In 2012, China witnessed the largest wave of anti-Japanese demonstrations since the normalization of relations between the two countries in 1972. The protests condemned Japan's decision to purchase three of the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands in the East China Sea. By our count, protesters took to the streets in 208 of China's 287 prefectural cities. Smaller waves of anti-Japanese protest occurred after a maritime collision in 2010 and over Japan's bid for a permanent UN Security Council seat in 2005. Anti-American demonstrations erupted after US planes accidentally bombed the Chinese embassy in Belgrade in 1999. Protests against France took place after France publicly contemplated a boycott of the 2008 Beijing Olympics in the aftermath of riots in Tibet.Footnote 1

China watchers have debated whether these waves of nationalist protest reflect the spontaneous eruption of grassroots grievancesFootnote 2 or state-led orchestration in order to gain diplomatic leverageFootnote 3 or divert domestic discontent. Studies of Chinese nationalism have been similarly polarized between “bottom-up” and “top-down” approaches, with scholars differing on whether Chinese nationalism is largely driven by genuine anger at foreign slights or manipulated to bolster state legitimacy.Footnote 4

We argue that explaining patterns of nationalist protest requires simultaneous attention to state and societal factors. In a strong authoritarian state like China, nationwide demonstrations do not take place without some degree of state acquiescence. However, nationalist protestors in the post-Mao era have generally not been akin to “puppets” or “rent-a-crowd” mobs that form at the state's behest. Indeed, nationalist protest in China is far more risky than conveyed by terms like “manipulation” or “state-sponsorship.” Nationalist activists and protest participants regularly run up against the limits of state tolerance and often risk increased surveillance, detention or arrest.Footnote 5 For the government, allowing nationalist demonstrations to take place risks creating a platform for other grievances to mobilize, while repressing patriotic activities leaves the government vulnerable to charges of hypocrisy and weakness.

In our view, variation in nationalist mobilization reflects both grassroots propensity to protest and state willingness to tolerate popular mobilization. Citizens are galvanized by genuine anger at provocative foreign actions. Government statements and media coverage raise the salience of foreign insults and signal that nationalist outrage is politically acceptable. At the same time, government authorities often fear the implications of street demonstrations for social stability and diplomatic relations, particularly if nationalist protests threaten to spin out of control and aggrieved citizens use the opportunity to mobilize for other purposes.

Most studies of nationalist mobilization have taken place at the national level, tracing state responses to popular mobilization across time to shed light on the repression as well as the facilitation of nationalist protest.Footnote 6 These studies have advanced our understanding of how diplomatic and domestic objectives have shaped opportunities for grassroots mobilization and participation, but their analytical leverage has been limited by relatively few observations across time and space.

This paper represents the first systematic attempt to analyse subnational variation in nationalist protest in China. Using original data at the municipal level concerning the 2012 anti-Japanese protests, we evaluate the impact of top-down and bottom-up factors. After describing the utility of studying local variation in nationalist protest amid the diplomatic crisis over the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands in 2012, we develop our hypotheses and their empirical implications by integrating anecdotal evidence to ground, motivate and operationalize these expectations. The third section introduces our city-level dataset of anti-Japanese protests, the methods used to collect the data, and our results.

The 2012 Anti-Japanese Protests: The Importance of Local Variation

Nationalist protest is one of the few forms of social mobilization in China that has successfully linked citizens across localities, with central authorities often choosing to tolerate, channel, and even coordinate anti-foreign protests rather than repress them. By using a national wave of anti-Japanese protests to analyse local propensity to protest and government concern for “stability maintenance,” we can “control for” the underlying issue, in this case Japan's purchase of the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands. Whereas most protests in China have local particulars, such as the location of proposed petrochemical plants, focusing on nationalist protests allows us to hold the perceived provocation constant and investigate local variation in factors that make protests easier or harder to organize.

On 7 July 2012, the 75th anniversary of Japan's full-scale invasion of China in 1937, the Japanese government announced its intent to purchase three of the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands from their private Japanese owner. As China pressured Japan to respect the supposed understanding reached by the two governments in the 1970s to “shelve” the territorial dispute, blanket Chinese media coverage praised Hong Kong activists who landed on the islands. On 15 August, two dozen activists staged a half-hour demonstration in front of the Japanese embassy.Footnote 7 In addition, calls for anti-Japanese demonstrations to take place over the weekend began to circulate online.Footnote 8

Between 15 August and 9 September, nearly sixty demonstrations took place in Chinese cities to protest against Japan's proposed “nationalization” and the landing of Japanese activists on the disputed islands. Despite a warning from President Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 on 9 September, Japan announced its decision to buy the islands on 10 September. By the end of September, 320 anti-Japanese protests had taken place; on 18 September alone, there were anti-Japanese protests in at least 128 cities across China.

Why did anti-Japanese protests take place in some cities and not others? What factors made some cities more likely to be early movers and see protests in August, while others only had demonstrations in September as the movement spread to nearly three-quarters of China's cities? Existing scholarship has largely focused on a handful of atypical cities, such as Beijing, Shanghai, Chongqing, Nanjing and Xi'an. Tracing nationalist mobilization in key locales has been invaluable for illuminating state–society interactions in the realm of nationalism and historical memory, but these experiences may not generalize well to the larger universe of Chinese cities. Although surveys have illuminated how nationalist sentiments vary across socio-economic and demographic groups,Footnote 9 we know little about how nationalist behaviour varies across more “typical” cities such as Zibo 淄博, Hengyang 衡阳 and other municipalities where millions of Chinese live.Footnote 10

Generalizing from a small set of cities may be problematic for policymakers as well as for scholars. In 2012, for example, the Japanese prime minister, Yoshihiko Noda, admitted that the scope of anti-Japanese protests in China had been greater than expected.Footnote 11 Some speculated that the Japanese government had relied too heavily on information from first-tier cities, where thick police cordons ensured that protests did not overrun Japanese diplomatic compounds. By contrast, anti-Japanese protests in several second- and third-tier cities escalated to violence before authorities reined them in. For instance, in Qingdao 青岛, a Panasonic factory was set on fire and a Toyota dealership destroyed.Footnote 12

Subnational variation in anti-Japanese protests has not been limited to 2012. In 2005, Shanghai witnessed large-scale anti-Japanese demonstrations after protests in Beijing had been curtailed, feeding speculation about dissent between supporters of Jiang Zemin 江泽民 and the Hu Jintao–Wen Jiabao 温家宝 administration.Footnote 13 In October 2010, anti-Japanese demonstrations took place in roughly two dozen second- and third-tier Chinese cities, despite the quiet in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou.Footnote 14

Many factors combine to produce an outcome in a particular city, making it difficult to conclude from anecdotal observations which explanations are more generally influential. For example, Asahi Shimbun cited several potential arguments for the absence of anti-Japanese protests in Dalian 大连. One diplomat speculated that a large-scale protest in Dalian against a petrochemical plant in 2011 had made local officials wary of allowing any demonstrations that might turn against the government. A local news editor suggested that anti-Japanese protests in Dalian could bring up the issue of re-evaluating Bo Xilai 薄熙来, who as mayor of the city in the 1990s had attracted a lot of Japanese investment and remained popular among locals. Others argued that residents in Dalian had a better understanding of Japan and that the migrant population in Dalian was relatively small.Footnote 15 The case of Dalian illustrates the difficulty of disentangling the relative weight of different factors: fear of local instability, the availability of potential participants (in this case migrants), and the dampening effects of Japanese trade and investment. More systematic data and analysis are needed to assess whether local observations are outliers or part of a more general pattern.

Anecdotes and Expectations: Where Are Anti-Japanese Protests More Likely to Arise?

We consider both citizens' propensity to mobilize and local authorities' willingness to tolerate potentially destabilizing protests.Footnote 16 In the post-Mao era, nationalist protests have generally been managed rather than manufactured by the state,Footnote 17 with windows of opportunity opening and closing as the central leadership considers its diplomatic and domestic concerns and objectives, weighing the risk of instability and the cost of repression alongside its desire to show resolve or reassurance.Footnote 18 However, central instructions on how to manage nationalist mobilization often trade specificity for principle by emphasizing, for example, the “rational expression of patriotism” (lixing aiguo 理性爱国) while “maintaining stability” (wei wen 维稳) above all. Central priorities must then be interpreted and implemented by local authorities who retain a degree of discretion and fear being held accountable for the outcomes of their actions.

For protest propensity, we consider local variation in patriotic sentiment, both grassroots and state-led, and the availability of resources that facilitate mobilization. Resources that facilitate protest and collective action include the biographical availability of potential participants as well as material and structural factors, such as population concentration, that facilitate networking and the spread of information. Although protests are comprised of individuals, “collective action” is defined by its group nature. The likelihood that protests escalate depends on the distribution of preferences across the population and expectations about the willingness of other citizens to participate.Footnote 19 Shared grievances and resources shape whether individuals judge that others will join in and shield them from potential repression. Because the larger “political opportunity structure” for protest in an authoritarian state is shaped by local governments' willingness to tolerate demonstrations, we also consider measures that may be used as a proxy for official fears of instability.

Patriotic sentiment

Higher levels of patriotic sentiment may correspond to a greater likelihood of anti-Japanese protest. Nationalist anger is costly for the government to quash, particularly when citizens chant “patriotism is not a crime!” (aiguo wuzui 爱国无罪) and rally behind emblems of state-sanctioned patriotism, such as monuments to fallen martyrs. Along with patriotic feelings inculcated by state education and propaganda, grassroots grievances may stem from the legacy of Japan's invasion during the Second World War.Footnote 20 Assessing variation in the level of grassroots anti-Japanese sentiment in a community is a complex task.Footnote 21 As one plausible proxy for variation in grassroots grievances stemming from the legacy of the Second World War, we use data on Japan's occupation and invasion.

Given the passage of time, however, few Chinese have first-hand experience of the trauma of Japanese occupation. To instil patriotic sentiment among younger generations of Chinese citizens, the Chinese government has, since the early 1990s, designated certain historical sites, relics, monuments and modern achievements as “patriotic education bases” (aiguo jiaoyu jidi 爱国教育基地) that students must visit, along with mandatory films and coursework in patriotic education.Footnote 22 A 1991 CCP Central Committee document outlined the rationale for these sites: “Using the rich historic relic resources to conduct education on the masses about loving our motherland, loving the Party, and loving socialism has the characteristic of visualization, real, and convincing.”Footnote 23

As a proxy for variation in state-led nationalism, we examine the subnational distribution of patriotic education bases. The presence and proximity of such bases may instil greater awareness of China's historical humiliation, signal the political correctness of expressing patriotic sentiments, and provide a focal point for mobilization. During the 2012 anti-Japanese protests, for example, protesters in the city of Hengyang in Hunan province gathered at the local memorial for the War of Resistance against Japan on 18 September, many wearing white T-shirts that read “Japan, Get Out of the Diaoyu Islands.”Footnote 24

Although areas occupied by Japan in the Second World War are more likely than non-occupied areas to have patriotic education bases, these factors are far from perfectly collinear. In the initial list of 100 national-level patriotic education bases established by the Ministry of Civil Affairs in 1995, only 20 were dedicated to the War of Resistance against Japan (1937–1945).Footnote 25 The central government has continued to encourage patriotic education and “red tourism” by designating hundreds of additional sites and encouraging lower level governments to follow suit.

Collective action resources and biographical availability

Protest propensity also depends on the ability of activists and protesters to access the resources and networks that facilitate mobilization. Wealth and education, for example, are likely to increase the level of popular attention given to foreign policy and the spread of information about potential protests. More specific resources include access to the internet and other social media, as well as physical proximity and the density of networks among students on university campuses.Footnote 26 Arguments about “biographical availability” suggest that low opportunity costs can facilitate social mobilization among those who have plentiful free time. Protesting takes time and energy away from earning a living, feeding one's family, and remaining employed, so those with “less to lose” may be more inclined to participate in a relatively high-risk activity like protest.Footnote 27

The combination of biographical availability, dense networks and a higher degree of education make students a particularly common source of protest participants. As Xinhua noted during the 2010 anti-Japanese protests, “thousands of college students marched, holding flags, banners and shouting slogans such as ‘the Diaoyu islands are China's’.”Footnote 28 Although some observers noted the lack of student participation in the 2012 anti-Japanese protests, particularly in first-tier cities like Beijing and Shanghai, elsewhere students were noticeably present.Footnote 29 In 2012, several hundred college students who had organized over the internet gathered outside an Ito Yokado department store in Chengdu on 19 August.Footnote 30

Retirees are another group of relatively available participants as they have more free time and fewer burdens.Footnote 31 During the 2012 anti-Japanese protests, dozens of veterans of the Sino-Japanese war in Guigang 贵港 in Guangxi province marched to denounce Japan's purchase of the islands.Footnote 32 Photos posted online showed participants processing behind banners and placards that read “veterans of Guigang.”Footnote 33 In Pingxiang 萍乡 (Jiangxi), the local veterans' association organized a group of anti-Japanese protesters, some of whom marched in old military uniforms and carried a sign asking to be assigned to defend the Diaoyu islands.Footnote 34

Unemployed graduates are another such group, often referred to as the “ant tribe” because they live in cramped underground quarters, unable to find employment commensurate with their skills. During the 2010 anti-Japanese protests in Xi'an, the Daily Yomiuri reported that “young people who cannot earn a regular income gathered by contacting each other through the Internet and continued protesting” after the students who organized the protest had dispersed.Footnote 35 With limited alternative channels for expressing discontent, nationalist protests may also give aggrieved citizens, including dispossessed farmers, migrant workers and laid-off workers, the opportunity to air their grievances. Low levels of GDP growth may sharpen such societal discontents. In Baoji 宝鸡, protest banners criticized government corruption and high housing costs during the ostensibly anti-Japanese protests in 2010.Footnote 36 On the eve of rumoured demonstrations on 18 September 2010, Ai Weiwei 艾未未 retweeted: “Can we turn the anti-Japanese protest into anti-forced demolition protests? That would be more meaningful.”Footnote 37 In Xi'an, a protester who identified himself as a member of the “ant tribe” complained: “Even if students graduate from university, they can't find a job if they don't have connections. Children of senior Party officials and the rich can get on the elite track even if they're incompetent.”Footnote 38 Evidence of unrelated grievances surfaced again during the 2012 anti-Japanese protests. In Hunan, one protest banner read: “Laid-off workers protect the Diaoyu islands.”Footnote 39 In Shenzhen, protesters attacked government offices and demanded unpaid wages. One migrant worker stated that being surrounded by thousands of anti-Japanese protesters and smashing a riot van gave him a feeling of “pure happiness.”Footnote 40

Political opportunities: local government attitudes

Grievances provide the motivation to protest, and resources and biographical availability affect which populations are more likely to participate. In a non-democratic country such as China, however, windows of opportunity for street protest can be opened or closed by officials at the national and local level. A common conjecture is that Chinese officials have manipulated anti-foreign demonstrations to buttress popular support for the regime and distract citizens from socio-economic grievances.Footnote 41

In contrast, we argue that discontented and easily mobilized populations may make government officials more wary of allowing nationalist protests, since protests may change direction and target the government itself. Indeed, if the risk of social unrest is too high, Chinese authorities may decide to pre-empt and repress nationalist mobilization altogether. In other cases, local authorities may choose to allow nationalist protests but will adopt measures to mitigate the risk that protests become unmanageable.

While students, migrant workers and the “ant tribe” of unemployed graduates are all biographically available, their participation does not pose a uniform risk to social stability. In particular, unemployed graduates have relatively little to lose and are less “legible” to the government than either students or migrant workers, as they operate outside of institutions that aid in social control, such as universities and the hukou 户口 (household registration) system.Footnote 42 Students may fear disciplinary measures that jeopardize their post-graduation prospects and migrant workers may lose the jobs that give them a tenuous foothold in the city.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the Chinese government has chosen to manage the risk posed by student participation through soft containment and dissuasion. According to a detailed blog report on the 2012 anti-Japanese protests, city authorities in Xiangtan 湘潭 in Hunan province emphasized that colleges were to be monitored with “full force” to prevent “people with ulterior motives” from taking advantage of students' patriotic passion.Footnote 43 Should local leaders fail to follow orders, they would be held accountable. After a few hundred students from Xiangtan University defied university warnings and rushed off campus on 16 September, a large police force and city and university officials persuaded the group to conduct the protest on campus. These “stability maintenance” measures achieved “extremely ideal” outcomes, the blog post concluded, for nearly ten colleges in the city had similar experiences. Most importantly, no linkage or collaboration (xianghu chuanlian 相互串联) were forged between students and businesses.Footnote 44

In other cases, government fears of social unrest may prompt the pre-emptive repression of nationalist mobilization altogether. In both Dalian and Qidong 启东, anti-Japanese protests were absent in August and September 2012. In both locales, authorities had already witnessed severe unrest over environmental concerns. On 14 August 2011, Dalian witnessed an anti-PX protest, and in Qidong (Nantong 南通, Jiangsu), demonstrators and local authorities clashed during a July 2012 protest against the construction of a waste pipeline by a Japanese-backed paper factory.Footnote 45

To assess local stability concerns that might encourage city authorities to take greater precautions against potential protests, ideally we would have data on local variation in citizen grievances and other types of domestic protest.Footnote 46 Unfortunately, these data are even more difficult to collect systematically than variation in nationalist protest and sentiment. However, a number of variables may affect local government fears of instability and incentives to repress nationalist protest.

First, leaders in areas with large ethnic minority populations may be wary of allowing protests of any kind, including nationalist protests by Han Chinese, that may exacerbate ethnic nationalism and resentment. Second, leaders of cities that rely on Japanese trade and investment may worry that anti-Japanese protests might undermine the local economic engine. Third, the duration of a leader's tenure in a locality may affect his or her willingness to gamble on allowing nationalist protests. On the one hand, nationalist protests may help local elites demonstrate their patriotic credentials at a time when national-level signals are focused on showcasing Chinese resolve against foreign provocations. By showcasing their anti-Japanese bona fides, local leaders may seek to bolster their prospects for advancement up the Party hierarchy.Footnote 47 On the other hand, nationalist protests may get out of hand and cause social unrest, jeopardizing local officials' prospects for promotion. As a nationalist activist in Shanghai put it, “There's no 100% guarantee that something will happen that the authorities can't control. If they say yes, they have to be on guard in case something arises. But if they say no, they can rest easy.”Footnote 48 Leaders recently appointed as mayor or Party secretary may be eager to prove themselves, but leaders with a longer tenure in a given locality may be more likely to be considered for promotion. Since new leaders are less likely to have consolidated control and established mature ties to the local security apparatus, they may be more reluctant to gamble on tolerating protests that could become difficult to rein in.

Dependent Variable

We collected data on the presence or absence of anti-Japanese protests in all Chinese prefectural-level cities from 15 August to the end of September 2012. Of the 287 prefectural-level cities in the data, 208 had at least one anti-Japanese protest, recording a total of 377 anti-Japanese protests.Footnote 49 The modal number of protests in a city was one, with 94 cities having just a single instance of anti-Japanese protest over this time period. The number of cities that had no protests (73) was about the same as the number that had two (73). Another 41 cities had three or more protests during this period. At least 64 cities witnessed protests of a 1,000 or more participants.Footnote 50

To gather the protest data, we conducted online searches in Chinese, combining the names of each of these 287 cities with relevant keywords. The primary search term was anti-Japan (fanRi 反日), with other keywords including “anti-Japanese protest” (kangRi youxing 抗日游行), “protect the Diaoyu islands protest” (bao Diao youxing 保钓游行), as well as simply “protest” (youxing 游行 or shiwei 示威) and the dates in question. Sources included media reports, internet bulletin board posts and videos, activist websites, individual blogs, and Weibo.

At least two sources were required to indicate that a city had had an anti-Japanese protest on a given date. The minimum size for a protest to be counted was five participants. In addition to coding the absence or presence of a protest on a given date and our confidence in that assessment, we collected information on protest size, location within the city, degree of property damage and personal injury, demographic characteristics, and the presence and actions taken by any security personnel at the scene. Damages and injuries were reported in 54 protests. Public security officials (either city police or people's armed police) were on the scene in at least 219 protests, with the modal action being “walk or drive alongside protest marchers, guiding the way” (during 102 protests).

The 2012 anti-Japanese protests happened in two waves.Footnote 51 The early wave occurred in August, with 51 cities having at least one anti-Japanese protest. Following Japan's decision to proceed with the purchase of the islands on 10 September, a second wave of protests took place on 11–23 September.Footnote 52 The second wave peaked on the 18 September anniversary, with at least 128 cities experiencing protests.

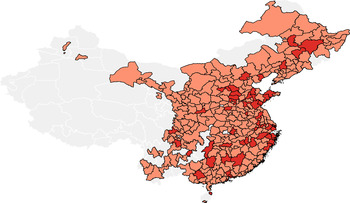

Maps 1, 2, and 3 identify the Chinese prefectural cities that witnessed anti-Japanese protests during August and September 2012.Footnote 53 Cities with at least one protest are darkly shaded. Cities without an observed protest are lightly shaded.Footnote 54Map 1 depicts prefectural cities with anti-Japanese protest(s) in August. Map 2 presents cities with anti-Japanese protest(s) in September prior to the peak on 18 September, and Map 3 presents all cities having September protests.

Figure 1: Simulated Results of Increasing the College Student Population

Map 1: August Protest

Map 2: September Crescendo (pre-18th)

Map 3: September Protest

In the analyses below, our dependent variables are dichotomous, capturing whether a city witnessed an anti-Japanese demonstration during three periods: the August “early risers”; the early-to-mid-September “crescendo”; and all of September, including the “peak” on 18 September. Temporal disaggregation is important for two reasons. First, where protests start is a different question than where protests spread to once contagion and diffusion set in. Second, local leaders received instructions from higher-level authorities as the 18 September anniversary approached. On 17 September, a high-level circular instructed all government units to “properly manage issues arising from some mass marches against Japan's illegal ‘islands purchase’.”Footnote 55 As local authorities began to “actively guide, plan, and carry out stability maintenance work on ‘9.18’ and thereafter”Footnote 56 in keeping with central directives, increasing efforts to coordinate and stage-manage street demonstrations, anti-Japanese protests became more politically correct, likely diminishing the impact of local differences.Footnote 57 Indeed, so many cities had anti-Japanese protests on 18 September that there is less variation to explain.

Independent Variables

We use two measures that provide rough proxies for grassroots and state-led nationalist sentiment. First, we use a list widely circulated among Chinese netizens that records the number of cities and counties occupied by Japan and an estimate of the percentage of land in each city's jurisdiction that was under Japanese occupation during the Second World War.Footnote 58 Although we take no position on the accuracy of these figures, they are a reasonable proxy for nationalist grievances produced and disseminated at the grassroots level rather than guided by state propaganda. For a city/county to be counted as “occupied” in this list, it must have existed prior to the Japanese occupation, based on Republican China (Kuomintang-era) administrative units, and Japanese forces must have occupied the county seat and not just the surrounding villages.Footnote 59

As a proxy for state-led nationalism, we code the presence or absence of patriotic education bases in a prefectural city using the list of national-level patriotic education bases released by the Chinese government.Footnote 60 These bases can be divided into five different categories: science and technology, CCP Party history and civil war, the War of Resistance against Japan (as the Second World War is termed in China),Footnote 61 other anti-foreign (for example, the Dagu forts (Dagu paotai 大沽炮台) in Tianjin, which played a starring role in the Opium Wars), and others.Footnote 62 These bases are common but not universal, with 123 cities in our dataset having no such bases.Footnote 63

For collective action resources and biographical availability, we use socio-economic data from China's 2010 census and China's National Bureau of Statistics unless otherwise specified.Footnote 64 We expect the total population size of a city to be positively associated with the likelihood of protest because a smaller share of the population is needed to turn out for a demonstration to occur.Footnote 65 Similarly, the wealth of a locality may reflect its mobilization capacity, with richer areas as measured by GDP per capita (logged) having greater capacity. The rate of real GDP growth provides a base estimate of which areas are growing relatively slowly or quickly and may capture variation in socio-economic grievances.Footnote 66 For students, we utilize enrolment figures for institutions of higher education on a per capita basis for each city.Footnote 67 Data on migrant workers come from the 2010 national census, as its migration data are considered to be the highest quality.

We also consider several factors that may exacerbate local leaders' sensitivity to social unrest and dampen their willingness to allow nationalist protest, including the size of the non-Han population, local unemployment, economic ties to Japan, and the career status of the local leader. Non-Han populations may be less excited by anti-Japanese fervour, and local leaders may be more concerned about social unrest, particularly the risk that anti-Japanese protests might trigger ethnic riots in the presence of larger non-Han populations. Data on non-Han population shares and unemployment data at the city level come from the 2010 national census.Footnote 68 Chinese unemployment data do not follow international practices. The census asked individuals filling out the long form of the survey about their employment situation. We focused on a particular subset of the unemployed population – those recently graduated but unemployed (the “ant tribe”) – as this group is often regarded as an especially dangerous one.Footnote 69 As one measure of local economic ties to Japan, we utilize city-level exports to Japan from the China Customs Service Information Center.Footnote 70

Leaders with a longer tenure in a locale might be more willing to allow protests, since they may have developed the connections and local expertise to quell a protest should it become unruly. To examine this possibility, we code cities based on the arrival of their top leadership. When both the mayor and Party secretary of a city arrived recently (i.e. between 2010 and August 2012), we code the city as having no established leaders. If one leader arrived before 2010, then this variable takes a value of one. If both leaders arrived before 2010, it takes a value of two. Table 1 presents the summary statistics for the variables used in the analysis below.

Table 1: Summary Statistics

Analysis

Table 2 presents five models examining the August wave of protests across 51 cities in China. The results support our argument that citizen propensity to mobilize and local government insecurity are both important in accounting for variation in protest activity at the prefectural level.

Table 2: City Correlates of August Protest Wave Participation

Notes:

All models are logits. Robust standard errors in parentheses. * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

Regarding grassroots nationalist sentiment, we find a positive simple correlation between areas that were fully occupied by the Japanese during the Sino-Japanese theatre of the Second World War and August protest (r = 0.15); indeed, protests were more than twice as common in such areas.Footnote 71 However, the estimated coefficient for Japanese occupation is statistically indistinguishable from zero when added to a multivariate analysis.

On the other hand, the presence of patriotic education bases in a city is strongly and positively associated with anti-Japanese protests. Interestingly, separating the bases by type diminishes the correlation between these bases and the protests in question. That is, while the number of patriotic education bases in a locality strongly correlates with having at least one protest in August (r = 0.34), there is essentially zero correlation between the number of anti-Japanese bases and having an early protest (r = 0.0013). Model 1 shows a strong positive estimated coefficient for the presence of one or more patriotic education bases on the probability of protest. However, Model 2 shows that this effect disappears when we include only anti-Japanese bases.

As for resources that facilitate mobilization, we find that population size, the number of migrant workers and the share of college students in a prefecture are all positively associated with the likelihood of protest in August (Models 1 through 5). Larger cities need a smaller share of their citizens to mobilize a protest, making the positive relationship between population and protest unsurprising. As for biographical availability, we find that larger migrant populations and migrant population shares are associated with a greater likelihood of having anti-Japanese protests in both August and September (see Table 3).Footnote 72

Table 3: City Correlates of September Protest Wave Participation

Notes:

Robust standard errors in parentheses. * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01. All population figures come from the 2010 Chinese National Census.

Similarly, a larger college student population substantially increases the likelihood of an early protest.Footnote 73 On average, college students make up less than 1.2 per cent of the population in the 221 cities that did not have an August protest, compared with 4.0 per cent of the population in the 51 cities that had protests. This effect is robust to the inclusion of different covariates, as seen in all of the models presented in Table 2.

The college student effect is also depicted in Figure 1. Holding other factors (from Model 1) constant at their means, as the number of college students increases from its mean level of around 17 per thousand to over 50, protests move from very rare to extremely likely.

The strong negative coefficient on GDP growth indicates that slower (faster) growing cities were more (less) likely to participate in the early wave of anti-Japanese protests. The patterns appear consistent with arguments that nationalist protests should be easiest to mobilize where socio-economic grievances are higher, perhaps owing to sluggish economic growth. These results should be interpreted with caution, however. First, GDP growth rates at the sub-national level are linked to the promotion prospects of politicians and many believe them to be manipulated for precisely that purpose.Footnote 74 Second, even the lowest value of GDP growth in the data represents a local economy increasing in size by 3.3 per cent per year, a value which would be the envy of much of the world. Interestingly, the level of economic development in a locality, as measured by GDP per capita, never has an effect on protest propensity, as seen in Model 4.Footnote 75

As local leaders may vary in their willingness to allow nationalist protest, we analyse observable characteristics of the city leadership. Cities with established leaders at the top of the local Party-state were more likely to participate in the August wave of protests, perhaps because these leaders were more confident of their ability to maintain control or because they were more eager to demonstrate their patriotic credentials. However, cities with established leaders were no more or less likely to have protests in September, consistent with our expectation that central instructions in mid-September diminished the role of local leader-specific preferences (see Models 8 and 11, Table 3). Other factors, such as the age of the local leadership and exports to Japan in total or per capita terms, were not associated with patterns of protest at the city level in August or September.Footnote 76

Did similar patterns emerge during the larger wave of protests in September 2012, when 55 per cent of cities had at least one anti-Japanese protest before the 18 September peak? As Table 3 shows, the September wave of protests followed similar patterns, with a couple of interesting differences. First, having an August protest is positively associated with having an early September (pre-18 September) protest. Second, there are negative correlates for early September protests that are not present for the August set. A higher minority share of the population and a higher “ant tribe” share of unemployed college graduates are associated with a lower likelihood of protest in early September.Footnote 77 These negative correlates are consistent with expectations that local authorities with greater fears of social instability were less likely to tolerate nationalist protests. GDP growth is no longer associated with a decreased or increased likelihood of anti-Japanese protest. If one expands the analysis to include all September protests, only college students and total population remain positive correlates and minority share remains a negative correlate. These results hold if one only considers large protests of at least one thousand to tens of thousands of participants.Footnote 78

An alternative reading could interpret these variables – size, college students, migrants, patriotic bases – as proxies for a city's political importance, whereby provincial capitals might be particularly prone to such protests.Footnote 79 However, while positively correlated in a univariate analysis, the coefficient on a city's provincial capital or municipality status remains zero in a multivariate framework, while its overall, migrant, and student populations remain significant, as does the presence of patriotic education bases.

Conclusion

Although China witnesses tens of thousands of “mass incidents” each year, most remain localized. Protests that advocate national objectives, such as greater media freedom or systemic reform, are quickly shut down, while localized protests may insulate higher-level authorities from blame and provide information to curb local malfeasance.Footnote 80 Despite the flourishing literature on contentious politics in China, we lack systematic data on local protests, and even national-level protest statistics are less than transparent in their accounting.Footnote 81 This paper offers the first systematic subnational analysis of an important form of political contention in China – nationalist protest.

Many observers have pointed to nationalist sentiment as a leading cause of uncertainty over China's willingness to fight a potentially calamitous war over islands and maritime resources in the East China Sea.Footnote 82 Despite a rich body of scholarship on Chinese nationalism, however, local variation in nationalist protests has received relatively little attention. The complexity of the combination of state and societal factors points to the benefits of a subnational and multivariate approach, allowing us to examine simultaneously the influence of patriotic education and the legacy of Japanese occupation, the concentration of “biographically available” populations such as students, migrant workers and unemployed graduates, and local government insecurity and fears of social unrest.

We find that anti-Japanese protests were more likely in larger cities with more migrants, college students and patriotic education bases, but less likely to occur in cities with larger minority and unemployed college graduate populations. Our conclusions about college students, urban population size and ethnic minorities echo earlier findings from the 1989 democracy movement, which suggests that these factors may not be unique to nationalist mobilization.Footnote 83 To avoid problems of ecological inference, we cannot conclude that college students or migrant workers are more likely to protest based on the evidence that cities with more college students or migrants per capita had protests. Nevertheless, our findings accord with anecdotal observations that students and migrants often participate in nationalist demonstrations and that patriotic propaganda helps to stoke popular anger and to signal the desirability of public displays of nationalism. The subnational pattern of the 2012 anti-Japanese protests appears to reflect current grievances and opportunities more than geographic variation in Japanese occupation. However, we hope future research will obtain and utilize more fine-grained measures of grassroots nationalism.

As for the local political opportunity structure, our findings suggest that city leaders may have played a key role in determining whether protests were allowed to occur by interpreting national-level windows of opportunity and “stability maintenance” guidelines in the context of local concerns. Protests during the August wave of “early risers” were more likely to take place in cities where local leaders were more established. Further research is warranted to discern the mix of risks and career rewards that local leaders confront in determining whether to permit, stage-manage, or repress nationalist demonstrations altogether.

Our conclusions shed light on local variation in citizen propensity to protest while heeding calls to disaggregate the political opportunity structure in studying contentious politics in China.Footnote 84 Unlike other protests in China, nationalist protest is primarily directed at foreign targets. Although demonstrations can veer off course by airing local complaints or criticizing foreign policy weaknesses, nationalist demonstrations are less likely to jeopardize the promotional prospects of local officials than other types of protest. City leaders may even benefit from demonstrating their patriotic bona fides. We leave to future research the important task of investigating the local consequences of nationalist protest on political promotions and economic performance, particularly foreign trade and investment.

Appendix

Appendix Figure 1: Daily Count of Anti-Japanese Protests, August–September 2012

Appendix Table 1: Large Protests Explained by Same Factors

Appendix Table 2: Exports Do Not Affect Protest Likelihood

Appendix Table 3: FDI Does Not Affect Protest Likelihood

Appendix Table 4: 1989 Protests Do Not Affect Protest Likelihood