I INTRODUCTION

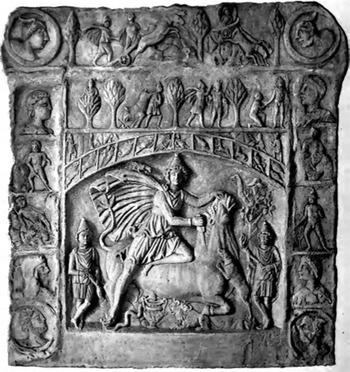

The scene of Mithras kneeling on the back of a bull and driving the blade of his sword halfway into its shoulder has iconic status.Footnote 1 A simple example of the type is the relief from the Capitoline illustrated in Fig. 1, which includes the usual trio of animals (scorpion, snake and dog) underneath the bull and five other figures observing the scene from the sidelines: the raven on the end of Mithras' cloak, the flanking torchbearers, and in the upper corners Sol and Luna.Footnote 2

FIG. 1. A relief from the Capitoline Museum. (Drawing after TMM 2.195, no. 7, fig. 19)

Monumental versions of these scenes, sometimes measuring nearly 2 m square as the Nedderheim relief in Fig. 2,Footnote 3 were often painted or carved in relief at the far end of mithraea; they usually keep the central scene intact, but place additional witnesses in the lower corners and narrative scenes at the sides and along the top separated, as here, in boxes or by trees, while a zodiac arches over the head of the god.

FIG. 2. The Nedderheim Relief. (Drawing after TMM 2, after p. 364)

Despite its popularity during the Roman imperial period, the Mithraic icon continues to puzzle modern scholars. Fifty years ago they explained it as a divine model for the bull sacrifices that were thought to be performed by worshippers, but better archaeology and the discovery of many more mithraea have revealed that worshippers ate roosters, piglets, sheep and many other smaller animals in Mithraic sanctuaries, but not bulls.Footnote 4 In recent years, moreover, scholars have stressed that some of the standard details in the scene, for example, the scorpion attacking the testicles of the bull or the wheat sprouting from its tail, clearly demand some kind of symbolic, rather than literal, interpretation; an approach that has found increasing support in the recent ‘astrological turn’ in Mithraic studies, which focuses on the most elaborate monuments, like the one in Fig. 2, where the added stars and zodiac suggest more complex interpretations of the central scene, for example, that the scorpion and the bull refer to the zodiac signs Scorpio and Taurus, or that the entire scene can be read as some kind of star map.Footnote 5 Others assume that the two-person vignettes in the additional narrative scenes on the periphery — some of which include Mithras dragging a bull or reclining on a bull-skin at a feast with Sol — comprise a connected biography or myth about Mithras in which the stabbing of the bull serves as his crowning heroic achievement.Footnote 6 A third approach suggests that the image has cosmogonic meaning: that by killing the bull Mithras releases into the universe the bull's creative force, a force illustrated by the ears of wheat that sometimes sprout from its tail.Footnote 7

All of these different approaches — old and new, literal and symbolic — agree, however, on one central fact: Mithras is depicted in the act of killing or sacrificing the bull. Indeed, scholars by convention call this scene a tauroctony (‘bull-slaying scene’), a nice-sounding Greek noun that appears nowhere in Mithraic inscriptions or literary testimonia and in fact nowhere in ancient Greek.Footnote 8 There is, moreover, a major problem with understanding the scene as a sacrifice: in an article published in 2009, Glenn Palmer, after much research on the anatomy of the bull, concluded that a downward stroke into the shoulder of a bull would not be fatal, at least not in the short run.Footnote 9 And since this vertical stroke is repeated in 80 per cent of the extant images,Footnote 10 it seems that Mithras is, in fact, caught in the act of wounding a bull, not killing it.Footnote 11

I begin, then, with the inconvenient fact that the central design does not depict a sacrifice, real or symbolic. Instead, drawing on parallels from contemporary amulets used against the evil eye, I offer a new reading of the central Mithraic icon as a design that combines the overall structure of these amulets with the popular scene of the goddess Nike performing a special military ritual known as the sphagion. My argument makes no assumptions about or reconstructions of any underlying Mithraic beliefs or mythology and instead depends entirely (and perhaps naïvely) on a formal and comparative analysis of the images. Along the way I offer explanations of some of the most puzzling details: (i) that Mithras draws back the neck of the bull, but does not slit its throat; (ii) that he never looks at the bull; and (iii) that the scorpion attacks the bull with its annoying pincers, rather than its deadly tail. I conclude by suggesting that this iconic scene must have been understood by its creator and by some viewers, at least, to offer protective power in this world, as well as salvific assurance about the next — a dual focus that was common to most mystery cults, but which seems to have been especially strong in Mithraism.Footnote 12

This study is divided into three parts. In the first, I focus on the smaller and often ignored household and personal versions of the Mithraic icon in order to show that some of these images, at least, were probably used as amulets. In the second, I examine a series of amulets designed to ward off the evil eye and argue that the overall design of these amulets — with animals attacking the eye from below and man-made weapons from above — offers a neglected but important parallel for the formal arrangement of the figures in the central Mithraic scene. And in the third section, I contrast the icon with similar images of the goddess Nike attempting to kill a bull, a scene which — all scholars agree — was the iconographic source of Mithras' posture on the back of the bull. By focusing on some important dissimilarities between the two scenes, I show how the creator of the icon was forced to make crucial changes in the Nike model in order to fit it into the design borrowed from the evil-eye amulets. I conclude by suggesting that, although in the largest communal monuments there were many accretions around the periphery of the central image, each with its corresponding mythical, astrological or cosmogonical spin, the central scene itself remained relatively unchanged and available as a protective device in the sometimes dangerous lives of the men who worshipped the god.

II THE BULL-WOUNDING SCENE IN MINIATURE

Although the large communal monuments have attracted the most scholarly attention over the years, there are numerous smaller versions. Mithraic icons of such small size are, in fact, often found inserted into the side-walls of mithraea as votives. Stylistic analysis reveals, moreover, that these smaller versions sometimes travelled far from the Central European sites of their manufacture to Rome and the East, where they were eventually dedicated in contexts that suggest military personnel: a good example is a rudely worked and badly weathered marble medallion, roughly 4 ins in diameter and of Dacian style, that ended up in a mithraeum in Caesarea Maritima in Palestine.Footnote 13 Because it was found in a sanctuary, scholars rightly assume that it was a votive, but it is difficult to explain how a medallion carved in Central Europe ended up in Palestine. Normally, when someone made a vow — for example, a soldier hoping to return alive from an expedition — he would, upon his safe return, commission the work locally, whether it be a small statuette, an altar or a relief like the one from Caesarea. As a result, most votives are produced in local media and in a local style. But this one and a number of others found in Mithraic sanctuaries were made in a place far away, suggesting that their owners carried them along on campaign and eventually dedicated them at the end of their service.

The question then arises: before arriving in Caesarea from Dacia, was this medallion used in private worship? Or was it, in fact, a personal amulet used to protect its owner? Gordon, the one scholar who has studied these smaller icons in detail, suggests, in fact, that they were originally designed for private or domestic worship, but he rightly worries that it is not ‘easy to imagine the kinds of ritual that might have been celebrated within such a small group’.Footnote 14 Indeed, the Mithraic mysteries were notoriously restricted to men and celebrated in special underground or sunken dining chambers with no windows. Thus it seems unlikely that they could be performed, for example, in the dining-room of a private house. A beautifully etched bronze brooch from Ostia (Fig. 3) has a diameter similar in size to that of the Caesarean tondo and it is equally difficult to contextualize.Footnote 15 Like the other smaller images it presents a simplified scene: the two torchbearers have been replaced by birds, a rooster on the right and a raven on the left, while another raven rests on the tail of the bull. One could argue, of course, that this was an ornament worn by a Mithraic officiant during a secret ceremony, but we cannot, I think, rule out the idea that it might have also been used as an amulet or even worn into battle.

FIG. 3. An etched bronze brooch from Ostia (colour image online). (Photograph used with the permission of the Asmolean Museum)

The question of the utility of these smaller images is more easily settled in cases where the scene is accompanied by inscriptions. A prehistoric stone axe-head (a so-called ‘thunderstone’) from Argos, for example, was in Roman times engraved with two scenes (Fig. 4).Footnote 16 It is roughly 4 ins tall and 2 ins wide. In the lower half we see the standing figures of Athena and Zeus in a scene reminiscent of a gigantomachy like the one on the Altar of Zeus at Pergamum: the goddess is about to stab a tiny snake-footed ‘giant’ with her spear, while her father looks on holding a sceptre topped by an eagle, his usual attribute.Footnote 17 In the upper register we find a simplified version of the Mithraic icon: the bull is surrounded by animals, which do not lick its blood, the scorpion seems to be missing, and a bird rests on the bull's extended front leg. The god, moreover, holds his sword over the upraised head of the bull, instead of plunging it into his shoulder. This second scene is encircled by two words inscribed in Greek, Bakazichuch and Papapheiris, magical names for solar deities that appear often on other amulets.Footnote 18 The parallelism between the two scenes on this axe-head is also noteworthy: in both powerful divinities (Mithras, Athena and Zeus) threaten powerful adversaries (a bull and a snake-footed giant). Because this object is unique, it is difficult to say what it was used for, but the parallel scenes of divine triumph, the magical inscriptions and the well-documented use of inscribed thunderstones to protect ancient houses from lightningFootnote 19 all suggest that this Argive stone was also used as a protective amulet.

FIG. 4. A prehistoric stone axe-head (‘thunderstone’) from Argos. (Drawing after Cook (1925), 512 fig. 390)

Gemstones, fitted for finger-rings or pendants, also carry simple versions of the Mithraic scene and seem to have been used as body amulets (see Appendix B for the numbered gems below). On two similar gems (Nos 7 and 11) we find the lower part of the bull surrounded by stars, a dog, a snake and a raven, but the scorpion appears only on No. 11. There are no torchbearers or other internal witnesses. We get a fuller version of the scene on a gem in Florence (No. 2; see Fig. 5), on which two birds, seven stars and various weapons (e.g. thunderbolt, sword, harpê, arrow) seem to float over the god and the bull.Footnote 20 Below we see the dog charging the bull from the right and beneath it a dolphin or fish; there is, moreover, a turtle to the left beneath the bull's tail. Note also how the bull turns its head to look at Mithras, a pose that we never find on the larger versions. On the reverse of this gem we find seven magical words each inscribed in a circle around a star, while a lion walks in profile. A gem from Udine (No. 3) is similar in design, especially with regard to the twisting bull's head and the unorthodox animals below (a dolphin and a turtle). A broken gem (No. 10) in Paris has the Mithraic icon on one side and the magical palindrome ablanathanalba on the reverse, a word that appears on many amulets.Footnote 21 Here, too, as on many of these gems, the dog and snake do not lick the blood from the wound: they simply confront the bull.

FIG. 5. Red jasper gem in Florence. (Drawing after Maffei (1707), pl. 217.2)

Until quite recently,Footnote 22 scholars have generally overlooked these miniature scenes, whose iconography differs from the monumental scenes in three important ways. Of the eighteen extant examples collected in Appendix B: (i) seven show only the god and the animals; (ii) on eight the scorpion is missing; (iii) on eleven the animals abstain from licking the blood; and (iv) eight have magical texts or symbols.Footnote 23 There seems, in short, to be some correlation between the use of a simplified and more banal version of the central scene and the appearance of a magical text, but does this mean that only those inscribed with magical texts are amulets?Footnote 24 Gordon suggests that all these gems were probably used as ‘portable versions of the central cult icon, which initiates could choose to have made either for protection or private devotion’ and that ‘they functioned as an extension of the principle of the small house-relief’.Footnote 25 In the end, however, he believes that the gems in particular ‘with their idiosyncrasies and deviations from the standard iconic repertoire’ seem to represent various kinds of ‘personal reinterpretation’ of the icon.Footnote 26

III AMULETS AGAINST THE EVIL EYE

There is, in fact, good evidence that the amuletic use of these smaller Mithraic scenes was the conscious design of its original creator, rather than the subsequent deviance of various private owners: the close similarities between the Mithraic icon and a popular series of amulets against the evil eye (baskania), which was thought to be the palpable injury of human envy (phthonos or invidia) that occurred when a jealous person gazed upon a luckier or more beautiful one — a gaze that could bring bad luck, illness and even death.Footnote 27 The most familiar ancient amulet against the evil eye was an image of the ‘all-suffering eye’ (ho polupathês ophthalmos),Footnote 28 which appears, for example, on the early Byzantine medallion in Fig. 6.Footnote 29 A stylized eye sits at the centre of the composition surrounded by attackers: heraldic lions from the sides, an ibis, a snake and a scorpion from below, and three daggers from above. The encircling inscription reads: ‘Seal of Solomon, chase away every evil from the one who bears this!’ Some of these amulets show a trident or the club of Herakles hovering above the eye instead of knives.Footnote 30 On a carnelian gem in Rome we see a similar arrangement: on the sides and bottom a variety of animals — including a dog, a scorpion, some kind of bug or crustacean, and a turtle — while a thunderbolt of Zeus descends from the top.Footnote 31 On a similar chalcedony gem, a scorpion and snake threaten the eye from below, a lion and goat(?) from the sides, and from above a three-pronged thunderbolt and a military sword.Footnote 32

FIG. 6. An early Byzantine amulet for the evil eye. (Drawing after Schlumberger (1892), 75–6 no. 1)

A similar scene appears in larger dimensions on a roof-tile from the synagogue at Dura-Europos (Fig. 7).Footnote 33 Here we can easily make out the two snakes assaulting the sides of the eye, while some kind of beetle approaches from below and three blades or wedges are driven in from above, labelled successively with the vowels iota, alpha and omicron, which spell out the name Iaô, the usual Greek way of rendering the name of the Jewish god Jahweh, albeit with the common mistake of omicron for omega. The animals once again attack from the sides and below, while the god revered in the synagogue propels sharp weapons down from above.

FIG. 7. A roof-tile from the synagogue at Dura-Europos. (Drawing after du Mesnil (1939), fig. 96 no. 1)

A similar cast of characters populates a well-known relief from Britain (Fig. 8) that once sat at the entrance of an important building of the Severan period.Footnote 34 Here, again, animals threaten the eye from below — from left to right: a leopard or a lion, a snake, a scorpion, a crane and a raven — while two human figures abuse it from above: the one on the left (in a Phrygian cap with his back to the viewer) defecates upon the eyebrow, while another figure dressed in a gladiator's subligaculum stabs downwards into it with a trident, while brandishing a short sword in his left hand.Footnote 35 These two persons appear to exchange glances, but neither looks directly at the gigantic eye below.

FIG. 8. A relief from the entrance of a Severan building in Britain. (Drawing after Millingen (1821), 74 pl. 6)

Another important place for displaying the all-suffering eye is in floor mosaics near entrance-ways, for example, one found in the vestibule of a Roman house near Antioch-on-the-Orontes (Fig. 9).Footnote 36 In this version the animals are more numerous and attack from almost every direction; the centipede is a new addition and the dog catches our eye, because its posture and placement on the lower right recall the dog that jumps up at the Mithraic bull.Footnote 37 Weapons again descend from above and in this case they include a sword as well as a trident.Footnote 38 On the left a pipe-playing dwarf walks away from the eye, while his giant phallus emerges backwards from between his legs and joins in the assault;Footnote 39 the dwarf, however, has turned his body away and does not look at the scene behind him.

FIG. 9. Vestibule mosaic from a Roman house near Antioch-on-the-Orontes. (Photograph after Levi (1941), pl. 56 no. 121)

The motif of the all-suffering eye shows up often, then, on both house and body amulets. It is important to note, moreover, that none of these images gives us the impression that the eye is to be killed. This is most obvious in the case of the scorpion, which, as in the Mithraic scenes, almost always approaches the eye headfirst with its lethal tail flattened and pointed away.Footnote 40 The eye, in short, is wounded or harassed from all sides by a frightening array of animals and weapons, but it remains unblinking and unperturbed, much like the Mithraic bull, which usually shows no discomfort at the various attacks against it, despite the blood spurting from its shoulder. These amulets aim, in short, to threaten and confront the eye, but not to destroy it, a fact that underscores a common presumption underlying much apotropaic ritual in the ancient world: danger or sickness can be driven out, surrounded, bound up or buried, but can never be completely destroyed.Footnote 41 There is, moreover, a consistent internal logic to the placement of the attackers, despite great variations: gods or heroic figures with manufactured weapons (or the weapons alone) generally attack from above; terrestrial or winged animals from the side (e.g. dogs, felines and birds), and subterranean dwellers from below (e.g. snakes, scorpions or insects).

It should be clear by now that these evil-eye amulets provide helpful parallels for the organization of the Mithraic icon: in both the attackers are generally divided into two groups, the dangerous animals (i.e. ‘natural’ predators) that approach or lunge up from the sides or below, and the man-made weapons (i.e. ‘cultural’ predators) that descend from above and in a number of cases seem to be propelled either by a divine force, such as Jahweh or Zeus, or by a heroic one, such as Herakles or the gladiator on the relief in Britain, who jabs at the eye with his trident. We also saw similarities in the specific types of animals that attack the eye (the dog, the snake, the scorpion and a variety of birds) as well as their relative positions: the snake, scorpion and other non-mammals are usually placed below, the dog on the right side and the lion on the left. The main differences are: (i) the animals in the Mithraic scene attack a bull, not an eye; (ii) the types of animals and their relative positions on the larger communal images, at least, seem to have been fixed (snake, scorpion and dog); and (iii) in most of the larger versions the snake and the dog lick the blood that spurts from the wounded bull's shoulder, but the eye never bleeds. These differences are not so stark, however, when we take into account the smaller Mithraic monuments, like the Argive thunderstone or the gems discussed earlier, where we do find greater variation in the types of animals (the scorpion is often missing) and the snake and dog sometimes simply confront the bull, rather than lick the blood from his wound.

IV THE GODDESS NIKE AND THE BATTLEFIELD SPHAGION

In nearly every version of the iconic scene Mithras attacks the bull vertically from above with a short military sword or dagger, like those divine or heroic weapons that strike the evil eye from on high. And like the human figures in the evil-eye scenes, Mithras almost always averts his gaze from the object of his attack. His pose above the bull, however, is quite complicated: he kneels on the bull's back and pulls back its head, as if he is ready to slit its throat, a posture that was apparently borrowed from well-known scenes of the goddess Nike and the bull, such as on the third-century b.c. mirror cover from Megara illustrated in Fig. 10.Footnote 42 This scene is popular in the Classical period, rare in Hellenistic times and becomes fashionable again in the Roman Empire, especially during the reign of Trajan.Footnote 43 Some of the earliest versions of Nike and the bull are those carved in relief on the parapet of the fifth-century Athena Nike temple near the entrance of the Athenian acropolis, but we also find early examples of Nike killing smaller male animals in the same fashion on coins from the Greek East.Footnote 44 It seems, in fact, that in all of these representations Nike is performing a special kind of military ritual known as a sphagion, during which a single soldier on behalf of the army kills an uncastrated male animal just prior to a battle while facing the enemy or their territory.Footnote 45 Aside from the Nike scenes, it is only rarely illustrated in Greek art.Footnote 46

FIG. 10. A third-century b.c. mirror cover from Megara. (Drawing after Smith (1886), pl D)

The similarities in the poses of Nike and Mithras are most obvious in the manner in which both kneel on the back of the bull and wrench back its head, often placing their fingers into its nostrils. There are, however, two important differences: Nike either slits the bull's throat or more often, as we see in Fig. 10, is about to do so; in the earlier Greek versions, this is clear from the manner in which she grips the knife with the blade protruding between forefinger and thumb, ready for a horizontal slicing motion.Footnote 47 In the Mithraic scenes, on the contrary, the blade nearly always emerges from the opposite side of the god's fist, near the smallest finger, and is engaged in a vertically downward stroke. It is true that in Roman imperial reliefs Nike sometimes holds her weapon in the same manner as Mithras, as she leans over the head of the bull in order to stab it in the front of its throat,Footnote 48 but it is crucial to note that in every extant image the goddess seems to be going for the jugular. She is, moreover, always looking forward towards the bull's head or throat, rather than away like Mithras.

I suggest, then, that the Mithraic icon reflects two well-known designs: the popular image of Nike performing a battlefield sphagion and the equally popular image of the all-suffering eye. The combination of these two quite different scenes demanded some important alterations, however, most notably in the interaction of Mithras and the bull: the god does take the same position as Nike by placing his knee on the back of the animal and by pulling up its muzzle and baring its neck for the fatal blow. But that blow never comes and instead the god strikes the animal vertically in the shoulder. It seems, in fact, that the creator of the Mithraic image purposely altered the place of the sword's entry into the body, as well as its limited penetration, in order to align the god's attack with the downward and limited thrusts of the divine or heroic weapons at the top of the evil-eye amulets. The second important deviation from the Nike scenes is the direction of Mithras' gaze,Footnote 49 for in nearly every instance he looks away: sometimes he gazes at the back of the bull's head, but much more often out at the viewer or over his shoulder at the raven or Sol. This averted gaze of Mithras is odd, and when scholars look for parallels in narrative art, they usually cite the death of Medusa, in which Perseus, just as he kills her, has his head turned away in similar fashion to prevent any harm from befalling him, if he should happen to glance at her face.Footnote 50 We have, in fact, seen this same motif earlier in some of the evil-eye scenes, in which those anthropomorphic figures that attack the eye — for example, the ithyphallic dwarf in Antioch or the gladiator in Britain — do so without ever looking directly at the eye. In these non-Mithraic images, then, the attacker's gaze is averted from some deadly danger: the evil eye or the petrifying gaze of the Gorgon, in both instances to protect themselves from danger. I suggest that the usually turned-aside gaze of Mithras can be explained in the same manner. The two ways, then, in which Mithras deviates from the pose of Nike can both be explained as conscious alterations aimed at fitting the sphagion-scene more comfortably into the overall apotropaic design of the evil-eye amulets.

There are, however, two features of the bull-wounding scene that the amulets and Nike scenes cannot fully account for, but which both seem to be natural extensions of the logic of the sphagion-scene: the emphases on the bull's blood and on its genitals. In most of the monumental versions of the Mithraic icon, for example, the artist calls attention to the blood dripping or running from the wound by having the snake and the dog leap up to lick it, a detail that may, in fact, recall how the sphagion ritual focuses intently if not exclusively on the flow of blood from the victim.Footnote 51 The scorpion's emphasis on the bull's testicles, on the other hand, marks the animal as especially wild and dangerous, and therefore fit for a military sphagion (see the end of n. 45), rather than the typical domesticated animal that was usually castrated, while still young, and then at some later point sacrificed and eaten in communal sacrifice. The question remains, however, why these details are so exaggerated in the Mithraic scene. Some suggest, in fact, that the blood and testicles point to Mithras' essentially creative rôle in the cosmos and claim that by killing the bull the god releases the creative energy of life into the cosmos, a fact that is thought to be illustrated by the ears of wheat that sprout from the end of its tail. The eagerness of the animals to consume the blood of the bull is thus explained as a thirst for this newly released life-force.Footnote 52 It has not been noticed, however, that only animals of low or ambiguous status (the snake and the dog) lick the blood and, if we recall that the blood of the bull was believed to be a notorious poison in the Greco-Roman world,Footnote 53 might we come to the opposite conclusion, namely that the scene actually provides an aition for the existence in the world of venomous snakes or rabid dogs?

V SOME TENTATIVE CONCLUSIONS

The question arises, finally, of the historical relationship between the Mithraic icon and the evil-eye amulet. Already in the nineteenth century, some scholars independently noted these similarities and came to the opposite conclusion, namely, that the Mithraic monuments influenced the design of the evil-eye talismans.Footnote 54 They were able to make this claim because in those days scholars erroneously believed that the Mithraic cult practised in Roman times had evolved directly from much older Persian practices. In recent years, however, it has become apparent that the Roman cult probably originated in central Italy sometime in the second half of the first century a.d. and its connection with the Persian cult of Mithras is far less clear. Can we, then, argue for the opposite process, namely that the Mithraic icon imitates the evil-eye amulets? Unfortunately, the earliest examples of Mithras stabbing the bull in the shoulder date to the start of the second century a.d., at the same point in time when we also begin to find the motif of the all-suffering eye.Footnote 55 One cannot, in short, claim with any authority that one scene precedes the other historically, at least not from the available evidence.

Some scholars have suggested, however, that the Mithraic monuments evolved over time from a simple form with Mithras and the animals to the more complex monuments, like the one in Fig. 2, and that this evolution reflects ‘a kind of syncretism or conflation of symbolic elements’ that were added to the basic image of Mithras and the bull.Footnote 56 The central scene is thus understood as the most important image, while the surrounding materials are to be interpreted as ‘symbolic accretions’ or ‘variable additions’: first the internal audiences to the scene (the torchbearers, then the Sun and Moon above, and more rarely the Ocean and Earth below),Footnote 57 but especially the side-scenes ‘in ladders’ illustrating other vignettes of Mithras' life.Footnote 58 Elsner suggests, moreover, that the resulting ‘pleonism’ on the larger monuments ‘offers not only an oversignification of symbolic elements … but also the endless possibility of over-reading — for an excess in viewers’ interpretations'.Footnote 59 His impression dovetails nicely with those scholars who speak more generally of mixture and ad hoc invention in Mithraic cult and iconography, for example Gordon, who remarks: ‘the dominant impression is one of eclecticism. Whatever their ultimate origins — the Mysteries as a developed religion were constructed from ideas borrowed from different sources and mixed in a bricolage.’Footnote 60

This seems especially true of the sequence of side-scenes, some of which depict Mithras performing heroic labours like those of Heracles, Theseus or even deified athletes such as the famous Milo.Footnote 61 These scenes were once thought to illustrate (along with the bull-wounding scene) individual vignettes from some kind of sequential biography of Mithras, for example, the scenes of him cutting fruit, dragging the bull, shooting an arrow, or playing the rôle of Atlas.Footnote 62 But when counted individually these side-scenes are statistically rareFootnote 63 and never add up to a consistent Mithraic mythology or biography. They seem, in fact, to get attached to the sides of the icon by a somewhat random process of bricolage in order ‘to familiarize the unfamiliar Persian god and to assimilate him to the patterns of classical heroes’.Footnote 64 The central image of Mithras and bull, in short, was probably never part of any sacred biography, but rather it had some other, original meaning connected, I suggest, with its amuletic design. The side-scenes, on the other hand, were later and sporadic additions that perhaps attempt, albeit unsuccessfully, to create a narrative around this central image, a story of how Mithras, like Heracles, made the transition from an invincible conquering hero to a god.Footnote 65

Mithraic scholars have, for the most part, been fascinated by the complex, communal versions of the icon. This is only natural, of course, because there is so little textual data for Mithraic beliefs and one depends on the iconography alone to make sense of the cult and the ideas and beliefs that may lie behind it. In this essay, however, I have tried to ignore the peripheral images and to read the bull-wounding scene in isolation as a free-standing image. Gordon and Elsner have stressed for different reasons how this central scene departs from the norm of the Greco-Roman cult statue, which traditionally depicted a divine personality in repose. This change from a traditional cult-statue in the round to sculptural relief was, however, widespread in the religious art of the Roman imperial period:Footnote 66

In new cults such as those of Mithras, … such reliefs take over the role traditionally played by the cult statue. The idea of the god's salvific action in the world … was best conveyed through narrative … [and] narrative is best handled in relief form.

Elsner expresses the same idea differently, when he says that the central relief of Mithras and the bull ‘energized the static cult image by making the deity performative’, but in the end he finds it odd that ‘the ritual action is now the cult image and the worshipped deity his own worshipper’; he, too, concludes that ‘the sacrifice of the bull is salvific’, although he acknowledges that the scene differed greatly from the norms of Greco-Roman civic sacrifice.Footnote 67

I would agree with all of this, except the insistence that the ritual action of Mithras constituted some bizarre form of standard sacrifice, one that ended in a communal feast. This sense of radical innovation depends, as we have seen, on two long-standing, but erroneous assumptions: (i) that Mithras can kill the bull by striking it in the shoulder; and (ii) that in his actions Mithras is imitating a depiction of a normal sacrifice performed by Nike. But Mithras does not in fact aim to kill the bull nor does Nike sacrifice her bull for the usual communal meal. So when Elsner sums up the Mithraic icon by saying that ‘the sacrifice of the bull is salvific’,Footnote 68 I would alter two of his terms and assert instead that ‘the wounding of the bull is apotropaic’. By rejecting the idea of traditional sacrifice, moreover, we remove the peculiar self-reflexivity that has always troubled the traditional sacrificial interpretation, according to which ‘the god … performs the sacrifice instead of … being its recipient’.Footnote 69 In fact, a military sphagion did not require a god at all, for it operated automatically without any divine audience or recipient.

One final detail remains to be discussed. If, as now seems probable, the bull represents some danger or enemy that needs to be averted or contained, what threat was it? Given the notorious paucity of confessional or other kinds of Mithraic texts, I can only offer suggestions. The parallels with the scenes of military sphagion suggest, on the one hand, that the bull may have represented in some way or other dangers that many Mithraic worshippers faced in their quotidian military lives. The parallels with the evil-eye amulets, on the other hand, point in another direction that could be useful to all of the god's worshippers: the bull may represent some kind of persistent and unconquerable danger or disease that can be contained or harassed, but never conquered. Indeed, Gordon has stressed that in many of the peripheral narrative scenes Mithras imitates traditional culture heroes, like Heracles and Theseus, who make the world safer by conquering forces of mayhem and destruction, such as the Nemean lion or the bull of Marathon.Footnote 70 The bull, then, may represent some kind of generalized danger against which the god leads the attack.

Given the absence of any solid textual evidence for Mithraic myth and beliefs and given the wide variation in the images that crowd the periphery of the larger Mithraic icons, it is impossible to insist on a single interpretation for each monument that depicts Mithras and the bull. I will suggest nonetheless that, just as the roof-tile from Dura-Europos apparently protected the synagogue and its worshippers from envy by depicting Jahweh driving three blades down into the evil eye, the Mithraic icon functioned in a similar manner, except that it replaces Jahweh with Mithras and for envy substitutes some deadly danger represented by the bull. This same amuletic design would, of course, have been useful and usable for those who worried about astronomical or cosmic disasters as well. Indeed, given the evidence in the more complex Mithraic monuments for the creative reinterpretation and extrapolation of this icon along various astrological, cosmogonical or mythological vectors, it would be foolish to insist that it continued to be viewed throughout the Empire simply as an amulet to protect against bodily harm. But one can say this: because the iconic centrepiece remained essentially unchanged for at least two and a half centuries and because many of the miniature versions show only the central scene of Mithras and the animals, the protective power of this scene was always recognizable and therefore always available to individual male worshippers, not only when they gazed at the larger monuments during their communal ceremonies in the mithraeum, but also when they placed smaller versions in their homes or on their individual bodies.

APPENDIX A: EVIDENCE FOR THE SACRIFICIAL HYPOTHESIS

The sacrificial interpretation of the Mithraic icon was embraced by Cumont and others before him, but it rests on surprisingly shaky foundations, for example, on the claim that Nike and Mithras are both performing a traditional form of communal sacrifice on their respective bulls, an idea that no longer holds currency (see nn. 45–6 above). Another weak datum is the unique and fragmentary Latin inscription from the Santa Prisca mithraeum, of which only the words sanguine fuso can be securely read.Footnote 71 The only remaining argument for the sacrificial nature of the icon is important: its apparently special affinity with another scene occasionally found in the mithraea, that of the banquet of Sol and Mithras seated on a bull-skin. In the past scholars have interpreted this banquet as the next vignette in the mythical adventures of Mithras, after the ‘slaying’ of the bull.Footnote 72 It is indeed clear that in a handful of mithraea the banquet-scene (unlike the other side-scenes) did have some special relationship with the icon, because the banquet scene is occasionally engraved on the back of reliefs of Mithras-and-the-bull; the two-faced stones were apparently designed to be swivelled or otherwise reversed.Footnote 73 Thus it appears that in a few Mithraic sanctuaries the scene of Mithras and the bull was turned around at certain times of the year and replaced for some interval of time by the feasting scene on the bull-skin. Thus it may well be that in some Mithraic communities, at least, the iconic scene was closely connected in the minds of some worshippers with the banquet scene. Here, then, is a good case for local bricolage. But within the rich data-set of Mithraic monuments this variation is statistically rare and probably tells us more about a few epichoric attempts to reinterpret the icon as a sacrificial scene, than a widespread Mithraic understanding of the scene as a sacrifice.

APPENDIX B: LIST OF GEMS OR AMULETS DEPICTING MITHRAS AND THE BULL

1. Argive thunderstone (scene oriented right) with only Mithras (facing forward; stabs at throat over bull's head), animals (dog, snake, bird on bull's foreleg; no blood-licking) and two magical words (CIMRM 2353 = Mastrocinque, op. cit. (n. 16), no. 2).

2. Red jasper in Florence with full scene on obverse (oriented left): Mithras (facing outwards; stabs at throat over bull's head), bull (facing him), animals (dog, dolphin, turtle; no blood-licking), torchbearers, Sol/Luna, weapons and birds above. Reverse: lion walking left; above seven stars, each encircled by a magical word (CIMRM 2354).

3. Yellow carnelian with full scene (oriented left): Mithras (facing outwards; stabs at throat over bull's head), bull (facing him), animals (dog, dolphin, turtle; no blood-licking), torchbearers, Sol/Luna, weapons and birds above — no inscription. It is nearly identical with No. 2, except the reverse is blank — it has no magical words (CIMRM 2355).

4. Half of a broken yellow jasper (scene oriented right) with only Mithras (facing backward; stabs at bull's shoulder) and the animals (at least one bird and the scorpion); on reverse Eros and Psyche with magical names connected with erotic magic, e.g. Neixaroplêx, and iaeô-palindrome on bezel (CIMRM 2356 = Mastrocinque, op. cit. (n. 16), no. 4).

5. Jasper (colour not recorded) with Mithras and bull, with dog, snake and raven (no scorpion) and only one torchbearer on the right, who is animal-headed; seven stars in the background; on the reverse magical names, Neixaroplêx, and Iaô and Asôniêl on the bevel (Delatte, op. cit. (n. 16), 12–13 = CIMRM 2359 = Mastrocinque, op. cit. (n. 16), no. 5).*

6. Red and green jasper with Helios in his chariot and magical words (ablanathanalba and tukseui) on obverse; on reverse (scene oriented right) a standing Mithras stabs a standing bull with no others present (CIMRM 2361 = SMA 71 = Mastrocinque, op. cit. (n. 16), no. 3).*

7. Rock crystal (scene oriented right) with only Mithras (facing forward with three stars on his cloak; stabs at shoulder) and animals (dog, snake, scorpion) — no inscriptions (CIMRM 2362 = Gordon, op. cit. (n. 4), fig. 17).

8. Yellowish chalcedony (scene in grotto oriented right) with Mithras (facing forward; stabs at shoulder), animals (raven on cloak, dog, snake, scorpion), one torchbearer (holds two torches), and Sol/crescent moon above — no inscriptions (CIMRM 2363).

9. Hematite rectangle (scene oriented left) with Mithras (facing backward; stabs at throat over bull's head), animals (long-eared dog, snake, scorpion, bird; no blood-licking), Sol/Luna, two altars (replacing torchbearers), and bird behind Mithras (raven?); on reverse anguipede with Iaô inscribed inside of shield (CIMRM 2364 = SMA 68 = Mastrocinque, op. cit. (n. 16), no. 6).

10. Half of a broken black jasper (scene oriented right) with Mithras (facing backward; stabs at shoulder), animals (dog, snake, scorpion; no blood-licking), and one torchbearer (presumably one of a pair); near Mithras' radiant crown perhaps the end of the name of the Egyptian sun-god Re ([Ph]rên); on back the magical palindrome ablanath[analba] (CIMRM 2365 = SMA no. 69 = Mastrocinque, op. cit. (n. 16), no. 9).

11. Greenish-black jasper (scene oriented left) with Mithras (facing forward; knife lifted over bull's head), animals (dog at bull's throat, snake, scorpion approaches from behind with bird above; no blood-licking), and seven stars — no inscriptions; on reverse a Cabirus with hammer (CIMRM 2366 = SMA no. 70 = Mastrocinque, op. cit. (n. 16), no. 10).

12. Unspecified gem from Nemea (scene in grotto oriented left) with Mithras (facing forward; knife lifted over bull's head), animals (dog, snake; no blood-licking), seated and mourning torchbearers, and Sol/Luna — no inscriptions (CIMRM 2367 = Gordon, op. cit. (n. 4), fig. 18).

13. Red and green jasper (scene oriented left) with Mithras (facing backward), animals (dog, snake, scorpion, raven), torchbearers, and Sol/Luna; on reverse a nonsense inscription: Kênao/asaga (TMM 2 no. 8 = Mastrocinque, op. cit. (n. 16), no. 11).

14. Brownish-red jasper from Carnuntum (scene in grotto oriented left) with Mithras (facing backward; stabs shoulder), animals (dog, snake, scorpion; no blood-licking), mourning torchbearers, Sol/Luna and small altar in front of bull — no inscriptions (CIMRM 1704 = D. Schön, Orientalische Kulte im römischen Österreich (1988), no. 35).

15. Cornelian from Carnuntum, no photograph, but according to the description: Mithras kneels on bull inside grotto with sword about to strike; snake and raven only; no torchbearers; seven stars and crescent moon across the top of the grotto's ceiling — no inscription (Schön, op. cit. (1988), no. 36).

16. Dark red jasper from Viminacium (scene oriented left) with Mithras (facing forward; knife in bull's head or neck), animals (dog before bull's chest, snake and scorpion below; bird above bull's head; no blood-licking), torchbearers, and Sol/Luna — no inscriptions. The reverse is blank (E. Zwierlein-Diehl, Die antiken Gemmen des Kunsthistorischen Museums in Wien vol. 2 (1979), no. 1376).

17. Orange carnelian ringstone (scene oriented left) with only Mithras (facing forward; stabs shoulder) and snake (no blood licking) — no inscriptions (AGDS Munich 1.3 no. 2654).

18. Heliotrope (scene oriented left) from a ring found in a medieval grave with full scene in grotto with canonical animals and blood-licking, torchbearers, raven, Sol, Luna, krater and seven stars — no inscriptions (Gordon, op. cit. (n. 4), fig. 19).