Introduction

Historians have investigated emotions of the past for over 30 years (e.g. Stearns & Stearns Reference Stearns and Stearns1985; Rosenwein Reference Rosenwein2006; Rosenwein & Cristiani Reference Rosenwein and Cristiani2018), but the discipline of archaeology has been slow to make any meaningful contribution. Yet, by studying the physical remains of the past, I contend that archaeologists can further our understanding of the personal and emotional experiences that were shaped and mediated through the practices of the material world, and vice versa. The aim of this article is to introduce a concept for investigating emotions in the past through archaeological material culture. Although ‘emotion’ has become a dominant word in our modern vocabulary, it was not used during the later English Middle Ages (Leys Reference Leys2011; Frevert et al. Reference Frevert, Scheer, Schmidt, Eitler, Hitzer, Verheyen, Gammerl, Bailey and Pernau2014; Oxford English Dictionary 2018); ‘affect’ and ‘feeling’ were used synonymously, and ‘passion’ was used to describe an intense emotion or feeling. Here, I use all these words interchangeably.

Emotion is a vast subject, of interest to a range of disciplines (see Tarlow Reference Tarlow2000: 713–18; Reference Tarlow2012: 170–72; Wierzbicka Reference Wierzbicka2010; Rosenwein Reference Rosenwein2016: 1–10; Rosenwein & Cristiani Reference Rosenwein and Cristiani2018: 9–25). Debate has often focused on what an emotion is, the evolutionary origin of such feelings, and questions of universality or constructionism. While I do not repeat such debates here, I take a social constructivist standpoint in agreeing with the premise that, although emotional experiences are socially constructed, feelings are experienced and sensed within the mind and by the body. Emotions are affected by social expectations and norms, and they can be learned. They can be an action, and can therefore become a form of practice or performance. Here, I use material evidence to explore the later medieval social expectations of emotions and emotional practices or performances.

Materiality has become a standard axiom in archaeology (e.g. DeMarrais Reference DeMarrais2004; Meskell Reference Meskell2005; Overholtzer & Robin Reference Overholtzer and Robin2015). In his volume Materiality: an introduction, Miller (Reference Miller2005) shows that the immaterial is not easily separated from the material, and while materiality may be shown to be active and reflexive (DeMarrais Reference DeMarrais2004: 12), it is certainly not without emotion. Material things are dynamic and vibrant, and interaction with them through practices and shared qualities can generate material relationships (Alberti et al. Reference Alberti, Jones and Pollard2013). Fowler and Harris (Reference Fowler and Harris2015) argue that material things can enter relationships and emerge from them: they are both being and becoming, and we can study them at specific moments. Similarly, Johnson (Reference Johnson, Overholtzer and Robin2015: 30) uses the term materiality “to insist that the human world does not have an existence that is somehow prior to or independent of the material world”. He argues that humans and the material world are inseparable, and one does not and cannot create or modify the other in a linear or isolated manner. Material practices and interactions include immaterial emotions. Therefore, I posit, alongside Johnson's “ideas, beliefs, and cultural attitudes”, that emotions are “continually shaped and mediated through the practices of the material world” (Johnson Reference Johnson, Overholtzer and Robin2015: 31), and that the material world is continually shaped and mediated through emotions.

Here, I consider the study of emotion in archaeology, and how historical approaches have influenced such investigation. Taking cues from historians, I propose a method for investigating past emotions through material things, by identifying ‘emotants’, a term conceived here to describe a physical agent that is characterised by or serves in the capacity of emotion. This approach is tested with two case studies that reveal material-emotional practices and relations.

The archaeology of emotion

With her article ‘Emotion in archaeology’, Tarlow (Reference Tarlow2000: 729) sparked an interest in the materiality of emotional practices by asking, “What are the relationships between spaces, architectures, artefacts, and emotions? How do things become emotionally meaningful?” Gosden followed with an anthropological study on the return of Pūkākī (a carved representation of a Ngāti Whakaue ancestor) to his ancestral home of the Te Arawa people of New Zealand. Gosden concluded that “Emotions are materially constituted and material culture is emotionally constituted” (Gosden Reference Gosden, DeMarrais, Gosden and Renfrew2004: 39), and that there is an affective relationship between humans and material. Harris and Sørensen (Reference Harris and Sørensen2010) attempted to investigate such a relationship in their interpretations of the Mount Pleasant Neolithic henge in Dorset, proposing a vocabulary to incorporate emotions into archaeological interpretations and stimulate discussions on the subject.

Tarlow's (Reference Tarlow2012) subsequent review article, ‘The archaeology of emotion and affect’, demonstrated that archaeological studies were beginning to consider the emotions of the past, but that more work was (and still is) needed on the variability of emotion in the past. In addition to this review, three points are worth considering. First, the topic remains relatively understudied in archaeology, with the edited volume The archaeology of anxiety (Fleisher & Norman Reference Fleisher and Norman2016) being an exception. There, the editors make an “experimental and exploratory effort into thinking about the place of concern, worry and fear in archaeological interpretations” (Fleisher & Norman Reference Fleisher and Norman2016: 1). In this publication, topics post-1200 BC and pre-seventeenth century AD are limited to one article on the Late Pre-Hispanic Fortress of Acaray, Perú (Brown Vega Reference Brown Vega, Fleisher and Norman2016); moreover, some articles fail to move satisfactorily beyond the pairing of a site or assemblage with a general feeling of fear or anxiety. Second, no studies of emotion in archaeology have targeted the later medieval period (c. AD 1066–1600). Finally, Tarlow's (Reference Tarlow2012: 181) demand for more than “the basic identification of fear or joy in the past” may have proved too challenging for archaeologists, or perhaps there is a pervasive unwillingness to try. Is the study of emotion deemed too frivolous and subjective? And is ‘emotion and archaeology’ to be approached in the same manner as ‘aesthetics and archaeology’ once was (see Skeates Reference Skeates2017)? Clearly, proposals for new methodologies and the further study of emotion and archaeology have the potential to make greater sense of the past.

It must be emphasised that researchers do not ignore material culture in emotion studies (e.g. Richardson Reference Richardson, Hamling and Richardson2010; Moran & O'Brien Reference Moran and O'Brien2014; Dolan & Holloway Reference Dolan and Holloway2016; Ilmakunnas Reference Ilmakunnas2016; Toivo Reference Toivo2016), but archaeologists, regrettably, are not at the forefront. It is historians of emotion who have engaged with objects within a discipline that has generally embraced ‘material culture history’ only in the last decade or so (Gerritsen & Riello Reference Gerritsen, Riello, Gerristen and Riello2015: 3).

As leading historians in the field of the history of emotions, Rosenwein and Reddy have advanced the methodology and understanding of feelings by using documentary sources. Rosenwein is best known for identifying and exploring feelings in what she has defined as ‘emotional communities’ in pre- and early modern Western Europe (e.g. Reference Rosenwein2006, Reference Rosenwein2010, Reference Rosenwein2016). Her position is that of a historian amassing textual evidence and interrogating sources from and about an identified ‘emotional community’ (similar to social communities of people) to

establish what these communities […] define and assess as valuable or harmful to them […] the emotions that they value, devalue, or ignore; the nature of the affective bonds between people that they recognise; and the modes of emotional expression that they expect, encourage, tolerate, and deplore (Rosenwein Reference Rosenwein2010: 11).

Reddy, an anthropologist and historian, has been equally influential. He coined the term ‘emotives’, and identified emotional refuges created in the face of emotional regimes and control in his studies of medieval and post-medieval Europe (Reddy Reference Reddy2001, Reference Reddy2012). He asserted, for example, that the development of courtly love in Europe was a result of attitudes towards, and opposition to, sexual desire by the Christian Church in the high Middle Ages (Reddy Reference Reddy2012), and that the French Revolution was an emotional revolution (Reddy Reference Reddy2001). The focus on emotional communities seems to have influenced Tarlow's (Reference Tarlow2012: 181) conclusion that there is a need to recognise the environment of fear, for example, that was manipulated to promote group cohesion or social practices, rather than simply identifying the emotion itself. But it is the basic step of identifying emotion and visceral aspects of life that is often missing from archaeological studies.

The emotional communities approach, as with many historical methods, leads to conclusions being drawn on a general level, to the detriment of the individual. Here, I argue that, because of the nature of the medieval archaeological evidence, we should aim to explore both the personal emotional experiences, however idiosyncratic (contra Tarlow Reference Tarlow2012: 169), and the broader social patterns. All people will have responded to an object or event in their own way, and viewing these as generalisations can lead to bland conclusions that obscure the individual and their emotional response(s). We should therefore look for the layers of individuals, things and the immaterial that contribute to these conclusions, and not dismiss the finer human and object stories that they contain.

To that end, I present two case studies introducing a new approach and terminology. The first is a preliminary investigation into inscribed finger rings and brooches from England in the thirteenth to early sixteenth centuries AD. The second concerns a more challenging object, part of a fifteenth-century plough from Northumberland. It can be identified as an ‘emotant’ that was part of both an individual and communal emotional practice, with parallels identified elsewhere in later medieval Europe. The two case studies focus on the more positive emotions of hope and love, rather than on the fear or anxiety that have thus far dominated related archaeological research.

Emotants

To address the study of emotions, I propose the neologism ‘emotant’, defined as a physical agent that is characterised by or serves in the capacity of emotion. The agent can be affected by human emotion and/or can influence the emotion felt by a person. Emotants, therefore, can be any feature, material culture or thing that we study in archaeology, from objects to entire landscapes. They can all be used in ways prompted by human feeling. Using Gosden's (Reference Gosden, DeMarrais, Gosden and Renfrew2004: 39) phrase, they can be identified as being “emotionally constituted”, and part of emotional practices. Contextualisation and investigation into the objects’ materials and relationships is required to understand how they acted as emotants in the past, how they were characterised by emotion and used in practice.

The neologism is influenced by the term ‘emotive’ used by Reddy (Reference Reddy2001). In its most basic form, Reddy defines emotives as verbal or written expressions that could change, create, hide or intensify emotions. They have the power to act, simultaneously changing the person uttering the expressions and those to whom they are addressed. Although not defined as emotives, Rosenwein (Reference Rosenwein2016) also identifies emotional words used by past communities, which allows her to quantify and deduce the form and expressions of emotions that communities expected, tolerated and valued. In archaeology, emotants similarly can aid our understanding of emotions.

We may also be able to recognise webs of feelings and emotants. These webs differ from the sequences of feeling that Rosenwein (Reference Rosenwein2016: 8) proposes, as there is no simple, linear progression from an emotion felt to expressing it through an object and to a new emotion. Nor can the webs be easily compared with Harris and Sørensen's (Reference Harris and Sørensen2010) ‘affective fields’, “the networks of people and things through which emotions are generated” (Harris & Sørensen Reference Harris and Sørensen2010: 153), as it is not only these networks that generate emotion. Instead, feelings and emotants are part of, and are connected in, webs, and, as with a spider's web, the connections may break, be renewed or catch and incorporate new elements (e.g. emotants/feelings/people/landscapes). The webs may also grow, be recreated, decline or resonate over short or long periods, and thus similarities or differences in materials, emotional practices and relations over time can be explored.

Case study 1: dress accessories of ‘love’

As routinely examined in historical studies, words can be used to discover emotions of the past. In archaeology, few material forms have words added to them, but later medieval dress accessories are a relatively common type of inscribed object. These include finger rings, brooches and pendants made of gold, silver, silver-gilt or copper alloy. Almost 90 years ago, Evans (Reference Evans1931: xi) anticipated current interest in feelings, writing “of all these inscriptions [on finger rings] none brings us more closely into contact with the thoughts and feelings of their former wearers than the amatory inscriptions”. Many such finger rings were probably given as courtship gifts (Standley Reference Standley2013: 32–36), and they can provide evidence of the ‘ideal’ emotional feelings and practices from a time when chivalry and courtly romances were flourishing.

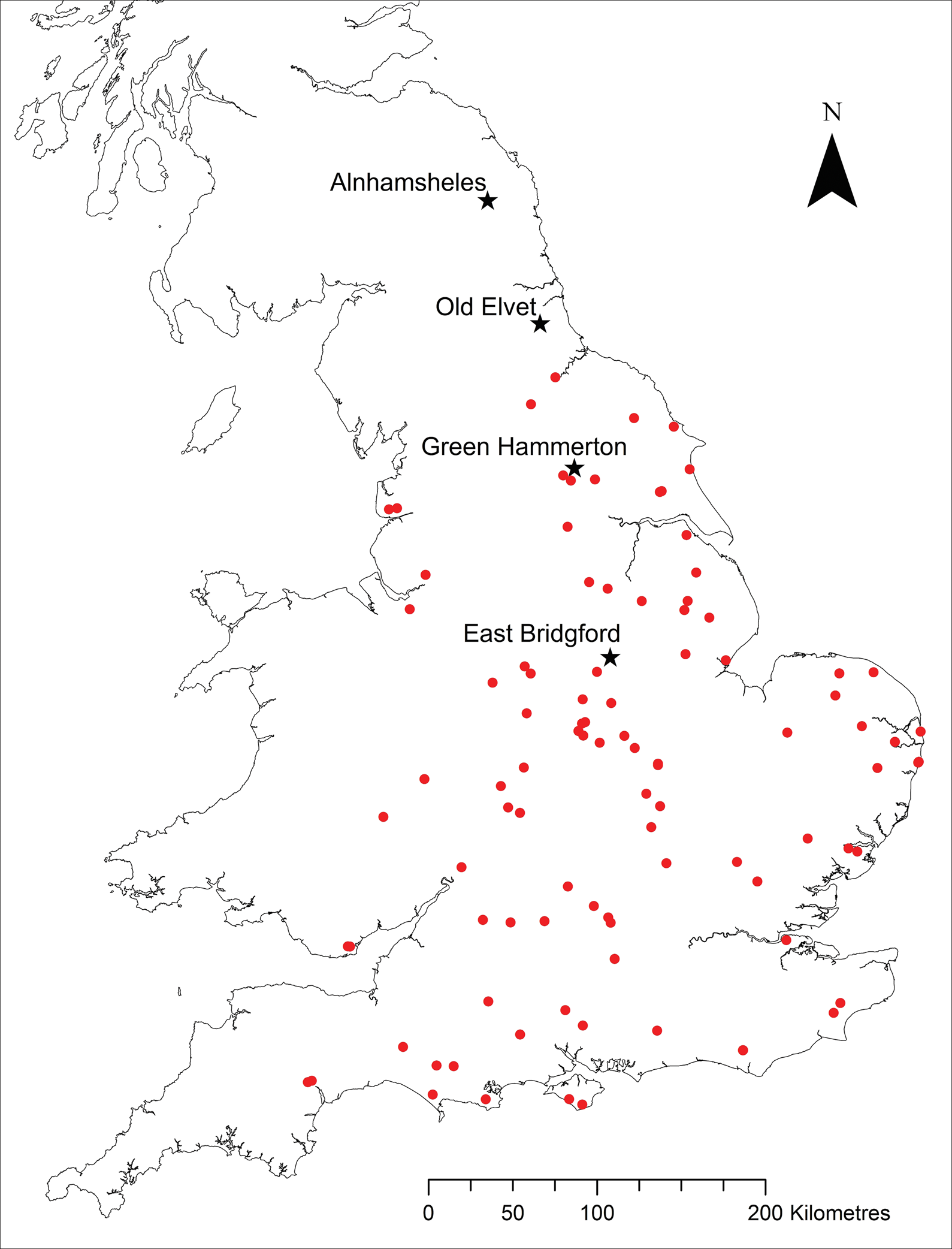

Analysis of 251 inscribed finger rings and brooches recorded by Evans (Reference Evans1931: 1–15) and 530 ‘medieval’ examples (including two pendants) from England and Wales catalogued by the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS; data downloaded on 16 August 2018; Portable Antiquities Scheme n.d.), shows that 160 (20 per cent) were inscribed with phrases that include an ‘affective’ word (expressing emotion or feeling) (Figure 1 & Table 1). The remainder are inscribed with invocations to Jesus, the Virgin Mary and the Magi, or the inscriptions are illegible. The finger rings are the most commonly inscribed objects, with love being the most frequently expressed emotion. Other emotions are also embedded in the jewellery, including joy, hope and desire. Collectively, there is a range of affective words used to communicate feelings, giving the impression that these feelings were socially encouraged and expected in courtships or established relationships.

Figure 1. Locations mentioned in the text (★) and findspots of medieval finger rings, brooches and pendants inscribed with an affective attribute recorded by the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) (•) (not all PAS records contain location details).

Table 1. Affective words inscribed on medieval dress accessories, recorded by the Portable Antiquities Scheme (n = 75) and Evans (Reference Evans1931) (n = 85).

The results change significantly when we include the word ‘heart’ (or the symbol ♥) as an affective attribute (Figures 2–3). While ‘heart’ was not a feeling in itself, it was understood as the seat of emotions, where a person's innermost thoughts and feelings were held (Oxford English Dictionary 2018). When occurrences of ‘heart’ are added to the data, the total number of objects inscribed with an affective attribute increases to 229 (29 per cent), ‘heart’ being the most commonly encountered on rings. But there are only six occurrences of ‘heart’ used in conjunction with another affective word; these are love, joy and desire. This suggests that the heart was an all-encompassing entity for all the emotions borne by the rings and brooches, and felt by the giver and presumably the wearer. The accessories indicate that by the late Middle Ages, the heart was considered the centre of the passions in popular culture. Its frequent use compared to other affective words reveals the heart's importance in changing, creating or intensifying feelings that the emotant objects contained, conveyed and potentially stimulated. The heart was not just symbolic; it formed an intrinsic part of the rings.

Figure 2. The frequency of affective words including ‘heart’/♥ on inscribed medieval dress accessories recorded by the Portable Antiquities Scheme and Evans (1931).

Figure 3. Ruby and emerald set gold finger ring, inscribed with ‘bon ♥ ne ment [or meut]’, ‘the good heart does not lie [or move]’ from Green Hammerton (North Yorkshire; PAS SWYOR-61ADFC, West Yorkshire Archaeology Advisory Service, licensed under CC BY 4.0).

The emotions communicated through the rings could, on occasion, have been quite literally acted on. The fifteenth-century ring from East Bridgford in Nottinghamshire provides an example (Figure 4). Inscribed with ‘amer et celer’ (to love and to conceal), this ring had been hidden within and worn as an inner lining to a larger ring decorated with the image of St Christopher carrying the Christ Child and inscribed with the word ‘loyalte’. If the first ring was perhaps given during a secret courtship, we can imagine its recipient following the instruction: to love, but to keep such passion hidden, and to do the same with the physical emotant. By concealing the ring within a devotional ring that bore feelings of loyalty to the saint, loyalty to a hidden, romantic relationship could be expressed. This example forms a web of emotions incorporating feelings of love and loyalty, two emotant rings, two romantic partners and the wearer's religious devotion and associated meditative feelings.

Figure 4. Gold finger ring inscribed with ‘amer et celer’ (to love and conceal), found inside another ring at East Bridgford (Nottinghamshire; PAS DENO-5082A6, Derby Museums Trust, licensed under CC BY 4.0).

While many rings were probably used in secular relationships, some could have had a primary role as Christian, devotional emotants. Similarly, rings inscribed with ‘remembering’ words have been identified as acting as memento mori, rather than simply instructions for remembering romantic partners (Standley Reference Standley2013: 98). Only 21 (4 per cent) of the PAS assemblage inscribed with an affective attribute were decorated with images or phrases that referenced Christ, God, the Trinity, the Virgin or a saint. Here, the most commonly used were ‘love’ (six), ‘heart’ (five) and ‘joy’ (four). Accessories identified by Evans (Reference Evans1931) have not been included in the count, as she did not record details of imagery, although in three examples, ‘love’ was associated with Christ. These particular emotants provide material evidence for the feelings that the faithful in late medieval Western Europe expected to experience in their affective meditations.

Case study 2: a tool of hope

This case study focuses on an object without an inscription: a plough coulter (the iron blade of a mould-board plough that cuts the soil vertically). Nevertheless, it is identified as an emotant that created, intensified and strengthened feelings of hope. The coulter was recovered during the excavation of the deserted medieval hamlet of Alnhamsheles in Northumberland (Dixon Reference Dixon2014: 205–206). It initially roused interest because it is one of only four post-Conquest coulters known in Britain, and was recovered from a site on the edge of moorland in the north-east of England rather than in the arable heartland in the Midlands (Dixon Reference Dixon2014: 205; Dyer Reference Dyer, Gerrard and Gutiérrez2018: 196). First documented in 1265, Alnhamsheles was a hamlet, which, by 1314/1315, had 11 tenants. It was abandoned by the mid sixteenth century. The settlement's name suggests that it began as a shieling—a temporary site used in transhumance when livestock were taken to uplands during summer months. Only two houses at the site have been excavated (Figure 5). The coulter was found in a drain sealed by paving stones in a dwelling that was extended in the late fifteenth century, and possibly included a byre or barn (Figures 6–7). Although part of the coulter's blade was missing, it was still a large piece of good quality iron that could have been recycled.

Figure 5. Plan of the village of Alnhamsheles. The coulter was found in a house on site 1, the southern building in the excavated area (drawn by Piers Dixon, reproduced with permission).

Figure 6. Plan of the southern house, Alnhamsheles site 1, phase 2 (c. 1350–1480). Hatching: line of robbed walls. The coulter was in the drain at the east end (findspot ★), paved over during reconstruction in c. 1480, when the building was extended eastwards (drawn by Piers Dixon, reproduced with permission).

Figure 7. The Alnhamsheles coulter in situ (photograph by Piers Dixon, reproduced with permission).

Ploughs were often shared amongst a community, or a wealthy villager may have owned a plough and lent or rented it out (Figure 8). At Alnhamsheles, the agricultural tool was incorporated in a building and the iron was not recycled or sold, presumably by choice. It is this unusual deposition, the function of the object, its material and the social context that suggest that the coulter was an emotant. Following destruction in a fire, the house was rebuilt in the 1480s, and the coulter deposited at this time. The fire has been attributed to an attack by the Scots, which was documented in an estate record of 1472 (Dixon Reference Dixon2014: 217). While the tenants must have invested in the rebuilding, they appear to have chosen not to gain financially from selling or recycling the defunct iron tool. An explanation for its context cannot be convincingly argued as accidental, nor as a convenient way to dispose of an unwanted item. I interpret the find as an intentional act, both place and object are of significance; the iron coulter was buried in the heart of the building as part of the inhabitants’ and the community's hope for prosperity and successful future harvests.

Figure 8. Detail from the Luttrell Psalter depicting a mould-board plough and ploughing team; the coulter cuts the soil ahead of the ploughshare (Add MS 42130 f.170r © British Library).

The practice of hoarding and depositing ironwork, including coulters, is recognised in European early medieval contexts, with the material itself also considered to have magical properties (Evans Reference Evans1966: 55–58; 140; Leahy Reference Leahy2013; Klápště Reference Klápště and Klápště2016: tab. 1; Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, McDonnell, Merkel and Marshall2016). Although examples of plough remains from secure later medieval contexts are rare, hoarded plough-irons have been found elsewhere in Europe (see Lerche Reference Lerche1994: 226–27, tabs XXXV & XXXVII). A find comparable to that from Alnhamsheles is a coulter wedged into a pointed, iron ploughshare excavated from the bottom of a deep boundary ditch outside the west end of the church of the Massereene Friary, County Antrim, Northern Ireland (Lynn Reference Lynnn.d.). Ploughshares were also used on mould-board ploughs, which, following the coulter, cut the earth horizontally (see Figure 8). The plough-irons from the Massereene Friary were found with a hoard of 11 coins (1501–1505 circulation) (Lynn Reference Lynnn.d.), indicating that they were deposited soon after the ditch was cut in the early sixteenth century, when the friary was founded. Depositing these items would not have been undertaken lightly, and the boundary location was also significant, as purposeful deposits at boundaries related to religious houses is a practice observed elsewhere, for example at Alnwick Abbey, Northumberland, Notley Abbey, Oxfordshire and the Carmelite Friary at Ludlow, Shropshire (see Standley Reference Standley2013: 82–83; Reference Standley2016: 131–32 & 134).

The importance of the medieval plough and its role in social life and agricultural production cannot be underestimated, and is evident in plough-related ceremonies undertaken by medieval communities. In Britain, between the ninth and twelfth centuries, for example, plough-irons were used in trials by ordeal to test for adultery and paternity, and the memory of such use continued into at least the seventeenth century (Morey Reference Morey1995). Ploughs even offered legal sanctuary in medieval England and France (Morey Reference Morey1998). Other communal ceremonies involving ploughs were carried out to ensure a good agricultural year, and to raise parish funds for associated feasts and shrine candles (Hutton Reference Hutton2001: 124–26; Duffy Reference Duffy2005: 13).

In Dives and pauper (1405–1410) (Parker Reference Parker1493: chapter XXXIIII), there is a reference to leading a plough around a fire at the beginning of the year to “fare the better all the yere folowynge”. Often kept in churches, shared or borrowed ploughs would be blessed and lights lit for them on Plough Sunday. An early fifteenth-century record shows that on the day after Epiphany (Plough Monday), parish funds were raised during the dragging of a plough through a community in Old Elvet in Durham (Fowler Reference Fowler1898: 224). It was perhaps for such events that the fifteenth-century badges in the form of crowned ploughs were sold and worn (or even purposefully deposited) in the hope that the vital crops would ‘fare better’ (Spencer Reference Spencer1990: 110–11); such badges would also be emotants. Practices involving plough-irons were still in use in the nineteenth century: a coulter placed in a fire, or a stone that had become stuck between a coulter and share being thrown over the house to ensure the successful churning of milk in Wexford (Ireland) and Aberdeenshire, respectively (Gregor Reference Gregor1884: 330).

A coulter also makes an appearance in Chaucer's Miller's tale (late fourteenth century) as the choice of weapon for burning or penetrating Nicholas's arse (backside) instead of Alison's, the intended victim. Morey (Reference Morey1995) has argued that the choice of tool echoes the use of the coulter for trial by iron, and forms a pun on cul (‘arse’) and coulter (/ˈkəʊltə/), and the phallic tool's function of penetrating the earth. In the Luttrell Psalter (Figure 8) and Langland's Piers Plowman (late fourteenth century) (Langland & Schmidt Reference Langland and Schmidt1978), the subject of communal agricultural labour, especially ploughing, is linked to concepts of penance, spiritual salvation and communal worship and devotion (Rentz Reference Rentz2010; Rhodes Reference Rhodes2014). Such later medieval associations support the analysis of plough-irons as emotants, and how their material properties operated within the relationships with their owners and wider society.

The Alnhamsheles and Massereene coulters were deposited during a period of social instability. The poor agricultural and demographic conditions (with particularly bad harvests) in the 1470s, 1480s and the early sixteenth century left people facing hardship and poverty (Campbell Reference Campbell, Bailey and Rigby2011; McIntosh Reference McIntosh2012: 17–19). The conditions, exacerbated by the lack of formal aid, forced small communities to rely on other forms of charity and the practices involving community-owned ploughs described above.

The medieval ceremonies and archaeological examples suggest that the emotions entwined with the coulter from Alnhamsheles and the meaning of its deposition were not an isolated or direct result of the destructive Scottish attacks, but were a mutual creation and re-creation of emotion and a wider social practice.

Finally, such depositions can be compared to the commonly encountered ‘concealed deposits’ in post-sixteenth-century buildings. These most often comprise shoes, articles of clothing, bottles (Hutton Reference Hutton2016) and, less frequently, tools. It seems that communal coulters lost their resonance and were no longer given prominence in emotional practices in post-Reformation Britain. Instead, the chosen emotants became more personal and individual. This perhaps represents a shift in the type of material emotants and a decline in communal emotional practices, or at least in their degree of elaboration and breadth of potential effect. This shift is also seen in other aspects of communal life in post-Reformation Britain: communal memory and events relating to the dead, for example, were devalued, and guilds, with their members’ shared identity and feelings of solidarity, declined (Duffy Reference Duffy2001: 106; Standley Reference Standley2013: 101; Rosser Reference Rosser2015).

Conclusions

The concept of ‘emotants’ represents an attempt to further our understanding of emotions. The case studies have examined emotion as a practice, using material evidence to explore emotional expectations, experiences and webs at both a broad and individual level.

The finger rings and their affective inscriptions direct our attention to the emotions that were expected and valued in romantic relationships. They formed part of the emotional performance of courtship, but also of pious devotion. Unlike plough-irons used as emotants, inscribed jewellery continues its emotant role into the present, as part of personal, rather than communal, emotional experiences. The rings were characterised by, and imbued with, their inscribed emotions, and could affect those who received them. They did not simply represent emotion; their presence could change or intensify feelings and maintain relationships. These emotants were prosopopoetic in that the rings ‘spoke’ the embedded emotions without their wearer needing to read the inscription aloud.

The broken plough coulter was an emotant used in Alnhamsheles in hope for the future and the fertility of the land on which the tool had once been used and was now embedded within. This allowed its matter to permeate the buildings, the landscape and its occupants (Standley Reference Standley, Gerrard, Forlin and Brownin press). The instability and risk of failed harvests may have created an environment of anxiety as a feature of the emotional practices at Alnhamsheles and Massereene, along with a feeling of hope. The plough-irons formed part of wider webs: the physical house and friary, the people in the communities, the iron material, the environment and landscapes, the crops, the draught animals, feelings of hope and security, and even joy at the survival and improvement of the communities. While the importance of ploughs in medieval literature is undeniable, the archaeological finds provide a new source of evidence. They allow us to investigate their use as emotants by communities and the wider society, and how religious upheavals contributed to a change in communal emotional practices.

My aim has been to present a new method to investigate emotions and develop ways of incorporating past feelings into our interpretations. The approach is also applicable to periods or societies for which we have no relevant documents or written record. An enquiry into materials, relationships and patterns of practice allows proposals to be made for how ‘things’ were emotants, and how emotional-material relations endured or changed over time: this includes not merely ‘reading’ archaeological objects but embracing the idea that material could, and can, be emotionally ‘felt’.