Introduction

In the past 40 years cognitive behavioural psychotherapy (CBP) has developed and grown into an efficacious treatment for a variety of mental health problems; for example anxiety, depression, OCD and PTSD (NICE, 2004a, b, 2005a, b, 2007; Lane & Corrie, Reference Lane and Corrie2006). At the heart of CBP are the foundations of collaborative empiricism; the client and therapist explore what is happening together, gather information and shape hypotheses over time (Kinderman & Lobban, Reference Kinderman and Lobban2000; Gabbay et al. Reference Gabbay, Shiels, Bower, Sibbald, King and Ward2003; Lane & Corrie, Reference Lane and Corrie2006).

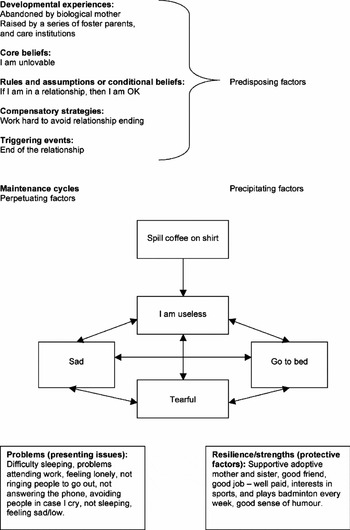

Much has been written about CBP and how formulations are developed that account for the myriad of mental health problems a client might experience. These experiences can shape understanding for the individual about what is happening and how they can work through their presenting problems (Tarrier, Reference Tarrier2006). Appendix 1 details the inter-relationship between these many factors, which include: predisposing factors, perpetuating factors, precipitating factors, presenting issues and protective factors (Lane & Corrie, Reference Lane and Corrie2006). These all provide a vital role in understanding the history of the client, maintenance factors and what resources they have for effective change. However, little attention has been paid to the empirical foundations of formulations.

Although a formulation forms the foundation for understanding the client's difficulties, it is uncertain how much clinicians agree on the components included in its construction. It is unclear how useful a formulation is, how clients understand the process of developing case conceptualization, whether it affects outcome and how much/little should be shared with the client. Beck et al. (Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979) wrote that ‘formulations are at the heart of understanding client difficulties’, yet they have received little attention in how they work and what factors are involved. This is a valuable area to investigate; at present no detailed thematic review has taken place. The purpose of this review is to consider the validity and reliability of the concept of a CBP formulation and their usefulness to clients and therapists.

A variety of literature searches were used in order to identify relevant research papers; further details are delineated in the methodology. A thematic analysis is used in order to address several research questions: How are formulations used in clinical practice? What are clients and clinicians views of their usefulness? Is there clinician agreement on the elements used in a formulation? and Do formulations influence clinical outcome?

In order to make this as rigorous as possible triangulation was used in order to cross- validate the themes that emerged. A discussion follows concerning the themes that have developed, their usefulness in clinical practice and how they can be used to help the client and therapist. Recommendations for future research are considered and how this can be put into practice.

An overview of formulations and their use in CBP

Formulations have received recent attention regarding whether there are differences between individualized and standardized treatment approaches. The evidence to date appears to show that under certain conditions standardized interventions can be as effective as idiosyncratically developed formulations. However, variables such as type of disorder, complexity and client factors can influence efficacy (Schulte, Reference Schulte1996; Eells, Reference Eells1997).

A therapist who adopts an individualized formulation-driven approach is guided by idiosyncratic information provided by the client and has the flexibility to select from a variety of empirically supported models and treatment approaches. If an approach is purely protocol driven the adaptability to the client's needs is limited. However, Herbert & Mueser (Reference Herbert and Mueser1991) contend that it might not be as straightforward as this. The illusion might be that idiographic formulations capture relevant information that aids understanding, treatment and outcome; whereas there is limited research to suggest that formulations lead to better outcome (Bieling & Kuyken, Reference Bieling and Kuyken2003). In fact, Herbert & Mueser (Reference Herbert and Mueser1991) contend that idiosyncratic conceptualizations might be light on theory. Other authors have stated that formulations in ‘real world practice’ might not be used that often, and constitute a learning tool for students vs. a valuable ongoing aid to therapeutic practice (Perry et al. Reference Perry, Cooper and Michels1987).

It is important that clinicians incorporate relevant empirically supported techniques that are appropriate to certain clinical conditions. Mumma (Reference Mumma1998) provides some useful guidelines and recommendations to improve cognitive case formulations and treatment planning; this is particularly the case when the links are made between case formulation and the treatment planning interface.

A number of authors have written about the importance of a client's personal meaning and how they conceptualize their difficulties; their perception of inner and outer worlds and how this links with conflicts at home, within relationships, work experiences and how the client copes with these (Alford & Beck, Reference Alford and Beck1997; Grant et al. Reference Grant, Townend, Mills and Cockx2008). Eells (Reference Eells1997) proposed that case formulation should be seen as a necessary tool in psychotherapy, providing a working hypothesis about complex and contradictory information and helping to guide treatment.

Tarrier & Calam (Reference Tarrier and Calam2002) also contend that a formulation should help guide treatment. However, they emphasize the collaborative relationship between therapist and client and how this shapes the formulation and the therapy that is undertaken. Clients are encouraged to become their own therapist and in doing so uncover how the past relates to the here-and-now; and in turn how a client's current thoughts and images impact on their mood and behaviour (Tarrier, Reference Tarrier2006). Grant & Townend (Reference Grant, Townend, Grant, Townend, Mills and Cockx2008) provide a useful diagram that delineates the situation-emotion-thought-behaviour (SETB) cycle and generic, problem-specific and idiosyncratic models (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Models of case formulation. (From Grant & Townend, Reference Grant, Townend, Mills and Cockx2008, The Fundamentals of Case Formulation, p. 47, reproduced with permission.)

According to the model a formulation is developed together with the client which in its infancy might be generic and move on to become specific to the issues that have been identified, for example with OCD and thought-action fusion (Wells, Reference Wells2003), PTSD and schematic propositional analogue affective representations (SPAARS; Dalgleish, Reference Dalgleish2004) and psychosis and command hallucinations/social rank theory (Byrne et al. Reference Byrne, Birchwood, Trower and Meaden2006). An idiosyncratic formulation follows, which it is hoped provides personal meaning for the client and their individual needs. The cognitive behavioural psychotherapist acts as a guide, as information is explored collaboratively, skills are developed idiosyncratically and implemented according to a sound evidence base (Beck et al. Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979). CBT is now at a point where it is being used with more diverse pathologies such as psychosis and borderline personality disorder; incorporating broader mechanisms such as mindfulness, imagery and acceptance to regulate emotional distress (Palmer, Reference Palmer2002; Pankey & Hayes, Reference Pankey and Hayes2003; Chadwick et al. Reference Chadwick, Taylor and Abba2005).

Methodology

A literature review was chosen in order to explore the efficacy of formulations in CBP. This allowed for the analysis and synthesis of a number of different pieces of research. A post-positivist methodology was adopted which used triangulation. The process involved searching a variety of resources (BNI, CINAHL, Medline, AMED, PsycINFO, Google Scholar, Derby University, Oxford Brookes University, Littlemore and Warneford Hospital libraries). In addition books, journal articles and unpublished work that were identified were reviewed. In order to encourage as large a search as possible an independent reviewer was asked to search using the terms already established and any others they felt would highlight relevant literature.

Having undertaken an initial search of the literature there appeared to be a mix of qualitative and quantitative papers, CASP (2006) was used as a guide in order to consider the merits of each article. Each article was given a rating and only those articles according to CASP guidance that reached a particular threshold were included in the review. At various points throughout the project the independent reviewer was used in order to guide the process. During the analysis, synthesis and theme generation phase the second investigator was asked to view a random selection of articles and a cross-comparison was made of the themes that emerged.

This process has not been adopted in order to produce a ‘final truth’ but in order to check credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability (Lincoln & Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985). It is not that one truth exists but that multiple views can be taken. These in turn might help aid understanding, develop the most appropriate formulation for the client and might have the potential to influence the eventual outcome of therapy for the client.

Identifying themes

On the first reading of each article relevant text was highlighted. On the second reading the whole article was read and it was determined whether the key areas were still relevant. Comments were made as to each theme that emerged. Each article was then looked at according to the highlighted areas and the comments made. The independent reviewer looked at a selection of articles and identified key themes. Changes were made collaboratively according to any differences in interpretation between the first and second reviewer. A table was constructed throughout and reviewed by the author/independent reviewer in order to narrow down the most common themes.

Discussion

How are formulations used in clinical practice?

Although a number of papers have addressed the notion of formulations and their use in clinical settings, the majority have not explored them in ‘real world’ situations. For example Persons et al. (Reference Persons, Mooney and Padesky1995) and Persons & Bertagnolli (Reference Persons and Bertagnolli1999) used audiotapes and transcripts; clinicians in the study were able to look back and forth at what was said. This would not happen in real practice unless sessions were taped. Westmeyer (Reference Westmeyer2003) contends that case formulations provide information that relates to a certain period of time in a client's life, where there is a certain amount of stability for the client's presenting issues to be conceptualized and where certain environmental conditions exist that contribute to the situation. Although Eells et al. (Reference Eells, Kendjelic and Lucas1998) and Chadwick et al. (Reference Chadwick, Williams and Mackenzie2003) used case formulations that were generated very early in the treatment process, in many cases therapists will develop a formulation following a number of therapy sessions and it will not be based on a single meeting; formulations evolve over time (Kinderman & Lobban, Reference Kinderman and Lobban2000).

Westmeyer (Reference Westmeyer2003) also believes that formulations are less able to tell you about more discrete elements that will have shaped their construction. For example, who constructed the formulation and what is their background, what evidence was used in order to validate the formulation that was hypothesized and what measures were used to gather this information. Although these are subtle elements they still might contribute to different interpretations by the therapist and influence treatment. These are important aspects of the formulation process and it is important that they are acknowledged and accounted for in order to provide consistency.

What seems to emerge is that there are a variety of intra, inter and external factors that can influence the clinicians mode of working. These need to be borne in mind. Until recently, the idea of generating a formulation has been seen akin to a road map of the client's difficulties (Johnstone & Dallos, Reference Johnstone, Dallos, Lane and Corrie2006). As such it is seen as valuable to the client and therapist as it provides them with gradual understanding and can guide them on their journey. However, a map only provides the map-reader with relatively basic information and does not give them topographical detail and conditions on the route. Taking this analogy further, navigating a particular route might need certain skills and might vary depending on the journey (inter-city vs. rural). Kuyken et al. (Reference Kuyken, Fothergill, Meyrem and Chadwick2005) notes that with less experienced practitioners manualized treatments could help them formulate more effectively. As might the use of client actors and computer-assisted learning programmes (Caspar et al. Reference Caspar, Berger and Hautle2004; Osborn et al. Reference Osborn, Dean and Petruzzi2004). Experienced practitioners might also gain benefit from CBP formulation guidance (Eells et al. Reference Eells, Kendjelic and Lucas1998; Mumma, Reference Mumma1998; C. D. Fotherill & W. Kuyken, unpublished observations), multiple judge perspectives (Persons et al. Reference Persons, Mooney and Padesky1995; Persons & Bertagnolli, Reference Persons and Bertagnolli1999) and driver feedback (the client) (Chadwick et al. Reference Chadwick, Williams and Mackenzie2003). There is certainly a lack of research with respect to the latter in CBP and a more comprehensive qualitative and quantitative research base would be welcome.

What are clients and clinicians views of their usefulness?

A study undertaken by Chadwick et al. (Reference Chadwick, Williams and Mackenzie2003) highlighted the fact that clients appear ambivalent about formulations. In some cases clients did find the process helpful, some found it distressing (in that they had to explore their problems in detail) and others had mixed views, indicating that it was both beneficial and upsetting at times. Clinicians appeared to find it more indicative of developing a good therapeutic relationship and outcome than clients did. Chadwick et al. (Reference Chadwick, Williams and Mackenzie2003) focused their research on clients who were experiencing psychosis and it is uncertain if this can be generalized to other mental health conditions.

Zuber (Reference Zuber2000) points to the fact that a client's view of their problems appears a better indicator of outcome than more formalized methods of assessment such as DSM-IV-R (APA, 2000). CBT contends that it is based on collaborative empiricism; a shared understanding of the problems and an explanation is developed as to how these are maintained. When this is successful the client and therapist work in partnership, this is seen as analogous to a scientist approaching a scientific problem (Dudley & Kuyken, Reference Dudley, Kuyken, Lane and Corrie2006).

However, there is limited evidence to support the idea that clients find the process of formulation useful. Friedman & Lister (Reference Friedman and Lister1987) propose that a formulation can be many things; it can organize, help with empathy and perform as a research tool (it helps generate hypotheses that can be tested). It is less clear what it offers the client. Townend & Grant (Reference Townend, Grant, Grant, Townend, Mills and Cockx2008) offer a useful overview of the value of assessment and formulation as many other authors have before them (Eells, Reference Eells1997; Wells, Reference Wells2003; Tarrier, Reference Tarrier2006). However, although highly useful and informative there is still a distinct lack of clarity as to what the client finds the most useful and the most unhelpful. It is probably true that many of the components identified such as educational information, what can be done to help, identification of vicious circles and instilling hope, are useful to the therapist and client. It would also be valuable to know what is the most valued aspect of the process and indeed whether this is about the formulation itself or, moreover, what it engenders. As Chase Gray & Grant (Reference Chase Gray and Grant2005) note, there is a distinct lack of the client's voice in the literature. It might be less about here-and-now cycles and more indicative of being heard and understood.

Is there clinician agreement on the elements used in a formulation?

The majority of literature that relates to formulations has tended to focus on validity and reliability. Persons et al. (Reference Persons, Mooney and Padesky1995), Persons & Bertagnolli (Reference Persons and Bertagnolli1999); Eells et al. (Reference Eells, Kendjelic and Lucas1998) and Flitcroft et al. (Reference Flitcroft, James, Freeston and Wood-Mitchell2007) have all identified that to a certain extent clinicians find it easier to agree on specific here-and-now problems, but find it more difficult agreeing on deeper beliefs that the client might hold. Research by Flitcroft et al. (Reference Flitcroft, James, Freeston and Wood-Mitchell2007) found that three constructs were identified in relation to developing a formulation, which were state (here-and-now information), process and function (how the behaviours operate for the client) and trait factors (innate aspects of the client's personality). In their research when more judges (clinicians) were used to identify beliefs and assumptions that the client might have, reliability increased. When clinicians are given the option of choosing from a list of suggested adjectives that describe how the client might view themselves, others and the world; agreement improves (Persons & Bertagnolli, Reference Persons and Bertagnolli1999).

In addition to these factors therapist type and length of training, their experience and heuristics might affect their ability to develop an effective and useful formulation. As Kuyken (Reference Kuyken and Tarrier2006) asserts, clinicians tend to develop decision-making biases and this will impact on the formulations that are constructed. Consequently developing a formulation that several clinicians will agree with is complex and multi-faceted.

Other authors have pointed out (Persons et al. Reference Persons, Mooney and Padesky1995; Kuyken et al. Reference Kuyken, Fothergill, Meyrem and Chadwick2005) that instead of attempting to improve inter-rater reliability it might be more prudent to improve the use of formulations and promote guidelines so better quality conceptualizations can be used in practice. Mumma (Reference Mumma1998) and C. D. Fotherill & W. Kuyken (unpublished observations) have developed specific frameworks in order for better quality formulations to be generated. These include a number of suggestions: generating alternate hypotheses/models and their ability to explain the presenting client issues, setting up testable predictions and videotape sessions, and reviewing the adequacy of treatment interventions. If these approaches are used more readily it opens up the possibility that the diverse needs of the client will be idiosyncratically addressed, for example issues related to gender, age, educational level and ethnicity. Although as more robust guidelines are provided and adhered to, reliability might increase, it is also possible that the best-quality and most useful formulation for the client might be missed.

Do formulations influence clinical outcome?

Persons et al. (Reference Persons, Curtis and Silberschatz1991) proposed that formulations in themselves can influence clinical outcome. What they suggest is that it might be less about the interventions/techniques used and more about the process of developing a formulation. It might also help the creation of a good alliance, understanding of past and present factors and the self-efficacy that develops. However, their research used a single case only and the therapeutic modalities that were explored were very similar (CBT and psychodynamic psychotherapy). It is therefore unclear how generalizable this is to other types of therapies and their respective formulations.

Gabbay et al. (Reference Gabbay, Shiels, Bower, Sibbald, King and Ward2003) hypothesized that better therapist and client agreement would lead to better clinical outcome. This was not clearly shown and what appeared most significant was the therapeutic relationship and its impact on outcome. Gabbay et al. (Reference Gabbay, Shiels, Bower, Sibbald, King and Ward2003) point out, that it is not about agreement per se (related to the formulation) but agreement that the client's problems are psychological and that treatment is needed. This acceptance by the client then leads to a commitment to the therapeutic process. What it does point towards is that it relates to some aspect of the therapist–client relationship. Indeed, it might not be possible to reduce it down to one facet, as many might be involved. Persons et al. (Reference Persons, Roberts, Zalecki and Brechwald2006) explored whether formulation-driven CBT using empirically supported treatments (ESTs) was comparable with data from studies in the field. They found that when formulation-driven CBT was used, on the whole it was comparable with ESTs. Persons et al. (Reference Persons, Roberts, Zalecki and Brechwald2006) proposed that for clients who are experiencing anxiety and depression and who require multiple therapies ESTs guided by formulation-driven therapy is beneficial. Although this does point to formulations aiding treatment it is very difficult to identify whether conceptualizations in themselves are a vital component or whether it is the process and what this involves that helps client outcome.

A thorny issue at the moment relates to competition between case-driven formulation and standardized protocols. Schulte et al. (Reference Schulte, Kunzel, Pepping and Schulte-Bahrenburg1992) is readily cited as having shown that standardized protocols are superior to individualized treatment. However, J. B. Persons (unpublished observations) contends that the two do not differ. She does not believe that there is compelling evidence that formulation-driven treatment leads to worse treatment. Work by Emmelkamp et al. (Reference Emmelkamp, Bouman and Blaauw1994) and Jacobson et al. (Reference Jacobson, Schmaling, Holtzworth-Munroe, Katt, Wood and Follette1989) show differing results. The former states that individualized treatment was not more effective than standardized treatment. However, Jacobson et al. (Reference Jacobson, Schmaling, Holtzworth-Munroe, Katt, Wood and Follette1989) state that in their 6-month follow-up the standardized group showed greater deterioration.

However, in some cases treatment protocols are not available for certain conditions (J. B. Persons, unpublished observations) or when comorbid conditions exist (Tarrier & Calam, Reference Tarrier and Calam2002). Even when they are available in some instances clinicians do not clearly follow the set guidelines (J. B. Persons, unpublished observations). When this becomes the case it raises the issue that the approach is not standardized and therefore this questions the validity of the treatment approach and its outcomes. In real-world practice standardized approaches are difficult to apply and adhere to. One possibility is that some clients who have certain types of problems, that are complex and multi-modal might benefit from what an idiosyncratic formulation can give them.

As has already been discussed, the formulation might serve as a vehicle for other valuable components of the therapeutic process. The therapeutic relationship is seen as an important facet of undertaking therapeutic work (Luborsky et al. Reference Luborsky, McLellan, Woody, O'Brien and Auerbach1985; Svensson & Hansson, Reference Svensson and Hansson1999). Hope is also a vital component in forging a way forward (Snyder et al. Reference Snyder, Michael, Cheavens, Hubble, Duncan and Miller1999). These are not exclusive but important elements that aid understanding, learning and the changes that need to take place for the individual to move forward. The formulation acts as a vehicle in order for this to take place. Bearing this in mind it is important that formulations are assessed in relation to their effects on outcome, but in addition what factors aid this process.

Conclusions

This review has explored what factors might contribute to the usefulness of conceptualizations and what evidence exists concerning the impact they have on client outcome. The themes that seem to emerge are that there is limited research in the field of formulations and their efficacy (validity, reliability, impact on outcome). A disproportionate amount of studies have addressed the area of inter-rater reliability. There is some evidence to suggest that formulations can improve clinical outcome, but this might not necessarily be about reliability but potentially about the ‘quality’ of the case conceptualization and the relationship forged with the client. Very little is known about what the client values in a formulation and this requires further investigation.

The review has used aspects of triangulation so that the themes generated are credible and confirmable. An independent person reviewed a selection of the research in order to cross-validate themes; however, only a selection of papers were used. More papers could improve accuracy as might more people reviewing. However, this is a thematic review and is attempting to glean a general trend not a universal final truth but to explore themes in relation to formulations in CBP and other therapeutic practice.

It is clear that more work is needed in order to validate formulations in clinical practice and answer some of the questions posed at the beginning of this research project. What is clear is that there is some evidence to suggest that they aid outcome, are useful to practitioners/clients, and some aspects of reliability exist (for the most part here-and-now problems). The recommendations detailed below will help develop further understanding and establish a more rigorous approach to real-world formulations in practice.

Recommendations

• To explore the concept of formulations with client focus groups who experience a variety of mental health problems. This will help uncover how clients feel about formulations, what elements are important and which are less vital.

• Mumma (Reference Mumma1998) and C. D. Fotherill & W. Kuyken (unpublished observations) have developed formulation guides that might improve the quality of formulations. These could be researched in practice with more complex clients.

• To update current formulation guides for use with both newly qualified and experienced practitioners

• Reliability can be improved through better training in formulations and how these are translated and maintained in practice. Using multiple judges' perspectives, videoing sessions, group/peer supervision and assessing stability of formulations over time.

• To provide a variety of methods that might aid conceptualization understanding and its implementation. Using teaching, computer packages and actors in order to enhance the transition from theory to practice.

• A number of articles have indicated the benefits of having a standard list of beliefs/assumptions that the client might have, that can be chosen by the clinician. This produces better inter-rater reliability and as a consequence this could benefit more novice practitioners who are less experienced at gathering idiosyncratic client beliefs.

Appendix 1. An illustration of a longitudinal formulation

(cited in Lane & Corrie, Reference Lane and Corrie2006, p. 29)

Declaration of Interest

None.

Learning objectives

• An overview of the function of formulations in cognitive behavioural psychotherapeutic practice.

• To explore the differences between standardized and idiosyncratic conceptualizations.

• Provide a detailed analysis of the evidence base for formulations.

• Assess the themes that emerge across studies and to make recommendations for future research and practice.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.