How parties of the right represent women voters is a puzzle with many moving parts. A convincing account must include the three key elements of political representation in party democracies: the ideology and behavior of parties, their representatives, and their voters. It is unlikely that any single piece of research could credibly capture all of these elements together, but cumulatively, the articles in this special issue seek a holistic description. In our contribution, we isolate two components of the political representation triad (Norton and Wood Reference Norton and Wood1993); party (ideology) and voter (behavior).

Analysis of the linkages between these two constituents requires the integration of several disparate but related literatures. The expanding research on party behavior and debates concerning the extent to which parties of the right can ever truly represent the “interests of women” (Celis and Childs Reference Celis and Childs2012, Reference Celis and Childs2014; Celis et al. Reference Celis, Childs, Kantola and Krook2014) are related, if often only implicitly, with the literature concerning the presence or absence of a demand by parties of the right for women's votes. The literature that focuses specifically on gender and voting for parties of the right largely seeks to understand why the increasing support for populist radical right parties, mainly in Europe,Footnote 1 is driven more by men than by women (e.g., Akkerman, de Lange, and Rooduijn Reference Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016; Harteveld et al. Reference Harteveld, Van Der Brug, Dahlberg and Kokkonen2015; Spierings and Zaslove Reference Spierings and Zaslove2015, Reference Spierings and Zaslove2017). Alongside this literature is a vast body of research on the “modern gender gap” that seeks to explain women's movement to support parties of the left in many Western democracies but also explores why women have historically supported parties of the right in greater numbers than men and whether they continue to do so in more traditional societies.

In this article, we attempt to combine these approaches by conducting a two-stage exploratory analysis using expert and voter survey data. First, we map the ideological positions of parties of the right in terms of gender ideology across Western Europe to establish the extent to which there is a common approach to gender equality or a common theme in the way parties of the right seek to represent the interests of women. Second, we explore whether rightist parties differ in their ability to recruit women's votes.

PARTY IDEOLOGY

The assumption that the representation of women was the task of leftist parties was implicit within much gender and politics scholarship (Celis and Childs Reference Celis and Childs2012, Reference Celis and Childs2014). In fact and to a large extent, feminist thought operated on the basis that conservatism and feminism were mutually exclusive (Erzeel, Celis, and Caluwaerts Reference Erzeel, Celis, Caluwaerts, Celis and Childs2014). Certainly research shows that rightist parties more often than leftist parties make antifeminist claims (Celis Reference Celis2006; Erzeel, Celis, and Caluwaerts Reference Erzeel, Celis, Caluwaerts, Celis and Childs2014; Lovenduski and Norris Reference Lovenduski and Norris2003; Wängnerud Reference Wängnerud2000), but there is evidence that some rightist parties (particularly in the United Kingdom and Germany) advocate feminist ideas at least on some occasions (Erzeel and Celis Reference Erzeel and Celis2016). Karen Celis and Sarah Childs (Reference Celis and Childs2014) explore whether nonfeminist claims to represent women—that is, attempts to promote traditional gender roles—might still be defined as substantively representing women if identifiable groups of women support these policies and, as such, Celis and Childs disavow a feminist application of a theory of false consciousness. However, even if the assumption that the substantive representation of women requires challenging traditional roles is retained, it is not obvious that rightist parties will inevitably espouse antifeminist ideologies. Here we undertake an empirical investigation of the extent to which rightist parties represent feminist ideology and whether this varies across mainstream rightist parties and parties of the populist radical right in Western Europe.

In order to unpack how such parties might seek to represent women voters, we need to define the varieties of rightist ideology that parties espouse and how these ideologies in turn impact (1) the amount of attention parties give to gender issues and (2) in what direction (feminist or other). Celis and Childs (Reference Celis and Childs2014, 7) outline how differences in rightist thought have varying implications for the representation of women; they differentiate between social/moral conservatism and economic liberalism/conservatism and argue that morally conservative rightist parties are likely to espouse a more traditional view of gender roles than rightist liberal parties. In the same vein, Erzeel and Celis (Reference Erzeel and Celis2016) find that rightist parties’ positioning on postmaterialist issues is a far better predictor of the amount of attention they give to gender issues than their stance on socioeconomic issues because gender equality concerns fit within a larger package of postmaterialist issues that appeared on the political agenda in the 1970s (see also Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2003). Furthermore, various contributions to this special issue describe varieties of conservatism and suggest that all can be present in one rightist party (such as the Republican party in the United States), or they might be more diffused across a number of parties in a multiparty system (e.g., in the Netherlands the Christian Democratic Appeal [CDA] might be described as morally conservative, the People's Party for Freedom and Democracy [VVD] as liberal conservative, and the Party for Freedom [PVV] as nationalist conservative). Thus, there is a potential relationship between varieties of conservatism and gender ideology whereby parties of the right might vary in their attitudes toward gender equality. Parties’ gender ideologies are likely to vary according to their economic, moral, and populist ideologies; in the first half of the empirical analysis in this article, we attempt to map the extent to which this is the case in Western Europe.

VOTING BEHAVIOR

Studies of the “Gender Gap”

Early studies of “gender”Footnote 2 and voting behavior, such as Herbert Tingsten's (Reference Tingsten1937) Political Behavior and Maurice Duverger's (Reference Duverger1955) The Political Role of Women, concluded that women were more likely to support rightist parties than men. This trend is often described as the traditional gender gap (à la Norris Reference Norris, Evans and Norris1999). However, since the emergence of the high-profile “modern” gender gap in U.S. presidential elections in the 1980s (when more women than men supported the Democratic candidate), the emphasis has shifted from explaining women's support for parties of the right to their support for parties of the left. Early studies of the modern gender gap in the United States gave serious attention to political explanations for gender differences in vote choice (Bonk Reference Bonk and Mueller1988; Mueller Reference Mueller and Mueller1988a, Reference Mueller1988b), but subsequent gender gap literature has focused largely on sociological accounts (notable exceptions include Immerzeel, Coffé, and Van der Lippe Reference Immerzeel, Coffé and van der Lippe2015; Spierings and Zaslove Reference Spierings and Zaslove2015). We argue that the emphasis on sociological factors in studies of the gender gap has led researchers to overlook ideological differences between the parties that might help explain why some parties of the right remain attractive to women while others do not. Recent studies of the populist radical right have brought the political dimension back in, but as yet these insights have only rarely been applied to gender gaps in voting behavior more broadly.

By far the most influential theoretical account of gender and voting in global perspective has been Inglehart and Norris's (Reference Inglehart and Norris2000) global gender gap thesis. They argue that as women have shifted from domestic life into higher education and paid employment, their political preferences have moved from an emphasis on traditional values to a demand for more state support for combining work and family life—in the form of social spending on welfare, child care, and education—which has driven them away from supporting parties of the right. Inglehart and Norris's thesis is an important and valuable contribution to our understanding of the impact of gender on voting behavior in international perspective, but to some extent, it sidesteps the issue of party politics. Inglehart and Norris use a straightforward left-right classification of parties to assess the extent to which women in “traditional societies” (those in which women are not well represented in higher education and paid employment) vote to the right of men and in “modern societies” (in which there has been a transformation in gender roles) women vote to the left of men. There are various anomalies that do not fit within the global gender gap narrative—although Inglehart and Norris do find a large number of cases that are in keeping with the expectations of the theoretical model—and we question whether these anomalies might be accounted for by drawing party behavior, particularly ideology, back into accounts of why women might choose to support parties of the right.

It is now well established that there is substantial variation in the gender gap in party support across the globe and within the European Union (Abendschön and Steinmetz Reference Abendschön and Steinmetz2014; Giger Reference Giger2009; Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2000). Attempts to explain this variation have found mixed results, with the impact of individual-level and structural factors fluctuating, apparently erratically, from context to context (Immerzeel, Coffé, and Van der Lippe Reference Immerzeel, Coffé and van der Lippe2015). We hypothesize that the seemingly inexplicable shifting in the power of explanatory factors might be explained by the mediating role of variations in party ideology, with this impacting women's support for parties of the right (Campbell Reference Campbell2016). The immense transformation of gender roles in Western democracies likely provides the most solid foundation for understanding changes in women's political preferences, but how these preferences translate into party support or voting behavior has been, we contend, undertheorized (Campbell Reference Campbell2016; Gillion, Ladd, and Meredith Reference Gillion, Ladd and Meredith2014). Accordingly, we explore in the second half of the empirical analysis whether variations in the political ideologies of parties of the right can help explain gender variations in support for these parties across Western Europe.

Studies of the Populist Radical Right (PRR)

One of the most consistent findings in studies of the populist radical right (PRR) is that these parties tend to gain a disproportionate share of their support from men (Arzheimer and Carter Reference Arzheimer and Carter2006; Betz Reference Betz1993; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1997; Lubbers, Gijsberts, and Scheepers Reference Lubbers, Gijsberts and Scheepers2002; Norris Reference Norris2005). However, we should note that the extent of the gender gap in support for PRR parties varies considerably and is sometimes overstated (Mayer Reference Mayer2015; Spierings and Zaslove Reference Spierings and Zaslove2015, Reference Spierings and Zaslove2017). The literature has principally attempted to explain gender differences in support for PRR parties by drawing on structural explanations for the sociological bases of PRR support. A structural account emphasizes the fact that working-class men are disproportionately among the losers in the postindustrial nation states of contemporary Europe and therefore are more likely to be drawn to PRR parties than women. There are many more men among blue-collar workers, whose financial prospects have diminished as a result of the shift from manual to service sector employment, than women, who are more often employed in the service sector (Ford and Goodwin Reference Ford and Goodwin2014).

If structural differences in men and women's employment do in fact account for the gender gap in support for radical right parties, then we would expect the gender gap to disappear when measures of employment type are included in analyses. However, Terri Givens argues that the gender gap in votes for the radical right cannot be simply explained away by controlling for structural factors (Givens Reference Givens2004); she identifies considerable variation by country, finding only a negligible gender gap in Denmark compared with a much larger gap in France and Norway. In their study of 12 nations, Immerzeel, Coffé, and Van der Lippe (Reference Immerzeel, Coffé and van der Lippe2015) also find considerable variation in the radical right gender gap by country and the extent to which individual-level (structural explanations) or contextual-level (political explanations) help explain the variations in the gender gap. Immerzeel, Coffé, and Van der Lippe utilize contextual-level factors such as the age and popularity of the party and its outsider status in their analysis. In a similar vein, Mudde (Reference Mudde2007) argues that women, because they have lower levels of political efficacy, are less likely to vote for new or radical parties. We hypothesize that party gender ideology is also likely to be a crucial factor for explaining gender differences in support for parties of the PRR; we expect parties that adopt more traditional gender ideologies to secure proportionately fewer votes from women than parties that adopt feminist gender ideologies.

The lack of systematic analysis of the link between structural explanations (demand-side accounts) and political explanations such as the ideological positioning of parties and the behavior of their leadership (supply-side accounts) is addressed in the special issue on gender and populist radical-right politics of Patterns of Prejudice (Spierings et al. Reference Spierings, Zaslove, Mügge and de Lange2015). The authors question whether gender plays a significant part in the platforms of PRR parties and whether this has changed over time. Historically, parties on the populist radical right have been associated with traditional attitudes to gender roles as a result of a nativist emphasis on the role of women as mothers. However, in the post-9/11 era, there has been a shift in the discourse of much of the PRR, particularly in Northern Europe, to a focus on Islamophobia and the portrayal of Muslim immigrants as a threat to liberal values, including gender equality (Akkerman Reference Akkerman2015; de Lange and Mügge Reference de Lange and Mügge2015). Therefore, we might expect there to be increasing variation in the gender ideology of PRR parties, and some may in fact espouse positions on gender equality that are equally or even more feminist than more mainstream rightist parties.

Sarah de Lange and Liza Mügge (Reference de Lange and Mügge2015, 19) argue that political scientists have underestimated the variation in the gender ideologies of PRR parties: they find that not only neoliberal PRR but also some nationalist populist parties adopt modern views on gender equality. Here, we extend de Lange and Mügge's study of the Netherlands and Flanders and map the gender ideologies of mainstream rightist and PRR parties across 13 Western European nations to establish whether PRR parties are more traditional in their attitudes to gender equality compared with mainstream rightist parties.

Moreover, the literature on the PRR has operated largely as though support for these parties is deviant. Yet recent studies argue that this may be mistaken and that the explanations for the gender gap in support of the PRR mirror support for rightist parties more generally (Spierings and Zaslove Reference Spierings and Zaslove2015). If this analysis is correct, then the sources of the modern gender gap ought to explain the PRR gender gap equally well. Therefore, we explore whether gender differences in support for parties of the right apply across both mainstream rightist parties and PRR parties or whether there is a split, with parties of the PRR being particularly attractive to men.

METHOD

Measuring Ideology

Ideologies are belief systems that are shared by members of a particular group (Van Dijk Reference Van Dijk2006, 116). Variations in political ideology will only lead to gender gaps in party support if, on average, men and women hold different ideological positions. However, we know from the extensive gender gap literature that there have been fairly consistent gender differences in ideology across time and place. For example, Gillion, Ladd, and Meredith (Reference Gillion, Ladd and Meredith2014) contend that party ideological polarization provides a more persuasive account of the emergence of the modern gender gap in the United States (where more women than men support Democratic Party candidates) than either the gender realignment thesis or other accounts that focus on women's changing position in society. They argue that because gender differences in political attitudes and preferences predate the gender gap and have remained relatively stable, they are unlikely drivers of the variation in the gender gap. They find that in the United States, policy preferences have become more closely associated with partisanship over time; this suggests that the gender gap in party support is driven by party polarization in ideology.

In this article, we attempt to operationalize political ideology in a comparative study of Western European democracies, not using respondents’ own assessments of party ideology (à la Gillion, Ladd, and Meredith Reference Gillion, Ladd and Meredith2014) but using external measures of party ideology collected from expert surveys. The use of external measures of ideology allows us to avoid endogeneity problems that may occur should respondents to voter surveys retrospectively align their policy preferences, judgments of party positions and vote choice and is thus is a complement to Gillion, Ladd, and Meredith's innovative approach.

Our measures of party ideology include socialist/laissez-faire (economic), GAL/TAN (green/alternative/libertarian versus traditional/authoritarian/nationalist) (Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, de Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2015), and traditional/feminist attitudes toward gender roles (gender) ideologies. Economic and moral ideologies have wide resonance, which might help explain the attitudes of the majority of the population. Gender ideology, on the other hand, is likely to be highly salient to a subset of the population who espouses a feminist gender ideology.Footnote 3 We include measures of economic and moral ideology because of their salience in the gender gap literature and within the literature on rightist parties’ representation of women. Both literatures suggest that left-leaning economic ideology is likely to be associated with women's support for parties of the left, but a right-leaning moral ideology is likely to be associated with support for traditional gender roles.

Expert Survey

There are multiple possible methods for assessing the positions parties take in ideological space, including analysis of manifestos, roll-call voting, television debates, leaders’ speeches, voter evaluations, and expert judgments (Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, de Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2015). Making use of expert judgments by conducting an expert survey is an efficient means for gathering data on a large number of parties that is not dependent on the variation in quality of either party manifestos, their representation in legislatures, or voter knowledge (Benoit and Laver Reference Benoit and Laver2006; Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Bakker, Brigevich, de Vries, Edwards, Marks, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2010; Rohrschneider and Whitefield Reference Rohrschneider and Whitefield2009). Furthermore, there is a lack of high-quality comparative data on parties’ positions on gender equality. The comparative manifestos project includes a measure of family values and one on “equality,” but neither measures gender equality per se. The family values item is very general and measures moral conservatism rather than feminist values. The equality item measures equality in general and the protection of “underprivileged groups” but, again, not gender equality specifically.

The use of an expert survey is a good alternative to manifesto data in the context of this exploratory study. Peter Mair describes the results of expert surveys as a synthesis of parties’ past behavior, policy programs, ideologies, and elite and mass assessments filtered through the perceptions of the expert; as such, he considers expert surveys to provide a quick and relatively easy short cut for gathering party position data (Mair Reference Mair and Laver2001). One of the potential weaknesses of expert surveys described by Mair is the difficulty experts face when locating parties on policy domains that are not particularly salient for that party. While this is a potential criticism of expert surveys with a broad remit, we believe it to be an argument in support of their use in the case of attempting to measure parties’ positions on gender equality.

In the main, gender equality is not one of the most critical axes used to describe party competition in the study of comparative politics. Therefore, attitudes toward gender equality represent just the kind of auxiliary axis that might be miscoded in a general expert survey and warrant a separate set of expert judgments from gender and politics scholars. Gender and politics is a subfield of political science, and as such, there are fewer gender and party politics scholars available to participate in an expert survey, with rich country knowledge, than would exist for a more general survey. Therefore, we rely on smaller sample sizes than is ideally described in the expert survey literature. However, the debate in the expert survey literature also suggests that expert surveys are less reliable when experts are not confident in their judgments, which leads to seemingly random fluctuation in scores. Therefore, we argue that relying on the expert judgment of a smaller number of confident experts is likely to produce more reliable results than expanding the data collection exercise.

We utilize data from an original expert survey of gender and politics scholars in order to capture the parties’ positions on gender equality and add it to publicly available data from the 2014 Chapel Hill expert survey (Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, de Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2015) on socialist/laissez-faire and liberal/authoritarian ideology. Future research should collate information on party position from a range of sources to test whether the findings from the gender expert survey can be replicated.

For our gender and politics expert survey, we compiled a master list of 173 experts in gender and politics in 15 Western European countries (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom).Footnote 4 We included experts in our list if they had published on gender and party politics in the specified country or if they had been recommended to us by experts in the field. In total, 83 (48%) experts participated in the survey, giving us an average number of five respondents per country (the country coverage is set out in Table 1). We set a minimum number of experts of three per country; this is two fewer than recommended in the expert survey literature (Huber and Inglehart Reference Huber and Inglehart1995), but doing so allowed us to retain France and PortugalFootnote 5 in the analysis, which we felt was critical to maintain good country coverage. In this article, however, we do not include Norway and Switzerland because these countries were not included in the European Election Study (see the following section).

Table 1. Experts and political parties included in the survey

In order to maximize response rates, we kept our survey to just four items.Footnote 6 The first three items measure the parties’ positions on gender equality, and the fourth item asks respondents to place the parties on a general left-right scale. In order to ensure that all of the experts employed the same political party concept, we asked them to “reflect on the general position of the national leadership of the parties, not on the position of the party base or local parties” (Budge Reference Budge2000; Steenbergen and Marks Reference Steenbergen and Marks2007). The survey elicited contemporaneous judgments of party positions to avoid the difficulties associated with asking survey respondents to make retrospective judgments (Steenbergen and Marks Reference Steenbergen and Marks2007, 349).

Each party included in the survey was categorized as either “left” or “right” based on the party's European Parliament political group affiliation. Parties belonging to the “Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament,” the “Confederal Group of the European United Left—Nordic Green Left,” and the “Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance” were categorized as “left,” and parties belonging to other political groups were categorized as “right.” Within the group of rightist parties, we make an additional distinction between “populist” and “nonpopulist” parties. The classification of rightist populist parties is based on Mudde (Reference Mudde2013) and includes the following parties: Austrian Freedom Party (Austria), Alliance for the Future of Austria (Austria), Flemish Interest (Belgium), Danish People's Party (Denmark), National Front (France), Northern League (Italy), Party for Freedom (Netherlands), Sweden Democrats (Sweden), and British National Party (Great Britain). In addition, we consider the True Finns (Finland) a populist party (Spierings and Zaslove, Reference Spierings and Zaslove2017; Van Kessel Reference Van Kessel2015). Nonpopulist parties include, among others, Christian democratic, conservative, and liberal parties.

In order to measure the economic and moral ideological positions of parties in more detail, we use publicly available data from the 2014 Chapel Hill expert survey (Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, de Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2015). Economic ideology classifies parties based on whether “parties want government to play an active role in the economy” (left) or “parties emphasize a reduced economic role for government: privatization, lower taxes, less regulation, less government spending, and a leaner welfare state” (right). Moral ideology classifies parties based on whether they “favour expanded personal freedoms, for example, access to abortion, active euthanasia, same-sex marriage, or greater democratic participation” (libertarian) or whether they “reject these ideas, they value order, tradition, and stability, and believe that the government should be a firm moral authority on social and cultural issues” (authoritarian) (Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, de Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2015, 144). For each question, country experts positioned parties on a 11-point left-right scale with 0 implying a left/libertarian position, 5 a center position, and 10 a right/authoritarian position.

Voter Survey

In the final part of the empirical analysis, information on party and gender ideology from the expert survey is linked to voting behavior. In order to measure voting behavior, we use data from the 2014 European Election Study (EES) (Schmitt et al. Reference Schmitt, Hobolt, Popa and Teperoglou2015). The EES survey is a postelection survey that includes representative national samples of the population (aged 18 or olderFootnote 7 ) in all European Union member states. The EES data are very useful for this particular study because the data were collected in May and June 2014.Footnote 8 This timing was close to that of the gender expert survey in 2015, which maximizes the comparability of the data and parties across the two surveys. The EES uses a standardized questionnaire that was identical in the various member states (albeit translated to the appropriate national language). The sample size in each country is approximately 1,100 interviews. In this article, we focus only on the 13 West European countries that are also covered in the gender expert survey.Footnote 9 Response rates in the countries under study range between 38% (Netherlands) and 84% (Portugal) (Schmitt et al. Reference Schmitt, Hobolt, Popa and Teperoglou2015; see Appendix A in the supplementary material online for response rates for all countries).Footnote 10

The EES includes different vote choice variables. Here, we use the following question/variable on voting intentions: “If there were a general election tomorrow, which party would you vote for?” We use a question on future voting intentions rather than past voting behavior because in some countries the last parliamentary elections took place well before 2014. Asking participants to recall past voting behavior is always delicate. In order not to jeopardize the validity of the results, we decided to focus on vote intentions, which were measured at the same point in time for all countries (Ferrín, Fraile, and García-Albacete Reference Ferrín, Fraile and García-Albacete2017).Footnote 11 The models predict party choice, with voters’ gender as the only independent variable. In each model, a number of control variables are added that might influence party choice, including respondents’ marital status (dummy married/nonmarried), employment (dummy paid employment/no paid employment), age (categorical, 16/18–39, 40–54, 55+), political efficacy (scale 1–4, with high levels showing low efficacyFootnote 12 ), and political interest (scale 1–4, with high levels showing low interestFootnote 13 ).

ANALYSIS

Part I: Mapping the Ideological Positions of Parties of the Right on Gender Ideology across Western Europe

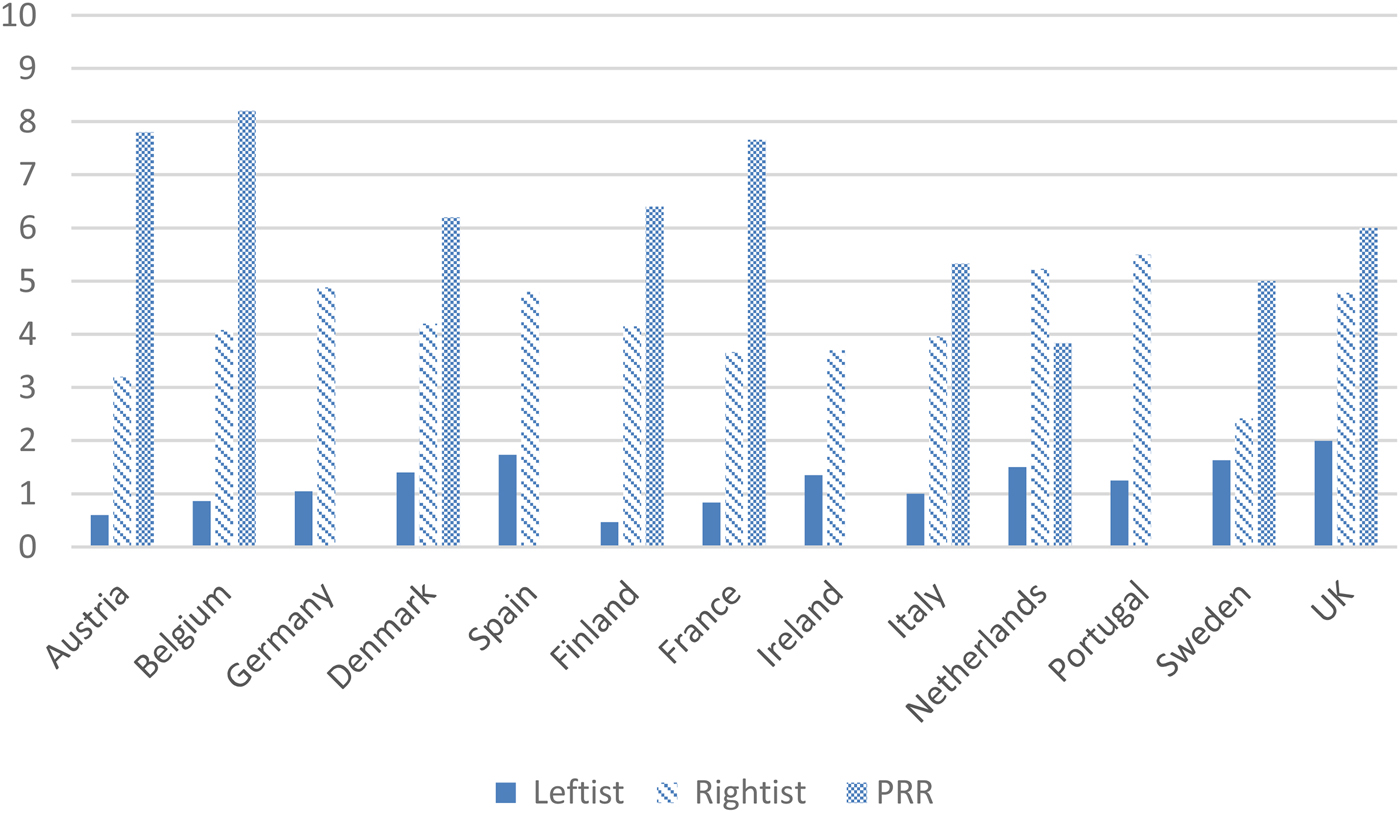

Figure 1 shows the mean gender role ideology scores of rightist, PRR, and leftist parties across the 13 countries in our analysis. Our gender equality experts were asked to place the parties on a 0–10 scale, where 0 represents the view that “women should have an equal role with men in running business, industry, and government” and 10 the view that “a woman's place is in the home.”

Figure 1. Mean gender ideology of rightist, PRR, and leftist parties in Europe. Gender ideology is measured on an 11-point scale, with 0 indicating a feminist gender ideology and 10 indicating a traditional gender ideology.

There is a great deal of variation in the gender ideologies espoused by parties of the right in Western Europe. In fact, the mean for rightist parties was below 5, showing that the parties were, on average, judged slightly more feminist than traditional in their gender role ideologies, and the mean score for PRR parties was 6, slightly more traditional than feminist on average. For leftist parties, the mean was 1, indicating that, on average, our experts rated leftist parties as highly feminist. Among rightist parties, the lowest score was 0 and the highest was 10, demonstrating that parties of the right in Europe can be classified across the full spectrum of gender role ideology. Thus, we cannot see a single narrative whereby parties of the right adopt antifeminist gender ideologies.

Given the spread of gender ideology among rightist parties, it is conceivable that variations in gender gaps in support for parties of the right might be explained by variations in party ideology. The PRR parties with the most traditional gender role ideologies were found in Belgium, Germany, Austria, and France—all with means above 7. The only country with a PRR party with a feminist gender ideology score (i.e., below 5) was the Netherlands, and in Sweden, the mean was 5, indicating a neutral (neither feminist nor traditional gender ideology). This is in keeping with the PRR literature, which identifies a shift in the narrative in Northern Europe that deliberately conflates anti-immigrant/anti-Muslim sentiment with feminism (Meret and Siim Reference Meret, Siim, Siim and Mokre2013).Footnote 14

Figure 2 shows the correlation between gender ideology, economic ideology, and liberal/authoritarian ideology (measured using GAL/TAN). It is clear that there is a closer relationship between liberal/authoritarian ideology and gender ideology (Pearson's R of .846**) than between economic and gender ideology (Pearson's R of .572**); this relationship is to be expected given the association between authoritarian attitudes and attitudes toward gender roles, which are both strongly related to religiosity. It is clear from Figure 2 that there is a distinctive pattern, with parties of the left espousing more liberal and feminist ideologies than parties of the right, and that parties of the PRR are predominantly found in the top right-hand corner (the most authoritarian and least feminist). Even so, there is considerable variation within party types, with a good number of mainstream parties of the right occupying the same ideological space on gender equality and liberalism as leftist parties. These data provide evidence that although the general trend for leftist parties to be more feminist and liberal than parties of the right remains, there is considerable competition between parties of the left and right in this ideological space. On this basis, we suggest that this constitutes evidence of attempts by some rightist parties to represent feminist women with feminist policies.

Figure 2. Correlations between gender ideology and economic versus liberal/authoritarian (GAL/TAN) ideology.

The relationship between economic ideology and gender ideology is considerably weaker. There are a large number of parties of the mainstream right that espouse both a feminist gender ideology and rightist economic positions; this provides us with evidence of how a feminist gender ideology can be accommodated by laissez-faire economic ideology, as discussed in the introduction to this article. The extent to which these parties are willing to deploy the apparatus of the state to transform gender roles is not evident here, but we can see that feminism and conservatism are not mutually exclusive at least in terms of rhetorical commitment.

Thus far, we have described patterns in parties’ ideologies without attempting to develop explanatory accounts of the data. In order to begin to see how different party ideologies structure gender ideology, we conduct a (limited) linear regression in Table 2. Because of the small number of cases, the number of independent variables is limited to three: economic socialist/laissez-faire ideology, liberal/authoritarian ideology, and a dummy distinguishing between populist and nonpopulist parties. Again, the analysis confirms that rightist parties’ liberal/authoritarian ideology is a stronger predictor for the gender ideology of parties than their economic ideology. Only the parameter for liberal/authoritarian ideology displays a significant effect, showing that parties become more traditional in their gender stance when they adopt a more authoritarian ideology. On the other hand, parties’ economic ideology no longer shapes their gender ideology after controlling for the other variables. It is parties’ stance on moral issues and not parties’ economic ideology that structures their gender ideology.

Table 2. Ordinary least squares regression of gender ideology of rightist parties

Notes: The B-coefficients are unstandardized coefficients. *** p < .001; + p < .1. VIF scores range from 1.211 to 1.67, indicating that multicollinearity is not a problem in either model.

Part II: Do Parties of the Right Differ in Their Ability to Recruit Women Voters?

The second part of the empirical analysis connects data on party ideology and gender ideology to data on voting behavior. The goal is to see whether parties, and rightist parties in particular, differ in their ability to attract the electoral support of women voters.

Figure 3 shows a histogram of the percentages of women voters in the electorate of leftist and rightist parties using data on party choice from the EES.Footnote 15 Overall, the mean percentage of women voters in the electorate of leftist parties (mean score of 49.4% female voters) is very similar to that of rightist parties (mean score of 48.5% female voters). A country-by-country comparison (not shown here) also revealed that left/right differences in female vote support are absent in most countries. Differences are the largest in Denmark, where left parties have an average 57% of female voters and right parties 43.4%, but these differences are not statistically significant. Hence, rightist parties are not any different from leftist parties when it comes to their ability to recruit female voters. Moreover, the fact that the percentage of women voters for rightist parties fluctuates from 27.3% to 75% indicates that the electoral success of at least some rightist parties depends heavily on the electoral support of women.

Figure 3. Percentage of women in the electorate of leftist and rightist parties. For leftist parties: N = 44, mean = 49.4, standard deviation = 8.6, min. = 25, max. = 69.4. For rightist parties: N = 49, mean = 48.5, standard deviation = 11; min. = 27.3, max. = 75.

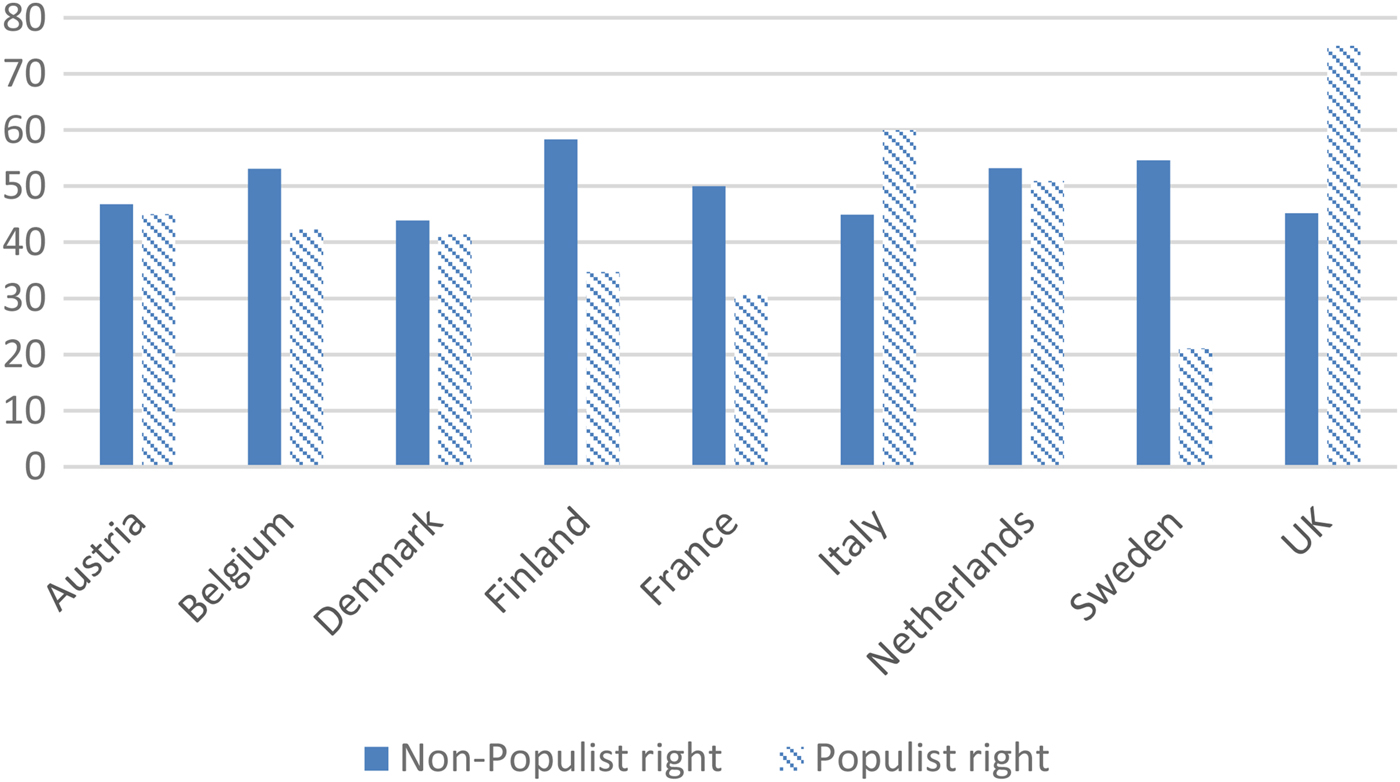

Next, we disaggregate the results. Figure 4 compares the percentage of women voters in the electorate of the populist right and the nonpopulist right. In most countries—except Italy and the United KingdomFootnote 16 —the percentage of women voters is higher among nonpopulist than among populist right parties, confirming the populist radical right gender gap. Especially in Sweden, France, and Finland, women form a minority of the populist right electorate (corresponding with 21.1%, 30.6%, 32.4%,, and 34.7% of women voters respectively). But in Austria and the Netherlands, the populist electorate is more gender balanced. These findings confirm recent studies suggesting that the gender gap in populist radical right voting is not universal (Spierings and Zaslove Reference Spierings and Zaslove2015) and/or might be closing over time (Mayer Reference Harteveld, Van Der Brug, Dahlberg and Kokkonen2015).

Figure 4. Percentage of women in the electorate of populist versus nonpopulist right parties. The number of respondents who supported the PRR was fewer than 50 in Belgium, Italy, and the United Kingdom.

In order to understand variation in the electoral support rightist parties receive from women, it is important to look not only at differences between populist and nonpopulist parties. The role of gender ideology should also be addressed. In order to do so, we estimate a model of vote choice in Table 3. Given the diversity in parties within one country and the differences in parties between countries, we are unable to use “party choice” as the outcome variable. Therefore, we opted to create a categorical variable as our outcome variable. The outcome variable groups parties according to their party ideology (left/right) and gender ideology (feminist/traditionalFootnote 17 ), thus distinguishing between (1) left parties with feminist gender ideologies, (2) left parties with traditional gender ideologies, (3) right parties with feminist gender ideologies, and (4) right parties with traditional gender ideologies. The second category (left parties with traditional gender ideologies) is empty and therefore is not included in Table 3. The reference category is right parties with traditional gender ideologies. Voters’ gender is the independent variable in the model, so we assess the extent to which voters’ gender influences the probability that a voter votes for a party in one of the categories of the dependent variables. We control for respondents’ marital status, paid employment, age, political efficacy, and political interest. In order to control for institutional variation between countries, we added country fixed effects.

Table 3. Multinomial logistic regression predicting party choice by gender ideology

Notes: The model is a fixed-effects model with country dummies. Reference category is “vote for right party with traditional gender ideology.” The fourth category, “vote for left party with traditional gender ideology,” remains empty and therefore is not included in the table. The B-coefficients are unstandardized coefficients. *** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05.

Table 3 predicts voters’ choice for a right party with a traditional gender ideology. The results indicate that, after controlling for third variables, the “gender” variable remains statistically significant for both outcome categories. Women are more likely than men to vote for a left party with a feminist gender ideology compared with a right party with a traditional gender ideology. A calculation of the odds ratio (Exp(B) = 1.469) indicates that the odds that women make that choice is 1.5 times greater than men making that choice. This again confirms the “modern gender gap.” Interestingly, women are also more likely to vote for a right party with a feminist gender ideology (Exp(B) = 1.326) compared with a party with a traditional gender ideology. This shows that the position rightist parties take on gender issues influences the party's level of support among women voters. In particular, rightist parties that adopt a more feminist stance on gender issues are able to attract more women voters than rightist parties with a more traditional gender view. It is mostly center-right parties that adopt a more feminist position on gender issues in their public stance and have a majority of female voters among their electorate. Examples are the Christian democratic parties CD&V (Christian Democratic and Flemish) in Belgium and Kristdemokraterna in Sweden, and the liberal parties Centerpartiet in Sweden and the Swedish People's Party of Finland. The two liberal parties have an outspoken feminist gender ideology, so it is possible that they attract more feminist women voters. The two Christian democratic parties, on the other hand, adopt a more equivocal stance on gender issues, combining positions that at times support feminist policy interventions and at other times advocating traditional gender roles, which arguably allows them to attract the votes of right-leaning women in their respective countries.

Some of the control variables also show significant results. In line with other studies predicting party choice, we find that left parties draw significantly less from the support of married respondents and older (age 55+) voters. These voters have a higher chance of voting for a right-wing party. The gender ideology of the right party does not play a role here: married and older voters do not prefer a traditional right party over a feminist right party (or vice versa). Decreasing levels of political efficacy and interest decrease the chance that voters cast a vote for a feminist (either left or right) party; they instead opt for a right party with a traditional gender ideology. Age plays a role, with the oldest category of respondents (age 55+) having a significantly higher chance of voting for a right party with a traditional gender ideology.

Table 4 finally shows the same model but with an interaction effect between gender and age. The results show that especially younger women have a higher chance of voting for a left party with a feminist gender ideology. This confirms the gender-generation gap (Norris Reference Norris, Evans and Norris1999), namely, that especially younger women are drawn to leftist, feminist parties. Right parties with a feminist gender ideology remain more attractive to women in general than right parties with a traditional gender ideology.

Table 4. Multinomial logistic regression predicting party choice by gender ideology, with interaction effects

Notes: The model is a fixed effect model with country dummies. Reference category is “vote for right party with traditional gender ideology.” The fourth category, “vote for left party with traditional gender ideology,” remains empty and therefore is not included in the table. The B-coefficients are unstandardized coefficients. *** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05.

DISCUSSION

The exploratory analysis conducted in this article is a first step toward bringing party behavior, particularly party ideology, into studies of gender and electoral support for rightist parties. We show evidence of rightist parties that adopt feminist gender ideologies succeeding in securing more women's votes than rightist parties that espouse traditional gender ideologies. Future research should add more data points from across time and space. Changes in party gender ideologies over time might be measured through the systematic analysis of party manifestos and leaders’ speeches, which would triangulate our findings from expert survey evidence—reducing the risk of bias and path dependency in the measurements—and allow us to investigate the relationship between political leadership and the gender gap. Our findings suggest that such research would be a fruitful endeavor for subsequent study.

Here we were able to demonstrate that there is considerable variation in the gender ideologies of rightist parties, with many mainstream parties of the right competing with parties of the left over what we might consider feminist and liberal ideological space. Although the general trend for leftist parties to be more feminist and liberal than parties of the right holds, there is nonetheless considerable competition between parties of the left and the right that might be suggestive of rightist party attempts to represent feminist women. We find, in other words, that political parties can combine feminism with rightist economic ideologies. Parties of the populist radical right overall adopt more traditional gender ideologies than parties of the mainstream right, even though there is some variation. Although the literature has identified a shift toward more feminist positions among some elements of the PRR, particularly in Northern Europe, these parties remain considerably less feminist in their values than many other parties of the right. Notably, we found only one example of a PRR party with a feminist gender ideology score (PVV in the Netherlands).

How much attention a party gives to gender issues is best understood as determined by its overall position on the libertarian-authoritarian scale rather than linked to its position on gender equality per se. This confirms extant literature that suggests that rightist parties that combine laissez-faire economic values with liberal moral values are most likely to adopt feminist positions. In terms of attracting women voters, we find that rightist parties that adopt a feminist gender ideology are able to attract more women voters than other parties of the right. These are mostly center-right parties such as the Christian democratic CD&V in Belgium and the Kristdemokraterna in Sweden and the liberal parties Centerpartiet in Sweden and the Swedish People's Party of Finland. The two Christian democratic parties specifically combine feminist and traditional elements in their gender ideology, which arguably allows them to attract right-leaning women voters.

We have explored the role that party ideology plays in gender differences in party support and shown that there is considerable variation in how parties combine economic, moral, and gender ideologies that is, in turn, related to their recruitment of women voters. Future studies of the international gender gap in left-right party support should gather systematic information about party positioning to incorporate into explanatory models aimed at deriving more convincing accounts of how and why gender gaps vary across time and space.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X17000599.