their Judaic limitations as composers and mocked the idea of Jewish music.

Wagner's essay was not the only such ideological expression regarding the links between Jews and art music to appear at mid-century. Franz Liszt's The Gypsies and Their Music in Hungary (1859; rev. ed. 1881), though not entirely written by the composer himself, presented a similar tranche of anti-Semitic stereotypes.19 In Russia, England, and elsewhere, influential writers also proffered elaborated theories about Jewish musical talent.20 Popular English novels such as Benjamin Disraeli's Coningsby (1844), Elizabeth Sara Sheppard's Charles Auchester (1849), and George Eliot's Daniel Deronda (1876) further engrained the cliché of an innate Jewish musical talent in the Western imagination – but with a significant difference.21 Almost a mirror image of their anti-Semitic counterparts, these philo-Semitic theories often ascribed to Jewish composers a discernible Semitic character reflected in their compositions by linearity, ornamentation, or lyricism and a conversant weakness in terms of larger musical thematism.22 Yet for all the parallels and overlap between the various nineteenth-century anti-Semitic and philo-Semitic theories of Jewish musicality, Wagner's essay stood out for its lasting influence on European musical thought. Buoyed by Wagner's towering reputation as a composer and cultural figure, “Das Judentum in der Musik” cast a long shadow over the critical reputations and public receptions of multiple generations of European Jewish composers, notably Mendelssohn and Mahler.23 It also distinctly impacted the ways later Jewish composers attempting to forge a national style of Jewish art music understood their own relationship to the Western tradition.24

Aural emancipations: Renaissance and Modernisms, 1900–1917

After 1900, a new generation of Jewish musicians came of age in European musical life. With urbanization and secularization making ever-faster inroads into central and eastern Europe, the pattern of Jewish demographic overrepresentation in classical music only intensified. Jewish residents of Vienna were three times more likely to study music than non-Jews, while Russian Jews constituted roughly one out of every three conservatory-trained musicians in their country. Indeed, the conservatories of Vienna, St. Petersburg, Moscow, Berlin, Odessa, and other European cities became extraordinary breeding grounds for a generation of Jewish violinists, pianists, and other musicians who would predominate in the concert world of the twentieth century.25 Of particular note is the impressive roster of violin prodigies that emerged from the St. Petersburg Conservatory studio of Hungarian-born violinist and master pedagogue Leopold Auer (1845–1930), himself a student of Joachim. Auer's pupils included the likes of virtuosos Jascha Heifetz (1901–87), Mischa Elman (1891–1967), Nathan Milstein (1903–92), and Efrem Zimbalist (1890–1985). The careers of European Jewish virtuosos would in many respects parallel those of their nineteenth-century forebears. Highly mobile individuals in an age of war, revolution, and emigration, these musical celebrities came to be heralded as the international torchbearers for the cultural prestige of classical music and objects of affection for European audiences nostalgic for the vanishing world of the nineteenth century. So too would Jews continue to play a significant role in Western art music as publishers, critics, and scholars.26

The post-1900 generation of European Jewish composers was the first to appear on the historical stage with an intensely ideological, self-conscious determination to break with the past. This revolutionary ethos took two distinct forms. In the Russian Empire, an explicitly Jewish national renaissance movement centered in the Russian Empire rejected the putative absorption of Jewish musicians into a universalist European culture. These Jewish nationalist composers called for the renewal of Jewish national identity through freeing a previously silenced Jewish voice within Western music. At virtually the same moment, a looser central European avant-garde school appeared, comprised of composers who aspired to emancipate music itself from the aesthetic conventions of nineteenth-century realism in favor of an abstract modernism. What linked these two cohorts – along with those Jewish composers who bucked both trends – was an acute awareness of the passage of European Jewry into a new historical era. In response to tremendous societal change, modernist nationalists and cosmopolitan modernists alike called for an immediate radical reconstruction of Jewish identity in music. Yet both found that the long shadows of the Jewish past continued to define Jewish identity in Western music.

In the Russian Empire, a number of conservatory-trained Jewish composers experimented with Jewish musical ethnography in the late 1890s and early 1900s. Inspired by the new spirit of secular Jewish nationalism, emboldened by the Russian, Finnish, and other national schools, and encouraged by Russian musical mentors such as Rimskii-Korsakov, Balakirev, and the critic Vladimir Stasov, these composers began to collect and arrange Yiddish and Hebrew folk songs, traditional liturgical selections, Hasidic spiritual chants, and klezmer dance tunes.27 The key figure in this process was the Russian critic, ethnographer, and composer Joel (Iulii Dmitrevich) Engel (1868–1927). A Moscow Conservatory graduate, Engel presented a concert of Yiddish folk song arrangements in 1900 in Moscow that subsequently came to be regarded by many as the first-ever concert of Jewish art music. With the stature that came as one of Russia's leading music critics, Engel went on to advocate a Jewish national movement in classical music. He also published several influential song collections, and pioneered the use of early sound recording technology to document shtetl musical traditions in situ.28

Engel was joined in his efforts by a group of young composers, among them Mikhail Gnesin (1883–1957), Solomon Rosowsky (1878–1962), Lazare Saminsky (1882–1959), and Moyshe Milner (1886–1953), who had all met in Rimskii-Korsakov's composition class at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. In 1908, these St. Petersburg musicians launched the Society for Jewish Folk Music (Obshchestvo evreiskoi narodnoi muzyki). The new organization pursued a campaign on multiple fronts to encourage explicitly Jewish art music composition, to promote Jewish cultural nationalism among Russian Jewish conservatory musicians, and to define through research and polemical debate the legitimate paternity and national contours of Jewish music. Engel was named the organization's first honorary member, and in 1913 he opened a branch in Moscow.29

In the decade after 1908, the Society for Jewish Folk Music produced nearly 1,000 concerts across Russia and eastern Europe, launched branches in many cities, and issued a very popular songbook for schools and homes. Most crucially, they published a number of compositions by multiple composers that used Yiddish and Hebrew folk songs and klezmer instrumental dance melodies in vocal arrangements and small chamber music formats. Many of these early compositions reflected the tenets of Russian Romanticism and common-practice harmonies. The Russian influence could also be detected in performance practices and other extra-musical referents that signaled Jewish music to be simultaneously a recovered Jewish national voice, an enriching contribution to European culture, and a coveted object of Russian imperial patrimony. Building on Russian Orientalism and European antiquarianism, the Russian Jewish School also pioneered new techniques of Jewish auto-exoticism. Composers such as Engel, Ephraim Shkliar, Rosowsky, and Leo Zeitlin (1884–1930) pioneered a genre of musical miniatures that sought to preserve the folkloric qualities of ethnographically sourced melodies in the lead instrumental voices with modern harmonic accompaniments and novel instrumentations.30 Just as in other spheres of modern Jewish culture, many composers also imbibed the influence of pan-European modernism and French Impressionism. Composers such as Joseph Achron (1886–1943), Gnesin, and Alexander Krein (1883–1951) married the chromaticist experiments, intense tonal lyricism, and extended harmonies of modernist composers like Scriabin and Debussy to Jewish scales and intonational gestures.31 They also moved easily back and forth between the larger European artistic milieu and the world of modern Jewish culture. It was not uncommon for these composers to set both Russian Symbolist poetry and modern Hebrew and Yiddish lyrics to music. They thus positioned Jewish art music simultaneously as one genre within a larger universe of Jewish cultural expression and as a stream within modern Russian and European art music.

The young Jewish composers of late Tsarist Russia balanced an attraction to the new universalist aesthetics of modernist abstraction with a particularistic commitment to representing Jewish identity in music. A similar phenomenon appeared in the Sephardic musical realm in the form of the Alexandrian-born Turkish-Jewish composer Alberto Hemsi, who collected and arranged Sephardic Jewish song texts and melodies in his landmark collection Coplas Sefardies (1932–73). By contrast, the central European Jewish exponents of modernism dispensed with all Romantic folklorism and realism alike in favor of a new avant-garde ideology of tonal experimentation and formal abstraction. In the eyes of composers such as Gustav Mahler (1860–1911) and Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951), modern art demanded that artists transcend ethnic or religious parochialisms. Yet this utopian goal proved difficult to achieve in practice.

Born in the Austrian Bohemian hinterlands, Mahler rose to become arguably the leading conductor and symphonist of the fin-de-siècle. As a composer, he drew acclaim for his music's psychological intensity, ruminative beauty, and tonal complexity. Yet he also faced a series of devastating crises in his personal life, including illness and infidelity. He additionally possessed a vexed identity as an ambivalent convert to Christianity and an ongoing target of anti-Semitism. His aching sense of inner conflict, emotional displacement, and powerful longing for transcendence permeated his deeply lyrical, expressionist style. Scholars have differed about the presence of explicitly Jewish influences in his brooding modernist textures. Yet there is little disagreement that Mahler's life and art epitomized the mixture of triumph and tragedy, inclusion and exclusion that characterized the larger experience of generations of Jews in the fin-de-siècle world of European classical music.32 He summed up his own fate with his famous remark: “I am thrice homeless, as a native of Bohemia in Austria, as an Austrian among Germans, and as a Jew throughout the world. Everywhere an intruder, never welcomed.”

Similarly, Schoenberg launched a musical revolution over the course of 1908 and 1909 with works that stretched tonality outwards in pursuit of what he termed the “emancipation of dissonance.” An Austrian Jew who converted to German Lutheranism, Schoenberg rejected realism for extreme chromaticism, unconventional rhythms, and eventually, the serialist approach of tone-rows. Paradoxically, Schoenberg extolled his anti-parochial aesthetic universalism as a German cultural achievement. This complicated utopianism represented a dialectical response to the dilemmas of Jewishness in art music. Yet it did not prevent European anti-Semitic ideologues from collapsing Jewishness and modernism into a single essentialist view of Jews as arch-modernists when it came to music. This anti-Semitic attack on modernism grew even stronger after the rise of Nazism. This prompted Schoenberg to publicly renounce his Germanism and Christianity and formally re-embrace Jewish religion, politics, and eventually musical thematics in his own idiosyncratic way.33