Introduction

Suicide is a global health problem (WHO, 2018). A history of suicidal ideation is an important marker of future suicide risk (O'Connor & Nock, Reference O'Connor and Nock2014) and there are calls to more firmly identify suicidal ideation as a crucial target for intervention to reduce such risk (Jobes & Joiner, Reference Jobes and Joiner2019). The identification of factors preceding suicidal ideation is, therefore, pertinent to these early intervention efforts. To this end, many social, psychological, clinical and biological risk factors are known to be associated with suicidal ideation (O'Connor & Nock, Reference O'Connor and Nock2014), however, much of this research has been cross-sectional and atheoretical. As a result, the development and testing of theoretical models which highlight the pathways to suicidal ideation and behaviour have been identified as a priority in the field of suicide research (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Ghaderi, Harmer, Ramchandani, Cuijpers, Morrison and Craske2018).

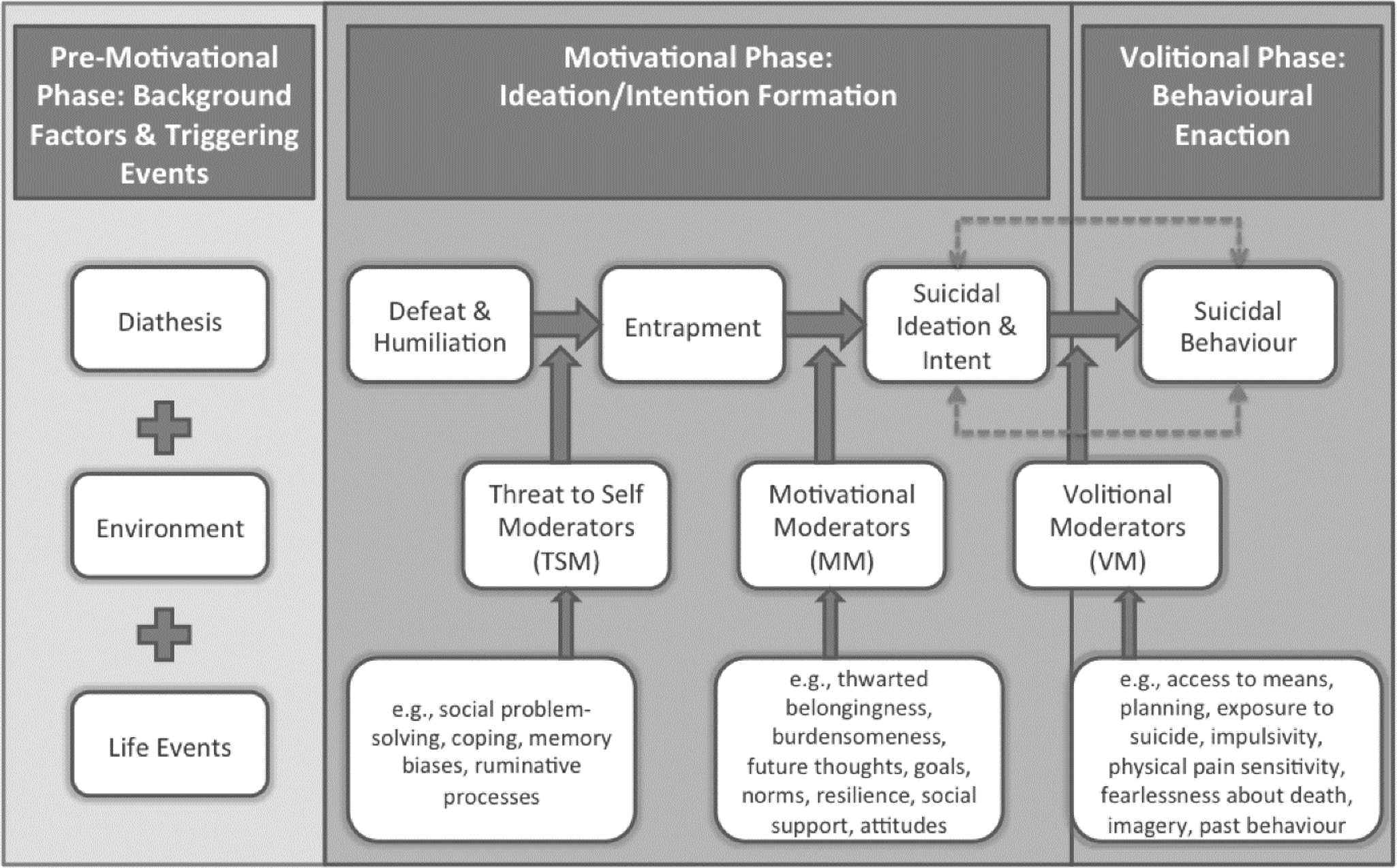

Indeed, two prominent psychological models, the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (IPT; Joiner, Reference Joiner2005) and the Integrated Motivational-Volitional Model (IMV) of suicidal behaviour (O'Connor, Reference O'Connor2011; O'Connor & Kirtley, Reference O'Connor and Kirtley2018), have endeavoured to address such gaps in our knowledge. These models posit that specific factors are central to the emergence of suicidal ideation. According to the IPT model (Fig. 1), the development of suicidal desire (ideation) is attributed to the interaction of thwarted belongingness (i.e. when the need for social connectedness goes unmet) and perceived burdensomeness (i.e. the belief that one is a burden to others or society) (Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte, & Joiner, Reference Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte and Joiner2012). The IMV model specifies burdensomeness and belongingness as moderating factors (Fig. 2), however, its central premise is that suicidal ideation emerges from feelings of defeat (i.e. a perception of failed struggle and a feeling of powerlessness) from which one cannot escape (i.e. entrapment; defined as a feeling of being trapped by internal or external circumstances with the means of escape blocked) (O'Connor, Reference O'Connor2011; O'Connor & Kirtley, Reference O'Connor and Kirtley2018).

Fig. 1. The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (Joiner, Reference Joiner2005).

Fig. 2. The integrated motivational-volitional model of suicidal behaviour (O'Connor, Reference O'Connor2011; O'Connor & Kirtley, Reference O'Connor and Kirtley2018).

A growing body of research has tested components of the IPT and IMV models (Ma, Batterham, Calear, & Han, Reference Ma, Batterham, Calear and Han2016; O'Connor & Kirtley, Reference O'Connor and Kirtley2018). Specifically, a recent systematic review found that perceived burdensomeness had a consistent and strong association with suicidal ideation, whereas there was less evidence for the relationship between thwarted belongingness and suicidal ideation and few studies tested the interaction between the variables (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Batterham, Calear and Han2016). A further meta-analysis concluded that thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness had moderate direct effects in respect to suicidal ideation (r = 0.37, r = 0.48 respectively), and the associated interaction was relatively weak (r = 0.14) (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Buchman-Schmitt, Stanley, Hom, Tucker, Hagan and Joiner2017). Therefore, they called for more longitudinal studies to test this interaction over longer time periods (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Buchman-Schmitt, Stanley, Hom, Tucker, Hagan and Joiner2017; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Batterham, Calear and Han2016).

In another meta-analysis, both defeat and entrapment had a moderate to a strong association with suicidal ideation (r = 0.55, r = 0.62 respectively), although there was a dearth of prospective research (Siddaway, Taylor, Wood, & Schulz, Reference Siddaway, Taylor, Wood and Schulz2015). A number of studies also provide cross-sectional support for the mediating pathways proposed by the IMV model (e.g. Dhingra, Boduszek, & O'Connor, Reference Dhingra, Boduszek and O'Connor2016; Wetherall, Robb, & O'Connor, Reference Wetherall, Robb and O'Connor2018). Limited prospective evidence exists suggesting that both defeat (Taylor, Gooding, Wood, Johnson, & Tarrier, Reference Taylor, Gooding, Wood, Johnson and Tarrier2011) and entrapment (O'Connor, Smyth, Ferguson, Ryan, & Williams, Reference O'Connor, Smyth, Ferguson, Ryan and Williams2013) predicted suicidal ideation or behaviour over time, and a recent study found that entrapment mediated the relationship between defeat and suicidal ideation at 1-month (Branley-Bell et al., Reference Branley-Bell, O'Connor, Green, Ferguson, O'Carroll and O'Connor2019). Indeed, entrapment itself has two subscales; the entrapment may be internal (e.g. continuous self-critical rumination) or external (e.g. an abusive relationship) or both, and evidence suggests that internal rather than external entrapment mediates the relationship between defeat and suicidal ideation over 4-months in participants diagnosed with bipolar disorder (Owen, Dempsey, Jones, & Gooding, Reference Owen, Dempsey, Jones and Gooding2018). Additionally, there has been no evidence of the moderation of the IPT variables (perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness) on the relationship between entrapment and suicidal ideation, as suggested by the IMV model.

Current study

There is a growing body of evidence to support core aspects of both the IPT and IMV models in relation to suicidal outcomes (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Buchman-Schmitt, Stanley, Hom, Tucker, Hagan and Joiner2017; O'Connor & Portzky, Reference O'Connor and Portzky2018; Siddaway et al., Reference Siddaway, Taylor, Wood and Schulz2015), however, there is a dearth of prospective research investigating the key burdensomeness and belongingness interaction (IPT) and the defeat – entrapment pathway (IMV model), in particular with nationally representative samples. The importance of testing such relationships goes beyond theoretical curiosity; rather these findings are vitally important in order to inform the development of psychosocial interventions by providing targets for treatment. In this study, a representative sample of young people in Scotland was assessed twice, 1 year apart to test (i) the extent to which the key components of the IPT and the IMV model predict suicidal ideation over 12 months and (ii) to test the burdensomeness and belongingness interaction (IPT) and the defeat – entrapment pathway (IMV model) in the prediction of suicidal ideation at 12 months. Specifically, we hypothesised that (i) perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness would interact to predict suicidal ideation, (ii) entrapment would mediate the defeat to suicidal ideation pathway, with belongingness and burdensomeness moderating the entrapment to suicidal ideation pathway.

Method

Sample and procedure

The Scottish Wellbeing Study is a nationally representative study of young people aged 18–34 years (n = 3508) from across Scotland who were interviewed at baseline and completed a follow-up wave at 12 months (n = 2420). Baseline recruitment was conducted by a social research organization (Ipsos MORI), between 25 March 2013 and 12 December 2013. Participants were recruited using a quota sampling methodology, with quotas based upon age (three quota groups), sex, and working status (for more details, see O’ Connor et al., Reference O'Connor, Wetherall, Cleare, Eschle, Drummond, Ferguson and O'Carroll2018). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Participants completed an hour-long face-to-face interview in their homes, using Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI), with confidential completion of sensitive questions (including suicidal history) on a personal computer. Participants were compensated £25 for completing the baseline interview.

Participants who agreed were then contacted (via email, post or phone) after 12 months (Time 2) to complete a follow-up questionnaire (n = 2418 (71%) see online supplementary materials for attrition). They were offered £15 in shopping vouchers as compensation for their time (approximately 20 min), as well as being entered into a prize draw for an iPad mini as a further incentive to take part. Participants had the option to complete the follow-up via an online survey or by completing a postal booklet with freepost envelope. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the University of Stirling (Psychology Department) and University of Glasgow (Medical Veterinary & Life Sciences) ethics committees (approval number 200120068), as well as from the US Department of Defense Human Research Protections Office.

Some differences were found between the baseline characteristics of those who completed the follow-up and those who did not (see online Supplementary Table S1 in supplementary materials); those who did not complete the follow-up were slightly younger (t = −3.16, p < 0.01), more likely to be male (X 2 = 70.92, p < 0.001), not married (X 2 = 30.52, p < 0.001), and to score higher on perceived burdensomeness (t = 3.39, p < 0.001), thwarted belongingness (t = 3.25, p < 0.001) and suicidal ideation (t = 2.57, p < 0.01). These differences suggest selection bias within the data, which need to be taken into consideration when interpreting the results.

Measures

Baseline and 12-month follow-up

Suicidal ideation was assessed using the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSSI; Beck, Steer, and Ranieri, Reference Beck, Steer and Ranieri1988), which is a well-established scale measuring suicidal thinking over the preceding 7-days. The scale includes 21 items, with the first 19 assessing current suicidal ideation. The BSSI displayed good internal reliability at baseline (α = 0.86) and follow-up (α = 0.86).

Baseline only

Depressive symptoms were assessed via the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, Reference Beck, Steer and Brown1996), a well-established measure tapping a range of depressive symptoms. The measure contains 21 items, each with four options that reflect the severity of each of the symptoms, with higher scores indicating endorsement of more severe depressive symptoms. In this study, it displayed high internal reliability at baseline (α = 0.95).

Defeat and entrapment were measured via the Defeat Scale (Gilbert & Allan, Reference Gilbert and Allan1998) and Entrapment Scale (Gilbert & Allan, Reference Gilbert and Allan1998), respectively. Both scales have 16 items, with the defeat scale measuring a sense of failed struggle and loss of rank and the entrapment scale measuring a sense of being unable to escape feelings of defeat and rejection from both external and internal sources. In the present study, defeat (α = 0.96), external entrapment (α = 0.94), and internal entrapment (α = 0.95) demonstrated high internal consistency.

Perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness were assessed using the 12-item Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ; Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte and Joiner2012). The INQ includes seven-items to tap burdensomeness and five-items to assess belongingness. Both perceived burdensomeness (α = 0.88) and thwarted belongingness (α = 0.85) displayed good reliability.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were conducted using the statistical package SPSS version 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). With regard to missing data, this was examined scale by scale. A participant's data were used if they had completed 75% or more of a psychological scale. The 75% cut-off was agreed at a research group meeting as a reasonable cut-off for completeness of a measure as it would allow the inclusion of data from those who had missed one-quarter of the measure and had been used as a cut-off for other studies by this research group with little impact upon the findings (Wetherall et al., Reference Wetherall, Robb and O'Connor2018). There was therefore minimal missing data; less than 1% on any variable (range 0.31–0.86%). The distribution of missing data did not vary as a function of demographic characteristics (specifically age, gender and marital status), and expectation maximization (EM) was applied to replace missing items (<1%) for each scale. EM is an iterative method used to estimate the parameters of a statistical model and has been shown to be suitable for this type of missing data (Tsikriktsis, Reference Tsikriktsis2005). A sample of n = 2382 was included in the final analysis.

Partial correlation analyses, controlling for baseline suicidal ideation, was conducted to establish the relationship between each baseline variable with 12-month suicidal ideation, independent of baseline suicidal ideation. To establish the relative association between each variable and suicidal ideation at 12-months in multivariable analysis, a multiple linear regression was tested, with suicidal ideation entered as the outcome and all significant baseline study variables as predictors. To test the IPT interaction (i.e. moderation) and the IMV model pathway (i.e. moderated mediation), we employed the PROCESS macro (Hayes, Reference Hayes2013) for SPSS. This macro uses bootstrapped regressions to test mediation (mechanisms for the relationship) and moderation (variable affects the strength of the relationship) effects within models (including estimates of the indirect effects, direct effects and tests of simple slopes). A minimum of 10 000 bootstraps is used, to more accurately estimate the confidence intervals of the effects, yielding inferences that better reflect the irregularity of sampling design (Hayes, Reference Hayes2013).

Using the PROCESS macro, a moderation model was run to test the interaction between thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness in predicting 12-month suicidal ideation (IPT model). Moderated mediation models were run to test internal and external entrapment as the mediators in the relationship between defeat and 12-month suicidal ideation, and burdensomeness and belongingness as moderators of the entrapment to suicidal ideation pathway (IMV model). Baseline depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation were controlled for in the regressions of both models.

Results

Correlation analysis

The results of the correlation analyses (before and after controlling for baseline suicidal ideation) are included within the Supplementary materials (online Supplementary Table S2).

Predicting 12-months suicidal ideation

A multiple regression analysis including all baseline variables investigated which variables predicted 12-month suicidal ideation. The overall model was significant (F (9734, 7) = 139.65, p < 0.001, R 2 = 0.29), explaining nearly 30% of the variance in suicidal ideation at 12 months. As indicated in Model 1 (Table 1), baseline suicidal ideation (β = 0.43, s.e. = 0.03, CI 0.38–0.48, p < 0.001), perceived burdensomeness (β = 0.07, s.e. = 0.02, CI 0.04–0.10, p < 0.001), and internal entrapment (β = 0.07, s.e. = 0.02, CI 0.02–0.12, p < 0.01) were the only variables that predicted suicidal ideation at 12 months.

Table 1. Multiple linear regression models testing the extent to which baseline variables predict suicidal ideation at 12 months (n = 2382)

** p < 0.01 *** p < 0.001.

Testing the belongingness and burdensomeness interaction from the IPT

A moderation model tested the interaction between thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness to predict 12-month suicidal ideation. As indicated in Table 2, the interaction between thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness did not significantly predict 12-month suicidal ideation (β = −0.001, s.e. = 0.001, CI −0.004–0.002, p = 0.522). Baseline suicidal ideation (β = 0.45, s.e. = 0.03, CI 0.40–0.50, p < 0.001) and the main effect of perceived burdensomeness (β = 0.10, s.e. = 0.03, CI 0.05–0.15, p < 0.001) did predict 12-month suicidal ideation.

Table 2. Interaction of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness in predicting suicidal ideation at 12 months (n = 2385)

a Thwarted belongingness (TB) and perceived burdensomeness (PB) interaction term.

** p < 0.01 *** p < 0.001.

Testing the defeat–entrapment–suicidal ideation pathway from the IMV model of suicidal behaviour

As the multiple regression model found that internal, and not external, entrapment predicted suicidal ideation over time, internal entrapment was the variable included in subsequent mediation analysis. The first moderated mediation model tested thwarted belongingness as a moderator in the internal entrapment to suicidal ideation pathway. As illustrated in Fig. 3, defeat was positively associated with internal entrapment (β = 0.22, s.e. = 0.01, CI 0.21–0.24, p < 0.001). Internal entrapment was positively associated with 12-month suicidal ideation (β = 0.11, s.e. = 0.04, CI 0.04–0.18, p < 0.01), and the direct effect of defeat upon 12-month suicidal ideation was non-significant (β = 0.02, s.e. = 0.01, CI −0.002 to 0.04, p = 0.07). The interaction between internal entrapment and thwarted belongingness was not significant (β = −0.002, s.e. = 0.002, CI −0.005 to 0.002, p = 0.32). Additionally, baseline suicidal ideation (β = 0.46, s.e. = 0.03, CI 0.41–0.51, p < 0.001) significantly predicting 12-month suicidal ideation in the model, whereas the main effect of thwarted belongingness did not (β = 0.03, s.e. = 0.02, CI −0.0003 to 0.06, p = 0.053).

Fig. 3. Moderated mediation of internal entrapment and thwarted belongingness in the relationship between defeat and 12-month suicidal ideation (n = 2382). *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001; unstandardized beta values reported. Analysis controlling for baseline suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms. Indirect effect of internal entrapment when TB low = 0.023, s.e. = 0.01, CI 0.036–0.044, TB average = 0.022, s.e. = 0.009, CI 0.005–0.039, TB high = 0.018, s.e. = 0.007, CI 0.004–0.033; index of moderated mediation = −0.0004, s.e. = 0.001, CI −0.002 to 0.001.

The indirect effect of mediation indicates whether there was evidence of mediation, and is presented for each level of the moderator variable in Fig. 3 (1 s.d. ± mean). The bootstrapped confidence interval for the indirect effect of internal entrapment did not cross zero at any level of thwarted belongingness, suggesting that internal entrapment mediated the relationship of defeat with 12-month suicidal ideation, although there was no evidence of moderated mediation of thwarted belongingness.

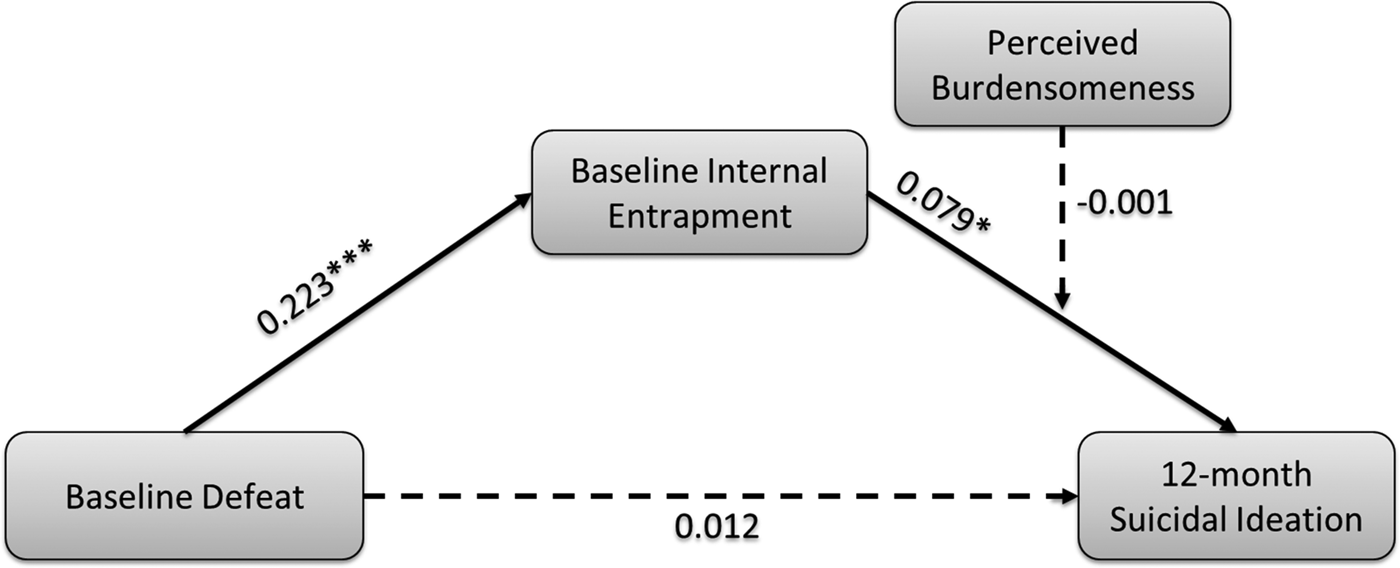

The second moderated mediation model tested perceived burdensomeness as a moderator in the internal entrapment to suicidal ideation pathway. As illustrated in Fig. 4, defeat was positively associated with internal entrapment (β = 0.22, s.e. = 0.01, CI 0.21–0.24, p < 0.001). Internal entrapment was positively associated with 12-month suicidal ideation (β = 0.08, s.e. = 0.04, CI 0.01–0.15, p < 0.05) and the direct effect of defeat upon 12-month suicidal ideation was non-significant (β = 0.01, s.e. = 0.01, CI −0.01 to 0.03, p = 0.26). The interaction between internal entrapment and perceived burdensomeness was not significant (β = −0.001, s.e. = 0.001, CI −0.003 to 0.002, p = 0.71). Again, baseline suicidal ideation (β = 0.44, s.e. = 0.03, CI 0.38–0.49, p < 0.001) and the main effect of perceived burdensomeness (β = 0.07, s.e. = 0.02, CI 0.04–0.11, p < 0.001) significantly predicted 12-month suicidal ideation in the model.

Fig. 4. Moderated mediation of internal entrapment and perceived burdensomeness in the relationship between defeat and 12-month suicidal ideation (n = 2382). *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001; unstandardized beta values reported. Analysis controlling for baseline suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms. Indirect effect of internal entrapment when PB low = 0.017, s.e. = 0.01, CI −0.003 to 0.036, PB average = 0.016, s.e. = 0.01, CI −0.001 to 0.034, PB high = 0.015, s.e. = 0.007, CI 0.001–0.029; index of moderated mediation = −0.0001, s.e. = 0.001, CI −0.001 to 0.001.

The indirect effect of mediation is presented for each level of the moderator variable in Fig. 4 (1 s.d. ± mean). The bootstrapped confidence interval for the indirect effect of internal entrapment did not cross zero when perceived burdensomeness was high, and crossed zero when perceived burdensomeness was low and average. This suggests that internal entrapment mediated the relationship of defeat with 12-month suicidal ideation, and although perceived burdensomeness did have a robust relationship with suicidal ideation, there was no statistical evidence of moderated mediation of perceived burdensomeness on the internal entrapment to suicidal ideation relationship.

Discussion

To reduce suicidal behaviour, it is necessary to target suicidal ideation, and as such, it is important to understand the conditions and pathways associated with its emergence. To this end, the current study advances our understanding of suicide risk by prospectively testing key predictions from two predominant models of suicide (O'Connor and Kirtley, Reference O'Connor and Kirtley2018; Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner2010). This paper aimed to investigate the extent to which the core factors from these models predicted suicidal ideation over 12 months and to test the burdensomeness and belongingness interaction (IPT) and the defeat – entrapment pathway (IMV model) in the prediction of suicidal ideation at 12 months. With the first aim, we found that two factors, perceived burdensomeness from the IPT and internal entrapment from the IMV model, predicted 12-month suicidal ideation, independently of baseline suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms. With the second aim, we found no evidence of an interaction between perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness in predicting suicidal ideation, and some evidence of internal, but not external, entrapment as a mediator of the defeat to suicidal ideation relationship.

As the interaction proposed by the IPT model of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness did not predict suicidal ideation at 12 months, this suggests that although there was support for the association between perceived burdensomeness and suicidal ideation over time, there was no evidence for the interaction or the independent effect of thwarted belongingness (except as a partial correlate) upon 12-month suicidal ideation. This is consistent with previous research (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Buchman-Schmitt, Stanley, Hom, Tucker, Hagan and Joiner2017), and suggests that perceiving oneself as a burden is sufficient to be associated with suicidal ideation, and this relationship is not conditional upon feeling a sense of thwarted belongingness. Indeed, Van Orden et al. (Reference Van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner2010) proposed that thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness alone are sufficient causes of passive suicidal ideation and that the simultaneous presence of both along with hopelessness about these states is required for active suicidal desire, with the hopelessness aspect not being measured in the current study. Therefore, although this does not support the proposed interaction, these findings do not entirely contradict the premises put forward by Van Orden and colleagues.

The role of internal entrapment was highlighted as it acted as a mediator of the relationship between defeat and suicidal ideation, whereas external entrapment was not significantly associated with suicidal ideation in multivariate analysis. This is partially consistent with the central pathway within the motivational phase of the IMV model, suggesting that defeat leads to entrapment and that entrapment is the proximal predictor of suicidal ideation (O'Connor, Reference O'Connor2011). The finding that external entrapment did not predict suicidal ideation highlights that feeling internally trapped by one's own thoughts, memories and feelings may be particularly pertinent in relation to suicidal ideation, rather than by constraints in our external environment. This fits with previous research (O'Connor & Portzky, Reference O'Connor and Portzky2018; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Fraser, Gotz, MacHale, Mackie, Masterton and O'Connor2010), including with a recent study which demonstrated that internal entrapment mediates the relationship between defeat and suicidal ideation in bipolar patients over a 4-month period (Owen et al., Reference Owen, Dempsey, Jones and Gooding2018). There was no evidence supporting the moderation of either thwarted belongingness or perceived burdensomeness on the entrapment to suicidal ideation pathway, which does not support their proposition as motivational moderators as presently specified within the IMV model.

As suggested by previous reviews of the IPT literature, perceived burdensomeness had a more robust relationship with suicidal ideation than thwarted belongingness (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Batterham, Calear and Han2016). Consequently, perceived burdensomeness could be a useful target for clinical intervention and for potentially identifying those at heightened risk of suicidal ideation. The importance of perceived burdensomeness in therapeutic settings is partially supported by findings from the treatment of anxiety, whereby levels of perceived burdensomeness predicted suicidal ideation during and post-treatment (Tobias Teismann, Forkmann, Rath, Glaesmer, and Margraf, Reference Teismann, Forkmann, Rath, Glaesmer and Margraf2016). Therefore, the development of therapeutic exercises targeting burdensomeness perceptions, or buffer their impact, is pertinent.

This study adds to the growing body of evidence highlighting a central role for entrapment within the suicidal process (O'Connor & Portzky, Reference O'Connor and Portzky2018). Specifically, the pervasive influence of internal entrapment in the development of suicidal ideation, which is consistent with previous findings (e.g. Owen et al., Reference Owen, Dempsey, Jones and Gooding2018). We propose that this reflects the extensive influence of internalising factors implicated in the suicidal process, such as rumination and self-critical thinking (Fazaa & Page, Reference Fazaa and Page2003; Miranda & Nolen-Hoeksema, Reference Miranda and Nolen-Hoeksema2007). Indeed, perceptions of entrapment have been shown to mediate the relationship between ruminative thinking and suicidal ideation (Teismann & Forkmann, Reference Teismann and Forkmann2017), suggesting that these internalising factors may culminate in feeling trapped by one's own thoughts. Additionally, anxiety sensitivity (a ‘fear of fear’) includes fears of the cognitive, physical, and social consequences of anxious arousal (Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Boffa, Rogers, Hom, Albanese, Chu and Joiner2018), with anxiety sensitivity cognitive concerns including the fear of not being able to control one's thoughts, which may overlap with internal entrapment, and has been successfully targeted in cognitive bias modification interventions to reduce suicidal ideation (Schmidt, Norr, Allan, Raines, & Capron, Reference Schmidt, Norr, Allan, Raines and Capron2017). Therefore, targeting these internalising thought processes in therapeutic settings is essential, specifically ones that may add to a sense of internal entrapment and having no escape from the negative thoughts in your own mind (O'Connor & Portzky, Reference O'Connor and Portzky2018; Sloman, Gilbert, & Hasey, Reference Sloman, Gilbert and Hasey2003). Such interventions may take the form of targeting coping abilities, with evidence that more positive trait factors such as hope and resilience may reduce the impact of perceptions of entrapment (Tucker, O'Connor, & Wingate, Reference Tucker, O'Connor and Wingate2016; Wetherall et al., Reference Wetherall, Robb and O'Connor2018).

Limitations and future research

Although this study had many strengths, there are a number of potential limitations. The measures were all self-report and may be subject to reporting bias. Indeed, there is evidence that suicidal ideation in particular can be under-reported (Mars et al., Reference Mars, Cornish, Heron, Boyd, Crane, Hawton and Gunnell2016). Additionally, the primary outcome was suicidal ideation as opposed to suicide attempts, as although these data were recorded in the present study the numbers were small and therefore lacked sufficient power for analysis. Indeed, despite having a large sample size, given that we were investigating residual changes in suicidal ideation across 12 months, it is unclear whether the study was sufficiently powered to detect the moderation effects. Around 29% of participants were lost to follow-up, and there was evidence of a self-selecting bias which constrains the generalizability of the findings. Indeed, those who did not complete the follow-up were higher on baseline suicidal ideation, and therefore the findings may not be representative of the more at-risk group within the sample. Although representative of the Scottish population, the sample was predominantly ethnically white (95%), and therefore the extent to which the IPT and IMV model components vary as a function of culture and ethnicity could not be investigated. Although missing data were minimal (>1% for each variable), there is some contention about how best to deal with missing data (Peeters, Zondervan-Zwijnenburg, Vink, & van de Schoot, Reference Peeters, Zondervan-Zwijnenburg, Vink and van de Schoot2015). Additionally, although the study was prospective in design, for the mediation analysis, defeat and entrapment were only measured at baseline; therefore, directionality between these variables cannot be assumed. Future research should measure these factors across different time points, or use daily diary methods such as Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA), to better understand how they interact and change over time. As suicidal ideation has been shown to fluctuate over days and hours (Kleiman et al., Reference Kleiman, Turner, Fedor, Beale, Huffman and Nock2017), so may feelings of burdensomeness and entrapment.

Conclusions

The current findings highlight the importance of targeting perceptions of burdensomeness and feelings of internal entrapment to reduce the likelihood that suicidal ideation emerges in at-risk individuals.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720005255

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Ipsos MORI, whose staff recruited the participants and conducted the interviews. This study was funded by a grant from US Department of Defense (W81XWH-12-1-0007). The funder had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of this article. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the funder.

Conflict of Interest

None.