The First Emperor's (Qin Shihuangdi 秦始皇帝, r. 246–210 b.c.e.) Lishan necropolis, which extends over twenty-one square kilometers at present-day Lintong in Shaanxi province, has been under systematic probing and excavation since 1974, yielding findings that have already fascinated the world (Fig. 1). During 2001–2003 the Archaeological Team for Excavating the Qin Mausoleum (Qinling kaogudui 秦陵考古隊) probed into the inner structure of the emperor's tomb mound, which offers evidence about this mausoleum's creative synthesis of multiple prototypes from the Eastern Zhou period (771–221 b.c.e.). The First Emperor's gigantic mound, originally 515 by 485 meters in area and purportedly over 116 meters high, had remained a mystery for more than twenty-two centuries before the probing (Fig. 1). Despite years of exterior erosion, the tomb mound, over fifty meters high above the ground at the heart of the mausoleum, remains as the visually most compelling object in the entire necropolis.Footnote 1 Below the mound lies the unopened grave of the emperor, a well-protected world wonder whose richness may top anyone's imagination. Surprising data came from inside the rock-hard mound constructed of rammed earth. Unlike Eastern Zhou tomb mounds, earth samples extracted from inside this mound are not homogeneous, but results of different methods of earth ramming. The conventional way to explore this unusual phenomenon would require physically opening the mound, which is prohibited by the Chinese government due to its determination to leave this great historical site intact for the future generations. However, thanks to a remote sensing detector equipped with the latest geophysical technologies, Chinese archaeologists were able to scan and to reveal the interior physical structure of the mound without removing a shovel of earth.Footnote 2

Figure 1. Plan of the Walled Area in Lishan Necropolis, Lintong, Shaanxi Province. Late 3rd c. b.c.e. (after Kaogu yu wenwu 2010.5, 10, Fig. 1).

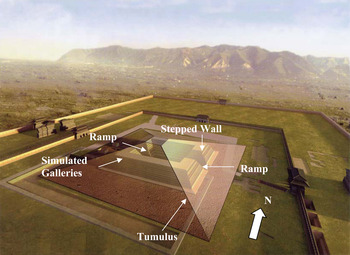

The result of the remote sensing scan demonstrates that the seemingly simple mound is in fact a complex construction made of two different types of rammed earth. One part of the mound is constructed of coarse-grained earth rammed with broad-headed hammers, and the other part, fine-grained earth done with narrow-headed hammers. Enclosing a rectangular zone, the fine-grained earth forms a wall cut through by two ramps in the west and the east respectively. This wall, thirty meters high with nine steps on each side, bounds a vertical shaft in the center. The exterior of this wall measures 168 by 141 meters at the base and the walled interior measures 124 by 107 meters at the top.Footnote 3 Remains of wooden structures were detected on some steps of the wall. The coarse-grained earth forms a tumulus to cover and conceal the wall from above and from the sides. The stratigraphy indicates that the wall must have been built first before it was eventually interred under the tumulus (Figs. 2a, 2b).

Figure 2a. Plan and Section of Earth Mound in Lishan Necropolis, Lintong, Shaanxi Province. Late 3rd c. b.c.e. (after Kaogu 2006.5, Fig. 1).

Figure 2b. (color online) Duan Qingbo's Reconstruction of the First Emperor's Tomb Mound, Lintong, Shaanxi Province. Late 3rd c. b.c.e. (after Duan Qingbo, Qin Shihuangdi lingyuan kaogu yanjiu, color plate).

To the archaeologists this magnificent nine-stepped wall distinguishes the First Emperor's tomb from all other Chinese tombs excavated so far.Footnote 4 But where did this innovative structure come from, and what was it built for, if this spectacular wall would eventually hide below the tumulus and become totally invisible? By comparing the major characteristics of this tomb mound with those of late Eastern Zhou royal tombs, this essay investigates the way in which this unprecedented structure derived and departed from early funerary traditions.Footnote 5 And by situating the tomb mound in its historical context, in which the imperial mausoleum was planned and constructed, this case study also enquires into the political and ideological agenda behind its creation.

Between “Tumulus Tomb” and “Shrine Tomb”: A Historiography

Before the discovery of the inner structure of the earth mound in the First Emperor's tomb, scholars had debated the mound's form and nature. The controversy centers on whether the present-day earthen heap is the remains of a simple earthen mound or those of a freestanding architectural construction.

Prior to the mid-twentieth century almost all records in traditional Chinese historiography agreed that the First Emperor's grave was surmounted by a high tumulus. Such a tomb that vertically consists of an underground burial shaft and an aboveground earthen heap is conventionally dubbed by Chinese archaeologists as the “tumulus tomb” (zhongmu 冢墓), which started to become popular in the early Eastern Zhou.Footnote 6 According to historian Sima Qian 司馬遷 (145 or 136–86 b.c.e.), grass and trees were grown on the First Emperor's tumulus to “simulate a mountain” (shu caomu yi xiang shan 树草木以象山).Footnote 7 Influenced by this traditional opinion, despite the fact that the tumulus appears stepped,Footnote 8 for a long time many modern Chinese archaeologists believed that the First Emperor's earthen mound was in the shape of a truncated pyramid, similar to the later Western Han (206 b.c.e.–8 c.e.) imperial tumuli in the vicinity of present-day Xi'an.Footnote 9

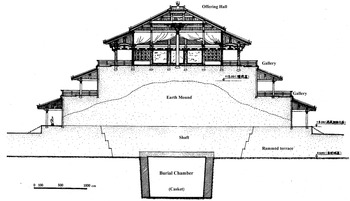

From the 1970s onwards, however, some Chinese scholars began to doubt their traditional view in light of a series of new archaeological discoveries. Their leader, architectural historian Yang Hongxun 楊鴻勛, questioned the pyramidic shape of the mound and contended instead that the earthen heap, as Victor Segalen once suggested, was actually in the shape of a stepped terrace. Yang's major evidence was the tomb of King Cuo ![]() (d. c. 310 b.c.e.), the next-to-last king of the Zhongshan 中山 state in present-day Pingshan in Hebei province, excavated in 1974.Footnote 10 In vertical section, the central grave generally consists of three parts: 1) an underground burial chamber and three smaller and shallower side pits around it; the burial chamber holds the king's casket (guo 椁), which encapsulates the coffins (guan 棺) and grave goods,Footnote 11 and side pits, more grave goods; 2) a larger shaft built directly above the burial chamber and covered by an earth mound; 3) a freestanding offering hall (wangtang 王堂 by inscription) atop the earth mound and the shaft (Fig. 3a).Footnote 12 To Yang Hongxun's eyes Cuo's offering hall, reconstructed by him as a three-story building, anticipated the First Emperor's stepped mound in form and function.

(d. c. 310 b.c.e.), the next-to-last king of the Zhongshan 中山 state in present-day Pingshan in Hebei province, excavated in 1974.Footnote 10 In vertical section, the central grave generally consists of three parts: 1) an underground burial chamber and three smaller and shallower side pits around it; the burial chamber holds the king's casket (guo 椁), which encapsulates the coffins (guan 棺) and grave goods,Footnote 11 and side pits, more grave goods; 2) a larger shaft built directly above the burial chamber and covered by an earth mound; 3) a freestanding offering hall (wangtang 王堂 by inscription) atop the earth mound and the shaft (Fig. 3a).Footnote 12 To Yang Hongxun's eyes Cuo's offering hall, reconstructed by him as a three-story building, anticipated the First Emperor's stepped mound in form and function.

Figure 3a. Reconstruction of Superstructure of Cuo's Tomb, Pingshan, Hebei Province. 4th–3rd c. b.c.e. (after Yang Hongxun, Gongdian kaogu tonglun, Fig. 162).

Cuo's offering hall exemplifies the early Chinese method of building a single- or multi-stepped earthen terrace as the foundation for elevated wooden structures.Footnote 13 Before excavation Cuo's tomb appeared as if it were covered by a tumulus more than fifteen meters high.Footnote 14 But the excavators soon uncovered a group of column holes and bases spreading along the four sides of a ruined earthen foundation as they dug into the earthen mound. The architectural remains indicate that the tumulus was in fact a ruined multistory building lying beneath a layer of soil deposit caused by centuries of erosion. In Fu Xinian 傅熹年 and Yang Hongxun's reconstructions, this once freestanding building consists of four levels altogether. While the lower three levels are wooden galleries constructed on a stepped rammed earth core, the topmost level features a timber-structure hall or pavilion, which has been designated by many scholars as a funerary shrine (Fig. 3a).Footnote 15 Chinese archaeologists coined the term “shrine tombs” (xiangtangmu 享堂墓) to distinguish such tombs, characterized by a freestanding building on top of an underground burial, from the previously known “tumulus tombs.”Footnote 16

Although early discoveries of “shrine tombs” prior to the 1970s were hardly reminiscent of the First Emperor's mound, for they contained no comparable high earthen constructions,Footnote 17 the excavation of Cuo's tomb demonstrates that in a “shrine tomb” the aboveground wooden structure could be based on a multistepped earthen terrace, which in ruination might resemble a tumulus. The discovery of Cuo's tomb led Yang Hongxun to believe the First Emperor's stepped mound was a parallel of Cuo's stepped terrace in the tradition of “shrine tombs.”

Many Chinese archaeologists, however, rejected Yang's theory and insisted that no architectural remains of a freestanding building have been spotted above the earth mound.Footnote 18 Had it been a shrine on top of the First Emperor's mound, they reasoned, there should have been column holes and bases, walls, or floors such as those found in Cuo's tomb left in situ. Another objection was raised by those who believed in the accounts of the Qin mausoleum reported in Shiji and Hanshu. Assuming that the mound was eventually covered with plants, these scholars wondered whether it was possible at all to have the greened mound simultaneously surmounted by a building.Footnote 19 A third opinion tried to reconcile the two opposite camps by supposing that, due to the severe corrosion of the mound, particularly its upper part, all architectural remains had completely disappeared from the site.Footnote 20

The discovery of the nine-stepped wall buried beneath the First Emperor's mound reignited the almost deadlocked debate. Shortly after the release of the excavation report in 2007, Yang Hongxun used this wall as evidence to support his early theory that the First Emperor's tomb is a “shrine tomb” rather than a “tumulus tomb.” He argued that the emperor's nine-stepped earthen mound was an enlarged version of Cuo's three-level shrine, whereas the present-day stepped mound, as observed by Segalen, was its diminished body in ruin after two thousand years of natural corrosion. Based on this idea, he reconstructed the tomb mound into “a great spectacular nine-story shrine,” with galleries constructed on each of the nine steps.Footnote 21

Despite its many merits, Yang's reconstruction of the First Emperor's lost building on his burial did not consider three archaeological facts of the emperor's mound. All these have been noted in Duan Qingbo's 段清波 latest reconstruction of the tomb mound in 2011 (see Fig. 2b).

First, the First Emperor's stepped structure is not a multistory building based on a solid earthen terrace as Cuo's three-stepped freestanding shrine, but a nine-stepped wall bounding a burial shaft.Footnote 22

Second, whereas in the reconstruction, column or pillar holes of the multistory shrine are spread evenly on every level of the terrace, the excavation report only ascertains that “certain steps contain traces identifiable as column holes.” This is to say, not all steps of the terrace equally bear column holes.Footnote 23 In a research paper published in 2009, Duan, the leader of the Excavation Team, supplemented the excavation report with the following additional details:

四面牆的外側上部臺階上發現分布較為廣汎、堆積較厚的瓦片,瓦片堆積淩亂。靠近頂面的臺階上瓦片尤多,中下部臺階上的瓦片也有零星發現。但臺階式牆狀的頂面幾乎沒有見到瓦片。

On the upper steps of the four walls we discovered a wide distribution of thick layers of (roof) tile fragments in a disrupted condition. These tile fragments appeared in large numbers especially on the steps near the top (of the terrace). They were only spotted here and there on the middle and lower steps. But we found almost no tile fragments on the top of this wall-like terrace.Footnote 24

This important description suggests that roofed structures might have been constructed only on the upper, except for the topmost steps, of the wall. After the roofs had crashed down, the steps below them were covered by their ruins, including the imperishable fragments of the roof tiles. The few fragments left on the middle and lower steps were probably pieces that fell accidentally from the upper steps as the top buildings collapsed.Footnote 25

The third archaeological fact missing from Yang's reconstruction is the tumulus that eventually concealed the nine-stepped wall. No traces of burnt charcoal were detected on the steps of the wall,Footnote 26 suggesting that the crash of roofed structures was caused not by hostile destruction but perhaps by the pounding of earth to build the tumulus. In other words, the First Emperor's nine-stepped wall was a hollow terrace eventually to be interred, whilst Cuo's offering hall was designed to be freestanding.Footnote 27

How could Yang Hongxun, a highly experienced architectural historian who meticulously reconstructed Cuo's aboveground structure, ignore these obvious archaeological facts? He probably succumbed to a traditional conviction that the “tumulus tomb” and the “shrine tomb” were two contradictory archaeological types. In this view, the First Emperor's tomb mound must fall into either this or that type. In fact the emperor's tomb lies between these two rigid typological categories: on the one hand, like a “shrine tomb” it features a terrace with a temporary building constructed on it, and on the other hand, covered entirely beneath an earthen heap, it appears no different from a “tumulus tomb.”

Facing this problem, Duan Qingbo in his 2011 monograph on the Lishan necropolis proposes a typological solution. He suggests that this paradoxical tomb mound might be the only discovered form of a transitional archaeological type (guodu xingtai 過渡形態) that marks the evolution from the “shrine tomb” to the “tumulus tomb.” But questions remain. Even if this evolution could be true in the Qin area, it sounds a little paradoxical when a type contains only one singular example. What's more, as is demonstrated below, this singular example is so complex that it hardly belongs in any type but instead incorporates previous funerary traditions.

The Incorporate Tomb Mound

Behind its seemingly strange complexity, the First Emperor's tomb mound consists of basic components taken from the royal tombs in the late Eastern Zhou period. These mainly include the tumulus, the stepped wall that borders the burial shaft, and the temporary funerary structure, which remained visible only during the period of construction of the mausoleum and the imperial funeral (see Figs. 2a, 2b). But the way in which these three components were incorporated in a new project defines the true originality of the mound. This section focuses on the latter two components, for the outmost tumulus, an earthen heap, is relatively simple.

The nine-stepped wall eventually hidden beneath the tumulus combines a high wall with a stepped terrace. This complex structure finds one of its closest prototypes in Cuo's tomb: the aboveground shaft bordered by a six-stepped earthen terrace, on which the freestanding shrine once stood.

In the excavation report the remains of this terrace are labeled as Cuo's “aboveground burial chamber” (dishang mushi 地上墓室), which sits above the burial chamber dug into the ground.Footnote 28 Reminiscent of the First Emperor's nine-stepped wall, this terrace is a high-stepped earthen wall that bounds the aboveground shaft, approached by two ramps in the north and in the south respectively (Fig. 3b). After the coffin had settled down in the burial chamber through the ramps, the aboveground shaft was then filled with rammed earth to form the foundation of the freestanding shrine (see Fig. 3a).Footnote 29 Although unlike the First Emperor's stepped wall, Cuo's terrace was considerably lower and was rectangular rather than square, the latter's general structure is similar to the former's.Footnote 30 With an aboveground stepped terrace hollow in the center to contain the underground burial chamber, both the Qin and the Zhongshan tombs vertically consist of three levels: the bottom level of the casket, the middle level of the aboveground shaft, and the top level of the earthen mound.

Figure 3b. Plan and Section of Six-stepped Earth Terrace in Cuo's Tomb, Pingshan, Hebei Province. 4th–3rd c. b.c.e. (by author after Hebei sheng wenwu yanjiusuo, Cuo mu, vol. 1, 16, fig. 7; 23, fig. 12).

This vertical leveling is not just a result of modern reconstruction, but probably part of the original design. Jia Shan 賈山 (fl. 179 b.c.e.), an early Western Han scholar active only a few decades after the fall of the Qin dynasty, keenly noted the three-level structure of the First Emperor's tomb:

死葬乎驪山,吏徒數十萬人,曠日十年,下徹三泉,合采金石,冶銅錮其內,桼塗其外,被以珠玉,飾以翡翠,中成觀游,上成山林。

[The First Emperor] was buried at Mt. Li (Lishan) after he died. Several hundreds of thousands of officials and laborers took ten years to dig into the Three Springs. They mined metal and stone and melted bronze to seal the interior. They applied varnish onto the [coffin's] exterior, covered [the coffin] with pearls and jades, and decorated it with kingfishers' feathers. They turned the middle (of the tomb) into a pleasure ground, and the top into a mountain and forest.Footnote 31

The three levels in Jia's observation well match the archaeological data: the casket and coffin ornamented with precious stones lay at the bottom,Footnote 32 the pleasure ground (guanyou 觀游, literally “viewing and playing”) sat in the middle, and the mound rich with vegetation stood on the top.Footnote 33

Cuo's terraced tomb mound, however, was not the only prototype for the First Emperor's innovative project. Recent archaeological work has demonstrated that such aboveground terraced structures existed in both “shrine tombs” and “tumulus tombs” across China during the late Eastern Zhou. While excavating the royal cemetery of the Qi state in present-day Linzi in Shandong province, archaeologists discovered the upper part of the burial shaft in several tombs was formed by similar stepped walls constructed of rammed earth. Whereas other tombs in this cemetery featured more traditional burial shafts dug totally underground, these special tombs appeared as if they were slightly lifted up from below the ground. Noting their distinct structures, the excavators call these tombs “the elevated type” (qizhongshi 起塚式) (Fig. 4).Footnote 34 Similar examples have also been unearthed in two fourth- or third-century b.c.e. Chu tombs in south China. Ma'anzhong Tomb, located in present-day Huaiyang in Henan province, and Jiuliandun Tomb 1, in present-day Zaoyang in Hubei province, were analogous to the Qi elevated type. Both tombs featured an aboveground stepped wall in one or more levels rimming the upper opening of the tomb shaft.Footnote 35 Despite the fewer steps and lower profile, these relatively modest Qi and Chu stepped walls were similarly concealed beneath a tumulus, onto which no wooden structures were added.Footnote 36 In this regard, these stepped walls were forerunners of the First Emperor's much higher mound.

Figure 4. Plan and Sections of Tomb LXM1 in Qi Royal Cemetery at Linzi, Shandong Province. Late Eastern Zhou period (after Shandong sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo, Linzi Qi mu, 176).

Aboveground terraced structures have also been spotted in the royal mausoleum of the Zhao state, dated approximately to the same period, in present-day Handan in Hebei province, though in a modified form. In this case, since the tombs are unopened, it remains unclear whether these structures are walls or just solid earthen terraces. In whichever situation, while the Qi or Chu stepped wall was totally concealed under a larger earthen mound, the Zhao terrace forms the rectangular earthen foundation of a much smaller truncated pyramidic tumulus, which spires in the center of the terrace (Fig. 5).Footnote 37 In Duan's reconstruction, the First Emperor's nine-stepped wall is relatively closer to the Qi and Chu examples, because it is also covered entirely beneath the tumulus.

Figure 5. Plan and Section of Zhao Royal Mausoleum 3 at Handan, Hebei Province. Late Eastern Zhou period (after Kaogu 1982.6, Fig. 5).

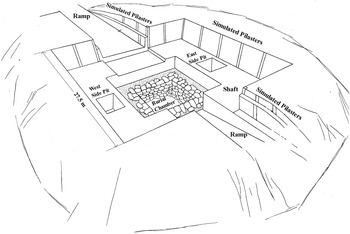

Unlike its Qi, Chu, or Zhao counterparts, however, the First Emperor's tomb mound was more than a stepped wall; it also simulated a multistory building with roofed wooden structures built on the steps near the top. Besides the fragments of roof tiles, which I mentioned earlier, remains of column holes filled with wood ash were detected on some of the upper steps of the terrace. These traces indicate the use of real wooden poles in this temporary building. Because the top of the mound was found empty of architectural remains, this temporary building might have simulated a series of galleries erected but on the upper levels of the nine-stepped wall (see Fig. 2b).

Simulating galleries in the aboveground shaft did not begin with the First Emperor. Among the many late Eastern Zhou high-ranking tombs sharing the same feature, Pingshan Tomb 6, another royal tomb of the Zhongshan state (dated late 4th c. b.c.e.), stands out as the most vivid demonstration of the original design to transform the tomb shaft into a simulated edifice.

Slightly smaller though it was, Pingshan Tomb 6 resembled Cuo's tomb in plan and structure (Fig. 6). Plastered and whitened, the interior walls of the aboveground shaft, in shape of a reversed truncated pyramid, were embellished and decorated with simulated pilasters spaced evenly along the walls.Footnote 38 Set in the slightly sloping walls, these false pilasters constituted by vertically stacked mud bricks were totally functionless. To the excavators, this pillared gallery, reminiscent of architectural images on Eastern Zhou pictorial bronze vessels with pillars or pilasters evenly spaced on different levels,Footnote 39 simulated a multistory building.Footnote 40 Such false pillared galleries were not unique to the Zhongshan state; the excavation of Xuliangzhong Tomb 8 in a royal cemetery of the Yan state at present-day Yixian, Hebei province, brought to light another well-preserved example.Footnote 41

Figure 6. Line Drawing of Zhongshan Tomb 6 at Pingshan, Showing Simulated Pilasters on Walls of the Shaft and Ramps, Pingshan, Hebei Province. Late 4th c. b.c.e. (after Hebei sheng wenwu yanjiusuo, Zhanguo Zhongshanguo Lingshou cheng, Fig. 89).

Whereas the Zhongshan and Yan galleries were total architectural simulacra without actual functions, the Qin counterparts consisted of real wooden posts and tiles. According to literary accounts, constructing a real building above the underground burial was probably an even older idea than architectural simulation.Footnote 42

Several wooden buildings were uncovered above large burials in the Wei, Han, and Zhao states. While unearthing Guweicun Tomb 1 (dated 3rd c. b.c.e.) in a Wei royal cemetery in present-day Huixian, Hebei province, the careful excavators noted an utterly disintegrated wooden sloping roof as they dug into the tomb shaft as deep as about four to five meters above the casket. Wooden pillars, each five meters tall, were set in the west and east walls of the shaft to support the roof. Small holes (used as mortises) were also dug in the walls to hold beams, which might have joined the pillars to form a complex wooden structure.Footnote 43 Similar wooden structures in the approximately contemporaneous cemeteries in present-day Luoyang in Henan province and in Xintian in Shanxi province further suggested that these were the roofs of simulated pavilions to shelter the caskets.Footnote 44 Two recently unearthed royal tombs of the Han state at present-day Huzhuang in Xinzheng in Henan province finally confirmed the function of such roofs (Fig. 7).Footnote 45 According to the preliminary report of the excavation, in each of the two tombs the coffin was encased in a house-shaped wooden structure under a sloping roof. Although these simple roofed wooden structures are no match for the highly sophisticated multistory galleries of the First Emperor, in terms of sheltering the burial in the form of building from above, they are of no fundamental difference.

Figure 7. Sloping Roof in the Shaft of a Royal Tomb of the Han State at Huzhuang, Xinzheng, Henan Province. Late 3rd c. b.c.e. (after Huaxia kaogu 2009.3, color pl. XI–6).

Although it is almost impossible to pin down the exact models for the First Emperor's tomb mound, the design might have referred, directly or indirectly, to such slightly earlier examples as the tombs at Pingshan (Zhongshan), Linzi (Qi), Ma'anzhong and Jiuliandun (Chu), Handan (Zhao), Huixian (Wei), as well as Huzhuang (Han) (Table 1). Unlike the burial to be concealed underground, the mound remained visible to the public and could be examined by careful viewers. What's more, further knowledge of the tomb's interior structure might have been transmitted from state to state as foreign envoys were often invited to attend royal funerals, during which they could first-handedly see the graves in situ.Footnote 46

Table 1. Late Eastern Zhou Mausoleums Outside of the Qin in Comparison with the Lishan Mausoleum of the First Emperor.

Despite the many elements shared with the late Eastern Zhou counterparts, however, the unique way in which these elements were incorporated into the First Emperor's tomb mound demonstrates the anonymous designer's creativity. For example, whereas in Pingshan Tomb 6 the simulated galleries were located along the interior walls of the aboveground shaft, in the First Emperor's tomb they moved out onto the exterior steps of the shaft (or the terraced wall) so that they could catch the attention of outside viewers from afar at least during the funerary ceremony. The First Emperor's mound also differs from its Zhongshan counterparts in following the Qi and Chu examples, which removed the freestanding shrine away from the earthen terrace. By such borrowing and alteration, the First Emperor's tomb mound absorbed a variety of existing funerary practices but remained distinctive as a whole.

Cultural Context of the Tomb Mound

But why did the tomb mound end up this way? One can assume that its designer might just have followed a cultural convention or tradition, with rules and norms on how tombs should be made. Many archaeologists shared this assumption in the past a few decades. Since during the late Eastern Zhou period, the Qin state was based in present-day Shaanxi in the west and the other states later vanquished by the Qin were located in the east, the dichotomy of “Qin” and “East” became a tempting conceptual framework for previous studies of the mausoleum.

This inquiry began with an effort to define the “Qin” and “East” funerary cultures based on the latest archaeological evidence. Following the discoveries of the Wei, Zhao, and Zhongshan mausoleums during the 1950s and 1970s, historian Yang Kuan 楊寬 in his 1984 essay on the cemetery plan of the Lishan necropolis demonstrated that the First Emperor's mausoleum was based collectively on royal mausoleums of the Warring States.Footnote 47 Although Yang Kuan's term zhanguo 戰國, or “warring states,” covered all the states in the late Eastern Zhou, the phrase was taken up by some archaeologists to refer exclusively to the eastern states other than the Qin. In 1987, archaeologist Shang Zhiru 尚志儒 argued that the First Emperor's mausoleum incorporated more elements from the pre-imperial Qin mausoleums than from the eastern “six states” (liuguo 六國) or zhanguo during the late Eastern Zhou.Footnote 48 Following Shang's nuanced division, in 1989 archaeologist Ma Zhenzhi 馬振智 surveyed the newly probed Qin royal mausoleums in the Eastern Zhou period and summed up a cultural distinction of the Qin mausoleums forged during the fourth to the third centuries b.c.e. against their “eastern” (guandong 關東) counterparts.Footnote 49 He listed several characteristics considered unique to the Qin funerary culture, including most notably the east-west orientation of the burial, cemetery moats (huanghao 隍濠 or weimugou 圍墓溝), and earthen tumuli not surmounted by shrines. In 1990 archaeologist Zhang Zhanmin 張占民 pushed further to the point that the First Emperor's mausoleum was exclusively from the Qin tradition. In order to fit earlier Qin royal tombs into this dualistic framework, he claimed that within the “Qin” tradition earlier “shrine tombs” had evolved to “tumulus tombs” by the late third century b.c.e.Footnote 50 With this assumed Qin-East dichotomy the First Emperor's tomb was claimed to be either “Qin” or “eastern,” or, a union of both traditions.Footnote 51

From a historical point of view, the assumption of cultural division between the Qin and all other states in the east might not have emerged until the Western Han dynasty, when divided intellectuals reflected on the dramatic rise and fall of the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–209 b.c.e).Footnote 52Yantie lun 鹽鐵論 (comp. 1st c. b.c.e.) described two opposite ideological camps in the Western Han court: the Confucian scholar officials (xianliang 賢良or wenxue 文學) and the bureaucrats (dafu 大夫 or yushi 御史), or, in Michael Loewe's words, the “reformist” versus the “modernist.”Footnote 53 The former camp identified itself with so-called East of the Passes (guandong 關東), the birthplace of Confucianism whose political doctrine embraced compassion (ren 仁) and ritual (li 禮); the latter was associated with the region called Inside the Passes (Guanzhong 關中), or, Qin, whose rulers believed in the effectiveness of strategies, law, and punishment in governing people.Footnote 54 Disagreeing on major socio-economic issues, the two camps fought each other to dominate the imperial policy-making. The political and ideological opposition between Guanzhong and Guandong (or Zhongyuan 中原) was further amplified by economic, cultural, customary, and dialectal differences between these two geographically separate areas.Footnote 55

Evidence from recent excavations, however, can hardly justify the dualistic discourse. A close comparison between the pre-imperial Qin mausoleums and other Eastern Zhou royal mausoleums of the eastern states reveals almost nothing uniquely “Qin.” Instead, the difference among the royal cemeteries at Fengxiang and at Lintong in Shaanxi and the recently discovered one at present-day Lixian in Gansu demonstrates that the Qin royal burial customs varied throughout the Eastern Zhou period without following a linear evolution. For example, the earliest of the three pre-imperial Qin royal cemeteries, conventionally called the Western Border Mausoleum (Xichui lingqu 西垂陵區) in the early Eastern Zhou period, featured earthen tumuli instead of freestanding shrines.Footnote 56 In the later Yongcheng royal cemetery during the fifth century b.c.e., however, tumuli disappeared while aboveground ritual buildings emerged above the burials.Footnote 57 But this new mortuary practice did not last for long. Only after a century, tumuli once again took over and replaced freestanding buildings in the Eastern Necropolis (Dongling 東陵) (Table 2).Footnote 58 Such back-and-forth shifting over time probably attests to the fact that rather than abiding by a tradition, the Qin kings were ready to embrace changes to meet their new demands or needs.

Table 2. Pre-imperial Qin mausoleums in Eastern Zhou in Comparison with Lishan Mausoleum of the First Emperor.

Besides tumuli, two other elements previously associated with the “Qin tradition” have been questioned by new archaeological discoveries.

Many scholars used to believe that cemetery moats bordering individual graves in a cemetery were a hallmark of the Qin funerary practice, whilst all royal tombs in eastern states were surrounded by walls rather than by moats.Footnote 59 But with similar cemetery moats discovered in late Eastern Zhou royal cemeteries of the Yue, Zhao, and Han states,Footnote 60 it is clear that such moats were not unique to Qin tombs.Footnote 61 Making the situation more complex, the recently published Qin royal mausoleum at Shenheyuan (dated late 3rd c. b.c.e.) boasted both a wall and a moat, indicating that the Qin funerary practice perhaps never really rejected the use of walls (Table 2).Footnote 62

The other element often attributed to the Qin funerary culture was the eastward orientation of tomb ramps, while the north-south orientation was considered characteristic of the “East.”Footnote 63 But two archaeological discoveries have repudiated this opinion. All large tombs in the royal cemetery of the Zhao state at Handan were oriented from the west to the east,Footnote 64 and the newly discovered Qin mausoleums I and II at Xianyangyuan in the late third century b.c.e. contained two great tombs whose longest ramps were oriented to the north rather than to the east.Footnote 65

The increasing number of such “exceptions” found in recent years has deepened doubts on the previously assumed norms exclusive to the “Qin” mausoleums during the late Eastern Zhou. Placing the tomb mound and even the entire mausoleum within certain conventions and traditions assumes that the First Emperor, the patron and ultimate endorser of the whole project, had a conventional and traditional mind. But perhaps no other personalities in Chinese history were more obsessed than the First Emperor by becoming unique and “first,” as is demonstrated below. For this reason, my interpretation of the tomb mound delves into its unique historical circumstances.

Imperializing the Tomb Mound

The fact that the First Emperor's tomb mound absorbed diverse elements from Eastern Zhou royal tombs can be interpreted in the historical context of China's unification into an empire.

The nine-stepped terraced wall, the temporary architecture simulation, and the outermost tumulus, which were not invented under the reign of the First Emperor, were in fact incorporated into one unity. Other old elements were also brought in, though not always in their previous places.

If Sima Qian was right, the outermost tumulus was once covered with grass and plants. The practice of greening a tumulus with vegetations (fengshu 封樹) was not invented in the Qin but already part of the Eastern Zhou funerary practice.Footnote 66 The ritual structures constructed around the mound were another old element. On the northern side of the imperial mound stands a nearly square architectural site 62 by 57 meters in area (see Fig. 1), whose plan closely resembles that of Cuo's offering hall measuring 52 by 52 meters.Footnote 67 The center of this site is an earthen foundation on which a ritual structure might have been erected. A gallery further surrounds the central ritual structure on all sides. This site has been identified as the “formal resting-chamber” (zhengqin 正寢), a ritual hall in which the deceased emperor or his soul could continue his ritual and ceremonial activities in the afterlife.Footnote 68 Duan Qingbo properly suggests that this building might have been a ritual equivalent of Cuo's offering shrine (see Figs. 3a, 3b).Footnote 69

To the north of the “formal resting-chamber” is another large complex of architectural remains, which have been identified as the “pastime palace” (biandian 便殿) for the deceased emperor to spend his leisure hours and enjoy entertainment (see Fig. 1).Footnote 70 Although Chinese traditional historiography considered such aboveground ritual complexes as an innovation under the First Emperor's reign,Footnote 71 the excavations of the Qin Eastern Necropolis at Lintong and the royal mausoleums of Zhao in Handan have both proved their earlier existence.Footnote 72 In both sites the excavators uncovered large aboveground architectural remains next to the tomb mounds, presumably as similar ritual facilities. There is little question that the ritual complex near the mound derived from Eastern Zhou prototypes.

Although the cemetery moat seems to be the only major traditional element absent from the First Emperor's mausoleum, archaeologist Zhu Sihong 朱思紅 made an interesting point, claiming that the moat was not really missing, but “upgraded” by full-scale rivers and waters running across the necropolis (see Fig. 1).Footnote 73

Despite all these and other borrowings related to the tomb mound, the First Emperor and his necropolis designer were not content with duplicating or copying what had existed before. The idiosyncrasy of this complex funerary structure lies precisely in the creative manner of combining or upgrading these various archetypes or models, which do not always fit coherently with one another, into a new unity. For example, the Qi and Chu “elevated” tombs, while boasting high tumuli, rarely included more than two levels of terraced walls, perhaps due to the fact that these walls would be eventually interred under the earthen heap and become invisible; the Zhongshan tombs, despite having much higher stepped walls, rejected tumuli, because the latter would have stood in the way of the former. The simulated galleries of Zhongshan, Yan, and Wei states were constructed in the shafts above the burial chamber, which were to be interred and become concealed from outside viewers; the real shrines of Qin, Wei, and Zhongshan stood above the ground to catch the attention of passers-by. How could all these heterogeneous and contradictory features coincide in a single tomb mound, with a high tumulus covered with vegetation, a high stepped wall with galleries, and a real freestanding offering shrine?

The designer of the Lishan necropolis came up with an ingenious solution. The nine-stepped terraced wall was turned into a full-scale building with real wooden structures built on the exterior steps near the top of the wall to increase visibility. Meanwhile, this spectacular building only existed as a temporary building to be interred under an even higher mound, which was later covered by trees and grass. In such an unconventional manner, the burial finally lay at once under both a terraced building and a tumulus, each with a compelling appearance. What's more, the permanent freestanding shrine was brought down onto the ground and relocated to the north of the mound. In doing so, the designer breached the norm that “shrine tombs” were structurally incompatible with “tumulus tombs” and united them in the ritual process of constructing and using the tomb. Before the tumulus came into being, the stepped terrace had stood freestanding and visible to the mourners. It seems that even the temporary existence of the practically useless galleries on the terraced wall was significant, for it enabled the new mound to combine almost all major elements—all in enlarged scales—of the previous Eastern Zhou royal mausoleums.

Absorbing nearly all major elements from Eastern Zhou royal mausoleums in an unprecedented manner, the First Emperor's monumental tomb mound is a visual and material representation of the First Emperor's political success in taking over and synthesizing elements once owned by his ancestors and previous political rivals in a great comprehensive plan (see Tables 1, 2). The creation of this hybrid mound and its affiliated structures, as is argued below, was part of the First Emperor's life-long political ambition: by incorporating the “World under Heaven” (bingjian tianxia 并兼天下) he strove for being the “first” (shi 始) in history.

According to Sima Qian, “When the First Emperor had just ascended the throne, he ordered his men to dig and construct the Mount Li [Mausoleum] 始皇初即位, 穿治驪山.”Footnote 74 In this passage Sima Qian narrated in a retrospective way, because the just enthroned fourteen-year-old boy was not yet the First Emperor (shihuang) but only a regional king of the Qin—one of the many competing political powers in China yet to be unified. Whereas Sima Qian barely talks about the early construction of the mausoleum during the first twenty-five years, he suddenly elaborates his description of the massive project with astonishing details after the unification of China in 221 b.c.e.:

及并天下,天下徒送詣七十餘萬人,穿三泉,下銅而致槨,宮觀百官司奇器珍怪徒藏滿之。令匠作机弩矢,有所穿近者辄射之。以水银为百川江河大海, 机相灌输。上具天文,下具地理。以人鱼膏为烛,度不滅者久之。

After [the First Emperor] had united the world, more than 700,000 convict laborers from the world were sent there. They dug through three [strata of] springs, poured in liquid bronze, and secured the sarcophagus. [Terra-cotta] houses, officials, unusual and valuable things were moved in to fill it. [It was] ordered that artisans should make crossbows triggered by mechanisms. Anyone passing before them would be shot immediately. They used mercury to create rivers, the Jiang, the He, and the great seas, wherein the mercury was circulated mechanically. On the ceiling were celestial bodies and on the ground geographical features. The candles were made of oil of dugong, which was not supposed to burn out for a long time.Footnote 75

It is clear in the text that the major construction work, including digging the tomb pit, constructing the casket, furnishing and decorating the burial, was all conducted after the king had declared himself emperor. Archaeological evidence has bolstered this view.Footnote 76 Since the construction of the necropolis continued almost throughout the emperor's (or the king's) reign, it is inconceivable that its major plan would have had conflicted with His Majesty's will.Footnote 77

Efforts were made so that the mausoleum would be worth the new imperial status never before existing in Chinese history. Whereas Eastern Zhou royal tombs used to be called ling 陵 (hill), the First Emperor's necropolis, distinctively, was designated shan 山 (mountain). The upgrade in terminology unambiguously elevates the tomb occupant above all previous kings.Footnote 78 Unlike the traditional collective necropolis shared by several generations of a royal lineage, the Lishan necropolis was designed and built for the First Emperor alone.Footnote 79 The exclusive ownership distinguished this ambitious conqueror from his father and grandfather by bestowing on him an unparalleled privilege no previous Qin kings had enjoyed.

Whilst all these new inventions were made to distinguish the First Emperor from his ancestors and his former defeated rivals, the First Emperor's tomb mound represents another way—a visual and material one—to legitimize his expansion and conquest: creating a new unity by incorporating the old elements. His obsession with merging past traditions was perhaps best illustrated by the birth of his new imperial title, “The August Thearch” (Huangdi 皇帝).

In Sima Qian's account the new imperial designation was coined by the First Emperor himself. When the ministers were preparing an honorific title for the emperor, they consulted all available ancient titles, among which they thoughtfully chose the single most esteemed one— “Primeval August” (Taihuang 泰皇). Their memorial specifies the reasoning behind this proposal:

昔者五帝地方千里,其外侯服夷服諸侯或朝或否,天子不能制。今陛下興義兵,誅殘賊,平定天下,海內為郡縣,法令由一統,自上古以來未嘗有,五帝所不及。臣等謹與博士議曰:古有天皇,有地皇,有泰皇,泰皇最貴。臣等昧死上尊號,王為“泰皇” 。

In the past, the territory of the Five Emperors was one-thousand li [on a side]. Beyond this were the warning domain and the barbarian domain. The feudal lords sometimes came to court and sometimes did not, and the Son of Heaven was not able to control them. Now Your Majesty has raised a righteous army to punish the savage and the villainous and has pacified the world. The land within the seas has been made into commanderies and counties, the laws and ordinances are ruled by one. Since antiquity it has never been so. This is what [even] the Five Emperors could not reach. Having attentively deliberated with the Erudites [concerning your designation] we propose: ‘In antiquity, there were The Heavenly August, The Earthly August, and The Primeval August. The Primeval August was the most honored. We risk a capital offense to offer the most honored designations, the king is to be called “The Primeval August.”Footnote 80

But this seemingly perfect proposal was rejected by the emperor, who, enthralled by a better idea, replied:

王曰: “去‘泰’,著‘皇’,采上古‘帝’位號,號曰‘皇帝’”。

Delete “Primeval,” keep “August,” and make use of the title of antiquity, “The August Thearch.”Footnote 81

This historical episode, if credible, betrays two different ways of thinking between the emperor and his ministers in understanding the relationship between emperorship and the previous kingship. Whereas the ministers chose one best out of many candidates, the emperor merged all candidates into an ingenious compound, for even the most honorific title (Taihuang) failed to satiate his ego. By merging the two titles Huang and Di, he refused to identify himself with any of the earlier individual rulers but impersonated all of them in an innovative synthetic form.

The idea of incorporation (bingjian 并兼) is bluntly stated in a well-known edict inscribed on an imperial bronze measure, whose numerous copies were distributed throughout the empire:

廿六年,皇帝盡并兼天下諸侯, 黔首大安,立號為皇帝。

In the twenty-sixth year the August-Thearch merged all the principalities under heaven. The Black Heads (all the people) enjoyed great peace. The title “The August Thearch” was claimed.Footnote 82

In an effort to lower the geographic or cultural profile of Qin as the alien conqueror, the First Emperor instead of naming his imperial subjects “Peoples of the Qin” chose an entirely neutral designation—“Black Heads” (qianshou 黔首) to show “the whole world as one family” (tianxia yijia 天下一家).Footnote 83 In a number of stone inscriptions the emperor made in several sites during his inspectional tours to the conquered eastern provinces, rather than boasting the sole power of Qin or mystifying the Qin royal lineage, the texts put emphasis on the emperor's merit of ending the civil war and bringing peace and welfare equally to all the people under heaven.Footnote 84 To the new emperor, the vast conquered lands in his east provinces were no longer war booties he seized from crushed enemies, but part of his own legitimately united empire in a new era that was expected to last for ten thousand generations.

Conclusion

Back in its day, the First Emperor's tomb mound, perhaps the best-known one ever built in China, was both old and new. It was old because all its major components—terraced wall, simulated building, tumulus, grass and trees, offering hall, pastime-palace, walls, waterways, etc.—derived from the earlier Eastern Zhou royal tombs; it was new because the creative way in which these components were put together gave rise to an unprecedented synthesis. In this sense it might be more appropriate to compare this mound to a masterpiece of art, though the master remains unknown.

The innovative synthesis of the tomb mound defies the conventional typological classification of “tumulus tombs” and “shrine tombs.” It also challenges the conventional wisdom of two assumed opposite cultural traditions: “Qin” versus “East.” The real meaning of this creative work, as I have demonstrated, was concealed in its particular historical context, i.e. China's first unification under a bureaucratic government masterminded by an ambitious historical personality. The First Emperor's distinct manner of synthesizing multiple elements from earlier royal mausoleums speaks of his interest in crafting a new era through creatively incorporating (bingjian) various old elements. By doing so the imperial tomb mound became a monument, a symbolic image of the empire and its founder, whose political will, power, and imagination is embodied forever in the multiple layers of the mound, which still inspires awe and imagination in viewers of the modern day.