Introduction

People constantly negotiate different social meanings such as their identities, roles, and interpersonal relationships. These social meanings are expressed not solely through words and syntactic and grammatical choices, but also through prosodic, gestural, and body signals, which are considered to be key features of pragmatic communication in adults (see, e.g., Kelly, Barr, Breckinridge Church, & Lynch, Reference Kelly, Barr, Breckinridge Church and Lynch1999, for gesture; Prieto, Reference Prieto2015, for prosody). For example, a seemingly polite request such as “Can you open the window” can be intended or interpreted as impolite depending on the tone of voice and the gestural features accompanying it. Pragmatic politeness theories assume a correlation between indirectness and politeness (e.g., Brown & Levinson, Reference Brown and Levinson1987; Leech, Reference Leech1983), and most empirical work centres on issues of indirectness; however, the focus has been clearly on the lexical and morphosyntactic markers used to signal indirectness and only more recently on prosodic and gestural cues (Brown & Winter, Reference Brown and Winter2018; Brown, Winter, Idemaru, & Grawunder, Reference Brown, Winter, Idemaru and Grawunder2014; Hübscher, Borràs-Comes, & Prieto, Reference Hübscher, Borràs-Comes and Prieto2017; Winter & Grawunder, Reference Winter and Grawunder2012). More particularly, Brown and Levinson's (Reference Brown and Levinson1987) theory predicts a certain interaction between the dimensions of the social context and the use of face redress strategies, whereby more face-saving strategies will need to be used to make requests of people who have more power or greater social distance, and the same will be true of requests intended to show a higher degree of imposition or cost to the ‘face’ of the person who receives the request. While this theory has not been shown to hold cross-linguistically, since not in every culture is there a direct association between politeness and avoidance of imposition (Sifianou, Reference Sifianou1993; Terkourafi, Reference Terkourafi2015), in the context of Catalan, the language which will be investigated in this paper, this association does indeed hold (Astruc, Vanrell, & Prieto, Reference Astruc, Vanrell, Prieto, Armstrong, Henriksen and Vanrell2016; Fivero, Reference Fivero1976; Hübscher et al., Reference Hübscher, Borràs-Comes and Prieto2017; Payrató & Cots, Reference Payrató and Cots2011).

According to this framework, then, children in the process of acquiring their native language need to learn not only what certain speech cues signal about the social context but also how to combine various linguistic elements into coherent styles. This sort of attunement to social relations is a cognitive trait of humans which guides children's understanding of communication from an early age. The ability to recognise and then communicate politeness is therefore going to be a clear manifestation of a child's socio-cognitive development.

In this regard, surprisingly little is known about the role that gesture and prosody play in children's developing use of politeness. Research on the acquisition of politeness phenomena has usually focused only on verbal means, such as polite words, mitigating lexical cues, and honorific markers (see, e.g., Aronsson & Thorell, Reference Aronsson and Thorell1999; Axia & Baroni, Reference Axia and Baroni1985; Bates, Reference Bates1976; Bernicot & Legros, Reference Bernicot and Legros1987; Ervin-Tripp & Gordon, Reference Ervin-Tripp, Gordon and Schiefelbusch1986; Georgalidou, Reference Georgalidou2008; Hollos & Beeman, Reference Hollos and Beeman1978; James, Reference James1978; Nakamura, Reference Nakamura1999; Nippold, Leonard, & Anastopoulos, Reference Nippold, Leonard and Anastopoulos1982; Read & Cherry, Reference Read and Cherry1978; Ryckebusch & Marcos, Reference Ryckebusch and Marcos2004), while ignoring gestural and prosodic strategies. By contrast, studies on the role of gesture and prosody in language development have hardly ever explored the signalling of polite stance (see Goodwin & Goodwin, Reference Goodwin, Goodwin and Duranti2001; Goodwin, Goodwin, & Yaeger-Dror, Reference Goodwin, Goodwin and Yaeger-Dror2002; Matoesian, Reference Matoesian2005, for exeptions). Clearly, observations that fail to analyse verbal and non-verbal cues together will provide an incomplete picture of polite stance. Furthermore, as we will see below, there are sound empirical reasons to hypothesise that non-propositional strategies involving gesture and prosody pave the way for propositional pragmatic marking in children's socio-pragmatic development.

To test this hypothesis, the present study investigates preschool children's use of multimodal indexing (i.e., prosodic, gestural, body, and lexical/morphosyntactic markers) of the expression of politeness, and the role that such indexing plays in their developmental process. First, however, let us review the literature on the scaffolding role of gesture and prosody in the acquisition of language, and then summarize what previous research has said about children's acquisition of politeness.

Previous work on the impact of gestures and prosody on language acquisition

Gesture has been shown to play a scaffolding role in early language acquisition. Before uttering their first words, infants use a repertoire of gestural signals with communicative functions. For example, a child may express his/her emotions through different facial expressions, direct attention to objects through the use of eye-gaze and pointing gestures, and wave in order to greet or negate by shaking his/her head (Bates, Benigni, Bretherton, Camaioni, & Volterra, Reference Bates, Benigni, Bretherton, Camaioni and Volterra1979; Bates, Camaioni, & Volterra, Reference Bates, Camaioni and Volterra1975; Guidetti, Reference Guidetti2002, Reference Guidetti2005). This repertoire expands over the second year of life as more gestures appear with different representational and pragmatic properties, such as using an empty hand to mean ‘open’ or ‘give’. A number of studies have also demonstrated that children's gestures can serve as predictors of their subsequent language acquisition, mainly focusing on the facilitating role of gesture in acquiring the symbolic nature of language and syntax. For example, children's progress in the use of pointing gestures typically anticipates progress in their spoken language, thereby predicting the size of their lexicon (Acredolo & Goodwyn, Reference Acredolo and Goodwyn1985; Brooks & Meltzoff, Reference Brooks and Meltzoff2008; Carpenter, Akhtar, & Tomasello, Reference Carpenter, Akhtar and Tomasello1998; see Colonnesi, Stams, Koster, & Noom, Reference Colonnesi, Stams, Koster and Noom2010, for a review), as well as its content (Iverson & Goldin-Meadow, Reference Iverson and Goldin-Meadow2005). Sansavinia et al. (Reference Sansavinia, Bello, Guarini, Savini, Stefanini and Caselli2010) investigated longitudinally the early development of gestures, object-related actions, word comprehension, and word production in Italian-acquiring infants from 10 to 17 months and found that they all increased significantly from 10 to 12 months, with gesture developing earlier than object-related actions, and word production developing from age one. They also detected that gestures supported the emergence of verbal abilities, while object-related actions developed in parallel with word comprehension. By the same token, gesture has been found to be a predictor of the transition to multiword speech. At around 17 months, children start to produce supplementary deictic gesture–speech combinations (in which word and gesture convey different but related concepts), and two-word combinations emerge about four months later. Gesture–word ‘sentences’ such as saying “Mummy” (the argument of the sentence) while pointing to a chair (the predicate) to ask their mother to sit down appear several months before children can form the same construction entirely in speech (“mummy sit”) (Capirci, Contaldo, Caselli, & Volterra, Reference Capirci, Contaldo, Caselli and Volterra2005; Iverson & Goldin-Meadow, Reference Iverson and Goldin-Meadow2005; Özçalişkan & Goldin-Meadow, Reference Özçalişkan and Goldin-Meadow2005, Reference Özçalişkan and Goldin-Meadow2009). The number of representational gesture–word or two-word combinations that a child can use at 18 months predicts the complexity of the sentences they produce two years later, at 42 months (Rowe & Goldin-Meadow, Reference Rowe and Goldin-Meadow2009).

While most research has primarily focused on children's early production of representational, deictic, and conventional gestures and their precursor role in lexical acquisition, less is known about the role of gestures in the acquisition of pragmatic functions, and politeness in particular. There are some relevant studies, mostly of a longitudinal nature, which have explored the interplay between gesture and the ways in which children establish meaning in language. Investigating children's agreement and refusal messages, Guidetti (Reference Guidetti2005), Beaupoil-Hourdel, Morgenstern, and Boutet (Reference Beaupoil-Hourdel, Morgenstern and Boutet2015), and Benazzo and Morgenstern (Reference Benazzo and Morgenstern2014) found that the gestural modality was operational before the verbal modality, with children using conventional gestures such as a head shake and a head nod to convey negation and affirmation before they learned to use the corresponding lexical items. Also, a number of studies have looked at the relationship between gesture and speech in narrative development, investigating the new types of gestures which appear as children grow (Colletta & Pellenq, Reference Colletta, Pellenq, Nippold and Scott2004; McNeill, Reference McNeill1992), such as beats (rhythmic gestures), metaphoric gestures (gestures that express abstract concepts), and discourse cohesion gestures (gestures that accompany connectives; see Kendon, Reference Kendon2004). These studies argue that the pragmatic function of such gestures is to help children negotiate aspects of situational embedding by transmitting attitudes, different levels of attention, and agreement between participants in an interaction, or to break apart speech into different information packages or turns, thereby directing the organisation of a discourse. Surprisingly little is known, however, about if and how children use gestures and other body cues to signal their (polite) stance, and whether those signals act as a predictor of the onset milestones in children's socio-pragmatic development.

In addition to gesture, prosody has also been ascribed an important role in children's language development. First and foremost, language acquisition research has shown that prosody acts as a kind of syntactic bootstrapper. That is, certain types of prosodic features have been shown to guide children's initial acquisition of word order and syntactic structures (for a conceptualisation, see Hirsh-Pasek, Tucker, & Golinkoff, Reference Hirsh-Pasek, Tucker and Golinkoff1996; see also Christophe, Nespor, Guasti, & Van Ooyen, Reference Christophe, Nespor, Guasti and Van Ooyen2003). Furthermore, recent evidence stemming from an experimental study looking at the ways in which children develop an understanding of another speaker's uncertain knowledge state suggests that prosody and gesture might play similar bootstrapping roles in giving children access to pragmatic meaning before they comprehend the relevant lexical cues (Hübscher et al., Reference Hübscher, Borràs-Comes and Prieto2017).

With regard to production, prosody has also been shown to play an important role in a child's pragmatic language development. Between the ages of 7 and 11 months, infants make prosodic distinctions in their communicative versus investigative vocalisations (Papaeliou & Trevarthen, Reference Papaeliou and Trevarthen2006), and are also able to make prosodic (and gestural) distinctions in their intentions at 12 months (Esteve-Gibert, Liszkowski, & Prieto, Reference Esteve-Gibert, Liszkowski, Prieto, Armstrong, Henriksen and Vanrell2016). Specifically, for vocalisations that require something of their caretaker (e.g., requests and expressions of discontent), infants produce vocalisations with a wider pitch range and longer durations (Esteve-Gibert & Prieto, Reference Esteve-Gibert and Prieto2013). A series of case studies investigating longitudinally the emergence of prosody in pragmatic contexts (Dodane & Martel, Reference Dodane and Martel2009a, Reference Dodane and Martel2009b; Martel & Dodane, Reference Martel and Dodane2012) have reported a similar tendency. For example, Dodane and Martel (Reference Dodane and Martel2009b) found that an infant's prosodic production is affected by the particular communicative situation. Specifically, infants vary intonation depending on whether they are addressing an interlocutor or not, and do so even before they produce their first words, illustrating the role of prosody as a precursor in children's early communication. Other research has shown that between the one- and two-word stage infants can produce adult-like intonation contours that are pragmatically appropriate for different situations (Chen & Fikkert, Reference Chen and Fikkert2007; Frota, Matos, Cruz, & Vigário, Reference Frota, Matos, Cruz, Vigário, Armstrong, Vanrell and Henriksen2016; Prieto, Estrella, Thorson, & Vanrell, Reference Prieto, Estrella, Thorson and Vanrell2012), pointing to an early acquisition of the speech act meaning of intonational contours, along with the above outlined early ability to convey intentionality through prosodic cues.

Yet, depending on the pragmatic meaning encoded through intonation, the production of certain contours may take longer to develop than others. While the production of acoustic correlates of stress seems to be acquired between ages two and three (see, e.g. Furrow, Reference Furrow1984; Hornby & Hass, Reference Hornby and Hass1970), according to the literature other pragmatic uses of intonation are in place only later in development, due to cognitive and social constraints. For example, expression of belief states or politeness involve more complex cognitive skills and thus have been found to develop only after age three (Esteve-Gibert & Prieto, Reference Esteve-Gibert, Prieto, Esteve-Gibert and Prieto2018). However, thus far no research has explored whether and how children use prosody as they develop an ability to express politeness, and also whether prosody might work as a facilitating device in that process.

Even though prosody and gesture have been mostly studied separately, there is increasing evidence from studies on adults that the marking of socio-pragmatic meanings, such as in epistemic information, politeness, and information status marking, can be considered as two sides of the same coin (see Brown & Prieto, unpublished observations). There is also increasing evidence in development that demonstrates that prosody and gesture seem to be much more related than previously assumed (Esteve-Gibert & Guellaï, Reference Esteve-Gibert and Guellaï2018), yet due to the fact that most previous studies have investigated these meanings separately, it is not clear whether these modalities develop at the same time.

Children's acquisition of politeness

In language socialisation theory, politeness is generally considered a type of affective stance, with ‘polite’ affective stances conveying notions like formality, respect, and deference. Although research on how children learn to produce gestural and prosodic cues has started to investigate the role of such cues in the acquisition of pragmatic meanings, there is a clear lack of research on the development of politeness stance. Politeness is a complex issue in language use, especially for children. In order to make appropriate use of politeness, children must not only know what forms are used but also take into consideration pragmatic conditions such as social distance, unequal power, and the cost to the interlocutors’ ‘face’ of the interaction. It is thus not surprising that the literature on children's acquisition of language reports that the acquisition of politeness signalling is a protracted process and the general ability to employ polite speech which involves more conventionalized adult targets is not acquired until age five or older (Baroni & Axia, Reference Baroni and Axia1989; Nippold et al., Reference Nippold, Leonard and Anastopoulos1982; Pedlow, Sanson, & Wales, Reference Pedlow, Sanson and Wales2004). Be that as it may, children are usually socialised early into politeness routines. Adults generally support children's conversational contributions by providing a model and by scaffolding children's performance (see, e.g., Morgenstern, Reference Morgenstern and Fäcke2014). Interactional routines have been shown to play an especially important role in managing face-work, and are often specifically modelled for children by adult interlocutors, who have more socio-pragmatic expertise (e.g., Gleason, Perlmann, & Greif, Reference Gleason, Perlmann and Greif1984). Research on the acquisition of politeness has studied intensively how children are socialised in politeness routines at an early age, by exposure in English, for example, to verbal forms such as thank you, please, and I'm sorry (Gleason & Weintraub, Reference Gleason and Weintraub1976; Greif & Gleason, Reference Greif and Gleason1980). Similarly, Kaluli-speaking children in Papua New Guinea are taught to use appropriate forms of address (Schieffelin, Reference Schieffelin1990), Cakchiquel-speaking children in Guatemala are taught to perform end-of-the-meal routines, and Japanese children are taught how to bow (Nakamura, Reference Nakamura, Shirai, Kobayashi, Miyata and Nakamura2002). As a result, by age three children in all culture groups already have a good grasp of the sociolinguistic function of greetings, polite expressions, and formal language (Nakamura, Reference Nakamura1999, Reference Nakamura, Nakayama, Mazuka and Shirai2006). In a separate study looking at children's ability to understand linguistic register, Wagner, Vega-Mendoza, and Horn (Reference Wagner, Vega-Mendoza and Horn2014) found that children at age three were already able to access formal/polite speech in Spanish by linking the register to the corresponding addressee when they had sufficiently strong cues, whether social or linguistic (such as pronouns). These results similarly showed that when such cues to register were produced consistently children were able to access this knowledge earlier.

Other studies exploring children's acquisition of politeness have focused on speech acts and more particularly on directives like requests, commands, and orders. The ability to handle requests is of key importance in conversational competence, especially in a developmental context in which the child speaker needs to interact with interlocutors who represent different conditions of social distance and power. Previous research has examined children's use and understanding of politeness in requests in various languages, including English (Axia & Baroni, Reference Axia and Baroni1985; Bates, Reference Bates1976; Bernicot & Legros, Reference Bernicot and Legros1987; Ervin-Tripp & Gordon, Reference Ervin-Tripp, Gordon and Schiefelbusch1986; James, Reference James1978; Nippold et al., Reference Nippold, Leonard and Anastopoulos1982; Read & Cherry, Reference Read and Cherry1978), French (Ryckebusch & Marcos, Reference Ryckebusch and Marcos2004), Greek (Georgalidou, Reference Georgalidou2008), Japanese (Nakamura, Reference Nakamura1999), Swedish (Aronsson & Thorell, Reference Aronsson and Thorell1999), Norwegian and Hungarian (Hollos & Beeman, Reference Hollos and Beeman1978), and Turkish (Uçar & Bal, Reference Uçar and Bal2015). Generally, results show that children use mainly direct request strategies in early childhood and that the ability to tailor their language in order to take into account a listener's age and status and the cost of the exchange starts around ages four or five.

One of the most complete studies of this issue is Bates (Reference Bates1976). First, looking at the spontaneous production of requests in Italian-speaking children, she found that there were three main phases. Until about age four, children mainly used direct questions and imperatives as requests. Then, from ages five to six they acquired all the syntactic forms needed to produce requests, but were not yet very skilled at modulating them. Later, by age seven, they were able to vary both the form and the content of their requests using expressions such as please or a softer tone of voice to make their requests more polite. Furthermore, Bates was also interested in children's ability to judge how polite a request was. However, the children struggled to recognise the difference between interrogative and imperative forms until age five. Similar results were also found by Nippold et al. (Reference Nippold, Leonard and Anastopoulos1982) for English-speaking children.

Focusing on the social rules behind the choices of polite forms, Axia and Baroni (Reference Axia and Baroni1985) investigated whether children varied their requests on the basis of cost. In their experiment, children aged five, seven, or nine made repeated requests to adult interlocutors. Whenever the adult judged a request to be insufficiently polite, they did not respond. For all three age groups, the adult intentionally ignored every request that was made for the first time (a refusal to respond increases the ‘face’ cost to the requester of a subsequent request). In their second, reiterated requests, five-year-olds rarely knew how to make their request more polite, while seven-year-olds were somewhat more adept at this and nine-year-olds much more so, because they knew how to add mitigators like please and fall back on question forms or the conditional tense.

Using a similar approach, Read and Cherry (Reference Read and Cherry1978) instructed English-speaking four-year-olds to make requests of the Cookie Monster until their request was accepted. They observed that, after being turned down twice, the children produced more indirect requests and politeness markers. However, the politeness marker please often conflicted with the tone of voice of the request (shouting). Thus, the children seemed to be aware that they needed to change tactics, but were not able to match their morphosyntactic strategy with the intonation they applied. Taken together, these studies suggest that children start to recognise relatively early (between three and four years) that certain strategies such as please are used in order to be polite, but the ability to produce appropriate politeness strategies spontaneously seems to develop only slowly.

However, in a recent study we investigated children's sensitivity to non-propositional cues to politeness (Hübscher, Wagner, & Prieto, Reference Hübscher, Wagner and Prieto2016). Thirty-six three-year-old American English-speaking children performed a forced-choice decision task which investigated whether they were able to interpret pitch and facial expression as cues to a speaker's polite stance in audio-only, visual-only, or audio-visual presentation modalities, when lexical cues were controlled for. The results showed that at that age children infer a speaker's polite stance equally well in all three conditions; and then this suggests that intonation and facial cues do indeed serve children as strong cues to a speaker's polite stance in requests.

Summarising, previous research on children's acquisition of politeness is characterised by a main focus on the lexical/morphosyntactic indexes of politeness meaning, and in very few cases is tone of voice/intonation analysed (see Bates, Reference Bates1976; Hübscher et al., Reference Hübscher, Wagner and Prieto2016; Read & Cherry, Reference Read and Cherry1978). There is also a surprising gap in the literature regarding how children learn to produce gestural and postural signals of politeness, the exception being Goodwin et al. (Reference Goodwin, Goodwin and Yaeger-Dror2002). Using a conversation analysis approach, these authors investigated children's multimodal expressions of disagreement in disputes and found that turn shape, intonation, and body positioning were all critical to the construction of stance. The use of prosody by children to express politeness has likewise been relatively neglected in previous studies. Importantly, the results of Hübscher et al.'s (Reference Hübscher, Wagner and Prieto2016) study point to a potentially important role for prosody and non-verbal cues in the marking of early politeness stance in children, and it is this issue which constitutes the central research question of the present study.

Prosody and non-verbal signals in the expression of politeness in adult speech

Research on adults gives some insight into both prosodic and non-verbal cues in producing politeness-related meanings. Though early studies claimed that the perception of politeness increased with pitch range and pitch height (see Ohala's, Reference Ohala1984, Frequency Code hypothesis), this evidence has recently been contested. While it is true that in certain languages a high pitch range tends to be perceived as more polite (Chen, Gussenhoven, & Rietveld, Reference Chen, Gussenhoven and Rietveld2004, for Dutch and English), in other languages such as Korean (Winter & Grawunder, Reference Winter and Grawunder2012) and also Catalan politeness seems to be associated with a somewhat lower, not higher, mean pitch (Hübscher et al., Reference Hübscher, Borràs-Comes and Prieto2017). In addition to pitch, the importance of prosodic/acoustic correlates such as speech rate (Hübscher et al., Reference Hübscher, Borràs-Comes and Prieto2017; Lin, Kwock-Ping, & Fon, Reference Lin, Kwock-Ping and Fon2006; Ofuka, McKeown, Waterman, & Roach, Reference Ofuka, McKeown, Waterman and Roach2000; Ruiz Santabalbina, Reference Ruiz Santabalbina, Cabedo Nebot, Aguilar Ruiz and López-Navarro2013; Winter & Grawunder, Reference Winter and Grawunder2012), intensity, and voice quality (Hübscher et al., Reference Hübscher, Borràs-Comes and Prieto2017; Ito, Reference Ito2004; Winter & Grawunder, Reference Winter and Grawunder2012) have also been pointed out. Most importantly for the present study, adult Catalan speakers have been found to display a prosodic mitigation strategy that involves decreasing the rate and intensity of their speech and displaying less jitter and shimmer to communicate politeness in situations where the power distance between speakers is high (Hübscher et al., Reference Hübscher, Borràs-Comes and Prieto2017). Furthermore, in their investigation of how politeness is encoded through intonation in adult Catalan speakers, Astruc et al. (Reference Astruc, Vanrell, Prieto, Armstrong, Henriksen and Vanrell2016) found that both the cost of the action and social distance had significant effects on intonation choices. While high-cost situations triggered more rising pitch patterns than did low-cost situations, power distance did not have a significant effect on the choice of intonation contour.

Regarding non-verbal behaviour, a small number of studies have shown that a range of mitigating gestural behaviours are often employed to express politeness-related meanings. Mitigation has been associated with face-preserving efforts, which can also involve politeness (Briz, Reference Briz2002, p. 21). In American English, it has been shown that a range of mitigating gestural behaviours are often employed to signal politeness, such as a pleasant facial expression, raised eyebrows, a direct body orientation, or a tense, closed posture with small hand gestures, accompanied by a softer voice, touch, and close proximity. In contrast, aggravating behaviours include greater distance, an indirect body orientation, unpleasant facial expressions, lowered eyebrows, a loud voice, and wide gestures (Tree and Manusov, Reference Tree and Manusov1998). Since lexical epistemic (uncertainty) markers have often been mentioned in the context of hedging in order to lessen the face-threat, the detailed description of the non-verbal correlates of uncertainty/doubt markers offered by Givens (Reference Givens2001) is of considerable value. His report includes facial expressions (eyebrow frowns, eye-movements, lip-pouting, lip-pursing), head movements (headshakes, head tilts), and cues like adaptors,Footnote 1 palm-up open hand gestures, and shoulder shrugs.

Research in social psychology has revealed that power is communicated non-verbally through behaviours implying strength, comfort-relaxation, and fearlessness, whereas submissiveness is communicated through behaviours implying weakness, smallness, discomfort, tension, and fearfulness (Mehrabian, Reference Mehrabian1981, p. 47). When the social difference is high between interlocutors, powerful individuals typically adopt an expansive posture, speak loudly, lower their eyebrows, gaze directly at their social partners when speaking, nod more, use fewer self-touches, make more arm and hand gestures, shift their position more frequently and thereby show less body relaxation, and stand closer. In comparison, less powerful individuals typically have a hunched posture, speak quietly, raise their eyebrows, and vary their gaze (for reviews, see Ellyson & Dovidio, Reference Ellyson, Dovidio, Ellyson and Dovidio1985; Hall, Coats, & LeBeau, Reference Hall, Coats and LeBeau2005). Similarly, in high-power distance situations involving Korean speakers, the interlocutor of inferior status shows deference by a direct orientation of the body and constrained posture, and by suppressing gestures and touching. By contrast, in situations of low-power distance in Korean, body positioning is more relaxed and there are more gestures and touching (Brown and Winter, Reference Brown and Winter2018).

While there is not much literature on the cultural norms regulating the use of manual gesture, in many cultures a pointing gesture realised with an index finger extended is considered rude in anyone other than a small infant. A study carried out in Poland confirmed that, among Poles, as language acquisition continues, the pointing gesture, particularly when directed at people, begins to be perceived as inconsistent with Polish cultural norms and is often suppressed (Jarmołowicz-Nowikow, Reference Jarmołowicz-Nowikow, Müller, Cienki, Fricke, Ladewig, McNeill and Bressem2014). Similar observations have been made in relation to perceptions about certain ways of pointing among the Yoruba (Ola Orie, Reference Ola Orie2009). Taken together, these results suggest that prosody and gesture merit careful scrutiny in any investigation of how children develop an awareness of polite stance marking.

Present study

To our knowledge, no study so far has explored the early production of lexical and morphosyntactic strategies concurrently with the emergence of prosody, gesture, and body signals in the expression of polite stance from a developmental perspective. In the current cross-sectional study, we proposed to fill this gap by exploring the temporal link between gestural, body, prosodic, and lexical/morphosyntactic representation in young (aged three to five) Catalan-speaking children's multimodal indexing of polite stance in request situations. In particular, we wished to examine: (1) if and how young children mitigate their requests depending on the social parameters of social distance and cost; (2) whether children use prosodic and gestural and other body strategies earlier and more predominantly than lexical and morphosyntactic strategies; and (3) whether differences between a younger age group (3;0–4;6) and an older age group (4;6–5;0) reflect different stages of socio-pragmatic development. To do this, we conducted a request production task in which children were pragmatically induced to ask for a certain object and in which we varied the variables of social distance and cost. In the social distance dimension, in two of the situations the children were prompted to request an object from an experimenter (high social distance) and in the other two situations they were prompted to request something from a peer (low social distance). We also manipulated the context so that in one situation the cost of the request to the child would be low and in the other it would be high. Basing this on previous literature which reports an early facilitation role for gesture (see Colonnesi et al., Reference Colonnesi, Stams, Koster and Noom2010 for a meta-analysis) and prosody in the expression of intentionality (Sakkalou & Gattis, Reference Sakkalou and Gattis2012), speech acts (Esteve-Gibert, Prieto, & Liszkowski, Reference Esteve-Gibert, Prieto and Liszkowski2017), and contrast resolution (Ito, Jincho, Minai, Yamane, & Mazuka, Reference Ito, Jincho, Minai, Yamane and Mazuka2012), we hypothesised as follows: (1) these children would mitigate their requests in different ways depending on the degree of social distance between interlocutors and degrees of cost; (2) the children would more predominantly mitigate by means of prosodic, gestural, and other body signals compared to lexical and morphosyntactic markers to mark politeness; and (3) the children's repertory of mitigation strategies to signal politeness would expand over the preschool years in terms of not only lexical and morphosyntactic but also prosodic, gestural, and body markers.

Methodology

Participants

An initial group of 92 three- to five-year-old children were recruited for participation in the cross-sectional study from four Catalan public preschools in the Barcelona metropolitan area, where the population is largely Catalan–Spanish bilingual. However, because the experimental materials were prepared in Catalan, it was felt important to ensure that all participating children were predominantly Catalan users and would therefore be fully comfortable. As a result, prior to the experiment, the parents of all those children recruited completed a questionnaire (based on Bosch & Sebastián-Gallés, Reference Bosch and Sebastián-Gallés2001) to determine the degree to which their child was exposed to Catalan on a daily basis. The 20 children whose parents reported a daily exposure to Catalan of less than 50% were excluded from the study, as were an additional eight whose parents failed to complete the questionnaire. This left a final participant population of 64, for whom the mean percentage of daily exposure to Catalan was 85% (SD = 0.158) This population was then divided into two groups by age, with the younger age group made up of 32 children (mean age 3;8, SD = 0.464) and the older age group also made up of 32 (mean age 5;1, SD = 0.495). Both groups were balanced for gender, with 16 girls and 16 boys in each. The children's parents were informed about the experiment's goal and signed a participation consent form prior to the commencement of the study. This study, including the consent procedure, was approved by the Ethics Board of the Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

Materials

In order to elicit request speech acts from the children which would be as close as possible to natural speech, a semi-spontaneous discourse elicitation task was designed which included four controlled and pre-planned situations (an adaptation of Uçar & Bal's, Reference Uçar and Bal2015, experimental design). Importantly, in contrast to the Discourse Completion Task (DCT) that is usually carried out with adults and often also with older children (see, e.g., Vanrell, Feldhausen, & Astruc, Reference Vanrell, Feldhausen, Astruc, Feldhausen, Reich and Vanrell2018), where subjects respond to hypothetical or fictional discourse contexts, the present data-collection method actually places children in real situations, thus removing the meta-cognitive layer of the DCT task which may cause participant to produce unnatural, prototypical responses. However, the virtue of both the DCT and the method employed here is that they allow the researcher to control for contextual variables and demographic information, facilitating the possibility of drawing legitimate cross-cultural comparisons. However, due to their controlled nature, these methods might elicit a more prototypical response as compared to natural spoken interaction due to the lack of a more interactional nature, something which should be borne in mind when analysing the data.

The pre-planned target situations in the experiment were designed to allow us to modulate two variables that affect in the expression of politeness, as follows:

a) Social distanceFootnote 2 between Hearer and Speaker. This factor had two levels: low and high.

b) Cost of the face-threatening act, meaning the degree of imposition by the Speaker on the Hearer that the request implied. This factor likewise had two levels: low and high.

For the present study we used a slightly adapted version of Uçar and Bal's (Reference Uçar and Bal2015) design. We constructed four different conditions, varying along two variables, social distance (low/high) and cost of the face-threatening act (low/high). In the first condition (low power, low cost), children worked in pairs to put together a jigsaw puzzle. Whenever a child discovered that one of his/her partners had a piece s/he needed, we explicitly told the child that s/he could ask for it from their partner. In the second condition (low power, high cost) children were grouped into pairs and then asked to guess the number the researcher was thinking of. The child who first guessed the right number received a small bubble blower, while the other one received plain white dough. The child who did not guess the number was told to ask the other child to share the small bubble blower with them. In the third condition (high power, low cost), the children were shown some stickers and were told that, if they wanted to have them, they could ask for them individually. Finally, in the fourth condition (high power, high cost), one of the experimenters was looking through a kaleidoscope. The children had to ask for permission to look through the kaleidoscope.

Procedure

The children were tested in pairs in a quiet room at their respective preschools. We ascertained beforehand that the children in each pair were compatible, that is, that they would feel comfortable interacting, both by consulting their teachers and by checking with the children themselves. The two children were seated close to each other, each along one side of a table (see Figure 2). Experimenter 1, a native speaker of Catalan, sat adjacent to the children and gave them instructions to guide them through the four situations. Experimenter 2 sat opposite the children and operated the two video cameras which recorded each session, with one camera centred on the child to the left and the other centred on the child to the right. Experimenter 2 also participated as an interlocutor during the high social distance situations.

Figure 1. Description of the four request situations and pictures of the objects to be requested.

Figure 2. Video stills showing the four request situations.

Experimenter 1 accompanied each pair of children from their classroom to the experimental setting and then chatted with them briefly to put them at their ease, asking them questions about what they had been doing in class. She also introduced them to Experimenter 2 by name but did not draw her further into the conversation. She then explained that they were going to play some games. Then the four experimental request-elicitation contexts were created, always starting with the two low social distance situations (i.e., interaction between the two children) and then moving on to the high social distance situations (i.e., interaction between the children and the experimenter), with the cost variable alternating with each pair of contexts. Descriptions of each of the four situations follow (instructions given in Catalan during the experiment are rendered here in English translation).

Situation 1: low social distance – low cost. This involved giving each child a simple line drawing and several coloured wooden pieces whose shapes exactly matched the shapes depicted in the drawing. The children received an equal number of pieces, but each received one piece that the other child lacked. Experimenter 1 then told them: “Here is a drawing and some wooden pieces. Put each wooden piece on top of the shape that looks the same in the drawing. You might not have all the pieces you need because the children who were here before you might have misplaced them, so you might have to ask each other for a piece.” If the experimenter saw that the children failed to follow this last instruction, it was reiterated.

Situation 2: low social distance – high cost. Children were each given a piece of modelling dough to play with. Experimenter 1 then said: “Now let's play a guessing game. Think of a number between 1 and 5. Whoever guesses the number I am thinking of wins and can play with bubbles.” When one of the children guessed correctly, they were told: “You win! Great! Now you can play with the bubble blower.” After a little while, Experimenter 1 told the child who had lost: “I think you can ask your classmate if you can take a turn blowing bubbles.” If necessary, the losing child was again urged to ask for a turn. The ‘winning’ number to be guessed was manipulated to ensure that both children had a turn being the winner and loser and thus both produced requests. Also, the prize for winning alternated between the bubble blower and a wind-up toy in order to keep the object of the request desirable.

Situation 3: high social distance – low cost. Experimenter 1 showed the children that Experimenter 2 had a set of smiley face stickers and then told them: “Look, the children who were here before you got to stick some of these stickers on paper. But to get a sticker then had to ask her [indicating Experimenter 2 by name].” This was followed by a 5-second pause to see if the children would ask Experimenter 2 for stickers. If they did not, they were told: ‘Wouldn't you like to stick a sticker? I asked her for one and she gave it to me. But you have to ask her because they're her stickers.” If this also failed to elicit requests from the children, after a second pause the instruction was repeated. If another 5 seconds elapsed without a request being produced, the experimenters moved on to the next situation.

Situation 4: high social distance – high cost. Experimenter 2 held up a kaleidoscope and started looking through it, meanwhile exclaiming happily about the colours and shapes that she was seeing. She then passed it to Experimenter 1, who looked through it and made similar comments. Then addressing the children, Experimenter 1 said: “Are you interested? This kaleidoscope is Iris's favourite object and it is very important to her since it was a gift from her brother. So, if you want to look through it you have to ask her.” If 5 seconds then elapsed without the children making a request, Experimenter 1 continued: “The colours and shapes that you can see are really cool! Come on! Go ahead and ask her.” If this too failed to elicit a request, after 5 seconds the children were again urged with: “Come on! Try and ask her! She's very nice!”

The full experimental session lasted about 10 minutes. After the experiment, the children were accompanied back to their classroom. Scrutiny of the video material collected in the total of the 32 sessions showed a total of 231 verbal requests being made by the participating children. This was somewhat short of the 256 requests that could potentially have been produced (64 children × 4 situations), but there were 25 instances in which a child failed to produce a request either because they were too shy or did not really want the object in question. In addition to these 231 verbalised requests, the video-recordings showed 11 occasions where a request was made by non-verbal means only.

Data coding

Both verbal and non-verbal content of all requests was coded. Coding of the lexical and morphosyntactic content of each request was assigned manually and recorded on an Excel spreadsheet. PRAAT (Boersma & Weenink, Reference Boersma and Weenink2017) was used for the prosodic coding, and ELAN (Lausberg & Sloetjes, Reference Lausberg and Sloetjes2009) for the gestural and non-verbal coding. The specific procedure used for the coding of the different levels was as follows:

Modality

First we coded whether a request was verbal (with or without accompanying non-verbal cues) or exclusively non-verbal. Although some of these latter strictly non-verbal requests were pointing/reaching gestures, it was decided not to include pointing/reaching gestures in the overall analysis of politeness-related cues because the specific set-up of the experimental situations did not allow for a strict comparison of the appearance of pointing gestures. For example, the situation requesting a puzzle piece out of several pieces triggered most of the pointing gestures, while the other situations with no object location ambiguity triggered almost no pointing behaviour.

Lexical and morphological coding

From the literature on the expression of politeness in Catalan (see Fivero, Reference Fivero1976; Hübscher et al., Reference Hübscher, Borràs-Comes and Prieto2017; Payrató & Cots, Reference Payrató and Cots2011), we know that there are a number of ways requests can be modified in order to make them less face-threatening and that adults do so depending on the degree of imposition implied by the request (i.e., its cost) and the social distance between speakers. One way a request can be modified is by adapting the request type. There is a key distinction made in the speech act literature between direct and indirect speech acts. Basically, when there is a canonical match between form (declarative, interrogative, imperative) and function (statement, question, order/request), then it is referred to as a direct request, as in the case of: Dona'm això ‘Give this to me’, Close the window vs. an indirect request as in Em dones això? ‘Can you give this to me?’ On the other hand, other modification strategies such as downgraders (e.g., diminishing the force of the request through the epistemic modal potser ‘maybe’), terms of address (informal tu vs. formal vostè ‘you’), change of mood in the verb forms (indicative pots ‘can you’ vs. conditional podries ‘could you’), and the use of lexical politeness cues such as si us plau ‘please’ have been attested in the literature. The combination of these cues heavily influences the degree to which a request is perceived as more or less polite. In our dataset only the following two types of lexical/morphological cues occurred:

a) direct vs. indirect requests

b) presence vs. absence of please

These were therefore the only two variables that were coded in this regard.

Prosodic coding

The prosodic coding was carried out based on Hübscher et al. (Reference Hübscher, Borràs-Comes and Prieto2017) study on prosodic correlates of mitigation in Catalan formal register speech. The phonological and phonetic cues listed below have been found relevant in distinguishing formal polite speech from informal speech in various languages (e.g., Catalan: Hübscher et al., Reference Hübscher, Borràs-Comes and Prieto2017; Korean: Winter & Grawunder, Reference Winter and Grawunder2012). Some items were coded manually within the Praat interface while Praat registered others automatically, as follows.

Tier 1, orthographic transcription of the target requests, separated by words.

Tier 2, syllables, manually segmented. They were marked as (s) and were used to analyse duration patterns.

Tier 3, final intonation, roughly classified into falling and rising pitch contours.

Tier 4, intonation patterns, labelled in accordance with the Cat_ToBI framework (Prieto, Reference Prieto and Jun2014). The two graphs in Figure 3 illustrate the two most frequent intonation patterns found in the data, as well as the labelling procedure used.

Tier 5, F0 marks, with the following measures indicated manually for each Intonational Phrase: reference line (R, start of the pitch contour of each IP), the baseline (L, lowest F0 point in the nuclear pitch contour), and the top line (H, highest F0 point within the nuclear contour).

Figure 3. Waveforms, spectrograms, and F0 contours of the requests Jo vull ‘I want’ (falling pitch contour, left panel) vs. Me’l deixes? ‘Can you give it to me?’ (rising pitch contour, right panel). The orthographic and prosodic annotation tiers (tiers 1–5) are explained in this section.

The two graphs in Figure 3 show the annotated Praat output for the two requests Vull això ‘I want this’ (left graph) and Me'l deixes? ‘Can you give it to me?’ taken from our dataset. The five tiers described above can be seen below the waveform, spectrogram, and F0 contour in each graph.

Finally, a series of phonetic measures were automatically extracted within each annotated syllable, namely pitch (mean F0), duration, voice quality (mean jitter, shimmer, H1–H2 (the amplitude difference between the first and second harmonics) as a correlate of breathiness), and intensity.

Body and facial coding

As mentioned above, our non-verbal coding was carried out in ELAN (see Figure 5 for an example). Our coding system is primarily based on the MUMIN multimodal scheme developed by Allwood, Cerrato, Jokinen, Navarretta, and Paggio (Reference Allwood, Cerrato, Jokinen, Navarretta and Paggio2007). For those facial gestural cues that are not included in the MUMIN, we used elements from the FACS coding system by Ekman, Friesen, and Hager (Reference Ekman, Friesen and Hager2002).

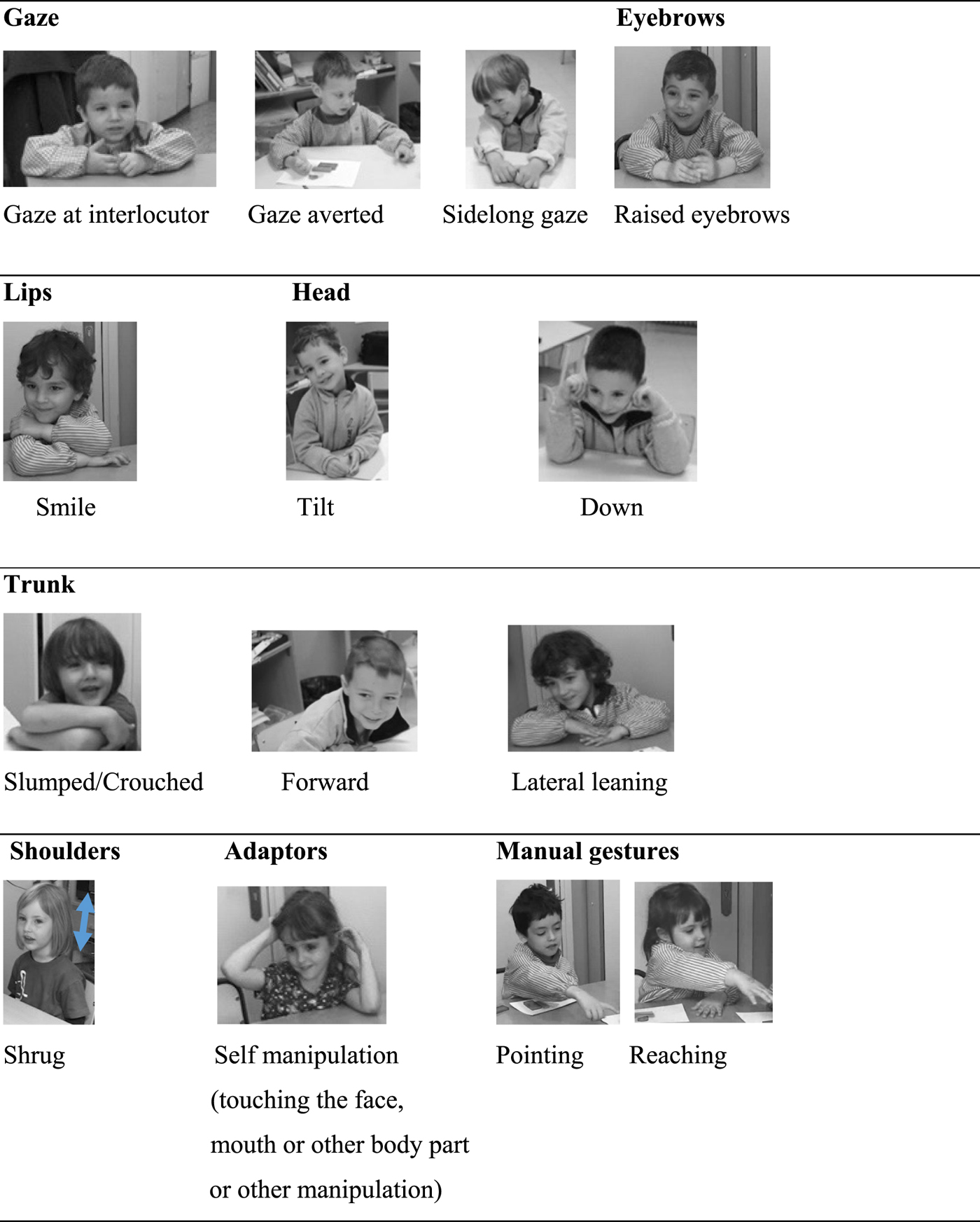

In order to create a comprehensive profile of politeness-related behaviours, we assessed an extensive range of facial and body cues all identified in previous studies as interacting with negative politeness (strategy used by the speaker to show that he cares and respects the hearers’ negative face), namely mitigation, power, and submission (see ‘Introduction’ for literature review). We then coded these cues primarily and importantly by adapting the coding system proposed in Brown and Winter (Reference Brown and Winter2018). Furthermore, similar to Brown and Winter, we took into consideration all body and face signals accompanying the verbal request. We refer especially to body postures which have been documented to arise in states of uncertainty or submission, and to adaptors, i.e., hand movements which denote psychological discomfort and anxiety. As far as the former type of signals are concerned – signals arising in states of uncertainty or submission – it is well known that uncertainty lexical markers are used as hedges in order to lessen the face-threat (see, e.g., Caffi, Reference Caffi1999). Hence it seemed relevant in this context to consider the non-verbal correlates of uncertainty markers. A detailed description of body and facial cues associated with uncertainty/doubt has been given by Givens (Reference Givens2001) and Krahmer and Swerts (Reference Krahmer and Swerts2005). Their reports include facial expressions (eyebrow frowns, eye-movements, lip-pouting, lip-pursing), head movements (headshakes, head tilts), and cues like palm-up open hand gestures and shoulder shrugs. As far as the latter signals are concerned – adaptors – although they do not communicate negative politeness in a narrow/strict sense, but rather speaker's discomfort, we decided to include them in the analysis as they signal the speaker's hard time in making a request that does not sound as an imposition on the hearer. However, they determine that the hearer acts conformingly and grants the speaker's request. This is especially complicated in asymmetrical contexts, where the speaker has a lower status than the hearer. Although adaptors are performed with little awareness and no intention to communicate, we decided to take them into account as they nonetheless allow the conveying of information and they allow observers to make inferences on the speaker's emotional state (Morris, Reference Morris2002). The resulting set of body and facial cues are illustrated in Figure 4, labelled with the terms we used for coding purposes.

In order to illustrate children's multimodal signalling of politeness-related and non-politeness-related meanings, we will describe one example in more detail. In Figure 5, the boy on the left is requesting a sticker from the experimenter. About a second before the child starts to voice the request he produces several non-verbal cues, namely a lowered head, slumped shoulders, and an averted gaze. Then while he produces the request Em deixes enganxar un gomet? ‘Can I stick a sticker (on a piece of paper)?’, marked with a rising intonation, the boy tilts his head and adopts a sidelong gaze towards the experimenter. Towards the end of the verbal request he produces a smile, and lightly shrugs his shoulders before reverting to his initial slumped posture. He also bites his lower lip, a typical adaptor.

Figure 4. Annotated gestural and non-verbal categories.

Figure 5. Example of labelling with the request Em deixes enganxar un gomet? ‘Can I stick a sticker (on a piece of paper)?’

Reliability of the coding

An inter-rater reliability test (blind-coding) was carried out to check the consistency of the prosodic and gestural coding of politeness-related cues. Twenty percent of the database (i.e., 44 requests, were randomly selected, with care taken to ensure that the four conditions were uniformly represented across speakers). Two external raters were asked to independently annotate this subset of the audiovisual recordings. The FLEISS Kappa statistic for rater annotations was obtained. Since three raters in total were involved, the Fleiss fixed marginal statistical measure was used. Fleiss guidelines characterise kappas over 0.75 as excellent, 0.40–0.75 as fair to good, and below 0.40 as poor. The fixed marginal kappa statistic obtained for the classification of all the intonational and gestural codings are as follows: intonational contours classified into rising and falling nuclear pitch contours (0.76); in relation to gesture, the marginal kappa statistic was obtained on the one hand for the presence or absence of gestural cues (first number) and on the other hand also for the number of occurrence of each gestural cues per request (second number), as follows: eye-gaze at interlocutor (0.88/0.48), eye-gaze averted (0.76/0.47), sidelong eye-gaze (0.73/0.77), raised eyebrows (0.88/0.88), smile (0.52/0.44), head tilt (0.48/0.44), head down (0.48/0.48), shoulder shrug (0.52/0.53), slumped shoulders (0.52/0.59), trunk forward (0.42/0.47), trunk later leaning (0.52/0.51), adaptors (0.67/0.54), pointing gesture (0.82/0.83), reaching gesture (0.79/0.79). The fact that the Fleiss kappa statistical measure was a bit lower for certain gestural movements (for example, head down, head tilt, and trunk forward) than for the rest of the annotations might be due to the fact that some movements were only slight and thus might have been detected by one rater but not by the other. However, none of the results could be considered as poor and overall the scores reveal a considerable agreement among raters and thus validate the annotations made in the corpus.

Data extraction and statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics v24 software. More specifically, a series of Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs) were undertaken to compare the values found for the two levels of each of our three fixed factors SOCIAL DISTANCE (two levels: low vs. high), COST (two levels: low vs. high), and AGE (two levels: younger vs. older). Random intercept was specified for Subject.

The dependent variables were (1) the modality of the request (verbal vs. non-verbal); (2) the presence of morphosyntactic or syntactic cues (indirect request or please); (3) prosodic features (rising intonation, mean speech duration, pitch, jitter, shimmer, H1–H2, and intensity); and (4) the presence of gestures and other body signals, broken down into three broad categories: gaze, facial cues, and body cues. The lexical and morphological cues as well as some of the prosodic, gestural, and body cues were count in nature (i.e., they might occur zero, one, or several times during a single request unit). On the other hand, the phonetic correlates of prosody such as duration, pitch, intensity, and voice quality were all gradient in nature and measured in their respective units.

Results

In this section, we first analyse the data in relation to the ‘Modality of requests’. We then analyse the data related to ‘Morphosyntactic and lexical strategic cues’. After that, we report on the ‘Prosodic features’ of the children's requests. Finally, we provide an analysis of the ‘Gestural and other body signals’.

Modality of requests

The vast majority of the requests made by children in our dataset were executed verbally (with or without accompanying non-verbal cues). This is not very surprising since children in the instructions were told that they could ask for the objects in the various conditions. However, participants occasionally simply pointed at or reached for an object in order to express their desire that it should be given to them, and these communicative acts were thus coded as non-verbal requests. Results of the GLMM showed a significant main effect of SOCIAL DISTANCE (F(1,220) = 10,804, p = .001) and COST (F(1,220) = 8,300, p = .004) on the modality of requests, such that there were more verbal than non-verbal requests in high social distance and high cost situations (p = .023), compared to low social distance and low cost situations (See Table A in the ‘Appendix’ for a table of mean occurrences of verbal requests per situation, broken down by age group and experimental parameter). Overall, however, the prosodic and gestural cues are thus mostly co-verbal and this might be a reason for why there are only few requests that are solely gestural even when children are addressing their peers.

Morphosyntactic and lexical strategies cues

In the total of 220 verbal requests in our dataset, the only morphosyntactic cue to politeness observable was the use of indirect question structures, and the only lexical cue sometimes deployed by the children was the mitigator si us plau ‘please’. The mean occurrence of indirect requests and si us plau is shown respectively in the two graphs in Figure 6, broken down by age group and social distance and cost parameters. Statistical analysis of the data showed a main effect of COST on children's production of indirect requests (F(1,220) = 13,260, p < .001), with significantly more indirect requests in high cost requests (see Figure 6). Furthermore, there was a statistically significant interaction between the effects of SOCIAL DISTANCE and AGE on the production of indirect requests (F(1,220) = 12,434, p = .001). While in the younger age group there were significantly more indirect requests in low social situations (p = .007), in the older age group there were significantly more indirect requests in high social distance situations (p = .035). This suggests that while the children in the younger age group had not yet assimilated the relationship between indirectness and politeness in Catalan, the older group had. Furthermore, there was a main effect of both SOCIAL DISTANCE (F(1,220) = 12,875, p = .001) and COST (F(1,220) = 6,331, p = .013) on the presence of si us plau. In other words, the children tended to produce more si us plaus in situations involving higher social distance or higher cost (see Table B in the ‘Appendix’ for full results).

Figure 6. Mean occurrence of indirect requests (left panel) and si us plau ‘please’ (right panel), broken down by social distance, cost, and age group. Error bars indicate standard error.

Prosodic features

Intonation contour

As noted, because rising intonation has been identified as a marker of politeness, all instances of rising intonation in the dataset were noted. A GLMM analysis showed a significant effect of COST on the production of rising intonation contours (F(1,201) = 8,906, p = .003), with rising tunes being used more often in high cost requests than in low cost requests, as can be seen in Figure 7 (see Table C in the ‘Appendix’ for full results).

Figure 7. Mean occurrence of rising intonation across the three conditions, namely social distance, cost, and age. Error bars indicate standard errors.

Mean syllable duration

Mean syllable duration was extracted automatically from all regular syllables produced in the requests (results for this and all other phonetic parameters are given in Table 1). Statistical analysis showed a main effect of SOCIAL DISTANCE (F(1,1245) = 22,660, p < .001) and a main effect of COST (F(1,1243) = 5,691, p = .017) on the mean duration of syllables. In other words, the duration of syllables tended to be significantly higher in high social distance situations and also in high cost situations. This suggests that, independently of their age, the children produced significantly longer requests when they had to request something from someone with higher social distance or when their request implied a higher degree of imposition.

Table 1. Mean (and standard deviation) phonetic values for all the syllables in the dataset of verbal requests uttered by children broken down by age group and social distance and cost parameters. Units of each values are given in parentheses in the left-hand column.

Average pitch

Average pitch was extracted automatically from all syllables produced in the requests. Moreover, three other pitch measures were extracted by using manually placed specific points in each intonational phrase, namely the reference line, the top line, and the baseline. Table 1 shows the results of the various GLMMs applied plus the means estimated by the models. There was a significant interaction between AGE and COST in pitch height (calculated from the mean of all syllables) (F(1,1218) = 10, 951, p < .001). In the younger age group, average pitch height was significantly higher in high cost requests (p = .006). By contrast, the effect of COST on pitch was slightly under significance (p = .58) for the older age group, with higher pitch more frequent in low cost requests.

Voice quality and intensity

The following measures of voice quality were automatically extracted for each syllable in our recordings: intensity (in dBs), perturbation by amplitude (shimmer), perturbation by F0 period (jitter), and the harmonic differential (the difference in amplitude between the first and second harmonics, H1–H2, in Hz) (see Table 1).

Statistical analysis showed a main effect of COST on jitter (F(1,1211) = 10,117, p = .002), with significantly less jitter in high cost requests (p = .002) compared to low cost requests.

There was a main effect of AGE on shimmer (F(1,1207) = 8,244, p = .004), with more shimmer in the older group, and a main effect of COST (F(1,1207) = 7,390, p = .007), with more shimmer in high cost requests. However, there was a significant interaction between AGE and COST (F(1,1207) = 11,977, p < .001). In the older group, cost had a significant effect on the production of shimmer (p < .001), with more shimmer in high cost situations compared to low cost situations, but this difference was not seen in the younger group (p = .600).

There was a significant interaction between AGE and COST in relation to the production of H1–H2, which can be taken as an index of breathiness (F(1,1218) = 8,743, p = .003). In the older age group, cost had a significant effect on the production of H1–H2 (p < .001), with more breathiness in high cost requests, there was no effect in the younger group (p = .368).

Finally, regarding syllable dB (intensity), there was a significant interaction between AGE and COST (F(1,1243) = 8,701, p = .003). In the older group, COST had a significant effect on the intensity rate, with higher intensity in low cost requests (p = .003). There was no effect of COST in the younger group (p = .224).

Gestures and other body signals

As noted above, the set of 11 gestural or body signals was divided into three categories, gaze, facial cues, and body signals, with this last further separated by part of the body into head, shoulders, and trunk (see Table D in the ‘Appendix’ for full results.)

Gaze

With regard to the direction of the speaker's gaze while making a request, the children in our study displayed three different behaviours, with gaze either directed at one of the experimenters, averted, or directed to the side. The distribution of these three behaviours varied according to whether the child was interacting with an adult or with a peer, and also according to the social distance and cost dimensions of the situation, as can be seen in Figure 8. GLMM analysis revealed a main effect of SOCIAL DISTANCE (F(1,220) = 46,492, p < .001), with significantly more gazes directed at the interlocutor in high social distance contexts. Complementarily, there was a main effect of COST (F(1,220) = 6,996, p = .009), with children averting their eyes significantly more when making low cost requests. A near significant effect of social distance was also revealed (F(1,220) = 3,842, p = .051), with a non-significant tendency for the child's gaze to be averted in low social distance situations. Furthermore, there was a main effect of SOCIAL DISTANCE on the occurrence of sidelong gazes (F(1,220) = 8,537, p = .004), with significantly more sidelong gazes in situations of high social distance.

Figure 8. Mean occurrences of ‘gaze at experimenter’ (top-left panel), ‘averted gaze’ (top-right panel), and ‘sidelong gaze’ (bottom panel) in each request across the three conditions, namely social distance, cost, and age. Error bars indicate standard error.

Facial cues

The two facial cues to politeness that appeared in our dataset were raised eyebrows and smiling. As can be seen in Figure 9, both raised eyebrows and smiling occurred more frequently in high social distance contexts. This difference was confirmed to be significant by GLMM analysis, which showed a main effect of SOCIAL DISTANCE on eyebrow raising (F(1,220) = 15,134, p < .001) and smiles (F(1,220) = 11,353, p < .001), with significantly more raised eyebrows and smiles in the high social distance situations.

Figure 9. Mean occurrence of ‘raised eyebrows’ (left panel) and ‘smile’ (right panel) during requests across the three conditions, namely social distance, cost, and age. Error bars indicate standard error.

Body cues

As noted above, body cues were broken down by body part. During requests, the children sometimes tilted their head to the side and inclined it forwards so that they faced down (see Figure 10). Analysis of our results detected a main effect of SOCIAL DISTANCE on both ‘head tilt’ (F(1,220) = 7,122, p = .008) and ‘head down’ (F(1,220) = 5,032, p = .026).

Figure 10. Mean occurrence of ‘head tilt’ (left panel) and ‘head down’ (right panel) during requests across the three conditions, namely social distance, cost, and age. Error bars indicate standard error.

The distribution of shoulder movements made during requests, which were categorised as either shrugs or slouches, were analysed. No significant effects were found for slouched shoulders. The results for shrugs can be seen in Figure 11. Analysis of this data revealed a main effect of SOCIAL DISTANCE (F(1,220) = 13,537, p < .001) on shoulder shrugs, with more shrugs in high social difference situations, and a main effect of AGE (F(1,220) = 7,657, p = .006), with the younger age group producing more shoulder shrugs. However, there was a significant interaction between AGE and SOCIAL DISTANCE (F(1,220) = 9,173, p = .003). Only in the older age group were there significantly more shrugs in high social difference situations (p = .001), this effect being completely absent in the younger group (p = .500).

Figure 11. Mean occurrence of ‘shoulder shrug’ made by children while making requests across the three conditions. Error bars indicate standard errors.

The children were seen to hold their bodies in one of two ways while making requests, either forward or to the side. The results for these two trunk movements are shown in Figure 12. GLMM analysis showed a main effect of SOCIAL DISTANCE on both ‘forward leaning’ (F(1,220) = 6,710, p = .010) and lateral leaning (F(1,220) = 5,160, p = .024), with more occurrences in high social distance situations, and a main effect of age (F(1,220) = 6,298, p = .013), with more lateral leanings produced by younger children (p < .008). There was, however, an interaction between the effects of SOCIAL DISTANCE and AGE (F(1,220) = 6,810, p = .010). In the older group, high social distance caused more occurrences of laterally leaned trunks (p < .003), while there was no significant effect of SOCIAL DISTANCE in the younger group (p = .779).

Figure 12. Mean occurrence of body postures ‘forward leaning’ (left panel) and ‘lateral leaning’ (right panel) adopted by children while making requests across the three conditions. Error bars indicate standard errors.

Finally, regarding the children's use of ‘adaptors’ like touching their face or mouth, GLMM analysis showed a main effect of SOCIAL DISTANCE (F(1,220) = 20,472, p < .001). As can be seen in Figure 13, significantly more adaptors were produced in the high social distance condition, meaning that in both groups the children touched themselves or other objects significantly more when talking to a person of greater social distance (i.e., an adult).

Figure 13. Mean occurrence of ‘adaptors’ made by children while making requests across the three conditions. Error bars indicate standard errors.

Discussion and conclusions

The cross-sectional research presented here constitutes the first study to systematically document the multiple cues, both verbal and non-verbal, that three- to five-year-old children use to make a request more polite. We have also analysed the interaction between those cues and two parameters, social distance and the cost to face, as well as age. We hypothesised that: (1) preschool children – like adults – would mitigate their requests in different ways depending on the degree of social distance between interlocutors and degrees of cost; (2) they would be more likely to show politeness by means of prosodic, gestural, and other body signals than by the use lexical or morphosyntactic markers; and (3) their repertoire of mitigation strategies to signal politeness would increase as they got older. Overall, our three hypotheses have been confirmed by our results, with several of our findings being of particular interest.

With regard to our first hypothesis, our findings confirm that preschool children use a wide set of prosodic mitigation strategies, including rising intonation, slower speech rates, less jitter, and more breathiness, to render requests appropriately more polite in contexts where either their interlocutor is socially distant from them, or their request implies a high cost in face to their interlocutor. Interestingly, in contexts involving a high power distance between the child and their interlocutor (an adult researcher, for example) the favoured strategy observed in our sample was a reduced speech rate, whereas rising intonation tended to be deployed more often in high cost contexts. Comparing these prosodic findings to results found for Catalan-speaking adults by Hübscher et al. (Reference Hübscher, Borràs-Comes and Prieto2017), it would seem that five-year-old children can make use of much the same prosodic cues as adults. Nonetheless, because Hübscher et al. analysed adult politeness in interaction with only one social parameter, power distance, the results of the two studies are not strictly comparable. The present findings regarding intonation are more readily comparable to those made by Astruc et al. (Reference Astruc, Vanrell, Prieto, Armstrong, Henriksen and Vanrell2016); these authors showed that, for adult Catalan speakers, high cost situations triggered more rising pitch patterns than low cost situations, but social distance did not have a significant effect on the choice of intonation contour. This means that, with regard to intonation and syllable duration, by the age of three children already use a phonological mitigation strategy similar to that seen in adults, and by age five they can deploy most of the other phonetic cues to politeness in an adult-like way.

With respect to non-verbal signals, our study has shown that preschool children use a wide array of gestural and body signals to mark their polite stance towards an adult with higher social distance and/or to request an object with more cost to the interlocutor's face. Children produce significantly more eyebrow raises, smiles, adaptors, head tilts and head downs, raised shoulders, and trunk lateral leanings in high social distance conditions than in low social distance conditions. Most of these cues have been found to be submission cues displayed towards a person with more power (Ellyson & Dovidio, Reference Ellyson, Dovidio, Ellyson and Dovidio1985; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Coats and LeBeau2005; Tree & Manusov, Reference Tree and Manusov1998). Two of the body postures or movements that we analysed in this study – the head tilted to one side or facing down and shrugging shoulders – have been found elsewhere to be important cues in the expression of uncertainty (Roseano, González, Borràs-Comes, & Prieto, Reference Roseano, González, Borràs-Comes and Prieto2016), and it is therefore reasonable to suppose that they could serve a mitigation function in requests. And indeed our results show that preschool children display significantly more tilted or lowered heads and raised shoulders (among other cues) when making a request in high social distance contexts.

In this context it is interesting to note that while prosody was mainly adapted in regard to increased cost, mitigating gestural and body cues were used predominantly in requests with high social distance. Clearly there was a strong social distance between the child participants and the adult experimenter. This possibly intimidating situation, next to being face-threatening, might have elicited such a high number of gestural and body cues on the part of the children when requesting something from an unknown adult. In the same way, perception experiments would be necessary to delve into the question of the individual weight of each of these cues in the production of politeness cues.

Our second main finding relates to the use of lexical and morphosyntactic strategies used by preschool children to convey politeness relative to prosodic and gestural ones. While both age groups used si us plau ‘please’ significantly more in high social distance contexts, only the older children were able to vary their requests morphosyntactically by using indirect constructions. These results are comparable to previous studies that have found that children up to the age of five mainly use direct request strategies (see, e.g., Aronsson & Thorell, Reference Aronsson and Thorell1999; Axia & Baroni, Reference Axia and Baroni1985; Bates, Reference Bates1976; Bernicot & Legros, Reference Bernicot and Legros1987; Ervin-Tripp & Gordon, Reference Ervin-Tripp, Gordon and Schiefelbusch1986; Georgalidou, Reference Georgalidou2008; Hollos & Beeman, Reference Hollos and Beeman1978; James, Reference James1978; Nakamura, Reference Nakamura1999; Nippold et al., Reference Nippold, Leonard and Anastopoulos1982; Read & Cherry, Reference Read and Cherry1978; Ryckebusch & Marcos, Reference Ryckebusch and Marcos2004). Furthermore, please appears relatively early in childhood, which could be explained through the heavy emphasis that parents and caregivers place on this lexical item (Gleason & Weintraub, Reference Gleason and Weintraub1976; Greif & Gleason, Reference Greif and Gleason1980; Nakamura, Reference Nakamura, Nakayama, Mazuka and Shirai2006). Yet other request internal strategies which can be found in adult Catalan speech, such as the formal form of address vostè vs. the more informal tu, the choice of verbal forms (conditional vs. indicative) and other lexical hedges (see Fivero, Reference Fivero1976; Hübscher et al., Reference Hübscher, Borràs-Comes and Prieto2017; Payrató & Cots, Reference Payrató and Cots2011), are clearly lacking in preschool children's requests. Taken as a whole, our results thus provide tentative confirmation that the number of prosodic and non-verbal politeness markers available to young children greatly outweighs their lexical and morphosyntactic repertoire.

This ties in with our final hypothesis regarding the expansion of this repertoire of politeness markers over time. Our findings are consistent with previous studies showing that children's ability to deploy lexical and morphosyntactic politeness markers takes place slowly in and also after the preschool years (Baroni & Axia, Reference Baroni and Axia1989; Nippold et al., Reference Nippold, Leonard and Anastopoulos1982; Pedlow et al., Reference Pedlow, Sanson and Wales2004). Comparing these results to adults’ systems of politeness, children at age five clearly still have a long way to go. Most notably, mitigation strategies such as the use of conditionals or the use of vostè are completely absent from our dataset. Furthermore, the younger children in our study produced more indirect requests in low social distance situations, contrary to what one would expect, suggesting that they had not fully grasped the mitigating value of this structure. By contrast, the children in the older age group produced more indirect requests in social distance situations, as one would see in adult discourse.

In fact, the present data show that at age three children actually already exploit a wide range of gestural, body, and prosodic cues to express politeness. Indeed, when looking at the development of those strategies, there is very little variation in children's use of gestural and other body markers of politeness related meanings over the preschool years. Only lateral leaning and shoulder shrugs are used more by the older age group in high social distance situations. Regarding prosodic cues, although the younger children already use intonation and duration as mitigation cues in an adult-like way, the older children can manipulate a much broader and adult-like arsenal of phonetic features such as intensity, jitter, and breathiness to convey politeness. Thus, our results as a whole make it obvious that preschool-aged children are adjusting their requests depending on who they are talking to and the degree of imposition that the request implies by employing a rich system of non-propositional markers before they are able to express similar meanings through lexical/morphosyntactic cues.