Within narrative-based video games the integration of storytelling, where experiences are necessarily directed, and of gameplay, where the player has a degree of autonomy, continues to be one of the most significant challenges that developers face. In order to mitigate this potential dichotomy, a common approach is to rely upon cutscenes to progress the narrative. Within these passive episodes where interaction is not possible, or within other episodes of constrained outcome where the temporality of the episode is fixed, it is possible to score a game in exactly the same way as one might score a film or television episode. It could therefore be argued that the music in these sections of a video game is the least idiomatic of the medium. This chapter will instead focus on active gameplay episodes, and interactive music, where the unique challenges lie. When music accompanies active gameplay a number of conflicts, tensions and paradoxes arise. In this chapter, these will be articulated and interrogated through three key questions:

Do we score a player’s experience, or do we direct it?

How do we distil our aesthetic choices into a computer algorithm?

How do we reconcile the players’ freedom to instigate events at indeterminate times with musical forms that are time-based?

In the following discussion there are few certainties, and many more questions. The intention is to highlight the issues, to provoke discussion and to forewarn.

Scoring and Directing

Gordon Calleja argues that in addition to any scripted narrative in games, the player’s interpretation of events during their interaction with a game generates stories, what he describes as an ‘alterbiography’.Footnote 1 Similarly, Dominic Arsenault refers to the ‘emergent narrative that arises out of the interactions of its rules, objects, and player decisions’Footnote 2 in a video game. Music in video games is viewed by many as being critical in engaging players with storytelling,Footnote 3 but in addition to underscoring any wider narrative arc music also accompanies this active gameplay, and therefore narrativizes a player’s actions. In Claudia Gorbman’s influential book Unheard Melodies: Narrative Film Music she identifies that when watching images and hearing music the viewer will form mental associations between the two, bringing the connotations of the music to bear on their understanding of a scene.Footnote 4 This idea is supported by empirical research undertaken by Annabel Cohen who notes that, when interpreting visuals, participants appeared ‘unable to resist the systematic influence of music on their interpretation of the image’.Footnote 5 Her subsequent congruence-associationist model helps us to understand some of the mechanisms behind this, and the consequent impact of music on the player’s alterbiography.Footnote 6

Cohen’s model suggests that our interpretation of music in film is a negotiation between two processes.Footnote 7 Stimuli from a film will trigger a ‘bottom-up’ structural and associative analysis which both primes ‘top-down’ expectations from long-term memory through rapid pre-processing, and informs the working narrative (the interpretation of the ongoing film) through a slower, more detailed analysis. At the same time, the congruence (or incongruence) between the music and visuals will affect visual attention and therefore also influence the meaning derived from the film. In other words, the structures of the music and how they interact with visual structures will affect our interpretation of events. For example, ‘the film character whose actions were most congruent with the musical pattern would be most attended and, consequently, the primary recipient of associations of the music’.Footnote 8

In video games the music is often responding to actions instigated by the player, therefore it is these actions that will appear most congruent with the resulting musical pattern. In applying Cohen’s model to video games, the implication is that the player themselves will often be the primary recipient of the musical associations formed through experience of cultural, cinematic and video game codes. In responding to events instigated by the player, these musical associations will likely be ascribed to their actions. You (the player) act, superhero music plays, you are the superhero.

Of course, there are also events within games that are not instigated by the player, and so the music will attach its qualities to, and narrativize, these also. Several scholars have attempted to distinguish between two musical positions,Footnote 9 defining interactive music as that which responds directly to player input, and adaptive music that ‘reacts appropriately to – and even anticipates – gameplay rather than responding directly to the user’.Footnote 10 Whether things happen because the ‘game’ instigates them or the ‘player’ instigates them is up for much debate, and it is likely that the perceived congruence of the music will oscillate between game events and players actions, but what is critical is the degree to which the player perceives a causal relationship between these events or actions and the music.Footnote 11 These relationships are important for the player to understand, since while music is narrativizing events it is often simultaneously playing a ludic role – supplying information to support the player’s engagement with the mechanics of the game.

The piano glissandi in Dishonored (2012) draw the player’s attention to the enemy NPC (Non-Player Character) who has spotted them, the four-note motif in Left 4 Dead 2 (2009) played on the piano informs the player that a ‘Spitter’ enemy type has spawned nearby,Footnote 12 and if the music ramps up in Skyrim (2011), Watch Dogs (2014), Far Cry 5 (2018) or countless other games, the player knows that enemies are aware of their presence and are now in active pursuit. The music dramatizes the situation while also providing information that the player will interpret and use. In an extension to Chion’s causal mode of listening,Footnote 13 where viewers listen to a sound in order to gather information about its cause or sources, we could say that in video games players engage in ludic listening, interpreting the audio’s system-related meaning in order to inform their actions. Sometimes this ludic function of music is explicitly and deliberately part of the game design in order to avoid an overloading of the visual channel while compensating for a lack of peripheral vision and spatial information,Footnote 14 but whether deliberate or inadvertent, the player will always be trying to interpret music’s meaning in order to gain advantage.

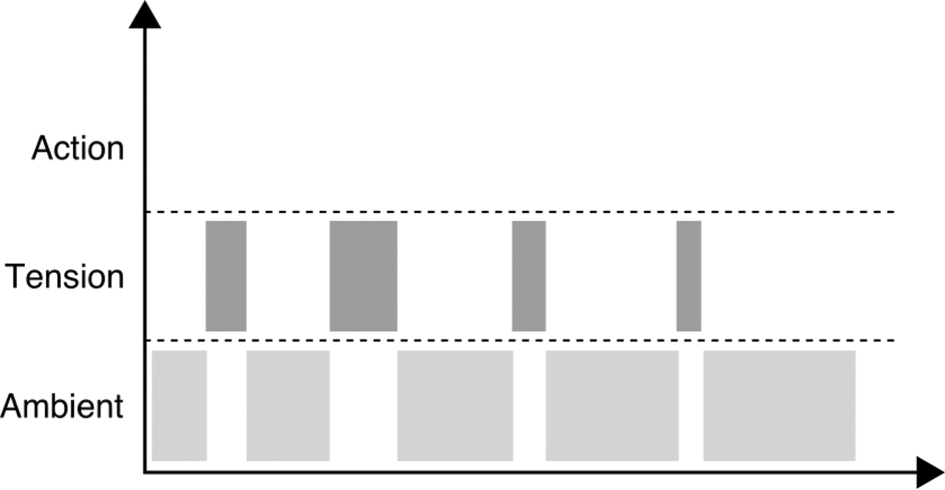

Awareness of the causal links between game events, game variables and music will likely differ from player to player. Some players may note the change in musical texture when crouching under a table in Sly 3: Honor Among Thieves (2005) as confirmation that they are hidden from view; some will actively listen out for the rising drums that indicate the proximity of an attacking wolf pack in Rise of the Tomb Raider (2015);Footnote 15 while others may remain blissfully unaware of the music’s usefulness (or may even play with the music switched off).Footnote 16 Feedback is sometimes used as a generic term for all audio that takes on an informative role for the player,Footnote 17 but it is important to note that the identification of causality, with musical changes being perceived as either adaptive (game-instigated) or interactive (player-instigated), is likely to induce different emotional responses. Adaptive music that provides information to the player about game states and variables can be viewed as providing a notification or feed-forward function – enabling the player. Interactive music that corresponds more directly to player input will likewise have an enabling function, but it carries a different emotional weight since this feedback also comments on the actions of the player, providing positive or negative reinforcement (see Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1 Notification and feedback: Enabling and commenting functions

The percussive stingers accompanying a successful punch in The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn (2011), or the layers that begin to play upon the successful completion of a puzzle in Vessel (2012) provide positive feedback, while the duff-note sounds that respond to a mistimed input in Guitar Hero (2005) provide negative feedback. Whether enabling or commenting, music often performs these ludic functions. It is simultaneously narrating and informing; it is ludonarrative. The implications of this are twofold. Firstly, in order to remain congruent with the game events and player actions, music will be inclined towards a Mickey-Mousing type approach,Footnote 18 and secondly, in order to fulfil its ludic functions, it will tend towards a consistent response, and therefore will be inclined towards repetition.

When the player is web-slinging their way across the city in Spider-Man (2018) the music scores the experience of being a superhero, but when they stop atop a building to survey the landscape the music must logically also stop. When the music strikes up upon entering a fort in Assassin’s Creed: Origins (2017), we are informed that danger may be present. We may turn around and leave, and the music fades out. Moving between these states in either game in quick succession highlights the causal link between action and music; it draws attention to the system, to the artifice. Herein lies a fundamental conflict of interactive music – in its attempt to be narratively congruent, and ludically effective, music can reveal the systems within the game, but in this revealing of the constructed nature of our experience it disrupts our immersion in the narrative world. While playing a game we do not want to be reminded of the architecture and artificial mechanics of that game. These already difficult issues around congruence and causality are further exacerbated when we consider that music is often not just scoring the game experience, it is directing it.

Film music has sometimes been criticized for a tendency to impose meaning, for telling a viewer how to feel,Footnote 19 but in games music frequently tells a player how to act. In the ‘Medusa’s Call’ chapter of Far Cry 3 (2012) the player must ‘Avoid detection. Use stealth to kill the patrolling radio operators and get their intel’, and the quiet tension of the synthesizer and percussion score supports this preferred stealth strategy. In contrast, the ‘Kick the Hornet’s Nest’ episode (‘Burn all the remaining drug crops’) encourages the player to wield their flamethrower to spectacular destructive effect through the electro-dubstep-reggae mashup of ‘Make it Bun Dem’ by Skrillex and Damian ‘Jr. Gong’ Marley. Likewise, a stealth approach is encouraged by the James-Bond-like motif of Rayman Legends (2013) ‘Mysterious Inflatable Island’, in contrast to the hell-for-leather sprint inferred from the scurrying strings of ‘The Great Lava Pursuit’. In these examples, and many others, we can see that rather than scoring a player’s actual experience, the music is written in order to match an imagined ideal experience – where the intentions of the music are enacted by the player. To say that we are scoring a player experience implies that somehow music is inert, that it does not impact on the player’s behaviour. But when the player is the protagonist it may be the case that, rather than identifying what is congruent with the music’s meaning, the player acts in order for image and music to become congruent. When music plays, we are compelled to play along; the music directs us. Both Ernest Adams and Tulia-Maria Cășvean refer to the idea of the player’s contract,Footnote 20 that in order for games to work there has to be a tacit agreement between the player and the game maker; that they both have a degree of responsibility for the experience. If designers promise to provide a credible, coherent world then the player agrees to behave according to a given set of predefined rules, usually determined by game genre, in order to maintain this coherence. Playing along with the meanings implicit in music forms part of this contract. But the player also has the agency to decide not to play along with the music, and so it will appear incongruent with their actions, and again the artifice of the game is revealed.Footnote 21

When game composer Marty O’Donnell states ‘When [the players] look back on their experience, they should feel like their experience was scored, but they should never be aware of what they did to cause it to be scored’Footnote 22 he is demonstrating an awareness of the paradoxes that arise when writing music for active game episodes. Music is often simultaneously performing ludic and narrative roles, and it is simultaneously following (scoring) and leading (directing). As a consequence, there is a constant tension between congruence, causality and abstraction. Interactive music represents a catch-22 situation. If music seeks to be narratively congruent and ludically effective, this compels it towards a Mickey-Mousing approach, because of the explicit, consistent and close matching of music to the action required. This leads to repetition and a highlighting of the artifice. If music is directing the player or abstracted from the action, then it runs the risk of incongruence. Within video games, we rely heavily upon the player’s contract and the inclination to act in congruence with the behaviour implied by the music, but the player will almost always have the ability to make our music sound inappropriate should they choose to.

Many composers who are familiar with video games recognize that music should not necessarily always act in the same way throughout a game. Reflecting on his work in Journey (2012), composer Austin Wintory states, ‘An important part of being adaptive game music/audio people is not [to ask] “Should we be interactive or should we not be?” It’s “To what extent?” It’s not a binary system, because storytelling entails a certain ebb and flow’.Footnote 23 Furthermore, he notes that if any relationship between the music and game, from Mickey-Mousing to counterpoint, becomes predictable then the impact can be lost, recommending that ‘the extent to which you are interactive should have an arc’.Footnote 24 This bespoke approach to writing and implementing music for games, where the degree of interactivity might vary between different active gameplay episodes, is undoubtedly part of the solution to the issues outlined but faces two main challenges. Firstly, most games are very large, making a tailored approach to each episode or level unrealistic, and secondly, that unlike in other art forms or audiovisual media, the decisions about how music will act within a game are made in absentia; we must hand these to a system that serves as a proxy for our intent. These decisions in the moment are not made by a human being, but are the result of a system of events, conditions, states and variables.

Algorithms and Aesthetics

Given the size of most games, and an increasingly generative or systemic approach to their development, the complex choices that composers and game designers might want to make about the use of music during active gameplay episodes must be distilled into a programmatic system of events, states and conditions derived from discrete (True/False) or continuous (0.0–1.0) variables. This can easily lead to situations where what might seem programmatically correct does not translate appropriately to the player’s experience. In video games there is frequently a conflict between our aesthetic aims and the need to codify the complexity of human judgement we might want to apply.

One common use of music in games is to indicate the state of the artificial intelligence (AI), with music either starting or increasing in intensity when the NPCs are in active pursuit of the player, and ending or decreasing in intensity when they end the pursuit or ‘stand down’.Footnote 25 This provides the player with ludic information about the NPC state, while at the same time heightening tension to reflect the narrative situation of being pursued. This could be seen as a good example of ludonarrative consonance or congruence. However, when analysed more closely we can see that simply relying on the ludic logic of gameplay events to determine the music system, which has narrative implications, is not effective. In terms of the game’s logic, when an NPC stands down or when they are killed the outcome is the same; they are no longer actively seeking the player (Active pursuit = False). In many games, the musical result of these two different events is the same – the music fades out. But if as a player I have run away to hide and waited until the NPC stopped looking for me, or if I have confronted the NPC and killed them, these events should feel very different. The common practice of musically responding to both these events in the same way is an example of ludonarrative dissonance.Footnote 26 In terms of providing ludic information to the player it is perfectly effective, but in terms of narrativizing the player’s actions, it is not.

The perils of directly translating game variables into musical states is comically apparent in the ramp into epic battle music when confronting a small rat in The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind (2002) (Enemy within a given proximity = True). More recent games such as Middle Earth: Shadow of Mordor (2014) and The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt (2015) treat such encounters with more sophistication, reserving additional layers of music, or additional stingers, for confrontations with enemies of greater power or higher ranking than the player, but the translation of sophisticated human judgements into mechanistic responses to a given set of conditions is always challenging. In both Thief (2014) and Sniper Elite V2 (2012) the music intensifies upon detection, but the lackadaisical attitudes of the NPCs in Thief, and the fact that you can swiftly dispatch enemies via a judicious headshot in Sniper Elite V2, means that the music is endlessly ramping up and down in a Mickey-Mousing fashion. In I Am Alive (2012), a percussive layer mirrors the player character’s stamina when climbing. This is both ludically and narratively effective, since it directly signifies the depleting reserves while escalating the tension of the situation. Yet its literal representation of this variable means that the music immediately and unnaturally drops to silence should you ‘hook-on’ or step onto a horizontal ledge. In all these instances, the challenging catch-22 of scoring the player’s actions discussed above is laid bare, but better consideration of the player’s alterbiography might have led to a different approach. Variables are not feelings, and music needs to interpolate between conditions. Just because the player is now ‘safe’ it does not mean that their emotions are reset to 0.0 like a variable: they need some time to recover or wind down. The literal translation of variables into musical responses means that very often there is no coda, no time for reflection.

There are of course many instances where the consideration of the experiential nature of play can lead to a more sophisticated consideration of how to translate variables into musical meaning. In his presentation on the music of Final Fantasy XV (2016), Sho Iwamoto discussed the music that accompanies the player while they are riding on a Chocobo, the large flightless bird used to more quickly traverse the world. Noting that the player is able to transition quickly between running and walking, he decided on a parallel approach to scoring whereby synchronized musical layers are brought in and out.Footnote 27 This approach is more suitable when quick bidirectional changes in game states are possible, as opposed to the more wholescale musical changes brought about by transitioning between musical segments.Footnote 28 A logical approach would be to simply align the ‘walk’ state with specific layers, and a ‘run’ state with others, and to crossfade between these two synchronized stems. The intention of the player to run is clear (they press the run button), but Iwamoto noted that players would often be forced unintentionally into a ‘walk’ state through collisions with trees or other objects. As a consequence, he implemented a system that responds quickly to the intentional choice, transitioning from the walk to run music over 1.5 beats, but chose to set the musical transition time from the ‘run’ to ‘walk’ state to 4 bars, thereby smoothing out the ‘noise’ of brief unintentional interruptions and avoiding an overly reactive response.Footnote 29

These conflicts between the desire for nuanced aesthetic results and the need for a systematic approach can be addressed, at least in part, through a greater engagement by composers with the systems that govern their music and by a greater understanding of music by game developers. Although the situation continues to improve it is still the case in many instances that composers are brought on board towards the end of development, and are sometimes not involved at all in the integration process. What may ultimately present a greater challenge is that players play games in different ways.

A fixed approach to the micro level of action within games does not always account for how they might be experienced on a more macro level. For many people their gaming is opportunity driven, snatching a valued 30–40 minutes here and there, while others may carve out an entire weekend to play the latest release non-stop. The sporadic nature of many people’s engagement with games not only mitigates against the kind of large-scale musico-dramatic arc of films, but also likely makes music a problem for the more dedicated player. If music needs to be ‘epic’ for the sporadic player, then being ‘epic’ all the time for 10+ hours is going to get a little exhausting. This is starting to be recognized, with players given the option in the recent release of Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey (2018) to choose the frequency at which the exploration music occurs.

Another way in which a fixed-system approach to active music falters is that, as a game character, I am not the same at the end of the game as I was at the start, and I may have significant choice over how my character develops. Many games retain the archetypal narrative of the Hero’s Journey,Footnote 30 and characters go through personal development and change – yet interactive music very rarely reflects this: the active music heard in 20 hours is the same that was heard in the first 10 minutes. In a game such as Silent Hill: Shattered Memories (2009) the clothing and look of the character, the dialogue, the set dressing, voicemail messages and cutscenes all change depending on your actions in the game and the resulting personality profile, but the music in active scenes remains similar throughout. Many games, particularly RPGs (Role-Playing Games) enable significant choices in terms of character development, but it typically remains the case that interactive music responds more to geography than it does to character development. Epic Mickey (2010) is a notable exception; when the player acts ‘good’ by following missions and helping people, the music becomes more magical and heroic, but when acting more mischievous and destructive, ‘You’ll hear a lot of bass clarinets, bassoons, essentially like the wrong notes … ’.Footnote 31 The 2016 game Stories: The Path of Destinies takes this idea further, offering moments of choice where six potential personalities or paths are reflected musically through changes in instrumentation and themes. Reflecting the development of the player character through music, given the potential number of variables involved, would, of course, present a huge challenge, but it is worthy of note that so few games have even made a modest attempt to do this.

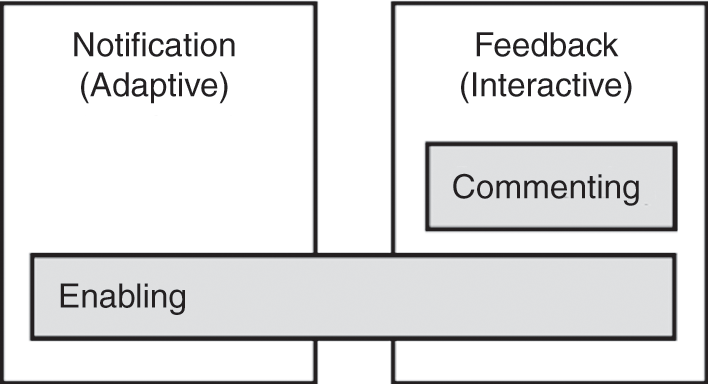

Recognition that players have different preferences, and therefore have different experiences of the same game, began with Bartle’s identification of common characteristics of groups of players within text-based MUD (Multi-User Dungeon) games.Footnote 32 More recently the capture and analysis of gameplay metrics has allowed game-user researchers to refine this understanding through the concept of player segmentation.Footnote 33 To some extent, gamers are self-selecting in terms of matching their preferred gaming style with the genre of games they play, but games want to appeal to as wide an audience as possible and so attempt to appeal to different types of player. Making explicit reference to Bartle’s player types, game designer Chris McEntee discusses how Rayman Origins (2011) has a co-operative play mode for ‘Socializers’, while ‘Explorers’ are rewarded through costumes that can be unlocked, and ‘Killers’ are appealed to through the ability to strike your fellow player’s character and push them into danger.Footnote 34 One of the conflicts between musical interactivity and the gaming experience is that the approach to music, the systems and thresholds chosen are developed for the experience of an average player, but we know that approaches may differ markedly.Footnote 35 A player who approaches Dishonored 2 (2016) with an aggressive playstyle will hear an awful lot of the high-intensity ‘fight’ music; however a player who achieves a very stealthy or ‘ghost’ playthrough will never hear it.Footnote 36 A representation of the potential experiences of different player types with typical ‘Ambient’, ‘Tension’ and ‘Action’ music tracks is shown below (Figures 5.2–5.4).

Figure 5.2 Musical experience of an average approach

Figure 5.3 Musical experience of an aggressive approach

Figure 5.4 Musical experience of a stealthy approach

A single fixed-system approach to music that fails to adapt to playstyles will potentially result in a vastly different, and potentially unfulfilling, musical experience. A more sophisticated method, where the thresholds are scaled or recalibrated around the range of the player’s ‘mean’ approach, could lead to a more personalized and more varied musical experience. This could be as simple as raising the threshold at which a reward stinger is played for the good player, or as complex as introducing new micro tension elements for a stealth player’s close call.

Having to codify aesthetic decisions represents for many composers a challenge to their usual practice outside of games, and indeed perhaps a conflict with how we might feel these decisions should be made. Greater understanding by composers of the underlying systems that govern their music’s use is undoubtedly part of the answer, as is a greater effort to track and understand an individual’s behaviour within games, so that we can provide a good experience for the ‘sporadic explorer’, as well as the ‘dedicated killer’, but there is a final conflict between interactivity and music that is seemingly irreconcilable – that of player agency and the language of music itself.

Agency and Structure

As discussed above, one of the defining features of active gameplay episodes within video games, and indeed a defining feature of interactivity itself, is that the player is granted agency; the ability to instigate actions and events of their own choosing, and crucially for music – at a time of their own choosing. Parallel, vertical or layer-based approaches to musical form within games can respond to events rapidly and continuously without impacting negatively on musical structures, since the temporal progression of the music is not interrupted. However, other gaming events often necessitate a transitional approach to music, where the change from one musical cue to an alternate cue mirrors a more significant change in the dramatic action.Footnote 37 In regard to film music, K. J. Donnelly highlights the importance of synchronization, that films are structured through what he terms ‘audiovisual cadences’ – nodal points of narrative or emotional impact.Footnote 38 In games these nodal points, in particular at the end of action-based episodes, also have great significance, but the agency of the player to instigate these events at any time represents an inherent conflict with musical structures.

There is good evidence that an awareness of musical, especially rhythmic, structures is innate. Young babies will indicate negative brainwave patterns when there is a change to an otherwise consistent sequence of rhythmic cycles, and even when listening to a monotone metronomic pulse we will perceive some of these sounds as accented.Footnote 39 Even without melody, harmonic sequences or phrasing, most music sets up temporal expectations, and the confirmation of, or violation of expectation in music is what is most closely associated with strong or ‘peak’ emotions.Footnote 40 To borrow Chion’s terminology we might say that peak emotions are a product of music’s vectorization,Footnote 41 the way it orients towards the future, and that musical expectation has a magnitude and direction. The challenges of interaction, the conflict between the temporal determinacy of vectorization and the temporal indeterminacy of the player’s actions, have stylistic consequences for music composed for active gaming episodes.

In order to avoid jarring transitions and to enable smoothness,Footnote 42 interactive music is inclined towards harmonic stasis and metrical ambiguity, and to avoiding melody and vectorization. The fact that such music should have little structure in and of itself is perhaps unsurprising – since the musical structure is a product of interaction. If musical gestures are too strong then this will not only make transitions difficult, but they will potentially be interpreted as having ludic meaning where none was intended. In order to enable smooth transitions, and to avoid the combinatorial explosion that results from potentially transitioning between different pieces with different harmonic sequences, all the interactive music in Red Dead Redemption (2010) was written in A minor at 160 bpm, and most music for The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt in D minor. Numerous other games echo this tendency towards repeated ostinatos around a static tonal centre. The music of Doom (2016) undermines rhythmic expectancy through the use of unusual and constantly fluctuating time signatures, and the 6/8 polyrhythms in the combat music of Batman: Arkham Knight (2015) also serve to unlock our perception from the usual 4/4 metrical divisions that might otherwise dominate our experience of the end-state transition. Another notable trend is the increasingly blurred border between music and sound effects in games. In Limbo (2010) and Little Nightmares (2017), there is often little delineation between game-world sounds and music, and the audio team of Shadow of the Tomb Raider (2018) talk about a deliberate attempt to make the player ‘unsure that what they are hearing is score’.Footnote 43 All of these approaches can be seen as stylistic responses to the challenge of interactivity.Footnote 44

The methods outlined above can be effective in mitigating the interruption of expectation-based structures during musical transitions, but the de facto approach to solving this has been for the music to not respond immediately, but instead to wait and transition at the next appropriate musical juncture. Current game audio middleware enables the system to be aware of musical divisions, and we can instruct transitions to happen at the next beat, next bar or at an arbitrary but musically appropriate point through the use of custom cues.Footnote 45 Although more musically pleasing,Footnote 46 such metrical transitions are problematic since the audiovisual cadence is lost – music always responds after the event – and they provide an opportunity for incongruence, for if the music has to wait too long after the event to transition then the player may be engaging in some other kind of trivial activity at odds with the dramatic intent of the music. Figure 5.5 illustrates the issue. The gameplay action begins at the moment of pursuit, but the music waits until the next juncture (bar) to transition to the ‘Action’ cue. The player is highly skilled and so quickly triumphs. Again, the music holds on the ‘Action’ cue until the next bar line in order to transition musically back to the ‘Ambient’ cue.

Figure 5.5 Potential periods of incongruence due to metrical transitions are indicated by the hatched lines

The resulting periods of incongruence are unfortunate, but the lack of audiovisual cadence is particularly problematic when one considers that these transitions are typically happening at the end of action-based episodes, where music is both narratively characterizing the player and fulfilling the ludic role of feeding-back on their competence.Footnote 47 Without synchronization, the player’s sense of accomplishment and catharsis can be undermined. The concept of repetition, of repeating the same episode or repeatedly encountering similar scenarios, features in most games as a core mechanic, so these ‘end-events’ will be experienced multiple times.Footnote 48 Given that game developers want players to enjoy the gaming experience it would seem that there is a clear rationale for attempting to optimize these moments. This rationale is further supported by the suggestion that the end of an experience, particularly in a goal-oriented context, may play a disproportionate role in people’s overall evaluation of the experience and their subsequent future behaviour.Footnote 49

The delay between the event and the musical response can be alleviated in some instances by moving to a ‘pre-end’ musical segment, one that has an increased density of possible exit points, but the ideal would be to have vectorized music that leads up to and enhances these moments of triumph, something which is conceptually impossible unless we suspend the agency of the player. Some games do this already. When an end-event is approached in Spider-Man the player’s input and agency are often suspended, and the climactic conclusion is played out in a cutscene, or within the constrained outcome of a quick-time event that enables music to be more closely synchronized. However, it would also be possible to maintain a greater impression of agency and to achieve musical synchronization if musical structures were able to input into game’s decision-making processes. That is, to allow musical processes to dictate the timing of game events. Thus far we have been using the term ‘interactive’ to describe music during active episodes, but most music in games is not truly interactive, in that it lacks a reciprocal relationship with the game’s systems. In the vast majority of games, the music system is simply a receiver of instruction.Footnote 50 If the music were truly interactive then this would raise the possibility of thresholds and triggers being altered, or game events waiting, in order to enable the synchronization of game events to music.

Manipulating game events in order to synchronize to music might seem anathema to many game developers, but some are starting to experiment with this concept. In the Blood and Wine expansion pack for The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt the senior audio programmer, Colin Walder, describes how the main character Geralt was ‘so accomplished at combat that he is balletic, that he is dancing almost’.Footnote 51 With this in mind they programmed the NPCs to attack according to musical timings, with big attacks syncing to a grid, and smaller attacks syncing to beats or bars. He notes ‘I think the feeling that you get is almost like we’ve responded somehow with the music to what was happening in the game, when actually it’s the other way round’.Footnote 52 He points out that ‘Whenever you have a random element then you have an opportunity to try and sync it, because if there is going to be a sync point happen [sic] within the random amount of time that you were already prepared to wait, you have a chance to make a sync happen’.Footnote 53 The composer Olivier Derivière is also notable for his innovations in the area of music and synchronization. In Get Even (2017) events, animations and even environmental sounds are synced to the musical pulse. The danger in using music as an input to game state changes and timings is that players may sense this loss of agency, but it should be recognized that many games artificially manipulate the player all the time through what is termed dynamic difficulty adjustment or dynamic game balancing.Footnote 54 The 2001 game Max Payne dynamically adjusts the amount of aiming assistance given to the player based on their performance,Footnote 55 in Half-Life 2 (2004) the content of crates adjusts to supply more health when the player’s health is low,Footnote 56 and in BioShock (2007) they are rendered invulnerable for 1–2 seconds when at their last health point in order to generate more ‘barely survived’ moments.Footnote 57 In this context, the manipulation of game variables and timings in order for events to hit musically predetermined points or quantization divisions seems less radical than the idea might at first appear.

The reconciliation of player agency and musical structure remains a significant challenge for video game music within active gaming episodes, and it has been argued that the use of metrical or synchronized transitions is only a partial solution to the problem of temporal indeterminacy. The importance of the ‘end-event’ in the player’s narrative, and the opportunity for musical synchronization to provide a greater sense of ludic reward implies that the greater co-influence of a more truly interactive approach is worthy of further investigation.

Conclusion

Video game music is amazing. Thrilling and informative, for many it is a key component of what makes games so compelling and enjoyable. This chapter is not intended to suggest any criticism of specific games, composers or approaches. Composers, audio personnel and game designers wrestle with the issues outlined above on a daily basis, producing great music and great games despite the conflicts and tensions within musical interactivity.

Perhaps one common thread in response to the questions posed and conflicts identified is the appreciation that different people play different games, in different ways, for different reasons. Some may play along with the action implied by the music, happy for their actions to be directed, while others may rail against this – taking an unexpected approach that needs to be more closely scored. Some players will ‘run and gun’ their way through a game, while for others the experience of the same gaming episode will be totally different. Some players may be happy to accept a temporary loss of autonomy in exchange for the ludonarrative reward of game/music synchronization, while for others this would be an intolerable breach of the gaming contract.

As composers are increasingly educated about the tools of game development and approaches to interactive music, they will no doubt continue to become a more integrated part of the game design process, engaged with not only writing the music, but with designing the algorithms that govern how that music works in game. In doing so there is an opportunity for composers to think not about designing an interactive music system for a game, but about designing interactive music systems, ones that are aware of player types and ones that attempt to resolve the conflicts inherent in musical interactivity in a more bespoke way. Being aware of how a player approaches a game could, and should, inform how the music works for that player.