15 Intertextuality, sampling, and copyright

Intertextuality, most broadly defined as the relationship between one text and others, is pervasive in multiple forms of popular music, and of all music in general, but is arguably most overtly presented in hip-hop music and culture.1 This chapter will outline a number of analytical approaches to the varied forms of intertextuality in recordings of hip-hop music. Related to this are questions of ownership, copyright, and the ethics of using such material perceived by some to be foundational to the construction of new hip-hop recordings. Though the legal context has changed over time, and differs between countries, I will point to some influential cases in US copyright law which have helped shape the sonic landscape of mainstream hip-hop. As I have written elsewhere,2 hip-hop openly celebrates its connections with the past, creating a vast intertextual network from myriad elements within and outside of hip-hop culture.

Musical borrowing, digital sampling, and signifyin(g)

From its very outset, hip-hop music was founded on the manipulation of pre-existing material. DJs originally borrowed instrumental excerpts from records (known as “breaks” or “breakbeats,” see Chapters 2 and 4) to craft their sets, either looping passages with two copies of the same record or stringing passages together from different records. As digital sampling technology improved and became more affordable in the mid to late 1980s, many of the hip-hop DJ practices were adopted by the hip-hop producer, utilizing the new technologies in the process. Brewster and Broughton argue convincingly that sampling was just a faster, more complex and permanent way of re-creating what the DJs had been doing all along.3

With the technology of the digital age, using pre-existing material has become much easier with technology enabling composers to take all elements of a recorded performance. But even though the practice of digital sampling falls into a tradition of twentieth-century collage and an even longer history of African American and European artistic practices, the act of taking material from a recording for the financial gain of another became a legal and ethical issue. A number of high profile copyright lawsuits in the late 1980s and early 1990s set the precedent for regulating such “collage style” sampling made famous by the Bomb Squad (Public Enemy, Ice Cube) and the Dust Brothers (Beastie Boys).

Russell Potter, in addition to describing sampling as political and as postmodern, discusses the practice as a form of Signifyin(g), a concept theorized by Henry Louis Gates Jr. in African American literary studies, and adapted to Black musics by Samuel A. Floyd Jr. To quote Potter:

Simply put, Signifyin(g) is repetition with a difference; the same and yet not the same. When, in a jazz riff, a horn player substitutes one arpeggio for a harmony note, or “cuts up” a well-known solo by altering its tempo, phrasing, or accents, s/he is Signifyin(g) on all previous versions. When a blues singer, like Blind Willie McTell, “borrows” a cut known as the “Wabash Rag” and re-cuts it as the “Georgia Rag,” he is Signifyin(g) on a rival’s recording.4

Like ragtime, swing, hard bop, bebop, cool, reggae, dub, and hip-hop, these musical forms were Signifyin(g) what came before them. Furthermore, musical texts Signify upon one another, troping and revising particular musical ideas. These musical “conversations” can therefore occur between the present and the past, or synchronically within a particular genre.

Signifyin(g), as Gates writes, is derived from myths of the African god Esu-Elegbara, later manifested as the trickster figure of the Signifying Monkey in African American oral tradition.5 Gates writes, “For the Signifying Monkey exists as the great trope of Afro-American discourse, and the trope of tropes, his language of Signifyin(g), is his verbal sign in the Afro-American tradition.”6 To Signify is to foreground the signifier, to give it importance for its own sake. The language of the monkey is playful yet intelligent, and can be found in the West African poet/musician griots, in hipster talk and radio DJs of the 1950s, comedians such as Redd Foxx, 1970s Blaxploitation characters such as Dolemite, and in countless rap lyrics. It should be stated that in addition to Signifying as masterful revision and repetition of tropes, it also includes double-voiced or multi-voiced utterances which complicate any simple semiotic interpretation.

The sampling of classic breakbeats, to use but one example, is certainly a foundational instance of musical Signifyin(g) in hip-hop, musically troping on and responding to what has come before.7 Linked with the concept of Signifyin(g) is Bakhtin’s concept of dialogism, as well as that of the multi-vocality of texts, two aspects also related to hip-hop’s intertextuality.8 “Answer songs” (which of course predate hip-hop) such as “Roxanne’s Revenge” by Roxanne Shante (in answer to UTFO’s “Roxanne, Roxanne”) would also fit in terms of intertextual relationships. Signifyin(g), dialogism, and intertextuality all form important academic frameworks in which to understand hip-hop’s borrowing practices.

Hip-hop’s intertextuality arguably fits within a long tradition in the Western music canon as well. Major forms of polyphony up to 1300 – organum, discant, and motet – were all based on existing melodies, usually chant. Masses in the sixteenth century could be divided in terms of cantus firmus mass (or tenor mass), cantus firmus/imitation mass, paraphrase mass, or parody mass. These earlier cultures show that a notion of musical creativity in terms of pure originality was anachronistic for that time period. Compositional practice involved reworking pre-existing material in an unconcealed manner, particularly akin to sample-based hip-hop, in contrast to nineteenth-century Romantic ideologies where composers often denied their precursors in an attempt to appear purely original. This is not to mention the works of twentieth-century composers like Charles Ives and Luciano Berio who also included a high level of pre-existing material in their works. J. Peter Burkholder, in addition to providing a thousand-year history of musical borrowing, has also engaged in a typology of borrowing which most directly relates to his extensive research on Charles Ives, but could be expanded and adapted to a number of forms of repertoire.9

In terms of sampling more specifically, it is worth considering what sets digital sampling apart from other forms of borrowing. Chris Cutler notes that samples are essentially “vertical slices” of sound which are then converted into binary information which is then stored as information for the eventual reconstruction of the sound.10 In one of the most engaging studies of digital sampling to date, Katz also explains that the sampling rate is 44,100 Hz, which means that each second of sound is cut into 44,100 slices, and states, “Although sampling, particularly when done well, is far from a simple matter, the possibilities it offers are nearly limitless.”11 And as Tricia Rose wrote in Black Noise, hip-hop culture is at the intersection of African and African American artistic cultures and traditions and newer technologies like digital sampling which allow practitioners to extend older traditions in new and varied ways.12

Sampling is only one of the ways that hip-hop can borrow and reference pre-existing material: sampling as a technique is, in addition to reperforming past music (by way of a DJ or live band), referencing other lyrics, matching the style of another rapper’s flow, and quoting sounds and dialogue in the music, and other intertextual techniques. In terms of the digital, non-digital divide (which does often overlap), one can make the useful distinction between “autosonic quotation” and “allosonic quotation” from Serge Lacasse. “Autosonic quotation” is quotation of a recording by digitally sampling it, as opposed to “allosonic quotation,” which quotes the previous material by way of re-recording or performing the quotation in live performance.13 To take jazz as an example, the distinction would be between digitally sampling a Charlie Parker solo phrase (or “lick”) for Gang Starr’s “Jazz Thing” (1990) (autosonic) versus a recording of a jazz musician in live performance quoting a similar phrase (allosonic). Additionally, it is worth analyzing the length of sample used: is it a long (e.g. four-measure) loop, or a smaller riff? Or a mix of both (such as Kanye West’s “Champion” and his production on Talib Kweli’s “In the Mood”)? Looking at sequencing as well as sampling can help create an analogue to Middleton’s distinction between “discursive” (longer-phrase) and “musematic” (riff-based) repetition which would be an additional distinction in the analysis of autosonic quotation in the “basic beat”14 of a given rap song.

Another important distinction that can be made with borrowing in hip-hop is the difference between “textually signaled” and “textually unsignaled” forms of intertextuality. While hip-hop music is often highly intertextual, this is not meant to imply that all hip-hop musical texts draw attention to their borrowing equally. Film scholar Richard Dyer, writing on pastiche, notes that as an imitative artistic form, it is “textually signaled” as such; in other words, the text itself draws attention to the fact that it contains imitative material.15 In the case of pastiche and film adaptation, and in forms like parody and homage, recognizing that these works are referring to something that precedes them is crucial to their identity. Hip-hop songs can textually signal their borrowing overtly or not do so, and both approaches can be manifested in a number of ways.

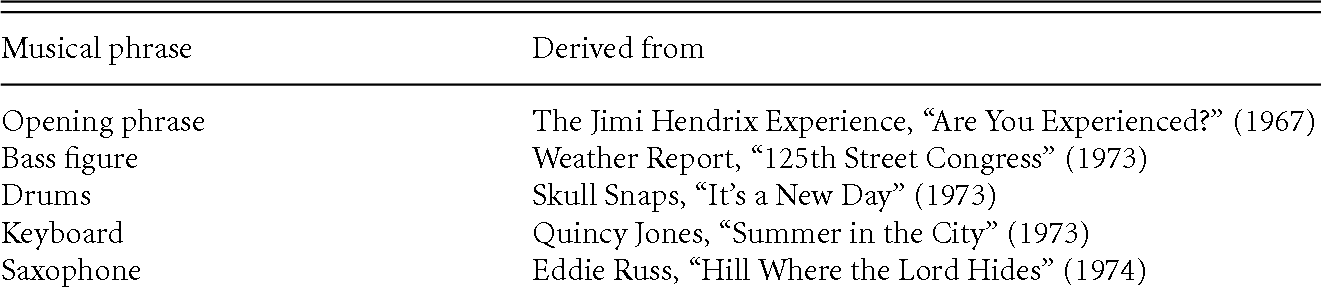

Take, for example, two recorded examples of hip-hop from roughly the same era and geographical location (1992–1993, Los Angeles): the Pharcyde’s “Passin’ me By” (from Bizarre Ride to the Pharcyde) and Snoop Doggy Dogg’s “Who am I (What’s my Name?)” (from Doggystyle). Both use source material from elsewhere (see Table 15.1), but the vinyl pop and hiss audible in the Pharcyde example draws attention to the fact that the material comes from an earlier source. It is also a trope we might call “vinyl aesthetics”: a signifier of hip-hop authenticity associated with the sounds of vinyl (popping, hiss, and scratching to name a few). To invoke the terminology from Lacasse which is useful in the study of recorded music, the Pharcyde example is autosonic, in that it comes from a digital sample, and the Dr. Dre example is allosonic, in that its borrowed material has been re-recorded.

Table 15.1 Samples and borrowed material from the Pharcyde’s “Passin’ me By” and Snoop Doggy Dogg’s “Who am I (What’s my Name?).”

“Passin’ Me By” (1992) autosonic quotations, textually signaled

“Who am I (What’s my Name?)” (1993) allosonic quotations, not textually signaled

Furthermore, the hiss of vinyl heard faintly in the introduction of “Passin’ me By” textually signals that some of the song has its roots elsewhere, that elements have been borrowed, and most likely sampled. In contrast, “Who am I?” contains many elements derived from earlier songs but was re-recorded in a studio (apart from its two-measure introduction), and does not contain any vinyl popping or hiss characteristic of sample-based hip-hop songs. In other words, “Who am I?”’s intertexuality is not textually signaled. Its sources of material are not obvious in themselves, and to a young listener unknowledgeable of 1970s soul and funk, it can sound strikingly “original.”16

Other instances of “textually signaled” borrowing in hip-hop could also include references and citations to earlier lyrics (50 Cent’s “Snoop said this in ’94: ‘We Don’t Love them Hoes’” in “Patiently Waiting”) or using short snippets of dialogue that originate elsewhere. In the beat, this would include vinyl hiss and popping, scratching, looped beats, “chopped up” beats, as producers and rappers may use a sample as an opening phrase, and proceed to chop the phrase for its basic beat,17 using breakbeats that fall firmly within the breakbeat canon, heavy collages of sound (The Bomb Squad, DJ Shadow), and sped up samples (such as Kanye West’s “Through the Wire” (2003)). In addition, the sampling could be textually signaled if the borrowed fragment “doesn’t quite fit” with the rest of the material; for example, being slightly out of tune with other elements or if the duration of the sample does not fit any “regular” pattern (i.e. four- or eight-measure pattern).

These distinctions are important to make, in light of the fact that on an abstract level, “everything is borrowed,” a phrase that I myself borrow from an album title of the UK hip-hop group the Streets. But what is compelling for the study of intertextuality is how exactly particular communities incorporate borrowing, celebrate it, conceal it, and discuss it.

Sampling and copyright

Copyright emerged as a result of the invention of the printing press, and most point to the Statute of Anne in 1710 in England as the first legislation which protected authors for a certain amount of time from unauthorized use or sale of their work. Since then, countries have developed and modified legislation regarding authorship and ownership of intellectual property. One of the issues with the study of copyright cases is that many are settled out of court, but even when we do not have such data, such high-profile cases have had ramification for artists and the music industry. As McLeod and Dicola write, “Licensing negotiations always take place in the shadow of copyright law’s provisions – and the ways that courts have interpreted those provisions in particular cases.”18

In order to sample a sound, rights need to be cleared and a license needs to be given for use, both for the recording rights and for publishing. It is important, here, to draw the distinction between publishing fees and master recording (or mechanical) fees. When Dr. Dre re-records songs, he only has to pay the publishing fees and not the mechanical fees in addition to the publishing, as would be the case if he digitally sampled the sounds. Kembrew McLeod writes, “The publishing fee, which is paid to the company or individual owning a particular song, often consists of a flexible and somewhat arbitrary formula that calculates a statutory royalty rate set by Congress.”19 Those who do not pay a fee can be subject to lawsuits from those who own the rights. Sampling artists can argue fair use, or that they used an excerpt so small that it was unrecognizable or not integral to the original songs, but this is not necessarily a failsafe argument. The court cases that deal with sampling are battlefields that set important precedents and trends in creative practices. As McLeod and DiCola write:

In particular, lawsuits play a role in determining the way and the degree to which musicians can use prior works by other musicians. When a copyright owner brings a successful claim for infringement, the range of existing music to which musicians have unfettered access can shrink. On the other hand, when a musician who has sampled without permission mounts a successful defence to copyright infringement, access might be understood to expand.20

One of the first cases to receive media attention was when the Turtles sued De La Soul in 1989, which was settled out of court, but was for unauthorized use of “You Showed Me” for “Transmitting Live from Mars.” The lawsuit made record companies hesitant to support such heavily sample-based albums as3 Feet High and Rising. Two years later, Grand Upright Music, Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records, Inc. set an important precedent. Biz Markie had used material from Gilbert O’Sullivan’s “Alone Again (Naturally)” for his song “Alone Again.” Biz Markie lost the case. The judge considered any unauthorized sampling an act of theft, and all samples had to be cleared by the copyright owner (and the title of Markie’s next album would be All Samples Cleared). Other cases, such as Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music (1994) deemed 2 Live Crew’s use of “Oh, Pretty Woman” by Roy Orbison a parody and held that the sales of the parody would not hurt the sales of the Roy Orbison recording. Uses of parody and critique in the USA can fall under “fair use” as long as the case is made that it is transformative and does not hurt the sale of the original product.21

Bridgeport Music, Inc., founded in 1969, is a company of one man who buys the rights to various music catalogues (most famously that of George Clinton) and sues those who use the material without license (Bridgeport had five hundred lawsuits in 2001 alone). An extremely important case involving the company was Bridgeport Music Inc. v. Dimension Films (2005), which claimed that N.W.A.’s “100 miles and Running” used a three-note chord from Funkadelic’s “Get off Your Ass and Jam,” albeit with the pitch lowered and looped five times. In previous cases this may have been considered transformative and so minimal (de minimis) as to be not considered infringement. However, Bridgeport Music did win the case, and it set a precedent that any sampled sound needs to be subject to clearance.22 Bridgeport also successfully sued Bad Boy Records in 2006 for use of an Ohio Players’ track on Notorious B.I.G.’sReady to Die. This halted album sales until after the settlement (reported to be $4 million).23 Sometimes it is too expensive to clear a sample, such as when Public Enemy wanted to use “Tomorrow Never Knows” by the Beatles in 2002 but the song had to be taken off the album. And in 2004, EMI sent a cease and desist letter to DJ Danger Mouse for the Grey Album (which mixes Jay-Z’s Black Album with the Beatles’ White Album).24 The legal battles will continue in the foreseeable future, though both sides of the debate are getting their arguments across in various arenas (websites, articles, and other media). It is safe to say that copyright legislation over sampling has had a measurable effect on the sounds of hip-hop, and that some of the intertextual spirit of the genre is now tempered by the legal requirements of clearing samples.

Case study: Xzibit/Wendy Carlos/J. S. Bach

To provide a more substantial example in the close reading of a recorded hip-hop text, I will now turn to a specific instance of sampling from the classical music canon. I focus on the elements of the “beat” or basic beat, rather than lyrical content, in depth and choose to use them as an example of how the concepts outlined earlier in this chapter apply to a piece of recorded hip-hop. I could have chosen pieces that sample other repertoire or other genres, but there may be some wider implications in the use of pieces which have had relatively long lives (and afterlives) in the public sphere.

“Symphony in X Major” (2002) is a single from the rapper Xzibit on his fourth album Man v. Machine. The song is produced by Bay Area-based Rick Rock (active since 1996) and features a verse by accomplished producer Dr. Dre (Andre Young). Hip-hop music production since the mid 1990s is too varied to define comprehensively, but it often includes a mix of technology such as samplers, sequencers, synthesizers, drum machines, and more traditionally “live” instruments. Xzibit, Alvin Nathaniel Joiner (b. 1974), has been a professional rapper since the mid 1990s, often collaborating with other West Coast rap stars, including a featured role as guest on Dr. Dre’sChronic 2001 (1999). The presence of Dr. Dre on “Symphony in X Major” is not uncommon for rap at this time, as there were often numerous guest artists and multiple producers on a single album.

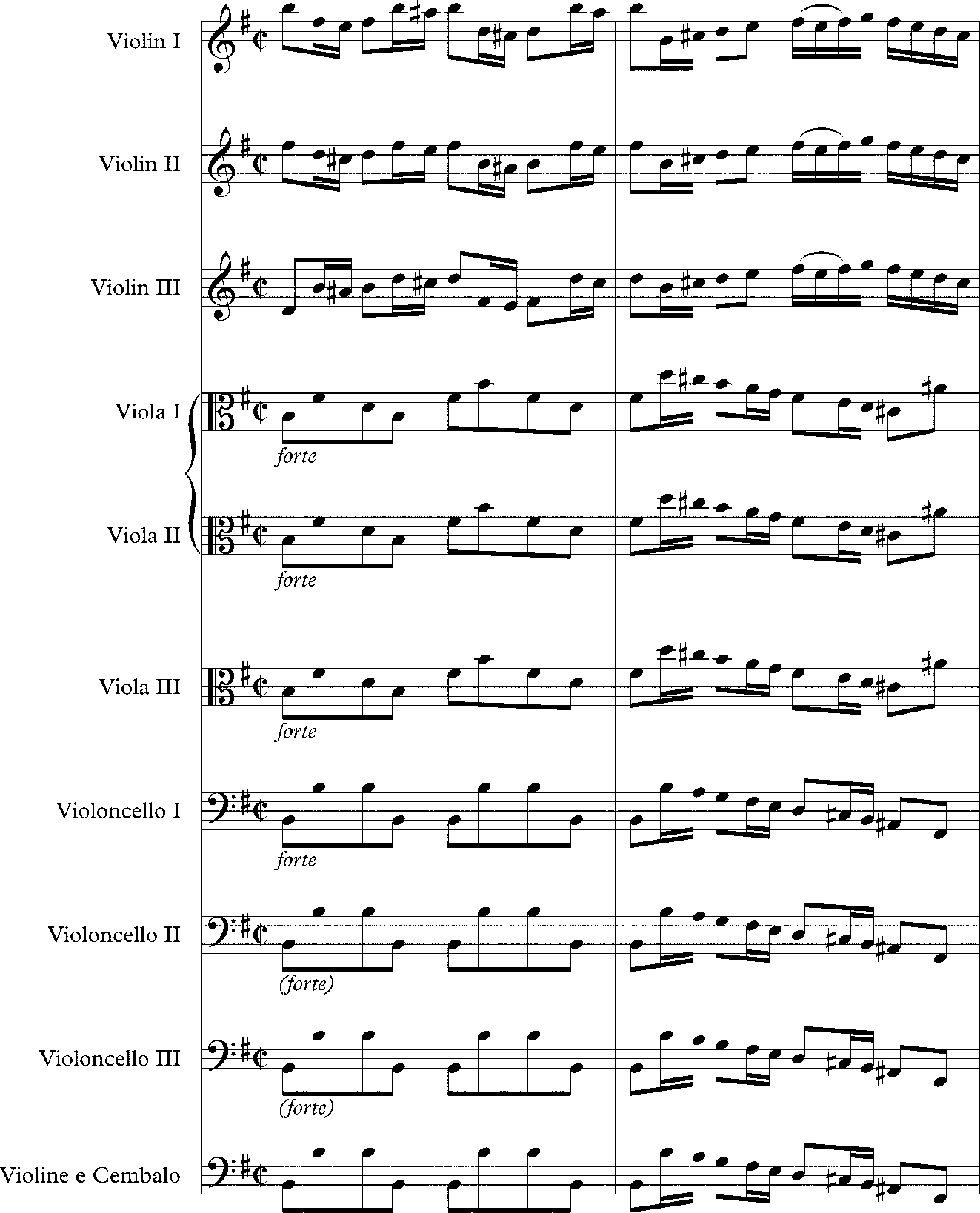

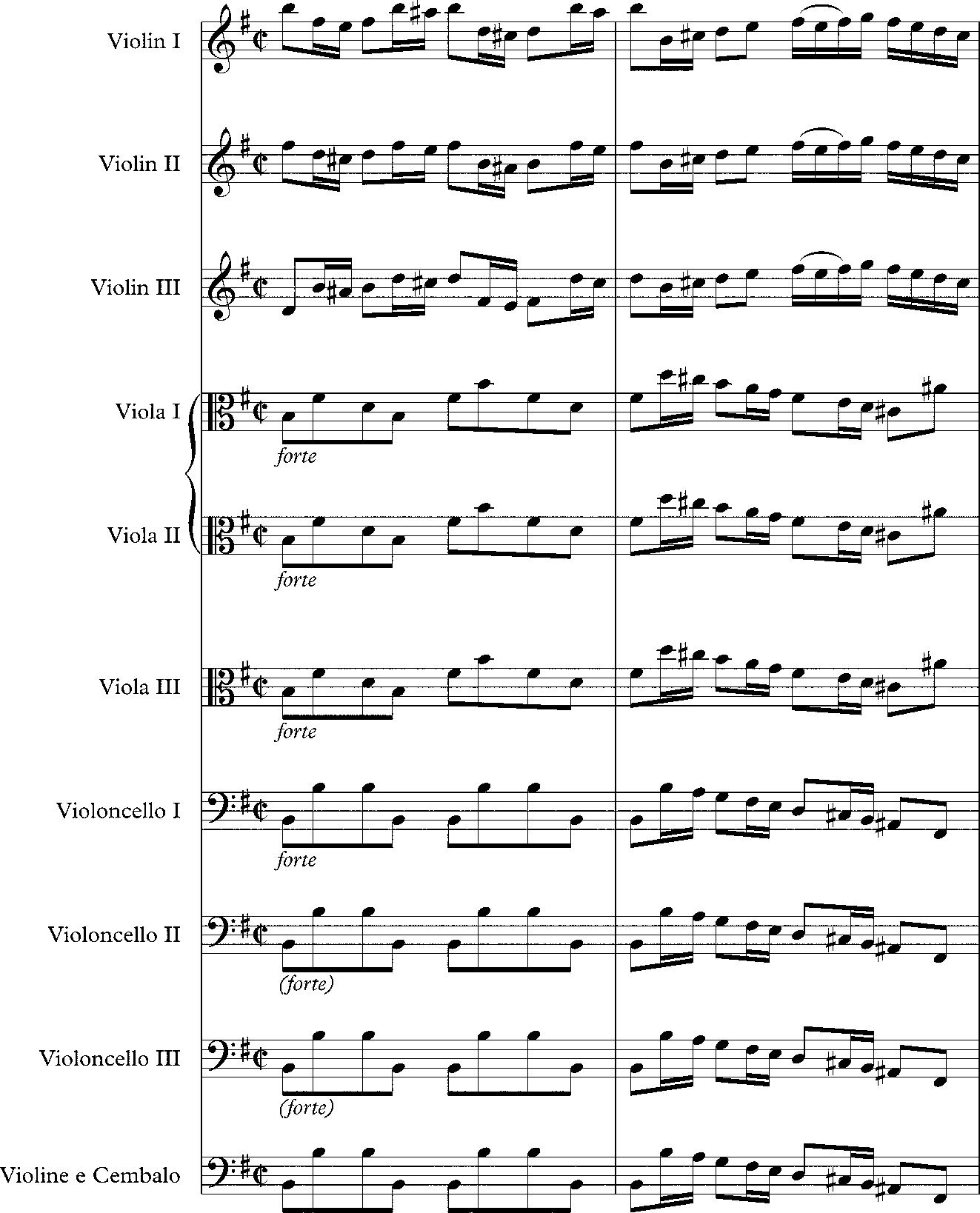

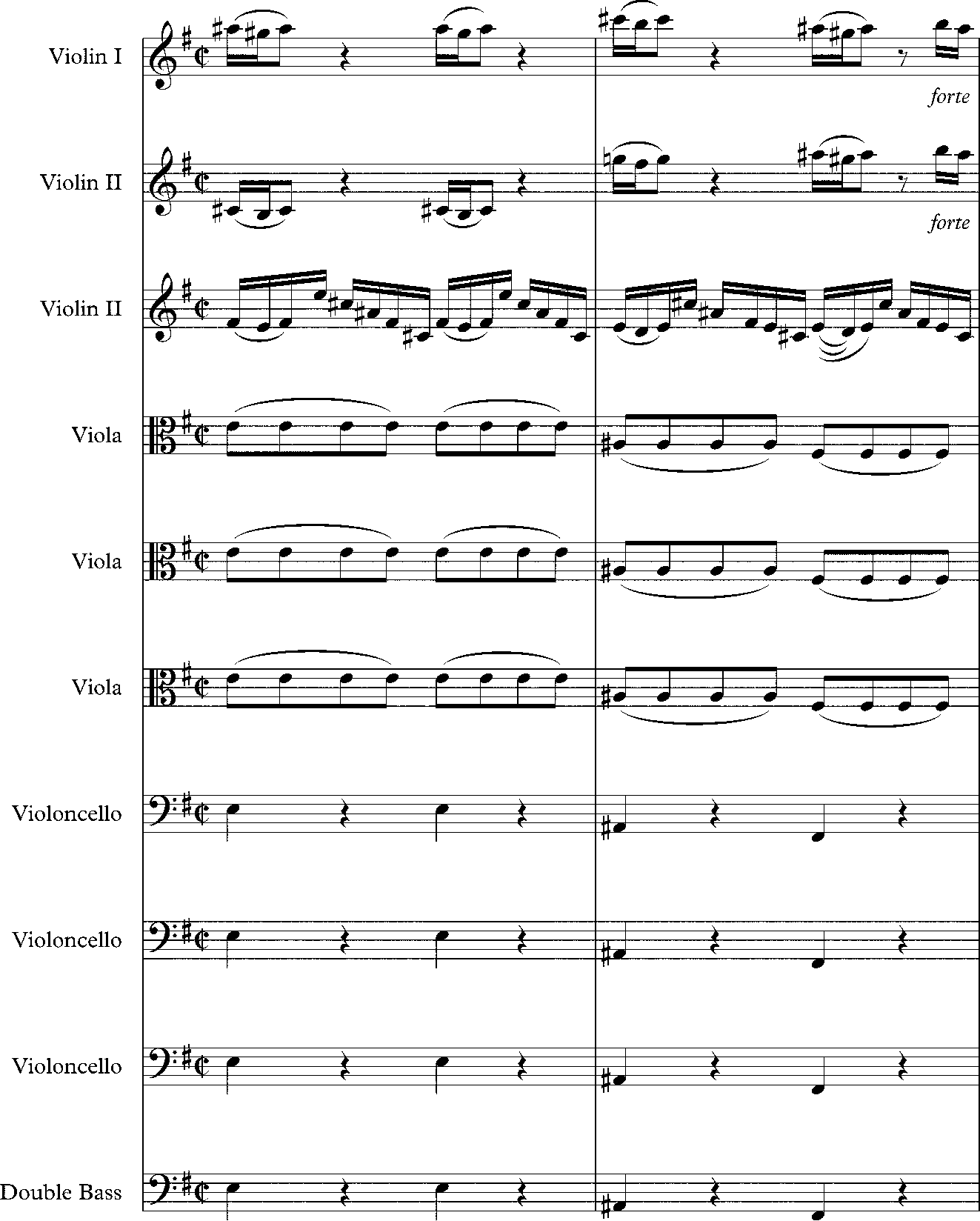

Unlike the Dr. Dre early-1990s production mentioned earlier (e.g. “Who am I?”), “Symphony in X Major” relies more heavily on overt autosonic quotation, and textually signals the source of the sample. The samples are the most prominent aspect of the basic beat, although there is the presence of simple and unobtrusive programmed rhythmic percussion with emphasis on beats one (kick drum) and three (clap/snare). The percussive additions are minimal, but transform the sample into a track characteristic of the hip-hop genre. The song consists of two samples both taken from the same source: Wendy Carlos’sSwitched on Bach (1968) version of Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 (first movement). The excerpt is from the middle section of the movement, when the theme transitions into the relative minor key. It may be significant that the song uses the shift to the minor key of the movement, which becomes useful in reinforcing the menacing tone of the hip-hop track. I will call the two pieces of sampled material sample A (mm. 70–71 of Brandenburg Concerto) and sample B (mm. 68–69 of Brandenburg Concerto)25 – see Examples 15.1 and 15.2.

Example 15.1 Sample A (mm. 70–71) Brandenburg Concerto No. 3, 1st movement.

Example 15.2 Sample B (mm. 68–69) Brandenburg Concerto No. 3, 1st movement.

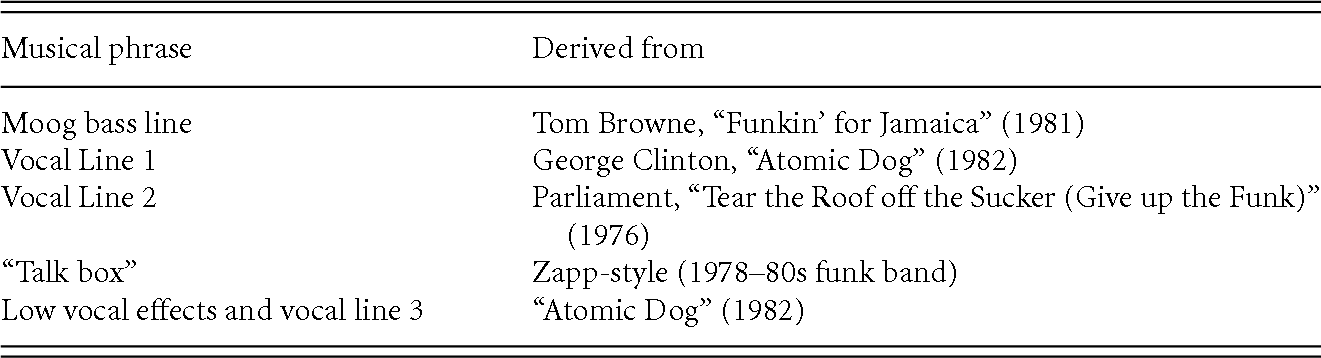

“Symphony in X Major” follows a contrasting verse–chorus structure in that the harmonic material of the chorus differs from that of the verse (Table 15.2). The chorus consists of the two-measure sample A repeated once to create a four-measure phrase in total. The chorus includes both male and female voices singing pseudo-operatically over the primary “violin” melody of the sample. The verse consists of the two-measure sample B repeated eight times. The verse with rapped material followed by the chorus with sung material reflects a transition in hip-hop song form from free rhyming verse over a repeated riff (“Rapper’s Delight” [1979]) to rap songs with sung choruses (in part, ushered in by Dr. Dre’s G-Funk era (Reference Gilroy1992–Reference Gooch, Stout and Buddenbaum1996), e.g. “Let me Ride” (1992) and “Nuthin but a ‘G’ Thang” (1992)).

Table 15.2 “Symphony in X Major” form (section/function, number of bars and sample used)

The contrasting verse–chorus form is common for hip-hop at the time, as is the musematic (or riff-based) repetition in the verse (sample B) with longer (discursive) phrases on the chorus (sample A). To use Dyer’s distinction, there are two primary elements which suggest that the recorded text signals the autosonic quotations rather than unsignaling them. The first eight measures of the song consist of two iterations of sample A, and we can hear the rupture between measure two and three as the sample begins to loop again. There is no attempt to cover this up with flow in the first instance. Furthermore, verse four is an instrumental which is the same loop of sample B found in the previous verses and transition section (repeated in the instrumental verse four times). The exposure of the sample, as seen in the form of the track, demonstrates that it celebrates its sample origins. In a general sense, we can analyze this particular hip-hop track as characteristic of its era: sample-based (sampling the same track rather than multiple tracks), with a level of synthesized reinforcement (in this instance, drum sounds), with a contrasting verse–chorus form, autosonic quotations in verse and chorus, allosonic quotations of the Bach melody in the form of the sung chorus, and overall, the basic beat textually signaling where its primary source comes from. By virtue of the musical material sampled, the verse includes musematic repetition as compared to the chorus material of sample A, which suggests more discursive repetition. While there is a high degree of flow located in the rap track, the fact that both sample A and sample B have instrumental sections without flow or singing demonstrate that these samples are placed prominently in order to be heard.

It is at this point that we might be inclined to draw multi-layered meaning from the use of this sample. Do we wish to draw meaning from its generic associations, a genre synecdoche of “classical music” (broadly defined), or perhaps even misread as opera, given the “operatic” voices on the chorus and transition section? Do we go further and give meaning to the prominence of its composer (J. S. Bach), his afterlife and reception as an important cultural figure and the multiple shades of his personal portrayal over the centuries (the divine genius, the hard-working craftsman, the subject of the refined tastes of a serial killer, or the Romantic nineteenth-century choral “reboots”/revivals of Bach’s music)? There are a number of instances where this would be appropriate, in particular, when films utilize his music and character in quite overt ways.26 But in this particular instance, one might hesitate before placing too much emphasis on the direct Bach link, in the same way that Robert Fink attaches less meaning to Pachelbel in the afterlife of Pachelbel’s “Canon in D.”27 Features of classical music become a trope in this particular instance, to cite Leydon’s use of Ratner to discuss sampling. In other words, classical music becomes a stylistic topic in the potential polystylism that hip-hop tracks often express.28

But we also need to acknowledge the “second degree” nature of the borrowing, in that the producer is not simply sampling J. S. Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 generally, but is sampling from a specific famous recorded performance of the piece, that of Wendy/Walter CarlosSwitched on Bach.29 In considering the synthesizer timbres, the Moog synthesizer of Carlos is fused with the contemporary (c. 2002) trend of heavily synthesized hip-hop beats (Eminem’s production on 50 Cent’s “Patiently Waiting” from 2003, for example). In this way, the sample may be more aligned to Schloss’s line of argument for sampling artists’ motivations, that producers sample because the material is beautiful, rather than sampling more specific political and resistant material (as Russell Potter argues, for example). Thus, it is the convergence between vinyl “crate digging” which in this case found a late-1960s album which resembles certain 00s synthesized timbres (Carlos arguably a precursor to a hip-hop based approach to reworking previous materials). Carlos, like many hip-hop producers, was Signifyin(g) on earlier material in a tradition of revision (although tellingly, the score is preserved for Switched on Bach, albeit “re-orchestrated”) – but the use of previous material in the context is an issue of degree rather than quality. Past becomes present which then adds to the trend of producing synthesized hip-hop beats, and perhaps becomes a stylistic topic in itself: representative of mid-00s synthesizer-heavy hip-hop of Interscope/Aftermath, Shady Records, and G-Unit record labels. Wendy Carlos then becomes part of a tradition and genre culture, perhaps more so than J. S. Bach becomes a part of hip-hop culture in this instance. Such is the flexibility of musical signifiers, as they are so heavily dependent on their social contexts.

As Schloss states in Making Beats, too much emphasis has been placed on political readings of sampling, which may be linked to a disproportionate amount of emphasis placed on the quasi-academic location of specific sample sources. This is a feature of “hip-hop heads” or enthusiasts in production and fan communities. But I think we also need to allow for these wider significations. For example, sometimes generic signifiers (those of “jazz,” or “classical,” or synthesized versions of classical) become more important than the actual identity of the sample. If it “sounds jazzy,” rather than originating from an authentic jazz source, then this should be investigated rather than dismissed as an example of how musical structures travel in various cultural realms.30 This has been occurring for more than a century with the idiom of Hollywood film music and its Romantic precursors. For example, does the autosonic use of the “Rex Tremendae” in Mozart’sRequiem for Missy Elliott’s “Who You Gonna Call?” suggest Mozart or the wider “gothic choral aesthetic” found in film music (inspired by Orff’sCarmina Burana and the requiems of Mozart and Verdi)?31 This is dependent on the specific interpretive community, but it does reinforce Leydon’s notion that we are moving toward a focus on sampling “stylistic topics” rather than detailed information from specific examples. In the case of Xzibit, sampling something that, albeit synthesized, still sounds “classical” has a range of meanings which means that while we might be in a “post-canonic era” for classical music, as Fink argues,32 we are nowhere near a post-genre era for either interpretive communities of music or historical musicology as a discipline.

In studies of borrowing, there is always the question of whether to favor compositional process or cultural reception, or, to invoke Nattiez, to place emphasis on the poietic dimension or the esthesic.33 In other words, if we do not hear Bach in “Symphony in X Major” is it still a worthy topic for the study of quotation and musical borrowing? Or on the compositional/poietic side, if the producer did not intend to allude to Bach or Carlos, does it still tell us anything? And if the reception is important, whose reception is it? Is it simply the private reflections of an idiosyncratic white middle-class academic risking the danger of implicitly making spurious claims that these references can generally be heard by “all”?

The answer lies within the imagined community of hip-hop. Most crucially, as I have written elsewhere, this imagined community is also an “interpretive community,” to make reference to Stanley Fish and reader-response theory.34 In any given reference in a rap song, some listeners will understand the reference, and some will not, to varying degrees. This is not to suggest there are one or more fixed meanings, nor a dialectic between “past” and “present,” or necessarily between a hip-hop song and its “source” sample, but multiple imagined “sources,” based on the previous knowledge of specific songs, artists, or genres. It is the reading and misreading of these sources as reflected by constantly shifting and negotiating interpretations within hip-hop’s imagined communities that form its foundations. These hip-hop interpretive communities bring their experiences to the understanding of hip-hop texts, shaping and inflecting that text through the interaction involved in the listening and interpreting experience.

Despite variations inevitable with a group’s interpretation of any given utterance, I would argue that there exists an audience expectation that hip-hop is a vast intertextual network that helps to form and inform the generic contract between audiences and hip-hop groups and artists. And in many cases, hip-hop practitioners overtly celebrate their peers, ancestors, and musical pasts, though reasons why this is so may diverge, and how references and sources are textually signaled (or not) varies on an imaginary spectrum that roughly corresponds to a timeline of traditions and technical innovations. Whereas certain rock or “new music”/contemporary classical ideologies that borrow from Romantic notions of musical genius attempt to demonstrate an illusionary originality, hip-hop takes pride in appropriating and celebrating other sounds and ideas. It is reflective of a long lineage of African American and pre-Romantic Western music-making which has embraced the collective in multifarious ways.

Discography

Notes

1 More specifically, citing Genette, intertextuality is the “relationship of copresence between two texts or among several texts.” Gérard Genette, cited in , “Intertextuality and Hypertextuality in Recorded Popular Music,” in (ed.), The Musical Work: Reality or Invention? (University of Liverpool Press, 2000), p. 36.

2 See , Rhymin’ and Stealin’: Musical Borrowing in Hip-Hop (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013).

3 and , Last Night a DJ Saved my Life: The History of the Disc Jockey (London: Headline Publishing, 2007), p. 267.

4 , Spectacular Vernaculars: Hip-Hop and the Politics of Postmodernism (State University of New York Press, 1995), p. 27.

5 , The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), pp. 55–56. See also Potter, Spectacular Vernaculars, p. 83.

6 Gates, Signifying Monkey, p. 21. For Signifyin(g) in jazz contexts, see , Quotation and Cultural Meaning in Twentieth-century Music (Cambridge University Press, 2003), Chapter 2, “Black and White: Quotations in Duke Ellington’s ‘Black and Tan Fantasy,’” pp. 47–68; , “Doubleness and Jazz Improvisation: Irony, Parody, and Ethnomusicology,” Critical Inquiry20/2 (1994): 283–313; , “Cultural Dialogics and Jazz: A White Historian Signifies,” Black Music Research Journal22 (2002): 71–102. David Brackett uses the concept in his analysis of James Brown’s “Superbad”; see , Interpreting Popular Music (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2000).

7 For more on dialogism, Signifyin(g), and intertextuality, see , Intertextuality (New York: Routledge, 2000); and Mikhail Bakhtin, Discourse in the Novel, in (ed.), The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays (Austin, TX: University of Texas, 1982), pp. 259–422.

8 , “‘Most of my Heroes don’t Appear on no Stamps’: The Dialogics of Rap Music,” Black Music Research Journal11/2 (1991): 193–216.

9 , “Borrowing,” in Laura Macy (ed.), Grove Music Online(Oxford University Press). Available at www.oxfordmusiconline.com/ (accessed June 1, 2014); see also , “The Uses of Existing Music: Musical Borrowing as a Field,” Notes50/3 (1994): 851–870.

10 , “Plunderphonia,” in and (eds.), Audio Culture (London: Continuum, 2004), p. 149.

11 , Capturing Sound: How Technology Has Changed Music (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2004), p. 139.

12 , Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2004), p. 64.

13 Lacasse, “Intertextuality,” pp. 35–58.

14 , Studying Popular Music (Open University Press, 1990), 269–284. For more on the “basic beat,” see Williams, Rhymin’ and Stealin’, p. 2.

15 Williams, Rhymin’ and Stealin’, pp. 7–10.

16 For more on Dr. Dre’s compositional process in his early 1990s productions, see Williams, Rhymin’ and Stealin’, pp. 82–88.

17 Examples would include Kanye West’s production on his own “Champion” (2007) and on Talib Kweli’s “In the Mood” (2007).

18 and , Creative License: The Law and Culture of Digital Sampling (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), p. 128.

19 , Owning Culture: Authorship, Ownership, and Intellectual Property Law (New York: Peter Lang, 2001), p. 91. See also Schloss, Making Beats, p. 175.

20 McLeod and DiCola, Creative License, pp. 128–129.

21 For more on “fair use” in the US legal context, see the Stanford Law School Fair Use Project. Available at http://cyberlaw.stanford.edu/focus-areas/copyright-and-fair-use (accessed May 19, 2014).

22 McLeod and DiCola, Creative License, pp. 144–147.

23 , “Uncleared Sample Halts Sale of Seminal Album,” Copycense, March 20, 2006. Available at http://copycense.com/2006/03/20/uncleared_sampl/ (accessed May 19, 2014).

24 McLeod and DiCola, Creative License, pp. 176–182.

25 Although sample A occurs chronologically after sample B in the Brandenburg, sample A is the first sample we hear in “Symphony in X Major,” in the introduction to the song.

26 For example, see , “Bach and Cigarettes: Imagining the Everyday in Jim Jarmusch’s Int. Trailer. Night,” Twentieth-century Music7/2 (2010): pp. 219–243; and , “Dr. Lecter’s Taste for ‘Goldberg’, or: The Horror of Bach in the Hannibal Franchise,” Journal of the Royal Musical Association137/1 (2012): 107–134.

27 , “Prisoners of Pachelbel: An Essay in Post-canonic Musicology,” Hamburg Jahrbuch (2010). Available at http://ucla.academia.edu/RobertFink/Papers/583880/Prisoners_of_Pachelbel (accessed September 23, 2012).

28 Leydon argues that the era of sampling has now shifted from explicit sampling toward multiple stylistic allusions, and that sampled sounds have become yet another topic in this range of topoi. , “Recombinant Style Topics: The Past and Future of Sampling,” in and (eds.), Sounding out Pop: Analytical Essays in Popular Music (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010), pp. 193–213. I would argue, however, that stylistic allusion has been an important feature since the beginning of hip-hop (styles including funk, disco and rock music to name a few), and that we can have a degree of explicit quotation concurrently with its function as stylistic topic.

29 Cenciarelli coins the term “second degree” borrowings within the Bach context; see , “‘What Never Was Has Ended’: Bach, Bergman and the Beatles in Christopher Munch’s The Hours and Times,” Music & Letters94/1 (2013): 119–137.

30 Justin Williams, Rhymin’ and Stealin’, pp. 47–72.

31 , “Claiming Amadeus: Classical Feedback in American Media,” American Music20/1 (2002): 102–119.

32 , “Elvis Everywhere: Musicology and Popular Music Studies at the Twilight of the Canon,” American Music16/2 (1998): 135–179.

33 , Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music, trans. (Princeton University Press, 1990), pp. 11–15.

34 , Is There a text in this class? The Authority of Interpretive Communities (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980), p. 14.