Introduction

In recent years, New Testament scholarship has increasingly recognised the value of studying ancient texts as physical artefacts.Footnote 1 One of the most widely discussed features of early Christian manuscripts is their distinctive use of special abbreviated forms called nomina sacra.Footnote 2 These words are usually contracted to the first and last letters of their inflected forms, with a horizontal stroke written above the remaining letters,Footnote 3 which apparently functions to depict visually their unique significance for Christian communities.Footnote 4

Recent work has tended to focus on the four earliest examples of this phenomenon – Jesus, Christ, Lord and God – with comparatively little attention devoted to the term ‘spirit’ (πνεῦμα), even though it is also attested as a nomen sacrum in many of our earliest manuscripts.Footnote 5 This essay seeks to address this imbalance by exploring how πνεῦμα language is rendered in NT Papyrus 46 (P. Chester Beatty ii / P. Mich. Inv. 6238).Footnote 6

My analysis of all the occurrences of πνεῦμα and its derivatives in P46 reveals considerable irregularity, both in form and meaning. Against expectations, at several points πνεῦμα is written out in full (plene) to signify the divine Spirit, and in numerous places nomina sacra are used to clearly reference something other than the divine Spirit. This discovery destabilises the assumption that we can access the scribe's interpretive decisions about the meaning of πνεῦμα merely by identifying where nomina sacra do and do not occur.Footnote 7 Moreover, since scribal practices are inextricably linked to larger socio-cultural realities, the idiosyncratic treatment of πνεῦμα in P46 may offer a physical illustration of broader theological ambiguities among early Christians around the person and work of the Holy Spirit.

In what follows, I will: (1) provide a brief orientation to P46, (2) offer an analysis of all of the appearances of πνεῦμα language in P46, and (3) consider how the scribe's treatment of this language may reflect second- and third-century theological developments and shed light on the complex relationship between manuscripts and their socio-cultural contexts.

1. Orientation to P46

Dated to about 200 ce,Footnote 8 P46 is the earliest extant collection of Paul's epistles, and thus provides an exceptional window into early Christian scribal practices. It is one of only a handful of early Christian manuscripts that preserve the word πνεῦμα and its derivatives both as nomina sacra and written out in full.Footnote 9 As such, it affords a unique lens on emerging scribal conventions surrounding this term, preserving a snapshot of developing patterns while they were still in flux.

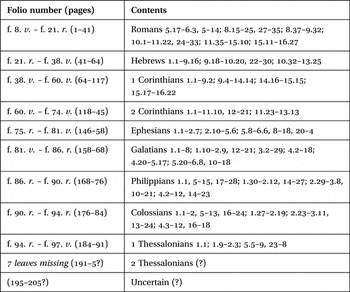

As it stands,Footnote 10 P46 contains most of the epistles traditionally ascribed to Paul, including Hebrews, but excluding 2 Thessalonians, Philemon and the Pastorals (see Table 1).Footnote 11

Table 1. Contents of P46

Internal evidence indicates that P46 was produced by a trained scribe from an early, excellent exemplar. The manuscript is written in a good scribal hand and, aside from some later corrections and minor additions, the same hand is used throughout.Footnote 12 That the scribe was a professional is indicated by the stichoi notations at the end of several books (e.g. Romans),Footnote 13 which were used to mark the number of lines copied in order to calculate commensurate pay (see Figure 1).Footnote 14

Figure 1. Stichometric note at the end of Romans (f. 21. r.)

In spite of numerous errors that may seem to cast doubt upon his grammatical facility or his ability to understand the sense of the text he was copying,Footnote 15 several features of the manuscript indicate that the scribe of P46 was not just a passive copyist, but an active reader and interpreter of the text. First, at least nine times the scribe corrected himself immediately in the act of writing (in scribendo), which suggests he had a certain awareness about the text's meaning.Footnote 16 Second, in a number of places, scribal blunders and harmonisations seem to occur due to the influence of context.Footnote 17 Third, at several points in the manuscript, the scribe adds extra spaces to indicate sense divisions (as occurs, for example, between the last word of Gal 1.5, ἀμήν, and θαυμάζω, the first word of Gal 1.6) (see Figure 2).Footnote 18

Figure 2. Sense division in Gal 1.5–6 (f. 81. r.)

Although Royse argues that the scribe of P46 ‘seems to have difficulty understanding the abbreviations for nomina sacra that stood in his Vorlage, and accordingly often introduces an impossible form’,Footnote 19 it is important not to exaggerate the scribe's incompetence. As we shall see, when we take into account the terms consistently abbreviated, the scribe's total rate of error is actually quite low.Footnote 20 Moreover, Royse's assessment assumes that the nomina sacra copied by the scribe in fact appeared in his Vorlage. Since it is such an early manuscript, this may not be the case, especially when it comes to nomina sacra for πνεῦμα.Footnote 21 In fact, the inconsistent use of nomina sacra for πνεῦμα language in P46 may indicate that the scribe was working from an exemplar where such forms were often, or always, written out in full, thereby requiring that he make interpretive decisions about how to copy these terms case by case.Footnote 22

If so, this would fit with Kim Haines-Eitzen's characterisation of early Christian scribes not only as readers and copiers but also as ‘users’.Footnote 23 For Haines-Eitzen, these scribes-as-users were theologically invested in the texts they (re)produced, could manipulate them, and, therefore, wielded a certain power over the texts they copied.Footnote 24 For the purposes of our study, this possibility raises two questions: to what extent was the scribe of P46 engaged interpretively and invested theologically in the copying of πνεῦμα language? And, in what ways might his use or non-use of nomina sacra for such language relate to wider second- and third-century understandings of the Holy Spirit? Addressing these matters requires a closer look at the text.

2. Nomina sacra and πνεῦμα Language in P46

In what remains of P46, the noun πνεῦμα, the adjective πνευματικός and the adverb πνευματικῶς are clearly visible some 132 times.Footnote 25 Of these occurrences, 36 are written plene and the rest as nomina sacra. Breaking these totals down further, πνεῦμα appears in the manuscript 109 times, where it is written 19 times in full and 90 times as a nomen sacrum. The adjective πνευματικός appears 22 times, and is written 17 times in full and 5 times as a nomen sacrum. The adverbial form πνευματικῶς occurs only once, and is written as a nomen sacrum (see Table 2).

Table 2. ‘Spirit’ terminology in P46

That these terms appear in P46 both as nomina sacra and in full begs the question: is there any interpretive significance to the scribe's usage of these forms? One way to approach this question is to look for any discernible patterns in how these forms are used in the text. Given the general pattern in the earliest Christian manuscripts of using nomina sacra for the divine names or titles ‘Lord’, ‘Jesus’, ‘Christ’ and ‘God,’ it might seem reasonable to begin with the assumption that the different forms of πνεῦμα in P46 signal a distinction between the divine Spirit and any other spirit, be it a human spirit, something characteristically spirit, an evil spirit or the wind.Footnote 26 If this were the case, one would expect to find nomina sacra only in passages that clearly designate the divine Spirit, and the full form in places that refer to any other type of spirit.

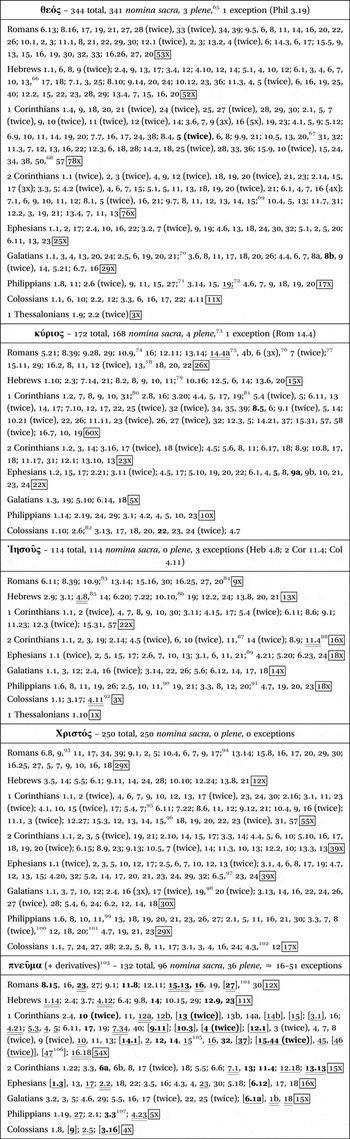

Curiously, however, this is not always the case. While the scribal pattern of using nomina sacra to distinguish between sacred and non-sacred referents exhibits a high degree of stability for θεός, κύριος, Ἰησοῦς and Χριστός, the same cannot be said for πνεῦμα and its derivatives. Close inspection of these terms clearly proves the point (see Table 3).Footnote 27

Table 3. Patterns in the earliest nomina sacra in P46a

*Places where nomina sacra are used with a ‘non-sacral’ (i.e. ‘profane’) referent, or where plene forms appear with a ‘sacral’ referent.

aFor a complete list of all verse references where these forms appear in P46, consult the Appendix.

bBy my count, there are at least 16 clear instances where the form of πνεῦμα (plene or nomen sacrum) does not match the ‘sacrality’ of ‘non-sacrality’ of the referent. There are an additional 13 debatable instances for the noun and 22 debatable instances for the adjective and adverb. For the sake of comparison, Paap indicates 48 exceptions, that is, 25 plene forms used in a ‘sacral’ sense and 23 nomina sacra used in a ‘profane’ sense (Nomina Sacra, 8). Unlike Paap (and also Ebojo, who tabulates 40 exceptions (10 ‘sacral’ plene forms and 30 ‘non-sacral’ nomina sacra) in ‘A Scribe and his Manuscript’, 352), I have cautiously provided only a range of possible exceptions in this figure, being careful not to presume a perspicacious understanding of all the texts in question and whether or not they refer to the divine Spirit (determining the referential ‘sacrality’ of the adjective and adverb is particularly nettlesome). On this issue, see n. 35, the notes to Tables 5–7, and nn. 103 and 104 in the Appendix.

In P46, θεός appears 344 times and is always rendered as a nomen sacrum, with only three exceptions: it is written plene twice in 1 Cor 8.5 (f. 47. v.) and once in Gal 4.8 (f. 84. r.).Footnote 28 In all three cases the full form is plural and designates false gods (see Table 4).Footnote 29

Table 4. Θεός written plene in P46*

*Transcriptions in this and the remaining figures are drawn from the 2009 Accordance electronic version of Comfort and Barrett, Text (Portland, OR: OakTree Software, 2009), which I have checked against the facsimile edition and digital images of P46 to ensure accuracy. The transcriptions do not attempt to reproduce exactly the line breaks and spacing of the manuscript. Translations are my own.

On the flip side, in the 341 places where θεός is written as a nomen sacrum, it is always singular and refers to the true God. The only exception is Phil 3.9, where the nomen sacrum is used to describe those whose ‘god is the stomach’ (ⲟ ⲑⲥ ⲏ ⲕⲟⲓⲗⲓⲁ, f. 89. r.).Footnote 30 Therefore, out of 344 occurrences of θεός in P46, the 3 that are written in full are always plural and consistently indicate false gods, while all other occurrences are nomina sacra and refer to the one true God, with only a single exception.

The pattern for κύριος is equally stable. When it appears as a nomen sacrum (172 times) it is always used in a sacral sense; when it appears plene (4 times) it is always plural and is used to refer either to false ‘lords’ (1 Cor 8.5; see Table 4) or to human ‘lords’ (i.e. masters: ⲧⲟⲓⲥ ⲕⲩⲣⲓⲟⲓⲥ ⲕⲁⲧⲁ ⲥⲁⲣⲕⲁ, Eph 6.5, 9a; Col 3.22).Footnote 31 The only possible exception is Rom 14.4, where κύριος with a non-sacral referent is abbreviated to describe how each person must stand or fall before ‘their own lord’ (ⲧⲱ ⲓⲇⲓⲱ ⲕⲱ, f. 17. r.).

The nomina sacra for Ἰησοῦς are also very consistent. Of its 114 occurrences in P46, Ἰησοῦς always appears as a nomen sacrum. There are only three places where the use of the nomen sacrum seems inappropriate: Heb 4.8 (f. 24. r.), which uses the form for the OT figure ‘Joshua’;Footnote 32 Col 4.11 (f. 93. v.), where it refers to one of Paul's fellow workers, a certain ‘Jesus, called Justus’ (ⲕⲁⲓ ⲓⲏⲥ ⲟ ⲗⲉⲅⲟⲙⲉⲛⲟⲥ ⲓ̈ⲟⲩⲥⲧⲟⲥ); and 2 Cor 11.4 (f. 71. v.), in which Paul cautions the Corinthian church against any who might proclaim ‘another Jesus’ (ⲁⲗⲗⲟⲛ ⲓⲏⲛ). Interestingly, in the latter half of 2 Cor 11.4 Paul goes on to admonish the Corinthians not to accept a ‘different spirit’, which is written out plene (ⲡⲛⲉⲩⲙⲁ ⲉⲧⲉⲣⲟⲛ).

Finally, Χριστός exhibits complete consistency, which we might expect given the restricted meaning of the word in the NT.Footnote 33 It appears 250 times in the manuscript, and always appropriately as a nomen sacrum. Thus, the four earliest nomina sacra – θεός, κύριος, Ἰησοῦς and Χριστός – display considerable consistency in P46. With few exceptions, they are used in a ‘sacred’ sense, and are only written in full to distinguish between the true God or Lord and false gods or lords. Although the abbreviated forms of these nomina sacra vary considerably,Footnote 34 their meanings are remarkably stable.

By contrast, the scribe's usage of nomina sacra for πνεῦμα and its derivatives is far less predictable. By my count, there are at least 16, and possibly as many as 51, places in P46 where the scribe departs from the pattern established by θεός, κύριος, Ἰησοῦς and Χριστός (see Table 3). In other words, the scribe does not always use nomina sacra to designate the divine Spirit, nor are other kinds of spirits always written out in full.Footnote 35 A brief look at just a few of these examples will demonstrate the point. We will begin with the noun, and then look at the adjective and adverbial forms of πνεῦμα.

2.1 Noun: πνεῦμα

a. Πνεῦμα plene to refer to the divine Spirit

First: the noun. Of the 19 times πνεῦμα is written in full, the divine Spirit is clearly in view in at least 4 places: Rom 8.23; 15.13; 15.16; and 2 Cor 13.13.Footnote 36 Rom 15.13 and 15.16 are especially noteworthy. In both of these cases, πνεῦμα is directly linked to ἅγιος, and yet is still written in full (see Table 5).

Table 5. Plene forms of πνεῦμα to refer to the divine Spirit

aⲉⲗⲁⲃ]ⲉⲧⲉ ⲡⲛⲉⲩⲙⲁ ⲩⲟⲑⲉⲥⲓⲁⲥ, ‘you received (the/a) S/spirit of adoption’ (f. 11. v.). English translations with an uppercase ‘Spirit’ include: CEV, ESV, GNT, KJV, NCV, NET, NIV, NLT; those with a lowercase ‘spirit’ include: NASB (with a note that recognises the alternative reading), NRSV.

bⲇⲓⲁ ⲡⲛⲉⲩⲙⲁⲧⲟⲥ ⲁⲓⲱⲛⲓⲟⲩ, ‘through the eternal S/spirit (f. 30. v.). ‘Spirit’: ESV, GNT, KJV, NASB (while noting the alternative reading), NCV (with a note explaining other interpretive options), NET, NIV, NLT, NRSV; ‘spirit’: CEV (‘eternal and spiritual sacrifice’), cf. Comfort, Encountering, 237.

cⲏⲙⲉⲓⲛ ⲅⲁⲣ ⲁⲡⲉⲕⲁⲗⲩⲯⲉⲛ ⲟ ⲑⲥ ⲇⲓⲁ ⲧⲟⲩ ⲡⲛⲉⲩⲙⲁⲧ̣[ⲟⲥ][ⲧⲟ] ⲅⲁⲣ ⲡⲛⲉⲩⲙⲁ ⲡⲁⲛⲧⲁ ⲉⲣⲁⲩⲛ̣[ⲁ][ⲕ]ⲁⲓ ‘For God has revealed to us through the S/spirit, for the S/spirit searches everything’ (f. 30. v.). ‘Spirit’: CEV, ESV, GNT, KJV, NASB, NCV, NET, NIV, NLT, NRSV, cf. Fee, Presence, 99–100; ‘spirit’: Comfort, Encountering, 236 (displaying, perhaps, exegetical overreliance on the plene forms in P46).

dⲟⲩⲅⲣⲁⲙⲙⲁⲧⲟⲥ ⲁⲗⲗⲁ ⲡⲛⲉⲩⲙⲁⲧⲟⲥ, ‘not of letter, but of (the) S/spirit’ (f. 63. v.). ‘Spirit’: CEV, ESV, GNT, NCV, NET, NIV, NLT, cf. Fee, Presence, 304–7; ‘spirit’: KJV, NRSV, cf. Comfort, Encountering, 236–7.

eⲟⲓ ⲉⲛ ⲡⲛⲉⲩⲙⲁⲧⲓ ⲗⲁⲧⲣⲉⲩⲟⲛⲧⲉⲥ, ‘the ones who worship in/by (the) S/spirit’ (f. 88. v.). Since this is a variant reading (with most manuscripts reading ‘Spirit of God’, see NA28), comparison with modern translations is unhelpful (but see the brief discussion of this text in Comfort, Encountering, 237).

If, as it is usually asserted, the purpose of nomina sacra is to mark off names and titles for special reverence,Footnote 37 it seems strange that the scribe fails to employ them in these passages. What might account for this? One explanation is scribal oversight. If the scribe's exemplar had πνεῦμα written in full at these spots, it is conceivable that the scribe simply neglected to convert them to the appropriate nomina sacra, especially considering that the scribe of P46 was not always particularly careful.Footnote 38

Or perhaps the scribe did not feel a need to write πνεῦμα as a nomen sacrum in these cases since the context makes its referent obvious. However, an investigation of other places in the manuscript where an accompanying adjective clearly designates πνεῦμα as the divine Spirit undermines this hypothesis. Although in Heb 9.14 πνεῦμα is written in full when accompanied by αἰώνιος (ⲡⲛⲉⲩⲙⲁⲧⲟⲥ ⲁⲓⲱⲛⲓⲟⲩ, ‘the eternal S/spirit’), it appears as a nomen sacrum everywhere else in P46 where it is connected with an adjective clearly designating the divine Spirit. Nine other verses in P46 refer to the ‘Holy Spirit’, and they always use the nomen sacrum form.Footnote 39 The same can be said of the phrase ‘Spirit of God’, which occurs 6 times in the manuscript,Footnote 40 and ‘Spirit of Grace’, which appears as a nomen sacrum in Heb 10.29. Thus, the use of the plene form of πνεῦμα with ἅγιος in Rom 15.13 and Rom 15.16 represents an exception to the norm.

It may be significant that several of the aberrations listed in Table 5 occur towards the end of their respective letters. In his careful analysis of P46, James Royse shows that ‘P46's performance varied considerably from book to book and from section to section’ and is demonstrably less accurate towards the end of individual books.Footnote 41 While neglecting to write πνεῦμα as a nomen sacrum may not technically constitute a scribal error, perhaps it was an unintentional scribal blunder due to exhaustion. However, such rapid deterioration of scribal accuracy is more evident in Hebrews and 1 Corinthians than it is in Romans, where it occurs less dramatically, while the error rate of 2 Corinthians, conversely, remains relatively constant with actually a slight improvement in the latter third.Footnote 42 There does not seem to be any spatial reason that the scribe would seek to avoid abbreviating πνεῦμα in these texts,Footnote 43 and the presence of other nomina sacra nearby argues against any notion that writing them had grown tiresome; there are eight nomina sacra on the same page as Rom 15.13 and 16, including one for πνεῦμα θεοῦ at 15.19. Furthermore, the benediction of 2 Cor 13.13 includes nomina sacra for Lord, Jesus, Christ and God within the span of two lines, and πνεῦμα is abbreviated as nearby as 12.18, which appears on the verso of the same folio. Therefore, the unexpected forms of πνεῦμα in these passages resist easy explanation.

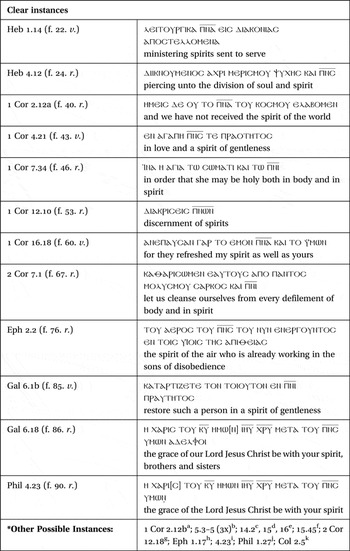

b. Πνεῦμα as a nomen sacrum to designate something other than the divine Spirit

Similar unpredictability surfaces in the scribe's copying of πνεῦμα as a nomen sacrum to designate something other than the divine Spirit. Of the 92 occurrences of πνεῦμα as a nomen sacrum, there are over a dozen cases in which the referent is clearly not the divine Spirit. Indeed, the scribe is comfortable employing the nomen sacrum to designate nearly the full range of meanings for πνεῦμα (see Table 6).

Table 6. Nomen sacrum forms of πνεῦμα not referring to the divine Spirit

aⲁⲗⲗⲁ ⲧⲟ ⲡⲛⲁ ⲧⲟ ⲉⲕ ⲧⲟⲩ ⲑⲩ, ‘but the S/spirit from God’ (f. 40. r.). ‘Spirit’: CEV, ESV, GNT, NASB, NCV, NET, NLT, NIV, NRSV; ‘spirit’: KJV, cf. the discussion and references in J. A. Fitzmyer, First Corinthians (AB 32; New Haven: Yale University, 2008) 181.

bⲉⲅⲱ ⲙⲉⲛ ⲅⲁⲣ ⲁⲡⲱⲛ ⲧⲱ ⲥⲱⲙⲁⲧⲓ ⲡⲁⲣⲱⲛ ⲇⲉ ⲧⲱ ⲡⲛⲓ … ⲥⲩⲛⲁⲭⲑⲉⲛ ⲧⲱⲛ ⲩ̈ⲙⲱⲛ ⲕⲁⲓ ⲧⲟⲩ ⲉⲙⲟⲩ ⲡⲛⲥ ⲥⲩⲛ ⲧⲏ ⲇⲩⲛⲁⲙⲉⲓ ⲧⲟⲩ ⲕⲩⲓⲏⲩ … ⲓⲛⲁ ⲧⲟ ⲡⲛⲁ ⲥⲱⲑⲏ ⲉⲛ ⲧⲏ ⲏⲙⲉⲣⲁ ⲧⲟⲩ ⲕⲩ, ‘for though I am absent in body, I am present in (the) S/spirit … 4when you are gathered and my S/spirit is present with the power of the Lord Jesus … 5in order that the/his S/spirit may be saved in the day of the Lord (f. 43. v.). Although nearly all modern translations take πνεῦμα in this passage to refer to the human spirit, the NLT interprets v. 3 as the divine Spirit (while noting the alternative reading). Interestingly, one of the editors for this translation was Philip Comfort; one wonders whether his own exegetical interpretation of nomina sacra in P46 exercised some influence on the translation at this point (cf. Comfort, ‘Light’). Virtually all modern translations interpret πνεῦμα in v. 4 as the human spirit, but Fee makes a case that it could also refer to the divine Spirit in a similar sense as v. 3; thus, he translates the two occurrences of πνεῦμα in 1 Cor 5.3–4 with the non-committal ‘S/spirit’, but the occurrence in 5.5 as ‘spirit’ (see his discussion in Presence, 121–7). Conversely, Fitzmyer (First Corinthians, 236–40) argues for ‘spirit’ in 5.3–4, but ‘Spirit’ in v. 5 (as in the Spirit present to the community), noting the absence of αὐτοῦ and citing as support several ancient and modern commentators.

cⲡⲛⲓ ⲇⲉ ⲗⲁⲗⲉⲓ ⲙⲩⲥⲧⲏⲣⲓⲁ, ‘but he speaks mysteries in the S/spirit (f. 55. r.). ‘Spirit’: CEV, ESV, GNT, NCV, NET, NIV, NLT (which notes the possibility of ‘in your spirit’), NRSV, cf. Fee, Presence, 217–18 (especially n. 525); ‘spirit’: KJV, NASB (‘in his spirit’). Note the presence of the definite article in some witnesses in the manuscript tradition (see NA28).

dⲡⲣⲟⲥⲉ]ⲩ̣ⲝ̣[ⲟⲙ]ⲁ̣[ⲓ] ⲧⲱ ⲡ̣ⲛ̣ⲓ̣, ‘I will pray in the/my S/spirit’ (only partially visible at the bottom of f. 55. v.). ‘Spirit’: (possibility noted in NLT), cf. Fee, Presence, 229–31; ‘spirit’: CEV, ESV, GNT, KJV, NASB, NCV, NET, NIV, NLT, NRSV.

eⲉⲩⲗⲟⲅⲏⲥⲏⲥ ⲡⲛⲓ, ‘bless by/with the S/spirit’ (f. 56. r.). ‘Spirit’: NIV (with no footnote), cf. Fee, Presence, 231; ‘spirit’: CEV (‘your spirit’), ESV (‘your spirit’), GNT (‘in spirit only’), KJV, NASB (‘in the spirit only’), NCV (‘your spirit’), NET (‘your spirit’), NLT, NRSV. Note the inclusion of the definite article in some manuscripts (see NA28).

fⲟ ⲉⲥⲭⲁⲧⲟⲥ ⲉⲓⲥ ⲡⲛⲁ ⲍⲱⲟⲡⲟⲓⲟⲩⲛ, ‘the last (Adam became) a life-giving S/spirit’ (f. 59. R.). ‘Spirit’: NLT, GNT; ‘spirit’: CEV, ESV, KJV, NASB, NCV, NET, NIV, NRSV, cf. Fee, Presence, 264–7.

gⲡⲛⲓ ⲡⲉⲣⲓⲉⲡⲁⲧⲏⲥⲁⲙⲉⲛ, ‘(did we not) conduct ourselves with/by the (same) S/spirit’ (f. 74. r.). ‘Spirit’: NIV, cf. Fee, Presence, 357–9; ‘spirit’: CEV, ESV, GNT, KJV, NASB (while noting the alternate reading), NCV, NLT, NRSV.

hⲡⲛⲁ ⲥⲟⲫⲓⲁⲥ ⲕⲁⲓ ⲁⲡⲟⲕⲁⲗⲩⲯⲉⲱⲥ, ‘a/the S/spirit of wisdom and revelation’ (f. 75. v.). ‘Spirit’: CEV, ESV, GNT, NIV (noting the possibility of ‘spirit’), cf. Fee, Presence, 674–5; ‘spirit’: KJV, NASB, NCV, NET, NLT (noting the possibility of ‘Spirit’), NRSV.

iⲁ̣ⲛⲁⲛⲉⲟⲩⲥⲑⲉ ⲇⲉ ⲧⲱ ⲡⲛⲓ ⲧⲟⲩ ⲛⲟⲟⲥ ⲩ̈ⲙⲱⲛ, ‘and be renewed in the S/spirit of your mind’ (f. 78. v.). ‘Spirit’: CEV, NLT; ‘spirit’: ESV, KJV, NASB, NET, NIV (‘attitude of your minds’), NRSV; cf. Fee, Presence, 709–12, who translates πνεῦμα as ‘spirit/Spirit’, suggesting a possible analogy with 1 Cor 14.15, where Paul refers to his human spirit as the place where the Holy Spirit prays.

jⲥⲧⲏⲕⲉⲧⲉ ⲉ[ⲛ ⲉⲛⲓ] ⲡⲛⲓ, ‘you stand firm in [one] S/spirit’ (f. 87. r.). ‘Spirit’: NIV (noting the alternative reading), cf. Fee, Presence, 743–6; ‘spirit’: CEV, ESV, GNT, KJV, NASB, NET, NLT, NRSV.

kⲧⲱ ⲡⲛⲓ [ⲥⲩⲛ ⲩ̈ⲙⲉⲓⲛ ⲉⲓ]ⲙⲓ, ‘I am [with you] in (the) S/spirit’ (f. 91. v.). ‘Spirit’: Fee translates this verse with S/spirit in Presence, 645–6; ‘spirit’: CEV, ESV, GNT, KJV, NASB, NCV, NET, NIV, NLT, NRSV.

For example, several passages clearly utilise the nomen sacrum of πνεῦμα to designate angelic beings: Heb 1.14 refers to ‘ministering spirits;’ 1 Cor 12.10 describes the spiritual gift of ‘discernment of spirits’; and, most notably, Eph 2.2 uses a nomen sacrum to speak of an evil spirit, namely, ‘the spirit of the air who is already working in the sons of disobedience’. 1 Cor 2.12 may also fit within this category, when it contrasts the ‘spirit of the world’ with the ‘S/spirit from God’.

The scribe also uses nomina sacra to describe a particular attitude or state of being. For example, in 1 Cor 4.21, Paul queries, ‘Shall I come to you with a rod or in a spirit of love and gentleness?’, and in Gal 6.1 he counsels those who are spiritual to restore any who transgress in a ‘spirit of gentleness’. Both are nomina sacra.

At several points the nomen sacrum of πνεῦμα denotes the human spirit or the essence of one's presence, even in their physical absence. In 1 Cor 5.3–5 Paul invokes this meaning to emphasise his presence with the Corinthians when they assemble for church discipline, telling them, ‘though I am absent in body, I am present in spirit’. The scribe goes on to use the nomen sacrum to contrast the ‘flesh’ of a disobedient man, destined for destruction, with his ‘spirit’, which may still be saved. Similarly, 1 Cor 7.34 and 2 Cor 7.1 use the nomen sacrum form of πνεῦμα to contrast the body and the spirit of a human, and Eph 4.23 contrasts laying aside one's former way of life in order to ‘be renewed in the spirit of your mind’. Finally, 1 Cor 16.18 describes how Stephanus, Fortunatus and Achaicus ‘refreshed my spirit and yours’, and the letters to the Galatians and the Philippians close with benedictions that unambiguously employ nomina sacra to refer to the human spirit (Gal 6.18; Phil 4.23).

Thus, the evidence simply does not support the assumption that the scribe of P46 ‘signaled the Spirit's deity by writing pneuma as a nomen sacrum’, and ‘distinguished the divine spirit from any other spirit … by not writing these as a nomen sacrum’.Footnote 44 Even in passages where the text clearly contrasts the human spirit with the divine Spirit the scribe does not always mark this distinction with nomina sacra. As we have seen, the scribe sometimes writes πνεῦμα in full exactly at spots where the nomen sacrum would seem most appropriate, such as the ostensibly Trinitarian benediction in 2 Cor 13.13. Once again, these observations reinforce the conclusion that the scribe's use of nomina sacra for πνεῦμα language is idiosyncratic and inconsistent and, therefore, serves as an unreliable indicator of meaning.

2.2 Derivatives of πνεῦμα – Adjective: πνευματικός / Adverb: πνευματικῶς

The same could be said for the derivatives of πνεῦμα that appear in P46: the adjective πνευματικός and the adverb πνευματικῶς. The adjective πνευματικός occurs 22 times in P46, written 17 times in full and 5 times as a nomen sacrum. When it appears in full, πνευματικός is used to refer to such things as spiritual matters (Rom 15.27; 1 Cor 2.13), spiritual people (1 Cor 2.13; 1 Cor 14.37; Gal 6.1), spiritual blessings (1 Cor 9.11; Eph 1.3), spiritual forces (Eph 6.12), spiritual wisdom (Col 1.9), spiritual gifts (1 Cor 12.1; 14.1), spiritual food and drink (1 Cor 10.3–4), a spiritual rock (referring metaphorically to Christ, 1 Cor 10.4), the spiritual body (1 Cor 15.44) and spiritual songs (Col 3.16). In none of these cases is the plene form surprising. What is, perhaps, unexpected is the appearance of the adjective as a nomen sacrum in 5 places that do not seem to refer obviously to the divine Spirit: 1 Cor 2.15; 3.1; twice in 15.46, and again in 15.47 (see Table 7).Footnote 45

Table 7. Nomen sacrum forms of πνευματικός

Although there is apparently no difference in meaning between the ‘spiritual people’ in 1 Cor 2.13 and those mentioned in 2.15 and 3.1, in the former πνευματικός is written plene while later it appears twice as a nomen sacrum. In between these references, the scribe also represents the adverb πνευματικῶς with the exact same nomen sacrum as the adjective to characterise spiritual things as being ‘spiritually discerned’ (ⲡⲛⲥ ⲁⲛⲁⲕⲣⲓⲛⲉⲧⲁⲓ).

In 1 Cor 15 the manuscript exhibits similar irregularity. Even though πνευματικός is used identically in vv. 44 and 45 to refer to a ‘spiritual body’ in contrast to a ‘physical body’, in v. 44 it is written in full while in v. 45 it appears as a nomen sacrum. The scribe continues to use the nomen sacrum to designate the last Adam as a ‘life-giving πνεῦμα’ in v. 45, and then with the adjective twice in v. 46 to describe the ‘spiritual body’. Most interesting is the scribal insertion in v. 47, which appears in no other extant manuscripts of this verse. Instead of ‘the first man was from the earth, a man of dust; the second man is from heaven’, P46 adds πνευματικός as a nomen sacrum to the second line, thus reading ‘the second spiritual man is from heaven’. Here the scribe departs from his Vorlage, tampering with the tidy parallelism of the clauses, while also inserting a word that makes good sense of the meaning of the passage. This singular reading suggests at least three things about the scribe: (1) he was not mindlessly reproducing his exemplar, operating as a mere copyist, (2) he was aware of the meaning of the text and could alter it in a grammatically appropriate way, and (3) he not only felt free to insert a word, but was able to represent it accurately as a nomen sacrum.Footnote 46

And yet, even if this singular variant demonstrates a certain measure of scribal awareness and intentionality, it does not necessarily prove the same qualities were operative elsewhere in the manuscript. Nor does it buttress a case for scribal consistency. As we have seen, P46 regularly modulates between writing πνεῦμα in full and as a nomen sacrum with no consistent difference in meaning. In contrast to the stability that characterises the scribe's rendering of θεός, κύριος, Ἰησοῦς and Χριστός throughout P46 in forms appropriate to their meaning and context, the scribe's use of nomina sacra for πνεῦμα language displays comparative instability and unpredictability.

3. Πνεῦμα Language of P46 in its Social and Theological Location

So what does this suggest about the scribe's activity, function and social location? For Haines-Eitzen, the scribe's idiosyncratic application of nomina sacra in P46 ‘points toward a mode of transmission in which standardization and uniformity was not in existence’Footnote 47 and illustrates how textual modifications may reflect ‘the discursive contests of the second- and third-century church’.Footnote 48 In other words, fluctuating forms of πνεῦμα not only illustrate developing scribal patterns, but may also reflect second- and third-century theological ambiguities surrounding the Spirit.Footnote 49

Like the scribal inconsistency we have observed in P46, discussions of the Spirit from this period betray considerable diversity and fluidity. It is not until the end of the second century and into the third that theologies of the Spirit begin to receive more definitive doctrinal formulation, notably in the writings of Irenaeus of Lyons (Adversus haereses), Tertullian (Adversus Praxean) and Origen of Alexandria (De principiis).Footnote 50 Reflection on the Holy Spirit in these works was prompted by such diverse movements as Montanism, Marcionism, Gnosticism, Monarchianism and Neo-Platonism. As a result, their pneumatology is not cut from the same cloth. Earlier writings, such as the Second Epistle of Clement (ca. 120–40 ce) and The Shepherd of Hermas (mid-second century ce), are even less fixed and consistent in their understanding of the Spirit. Neither distinguishes clearly between the Son and the Holy Spirit, and both sometimes elide the Holy Spirit and the human spirit.Footnote 51 For example, consider the following well-known passage from The Shepherd:

God made the Holy Spirit dwell in the flesh that he [Or: it] desired, even though it preexisted and created all things. This flesh, then, in which the Holy Spirit dwelled, served well as the Spirit's slave, for it conducted itself in reverence and purity, not defiling the Spirit at all. Since it lived in a good and pure way, cooperating with the Spirit and working with it in everything that it did, behaving in a strong and manly way, God chose it to be a partner with the Holy Spirit. For the conduct of this flesh was pleasing, because it was not defiled on earth while bearing the Holy Spirit. Thus he took his Son and the glorious angels as counselors, so that this flesh, which served blamelessly as the Spirit's slave, might have a place of residence and not appear to have lost the reward for serving as a slave. For all flesh in which the Holy Spirit has dwelled – and which has been found undefiled and spotless – will receive a reward (Shep 5.6.5–7).Footnote 52

In his book The Holy Spirit in the Ancient Church, Henry Swete comments on this passage: ‘What are we to make of the place [the author] here assigns to the Holy Spirit? Is he thinking of the Spirit of the Conception and the Baptism? Or is the Spirit in this passage to be identified with the Son – the pre-existent Divine nature of Christ?’Footnote 53

This ambiguity around the nature and role of the Spirit is hardly confined to The Shepherd. Consider a couple of other passages from Second Clement:

Since Jesus Christ – the Lord who saved us – was first a spirit and then became flesh, and in this way called us, so also we will receive the reward in this flesh (2 Clem 9.5)Footnote 54

And even though the church was spiritual, it became manifest in Christ's flesh, showing us that any of us who protects the church in the flesh, without corrupting it, will receive it in the Holy Spirit. For this flesh is the mirror image of the Spirit. No one, therefore, who corrupts the mirror image will receive the reality that it represents. And so, brothers, he says this: ‘Protect the flesh that you may receive the Spirit.’ But if we say that the flesh is the church and the Spirit is Christ, then the one who abuses the flesh abuses the church. Such a person, therefore, will not receive the Spirit, which is Christ (2 Clem 14.2–4).Footnote 55

The apparent lack of pneumatological precision in passages such as these illustrates a wider indeterminacy in early Christian writings regarding the status and function of the Holy Spirit, which persisted well into the fourth century.Footnote 56 It is this environment of theological ambiguity that I suggest may also be reflected in P46's scribal irregularities surrounding πνεῦμα.Footnote 57 Yet, caution is in order. Correlation does not entail causation, and we will do well to remember that many factors were probably at play in the emerging patterns of nomina sacra in early Christian texts.Footnote 58 Moreover, it is important to note that scribal practices for rendering πνεῦμα in later manuscripts did not necessarily gravitate towards simple standardisation. For example, in Codex Sinaiticus, πνεῦμα is almost always rendered as a nomen sacrum; in Codex Bezae it is abbreviated less consistently; while in Codex Vaticanus it is hardly abbreviated at all.Footnote 59 There is no tidy correlation between these differing scribal treatments of πνεῦμα and concomitant developments in the realm of theology.

At the same time, scribal practices should not be interpreted in isolation from their wider socio-cultural contexts. As Haines-Eitzen puts it, ‘The debates over issues of doctrine and praxis that occupied the early Christian church indeed all found their way into the textual arena.’Footnote 60 Bart Ehrman similarly remarks: ‘The New Testament manuscripts were not produced impersonally by machines capable of flawless reproduction. They were copied by hand, by living, breathing human beings who were deeply rooted in the conditions and controversies of their day.’Footnote 61 P46 is no exception.

While it is impossible to know the exact extent to which theological ambiguities around the Spirit may have played a role in the scribe's decisions to write πνεῦμα as a nomen sacrum or in full, it is easy to imagine how the ideological commitments and socio-cultural location of a scribe would inevitably surface through the tip of his pen. Yet, as we have seen, treating the nomina sacra as reliable indicators of theological meaning is fraught with hazards.Footnote 62 The pattern simply is not stable enough to bear interpretive weight. Still, the variability that precludes such interpretive certainty itself testifies to the general fluidity of both scribal practices and pneumatological reflection during the period in which P46 was produced. The idiosyncrasy of πνεῦμα language in P46 reflects its sociological situation within a flurry of emerging scribal and theological developments. It also suggests some relationship between the two, even while reminding us that scribal patterns do not map directly onto their theological and socio-cultural landscapes.

Exactly how these realities overlay in P46 is a matter for further investigation. Could the scribe's decision not to record πνεῦμα as a nomen sacrum in the Trinitarian benediction of 2 Cor 13.13 indicate some hesitance to ascribe equal status to Father, Son and Spirit, similar to the subordinationism evident in Tertullian and Origen? Does the usage of nomina sacra to refer to spiritual persons in 1 Cor 2 suggest some affinity with the notion of theosis? Or might the nomina sacra for πνεῦμα in P46 serve a more symbolic than theological function – simply to express visually the identity of Christians as a discrete social group?Footnote 63 It is difficult to say for certain. What we do know is that the very phenomenon that so stubbornly resists explanation reveals scribes at work in the fascinating process of cultural conveyance, reading and writing not simply by the letter, but also for the spirit of the text.