Introduction

High Secure (HS) healthcare facilities are tasked with safeguarding the public, promoting patient recovery and reducing risk of future harm (Tapp, Perkins, Warren, Fife-Schaw and Moore, Reference Tapp, Perkins, Warren, Fife-Schaw and Moore2013). Typically those admitted to such facilities are detained without limit of time, pending successful treatment and risk reduction (Great Britain, Reference Great1983, Reference Great2007). Context, legal status, offence related factors and poor treatment response support population specificity arguments (Bentall and Haddock, Reference Bentall, Haddock, Mercer, Mason, McKeown and McCann2000). These often preclude the efficacious application of non-forensic-derived psychological intervention protocols (Nijman, De Kruyk and Van Nieuwenhuizen, Reference Nijman, De Kruyk and Van Nieuwenhuizen2004). Barriers relating to insight, psychological mindedness, adherence and complexity are particularly acute within HS contexts (Laithwaite et al., Reference Laithwaite, Gumley, Benn, Scott, Downey and Black2007). Per capita treatment costs are also amongst the highest in healthcare and prolonged detention periods diminish the likelihood of successful rehabilitation (Fineberg et al., Reference Fineberg, Haddad, Carpenter, Gannon, Sharpe and Young2013). Efficacious contextual and population specific adaptations are therefore essential to enable recovery, safeguard the public and offer value (Benn, Reference Benn, Kingdon and Turkington2002; Steel, Reference Steel2008).

Non-forensic derived guidance stipulates that cognitive behavioural therapy should be routinely offered to people with a history or current experience of psychosis (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2014). This approach has proven efficacy in non-forensic samples as an adjunct to pharmacological interventions (Burns, Erickson and Brenner, Reference Burns, Erickson and Brenner2014; Wykes, Steel, Everitt and Tarrier, Reference Wykes, Steel, Everitt and Tarrier2008), and as an effective alternative (Morrison et al., Reference Morrison, Turkington, Pyle, Spencer, Brabban and Dunn2014; National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH), 2014). At its core is the premise that cognitive behavioural techniques can effectively challenge psychotic content and enhance empowerment, thereby reducing distress (Morrison, Renton, Dunn, Williams and Bentall, Reference Williams2004). As a result of wider guidance most HS hospitals include cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis (CBTp) within their treatment options (Slater, Tapp, Dudley, Cooper and Cawthorne, Reference Slater, Tapp, Dudley, Cooper and Cawthorne2014). Yet despite the related implications, little is known about the adaptations to CBTp the HS context necessitates, nor the derivation, application or effect of these (Laithwaite et al., Reference Laithwaite, O'Hanlon, Collins, Doyle, Abraham and Porter2009). Previous systematic literature searches using standard psychiatric and psychological databases with Cochrane search parameters have repeatedly failed to identify a significant body of HS CBTp research evidence (Laithwaite, Reference Laithwaite2010; Jones, Hacker, Cormac, Meaden and Irving, Reference Jones, Hacker, Cormac, Meaden and Irving2012; Tapp et al., Reference Tapp, Perkins, Warren, Fife-Schaw and Moore2013). We therefore hypothesized that an exploratory review that included fugitive literature might yield sufficient alternate studies to help inform discussion within the field and offer important insights (Pappas and Williams, Reference Pappas and Williams2011).

Aims

This exploratory review aimed to identify CBTp approaches used in HS Hospitals and appraise impact. The objectives were fourfold:

-

1. To identify a wider body of HS CBTp studies;

-

2. To analyse the identified studies with regard to application, impact and value;

-

3. To offer a synthesized algorithm of HS CBTp intervention strategies according to perceived efficacy;

-

4. To compare HS practices with non-forensic derived CBTp guidance.

Method

The review necessitated an innovative strategy to identify, appraise and analyse a wider body of HS CBTp literature than had previously been considered; i.e. one that included published peer and non-peer reviewed articles as well as unpublished local studies. This decision to include fugitive literature evolved from Dewey's pragmatist concept of research inquiry (Morgan, Reference Morgan2014). Dewey hypothesized that emotions drive and are the product of an ever evolving cycle of solution focused beliefs and subsequent actions. Through our own professional work we were aware of literature produced by experts in the field that was not being identified through standardized search criteria. We believed that this body of work was worth reviewing in order to gain as complete a picture as possible of applied HS CBTp. Fugitive literature can be difficult to define, source and analyse. Concerns have been raised about rigour, standardization and lack of review (Mahood, Van Eerd and Irvin, Reference Mahood, Van Eerd and Irvin2014). Proponents argue inclusion can reduce “file draw” publication biases and enhance rigour, can uncover important perspectives that might otherwise be lost, and can offer insights that are more relevant to stakeholder concerns (Rosenthal, Reference Rosenthal1979). These differing considerations were borne in mind when we completed this review.

Due to its emergent status, strategies for identifying, interrogating and including fugitive literature within a review are underreported (Mahood, Van Eerd and Irvin, Reference Mahood, Van Eerd and Irvin2014). We therefore developed a novel strategy that combined iterative and hermeneutic processes. This approach offered greater flexibility whilst remaining sufficiently rigorous to allow a repeatable synthesis of the literature so as to inform discussion and offer new insights (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, Reference Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic2010).

Initially, the search process involved examining papers with which we were already familiar. We then checked the reference lists for further sources and contacted the authors of all the identified papers, asking them if they were aware of further research in the field. We asked if they had further contacts in the field who might have additional past or current research that met the search criteria. This process continued until we were certain we had exhausted all possible leads and sources of further literature. Inclusion criteria were initially kept as open as possible to ensure identification of all possible relevant literature. Sources that described HS CBTp interventions, but offered no evaluation, were subsequently excluded. No other exclusion criteria were applied. HS CBTp was defined as any CBT intervention (Curran, Houghton and Grant, Reference Curran, Houghton, Grant, Grant, Townend, Mulhern and Short2010), applied to psychosis, in HS hospitals or their international equivalents.

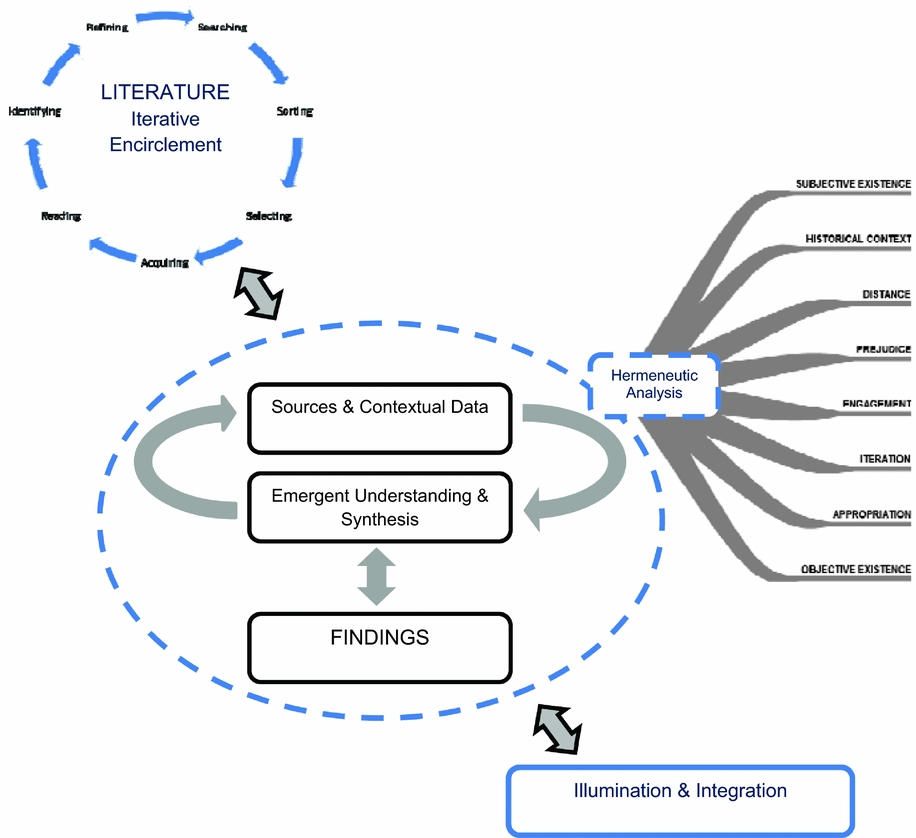

A hermeneutic analysis of the identified studies was utilized on the grounds that it would facilitate a greater depth of understanding and a less opaque appraisal of a developing evidence base (Patterson and Williams, Reference Patterson and Williams2002). This approach asks the researcher to engage in a process of self-reflection on the literature. Specifically, the biases and assumptions of the researcher are not bracketed or set aside. Detached objectivity is not the goal as in more systematic review approaches, but rather the reviewer's assumptions are embedded into the process and are seen as essential to an interpretive process (Laverty, Reference Laverty2003). The researcher gives consideration to their own experience, professional knowledge and makes explicitly clear the ways in which their position or experience relates to the issues being reviewed and is influencing their understandings, on an ongoing basis. The review process thus involves reading the literature, considering its content, context and the meanings generated. It involves asking further questions and necessitates a rereading of the paper from a new perspective to answer these further questions. This process is known as the hermeneutic cycle (Laverty, Reference Laverty2003). The overall study design and process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. A summary and illustration of study method – based on and with elements adapted from Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic (Reference Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic2010) and Patterson and Williams (Reference Patterson and Williams2002)

Results

The 14 sources identified through the iterative search strategy are provided in Table 1. The sources indicate that a variety of CBTp interventions are provided internationally within HS hospital contexts. These are offered to recently admitted, medium dependency, rehabilitation and chronic long-term patients and include group and individual therapy and CBTp linked milieus. The chaotic spirals of encirclement from which meaning is derived within hermeneutic analysis have been condensed for the purposes of this paper and sources ordered according to mode. In order to encapsulate hermeneutic exploration and aid transparency, the authors’ interpretation of each source is offered for scrutiny against the meanings original authors may have intended and those others may make (Patterson and Williams, Reference Patterson and Williams2002). Inferences for each mode are then extrapolated (Boxes 1–3) and the subsequent nascent appraisal is finally described.

Table 1. Identified CBTp papers with High Secure Services

Group CBTp

Interpretations

Williams, Ferrito and Tapp (Reference Williams, Ferrito and Tapp2014) used a controlled trial, between-subjects design to evaluate group CBTp at Broadmoor. Developed from a published treatment manual (Williams, Reference Williams2004), the modular intervention adhered to NICE guidance (NICE, 2009). In a similar Dutch study, Hornsveld and Nijman (Reference Hornsveld and Nijman2005) used a between-subjects design to evaluate the impact of group CBTp, and in three further studies CBTp focused groups included a self-esteem group (Laithwaite et al., Reference Laithwaite, Gumley, Benn, Scott, Downey and Black2007), a compassion focused programme (Laithwaite et al., Reference Laithwaite, O'Hanlon, Collins, Doyle, Abraham and Porter2009), and a psycho-education intervention (Vallentine, Tapp, Dudley, Wilson and Moore, Reference Vallentine, Tapp, Dudley, Wilson and Moore2010). An interpretation of these studies with regard to method, patient group, mode of delivery and main results is offered in Table 2. Subsequent inferences are shown in Box 1.

Box 1. Group inferences

-

• Control trials for psychological therapies are possible within HS contexts

-

• Within-subjects study designs are more frequent

-

• Only one study adopted a mixed methodology

-

• Groups were modularized and designed to target all or specific psychosis experiences

-

• Groups for specific experiences were shorter and less intensive

-

• Individual sessions were needed to supplement group sessions

-

• Only one group format specifically involved families

-

• Groups were facilitated by specialist nursing staff alongside clinical, trainee and assistant psychologists

-

• Senior psychologists and protocol authors maintained model fidelity via supervision and involvement

-

• Only certain HS patients participate in group work

-

• Participants were recruited over a number of years, usually over a number of cohorts

-

• Participant numbers remained proportionately small with regard to statistical analysis.

-

• There were large differences in length of treatment between groups (10 – 70+ sessions) and in session composition

-

• Some studies also offered details of how confounds such as concurrent treatments, had been controlled

-

• Most participants had chronic psychotic disorders and index offences of manslaughter or murder

-

• Participants were male

-

• With the exception of the De Kijvelanden study, mean participant length of stay was similar to that expected for discharge to conditions of lower security.

-

• Non-participants/drop-outs had comparatively chronic (9+ years) or short (1.4 years) lengths of stay

-

• General pre-group levels of psychotic symptoms were low or remitted

-

• Levels of pre-group esteem were generally normal

-

• Moderate to severe levels of depression and anxiety were evident pre-group in some studies

-

• Statistical analysis of repeat measures was generally used to determine effect

-

• Only one measure, the MI-Scale, was specifically designed and validated for use with HS populations

-

• Little significant overall change occurred for positive symptoms

-

• Significance was achieved on some measure subscales relating to negative symptoms

-

• Potential significance (type 1 error withstanding) was observed on some depression and esteem measures.

-

• Potential iatrogenic effects were evident in three of the five studies.

Table 2. An interpretation of the identified group studies

Appraisal

Group CBTp interventions were largely based on non-forensic derived protocols with approach fidelity ensured through supervision and guidance from senior staff and manual authors. Little significant change was reported for positive symptom experiences. Outcome congruence and study rigour make this difficult to attribute to poor assessment design or context application. Similar effects were observed between scales with a high-degree of acceptability in HS contexts such as the MI-Scale (Brand, Diks, Vanemmerik and Raes, Reference Brand, Diks, Vanemmerik and Raes1998) and CORE-OM (Perry, Barkham and Evans, Reference Perry, Barkham and Evans2013), and measures not validated for HS. The potential for psychometric assessments not to capture therapeutic change also seems doubtful given the congruency achieved between quantitative and qualitative data in the Vallentine et al. (Reference Vallentine, Tapp, Dudley, Wilson and Moore2010) study.

Pre-group sample characteristics may offer the most viable explanation for limited effect. Across all studies pre-group outcomes were generally indicative of stability, symptom remission, and normal esteem affording the probability of only minor change (Laithwaite et al., Reference Laithwaite, Gumley, Benn, Scott, Downey and Black2007). HS Group CBTp studies failed to replicate the substantial effects achieved in similar protocol-based non-forensic studies where participants reported more severe pre-intervention symptom profiles (Hall and Tarrier, Reference Hall and Tarrier2003). Indeed, HS non-participation was highest amongst those patient groups who were least likely to have experienced symptom remission, typically those with shorter (less than 2 years) and longer (9 years +) lengths of stay (Garrett and Lerman, Reference Garrett and Lerman2007; Nijman et al., Reference Nijman, De Kruyk and Van Nieuwenhuizen2004). This may suggest that non-forensic patients with unremitted symptoms are more likely than their forensic counterparts to engage in and gain from group CBTp. Paradoxically, HS patients who are most likely to engage in group CBTp seem the least likely to need the intervention in order to meet symptom and adherence related conditions for discharge. One might therefore question the efficacy and ethicality of intensive global and specific CBTp group programmes targeted at remitted post-admission or pre-discharge HS patients, given the reported iatrogenic effects.

However, significant lasting changes in outcome measure subscales linked to negative symptom experiences did occur. Symptom experiences often deemed untreatable, such as affective flattening, alogia and anhedonia, significantly improved, as did social skills and linked aspects of self-esteem. Significant reductions in negative coping were also seen. Commendably, these changes were generally observed in trials with control groups. Aggregate means analysis (Field, Reference Field2000), high levels of co-morbid personality disorder (Hornsveld and Nijman, Reference Hornsveld and Nijman2005) and medication-linked reduced social functioning (Vallentine et al., Reference Vallentine, Tapp, Dudley, Wilson and Moore2010) may also have masked further large individual improvements. Indices of change and qualitative data within the Vallentine et al. study also indicated that transient iatrogenic effects might be indicative of and important components within acceptance, insight development and positive change.

Conversely, results might also have been less significant than reported. Despite often amalgamating data from several cohorts over a number of years, subject numbers remained less than ideal for statistical analysis. Results were deemed preliminary (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Ferrito and Tapp2014). Corrections for multiple measures and comparisons were also absent and gender homogeneity precluded generalizability. As opposed to CBTp per se, observed effects might also have been due to group inclusion and enhanced opportunities to safely test and practise social skills. However, the inclusion of family members in the Hornsveld and Nijman (Reference Hornsveld and Nijman2005) study and the extended group duration in Laithwaite et al. (Reference Laithwaite, O'Hanlon, Collins, Doyle, Abraham and Porter2009) to offer increased skills rehearsal, failed to produce unequivocal differences.

Box 2. Therapeutic milieu inferences

-

• Training nursing staff is a viable means of developing CBTp linked ward milieus within rehabilitation and medium dependency HS contexts

-

• Investing in HS nursing staff to facilitate CBTp linked milieus is a cost effective means of implementing NICE guidance, meeting national nursing competency criteria and increasing the clinical efficacy of nursing interventions

-

• CBAp training can be delivered by suitably qualified nurse trainers

-

• CBAp and the maintenance of CBTp linked milieus can be effectively supervised via suitably qualified nurse therapists

-

• When offered by registered nurses, CBAp facilitates a number of clinical, nursing and organisational benefits

-

• CBTp linked ward milieus aid in the reduction of high impact high severity assaults and aid the efficacy of pharmacological interventions

-

• CRT in combination with a CBTp linked ward milieu can also reduce low impact low severity assaults and address deficits associated with dysexecutive syndrome

-

• Patients exposed to CBAp report a number of clinical benefits

-

• Evidence of impact remains anecdotal and derived from a limited number of cases (n=1 and n=5 respectively) - no statistical analysis of significance was reported

-

• The data is based on male patients only.

Therapeutic milieu

Interpretation

Two of the identified studies related to the development of modality specific ward milieus involving CBTp (Cooper, Reference Cooper2009; Savage, Reference Savage2009). Savage (Reference Savage2009) described a rehabilitation unit at Ashworth Hospital that combined a psychosocial interventions (PSI) milieu (Savage and McKeown, Reference Savage and McKeown1997) and individualized Cognitive Rehabilitation Therapy programmes – CRT (Rogers, Reference Rogers2006) to aid readiness for discharge. Cooper (Reference Cooper2009, Reference Cooper2010) developed and evaluated the impact of a modularized ward based Cognitive Behavioural Approaches for Psychosis (CBAp) training programme (Turkington et al., Reference Turkington, Kingdon, Rathod, Hammond, Pelton and Mehta2006) designed to aid individual nursing interventions and create a modality specific milieu on one of Ashworth Hospital's medium dependency wards. An interpretation of these studies with regard to method, patient group, mode of delivery and main results is offered in Table 3. Subsequent inferences are shown in Box 2.

Table 3. An interpretation of the studies relating to therapeutic milieus

Appraisal

The anecdotal evidence these studies report gives the impression that CBTp ward milieus are less intensive, less costly and possibly more effective than group CBTp at helping HS patients progress and rehabilitate. Patients reported better coping, engagement, insight and goal attainment. High impact, high severity assaults reduced and positive symptom experiences further remitted. Additional benefits included staff enhancement, the attainment of national nursing competency standards and compliance with core NICE guidance. Comparative costs of the mainly nurse developed and supervised ward milieus were also reported as comparatively lower (Cooper, Reference Cooper2010). Supplementation with therapist delivered one-to-one social problem solving, pro-social behaviour development and over-learning led to important dysexecutive syndrome deficit reductions correlated to the significant negative symptom changes reported by group trials. Ironically, significant change in groups may have resulted from a similar practice of supplementing group sessions with individual sessions and not the groups per se. However, these anecdotal insights cannot be asserted with any certainty, or generalized, particularly in relation to the more rigorous evidence generated by the group studies. Training nurses in ward contexts also proved problematic, wider management support was low and levels of patient satisfaction equivocal. Further application and more rigorous investigation are warranted.

Individual CBTp

Interpretation

A number of studies relating to individual CBTp in HS were identified. In a single case study analysis, Bentall and Haddock (Reference Bentall, Haddock, Mercer, Mason, McKeown and McCann2000) evaluated the impact on HS patients of a time-limited community CBTp treatment protocol for auditory hallucinations. Benn (Reference Benn, Kingdon and Turkington2002) reported on the impact of using more idiosyncratic interventions with adherent male subjects, an approach Rogers and Curran (Reference Rogers, Curran, Grant, Mills, Mulhern and Short2004) replicated in their study. Cawthorne (2004) used a within subjects analysis of difference to determine the impact on chronic adherent HS patients of an adapted positive symptom focused CBTp protocol. Ewers, Leadley and Kinderman (Reference Ewers, Leadley, Kinderman, Mercer, Mason, McKeown and McCann2000) and Slater (Reference Slater2011) used purposive sampling to target less adherent, more typical HS patients in their case analyses, whilst Garrett and Lerman (Reference Garrett and Lerman2007) explored the impact of individual time-limited interventions on chronic long-term patients. An interpretation of these studies with regard to method, patient group, mode of delivery and main results is offered in Table 4. Subsequent inferences are shown in Box 3.

Box 3. Individual CBTp inferences

-

• Fixed, symptom specific nomothetic protocols that lack the level of flexibility to incorporate context and index offence related factors risk treatment failure within HS

-

• Collaborative flexible idiosyncratic conceptualization and intervention incorporating risk and context related factors can successfully target and reduce specific positive symptom experiences and risk in adherent HS patients

-

• Nomothetic nurse-therapist delivered protocols that are sensitive to HS patient specificity have a marked impact within 20 sessions on delusions and hallucinations with adherent patients.

-

• Supervised by experienced therapists, practitioner delivered 20-session CBTp interventions can revitalize progress in severely chronic long-stay patients

-

• Although the majority of studies referenced a greater need to invest in longer and more flexible therapeutic relationship development, specifics were seldom offered.

-

• Non-adherence in HS patients is typical.

-

• Chief-complaint orientated CBTp results in symptom specific and global improvements for non-adherent HS patients when delivered by accredited therapists. Protracted therapy periods (50+ sessions) are necessary

-

• Transient iatrogenic effects (depression, guilt, anxiety, worthlessness) linked to the change process are reported in the majority of studies

-

• Mean aggregate scores detected comparatively little variance in depression or anxiety during therapy.

-

• Triangulated case study analysis is the most used method for evaluating individual CBTp in HS.

-

• A statistical analysis of significance was only offered in one study.

-

• The number of patients evaluated remains limited.

-

• Very few studies offered fidelity data linking their interventions to a specific approach.

Table 4. An interpretation of the studies relating to individual CBTp

Appraisal

Reported efficacy for individual therapy was better than for groups and ward milieus. Study data suggested that HS patients who engaged in individual CBTp experienced active symptom profiles in excess of the norms expected for the diagnostic category. This may support population specificity arguments and help explain the greater level of efficacy of individual therapy (Nijman et al., Reference Nijman, De Kruyk and Van Nieuwenhuizen2004). The data indicated that whilst patient behaviour may stabilize during the initial period of admission (Nijman et al., Reference Nijman, De Kruyk and Van Nieuwenhuizen2004), this may not correlate with symptom remission. Attempts to introduce nomothetic non-forensic derived protocols for individual CBTp resulted in treatment failure (Bentall and Haddock, Reference Bentall, Haddock, Mercer, Mason, McKeown and McCann2000). Several studies suggested that flexibility in combination with sensitive contextual and idiosyncratic adaptations could substantially enhance efficacy with adherent HS patients (Benn, Reference Benn, Kingdon and Turkington2002; Rogers and Curran, Reference Rogers, Curran, Grant, Mills, Mulhern and Short2004). However, additional adaptation encompassing an initial phase of chief-complaint rather than symptom orientated therapy seemed to successfully engage more typical non-adherent HS patients (Ewers et al., Reference Ewers, Leadley, Kinderman, Mercer, Mason, McKeown and McCann2000; Slater, Reference Slater2011), further emphasizing specificity. In their studies Ewers et al. (Reference Ewers, Leadley, Kinderman, Mercer, Mason, McKeown and McCann2000) and Slater (Reference Slater2011) were able to demonstrate that specificity barriers within HS populations could be effectively addressed by first focusing therapy on a co-established non-symptom-based chief complaint. This context specific mode of individual CBTp seemed to offer a gateway to and platform for later symptom-based interventions and to substantially increase the likelihood of engagement and subsequent recovery amongst typical HS patients.

These engagement based adaptations resulted in protracted therapy periods in excess of the minimum requirement of 16 for non-HS populations (NICE, 2014). Individual interventions targeting global symptom experiences needed fewer sessions than for similar global group interventions (50-54 for individual, compared to 70+ for groups). As with the groups, symptom specific individual therapy required fewer sessions, a comparable number to the groups. For adherent HS patients it was also possible to develop and usefully apply symptom specific protocols. Important gains for severely chronic long-stay HS patients, which other treatments had failed to progress, were also reported. In this instance therapy was protocol based (developed within context) and delivered by practitioners trained and supported by experienced therapists. Offering individual CBTp earlier might therefore reduce lengths of stay as well as the high costs associated with long-stay HS patients. The majority of one-to-one CBTp studies were nurse led; although it is important to recognize the multi-disciplinary development of specificity adaptations reflected within the studies, the potential financial implications regarding delivery may warrant deeper investigation.

In contrast to the group trials, a higher level of transient iatrogenic effects resulted from individual therapy. Whilst this might offer cause for concern, the rich description the case analyses contain supports the Vallentine et al. (Reference Vallentine, Tapp, Dudley, Wilson and Moore2010) assertion that these effects may be associated with and indicative of change. The contrast in efficacy between group and individual HS CBTp is commensurate with this theory. However, levels of reported individual CBTp efficacy are largely from case analysis, which differs from the more controlled group evaluations. A more rigorous evaluation of individual HS CBTp is warranted in order to facilitate more accurate comparisons.

Synthesis and comparison

This review establishes the rich diversity of CBTp service provision developed internationally within HS establishments. In the UK, the NHS Commissioning Board stipulates that patients should have equal access to consistent and effective services regardless of location (NHS Commissioning Board, 2012). There is a need to consolidate and harmonize effective CBTp practices across HS sites. Synthesized from the source analysis and developed in association with the UK High Secure Hospitals CBTp Collaboration Group, an algorithm for effective evidence-based cross-site HS CBTp is tentatively offered in Figure 2.

Figure 2. An algorithm for effective evidence-based HS CBTp

Although the HS studies in this review were not considered by NICE in developing its most recent guidance (NICE, 2014), the derived algorithm compares favourably. Both support application across all presentations, they support the efficacy of individual CBTp over group, and the importance of supervision and protocols to ensure fidelity and the efficacy of delivery by a variety of professions. However, there are also some crucial differences. The HS algorithm emphasizes the need for context specific protocols that include greater flexibility, extended therapy periods and sensitivity towards offence related factors. Chief complaint orientation prior to symptom specific interventions is included as a means of managing adherence related difficulties and the potential for transient distress linked to change is acknowledged. The efficacy of group interventions to target hard-to-treat negative symptoms within HS contexts is also recognized, as is the potential for ward milieus and CBAp trained link nurses to further enhance and progress gains.

Conclusions

A pragmatic iterative search strategy and hermeneutic source analysis have been used to access a wider body of HS CBTp studies than has previously been considered, one that has included fugitive literature. Although novel and limited, the inclusion of fugitive source materials offers a means of informing discussion within the field and uncovering important perspectives that might otherwise be lost (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, Reference Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic2010). The mode of analysis also facilitated greater transparency with regard to analyst primary interpretations, inferences and subsequent appraisals than may be typical. This exploratory review indicates that CBTp is an active component of treatment in HS contexts in the UK and internationally. A synthesis of the more efficacious practices has been offered in the form of an interventions algorithm, a multi-site controlled trial may afford a more robust and rigorous analysis with which to inform wider guidance. Whilst there were similarities between HS and non-HS CBTp provision, the algorithm and review literature highlight key necessary differences. Continued application and evaluation of HS CBTp interventions are warranted.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the important contribution of members of the UK HS Hospitals CBTp Collaboration Group in making this review possible.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.