Published online by Cambridge University Press: 08 November 2004

In Atlantic Canada Acadian communities, definite on is in competition with the traditional vernacular variant je…ons (e.g., on parle vs. je parlons “we speak”), with the latter variant stable only in isolated communities, but losing ground in communities in which there is substantial contact with external varieties of French. We analyze the distribution of the two variants in two Prince Edward Island communities that differ in terms of amount of such contact. The results of earlier studies of Acadian French are confirmed in that je…ons usage remains robust in the more isolated community but is much lower in the less isolated one. However, in the latter community, the declining variant, while accounting for less than 20% of tokens for the variable, has not faded away. Although it is not used at all by some speakers, it is actually the variant of choice for others, and for still other speakers, it has taken on a particular discourse function, that of indexing narration. Comparison with variation in the third-person plural, in which a traditional variant is also in competition with an external variant, shows that the decline of je…ons is linked to its greater saliency, making it a prime candidate for social reevaluation.An earlier version of this article was presented at UKLVC-3, held in July 2001 at the University of York, U.K. We thank audience members for comments. We also thank Raymond Mougeon, along with this journal's anonymous referees, for useful comments on an earlier written version. The research was funded by standard research grants awarded to King and Nadasdi by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Studies of both Canadian (e.g., Laberge, 1977; Thibault, 1991) and European French (e.g., Coveney, 2000) show that definite on has almost entirely supplanted the standard first-person plural subject clitic nous in informal French.1

There is variation across Acadian French varieties as to whether the subject “pronouns” constitutes syntactic subjects or verbal affixes (cf., King & Nadasdi, 1997; Balcom & Beaulieu, 1998); we ignore this issue here.

All data cited come from the 1987 sociolinguistic interview corpus for Prince Edward Island French constructed under the direction of Ruth King.

In this article, we examine first-person plural pronominal usage in two varieties of Prince Edward Island French, those of the communities Abram-Village and Saint-Louis, to see whether or not on is in the process of replacing the traditional variant, thereby bringing these Acadian varieties in line with other varieties of Canadian French. We will consider the distribution of the two variants across social categories and also across individual speakers.

According to Brunot (1967:335), je…ons began to be replaced in French in the 16th century. Although it is not to our knowledge attested in (earlier) Quebec French, the geographical distribution of je…ons actually remained widespread in France up to the late 19th century. Flikeid and Péronnet (1989) reported that the Atlas linguistique de la France (1902–1910) shows that most northern varieties still retained je…ons (with o(z) occurring in Picardy and on occurring in the northwest) at the turn of the 20th century.3

Lodge (1998:114) showed je…ons remained in use in pre-Revolutionary Paris; further, the data in the Dialogues révolutionnaires suggest that it was widely used by members of the lower classes (both cited by Coveney, 2000).

In our survey of the literature, we noted a link between the survival of je…ons and the survival of the third-person plural traditional variant ils…ont (e.g., ils parlont “they speak” vs. the standard ils parlent, where the ending is phonetically null).4

Like je…ons, ils…ont is an example of archaic usage surviving in Acadian, appearing in France as early as the 13th century. According to Nyrop (vol. 2, no. 61), ils…ont was in widespread usage in the center-west of France at the time of Acadian emigration from that area.

Our data come from a large corpus of sociolinguistic interviews recorded in 1987 with 44 residents of two small villages in Prince Edward Island. Although French is a minority language in Prince Edward Island, there is one region, Évangéline, that constitutes a French enclave, wherein French is the majority language in a number of small villages. The French of one of those villages, Abram-Village, was chosen for study. There the situation is one of stable language maintenance, with considerable institutional support for French, with most services, such as shops, church, and the post office provided in French, along with French first-language education. The second village chosen, Saint-Louis, is located in Tignish region, where the situation is one of language shift, with French largely restricted to the speech of middle-aged and older residents, and to high-school students enrolled in “French immersion” programs aimed at second-language learners of French. In each community, local residents born and raised in the community conducted sociolinguistic interviews of at least 90 minutes' duration. For the present study, interviews for 22 individuals, representative of the age range of the larger sample and representing both sexes, were analyzed. The interview data for these 22 speakers provided 4572 tokens of first-person plural pronouns with definite reference. Following standard sociolinguistic methodology, cases of indefinite on (e.g., on sait jamais … ‘one never knows’), which do not represent instances of the variable, along with ambiguous cases with respect to the definite/indefinite distinction, were eliminated from the data set.

Table 1 shows the distribution of the two first-person plural pronominal variants by community. We see that use of je…ons is limited in Abram-Village, where the vast majority of tokens contain on, but it has wide currency in Saint-Louis; although it must be noted that nearly a quarter of all Saint-Louis tokens do involve on. When we compare these results to those for a comparable number of tokens for the third-person plural variable (n = 4892), we find that the traditional variant (ils…ont) occurs with 78% frequency in Abram-Village and 83% in Saint-Louis.5

King & Nadasdi (1996) provided a full discussion of the ils…ont variable in Prince Edward Island Acadian, and Dubois, King, & Nadasdi (2003) provided a comparison of Atlantic Canada Acadian and Cajun usage.

Distribution of je…ons versus on by community

In the quantitative analysis of the variable, a number of social factors were taken into consideration that have been shown to condition variation in both majority and minority speech communities, including age, sex, community, language use, French language education, and speakers' position in the linguistic marketplace (cf., King & Nadasdi, 1996; Mougeon & Nadasdi, 1998). Given the different status of French in the two communities, it was necessary to perform separate multivariate analyses for each community, which was achieved in a number of independent runs of goldvarb-2. Table 2 presents the results for Abram-Village. For this community, robust results were obtained for position in the linguistic marketplace, that is, with “how speakers' economic activity, taken in its widest sense, requires or is necessarily associated with competence in the legitimized (or standard, elite, educated, etc.) language” (Sankoff & Laberge, 1978, following Bourdieu). Those speakers with higher marketplace scores tended to use more on and those with lower scores used more je…ons.

Overall results for Abram-Village

The Saint-Louis results are somewhat different, as there is little division among speakers in terms of marketplace. Because, with very few exceptions, only students enrolled in French immersion classes can be said to be influenced by nonvernacular French, the marketplace variable was not included in the analysis of the Saint-Louis data.6

As we have not included data for French immersion students in this analysis, there are no younger speakers (i.e., between 15 and 21 years of age) in the Saint-Louis sample used here. We have found in other research that these young Saint-Louis residents do not control vernacular variants (King, 2000).

Overall results for Saint-Louis

These results are not surprising and mirror the findings of previous work on a number of other morphosyntactic variables in the two communities (cf., King & Nadasdi, 1996). The vernacular variant has much greater currency in Saint-Louis, where external varieties of French have had significantly less impact, as noted previously.

Of the remaining social variables, the most interesting is the differing contributions of speaker sex in the two communities. In Abram-Village, men more so than women favor the traditional variant, but in Saint-Louis, the star tradition-bearers are women: fully 94% of their tokens involve je…ons. This difference is understandable when one considers the sociolinguistic structure of each community. Following Eckert and McConnell-Ginet (1992), we interpret the sociolinguistic behavior of women (and men) within the local context, examining the roles of women in the two communities. In Abram-Village, women are employed in a variety of occupations and take part in voluntary activities in which normative French has status (e.g., school secretary, night school teacher, member of the community theatrical group, etc.). In Saint-Louis, most women do not work outside the home, and, if they do, they work at jobs that are conducted in English. Although the Saint-Louis women are clearly fluent speakers of the Acadian variety, both participant observation and self-report data indicate that they have less contact with external varieties of French than do all the other members of our sample.7

These results are in line with the results of King & Nadasdi (1999), where the Saint-Louis women stood out from the rest of our consultants, in that case, as the most frequent and most innovative codeswitchers.

Although only 18% of the Abram-Village tokens contained the vernacular variant je…ons, both the overall results and the quantitative results by social category mask the fact that what seems to be a declining vernacular variant is not simply fading away. In the following section we examine variation in the usage of individual speakers in this community.

Close inspection of the interviews shows that some Abram-Village speakers have near-categorial or categorical use of on. For example, one resident, Elizabeth,8

All names are pseudonyms.

To illustrate this difference, we turn to some of the Abram-Village individual interviews in detail, beginning with Marie, who was 81 at the time. Marie had gone to school up to grade seven, not atypical for her generation. In her younger days, she had cleaned other people's houses for a living; in 1987, at the time of the interview, she lived in the local seniors' home. Her interview lasted for 90 minutes and covers a wide variety of topics concerning habitual aspects of life in her community, including her family history, childhood games, school, celebration of Christmas and other calendar customs in the old days, her early years of marriage, and, finally, life at the home. The interview contains 159 on tokens and 27 je…ons tokens. Twenty-one, or 83%, of Marie's je…ons tokens occur in the six narratives that she recounted during the interview, five of which were quite short. The numerical results are displayed in Table 4.

Results for Marie

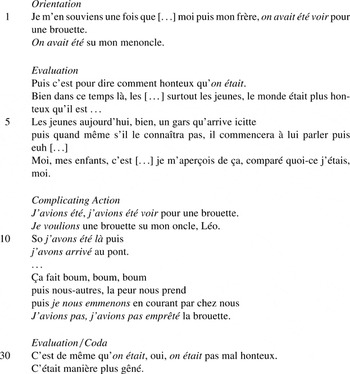

Marie's wedding day narrative is reproduced next. Following Labov and Waletsky (1967) and Labov (1997), each clause is identified by structural type (i.e., abstract, orientation, complicating action, coda, or evaluation).

The wedding day narrative involves going to the church, finding the priest absent, waiting for hours until he returns from performing last rites, getting married at last, and then going home for the wedding meal and dance. This narrative contains ten instances of the variable, all with the je…ons variant; both orientation and complicating action clauses are involved. Je…ons is the only variant that occurs in five of Marie's six narratives. (In the sixth, there are three orientation clauses with on.) In contrast, when Marie is talking outside the narrative context, the vast majority of tokens contain on (156/162), as shown next in two other excerpts, one about dating when she was young and the other about cardplaying at the home.

Next, we turn to Daniel, 45 years old at the time of the interview and the owner of his own construction company. He completed grade 12 at the local high school, and at the time of the interview lived with his wife, Louise, the company bookkeeper, and their children in their own home. Daniel's interview likewise lasts 90 minutes and, like Marie's, covers a wide range of topics. It contains nine narratives. Quantitative results are shown in Table 5. Altogether, Daniel has 224 on tokens and 35 je…ons tokens.

Results for Daniel

Twenty-five of the je…ons tokens occur in narratives. In the narrative reproduced next, Daniel starts talking about the time he and his friends decided to play a trick on a neighbor one Halloween. They went to the neighbor's house around 9:30 pm, but the owners caught sight of them so they went back around two in the morning and played the trick. The next morning, the police were called and went out hunting for the culprits. Although Daniel and his friends didn't get caught, he got the scare of his life.

In the first orientation section, there is a case of indefinite on, on faisait (line 3), not an instance of the variable. Beginning with line 5, there is a series of sixteen je…ons tokens, contained in orientation, complicating action, and evaluation clauses. After a second evaluation in line 34 (J'avais jamais eu si peur/‘I had never been so afraid’), Daniel sums up, moving out of the narrative in lines 35 (les polices, le lendemain matin, ils étiont dans les chemins/‘the police, the next morning, they were cruising around’) and line 36 (puis ils cherchiont les jeunes qu'aviont fait ça/‘and they were looking for the young people who had done it’). In line 37, he says, oh, je sais pas, on faisait…/‘oh, I don't know, we used to…’ and the interviewer overlaps with him with a question: Vous avez fait prendre?/‘You got caught?’. Daniel then returns to a second frame-out (cf., Galloway Young, 1987), the coda, in line 38: J'avons pas fait prendre/‘We weren't caught’. This on faisait/j'avons pas fait sequence is interpretable in terms of the interruption: the question momentarily returns him to the narrative frame. In the text that follows, Daniel clearly has moved on, and there are a number of on tokens immediately following the narrative.

In another lengthy narrative, which likewise recounts events which took place when Daniel was a child, there are five on tokens and eleven je…ons tokens. The beginning and end of the narrative are found below. The on tokens occur at the beginning, in orientation clauses in lines 1 and 2 (Moi puis mon frère, on avait été voir pour une brouette/‘Me and my brother, we went to see about a wheelbarrow’; On avait été su mon menoncle/‘We went to my uncle's’) and in a following evaluation clause in line 3 (puis c'est pour dire comment honteux qu'on était/‘and it's to give you an idea of how shy we were’). These are followed by eleven je…ons tokens, contained in complicating action clauses, such as in line 28 (puis je nous emmenons en courant par chez nous/‘and we ran home’). The final instance of on occurs in line 30, in an evaluation/coda (C'est de même qu'on était, oui, on était pas mal honteux/‘That's how we were, yes, we were pretty shy’). The variable usage displayed may be interpreted in terms of Daniel's framing in and out of narrative.

On the other hand, outside the narrative frame, Daniel uses on almost exclusively, such as when telling of his and his wife's settling in Abram-Village, where he'd been born and raised, after their marriage, excerpted next.9

Although this excerpt does involve the temporal sequencing of past events, it constitutes a report rather than a narrative, as no evaluation expressing the relevance of this account to the present discourse is provided (see Fleischman, 1990; Labov, 1972; Labov & Waletsky, 1967).

We argue that Daniel and Marie's interviews reveal a pattern, whereby je…ons serves as a marker for the performance of narratives of personal experience. An objection that might be raised to this interpretation is that what we are calling narrative versus nonnarrative context might be more accurately considered as a formal versus informal contrast, recalling that in Labovian methodology, the elicitation of narratives of personal experience is a technique for getting at the interviewee's informal style. However, there are a number of arguments against this analysis of our data. First, the contrast obtains even when we consider highly reduced narratives, consisting of only three or four narrative clauses. Second, one good indicator of level of formality in the Acadian context is the frequency with which speakers use words (which they view as) of English origin. In the interviews on which this analysis is based, we detect no difference in such frequency in narrative versus nonnarrative contexts in the insider interviews that serve as our data base.

In Verbal Art as Performance, Bauman (1977:17) discussed the culturally conventionalized means by which members of a speech community key the performance frame. The communicative resources employed may include, among others, figurative language, special paralinguistic features, special formulae, and special codes. Special codes may involve “one or another linguistic level or features”. In the present instance, use of a particular grammatical variant keys the performance of a specific verbal genre, narration. Je…ons is available for such use, as it is, in Cornips and Corrigan's (in press) terms, a low-level morphosyntactic variable, open to social (re)evaluation in a way that high-level variables (e.g., passivity) might not be. In our corpus, narration usually involves narratives of personal experience, but also includes family and community narratives.10

Butler (1991) found that these three types of narratives predominated in his corpus-based study of narratives in a Franco-Acadian community in the mid-1980s.

What of other Abram-Village residents who show mixed usage? In terms of the presence or absence of discursive constraints, two other types of speakers emerge. First, there are speakers who use a significant number of je…ons tokens overall. This is the case of Carole, an 18-year-old high school senior, who uses the traditional variant 80% of the time. Her interview contains two narratives, both of which have je…ons, not on.11

Like many younger speakers, Carole does not produce as many narratives as do older residents. However, her high frequency of je…ons usage across discourse genres is our primary interest.

Second, there are speakers for whom the narrative/nonnarrative split is not as clear as in the case of Marie and Daniel, but who do tend to use je…ons in narrative. This is the case for Sylvie, a 42-year-old letter carrier and amateur actor, who uses this variant 23% of the time. Her interview contains eleven narratives and her use of the variable is shown in Table 6. Here we see a high proportion of on tokens overall, but with je…ons is found somewhat more frequently than on in narratives. However, turning to the individual narratives, we find that two of the eleven have only on tokens, ten such tokens in total. In the remaining nine narratives, there are fourteen on tokens and thirty-four je…ons tokens. In these narratives all but one clause containing complicating action have je…ons.12

The tendency toward use of je…ons in clauses involving complicating action suggests that such usage may involve a foregrounding strategy. Hopper (1979:213) noted that it is “a universal of narrative discourse that in any extended text an overt distinction is made between the language of the actual story line and the language of supporting material which does not itself narrate the main events,” referring to the former as foreground and the latter as background. We thank Jen Smith for pointing us toward this work.

Results for Sylvie

In general, then, contact with other varieties leads certain Acadian French forms to be viewed as substandard. Abram-Village speakers make less frequent use of the vernacular variant, and consequently, use on to a greater extent. However, participating in an education system that extols the virtues of the standard variety results not in widespread use of the standard variant nous, but, rather, in the stigmatization of the traditional variant, je…ons, and rise of the colloquial French on. Saint-Louis speakers, on the other hand, have had little contact with other varieties; they do not appear to consider je…ons to be stigmatized and therefore make frequent use of this form. But stigmatization is only part of the je…ons story. For some Abram-Village speakers, rather than being stigmatized, je…ons has instead become associated with a particular discourse function, that of indexing the performance of oral narrative.

We noted previously that our results confirm a general tendency in Acadian varieties for the first-person vernacular variant je…ons to be less well preserved than the third-person form, ils…ont. It is safe to say that ils…ont (76% of occurrences of the third-person plural variable) has not undergone the fate of je…ons (18% of occurrences of the first-person plural variable) in Abram-Village. We suggest that this discrepancy occurs because the contrast between the vernacular and nonvernacular forms is more marked in the first-person plural than in the third-person plural. A comparison of the two cases shows that what differentiates the two variables is that the first-person variable involves a change in pronominal clitic along with loss of a suffix on the verb (e.g., je parlons vs. on parle), while the third-person case involves (uniquely) loss of the suffix (e.g., ils parlont vs. ils parlent). Further, the retention of the -ont suffix in the third-person plural may be reinforced by the occurrence in the standard variety of high-frequency irregular verbs with -ont, such as aller “to go” – ils vont, être “to be” – ils sont, and avoir “to have” – ils ont. The fact that the first-person plural vernacular variant is highly distinctive, providing a marked contrast with the on variant, seems to be the motivation for its strong association with local norms and its reevaluation, either as a performance key or as a stigmatized variant.

Distribution of je…ons versus on by community

Overall results for Abram-Village

Overall results for Saint-Louis

Results for Marie

Results for Daniel

Results for Sylvie