Take-Home Points

-

∙ Impulsive violence is the most frequent form of violence seen in institutional settings, followed by predatory violence and psychotic violence.

-

∙ Impulsive violence is a dimension of psychopathology that cuts transdiagnostically across numerous psychiatric disorders, including psychotic illnesses, impulsive illnesses and psychopathy.

-

∙ Impulsivity may be a dimension of psychopathology representing dysfunctional reward processing, ultimately resulting in compulsive behaviors ranging from drug addiction to gambling, binge eating, and impulsive violence.

Introduction

Violence can be deconstructed into psychotic, predatory, and impulsive subtypes,Reference Nolan, Czobor and Roy 1 , Reference Quanbeck, McDermott, Lam, Eisenstark, Sokolov and Scott 2 and theoretically each subtype can be mapped onto its own unique malfunctioning brain circuits.Reference Stahl 3 In institutional settings, impulsive violence is the most frequent form of violence with the greatest unmet need for effective, evidence-based treatment.Reference Stahl 3 – Reference Rosell and Siever 9 Although not a formal diagnostic feature of any psychiatric illness, impulsive violence is nevertheless a behavioral dimension that can cut transdiagnostically across many conditions, ranging from personality disorders (especially psychopathy and borderline personality disorder) to mood disorders and psychotic disorders.Reference Coccaro, Fanning, Phan and Lee 8 – Reference Stahl and Grady 13 A novel formulation of impulsive violence presented here is to conceptualize it as a behavior that lies within the impulsivity–compulsivity spectrum. Impulsive-compulsive disorders include not only drug addiction, but also behavioral addictions such as gambling, binge eating, and possibly impulsive violence.Reference Grant and Kim 10 – Reference Stahl and Grady 13 These disorders could theoretically all share a common pathophysiology, namely an imbalance between the circuits that motivate behavior due to reward/conditioning on the one hand and circuits that control/inhibit impulsive drives on the other.Reference Coccaro, Fanning, Phan and Lee 8 – Reference Volkow, Wang and Baler 17 The hope is that this new formulation of impulsive violence may lead to renewed efforts to find effective treatments based on behavioral and pharmacological interventions that target the hypothetical maladaptations in these brain circuits.

Impulsive and Compulsive Behaviors Are Influenced by Multiple Areas of the Brain

Changes within 4 main brain circuits that control key aspects of impulsive and compulsive behavior may hypothetically underlie the pathophysiology of addiction-like behavior, from substance abuse to behavioral addictions such as gambling, binge eating, and impulsive violence.Reference Grant and Kim 10 – Reference Volkow, Wang and Baler 17 These neuronal networks regulate the following:

-

– Reward/saliency

-

– Motivation/drive

-

– Learning/conditioning

-

– Inhibitory control/emotional regulation/executive function

In vulnerable individuals, exposure to provocative emotional inputs (or drugs of addiction, gambling, or food) theoretically leads to a weakening of control circuits due to conditioned learning. This resets reward thresholds for reacting to the stimulus, due in part to undermining the cortical top-down networks that regulate impulses. The result is impulsivity and compulsivity.Reference Coccaro, Fanning, Phan and Lee 8 – Reference Volkow, Wang and Baler 17 This model has been linked extensively to the pathophysiology of drug addiction.Reference Grant and Kim 10 – Reference Volkow, Wang and Baler 17 Applying this model to impulsive violence suggests that individuals become conditioned to having violent reactions to various provocative stimuli, so that over time, such stimuli create impulses to react violently that eventually become automatic, mindless behaviors and a compulsive habit. This hypothesis for the evolution of impulsive violence into a habit or “addiction” is analogous to how drugs of abuse theoretically lead from a rewarding “high” to the compulsive and self destructive drug-seeking behaviors of addiction.Reference Grant and Kim 10 – Reference Volkow, Wang and Baler 17

The Inability to Resist Urges: A Theory of Impulsive Violence

In a normal state, when a salient stimulus is presented, the reward of that stimulus is evaluated. If the stimulus is perceived to have a favorable outcome, behavior is elicited to achieve that reward. If, however, the stimulus is perceived to have an unfavorable outcome, behavior is inhibited. This type of behavior is called goal-directed behavior or action-outcome learning, such that when that same stimulus is presented again, the value of the reward will be remembered to either elicit the behavior or inhibit the behavior.Reference Everitt and Robbins 14 , Reference Wyvell and Berridge 16 If this behavior is repeated, over time the reward of the stimulus will be devalued, such that the stimulus itself is enough to drive behavior, regardless of the outcome.Reference Everitt and Robbins 14 , Reference Wyvell and Berridge 16 This type of behavior is called stimulus-directed behavior or stimulus-response learning (Pavlovian conditioning). It is through stimulus-response learning that habits are formed.Reference Everitt and Robbins 14 – Reference Wyvell and Berridge 16

How does this formulation of the reward system relate to impulsive violence? Taking a rational, willful decision to commit a violent act in the absence of delusions and hallucinations is sometimes called criminogenic thinking or criminalness. More specifically, criminalness can be defined as behavior that breaks laws and social conventions and/or violates the rights and well-being of others.Reference Bartholomew and Morgan 18 When criminalness is impulsive, hot-blooded, characterized by high levels of autonomic arousal, precipitated by provocation, associated with negative emotions such as anger or fear, and usually representing a response to a perceived stress (reactive, affective, and hostile), it can be considered impulsive violence and can be conceptualized as an impulsive-compulsive disorder.Reference Coccaro, Fanning, Phan and Lee 8 – Reference Stahl and Grady 13 , Reference Bartholomew and Morgan 18 , Reference Felthous 19 Analogous to other impulsive compulsive disorders,Reference Coccaro, Fanning, Phan and Lee 8 – Reference Stahl and Grady 13 impulsive violence can be hypothetically linked to devaluation of a salient provocative stimulus that causes an affective response, and that over time with many repetitions switches goal-directed behavior (such as removing a threat, stopping a provocation, getting one’s way in a conflict situation) into stimulus-directed behavior, where a provocation immediately leads to impulsive violence without thought and as a habit. However, if criminalness is calculated, planned, premeditated, proactive, predatory, instrumental, and cold-blooded, it is psychopathic and neither impulsive nor regulated by the neural networks being discussed here.Reference Coccaro, Fanning, Phan and Lee 8 – Reference Stahl and Grady 13 , Reference Bartholomew and Morgan 18 , Reference Felthous 19 Rather, predatory violence may preferentially involve the amygdala and its connections with prefrontal cortex.Reference Coccaro, Fanning, Phan and Lee 8 , Reference Rosell and Siever 9 Patients with psychopathy can have both types of criminalness.Reference Bartholomew and Morgan 18 , Reference Felthous 19

Maladaptations in the Reward Circuitry that Could Potentially Underlie Impulsive Violence

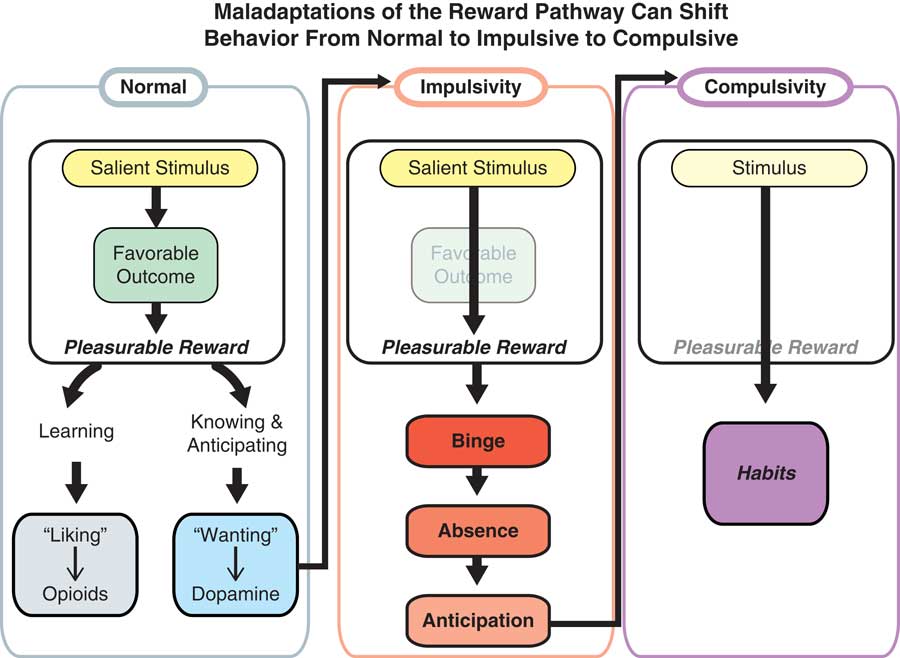

Under normal conditions, if a salient stimulus causes a favorable outcome, this behavior will be encoded as a pleasurable reward (Figure 1). The reward of drug-induced euphoria is self-evident, but what is the reward of committing violence? In the context of Figure 1, that reward could be considered to be the removal of a threat, the termination of a provocation, or having one’s demands that led to a provocative input from others nevertheless be fulfilled. Learning that the results of any given reward are pleasurable is called “liking,” and is an opioid-dependent process (Figure 1, left).Reference Wyvell and Berridge 16 Knowledge and anticipation of these pleasurable rewards are called “wanting,” and are dopamine-dependent processes (Figure 1, left).Reference Wyvell and Berridge 16

Figure 1 Maladaptations of the reward pathway can shift behavior from normal to impulsive to compulsive. Under normal conditions, if a salient stimulus causes a favorable outcome, this behavior will be encoded as a pleasurable reward. The learning of this pleasurable reward is called “liking,” and is an opioid-dependent process. The knowledge and anticipation of this pleasurable reward is called “wanting,” and is a dopamine-dependent process. An increase in “wanting” is said to underlie impulsivity, such that the drive for the pleasurable reward outweighs the outcome and the behavior is repeated without forethought. In some individuals, there is a higher probability that “wanting” behavior will develop into impulsive behavior due to an underlying environmental or genetic risk. This increased risk is deemed an “impulsivity trait” and can lead to the development of impulsive disorders such as binge eating, drug addiction, and, perhaps, impulsive violence. Repetition of the impulsive behavior, or binging, does not happen all the time; the absence of behavior, however, can lead to a stronger desire, or anticipation, for the reward. It is this cycle of binge–abstinence–anticipation that can lead to compulsivity. When a behavior becomes compulsive, the reward no longer matters and the behavior is strictly driven by stimulus. It is through this mechanism that habits develop.

An increase in “wanting” is said to underlie impulsivity, such that the drive for the pleasurable reward outweighs the outcome and the behavior is repeated without forethought or weighing the favorableness of the outcome (progression of the process from Figure 1, left, to Figure 1, middle).Reference Everitt and Robbins 14 – Reference Wyvell and Berridge 16 In some individuals, there is a higher probability that “wanting” behavior will develop into impulsive behavior due to an underlying environmental or genetic risk.

This increased risk is deemed an “impulsivity trait,” and can lead to the development of impulsive disorders such as drug addiction, binge eating, gambling, or, as hypothesized here, impulsive violence when impulsivity leads to habit, or compulsivity (progression of Figure 1, middle, to Figure 1, right).Reference Coccaro, Fanning, Phan and Lee 8 – Reference Volkow, Wang and Baler 17 Repetition of the impulsive behavior, called binging, does not happen all the time; the absence of behavior, however, can lead to a stronger desire, or anticipation, for the reward. It is this cycle of binge–abstinence–anticipation that can lead to compulsivity.Reference Everitt and Robbins 14 – Reference Wyvell and Berridge 16 When a behavior becomes compulsive, the reward no longer matters, and the behavior is strictly driven by stimulus. It is through this mechanism that habits develop, just as in the classical conditioning of Pavlovian dogs. In the case of impulsive violence, hypothetically the stimulus is an environmental provocation, and the compulsive habit is retaliatory impulsive violence.

How Do Reward Pathways Regulate the Maladaptive Shift of Normal to Impulsive to Compulsive?

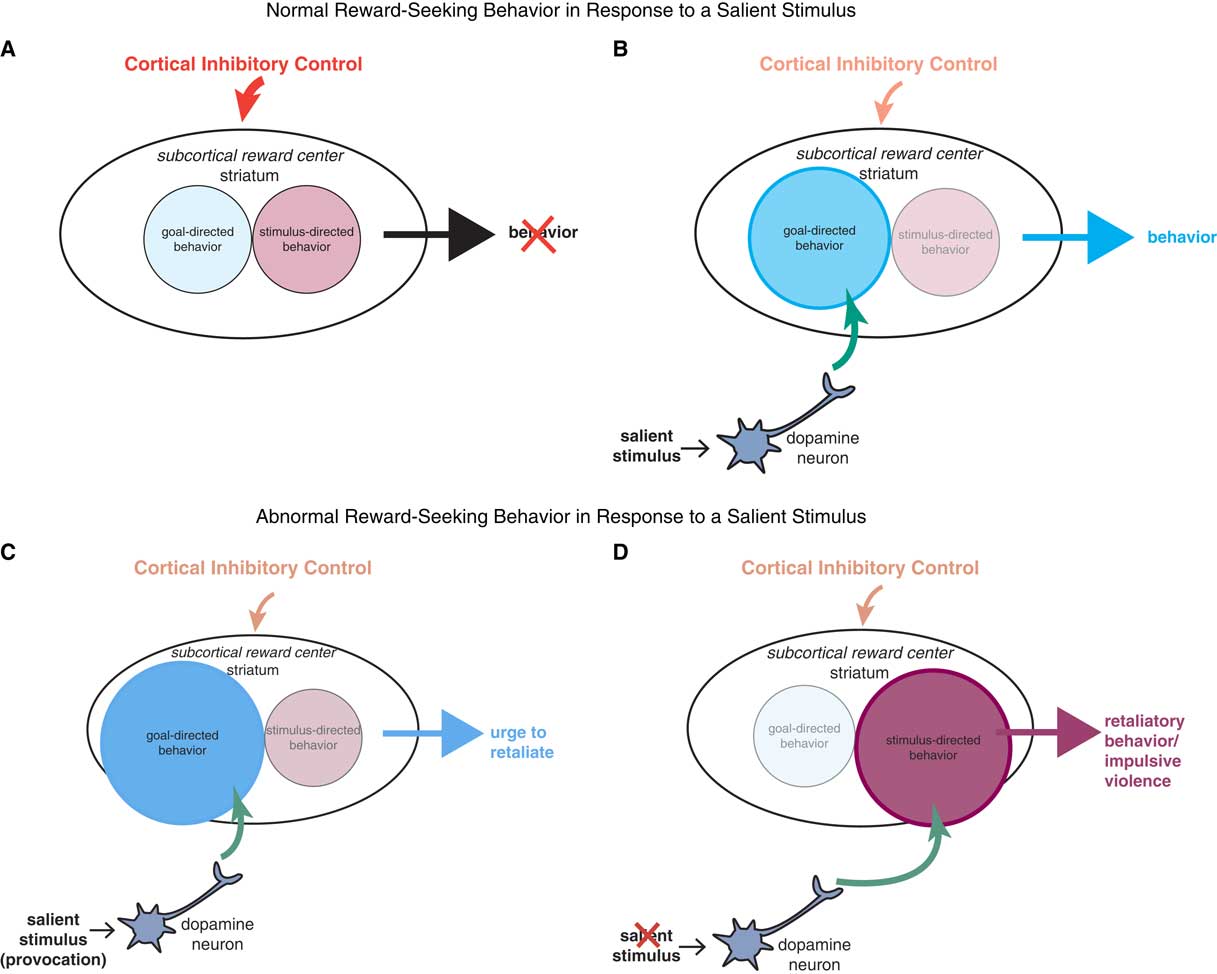

In a basal, unstimulated state, in a normal individual the subcortical reward center is inhibited by inputs from the prefrontal cortex leading to an inhibition of behavior (Figure 2A).Reference Everitt and Robbins 14 – Reference Wyvell and Berridge 16 When a salient stimulus is presented, via activation of dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain, the ventral striatum becomes activated, which overrides the inhibition from the cortex and elicits goal-directed behavior (Figure 2B).

Figure 2 Reward-seeking behavior in response to salient stimuli. (A) In a basal, unstimulated state, the subcortical reward center is normally inhibited by inputs from the prefrontal cortex leading to an inhibition of behavior. (B) When a salient stimulus is presented, via activation of dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain, the striatum becomes activated, which overrides the inhibition from the cortex and elicits goal-directed behavior. (C) However, in individuals prone to impulsive behaviors, the subcortical reward center, in an unstimulated state, hypothetically receives less inhibitory input from the cortex, leaving these individuals more sensitive, or primed, to engage in reward-seeking behavior. In response to a salient stimulus, these individuals have a greater influx of dopamine to the striatum, which elicits a greater drive for goal-directed behavior. (D) If this goal-directed behavior is repeated enough times, the locus of control shifts, such that dopaminergic inputs to the reward center target the area of the striatum important for stimulus-directed behavior. Since the behavior is now being controlled by habit (ie, stimulus-directed) instead of reward (ie, goal-directed), the stimulus loses its salience and drives the behavior automatically and impulsive violence results over and again from the provocative stimulus.

However, in individuals who are prone to impulsive behaviors, the subcortical reward center, in a unstimulated state, hypothetically receives less inhibitory input from the cortex, leaving these individuals more sensitive, or primed, to engage in reward-seeking behavior (Figure 2C).Reference Coccaro, Fanning, Phan and Lee 8 – Reference Wyvell and Berridge 16 In response to a salient stimulus, these individuals have a greater influx of dopamine first to the ventral striatum, which elicits a greater drive for goal-directed behavior (Figure 2C). If this behavior is repeated enough times, the locus of control shifts, such that dopaminergic inputs to the reward center target the area of the dorsal striatum that is important for stimulus-directed behavior (Figure 2D).Reference Everitt and Robbins 15 Since the behavior is now being controlled by habit (ie, stimulus-directed) instead of reward (ie, goal-directed), the stimulus loses its salience and drives the behavior automatically; impulsive violence results over and again from the provocative stimulus.Reference Coccaro, Fanning, Phan and Lee 8 – Reference Volkow, Wang and Baler 17

Can Impulsive Violence Potentially Be Modified by Treatment?

Is there any treatment that can control impulsive violence in institutional settings across the wide range of psychiatric disorders in which it is observed? The literature suggests that treating the underlying psychiatric disorder is the first order of business, and in some cases, control of mood and psychosis may mitigate impulsive violence.Reference Stahl 3 – Reference Rosell and Siever 9 Psychotherapeutic interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (DBT) or dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) for individuals or groups may also be effective (5). However, in practice, such interventions have not reduced impulsive violence adequately in institutional settings.

Should control of impulsive violence be possible by “unlearning” or normalization of maladaptive behavior? Although theoretically possible with the interventions mentioned above, or empirically observed in those, for example, who are addicted to drugs following a long period of enforced abstinence, the success rate is disappointingly low and the recidivism rate disappointingly high. Perhaps it is time to direct psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacologic interventions to restoring the balance between top-down control and bottom-up drives, so that impulses that are triggered by conditioned stimuli no longer trigger habitual behavior in patients with impulsive violence. Thus, novel psychotherapeutic interventions, such as cognitive remediation, could theoretically help to restore top-down inhibitory controls.Reference Medalia, Opler and Saperstein 20 , Reference Hooker, Bruce, Fisher, Verosky, Miyakawa and Vinogradov 21 Pro-cognitive psychopharmacologic agents may also help in this regard.Reference Stahl 22 Aggressive antipsychotic treatment can also reduce bottom-up emotional drive,Reference Stahl 3 – Reference Stahl, Morrissette and Cummings 5 but is not commonly implemented in many institutional settings.Reference Stahl 3 – Reference Stahl, Morrissette and Cummings 5 An optimistic note has recently been sounded by the approval of lisdexamfetamine for one of the impulsive-compulsive disorders, binge eating disorder, in which theoretical modulation of dopaminergic neurons that feed into the reward center reset the balance of too much bottom-up drive and insufficient top-down inhibition.Reference McElroy, Hudson and Mitchell 23 This is consistent with shifting control away from stimulus-directed behavior, regulated by the dorsal striatum, and back toward goal-directed behavior, regulated by the ventral striatum, while also restoring adequate cortical inhibitory control. Lessons learned from emerging new targets for treatment of drug addiction may also provide leads for how to treat impulsive violence as a behavioral addiction.