Introduction

One of the longest Hismaic inscriptions yet discovered comes from the region of Madaba, Jordan. It was published first in an Arabic article by Khraysheh in 2000Footnote 2 and was re-edited by Graf and Zwettler four years later.Footnote 3 Both editions remark on the striking similarity in language and style between this text and Classical Arabic. Indeed, this inscription, and a closely related text from Uraynibah West—also published by Graf and Zwettler in the same article— are among the best witnesses to the Arabic of this region during the Nabataean period. This article will offer a few remarks on the language of the Hismaic inscriptions, and then provide a new reading of Line 4 of the Madaba inscription, which had previously evaded satisfactory interpretation.

Part I: Notes on Hismaic chronology, morphology, and phonology

Hismaic, background and chronology

Hismaic is the name of an Ancient North Arabian script used in the Ḥismā desert and its surrounding areas up to central Jordan. The script was first identified by Winnett,Footnote 4 which he labelled “Thamudic E” and later “Tabuki” Thamudic.Footnote 5 G. King undertook the full-scale study of this script in her 1990 dissertation,Footnote 6 following which it was renamed “Hismaic”, reserving the label “Thamudic” for Ancient North Arabian scripts that were not fully understood. Although some have correctly questioned the wisdom of this geographically based term, especially since a growing number of inscriptions, especially the longer ones, come from beyond the Ḥismā, it has become widely accepted as the name of this alphabet and so suggestionsFootnote 7 to return to the label Thamudic E should be rejected.Footnote 8

Unlike Safaitic, there are no inscriptions in the Hismaic script proper that are dated to known events.Footnote 9 King summons some circumstantial evidence from anthroponyms attested in the corpus to suggest that the use of the Hismaic alphabet overlapped with the Nabataean period and its writers were within the kingdom's sphere of influence.Footnote 10 The onomasticon contains several Nabataean basilophoric names, such as ʿbdḥrtt (KJC 272) /ʿabdo-ḥāreṯat/ ‘servant of Aretas’;Footnote 11ʿbdʿbdt /ʿabdo-ʿobodat/ ‘servant of Obodas’ (KJC 574).Footnote 12 A small number of bilingual Hismaic-Nabataean inscriptions further indicate that the two writing traditions were contemporaneous.Footnote 13 Thus, while it is entirely possible, and even likely, that the Hismaic inscriptions predate the Nabataean kingdom, they at least continue after its establishment into the first century bce to the first century ce.

A few remarks on the language of the Hismaic Inscriptions

In my work on the classification of the languages of the Ancient North Arabian inscriptions, I have argued that the Hismaic inscriptions attest a variety of Old Arabic belonging to the northern Old Arabic dialect continuum, which includes Nabataean Arabic and Safaitic.Footnote 14 This is rather clear from the longer inscriptions, such as the one discussed here, but even the shorter texts provide important linguistic facts in support of this classification. The Hismaic inscriptions constitute their own linguistic cluster within the northern Old Arabic dialect continuum; hence, the following paragraphs will outline some aspects of Hismaic phonology and morphology not discussed in King's dissertation.

The most striking aspect of Hismaic is its lack of a definite article, which a group of bilingual Hismaic-Nabataean inscriptions clearly illustrates.Footnote 15 A small minority of Safaitic texts lack the definite article as well. Since the article is an innovative feature in Semitic, Hismaic likely preserves the Proto-Arabic situation, while later dialects developed various forms of definite marking, ha-, ʾal-, ʾam, ʾa-, etc.Footnote 16

Proto-Arabic preserved the triphthong of III-w/y roots and these survive in Safaitic: rʿy [raʕaya] ‘he pastured’ and ʾtw [ʔatawa] ‘he came’. Hismaic sometimes collapses the triphthong of III-w verbs to long vowel, perhaps /ā/: dʿ [daʕā] ‘he invoked’ < *daʕawa,Footnote 17 but rʿy [raʕaya] ‘he pastured’, paralleling the situation found in the Quranic Consonantal Text.

Like Classical Arabic, Hismaic distinguishes between an indicative and subjunctive verb: ybk ‘he weeps’Footnote 19 vs. ygzy ‘that he may fulfill’.Footnote 20 The final glide of the root is represented orthographically in the subjunctive while it is unrepresented in the indicative. This pattern of spelling indicates that the subjunctive ended in a consonantal glide while the indicative terminated in a long vowel, a fact that supports the following reconstruction:Footnote 21

Since this mood ending survived on verbs, it is reasonable to assume that the /a/ of the accusative survived on nouns as well, as no phonological erosion of this vowel occurred. No environments in which to detect such an ending, however, have presented themselves.

One inscription provides positive evidence for the survival of the nominative case. In a text recently published in J. Healey's Festschrift from the area of Wādī Ramm, M. C. A. Macdonald ingeniously recovered the vowels on the boundary of words based on the patterns in the loss of the glottal stop.Footnote 23 The inscription reads, following the editio princeps:

l ʾbslm bn qymy d ʾl gśm w dkrt-n lt w dkrt lt wśyʿ-n kll-hm

‘By ʾbslm son of Qymy of the lineage of Gśm and may Allāt be mindful of us and may Allāt be mindful of all our companions’.

Macdonald noticed that the spelling of the second invocation, dkrt lt wśyʿn kll-hm, indicated that the glottal stop of what was originally ʾśyʿ-n /ʔaśyāʕa-nā/ had disappeared, resulting in a homo-organic glide w. The value of the glide, in turn, shows that the previous word terminated in an u-vowel: *allātu ʔaśyāʕa-nā > allātu aśyāʕa-nā. The word-boundary sequence ua was rendered with w.

While Macdonald proved the existence of a final u on Allāt, he did not offer an explanation as to its origin. He does point out, however, that the divine name Allāt is spelled ʾltw in Nabataean inscriptions from this region,Footnote 24 but this only indicates that the Nabataean form terminated in a final u-class vowel as well. I have argued in length,Footnote 25 agreeing with the opinion of Diem,Footnote 26 that this final -w, conventionally termed Nabataean wawation, derives etymologically from the nominative case. While Arabic case inflection is neutralised in an Aramaic syntactic context, hence the non-inflection of such names in most of the Nabataean Aramaic inscriptions, the ʿEn ʿAvdat Arabic inscription, written in the classical Nabataean script, exhibits a fully functioning case system.Footnote 27 In this light, I would suggest that the aforementioned Hismaic inscription provides further evidence for nominal case inflection in the Arabic of this region.Footnote 28

The genitive case is attested once in a word-boundary position in the form of a homo-organic glide arising from the loss of the glottal stop.

CTSS 3:

l ṣhḥ bn wd ḏyl nʾlt w ḏkrt lt kll rhṭ ṣ{d}q

‘By Ṣhḥ son of Wd of the lineage of Nʾlt and may Allāt be mindful of every righteous kinsman’

The phrase ḏyl is spelled in all other circumstances as ḏ ʾl. The use of the y indicates that the vowel of the relative pronoun was ī, which is expected considering that it is in apposition with the personal name following the preposition l-. In order to prove beyond a doubt the existence of inflection in this pronoun, however, we would require a similar spelling in a nominative context with w, which has not yet been attested. Yet it might be significant that Nabataean Arabic exhibits dw for the relative pronoun, e.g. dwšrʾ [ḏū-śarē], which indicates that at least originally the Arabics of this region inflected the relative marker for case.

While the evidence is fragmentary, as can be expected from the purely consonantal script, it is consistent with the Arabic (and Proto-Semitic) case system, suggesting that nominal declension and the verbal moods remained intact in Hismaic.

Hismaic employs the bar with two circles, ![]() , to represents etymology *g,Footnote 29 a particularity shared perhaps with some varieties of Thamudic C.Footnote 30 Knauf,Footnote 31 following Voigt,Footnote 32 has argued that the use of this glyph suggests the shift of *[g] to either [ʒ] (ž in Voigt's transcription and ĵ in Knauf's) or [j] (y in Knauf's transcription).Footnote 33 While there are unfortunately no bilingual Hismaic-Greek inscriptions to help determine the phonetic values of the Hismaic consonants, transcriptions of foreign personal names in this alphabet can inform our understanding of their realisation. Hismaic employs the

, to represents etymology *g,Footnote 29 a particularity shared perhaps with some varieties of Thamudic C.Footnote 30 Knauf,Footnote 31 following Voigt,Footnote 32 has argued that the use of this glyph suggests the shift of *[g] to either [ʒ] (ž in Voigt's transcription and ĵ in Knauf's) or [j] (y in Knauf's transcription).Footnote 33 While there are unfortunately no bilingual Hismaic-Greek inscriptions to help determine the phonetic values of the Hismaic consonants, transcriptions of foreign personal names in this alphabet can inform our understanding of their realisation. Hismaic employs the ![]() glyph to transcribe the Nabataean personal name ʿbdʾlgy, spelled ʿbdlg (KJC 205) and perhaps an Aramaicised version ʿbdgy (Berard 1). The pronunciation of Nabataean g was certainly [g], as this phoneme is transcribed consistently with Greek Gamma, which in this period and region retained its original value as a voiced velar stop [g].Footnote 34

glyph to transcribe the Nabataean personal name ʿbdʾlgy, spelled ʿbdlg (KJC 205) and perhaps an Aramaicised version ʿbdgy (Berard 1). The pronunciation of Nabataean g was certainly [g], as this phoneme is transcribed consistently with Greek Gamma, which in this period and region retained its original value as a voiced velar stop [g].Footnote 34

Thus, the choice to render this phoneme with the Hismaic glyph ![]() suggests that it was the closest approximate to that sound in the language. This is hard to imagine if it were truly realised as [ʒ]. If the reconstructions of Voigt or Knauf were true, one would rather expect the use of the <k>, <q> or even the <ġ> glyphs to represent foreign [g]. This simple observation, I believe, supports the identification of the phonetic value of this sound as either [g], or perhaps a voiced palatal stop [ɟ], but certainly not a sibilant or approximant.

suggests that it was the closest approximate to that sound in the language. This is hard to imagine if it were truly realised as [ʒ]. If the reconstructions of Voigt or Knauf were true, one would rather expect the use of the <k>, <q> or even the <ġ> glyphs to represent foreign [g]. This simple observation, I believe, supports the identification of the phonetic value of this sound as either [g], or perhaps a voiced palatal stop [ɟ], but certainly not a sibilant or approximant.

This observation is further supported by the spelling of tribal name gśm /gośam/, which occurs in both Safaitic (CSNS 421) and Hismaic (JSTham 695-696), with the ![]() glyph in Hismaic and the 0 glyph (= [g]) in Safaitic. If the men who carved these inscriptions belonged to the same group, then it would suggest that Hismaic and Safaitic g were phonetically close if not identical. If the tribal name originated in Hismaic, then it would be rather odd to render one of Voigt's or Knauf's reconstructed values with the g glyph in Safaitic, and vice versa.Footnote 35

glyph in Hismaic and the 0 glyph (= [g]) in Safaitic. If the men who carved these inscriptions belonged to the same group, then it would suggest that Hismaic and Safaitic g were phonetically close if not identical. If the tribal name originated in Hismaic, then it would be rather odd to render one of Voigt's or Knauf's reconstructed values with the g glyph in Safaitic, and vice versa.Footnote 35

Part II: A re-reading of Line 4 of the Madaba Inscription

As mentioned in the introduction, the Madaba Hismaic inscription is one of the longest witnesses to the language of the Hismaic inscriptions. We will give Graf and Zwettler's reading and interpretation here, and then offer an alternative understanding of the text based on a re-interpretation of Line 4.

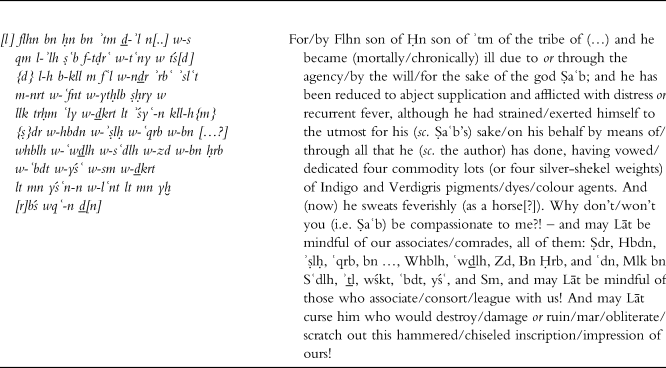

Reading and Translation of Graf and Zwettler 2004Footnote 36

Let us re-examine Line 4, specifically, the sentence which Graf and Zwettler parse as w-ytḥlb ṣḥry and translate as ‘and he sweats feverishly like a horse’ or as ‘my body flows with my sweat’, an alternative offered in the commentary. Both interpretations strain credulity, even though they draw upon words attested in the Arabic dictionaries. Graf and Zwettler connect ytḥlb with the Classical Arabic verb taḥallaba ‘he perspired/sweated’ and the word ṣḥry with the noun ṣuḥār, meaning ‘sweat’, ‘fever’, usually associated with horses. They explain away the final y away as a first person possessive pronoun. This, however, would be at odds with the third person verb preceding it. In order to produce a more grammatically agreeable interpretation, they prefer to take the y as a nisbah adjectival ending, producing the strange expression ‘my horse-like sweat’. Neither of these options seems very convincing to me, especially in light of the structure of the inscription. At this point in the text, the author describes his deeds of atonement: he has vowed four commodity lots of dyes and so, logically, we should expect here another related activity before requesting mercy from the deity.

Al-Khraysheh parses this sentence as w ytḥl b-ṣḥry, connecting the verb with the Sabaic ḥlʾ ‘to pay a sin-offering’. He explains the absence of the final alif, that is, glottal stop, by arguing that it had become an “alif-maqṣūrah”. While there is evidence for the loss of the glottal stop in Hismaic, such a sound change fails to explain the spelling in our text. The attested outcome of the loss of a glottal stop is y, as in yqry (MNM b 6) < *yiqraʔu. It should also be noted that the glottal stop is not omitted in any other environment in this text. CTSS 3 is an example of an inscription lacking the glottal stop and it spells the phrase ḏ ʾl ‘he of the lineage’ as ḏ yl, while in the present text the phrase is spelled correctly as ḏ ʾl. Thus, while it is not impossible to imagine that the loss of a glottal stop in final position produced an unwritten long ā, this remains only a theoretical possibility not borne out in any text. I believe that such explanations should be a last resort, and must always be strongly supported by the word's context in an inscription, which is clearly not the case for ytḥl.

Al-Khraysheh takes ṣḥry as the name of a shrine, which is entirely speculative and unprovable, and motivated only by his interpretation of ytḥl—ultimately a circular argument. While I agree with al-Khraysheh's parsing of the text over that of Graf and Zwettler, I will suggest a new interpretation of these words.

ytḥl: The verbs ḥl /ḥalla/ and ḥll /ḥallala/ are common in both the Safaitic and Hismaic inscriptions, and refer to encamping in a region. A form with a t-prefix, tḥll, is also attested in Safaitic, perhaps meaning ‘to depart’, but this likely reflects the tD-stem.Footnote 37 I posit that the present verb is the prefix conjugation of a t-stem from the root ḥll, meaning ‘to encamp’. We are prevented from understanding this verb as a tD-stem (= form V) as l of this geminate root is written only once. Thus, the verb must be cognate with the Classical Arabic Gt-stem (form VIII, which is identical in meaning with form I), yet here with a prefixed rather than infixed t. A prefixed tG-stem occurs in non-Classical forms of Arabic, such as in the Cairene dialect, itfaʕal, yitfaʕal, although there it has a passive meaning. The prefixed tG-stem is also attested in Aramaic.Footnote 38

b-ṣḥry: I believe the best understanding of this phrase, in light of our interpretation of ytḥl, is ‘in the desert’. The noun ṣḥry corresponds to Classical Arabic ṣaḥrāʔu. Classical Arabic, along with most, later forms of the language, experienced the sound change āy > āʔ,Footnote 39 e.g. Proto-Semitic *samāyum, Safaitic smy /samāy/ but Classical Arabic samāʔun, and was likely pronounced /ṣaḥrāy/. The absence of a definite article is expected in Hismaic.

Thus, the sentence should be understood as: ‘and he encamped/will encamp in the desert’. The matter of tense is difficult to decide. The prefix conjugation, used here, may reflect a narrative use, where it is contextually past tense, perhaps employed stylistically to mark the end of a sequence of atonement activities. We may equally understand this form as a future tense, introducing another promise to the deity in order to complete the author's repentance.

So then, how are we to understand these words in light of the rest of the inscription? I would suggest that this is a votive text of the penitential genre, similar, but not identical, to the South Arabian penitential texts from Haram.Footnote 40 It would be wrong to ignore the fact that all three Madaba inscriptions (the present one and two others known so far) and the Haram texts employ a sequence of verbs derived from the roots ḍrʿ and ʿnw. In South Arabia, these are hḍrʿ and ʿnw as compared to tḍrʿ and tʿny in our text.Footnote 41 While the two types of inscriptions differ in more ways than they are similar, this commonality at the very least suggests that they belong to the same textual genre, as suggested already by Khraysheh.Footnote 42 It is possible that they both draw on a related oral formula, adapted to the different linguistic settings of the Sabaic of South Arabia and the Arabic of the southern Levant.

This fact should therefore inform our understanding of the first sentence, without word boundaries: sqmlʾlhṣʿb. Khraysheh understood it as sāqa mā li-ʾilāh ṣaʿb ‘he offered what was owed to the god Ṣaʿb’ cf. Classical Arabic sāqa ʾilay-hi š-šayʾa. I believe this interpretation is sound but can perhaps be improved in light of the South Arabian genre. If we take the text as penitential, we would expect a confessional component. In South Arabia, authors publicly confess various sins, while there is no clear description of a misdeed in our text if we follow Khraysheh's interpretation. Therefore, Graf and Zwettler's parsing of the phrase as sqm l-ʾlh ṣʿb might be preferred. In this case, sqm should not be taken as a physical illness, but instead as an expression signifying sickness as a consequence of sin, an idea that finds several Biblical parallels: Psalm 38:4 or Micah 6:13.Footnote 43 This meaning could have been intended in our text, or the verb could have shifted, through metonymy, to mean ‘to sin’: ‘to be ill (as a result of sin) > ‘to sin’. Perhaps in the North Arabian tradition, it was not necessary to state the exact details of one's transgression, but only to make clear that one had sinned against the deity or had become spiritually “ill” because of sin.

Once we understand the phrase as such, the rest of the inscription opens up. The author explains that he has transgressed against the god Ṣʿb, and then makes a supplication, publicly suffers, and exerts himself for the sake of the deity to atone for his misdeeds. He vows material goods and then goes into ritualistic social isolation, encamping in the desert, perhaps to purify himself of his sin.Footnote 44 Finally, he asks the deity to show mercy upon him, before ending his inscriptions with prayers for his companions and the protection of the text.

I offer the following translation of the text based on Graf and Zwettler but with my new readings in bold.

Sigla

CTSS: Hismaic inscriptions in V. A. Clark, “Three Safaitic Stones from Jordan”, Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 24 (1980), pp. 125–128.

DHH: Hismaic inscriptions in S. al-Theeb and M. al-Hayšān, Nuqūš Ṣafawīyah (Ṣafāʾyayah) min Qāʿ al-ʾarnabiyyāt Umm gadīr wa-l-ʿamāriyyah fī šamālī ʾl-mamlakat al-ʿarabiyyah al-saʿūdiyyah (Al-Riyāḍ, 2016).

KJC: Hismaic inscriptions in King, “Hismaic”.

MNM: Hismaic inscriptions J. T. Milik, “Nouvelles inscriptions sémitiques et grecques du pays de Moab”, Liber Annuus 9 (1958-59), pp. 330–358.