A raging global pandemic handled inadequately and indifferently by the Republican-led US federal government, with Dr. Anthony Fauci in a featured role; an antiracist uprising in response to police brutality; a resurgent political Right fomenting and stoking culture wars; activists’ demands for a diverse and equitable art world; increasing fiscal precarity for small, innovative live art spaces; a looming recession; and an escalating housing crisis fueled by accelerating income inequality: welcome to Los Angeles between 1989 and 1993. In this period, AIDS became the leading cause of death for US men ages 25–44; ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power)/LA called public health infrastructure to account and successfully fought for an AIDS ward at Los Angeles County Hospital.Footnote 1 A widely circulated video of Los Angeles Police Department officers viciously beating Black motorist Rodney King, and their subsequent acquittal of criminal charges by a suburban jury, ignited five days of antiracist rebellion. The rising number of unhoused people in Los Angeles was becoming difficult to ignore, though not for the city's, state's, or federal government's lack of trying. “Multiculturalism” became a widely embraced—if sometimes cynically deployed—aesthetic and programming imperative.

On 1 May 1989, Highways Performance Space, cofounded by artist, critic, and editor Linda Frye Burnham and performance artist and cofounder of the NYC venue P.S. 122 Tim Miller, opened its doors to engage every one of these crises and cultural turns (Fig. 1). This was not an auspicious time to open a noncommercial performance art and gallery space. The Wallenboyd closed as a scrappy downtown L.A. hub for experimental performance the year before, in 1988, and the venerable Woman's Building would close two years after, in 1991. A recession was on the way. In this fraught period, what good could another small, underresourced experimental arts venue offer its audiences? Were these goods sufficient to secure its own survival as many of its contemporaries changed direction or disappeared around it?

Figure 1. Exterior, Highways Performance Space, Santa Monica, CA, 30 April 2019. Photo: Judith Hamera.

Highways’ opening manifesto itself acknowledged the venue's intrinsic precarity, signaling that it might not persist into the coming century.

-

highways is an artists’ community dedicated to the exploration of new performance forms.

-

highways is strategically located at the intersection of art and society.

-

highways is an interchange among artists, critics, and the public.

-

highways is a crossroads, a place of alliances, a new collaboration among cultures, genders, and disciplines.

-

highways is part of an international effort to articulate and work out the crisis of living in the last decade of the 20th Century.Footnote 2

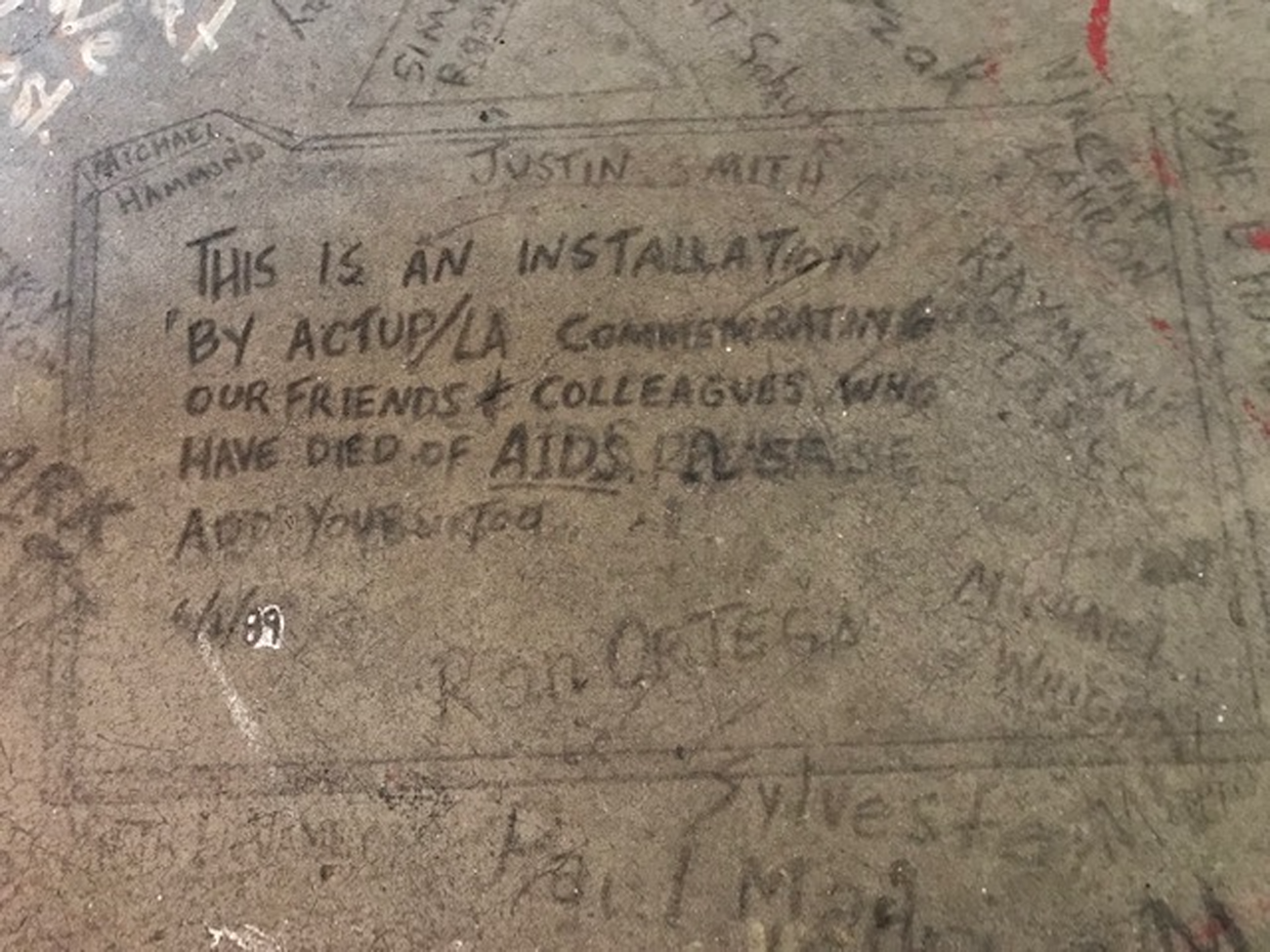

But persist it did, despite NEA defunding that catalyzed the 1990s culture war over federal support for the arts, internal dissension, recessions, gentrification, and the acceleration of a rabidly neoliberal art market. At Highways, you could learn to create a performance piece from the materials of your intersectional life because the entertainment industry could never have imagined you taking the stage. You could view artist Annie Sprinkle's cervix live, then debate relationships between art, sex-positive feminism, and pornography. And, as you moved from its reception area and gallery space into the theatre, you would step on outlined contours of bodies commemorating those who died of AIDS, somberly and sometimes brightly painted with their names, covering the floor: both memento mori and crime scene markers (Fig. 2). Theoretically, you still can, though Highways’ future is uncertain as of this writing. It hosted an ebullient, carnivalesque thirtieth birthday bash in 2019, but its thirty-first was muted due to its COVID-19 closure and economic precarity.

Figure 2. AIDS Memorial Floor, interactive installation. Highways Performance Space, Santa Monica, CA, 25 February 2019. Originating artist: Chuck Stallard, with ACT UP/LA. Concrete, 1989. Photo: Judith Hamera.

This essay takes its title from the apocryphal curse, “May you live in interesting times”—as appropriate between 2020 and 2022 as it was in Highways’ formative years—but it focuses on the crucial differences between Highways’ founding moment and our own, and on the shifting political economic currents that transported us from then to now. These differences are central to understanding the space's social work between 1989 and 1993. I use archival data, interviews with Highways founders and founding artists, and performance texts to advance four interrelated claims.

1. Highways was a counterpublic formation from its inception, with a genealogy that included AIDS activism, especially ACT-UP/LA; lateral solidarity among a diverse group of activist and oppositional artists; and rejection of the neoliberal art market. Its counterpublic status is an important, if likely unsurprising, precondition for the counterpublic goods it organized and offered.

2. Between 1989 and 1993, this formation was transitional in character: positioned between de- and postindustriality in Los Angeles; between modes and programs of live art making; and, most important for the purposes of this essay, between a post–civil rights era liberal pluralist multiculturalism emphasizing individuals’ equality before the law, rather than redress of structural racism, patriarchy, and homophobia, and an emerging neoliberal one that framed and organized intersectional difference in market terms.Footnote 3

3. The counterpublic goods Highways offered its audiences during these years—and offers contemporary historians—include enactments of oppositional transitional subjectivities repudiating both the fecklessness of liberal pluralist multiculturalism and the predations of its emerging neoliberal successor.

4. Works by three foundational Highways artists—Guillermo Gómez-Peña's Border Brujo (1989), Dan Kwong's Secrets of the Samurai Centerfielder (1989), and Keith Antar Mason and the Hittite Empire's for black boys who have considered homicide when the streets were too much (1991)—are especially legible examples of the work oppositional transitional subjectivities did onstage in this period. They acknowledged the ideological liminality of approaches to difference in this specific political economic moment, critiqued both hegemonic options for equity and inclusion on offer, and, in so doing, provided critical affective equipment for thinking against and beyond the liberal/neoliberal diversity double bind. These counterpublic goods become especially clear when set against official civic curations of difference like the 1990 Los Angeles Festival.

Close attention to Highways in its first four years deepens our understanding of relationships between performance and political economic change—especially responses to multiculturalisms in the uneven and discontinuous consolidation of US neoliberalism. Specifically, such attention can spatialize and temporalize relationships between early 1990s performance art and the idea of the public good in Los Angeles's multiculturalist moment that was itself in transition. “Transitional subjectivities” theorizes artists’ strategies and repertoires that critically navigate such structural shifts and, in so doing, serve as a form of critical pedagogy. Finally, examining this small venue in this crucial period productively complicates our understanding of experimental arts venues as more than the boxes in which things of interest happen, and as different from performing arts institutions in the liberal and neoliberal models.

I begin by describing Highways’ founding, structure, and programming, characterizing it as a counterpublic formation using the work of American studies scholar Michael Warner. Next, I turn to the venue's multimodal liminality, with emphasis on the political economic context of its formative years: a period in which post–civil rights era liberal pluralism was quickly giving way to a rapidly consolidating neoliberalism and Los Angeles was becoming a model of a new multicultural “postmetropolis.”Footnote 4 I then review the structure and rhetorical framing of the 1990 Los Angeles Festival as an example of multicultural performance against which Highways’ counterpublic goods can be assessed. I introduce my analyses of works by three of Highways’ core artists by explaining the critical utility of “oppositional transitional subjectivity”: a formulation based on British psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott's “transitional object.” After analyzing these exemplary performances and discussing their critiques of hegemonic multiculturalisms, I conclude by detailing the shifts that ended this formative period and noting the venue's challenges in our own interesting times.

Welcome to Highways

Highways Performance Space was a counterpublic formation from its inception: fueled by founders Linda Frye Burnham and Tim Miller's outrage at the dearth of services for those affected by the escalating AIDS pandemic and discriminatory city, state, and federal actions against the infected; disgust at the L.A. and NYC art worlds’ escalating neoliberalization; and admiration for the work of ACT UP/LA and local activist artists. Both were at liminal points in their careers, and both registered the increasing centrality of market values in the experimental live art scene.

By 1985, Burnham, founding editor of High Performance Magazine, which was devoted to performance art, was heartily sick of the genre, especially what she saw as its increasing intellectual and aesthetic vacuity and a rampant, self-promoting careerism exemplified by a highly visible coterie of white artists seeking mainstream entertainment industry success. Her partner, Steven Durland, described the emerging consumerist attitudes of live art audiences in this period: refusing to sit on the floor, economistically calculating potential time commitments in advance (“It's not too long, is it?”).Footnote 5 Few were willing to attend a four-hour performance piece anymore. After a vapid cabaret at a downtown venue, Burnham despaired: “Performance art isn't anything.”Footnote 6 She resigned as High Performance's editor, with Durland, who had been managing editor, stepping in. Burnham had invested almost a decade in the magazine, and in Southern California performance art. Now she was done, or so she thought.

In the same year, Burnham found new hope in ensemble work created by performance artist John Malpede and the Los Angeles Poverty Department (LAPD).Footnote 7 Malpede was inspired by the Catholic Worker movement and homeless rights activism in L.A. and, with a grant from the California Arts Council, set up theatre workshops in downtown's Skid Row, described then as now as the “‘capital of the homeless’ in the United States.”Footnote 8 Meeting Malpede and seeing LAPD's work led Burnham to other L.A.-area activist artists who focused on race, ethnicity, gender, community, and political economy. She was impressed by their strategic and theoretically informed art making and energized by their example.

A few years later, in 1987, Tim Miller returned to Los Angeles, his hometown, from New York City. He too was heartily sick of arts careerism and corporatism, and energized by the founding of ACT UP/LA in the same year.Footnote 9 Miller joined and created a piece for the group's sustained demonstrations against L.A. County Hospital seeking a dedicated AIDS ward, as described in the opening paragraph of this essay. He was not done with performance art, and even considered taking on the lease for the aforementioned Wallenboyd. Miller was propelled, in his words, “by the urgency and terror of [his] mortality” amid the escalating numbers of gay men dying, and by the potency of the ACT UP model.Footnote 10

Burnham connected with Miller and his then-partner, Douglas Sadownick, to strategize around questions of what activist artists needed. The clear answer was space. Burnham found a suitable location in northeast Santa Monica: a five-building complex, including a warehouse and an auto repair shop, in an area zoned for light manufacturing and artists’ studios on 18th Street between Olympic Blvd. and Colorado Ave. near the intersections of the I-10 and I-405 freeways, hence “Highways.”Footnote 11 Artist, Astro Artz publisher, and High Performance patron Susanna Bixby Dakin purchased the property for what would become the 18th Street Arts Complex, which she and Burnham cofounded, and Burnham handled the logistics of creating a venue on the site.Footnote 12

Tenants of the complex, which included Highways, Astro Artz/High Performance, other nonprofit organizations, and artists’ live–work studios, contributed rent. Burnham figured that the performance space needed to bring in $800/week to cover its rent and expenses.Footnote 13 Used equipment was donated by local theatres and arts organizations, and labor was volunteer: it was a thoroughly DIY operation. Burnham credits Miller with advocating for dance infrastructure, including the installation of a Marley floor over the existing cement. Thirty-one years later, that original floor is still in place. The venue includes a theatre, gallery and lobby area, tech booth and storage loft, offices, kitchen, dressing room, and green room. Official seating capacity is currently listed at between sixty-eight and eighty-eight depending on configuration, but, in practice in its early years, the actual number seated could be much higher, especially for popular events (Fig. 3). The original presentation model was coproduction: the venue and the artist(s) split ticket sales 50–50, with the former providing publicity, box-office staff, and equipment, and the latter designers, board operators, and run crew. Durland videotaped the performances, and Burnham, Durland, and Burnham's daughter Jill lived on and maintained the property. Donations and grants from local, state, and national foundations supplemented ticket income. Burnham and Miller were unpaid artistic codirectors of the venue.Footnote 14

Figure 3. Interior stage, Highways Performance Space, Santa Monica, CA, 26 February 2019. Photo: Judith Hamera.

In its early years as an organization, Highways was—and, I believe, largely remains—a formation rather than an institution. Unlike an institution or bureaucracy, a formation is emergent, contingent, and fluid: unable or unwilling to assume or ensure its own perpetuation. Descriptors signaling conventional organizational structure are notably absent from Highways’ opening manifesto; it is described as a “community,” and “interchange,” a “crossroads,” a “new collaboration.” Highways’ renter status was, and continues to be, a challenge to its persistence, even within the larger complex where it resides. It is not property ownership–based, like Ellen Stewart's La Mama on New York's Lower East Side.Footnote 15 Nor did—or does—it operate on the nonprofit regional theatre model like the Arena Stage in Washington, DC.Footnote 16 The venue had no start-up capital, and lacked a structure of financial investors or committed funders, relying instead on sweat equity, donations, and grants. It did not have established formal relationships with nearby commercial theatres, though it sometimes functioned as an underrecognized and uncompensated incubator for them. Initially, it had no robust organizational hierarchy, instead operating laterally, often improvisationally, and largely through volunteers. Miller recalls that he was never paid for his administrative work at the space.Footnote 17 Burnham and Miller saw Highways as a node in loose local, regional, and global networks of artists, art spaces, and audiences, including those living at the complex, sometimes engaging established national presenting infrastructures.Footnote 18

As a counterpublic formation, Highways was both project-based—advancing its own queer, multiracial, multiethnic agenda as articulated in its opening manifesto—and a way to materialize allied projects by its core artists and others. Burnham and Miller understood their comparative privilege as white artists and prepared for the confrontations essential to oppositional multiracial and multicultural work. As Burnham wrote:

[M]ulticulturalism, for us, did not mean two white people opening the door for minorities, and it did not mean charity work for the less advantaged. It meant we were turning to people from other cultural groups for vital information on the crises we found ourselves surrounded by. It would be a learning experience for all of us, an exchange.Footnote 19

Miller described these exchanges as often “very heated” and generally productive, with notable exceptions.Footnote 20 The primary organizational affect consisted of equal parts exhilaration and exhaustion. Burnham described almost daily crises that ranged from negotiations with the city fire department to artists punching holes in the dressing room walls. At the end of the space's first year, Burnham summarized the state of things:

[A]s Guillermo Gómez-Peña says, you can't heal our wounds without opening them first, and when you approach this work “you unleash the demons of history.” One of the things we learned by then was how deep and aggravated are America's cultural wounds and how much anger is seething just beneath the formica surfaces of this country.Footnote 21

Highways was not a harmonious liberal pluralist utopia where differences were easily subsumed under neutral consensus. It was affectively volatile and demanding for all involved, especially given the robust pace of productions, coupled with limited resources.

In 1989, Highways produced sixty-five events in seven months; it increased this pace through the period examined here. During this time, its roster of presenters included Miller, LAPD, Luis Alfaro, Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Holly Hughes, Dan Kwong, and Rachel Rosenthal, to name only a few. As this list indicates, queer and antiracist activist performers were foundational, with Keith Antar Mason and the Hittite Empire, an ensemble of/for Black men, and Marcus Kuiland-Nazario, ACT UP/LA member and founder of the Latinx gay and lesbian arts organization Viva!, as especially notable examples. Both Mason and Nazario lived at the complex, which was practically a performance art commune. Kwong, who said he was “born as a performer at Highways,” echoed this characterization: “The doors were wide open . . . it was chaotic, marginally in control.” He described an ethos that was “mom and pop,” with “everyone pitching in,” a strong gay presence, and energies around forming new connections across multiple dimensions of difference.Footnote 22 He fondly recalls the opening show as more than three hours long: a direct assault on the consumerist sensibilities Durland saw as infiltrating performance art audiences.

Kwong's observation about energy around diverse connections is borne out by the data on presenters between 1989 and 1993. The venue's quarterly promotional mailer documents the explicit intersectionality of both individual presenters and mixed bills; the complex operationalized the concept as articulated by UCLA legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in Highways’ founding year. Though a full survey of all work presented in this formative period exceeds the limits of this essay, the majority of that work was explicitly oppositional: primarily directed against systemic anti-Asian, anti-Black, and anti-Latinx racism, homophobia, anti-immigration hysteria, sexism, and regressive Reagan and Bush administration policies.Footnote 23 Explicitness applied to more than performers’ emancipatory politics and intersectionality. The work itself was often raw, confrontational, and highly sexualized. Members of Mason's ensemble flipped off audiences. Miller routinely stripped and sat naked in audiences’ laps. The complex hosted parties Miller described as “wild kinky raves . . . where many hundreds would gather for politics, performance, and priapism.”Footnote 24 Durland recalls overhearing an off-site conversation between two gay men talking up Highways as a hot new club scene.Footnote 25 Kuiland-Nazario affectionately recalled the atmosphere of these early years as “anarchic.”Footnote 26 This was most emphatically not Jürgen Habermas's bourgeois public sphere, which privileged rational deliberation guided by an abstemious exclusion of the “private.”Footnote 27

Counterpublic Crossroads

Highways’ origin story, its ACT UP/LA and LAPD genealogy, its DIY volunteer ethos, the queer and racial and ethnic intersectionality of its project, and the fierce oppositional explicitness of the politics, performances, and pleasures sited there attest to its counterpublic position both within the Los Angeles art scene and in the context of national politics during the late 1980s and early 1990s as the Right built on its Reagan-era gains. In Publics and Counterpublics, Michael Warner argues that “[a] counterpublic maintains at some level, conscious or not, an awareness of its subordinate status. The cultural horizon against which it marks itself off is not just a general or wider public but a dominant one.”Footnote 28 As its founding artistic directors attest, Highways consolidated in reaction to homophobic exclusions from public health infrastructure as well as escalating neoliberal arts economy careerism and hegemonic whiteness. Further, Warner notes that a counterpublic's oppositional status “extends not just to ideas or policy questions but to the speech genres and modes of address” that are “not merely a different or alternative idiom but one that in other contexts would be regarded with hostility or with a sense of indecorousness.”Footnote 29 The George H. W. Bush administration's National Endowment for the Arts lent official imprimatur to this counterpublic dimension of Highways when, in 1990, it denied peer-review recommended grants to Miller, Hughes, Karen Finley, and John Fleck—the performance artists known collectively as the NEA 4—three of whom had performed at the venue, and again in 1992 when it denied funding to a Highways gallery show by visual artist Joe Smoke because the gay content of the slides accompanying the proposal was deemed lacking in artistic merit. Finally, Warner notes the aspect of counterpublics especially relevant to a performance space: “Counterpublics are ‘counter’ to the extent that they try to supply different ways of imagining stranger sociability and its reflexivity; as publics, they remain oriented to stranger circulation in a way that is not just strategic but constitutive of membership and its affects.”Footnote 30 This dimension aptly describes Highways’ project of creating queer performer–audience intimacies through shared activist energies, identities, and affinities, as well as the aforementioned cervix viewing, naked lap sitting, priapic partying, and the explicitly critical self-, political, and aesthetic inquiry advanced in its workshops and “anti-panel” discussions.Footnote 31 As I argue later in this essay, the venue's artists also aggressively countered both a liberal pluralist ethos that had proven impotent against structural racism and a neoliberal multiculturalism that commodified cultural difference while further exacerbating racial hierarchies.

Counterpublic Crossroads at a Crossroads

Highways’ demographics, expressive culture, and raw productive anarchy—the who, what, and how of its counterpublic status—are important but insufficient in and of themselves to account for the goods it offered its artists and audiences in its formative period. The when is essential. In its first four years, the venue was also a transitional formation, with its social work deriving directly from its multimodal liminality, including the space itself—stage, club scene, community gathering place—and the genre-blurring work created and presented there. But “transitional” as used here also refers to its founding period: betwixt and between L.A.'s rapidly vanishing industrial base and the global financialization that had yet to cohere fully, and especially between regimes of multiculturalism the city deployed to stage its emerging postindustrial identity. Highways’ founders explicitly described it as a “crossroads” in multiple senses of the term, but its position at the crossroads of these two interrelated political economic regimes made it both a training ground and a showcase for oppositional subjectivities navigating the shifting political economic currents of SoCal and US life, with race and culture at the center of that shift.

In the 1980s, deindustrialization was not simply a Rust Belt problem. Between 1979 and 1981, the Los Angeles Times reported that almost a dozen plants supplying the auto industry shut down in the city. Businesses formerly housed in the complex that included Highways may have been casualties of this wave.Footnote 32 The end of the Cold War, during Highways formative years, led to the contraction of the area's defense and aerospace industries, accelerating job losses in the manufacturing sector.Footnote 33 On the northeast side of Santa Monica, where Highways is located, the glittering office towers housing the entertainment and, later, the tech industries were only beginning to arrive, with MGM's opening in 1993. Multiculturalism—or, as Guillermo Gómez-Peña termed it, “culti-multuralism”—emerged in this period, in part as a post–civil rights era racial logic and in part as a response to accelerating neoliberal globalization.Footnote 34 As postcolonial feminist critic Rajeswari Mohan noted: “Since the 1980s, multiculturalism has proved to be a key player in the domestic and international realignments demanded by recessionary postindustrial economies in the West and the postcommunist global system hailed as the New World Order.”Footnote 35 But in this transitional period in L.A., there was more than one multiculturalism in play.

As critical interdisciplinary scholars Christopher Newfield and Avery F. Gordon note, the liberal pluralist multiculturalism of the 1980s and early 1990s offered “a recognition, however belated, of the fundamentally multiracial and multiethnic nature” of the United States.Footnote 36 It also enabled state actors, including public universities, and the culture industry to incorporate and manage difference by casting enduring post–civil rights movement racial inequality as a problem of persistent white ignorance that could be remediated by education, equal individual opportunity, and basic antidiscrimination measures rather than by dismantling white supremacy. It was an “E Pluribus Unum” project, and operated alongside a significant white racial retrenchment most evident in the passage of California ballot measures that reinforced racial hierarchies.Footnote 37 American studies scholar Lisa Lowe argues that this iteration of multiculturalism was “central to the maintenance of a consensus that permits the present hegemony, a hegemony that relies on a premature reconciliation of contradiction and on persistent distractions away from the incommensurability of different spheres.”Footnote 38 As critical race studies scholar Jodi Melamed notes in her book, Represent and Destroy, under these conditions “forms of humanity win their rights, enter into representation, or achieve a voice at the same moment that the normative [liberal pluralist] model captures and incorporates them.”Footnote 39 The three Highways artists examined here bracingly indicted this iteration of multiculturalism for its unwillingness and inability to confront structural racism, and its accompanying fetishizing and tokenizing of people of color.

Neoliberal multiculturalism both overlapped and eventually largely supplanted this liberal pluralist regime. It redeployed its predecessor's racial logics in service of global markets, posited global capitalism as postracial though thoroughly racialized, rebranded contingent labor as a form of freedom and opportunity, and framed diversity as an abstract market-oriented good for individuals and corporations. As Melamed explains it, drawing on the work of anthropologist Aihwa Ong, with the ascendancy of neoliberal multiculturalism in the mid-1990s,

the dictates of global capitalism have entered into state administrations, so that in order to maximize profitability governments subject populations to different treatments according to their worth within (or their degree of connection to) neoliberal circuits of value. Differentiated citizenship has lead to the dis- and rearticulation of citizenship rights, entitlements, and benefits into different elements whose exercise is then based on neoliberal criteria.Footnote 40

ACT UP/LA and Malpede's LAPD, which inspired Highways’ founders, and the three artists discussed here, repudiated precisely this neoliberal dynamic of differential care and unequal distribution of death, as well as their constituents’ de facto exclusion from liberal pluralist public goods like health care and equality under the law.

Los Angeles was a US epicenter of both multiculturalisms, which were deployed by public- and private-sector leaders to position its greater metropolitan area as “global.” The city rebranded itself as a postindustrial part of the so-called Pacific Rim—conflating geographic and trade relationships while writing over the area's long and fraught history of anti-Asian and anti-Latinx, as well as anti-Black, racism. In the transitional period discussed here, joint civic and private-sector arts initiatives featuring live performance were effective pedagogies for perpetuating liberal pluralist ideals while furthering neoliberal multiculturalism's market-oriented curatorship of a diverse capital-worthy art and citizenship. These events offered some of the “public goods” the artists examined here aimed to counter.

Civic “Culti-multuralism” as Public Good

In its structure and official framing, the 1990 Los Angeles Festival exemplified precisely the mediation of liberal pluralist and neoliberal multiculturalisms Highways artists critiqued in their work; a brief summary of festival elements makes their critiques especially legible.Footnote 41 It was directed by avant-garde media darling Peter Sellars. “The Pacific” was its theme, and it presented “some 150 events,” plus “an additional 400 or more” at an “Open Festival” featuring local artists, over sixteen days.Footnote 42 Many of the performances were free of charge. Descriptions of festival artists on page 3 of the program touted their “worldwide eminence and stature” as “guardians of ancient traditions” and “the foremost innovators of these same cultures.”Footnote 43 First introduced on page 10, L.A. artists participating in the “Open Festival” were framed not as masters or innovators but rather as capital: of pedagogical value to “out-of-town Festival goers” and creative resources for “hometown audiences.” A complete list of these locals was not included in the program. Instead, they were presented in aggregate as “our local arts community,” impressive for their quantity as an undifferentiated “sheer critical mass.”Footnote 44 Ancient and modern, masters and representatives of local cultural capital: the program's distinctions offer a vivid illustration of neoliberal differentiation. Artists were further subdivided thematically according to a curious mash-up of genres, temporalities, and themes: for example, “Puppets, Prayers, Parades,” “Out of the Ruins,” and “Hidden Voices.”Footnote 45 Guillermo Gómez-Peña and LAPD, Highways artists participating in the festival, were listed under “On the Streets: To Get to the Top, Go First to the Bottom.”Footnote 46 That members of LAPD literally lived on the streets, at the bottom of the social order, was, perhaps, lost on the program designers and copy writers or, perhaps, an ill-advised attempt at conjuring gritty authenticity.

The festival program's neoliberal differentiation was framed by rhetoric combining arriviste civic boosterism and liberal pluralist conceits in opening paragraphs that both acknowledged nativist anxieties around the city's multiplicity of differences and echoed colonialist tropes of encounter and conquest:

1990. We've arrived at the last decade of our century and it's a new world out there. With 85 different languages spoken in the Los Angeles school system, it turns out that most of that new world is alive and living right here in this city. And finding out about our ancient and completely contemporary neighbors on the Pacific turns out to be not just the absolutely essential next step toward survival (it certainly is that), but also extremely interesting, occasionally shocking, moving, mysterious, and profound, and again and again a huge amount of fun.

It's our turn now. We are living on the verge of the “Pacific Century.” Los Angeles is going to be the cultural and economic capital of the United States within the next generation. . . . Is this the ultimate Tower of Babel or the beginning of a New Society?Footnote 47

Note the program's explicit pedagogy of pluralist spectatorship: cultural Others are interesting, dramatic, fun. The festival was an opportunity to acquire a “deeper level of information,” thus solving the “white ignorance” problem while networking and building capital. Audiences could “watch, listen, have ideas, make friends, make deals, make tracks, and make a difference.”Footnote 48

Contrast the anxious assertiveness of this festival program with Highways’ opening manifesto emphasizing collaborations and alliances over consumption, boosterism, and differentiation, as well as shared crises “of living”Footnote 49 over a dystopian “Tower of Babel” or a glittering “New Society.” While the festival program posited these latter as the binaries available for conceptualizing cultural and racial difference at a transitional moment, Highways’ core artists rejected both.

Oppositional Transitional Subjectivities Onstage

In contrast to the hegemonic multiculuralisms of the 1990 Los Angeles Festival, Highways core artists created oppositional transitional subjectivities characterized by explicit acknowledgment of their creators’ and the period's multimodal liminality, densely historicized accounts of structural racism and homophobia, and repudiation of both liberal pluralist pieties and neoliberal imperatives.Footnote 50 The “transitional subject” is my variant on psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott's “transitional object,” which produces subjectivity by mediating between self and other.Footnote 51 Performance theorist Richard Schechner used the liminal potential of transitional phenomena to theorize the subjunctive situation of the performer who was simultaneously both “not me” and “not not me.”Footnote 52 “Oppositional transitional subjectivities” combines Winnicott's emphasis on the navigation of ontological betwixt and betweenness essential to subject formation with Schechner's negative framing (“not, not not”) of the performer to posit a position that actively subverts rather than facilitates mediation of two options. Instead of both–and, as suggested by Schechner's construction, it proclaims neither–nor. Its oppositionality is thus twofold: in the refusal to contain or affirmatively resolve a boundary situation and in its explicitly adversarial relationship to, in this case, hegemonic multiculturalisms.

The three artists discussed here were especially foundational for Highways’ counterpublic project in its early years: Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Dan Kwong, and Keith Antar Mason (Fig. 4). All three, though not only these, presented explicitly oppositional transitional subjectivities in pieces, including Gómez-Peña's Border Brujo (1989), Kwong's Secrets of the Samurai Centerfielder (1989), and Mason's ensemble work for black boys who have considered homicide when the streets were too much (1991).Footnote 53 Though their performance styles were very different, all three created pieces that materialized four key elements I argue are essential to oppositional transitional subjectivity in this period. These works explicitly deployed liminality; critically historicized US structural racism in a direct challenge to the pluralist racial amnesia; derided the fictive race-blindness of the pluralist multicultural project; and refused neoliberal multiculturalism's assertion of postraciality as an “attribute of global capitalism itself.”Footnote 54 While the performances themselves were discrete events, their creators’ relative ubiquity at, investment in, and centrality to the venue made them more than one-offs; they advanced Highways’ larger counterpublic project as well as their own.

Figure 4. Highways “Traffic Report” featuring announcements of Border Brujo, Secrets of the Samurai Centerfielder, and a workshop offered by Keith Antar Mason (September–October 1989, 2–3). Photo: Judith Hamera.

Space limitations do not permit me to discuss all three works here, or even comprehensively examine any one of them. Instead, I offer a thematic analyses of Border Brujo, the first one presented chronologically at the venue, as a representative example of the ways these artists and others like them challenged the shifting currents of hegemonic multiculturalisms from within Highways’ larger project. I then briefly summarize the oppositional transitional elements of pieces by Dan Kwong and Keith Antar Mason to highlight their contributions to this project.

Border Brujo: Exorcizing “Culti-Multuralism”

In his solo performance Border Brujo [shaman], which premiered in 1988 and was presented at Highways in its inaugural year, Gómez-Peña conjures—or perhaps channels—a kaleidoscopic range of voices: “Epiphanic,” “Redneck,” “Upper Class Latino,” “Cantinflas-like,” “Authoritative,” and others. They speak, shout, mutter, or howl in English, Nahuatl, Spanish, Spanglish, and sometimes gibberish. The structure of the piece— an introduction and thirty-nine monologues, each delivered in one of fifteen different personae, suggests either a collection of diverse perspectives organized into a thematic unit, like a festival program in miniature, or an explosively animated Tower of Babel; the Brujo deploys and subverts both of these logics to deliver stinging indictments of feckless liberal antiracism and the racialized predations of neoliberalism, sometimes directly, sometimes parodically or ironically. The performance begins at an altar decorated with tequila and shampoo bottles, a toy violin, a megaphone, and other props/ritual objects. Over the course of the show, the Brujo dons a wig, a necklace of bananas, and various hats as he walks in circles, grabs a knife and “stabs” himself, applies makeup, and, ultimately, walks into the audience to collect things for ritual burial at the US–Mexico border. This is a ritual exorcism of hegemonic culti-multuralism, delivered in tongues.

Early in the piece, the Brujo situates himself as a liminal subject in a liminal time, here to address the racist and political economic injuries that shaped him:

Merolico Voice [He howls.]: I'm a child of border crisis

a product of a cultural cesarean

I was born between epochs & cultures

born from an infected wound

a howling wound

a flaming wound

for I am part of a new mankind [sic]

The Fourth World, the migrant kindFootnote 55

This is not the privileged migrancy of well-capitalized tourists or financial elites. It was necessitated by colonialism and accelerated by the predations of global capitalism, as the Brujo makes explicit:

Drunken Voice: I am here ’cause your government

went down there

to my country

without a formal invitation

& took all our resources

so I came to look for them

just to look for them

nothing else

[He drinks from the shampoo bottle.]

if you see a refugee tonight

treat him well

he's just seeking his stolen resources

if you happen to meet a migrant worker

treat him well

he's merely picking the food

that was stolen from his garden (81)

In this moment of encounter “between epochs,” liberal pluralism is an invitation to whitewashed erasure—“Señor Monocromatic / víctima del melting pot” (78)—and its discourse of equal rights worthy only of parodic reversal:

Authoritative Voice [with megaphone]: I toast in equal terms with you

my dear Anglosaxican partner

waspano de tercera generación

in my performance country

República de Arteamérica

you're just a minority

but you have some rights

like the right to listen respectfully

& as long as you continue

to fear moi or desire me

without proportion to my dignity (94)

As these examples make clear, Brujo is no feel-good New Age sorcerer. He's a shape-shifting materialist outing oppressive regimes of domestic (in multiple senses of the term) labor and resource theft from the Global South, and he won't do it quietly.

Authoritative Voice [with megaphone]: dear Californian

we harvest your food

we cook it

& serve it to you

we sing for you

we fix your car

we paint your house

we trim your garden

we babysit your children (81)

Art-world fetishization, consumption, and dismissal of “Chicano performance artists/ in Anglo alternative spaces” (92) come in for especially scathing rebukes that highlight complicity between its libidinal and political economies and those of the state it sometimes purports to critique.

[He speaks elegantly and with a soft-spoken manner.]

Pachuco Dandy Voice: can anyone take a photo of this memorable occasion?

[Pause]

come on, for the archives of border culture

for the history of performance art

can anyone be so kind as to authenticate my existence? (87–8)

To the Brujo, critics and art-world gatekeepers are like stereotypic bigots, only with more pretense and more demands.

[He switches to a redneck accent, speaks through a megaphone.]

Redneck Voice: “no, no, too didactic” . . .

Too romantic, too, too . . .

[He barks.]

Not experimental enough

Not inter-dizzy enough

[He barks again.]

looks like . . .

[He barks.]

Old-fashioned Anglo stuff

I mean not enough . . . picante

[. . .]

I want mucho more (89)

The Border Brujo has no illusions about his own ability to cross the art world's epidermal borders: “if Spalding Gray can go to Cambodia / why can't I come to [city where he is performing]?” (93). Further, Brujo completely understands how neoliberal multiculturalism works hand in hand with this tactical art-world commodification to enable frictionless flows of capital: “thanks to marketing / & not to civil rights / we are the new generation” (89).

Newscaster Voice [with an artificial smile]: this is the year of the Hispanic

Hispanics on MTV

Hispanics on Broadway

Hispanics in Hollywood

Hispanics in the Museum of Modern Art

[. . .]

Hispanics in the Border Patrol

Hispanics in Federal Jail

Hispanics on Skid Row

Hispanics in AIDS clinics

Hispanics in the cemetery (89)

Neoliberal multiculturalism brought the “year of the Hispanic” as a putative public good, but neoliberal governmentality means “under the present Administration / nothing is really administered but death” (91).

When Brujo rants, cajoles, and sobs—when he collects objects from the audience—he is most emphatically not offering his audiences the solace of ritual repair. The wounds he pokes and probes are too deep for that. Instead, Brujo proclaims the racist reality that liberal good manners refuses to acknowledge directly in its festival programs.Footnote 56 “You must be scared shitless of [the nonwhite majority] future,” he tells white audiences who have gathered in alternative art spaces, including Highways. “I've got the future in my throat” (81). The tides of resistance to neoliberal globalization are coming in and white isolationist racism just might be imperiled along with presumptions of white middle-class economic security:

Street-Hustler Voice: you thought there was a border between the 1st & the 3rd worlds

& now you're realizing you're part of the 3rd world

& your children are hanging out with us

& your children & us are plotting against you

Hey mister, eeeh, mister . . . mister

& suddenly you woke up

& it was too late to call the priest, the cops or the psychiatrist (86)

By the end of his ritual, Brujo is too exhausted to be one of the “fun” cultural Others audiences would meet the following year at the Los Angeles Festival. Ultimately, he heads back to “Hell” from whence he came, collecting items from the audience along the way—“money, IDs, ideas, your keys, your sins”—to bury or “become part of my traveling alta.” His parting word is “¡aflojen!” (“loosen up!”) (95).

As communication scholars Michelle A. Holling and Bernadette Marie Calafell argue, Border Brujo offers Chicanx and Latinx audiences “subjectivities as spaces for identification and new identities”: a counterpublic good in itself.Footnote 57 But Gómez-Peña also makes explicit that these subjectivities operate within and against hegemonic systems that ignore, police, and exploit minoritarian subjects while producing “víctima del melting pot” (78). Onstage at Highways during the city's transitional times, he delivered both new options for identity formation and schooling in the psychic and material operations of hegemonic multiculturalisms occluded by pluralist and neoliberal regimes.

The Samurai Centerfielder and Brothers Who Have Considered Homicide

The Border Brujo was a transitional subject who refused pluralist “culti-multuralism” and the market-ready diversity that was coming next. He was not alone. Dan Kwong's Secrets of the Samurai Centerfielder premiered at Highways as part of the series including Border Brujo.Footnote 58 As the title suggests, baseball is central to the piece: both Kwong's personal passion and a metaphor for America's “other” national pastime: racist exclusion. The Samurai Centerfielder's costume, like the Brujo's altar, signals parodic pastiche: “armor” made of carpet padding over a baseball jersey and pants, crowned by a bike helmet festooned with cardboard crescent horns and a baseball at its center. His tone is sometimes earnest, sometimes pedagogical, supported by slides, his own recorded voice-overs, movement—aggressive, athletic, and goofy—and hip-hop beats.Footnote 59

This centerfielder, like Kwong himself, is multiply liminal: both the son of a Nisei mother and Chinese immigrant father and “captain of the outfield” between left and right field. “There is no place the centerfielder does not belong,” he explains,Footnote 60 though one of his “secrets” is that, in America's pastime, some centerfielders belong more than others. The nature of this position is defense. As the Samurai Centerfielder makes clear in his account of white high-school teammate Scott Miller, who routinely and violently fired fly balls at his head, the offense is the white supremacy evidenced in the history of American anti-Asian racism. The Samurai Centerfielder meticulously details the extraction of Chinese labor, the Chinese Exclusion Act, and his maternal grandfather Papa's internment during World War II despite Papa's deep investment in America's pluralist promise and earnest desire to serve as a cultural mediator.

In contrast to neoliberal globalization's differentiated citizenship, reduction of diasporic connections to trade relations, and racist media relegations of Asian nations to sites of cheap labor, the Samurai Centerfielder dreams of a transhistorical ritual performance of diasporic solidarity. He is playing ball at Dodger Stadium with Manjiro Nakahama, the first recorded Japanese man in the United States. He runs for an epic fly ball to the cheers of Vincent Chin, murdered by two white autoworkers in Detroit in 1982; Japanese internees; Papa; and the Chinese student protestors who had occupied Tiananmen Square just months before this performance and were crushed by the Chinese government. Yet, like both the Brujo and Mason's Brothers discussed next, the Samurai Centerfielder refuses both reconciliation and resignation as surely as he refuses the individual heroic dream of the impossible catch. Instead, he acknowledges both despair and a contingent hope. “You want a positive ending?” he asks. If so, it is the audience's collective job to make one. He holds a baseball and extends his hand to the audience. “Take it. It's yours.”Footnote 61

Keith Antar Mason's for black boys who have considered homicide when the streets were too much is the closest in structure to conventional theatre of the three works surveyed here. It builds on genealogies that include the critical Black rage theatre historian Soyica Diggs Colbert theorizes in Amiri Baraka's (LeRoi Jones's) Dutchman,Footnote 62 and the complex landscapes of Black women's intimacies depicted in Ntozake Shange's For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow Is Enuf, to which it directly alludes. Like Shange's canonical work, it is a choreopoem. Like Border Brujo and Samurai Centerfielder, it is multimodal: deploying myth and ritual, hip-hop's percussive rhythms and repetitions, and unsparing political economic critique to probe Black men's relationships to Black women, sexuality, grief, creativity, and solidarity. The work unfolds in a series of monologues and exchanges delivered by six “Brothers,” some of whom have been turned into zombies hovering betwixt and between living and dying. All are identified only by numbers—“jus’ statistics for death rates / and criminal charts”—resonating with the Brujo's observation that the only thing neoliberal governmentality can actually administer is the unequal distribution of death.Footnote 63

The Brothers indict pluralist and neoliberal multiculturalisms as two iterations in the changing same of American anti-Blackness. The myth of individual merit as the answer to structural racism is blown apart by Brother #19's devastating account of racial profiling and racist policing, even as Black identity “could be sold / advertised in essence magazine / and bought at your pawnshop.”Footnote 64 But the play also centers Black joys—lovemaking, play, dancing “too cool jerk revolutionary / to be turned out”Footnote 65—and tales of mythopoetic warrior tricksters like Mozambique, who, as Brother #8 tells it:

Brother #8: . . . had escaped

from hell

and won

jesus's black death robe

and he jus’ wears it

under a moanin’ moon pale whiteFootnote 66

For black boys reflects Mason's commitment to “a dialogue that isn't filtered through a Eurocentric point of view”: connections that are “entirely different from a Eurocentric definition of multiculturalism here in the States.”Footnote 67 Therefore, like the final “collection” in Border Brujo and the Samurai Centerfielder's charge to his audience, the ritual structure of the play does not end with interracial reconciliation; there is no shiny, color-blind postmetropolis. Instead, it presents Black healing as revolutionary revelation, made possible by a chorus of Black voices:

Brother #5: . . . i found god

revealed

unto myself

and i found god in me

and i found me

dark phrases

a dark skinned god

i found me

and I found meFootnote 68

As noted earlier in the essay, these three works were not the only stagings of oppositional transitional subjectivity at Highways in this period; indeed, they were not the only ones created by Gómez-Peña, Kwong, and Mason. Though many of the pieces included autobiographical materials, they were not simply “self” or “auto” performances.Footnote 69 They were political economic master classes in demanding public goods for those who were not liberalism's default subjects and repudiating the hegemonic multiculturalisms on offer in their transitional moment. By historicizing and speaking from their own intersectional antiracist positions, these core artists demonstrated repeatedly that assertions of identity-based politics were not distractions from the predations of globalized capitalism and neoliberal governmentality: they were genealogical critiques of these regimes’ foundations and operating principles. Their work bolstered Highways’ counterpublic credentials while educating the audiences about both its core project and the critical issues of the times: one reason Danielle Brazell, a former venue artistic director and former general manager of L.A.'s Department of Cultural Affairs, called it “my university.”Footnote 70

Another Crossroads, and Another

By 1993, Burnham was ready for a break and a change. She resigned her positions as Artistic Program Director of the complex and Artistic Codirector of Highways, with Miller continuing in the latter role. Durland, who was still editor-in-chief of High Performance, resigned as Executive Director of the complex. They left Los Angeles, exhausted by the demands of a managing a magazine, an arts complex, and a venue at the same time. Defending Highways and its artists from repeated right-wing attacks and shrinking foundation and state funding streams were taking a toll. “The Warriors’ Council,” a social justice collaboration of the core artists organized by Burnham in response to the L.A. Uprising, ended acrimoniously. Given the intensity of the critical investments powering the venue's and artists’ projects, this was perhaps unsurprising; simple pluralist consensus was never likely to be an option. Still, the process was wounding for all concerned. Neoliberal multiculturalism was increasingly ascendant. Kwong noted the shift, recalling Gómez-Peña describing it as a form of “compassion fatigue” on the part of revanchist white audiences increasingly impatient with minoritarian artists’ indictments of structural racism.Footnote 71 There was increasing art-world superficiality and cynicism too; Kwong recalled how obvious it was when programmers sought out artists of color solely to tick off boxes on grant applications. He remembers Miller observing, after the Warriors’ Council implosion, that just because a project didn't work didn't mean it was wrong, adding, “and it doesn't mean we stop.”Footnote 72 There was work to be done and critique to advance, and both the venue and its artists did just that. Though oppositional transitional subjectivities were still produced into the mid-1990s, these artists focused increasingly on identities and predations shaped by neoliberal imperatives, including cresting anti-immigrant sentiment in California.

Highways’ current core mission remains remarkably close to that articulated in its opening manifesto. Executive Director Leo Garcia was cheered at its thirtieth birthday festivities for his indefatigable efforts to advance and expand the venue's founding commitments. Antiracist projects remain central to its work; Patrisse Cullors, cofounder of Black Lives Matter, is one of a new generation of artists who has performed there, creating bracing oppositional subjectivities and practices for new and continuing audiences. But the challenges of surviving the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting budget contractions mark this moment too as transitional: with all the precarity and anxiety intrinsic to the liminal. These interesting times are, if anything, even less auspicious for small experimental live arts spaces than those of thirty years ago. Highways is once again a formation at a cultural and political economic crossroads, and the need for its counterpublic goods as urgent as in its founding moment.

Judith Hamera is Professor of Dance and American Studies at Princeton University, with affiliations in Gender and Sexuality Studies and Urban Studies. Her most recent book, Unfinished Business: Michael Jackson, Detroit, & the Figural Economy of American Deindustrialization (Oxford, 2017) received the 2018 Association for Theatre in Higher Education's Outstanding Book Award, the 2017–18 Biennial Sally Banes Publication Prize from the American Society for Theatre Research, and the 2020 Oscar G. Brockett Book Prize for Dance Research from the Dance Studies Association.