INTRODUCTION

In 2011, the Congolese government engaged in a public-sector reform unprecedented in scale and territorial reach in the country's contemporary history: the so-called bancarisation reform. Assigning individual bank accounts to all civil servants, the reform had three major goals: paying salaries on time, paying salaries without deductions, and achieving congruency between the civil servants actually working and those represented on the payroll. Formally, the reform was a response to donor pressure and part of a larger attempt to establish a reliable payroll management system (Moshonas Reference Moshonas2014). While the reform was justified – the civil service payroll accounts for 67% of all official government spending (Marysse & Megersa Reference Marysse and Megersa2018) – its implementation must be seen as an attempt to overcome what Boone (Reference Boone2012: 625) called the ‘uneven territorial reach of the state’.

Indeed, the country's size, infrastructural endowments and geographically uneven patterns of governance have long posed significant challenges to anyone seeking to penetrate and govern across the Congolese territory (Brunea & Simon Reference Brunea and Simon1991; Pourtier Reference Pourtier and Trefon2009; Schouten Reference Schouten2013; Verweijen & van Meeteren Reference Verweijen and van Meeteren2015). The unequal presence of state infrastructure and personnel goes back to colonisation and has led the state to count on other actors to implement its actions. The education sector is a prime example of this hybrid mode of governance (Titeca & De Herdt Reference Titeca and De Herdt2011). Faith-based organisations (FBOs), which manage the lion's share of public schools, have the prerogative to recruit and deploy teachers. Until recently, they also distributed salaries and the government never had a complete overview of those teachers actually working. After the recent expansion of schools, approximately 400,000 paid public-school teachers now work far out in very remote areas (Brandt Reference Brandt2017). Bancarisation was thus the government's attempt to bypass FBOs and gain direct access to teachers via bank accounts.

In practice, however, the bancarisation reform had to cope with the uneven territorial reach of the banking sector. The reform's full success depended on a vital prerequisite that was absent: the existence of banks throughout the Congolese territory. While banks had indeed started to cover major urban areas on the eve of the reform, ‘in a vast country with fewer roads than Luxembourg, hardly anyone lives anywhere near a bank branch’ (The Economist 2015), especially in towns and rural areas. Yet intriguingly, in the DRC, the reform came to be ‘presented as a resounding success’ (Moshonas Reference Moshonas2018: 6; see also Marysse & Megersa Reference Marysse and Megersa2018: 17). How is this possible, given such striking infrastructural absences?

We propose to go beyond prevalent understandings of reforms as instruments in the hands of an elite that seeks to reinforce the status quo with few changes to actual practices (Trefon Reference Trefon2011; Cuvelier & Mumbunda Reference Cuvelier and Mumbunda2013; Englebert & Kasongo Reference Englebert and Kasongo2016; Jené & Englebert Reference Jené and Englebert2019). Despite the fact that various stakeholders used the reform to pursue their own interests – which is a truism – it would be only partially correct to blame ‘deeper politics’ (Englebert & Kasongo Reference Englebert and Kasongo2016: 27) either for its success or for the lack of it.

Instead, our main argument is that the way the reform unfolded was not orchestrated by an elite, but was the result of an assemblage of actors – providers and intermediaries – that both hid the reform's flaws and worked to save it, yet also mitigated its effects in rural areas. Indeed, the bancarisation reform went conspicuously uncontested, but we show that the reasons for this vary widely between city and countryside. While in the cities, teachers, and civil servants more generally, eventually appreciated the reform, the situation was completely different in the remote parts of the country. There, it only survived at the price of accepting a gap between reform image and reality. This considerably mitigated the reform's ambitions. Specifically, the uneven character of the territorial reach of the state was reproduced rather than overcome.

Conceptually, our analysis draws on the literature on state infrastructural power and the ethnography of development interventions (Mann Reference Mann1984; Mosse Reference Mosse2004; Li Reference Li2005, Reference Li2007b; Mosse & Lewis Reference Mosse, Lewis, Lewis and Mosse2006). From the first literature, we learn that weak state infrastructural power not only reflects long-term geographic, demographic or historico-economic processes, but also mirrors the geopolitical strategies deployed by states to stay in control. Though we partly accept this argument, we also emphasise the role, at least potentially, played by non-state actors in this political process. The literature on the ethnography of development interventions allows us to flesh out this argument, as it takes a broad view of political manoeuvring, in-between the open expression of voice and silent exit. In other words, the absence of open contestation should not be confused with agreement.

OUTLINE AND METHODOLOGY

After detailing our conceptual framework, we develop the empirical case of the bancarisation reform in three steps. First, we situate the preparation of the bancarisation reform vis-à-vis preceding reforms. Second, we analyse strategies used by banks to cover the countryside. We focus on the largely rural areas in the newly created province of Haut-Katanga. The study draws on a wider research endeavour that includes 354 semi-structured interviews over a total of 15 months in four different research periods (July–December 2013; January–May 2015; December 2015–May 2016; March and May 2018). Adopting a multi-scalar ‘entangled social logics approach’ (Olivier de Sardan Reference Olivier de Sardan2005: 12), interviews with representatives of all relevant stakeholders were conducted in the national capital of Kinshasa, the provincial capital Lubumbashi and in all six rural educational sub-divisions: teachers and principals; government and religious officials; staff from private companies and NGOs in charge of providing salaries. Second, we analyse the reform's survival. Here, we combine the qualitative analysis with national-level quantitative data so as to generalise from our case. We use maps to illustrate some of these data. Third, we conclude by pointing out what this analysis can tell us about the social reproduction of the state's uneven territorial reach.

THE GEOPOLITICS OF RESHAPING THE STATE'S TERRITORIAL REACH

Michael Mann's (Reference Mann1984, Reference Mann2008) definition of despotic and infrastructural power provides a good start when it comes to discussing the design and implementation of state reform, in post-colonial settings in general and in the DRC in particular. Mann proposes the concept of despotic power to describe ‘the range of decisions the state elite is empowered to make without consultation with civil society groups’ (Reference Mann2008: 355). However, exercising power over space also requires a vast socio-material network (Schouten Reference Schouten2013). Mann proposes the concept of ‘infrastructural power’ (IP) to denote the state's ‘capacity to implement political decisions throughout the realm’ (Mann Reference Mann1984: 189). Mann argues that, in the case of the former colonies in Africa, it is very important to bear in mind the spatially uneven character of the (post-)colonial states’ IP: colonial powers ‘had not in truth governed the whole colony. Instead, they had focused on high-value zones where minerals could be extracted or where plantation agriculture could be practiced’ (Mann Reference Mann2008: 363). The Congo is a prime example of ‘a territorialization of authority that is based on a dichotomy between l'Afrique utile and the economic margins’ (Verweijen & van Meeteren Reference Verweijen and van Meeteren2015). These colonial patterns of uneven infrastructural power were to a large extent inherited and perpetuated by post-independence states and transnational private networks (vom Hau Reference vom Hau2012; Verweijen & van Meeteren Reference Verweijen and van Meeteren2015).

This (hi)story of infrastructural power in post-colonial states needs to be enriched in two related ways, however. First, beyond factors related to geography, demography and historical endowment, infrastructural power also partly reflects geopolitics: ‘Rulers can incorporate, not incorporate, or abandon regions, social groups, and functions strategically, as a function of their attempts to govern effectively and hold onto power’ (Boone Reference Boone2012: 627). This point has been made for the DRC too, e.g. by Hoenke (Reference Hoenke2009: 10) who argued that the Mobutu regime was strengthened by not building national communication and transport infrastructure (see also Schouten Reference Schouten2013). This observation reminds us that ‘Infrastructural power is a two-way street: It also enables civil society parties to control the state’ (Mann Reference Mann2008: 356). As a consequence, uneven territorial statehood may be the logical outcome of the regime's strategy to preserve its (despotic) power. Second, while Boone's perspective on the geopolitical drivers of state infrastructural power remains state-centred, her proposal to understand IP ‘as the product of negotiation and conflict between central and local actors’ (Reference Boone2012: 627) also allows for a more decentred reading of these processes: what about the local actors themselves, what is their interest in extending – or not – the state's infrastructural power, what means do they have to enrol the state in their projects and, last but not least, what does all this imply for the state's ability to effectively implement reform? These questions also echo Weiss’ definition of IP as ‘the state's ability to link up with civil society groups, to negotiate support for its projects, and to coordinate public-private resources to that end’ (Weiss Reference Weiss2006: 168) adding that infrastructural power ‘is fundamentally negotiated power’ (Reference Weiss2006: 172).

At this point, we can draw on Tania Li's work to add more ethnographic nuances and shades to Mann's and Weiss’ raw brush strokes of the contours of IP. Li (Reference Li2007a: 276) proposes to look at the realisation of a particular policy as an assemblage of heterogeneous elements, material and non-material. She argues that all types of public action, lest they are imposed by force, need to be socially, technically and politically situated: First, ‘there are processes and interactions, histories, solidarities and attachments, that cannot be reconfigured according to plan’ (Li Reference Li2007c: 17). Second, Li points to ‘available forms of knowledge and technique’ (Reference Li2007c: 17). And a third limit is formed by the practice of critique, or ‘politics, the possibility to challenge its diagnoses and prescriptions’ (Reference Li2007c: 17). The possibility to contest the rationale of a policy, in whatever way, obliges policymakers to respond, but political contestation is in itself also a patterned practice. Or rather, a range of patterned practices: These practices may vary from the routine mechanisms of voice and exit that make up the dynamics of multiparty politics in established democratic regimes to much more ambiguous types of contestation that take place at an infrapolitical level (Scott Reference Scott1990), i.e. within the framework defined by the state, or at least partly reproducing it. To be sure, in contrast to Scott (Reference Scott1990), Li puts the emphasis on a plethora of forms of adapting, coping, accommodating, negotiating, etc. She calls these processes ‘reassembling’, defined as ‘grafting on new elements and reworking old ones; deploying existing discourses to new ends; transposing the meanings of key terms’ (Li Reference Li2007b: 265).

In other words, the unfolding of a reform does not necessarily follow a pre-designed homogeneous implementation but rather needs to be seen as the outcome of multiple acts of harmonisation, translation and composition (Mosse & Lewis Reference Mosse, Lewis, Lewis and Mosse2006). While a pre-designed reform can encounter serious difficulties when put into practice, the different actors involved in a reform are able to come to terms with it through the work of reassembling. It goes without saying that non-state actors’ capacity to reassemble a reform is itself highly unequal and contingent on local circumstances and conjunctures. As Rod Rhodes analysed accurately for the case of the UK, reassembling has the effect of hollowing out the state's ability to act effectively (Rhodes Reference Rhodes2007: 1248): it may still intervene, but there is an inevitable gap between what it intends to do and what it eventually achieves. The latter is to be negotiated within a policy network of non-state actors (Diemel & Cuvelier Reference Diemel and Cuvelier2015). This also means that the state's mode of operation shifts, from a command operating code to diplomacy, or negotiation (Rhodes Reference Rhodes2007: 1248).

The project of the bancarisation of teachers’ salaries allows us to discuss these matters in empirical detail. Within the state's discourse, the bancarisation of teachers’ salaries was defended as an attempt to redress the historical deficiency of state infrastructural power. The reform was indeed supposed to vastly improve the capacity and spatial reach of the state administration throughout its territory. The problem, however, is that the reform itself must first be implemented: how so, in a country with a very poorly and unevenly developed network of bank offices? More specifically, in the more remote parts of the country, how exactly did the bancarisation reform take shape? Initially set up as a way to overcome the uneven territorial reach of the state, our hypothesis is that it converged into its intended outcome only in those areas – the major urban centres – where the state's IP was more or less in place already, but the way in which it was reassembled in other regions led to a further entrenching of the state's unequal reach. This hypothesis is broadly in line with Boone's suggestion that the contours of IP are politically determined, but, at variance with Boone's stress on geo- or socio-strategic considerations on the part of the central state, we rather explain this outcome in terms of the divergent political capabilities of local actors to react to the central state's proposed reform.

In what follows, we first describe the bancarisation reform as the most recent attempt in a long line of projects with the goal of collecting data on state agents and facilitating an effective and transparent state administration, before zooming in on two types of reassembling: first by the banks themselves, then by the actors side-lined by the initial reform project.

BANCARISATION IN ORDER TO OVERCOME ADMINISTRATIVE DEFICIENCY

The bancarisation reform was not the first effort to challenge administrative deficiency in the Congolese education sector. The issue came up for the first time in the early 1980s (Gould Reference Gould and Gran1979). Due to a prolonged economic crisis, systematic embezzlement of public funds and the government's incapacity to repay debts, the country fell under the auspices of Structural Adjustment Programs. These programs sought to cut public expenditures and reduce the size of the public sector. The education system was identified as a major source of inefficient government spending. Due to mounting pressure by the IMF, a new institution was created: the Service de Contrôle de la Paie des Enseignants (SECOPE, Department for the control of teacher salary payments). SECOPE had the objective to identify and subsequently reduce the number of public-school teachers. SECOPE did so rather successfully and extended the state's infrastructural power. For the first time in Congolese history, most teachers’ identities were centrally managed. SECOPE was not supposed to intervene in the actual process of payment, however. Money was dispatched from Kinshasa to provincial banks, where it was picked up by school network administrators and distributed to school principals. This has always proved rather easy in urban areas and challenging in rural regions. In remote areas, cash went through the hands of several intermediaries before reaching teachers. A World Bank public expenditure tracking study (World Bank 2008: 84) suggested however that, on average, only about 5% of disbursed salaries did not reach teachers.

The major source of loss was not situated in the payment system itself, but rather upstream, at the moment of listing teachers on the payroll. In a context of rampant payroll fraud after the political and economic turmoil in the early 1990s, payroll updates in the 1990s became increasingly delayed and erratic. Also, fictitious teachers and schools re-appeared on the payroll. SECOPE only became subject to renewed donor and government attention in the early 2000s (World Bank 2004; Verhaghe Reference Verhaghe2007; Andrianne Reference Andrianne2008). From the perspective of poverty reduction, returning donors – led by the World Bank – wanted to temporarily fund teacher salaries on condition of the improved reliability of SECOPE's database. This condition was subsequently inscribed in key government documents (Brandt Reference Brandt2018). Between 2005 and 2013, several attempts were made to reform SECOPE, conduct censuses, identify all teachers and establish a comprehensive database. Although more than 200,000 teachers were added to the database (though not all of them also to the payroll!), the system remained porous and unreliable (Brandt Reference Brandt2018).

This is where the bancarisation reform comes in. The policy of paying all civil servants’ salaries into individual bank accounts represented an entirely new framing of the problem. Responding to donor conditions in the Government's Economic Program from 2003 to eliminate arrears of salary payments to public servants, the reform was conceived as a public-private partnership between the Congolese government and commercial banks, united under the umbrella of the Congolese Association of Banks. The main government actors in the reform process were the Prime Minister, the Pay Directorate within the Ministry of Budget, the Ministry of Finance, the Comité de Suivi de la Paie (Payment Monitoring Committee) within the Central Bank, and the Ministry of Civil Service.

In May 2011 various public and private stakeholders met for the first preparatory meeting in the Hotel Sultani in Kinshasa. They foresaw a gradual implementation, from urban to rural areas. The bancarisation project started with six banks in August 2011 to pay members of ministerial cabinets and secretary generals via individual accounts. Prime Minister Matata Ponyo announced the expansion of the bancarisation of public workers at his inaugural speech in May 2012. In the second stage, the bancarisation was made operational in some large urban areas (July 2012). In the third stage, bancarisation was gradually extended to include provincial capitals (October 2012) and then sub-regional capitals (chef-lieux des districts et certaines communes) in February 2013. The Protocole d'Accord sur la paie des agents et fonctionnnaires de l’état between the government and the Congolese Association of Banks was signed on 1 December 2012, several months after the reform had been launched. Finally, in May 2013, bancarisation was supposed to have reached teachers in rural areas. Under the auspices of the Congolese Association of Banks, the Congolese territory was subdivided among 15 private banks willing to engage in the payment of teachers’ salaries.

Confidence in the banking sector was very low in the country as, due to hyperinflation, banks were often confronted with liquidity shortages, especially in the years 1991–1994. From the turn of the millennium, however, banks started a slow recovery. Though ‘teachers were not the most desired clients’ (Banker in Kinshasa, Int. 23.12.2013), banks saw their participation in the bancarisation policy as a long-term investment and an opportunity to broaden their client base and acquire a presence in the interior provinces with a relatively thin monetary economy.

The public-private partnership was marked by several characteristics. First, according to the president of the Comité de Suivi de la Paie/Banque Centrale du Congo, ‘the theory was that bancarisation encourages banks to open new branches. This effectively happened in Kinshasa, especially concerning ATMs, but not really in the province’ (Int. 18.12.2015). Second, the assignment of banks to different territories was ‘not according to objective criteria. Some banks received clients in areas where they had no branches, although other banks would have been present. Distribution of clients was about sharing the cake’ (President of the Comité de Suivi de la Paie /Banque Centrale du Congo, Int. 18.12.2015). Third, this was a public-private partnership in which teachers didn't have a choice to change banks nor an exit option: the market mechanism was switched off and banks acquired a government-backed monopoly on public servants’ bank accounts. Initially, the government compensated for this public role and took charge of banking fees, but after some years it reneged on this commitment for teachers with a monthly income above US $100.

Interestingly, the implementation design neglected early warning signs. The official summary of the mentioned meeting in May 2011 noted for instance the ‘insufficiency of commercial banks’ and the ‘lack of transportation fees in order to transport money from provincial capitals to rural areas’. This knowledge was available, as it is also mirrored in relevant reports on the topic (Dolan et al. Reference Dolan2012), but apparently it was not considered a serious enough issue.

Along similar lines, central educational stakeholders – national and provincial Ministries of Education, the faith-based organisations that run most of the schools, SECOPE and teacher unions – were side-lined from the preparation process, even though the Ministry of Education manages about two-thirds of all civil servants. This is surprising, given the power of the Catholic church and other FBOs in influencing educational reforms (Titeca & De Herdt Reference Titeca and De Herdt2011). SECOPE staff, for example, claimed that they were only invited to participate in the reform when implementation problems emerged in 2013. In fact, the reform did not include existing knowledge about teacher payment modalities (Verhaghe Reference Verhaghe2007; Andrianne Reference Andrianne2008). In Mann's (Reference Mann1984) words, the government over-estimated its despotic power as it designed the reform without including major societal actors.

However, the actual process of bancarisation of teachers’ salaries is fundamentally constrained by the IP the state was counting on: banking infrastructure. In 2011, only 3.7% of adults held a bank account and in 2014 the country counted on only 277 bank offices, with two-thirds of them concentrated in Kinshasa and Katanga provinces (Deloitte Reference Deloitte2017). What all of the rural territories have in common are widely dispersed schools and a poorly developed infrastructure, barring some exceptions. Especially during the rainy season, particular areas remain almost unreachable by car. There is also knowledge about schools’ locations which exists only locally: for instance, network administrators clearly know where their schools are located and how to get there, but this knowledge has not been made accessible to providers. It doesn't sound like a good idea, in those circumstances, not to include the school network administrators in the planning of the reform and to presume that the banking network would be able to supplant the school networks in reaching out to all individual teachers. It is also difficult to understand this error of omission as part of a geopolitical strategy; even though the bancarisation reform eventually strengthened the regime by further entrenching territorial unevenness, this was rather the unintended effect of a more complex causal chain.

BANKS’ INITIAL STRATEGIES TO COVER THE COUNTRYSIDE

At this point, we narrow our focus to salary payments in six predominantly rural territories in the province of Haut-Katanga: Kambove, Kasenga, Kipushi, Mitwaba, Pweto and Sakania (see Figure 1). The interesting feature of Haut-Katanga is that, besides Kinshasa itself, it is the province most endowed with bank branches. Six urban areas had at least one bank (Kasumbalesa, Kilwa, Likasi, Lubumbashi, Pweto, Sakania). Here, most teachers collected their salary in the nearest bank branch. Yet, as we will see, this does not mean the problem of distance does not exist in Haut-Katanga. Banks had several ways to cope with the distance between themselves and teachers: setting up payment points, sub-contracting mobile phone companies, sub-contracting other service providers, making teachers travel to banks.

Figure 1 Average distances from school to payment locations in 2014 per territory (SECOPE proposal). Compiled based on SECOPE's proposal for reassigning schools to points of payment (DRC/MoE/SECOPE 2014).

First, banks could set up temporary payment points. In Lubumbashi, for instance, Ecobank set up a temporary payment office: The bank schedules the payment days in advance and communicates this to the schools. However, such schemes are frequently disrupted which obliges teachers to return to Lubumbashi several days later, each time leaving their classes behind. Reasons for these disruptions can either be attributed to banks’ poor organisation, or to teachers not respecting the schedules: teachers are keen on withdrawing their salaries as quickly as possible, due to either financial necessity – teachers are poorly paid and need cash – or a lack of trust in the banking system. Moreover, the conditions under which payments are processed are harsh: payments take place manually without debit cards, in small rooms, during hot weather; a mass of people, surrounded by policemen and soldiers who likewise withdraw their salaries and who are often prioritised.

A second option was to sub-contract the mobile phone companies Airtel and Tigo. This is a well-known practice in other countries (World Bank 2010: 20). Banks opened accounts for teachers and received the normal monthly government payment of US $3.5 per client of which they transferred US $1.2–2 to the phone companies for their operations. The latter saw the bancarisation as a huge opportunity to kick-start mobile money agents in the DRC. The mobile money phenomenon has been most successful in Kenya, whereas penetration in DRC is still very low. In theory, once teachers received their salary, the companies would send an SMS to teachers who could then move to a cash point to withdraw their salary. Teachers would only need their phones, a SIM card from the provider and a password to make a transaction or withdraw money. Inscription would be uncomplicated as only an identity card and an inscription document would be required – yet things turned out differently in reality.

In the case of the Kambove territory, for instance, Ecobank turned to Tigo to cover the rural regions. Tigo, however, had poor coverage in Kambove and mobile money was rarely used. Therefore, teachers hardly ever received notifications when money was transferred to their account and had difficulties withdrawing the money that they urgently needed. In general, they did not desire mobile money but wanted to cash it in as soon as possible. The network of Tigo payment points wasn't sufficiently resourced or organised to provide this service. In general, criticism of mobile phone companies was reportedly widespread at the time (KongoTimes! 2013; Brandt Reference Brandt2014). Moreover, Tigo and Airtel paid slightly later than banks as the money first had to be transferred from banks to their accounts. Furthermore, the companies assumed that everyone possesses and knows how to use a phone; they did not have time for a test period. Even if teachers had a phone, they now needed a SIM card from the respective provider. As reported in Jeune Afrique (2013), the person responsible for these operations at Tigo complained that ‘mobile phone companies were tricked’. As confirmed in an interview with a senior Tigo manager (15.12.2015), they were only asked to participate in the reform at the last minute, and could only accept the most rural areas, as banks had already distributed urban areas between themselves. Instead of starting with an analysis of local capacities, contracts were given in Kinshasa. Perhaps the following letter to the Provincial Governor of the Central Bank, written by 24 teachers of Kafubu, located just 20 km from Lubumbashi, tells it all:

Since Airtel has taken care of our payments, severe delays have taken place and we regretfully observe these manoeuvres: belated payment of salaries, often two or three weeks after our colleagues from other places; payments during night hours, sometimes by the local SECOPE representative …, while the provider AIRTEL is absent … Given all the grievances that we enumerated above, we … make some propositions to solve these difficulties. Mainly: Realising the bancarisation efforts …

Because of all of these shortcomings and their poor performance, Airtel and Tigo largely dropped out of the market in Haut-Katanga.

A third option for banks to cover rural areas was to sub-contract the company Groupe Service (GS) that offers to carry out a range of services, from cleaning to transporting money. GS is comparable to banks’ payment points and phone companies, in that it pays teachers individually and sets up payment points for three or four days. It has been reported multiple times, however, that teachers arrived at a given location when GS had already left. Further, the use of GS only partly solves the problem of distance, as villagers still have to travel quite some distance to the nearest GS payment point. Another important disadvantage of these private parties is that they are not under direct government supervision. The banks themselves directly sub-contract them, without mediation or the involvement of government agencies. SECOPE staff do not have any information about them, except that which teachers report and what they observe on paydays.

Though some of these solutions are reassemblings and reworkings that involved new organisations or ways of working, none of these strategies question the essence of the bancarisation, namely that teachers’ pay is deposited in an individual bank account. This means that, in principle, they have to go to the bank or to a point of payment themselves.Footnote 1 Given the problems described – lack of bank branches, payment points set up for only a few days, etc. –this logic means that teachers have to travel long distances to withdraw their salaries. In the next section, we provide national-level data for this negative side-effect of the reform and we will argue that these distances have caused another reassembling of the way that bancarisation was made to work – or not.

NEGATIVE IMPACT IN RURAL AREAS

The adopted procedure turns thousands of teachers into collateral damage of an operation that should have been implemented gradually. It should have taken into account the actual socio-economic, geographical and infrastructural context of the DRC. (KongoTimes! 2013)

What did the situation look like after a few years of implementation? Figure 1 shows the average distance between schools and the nearest point of payment (whether a proper bank or simply a point of payment), one year after the reform's implementation in rural areas. To be sure, given the very different types of physical infrastructure (quality of roads, means of transportation, etc.), distance is not a fully accurate measurement of the length and inconveniences of a journey. Further to this, we composed the map in Figure 1 on the basis of a proposal by SECOPE to reduce distances. For these reasons, the map shows a rather optimistic view of the actual situation and distances in reality can be expected to be larger than this map suggests.

These data underline the extent to which the idea to overcome the problem of uneven state infrastructural power by counting on the banking network involved a leap of imagination: Most teachers had to walk or cycle at least 5–15 kms, but for about one-third this distance extended to more than 15, and up to 85 kms. The territories with points of payment within a distance of 5 km were really exceptional. For example, in the conflict-affected territory of Pweto (Province of Haut-Katanga), one agglomeration lies 70 km away from the nearest bank, with roads in a very poor condition. Teachers cross this distance on bikes most of the time. Moreover, they often have to wait for several days in Pweto. The longest distance from a school to the bank was around 300 km according to an educational administrator – which underlines the optimistic nature of the Figure 1 map. In some cases, teachers need two days to arrive and two days to return by bike. Not even considering the physical stress on an (ageing) teaching workforce, this alone means four days of absence from the classroom. Furthermore, huge transaction costs of up to 50% of the monthly salary occurred as teachers needed to pay for travel, food and sometimes shelter. The bank BIC/FBN, which was assigned to Pweto, decided explicitly not to offer the service to bring salaries to the teachers. As reported by an employee of BIC/FBN: ‘There are obviously access problems for the teachers living far away from the city of Pweto, but there are no mobile counters. We have evaluated that this is too dangerous, especially surrounding this city.’ (Int. 21.1.2015).

Whereas before, the faith-based school networks were responsible for payment and thereby solved an important collective action problem in transporting salaries, all teachers now had to actually bridge the distances to the point of payment individually. If, before the bancarisation, the real cost of disbursing salaries could be estimated at 5%, the transaction costs charged by the banks already exceeded this cost.Footnote 2

In the next section, we deepen our understanding of the way in which the reform was reassembled, including by actors initially side-lined by the reform.

‘SAVING’ THE REFORM

In order to document more precisely how the bancarisation reform in rural Haut-Katanga was reassembled ‘from outside’ during its implementation, we again look at the six rural territories in Haut-Katanga combined with national-level data. All rural territories under study have their own history of bancarisation, i.e. their own dynamics of reassembling. Here, we focus on the most important commonalities: the opting-in of a Catholic NGO and the invention of a new institution. All of this helped to maintain the discourse on the success of bancarisation, yet also helped to bend the rules of the game in actual practice.

Returning to pre-existing practices: Caritas

Subject: Request to assign teachers to payment by Caritas …

This is why, Mister President in charge of monitoring payments, … we beg you with tears in the eyes for your long-awaited assistance that would not only relieve us, but that would allow us to properly follow the national [educational] program in our classrooms. (Letter written by an educational coordinator of Sakania to the Commission de la Paie in Kinshasa)

As it became increasingly obvious that banks and sub-contractors did not deliver a good service in rural areas, the national government turned to a well-known organisation: the Catholic NGO Caritas. In August 2013, four months after the celebrated start of bancarisation in the interior provinces, Caritas was officially requested by the government to step in and pay teachers in so-called régions à accès difficile (regions with difficult access) (Protocol d'accord from 11 August 2011). The inability of banks to assure proper payments created an ‘open moment’ (Lund Reference Lund1998) and Caritas stepped in. This is the moment when the reform's overall objective to realise a complete bancarisation was abandoned, or at least temporarily deferred.

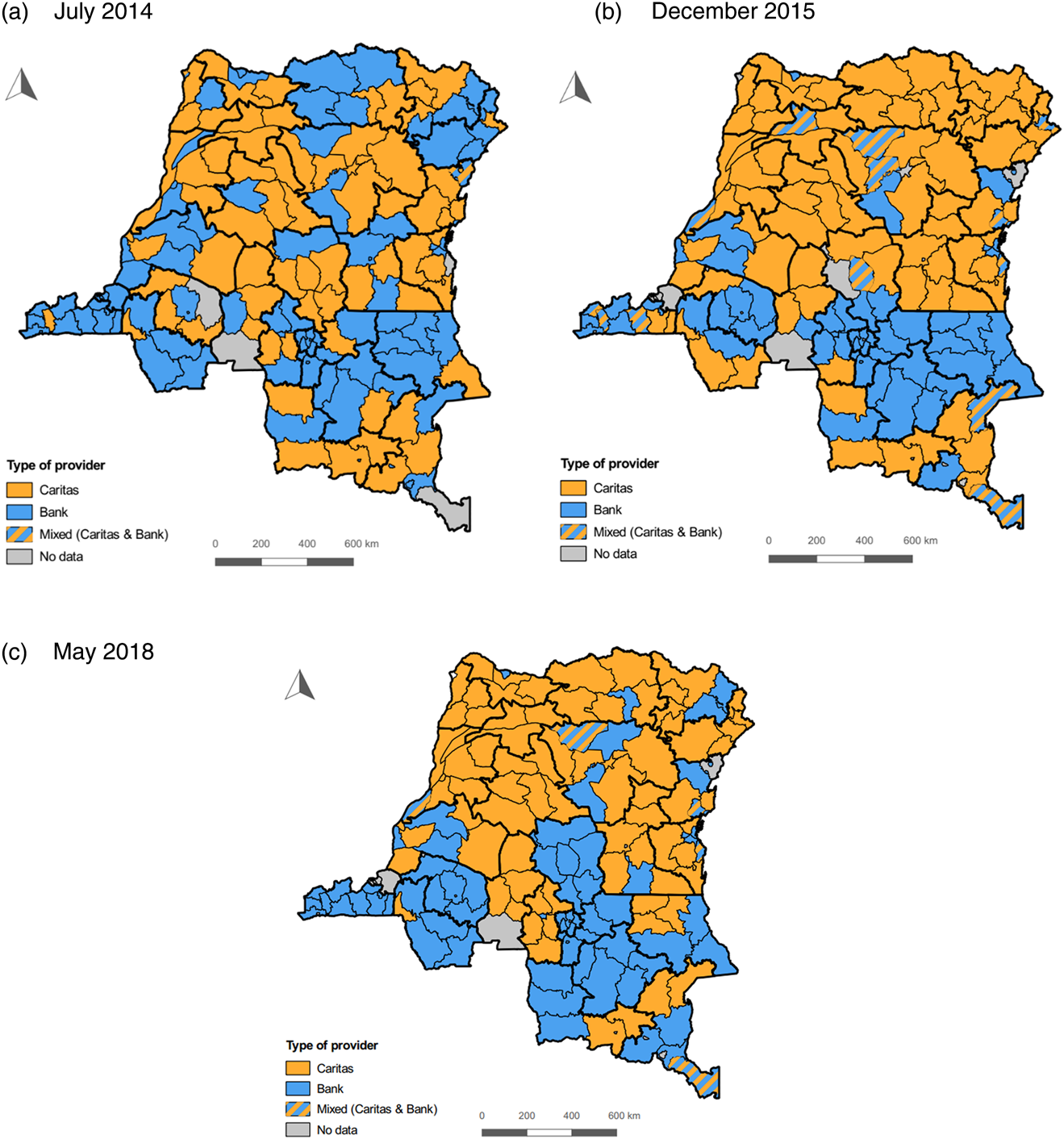

Figure 2 and Table I reconstitute how the territorial composition of providers evolved between July 2014 and May 2018.Footnote 3 In fact, the composition has changed drastically since the launch of bancarisation in 2011. While, in mid-2013, Caritas took over a third of all teachers, by the end of 2015 it assured payment for almost half of them. Almost the whole interior was taken over by Caritas, except some parts which are mainly situated in the West (Kongo-Central, Kwango, Kwilu), South-Center (around Kasai Orientale) and South-East (Haut-Lomami, Tanganyika).Footnote 4 Caritas has paid teachers in four of the six rural territories in Haut-Katanga since the reform was initiated. It is important to note that Caritas’ take-over has not been a neat and tidy process. Instead, it has been tinkered with and negotiated. For instance, as mentioned above, teachers in Kasenga went from Airtel (May–July) to Groupe Service (August and September 2013) to Caritas (October 2013–September 2014) to Groupe Service (October 2014–November 2014) and finally back to Caritas in December 2014. The third map, representing the situation in May 2018, suggests that the situation has more or less stabilised since December 2015, however. This has also been confirmed by a senior manager of Caritas in May 2018, who claims that about 130,000 teachers, or one-third of all teachers on the state's payroll, are currently paid by his organisation.

Figure 2 Territorial division between banks and Caritas. Based on SECOPE's monthly overviews.

Table I Allocation of territories between banks and Caritas, 2014–2018.

Source: Own calculations, based on data from DRC/MinFinance/Ordonnateur Délégué et de L'Ordonnancement (2014).

To explain Caritas’ take-over, we can first of all refer to its own symbolic and infrastructural resources. Caritas had already paid Catholic teachers prior to the bancarisation reform. In 2011, a bill was passed, modifying an existing one, to allow Caritas to act as payment operator for all Catholic schools.Footnote 5 In 2015, Caritas managed a salary portfolio amounting to 182% of the one it managed in 2012 (Caritas Congo 2012, 2016): it was already a key player in distributing teacher salaries before the bancarisation, but – before its return – was replaced due to the government's plan to bancarise all teachers. Caritas was also able to draw on symbolic capital for its involvement: by referring to the convention signed by the Catholic Church in 1977, Caritas drew on the recognition of the Catholic Church as a school administrator. Caritas did not negotiate as an outsider, but as a member of the Catholic Church (Bashimutu Reference Bashimutu2012: 43). Thus, it gave new meaning to its role in the ‘pastoral apostolate’, the social service in the name of the Church for the good of the people (Interview with senior Caritas administrators, 18.12.2015). It could thus claim that it had a no profit-orientation and that it acted as part of a wider legitimising framework.

This brings us to Caritas’ infrastructural power – its ‘capacity to implement political decisions throughout the realm’ (Mann Reference Mann1984: 189). A Caritas employee responsible for the salary payments made the spatial dimension of this power even more explicit: ‘we cover every square metre of the territory of the DRC’ (Int. 19.9.2013). Not only does every diocese have a Caritas office, but every church, priest or car affiliated to the Catholic Church can potentially be mobilised by Caritas. What has been a major challenge for banks and phone companies is the biggest advantage for Caritas: the infrastructure of the territories and the respective presence of banking vs. Catholic institutions. In contrast to banks and phone companies, the national director of Caritas can claim that his organisation travels to the schools or at least as far as the nearest Catholic parish.

To be sure, our field research shows that this claim should be nuanced. Caritas’ biggest advantage, and the banks’ and phone companies’ biggest disadvantage, is in fact that Caritas is not required to pay teachers individually. It has the freedom to pay according to the schools’ lists instead of respecting the banks’ lists. This mechanism allows teachers and principals to be more flexible when it comes to reallocating salaries among themselves, for example that a new teacher receives the salary instead of a deceased one. Sometimes network managers or priests are mobilised too. They meet Caritas staff at certain road junctures, pick up the money for several schools and pay teachers personally or hand cash to principals. At the time of the study, some zones were still considered insecure by Caritas, and teachers were required to come to the locations chosen by Caritas. Similar to the BIC/FBN bank, teachers would have to travel over 70 km. Compensations for travel costs were inconsistent and seemed to decrease over time. In this sense, the Caritas system replicates the pre-bancarisation system, as well as the problems of salary deductions that the bancarisation reform was meant to solve. Still, the territorial reach of Caritas is unequalled in the DRC, neither by banks, and still less by the DRC state itself.

Caritas has another way to deal with the problem of insecurity. A letter issued by the diocesan Caritas office of Kilwa-Kasenga suggests an appropriate answer. The letter is from March 2016, issued by Caritas’ pay commission and written for the territories of Pweto and Kasenga. All principals who act as mediators between Caritas and several schools in their networks were addressed (chefs d'antenne scolaires (tous réseaux confondus)). The pay commission argues that the Congolese government does not offer any insurance on the funds that Caritas manages and delivers. Pointing to mounting insecurity and reported robberies in the DRC, Caritas argues that it would not be able to cover any occurring losses. Therefore, Caritas suggests a collective liability, asking every teacher to sign the following clause:

We, teachers of … accept that Caritas’ payment commission continues to deliver our salaries at our school. In case of losing salaries, due to robbery by armed bandits, we will accept the consequences and we will not seek legal means against the diocese of Kilwa-Kasenga.

Unless all teachers sign, Caritas states (or threatens) that it would consider it necessary to return payment to the government. The question for us is not whether this is a fair arrangement. What is more interesting for the purpose of this article is how such a local arrangement adds paradoxically both to the persistence of the reform, and to Caritas’ increased role therein.

Indeed, despite possible deductions from their salaries, and despite the absence of assurance in the case of theft or robbery, the payment system organised by Caritas seems more beneficial to teachers as it liberates most of them from long-distance journeys. However, these advantages for teachers do not cohere with the government's proclaimed objective of a bancarisation rate of 100%. The majority of all teachers in Haut-Katanga were paid by Caritas in 2016, they were not bancarised.

Should we therefore conclude that the reform failed? Quite the contrary. Caritas’ re-involvement took place under the umbrella of bancarisation. This already sustains one of our initial arguments: a reform is not imposed from the top and resisted at the bottom. Especially in the polycentric governance system of the DRC, non-state actors can complement the state's, or other non-state actors’, activities. More importantly, the Catholic bishops only considered Caritas as a temporary solution, while they were envisaging a new Catholic provider of financial services.

Inventing a new institution

Encouraged by the government, the National Congolese Episcopal Conference founded the microfinance institution (MFI) Institution Financière pour les Œuvres du Développement, Société Anonyme (IFOD S.A.; Financial Institution for Development Projects). This is a new legal entity that draws on the symbolic and infrastructural resources of the Catholic Church. For the government, this was literally deus ex machina: despite lacking banking infrastructure, hundreds of thousands of teachers would become bancarised and the bancarisation ratio would in effect reach 100%. In order to comply with the legal requirements of an MFI and with the government's objective of knowing the actual teaching workforce, IFOD needs to identify each individual teacher.

According to an interview with IFOD's technical manager in May 2018, the MFI uses fingerprints to identify clients and its teams are equipped with tablets to manage payments (Int. 16.3.18). According to this manager, IFOD successfully identified 80% of its clients. Another senior manager claimed a rate of 95% (Int. 15.5.18). For any payment, each teacher needs to present him-/herself individually. Apparently, collective payments are no longer possible and procurement no longer accepted. IFOD claims that the government pays an insufficient sum (3% of the payroll managed by IFOD) to allow the MFI to reach all schools. Therefore, payments continue to follow the geographic logic of the Catholic Church: each of the approximately 1500 parishes define areas that group several schools (axes de paie) which form the basis of IFOD's portfolio. While IFOD's teams also sometimes stop to disburse salaries along the way, most teachers have to travel to the parishes. We were however unable to confirm IFOD's actual reach through fieldwork.

Although IFOD is officially a private company, a senior manager unknowingly repeated the words uttered by a Caritas employee in 2015: ‘IFOD is still the Church’. Reportedly, Caritas staff involved in the payment of salaries received further training and now work for IFOD. As of June 2018, IFOD only had a branch in Kinshasa but was planning to extend its network to other cities.

CONCLUSION

In this article, we analysed the governance, spatial and infrastructural challenges involved in a large-scale administrative reform (bancarisation) that targeted the entire Congolese civil service. The bancarisation reform sought to extend the state's territorial reach by paying all 400,000 teachers individually via bank accounts. This scheme was intended to establish a reliable payroll and to shorten delays in the payment of teachers’ salaries. However, the reform designers were unable to draw on an autonomous knowledge base and at the same time excluded knowledgeable educational stakeholders. Moreover, the reform was built on an idealised and modern image of reality: the presence of banks in the country and of banks willing to quickly expand their services to under-served areas – neither of which was the case in reality. Therefore, we considered this reform in light of the state's limited infrastructural power and other actors’ capacity to complement it.

We showed that the public-private partnership with the banking sector was rather successful in big urban areas, where the imagined infrastructural endowments more or less matched actual endowments. In contrast, the reform in small cities and rural areas was frequently interrupted and incomplete. Given the emphasis in the literature on reform failure, the vastness of the Congolese territory and the relative absence of material infrastructure, one would have expected the bancarisation reform to meet a quick end – which it did not. The answer to this puzzling observation is that on one hand, the official discourse celebrated bancarisation as a major political success, while on the other hand actors initially side-lined by the reform succeeded in reassembling it.

When banks struggled to deliver salaries to rural areas, teachers had no choice but to travel long distances to receive their salaries. For these teachers, bancarisation meant a substantially increased investment in time and money to access their salary, while somehow trying to make up for the resulting lack of time and energy in their classrooms. This devastating situation led to the inclusion of the Catholic Church, which was able to capitalise on its existing infrastructure. Through its NGO Caritas, it considerably expanded its portfolio of teacher payment activities in rural areas, under the umbrella of bancarisation. Furthermore, the Catholic Church bought into the reform's image through the invention of the microfinance institution IFOD. In other words, in the final analysis, rather than improving the state's ability to reach out to all teachers and improve on their working conditions, the reform's effect was to decrease leakage and delays in the payment of teachers in the big cities and to increase transaction costs for teachers everywhere else. In this way, the working conditions of teachers worsened precisely in those areas where the need for additional investment in schooling is highest.

At a more general level, the unfolding of the reform points not only to enormous spatial disparities in the territorial reach of the state but also in the political processes at work in shaping infrastructural power. As noted by Boone, the pace and localisation of this process is determined by the social topography of sub-national power structures (Boone Reference Boone2012: 627). The case of the bancarisation reform further shows to what extent the outcome of this process is shaped by non-state interests and manoeuvres rather than by the state's own geopolitical strategy. Especially in a negotiated system of governance, a reform is not implemented in a top-down manner and resisted at the bottom, but might survive in an unstable process of complaints, modifications and power struggles, as a polycentric ‘geographical assemblage of distributed authority in which power is continually negotiated and renegotiated’ (Allen & Cochrane Reference Allen and Cochrane2010: 1076). As a result, in the absence of appropriate infrastructural endowments, a reform with the goal of replacing one mode of governance (faith-based channels for salary disbursements) with a ‘modern’ one can instead cause a spatially differentiated governance pattern – banks in urban areas, faith-based actors in rural areas – and thereby render a transparent governance process more difficult.

Within this understanding, policy success is the absence of institutionalised contestation or public acknowledgment of failure – which is not the same as the realisation of the state's intended outcomes. We do not suggest that government actors were actively constructing policy success. However, they were operating in a field of political practices that is itself also (spatially) uneven. With Michael Mann, we could conceive of this unevenness as the strength of despotic power. But with Boone and Li, we might also see this political field, where problems are diagnosed and solutions are provided, as itself patterned by evolving spatially uneven practices.