In a review of recent contributions to long-running debates over the meaning of ‘dependence, unfreedom and slavery’ in Africa, Benedetta Rossi critiques Africanist scholars’ use of the term ‘belonging’ to denote a fact about a person's social standing that determines her fate. As Kopytoff and Miers famously wrote forty years ago, the antithesis of ‘slavery’ is not ‘freedom’ qua autonomy, but rather ‘belonging’.Footnote 1 Rossi disagrees: people's lives, she argues, are not uniquely determined by their social position. Even slaves face different circumstances at different times and places, and do not all make the same choices among available possibilities, however limited these may be. ‘Belonging per se does not do anything’, Rossi writes. ‘Belonging is as belonging does.’Footnote 2

Read as a social fact or indicator of social status, ‘belonging’ does not do anything — but people do, and their actions and interactions bear on their relations to one another (‘she belongs to our family‘) and to things (‘he carried his belongings in an old suitcase’). Building on Rossi's analysis, I suggest that belonging may be understood as a process — a moving dynamic of social actions and interactions that alter or reinforce individuals’ life chances and their relations to one another. Material possessions are just one of the moving parts in this process. How people access, use, and control things may influence or result from their interactions with and social standing in the eyes of others. As more or less enforceable claims on other people, financial possessions are also emblematic of the interactive, social character of belonging — perhaps even more so.

To illustrate the processes at work in various forms of belonging, I present the case of an inheritance dispute in Asante that raises several questions about the sources and implications of belonging to a family.Footnote 3 The case was adjudicated in 1951, in one of the customary courts established under the British system of colonial governance known as indirect rule. Having dismantled the Asante monarchy when they took control of the central region of Ghana in the late nineteenth century, British authorities gradually rebuilt it in the 1920s and 1930s, hoping, inter alia, that their colonial subjects would be happier to pay taxes to their accustomed rulers than to alien British officials.Footnote 4 In 1936, the colonial administration ‘restored’ the Asante monarchy with much fanfare. As part of the ‘restoration’, officials established a hierarchy of courts under the authority of the reinstated asantehene, in which Asante chiefs adjudicated cases deemed subject to customary law.Footnote 5 Inheritance disputes among Africans were included in the chiefs’ courts’ jurisdiction.Footnote 6

The case discussed below was heard in April 1951. At the time, institutions established by the colonial administration remained in place, but officials were beginning to prepare for an eventual transition to independence. The prospect of an end to colonial rule was, in turn, animating debates about who could claim to be a citizen of Ghana and what citizenship would mean for those who held it. Two months earlier, Nkrumah had been named leader of government business after winning an election that he contested while still in prison for leading protests against colonial rule. Released from jail, Nkrumah lost no time in laying the groundwork for his Convention People's Party to gain control of the independent state. While battles over control of the incipient nation were foremost in the years leading up to independence, questions of authority, obligation, and belonging reverberated at all levels of social interaction, from the national to the domestic.

Family property

The case in question was heard over the course of three days by a panel of three senior Asante chiefs. The litigants — a woman named Abena Bimpeh and a man, Akwasi Kumah, who contested Abena Bimpeh's claim on behalf of himself and his brothers — both belonged to the family of Kofi Wuo, a ‘subject’ of the stool of Amoaful who died in the late 1940s.Footnote 7 At no point during the trial did anyone question the fact that the litigants were all ‘of Kofi Wuo's family’. The points at issue were how they belonged to the family and how the manner of their belonging bore on their claims to Kofi Wuo's estate.Footnote 8 Both turned on issues covered by customary rather than statutory law.

Since the court transcript makes no mention of a will, it appears that Kofi Wuo died intestate. Under the Akan system of inheritance, when a man dies without leaving a written will, his property becomes the property of his family. (When a woman dies, her property goes to her uterine sister(s) and other female relatives. A woman may, however, share in the benefits of property held collectively by her matrilineal family).Footnote 9 Following the death of a family member, the family meets to appoint a ‘successor’ — a position more like that of an administrator or trustee than an heir. Detailed in numerous court cases and books by legal experts, the duties of a successor include taking charge of the deceased's estate, settling his/her outstanding debts, and seeing to it that whatever property remains in the estate after the debts are settled is distributed according to the will, if there is one, or managed on behalf of the family if there is not. The successor takes charge of the properties in the deceased's estate but does not own them: his duty is to see that they are used for the benefit of the family. He (or occasionally she) was also expected to mediate disputes among the survivors, including arguments over which of any aspiring heirs were entitled to share in the estate. Unsurprisingly, this arrangement gave rise to frequent, sometimes heated, discussions over who belonged to the family and who was entitled to benefit from the deceased's estate.Footnote 10

The ‘family’ who inherited a dead person's property consisted of the kin, not the conjugal family, of the deceased. In Asante, descent was reckoned matrilineally: neither the wives nor the children of a deceased man had any claim on his estate and were liable to be turned out of the conjugal home by the dead man's relatives. A woman who had helped develop her husband's tree farm(s) or other properties could also lose any claim to the fruits of her labor, unless the husband's kin chose to give her something in recognition of her services. In principle, a widow would be cared for by her natal family but, if her family did not provide for her, she could end up destitute or dependent on her children.

Children inherited from their mother's brothers, rather than their biological fathers. A man could, of course, gift property to his wives and children while he was still alive — a practice that became increasingly common in the twentieth century — but the family might decide to challenge the validity of such a gift, forcing the widow and children to go to court to try to prove their case. In response to growing public complaints about the injustice of this system, in 1985 the then-military regime headed by Jerry Rawlings promulgated a new Law on Intestate Succession (PNDC Law 111), which mandated that when a person died intestate, the conjugal house, chattels, and the majority of the estate would pass to the surviving spouse and children of the deceased.Footnote 11

While most analysts agree that PNDC Law 111 has mitigated the problem of spousal dispossession, it applies only to property that the deceased acquired through his/her own effort — not to property held collectively by his or her family. To increase their share of the estate, the surviving kin could (and often did) claim that assets held by the deceased were family (not self-acquired) property and were therefore exempt from PNDC Law 111. To protect their wives and children from lengthy disputes, a number of men wrote wills or made gifts inter vivos, assigning most of their property to their surviving spouse and children, but taking care to set aside a portion ‘for the family’.Footnote 12

Disputes over inheritance provide a window into family politics, revealing the strategies that people used to protect or advance their interests vis-à-vis those of their relatives and giving glimpses into the legal, economic, and social conditions that drove and limited their efforts. As a number of historians and other scholars have shown, the British officials who took power in Asante at the turn of the twentieth century passed laws abolishing slavery and human pawning in 1908, but held off moving vigorously to enforce them for fear of disrupting economic activity, especially export crop production, or provoking unrest.Footnote 13 Though legally free, many slaves remained with their masters’ families for both practical and emotional reasons. Ostensibly absorbed into their parents’ former owners’ families — a process reinforced by the widely accepted convention that one did not speak of another's origins — the subordinate status of slaves’ descendants lingered in memory and, in some cases, practice. People's claims on family resources were complicated by histories of slave descent. Scholarly generalizations to the effect that, under customary law, slaves’ descendants could inherit property from members of their adoptive families gloss over the messy process of case-by-case debate through which customary law governed social practice.Footnote 14

The trial

At the time of his death, Kofi Wuo occupied the stool (i.e., held the office) of ⊃kyeame (‘linguist’) to the chief of Amoaful, and the first order of business after he died was to appoint a new ⊃kyeame.Footnote 15 A man called Kojo Tano was named to succeed him. After some procedural delays, Kojo Tano was summoned to Amoaful to be installed as ⊃kyeame. The ceremonies proceeded, apparently without incident, until Kojo Tano asked for the late Kofi Wuo's cocoa farms in addition to the insignia of his office. Led by two brothers — Kwaku Kumah and Akwasi Kumah — the men from Kofi Wuo's household refused to turn over the farms, explaining that since Kofi Wuo had developed the farms by his own effort rather than receiving them from the stool, they were his personal property, not the property of the stool.Footnote 16 Frustrated, Kojo Tano left Amoaful in a huff, surrendering the ⊃kyeame stool as well as his claim to the farms, and returned to his home village.

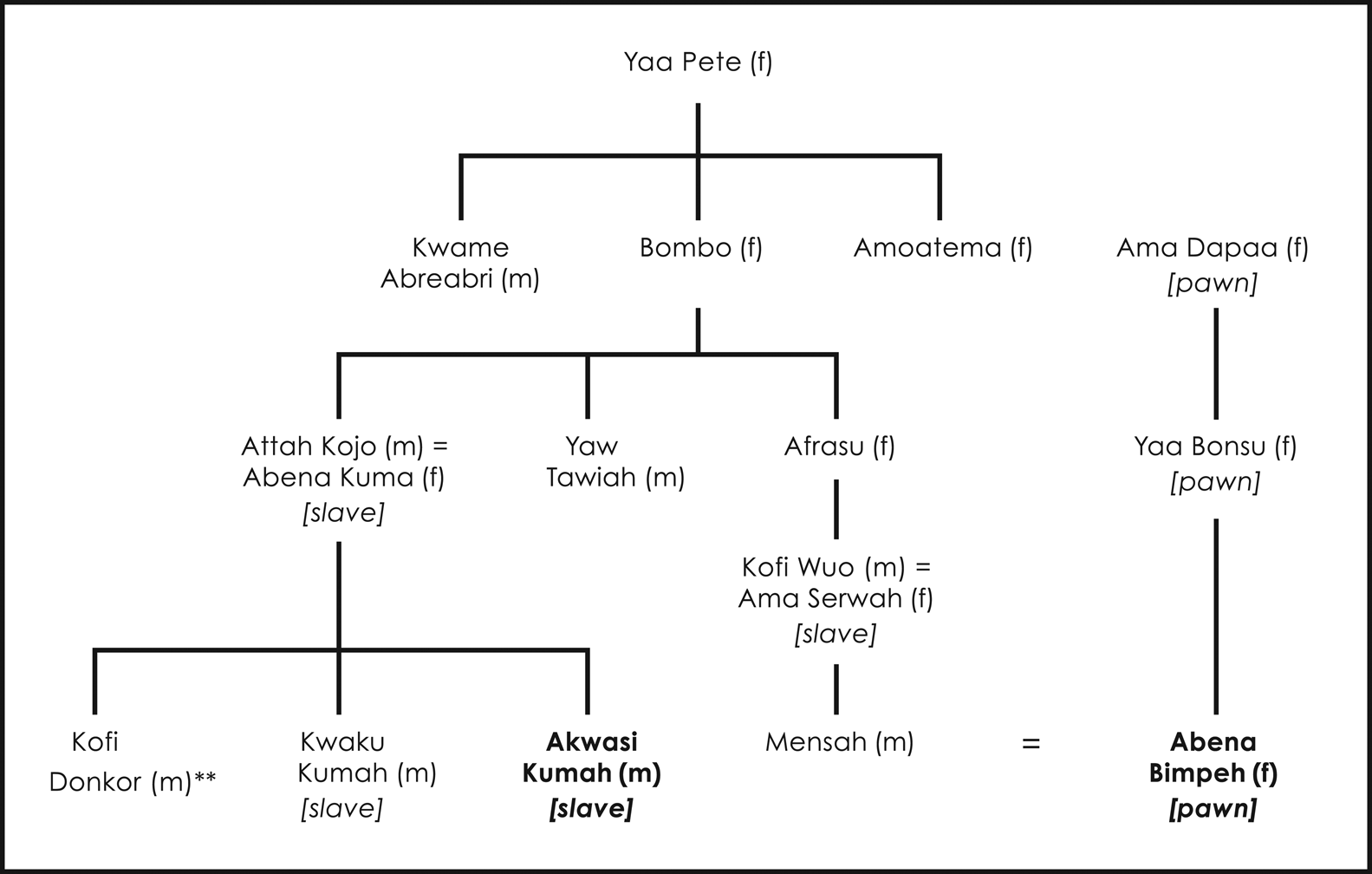

Not long after these events, a woman named Abena Bimpeh applied for letters of administration to Kofi Wuo's estate. The date of her application is not recorded, but she had supported Kojo Tano in his bid for Kofi Wuo's cocoa farms, and it seems likely that she sought the letters of administration after Kojo Tano had abandoned his claim. Charging that Abena Bimpeh was not entitled to share in — let alone administer — Kofi Wuo's estate, Akwasi Kumah countersued on behalf of himself and his brothers (see Fig. 1). In April 1951, the case was heard in the asantehene's B1 Court by a panel of three senior Asante chiefs, led by Kenyasehene Barima Owusu Agyeman III.Footnote 17 For three days, the court heard testimony from the plaintiff, the defendant, and eight witnesses concerning the litigants’ ties to Kofi Wuo's family, the history of their interactions with the deceased, and the legitimacy of their respective claims to his property.

Figure 1. Kofi Wuo's family.*

* Persons named in the court transcript. At no point in the trial did anyone ask for or provide a complete list of family members, living or dead.

** Child of Attah Kojo, referred to in the court transcript as a pledge (i.e., a pawn).

The dispute over Kofi Wuo's estate turned on legacies of slavery and pawning. Outlawed for several decades by the 1950s, slavery and pawning had come to be looked on as shameful features of a bygone era. In Asante it was considered an offense to speak of another's origins, lest it suggest that the person spoken of was of slave descent. While discussion of slavery faded over time, as slaves’ descendants were absorbed into their owners’ families and people refrained from speaking of their past, memories lingered.Footnote 18 Human pawning was also increasingly relegated to the past, both rhetorically and in practice. To disguise the practice from colonial authorities, creditors and debtors spoke of pawning as marriage: money loaned in exchange for a girl or woman as collateral was disguised as ‘bridewealth’. As the cocoa economy expanded, cocoa farms increasingly replaced people as collateral for loans. It is striking, therefore, that in the dispute over Kofi Wuo's estate, Akwasi Kumah not only spoke openly of his mother's enslavement but based his case on the fact of his slave descent. His opponent, on the other hand, ignored claims that her grandmother had entered the family as a pawn, insisting that she, Abena Bimpeh, was Kofi Wuo's ‘niece’.

Plaintiff and defendant articulated their positions differently, but both claimed to be ‘of the same family’ as the deceased. Their stories, in turn, raise questions about the meaning of ‘family’ and family membership, and their significance for relations of property. Who ‘belonged’ to Kofi Wuo's (or any Asante) family, on what terms, and what did different modes of familial belonging mean for individuals’ claims on one another and on the property of family members? While a single case is certainly no grounds for drawing general conclusions, the kinds of information that the court, the litigants, and their witnesses deemed relevant for determining family belonging illustrate some of the ways Asantes understood and argued about the meaning of ‘family’ and familial entitlements on the eve of independence from colonial rule.

The case for Abena Bimpeh, defendant

In presenting her case to the court, Abena Bimpeh asserted that she was related to Kofi Wuo ‘on the maternal side’. She and Kofi Wuo shared a common ancestress, she said — a woman named Bombo. According to Abena Bimpeh, Bombo had given birth to several daughters: one, Ama Dapaa, was Abena Bimpeh's grandmother; another, Afrasu, was Kofi Wuo's mother. Thus, Abena Bimpeh explained to the court, she was Kofi Wuo's niece. Initially, Abena Bimpeh told the court that she was Kofi Wuo's ‘only’ surviving maternal relative, but under questioning she admitted that one of Bombo's granddaughters (Abena Kwabena) was still alive.

If so, the court wanted to know, wasn't Abena Kwabena senior to Abena Bimpeh, and shouldn't she be the one to contest Kofi Wuo's estate? Abena Bimpeh replied that she had been asked by her aunt (Abena Kwabena) to represent her in the case. Pressed by the court for further evidence, she admitted that Abena Kwabena had not given her a formal power of attorney. She added, however, that she (rather than her aunt) was the proper person to administer her uncle's estate because her grandmother (Ama Dapaa) was senior to Bombo's other daughters.

If the judges harbored misgivings about Abena Bimpeh's testimony, their doubts were not allayed by her witnesses.Footnote 19 The first defense witness (hereinafter DW1), a farmer from Amoaful, repeated Abena Bimpeh's claim that she was a descendant of Kofi Wuo's grandmother, but then muddied the waters by adding that Kofi Wuo had no surviving kin when he died. The second witness (DW2), the odikro (head of the village) of Kofi Wuo's hometown Adumasu, also denied that Kofi Wuo had any surviving lineal successor, but then appeared to contradict himself by asserting that ‘Kofi Wuo had relatives’ at the time of his death. Challenged by the court, he dug in his heels:

The presiding judge was not sympathetic. ‘The Odikro should have known all about this case’, he scolded,

because he is the odikro of the town and also a member of the Agona family, but his failure to impress me with the Defendant's geneaological [sic] tree connecting Kofi Wuo's, gives room to doubt in the Defendant's flimsy claim as being the only surviving niece of Kofi Wuo. She only stated that he came and met the Defendant's mother (Yaa Bonsu) in the house of Attah Kojo, this is not a conducive evidence to be believed by me.Footnote 21

Notwithstanding the judge's irritation, for the historian the apparent contradictions in the odikro's testimony are suggestive. Rather than a straightforward case of perjury, the odikro's testimony suggests that Asantes understood the term ‘family’ in more than one way — distinctions that may have been lost in translation.Footnote 22 In the English transcript of the trial, both litigants and witnesses (or their court interpreters) used ‘family’ to refer, variously, to residents of a household, to people related to each other ‘in the maternal line’, and to one or more of the seven or eight dispersed matrilineal clans (ato η) that comprise Asante society as a whole.Footnote 23 Thus, when the odikro testified that Attah Kojo called Abena Bimpeh's mother (Yaa Bonsu) ‘niece’ because ‘they were all of one family’, he did not necessarily mean that she was Attah Kojo's uterine sister's child.

In countering the testimony of the defendant and her witnesses, Akwasi Kumah and his witnesses flatly denied that Abena Bimpeh was a member of Kofi Wuo's matrilineage: ‘She was nothing to Kofi Wuo.’ According to Akwasi Kumah's first witness (PW1), Abena Bimpeh's grandmother, Ama Dapaa, had been pledged to Kofi Wuo's grandfather, Abreabri, for £6.Footnote 24 (Asked when this had happened, PW1 replied that he ‘could not know’ because it happened before he was born. Since he gave his own age as ‘about 83’, this would place Ama Dapaa in Abreabri's household sometime before 1868). Evidently, her family had not redeemed her, because she was still living with Abreabri's descendants when she died circa 1908. In response to questions, PW1 admitted that Kofi Wuo's grandfather had arranged the burial of Ama Dapaa but explained that he did so only because ‘her family were informed, but nobody [from her family] attended the funeral.’Footnote 25 In this case, then, the fact that Attah Kojo took responsibility for Ama Dapaa's burial was taken to mean only that she lived in his household — not that she was a blood member of his matrilineal family.Footnote 26

After Ama Dapaa died, her daughter Yaa Bonsu continued to live in Kofi Wuo's household, remaining there until she died in 1939.Footnote 27 Abena Bimpeh's father then took her to his home in Ejisu, where she lived until she was an adult. Later, she returned to Kofi Wuo's household, but continued to travel back and forth between Adumasu and Ejisu. According to Efua Bombo, a sister of the plaintiff who testified on his behalf, Abena Bimpeh had married ‘more than five husbands’, including a son of Kofi Wuo. Why Efua Bombo chose to bring this information to the court's attention is not clear. Under the rules of matrilineal descent, it had no bearing on Abena Bimpeh's claims to Kofi Wuo's estate, and the judges did not pursue it in examining the witness nor did they mention it in their rulings.

For the court, the main questions to be answered were (1) whether Kofi Wuo had any living matrilineal relatives to inherit his possessions after he died, and (2) if not, who was entitled to his estate? Since Kofi Wuo's siblings had all died before he did, and since Kojo Tano — whom Abena Bimpeh called ‘uncle’ — had relinquished Kofi Wuo's traditional office after it became clear that holding the office would not give him a claim to Kofi Wuo's cocoa farms, Abena Bimpeh evidently saw an opportunity to step into a genealogical vacuum. During the trial, she stated repeatedly that her grandmother and Kofi Wuo's mother were sisters and that she was Kofi Wuo's niece.

The case for Akwasi Kumah, plaintiff

In ruling on the case, the judges focused on the credibility of the litigants and their witnesses, while avoiding making any pronouncement on matters of principle or custom. Citing inconsistencies and outright contradictions in the testimony of the defendant and her witnesses, they set aside her claim to be a member of Kofi Wuo's matrilineal family and ruled in favor of the plaintiff.

But Akwasi Kumah and his brothers were not members of Kofi Wuo's matrilineal family either. In presenting his case to the chiefs’ court, Akwasi Kumah opened his testimony as follows:

My father Attah Kojo went to the N.T.'s [Northern Territories] with his nephew Kofi Wuo. My said father bought 10 slaves 5 were male and the other 5 female. My father married 2 of the female slaves which my mother Abena Kumah was one. He gave one also to his nephew Kofi Wuo, another one to his brother Yaw Tawiah, and the remaining one to his subject Kojo Panin. At times I used to ask my father the relation between him and the defendant's mother called Yaa Bonsu. He replied that he was a member of Agona family while Yaa Bonsu was also from Bretuo family, therefore she was nothing to him.Footnote 28

‘My father made me to understand’, Akwasi Kumah added, ‘that Yaa Bonsu was pledged to his uncle Abreabri . . . and that was why Yaa Bonsu was in the house.’Footnote 29

Notwithstanding the Asante taboo against speaking of a person's slave ancestry, Akwasi Kumah made no attempt to soft-pedal his own origins. Throughout the trial he referred to himself and his siblings as ‘the slaves’. Ordinarily it was considered extremely offensive, even legally actionable, to speak of a person's slave ancestry, but such information was remembered and sometimes invoked as a deliberate insult or whispered to discredit a person behind her back.Footnote 30 In Akwasi Kumah's case, however, his very public declaration of slave ancestry — made in a judicial hearing, no less — appears to have been an intentional appeal to ‘customary’ rules (or at least common practices) of succession.

No matter how closely they were integrated into their masters’ domestic establishments, however, slaves remained vulnerable: they could be pawned, sold, or severely punished if they disobeyed their master's commands.Footnote 31 But they also had some rights. Slaves could own property, including slaves. Moreover, if an Asante died without living matrilineal kin to succeed him or her, the slaves in the house could inherit the property that s/he left behind.Footnote 32 As children of a man in Kofi Wuo's family, Akwasi Kumah and his brothers had no lineal claim to Kofi Wuo's property. On the other hand, customary practice provided a clear path to Kofi Wuo's wealth — if only they could count on it.

But custom could be read in more than one way. Frequently repeated in court testimonies, official documents, and daily conversations, the claim that things had been this way ‘from time immemorial’ was an expression of hope rather than a demonstrable fact. Perhaps in recognition of the risks associated with resting their cases entirely on custom, at the trial both Akwasi Kumah and Abena Bimpeh took care to offer additional grounds to support their claims to Kofi Wuo's estate.

Beyond kinship

The late Kofi Wuo was not a poor man. One witness described him as ‘a great trader’. Others testified that he owned two houses and at least one motor vehicle, along with two cocoa farms that were yielding income at the time of his death. Disputes over the property of an Asante who had died intestate were not unusual during the colonial period or afterwards. What is striking about this case is that not only the assets in dispute, but also the people disputing them, were forms of property. As explained above, the plaintiff and his brothers were sons of a woman whom Kofi Wuo's uncle had purchased as a slave; the defendant was said (by the plaintiff and his witnesses) to be the granddaughter of a woman who had been given to the family as collateral in exchange for a loan. In effect, the question before the court was not which material properties were included in Kofi Wuo's estate (apart from the cocoa farms, these were never enumerated or questioned during the trial), but which human properties were entitled to inherit them?

Whether or not one chooses to believe Abena Bimpeh's claim that she was a blood relative of Kofi Wuo and therefore a matrilineal heir whose claims should take precedence over Akwasi Kumah's, the latter's frank admission that he and his brothers were slaves — a social status the British had outlawed half a century earlier — points to the unsettled meanings of family and belonging in Ghana on the eve of independence. As African intellectuals and politicians, departing British officials, and soon-to-be citizens of Ghana wrestled with the issue of how to build an independent nation that was both modern and authentically African, questions inevitably arose about what independence might mean for individuals’ ties with and responsibilities toward one another, as well as toward the new nation.

While the issue of belonging was never raised explicitly at the trial, the litigants’ testimonies suggest that they saw a need to adduce multiple kinds of evidence to buttress their claims. The ‘slaves’ in particular did not rest their case entirely on the history of their forebears’ actions but added detailed accounts of their own contributions both to the wealth of the deceased and to his family's reputation.

Performing his funeral

Having put to rest Kojo Tano's attempt to parlay his succession to the ⊃kyeame stool into a claim on the deceased ⊃kyeame's property — in particular, his cocoa farms — the Kumah brothers’ next move was to demonstrate their commitment to Kofi Wuo's family, and by implication their claims to authority and entitlement within it, by taking control of his funeral. As a number of observers have commented, an Asante funeral is an occasion for public commentary and display.Footnote 33 Burying the dead is an honor but also an obligation: the pageantry and opulence of the funeral reflect on the stature and accomplishments of the family who perform the ceremonies as well as on the deceased. A funeral is also an occasion for political maneuvering within the family, as people vie for personal reputation and status as well as portions of the deceased's estate. The widely accepted view that the successor is responsible for burying the deceased, at his own expense if necessary, implies that people who do not contribute to funeral expenses are not members of the deceased's family and therefore not eligible to succeed.Footnote 34

Taking or denying responsibility for a funeral thus serves as a signal of social belonging. As one of the presiding judges remarked in his ruling, the fact that Kofi Wuo's burial was performed by the town odikro and his family's slaves implied that there were no surviving matrilineal relatives to bury or succeed him when he died. By refusing to let Abena Bimpeh contribute to Kofi Wuo's funeral expenses, the Kumah brothers weakened her claim to be Kofi Wuo's ‘niece’ and therefore entitled to succeed him or share in his estate.

In a further blow to Abena Bimpeh's case, since ‘no one [from their natal family] came to bury’ either her mother, Yaa Bonsu, or her grandmother, Ama Dapaa, it fell to the family who held them as collateral to take responsibility for the job. That they did so with apparent reluctance suggests that, no matter how much the women's labor and fertility had contributed to the family during their years of service, as pawns they were of little consequence to the family that held them. For their part, Yaa Bonsu and her daughter were apparently eager to end the relationship. When the colonial regime solemnly proclaimed the ‘restoration’ of the Asante monarchy, the women announced that they intended to return to their hometown — hoping perhaps that the restoration would free Asantes from obligations they incurred during the now obsolete interregnum when Asante was ruled directly by the colonial state. For the administration, however, the restoration was intended not to liberate Asantes from colonial rule, but to reaffirm and stabilize the colonial state's authority over them by attaching it to the time-honored institution of the Asante monarchy.

In the event, neither Asante chiefs nor British administrators stepped up their efforts to liberate pawns or others of servile status after the restoration. However boldly Yaa Bonsu and her daughter declared their intention to take advantage of the restoration by, in effect, writing off their relatives’ debt to Kofi Wuo's family and returning to their hometown, evidence given at the trial makes it clear that they were not free to leave until they received permission from the chiefs of Amoaful. They were still waiting in 1939 when Yaa Bonsu died. Since Abena Bimpeh was still living in Kofi Wuo's household twelve years later, it appears that the chiefs simply shelved Yaa Bonsu's request after she died.Footnote 35 Unsurprisingly, Abena Bimpeh made no mention of these events when she laid claim to her ‘uncle’ Kofi Wuo's estate.

Contributing to his estate

Taking responsibility for a family member's funeral expenses placed a significant financial burden on the individual(s) who paid, but it also strengthened their claims both to membership in the deceased's family and to his estate. Celebrating the funeral of a family member was not only an occasion for putting the family's prestige and resources on display and confirming its membership. Managing its debts — both those incurred for the funeral and any outstanding debts of the deceased — also served to constitute and redefine relationships among family members and their standing in the wider community.

Some years before he died, Kofi Wuo incurred a debt of £2,000 after a motor vehicle he owned was involved in a serious accident. Unable to come up with such a large amount, he appealed first to the chiefs of Amoaful, then to his kinsmen, for help in defraying the debt. Rather than offer money, they advised Kofi Wuo to mortgage some of his property — which in this case meant his slaves. The women were pledged to their husbands, raising £1,000 for their master, and the men and children ‘stood surety’ for another £1,000. The slaves may not have had much choice in the matter, but the Kumah brothers evidently saw it as an opportunity. By offering themselves as collateral to secure their master's debt, they demonstrated their claim to belong to the family — as contributing members as well as possessions. In contrast, Akwasi Kumah emphasized, Abena Bimpeh had not been asked to contribute since ‘she is nothing to Kofi Wuo’.

The loan raised by pledging the family's slaves did not clear Kofi Wuo's debt but transferred it to the male slaves and those of his relatives who now held their slave wives in pawn. To pay off the loans and redeem the pawned slaves, Kofi Wuo was advised to establish two cocoa farms and use their proceeds to repay the debt. Again, the slaves enabled him to do this. Some of the male slaves provided labor to clear, plant, and take care of the farms. ‘[B]ecause we are drivers’, Akwasi Kumah explained to the court, he and his brother Kwaku Kumah did not perform manual labor on the farms but contributed money to hire laborers for the job. The women slaves also helped out, planting food crops among the cocoa seedlings to shade the young trees and feed the household while the trees matured. Again, Abena Bimpeh was not asked to contribute.

The family incurred an additional debt of £300 to pay for Kofi Wuo's funeral. Receiving only £80 in donations from guests at the funeral, the slaves paid the balance. Seeking, apparently, to take full credit for these contributions to demonstrate their ‘belonging’ to the family, Kwaku Kumah, the eldest among the slaves, ‘would not allow the debt to be shared’.

Family property, reprise

While the connection was not made explicit in testimony given before the court, the Kumah brothers’ insistence on taking full responsibility for Kofi Wuo's debts and the costs of his funeral point to further power struggles going on beneath the surface of the dispute over his estate. Initially, it will be recalled — before steps were taken to celebrate the funeral or distribute the estate — the chiefs of Amoaful had selected a man named Kojo Tano to succeed Kofi Wuo as ⊃kyeame (‘linguist’) to the chief of Amoaful.

At the time, the Amoaful stool was empty, so Kojo Tano's formal installation was postponed until a new amoafulhene had been selected and installed. When the new chief invited Kojo Tano to come to Amoaful to ‘receive the properties’ of the ⊃kyeame stool, he arrived accompanied by a group of people from his home area of Akyem. Neither Kofi Wuo's sons nor his slaves objected to Kojo Tano's succession to the stool, but they refused to hand over Kofi Wuo's cocoa farms, explaining that the farms were Kofi Wuo's personal property and did not belong to the ⊃kyeame stool. Disappointed, Kojo Tano filed suit against the brothers in the asantehene's court, but nine days later he abruptly withdrew the suit, abdicated the ⊃kyeame stool, and returned to Akyem. Kwaku Kumah then gave the stool to his own nephew.Footnote 36

At first reading, the story of Kojo Tano and the Akyems seems peripheral to the conflict between Abena Bimpeh and the Kumah brothers over Kofi Wuo's property, but further reflection suggests that there was more to this sideshow than meets the eye. Both Abena Bimpeh's mother, Yaa Bonsu, and her grandmother, Ama Dapaa, had been pledged to Kofi Wuo's uncle by someone in the house of Nkansa — a man who, like Kofi Wuo, was a linguist to the chief of Amoaful. Kojo Tano also belonged to Nkansa's house. Did the hasty selection of Kojo Tano to take the late Kofi Wuo's office represent an effort by Nkansa's family to demonstrate their ties to Kofi Wuo's family and lay claim to his estate? If so, their ploy was not successful. Kojo Tano and other members of Nkansa's family reappeared at the funeral, but court records do not state whether they made another attempt to claim part of the estate by offering to pay part of the funeral debt. If they did, Akwasi Kumah's testimony that his brother ‘would not allow the debt to be shared’ suggests that they were rebuffed.

Conclusion

In evidence presented during the trial, Akwasi Kumah's position seems clear: as the sons of a senior man in Kofi Wuo's family and a female slave, he and his brothers had a customary right to inherit Kofi Wuo's wealth if there were no surviving kin to succeed him. To buttress their claim to family membership, the Kumah brothers and their witnesses gave detailed accounts of their contributions both to Kofi Wuo's estate and to his family's prestige. As sons of a slave, they belonged to their masters’ family, but they had also contributed financially and materially to Kofi Wuo's wealth, defrayed his debts, and sustained his family's reputation. In effect, they had not only inherited a place in the family but had also invested in its social and material wealth and, by doing so, strengthened their own claims to its resources.Footnote 37

As presented in the trial, Abena Bimpeh's position was more precarious. Although the judges rejected her claim largely because of inconsistencies and contradictions in her witnesses’ testimony, for the social historian, the uneven quality of her testimony in court is less significant than the lacunae in both her own and her opponents’ accounts of her relationship to the deceased. Was she a kinswoman of Kojo Tano? Was he a rival of Kofi Wuo in the amoafulhene's court? What were the implications and uncertainties of her position as the descendant of a pledge to Kofi Wuo's forebears? Students of the history of debt and subordination in Asante and elsewhere in West Africa argue that while pawns were certainly subject to exploitation, they were in a better position than slaves because they had someone to redeem them, whereas slaves did not.Footnote 38 If, however, a debtor were unable or chose not to repay the debt, the pawn remained in possession of the creditor. If Abena Bimpeh felt that she needed to lie about her relationship to Kofi Wuo, her status as an unredeemed pawn apparently left her with less leverage vis-à-vis her master's family than that of the slaves who invoked their inferior status to make their case.

While a single case does not prove a rule, it can provide insights into larger patterns of social change. Here I briefly list three that are illustrated by this dispute. First, what kinds of complications underlie Wilks’ claim that slaves were ‘rapid[ly] assimilate[d]’ in Asante after the British outlawed slavery in 1908?Footnote 39 Given the widely cited Asante prohibition against speaking of a person's slave ancestry, it is difficult to disentangle intentional social action from mere silence, leaving the full meaning of ‘assimilation’ uncertain.

Second, the English word ‘belonging’ refers both to social inclusion and to ownership or possession — meanings usually construed as separate from or even antithetical to each other. The story of Kofi Wuo's legacy suggests, however, that the line between inclusion and possession was blurred and remained so in practice long after both slavery and human pawning were legally abolished. Rather than insist on treating family membership and family property as legally and morally antithetical, it may be instructive to recognize that practices often overlap and ask how acts of possession and in- or exclusion interacted in particular historical settings. In presenting his and his brothers’ case, Akwasi Kumah suggests that belonging to the family was contingent — subject to strengthening through material and financial investment. Investment in family membership served, in turn, as a form of investment in family property.

Third, the case adds a historical perspective to the point made by several anthropologists that debt is a socially contingent form of wealth. As Parker Shipton, David Graeber, Jane Guyer, Samuel Eno Belinga and others have explained, debts influence social relationships.Footnote 40 A loan creates a relationship between lender and borrower, similar in many ways to an investment in ‘wealth-in-people’. In the past, Shipton writes, Luo acquired livestock and other material possessions not to have them but to build social relationships by giving them away.Footnote 41 Shipton's comments go beyond Guyer's important insight that wealth-in-people is a matter of individuality as well as number. Guyer and Eno Belinga argued persuasively that central Africans valued people for their singular abilities and even non-conforming behavior, as well as for their labor power. Shipton adds that value arises not only from individuals’ actions, but from social interactions as well.Footnote 42 Expanding on Benedetta Rossi's important point that social status is historically contingent, I suggest that belonging be seen as a process rather than a fact. As Akwasi Kumah and his brothers were at pains to emphasize, their contributions to Kofi Wuo's property, solvency, and the costs of his funeral strengthened their claims to membership in his family and inheritance of his estate.

The story of Kofi Wuo's legacy also suggests that the value of wealth-in-people cannot be measured by a single standard. Wealth-in-people encompasses emotional and social as well as economic value, reflecting the personal feelings and experiences of ‘owner’ and ‘owned’ and the significance of particular persons or relationships for an ‘owner's’ position in society. According to Akwasi Kumah, Kofi Wuo had accepted the office of ⊃kyeame only after the amoafulhene had assured him that he had his own slaves and was not interested in using Kofi Wuo's appointment to claim Kofi Wuo's slaves as properties of the Amoaful stool. If accurate, this story suggests that Kofi Wuo cared more about keeping his slaves than he did about attaining public office. In contrast, neither Akwasi Kumah nor his witnesses expressed similar concern for the family's pawns. Attah Kojo and Kofi Wuo buried Ama Dapaa and Yaa Bonsu, they explained, only after the women's own families had failed to claim their bodies.Footnote 43

More broadly, a case in which the claims of slaves outweighed those of a woman who was ‘free’ in principle but bound by the debts of others in practice underscores the value of understanding ‘belonging’ as a process rather than a social fact.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to archivists at the Public Records and Administrative Archives Department, Kumasi and Accra, and to the Librarian at the Council on Law Reporting, Accra, for assistance in gaining access to and locating materials in their collections. Warm thanks to my colleagues in the African Seminar at Johns Hopkins for their insightful and thought-provoking comments on an earlier version of this paper. I am solely responsible for its contents. If you have comments or questions, my email address is: sberry@jhu.edu.