Introduction

During the night of the April 22nd 2018 the steps of the Danish Ministry of Finance were covered with horse manure. Left, on top of the horse manure, was a note in where a group of public employees claimed responsibility. The note said that the cuts, orchestrated by the Ministry of Finance, ‘turned the public service into shit’ and they therefore returned the favour (TV2, 2019). Though an extreme version of it, this is an example of what the mainstay of many theories on the persistence of welfare states: that public sector employees will fight retrenchments (Downs, Reference Downs1967; Niskanen, Reference Niskanen1971; Dunleavy, Reference Dunleavy1980a, Reference Dunleavy1980b, Reference Dunleavy1986; Offe, Reference Offe1985; Knutsen, Reference Knutsen1986; Flora, Reference Flora1989; Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1994; Kenworthy, Reference Kenworthy2009). Pierson (Reference Pierson2001) even went as far as to argue that the large number of public employees in the Nordic countries is one of the key reasons for the support for the welfare state. Similarly, Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) argued that with the development of a service heavy public sector a new political conflict line would arise between those employed sectors that are exposed to globalisation of trade and those who are sheltered by the public employees.

Most articles that systematically study this premise have, however, not fared well. Most of the studies within this subfield have not found any meaningful difference between publicly and privately employed, and even there the effects were limited to specific countries and sectors of the publicly employed (Blais and Dion, Reference Blais and Dion1991; Garand et al., Reference Garand, Parkhurst and Seoud1991; Goul Andersen, Reference Goul Andersen1992; Svallfors, Reference Svallfors1997; Dolan, Reference Dolan2002; Rattsø and Sørensen, Reference Rattsø and Sørensen2016). This is quite surprising given the central role of this idea in the literature on support for the welfare state. Perhaps it was these discouraging results that led Pierson to conclude that ‘(…) the evidence that this political cleavage drives the politics of welfare state reform is, to be generous, extremely limited’ (Reference Pierson2001: 441). I, however, believe that the link between public employment and attitudes towards cuts in public spending can be strengthened by studying the impact of public employment at a household level. Having a spouse or cohabitee who works in the public sector might also affect attitudes towards spending and retrenchment. For instance, one could imagine that having a spouse who works in the public sector might affect the financial interests tied to spending on the public sector, but also whether the public sector and the work it provides is viewed in a positive or negative light. This could, potentially, expand the impact of public employment, as will be discussed in the next section. This idea has been proposed by Pierson (Reference Pierson2001), but has, as far as I can tell, never been tested anywhere.

This first section outlined the idea of the article. The next section will present a review of the literature on public employment, along with hypotheses based on the review. The third section presents the data used in the article and how the variables are structured. The fourth section presents the results of the article, and, in the fifth section, implications and limitations of the results are discussed.

Theoretical expectations and empirical finding

The theories on why public sector employees will resist cuts in public spending come in different forms, but draw on two fundamentally different logics. Some theories argue that the resistance against cuts among public sector employees is due to the self-interest of the public employees and thus that they fight cuts for their own benefit. Other theories argue that the resistance against cuts in public spending can be attributed to a certain set of values existing among public employees. Examples of both will be presented below.

One of the earliest examples of the self-interest argumentation is found in the public choice theories on bureaucracy. Here scholars argue that bureaucrats will seek to maximise the budget as this helps further career goals, generates higher salaries and creates opportunities for ‘slack’ in the organisation (Downs, Reference Downs1967; Niskanen, Reference Niskanen1971). The early versions of the self-interest argument thus offer very clear theoretical explanations, but also an argument that is very limited in scope, as they only describe the individual bureaucrat and organisation. Later studies also show that this model is largely unable to explain real bureaucrat behaviour (Arapis and Bowling, Reference Arapis and Bowling2020).

For this reason, the argument is more impactful when it is elevated to a societal level, as it was first in the literature on consumption cleavage. The theory was primarily championed by Dunleavy (Reference Dunleavy1979, Reference Dunleavy1980a, Reference Dunleavy1980b, Reference Dunleavy1986, Reference Dunleavy2014) who argues that the production of goods in the public sector tends to create support for the welfare state among those who produce and consume them. This will lead to changes in popular support for the welfare state, which will no longer rest on the traditional economic and ideological cleavage alone (that is, class voting), but also on the self-interest of those producing and consuming the public goods (for criticism see Franklin and Page, Reference Franklin and Page1984; Taylor-Gooby, Reference Taylor-Gooby1986). Dunleavy (Reference Dunleavy1986, Reference Dunleavy1980a, Reference Dunleavy1980b) argues that consumption cleavage will not undermine the class-based support for the welfare, but will in some instances run counter to it. An example of this could be the increasing number of white-collar employees in the public sector. Following class voting theory this group would tend to favour less government spending, in a trade-off for lower taxes, as they are better off than the average citizen. However, being employed in the public sector also creates vested interest in sustaining this spending and thus creates a pattern of support that potentially runs counter to the predictions of class voting theory (for empirical examples of the cleavages coexisting see Hoel and Knutsen, Reference Hoel and Knutsen1989; Svallfors, Reference Svallfors1995). Dunleavy (Reference Dunleavy1986), however, predicts that this will not lead to an ever-increasing push for public spending. This is because the beneficiaries of the consumption cleavage will mainly fight to preserve the goods that they have secured before perusing additional benefits, as well as being due to the support for public intervention in the marked economy having a cyclical nature (Downs, Reference Downs1972).

A very similar line of argumentation can be found in the theory of the welfare clientele. This theory was first developed by Offe (Reference Offe1985) and Flora (Reference Flora1989) and has later come to play a central role in Pierson’s (Reference Pierson1994, Reference Pierson1996) theory of the ‘new politics of the welfare state’. As the name indicates, the welfare clientele theory centres on the groups that are dependent on the welfare state – the public employees and the recipients of the social benefits and welfare services. According to Pierson (Reference Pierson1994, Reference Pierson1996) the welfare clientele makes retrenchments of welfare policies politically difficult because people generally are risk adverse, which means they will focus more on the concrete losses higher than on the potential gains. Following this logic, the concentrated losses of the members of the welfare clientele will lead them to electorally punish any politician who attempts to retrench the welfare state far more than the general population will reward them, as the gains, in the form of marginally lower taxes, are more dispersed. This asymmetry in the reactions to proposed retrenchments is the backbone of Pierson’s (Reference Pierson1994, Reference Pierson1996) argument, as politicians will seek to avoid the blame associated with retrenchment, and thus will only retrench welfare policies in infrequent situations where they can avoid or pass on the blame (Weaver, Reference Weaver1986).

The newest iteration of this argument is found in the literature on the public–private sector cleavage (Blais and Dion, Reference Blais and Dion1991; Garand et al., Reference Garand, Parkhurst and Seoud1991; Dolan, Reference Dolan2002; Tepe, Reference Tepe2012). The common thread in the studies is that there is not a focus on whether it benefits the individual public employee, but instead a general resistance of all retrenchment of social spending. An example of this is Wise and Szücs who argue that: ‘Government workers are assumed to be motivated by self-interest and personal gain and to favour political parties and public policies that would preserve or expand the public sector (…)’ (Reference Wise and Szücs1996: 44). This more general theory on the behaviour of the public employees predicts that they will tend to vote more often, to favour more Left-leaning parties, and to be more opposed to cuts in public spending, compared to those employed in the private sector (Bhatti and Hansen, Reference Bhatti and Hansen2013). Interestingly, then the differences between public and private sector employees tend to become smaller after retirement, as Rattsø and Sørensen (Reference Rattsø and Sørensen2016) show using a pooled series of Norwegian election survey. This would suggest that the differences between public and private sector employees are driven by self-interest.

Another dominant perspective, both in the literature on welfare state attitudes and the impact of public employment, is socialisation theories (Svallfors et al., Reference Svallfors, Kulin, Schnabel and Svallfors2012; Roosma et al., Reference Roosma, van Oorschot and Gelissen2014). In these studies the basic argument is that a specific set of values exist among public employees that might lead them to oppose cuts in public spending. As to the source of the differences in values between public and private sector employees some theories suggest that this might be created through the process of recruitment into the public sector (Knutsen, Reference Knutsen1986). This line of argumentation goes under the name of public service motivation. In this literature, a link between the values of public employees, or potential employees, and their sector of work is made (for an overview of the literature and results see Pedersen, Reference Pedersen2013). Other theories argue that the differences in values between public and private sector workers are more a product of socialisation in the public sector. Here the central theory is provided by Kitschelt (Reference Kitschelt1994), who argues that the work in the public sector might lead to changes in values and attitudes. This is due to the fact that many public sector employees come face to face with social problems and the recipients of social benefits and services, as well as other groups of public employees. Kitschelt (Reference Kitschelt1994) argues that these interactions can create egalitarian views, that support the view that public sector spending should not be cut, because they come to see the need of the individual recipients and recognise the role of other groups of public employees. Another theoretical argument in this vein is presented by Knutsen (Reference Knutsen1986, Reference Knutsen2005), who argues for the existence of a ‘public sector ideology’ that defines problems as a public matters and therefore resists cutbacks in social spending. Knutsen (Reference Knutsen2005) argues that this public sector ideology is created and reinforced partly in the educational institutions aimed at the public sector (e.g. education for social workers, nurses and care workers) and partly through the work in the public sector, as outlined by Kitschelt (Reference Kitschelt1994).

There thus seems to be ample theoretical backing for the idea that public employees should be more opposed to cuts in social spending than private sector employees. The studies based on these theoretical expectations have, however, had difficulties proving the connection true. I have only found two studies that systematically show the proposed connection. The first is by Wise and Szücs (Reference Wise and Szücs1996) and covers attitudes to welfare reforms in Sweden. This study shows that public employees are more opposed to public sector reform that would cut public spending. The second is Tepe’s (Reference Tepe2012) comparative study of eleven European countries, which found that employees in the public sector express more support for the government taking responsibility for a number of tasks. The effect in Tepe’s (Reference Tepe2012) study was, however, mostly limited to public employees in the health, education and service jobs. The other studies showed a very weak or no connection between the employment sector and spending attitudes (Blais and Dion, Reference Blais and Dion1991; Garand et al., Reference Garand, Parkhurst and Seoud1991; Goul Andersen, Reference Goul Andersen1992; Svallfors, Reference Svallfors1997; Dolan, Reference Dolan2002).

Hypotheses on the impact of public employment

Inspired by the theories outlined above, one expectation would be for simple self-interest to be one of the mechanisms driving the impact from public employment (Downs, Reference Downs1967; Niskanen Reference Niskanen1971). There should thus be an effect from public employment on the area within which the individual is employed: for example, nurses expressing more resistance against retrenching health-care spending. This simple self-interest version of the argument is the most straightforward application of the theory, but also very limited in scope. Further, if one accepts the predictions laid out by Pierson (Reference Pierson2001) in the theory of the ‘new politics of the welfare state’ the relatively small groups working within one field are thus nowhere near the thresholds that would scare off any retrenchment-eager politician.

In addition, the theories after Downs (Reference Downs1967) and Niskanen (Reference Niskanen1971) also seem to sketch out some general effects from public employment. Based on the theories outlined there might be an effect from public employment on retrenchment of all types of public spending. This idea is present in both the literature on public private cleavages, as exemplified in the quote from Wise and Szücs (Reference Wise and Szücs1996) above, and in the literature on public sector ideology. This is captured in the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Employees in the public sector will express more resistance against retrenchment of social spending than employees in the private sector.

If this ‘generalisation effect’ can be found, and if it is tied to self-interest as suggested in the literature review, then it should presumably be stronger for the types of public expenditures that actually generate and sustain jobs for the public employees (Dunleavy, Reference Dunleavy1986). In that sense all public expenditures are not created equal. The ‘in kind’ welfare services like healthcare, education, care for the elderly or children, and immigration services tend to be work intensive. This results in them generating more jobs, relative to the amount of public money spend, and therefore these kind of services should generate and sustain more jobs. On the other hand then paying out social benefits in cash should provide fewer jobs, relative to the total spending. Similar arguments have been presented by Knutsen (Reference Knutsen1995, Reference Knutsen2005, Reference Knutsen, Müller and Narud2013) in relation to voting, arguing that this effect should be stronger in the more service heavy welfare states. This is the basis for the second hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2: The impact of public employment on resistance against retrenchment of social spending will be stronger for welfare services than for social benefits.

Finally, I propose that the effect of public employment not only exists on an individual level, but also at a household level. The search for a ‘household effect’ of public employment is inspired by a debate between Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) and Pierson (Reference Pierson2001) on whether the public-private sectorial cleavage will be strongest or weakest in the social democratic Nordic countries. Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) argues that the public–private sectorial cleavage should be larger in the Nordic countries, because the comparatively more comprehensive welfare states require a larger tax base, which widens the cleavage between the public and private sector. Pierson, on the other hand, presents the contrary argument that the large welfare states can potentially blur the line between public and private sector and thus undermine the attitudinal cleavage between the sectors: ‘If a private sector worker is married to a public sector worker, (…) then what is the likely alliance pattern?’ (Reference Pierson2001, 211) Based on this, the third hypothesis of a household effect is outlined below:

Hypothesis 3: There is a household effect on attitudes towards retrenchment of social spending.

The impact of public employment will be strongest for individuals employed in the public sector, who have a spouse or cohabitant that is employed in the public sector. Conversely, it should be weakest for individuals employed in the private sector that have a spouse or cohabitant who is employed in the private sector. In the case of households that rely both on the public and private sector, and thus are mixed-income households, they should fall in between the purely public and private households. This of course assumes that there is not a level of self-selection where a person with more government-friendly attitudes is more likely to date a civil servant. However, it seems highly unlikely that this should be a deciding factor in the dating market.

Data, variables and methods

To answer the questions posed above I will use the ‘Attitudes to Welfare’ survey. The survey was collected in Denmark during 2008, by the National Agency for Welfare State Research (SFI). The sample was drawn randomly from the Danish administrative registers, among all people living in Denmark who at the time were eighteen years or older. The initial sample contained 3000 respondents who received the questionnaire by mail. Those who did not answer the survey in the first round were later contacted via phone to complete the survey. Of the 3000 respondents 1447 provided questionnaires that were considered complete, meaning that they filled out most or all of the questions. This resulted in a response rate of 48 per cent. All completed questionnaires were validated by comparing the age and gender in the questionnaire against the age and gender in the registers. I did not take part in designing or collecting the survey, so this can be considered a secondary analysis.

Variables

This survey is uniquely well suited to answer the questions posed in the article as it contains detailed questions on sectorial employment of both the respondent and their spouse (if they have one), along with questions on attitudes to public spending on a number of policy areas. Of course, selecting Denmark also means selecting one of the countries that has the highest level of public employment, mainly due to the public sector providing more welfare services than in other countries (Castles, Reference Castles2008). Furthermore, the Danish welfare state, or at least the service sector, has been termed as ‘universalistic’, which tends to gather further support (Edlund, Reference Edlund and Svallfors2007; Hedegaard, Reference Hedegaard2014). Therefore, I am looking for the effects of public employment on attitudes in one of the most likely of places and I should therefore be cautious when extrapolating the results from this ‘best case’.

The employment sector is, for the reasons outlined above, measured at a household level. The employment sector has therefore been divided into four groups. The first is the group of respondents who are employed in the public sector, and if they have a spouse or cohabitee this person is also employed in the public sector. Next are the respondents from mixed-income households. The respondents from the mixed-income households will be divided into a group where the respondent is employed in the public sector and a group where the respondent is employed in the private sector. This subdivision is created to test whether there is an impact of having a spouse or cohabiting partner employed in the public sector while being employed in the private sector. These groups are measured up against the entirely private households: that is, where the respondent is employed in the private sector, and if they have a partner, this person is employed in the private sector.

Other studies, especially within the field of policy feedback, has constructed similar measures of household interest or proximity to a policy (Campbell, Reference Campbell2012). Examples of this are Larsen (Reference Larsen2017) who shows that being related to a student makes people more critical of education reform and Hedegaard (Reference Hedegaard2014) who shows that being more proximate to the recipient of benefit makes respondents less willing to retrench the benefit. This variable is, however, limited to the respondents who are employed at the time of the survey. On the one hand, this limits the scope of the survey. On the other hand, this also ensures that large parts of the recipient side of the ‘welfare clientele’ (for example, the unemployed, pensioners, and students) are removed from the study. Therefore if I find any effect this is not a general ‘welfare clientele’ effect (Offe, Reference Offe1996; Rattsø and Sørensen, Reference Rattsø and Sørensen2016), but an effect of public employment specifically.

The dependent variables are attitudes to spending on ten areas of the welfare state. This is measured using the following question: ‘Now we would like to ask about your opinion about public expenses in a number of areas (…)’. Respondents could answer on a five point scale from ‘spend much less’ (1) to ‘spend much more’. Using this I will examine the attitudes to five areas of welfare services (healthcare, education, childcare, elderly care and integration of immigrants) and the five most common social benefits (unemployment benefit, social assistance, state pension, incapacity benefit and the education grant). I included these as they represent some of the main areas of public spending and therefore some of the potential fault lines in public debates. By using this measure I capture the attitudes to the patchwork of policies that combined make up the welfare state, but not the overall attitudes to the welfare state. I, however, believe that measuring at this ‘policy level’ better captures the ambivalent and complex attitudes people hold regarding the welfare state. Support in one area is not necessarily translated in to support for another area of the welfare state (Hedegaard, Reference Hedegaard2015). Don’t know, invalid or non-responses are not included for these or any other variables.

A number other of variables were also included to eliminate some of the differences between public and private sector employees, which could potentially account for the differences between the groups. The effect of education is included as there might be differences in the levels of education as this has previously been shown to have a strong impact on the support for spending (Edlund, Reference Edlund and Svallfors2007). This is included as a categorical measure that compares those with longer higher educations (mostly university degrees), against medium higher education (three to four years), short higher education (up to three years), vocational training and no education. In addition I have also controlled for sex, as women are more employed in the public sector, especially in the more service heavy Nordic welfare states, and women are generally found to be more pro-welfare than men (Korpi et al., Reference Korpi, Ferrarini and Englund2013). Age is also included, as this sometimes has an impact on attitudes, especially on the age-dependent welfare spending categories like pensions (Busemeyer et al., Reference Busemeyer, Goerres and Weschle2009). Finally, I have controlled for household income as it can be imagined that there are some differences in income between the public and private sector and income differences have been shown to impact attitudes towards welfare spending (Taber, Reference Taber, Sears, Huddy and Jervis2003). I have chosen not to control for the effect of political ideology as this would potentially control away some of the differences in values the theories predict should be present.

Methods

The analyses will be presented in two steps. First, I will present a figure showing the distribution of the main independent variable on household employment. Second, I will show the impact of this variable on attitudes to ten policy areas. This will be controlled for sex, age, education and household income, to account for the differences between the types of household. In this second step, I will use linear ordinary least square (OLS) regression models. I will use unstandardised regressions, as I mainly am interested in the effect of public employment and therefore want to see the size of this effect. I have opted for this method over, for instance, multinomial logistic regression because OLS regressions are comparable between the models, while logistic regressions are not (Mood, Reference Mood2010). The main argument against this choice is that the dependent variables are not formally on an interval scale. However, the residuals are normally distributed (not shown), so there should not be any issues with using this method.

Household effects of public employment

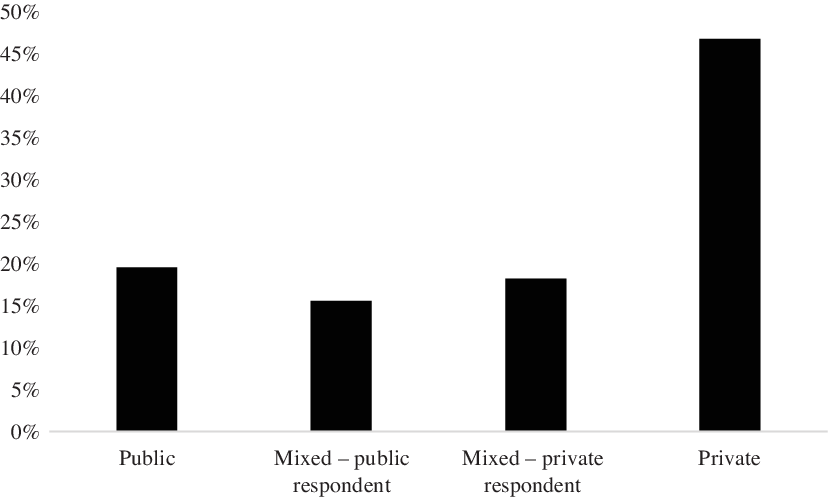

The ‘Attitudes to Welfare’ survey, and the measure of household employment constructed above, allows me to describe how the workforce is composed in Denmark, when viewing it from a household perspective. Figure 1 shows a simple representation of the respondents, when viewing them from a household perspective.

Figure 1. Household composition by sectorial employment.

Figure 1 shows that 20 per cent of the respondents are in a ‘purely’ public household where, if the person has a spouse or cohabitant, this person is also employed in the public sector, and 47 per cent are living in an entirely private household. Finally, 34 per cent are living in what I have called ‘mixed’ households, that rely on both the public and the private sector for income. These 34 per cent are divided about evenly between respondents employed in the public sector (16 per cent of the total) and respondents employed in the private sector (18 per cent of the total). Combined, a little more than half the working households are at least partially dependent on the public sector.

In accordance with Pierson’s (Reference Pierson2001) predictions, I do find a strong gender divide in the sectorial employment (not shown in the figure). In the public income households, 65 per cent of respondents are female. In the mixed-income families with a public respondent 85 per cent are female; conversely, of the privately employed respondents in mixed-income families 83 per cent are male. In the private households, there is a slight majority of 54 per cent males. The gendered sectorial differences are really interesting, as they highlight how sectorial differences might be a diving line in the views on the welfare state. On the other hand, the ‘intermingling’ of the publicly employed, who are predominantly women, and the privately employed, who are predominantly men, might also blur this line.

This is what I will test next. Using a series of OLS regressions compared I will show the effect of sectorial employment on attitudes to ten welfare policies. The support for spending on the policy areas is measured on a five point scale from ‘spend much less’ to ‘spend much more’. In addition, I also control for sex, age, type of education, and household income to capture some of the compositional differences between the public, mixed and private households.

Table 1 shows the differences in the impact of household employment on spending on the five welfare services healthcare, education, childcare, elderly care and integration services aimed at immigrants. For four of the five welfare services – healthcare, education, childcare and elderly care – I see almost no effect of the household employment. For these four areas I only see an effect of household employment when comparing the entirely private households to the mixed households with a private respondent (0,31***). However, when looking at integration services aimed at immigrants I see much more of a difference. Here both the public (0,40***) and mixed households (0,32*** and 0,33*** for respectively public and private respondents) differ significantly from the private households. The mostly absent effect of household employment is surprising, given that this is exactly the types of policies that should generate jobs in the public sector and thus benefit the group. One explanation of this could be that the welfare services experience widespread popularity in the population. This can be seen in the constants, which express the mean score on the dependent variables across all respondents. Here I see that average score is almost four on the five point scale, for healthcare, education and childcare, meaning that there is little support for cutting these welfare services and no real differences between the groups.

Table 1 OLS regressions showing the effect of household employment on attitudes to whether less (1) or more (5) should be spent on five welfare services. The effects are shown as unstandardised coefficients, with significance levels reported

Notes: All effects are controlled for gender, age, education and income. Ref = reference category, * p > 0.05, ** = p > 0.01, *** = p > 0.01.

For the other variables I find that gender has a little impact on attitudes to healthcare (0,32***) and elderly care (0,21***), but surprisingly not childcare. Age has an expected impact, as the young are more willing to spend on childcare, while the older are more willing to spend on elderly care. This trade-off between services and social investment is well known from other studies (Busemeyer et al., Reference Busemeyer, Goerres and Weschle2009). Finally, I see that income has little impact on attitudes, while education mostly matters for attitudes to elderly care.

Table 2 shows the attitudes to spending on the five social benefits: unemployment benefit, social assistance, state pension, incapacity benefit and education grant. For these five policies I find an impact of public employment on attitudes to unemployment benefit, social assistance and the education grant. Here an effect exists across the different types of mixed households, when comparing against the entirely privately employed households. For unemployment benefit and social assistance, I find that the size of the effect is almost equal in size for all group of public and mixed household (between 0,22* and 0,25**). The effect is in all cases around a quarter of a point on the five point scale. For the education grant I find similar effect sizes for both of the mixed households, but not for when comparing the public households. However, for the state pension and incapacity benefit there is no difference between the different types of households. Again, this fits the pattern above of the most popular benefits and services generating the least difference in spending preferences, as shown by the constants. This does not fit the self-interest interpretations presented above, as social benefits do not generate many jobs. Further, finding the strongest effect among the policies on unemployment benefits is counter-intuitive in a self-interest argumentation, as public employees are less prone to unemployment than private sector employees in many Western countries (Clark and Postel-Vinay, Reference Clark and Postel-Vinay2009).

Table 2 OLS regressions showing the effect of household employment on attitudes to whether less (1) or more (5) should be spent in of five social benefits. The effects are shown as unstandardised coefficients, with significance levels reported.

Notes: All effects are controlled for gender, age, education and income. Ref = reference category, * p > 0.05, ** = p > 0.01, *** = p > 0.01.

The impact of the control variables is a bit different for the social benefits. Gender again has a small impact, this time for social assistance (0,15*) and incapacity benefit (0,19*), with the men being slightly more pro-spending. Age matters for all the social benefits, with the older being more willing to spend on the old, even for the education grant. However, the students are not included here and neither are the pensioners, so the implications of this are limited to the working population. Education matters in expected ways, in that the lower educated are more willing to spend on social benefits. This is especially the case for the state pension and incapacity benefit, which tends to benefit these groups more. Finally, the impact of income follows the expected pattern of lower income groups being more willing to spend than higher income groups.

To recapitulate on the hypotheses I do, partially, find that there is a difference between public and private households as predicted by hypothesis 1 and 3. This effect was present for welfare services related to integration, unemployment benefit, social assistance and the state education grant. However, the impact of public employment did not differ between welfare services and benefits as predicted in hypothesis 2. It does not seem that households that are dependent on the public sector support welfare services that provide more jobs than social benefits. Instead, the cleavage was the most distinct for policies that were the least popular and therefore potentially more at risk for experiencing cuts in funding.

Conclusion

This article examined the link between public employment and resistance against retrenchment of social spending. The idea that public employees stand united against cutbacks in public spending is a mainstay within a wide range of theories of welfare state attitudes and welfare state development. The empirical results have, however, not been convincing of the fact that this political cleavage exists.

This article studied the link from a household perspective instead of from an individual level perspective. This means including whether the spouse or partner, assuming the person has one, is employed in the public or private sector. The article shows that when using this approach the link between public employment and attitudes towards retrenchment of welfare policies can be established for some welfare policies, but not for all. Importantly, the article shows that this feature of public employment can be extended to mixed-income families: that is, families where one member of the household is employed in the public sector. It was assumed that this effect would be stronger for social services than for benefits, as services tend to create more public jobs. However, the results do not confirm this, as the impact of public employment did not differ between welfare services and benefits in that manner. Instead, the cleavage was the most distinct for policies that were the least popular and thus the most at risk for retrenchment. The results of the article thus partially seem to confirm the overall idea of the literature within the field, that public employees do oppose retrenchment of social spending, more than private sector employees. The findings do, however, question whether self-interest is the main driver behind this effect, as the results in several instances did not fit a self-interest pattern. Therefore, the literature might have to lean more heavily on the values-based and socialisation explanations in order to explain the phenomenon.

A final thing to consider is the context. This analysis is based on a survey from Denmark. As described in the data, variables and methods section, this might be the ‘best case’ for finding this effect, as a service heavy social democratic welfare state has ensured a relatively large degree of public employees, compared to other countries. Further, other factors such as low perceived corruption in the public sector and high trust in the public sector and other people might also strengthen this relationship (Anderson and Tverdova, Reference Anderson and Tverdova2003; Hedegaard, Reference Hedegaard2018). Therefore, the mechanisms might be generalisable, but these effects and their size have to be studied in other countries and contexts.