The 1911 satirical novel Operettenkönige begins with theft: an operetta melody is stolen. Sung in all earnestness by a young composer to his lover – an actress of questionable moral character for whom the omniscient narrator spares no scorn – it is stolen by an eavesdropping competitor who hides beneath the composer’s window. It started its life as a token of genuine affection, but as soon as it escapes into the Viennese air it becomes a valuable commodity, generic enough to be planted anywhere but specific enough to possess its own exchange value.1

Such is the paradox of operetta production: defined by its critics as formulaic and promiscuous but by its creators and audiences as possessed of a unique romanticism and the mark of genius. Viennese operetta, more than its French or English counterparts, was marked by a tension between the demands of high and popular art. Despite its genuinely commercial nature, composers and librettists frequently seized on the discourse of high art as a way to elevate their own critical prestige. This usually backfired, but the production process itself is marked by a pull between the individual creator and the ruthlessness of commerce.

This chapter offers a practical introduction to the production of operetta in twentieth-century Vienna. By the turn of the century, the city’s operetta world had developed into an industry with its own economy and division of labour. This is apparent from a host of sources ranging from newspaper and magazine stories to the memoirs and letters of librettists and composers. Though the documentation of the creation of any individual work can range from sparse to nonexistent, together these sources form a relatively consistent and complete picture of the composition and performance of an average operetta. In most respects the operetta industry operated in a regularized manner – there is even a cartoon depicting Lehár as the boss of an ‘operetta factory’. The wall appears to be a theatre box office, with each ticket labelled after a different Lehár operetta. The latest is Eva, which dates the caricature to around 1911–13.2 But the reception of operetta was more comprehensively preserved than its production process, for which sources of information remain scarce. Financial records in particular are lacking, and while general economic practices can be pieced together, it is usually not possible to track the box-office takings of any particular work.3

This chapter is intended to demystify a process often obscured by myth and scorn as well as to illuminate the many constituents involved in operetta production and some of their (often conflicting) interests. I begin by surveying the people involved in writing an operetta; then turn to the conventions of the silver-age operetta text itself; then the theatres, publication and economics of the operetta world and, finally, survey the reception and audiences who bore witness to the industry’s products.

Librettos and Librettists

Viennese cafés were the nerve centres of production. An undated engraving by Sigmund von Skiwirczynski depicts no fewer than twenty-four operetta luminaries positioned around a few tables in the Café Museum, labelled ‘The Fixed Stars of Viennese Operetta, Surrounded by Their Satellites’.4 During the silver age, the fixed stars of librettos included Victor Léon, Leo Stein, Alfred Grünwald, Julius Brammer, Robert Bodanzky, Alfred Maria Willner, Fritz Löhner-Beda and Heinz Reichert. Many operetta librettos were written in such cafés, where ideas and information were traded and collaborations made and broken. Librettists were typical café-goers: bourgeois, educated and almost all Jewish.5 When embarking upon an operetta, most librettists worked in pairs, one taking primary responsibility for the plot structure and spoken dialogue (Prosa) and the other writing the verse song texts, and both critiquing each other every step of the way – a process that ensured a degree of quality control but also homogenization. Dialogue librettists often began their careers as playwrights, and song-text librettists as poets or songwriters, but the division was not absolute. Some librettos were the production of a single author (most often Victor Léon, the most influential, prolific and experimental of all Viennese operetta librettists), and some are credited to three or more.

Relatively few operetta librettos were original subjects though as plots became more formulaic over the course of the twentieth century newly invented librettos became more common. The most popular source was, by far, middlebrow theatre, particularly French boulevard theatre such as that of Meilhac and Sardou. This genre was in fact the equivalent of operetta in spoken theatre: it was targeted at a similar audience and sometimes even played in the same theatres.6 These plays’ tidy plots, conventional character types and decisive endings (usually finishing with marriage) became the template for many operettas. Librettists also based operettas on short stories or novels or fitted historical figures or events into an operetta format.

Sometimes the source was credited, but often, in the interest of preserving more of the royalties for the new librettists, it was not; librettists hoped their sources would be obscure enough not to be noticed. Such ghosting was well known enough to be frequently joked about in theatrical circles. Shadow sources ranged from yet more French plays to a novel by a ‘Spanish writer who has been dead for more than thirty years’.7 Were the librettists to be caught stealing, they could be met with legal action by the original authors or their estate. The ‘foreign basic idea’8 that was credited with the plot of Die lustige Witwe was recognized immediately by critics as Meilhac’s familiar play L’attaché d’ambassade, though Meilhac’s estate sued the librettists only after the operetta became a massive hit and there were prodigious sums to be had.

Composers

Operetta resists the auteur framework, but composers, nonetheless, are usually identified as the single most important figure in an operetta’s composition and production. (Librettos were usually written first and then marketed to a composer.) Most nineteenth-century operetta composers had little formal compositional training, their backgrounds usually being in groups such as salon orchestras and military bands. In the silver age, however, most composers came to operetta after conservatory study as art music composers and thus possessed larger compositional toolboxes. After completing their training, almost all of their biographies continue in fits and starts and odd musical jobs that typify most early careers in composition. Many operetta composers also tried their hand at writing opera, with varied results. Along the way, they discovered a knack for writing in a popular style and turned to it full time.

The first operetta composer to have a background in art music composition was Richard Heuberger, best known to scholars as second-stringer to Eduard Hanslick at the Neue Freie Presse and as the director of the Singakademie and Wiener Männergesang-Verein.9 After training as an engineer, Heuberger studied composition with Robert Fuchs in Graz. Of his many operettas, his only major success was Der Opernball in 1898, one of the most important works of the transitional period between the golden and silver ages. Unlike Heuberger, Franz Lehár and Leo Fall were both military bandmasters in the Austro-Hungarian armed forces as well as orchestral composers; Fall, Oscar Straus and Emmerich Kálmán all came to operetta after first experimenting with cabaret songs (Straus and Fall in Berlin, Kálmán in Budapest). But all had studied at conservatories and written some ‘serious’ music before delving into operetta.

It should be noted that the post-conservatory experiences that led these composers to operetta – conducting in provincial theatres, orchestrating light music, working in military bands and playing for cabarets – were hardly unique, and in fact identical to the background of many of the era’s composers of art music. Mahler conducted numerous operettas in his early career, as did Webern.10 Alexander Zemlinsky worked as an orchestrator and also served as Kapellmeister at the Carl-Theater for two seasons; Zemlinsky’s orchestration of Heuberger’s Der Opernball amounted in some places to co-authorship, as Karl Kraus even noted publicly.11 (Although Kraus implied that Heuberger required assistance due to a lack of technical skill, the evidence suggests that poor time management was an equal if not greater factor.)12 Even Arnold Schoenberg worked for the Über-Brettl cabaret in Berlin and orchestrated operetta (inspiring his Brettl-Lieder).13

Whereas both Schoenberg and Mahler seem to have looked back at their periods in light music with fondness, other composers saw it as a period of indentured servitude before their true talents were recognized. Webern, for example, associated operetta with toil in the provinces, referring to operetta as ‘Dreck’ (muck).14 While it should not be surprising that assistant conductors and orchestrators were not allowed space to demonstrate their creativity or that working conditions in provincial theatres were often bad, these poor experiences are vital background for the same composers’ later condemnations of operetta.

Orchestration

As noted above, many operetta composers did not orchestrate their own work, though Franz Lehár, Emmerich Kálmán and Leo Fall, three of the most notable composers of the silver age, did. Some abstained due to, as Kraus implied, a lack of musical education, others due to lack of interest (operetta orchestration was often routine) or lack of time (as in the case of Der Opernball). Kálmán, Lehár and Fall all managed to do so and were abetted in their later careers by the luxury of time. Additionally, their fame was grounded in their handicraft and original voices – in which their command of the orchestra played an important role.

The issue of orchestration was a sensitive one for operetta insiders, a delicate topic in the operetta industry’s collective quest to be taken seriously as artists. In July 1926, an article in Die Stunde asked, ‘Who orchestrates Viennese operettas?’ The anonymous writer reports that a prominent unnamed Viennese music critic would, at the next assembly of the Association of Playwrights and Composers, demand that the names of anonymous orchestrators be listed in theatre programmes.15 This was motivated, the article detailed, less by a desire to give credit to the unnamed than to expose the many prominent operetta composers who were not capable of orchestrating their own music ‘because they cannot master the art of instrumentation’ (‘weil sie die Kunst der Instrumentations nicht beherrschen’) and to laud the real masters who could – Lehár, Kálmán and Fall, described as the ‘matadors of Viennese operetta’. The article goes so far as to name Vienna’s most popular orchestrators: conductor Oskar Stalla, Nico Dostal (later a successful composer himself) and ‘der Musiker Kopsiva’.16 No specific clients are named, though Stalla is described as having contracts with four prominent composers for the next season. It is unclear if the promised confrontation ever came to pass.

Templates

The basic recipe for a silver-age operetta was largely established by the success of Die lustige Witwe in 1905, as were the smaller-scale genre conventions. Some of these conventions existed well before Witwe, the most important earlier watershed moment being Johann Strauss Jr’s Der Zigeunerbaron (1885). However, in the twentieth century their deployment became more predictable.

A silver-age operetta generally centred on two couples. The ‘first couple’, played by the leading man (a low tenor or high baritone) and leading woman (soprano) are usually somewhat older and experienced in life and given music that was relatively demanding in vocal terms. The younger couple, a soubrette and a lighter ‘bon vivant’ or buffo tenor, are usually younger characters with less demanding singing parts, given more comic business and are often asked to do a great deal of dancing. (Die lustige Witwe is exceptional in this regard.) While the singers of these roles were often younger as well, some performers spent their entire careers in second-couple roles. The supporting roles generally include several Komiker, purely comic characters both male and female, some singing and some only speaking. There were even specific divisions of Komiker and Komikerin, such as the komischer Alter or komische Alte, the funny elderly person (such as Njegus in Die lustige Witwe and Mariza’s and servant Tschekko in Gräfin Mariza).17

Plot structure was also honed to perfection. Operettas were organized into three acts, opening with an overture or prelude followed by an introductory scene in a public setting in which a supporting character introduces the situation. The leading man and woman both sing entrance songs, and the secondary couple receives some material as well. The first act closes with a large finale, usually on an upbeat note with an acknowledgement of love between each couple. The second act opens with a large dance number including local colour, replicating Die lustige Witwe’s Vilja-Lied, and subsequently features ornate twists and turns in the plot.

In the tradition of the ‘well-made play’, these plot confusions often involve props or ‘devices’ such as letters, keys, miniature portraits, fans or lockets. There are usually one or two duets for the leading couple, and the act ends with the silver age’s most grandiose achievement: the infamous Act 2 finale. This is the operetta’s most ambitious musical structure and contains a melodramatic twist to end the act on a note of tragedy and pathos.18 Third acts often read as afterthoughts, vestigial structures that quickly tie up the plot. Their existence was frequently credited to a theatre’s imperative to sell refreshments during a second intermission, though eliminating the second intermission would also threaten the second-act finale.19 To maintain some interest, a new character known as the ‘dritter Akt Komiker’ is occasionally introduced, who tells topical jokes that have little or nothing to do with the rest of the plot, a throwback to the jailer Frosch in Die Fledermaus. A few lively musical numbers, often including dance, and a quick resolution of the plot finish up the operetta. There is no major Act 3 finale, merely a brisk reprise of an earlier number as a ‘Schlussgesang’ (closing song). See, for example, Kálmán’s Die Csárdásfürstin (1915) or Franz Lehár’s Eva (1911).20

These constructions were entirely self-conscious, and audiences and critics were as aware of them as composers and librettists. Operetta critics often attacked the dependence on ‘Schablone’ (stencils), but it seemed that this predictability was what audiences wanted. The authors’ skill was demonstrated in the use and development of these conventions. Were the waltz themes memorable? Was the instrumentation refined? How exciting was the twist in the second-act finale? Audiences expected certain thrills out of the operetta, and the authors were judged based on their ability to deliver the known features in a novel or satisfying way. Dramatic and musical patterns and habits that were for critics a mark of inartistic, mass production were, to operetta fans, beloved conventions of the genre.

Theatres and Productions

The Viennese theatres where operettas were produced were licensed private commercial enterprises, designated ‘k.u.k. [imperial] Privattheater’. Vienna had a seemingly insatiable appetite for performances, and, until the economic crises of the 1920s and the spread of sound film, more and more theatres were built. Theatres rarely closed down entirely, but they frequently changed artistic direction.21 While names often remained the same, programming constantly changed with fashions, ownership and artistic direction. For example, the Raimundtheater opened as a German nationalist Adam Müller-Guttenbrunn enterprise in 1893, became a spoken-word theatre in 1896, a home for visiting operetta troupes in 1900 and, finally, in 1908, was taken over by the management of the Theater an der Wien.

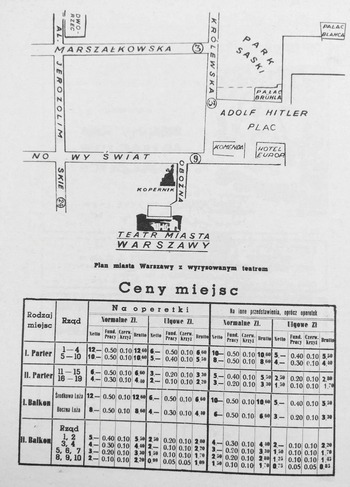

The closer a theatre was to the city centre, the wealthier an audience it could attract, the more media coverage it would receive in major newspapers and the higher ticket prices it could command. For operetta, the most prestigious stages were the Carl-Theater (whose name was not standardized and often appears as Carltheater) and Theater an der Wien, located in the Vorstadt but not far from the glittering centre. The Johann-Strauss-Theater, situated very near the Theater an der Wien, joined this elite rank when it opened in 1908. Further afield in the suburbs were the Theater in der Josefstadt, the Lustspieltheater and the Neue Wiener Bühne, playing similar, sometimes more mixed programmes with somewhat lower prices – and lower production values.22

The seating capacity of theatres varied; the Theater an der Wien was the largest at 1,859 spectators (reduced from its nineteenth-century capacity due to a renovation that replaced the roof and eliminated the top level), while the Carl-Theater and Johann-Strauss-Theater both accommodated around 1,200. The orchestra rosters of the three most important theatres hovered around forty-two members in 1910, while the less prestigious theatres averaged around thirty-five; however, it seems unlikely that all the members were playing on any given night. By the lean year of 1929, the Theater an der Wien’s roster had dropped to eighteen musicians and the chorus to a mere ten.23 Theatres also kept complete musical personnel on payroll including conductors, assistant conductors (often aspiring or semi-successful composers), accompanists and copyists.

Theatres maintained their own workshops for the construction of sets, costumes and props (with the occasional dramatic backdrop outsourced to one of the city’s scenic painters) and kept large stocks of items which were recycled for less prestigious premieres. Whether a work received the investment of new sets and costumes or not was taken as an indication of faith from the management in the work’s chances for survival.24 Operettas were even featured in fashion spreads in the ladies’ section of newspapers, where women could take cues on the latest styles from what glamorous stars like Betty Fischer or Louise Kartousch wore onstage.25

Economics and Publication

At some point in the composition process of a new operetta, the composer and librettists signed a contract with a theatre. In a typical contract, the royalties were divided evenly between composer and librettists, with the composer receiving half the authors’ portion and the two librettists splitting the other half. Contracts often included provisions for profits from sheet-music sales and later contracts included recordings, the rights for performances outside Vienna and film adaptations. Wilhelm Karczag and the Theater an der Wien in particular strove to create a vertically integrated operetta industry. Karczag (and his successor, Hubert Marischka) ran his own publishing house, Karczag-Verlag, which printed the scores of many (though not all) of the operettas his theatre premiered. The firm also received a cut from recordings. Sometimes Marischka even negotiated a share of the proceeds for himself.26

Although this enabled the theatre to reap a healthy profit from successful works, it eventually developed into a risky model. In the 1920s, when expectations for visual opulence rose, the theatre made extremely high investments in new productions. The upfront costs could not be recouped by ticket sales in Vienna alone and required revenue from other cities, sheet music and recordings. The catch was that only a work that gained the reputation of Viennese success would bring in this additional cash. A work that flopped or was only a moderate success in Vienna could result in catastrophic losses. Ultimately, this proved ruinous.

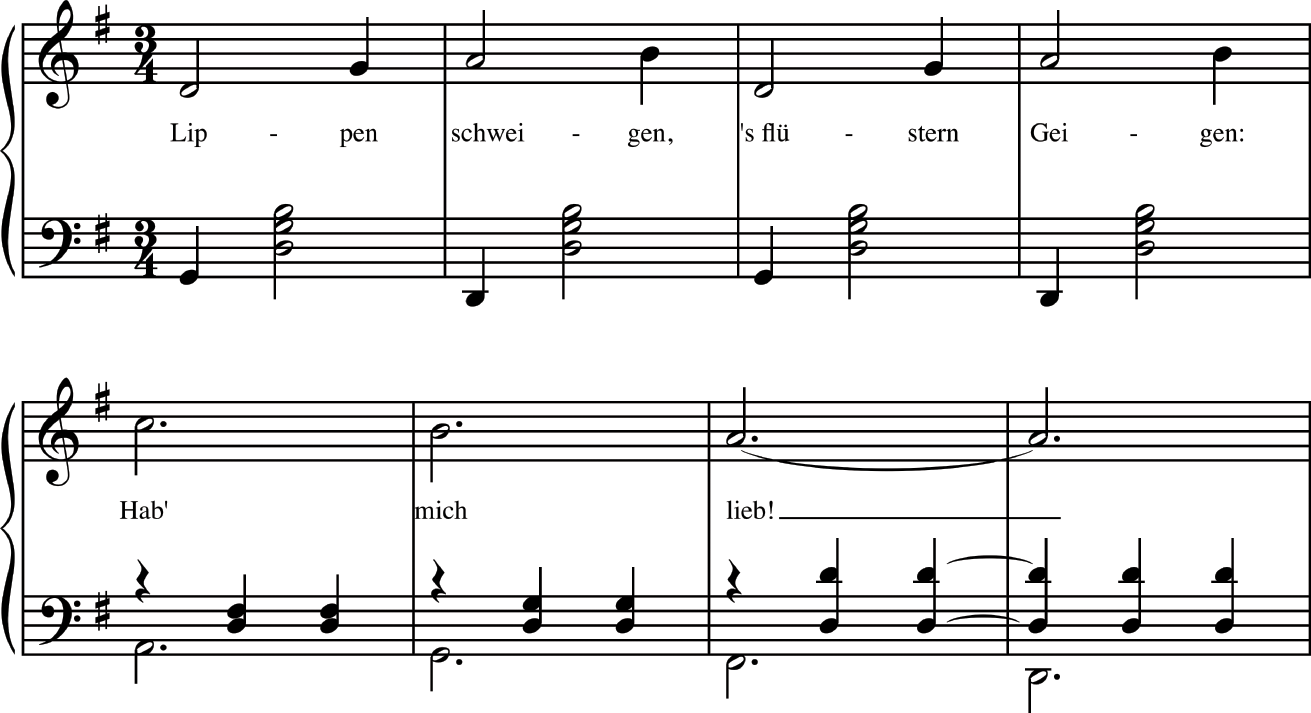

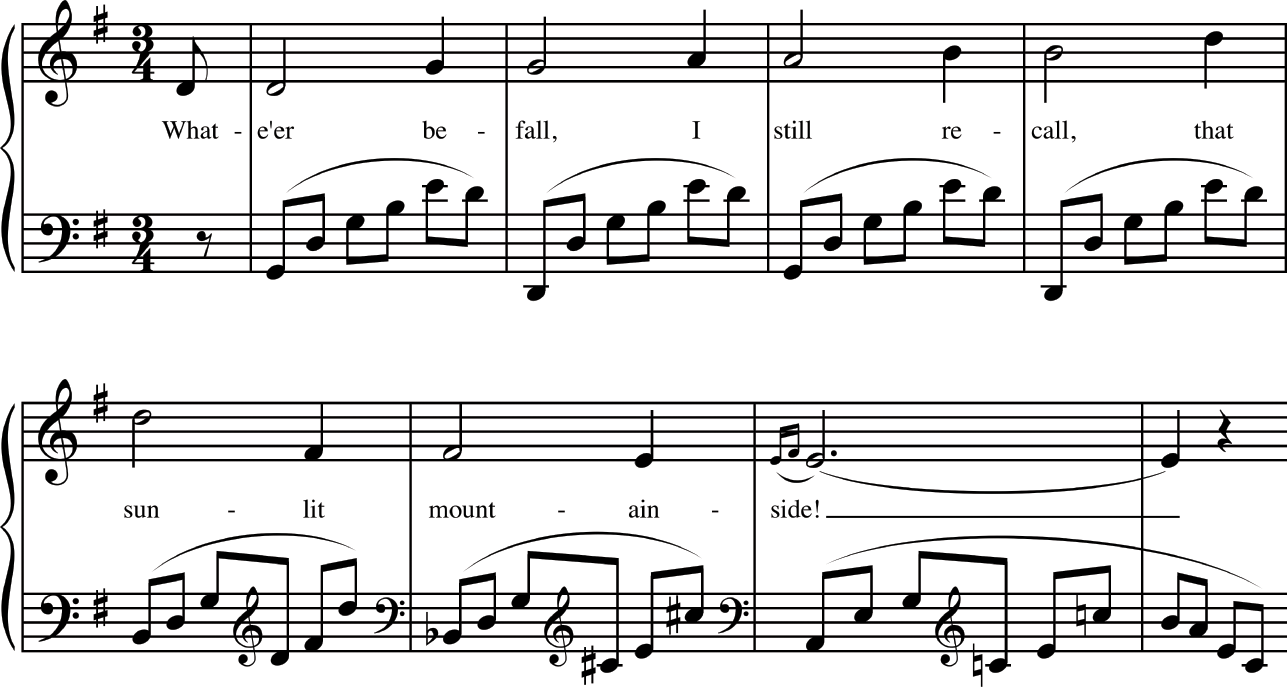

Publication was an important step for lasting success in operetta. Successful composers had standing contracts with publishers and published all of their work; new composers sometimes waited until they achieved fame. When an operetta was published, it became available to the general public in a variety of forms, including piano-vocal scores, piano solo arrangements with the text printed above the music but without a separate vocal line (Klavierauszug zu zwei Händen mit unterlegtem Text) and piano four hands with text. As well as the complete operetta, publishers also issued editions of excerpts, such as individual hit songs and short medleys of the most popular numbers. Potpourri arrangements for salon orchestra were also an important means of dissemination beyond the theatre.

After an operetta’s premiere, the final version of the text was printed as a Regie- und Soufflierbuch (direction and prompt book) or Vollständiges Soufflierbuch mit sämtlichen Regiebemerkungen (full prompt book with complete production notes). These librettos were not offered for sale to the public, as their copyright stated explicitly, but were rather available only on loan or rental to other theatres producing the works. (The public could purchase a shorter libretto containing only the song texts.) This controlled the operetta’s circulation, so the publisher could better collect royalties.27 The text contains detailed notes on the original production’s design and staging, which theoretically were to be replicated by provincial theatres to the greatest extent possible. Choreographies were sometimes published separately. The original staging was considered an integral part of the work, akin to the words or music, and the director responsible for the staging is noted prominently on the cover. But it is clear that for foreign stages directors adapted works for local taste and resources and that this versatility was important to its international appeal. For example, Stefan Frey surveys the international success of Die lustige Witwe, including the implications of changing casts, localized humour and eventual sound recordings and film.28 Printed librettos and staging manuals should not be considered definitive records of any production.29

Censorship

Strict censorship was legally mandated for all licensed Viennese theatres until 1919. An operetta’s spoken dialogue was first prepared in a typescript that was submitted to the police censor in duplicate for approval around a month before the premiere. The censor read the libretto, underlined any objectionable sections in red pencil on both copies and wrote a short summary and report on all the problems. One copy was returned to the theatre, the other was – thankfully for future scholarship – retained in the police’s archive. The libretto was then approved for performance on the condition that the librettists adopt the censor’s alterations. The law explicitly included visuals, music and gestures as well as spoken text.

Typically for the empire, the primary goal of the censor was to maintain public order and the appearance of harmony. The office had been established by an order issued during the Metternich era, on 25 Novembe 1850. Theatres were prohibited from ‘That which, in historical context, violates the need for public peace and order, that which insults public decency, shame, morality, or religion’.30 The censor forbade several specific categories of activity: directing the actors to perform any illegal action; displaying a lack of loyalty or respect for the state or the imperial house; disparaging patriotism, mocking or displaying hatred of any nationality, religion or social class; insulting public decency, godliness or morality; any display of real Catholic vestments or imperial uniforms; and libel against any living people.31 While this may seem sweeping, few scripts show many signs of the red pencil. Librettists were familiar with what was allowed and what was not and rarely seem to have pushed the envelope. This did not mean, however, that the censor’s rules did not play a large role in the subjects chosen.

The office of the police censor was eliminated following the empire’s dissolution. In an interview with the theatre magazine Komödie, mayor of Vienna Jakob Reumann described the censor as ‘the remnant of the old police state’, now outdated, and said that he believed that ‘the good taste of the public’ would serve as sufficient regulation for stage production.32 Whether there was actual freedom of expression, however, was questionable: an article in Die Stunde from 1926 entitled ‘The censor is dead! Long live the censor!’ pointed out that while the formal censorship process had ceased, the police still wielded the power to shut down any production deemed out of order and that any statement against the state or offence against public decency would prompt immediate action. (The anonymous author gives no specific examples.33) But operettas depicting real monarchs became common – such as Im weißen Rössl, Madame Pompadour and Kaiserin Josephine – ironically, nostalgic reminders of an era when they would have been disallowed onstage.

Critics and Criticism

Reviews were published in newspapers the day following premieres and were found in the theatre and arts section. Many of the critics responsible for these reviews were enmeshed in operetta society: several wrote librettos themselves and others penned biographies of composers, and conflicts of interest were common.34 While some reviews were anonymous, in most papers, critics were identified by their pseudonym (usually a few consonants from their surname).

Vienna had a notoriously large number of newspapers during this period.35 The most prolific coverage of operetta could be found in the Neues Wiener Journal, considered the most gossipy and female-targeted of the major broadsheets. A paper’s theatre coverage occasionally betrayed the publication’s overall political orientation, though most critics did not often espouse a prominent political agenda beyond bland centrist Liberalism. The more ideologically extreme papers are more easily labelled, such as the German nationalist Reichspost and the socialist Arbeiter-Zeitung (whose critic David Josef Bach is one of the most consistently interesting).

The most influential critics of the first decade-and-a-half of the twentieth century were Ludwig Karpath of the Neue Wiener Tagblatt and Leopold Jacobson of the Neues Wiener Journal, whose names and opinions were frequently cited by composers and librettists. In the 1920s, Julius Bistron and Ernst Decsey become more prominent. Table 12.1 lists the major critics of operetta from 1900 to 1930.

Table 12.1 Major Viennese operetta newspaper critics

| Newspaper | Pen Name | Name | Years Active |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neue Freie Presse | — | (reviews unsigned) | 1900s–1910s |

| L. Hfd | Ludwig Hirschfeld | 1920s–1930s | |

| Neues Wiener Journal | bs. | Leopold Jacobson | 1900–c.1910 |

| a.e. | Alexander Engel | c.1908–1920s | |

| -ron | Julius Bistron | 1920s | |

| Neues Wiener Tagblatt | -rp | Ludwig Karpath | 1901–c.1920? |

| E.D. | Ernst Decsey | 1920–1930s | |

| Dr. E.D. | |||

| Fremden-Blatt | st. | Julius Stern | c.1900–1919 |

| Österreichische Volks-Zeitung | A.L. | Alexander Landsberg | 1900s–1910s |

| St. | Julius Stern | 1919–1920s | |

| Deutsches Volksblatt | Sch-r. | Karl Schreiber | until 1922 |

| Arbeiter-Zeitung | D.B. | David Josef Bach | 1900s–1910s |

| Reichspost | (none) | Otto Howorka | 1910s–1930s |

Most reviews follow the same format. Operettas are first judged by their ability to fulfil the basic goals to amuse and divert (critics often mention whether the audience seemed to be enjoying themselves). Other basic requirements include the libretto’s pacing and plot twists, the composer’s ability to write a waltz, very often the quality of the orchestration (ironic since many operetta composers did not do this themselves) and the charisma, singing and dancing abilities of the actors. In longer reviews, critics endeavour to place the operetta in the context of its creators’ previous works. Composers receive the most attention. They are assumed to have particular strengths, weaknesses and identities, their mastery of the Viennese idiom is usually remarked upon and, if the composer in question was not native Viennese (as the majority of the major silver-age composers were not), his attempts to convince in what was considered a quintessentially Viennese language are assessed for their success.

Critical and public opinion often converged. Some works, however, were critical successes but popular flops; the opposite (critical flops and popular successes) was not common until the growth of the much-maligned revue operetta in the 1920s. For those critical of operetta as a whole – writers from more literary or serious musical circles who were generally not reviewing it on a daily basis – this collusion of criticism and market was one sign that marked operetta as non-art. Ultimately, it was the popular vote that determined how long an operetta would remain on the schedule.

Audiences

It is difficult to determine exactly the precise demographics of operetta audiences, but some details can be gleaned from contemporary accounts. While theatres did offer subscription tickets, the fixed box society of major opera houses did not exist in operetta theatres, nor did the quasi-patron power of those box holders. Some hints as to demographics can be picked up from the magazine Komödie, subtitled ‘Wochenrevue für Bühne und Film’. In 1921, Komödie published a list of readers who had won a contest. Eighty-four readers in all are listed as winners, with their names and addresses supplied. Out of this number, the largest number, 57 per cent, lived in the suburban Vorstadt, between the Ringstrasse and the Gürtel; 37 per cent lived outside the Gürtel and the remaining 6 per cent lived inside the Ringstrasse in the Innere Stadt. This reinforces the oft-stated assumption that the most devoted operetta audience was the middle class and lower middle class.36

Due to the city’s demographic changes in the late nineteenth century, the distribution of operetta audiences changed as well. In 1902, on the threshold of the silver age, Max Graf recorded a transformation of operetta taste over the past few decades, powered primarily by the streetcar.37 While nineteenth-century Vienna had been a patchwork of neighbourhoods, public transportation now tied the city together, and its population was more likely to claim an identity as Viennese or as an immigrant rather than allegiance to their home district. In Graf’s view, this had a chilling effect on operetta. While the audience had greatly expanded from a small circle of connoisseurs to a mass form, quality had decreased. What once was individual and specific – ‘the wit of Offenbach, the grace of Johann Strauss, the melodic cleverness of Millöcker’ – had, according to Graf, become mass-produced and generic, lowered to the folk music of a Viennese Heuriger.

Many operetta artists maintained that it was those in the gallery who made or killed an operetta, not the voices of the critics or even those who purchased the more expensive seats. Proportionately, this seems possible, since there were many more cheap seats than there were expensive ones. The silver age’s tendency towards Serienerfolgen – hit operettas that ran for years at a single theatre – certainly encouraged writing for large audiences. Serienerfolgen also required a theatre to draw a largely new group of audience members every single night, akin to a modern Broadway megamusical.38

Conclusion

As in the field of opera research, the multimedia nature of operetta can make its study a confusing experience. Due to operetta’s popularity and liminal role in the Germanic musical establishment, these sources are plentiful but are frequently scattered between departments in major libraries, often split between music and theatre collections. Several important archival collections, notably papers of librettist Alfred Grünwald and the photographic collection of librettist Victor Léon, are located in the United States (at the New York Public Library’s Billy Rose Theatre Collection and Harvard University’s Houghton Library, respectively). Sometimes these texts tell conflicting stories, surviving from various stages in the artistic process or concerning an ephemeral performance whose exact character will always remain a mystery. But the very plenitude of this written record and its occasional contradictions can provide a dynamic, lively view of a largely forgotten art form, one which is only beginning to be mined by scholars.

Paris has Jacques Offenbach, Vienna Johann Strauss and Franz Lehár, London Gilbert and Sullivan but which Berlin operetta composer has made an enduring international name for himself? Theatrically Berlin is associated either with high cultural, artistically experimental stage productions of the Reinhardt-Piscator school or, thanks to The Blue Angel and Cabaret, with cabaret. Berlin is much less associated with operetta and this despite producing some domestically as well as internationally very successful examples of the genre – why is this?

There is more than one reason. Firstly, Berlin entered the popular musical stage comparatively late in the last year of the nineteenth century, when Paris, Vienna and London had already successfully established themselves as capitals of popular musical theatre. Secondly, Berlin’s time in the limelight was comparatively short-lived. After 1933 the majority of its most talented composers, writers, actors, directors and managers either left the country or found themselves barred from the stage, if not faced with the threat of deportation and death because they were Jewish. Simultaneously, Berlin was cut off from artistic developments and markets in other countries. Finally, Berlin operetta, though popularly successful, lacked intellectual support. German critics either ignored or panned operetta as trite, vulgar, worthless mass entertainment. Long before Theodor Adorno took on the American culture industry, he cut his teeth excoriating Weimar era operetta.

Such judgements partly determined how operetta was seen after World War II and to some extent is still seen today. In contrast particularly to Britain and the United States, the Berlin operetta heritage was, apart from some die-hard enthusiasts, not preserved and celebrated. This might also partly have to do with operetta’s association with stuffy Victorianism and, worse still, National Socialism (Hitler was a known operetta lover). A younger generation dismissed the German tradition in popular entertainment as old-fashioned, bourgeois and fascist, embracing American rock and roll and, if they cared at all for musical theatre, Broadway musicals. While some operettas, especially those by Offenbach and Strauss, were performed by opera houses and became a mainstay of provincial theatres, no self-respecting intendant would have dreamed of touching Berlin operetta. This has changed since the 2010s, when Berlin-based directors like Barrie Kosky at the Komische Oper or Herbert Fritsch at the Volksbühne began to revive the lost tradition of local popular musical theatre, drawing attention to its subversive potential. However, as this essay will show, there is still a lot to rediscover. It starts off by looking at the early history of Berlin operetta before focussing on the period between 1900 and 1933. It concentrates on the most important works, theatres, composers, writers and managers and the international traffic in operettas.

* * *

Around the middle of the nineteenth century, Berlin, the capital of Prussia, was by far the largest German city with just over 400,000 inhabitants. However, it was only after the Franco-German war of 1870–1, when Berlin became the capital of a unified Germany that it began to grow both in population and in political and cultural importance. When World War I broke out, it was the third largest European city after London and Paris. Its rapid growth gave the city a new and modern appearance, especially compared with older European cities. Mark Twain compared it to Chicago. This growth was largely due to immigration from rural parts of Germany, particularly from eastern territories such as Silesia. As many of the newcomers were Jews the make-up of the city changed and became much more cosmopolitan.

Fast-growing Berlin was a city in search of an identity. In this process, media took on a particular importance. The popular press demonstrated how to find one’s bearings in the new – and, for many people from the countryside, certainly also frightening – environment, contributing to what one sociologist has called ‘inner urbanization’.1 The theatre fulfilled a similar function. Inventing Berlin characters, using Berlin dialect and representing Berlin problems on the stage, it held up a mirror to old residents and newcomers alike and helped them to come to terms with the changing city and their roles in it. It was on the stage that Berlin first claimed to be a metropolis on a par with the other capitals of the world. When the writer David Kalisch gave one of his farces the subtitle ‘Berlin becomes a world city’, it was meant as a joke.2 Soon, however, it became a rallying call for Berlin’s ambition to be on an equal footing with Paris and London.

Obviously, Berlin was not as politically and economically important as London, the heart of a global empire, and it was certainly not as beautiful as Paris (even many Berliners decried its ugliness). Neither could it look back on as long a history as these cities. But in the fields of entertainment and nightlife it claimed to surpass both – a bold claim given Paris’s status in that regard. Population growth, the gradual rise of wages and the increasing leisure time produced an ever-growing demand for entertainment, which led, in a comparatively short span of time, to the opening of many new theatres, variety theatres, music halls and countless cabarets, pubs and summer gardens. Depending on location, size and ticket prices, these venues were showing local as well as international entertainments, among them many operettas. Offenbach was as popular in Berlin as anywhere in Europe, and both he and Johann Strauss conducted their works in Berlin. In 1886 an English touring company brought The Mikado to Berlin. Despite performing in English, this visit was a big success, prompting some journalists to question why German writers and composers were unable to produce similar entertainments.

It would take another decade for Berlin operetta to emerge and two decades until it would reach other countries. Paul Lincke is often seen as the father of Berlin operetta and is practically the only composer of Berlin operettas born in Berlin. He started out as a musician, playing the violin and bassoon. He then moved into light music, composing as well as conducting the orchestra of the Apollo-Theater, one of Berlin’s foremost variety theatres. As a conductor, Lincke was a dandified showman, always appearing in his trademark black coat-tails, top hat and white gloves. Surprisingly, for someone so strongly associated with Berlin, he moved to Paris for two years, where he conducted the orchestra of the Folies-Bergère, Europe’s foremost variety theatre. After his return to Berlin in 1899, Lincke had his first big success – and, indeed, the biggest of his career – with the operetta Frau Luna. Originally a one-act piece and part of a variety bill, Lincke would expand and adapt the score throughout his life.

Frau Luna successfully brought together a mixture of influences, namely operetta of the French and Viennese school and Berlin burlesque. What the cancan had been for Offenbach and the waltz for Strauss, the march became for Lincke. His most famous was ‘Das ist die Berliner Luft’ (This is the Berlin air) by which, to quote the historian Peter Gay, Lincke ‘did not have meteorology in mind but an incontestable mental alertness’.3 Lincke wrote for Berlin audiences, and Berlin was the topic of his operettas. Frau Luna featured typical Berlin characters speaking in Berlin dialect, such as the engineer Fritz Steppke, who invents a balloon and flies to the moon with his friends, where they get up to all kinds of mischief. It was adapted in Paris (as Madame de la Lune in 1904) and in London (as Castles in the Air in 1911) but – probably because of its Berlinness – did not find much success in either city.

Trying to capitalize on his success, Lincke quickly turned out a string of operettas, most of which followed the same plot of the bumbling comic young Berlin man blundering into some exotic locale. More important than the plot was that most of them had at least one or two hit songs eagerly picked up by dance orchestras and barrel organists, who turned them into bona fide folksongs one could hear at every street corner of Berlin. In due course, Lincke became rich and founded his own publishing house, but with success his productivity decreased until he wrote hardly anything new.

While Frau Luna is still remembered and regularly performed today, the same cannot be said for the operettas of Lincke’s contemporary Victor Hollaender, who is chiefly remembered as the father of the better-known writer and composer Friedrich Hollaender. From a Jewish family in Silesia, Hollaender came to Berlin to study music. Afterwards he worked as a conductor in Germany, Europe and the United States and wrote music for the stage. In 1899 he settled in Berlin, where he became the house composer of the Metropol-Theater.

The Metropol was the first Berlin theatre to stage annual revues, a genre imported from Paris which satirized social, political and cultural events of the past year. The Metropol revues quickly became the toast of Berlin and attracted visitors from all over Germany. They also launched the career of Fritzi Massary. The daughter of a Jewish merchant from Vienna, she became one of the biggest German theatre stars and the German operetta diva both before and after World War I.

For a while Hollaender was one of the most popular German composers, earning enough money to build a mansion in the expensive Grunewald district on the outskirts of Berlin. Some of his songs were international hits, such as his ‘Schaukellied’, written for a revue in 1905. It became popular in Britain as ‘Swing Song’ and as ‘Swing Me High, Swing Me Low’ in the United States, where Florenz Ziegfeld incorporated it into his Follies of 1910.4 His operettas, however, were less successful and after World War I he found it increasingly difficult to keep pace with changing musical tastes.

Even before the war, Lincke and Hollaender began to be sidelined by a new generation of Berlin composers, namely Walter Kollo and Jean Gilbert. Like so many of his peers, Kollo began by working and writing for the thriving cabaret scene, soon moving into the theatre. His first success was Große Rosinen (Big Raisins) in 1911, followed by the even bigger success of Wie einst im Mai (Like One Time in May) in 1913, which told the story of two Berlin families over four generations. Kollo continued very much in Lincke’s vein, writing operettas about Berlin for Berliners.

Kollo’s biggest rival was Jean Gilbert, the most prolific of all Berlin operetta composers. Born as Max Winterfeld in Hamburg in 1879 into a Jewish family, Gilbert was hardly eighteen years old when he started to conduct at provincial theatres and began to compose. His first success, Die polnische Wirtschaft (literally Polish Business but really ‘monkey business’) of 1910, ran for 580 consecutive performances, an enormous number for Berlin at that time. The next year’s Die keusche Susanne (Chaste Susan) was even more successful. Based – as so many Berlin operettas were – on a French farce, it mocked the moral reformers of the day. Gilbert may, as his critics alleged, not have been a first-rate composer, but he certainly knew what the audience liked, and he was more than ready to give it to them, turning out two or more operettas per year, touring with his orchestra and producing an endless outpour of gramophone recordings.

In the years preceding World War I, Kollo and Gilbert wrote at least one successful operetta each year – once even about the same subject: the rise of the film industry. Kollo’s operetta Filmzauber, premiering in 1912 at the Berliner Theater, told the story of a dodgy film director, whose ill-fated attempt at shooting a biopic about Napoleon produces comic confusion. It was followed by Gilbert’s Die Kino-Königin (The Cinema Star), in which a businessman campaigning against the dangers of the cinema is secretly filmed wooing a diva only to become an involuntary film star himself.5 Much has been made of the competition between the popular stage and the cinema at the time as well as retrospectively. Yet, while happy to mock the film industry, operetta composers did not hesitate to work for the new medium. Walter Kollo wrote the score for a dozen films, while Jean Gilbert was under contract by a film studio as Die Kino-Königin came out. Indeed, operetta had a remarkable impact on the early German film industry. Already during the silent film era many operettas were turned into films.

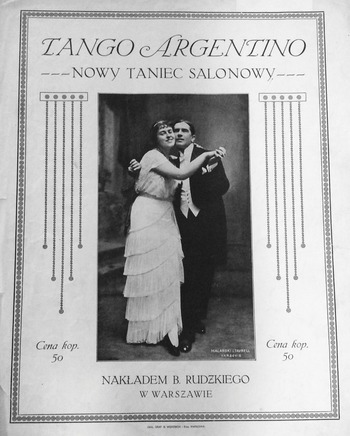

For operetta, and especially for Berlin operetta, to tackle a contemporary subject like the cinema was not unusual. On the contrary, pre-war operetta delighted in taking up topical phenomena, fashions and fads. With the beginning craze for North as well as South American dances, European composers felt compelled to utilize the new rhythms. Jean Gilbert, for instance, used the tango in an operetta titled Die Tangoprinzessin (The Tango Princess). Yet, despite Lincke’s penchant for the march, Berlin operetta capitalized on the waltz as much as Viennese operetta.

Gilbert’s works were more cosmopolitan than those of the Berlin-centric Kollo. Die keusche Susanne was set in Paris, Die Kino-Königin in Philadelphia. This might have helped them to be adapted abroad. However, operettas by both these composers increasingly found their way on to the stages of other European cities, thanks not least to the enormous global success of Franz Lehár’s The Merry Widow in 1907. Suddenly, every theatre manager in Europe and even outside Europe became aware of the selling power of German operetta. Whether they originated in Vienna or Berlin often did not make much of a difference. Gilbert’s Die keusche Susanne, for instance, played in Vienna and in Madrid (La casta Susanna) in 1911, in Warsaw (Cnotliwa Zuzanna) in 1911, in London (The Girl on the Film) and in Budapest (Az ártatlan Zsuzsi) in 1912, in Paris (La chaste Suzanne) in 1913, in Sydney in 1914 and in New York (Modest Suzanne) and in Naples (La casta Susanna) in 1915. In the summer of 1914, four West End theatres were showing operettas by Kollo and Gilbert. As composers realized that there was money in international sales, they reacted by writing less locally specific, more universal operettas.

Composers benefited from the overall growth of the theatre industry across Europe. The growing number of theatres led to a growing demand for new content that the domestic market was often unable to satisfy. Theatre managers therefore increasingly looked abroad for new shows, especially as theatre became more and more costly. A show that had succeeded elsewhere raised hopes that it would be successful once more. Managers, publishers and agents eagerly observed what was going on abroad and stayed in constant contact with their colleagues in other countries. The internationalization of the theatre industry, then, was driven by its development into a big – potentially extremely profitable, potentially hazardous – business. Nothing illustrates better how international it had become than the situation operetta theatres found themselves in when World War I broke out. Many had to withdraw current shows because they had been written by composers from now enemy nations and were no longer welcome. Often these shows were replaced by well-established classics or by improvised patriotic shows, which leant more towards revue than operetta.

In Berlin, both Kollo and Gilbert wrote jingoistic shows calculated to raise the morale. This in turn made their operettas even less acceptable in London and Paris. With habitual celerity, Jean Gilbert, quickly exchanging his French-sounding pseudonym for his original German name, turned out the music for two war plays in 1914: Kamrad Männe (War Comrade Männe) and Woran wir denken (What We Think Of). Like most war plays, Kamrad Männe took its cue from the mobilization of the army. Its first act took place before, the second during and the third right after the declaration of war, showing how Germans from all classes and regions – and especially Germans and Austrians – stood together. Popular theatre actively contributed to the war effort or at least did its best to make it appear that way to make people forget how international and cosmopolitan it had been before the war.

Like Kamrad Männe, Walter Kollo’s Immer feste druff! (Beat Them Hard!) invoked the solidarity of all German people. It ran for over 800 performances, from October 1914 all through the war till the abdication of the German emperor. This was unusual because audiences quickly got tired of propaganda as the war dragged on and began to favour escapist, sentimental plays that enabled people to forget the war for two or three hours. The two biggest wartime hits, Die Csárdásfürstin and Das Dreimäderlhaus, couldn’t be further removed from the reality of war. Originating in Vienna, they were performed over 900 times in Berlin.6

The war years were very good years for the Berlin popular stage. Both people at home and soldiers on leave flocked to the theatre for entertainment and distraction. The slump came with looming defeat and the spread of Spanish influenza in 1918. People were scared to go to the theatre, and the box office turned sour; its fortunes improved only in the economically relative stable twenties.

After the war, Berlin became the capital of the now democratic Germany. Much like the country, its capital was rapidly changing. With the Greater Berlin Act of 1920, the city incorporated a lot of suburbs – some of them cities in their own right – and rapidly grew to more than four million inhabitants. It was now one of the largest cities in the world, almost the size of Paris. The hedonism that followed post-war austerity expressed itself on the stage in the form of grand, spectacular revues. Thanks to the abolition of theatre censorship in 1918, they could freely revel in an abundance of naked flesh never seen before or since on the Berlin stage. But apart from this, in their bombastic scale and their even more fragmented plots, they continued a pre-war tradition.

This was true for Weimar culture in general, which was not as new and original as may appear retrospectively. It often drew on forms and genres of the imperial period, and some traditions from that period not immediately associated with Weimar culture continued in the post-war period. Weimar theatre, for instance, was not all spectacular shows, avant-gardist agitprop or candid cabaret. To take an example, the fad for revues did not last very long. With the onset of the economic depression in the late twenties, shows flaunting extravagant opulence no longer seemed appropriate. All this time operetta remained a mainstay of Berlin theatres and reached a new peak in both output and popularity.

Berlin now even outstripped Vienna as operetta capital. This had partly to do with Vienna’s loss of political and cultural importance and partly with Berlin’s new status. With its enormous audience, its dynamic theatre industry, its star actors, its theatre publishers and its links to other capital cities, Berlin became the foremost theatre city in the German-speaking world. It is therefore not surprising that many Viennese composers decided to bring out their new pieces in Berlin. Franz Lehár’s later works, for instance, such as Friederike (Frederica, 1928) and Das Land des Lächelns (The Land of Smiles, 1929), premiered at the Metropol-Theater. The main part in both operettas went to the tenor Richard Tauber, who had started out as an opera tenor before becoming the most famous male operetta star of interwar Europe. He also appeared in the London adaptation of The Land of Smiles in 1931. Subsequently, he became a regular guest on the British stage, emigrating to London in 1938.

Oddly, Tauber never appeared together with the other big operetta star Fritzi Massary. Her career, substantial even before the war, now reached a new height. Oscar Straus practically wrote exclusively for her, beginning with Der letzte Walzer (The Last Waltz) in 1920 and culminating in Eine Frau, die weiß, was sie will (A Woman Who Knows What She Wants) in 1932, in which she played what could be called a disguised self-portrait: an ageing operetta diva with an illegitimate daughter. In between, Massary starred in Leo Fall’s Madame Pompadour.

While Lehár, Straus and Fall as well as Kollo and Gilbert continued to be active in the interwar period, a new generation of composers emerged with Hugo Hirsch and Eduard Künneke leading the way. Hugo Hirsch, like many other operetta composers of Jewish descent, burst on to the Berlin scene in the 1920s. His operetta Der Fürst von Pappenheim (The Prince of Pappenheim, 1923), partly set in a department store, partly at a seaside resort, delighted audiences in Berlin and elsewhere. In the following year, four Berlin theatres premiered operettas by Hirsch.

After studying music in Berlin, Eduard Künneke worked as a music teacher and conductor writing music on the side. His first operetta, Wenn Liebe erwacht (Love’s Awakening), came out in 1920. It was followed by Der Vetter aus Dingsda (The Cousin from Nowhere) in 1921, Künneke’s biggest success. Despite its well-tried mistaken-identities plot, Der Vetter aus Dingsda seemed fresh because it broke with the sumptuous wartime operettas by reducing the ensemble and the sets, by doing away with the chorus and by incorporating new musical styles like the Boston, the tango and the foxtrot.

World War I had severed the network between the theatre industries of the warring nations. Soon, however, managers set out to revive it. In 1920 the British impresario Albert de Courville, eager to import German operettas, wrote to The Times:

are we still at war with Germany or not? America evidently thinks not. I am told that Lehár is going over and Reinhardt has been invited. Are we in the theatrical world free to buy plays from the late enemy in the same way as we buy razors? Are we at liberty to reawaken public interest in a class of show highly delectable before the war?7

De Courville’s answer to this question was, of course, an emphatic yes. As anti-German resentment began to fade, he and his colleagues imported the latest successes as well as the wartime hits British audiences had missed out on due to the boycott of German culture. In 1921 Wenn Liebe erwacht ran in London as Love’s Awakening, followed, in 1922, by Gilbert’s Die Frau im Hermelin (The Lady of the Rose) and Straus’s Der letzte Walzer (The Last Waltz), in 1923, by Der Vetter aus Dingsda (The Cousin from Nowhere) and Fall’s Madame Pompadour, in 1924 by Der Fürst von Pappenheim (Toni), in 1925, by Straus’s Die Perlen der Kleopatra (Cleopatra) and Gilbert’s Katja die Tänzerin (Katja the Dancer), in 1926, by Gilbert’s Yvonne (specifically written for the West End), and in 1927, Mädi (The Blue Train) by Robert Stolz (1880–1975). Most of these plays were also adapted in Paris, New York and other cities.

Undeniably, Berlin had returned to the centre of international popular musical theatre. Not all of these plays fulfilled the expectations their continental success had aroused, though. Consequently, in the late 1920s, slightly fewer Berlin operettas crossed over to Britain and the United States. The fate of Eduard Künneke was in many ways representative. Thanks to the success of The Cousin from Nowhere, managers abroad hired him to write for their theatres, something few composers before him had experienced. He wrote The Love Song (1925) –effectively a medley of Offenbach songs – and Mayflowers (1925) for Broadway and Riki-Tiki (1926) for the West End. Unfortunately for Künneke, neither of these efforts resonated with audiences, and so he returned to Berlin.

Though the 1920s saw a lot of new operettas by well-known as well as younger composers, they were mainly associated with spectacular revues. If pre-war Metropol revues had been praised for their lavishness, the revues of the twenties were bigger in every sense: with the most numbers, the most expensive stars and settings, the latest dance rhythms and the longest chorus lines. It was one long glorious summer between post-war inflation and the Depression of 1929. No one did more to push the genre to its limits than Erik Charell. Charell had started out as a dancer and actor in Max Reinhardt’s ensemble. After Reinhardt’s plans to bring the classics to the masses had faltered, Reinhardt asked Charell to take over the management of the Großes Schauspielhaus, which with 3,500 seats was Berlin’s biggest theatre. Charell did not baulk at the challenge. He believed he knew what the masses wanted. He began to stage revues aspiring to be larger, more inventive and spectacular than those of his competitors. He also began, in 1926, to overhaul hits from the pre-war era such as The Mikado, Wie einst im Mai, Madame Pompadour and Die lustige Witwe by giving them the revue treatment, creating what came to be called revue-operetta. While some Berlin critics enthused over his Mikado, the Berlin-based British critic C. Hooper Trask was incensed: ‘Outside of the necessary modernisation of topical allusions, hacks of the Austrian operetta factory should be made to keep their paws where they belong’, he chastised Charell.8

The Mikado was followed by Casanova in 1928, Die drei Musketiere (The Three Musketeers) in 1929 und Im weißen Rössl (White Horse Inn) in 1930 –success, success and yet more success. To stage Im weißen Rössl must have sounded like a risky idea, based as it was on a farce from the 1890s about the adventures of some Berlin tourists in the Austrian Salzkammergut. Its success speaks much for Charell’s artistry as a director and his feel for popular tastes. However, Charell did not take any chances, bringing together some of the best writers Berlin had to offer at that time, such as the universally talented Ralph Benatzky, a composer, lyricist, writer and poet, who had already collaborated with Charell on his previous productions. Im weißen Rössl had everything: a well-tried plot and topical jokes; sentimental songs and topical dance tunes; the old emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria, who embodied the retrospectively idyllic pre-war Europe, and a modern jazz band. But especially it had settings no one had ever seen before, settings that grew from the stage into the auditorium. Even the exterior of the theatre became part of the show, as the Großes Schauspielhaus was made to look like an Alpine inn.

While Charell modernized well-known operettas, new operetta composers began to appear on the scene. The most talented of them was the Hungarian Paul Abraham. Abraham had begun by writing chamber music, but this only got him a job as a bank clerk. It was his Viktoria und ihr Husar (Viktoria and Her Hussar) that saved him from a fate behind the counter and brought him to Berlin via Vienna. The first piece he wrote for the Berlin stage was Die Blume von Hawaii (The Flower of Hawaii) about the Hawaiian princess Layla, who had been deposed from the throne by the US Army. In the end, Layla decides against a plot to reinstate her, renounces the Hawaiian throne and moves to the French Riviera. This plot was somewhat reminiscent of Germany’s own recent history: former emperor Wilhelm II, who had been disposed in 1918, now lived in the Netherlands, where he passed his time chopping wood.

Die Blume von Hawaii was a big success, as was Abraham’s following operetta, Der Ball im Savoy, about a couple suspecting each other of infidelity in the comfortable surroundings of the French Riviera. Abraham was an inventive composer. While effortlessly turning out sprightly waltzes, he was also open to new influences, making use of new American dances – the tango and the pasodoble being favourites – and instruments like the saxophone, almost unheard of in operetta before. He also profited from working with two experienced librettists, Alfred Grünwald and Fritz Löhner-Beda.

It is a matter of debate whether an overview on Berlin operetta should also include Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s Die Dreigroschenoper (The Threepenny Opera). The title identifies it as an opera, but the Dreigroschenoper was much closer to operetta, not least because it was not through-composed but a play with songs. Weill himself admitted that he and Brecht wanted to break into the commercial theatre industry to reach a wider audience. The communist director Erwin Piscator had led the way in the mid-twenties by appropriating revue in the hope of revolutionizing the masses and spreading communist ideas. Now Brecht and Weill followed his example with operetta.

The Dreigroschenoper, based on John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera and set in Victorian London, but really about Weimar Berlin, was an overnight success and some of its numbers became instant Schlager, hit songs. Four months after its premiere in Berlin, it ran in nineteen German cities. In the summer of 1929, there were allegedly 200 productions together accounting for more than 4,000 performances. Politically, however, it was less successful. The bourgeoisie it lampooned either did not get or ignored its political message. In 1933, Mack the Knife (aka Adolf Hitler) became chancellor, the Dreigroschenoper was cancelled and its authors fled the country.

The Dreigroschenoper reached the London stage only in 1956, and then it was not very successful. Brecht’s clichéd fantasy version of Soho must have struck British audiences as very strange indeed. In contrast, many of the successful Berlin operettas of the late twenties and early thirties were almost instantly adapted abroad: Lehár’s Friederike (Frederica) in London in 1930, Das Land das Lächelns (The Land of Smiles) in London in 1931 and Paris in 1932, Straus’s Eine Frau, die weiß, was sie will in London (as Mother of Pearl) in 1933 and Abraham’s Ball im Savoy (Ball at the Savoy) in London in 1933.

The popular success of Charell’s Im weißen Rössl also caught the attention of the British manager Oswald Stoll. Stoll was looking for a show to revive the fortunes of the Coliseum Theatre, the floundering flagship of his entertainment concern. With 2,500 seats, it was the biggest variety theatre in London at that time. He hired Charell, hoping that he would repeat his Berlin success in London. Charell remained true to his original concept. As in Berlin, he relied on overwhelming the audience with sheer excess. Again, the complete interior of the theatre was turned into a version of the Alpine uplands. The production featured 160 actors, three orchestras, live animals and a real rainstorm resulting in staggering production costs. However, Stoll’s investment paid off: within twenty-four hours the box office reported bookings worth £50,000. The reviewers were suitably impressed. ‘Indeed, London can never before have seen a musical play produced on such a scale’, reported the Daily Telegraph, ‘or beheld such mass movements by crowds perfectly drilled and co-ordinated, and such a succession of quickly moving scenes rich in varied (and often gorgeous) colour.’9 The Morning Post called it the ‘success of the century!’10 In view of the German origin of the production, the partly German cast and the Austrian setting, the Sunday Referee found it important to emphasize the ‘all-British chorus’ and the ‘all-British workmen’ – one of many examples of the complicated relationship between the cosmopolitan and the national.11 The theatre’s readiness to look for inspiration and content abroad could and often did provoke raised eyebrows if not open opposition.

In any case, Charell found himself in great demand. Stoll immediately rehired him to produce a show in 1932, which became Casanova. At the same time, Charell oversaw the production of the Paris adaptation of Im weißen Rössl, L’Auberge du Cheval-Blanc, which ran for four years. An American production followed in 1936 in New York, where Charell had fled from the Nazis. That Charell looked after all these productions personally was new. Up to then, theatre managers used to buy the rights to a play and score, taking care of the production themselves. However, in the case of White Horse Inn, plot and music were less important than Charell’s ground-breaking mise-en-scène. This left theatre managers no alternative other than to hire the director himself and his team. Charell thereby could be said to have pioneered the method by which a play is sold as a complete package as would become common in popular musical theatre later in the twentieth century.

For a German director to work abroad was extremely tempting in the 1930s both to escape the menacing political atmosphere in Berlin and to earn foreign currency. The Great Depression hit the German economy especially hard and led to steeply rising unemployment. For many people, going to the theatre was a luxury they could no longer afford. This again plunged the theatre industry into crisis, and many Berlin theatres closed. Those that remained open were either state-owned or part of one of just three theatre trusts. When the biggest of them, the Rotter Trust, comprising around thirty theatres in Germany, went bankrupt in January 1933, it meant further closures.

There can be little doubt, though, that the Berlin theatre industry would have revived after the end of the economic crisis as it did in other European capitals. However, by that time, Hitler had been appointed chancellor and the Nazis were in power. They ruthlessly exploited the fact that the owners of the Rotter Trust were Jewish. Claiming Jews had destroyed the German theatre, they systematically removed Jewish managers. Increasingly, Jewish artists had to fear for their lives. Many left the country, fleeing to Austria, Czechoslovakia, France and Britain, and from there often to the United States. Among them were Oscar Straus, Jean Gilbert, Hugo Hirsch, Paul Abraham, Robert Stolz, Ralph Benatzky, Erik Charell, Bert Brecht, Kurt Weill, Fritzi Massary, Richard Tauber and many more. Not all who left were Jewish, some, like Brecht, were wanted because they were communists, others, like Marlene Dietrich, simply hated the Nazis. Those who did not get out in time were persecuted or killed, like Fritz Löhner-Beda, who was murdered in Auschwitz in 1942.

The mass exodus of Jewish talent, that had shaped Berlin theatre since the beginning of the nineteenth century, necessarily made it much poorer, but it also meant that non-Jewish writers and composers profited from the situation. Because operettas by Jewish composers were forbidden, they now found it much easier to get their works performed. Paul Lincke, Walter Kollo and Eduard Künneke, who had been sidelined by other composers, all witnessed something of a comeback during the Nazi period. Some new talents emerged. In December 1933 Berlin saw the premiere of Clivia by Nico Dostal, who until then had mainly worked as a conductor and arranger for more successful composers. Clivia was his first operetta and became an instant hit. The operetta was named after its heroine, a famous American actress who has come to the made-up South American republic of Boliguay to star in an American film. The whole project is thrown into jeopardy when the government is toppled by guerrillas and can only be saved if Clivia agrees to marry a Boliguayan gaucho.

Meanwhile back in reality, the German government had been toppled and the Germans had become married to the Nazis. For people who were not Jewish and not interested in politics, everyday life at first did not seem to change that much. Despite their attacks on Weimar culture, the Nazi regime did not replace cosmopolitan operetta theatres with pseudo-Aryan open-air Thingspiele. Clivia did not differ that much from the operettas before 1933, and it did not promote a political message. Apart from a sometimes less, sometimes more overt anti-Semitism this would remain so throughout the Nazi period. The regime saw operetta as a distraction not as a tool of propaganda. But, of course, it purged operetta of any trace of openness, subversiveness and cosmopolitanism. Foreign shows were no longer welcome in Berlin and neither did Berlin shows travel outside of Germany. Much more than World War I, World War II disrupted the network between the major theatrical hubs in Europe and abroad.

After the war, Berlin was divided into two cities, both of which did little to rescue the heritage of Berlin operetta. The nationalization of theatres that had begun in the Weimar Republic continued during the Nazi period until almost all theatres in Germany were in government hands. In both German countries, this development was not reversed. Even after 1945, theatres remained publicly funded and state-controlled, with appointed intendants. The commercial-theatre industry, once making up 90 per cent of Berlin’s theatres, never revived. The publicly funded theatre saw its mission as to provide highbrow, educational fare. Operetta by contrast had been wedded to the commercial theatre from its beginning. The absence of such a commercial sector partly explains why operetta did not return. Offenbach’s and Strauss’s operettas, now elevated into perennial classics, were sometimes picked up by opera houses to improve attendance figures. Berlin operetta, on the other hand, was largely forgotten, the only exception was Lincke’s Frau Luna, a perennial favourite with provincial theatres in the vicinity of Berlin.

With no new operettas coming out, the genre ossified. Compared to the Broadway musicals now performed across Germany, it looked more and more old-fashioned. It can be no surprise, then, that Berlin never regained the position in the world of popular musical theatre it had occupied before 1933. Like the city itself, its theatre became provincial. Im weißen Rössl was the last Berlin operetta to be staged in London, Paris and New York. Henceforth, popular musical theatre history was made in the West End and on Broadway, not on Friedrichstraße or Kurfürstendamm.

The question of the origins and generic characteristics of operetta has always been contentious, but it assumed particularly heated tones in Italy, a country that prided itself on having invented most forms of musical theatre. After all, it is undeniable that the very word ‘operetta’ comes from the Italian ‘opera’. The relationship between operetta and Italian opera – not only buffa but also seria – was central to the critical discourses about Italian music and culture between the 1860s and the 1920s, becoming closely intertwined with the debate about the position of musical theatre between entertainment and art. More broadly, the critical response to operetta in Italy reveals concerns and anxiety on the new role the middle classes were acquiring as taste makers, especially with regard to emerging concepts of social decorum and propriety. Inevitably, discussions of operetta took also strong nationalistic undertones in a country that was struggling to find a unifying national identity and that recognized operetta as a foreign import, one that could contaminate opera or illegitimately undermine its primacy on the Italian stage.

Regardless of its complex origins, operetta as we know it today was in Italy first and foremost an imported foreign genre. Starting in the 1860s, it was the French works of Offenbach, Hervé and Lecocq and later the so-called ‘Viennese’ imports of Suppé, Strauss Jr and Lehár that conquered the Italian stages, at first with little response from Italian composers that could undermine the foreign monopoly on operetta. These years, after all, encompassed not only Verdi’s most resounding triumphs but also the consolidation of a canon that included a number of serious and comic operas by Rossini, Donizetti and Bellini. As Bruno Traversetti remarked, ‘[Italian] melodramma … is the only tradition that is common to the entire Italian social universe during the “bourgeois period”: a model that is so voracious and comprehensive that it leaves almost no emotional residues that can be used with dignity.’1

If for a long time Italian composers refused to acknowledge the increasing success of French and Viennese operettas, critics and audiences were drawn to the popular foreign genre that was attracting unprecedented crowds to theatres all over the country, across large cities and small towns. While some more conservative critics looked at operetta with suspiciousness and from the superior standpoint of the time-honoured Italian operatic tradition, an increasingly voracious audience welcomed operetta as a breath of fresh air. Arguably, the success and widespread popularity of foreign operetta in Italy reached its climax at the turn of the century, particularly with the extraordinary success of La vedova allegra, which premiered in Milan in 1907. The Italian adaptation of Lehár’s Die lustige Witwe took Milan and subsequently the entire peninsula by storm, stirring new interest and encouraging more Italian composers to engage with a genre that was now acquiring higher status and increasing popularity even among critics.

Production and Reception of Operetta in Nineteenth-Century Italy

From the 1860s, French touring companies, such as the much celebrated Grégoire brothers, as well as Italian troupes began to adapt, produce and perform French operettas – in French as well as in Italian – in Italy. That Italian critics found these early imports difficult to define in regard to their generic characteristics and perceived quality is immediately clear if we consider the terminology they used to discuss them. When Lecocq’s opéra bouffe Les cent vierges premiered in Paris in 1872, an Italian critic for the Gazzetta musicale di Milano called it ‘an opera buffa’, whereas when the same work opened at the Teatro Manzoni in Milan in 1874 it was called a ‘vaudeville’. Another extremely successful opéra comique by Lecocq, La fille de Madame Angot, was dismissed as ‘a French buffoonerie’, a ‘parody that came from France … the most French if not the most ungraceful of all’.2 However, when Lecocq’s opéra comique Les prés Saint-Gervais was performed in London in 1874, an Italian critic wrote that this was ‘overall, an operetta that belongs more to the elegant genre of the opéra comique’.3 While the presence of dialogue was clearly a strong defining element, it seems clear also that the perceived quality of the work could contribute to a definition. Only a few selected French imports could aspire, in fact, to be compared to Italian genres. Offenbach’s Madame l’archiduc, for example, is praised by a critic for the Gazzetta musicale di Milano as ‘a jewel’, its music really worthy of an opera buffa.4

Examining the rise of operetta in Italy, Carlotta Sorba argued that ‘Italian versions of French operettas developed immediately both their own more comic side as well as a greater emphasis on word and mime compared to music, thus distancing themselves from the Italian operatic tradition, with which it was particularly difficult to compete’.5 The distinct nature of French operetta in Italy was reflected in the system of production. Venues for spettacoli d’arti varie, variety shows, began to be purpose-built during the 1870s, attracting large crowds of paying audiences, who sought varied and light-hearted forms of entertainment at low prices. The Teatro dal Verme, which would see the Italian premiere of La vedova allegra in 1907, could host also clown and circus acts, acrobatic and equestrian displays and magic shows, and later the French import ‘cabaret’ as well as operetta, opera buffa and ‘main stream’ opera. La Scala, on the other hand, the temple where the increasingly codified operatic canon was consecrated, remained impermeable to the charms of operetta. And the same differentiation of venues according to repertory can be observed in other Italian cities.

The audiences of operetta in Italy during the 1860s and 1870s are often described as rowdy and loud, responding to silly gags with ‘guffaws’. Even a bolt of lightning that hit the stage during one of the performances of La figlia di Madame Angot at the Teatro dal Verme was received with laughter, prompting a critic to comment that ‘the audience, used to the school of the daughter of Madame Angot, does not have respect for anything anymore and started laughing even at lightning. This is definitely the century of parody.’ The same critic seems amused and surprised to learn that at the Teatro dal Verme, ‘the clients’ (not il pubblico but gli avventori, italics in the source!) could not only smoke but also drink beer during the shows. Operetta, after all, was considered pure entertainment and could not aspire to be considered art. Therefore, the audience was encouraged to attend operettas only if ‘they wanted to be amused for a couple of hours’.6

The audience’s misbehaviour was apparently caused by what some critics considered as an extremely lascivious kind of theatre that relied on easy, vulgar and often sexual, innuendos. Again describing Lecocq’s Les cent vierges in Paris in 1872, a critic for the Gazzetta musicale di Milano argues that ‘honest women don’t dare go to the theatre anymore’ since the French librettos of these days had become so obscene that they caused them to blush.7 When Le cento vergini finally arrived in Milan in 1874, another critic confirmed: ‘it was said that it was immoral: let us actually say it is lewd, which is something else. It does not corrupt anything, but at times it can become nauseating.’8 It was not only the lasciviousness of the story but also the apparently nonsensical nature of many operettas that offended the critics’ good taste, as a critic observed about Offenbach’s Le corsaire noir:

This whole pasticcio is too much for one night. Incoherence merrily follows incoherence; inverisimilitude follows inverismilitude; scenes and tableaux follow more scenes and more tableaux without a logical link between them; fantasy and reality, history and fairy tale alternate without any connection between each other and without creating a harmonious whole that would fit the action.

As for the music, if in some cases critics were generally positive about two or three key numbers, usually dances like cancan, csárdás and waltzes, some operettas received harsh reviews, as for example Offenbach’s aforementioned Le corsaire noir in the Gazzetta di Milano in 1872: