Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 January 2006

This study examines the co-construction of five successful gatekeeping encounters. Drawing from a database of employment interviews, the emically derived concept of trustworthiness is identified as a key determiner in the success or failure of job candidates. Three critical, potentially problematic moves are identified: supplying inappropriate references, demanding too high a salary, and failing to account for gaps in one's work history. What distinguishes the successful from the failed interviews is not the frequency of these potentially damaging occurrences but the compensatory characteristics of those encounters in which trust (and subsequent success) is established. The successful candidates vary widely in terms of second language ability (in the case of nonnative speakers of English) and work experience. What they share, however, is the ability to present themselves positively, to establish rapport/solidarity with their interlocutor, and to demonstrate flexibility regarding job requirements and preferences. Both linguistic and nonlinguistic features are examined.I am grateful to Gabriele Kasper and Claire Kramsch, who provided me with numerous critical and insightful comments on earlier versions of this article. The data analyzed here come from the database that was used for my dissertation research (2001). Attempts have been made to reflect the constructive, and much appreciated, criticisms of two insightful anonymous reviewers of an earlier version of this article.

Gatekeeping encounters, as defined by Schiffrin (1994:146), “are asymmetric speech situations during which a person who represents a social institution seeks to gain information about the lives, beliefs, and practices of people outside of that institution in order to warrant the granting of an institutional privilege.” Numerous studies of institutional discourse and intercultural pragmatics have taken as their setting gatekeeping situations, including academic counseling (Erickson & Shultz 1982, Fiksdal 1990), professor-student advising sessions (Bardovi-Harlig & Hartford 1993), protective order interviews (Trinch 2001, Trinch & Berk-Seligson 2002), and job interviews (Erickson 1979; Gumperz 1982a, 1982b, 1992). In some gatekeeping encounters, the gatekeeper serves as the ultimate authority figure who judges, often severely, the gatekeepee's adequacy (e.g., in citizenship interviews), whereas in others, the gatekeepers may also act to a certain degree on behalf of their gatekeepees, as their advocates – for example, in protective order interviews (Trinch 2001) and academic counseling sessions (Erickson & Shultz 1982). One reason they have received wide attention is that failed gatekeeping encounters can have serious consequences for the participants (Gumperz 1992; Kerekes 2001, 2003), and these are often attributed to miscommunication on the basis of interlocutors' different discourse systems, which may reflect cultural, ethnic, educational, or ideological differences (Erickson 1979, Akinnaso & Ajirotutu 1982, Gumperz 1982a, Roberts et al. 1992). As stated by Gumperz (1992:326), in instances of miscommunication, “candidates and interviewers rely on different, taken-for-granted rhetorical strategies and as a result seem unable to negotiate shared understandings about matters that are crucial to the interview's success.”

In seeking ways to alleviate potential miscommunication in gatekeeping encounters, it has been argued that, just as differences can lead to trouble, similarities, or “shared linguistic and cultural backgrounds[,] will normally enhance mutual understanding between interviewer and interviewee and thus promote the latter's success in the interview” (Akinnaso & Ajirotutu 1982:128). Much of what influences people's perceptions of one another's speaking styles in job interviews is not merely the speech itself, but the expectations people have of one another (Gumperz 1982a). Speakers rely on their socially generated values and beliefs about their worlds to produce and interpret discourse (Fairclough 1989, Maryns & Blommaert 2002).

Gumperz's seminal work on intercultural gatekeeping encounters, which has undoubtedly shaped the field of interactional sociolinguistics (Gumperz et al. 1991, Gumperz 1992), attributes much miscommunication to cultural mismatches. His work has received criticism, however, for taking into consideration only observable, situational factors (i.e., contextualization cues) that influence interlocutors' interpretations (Sarangi 1994, Shea 1994). While Gumperz's work emphasizes the importance of the actual verbal interactions and situations in which they occur, other scholars address the greater context – or “pretext” (as termed by Hinnenkamp 1991, cited in Meeuwis 1994:402) – which includes structural parameters such as power dynamics, inequality, and prejudice (Meeuwis 1994, Shea 1994, Maryns & Blommaert 2002). Critics warn that relying only on Gumperz's approach can result in stereotypes as damaging as those Gumperz seeks to alleviate, by offering explanations for miscommunication on the basis of stereotype-influenced interpretations. Within ethnic groups or any other type of group, individuals vary in their ways of speaking, sometimes in predictable ways and sometimes not. Individuals within cultures are too diverse for it to be possible to attribute miscommunication to cultural differences without taking into consideration individual characteristics of the interlocutors as well as the interactions they (together) build (Shea 1994, Shi-xu 1994). Gumperz's notion of contextualization provides tremendous insights into how understanding – or misunderstanding – is co-constructed in gatekeeping encounters. Verbal interaction between two interlocutors, no matter how successful (i.e., whether or not the intended meaning is clearly communicated), is the joint product of the interlocutors involved.

The database of employment interviews from which the following case studies are taken (Kerekes 2001) supports the notion that achieving a successful gatekeeping encounter – one whose outcome is agreeable to both participants – is far more complex than a mere matching up of interlocutors' similar cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Forty-eight job candidates' interviews were observed, video-recorded, and transcribed. Although the staffing supervisors (the interviewers) in the study represented a socially and linguistically homogeneous group (European American,1

In descriptions of the participants in this study, “European American” and “White” are used interchangeably. Similarly, “African American” and “Black” are used interchangeably.

These descriptors characterize three of the four staffing supervisors, who conducted 47 of the 48 job interviews in the study; the fourth staffing supervisor, from whom only one job interview was obtained for this study, was a Latina, native English-speaking woman in her mid-twenties; that interview is not one of the cases discussed in this article.

I propose in the following discussion that, although diverse speakers can and do achieve successful gatekeeping encounters in a myriad of diverse manners, they also have key commonalities. In examining speakers of different genders, L1s, and ethnicities, we will find many different interactional styles. But, by using a discourse analytical approach to examine authentic, successful gatekeeping encounters, we can also identify features that they share, and that are critical to their success. Two of these features in particular often coincide: establishing comembership, and establishing trust (as defined below) between the staffing supervisor and job candidate.

Comembership first received attention from Erickson & Shultz 1982 in their study of academic counseling sessions. They demonstrated that, through small talk during their counseling sessions, some of the students and their counselors were able to discover their common ground and subsequently establish comembership, “an aspect of performed social identity that involves particularistic attributes of status shared by the counselor and student – for example, race and ethnicity, sex, interest in football, graduation from the same high school, acquaintance with the same individual” (Erickson & Shultz 1982:17).

Successful NNS and NS job candidates in the five employment interview cases I will discuss resemble each other in key ways, though not necessarily in their linguistic or cultural backgrounds. All five establish themselves as trustworthy job candidates, as described by their interviewers. In addition, although they each make potentially problematic moves during their interviews, they also exhibit compensatory characteristics: Their positive self-presentation (knowing when, and when not, to offer self-praise and to elaborate upon questions they are asked by their interviewers), solidarity and rapport they build with their interlocutors, and flexibility they exhibit regarding work conditions compensate for errors that would (and do, for other job candidates) otherwise result in failed gatekeeping encounters.

Trust and comembership, if not always co-occurring, appear to be linked in their emergence in the data discussed below. Closely related to comembership is conversational rapport, the building of which is “a way of establishing connections … Emphasis is placed on displaying similarities and matching experiences” between interlocutors (Tannen 1990b:77). Rapport is an indirect way of “getting one's way not because one demanded it (power) but because the other person wanted the same thing (solidarity)” (Tannen 1993:173). It is thus in the interest of a job candidate to establish rapport with the job interviewer in order to get her or his “way” – in order to get the job.

The establishment of rapport depends, however, on both interlocutors. It takes cooperation and, as such, is co-constructed. Similarly, trust – as well as its opposite – is co-constructed (White & Burgoon 2001, Weber & Carter 2003). In their qualitative interview-based study of the meaning of trust, Weber & Carter identify the following factors which determine the potential for establishing trust in initial encounters: The interlocutors' predispositions (whether or not they possess a “trusting impulse”), their appearance (including facial expressions), their respective personalities (e.g., how friendly they are), points of reference (each individual's reputation), and their behavior during the interaction itself all contribute to the establishment of trust, defined by Rotter 1971 as an “expectancy held by an individual or a group that the word, promise, verbal or written statement of another individual or a group can be relied on” (as cited in Wright & Sharp 1979:73). While trust has thus been investigated and operationalized in social-psychological studies such as those mentioned above, it is also a common term and concept used in everyday English as well as in institutional discourse. For the purposes of this study, therefore, the term “trust,” or “trustworthiness,” will be used as defined by the participants themselves.

The cases I will discuss here are taken from a larger study of employment interviews which took place at a northern California branch of FastEmp (a pseudonym), a national employment agency with more than 200 offices across the United States. I collected data over a 14-month period during which I observed and participated in the everyday office activities of the company. Introduced to the job candidates as an observer assisting FastEmp staff to improve their interviewing procedures, I sat in on 47 job interviews and video- and audio-taped them (with the candidates' consent). Subsequent to each observation, I conducted follow-up interviews with the job candidates, in which I collected biographical information as well as their reflections on their job interviews. After each job interview I observed, I also carried out debriefing interviews with the staffing supervisors to ascertain their assessments of the candidates.3

A total of 48 job candidates participated in the study, but one of them, a Vietnamese immigrant, had an abridged job interview (which was not video-taped) because the staffing supervisor scheduled to interview him judged his English skills to be too weak to qualify him for work; data from my follow-up interview with him and my debriefing interview with the staffing supervisor who assessed him were, however, included in the study.

The job candidates in this study were divided equally between females (24) and males (24), clerical (24) and light industrial candidates (24),4

Clerical positions range from basic filing to executive administrative and word processing assignments; light industrial assignments include manufacturing, shipping and receiving, machine operation, and food handling.

In my analysis of the employment interviews and the interlocutors' interactions, the concepts of trust and distrust emerged as determining factors in the final (successful or failed) outcomes of their encounters. The emically derived concept of trust came from the staffing supervisors' hiring strategies, as described in their discussions about the candidates, and from their interviews with me throughout data collection. Those candidates the staffing supervisors trusted are described (in the staffing supervisors' words) as “sincere,” “honest,” “reliable,” and “trustworthy.” Trustworthiness, as explained by one staffing supervisor, “is demonstrated by them keeping an appointment, being here on time, giving us a follow-up call after a couple of days of not hearing from us…. Reliability is a big one in the temporary industry…. So, reliability, friendliness, honesty, and … follow-through.” In the words of another staffing supervisor, trustworthy job candidates can be identified during the employment interview by “looking for a sense … that they really want to be there, not that they're just y'know doing it because they just think it's funny or y'know whatever. I really look for their, how sincere they are, how serious they are, how dedicated they seem to be, their work history.”

Although trustworthiness was not a precondition for employment at FastEmp, all of the eight candidates the staffing supervisors explicitly identified as trustworthy did achieve successful employment interviews, as determined by the fact that they were either placed on an assignment immediately or categorized in the FastEmp database as available for placement. Correspondingly, six other candidates were described explicitly by the staffing supervisors as not being trustworthy; in their words, they were “misleading,” “dishonest,” “insincere,” and “not credible.” These candidates consistently failed their gatekeeping encounters, regardless of their job-related skills (e.g., number of years of experience on similar assignments, possession of specialized skills sought for particular jobs, professional references); thus, they were deemed ineligible for employment with FastEmp. Of the six untrustworthy job candidates, five were male and one was female5

Gender biases and stereotypes of women as being more easily trusted than men (Wright & Sharp 1979) may also have something to do with this outcome. See also Kerekes 2005 for a discussion of the relationship between social factors such as race and gender and trustworthiness.

The likelihood that the unequal distribution of untrustworthy candidates (overrepresented among light industrial, male candidates) is not coincidental is examined in depth in Kerekes 2005, and is well supported by Erickson & Shultz's (1982) theory of comembership and Gee's (1996) concept of Discourse (with a capital “D”).

Race, education, gender, job type, and language background of individual trustworthy and untrustworthy job candidates.

Compiled characteristics of trustworthy and untrustworthy job candidates.

Three phenomena in particular were cited by the staffing supervisors as reasons that they did not trust, and therefore could not hire, a number of job candidates. The first of these was the job candidates' use of inappropriate references: The “Professional/Work References” section of the FastEmp job application instructs candidates to “[l]ist three references that are not related to you who have knowledge of your skill level.” Despite these relatively unspecific instructions, what the staffing supervisors expect to see in this space are the names of candidates' previous employers and supervisors. A number of the candidates provided the names of their personal friends or co-workers, however.

The following excerpt from an interview between Martin and Amy demonstrates this problem. Martin is an African American (NS of English) male job candidate for light industrial work, in his late thirties; he graduated from high school and completed a number of community college courses in a variety of fields. He was interviewed by Amy, a European American female staffing supervisor who completed her bachelor's degree in journalism and is in her mid-twenties. Martin arrived for his interview on time, looking well-groomed in casual attire and carrying a briefcase which he placed on the table during the interview. He faced Amy, leaning forward with his forearms on the table.

The problem of Martin's having listed inappropriate references is solved when Amy refers to another section of his application on which he has listed contact information for previous employers; Martin agrees that Amy may contact one of them. Nevertheless, for many reasons, including Martin's having interpreted “references” to mean “friends” (other reasons are illustrated below), Amy assesses Martin as untrustworthy and ineligible for placement at FastEmp.7

The case of Martin and Amy is described in more detail in Kerekes 2003, which analyzes the establishment of distrust between these interlocutors.

Martin's interview also illustrates the second phenomenon that damaged the trustworthiness of job candidates, as perceived by the staffing supervisors: Although he filled in the “desired salary” section of his application truthfully, his answer was not one that Amy wanted to see, because she felt he was demanding an unreasonably high salary in relation to the types of jobs FastEmp could offer him. This issue is discussed at length in Kerekes 2003, but we shall see in this article how requesting an inappropriately high salary is an example of errors that can be committed but also compensated for in successful job interviews, as illustrated in the case of Roxana below.

The third phenomenon commonly cited by staffing supervisors as a reason for not trusting job candidates occurred when the candidates were asked to describe their work histories, and they left time gaps in their accounts. The following excerpt from Patty's interview with Amy demonstrates this problem. Patty is a European American female NS candidate for light industrial work, in her forties. At her job interview she wore a formal dress (highly unusual for a light industrial candidate), sat forward with her hand on the table, and often leaned forward to point to things on her application, which lay on the table in front of Amy. Throughout the interview, as Patty sat forward in her chair, Amy sat back in her chair and occasionally looked up at her skeptically.

Amy found Patty's written application difficult to decipher, and she was not convinced by Patty's verbal explanation of it. Amy stated to me:

She had a lot of gaps that she couldn't account for or at least had strange reasons why she wasn't working. I didn't find her very credible at this point … huge gaps that just don't set right with me…. She seemed very nervous, um, also um, I don't know, not, just not very believable like she didn't understand the things I was asking and was just giving me whatever answer came to her mind.

The foundation for the cases of distrust for both Patty and Martin lay in impressions based on messages communicated to the staffing supervisors not only through their verbal interactions during the job interviews, but also through their job applications and the preconceived notions the staffing supervisors had about these candidates. Both Martin's and Patty's written applications served as visual signals to Amy to rouse her suspicions: Martin's for having a higher than acceptable dollar amount in his desired salary box, and Patty's for apparently having gaps of time between jobs for which she had not accounted.

We shall now see how some of the same factors apparent on the written job applications and during the job interviews – inappropriate references, inappropriately high desired salary, and gaps in employment history – can be perceived very differently by the staffing supervisors, resulting in a trusting relationship and a successful job interview. In fact, these three phenomena are equally present among both successful job candidates and among those who failed their interviews. Each of the following cases demonstrates different ways in which the candidates establish trust. Although they have diverse linguistic backgrounds and commit potentially grave errors in their gatekeeping encounters, other features of their interactions serve to compensate for the errors, so that these candidates establish trust with the staffing supervisors and achieve success. These candidates have been able to provide the kinds of explanations and/or to establish comembership/rapport with the staffing supervisors (and consequently not need to provide explanations), so that they are given the benefit of the doubt for potential weaknesses, in contrast to the candidates who did not establish trust.

Eight of the successful job candidates were described by the staffing supervisors as “trustworthy,” while none of those who failed were. The trustworthy candidates are equally distributed across job type (light industrial and clerical) and gender; two are NNSs and six are NSs; five are European Americans and three are Latinos (see Tables 1 and 2 above). The five cases of trust analyzed here have been chosen because they typify interactions which occurred repeatedly between the staffing supervisors and job candidates who had successful job interviews. These particular cases exhibit the three potentially problematic phenomena discussed above, as well as the compensatory characteristics of flexibility, solidarity and rapport-building, and positive self-presentation.

Linda is a European American NS female candidate for light industrial work, in her mid-twenties, and the mother of three children. She has had one and a half years of college education but is not currently enrolled in school. Linda had taken a short course in a career training program on how to interview for a job before she came to FastEmp looking for work. She told me that she had found the course useful in that it offered specific tips for how to conduct oneself professionally and be prepared to answer tricky questions, such as “What is one of your weaknesses?” Linda arrived for her interview at FastEmp punctually, having already talked with Amy on the telephone. She was dressed casually (wearing a sweatshirt) and sat forward in her chair, facing Amy, nodding and making frequent eye contact with Amy.

The following excerpt from Linda's interview with Amy demonstrates that Amy is not consistently critical of the candidates' ability to provide appropriate references. In this excerpt, we see that Linda provides the names of friends rather than supervisors as professional references, just as Martin did. Here, in contrast to her interview with Martin, Amy overlooks Linda's failure to provide the right kind of references on her application.

In contrast to the more interrogating approach Amy takes with the candidates she does not trust (such as Martin), she does not comment to Linda about the fact that she has used personal friends instead of employers as references. Amy avoids potential conflict over this matter by concisely asking her (lines 1–2), are any of these people your former employers? When Linda replies in the negative (3), Amy immediately turns to the names of the employers she has listed under her “Work History” section, and asks Linda (4), okay, can I call Mavis? In this way she never confronts Linda with her failure to carry out the task correctly (supplying appropriate references in the appropriate space on her application).

In considering why Amy is more lenient with Linda than with some other candidates who fail to provide the expected kinds of professional references, we must examine what Amy already knew before she interviewed Linda. First, Amy had already spoken extensively with Linda on the telephone before her interview. Second, the reason for her having done so was that she had a specific job in mind, which she needed to fill. The information Linda provided Amy over the phone indicated to Amy that she might be a match for that job. When Linda arrived for her interview, she filled out the application, which Amy also saw before she interviewed Linda. Linda had perfect scores on her light industrial tests and got a strong reference; this was indicated by Amy's notation on Linda's application that she had “had no punctuality or attendance problems on her previous job.” Amy's need to fill the position, as well, contributed to her tolerance of Linda's divergence from the expected standard for filling out the job application.

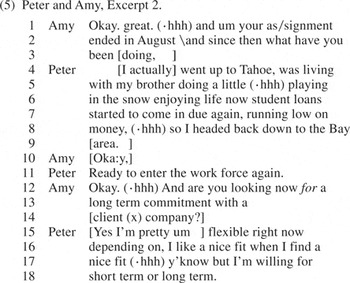

In the next case, we see another successful maneuver around what might otherwise have been a cause of distrust between the interlocutors. Like many of the unsuccessful (failed/weak) candidates, including Patty (above), Peter has indicated a number of gaps between the dates of jobs he has listed on his application. Unlike those who failed their interviews, Peter offers explanations which prove acceptable to Amy. One of the reasons Peter achieves this result is that he has the opportunity to build rapport with Amy before they get to the potentially sticky subject of his employment gaps.

Peter is a European American NS in his thirties. He is the first in his family to get a university education (he has two bachelor's degrees, in psychology and speech communication), and he considers his family working-class – his father was a gardener and his mother was a waitress – or upper-middle-class, when he considers the fact that his parents “moved into a nice neighborhood when it was cheap and now everyone [in the neighborhood] is professional. So they kind of got booted up, but [they are] working class basically.” Peter takes a keen interest in communication (hence his college major), and prides himself in being able to think on his feet and provide satisfactory answers in an interviewing situation.

On the day of his job interview at FastEmp, Peter wore a dark suit with a white shirt and colorful necktie. He sat across the table from Amy, leaning against the back of his chair and sitting still, his left arm folded on the table, nodding frequently in response to Amy's utterances, and making eye contact with Amy whenever she looked up from his application. In this first excerpt, we see that the interlocutors have established a rapport – a level of collaboration and comfort in striking contrast to the job interviews in which distrust was established.

Amy offers encouragement from the beginning, showing high involvement (Tannen 1989, 1990a) by commenting wonderful (line 3) in response to Peter's answer to her question as to where he saw the FastEmp employment advertisement. Peter, in turn, exhibits enthusiasm and cooperation in his following utterances: First, he emphasizes his willingness to work in the locations about which Amy asks, prefacing his answer with definitely (6). Second, rather than simply answering her questions literally, Peter presents himself in a positive light by taking opportunities to volunteer further information about himself and his work interests in ways that highlight his positive characteristics. In lines 9–10, Peter points out that he is not only looking for customer service work, but that he also excels in that sort of work and enjoys it. Here again, Amy responds enthusiastically, with wonderful (11).

Peter continues throughout the interview to volunteer unsolicited, and positive, information about himself, his work experiences and interests. He demonstrates, for example, that his services are desirable by stating that one previous temporary assignment was extended and he was offered a permanent job after another temporary assignment concluded; that he has a variety of computer-related skills; and that, ideally, he wants a job which is a “nice fit” for him. Furthermore, Peter exhibits flexibility regarding the types of work assignments he is willing to take. By the time a potentially sticky topic comes up in their conversation – gaps in Peter's work history – Amy and Peter have established a solid rapport with each other, during which Amy expresses satisfaction with Peter's responses to her questions (through comments of wonderful and great as well as overlapping minimal responses and collaborative completions), and Peter continues to elaborate upon his answers, presenting himself in a way that inspires confidence in Amy that he is a strong job candidate (Ross 1998). Thus, Peter has her on his good side, so to speak, when she asks him about the first gap indicated on his employment history:

Peter explains subsequently that he likes to take temporary assignments specifically so that he can take time off between jobs to enjoy life:

Amy finds these explanations to be credible and acceptable, as she states in her debriefing interview:

I trust his reliability even though he's taken a little bit of a break every time he gets done with a job. He acknowledged that and that's okay, I know that up front. He's not trying to cover it up with anything. So I totally respect that. And I think he communicated that well to me so I think we're definitely going to be able to place him.

What Amy does not state explicitly is that Peter's reasons for taking time off represent values she shares with him. While she may or may not choose to spend her free time in Tahoe, she understands, and can relate to, Peter's desire to travel, his need to pay back student loans, and his wish to find a job that is a good fit. Peter and Amy share their educational backgrounds (bachelor's degrees) and are also of the same race (European American). Furthermore, in a general comment she makes about reasonable (and unreasonable) explanations for taking time off between jobs, Amy states, “A lot of people say ‘Oh we didn't work for five months because I had a trust fund and I wanted to travel.’ ” This is an excuse which she finds acceptable, which she associates with a trustworthy candidate, and which represents values (money, free time, travel) with which she identifies. Other candidates whom she did not find trustworthy had taken time between jobs to look after sick parents or help out a needy family member. Such values and loyalties are less a part of Amy's life experience than are the reasons provided by Peter for taking time off between jobs.

Another way in which successful job candidates – in particular, those deemed trustworthy – relate to their interviewer and get her to identify with them is to disclose facts about themselves not necessarily directly related to their potential employment with FastEmp. This can have an overall effect of personalizing the interaction and building rapport with the staffing supervisor. It also increases the likelihood that the two will find some common ground, thus enabling them to establish comembership, as described by Erickson & Shultz (1982). Talking about private matters which are only peripherally relevant to other topics discussed in the job interview has the effect of getting the staffing supervisor more emotionally involved in the interaction. We see this strategy employed by Liz, a 28-year-old European American NS candidate for clerical work.

Liz was born and raised in the San Francisco Bay area and considers her family to be upper-middle-class. Her father works in upper management for an engineering firm and her mother has retired from her career as an executive secretary. Liz has taken general education courses at a local community college and would like to go back to school simply for the sake of learning, which she enjoys. Her goal is to be a housewife and work on the side, but she expresses this with a bit of discomfort: “Ultimately, um, it sounds silly but ultimately I'd like to be a housewife. I'd like to be a mom. And I'd like to maybe work from home.”

At her job interview, Liz is dressed professionally, wearing a sweater-blazer and slacks, with polished fingernails and styled hair. She sits straight up, forward in her chair, one hand on the table in front of her. Liz makes eye contact with Amy, and offers frequent nods and verbal minimal responses. Although Liz displays two distinct weaknesses in her interview – supplying inappropriate references on her job application, and showing a lack of ability to answer Amy's question about what her strengths are – other qualities of her interview and presentation style compensate for these, allowing her to establish a trusting relationship with Amy and to have a successful interview.

One of the compensating characteristics is the fact that Liz brings up her personal life a number of times during her job interview with Amy. She volunteers information about herself, giving Amy more than a literal (minimal) answer to her questions, in much the same way that Peter did. Rather than simply talking about her employment, Liz also mentions more personal matters, such as the reason that she moved back to the San Francisco Bay area (lines 9–20), including the facts that she is engaged to be married, her fiancé is a chef, and they are renting a room from a friend of hers.

Liz then continues by giving detailed answers to Amy's open-ended questions about her work experiences, supplying unsolicited information about responsibilities she took on at her previous job, and including characterizations which cast her, as an employee, in a positive light:

By the time Liz makes her first mistake – one that cost several other job candidates the opportunity to be employed by FastEmp – she has expressed enthusiasm for working in a variety of environments and in gaining work experience (i.e., flexibility). She has also established rapport with Amy through chit-chat unrelated to the objective of finding a job. Amy then asks Liz about her professional references:

Here we see how, similar to Linda's interview (above) but in striking contrast to Martin's, in Liz's interview Amy exhibits leniency regarding the fact that the references Liz has listed are not her supervisors.

The second area in which Amy exhibits tolerance regards Liz's response to Amy's question about what her strengths are:

Liz's discomfort with Amy's question about her strengths is manifested in a number of ways. First, Liz states, after two seconds of hesitation, that she does not know what her strengths are (5). Amy urges her to provide an answer to the question by countering that she does know (6). Although Liz hedges and hesitates for another long series of seconds (7–10), she eventually proves Amy right by providing an answer to the question, and, in doing so, reveals that she has a good sense of the type of answer Amy seeks: Liz describes herself as a creative, detail-oriented worker who always completes her tasks (12–14). Amy indicates to Liz through her minimal response (15) that she expects Liz to continue, and Liz cooperates by adding to her list of self-descriptors the fact that she is easy to work with (16), although she hedges her entire answer with a concluding I don't know.

By the time the interview draws to a close, Amy is interested enough in Liz as a potential employee that she describes a possible assignment to Liz; it is one she needs to fill immediately. In (11) below, Liz demonstrates where her loyalties lie:

Liz conveys two distinct messages to Amy here. On the one hand, she claims that she is ready to start working immediately (5–7). On the other hand, she wants to be present at the imminent birth of her sister's baby. While Liz successfully conveys to Amy that she is serious about working – she hopes the baby's birth will not affect her job attendance (18–19) – she also openly states that being by her sister's side when she has the baby will take priority over any job she has (26–28). She subsequently assures Amy, however, that she will not be occupied after the baby is born, because the grandmother will be there to help out.

Liz's openness and honesty (as perceived by Amy) about her loyalty to her family work to her advantage in two ways: First, she invokes in Amy an empathic exclamation (10) in response to the news that her sister is expecting a baby. Second, as stated in Amy's debriefing interview, Liz impresses Amy as

professional and serious about her job search. And that's good. I don't think she would have told me yes if she didn't intend on showing up tomorrow. I had a good trust built in her…. So far she seems trustworthy that she's serious about working and I trust that she'll go to the job.

Liz was able to succeed in her interview despite the facts that she provided inappropriate references and set limitations on her availability. With twenty-twenty hindsight, we might advise Amy to heed the warning signs more closely: As it turned out, Liz was placed on an assignment but became an “NSNC” (“no show no call”)8

This label identifies job candidates who fail to appear at an assignment on which they have been placed, without notifying FastEmp or the client company; this label disqualifies them from further employment with FastEmp.

We now turn to two cases of trustworthy and successful job candidates who are NNSs, Roxana and Maria. Both of them were treated differently from their NS counterparts in some ways. For example, Maria's interview was exceptionally short (4.5 minutes, in contrast to the average 12.5 minutes), because her interviewer, Carol, felt Maria's L2 ability was not sufficient for a lengthier, more detailed interview. Roxana's less-than-native proficiency in English was also identified by her interviewer, Amy, as a potential weakness, but not one that would prevent her from being placed on an assignment. Both Maria's and Roxana's interactions with the staffing supervisors resembled those of the trustworthy NS candidates in a number of significant ways.

Roxana is a NNS (Spanish L1) candidate for clerical work, in her mid-thirties. She completed her training to be a kindergarten teacher at a university in Mexico and immigrated to California nine years ago. Now she hopes to get her bachelor's degree and is interested in studying either psychology or computers. She grew up near the border between El Paso, Texas and Juarez, Mexico, and had thought she could speak English before she moved to the United States; upon arrival, however, she discovered that she could not communicate. Therefore, Roxana immediately enrolled in an adult ESL program, and she eventually continued her studies of ESL as well as general education at a local community college, where she received an A.A. degree. Roxana speaks mostly Spanish at home with her spouse and child, but her child speaks fluent English as well. About 90% of her friends are Spanish speakers, and she speaks Spanish in most of her extracurricular activities such as going to church, doing volunteer work, and spending time with her family. She reads mostly in English (self-help and other nonfiction books). Recently, she has been working at a Latino parents' center and speaking mostly Spanish; Roxana therefore feels that “now it's time to get practice [in English], actually to get used to the language again.” During her job interview, Roxana wore glasses and a professional-looking blazer with a low-cut blouse, and her hair covered part of her face. She sat forward with her elbows on the table across from Amy and her hands folded, sometimes in front of her mouth, and other times on the table. Roxana made frequent eye contact with Amy, when Amy looked up from her notes. When the job interview commenced, Amy had already seen Roxana's job application and her test scores. On her application, Roxana had stated that her previous job paid $30/hour. While she did not expect to make as much at FastEmp (and her previous job did not give her health benefits), she stated that her desired salary was $16, which was higher than could reasonably be expected at FastEmp. This became a topic of discussion during her interview with Amy, but did not dissuade Amy (in contrast to Amy's interview with Martin, who also desired a higher salary than he could expect to receive) from considering Roxana for FastEmp assignments. Roxana got perfect scores on all of the clerical tests (arithmetic, filing, proofreading) except for spelling, on which she missed two words out of forty. She also got nearly perfect scores on the computer tests – Microsoft Word, Excel, and PowerPoint.

In this first excerpt, we see that, like Liz, Roxana exhibits a certain amount of flexibility – she is willing to take either a temporary (“temp-to-hire”) or permanent position (lines 6–11) – while also setting some limitations on her flexibility (13–14):

In addition, like Liz, Roxana feels comfortable responding to an open-ended request to describe a previous job, and, like Liz, she begins by saying she was responsible for “everything” (ex. 13, line 3). She then offers a list of tasks which she carried out and summarizes her duties by stating that she was the coordinator's “backup prompt” (8) (similar to Liz, who was her supervisor's “right hand man”):

Roxana knows when to elaborate on her answers, volunteering information at strategic points in the interview. She also knows how to maneuver around Amy's questions in such a way as to offer answers (and/or tangents to the answers) which highlight her strengths. When Amy asks her, for example, how she got her previous job at the Latino Parent Center, Roxana describes how her college counselor had given her name to the employer, who had then called Roxana:

Roxana takes advantage of Amy's question about how she found her job at the Latino Parent Center to show that she is an employee in demand. She did not seek out the position; rather, she was referred to her employer by her counselor, and the employer called her; she did not go knocking on someone's door seeking a job (1–3). Next, Roxana expresses enthusiasm for having an assistant support role, in answer to Amy's question as to whether she likes it (8–12). Then, in her response to Amy's question about what she likes most about the job, she answers by stating that she likes everything about it, and begins to list the elements of the job she likes (14–23). She interjects, however, to offer praise of her own listening skills (17), which, presumably, she sees as connected to the skills she uses on the job. Finally, in answering Amy's question about what she does not like about the job (29), she is able to use her response as another opportunity to present herself in a favorable light: She answers that the only tiny thing she does not like about her job is that some people do not finish their tasks, in which case she will go ahead and do it for them (32–37). Whereas this is an aspect of her job she says she does not like, it is an aspect of her work ethic which is viewed positively by her interviewer, as evidenced in Amy's assessment of her:

I thought she was nice…. She had excellent computer skills and great work history. Very honest, up front with what her intentions were, with her job search and what she wanted and that is good. She seemed to be straight with me.

Despite her positive impression, Amy is not unaware of a potential detrimental effect of Roxana's L2 ability. Amy expresses her awareness of Roxana's language use and feels that her second-language ability will limit her employability for certain jobs requiring extensive telephone work. These limitations do not, however, disqualify Roxana for a number of other opportunities to work for FastEmp:

I think that I would hesitate to put her on a receptionist position. I think that her communication isn't as strong for that type of a role, but other than that, she seemed good.

Looking beyond the verbal interaction itself and at the larger context in which it occurred, a comparison of the two interlocutors – interviewer (Amy) and interviewee (Roxana) – is revealing. The type of work Roxana did at Latino Parent Center had much in common with the type of work Amy does at FastEmp; they require many of the same skills. Both involve communicating with clients, catering to their diverse needs, and carrying out a variety of administrative tasks under time pressure. It is no wonder, then, that Roxana feels comfortable with Amy, who, she states, is “about my own age … and she seems to be very … friendly.” It appears from her assessment that Amy has a similar impression of Roxana; their comembership, while not explicitly stated, is evident to them both.

Maria, in contrast to Roxana, has less in common with her interviewer as far as their career training and experiences are concerned. Nevertheless, Maria also manages to establish some common ground with her interviewer, and, as such, establishes a positive rapport with her. In contrast to Roxana, Maria represents the lower end of L2 ability among the job candidates in this study. A native speaker of Spanish in her thirties, Maria worked in a toy factory in El Salvador doing assembly work before immigrating to the United States in 1985. She did not graduate from high school but attended a secretarial school (in El Salvador) at which she learned typing and shorthand. Maria and her husband rent the house in which they live, and her husband, who has taken some community college courses, makes his living doing landscape work. The mother of four children, Maria is now looking for work and is frustrated that she has failed in her efforts thus far, because every potential employer with whom she has spoken is looking for someone with more work experience than she has.

Maria has had no formal training in English; she learned English from her family and through her other activities in the United States. She has taken some community college classes in child development. Maria feels that her English is “bad” and is eager to improve it. She would like to return to community college, but only to take ESL classes (not to get a degree), focusing on her reading and writing. She states that her husband and older children speak very good English, and they correct her pronunciation when they are with her. She watches television in both English and Spanish and attends a Spanish-speaking church. At home her family uses both English and Spanish, and Maria reports that she speaks both languages with her friends.

Maria's second-language ability, as regards her speech production, represents the low end of the spectrum for job candidates at FastEmp. This is reflected in her grammatical inaccuracies, heavy L1 transfer of Spanish phonological features, and a limited range of vocabulary in her English production. Her L2 comprehension and interlanguage pragmatic skills prove more than adequate, however, for the tasks of answering questions and otherwise responding to her interlocutor in appropriate ways. Maria shows a high level of comprehension as well as a certain level of comfort with the rhythm of her exchange with Carol, her interviewer, not only offering appropriate answers at appropriate times, but also supplying minimal responses and initiating collaborative completions. Analysis of her job interview shows that she is, in fact, able to utilize many skills necessary to persuade her interviewer that she is honest, dedicated, ambitious, reliable, and enthusiastic; in other words, she is trustworthy, and highly employable.

Maria is dressed in slacks and a casual sweater. She sits in her chair across from Carol, often shifting about and/or swiveling as she listens and speaks. Maria successfully communicates her flexibility to Carol in the first excerpt:

Maria is willing to accept either long- or short-term assignments even though she ultimately would like a full-time position (1–8), and she is available to start work immediately (9–11). Moreover, Maria recognizes the fact that she sounds so flexible it could be seen as funny, or perhaps overly eager, or, in any case, somehow requiring laughter in order to lighten the potential face loss of seeming too desperate to get a job. So she laughs (11), and in her next turn shows that she is not universally flexible, since one of her limitations is that she is only willing to take a day shift (13–15). Maria volunteers a reason for this limitation – that she has four children to look after, so it is hard for her to work at night (14–15) – thus exhibiting her awareness that offering an explanation here is legitimate and/or called for. In fact, the reason she offers establishes comembership with Carol and serves to build solidarity between them, as Carol also has children at home. Carol does not tell Maria this fact explicitly, merely looking up, making eye contact with Maria while nodding in agreement and stating that she understands the situation (17–18), after which they laugh simultaneously, in agreement (19–20). Maria also demonstrates her flexibility regarding her desired salary (21–29). In lines 26–29 she draws out her utterance of “seven” and pauses while making dynamic motions with her hands, as though she is trying to get herself to go down yet further, perhaps to six or six-fifty, but then she sticks with seven and indicates she would like to earn at least that amount, by uttering go up in line 29.

Maria's light-hearted and approachable conversational style, as well as her demonstrated flexibility, compensate for her lack of work experience, which becomes apparent in the next excerpt:

What Maria lacks in experience she makes up for with her honesty and enthusiasm. Not only must Maria answer Carol's question (1–2) about whether she has done assembly work in the negative, but she even emphasizes her lack of experience, stating in lines 3–4 that she has never worked in electronics or anything like that (3–4). She takes a different tack with Carol's next question (5–6) about whether she has experience working in a warehouse. This time, rather than directly saying “no,” Maria instead expresses her enthusiasm for wanting to do something different, since her only work experience thus far is working with children (7–9). She appeals to Carol's sympathy by describing her attempt to find work (8–9) to no avail, because she does not have work experience (9–11). At this point both Maria and Carol laugh (presumably at the irony and frustration of this all-too-familiar plight of seeking work without qualifications), and Carol confirms with Maria that her only experience is working with children at the YMCA (12–14). Not dissuaded, however, Carol asks Maria whether she can lift fifty pounds (15–16), a requirement for some of the light industrial positions, to which Maria answers with great enthusiasm (17–19), again accompanying her verbal response with hand movements, indicating her ability to lift and move something heavy.

While Maria's grammar, vocabulary, and accent indicate to Carol that her L2 ability is relatively low, Maria proves to have a high level of communicative competence, resulting in effective interactions between Carol and her. Although they have not had any major communication breakdowns up until this point in the interview, still, in excerpt (17) below Carol utilizes her default strategy of determining whether a NNS candidate's English comprehension is adequate by asking the question, “What are your long-term goals?”

Maria has to ask for clarification twice, in lines 2 and 4, and, while Carol merely repeats the word (as opposed to paraphrasing it or otherwise providing some kind of modified input for Maria), Maria understands after Carol asks her about her goals the third time, and in line 6 indicates her comprehension. Her answer – to look for a good life and good future – satisfies Carol, but Maria further demonstrates her sociopragmatic knowledge regarding when it is appropriate to elaborate, and continues in lines 12–16 to explain why having a good job is important to her: It's terrible when you try to find something and nobody … help you (14–15). Maria appeals to Carol's sympathy and empathy, using generic “you” and relying on the rapport she has already built with Carol.

In her debriefing interview, Carol stated that she “very much liked [Maria] … and thought that she was open and honest.” According to Carol's assessment, Maria can communicate enthusiasm, dedication, ambition, and reliability. This is manifested in her job interview through her agreement to work immediately in a variety of types of jobs. She can comprehend questions and respond appropriately, including clarification requests where necessary. She can build rapport with Carol by sharing personal information about herself with which Carol can identify.

These features of her job interview compensate for several flaws on Maria's written application, which might have caused her trouble had she not been deemed trustworthy. First, Maria failed to write down her educational background (community college courses) on her application. Second, her light industrial test scores were extremely low. She missed nine out of fourteen items in the arithmetic section, and ten out of twelve items in the test of alphabetical filing. She missed three out of nine items in the section on numeric filing, and three out of six items in the proofreading section. For the short-answer questions about safety rules, Maria left two of the five items blank, but gave plausible answers for the other three. For example, her answer to the question, “If you notice unsafe working conditions or practices on a job assignment, you should…” consisted of, “safe shoes we expect suitable dressed.” Maria's written answers, as well as other sections on her job application, such as her work history, manifest her relatively elementary writing skills and poor spelling.

Although Carol's awareness of Maria's L2 ability influences the job interview in a number of ways, it does not cause Carol to assess Maria negatively. Carol states that Maria's English language ability is “fine for understanding safety rules,” a criterion for eligibility for light industrial assignments. Carol feels that Maria's English is adequate for filling assembly positions, but not for assignments involving telephone work. Because of Maria's relatively low level of English, as Carol perceives it, Carol chooses to keep the job interview short and succinct. Carol is persuaded by Maria's extensive experience working at the YMCA that she would be a fine candidate for assembly work, and she feels Maria has a good general work attitude.

Maria's interactional behavior, as exhibited in the transcript of the job interview, provides evidence of her knowledge of the institutional discourse used at FastEmp in a number of ways (as illustrated above). Further evidence of her familiarity with appropriate interviewing behavior is apparent in her answers to my questions during the follow-up interview. In answer to my question of what qualities Maria thought Carol was looking for, for example, Maria readily answered,

In that I have my energy. I like working and working in team where I working alone this is it doesn't matter for me. And … I try to make the challenges that people give me.

Maria thus demonstrates her awareness that the abilities to work cooperatively and energetically are seen as positive characteristics, and she wishes to emphasize these as a job candidate. Furthermore, she exhibits her ambition by trying to meet the challenges she is given.

In sum, it is apparent through the job interview, debriefing interview, and follow-up interview with Maria that she knows how to present herself as a good worker in a job interview. She establishes solidarity with her interlocutor, and, as she tells me in her follow-up interview, she understands Carol easily. She communicates her positive attributes to Carol, so that Carol comes to trust Maria as a solid job candidate and to overlook potential weak points in her application.

In this discussion we have seen examples of job interviews in which trust was established, and which resulted in successful outcomes for the job candidates (i.e., they qualified for job placements with FastEmp). The candidates who achieved relationships of trust with the staffing supervisors varied in many respects – their ages, genders, educational backgrounds, the types of work they sought, qualifications they possessed, their L1, and their English ability. Nevertheless, the interactions in which these candidates engaged had a number of common features. In these interactions, while the candidates did not always produce ideal answers to the staffing supervisors' questions, they still succeeded in satisfying their interviewers, who were apt to give them the benefit of the doubt when they exhibited their weaknesses (e.g., inappropriate references or inadequately prepared answers to questions such as “What are your strengths?”); positive features of the interactions compensated for these inadequacies. Because the candidates exhibited elements of comembership with their interlocutors, established rapport and solidarity with them, demonstrated flexibility in the types of assignments they were willing to take, and presented themselves to their interviewers as positive, competent employees, the staffing supervisors were more forgiving with them than with their untrustworthy counterparts.

One cannot simply attribute these candidates' successful gatekeeping encounters to their job qualifications or to their own verbal and nonverbal behavior, however. It is not merely their behavior that differs from that of the untrustworthy candidates; rather, it is the co-constructed interactions between them and their interlocutors that differ from the co-constructed interactions between the staffing supervisors and candidates deemed untrustworthy. The staffing supervisors appear to be more lenient with the candidates with whom comembership is established. As an interaction becomes more personalized, as through Maria's mentioning her children, Liz's description of her sister's pregnancy, or Peter's interest in spending time in Lake Tahoe, the staffing supervisor relates to her interlocutor more humanely than she does to someone who is represented by nothing but a poorly written application and monosyllabic answers to her grilling questions.

Not all candidates have equal opportunities to establish rapport with the staffing supervisors, however. While the staffing supervisors' impressions of the job candidates are based in part on information obtained during the job interview and in part on information obtained before and/or after the interview, they also possess preconceived notions of job candidate prototypes, as manifested both in the staffing supervisors' interviews with me and in the ways they relate to the candidates during the job interviews. The staffing supervisors have more favorable expectations of the candidates with whom they have more in common and with whom, consequently, they are more likely to establish comembership than with those who are socially very different from them. While, in general, race and gender can play a role in establishing common ground (or lack of it) between interlocutors, we have seen through these examples that in some cases it is quite possible to achieve a relationship of trust even when the uncontrollable social characteristics are not shared by the interlocutors. It is certainly in the interest of vocational trainers, ESL instructors, and their students to focus instruction on features of successful interactions such as those identified in this discussion, but it would also behoove members of the staffing industry to improve communication with their job candidates, jointly, in order to perform more effective job interviews. The effective placement of qualified candidates in appropriate positions can thus also be co-constructed by the participants.

Race, education, gender, job type, and language background of individual trustworthy and untrustworthy job candidates.

Compiled characteristics of trustworthy and untrustworthy job candidates.