Introduction

Spinal anaesthesia, epidural anaesthesia and lumbar puncture are simple, high utility and generally well tolerated techniques used for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. However, there are several well-known side effects of these procedures. Hearing loss after these procedures has been reported in several articles including unilateral or bilateral, mild or profound, and temporary or permanent hearing loss.Reference Erol, Topal, Arbag, Kilicaslan, Reisli and Otelcioglu1–Reference Michel and Brusis3 The proposed mechanism for hearing loss following these procedures is a leakage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which leads to decreased perilymphatic pressure within the cochlea.Reference Day and Shutt4 In this study, we present two cases of permanent sensorineural hearing loss following spinal anaesthesia in young patients and review the currently available literature. The presentation, management and probable pathophysiological mechanisms of sensorineural hearing loss after lumbar puncture, spinal anaesthesia or epidural anaesthesia are also discussed. Additionally, we discuss the risk factors attributable to permanent versus temporary hearing loss following these procedures. Case 1 has already been published previously in 2019;Reference Alwan and Hurtado5 however, it is summarised here to establish a pattern of two patients who presented very similarly within one year of each other at our centre, both of whom suffered permanent hearing loss. Informed patient consent was sought and granted by the new case we report in this article. Ethical approval was not required for our literature review.

Case 1

A 25-year-old female, primigravida and primipara, underwent an emergency caesarean section because of prolonged latent phase of labour and foetal distress concerns. She underwent spinal-epidural anaesthesia prior to her caesarean section. An 18-gauge needle was used for the epidural catheter placement, and loss of resistance technique was used to identify the epidural space. The needle was inserted 5.5 cm cephalad into the epidural space at L3-4. Twelve ml of 0.2 per cent ropivacaine and 16 micrograms of fentanyl was injected, followed by a ropivacaine and fentanyl infusion. Surgery was completed without any intra-operative complications. Haemodynamic parameters remained within normal limits throughout the operation. The patient's epidural catheter was removed within 12 hours post-surgery.

The following day, the patient complained of vertigo and light headedness but no headache. The patient was discharged home on the second post-operative day. That same day at home the patient noted right ear tinnitus, aural fullness and hearing loss associated with a sense of unbalance. She was seen by her local primary care physician and was prescribed intranasal corticosteroids for possible Eustachian tube dysfunction. Her symptoms persisted for two weeks and an audiological assessment diagnosed sensorineural hearing loss. Urgent ENT specialist advice was sought over the phone, and the patient was commenced on oral prednisolone (1 mg/kg a day for 7 days, then weaned). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was normal. A high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated an enlarged right cochlear aqueduct. Repeat audiological assessment two weeks later showed no pure tone audiometry change but an improvement in speech discrimination (53–90 per cent). The patient was seen in an ENT clinic, with examination including microscopic otoscopy being unremarkable. Repeat audiology at 4 and 10 months showed no change. The patient was recommended hearing amplification which she declined. A recommendation to avoid further spinal-epidural anaesthesia was given.

Case 2

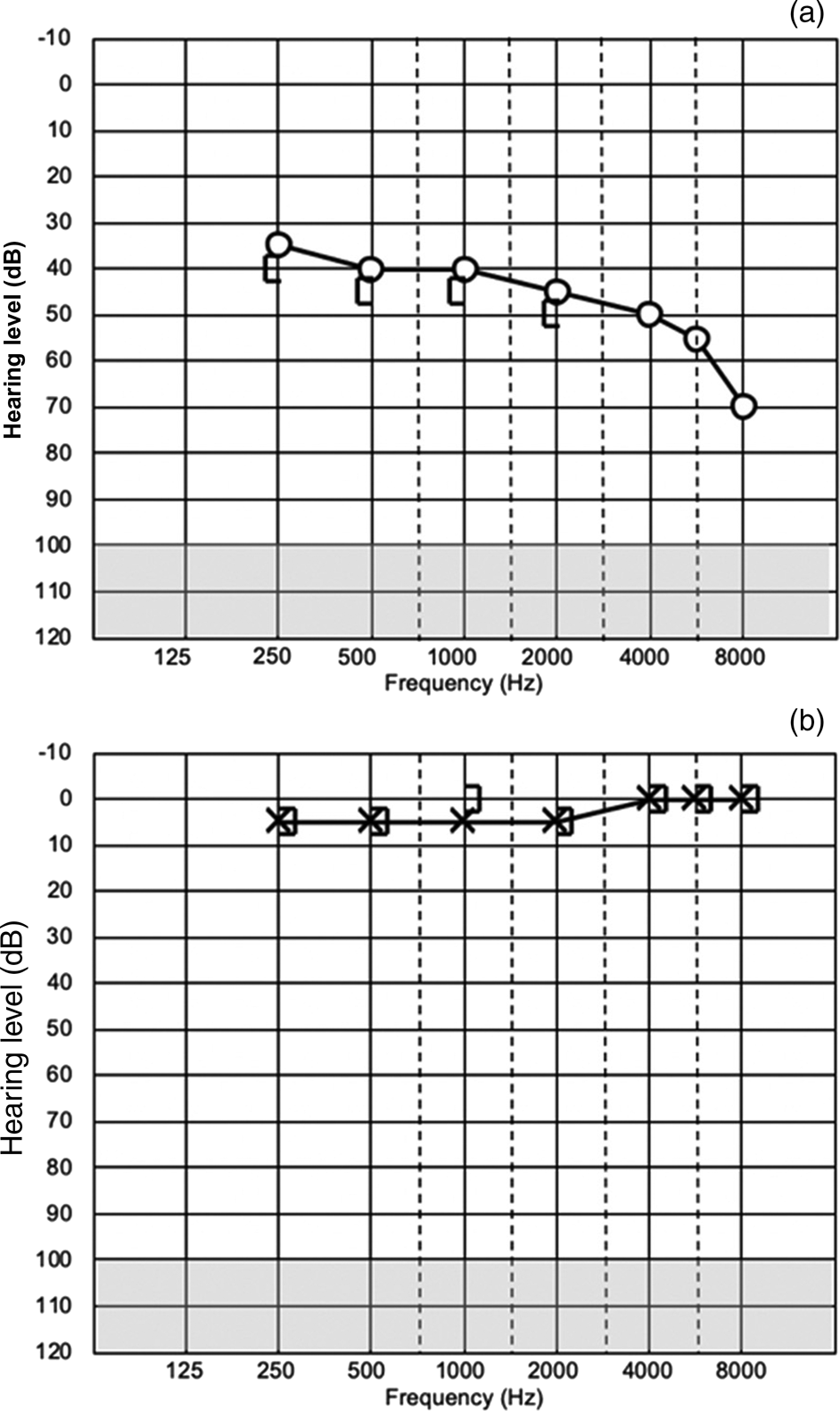

A 29-year-old female with no past medical history underwent spinal anaesthesia for a planned caesarean section. A 25-gauge needle was used in the L4-5 space and Marcaine and fentanyl were used to achieve anaesthesia. The caesarean section was completed without complications and the patient's haemodynamic parameters were within normal limits throughout the procedure. The patient reported experiencing right aural fullness and severe vertigo as soon as she was taken from the delivery suit to recovery. The following day she reported right ear non-pulsatile tinnitus, hearing loss and an ongoing sense of unbalance. She was discharged home on day 3 post-surgery and attended her primary care physician the same day, who diagnosed her with suspected benign positional paroxysmal vertigo and recommended re-accommodation manoeuvres. Persistent symptoms for two weeks prompted a referral for audiology evaluation, which showed a right-sided sensorineural hearing loss (Figure 1). She was referred to an ENT specialist who prescribed oral corticosteroids for two weeks. The MRI and CT scan studies showed no gross abnormality, with a possible slight asymmetry of the lateral portion of the right cochlear aqueduct being more patent than the left (Figure 2). The patient's balance returned to normal; however, her right ear hearing loss and tinnitus remained unchanged 16 months later at subsequent review.

Fig. 1. Patient's audiogram two weeks after symptom onset showing: (a) right ear and (b) left ear.

Fig. 2. Patient's axial plane computed tomography scan.

Search strategy and study selection

The search was conducted using PubMed, Ovid Medline and Embase databases from establishment until September 2020. Abstracts were identified using terms related to hearing loss (‘hearing loss’, ‘sensorineural’, ‘SNHL’) and spinal puncture (‘spinal anaesthesia’, ‘epidural anaesthesia’, ‘dural puncture’ and ‘lumbar puncture’). Papers that described no hearing loss, animal studies and studies published in non-English languages were excluded. There was no publication year restriction imposed. A total of 15 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria for analysis. The search strategy performed in September 2020 resulted in 145 articles. Eighteen articles underwent full-text evaluation and 16 were included for analysis (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS® statistical software (version 25.0). Fisher's exact test was performed to assess the relationship between delay in initiation of treatment and patient outcomes as well as patient age and outcomes.

Results

There are 21 cases (including our own) with sensorineural hearing loss post-lumbar puncture reported in the currently available literature spanning from 1986 until 2020 (Table 1). The median age of occurrence was 44 years, and the age range was 25–66 years. Of the 21 cases reported, 15 were female patients. Eleven patients underwent spinal anaesthesia for a surgical procedure prior to experiencing hearing loss,Reference Alwan and Hurtado5–Reference Lee and Peachman12 seven underwent a diagnostic lumbar punctureReference Michel and Brusis7,Reference Lybecker and Andersen13–Reference Zetlaoui, Gibert and Lambotte17 and three patients underwent an epidural anaesthesia for a surgical procedure.Reference Field and Drake18–Reference O'Shaughnessy, Fitzgerald, Katiri, Kieran and Loughrey20 Of the three patients who underwent epidural anaesthesia, two reported a noted dural tear with CSF leak.Reference Field and Drake18,Reference Kuselan and Selvaraj19 Fourteen cases reported the size of the needle used for their lumbar procedure, with needle sizes ranging from 16 gauge to 25 gauge. Nine patients experienced hearing loss bilaterally, seven in the left ear only and five in the right ear only.

Table 1. Documented cases of sensorineural hearing loss following spinal anaesthesia, epidural anaesthesia or lumbar puncture

F = female; M = male; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; CT = computed tomography; PTA = pure tone average; IV = intravenous

Twelve patients (57 per cent) reported concurrent headache associated with their hearing loss. Other symptoms experienced by patients included tinnitus (11 patients, 52 per cent), vertigo (7 patients, 33 per cent) and vomiting (4 patients, 19 per cent). No patients had hearing loss alone. Median time of onset of symptoms post-procedure was one day, with the range being immediately post-procedure to four days post-procedure. Patients were investigated with a mixture of audiology, CT and MRI. One case did not report which investigations were undertaken,Reference Field and Drake18 and another did not conduct audiology because of rapid symptom onset, treatment and symptom resolutionReference Kuselan and Selvaraj19. Of the remaining cases, eight were investigated with audiology alone,Reference Wang6,Reference Michel and Brusis7,Reference Lee, Yoo, Kim, Cho and Jeong11,Reference Lee and Peachman12,Reference Pogodzinski, Shallop, Sprung, Weingarten, Wong and McDonald16 five with MRI and audiology,Reference Michel and Brusis7–Reference Sahin, Terzioglu and Yigit10,Reference O'Shaughnessy, Fitzgerald, Katiri, Kieran and Loughrey20 three with CT and audiology,Reference Lybecker and Andersen13,Reference Nakaya, Morita and Horiuchi15,Reference Zetlaoui, Gibert and Lambotte17 and three with CT, MRI and audiologyReference Alwan and Hurtado5,Reference Johkura, Matsushita and Kuroiwa14 .

Median time of treatment commencement post-symptom presentation was 4 days, with the range being 1 to 34 days. Patients were treated with an autologous epidural blood patch in eight cases,Reference Lee and Peachman12,Reference Lybecker and Andersen13,Reference Nakaya, Morita and Horiuchi15–Reference O'Shaughnessy, Fitzgerald, Katiri, Kieran and Loughrey20 with one of these cases trialling intravenous hydrocortisone initially, then performing an epidural blood patch.Reference Nakaya, Morita and Horiuchi15 Five patients were managed with intravenous therapy alone (corticosteroids,Reference Wang6,Reference Michel and Brusis7 and one case of intravenous prednisolone and piracetamReference Sahin, Terzioglu and Yigit10). Four patients were managed with oral corticosteroidsReference Alwan and Hurtado5,Reference Kilickan, Gurkan and Ozkarakas8,Reference Benson and Redfern9 with one of these pairing it with transtympanic gentamicin.Reference Kilickan, Gurkan and Ozkarakas8 One case was managed with concurrent intravenous, oral and transtympanic corticosteroids.Reference Lee, Yoo, Kim, Cho and Jeong11 One case was given no treatment and observed.Reference Johkura, Matsushita and Kuroiwa14 Two cases did not report what treatment was prescribed.Reference Michel and Brusis7

Eleven patients experienced full recovery following treatmentReference Wang6,Reference Michel and Brusis7,Reference Sahin, Terzioglu and Yigit10,Reference Lee and Peachman12,Reference Lybecker and Andersen13,Reference Nakaya, Morita and Horiuchi15,Reference Pogodzinski, Shallop, Sprung, Weingarten, Wong and McDonald16,Reference Field and Drake18,Reference Kuselan and Selvaraj19 with five cases reporting complete resolution of symptoms within 24 hours after epidural blood patch.Reference Lee and Peachman12,Reference Lybecker and Andersen13,Reference Nakaya, Morita and Horiuchi15,Reference Pogodzinski, Shallop, Sprung, Weingarten, Wong and McDonald16,Reference Field and Drake18,Reference Kuselan and Selvaraj19 Of the remaining cases that experienced full recovery, 4 cases reported symptom resolution within one week,Reference Wang6,Reference Michel and Brusis7,Reference Sahin, Terzioglu and Yigit10 and one case reported symptom resolution at follow up after 28 days.Reference Michel and Brusis7

Five cases reported partial improvement;Reference Kilickan, Gurkan and Ozkarakas8,Reference Benson and Redfern9,Reference Lee, Yoo, Kim, Cho and Jeong11,Reference Johkura, Matsushita and Kuroiwa14,Reference Zetlaoui, Gibert and Lambotte17 pure tone average (PTA) results for these patients are listed in Table 1. One case did not report the PTA.Reference Zetlaoui, Gibert and Lambotte17 These patients were followed up for a median of 20 weeks (range of 1 week to 3 years).

Five cases reported no recovery of auditory function following treatment.Reference Alwan and Hurtado5,Reference Michel and Brusis7,Reference O'Shaughnessy, Fitzgerald, Katiri, Kieran and Loughrey20 Of these patients, two were treated with oral corticosteroids,Reference Alwan and Hurtado5 one was treated with intravenous corticosteroids,Reference Michel and Brusis7 one with an epidural blood patchReference O'Shaughnessy, Fitzgerald, Katiri, Kieran and Loughrey20 and one case did not specify the treatment delivered.Reference Michel and Brusis7 Median follow up for these five patients was 24 weeks (range of 12 to 52 weeks).

When comparing the median time (in days) between symptom presentation and initiation of treatment between the patients that experienced full recovery (n = 11) and the patients that either experienced partial or no recovery (n = 9, excluding the patient that received no treatment), a significant difference was found (2 and 10 days, respectively; p = 0.005). Comparison between the median age of these two groups demonstrated no statistically significant difference (full recovery versus partial or no recovery, 50 and 30 years, respectively; p = 0.07).

Discussion

Lumbar puncture, spinal anaesthesia and epidural anaesthesia are commonly used techniques for diagnostic purposes and anaesthesia prior to surgical procedures. However, rarely they may cause neurological complications such as sensorineural hearing loss, vertigo, tinnitus and headache. There are potentially severe consequences of unilateral sensorineural hearing loss on quality of life from the impact of reduced speech recognition in noise, sound localisation and severe tinnitus.Reference Mattox and Lyles21,Reference Vannson, James, Fraysse, Strelnikov, Barone and Deguine22

The incidence of hearing loss post-spinal puncture procedures is difficult to establish, showing significant variability in previous reports,Reference Fog, Wang, Sundberg and Mucchiano23–Reference Schaffartzik, Hirsch, Frickmann, Kuhly and Ernst27 with some studies noting that subclinical hearing loss, demonstrable on audiology but too subtle to be noticed by patients, may be a contributing factor to the correct reporting of the incidence of this phenomenon.Reference Erol, Topal, Arbag, Kilicaslan, Reisli and Otelcioglu1 In 2009, Erol et al. demonstrated that 7 out of 15 patients who underwent spinal anaesthesia with a 25-gauge Quincke needle had some degree of measurable hearing loss on audiology, but reported no hearing loss subjectively, and no patients reported headache, vertigo or tinnitus.Reference Erol, Topal, Arbag, Kilicaslan, Reisli and Otelcioglu1 Headache, vertigo and tinnitus may be clinical implications of hearing loss after anaesthesia,Reference Kilickan, Gurkan and Ozkarakas8 with approximately half of the reported cases experiencing headache, and all of the reported cases experiencing concurrent symptoms along with their hearing loss.

The pathophysiology of the relationship between dural puncture and hearing loss requires an understanding of the intricacies of the physiological systems that govern human hearing. The anatomy of hearing can be divided into the peripheral apparatus (comprising of the external, middle and inner ear, as well as the cochlear and vestibular divisions of the auditory nerve), and the central mechanisms (hearing pathways, auditory centres and central balance mechanisms). The CSF dynamics and pressures are important for auditory function of the inner ear. Endolymph is present within the inner ear in the membranous labyrinth. Likewise, perilymph, which is a filtrate of CSF and blood, is present in the cochlea. These two substances engage in passive diffusion and active transport of ions, and their pressures and dynamics are therefore intricately linked. When a significant dural puncture occurs either from regional anaesthesia or diagnostic lumbar puncture, the CSF pressure decreases, and the perilymph is shifted into the subarachnoid space via the cochlear aqueduct. Subsequently there is a decrease in perilymphatic pressure. This disruption ultimately results in increased pressure of endolymph within the cochlear duct, resulting in endolymphatic hydrops, resulting in a displacement of the hair cells on the basement membrane, resulting in a low-frequency sensorineural hearing loss.

It is therefore intuitive that two factors ought to govern the predisposition to hearing loss following dural puncture: the patency of the patient's cochlear aqueduct, and the amount of CSF lost during the dural tear, owing to the size and shape of the needle used. Both of these factors have been investigated previously. Previous anatomical studies have demonstrated that the patency of the human cochlear aqueduct diminishes with age,Reference Wlodyka28,Reference Yildiz, Solak, Iseri, Karaca and Toker29 and some studies have further demonstrated that the occurrence of hearing loss after spinal anaesthesia is more common in younger patients.Reference Gultekin and Ozcan30 However other studies have not shown the same significance.Reference Ok, Tok, Erbuyun, Aslan and Tekin31,Reference Finegold, Mandell, Vallejo and Ramanathan32 While early studies from 1992 and 1993 have suggested that aberrantly enlarged cochlear aqueducts may not exist,Reference Jackler and Hwang33,Reference Swartz34 more recent investigations with higher resolution CT scans now offer new insights into studying cochlear aqueduct variations in living patients.Reference Mukherji, Baggett, Alley and Carrasco35,Reference Atturo, Schart-Moren, Larsson, Rask-Andersen and Li36 The statistical analysis in our cases did demonstrate that patients who experienced full recovery had a higher median age compared with those who did not completely recover (50 versus 30 years, respectively), and while approaching significance, it was not found to be significant (p = 0.07). However, with such limited cases it is difficult to say with confidence whether there is a relationship between propensity for full recovery and patient age.

Needle size and shape have previously been demonstrated to be related to dural leakage for in vitro studies, and therefore these parameters may affect the incidence of hearing loss.Reference Ready, Cuplin, Haschke and Nessly37 Several clinical studies have subsequently demonstrated that larger calibre and cutting edge needles have greater incidence of hearing loss after spinal anaesthesia.Reference Erol, Topal, Arbag, Kilicaslan, Reisli and Otelcioglu1,Reference Fog, Wang, Sundberg and Mucchiano23,Reference Sundberg, Wang and Fog38 Erol et al. demonstrated that cutting edge needles (Quincke needles) resulted in more hearing loss after spinal anaesthesia when compared with non-cutting edge needles of the same size.Reference Erol, Topal, Arbag, Kilicaslan, Reisli and Otelcioglu1 Malhotra et al. demonstrated that 23-gauge cutting edge needles were associated with higher rates of hearing loss after spinal anaesthesia compared with 25-gauge cutting edge needles.Reference Malhotra, Iyer, Gupta, Raghunathan and Nakra39 Cutting edge needles are thought to cause more damage to the dural fibres and hence increase the CSF leak post-procedure, with larger calibre needles causing more damage.Reference Malhotra, Joshi, Grover, Sharma and Dutta40 It is interesting to note that previous studies have similarly reported lower rates of post-dural puncture headaches with non-cutting needles.Reference Parker and White41

The delay between symptom onset and initiation of treatment may be a contributing factor to complete versus partial or no recovery of auditory function.Reference Lawrence and Thevasagayam42 This is thought to be because of the halting of the inflammatory cell-death cascade in sudden sensorineural hearing loss, which can be achieved by either restoring CSF pressures promptly with an epidural blood patch or potentially with steroid therapy. When comparing the median time delay in treatment initiation, patients with full recovery had a statistically significant lower time delay compared with patients who did not recover fully (2 versus 10 days; p = 0.005). Prompt treatment has been supported by various studies and review articles; however, there is currently no consensus on an exact timeframe to maximise hearing outcomes, owing to the differing protocols of the trials investigating this relationship.Reference Chandrasekhar, Tsai Do, Schwartz, Bontempo, Faucett and Finestone43

A definitive treatment algorithm for sudden sensorineural hearing loss following lumbar puncture, spinal anaesthesia or epidural anaesthesia is difficult to construct given the rare and under-reported nature of this phenomenon. Nevertheless, it is important to have an approach with this subset of patients. The first point of note is that patients do not always specifically complain initially of hearing loss; tinnitus, aural fullness and a ‘roaring sound’ in the ears are frequently described, with classic post-dural puncture headache only being reported in roughly half of cases. It therefore follows that a high degree of suspicion is needed when patients report such symptoms following these procedures. Given time delays have been correlated with poorer outcomes, it is the authors’ recommendation that formal audiological assessment be undertaken as soon as possible, which may show a sensorineural hearing loss that is typically low frequency.

The initial treatment to consider in these patients is an autologous epidural blood path, with several cases reporting the resolution of symptoms within 24 hours of this procedure alone. Subsequent treatment options include more conventional therapy used in idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss and include a course of oral corticosteroid or transtympanic corticosteroid therapy and hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

• Sensorineural hearing loss following lumbar puncture or spinal or epidural anaesthesia is a rare phenomenon

• Most patients present with a combination of hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo, aural fullness and headache

• It is thought to occur because of decreased cerebrospinal fluid pressure transmitted through a patent cochlear aqueduct

• Prompt treatment is statistically associated with better outcomes

• Treatment options include epidural blood patch, oral or transtympanic corticosteroids, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy

• Approximately half of the cases reported in the literature experienced full recovery

Oral corticosteroid therapy is usually proposed as a first line treatmentReference Chandrasekhar, Tsai Do, Schwartz, Bontempo, Faucett and Finestone43,Reference Marx, Younes, Chandrasekhar, Ito, Plontke and O'Leary44 (traditionally prednisolone of 1 mg/kg a day as a single dose up to a maximum of 75 mg daily, given for 7 days and then weaned for another 7 days); however, given many of these patients are post-surgery, implications on wound healing, patient co-morbidities and lactation (or breastfeeding) impact must be taken into consideration.Reference Wang, Armstrong and Armstrong45 Transtympanic steroids can also be used as a single primary therapy,Reference Rauch, Halpin, Antonelli, Babu, Carey and Gantz46,Reference Mirian and Ovesen47 with evidence to support that intratympanic steroid injection can be beneficial to patients up to six weeks post-symptom onset.Reference Chandrasekhar, Tsai Do, Schwartz, Bontempo, Faucett and Finestone43 However, this requires otolaryngological expertise and may not be available to all patients in a timely fashion. Lastly, hyperbaric oxygen therapy can be used for initial treatment when combined with oral corticosteroids within two weeks of symptom onset, or as salvage therapy within one month of symptom onset;Reference Chandrasekhar, Tsai Do, Schwartz, Bontempo, Faucett and Finestone43 however, resource limitations may make this treatment modality difficult for all patients. It is recommended that patients be followed up with repeat audiology at conclusion of their treatment and again six months post-treatment by otolaryngology specialists to assess for residual hearing loss or tinnitusReference Chandrasekhar, Tsai Do, Schwartz, Bontempo, Faucett and Finestone43,Reference Marx, Younes, Chandrasekhar, Ito, Plontke and O'Leary44 and consideration of further rehabilitation options, including use of hearing amplification, hearing implants and possible vestibular physiotherapy.

Conclusion

Hearing loss after spinal anaesthesia, epidural anaesthesia and lumbar puncture is a rare but previously reported occurrence, with permanent hearing loss being a possibility. The hallmarks of this event are prompt audiological complaints from the patient including tinnitus, vertigo, aural fullness and hearing loss, usually occurring within the first few days after the procedure, although symptoms may manifest immediately. This should be treated with a high degree of clinical suspicion, especially in patients with no previous audiological pathology. Prompt assessment with audiology, which normally shows a low-frequency sensorineural hearing loss, and timely epidural blood patch are recommended, as treatment delays are associated with permanent hearing loss. Alternative management options include oral corticosteroids, transtympanic corticosteroids and hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Final considerations must be given regarding potential risk to the patient undergoing future lumbar puncture, spinal or epidural anaesthetic procedures, including possible aggravation of hearing loss. From our study it cannot be confidently stated that younger patients are at higher risk; however, previous studies have demonstrated that younger patients, cutting edge needles and larger calibre needles are associated with poorer outcomes.

Competing interests

None declared