Our planet is on fire. The Amazon, Australia, and California, to name but a few places, have been changed indelibly. “The hour is late, and the moment of consequence, so long delayed, is now upon us,” write Christiana Figueres and Tom Rivett-Carnac, two of the main actors in the creation of the landmark 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, warning of the environmental crisis upon us. “Do we watch the world burn, or do we choose to do what is necessary to achieve a different future?” they ask.Footnote 2 Environmental degradation compromises the agendas for peace and security, human rights, and development at the United Nations. And while the UN has moved the environmental needle in terms of information, institutions, and awareness, many environmental problems persist, some are getting worse, and new crises are emerging. The UN response is simultaneously critical and inadequate for the resolution of these contemporary interconnected global problems.

We are still—as journalist Wade Rowland wrote in 1973, after the creation of the first international environmental institution, the UN Environment Programme (UNEP)—“fighting fire with a thermometer.”Footnote 3 The environmental institutions of today's world—UNEP and the numerous multilateral environmental agreements—detect emerging issues and alert the world community to impending crises but rarely have the capacity to resolve them directly. This essay examines the institutional system within the UN for global environmental protection and analyzes its major achievement—the reversal of ozone layer depletion—and the current existential climate change crisis.

Environment in the United Nations

Though the UN was founded seventy-five years ago, environmental issues only became a substantive part of the UN agenda starting in the 1970s, when the profound transformation and vulnerability of the planet became apparent. The “Earthrise” photo that astronauts transmitted on December 24, 1968, from Apollo 8—the first manned mission to orbit the moon—altered public awareness. “The vast loneliness is awe-inspiring and it makes you realize just what you have back there on Earth,” the astronauts broadcast.Footnote 4 Our planet was clearly a single shared system and scientific consensus was emerging that humans could damage the entire biosphere, that resources were limited, and that collective action was imperative.

International efforts to protect species through environmental agreements date back to the 1900s, when countries sought to protect migratory birds, fur seals, and other wild animals, birds, and fish. Agreements were usually bilateral rather than multilateral, as they concerned resources across the boundaries of two states. With the creation of the UN in 1945, nation-states negotiated broader legal agreements on whaling, marine fisheries, and marine pollution from oil. By the late 1960s, governments had negotiated conventions on the conservation of specific species and ecosystems. The institutionalization of an environmental agenda at the UN, however, came only with the first UN Conference on the Human Environment in 1972, the Stockholm Conference. The Stockholm Declaration on the Human Environment provided the foundation for the development of what would become international environmental law. Principle 21 affirmed states’ “sovereign right to exploit their own resources pursuant to their own environmental policies, and the responsibility to ensure that activities within their jurisdiction or control do not cause damage to the environment of other States or of areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction,” which the International Court of Justice recognizes as international law. Governments also created UNEP as the “anchor institution” for the global environment, and set in motion the creation of new international legal agreements to address environmental problems.

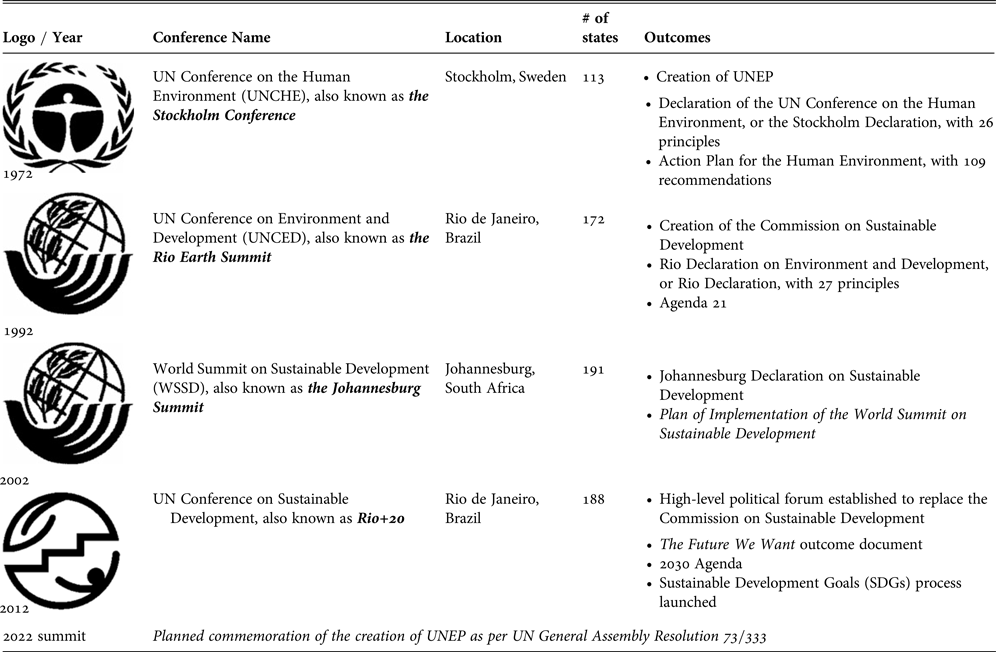

Global environmental governance developed through phases marked by global environmental summits that convened at anniversary moments (see Table 1). During the period between the Stockholm Conference in 1972 and the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, environmental agreements proliferated and UNEP developed robust environmental portfolios. In 1987, The World Commission on Environment and Development, chaired by then-prime minister of Norway, Gro Harlem Brundtland, produced the report Our Common Future, defining sustainable development as development that meets current human needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.Footnote 5 In 1992, the Rio Earth Summit catalyzed a wave of new norms, policies, and institutions; established sustainable development as a new global paradigm; and created consensus around the need to resolve a range of environmental issues through international legal instruments. The conventions on climate change, biodiversity, and desertification that governments signed at the summit came to be known as the Rio Conventions.

Table 1. Fifty Years of Environmental Summits

Over the next twenty years, until the UN Conference on Sustainable Development, or Rio+20, in 2012, there was further proliferation of agreements, rising concerns about institutional fragmentation, and calls for structural reform through the creation of a World Environment Organization.Footnote 6 The Rio+20 conference provided a platform for launching new global goals—what later became the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015—and for reforming the UN environmental and sustainable development institutions. The environment has thus moved from an issue absent on the original UN agenda to a concern critical to all of its core operations—peace and security, development, and human rights. The collection of UN institutional arrangements for the environment, however, continues to assess the state of affairs and, despite some notable successes, remains largely inadequate, incoherent, and ineffective in addressing the global problems it was designed to resolve.

An Anchor Institution for the Global Environment: The United Nations Environment Programme

Although it is taken for granted today that it is the main global international environmental institution, UNEP was created against the odds. Even convening a successful international conference on the environment was unlikely when the idea first came up in 1967.Footnote 7 The UN had only recently expanded its membership as many former colonies gained independence and, additionally, was subject to Cold War tensions among member states. Hence, the notion of environmental protection evoked a range of conflicting reactions among countries, with most finding some reason to be skeptical or even hostile to an environmental protection agenda. In much of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, environmental problems were not the side effects of excessive industrialization but more often a symptom of inadequate development, and rapid economic growth remained the highest priority. Environmental protection, therefore, symbolized protectionism, conditionality, and an obstacle to development. Soviet bloc countries saw in these efforts a capitalist attempt to stunt economic and political progress in the race for military dominance and ideological supremacy. Many developed countries saw the efforts as representing a potential tool for developing countries to pressure them for greater financial resource transfers. Most countries, therefore, were highly suspicious of the environmental agenda and the creation of a collective, comprehensive, and ambitious vision for the environment thus seemed highly unlikely.

Nevertheless, in this context, governments created an international institution with an ambitious normative mission. UNEP was set up to promote collaboration by carrying out scientific assessments of the state of the environment, to provide information about existing and emerging environmental problems, and to stimulate action and promote partnership among UN agencies and member states. It was therefore designed not to be a firefighter itself but to measure the heat of the flames, and to envision and craft a program and let others carry it out. Importantly, after heated debates that illustrated existing political tensions, governments made the decision to locate the headquarters of UNEP in Nairobi, Kenya—the first, and still the only, UN headquarters city in the developing world. Designed to be a nimble, fast, and flexible entity at the core of the UN system, UNEP was envisioned as the center of gravity for environmental affairs.Footnote 8 Fifty years after its creation, however, UNEP remains unknown to many and is often misunderstood.

Without a systematic analysis of the history of global environmental governance, a mythology has been perpetuated about UNEP. According to common lore, the organization was created to be deficient by design because powerful states opposed the establishment of a strong international environmental organization; its institutional form as a subsidiary body, a program rather than a specialized agency, was a means of weakening it through voluntary financial resources; its mandate was impossible and hopeless; and it was located in Nairobi as a strategic necessity to appease developing countries and/or as a way to marginalize it.Footnote 9 A closer look at the historical events in the 1970s, however, shows that UNEP was not purposefully established as a “weak, underfunded, overloaded, and remote organization”Footnote 10 but rather was established as the “anchor institution” for the global environment.Footnote 11

Creating a Body of International Environmental Law

The development of international environmental law has been one of UNEP's and, indeed, the UN's landmark successes. Global environmental conventions are the main legal instruments for promoting collective action toward solving global environmental problems and staying within a safe planetary operating space.Footnote 12 The UN has observed and measured environmental problems such as ozone layer depletion, biodiversity loss, persistent organic pollutants, and climate change. In doing so, it has raised awareness of the planetary dimension of environmental challenges, and developed plans of action. The conventions on ozone layer protection, regulation of chemicals and hazardous waste, climate change, desertification, and biodiversity were all created and concluded with UNEP's engagement.

Indeed, during the first decade of UNEP's operations, almost as many international agreements were created as during the previous sixty years.Footnote 13 Although many scholars point to the existence of hundreds of international environmental agreements, only thirteen are of a truly global character, addressing issues of global scope and with close-to-universal membership. UNEP has been the main actor behind the creation of these global agreements.

By the early 1990s, governments had adopted a pattern of creating agreements for specific issues, often with their own secretariats, monitoring and reporting mechanisms, and financial support, leading to what one scholar called “treaty congestion.”Footnote 14 The agreements increasingly made provisions for possible changes in scientific understanding of environmental problems, for technical assessments, for adding annexes, for scientific advisory bodies, and for regular meetings of the parties.Footnote 15 The obligations became increasingly specific and intrusive on states’ sovereignty. The successful creation of a robust body of international environmental law has led to some challenges. The result is increased demands on member states’ time, attention, and resources, as well as serious competition among international organizations. Implementation of the complex and growing body of international environmental law has been and remains a significant challenge, particularly since it does not provide serious support to countries with limited capacity to implement provisions. The consequence is that most agreements have remained aspirations.

Successful Problem Resolution and Persistent Challenge: Ozone Depletion and Climate Change

The most successful global environmental agreement is the 1985 Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer, complemented by the 1987 Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer and five subsequent amendments to that protocol. Their implementation has led to the reversal of the depletion of the ozone layer. These agreements are UNEP's and, indeed, the UN's greatest achievement on the environment, as they have helped to resolve one of the most prominent global environmental problems.

The ozone depletion problem came onto the international political agenda in the mid-1970s when Mario Molina and Sherwood Rowland articulated a hypothesis that CFCs (chlorofluorocarbons)—a group of synthetic chemicals used widely in aerosols, coolants, and refrigerators—were destroying the stratospheric ozone layer. At the request of the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), a major environmental nongovernmental organization in the United States, UNEP took the lead on the issue of ozone depletion and received approval from its governing council to launch an investigation and international discussions. In essence, UNEP's effective use of science, policy, and support functions became a model for effective multilateral action in complex international negotiations to address global problems.Footnote 16

UNEP was instrumental in creating public awareness about the causes and consequences of ozone depletion and catalyzed consensus on potential implementation strategies. Executive Director Dr. Mostafa Tolba worked with governments to devise the legal regime, which he considered critical to human survival.Footnote 17 Tolba “pleaded, provoked, cajoled, shamed, and sometimes bullied reluctant governments ever closer to the treaty provisions that he, as a scientist, knew were necessary for the world,” wrote Ambassador Richard Benedick, the chief U.S. negotiator for the Montreal Protocol. “It was an unforgettable virtuoso performance, a role that he undertook with unflagging energy and with absolutely no consideration for his own personal popularity.”Footnote 18 The institutional mechanisms of the Montreal Protocol—differentiated goals and time frames for industrialized and developing countries, economic incentives for participation and compliance, a financial mechanism to support implementation, technology transfer provisions, and assessment procedures to allow readjustment—enabled consistent compliance and implementation of international obligations. Indefatigable individual and institutional leadership were critical to averting a global environmental crisis. Importantly, scientific evidence is now sufficient to show that “the Montreal Protocol is working.”Footnote 19

While resolving the global ozone depletion problem has been relatively successful, tackling climate change requires decarbonization of the economy and, thus, a societal transformation. Addressing climate change and meeting obligations under existing climate treaties remains a significant challenge. The 2015 Paris Climate Agreement is the culmination of a progression of negotiations that began in the 1970s with a series of UN conferences bringing together scientists, governments, and UN organizations. UNEP and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) were instrumental and highly influential in the process. In 1988, they established the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to provide policymakers with regular assessments of the scientific basis of climate change, its impacts and future risks, and response strategies for mitigation and adaptation. In 1992, at the Rio Earth Summit, governments adopted the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), modeled after the 1985 Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer. Since 1995, when the first Conference of the Parties (COP) of the UNFCCC met in Berlin, governments have been assembling annually in an effort to coordinate action to abate climate change.

Three milestones stand out in the subsequent twenty-year history of the international climate regime. In 1997, at COP 3, governments agreed to the Kyoto Protocol, which set emission reduction targets only for developed countries since they were historically the largest emitters. COP 15, held in Copenhagen in 2009, was considered the low point in efforts to find agreement, as the final outcome, the Copenhagen accord, fell far short of expectations and did not include any commitments to emissions reductions. Six years later, in 2015, at COP 21 held in Paris, 196 parties to the convention (195 states and the European Union) unanimously adopted the Paris Agreement, which articulated ambitious long-term goals and a renewed global commitment to address the threat of climate change and would be applicable to all parties and comprehensive in scope.

The Paris Agreement was hailed as a monumental achievement and a “game changer”Footnote 20 because it was successful on all core criteria outlined by scholars, researchers, and the United Nations secretary-general: universal participation, significant emission reduction commitments, transparency and accountability, finance, and high compliance rates.Footnote 21 It possesses a binding yet flexible legal nature, clear procedures for accountability, and a credible financial structure. As of early 2020, 187 of the 195 signatories to the convention had ratified it.Footnote 22 Since 2015, the parties have sought to create the mechanisms and “rulebook” to ensure that countries limit greenhouse gas emissions and keep global temperature rise within 1.5 degrees. According to a special 2018 report of the IPCC, however, time to mobilize action is running out.Footnote 23 Mounting disagreements threaten implementation as the tensions between environment and development and between developing and developed states persist. Suspicion and reticence to act first are the most significant roadblocks to implementation.

Yet, the Paris Agreement has also been successful in setting a new binding global standard that national courts have started to utilize. In February 2020, for example, a U.K. court of appeals ruled that plans for building a third runway at London's Heathrow airport were illegal on the grounds that they were not consistent with the government's commitments under the Paris Agreement.Footnote 24 Importantly, the government will not appeal the ruling, affirming the power of international law to frame national policy.

Conclusion

Since the establishment of its first international environmental institution, the UN has drawn public and political attention to key environmental problems, developed a robust body of international environmental law, framed constructive policy options, and catalyzed needed action. Even though coordinating the numerous environmental activities across the UN system remains a challenge, and assistance to national environmental efforts is not yet consistent or reliable, the UN has been a powerful platform, actor, and force in global environmental governance. The biggest obstacles have been the lack of a common vision, consistent priorities, and steady support for action, but the importance of global legal agreements cannot be overstated. The contemporary climate crisis has challenged the status quo and national institutions are turning to international law for guidance, as the Heathrow airport case illustrates.

In 2018, Greta Thunberg, a fifteen-year-old girl from Sweden, launched a global climate school strike, motivating young people around the world to demand greater action from their governments and from the United Nations. Thunberg's impassioned demands for action resonated around the world. “Adults keep saying: ‘We owe it to the young people to give them hope,’” she stated to global leaders at the 2019 World Economic Forum. “But I don't want your hope. I don't want you to be hopeful. I want you to panic. I want you to feel the fear I feel every day. And then I want you to act. I want you to act as you would in a crisis. I want you to act as if our house is on fire. Because it is.”Footnote 25 When it fully embraces its mission as the anchor institution for the global environment, UNEP could become the orchestrator of firefighters across scales and geographies, and stimulate effective collective action to resolve global environmental crises.