INTRODUCTION: THE TLACUILO AND THE PAINTER

In Mexico City, perhaps in the 1540s, an Aztec painter depicted two men gathered around the very act that occupied him: the creation of a painted manuscript (fig. 1).Footnote 1 He unmistakably identified the men as indigenous. Each wears a simple white tilmatli (cape or cloak), tied with a knot over one shoulder. Their ethnicity is also indicated by their bare feet, lack of facial hair—as Spaniards were regularly portrayed with the short, pointy beards fashionable at the time—and straight black hair cut in a bob below the ears, all visual markers of indigeneity in pictorial sources of the time. The man on the left sits on a reed mat (petatl), indicating his seniority or higher status. He is an indigenous tlacuilo (pl. tlacuiloque), a Nahuatl word that modern scholars often translate as “artist-scribe” or “painter-scribe” to capture the dual nature of Mesoamerican pictorial script. He holds in his right hand a reed pen and in his left hand the square surface that he is painting, the shape and scale of which suggest a pre-Hispanic indigenous screenfold manuscript comparable to surviving examples such as the codices in the Borgia group, the Codex Bodley, or the Codex Zouche-Nuttall (fig. 2).Footnote 2

Figure 1. Aztec tlacuilo (painter-scribe) at work in preconquest times, from the Codex Mendoza, ca. 1540s. Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, MS Arch. Selden A. 1, fol. 70r (detail).

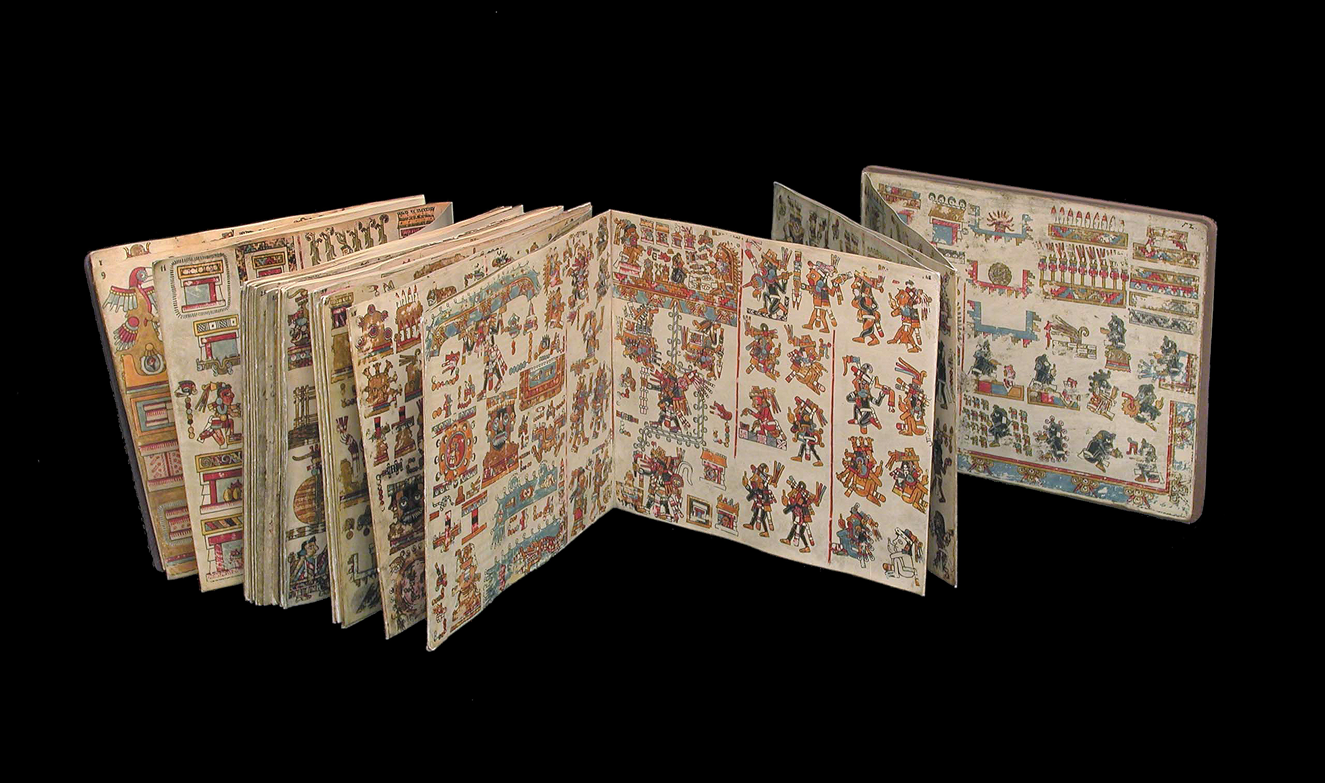

Figure 2. Screenfold format used in pre-Hispanic codices. Photograph of the facsimile edition of the Codex Vienna: Otto Adelhofer, ed., Codex Vindobonensis Mexicanus 1 (Graz: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, 1974). Image © Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

The tlacuilo depicted in this painting has traced a square frame and within it painted two large volutes (comma shapes) originating diagonally from opposite corners. This design, known as ihuitl (feather or small feather), had great meaning in Mesoamerican visual culture, where it could represent “the days of the ritual calendar and their prophetic forces—the days and the fates attached to them.”Footnote 3 The symbol's significance is heightened by the choice to paint it in black and red, a concrete representation of the diphrasis “in tlilli, in tlapalli” (“the black ink, the red ink” or “the black ink, the colors”), which the Nahuas used to refer to pictorial writing, to painted books more generally, and, more broadly still, to knowledge or wisdom.Footnote 4 The paired figures on the painted document are echoed by the small volutes that emerge from the men's mouths, unfurling toward each other. These are the Nahua glyphs for speech, illuminated in the vivid turquoise used to denote something particularly valuable or precious.Footnote 5 They indicate that the two men are engaged in conversation. What they discuss is picture making itself: this is an art lesson, with the father training his apprenticing son in the art of painting indigenous books.Footnote 6

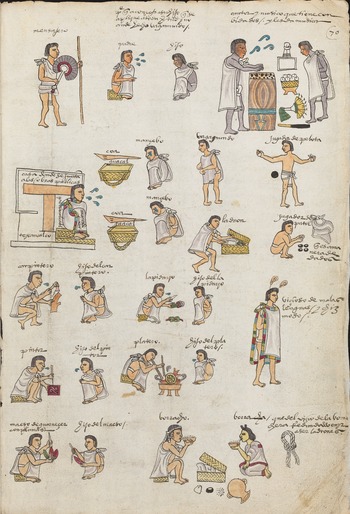

This vignette appears on the penultimate painted page of a document known as the Codex Mendoza, one of the most important sixteenth-century Mexican codices.Footnote 7 It is one of several scenes of indigenous male artisans educating their sons in the trade they practice (fig. 3). Written glosses in Spanish identify each figure. The tlacuilo and his son are labeled with the Spanish terms pintor and hijo del pintor (painter; son of the painter). Other figures in the bottom half of the page include a carpenter (carpintero), a stoneworker (lapidario), a silversmith (platero), and a featherworker (amanteca) glossed as “master of adorning with feathers.” The top half of the page features other types, among them a messenger (mensajero), a singer (cantor) playing a large drum, a ball player (jugador de pelota), and a “player of patol, which is like dice.”Footnote 8 Through the images, the manuscript provides a view of selected aspects of Aztec society; through the written glosses, it gives Spanish translations—linguistic and cultural—that make the figures legible to viewers unfamiliar with indigenous society.

Figure 3. Various occupations in Aztec preconquest society, in the Codex Mendoza, ca. 1540s. Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, MS Arch. Selden A. 1, fol. 70r.

The indigenous painter who crafted these figures did not depict scenes from contemporary life. Rather, he presented the trades and traditions of the pre-Hispanic past, a world of artistic practices, technologies, and social and cultural meanings that had undergone drastic transformations since the arrival of Spaniards to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, in 1519, and the fall of the Aztec Empire two years later. Indigenous experts who worked with paint, wood, stone, metal, and feathers continued to thrive in the colonial world, transforming their practices in response to changed political, social, and cultural circumstances. They combined old and new materials, techniques, formats, and iconographies. The tlacuilo shown in the Codex Mendoza exists at an unspecified time previous to the Spanish incursion and creates a pre-Hispanic screenfold manuscript. The Nahuas called this type of object amoxtli, a term that literally means “glued sheets of [amatl] paper,” as it is composed of the roots amatl (paper made from the bark of a native fig, the amaquahuitl, or paper tree) and axtli (glue).Footnote 9Amoxtli thus refers to the support and the format rather than to the inscriptions on it. Sixteenth-century Spanish sources, however, without exception translate amoxtli as “book” (libro), an interpretation that is both linguistic and conceptual, as the category amoxtli is analogous but not equivalent to the category book. While the tlacuilo shown painting an amoxtli inhabits an indigenous world devoid of Europeans, the pintor who crafted this image lived in a colonial society and contributed to the production of a Western-style manuscript book. He used both native and European materials and elements, anticipating in his work Spanish interventions—most notably the written word—as well as Spanish viewers. This is decidedly not a self-portrait: he was a pintor, not a tlacuilo. The new self painted the old self.Footnote 10

The Spanish labels annotating the figures, however, both suggest and negate this transformation. Although the presence of alphabetic writing is a conspicuous sign of the colonial context, the written inscriptions characterize the pre-Hispanic characters not as tlacuiloque but as painters, using a Spanish category that had not existed for them and that elides the enormous changes that took place following the conquest. The written words translate indigenous practices, techniques, materials, and meanings into colonial ones. While such translation made pre-Hispanic categories visible and legible in postconquest New Spain, it also fundamentally altered indigenous practices, categories, ontologies, and epistemologies. Translation both conveyed and transformed.

In this essay, I propose a new approach to the celebrated Codex Mendoza. Studies of colonial Latin American art and culture revolved for many decades around discussions of hybridity, often with the goal of rescuing forms that had previously been derided as poor copies or imitations of superior European originals. Scholars carefully untangled and parsed the intertwined strands of bicultural objects and forms, celebrating them as new hybrid or mestizo mixtures that emerged out of two separate and distinct cultures. The concept of hybridity, however, carries so many problems that it can obscure more than it illuminates.Footnote 11 More recently, scholars have turned to a focus on processes of mediation, transculturation, and translation.Footnote 12 Alejandra Russo has argued that the production of images and objects in postconquest New Spain depended on a two-way translation whose operation and results always remained visible, yielding objects that are at once translated and untranslatable. The new form always contains the echo of the old form, signaling at once its conversion and the impossibility of that conversion.Footnote 13

Building on such scholarship and on approaches from the history of science and the history of the book, I use the Mendoza to analyze the creation of transcultural objects and the production of knowledge in early colonial Mexico. How did indigenous and Spanish participants coproduce new objects and new interpretations? How were indigenous practices and concepts translated into colonial categories, by both natives and Europeans? What were the implications of such translations—of transmuting indigenous pictorial script into Western painting, of rethinking the tlacuilo as a pintor? How did images operate as knowledge forms in this context? I consider the codex not as a depository of information but as a site of cultural negotiation and mediation; not as a collection of indigenous raw data that can be mined for information about the Aztec world but as an already interpreted series of statements that can be analyzed for insights into the colonial world. I focus my analysis on process, examining the sequence of steps through which indigenous and Spanish painters, speakers, interpreters, and scribes related images and words to coproduce legible and credible statements. Rather than studying the manuscript as a finished work, reading its pages sequentially, from first to last, I begin with the blank page and follow the various actions and layered traces that yielded the document. Given that the images were created by indigenous painters and the text penned by a Spanish scribe, the focus on process illuminates the negotiation of visual and textual elements in the production of knowledge, and the ways in which natives and Spaniards made sense of Aztec history and culture in the decades immediately following the conquest. Both indigenous and Spanish individuals produced meaning, for and in response to each other. As a result of this process, native practices and categories were recast as colonial ones: native tlacuilolli (pictorial writing) became colonial pintura (painting); the image maker of the indigenous pre-Hispanic past (tlacuilo) was recast in the postconquest present as a painter (pintor). Such reinvention of indigenous traces and practices resulted from multiple acts of translation and interpretation, with profound ontological and epistemological implications.

READING FOR CONTENT: MAKING AZTECS LEGIBLE

The Codex Mendoza is a pictorial manuscript in the format of a European-style book created in Mexico City not long after the Spanish conquest. It is composed of seventy-one folios of European paper, folded and cut to form quarto pages measuring roughly 30 x 21 centimeters (12 x 8 ¼ inches). Of the total 142 pages, 73 are primarily pictorial and 63 are textual. Seven were left blank, for unknown reasons. The juxtaposition of pictorial and textual material is a result of the work's coproduction by indigenous and Spanish makers: native painters created the images; a Spanish scribe wrote the Spanish-language text and annotated the images with textual glosses. However, the names of the painters, scribe, or patron are not inscribed in the manuscript, which does not include a title, date, title page, or frontispiece.Footnote 14

Scholars have long attempted to establish the identity of the document's makers and patron, as well as the date when it was created. Between the mid-sixteenth and late eighteenth centuries the manuscript remained unnamed despite being well known and much studied. For almost two and a half centuries, authors described it as a “Mexican history in pictures” (or similar phrases).Footnote 15 In 1780 the Mexican Jesuit Francisco Javier Clavijero (1731–87) first linked the document to the illustrious first viceroy of New Spain, Antonio de Mendoza (1495–1552; r. 1535–50), referring to it as “la raccolta di Mendoza” (“Mendoza's collection”).Footnote 16 That attribution was repeated in 1813 by the renowned traveler and scholar Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), cementing the connection to Mendoza.Footnote 17 In the late 1930s and early 1940s, historians Silvio Zavala and Federico Gómez de Orozco used archival documents to support the idea that Mendoza commissioned the manuscript. They suggested that the codex was created around 1541 by Francisco Gualpuyogualcal (dates unknown), an indigenous “master of the painters,” who worked in collaboration with the author of the Spanish text, “a modest and virtuous canon of Mexico called Juan González.”Footnote 18 Although the Zavala–Gómez de Orozco hypothesis was widely accepted, I find these claims inconclusive. I share the doubts regarding authorship expressed in 1992 by Henry Nicholson and more recently by Jorge Gómez Tejada. Also in question is the manuscript's dating: Gómez Tejada has proposed it may have been created ca. 1547–52; analyses conducted by Davide Domenici and collaborators, while not definitive, extend the possible dates of manufacture from the 1530s to the 1560s.Footnote 19

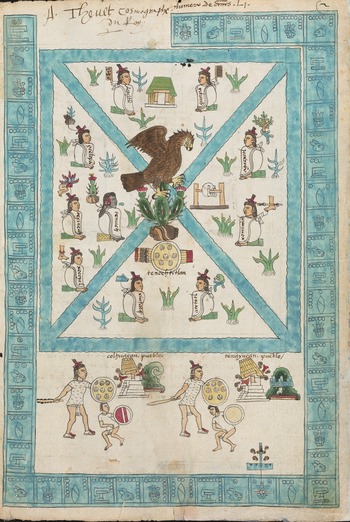

The manuscript is organized in three thematically distinct sections, clearly identified at their openings and closings through inscriptions written in a different handwriting from that used throughout the manuscript, which could indicate the presence of another scribe and, perhaps, the insertion of these minimal paratextual elements at a point following the composition of the majority of the written work.Footnote 20 The first section occupies a total of sixteen folios, representing roughly a fourth of the manuscript. It charts the military history of the Mexica (Aztecs) from the founding of the city of Tenochtitlan in 1325 (year Two House in the Aztec calendar) (fig. 4) to the end of the reign of Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin (Motecuhzoma II, ca. 1466–1520; r. 1502–20).Footnote 21 History is organized as a sequence of emperors (huey tlatoque, sing. huey tlatoani), the years they governed, and the communities (altepeme, sing. altepetl) they rendered tributaries through military conquest. The second section of the manuscript presents economic information: the taxes that various communities paid to Tenochtitlan, specifying both objects and quantities (fig. 5).Footnote 22 This is the longest of the three parts of the book, extending over thirty-nine folios—almost exactly twice as long as the first section and almost 60 percent of the entire manuscript.Footnote 23 The third and final section, like the first one, occupies sixteen folios. It provides a detailed account of Aztec life and customs from birth to old age, describing such aspects as the upbringing of boys and girls until they turned fifteen, when girls would marry and boys would enter a trade or attend specialized academies (fig. 6); various occupations, with depictions of military orders and their uniforms; and practices of governance and the justice system.Footnote 24 It thus provides a unique glimpse of precontact “private and public rites from the grave of the womb to the womb of the grave”—to use the evocative words of a seventeenth-century commentator—at a time when they were being dramatically transformed under Spanish rule.Footnote 25 These three parts represent both continuity and transformation. The first section relates to a standard Mesoamerican genre of dynastic history; the second is closely connected to a surviving Aztec document, the Matrícula de tributos; and the third is not related to any known precedents and likely represents an innovation.Footnote 26

Figure 4. The foundation of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, in 1325 (year Two House), painted as a depiction of historical events and geographic place, in the Codex Mendoza, ca. 1540s. Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, MS Arch. Selden A. 1, fol. 2r.

Figure 5. Taxes paid to Tenochtitlan by eight towns in the province of Xoconochco, including strings of fine green stones (chalchihuitl), bundles of rich feathers of different colors, bird skins, loads of cacao, gourds for drinking cacao, two large pieces of clear amber decorated with gold, and jaguar skins (mistranslated as “tiger skins”), in the Codex Mendoza, ca. 1540s. Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, MS Arch. Selden A. 1, fol. 47r.

Figure 6. Wedding ceremony (bottom) and the education of young men at specialized schools for religious and military leaders called calmecac and cuicacalli (house of song), in the Codex Mendoza, ca. 1540s. Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, MS Arch. Selden A. 1, fol. 61r.

Although the Codex Mendoza was produced with a Spanish audience in mind, its circulation was much wider than its creators could have anticipated.Footnote 27 The manuscript ended up not in Spain but in Paris, later traveled to London, and eventually made its way to the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford, where it remains to this day. This trajectory placed it in the hands of important authors and collectors, all of whom were connected to French or English interests in the Americas and beyond: André Thevet (1516–90), Richard Hakluyt (ca. 1552–1616), Samuel Purchas (ca. 1577–1626), and John Selden (1584–1654). The codex also circulated in printed versions. In 1625, Purchas published a fifty-two-page chapter reproducing almost the entire pictorial content of the Mendoza as well as an English translation of the Spanish text, with additional commentary. This is the longest and most heavily illustrated chapter of Purchas's four-volume, widely read Hakluytus posthumus or Purchas his pilgrimes.Footnote 28 Using Purchas's chapter—rather than the original manuscript—as a source, no fewer than seven other titles in ten different editions reproduced portions of the material over the next two centuries. Thanks to Purchas, the Mendoza was the most reproduced and analyzed Mexican object in early modern Western publications. It may well be the non-European object most studied by Europeans before the nineteenth century. It was, without question, the most significant source for the study of the Mexica for centuries, and the object of a remarkable and sustained degree of attention from the sixteenth century to the present.Footnote 29

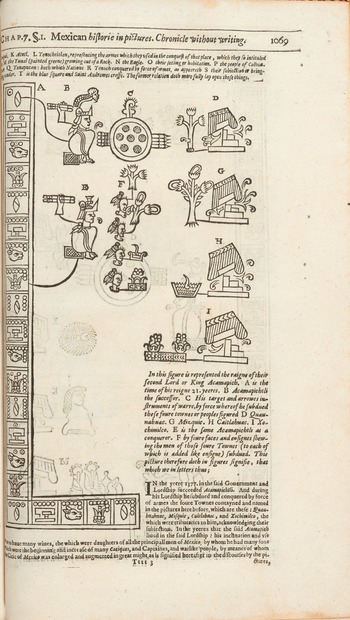

Purchas memorably called the Codex Mendoza “the choicest of my jewels” and proposed that “perhaps there is not any one History of this kind in the world comparable to this, so fully expressing so much without letters.”Footnote 30 For Purchas, the Mexica images made the document unique and remarkable. Running headers printed at the top of the page encapsulate what he found most salient, describing the manuscript as “Mexican historie in pictures. Chronicle without writing” (fig. 7) and “Mexican Pictures, or Historie without Letters.”Footnote 31 But the manuscript does indeed include alphabetic writing, and quite a bit of it. Every single one of the hundreds of figures is annotated with a written gloss in Spanish; additionally, every single page of pictorial content is complemented by a page of Spanish writing. It is this writing, in fact, that made the Mexica paintings legible to most viewers.

Figure 7. “Mexican historie in pictures. Chronicle without writing”: running header identifying the Codex Mendoza, in Samuel Purchas, Hakluytus posthumus or Purchas his pilgrimes (London, 1625), 3:1069. Huntington Library, San Marino, CA, RB 3341.

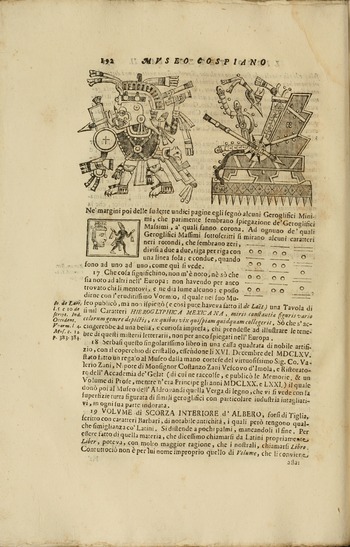

Scholars and collectors who examined pre-Hispanic codices in early modern Europe, unable to decipher indigenous pictorial writing, often had to shrug their shoulders in befuddled incomprehension. A 1667 publication describes the Codex Cospi as a book of “Mexican hieroglyphs, which are most extravagant figures and for the most part depict men and animals that are strangely monstrous.” Although the book includes woodcuts reproducing some of these figures, the author did not know what to make of them (fig. 8). “What these mean,” he noted, “I do not know, nor do I know of others in Europe who know it.” He considered the “hieroglyphs” both fascinating and inscrutable, a “literary mystery, not yet explained,” and their eventual decipherment “a beautiful and curious undertaking.”Footnote 32 Purchas used almost identical terms to describe his inability to interpret the characters on a Chinese map he discussed in the same 1625 volume in which he reproduced the Codex Mendoza.Footnote 33 By contrast, the Spanish text allowed early modern Europeans to access the Mendoza, making it an exceptional source. Combining indigenous paintings and Spanish text, this unique document allowed scholars—at that time and ever since—to read Mexica pictographic writing. It made Aztecs legible to Western audiences. Thus, while modern scholars have cherished the Mendoza for the enormous amount of detailed information it provides about Aztec history, economy, and culture; for its artistic quality; and for its early date of manufacture, the document's significance is in part due to its status as a primer for the study of Mexica pictorial writing and a kind of Rosetta Stone for its interpretation.

Figure 8. “Mexican hieroglyphs, which are most extravagant figures and for the most part depict men and animals that are strangely monstrous”: woodcuts reproducing figures from the Codex Cospi, in Lorenzo Legati, Museo Cospiano (Bologna, 1677), 192. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, CA, 85-B1671.

In divorcing image and word, Purchas responded to a crucial aspect of the codex: it combines elements from different hands and perspectives, bringing together Mexica and Spanish components that were crafted in relation to one another. Concerned above all with the indigenous component, Purchas considered the images the true—indeed, the only—content. He viewed the alphabetic writing as a mere supplement, a commentary on the pictorial writing that made the images legible, but not an object of study in itself. This approach has proved remarkably long-lived. From the seventeenth century to the present, scholarship on the Codex Mendoza has focused on interpreting the pictographs in order to study Nahua pictorial writing, mining the document as a unique and immensely rich source of empirical data on preconquest Mexica society. For Purchas and for later scholars, isolating the indigenous images from the Spanish text has often been an unquestioned maneuver.

In what follows, I use a different approach: I consider the images and texts as inextricably imbricated. Moving away from the content that is legible in the finished product, I begin with the blank page and examine the complex process through which indigenous and Spanish makers coproduced the codex, as well as the context in which they produced it. Investigating the making of the object sheds light on the creation of meaning in early colonial Mexico.

CREATING MEANING: PROCESS AND CONTEXT

One can read and look at the Codex Mendoza following a standard approach: turn the cover, open to the first page, start at top left, and move on from there, left to right, top to bottom, page after page, from beginning to end. Encountering the codex in this conventional and linear manner, from front to back, is a perfectly good way to get at its content. Political-military history comes first, followed by economics, and ending with sociocultural information—a coherent and completely unremarkable sequence. Dynastic history begins with the foundation of Tenochtitlan and moves in a linear fashion, year to year and ruler to ruler, until the end Moctezuma II's reign and the city's so-called “pacification and conquest.”Footnote 34 This vision of history connects time to place, with the city's establishment anchored in both space and time and the pictorial representation of each emperor's reign relating years of rule to the towns or communities he brought into the imperial fold—what Federico Navarrete has termed the “imperial chronotope.”Footnote 35 The second section details the tax obligations of individual towns, region by region. It is thus a logical continuation of the first, as it presents the material consequence and spatial distribution of military history. In the final section, customs are presented along a temporal axis, from birth to death. The document thus moves from spatialized imperial chronology to spatialized imperial economics to an account of how individual life cycles form part of the imperial social order. The codex yields wonderful and valuable information about the Aztec world. That is its explicit purpose, and that is how it has been used.

The manuscript, however, presents another possible way of encountering and decoding it: not from front to back, from first to last page, but, instead, from bottom to top, from the blank page to the finished document. This stratigraphic approach focuses on the sequential layering of elements and the multiple acts of translation and interpretation involved in producing the Codex Mendoza—the process, not the content; the making of meaning, not the information.

This possibility is suggested by the document itself. The very last page of the codex does not form part of the third and final section, nor does it contain indigenous paintings. It is a stand-alone textual addendum, in which a Spanish scribe addresses the reader directly to detail some aspects of the manuscript's production:

The reader must excuse the rough style in the interpretation of the drawings in this history, because the interpreter did not take time or work at all slowly; and because it was a matter neither agreed upon nor thought about, it was interpreted according to legal conventions. Likewise, it was a mistake for the interpreter to use the Moorish words alfaqui mayor and alfaqui noviçio; saçerdote mayor should be written for alfaqui mayor, and saçerdote noviçio for the novice. And where mezquitas is written, templos is to be understood. The interpreter was given this history ten days prior to the departure of the fleet, and he interpreted it carelessly because the Indians came to agreement late; and so it was done in haste and he did not improve the style suitable for an interpretation, nor did he take time to polish the words and grammar or make a clean copy. And although the interpretations are crude, one should only take into account the substance of the explanations that explain the drawings; these are correctly presented, because the interpreter of them is well versed in the Mexican language.Footnote 36

This note illuminates three elements that are crucial to understanding the meaning and significance of the Codex Mendoza in mid-sixteenth-century New Spain: (1) the process through which various participants composed the manuscript, (2) the context in which they created it, and (3) the importance of translation to its making. In terms of the manufacture process, the text outlines a sequence of steps that began with indigenous men painting figures on paper; these images then served as the basis of an oral account given by indigenous informants in Nahuatl; their speech was in turn translated into spoken Spanish by an interpreter (a nahuatlato, or Nahuatl-Spanish translator); and a scribe set down the Spanish oral interpretation as a written text. While both natives and Spaniards worked as interpreters in this period, the characterization of the interpreter as being “well versed in the Mexican language” suggests that in this case the nahuatlato was Spanish. At some point during this process, corrections were made to the text, crossing out specific factual statements—such as dates in the historical section—and replacing them with new information. Finally, a scribe added the concluding statement.

This process is directly related to the context in which the codex was created. The scribe explains that the enterprise had not been carefully prepared or thought through and, because of time pressure, the manuscript had to be compiled at breakneck speed. This necessitated working “in the legal manner” (“a uso de proceso”). In other words, the paintings were interpreted in a legal context rather than in a missionary context, as some scholars have proposed.Footnote 37 In fact, the series of steps outlined above was precisely the one followed at the time in court proceedings: indigenous painters created images that were then brought into a legal setting, where indigenous witnesses provided an oral testimony that was then orally translated by a court interpreter and set down as Spanish written text. Many contemporaneous pictorial manuscripts emerged as part of legal proceedings, among them codices Huexotzinco (1531), Tepeucila (1543), Tepetlaoztoc (also known as Kingsborough, 1554), and Osuna (1565), which present many intriguing correspondences with the Mendoza in the legal context, the use of native images as evidence, and the relationship between image and writing.Footnote 38

This legal setting makes the Codex Mendoza distinctive from other important manuscripts from that period, such as the Relación de Michoacán (1540), the Codex de la Cruz-Badiano (1552), or the Florentine Codex (ca. 1577), all of which involved the participation of Franciscan missionaries as well as indigenous painters and learned men, and all of which were created as books in the Western tradition. In mid-sixteenth-century New Spain, Western books carried connotations of learning, prestige, and privilege. The Franciscan Colegio de la Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco, inaugurated in 1536 to educate the native male elite and supported by Viceroy Mendoza, held a substantial library. Three years later, the printer Juan Pablos began operating the first press outside of Europe, a Mexico City branch of the important Seville printing house of Cromberger. Books and prints also arrived from Europe. The indigenous men of the Colegio were trilingual—fluent in Nahuatl, Spanish, and Latin—and bicultural. Their studies included grammar, rhetoric, and logic, the trivium of humanist education; they read scripture, the writings of the church fathers, and classical and modern authors.Footnote 39 They mastered the elegant Italic hand preferred by humanists and spread through printed manuals, as can be seen from the handwriting in the Cruz-Badiano and Florentine codices.Footnote 40 Thus, although natives and Spaniards repeatedly collaborated on the production of manuscript books, and although printed books and images were available in select circles in Mexico City at the time, the Codex Mendoza was created within the context of legal processes and indigenous painted and oral testimony rather than that of missionary activity or book production.

The results of such process and context are visible throughout the Codex Mendoza. One significant consequence, as the scribe noted, concerns the prose style. The Codex Mendoza lacks the polished, refined narrative with careful attention paid to wording and compositional choices that would befit a history or chronicle, as seen in many texts produced in the decades following the conquest.Footnote 41 It was penned by a working legal scribe (a notario or escribano), not a grammarian (gramático)—the term that Bernardino de Sahagún and other Franciscans used to identify their learned indigenous collaborators.Footnote 42 As a result, notarial conventions appear throughout the document, such as the constant use of the term ydem, indicated by the customary abbreviation, before the start of many paragraphs and before each item in a list, as was the norm when recording inventories or testimony. Another standard notarial scribal practice evident throughout the Codex Mendoza consists in the inclusion of a validating statement at the bottom of the page to register and certify cancellations, additions, or corrections to the original text, using set formulas such as “it is attested that … is marked out” (“va testado o diz … no enpezca”), “where it says … let it stand” (“o diz … vala”), and “it is corrected” (“va enmendado”).Footnote 43 This legalistic, testimonial approach is also seen in the frequent use of terms that convey the presentation of evidence and the faithful transcription of reported speech, including the verbs “mean,” “declare,” “demonstrate,” and “show” (significar, declarar, demonstrar, mostrar) and phrases such as “so that it may be understood” (“para que se entienda”). Other marks of notarial practice include the use of a pragmatic handwriting style common to official documents (letra cortesana), rather than the elegant Italic of learned humanists; the constant recourse to abbreviations common in notarial work; and the hurried quality characteristic of handwriting produced at a fast clip to capture the spoken word.Footnote 44

Another notable difference involves the manuscript's design. It lacks the paratextual elements conventional to Western books at the time, such as title page, frontispiece, dedication, index, and (at times) table of contents. The layout of text on the page eschews standard design elements such as rubrication, large decorative capital letters or headers, and the visual design of text in columns or inverted triangles. These conventions were well known to indigenous painters and writers in sixteenth-century New Spain, within and beyond Tlatelolco, as can be seen in the aforementioned manuscripts produced there, as well as in other mid-sixteenth-century documents, such as the Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca (fig. 9). This work, commissioned ca. 1560 by a native patron named don Alonso de Castañeda of Cuauhtinchan, includes painted images and alphabetic text written in Nahuatl. Word and image are arranged on the page according to standard elements of Western book design. The manuscript's makers used rubrication, enlarged the initial capital letters, organized the text in columns, and framed the images with a thick, black, solid line in the manner of woodcuts.Footnote 45 In other words, paratextual and design elements clearly establish that manuscripts such as the Relación de Michoacán, Codex de la Cruz-Badiano, Florentine Codex, and Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca were conceived and created as illustrated books in the European tradition. This is not the case with the Codex Mendoza. Although it is normally called an illustrated manuscript, it would be more accurate to describe it as a copiously annotated collection of paintings.

Figure 9. Icxicoatl and Quetzaltehueyac flank a stylized place-name glyph for Tula (Tollan, translated as “Place of Reeds”), in Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca, ca. 1560. Pigment on European paper, ca. 11¼ x 7⅞ in. (28.5 x 20 cm). Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Mexicain 46–58, fol. 2r.

The third noteworthy point about the final passage in the Codex Mendoza is the writer's keen awareness of the central role that translation and interpretation played in the making of the manuscript. In the midst of justifying the rushed manufacture and inelegant style of the prose, the scribe both certifies the translator's linguistic competence and derides some of the nahuatlato’s choices. The scribe criticizes the use of the term alfaquí, a Spanish word of Arabic origin denoting a Muslim cleric or an expert in Islamic law, rather than the more suitable sacerdote (priest) when referring to Aztec spiritual experts. He voices the same objection to the term mezquita (mosque), suggesting instead templo (temple). The critique signals the scribe's attention to the intertwining of linguistic and cultural translation. It had been a poor choice to use “such words,” he explained, as they “are Moorish” (“tales nombres … son moriscos”). This objection is intriguing because, as is well known, many sixteenth-century Spanish authors did not hesitate to refer to Mesoamerican temples as mosques—including, most famously, Hernán Cortés. In doing so, they explicitly related New World conquistas to the Old World reconquista, and the fight against Native American religions to the Spanish combat against Islam.Footnote 46 As Anthony Pagden has perceptively suggested, “ideologically the struggle against Islam offered a descriptive language which allowed the generally shabby ventures in America to be vested with a seemingly eschatological significance.”Footnote 47 In this context, the scribe's objection signals his attention to the connections between linguistic and cultural translation, as well as his awareness that the choice of a particular Spanish term to convey an indigenous category would carry with it specific associations. The use of Islamic terms would situate Mexica religion within discourses of combat against infidels; the use of more generic words without those associations would instead present the Aztecs as convertible pagans.Footnote 48

TRANSLATIONS

Guided by the scribe's attention to process and translation, I now turn to an examination of the five steps through which the Codex Mendoza was composed, in order to suggest that they represent a series of translations across media, languages, and cultural framings. I follow a stratigraphic approach, tracking the vertical layering of content and approaching the final manuscript as the accumulation of distinct deposits of medium, voice, and meaning. Throughout the process, translation was continual and left traces. As a result, the manuscript is not only a source of knowledge about the Aztec world but also a record of knowledge in the making, providing evidence of the decisions, the frictions, and the telling details that allow one to explore the cultural interpretation and negotiation involved in making and looking at images, books, and knowledge.

First Step: Painting

The Codex Mendoza began as a stack of blank sheets of European paper folded and gathered into eight booklets. Mexica painters then worked on 73 of the 142 total pages, using American pigments rather than European ones.Footnote 49 They left blank pages in between painted ones in anticipation of the Spanish text that would follow.Footnote 50 The painters’ work involved both Mesoamerican and European elements, among them materials, format, technique, iconography, style, and understandings of the role of the painter and the function of images.

In sixteenth-century New Spain, Spanish and indigenous painters, scholars, and litigants commonly used European paper. This is demonstrated by numerous roughly contemporary instances of indigenous paintings on paper, which were produced within administrative, legal, and missionary contexts. Indigenous painters quickly adopted this imported material, which, though different from pre-Hispanic supports, could function in ways comparable to native surfaces for painted books (such as prepared animal skin or amatl paper). The use of European paper does not appear to have been related to a scarcity of native paper. The second section of the Codex Mendoza indicates that the Aztec empire received 16,000 reams of amatl paper every year from tributary towns, and production of amatl continued well into the sixteenth century, as described, for instance, by the Spanish physician Francisco Hernández in the 1570s.Footnote 51 Some postconquest codices continued to be produced on amatl paper, among them the Codex Huexotzinco (1531), Codex en Cruz (ca. 1557–ca. 1569), and Codex Mexicanus (ca. 1600s). But European paper seems to have been favored by Spanish patrons and for works created in imperial contexts. Some scholars have suggested that in sixteenth-century New Spain, amatl paper stirred suspicions of idolatry given its numerous and important uses in Mesoamerican rites, many of which were documented in the Florentine Codex and in the works of Spanish writers.Footnote 52

The new support involved a major change in format that affected practices of painting, viewing, and reading. Pre-Hispanic manuscripts often took the form of square screenfolds that opened accordion-like, with images flowing from page to page in a long stream that could be viewed in smaller or larger portions depending on the exact manipulation of the document. Historical and dynastic pre-Hispanic codices allow viewers to encounter multiple generations of a ruling family at once, in an uninterrupted sequence that presents the past as a continuous stream. Calendrical and divinatory pre-Hispanic codices have a less fluid flow of content from page to page, but they still operate as screenfolds, whose articulated format can support the simultaneous viewing of multiple pages and openings. By contrast, the Mendoza is a Western-style book (thus literally a codex), with a rectangular format and, most significantly, a succession of pages that can only be viewed sequentially and in fixed ways. Any opening of the book presents a single possible pairing of verso, on the left, and recto, on the right. The format thus required painters to organize figures within a rectangular frame and to anticipate a staccato sequential viewing animated by the turning of the page. This interrupted viewing is amplified by the fact that the manuscript alternates between pictorial and textual pages, making it impossible for the image to exist as an independent and self-sufficient element—a major shift from pre-Hispanic conventions.Footnote 53

Based on a meticulous stylistic analysis of the paintings, Jorge Gómez Tejada has concluded that at least two painters are responsible for the figures.Footnote 54 It is extremely challenging to establish the number of individuals who worked on this document and to attribute specific figures to different hands, as they worked in a tradition that prized uniformity, regularity, and standardization rather than the distinctive, unique expression of an artist's mind or hand (the leading paradigm in Western art at the time, expressed in concepts such as inventio, disegno, and colorito).Footnote 55 It is worth noting that European influences are evident in terms of painterly technique and choices but not through the copying of European iconography or formats, as is the case in other, especially later, works—take, for instance, the use of book design elements including calligraphy, text layout, and page format in the Codex de la Cruz-Badiano or the copying of European prints frequently seen in manuscripts such as the Florentine Codex as well as in mural painting.Footnote 56

In terms of iconography and stylistic choices, the painters deployed numerous native pictorial conventions, including the use of symbols standard in Nahua pictography; the manner of combining figures to provide the names of individuals and places; the inclusion of pictorial metaphors such as speech glyphs to denote power and rule, or burning temples to signify conquest; and the connotations implied by specific colors, such as the use of a bright turquoise (Maya blue) to mark something as precious. The indigenous elements in the painted figures are so salient to Western eyes that many viewers, in the early modern period as well as more recently, have approached the document as a record of an indigenous world unmarked by European aspects. But there clearly exist many European elements in the paintings in the Codex Mendoza: a less abstract and more naturalistic rendering of the human figure, including its proportions; the use of black lines and a grayish-purplish wash to indicate the draping of fabric; the layering of translucent color washes to provide a sense of depth; and the perspectival depiction of the palace of Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin, among others.Footnote 57 The Codex Mendoza thus demonstrates how early and deftly indigenous painters began to combine elements from two distinct pictorial traditions.

Second Step: Singing the Book

In the second step of the process, these drawings were used as the basis for an oral narrative in Nahuatl. The scribe's final statement, which blames the rushed production of the codex on the time it took “the Indians” to come to agreement (acordar), suggests the participation of multiple indigenous speakers, at times in disagreement with one another.Footnote 58 If there were multiple indigenous voices and perspectives, their statements would have required not only translation from Nahuatl into Spanish but also coordination to compose a single text. What the manuscript does not make clear is whether the painters provided the oral recitation themselves or whether other speakers came in to perform the images through the spoken word.

This move from a visual to an oral register represents the continuation of a long-standing indigenous practice. Although pre-Hispanic codices recorded information in painted form, the pictorial register did not function on its own. Those who had access to codices would unfold the works in order to perform the paintings as spoken word or song.Footnote 59 Books were meant to be performed and heard as much as they were meant to be looked at. The visual-oral nature of Mesoamerican codices is clearly expressed in Nahua poetry, which often relates painted image and sound (and was itself recited as song, an oral rather than a written form).Footnote 60 One poem, to give one example among many, addresses the tlacuilo as both a “painter of books” and a singer, comparing a musical instrument to a screenfold book as it is opened:

In Nahua culture, the painted image and the spoken or sung word were closely connected to knowledge, both conceptually and in practice. Temple priests and sages known as tlamatinime (wise ones) kept, interpreted, and performed the most-meaningful painted books: divinatory codices, calendars, histories, books of song, and books of dreams. Through these books, these powerful men held and preserved in tlamatiliztli (knowledge), precious information about both the past—in the form of historical memory—and the future—in the form of calendrical and divinatory information. They were leaders with spiritual, political, and social authority. The Libro de los Coloquios, an indigenous-Franciscan source from the 1570s that reports on the earliest exchanges between missionaries and Nahuas in 1524, provides the following indigenous characterization of the tlamatinime: “Those who observe [read] the codices, those who recite [tell what they read]. Those who noisily turn the pages of the illustrated manuscripts. Those who have possession of the black and red ink [wisdom] and of that which is pictured; they lead us, they guide us, they tell us the way.”Footnote 62 The conceptual connections between knowledge, speaking, and power are also suggested by the Nahuatl terms for a ruler (tlatoani) or emperor (huey tlatoani, great ruler), from the verb tlatoa (to speak) and related to the noun tlatolli (word, speech, language). The ruler was thus, literally, the one who speaks—the one with the word, the authority, the knowledge. In the Codex Mendoza, as in other manuscripts, the Mexica emperor is portrayed with a speech scroll emanating from his mouth, as a sign of his power and authority. The sole exception in the codex is the vanquished Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin, whose defeat is signaled by his lack of speech (fig. 10). Thus, tlacuiloque could use the painted speech scroll both literally, to indicate the act of speaking, and metaphorically, to connote knowledge and authority—as possessed above all by the emperor or, to a lesser degree, by master artisans instructing their apprentices (see figs. 1 and 3). Speech scrolls could also represent song and prayer, powerful ritual acts, and even the creation of the world.Footnote 63

Figure 10. The reign of Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin (Motecuhzoma II), in the Codex Mendoza, ca. 1540s. Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, MS Arch. Selden A. 1, fol. 15v.

The Codex Mendoza is a rare Mesoamerican document that provides both indigenous paintings and a version of the oral recitation that the images elicited. It is not an unproblematic record. The oral account was preserved, as I have noted, through a double translation: spoken Nahuatl first rendered by the nahuatlato into spoken Spanish and then set down as written text. In addition, the indigenous men who provided the oral account were speaking for Spanish ears, decades after the conquest, at a time when indigenous elites were enmeshed in complicated sociopolitical negotiations with the new regime. And they also spoke in a legal context—in other words, in a highly charged setting associated with debate over competing claims, the cross-examination of witnesses, and the scrutiny of evidence. These factors surely affected their account, as well as its rendering into spoken and then written Spanish. The indigenous oral narrative not only enacted the picture into spoken word but also served as a form of self-fashioning, conveying Mexica culture in terms appropriate for the colonial context. Controversial elements connected to native rituals are notable for their absence. The text consistently uses the third-person plural rather than the first-person plural, distancing the narrator from the people represented in the manuscript. It is also written in the past tense, although it is unclear whether this presents the point of view of indigenous people in the colonial present, describing indigenous people in the pre-Hispanic past, or that of a Spanish voice talking about indigenous people. Despite these conditions, the Codex Mendoza provides fascinating insight into the relationship between painted images and spoken words in indigenous tradition. And, precisely because of these conditions, the codex sheds light onto the complex processes of transcultural knowledge production in the decades following the conquest.

Given the complexities of Nahua pictorial writing—in which glyphs can denote both words (logograms) and sounds (phonograms), and can be open to multiple interpretations—decoding the information presented in painted form required a profound knowledge of both indigenous pictorial writing and indigenous history and culture.Footnote 64 The paintings in the Codex Mendoza at times function as data, providing concrete information about dates, quantities, objects, and the names of places or people. In cases where paintings present data, the text records Nahua speech that elucidated the meaning of specific figures, succinctly stating in words what each painted image depicts: a specific number of loads of cacao or beans, a quantity of textiles of a certain design, etc. The individuals who provided the oral account of the images had the knowledge required to understand, for example, that an image showing arrows (mitl) and a shield (chimalli) is a literal painting of the diphrasis in mitl, in chimalli, a metaphorical locution for war; that eyes on a dark background stand for the nighttime starry sky; that tortillas symbolize food rations rather than individual pieces of flatbread; that specific hairstyles indicate a woman's marital status; and so on.Footnote 65

In some instances, the text notes elements that are not registered pictorially, meaning, presumably, that they originated in the oral account the paintings elicited. Such passages suggest the workings of Nahua historical memory and oral traditions. In the historical section, although the pictorial depictions of Mexica rulers are highly standardized and do not provide any details or identifying personal information beyond an individual's name, the textual entries include supplemental statements not contained in the images. Some are formulaic in content and wording, suggesting, perhaps, conventions in Nahua recitations of dynastic history. All of the entries on emperors, for instance, begin with their lineage and mention their military valor and victories in almost identical language. All contain almost identically worded passages stating that the individual under discussion had many wives of noble birth and fathered numerous sons who became noted warriors and added to the glory and power of the Mexicas, “because,” as one entry summarizes, “they considered it a sign of greatness” (“porque lo tenían por grandeza”).Footnote 66 The wording could come from either Nahua or Spanish rhetorical conventions, or combine both.

Some entries, however, include very specific extra-pictorial information that intimates Mexica historical tradition. For example, the entry for Motecuhzoma Ilhuicamina (Motecuhzoma I, ca. 1398–1469; r. 1440–69), an important ruler in Tenochca history, celebrates him thus:

Huehue Motecuhzoma was a very serious, severe, and virtuous lord, and was a man of good temper and judgment, and an enemy of evil. He imposed order and laws for the conduct of life in his land and on all his subjects, and imposed serious penalties for breaking the laws, ordering execution without pardon to any who broke them. But he was not cruel. He was kind to his subjects and jealous of their welfare. He was moderate with women, had two sons, and was very reserved in drinking; during his lifetime he was never affected by drunkenness, although the Indians generally are much inclined to drinking. He ordered offenders to be corrected and punished, and by his severity and good example, he was feared and respected by his subjects.Footnote 67

None of this content is presented on the page in pictorial form. The entries for his successors, which occasionally refer to this famous ruler, include shorter but comparable accounts of their strong moral character and good governance, characterized by law and order that bolstered the stature and power of the Mexicas and their allies. Some entries provide detailed accounts of significant military conflicts, and at times brief mentions of emperors’ personal traits—noting, for example, that Emperor Ahuitzotl (1440–1502; r. 1486–1502) had a “cheerful nature” and that “his subjects continually entertained him in his residence with diverse kinds of feasts and music with singing and instruments, so that in his houses the music never ceased, day or night.”Footnote 68 All of this content emerged from the oral recitation, pointing to the use of well-established conventions for both painting and recounting the past, and, perhaps, to the use of preexisting narratives.Footnote 69 In some entries, there is an added layer of Spanish commentary, as for instance the remark about native drinking in the passage on Motecuhzoma I cited above.

The final entry in the historical section discusses Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin, whose rule ended when Hernán Cortés (1485–1547) seized him as a prisoner. He was killed soon after, although the circumstances remain unclear—Spanish sources blame the disgruntled indigenous populace, and native sources blame the Europeans. This is the longest textual entry in the first section, extending over two pages, rather than the customary single page. The text praises the emperor lavishly, celebrating his “great seriousness and gravity … bravery and leadership in war … gravity, demeanor, and power.” The passage underscores the respect and fear that military leaders and nobles showed the sovereign, noting that as a sign of fealty they dared not look the emperor in the eye, and they always addressed him with a bowed head “out of respect to his majesty.”Footnote 70 It mentions his lawful and efficient administration of a vast and continually growing empire as well as the plentiful taxes paid by subject communities, prefiguring the topic of the following section of the codex. Whether or not this elaborate articulation of Motecuhzoma II's imposing standing can be taken as an accurate reflection of indigenous perspectives at the time the document was created, to European readers it would emphasize the stature of the Aztec ruler and, by extension, his empire, as well as the magnitude of the Spanish achievement of conquering such a formidable opponent. At the bottom of the second page, two paragraphs composed in a smaller and compressed handwriting were squeezed onto the sheet of paper, suggesting an editorial intervention—there is no comparable handling of the text anywhere else in the codex. While the document up to this point presents Mexica imperial history and follows preconquest indigenous historiography (as suggested by comparison with other accounts), this brief textual addendum represents a sharp turn to a Spanish postconquest perspective. The text announces the arrival of “Spaniards, discoverers of this New Spain,” a shift regarding both the protagonists of the historical narrative and the conception of the territory. The entry goes on to note, with studied circumspection, that “in the eighteenth year of said reign Motecuhzoma ended his rule and died and passed from this present life.” The passage briskly concludes: “Then in the following year … the Marqués del Valle [Cortés] and his companions won and pacified this city of Mexico and other neighboring towns. Thus was won and pacified this New Spain.”Footnote 71 The text makes no mention of the brutal war of conquest, or of the short reigns of the two indigenous rulers who succeeded Motecuhzoma II before the Spanish takeover, Cuitlahuac (1476–1520; r. 1520) and Cuauhtemoc (1496–1525; r. 1520–21).

This textual addition corresponds to a change in the painted history, where three year glyphs were inserted to prolong the year count for Motecuhzoma's reign (fig. 10). An initial revision increased the year count by two, extending the previous account to the “end and death of Motecuhzoma.” A further, third year count was then added and labeled “pacification and conquest of New Spain.”Footnote 72 The choice of the word “pacification” to describe the end of the war of conquest and the transition from indigenous to Spanish rule is not only a glaring case of rewriting native history from a Spanish perspective but also a reference to classical sources that used this term—a framework not without its critics both in the classical tradition and in the new genre of Spanish conquest literature.Footnote 73 These are the only instances in the document in which pictorial year glyphs were annotated with Spanish textual glosses. They are also the only year glyphs left in black on the white page, without the standard addition of Maya blue. In this way, the painted book and the oral narrative were both supplemented and adjusted to provide an alternate ending to the codex's historical section, one that gives pride of place to the Spanish conquest and suggests just how crucial the Spanish interventions—oral translation, written text, and scribal revision, to which I now turn—were in the creation of the Codex Mendoza and the production of colonial knowledge.Footnote 74

Third and Fourth Steps: Spanish Words, Spoken and Written

The next steps in making the codex involved overt acts of translation: the person identified as el interpretador (the interpreter) turned the spoken Nahuatl into spoken Spanish while a scribe, listening carefully and working quickly, set down this oral account to compose the written document. Given the length of the manuscript, this process must have taken place over the course of days. Close paleographic examination suggests the work of a single scribe.Footnote 75 Although the sequence of events involved (at least) two separate participants, the acts of translating from one language to another and from oral to written register appear to have occurred simultaneously: as the nahuatlato spoke, the scribe wrote.

Linguistic translation was far from new to indigenous communities. The far-flung Mexica empire included communities throughout Mesoamerica, incorporating multiple languages, ethnicities, and local cultures. As Frances Berdan has noted, the Codex Mendoza’s second portion registers tributary provinces to the south of the Basin of Mexico, where the languages spoken included Mixtec, Tlapanec, Nahuatl, Otomi, Matlatzinca, Chontal, Mazatec, Yope, Popoluca, and Chocho, as well as provinces in the northern Gulf Coast, whose inhabitants spoke Huaxtec, highland and lowland Totonac, Otomi, and Tepehua, as well as Nahuatl.Footnote 76 The Mexica translated town names in those languages into Nahuatl, and the indigenous painters and speakers involved in making the Codex Mendoza used these Nahuatl names both in the pictorial glyphs and in the oral account (as set down in translation). Thus, to name just one among many examples, people who called themselves tay Ñudzahui (People of the Rain Place) and lived in a town they called Ñuu ndaa (Blue Land) became, in Nahuatl translation, Mixtecah (Cloud People) living in Texopan (On the Blue Color).Footnote 77 The painters of the Codex Mendoza also translated the town's name pictorially by using the Aztec glyph, a blue patch with a footprint above it, rather than the Mixtec glyph, a hill with a turquoise jewel inside.Footnote 78 Other colonial manuscripts also show the long reach of Nahuatl as an imperial language, among them the Relación de Michoacán (1540) and the Relaciones geográficas questionnaires of the 1580s.

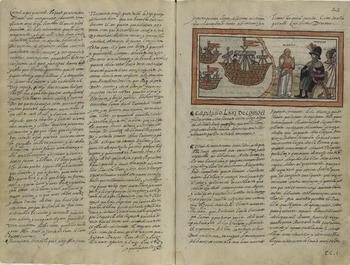

Though not a new concept, translation became a crucial, defining element of contact between indigenous peoples and Europeans. Interpreters facilitated and mediated the earliest encounters between natives and Spaniards. Cortés's initial foray into Mexico relied on the help of not one but two interpreters: the Spanish Franciscan Jerónimo de Aguilar (1489–1531), who translated Spanish into Maya, and the native woman who, in turn, translated Maya into Nahuatl. While her original name is not known, Spaniards renamed her Marina and later added the honorific doña in recognition of her important work. Nahua speakers translated “Doña Marina” as “Malintzin,” replacing the r with an l, as was common practice, and adding the honorific suffix -tzin to account for the Spanish doña. This moniker then became Hispanized as “Malinche” (ca. 1500/03–ca. 1529).Footnote 79 Perhaps the best-known and most infamous of early interpreters, she was both a performer of translation and herself its object. She appears as a central protagonist in numerous illustrated manuscripts created in the decades after the conquest that present history from various indigenous perspectives, among them the Lienzo de Tlaxcala (ca. 1552), the Codex Azcatitlan (ca. 1500s), the Florentine Codex (ca. 1577), and the Codex Durán (ca. 1579–81). In the latter she is depicted with a Spanish name, European clothes, and blond hair, thus pictorially translated from an indigenous to a European woman (fig. 11).Footnote 80 Translation was also central to the work of missionaries and preachers, who learned indigenous languages and authored books about them. Almost three-quarters of the first hundred titles printed in New Spain, which appeared between 1539 and 1580, related to evangelization and to facilitating communication with indigenous converts. They include fourteen vocabularies, artes de la lengua (grammars), and bilingual confessionals.Footnote 81 As I have noted, many sixteenth-century pictorial manuscripts involved the participation of Franciscans.

Figure 11. Marina (a.k.a. Malinche, Malintzin) translating the exchange between Hernán Cortés and an indigenous interlocutor, in Diego Durán, Historia de las Indias de Nueva España e islas de la Tierra Firme (a.k.a. Codex Durán), 1579–81. Biblioteca Nacional de España, Fondo Reservado, VITR/26/11, fol. 202r.

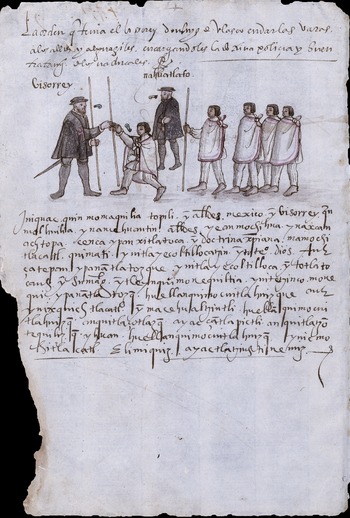

After the conquest, interpreters were central protagonists in administrative and legal contexts. They held tremendous political and social power, serving as intermediaries between indigenous people and the Spanish rulers and courts. Aware of the potential for abuse of power, Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza included in his 1548 compilation of ordinances several prescriptions for nahuatlatos, who were forbidden to accept gifts or bribes from natives or from Spaniards, to hear cases in their houses, and to act as solicitors (procuradores). Ordinances from the early 1560s repeated these guidelines—the need to reiterate them suggests that they must have been habitually breached—and added that interpreters should not receive food or jewelry as rewards. In 1579, officials forbade interpreters from building houses or trading in building materials and basic food items.Footnote 82 The Codex Osuna (1565), with images by indigenous painters and written text in both Nahuatl and Spanish, was produced as part of a legal investigation (proceso) of the administration of the second viceroy of New Spain, Luis de Velasco (1511–64; r. 1550–64). The manuscript contains numerous mentions of individual interpreters and the important and at times controversial roles they played in local governance and negotiations among factions. One of the paintings shows the viceroy personally deputizing indigenous constables (alguaciles), who had oversight over indigenous commoners (macehuales), with the assistance of a nahuatlato (fig. 12).Footnote 83 The interpreter is portrayed as a bearded Spaniard dressed in black European-style clothes identical to those worn by the viceroy; the only distinguishing mark between the two is the governor's sword. Although the interpreter stands behind the other participants in the scene, his presence is necessary and his authority evident.

Figure 12. Viceroy Luis de Velasco (r. 1550–64) deputizing indigenous constables with the aid of an interpreter (nahuatlato), in the Codex Osuna, ca. 1565. Biblioteca Nacional de España, Fondo Reservado, VITR/26/8, fol. 9v (detail).

Translators and scribes held an extraordinary level of authorial power in early colonial manuscripts. Indigenous and Spanish participants alike inhabited a world suffused with linguistic, cultural, and political translations and mistranslations. Old World military-religious battles provided the framework for interpreting New World encounters, with the Reconquista a constant referent for Spaniards and with Amerindian spiritual practices often misrepresented through terms imported from Islam. Old indigenous gods were at times translated into what Spaniards called idols or demons, at times into versions of European classical pagan figures. The Florentine Codex, for example, opens with depictions of Aztec deities, which the Spanish-language text characterizes as American versions of Greco-Roman heroes and gods: Huitzilopochtli is presented as “another Hercules,” Tezcatlipoca as “another Jupiter,” Chicomecoatl as “another goddess Ceres,” Chalchiuhtlicue as “another Juno,” Tlazolteotl as “another Venus,” Xiuhtecutli as “another Vulcan,” and Tezcatzoncatl as “the god of wine, another Bacchus.” The Nahuatl text, however, does not make these analogies.Footnote 84

In the Codex Mendoza, the Nahuatl-Spanish interpreter and the scribe were as involved in the production of knowledge and meaning as the indigenous painters and speakers. The manuscript is in effect the result of a series of translations: from the image to the spoken word, from the spoken word to the written word, from Nahuatl to Spanish, and from pictographic writing to alphabetic writing. It is also the result of hermeneutic translations that interpreted the information about the Aztec past within the new colonial context.

Because of its early date and its manufacture process and context, the Codex Mendoza may be the postconquest manuscript most visibly concerned with translation. The focus on translation is explicit from the document's very beginning. At the opening of the codex, on folio 1v, a paragraph explains the meanings of the Mexica year glyphs that appear so prominently throughout the first section as well as the basics of the indigenous calendrical system. This description is illustrated by a strip with thirteen year glyphs, each one annotated with bilingual glosses that provide the textual translation of the image in Nahuatl (above, in red) and Spanish (below, in black). The manuscript thus opens with both the historical account of the foundation of Tenochtitlan and a primer in the basics of Nahua painted dates, which allows the reader to decipher the Mexica paintings. In the second section, the reader finds the textual translations for glyphs denoting quantities, learning, for example, that a banner indicates the number twenty; a symbol that looks like a feather (also described as hairs or a pine tree), the number four hundred; and an incense bag, the number eight thousand.Footnote 85 In the third section, most of the textual descriptions begin with the statement: “explanation of the drawings” (“declaración de lo figurado”).Footnote 86 The paintings are not illustrations of the text. Rather, images and words provide information encoded in two separate systems, a Mexica one of pictorial writing and a Spanish one of alphabetic writing. The Spanish text translates both the content, conveying in written words the information that the images present, and also the system of Mexican pictorial writing itself. The dual translation offered in the Codex Mendoza has made this manuscript enormously valuable to readers from the sixteenth century to the present, allowing them to learn to read Aztec pictorial writing.

The translation is incessant, repetitive, even redundant. Every single figure is annotated with an alphabetic gloss that translates it, and the text on the facing page repeats the same information, so that in effect every image is translated not once but twice. In addition to this repetition, each glyph is translated every single time it appears, even if it recurs repeatedly from folio to folio, or within the same folio. The translation never stops—it is never assumed that the reader already knows that a banner stands for twenty or that a burning temple denotes conquest, even if there are dozens and dozens of nearly identical figures. Every single one of them is identified with an alphabetic label, something that suggests the professional, obligatory precision of the legal scribe who recorded the translation. More than information, this is evidence.

Translation is not only linguistic but also cultural—for instance, when the jaguar is rendered as “tiger” (see fig. 5). Another, more significant type of cultural translation involves the framing of Nahua culture in ways that were relevant in the colonial context and in particular for Spanish audiences in both New Spain and Europe. Take, for example, the depiction of Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin's palace (fig. 13). Art historians have noted that this image provides the only perspectival view in the Codex Mendoza, demonstrating the painter's engagement with European artistic techniques and providing a Europeanized vision of Aztec rule.Footnote 87 A comparable maneuver is evident in the text, which, like the image, presents the Aztecs as an example of a civilized people. It does so by celebrating their “order,” “good governance,” and “good rulership” (“orden,” “buen gobierno,” “buen regimiento”)—these were the precise Spanish words used to connote policía and civitas, critical categories for Spanish and, indeed, European political philosophy at the time. These terms would have clearly communicated to a European reader, in recognizable categories, that the Aztecs were highly civilized people.Footnote 88 As the revision to the history of the reign of Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin shows, acts of cultural translation involved revision, reinterpretation, and transformation. At stake was the reconfiguration of indigenous painting, and indigenous culture more broadly, in ways that made them legible and assimilable within colonial and imperial frames of interpretation.

Figure 13. The palace of Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin (Motecuhzoma II), in the Codex Mendoza, ca. 1540s. Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, MS Arch. Selden A. 1, fol. 69r.

CONCLUSION: REINVENTING BOOKS AND PAINTING

In sixteenth-century New Spain, painting a book about indigenous history and society was no simple matter. At the time, the status of indigenous books and paintings was being fiercely contested and negotiated, as were indigenous knowledge and belief more broadly. The complex process of manufacturing the Codex Mendoza took place in the midst of European suspicion and enormous violence toward indigenous peoples and their cultures.

From the earliest encounters, conquistadores and missionaries alike understood the connection between painted books and native rituals. An account of the Spanish forces’ very first incursion into an indigenous village after disembarking on the Gulf Coast, written by conquistador Bernal Díaz del Castillo (1492–1584) decades after the events took place, explains: “We found the houses of idols, the places of sacrifice, the spilt blood, the incense they used for perfuming, other things relating to idols, stones they used for sacrifices, parrot feathers, and many books of their paper folded like handkerchiefs from Castile.”Footnote 89 Europeans in the New World considered indigenous codices, like indigenous religion, to be idolatrous and horrifying, the work of the devil.

And so, as part of their war against the devil, conquistadores and missionaries burned the vast majority of pre-Hispanic codices. The destruction that began in 1519 went on for decades, spreading as Spaniards moved across Mesoamerica and beyond. The burning of indigenous codices is a commonplace of histories of conquest and evangelization. The Franciscan Diego de Landa (1524–79), one of the fiercest fighters in this religious war, wrote of his experience with the Maya in Yucatán in the early 1560s: “These people also used certain characters or letters, with which they wrote in their books about the antiquities and their sciences… . We found a great number of books in these letters, and since they contained nothing but superstitions and falsehoods of the devil we burned them all, which they took most grievously, and which gave them great pain.”Footnote 90 Landa claimed to have overseen the burning of twenty thousand statues and forty Maya pictorial manuscripts.Footnote 91 In the 1580s, the mestizo historian Diego Muñoz Camargo (ca. 1529–99) composed a history of the region of Tlaxcala since the arrival of Spaniards. One of the drawings illustrating his manuscript depicts Franciscan friars “burning … all the clothing and books and apparel of the [native] idolatrous priests” six decades earlier (fig. 14).Footnote 92 Muñoz Camargo criticized the destruction of historical accounts among the burned documents, noting that the communities had recorded history “through characters and paintings which, by mistake and without understanding what they were, the first missionaries who came to this land ordered burnt, with Catholic zeal, believing [entendiendo] that these were books of their ancient rites and idolatries. And it was thus that among those books were burned great histories of their origins and deeds, of their wars and towns.”Footnote 93 As scholars including Serge Gruzinski, Walter Mignolo, and José Rabasa have noted, the fury of this violence against indigenous pictographs was in part a result of European notions of what exactly counted as writing, as literacy, as a book, and as legitimate knowledge. The effort to conquer territories, bodies, and souls extended to colonializing epistemologies and imaginaries.Footnote 94 It is impossible to know how many indigenous documents existed before the arrival of Europeans, but almost none managed to survive the ferocious battle against Mesoamerican culture. Today, the entire corpus of extant pre-Hispanic documents consists of eight Mixtec codices, four Maya codices, and a single Aztec codex, the Matrícula de Tributos.Footnote 95

Figure 14. “Burning of all the clothing and books and apparel of the idolatrous priests, which the friars set on fire,” in Diego Muñoz Camargo, Relación de Tlaxcala, ca. 1581–85. Glasgow University Library, Sp Coll MS Hunter 242, fol. 242r.

In the midst of this destruction and in a period of dramatic, often vexed cultural transformation, indigenous painter-scribes (tlacuiloque) reinvented themselves and were reconfigured into colonial painters (pintores). They continued to paint, adding to their repertoires new materials such as European paper and pigments, as well as new pictorial techniques, style, and iconography. In the decades following the conquest, manuscript painters combined indigenous and European traditions and continued to produce pictorial manuscripts for multiple uses by indigenous communities and by the viceregal administration, and in some cases for export to Europe.Footnote 96 The conquest in fact spurred the creation of new manuscripts, some in response to Spanish demand, others as products of legal or administrative records, and yet others commissioned by indigenous communities to make claims about their histories and rights to lands. Postconquest codices recorded and communicated native history and traditions at a time when that history was changing rapidly and dramatically, and when those traditions were being ferociously persecuted. This was also a period of horrifying suffering caused by the spread of epidemic diseases among the indigenous population. The indigenous painters who worked on the Codex Mendoza may have been old enough to have survived the conquest, perhaps having lived themselves through the dramatic and horrifying three-month siege in which the city's native population was decimated through starvation and smallpox. They survived the devastating epidemics of the early and late 1530s and created their work around the time of the terrible epidemic of 1545–48, a plague of unprecedented morbidity that brought a level of suffering and death that shocked the Spanish chroniclers who reported its devastation of the native population.Footnote 97

As I have detailed, making the Codex Mendoza involved a complex process of translations of multiple kinds. These took place not only across media, languages, genres, and cultural categories but also at important conceptual levels. The transformation of the indigenous painted manuscript (amoxtli) into a Western-style book (libro) was one among many profound epistemic and ontological translations that took place in sixteenth-century New Spain. In the case of the Codex Mendoza, translation involved not only the reinvention of the book but also the reinvention of image making, image makers, and painted knowledge. The native image was neither inconsequential nor safe. It became circumscribed by words, restricted to certain topics, and requiring translation to become legible.