Introduction

Even though scholars continuously debate whether populism is a discourse, strategy or ideology, they agree that it primarily creates a dichotomy between the elites and the people (Mudde Reference Mudde2004; Stanley Reference Stanley2008; Pappas Reference Pappas2014). The people and the elites are in an antagonistic relationship: they constantly fight and cannot participate in representative politics together (Taggart Reference Taggart, Meny and Surel2002). Furthermore, populism is based on a premise that ‘politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people’ rather than of the corrupt elite (Mudde Reference Mudde2004, 543). That implies the people’s direct participation in the decision-making process. Institutional structures, bureaucracy, regulations and restrictions of the political process, mediating actors and representative politics in general are considered obstacles for the people’s governance and therefore objectionable (Arditi Reference Arditi2007; Taggart Reference Taggart, Meny and Surel2002; Canovan Reference Canovan1999). At the same time, populists claim to represent the silent majority, which is neglected by the corrupt and privileged elite. This contradiction between the rejection of representation on the one hand, and aspirations of better representation on the other hand is examined in theoretical works. However, there are few studies that look specifically at the discourse of populists on representation, and my article aims to fill this gap.

Populism is inseparable from its context. Manifestations of populism in Central and Eastern Europe are diverse, but expressions of discontent with the representative system are a frequent feature. Anti-establishment populist parties (Učeň Reference Učeň2007), unorthodox, new or centrist populist parties (Pop-Eleches Reference Pop-Eleches2010) and anti-party reform parties (Hanley and Sikk Reference Hanley and Sikk2016) have been constantly challenging party systems in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). Widespread use of anti-establishment discourse of challenger parties is often confused with populism, even though not all of them refer to the people as homogeneous (van Kessel Reference Van Kessel2015). While the radical right populism is relatively weak in CEE, centrist populism has emerged instead (Stanley Reference Stanley, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017). Shafir (Reference Shafir, Gherghina, Mişcoiu and Soare2013) distinguishes populism in CEE from anti-systemic radical right parties and calls it ‘neopopulism’. Populism in the region has to take into account the previous regime (Heinisch et al. Reference Heinisch, Holtz-Bacha and Mazzoleni2017) and the transition period, which appears to have been highly beneficial for the former nomenclature (Shafir Reference Shafir, Gherghina, Mişcoiu and Soare2013). At the same time, populists cannot openly criticize liberalism and democracy as their counterparts in Western Europe can (Gherghina et al. Reference Gherghina, Mişcoiu, Soare, Heinisch, Holtz-Bacha and Mazzoleni2017). Populist actors gain strength in the region because voters have become dissatisfied with the traditional political parties before the party systems have been fully institutionalized (Kriesi Reference Kriesi2014). It should be noted that this article primarily focuses on populism, but not the ideologies populism attaches itself to.

Lithuania is a particularly interesting case in terms of the relationship between populism and representative democracy. It is a former Soviet Union country where the communist legacy still has residual effects on the political space. On the other hand, the Baltic States are the only stable and free democracies of the former Soviet Union in which the conditions for the emergence of populism (pluralism and democracy) are good (March Reference March, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017). Populist politicians are in a good position to question the necessity of political parties in a country with low political participation, an unstable party system, and very low confidence in political institutions (especially in political parties) (Vilmorus Reference Vilmorus2020).

To examine the contradiction between the aspiration for the unmediated link between the government and the people and the necessary distance between the two in representative politics I analyse the discourse of populist actors on political representation. The article aims to answer the following research question: how do populist parties define political representation? I argue that to understand the populist conception of representation we need to analyse how populist parties interpret and define (1) who are to be represented and what their interests are; (2) who are to do representing. Interpretative empirical study reveals how Lithuanian populist political parties define political representation. Research data consist of party election manifestos of 2016 and articles on populist parties’ websites (period of April 2016–September 2017).

The article contains three main sections. In the next section, I review the literature on populist discourse regarding representation and construct a theoretical framework to analyse it. The section after presents the selected political parties as well as data and methods. Finally, I present the results of my empirical interpretive study on how populist parties describe the represented, their interests and the representatives.

Populism between Immediacy and Representation

While populism is ‘thin-centred’, it attaches itself to political actors of various ideologies (Mudde and Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2018) and its manifestations are very diverse. Populism is highly dependent on the context, on the relevant grievances (Mudde and Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2013; Gherghina et al. Reference Gherghina, Mişcoiu and Soare2013), and on the particular (economic, sovereignty, security) crises in the country (Gagnon et al Reference Gagnon, Beausoleil, Son, Arguelles, Chalaye and Johnston2018). European populism is a rather recent phenomenon primarily characterized by radical right-wing politics. This exclusive politics is based on identity rather than on economic dimension. The long-lasting tradition of populism in Latin America is inclusionary and primarily concerned with the issues of economic redistribution, inclusion and empowerment of the poor (Mudde and Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2013). Central European populists can be described as neopopulists because they are systemic political actors who claim that just some capitalists are corrupt while others protect genuine democracy and fight corruption. While neopopulists do not formulate any specific ideological provisions, they are able to form coalitions with both radical right and left (Shafir Reference Shafir, Gherghina, Mişcoiu and Soare2013).

Populist parties relate to the specific national background to define the ineligible representatives, the represented and themselves as representatives. ‘Elite’ is, in general, described as a separate political ‘caste’ (Ivaldi et al. Reference Ivaldi, Lanzone and Woods2017) or political class (Negrea-Busuioc Reference Negrea-Busuioc2016). While the Front National, the Northern League, Podemos and Five Star Movement define the elite as global oligarchs and capitalists (Ivaldi et al. Reference Ivaldi, Lanzone and Woods2017), the elite in the USA is not necessarily defined in terms of wealth (Wodak Reference Wodak2017). At the same time, some French and German intellectuals get involved in the activities of populist parties and are not considered the enemy of the people (Wodak Reference Wodak2017). Moreover, the image of the elite also shifts over time. In Sweden, Finland and the Netherlands, the populist parties began by confronting the national political elite and only later focused on the enemy on the left or abroad (Kriesi and Pappas Reference Kriesi and Pappas2015). The people are defined as a subject which consolidates different social groups (Ivaldi et al. Reference Ivaldi, Lanzone and Woods2017). For example, populist parties in Romania use plural pronouns such as ‘we’ and ‘our’ to underline that they represent the people (Negrea-Busuioc Reference Negrea-Busuioc2016). However, the discourse of populist political parties differs according to the action limits of the people. In the discourse of Syriza the people are described as active agents that can engage in public affairs. The party presents itself as able to identify and recognize various constituencies, which comprise ‘the people’, and to represent them (Stavrakakis and Siomos Reference Stavrakakis and Siomos2016). Similarly, other parties emphasize tools of direct democracy and suggest citizens’ engagement in addition to better representation (Kriesi and Pappas Reference Kriesi and Pappas2015). However, in the discourse of Viktor Orban, elections simply grant him the authority to govern in accordance with the common will of the people (Körösényi Reference Körösényi2019). Similarly, Venezuelan society is defined as thinking unanimously and having a common will which can be embodied by a leader (de la Torre Reference De la Torre2016).

Political theorists have been discussing the relationship between populism and representative democracy for a while now. One group of scholars – Pasquino (Reference Pasquino, Albertazzi and McDonnell2007) and Urbinati (Reference Urbinati1998, Reference Urbinati2014) – claims that populism always poses a definite threat to democracy. Meanwhile, Canovan (Reference Canovan1999, Reference Canovan, Mény and Surel2002, Reference Canovan2004), Taggart (Reference Taggart2000, Reference Taggart, Meny and Surel2002, Reference Taggart2004) and Arditi (Reference Arditi2003, Reference Arditi2004, Reference Arditi2007) argue that populism has the potential to correct democracy. The debate on the relationship between populism and democracy is about the conception of democracy, not about a specific manifestation of populism. Therefore, I argue that understanding populist conception of representation could provide new insights into this debate.

To understand populist conception of representation, I analyse the discourse of the Lithuanian populist political parties. Before starting an empirical analysis, I define what representation is so that I can reveal a certain manifestation of it. For this, I turn primarily to the writings of Hanna F. Pitkin. The recent volume on political representation Reclaiming Representation: Contemporary Advances in the Theory of Political Representation (Vieira Reference Vieira2017) has once again stressed the importance of her insights. Pitkin has provided the best-known definition of substantive representation ‘acting in the interest of the represented, in a manner responsive to them’ (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1972, 209). According to this definition, it seems that representatives simply need to find out the interests of the represented and act accordingly. Substantive representation is usually assessed by the measures of ideological congruence between the represented and the representatives in empirical research (Powell Reference Powell2004). However, the theoretical definition is not as straightforward as it is often assumed to be in empirical studies, primarily because political representation is not a principal–agent relationship, but a relationship between the representative(s) and their constituency (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1972). It is therefore necessary to clarify what the representatives and the represented are.

First, Pitkin defines representatives almost exclusively as individual actors, and, as it is noted by Thomassen (Reference Thomassen1994), almost completely ignores the existence of political parties. Although she does mention political parties, she defines representation above all as the relationship between the constituency and the individual representative. Representatives must consider political parties as an additional factor (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1972). According to her, collective representation is possible, but it is not a necessary condition of political representation.

Second, a constituency is a collective that may or may not have shared and articulated interests. Voters usually do not form an organized group and it is not clear whether they even can have a common interest in which representatives should act. Residents of an electoral district will have common interests that are specific to a particular territory (such as infrastructure projects) and may even defend these specific interests in an organized way. However, most of people’s interests are not related to a specific district and thus differ. Therefore, it can be accepted that the representative ‘acts for a group of people without a single interest, most of whom seem incapable of forming an explicit will on political questions’ (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1972).

How is representation possible when citizens do not articulate common interests? Either representatives could consult the specific represented (since interests cannot be separated from the specific individuals) and act accordingly, or they could try to implement the objective interests of the represented. Interests are objective in a sense that they are not linked to specific individuals (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1972). In both cases, representatives first have to interpret who the represented are. This idea relates to a wider discussion about the priority of representatives or the represented among the theorists of political representation (Näsström Reference Näsström and Vieira2017). Ankersmit (Reference Ankersmit2002) claims that political reality in general and the represented in particular do not exist without representation. Similarly Mansbridge (Reference Mansbridge2003) calls representation constituting because the legislators do not just respond to the preferences of citizens but actively create them. The specific constituency does not pre-exist, but is constantly created and redefined during the process of representation.

However, Pitkin rejects the priority of the representatives. Even though the represented might not be able to articulate and define their own interests, they objectively exist and are logically prior to representation (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1972). In that case, two possible solutions to the question of how to represent those who do not articulate their common interests clearly can be suggested.

First, representatives have to consider the interests, but not wishes, of the represented. They also have to be able to explain why wishes do not correspond to the actual interests of the represented (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1972). That means that the represented should be guaranteed only ‘potential responsiveness, access to power rather than its actual exercise’ (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1972, 233). But at the same time the elected representatives are accountable to those on whose behalf they act (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1972). The represented have the possibility to reject the decisions made by the representatives because representation is an institutionalized and functioning structure for the implementation of representativity, and a system that arises from activities of different people and groups (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1972). A representative government is inseparable from regular and free elections, which create systematic responsiveness. The representative government creates a space for the represented to object. If the represented are represented poorly, they can choose a competing group of representatives (for example another political party) in the next election.

Second, if representation is understood as a process, it consists of different representative moments. The most obvious and decisive moment of the representative process is the election, when citizens cast their vote. Prior to an election, representation process is a constant negotiation between the representatives and the represented. Political parties present their own image and their interpretation of who their constituents are in the election manifestos. Voters then interpret the election manifestos and decide if the interpretation provided corresponds to how they define themselves and their interests. Voters also interpret the whole governing process to decide who has represented them best, and when. The same applies not only to manifestos but also to all communicative content created by the political parties.

To sum up, these two answers to the question of how to represent those who do not articulate their common interests clearly suggest that, in the process of representation, both representatives and citizens are present. I argue that to understand the populist conception of representation we need to analyse how the representatives (in this case Lithuanian populist parties) interpret and define (1) who are to be represented and what their interests are, and (2) who are to do the representing.

Data and Methods

Qualitative content analysis is aimed to reveal the conception of representation of the Lithuanian populist parties. This section introduces case selection, data sources and the data analysis process.

Six Lithuanian populist political parties have been selected for the content analysis. The highest proportion of the populist characteristic appeared in the manifestos for the 2016 parliamentary elections of the following Lithuanian political parties and coalitions:Footnote 1 the S. Buškevičius and Nationalists’ Coalition; political party ‘Lithuanian list’; Anti-Corruption Coalition of Kristupas Krivickas and Naglis Puteikis; Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania – Christian Families Alliance; political party ‘The Way of Courage’; and Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union. These parties had never been in a governing coalition before the election of 2016, except for the Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania-Christian Families Alliance. During the parliamentary elections in 2016, the Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union got the largest number (56) of the seats in the parliament and now leads the Lithuanian government. The Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania – Christian Families Alliance got eight seats, while the Political party ‘Lithuanian list’ and the Anti-Corruption Coalition each got one seat in the parliament.

The primary data source was political parties’ programmes for the Lithuanian parliament (Seimas) elections in 2016. As election manifestos are usually of a technical nature, articles and messages published on political parties’ web pages were also included in the analysis. The dataset included all articles from the beginning of the campaign of the 2016 Lithuanian parliament election (9 April 2016) until the end of September 2017. Numbers and length of articles on political parties’ web pages is summarized in the Appendix.

Data analysis involved several steps. First, I coded the textual content of political parties (programmes and articles) according to whether they mentioned the represented and the representatives. Coding allowed us to categorize and sort text fragments according to specific characteristics (Saldaña Reference Saldaña2009). I chose a paragraph as a coding unit because it is a clear structural component of the text which indicates distinct themes and arguments (Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn, De Lange and Van der Brug2014). Second, I applied the principles of the interpretative analysis to find out how populist political parties define the represented and the representatives. Interpretative studies are based on the assumption that truths about events are constructed intersubjectively. It means that perceptions of reality are reached only through the interaction between researchers and subjects of the research when they attempt to interpret the events. The researcher participates in a meaning-making process in order to reveal intertextual links between different data sources. It is followed by a continuous reflection on how the creation of meaning was done, constant checking of explanations and repetitions in order to temper absolute subjectivity and the influence of side effects. Different interpretations are analysed and discussed in the text of the study (Yanow and Schwartz-Shea Reference Yanow and Schwartz-Shea2006).

Populists and Representation in Lithuania

Lithuania, a former Soviet state, is characterized by an unstable party system, low trust in political institutions and low levels of political participation. The country is the most pro-European Member State: 66% of the society tends to trust the European Union (European Commission 2018). This can partially be explained by the fact that the country has not experienced the challenges of the recent waves of immigration. In 2017, only 258 people were granted protection and 84 refugees were resettled (UNHCR 2018). Even though Lithuania has not had to deal with the immigration crisis and Euroscepticism so far, its party system did not escape the populist challenge. Since 2000, new political parties (most of which qualify as populist) successfully entered the parliament in every election. Most of the new parliamentary populist parties in Lithuania (Labour Party, Lithuanian Liberal Union and New Union) have been previously categorized as examples of new/centrist populism (Pop-Eleches Reference Pop-Eleches2010) and only Order and Justice has been called a radical right-wing party (Ramonaitė and Ratkevičiūtė Reference Ramonaitė, Ratkevičiūtė, Grabo and Hartleb2013; Pabiržis Reference Pabiržis2013).

This section of the article presents the empirical results outlined according to the above-mentioned theoretical dimensions: (1) who are to be represented and what their interests are; (2) who are to do the representing. During the data analysis, a third dimension has been added: who not to represent. Populist political parties describe themselves as good representatives while constantly referring to inadequate representation.

Who are to be Represented and What their Interests Are?

In the discourse of the Lithuanian populist parties the most common category of the represented is the people. This is not surprising as, essentially, all populist parties refer to ‘the people’ as a homogeneous entity, rather than as consisting of groups with different interests. Despite that, the discourse of the political parties varies. The Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union most often referred to an even more abstract category of the represented – the society. The Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania – Christian Families Alliance most of often referred to citizens or civil society as a general category of the represented.

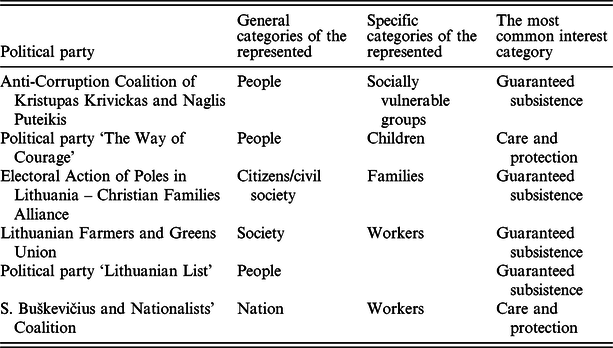

The Lithuanian populist parties do not refer only to the general categories of the represented but combine references to the general will of the people with the representation of certain interest groups. The results are summarized in Table 1. The Anti-Corruption Coalition of Kristupas Krivickas and Naglis Puteikis often referred to socially vulnerable groups of society; the political party ‘The Way of Courage’ to children; the Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania – Christian Families Alliance to families; the Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union, and the S. Buškevičius and Nationalists’ Coalition ‘Against the Corruption and Poverty’, to workers.

Table 1. The represented and their interests.

As far as the interests of the represented are concerned, the populist political parties claim that people need to be protected and taken care of. That involves attention, problem solving, justice and dignity, protection from the authorities and other potentially threatening actors. The represented are defined as weak and mistreated. The image of the underrepresented people is reinforced by references to the specific groups of the represented such as socially vulnerable groups, children and workers.

Even though the populist political parties refer to different social groups, they define the represented as having common rather than conflicting interests (such as income and material support). Common interest is what unites different social groups and eliminates their differences. Unity of the people is a necessary condition for fair and well-implemented policies. Therefore, internal disagreements among the people lead to an unsatisfactory situation of people and should be resolved:

I think that the biggest problem which our society faces and all the governments have been successfully cultivating through the ‘divide and conquer’ policies is the struggle between all social groups: employers against workers, pensioners against young families, businessmen against officials, etc. But we all understand that we cannot exist without each other, and neither one nor the other is in itself a kind of evil that should be fought with (restricted, controlled, or destroyed) all the time. It is necessary to seek commonality, consensus among all social groups, because only if we are united we can achieve good life in Lithuania. (Political party ‘Lithuanian List’)

Our task is to consolidate the society with the principles of solidarity, support socially oriented business initiatives, and deal with various forms of social injustice. Only in such a society people of Lithuania would create a prosperous and dignified life. (Political party ‘The Way of Courage’)

Who are to do the Representing?

The populist political parties claim to provide an alternative to the current inappropriate representation. They try to distance themselves from the mainstream politicians by describing themselves as having new ideas, being selfless, moral and competent.

First, the Lithuanian populist parties define themselves as the new politicians who propose new ideas and changes (Table 2). The political party ‘Lithuanian List’ speaks about new ideas and suggests an abstract alternative, the Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union claim that they are an alternative to the mainstream political parties, the political party ‘The Way of Courage’ suggests electoral reforms.

Table 2. Proper and improper representatives.

While the S. Buškevičius and Nationalists’ Coalition claim to change ‘the political reality of Lithuania’, the Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union and Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania – Christian Families Alliance suggest abstract changes:

If this is the will of the people of Lithuania, and your will has led me to stand today as a candidate on this podium, I do not see another way than to make decisive, inevitable, reasonable changes. I just want to repeat that changes are not a revolution, it is not radicalism, and they must be considered and evaluated. (Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union)

He [party leader Valdemar Tomaševski] stressed that people in Lithuania are already waiting for change, that it is necessary to increase the income. (Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania – Christian Families Alliance)

Second, the Lithuanian populist parties describe themselves as moral politicians. They claim to bring back moral values, honesty, justice to politics. The Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union promise that their politicians are moral, while the Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania – Christian Families Alliance and the S. Buškevičius and Nationalists’ Coalition claim to foster Christian values.

We emphasize the principle of justice, integrity and high moral standards in all spheres of life. (Political party ‘The Way of Courage’)

It is a team of honest and principled people, based on values that fosters national and Christian ideas. (S. Buškevičius and Nationalists’ Coalition)

Specific content of moral values is not articulated, nevertheless, the parties claim to be guided by these abstract moral principles. Members of these parties are supposed to be good representatives because they are good and moral people, as opposed to the current governing elite. A more specific characteristic of the eligible representatives is their selflessness. According to the Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union, the Political party ‘Lithuanian List’ and the Anti-Corruption Coalition of Kristupas Krivickas and Naglis Puteikis, they do not seek political power for themselves.

Third, they describe themselves as competent, diligent and professional. Competence, rather than the ability to manage or to lead, is required to implement the policies that benefit the people. Diligence and competence align with selflessness. The image of the expert representatives is the most prominent in the discourse of Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union. A quote from a current Prime Minister Saulius Skvernelis illustrates it well:

Therefore, this time we are also trying to gather a reliable and professional team, which would not act politically after the elections, but would immediately start working on what is necessary for the state and bring the long-awaited changes for the population. The time has come to implement a decisive reform of the state apparatus. […] There will be no election for two years, so the opponents’ cheap populism and pandering to the different interest groups will not interfere with the implementation of the political will. (Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union)

According to this concept of representation, professionals or experts are expected to be better representatives than self-interested and not transparent party members. Professionals and experts are objective political actors and can implement what is supposedly objectively best for the represented. Professionalism here involves not only expertise or competence but precisely the lack of adherence to narrow specific interests.

Finally, the representatives have to constantly communicate with the represented to avoid pursuing their own interests. The eligible representatives have to initiate the continuous process of communication with the represented. Politicians should be interested to inquire and to listen to the represented:

The goal of Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania – Christian Families Alliance aims to create a dialogue between the government and the citizens through its policies and participation in the upcoming elections to the Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania. The government must be able to hear and listen about people’s lives, about their problems and their expectations. (Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania – Christian Families Alliance)

I believe that a member of the Seimas, especially if elected in the single-member constituency, must not be alienated from the concerns and problems of people, has to know them and help solve them, has to attend meetings and events, because ideas for law amendments are often born there. (Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union)

This process of uninterrupted communication ensures the permanent presence of the people in the decision-making process. Representatives only collect people’s concerns and problems to be able to serve them. It expresses the idea that the people must make decisions, and representatives are merely the instruments for the will of the represented. The people can govern when they are involved in the process or are inquired about their issues. When the representatives are identical to people, any discrepancy between the decisions made by the represented and their representatives disappears. Politicians have the same information as the people, so they can make good decisions for everyone. The question of the accountability and responsiveness of the representatives becomes irrelevant, since there must be no gap between the representatives and the represented throughout the whole political decision-making process. Representatives are the same as the people, so they do not need to be supervised or controlled.

Who Not to Represent?

Another cause of the unsatisfactory situation of the people (besides the lack of their unity) is the lack of representation. The link between the government and the citizens is claimed to be broken. The government is indifferent, detached from the destitute citizens, not concerned with their needs, and, therefore, it does not fulfil its primary function to meet the needs of the represented. This is all a consequence of the long-term governance of the mainstream political parties. They are described as a self-sufficient closed governing system or as corrupt political actors (Table 2).

The Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union, the political party ‘The Way of Courage’ and the political party ‘Lithuanian List’ describe the mainstream political parties as self-sufficient closed systems, which either do not let new members in or depend on the will of the party leader. They refer to the government as a certain place of power, which is occupied by selfish political actors (narrow interest groups, nomenclature, a degenerate party system, political class) deliberately failing to meet the needs of represented:

We also propose to abolish the anti-democratic principles and restrictions of party financing, which preserve the current degenerate party system and nomenclature; to reform the electoral system in the direction of better democracy and of restricting the influence of party nomenclature. (Political party ‘The Way of Courage’)

For the ruling multiparty political class, which has formed over a quarter of a century, for its majority, the state is an object of management – that there should be something to control, because most of the class members cannot do anything else or have already forgotten it. It is also likely that the nicely packed slogans of poverty reduction actually speak about the rulers creating a class that will support them during the next election. (Political party ‘Lithuanian List’).

The other way of describing the mainstream political parties is emphasizing political parties’ self-interest. Corruption is only an indication of the fact that political parties are untrustworthy and pursue their own interests instead of working for the benefit of all. It is most explicit in the discourse of the political party ‘Lithuanian List’, the Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union and the Anti-Corruption Coalition of Kristupas Krivickas and Naglis Puteikis:

It is written in black and white that the party works and seeks power for the benefit of its members. I was looking in vain for the suffixes [sic] that, when they came to power, the parties ruled the state in favour of all… (Political party ‘Lithuanian List’)

It is the same problem with the Lithuanian elite that the Lithuanian elite primarily takes care of itself and usually forgets to take care of all the residents. (Anti-Corruption Coalition of Kristupas Krivickas and Naglis Puteikis)

Selfishness is a dominating adjective in both lines of criticism towards mainstream political parties. The concept of ‘interest’ is not neutral in the populist discourse. Interests can either be good (such as national, public and citizens’ interests) or bad (interests of businesspeople, parties and elites), depending on whether these are interests of all or partial interests. The businesspeople and elites are understood as having selfish partial interests. The mainstream political parties are intertwined with businesspeople and elites, and they also pursue their own interests, rather than the public interest. Good representation means taking care of the public interest. That means a political representative is supposed to represent the interests of all except the elite’s.

Conclusion

This article aimed to find out how populist parties define representation. The analysis reveals that the diversity of social groups and opinions is seen as an obstacle to successful representation. The Lithuanian populist parties describe the represented as weak and disadvantaged, and therefore the representatives must protect them and take care of them. Populist parties combine references to the general will of the people and the representation of specific groups of interests. The process of representation is aimed at resolving inner divisions in the represented subject ‘the people’. Therefore, it can be confirmed that the specific constituency does not pre-exist, but is constantly created and redefined during the process of representation.

To improve the situation of the represented, populist parties are supposed to communicate with them constantly. However, that does not lead to actual learning the interests of the represented. The initiative to inquire about the interests of the represented seems to be the prerogative of the representatives. Unlike in the theoretical definition of representation, in this case the represented are defined as unable to have and to formulate their own interests. Moreover, continuous communication leaves no space for diversity of opinion and disagreement. The question of the accountability and the responsiveness of the representatives becomes irrelevant – there should be no gap between the represented and the representatives in the political decision-making process.

The Lithuanian populist parties also attempt to create a common identity between themselves and the represented through the process of representation. Common moral values and diligence of the representatives provide grounds to emphasize similarities in the discourse of the Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union, Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania – Christian Families Alliance and S. Buškevičius and Nationalists’ Coalition.

Interestingly, the idea of expert government does not contradict the process of creating common identity in the discourse of the Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union. The idea of professionalism (in contrast to the leader figure) does not distinguish the representatives from the represented because anyone can be a professional, as opposed to being a party politician. The professionals have the highest qualifications, they do not pursue their personal interests and, therefore, they are non-political actors who can achieve what is objectively good for everyone. According to this logic, a technocratic government is easily compatible with populist ideas.

Furthermore, the link between politicians and voters is supposed to be based on trust. Voters are expected to trust the right representatives to implement abstract changes for the benefit of all. Political parties, elites, and businesspeople have interests, whereas the government should not have interests and act in the interests of all. Only the right representatives can bring about change and the well-being of all people. Therefore, politics in the populist concept of representation is a zero-sum game where the represented have to choose between the right and the wrong agent of representation.

It can be concluded that the analysis of the discourse on political representation provides new insights and this line of analysis should also be promising in other contexts. The difference between professionalism and leadership should be explored further to find out if it is specific to CEE countries due to their communist legacies. In addition, more qualitative studies should be carried out in order to analyse the tension between the selflessness of the populist parties and their concept of the ‘interest’.

About the Author

Jogilė Ulinskaitė is a Researcher at the Institute of International Relations and Political Science, Vilnius University. Her main research interests are populism, political representation, collective memory.

Appendix 1. Data sources