There is growing recognition that child externalizing behavior (a constellation of physical aggression, defiance, angry outbursts, hyperactivity, and inattention) develops very early in childhood and that variation among young children's level of externalizing behavior often has long-term consequences. Externalizing behaviors are a normative feature of early childhood, exhibiting a population-wide peak at around 30 months of age and a gradual decrease thereafter, until they increase once more in adolescence (Tremblay, Reference Tremblay2000). Despite externalizing behaviors' commonality, toddlers who exhibit high levels of them are at marked risk for a pattern of stable behavior problems for years to come. This distinct trajectory appears to be in place by 24 months (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network & Arsenio, Reference Arsenio2004; Shaw, Lacourse, & Nagin, Reference Shaw, Lacourse and Nagin2005), and perhaps as early as 17 months (Tremblay et al., Reference Tremblay, Nagin, Séguin, Zoccolillo, Zelazo and Boivin2004). The consequences of early onset, persistently high levels of externalizing behavior are varied and long ranging (e.g., Moffitt, Caspi, Harrington, & Milne, Reference Moffitt, Caspi, Harrington and Milne2002), which is a fact that has given rise to an enormous amount of research aiming to understand its antecedents (e.g., Aguilar, Sroufe, Egeland, & Carlson, Reference Aguilar, Sroufe, Egeland and Carlson2000; Moffitt & Caspi, Reference Moffitt and Caspi2001).

Identifying the antecedents of externalizing behaviors requires the knowledge of when they develop. What has become increasingly clear is that the externalizing behavior construct comes into being at a younger age than had been previously suspected. The groundbreaking findings of Van Zeijl, Mesman, Stolk, et al. (Reference Van Zeijl, Mesman, Stolk, Alink, van IJzendoorn and Bakermans-Kranenburg2006) suggest that externalizing behavior is present in a recognizable form by 12 months. In a normative sample of Dutch families, parents completed the Child Behavior Checklist for 1.5- to 5-year-olds (Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2000). Internal consistencies for the externalizing scale were high and its 1-year stability was 0.45.Footnote 1 In this same sample, approximately 50% of the 12-month-olds exhibited physical aggression (Alink et al., Reference Alink, Mesman, Van Zeijl, Stolk, Juffer and Koot2006). Moreover, as Van Zeijl, Mesman, Stolk, et al. report, 12-month externalizing behavior was associated with several well-known predictors of externalizing behavior, such as authoritarian parenting, parenting daily hassles, marital discord, young maternal age, and the number of siblings. The Dutch findings suggest that by 12 months, the externalizing behavior construct itself behaves like a meaningful dimension of behavior: one that organizes a collection of different behaviors (e.g., hitting, tantruming, and high-activity level), exhibits continuity over time, and is related to constructs in its nomological network. If Van Zeijl, Mesman, Stolk, et al.'s results are correct, researchers who seek to chart the emergence of the externalizing behavior construct must now look to the first year of infant life.

When should one begin to look for evidence of the emergent externalizing behavior construct? If one goes back far enough in infancy, surely its developmental viability breaks down. For example, it would be dubious to speak of externalizing behavior in a 2-month-old infant. If a 2-month-old flails out at a caregiver or screams when restrained, such behaviors are not likely to reflect a stable, coherent pattern of relating to others. The temporal instability of infant behavior in the first 3 months of life is well known, and behavior at this age is thought to be more biologically than psychologically oriented (Bell & Ainsworth, Reference Bell and Ainsworth1972; Denham, Lehman, Moser, & Reeves, Reference Denham, Lehman, Moser and Reeves1995; Emde, Gaensbauer, & Harmon, Reference Emde, Gaensbauer and Harmon1976; Fish, Stifter, & Belsky, Reference Fish, Stifter and Belsky1991; Hubbard & van Ijzendoorn, Reference Hubbard and van IJzendoorn1991; Sameroff, Reference Sameroff1978; Sroufe, Reference Sroufe1996). Yet, if psychologists can relatively easily agree that externalizing behavior in 2-month-olds is doubtful, it would be much harder to gain consensus of when externalizing behavior becomes a developmentally viable construct.

The Developmental Viability of the Infant Externalizing Behavior Construct

Two key developmental advances in the first year of life suggest the possible viability of the externalizing behavior construct prior to 12 months: the presence of anger as early as 2 months and its increase across the first year, and the emergence of physical aggression (e.g., hitting and kicking) by 6 months. Their development, and the development of the underlying externalizing behavior construct itself, may be further catalyzed by the attainment of independent locomotion by 8 months and the markedly increased capacity to generate and recognize goal-directed behavior between 6 and 12 months.

Several studies point to the emergence of anger by as early as 2 months (Lemerise & Dodge, Reference Lemerise, Dodge, Lewis, Haviland-Jones and Barrett2008; Lewis, Reference Lewis, Lewis, Haviland-Jones and Barrett2008). Anger is also closely related to the concept of “irritable distress” described in the temperament literature (Deater-Deckard & Wang, Reference Deater-Deckard, Wang, Zentner and Shiner2012; Rothbart & Bates, Reference Rothbart, Bates, Damon, Lerner and Eisenberg2006).Footnote 2 Anger and irritable distress, which often occur when infants' desires are thwarted by another person's behavior, each show relatively linear population level growth from 4 to 16 months (Braungart-Rieker, Hill-Soderlund, & Karrass, Reference Braungart-Rieker, Hill-Soderlund and Karrass2010; Carnicero, Pérez-López, Del Carmen, & Martínez-Fuentes, Reference Carnicero, Pérez-López, Del Carmen and Martínez-Fuentes2000; Gartstein & Rothbart, Reference Gartstein and Rothbart2003). This increased capacity for anger over the first year of life is influenced by infants' abilities to engage in goal-directed behavior (e.g., “I am trying to reach the toy”) and to recognize it in others (e.g., “She is trying to reach the toy”), capacities that develop rapidly between 6 and 12 months (Tomasello, Carpenter, Call, Behne, & Moll, Reference Tomasello, Carpenter, Call, Behne and Moll2005). Correspondingly, infants become capable of identifying social figures as sources of frustration by 7 months (Izard, Hembree, & Huebner, Reference Izard, Hembree and Huebner1987).

By 6 months, physically aggressive acts make their first appearance. Four studies of physical aggression with normative samples of infants are relevant. Hay et al's (Reference Hay, Perra, Hudson, Waters, Mundy and Phillips2010) findings suggest that hair pulling in particular may be one of the earliest and most common forms of physical aggression; it was reported by more than 70% of mothers of 6-month-old infants. By comparison, biting (10%) and hitting (5%) occurred far less often. In Del Vecchio (Reference Del Vecchio2006), approximately 62% of the mothers of 4- to 11-month-old infants (M = 8 months) reported the presence of biting (39%), kicking (38%), or hitting (15%). Tremblay et al. (Reference Tremblay, Japel, Pérusse, McDuff, Boivin and Zoccolillo1999), using retrospective reports of the parents of 17-month-old children, suggest an onset of pushing, hitting, or kicking at 7 months in about 1% of infants, each increasing in prevalence to as high as 5% (pushing) until 11 months and thereafter increasing sharply. In observations with peers, physical aggression was found in 8% of 9- to 12-month-olds by Hay, Hurst, Waters, and Chadwick (Reference Hay, Hurst, Waters and Chadwick2011).

We adopt the topographic approach advocated by Tremblay (Reference Tremblay2000) in which aggression is defined by the descriptive characteristics of the behavior (e.g., hitting), rather than its intended effect on the target. This approach is contrasted with a cognitive view of aggression that requires intention to harm and/or a kind of means–end calculation about what the impact or instrumental value of the aggressive act is in order to be “truly” considered aggression (e.g., Maccoby, Reference Maccoby1980). The cognitive view precludes one from considering as truly aggressive such behaviors has hitting, pinching, and kicking at 6 months of age because the requisite cognitive abilities develop in later months. However, the cognitive view of aggression yields an unfortunate by-product for scientists who seek to characterize the initial emergence of physical aggression: “If we, a priori, decide that aggressive behaviours cannot exist before a given age we, of course, prevent the falsification of the hypothesis” that they do (Tremblay, Reference Tremblay2000, p. 131) and that they are meaningful (e.g., fit into the nomological network of aggression). More generally, intentionality has been historically elusive in the literature on aggression, even in adults (Bushman & Anderson, Reference Bushman and Anderson2001). Our position is that there is enough evidence to suggest that topographically physically aggressive behaviors emerge in the first year of life and that the meaning of those behaviors is an empirical question that science, including the present article, is just beginning to address.

The attainment of independent locomotion (crawling at an average of 8 months and walking with external supports at an average of 9 months; World Health Organization Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group, 2006) may be a further catalyst for externalizing behavior in the first year. As Thompson (Reference Thompson, Eisenberg, Damon and Lerner2006) points out, the infant has the newly gained ability to wander away from the parent and engage in activities that are viewed by the parent as undesirable. Paired with the infant's rapidly increasing capacity to perform and recognize others' potentially competing goal-directed behavior at this age (Tomasello et al., Reference Tomasello, Carpenter, Call, Behne and Moll2005), challenges of will between parents and infants become more frequent (Biringen, Emde, Campos, & Appelbaum, Reference Biringen, Emde, Campos and Appelbaum1995; Campos et al., Reference Campos, Anderson, Barbu-Roth, Hubbard, Hertenstein and Witherington2000). Correspondingly, infant anger may increase upon achieving independent locomotion (e.g., Campos, Kermoian, & Zumbahlen, Reference Campos, Kermoian, Zumbahlen, Eisenberg and Fabes1992).

Taken together, developmental attainments of anger, physical aggression, the capacity to generate and recognize goal-directed behavior, and independent locomotion point to the second half of the first year as a viable period for the externalizing behavior construct to take shape. The individual aspects of externalizing behavior can be expected to influence one another. To illustrate, if the infant is capable of identifying a parent as the source of her or his frustration, she or he may angrily (i.e., be distressed by limitations) react against her (i.e., aggress) and attempt to pursue his or her own desires despite parental resistance (i.e., defiance). These associations may sharpen upon the attainment of independent locomotion because locomotion increases the chances of conflict between parent and child. Further, the more active the child (i.e., activity level), the more frequent the contests of will with the parent are apt to be as the child moves about his or her environment with vigor and encounters parental limits.

Notwithstanding the research and theory described above, a formal evaluation of the externalizing construct in the first year of infancy has yet to be conducted. The findings of Hay et al. (Reference Hay, Perra, Hudson, Waters, Mundy and Phillips2010), however, are suggestive. These authors hypothesized that infants' contentiousness, or “propensities to engage in conflict with their companions” (p. 351), is a precursor to later externalizing behavior, particularly aggression. In a normative sample of families with 6-month-old infants, contentiousness was measured with a four-item questionnaire reflecting hitting, biting, anger, and tantrums. The items were somewhat internally consistent (mean α = 0.65), and the scale exhibited significant interinformant agreement (rs between .23 and .51) and stability to 12 months (r = .44). In addition, the 6-month contentiousness scores had a small significant association with physical aggression toward peers observed in the laboratory at a staged birthday party at 11 to 15 months. Implicit in Hay et al.'s conceptualization is the notion of transformation: that an earlier behavior (contentiousness) is transformed into a later behavior (aggression), rather than there being a literal continuity in the morphology of the behavior (Shaw & Bell, Reference Shaw and Bell1993; Sroufe, Reference Sroufe2009). This view has been prevalent in the search for temperamental precursors of later externalizing behavior, particularly in combination with environmental liabilities (Bates, Pettit, Dodge, & Ridge, Reference Bates, Pettit, Dodge and Ridge1998; Lorber & Egeland, Reference Lorber and Egeland2011; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Winslow, Owens, Vondra, Cohn and Bell1998). In our view, however, the line between “contentiousness” and “externalizing” is blurry.

The Behavior of the Emergent Externalizing Construct

What might emergent externalizing behavior look like? How might the construct behave? In the previous section, we integrated several lines of evidence and theory to argue in favor of the developmental viability of the externalizing behavior construct in some form by the second half of the first year of life. We theorize that by approximately 6 months, the externalizing construct is present and characterized by the confluence of physical aggression (e.g., pinching or biting), defiance (e.g., persisting with an activity despite parental prohibitions), activity level (e.g., excessive squirming while being bathed), and distress to limitations (e.g., screaming when restrained). We adopt the organizational perspective of Sroufe, Egeland, Carlson, and Collins (Reference Sroufe, Egeland, Carlson and Collins2005) to suggest that it is the pattern of these behaviors with respect to one another, and to context, rather than their mere presence or intensity, that gives meaning to the externalizing construct. The more aggressive the infant, the more defiant, physically active, and angry/distressed we expect the infant to be. Operationally, we hypothesize that these behaviors reflect the influence of a single underlying externalizing construct, although each behavior may have variability that is not shared with the others.

Our conceptualization of infant externalizing behavior bears much similarity with typical operationalizations of toddler and preschool externalizing behavior (e.g., Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2000; Carter, Briggs-Gowan, Jones, & Little, Reference Carter, Briggs-Gowan, Jones and Little2003), yet there are important differences. We theorize that the underlying externalizing behavior construct is consistent across ages, but that its manifestations change: in other words, that it exhibits heterotypic continuity (Patterson, Reference Patterson1993; Sroufe, Reference Sroufe2009). An infant and a toddler may each exhibit a behavior with the same linguistic descriptor, but that does not imply that the behaviors are literally the same. To illustrate, the infant and the toddler may each “kick,” but in different ways and/or in different contexts. Whereas the toddler may walk up to someone and kick that person in a targeted fashion, an infant might kick at his caregiver in a flailing fashion while being diapered.Footnote 3 Similarly, the infant and toddler may each be “defiant,” but the infant's defiance is less likely to be verbal prior to developing the ability to say “no.” Further, the nature of defiance likely changes as a result of normative changes in parental commands and prohibitions. Parents more often attempt to get their 13-month-old infants to stop doing something (i.e., a “don't” command) than to start doing something (i.e., a “do” command), with “do” commands increasing in later months (Gralinski & Kopp, Reference Gralinski and Kopp1993). In addition, activity level becomes supplemented in toddlerhood with ambulation (e.g., running) on top of previously attained active behaviors (e.g., squirming or crawling away). The morphology of distress to limitations may be similar in infancy and toddlerhood, because both infants and toddlers are, for example, capable of fussing, crying, and tantruming. However, we suspect its organization with respect to context changes over time, as the child gradually learns the functional value of negative affect in terminating parental prohibitions.

As an additional difference from typical operationalizations of later externalizing behavior, we do not include in the infant externalizing behavior construct several behaviors that require developmental attainments that occur beyond the first year: impulsivity, inattention, lying/sneakiness, and guiltlessness. Impulsivity and inattention are each related to effortful control, which is typically defined as voluntary regulation of behavior and attention. In their Reference Rothbart, Sheese, Rueda and Posner2011 review, Rothbart, Sheese, Rueda, and Posner concluded that the beginnings of effortful control are seen by 18 to 20 months (e.g., Kim & Kochanska, Reference Kim and Kochanska2012), although some of its building blocks are present in the first year (e.g., orienting). Lying is impossible in the preverbal infant and emerges by about the age of 3 years (Talwar & Lee, Reference Talwar and Lee2002). Sneakiness requires the attainment of theory of mind abilities, which develop in the preschool period (Wellman, Cross, & Watson, Reference Wellman, Cross and Watson2001). Guilt is one of the “self-conscious emotions” that begin to develop in the second year of life (Lewis, Reference Lewis, Lewis, Haviland-Jones and Barrett2008; Sroufe, Reference Sroufe1996).

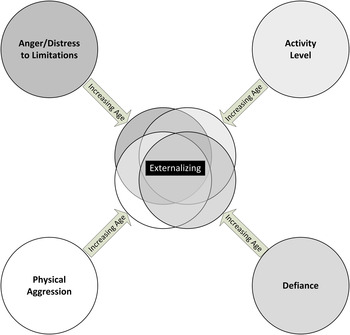

We further theorize that, as the externalizing behavior construct emerges with advancing age, there are increasing correlations among physical aggression, defiance, activity level, and distress to limitations, as well as increasing temporal stability (Figure 1). In other words, with development, externalizing behavior should become increasingly coherent and exhibit increasingly stable differences among children, as hypothesized by Alink et al. (Reference Alink, Mesman, Van Zeijl, Stolk, Juffer and Koot2006). This view is rooted in the dynamic systems and organizational perspectives (Lewis, Reference Lewis2000; Sroufe et al., Reference Sroufe, Egeland, Carlson and Collins2005) in which “[n]ew macroscopic forms and new patterns of microscopic coordination cause one another in self-organizing processes” (Lewis, Reference Lewis2000, p. 39) that become increasingly orderly with development. In general, there is increasing stability of temperament/personality traits with age (Roberts & Del Vecchio, Reference Roberts and Del Vecchio2000). This pattern extends to individual behaviors in the postulated externalizing cluster in the infant/toddler period, with studies showing increasing stability of irritable distress, activity level, aggression, and oppositional behavior (Alink et al., Reference Alink, Mesman, Van Zeijl, Stolk, Juffer and Koot2006; Denham et al., Reference Denham, Lehman, Moser and Reeves1995; Goldsmith & Rothbart, Reference Goldsmith, Rothbart, Strelau and Angleitner1991; Pedlow, Sanson, Prior, & Oberklaid, Reference Pedlow, Sanson, Prior and Oberklaid1993; Van Zeijl, Mesman, Stolk, et al., Reference Van Zeijl, Mesman, Stolk, Alink, van IJzendoorn and Bakermans-Kranenburg2006).

Figure 1. (Color online) The developing externalizing behavior construct. Increasing associations among physical aggression, defiance, anger/distress to limitations, and activity level with increasing child age.

We further theorize that, if infant externalizing behavior is a valid construct, it should show theoretically coherent associations with other constructs in its nomological network. A voluminous body of literature and numerous theoretical models suggest that high levels of early externalizing behaviors are associated with problems in the parent–child and interparental relationships, including such factors as harsh treatment by parents, impaired parent–child bonding, and interparental conflict (Gershoff, Reference Gershoff2002; Kitzmann, Gaylord, Holt, & Kenny, Reference Kitzmann, Gaylord, Holt and Kenny2003; Rothbaum & Weisz, Reference Rothbaum and Weisz1994). Moreover, research with infants suggests that unsupportive family environments are associated with higher levels of irritable distress and physical aggression between 6 and 12 months (Fish et al., Reference Fish, Stifter and Belsky1991; Lorber & Egeland, Reference Lorber and Egeland2011; Mehall, Spinrad, Eisenberg, & Gaertner, Reference Mehall, Spinrad, Eisenberg and Gaertner2009; Towe-Goodman, Stifter, Mills-Koonce, & Granger, Reference Towe-Goodman, Stifter, Mills-Koonce and Granger2012; van den Bloom & Hoeksma, Reference van den Bloom and Hoeksma1994; Van Zeijl, Mesman, Stolk, et al., Reference Van Zeijl, Mesman, Stolk, Alink, van IJzendoorn and Bakermans-Kranenburg2006). Sociodemographic factors such as low family income and young parental age are also associated with more early childhood externalizing behavior (e.g., Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Lacourse and Nagin2005; Tremblay et al., Reference Tremblay, Nagin, Séguin, Zoccolillo, Zelazo and Boivin2004), including those measured in infancy (Hay, Mundy, et al., Reference Hay, Mundy, Roberts, Carta, Waters and Perra2011; Van Zeijl, Mesman, Stolk, et al., Reference Van Zeijl, Mesman, Stolk, Alink, van IJzendoorn and Bakermans-Kranenburg2006).

The Present Investigation

The present investigation was undertaken to evaluate the developmental viability of the externalizing behavior construct in infancy. We first probed the viability of the externalizing construct at 8 months. We hypothesized that physical aggression, defiance, distress to limitations, and activity level would reflect a single latent externalizing behavior construct (Hypothesis 1). We further hypothesized that the externalizing construct, as well as its individual indicators, would exhibit at least somewhat stable variation over time, reflected in longitudinal rank-order stability (Hypothesis 2), become more strongly associated with one another (Hypothesis 3), and exhibit increased rank-order stability with advancing age (Hypothesis 4). Hypotheses 2–4 were evaluated at 8, 15, and 24 months. In the last stage, we investigated the association of infant externalizing behavior with factors in its nomological network. We hypothesized that more externalizing behavior would show concurrent and predictive associations with interparental conflict (e.g., physical aggression), poor parental bond with the infant, harsh parenting (e.g., physical discipline), as well as parents' young ages and low family income (Hypotheses 5a–e, respectively).

Method

Participants

The study participants included in the present report were 274 couples of neonates (140 girls, 134 boys) recruited at two hospital maternity wards in the suburbs of a large American city. They were a subset of a sample of 378 couples recruited for a randomized controlled trial evaluating the effects of a modified version of Couple CARE for Parents intervention for preventing intimate partner violence (Halford, Petch, & Creedy, Reference Halford, Petch and Creedy2010). To be included in the parent study, couples must have been English-speaking cohabiting parents of a neonate with at least one parent under age 30 and who reported at least one of four common manifestations of intimate psychological aggression (shouting/yelling, insults/swearing at, stomping out of the house in anger, and doing things to spite the partner), but no physical aggression that resulted in injuries and/or fear.

The study parents included in the present report were couples (64% married) with at least one parent completing at least one of the assessments on which the present analyses are based (8, 15, and 24 months). The study parents (M age = 26.72, SD = 3.80 for mothers and M age 29.23, SD = 5.24 for fathers) had between 1 and 6 (M = 1.75) children and had been living together for 5.46 years on average. Median annual family income was $56,000 (interquartile range = $30,000 to $94,000); the median family income in the participants' county of residence was $99,474 in the US Census 2007–2011 American Community Survey. A minority had college degrees (40.1% of mothers and 33.5% of fathers). Mothers described themselves as Black or Caribbean (14.4%), Latina (17.8%), White (61.1%), Asian (4.4%), or mixed race (2.2%). Fathers described themselves as Black or Caribbean (17.4%), Latino (24.8%), White (52.2%), Asian (2.6%), Native American (1.1%), mixed race (1.5%), or Pacific Islander (0.4%).

All measures included in the present report came from assessments at 8, 15, and 24 months. Accordingly, the couples included in the present report were those that completed at least one of these assessments. They were compared with couples who dropped out on length of their relationship, family income, number of children, marital status, whether the pregnancy of the study child was planned, as well as mothers' and fathers' ages, educational levels, and race/ethnicity. Of these 9 comparisons, 2 were significant. Couples who dropped out were more likely to be unmarried, χ2 (1) = 7.96, p = .005, and have a father with only a high school education/GED or less, χ2 (1) = 4.18, p = .041.

Procedure

The study couples were assessed within 3 months of childbirth (M = 1.14, SD = .81), and then again at approximately 8 (M = 8.44, SD = 1.33), 15 (M = 15.26, SD = 1.04), and 24 (M = 24.78, SD = 2.22) months of child age. At each assessment, the mothers and fathers independently completed a battery of questionnaires assessing child behavior and multiple aspects of their couple and parent–child relationships. At the end of the initial assessment, couples were randomly assigned to receive the modified Couple CARE for Parents intervention or waitlisted until child age 24 months. The seven-session intervention was completed prior to the 8-month assessment. The intervention is not a focus of the present manuscript and is described in Slep et al. (Reference Slep, Heyman, Mitnick, Lorber, Xu and Niolon2014) and Halford et al. (Reference Halford, Petch and Creedy2010).

Measures

Child physical aggression and defiance

Parents completed the Infant Externalizing Questionnaire (IEQ) at each wave of assessment. The IEQ is a measure of aggression and defiance developed by our research group, with its psychometrics reported in Lorber, Del Vecchio, and Slep (Reference Lorber, Del Vecchio and Slep2014), who studied the same sample. The IEQ contains a six-item physical aggression and a three-item defiance subscale. The physical aggression items are “kicks people,” “pushes people,” “hits or smacks people,” “bites people,” “pulls people's hair,” and “pinches or scratches people.” The defiance items are “keeps playing w/ objects when told to leave alone,” “keeps going when told to stop,” and “keeps doing things after adult tried to stop.” Each item is rated as 0 = not at all true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, or 2 = very true or often true.

IEQ items are purely descriptive, reflecting the topography of behaviors.Footnote 4 They were influenced by those of existing measures of early childhood externalizing behavior (Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2000; Tremblay et al., Reference Tremblay, Japel, Pérusse, McDuff, Boivin and Zoccolillo1999) and Bates's temperamental resistance to control measure (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Pettit, Dodge and Ridge1998). We carefully considered the developmental relevance of each item to ensure that they were behaviorally feasible in infants as young as 8 months of age. Qualifications were made where developmentally necessary (e.g., biting, not including nursing, and even if the baby has no teeth). Defiance was limited to nonverbal behaviors given the limited expressive vocabulary of infants. Per the rationale described in the Introduction, the defiance subscale items were written to reflect the child's defiance in failing to comply with “don't do” commands.

Internal consistency was acceptable for the physical aggression (mother mean α = 0.74, father mean α = 0.75) and defiance (mean αs = 0.78) subscales, averaged across all time points. Item averages were computed for each subscale separately for mothers and fathers. Mothers' and fathers' scores were subsequently averaged to form a couple-level composite of physical aggression and defiance at each time point. Mother–father agreement across all time points averaged 0.45 for physical aggression and 0.30 for defiance; the coefficients are standardized covariances from latent variable models presented in Lorber, Del Vecchio, et al. (Reference Lorber, Del Vecchio and Slep2014).

Child activity level and distress to limitations

The Revised Infant Behavior Questionnaire (IBQ-R) is a parent-report measure of children's temperament (Gartstein & Rothbart, Reference Gartstein and Rothbart2003). The activity level (15 items; e.g., “When placed on his/her back, how often did the baby squirm and/or turn body?”) and distress to limitations (16 items; e.g., “How often during the last week did the baby protest being placed in a confining place [infant seat, play pen, car seat, etc.]?”) subscales were administered at each wave of assessment.

At 8 and 15 months, both IBQ-R subscales were given in their original format. At 24 months, the original formatted distress to limitations scale was given, along with a slightly modified activity level scale. The IBQ-R is designed to apply to infants from 3 to 12 months old. Consequently, some of the activity level items are clearly not applicable to 24-month-olds. Thus, the following minor changes were made: references to “crib” were replaced with “crib or bed,” references to “infant seat or car seat” were replaced with “infant seat, high chair, or car seat,” and “roll away” was changed to “get away.” The Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire (Putnam, Gartstein, & Rothbart, Reference Putnam, Gartstein and Rothbart2006) is the parallel measure designed for toddlers. We decided against its use due to our desire to measure activity level and distress to limitations in as similar a manner as possible across all three waves of assessment.

Internal consistency was acceptable for the activity level (mother mean α = 0.82, father mean α = 0.81) and distress to limitations (mother mean α = 0.82, father mean α = 0.80) subscales, averaged across all time points. Item averages were computed for each subscale separately for mothers and fathers. Mothers' and fathers' scores were subsequently averaged to form a couple-level composite of activity level and distress to limitations at each time point. Mother–father agreement across all time points averaged 0.24 for activity level and 0.41 for distress to limitations; the coefficients are standardized covariances from a saturated covariance model.

Couple conflict

Couple conflict was operationalized by latent composites of physical and psychological aggression and couple relationship satisfaction.

Physical and psychological partner aggression

Parents completed the 78-item Conflict Tactics Scale—II (CTS-II; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, Reference Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy and Sugarman1996) at each wave of assessment. The CTS-II is a widely used measure of psychological and physical aggression in couples, and its scores consistently correlate with several factors in the nomlogical network of couple aggression (O'Leary, Slep, & O'Leary, Reference O'Leary, Slep and O'Leary2007). It assesses the perpetration of (reports of aggressing against one's partner) and victimization by (reports of one's partner's aggression) aggression during the last year through frequencies ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (more than 20 times). For each partner, item averages were calculated for the 8-item psychological aggression subscale items (e.g., “called partner fat or ugly”) and the 12-item physical aggression subscale items (e.g., “pushed or shoved”). The respondent's victimization scores were averaged with her or his partner's perpetration scores to yield dual-informant total psychological and physical aggression scores for each person. Mothers' and fathers' psychological and physical aggression scores were further averaged to form couple-level physical and psychological aggression scores for analysis.

CTS-II items are built to range from less to more extreme aggression, rather than sampling the aggression construct with a number of related items. Thus, the alpha is not reported.

Couple relationship satisfaction

Parents completed the 30-item Couples Satisfaction Index (Funk & Rogge, Reference Funk and Rogge2007) at each wave of assessment. The Couples Satisfaction Index correlates highly with several other validated measures of relationship satisfaction, but Funk and Rogge's item response theory analyses showed it to be considerably more sensitive than its alternatives. All but 1 of its items (e.g., “How often do you wish you hadn't gotten into this relationship?”) are scored from 0 to 5 (one item is scored from 0 to 6), with different sets of anchors for its eight clusters of items. The sum was computed for each parent, and mothers' and fathers' scores were further averaged to form couple-level relationship satisfactions scores for analysis. Higher scores indicate greater couple level satisfaction. The mean α was 0.97 for men and women, averaged across all time points.

Latent couple conflict factors

The couple-level psychological partner aggression, physical partner aggression, and relationship satisfaction scores described above were treated as indicators of a latent couple conflict factor at their corresponding wave of assessment. All factor loadings (mean absolute standardized loading = 0.63) were significant at p < .001.

Harsh parenting

Harsh parenting was operationalized by latent composites of overreactive discipline and physical and psychological parent–child aggression.

Overreactive discipline

A 12-item version of the Parenting Scale (Arnold, O'Leary, Wolff, & Acker, Reference Arnold, O'Leary, Wolff and Acker1993), a measure of harsh/overreactive and lax/permissive discipline practices, was administered at the 15- and 24-month assessments. The Parenting Scale was validated against child behavior problems, home observations of parenting, and couple relationship satisfaction and has recently been validated with item response theory (Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, O'Leary, Wolff and Acker1993; Lorber, Xu, Slep, Bulling, & O'Leary, Reference Lorber, Xu, Slep, Bulling and O'Leary2014). Item averages from a 5-item version of the overreactivity scale (e.g., “When my child misbehaves, I get so frustrated or angry that my child can see I'm upset”) were the present focus. Internal consistency was marginally acceptable for mothers (mean α = 0.64) and fathers (mean α = 0.61), averaged across the 15- and 24-month assessments. Mothers' and fathers' overreactivity scores were subsequently averaged to form couple-level overreactivity scores for analysis.

Parent–child aggression

The 22-item Parent–Child Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS-PC; Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, Reference Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore and Runyan1998), a measure of physically and psychologically aggressive parenting practices, was completed at each wave. CTS-PC scores consistently correlate with several factors in the nomological network of parent–child aggression (Slep & O'Leary, Reference Slep and O'Leary2007). Items are rated from 0 (never) to 6 (more than 20 times) during the past 12 months. Physical aggression (13 items; e.g., “slapped on head, face, or ears”) and psychological aggression (5 items; e.g., “called child dumb”) subscale item averages were computed for each parent. Mothers' and fathers' physical and psychological parent–child aggression scores were subsequently averaged to form couple-level physical and psychological aggression scores for analysis.

CTS-PC items are built to range from less to more extreme aggression, rather than sampling the aggression construct with a number of related items. Thus, the alpha is not reported.

Latent harsh parenting factors

At 8 months, the couple-level psychological and physical aggression scores described above were treated as indicators of a latent harsh parenting factor. The factor loadings (M = 0.91) were significant at p < .001. At 15 and 24 months, overreactivity was added as an additional indicator of the construct. The factor loadings (M = 0.67) were significant at p < .001.

Parent–infant bonding problems

Parent–child bonding problems was operationalized by a latent composite of three measures of parent–infant bonding at 8 months.

Parent–Infant Attachment Scale (PAS)

The PAS (Condon & Corkindale, Reference Condon and Corkindale1998) is a 29-item scale measuring the emotional bond experienced by the parent toward the infant, administered to each parent at 8 months. PAS items are rated on multiple 4- to 5-point Likert type response scales (e.g., “When I am with the baby, I always get a lot of enjoyment/satisfaction”). Total PAS scores, across its pleasure in proximity, acceptance, tolerance, and competence subscales, were calculated for each parent by averaging all items on the questionnaire. Internal consistency was acceptable for mothers and fathers (αs = 0.77). Mothers' and fathers' PAS scores were subsequently averaged to form a couple-level score for analysis.

Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire (PBQ)

The 24-item PBQ (Brockington, Fraser, & Wilson, Reference Brockington, Fraser and Wilson2006) was completed at 8 months. It is designed to detect parent–infant relationship disorders (e.g., rejection of the infant). In Brockington et al., it distinguished mothers with and without parent–infant relationship disorders diagnosed by clinical interview. Items (e.g., “I wish my baby would somehow go away”) are rated from 1 (always) to 6 (never). In the present study, an item average score across the PBQ's four subscales (impaired bonding, rejection/anger, anxiety, and incipient abuse) was computed for mothers and fathers (αs = 0.81). These scores were subsequently averaged to form a couple-level PBQ parent–infant bonding score for analysis.

Mother to Infant Bonding Scale (MBS)

The MBS (Taylor, Atkins, Kumar, Adams, & Glover, Reference Taylor, Atkins, Kumar, Adams and Glover2005) is a brief measure of parents' negatively and positively valenced thoughts about and feelings toward their babies administered to each parent at child age 8 months. Its eight items are adjectives that are to be completed with reference to the parents' feelings about the child (e.g., “joyful,” “resentful,” “protective”; rated from 1 = very much to 4 = not at all). Taylor et al. reported that MBS scores are associated with maternal depression and show longitudinal stability from 3 days to 12 weeks. In the present study, the instructions were altered to refer to the parents' feelings toward the child in the “last few weeks” rather than “the first few weeks” as in the original version. Internal consistency was acceptable for mothers and fathers (αs = 0.77). Item averages were computed for each parent. Mothers' and fathers' MBS scores were subsequently averaged to form a couple-level score for analysis.

Latent parent–child bonding problems factor

The couple-level PBQ, MBS, and PAS scores were treated as indicators of a latent bonding problems factor at 8 months. All factor loadings (mean absolute standardized loading = 0.63) were significant at p < .001. Higher scores indicate bonding problems.

Results

Descriptive statistics for each of the above measures are found in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for study measures

Note: PBQ, Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire; MBS, Mother to Infant Bonding Scale; PAS, Parent–Infant Attachment Scale.

The factor structure of externalizing behavior

The factor structure of externalizing behavior was evaluated via confirmatory factor analysis in a structural equation modeling framework, with the robust maximum likelihood estimator and missing data handled via the full information maximum likelihood method. The manifest variables were standardized prior to analysis in order to allow covariance comparisons (see Hypothesis 3 and 4 below) that did not conflate strength of association with the amount of variance in the manifest variables. Model descriptions and fit are presented in Table 2. In Model 1, mother/father report averages of physical aggression, defiance, activity level, and distress to limitations at each of the three waves of assessment were used as indicators of latent externalizing behavior constructs at 8, 15, and 24 months. The variances of each latent factor and the residual variances were each set to 1. Covariances were allowed among each of the latent externalizing variables. Model 1 was a poor fit to the data.

Table 2. Model fit

Note: The χ2 is Satorra–Bentler scaled (robust) χ2; CFI, comparative fit index; TLI, Tucker–Lewis fit index; RMSEA, root mean square error approximation; CFA, confirmatory factor analysis.

aModels 4 and 1 fit significantly worse than does Model 2.

Based on modification indices, several residual covariances were allowed in Model 2, which adequately fit the data. Model 2's fit was superior to that of Model 1, χ2change (7) = 158.60, p < .001. Ordinary χ2 difference tests cannot be computed with the Satorra–Bentler scaled (robust) χ2. Thus, χ2 differences in model fit were tested per Satorra and Bentler (Reference Satorra and Bentler2001). Five residual covariances that were added reflected the fact that there was stability in indicators that was not explained by the stabilities of their corresponding latent externalizing factors: physical aggression (15 with 24 months), activity level (8 with 15 months), defiance (15 with 24 months), and distress to limitations (8 and 15 with 24 months). Two additional residual covariances that were added reflected unexplained variation between indicators: physical aggression with defiance at 8 months, and 15-month distress to limitations with 24-month activity level.

The Model 2 confirmatory factor analysis, which supports Hypothesis 1, is depicted in Figure 2. All factor loadings were significant at p < .001, with the exception of the 8-month loading of defiance (p = .025). The standardized loadings ranged from 0.21 to 0.85 (M = 0.57). Consistent with Hypothesis 2, externalizing behavior exhibited significant longitudinal stability, ranging from 0.70 to 0.82 among the three time points, ps < .001.

Figure 2. The factor structure of externalizing behavior at 8, 15, and 24 months of age (Model 2). All factor loadings are significant at p ≤ .025.

Do individual externalizing behaviors become more interrelated with age?

Evidence to support the hypothesis of increasingly strong associations among physical aggression, defiance, activity level, and distress to limitations with advancing child age (Hypothesis 3) could come from two interrelated sources: (a) increasing covariances among these variables, and (b) changes in the factor structure of externalizing behavior, with increases in these variables' loadings.

Comparisons of the covariances among indicators

Three of the six associations among physical aggression, defiance, activity level, and distress to limitations significantly strengthened with age, in accord with Hypothesis 3. A series of model comparisons were computed with the key covariance pairs (e.g., the association of aggression and defiance at 8 vs. 15 months) constrained to be equal versus freely estimated. A baseline model (Model 3) was estimated allowing covariances among physical aggression, defiance, activity level, and distress to limitations at all ages. Because this is a saturated covariance model, there are zero degrees of freedom and it is not suited for comparisons. To yield positive degrees of freedom, a randomly assigned subject identifier variable was added to the covariance matrix, but it was not allowed to correlate with any other variable. Model 3 adequately fit the data. Next, alternative models were constructed with each key covariance pair constrained to be equal. Significant decrements in model fit would indicate that the key covariance pairs differed. The equality of each key covariance pair was evaluated independently in a series of df = 1 χ2change tests; the p values from these tests are reported below.

Compared to their associations at 8 months, the defiance–activity level and defiance–distress to limitations associations were stronger at 15 (respective ps = .013 and .029) and 24 months (respective ps = .001 and .034; Table 3). The physical aggression–activity level association was also stronger at 24 than at 8 months (p = .033). There was also marginally significant evidence that the activity level–distress to limitations association was stronger at 15 (p = .072) and 24 months (p = .058) than at 8 months. None of the correlations among physical aggression, defiance, activity level, and distress to limitations significantly strengthened between 15 and 24 months.

Table 3. Do individual externalizing behaviors become more interrelated with age?

Note: Coefficients are standardized covariances evaluated with robust standard errors.

aCovariances at 8 and 24 months are significantly different.

bCovariances at 8 and 15 months are significantly different.

Change in the factor structure externalizing behavior

The factorial invariance of the externalizing construct was investigated via imposing several constraints on the factor loadings over time. In Meredith's (Reference Meredith1993) terminology, weak factorial invariance would be satisfied if the loadings of each behavior on the externalizing construct did not significantly differ over time. Strong factorial invariance would be satisfied by a lack of variability over time in the corresponding intercepts of each indicator, added to a model that has satisfied weak factorial invariance. Model 2 served as the reference model against which several alternative models with invariance constraints were imposed. In Model 4, the loadings of physical aggression, defiance, activity level, and distress to limitations were equated across time (e.g., the loading of physical aggression on externalizing was equated at 8, 15, and 24 months). The fit of Model 4 was significantly worse than that of Model 2, χ2change (8) = 18.52, p = .018. Accordingly, the factor loadings significantly varied over time and weak factorial invariance was not supported.

Qualitatively, the standardized factor loadings exhibited a generalized increase with age (Figure 3), consistent with Hypothesis 3. Yet not all of these changes were statistically significant. Several follow-up model comparisons were analyzed to determine which factor loadings were changing with time, causing the rejection of weak factorial invariance. Model 2 served as the reference model in each case. Following the above approach, weak factorial invariance for each indicator's loadings at 8 versus 15 months, 8 versus 24 months, and 15 versus 24 months was evaluated in a series of single df comparisons. The defiance loadings were greater at 15 (χ2change = 4.64, p = .031) and 24 (χ2change = 5.98, p = .014) months than at 8 months. The loadings of activity level were also greater at 15 (χ2change = 4.56, p = .033) and 24 (χ2change = 13.02, p < .001) months than at 8 months. The physical aggression loading was greater at 24 than at 8 months; however, this difference was marginally significant (χ2change = 2.78, p = .095).

Figure 3. Factor loadings for externalizing behavior at 8, 15, and 24 months. Activity level and defiance exhibited significantly greater loadings at 15 and 24 months, in comparison to 8 months. Loadings that differed significantly over time within indicator are ǂp < .10, *p < .05, ***p < .001.

Does the stability of externalizing behavior increase with age?

We hypothesized that externalizing behavior would become more stable with increasing age (Hypothesis 4). This hypothesis was tested for the externalizing construct as a whole and for its individual indicators. At the construct level, the fit of Model 2 was compared against that of Model 5, in which the stability of externalizing behavior from 8 to 15 months and from 15 to 24 months was constrained to be equal. In contrast to Hypothesis 4, the fit of Model 5 was no worse than that of Model 2, χ2change (1) = 0.30, p = .583.

At the level of individual indicators of externalizing behavior, however, Hypothesis 4 received some support (Table 4). Following the procedure described in reference to Hypothesis 3, a model comparison approach to compare covariances was used to evaluate changes in the stabilities of physical aggression, defiance, activity level, and distress to limitations. Model 3 (with freely estimated covariances within and across time) was compared to models in which 8–15 month and 15–24 month stabilities were constrained to be equal. As hypothesized, the stabilities of physical aggression and defiance from 15 to 24 months were greater than from 8 to 15 months. The stabilities of distress to limitations and activity level did not increase with age.

Table 4. Does the stability of individual externalizing behaviors increase with age?

Note: Coefficients are standardized covariances evaluated with robust standard errors.

Position of externalizing behavior in its nomological network

We hypothesized that externalizing behavior would be associated with couple conflict, poor parent–infant bonding, harsh parenting, parents' young ages, and low family income (Hypotheses 5a–e, respectively). These hypotheses were largely supported (Table 5). They were evaluated by adding covariates to Model 2 and evaluating their individual covariances with the three externalizing behavior factors. Externalizing behavior at 8 months was significantly and positively associated with 8-month couple conflict, 8-month bonding problems, and 15- and 24-month harsh parenting, and negatively associated with family income. Externalizing behavior at 15 months was significantly and positively associated with couple conflict at 8, 15, and 24 months, bonding problems at 8 months, and harsh parenting at 24 months, and negatively associated with family income. Externalizing behavior at 24 months was significantly and positively associated with couple conflict at 8, 15, and 24 months and harsh parenting at 24 months.

Table 5. Associations of externalizing behavior with family functioning, income, parental age, and child gender

Note: Coefficients are standardized covariances evaluated with robust standard errors.

We did not hypothesize gender differences in the extent of externalizing behavior. Nonetheless, because they are occasionally found (e.g., Hay, Nash, et al., Reference Hay, Nash, Caplan, Swartzentruber, Ishikawa and Vespo2011), we computed the associations of gender with externalizing behavior. None of these associations was significant.

Intervention effects

The three latent externalizing behavior factors were simultaneously regressed on group (1 = control, 2 = intervention). None of these associations was statistically significant (ps ≥ .659).

Common variance analyses

We conducted a secondary evaluation of the longitudinal factor structure of externalizing behavior (parallel to Model 2), as well as the associations of the latent externalizing behavior factors with couple conflict, poor parent–infant bonding, harsh parenting, parental age, low family income, and child gender. These analyses isolated the common variance in mothers' and fathers' reports of externalizing behavior at each age (their shared view of their children's behavior). They were undertaken in order to confirm that the stability estimates and associations with other constructs were not artifacts of shared informant variance. The statistical methodology and results of these analyses are available from the first author and were largely consistent with the conclusions of the other analyses presented herein.

Discussion

In the present manuscript we asked whether externalizing behavior was a developmentally valid construct in infancy. As hypothesized, physical aggression, defiance, activity level, and distress to limitations coalesced to form a coherent externalizing behavior factor at 8 months of age. Infants who, for example, hit, kicked, and bit more were less likely to obey parental prohibitions, tended to exhibit more anger when thwarted, and were more motorically active.

As hypothesized, externalizing behavior exhibited substantial stability from 8 to 24 months (0.70). Reminiscent of Olweus's (Reference Olweus1979) famous comparison of aggression and intelligence, the stability of externalizing behavior in the present study was so high as to rival that of intelligence, which is generally in the 0.7 to 0.8 range (e.g., Watkins & Smith, Reference Watkins and Smith2013). The degree of stability in externalizing behavior in the present study is comparable to or greater than that found at later ages (e.g., Fagot, Reference Fagot1984; O'Leary, Slep, & Reid, Reference O'Leary, Slep and Reid1999). It is somewhat higher than stabilities that have been reported in the infant temperament literature. For example, stabilities of irritable distress from the first to second year of life have been in the 0.50 to 0.60 range (Pedlow et al., Reference Pedlow, Sanson, Prior and Oberklaid1993; Rothbart & Putnam, Reference Rothbart, Putnam, Pulkkinen and Caspi2002). Saudino and Eaton (Reference Saudino and Eaton1995) reported a stability of 0.42 from 7 to 35 months in activity level. It is likely that the high level of stability that we found is attributable to our latent variable approach, which allows for estimates of stability that are much less attenuated by measurement error than are stability estimates based on manifest measures. We note that, like Pedlow et al. (Reference Pedlow, Sanson, Prior and Oberklaid1993), the stabilities of the measured infant behaviors, in comparison to the latent factors, were more in line with typical stabilities reported in prior studies.

We also tested hypotheses concerning the emergent behavior of the externalizing construct. We reasoned that, as the externalizing construct gained developmental traction, its constituent behaviors would hang together more tightly and the externalizing behavior factor would exhibit greater longitudinal stability. These hypotheses were each partly supported.

We found mixed evidence for our hypothesis of increased interrelatedness of constituent externalizing behaviors over time: three of the six associations among physical aggression, defiance, activity level, and distress to limitations significantly strengthened with age. The tightening was limited to associations of physical aggression and/or defiance with activity level and/or distress to limitations. Further, all of the tightening of associations we observed was apparent in comparisons of 8 versus 15 and 24 months; no association tightened between 15 and 24 months. In addition, no interrelations between these factors decreased with age.

As further evidence of the increasing tightening of physical aggression, defiance, activity, level, and distress to limitations with age, there was some evidence, albeit inconsistent, that the factor loadings of these behaviors on the externalizing construct increased with age. Although all loadings increased with age, the significantly increased loadings were limited to defiance and activity level. These increases suggest that defiance and activity level are increasingly caused by underlying variation in externalizing behavior with advancing infant age.

The selectively significant increases in the loadings of defiance and activity level and not aggression and distress to limitations indicate that, as children move from infancy to toddlerhood, externalizing behavior becomes increasingly defined by hyperactivity and the failure to comply with parental prohibitions. Accordingly, the externalizing behavior construct exhibits a degree of heterotypic continuity. The increased relevance of activity level in toddlerhood may reflect the toddler's boosted capacity to challenge her or his parents via locomotion (e.g., running away from a parent who is attempting to enforce a prohibition). The mean age for achieving the independent walking milestone is 12 months (World Health Organization Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group, 2006). This falls squarely between the 8- and 15-month assessments of the present study, which is where the significant increases in the activity level and defiance loadings occurred. The initially low but increasing loading of defiance with age may reflect a degree of immaturity in defiance at 8 months. Moreover, defiance might be ambiguous to a parent of an 8-month-old, given the parent's uncertainties in the infant's ability to understand prohibitions. Increasing receptive vocabulary and attainment of the ability to say “no” likely later clarifies the infant's defiance; linguistic communication typically begins at around 13 to 14 months of age (Tomasello et al., Reference Tomasello, Carpenter, Call, Behne and Moll2005).

The stability of the externalizing behavior construct did not increase with age. Yet, somewhat paradoxically, we found that the stability of physical aggression and defiance did. Their respective 8- to 15-month and 15- to 24-month stabilities increased from 0.34 to 0.56 and from 0.14 to 0.50. In contrast, the stability of distress to limitations and activity level did not increase with age. This pattern may indicate that physical aggression and defiance, relative to activity level and distress to limitations, are in a more immature state at 8 months. This view is buttressed by the fact that physical aggression and defiance at this age have some variation in common that is not shared with activity level and distress to limitations. Accordingly, some infants may have a brief period of increased physical aggression and defiance at 8 months that is not part of a coherent and lasting pattern of externalizing behavior.

Externalizing behavior at 8 months was concurrently and/or prospectively associated with several measures of family environment and sociodemographics, such as couple conflict, poor parent–infant bonding, harsh parenting, and low family income. Similar associations with family climate and demographics were found for externalizing behavior measured at 15 and 24 months. Thus, infant externalizing behavior fits squarely into the nomological network established for early childhood externalizing behaviors, for which such associations would be expected in environmental and/or genetic causation models.

Implications for research and theory

The present results suggest that externalizing behavior is a normative development in infancy, and one that exhibits dimensional variation among children. Aversive behaviors such as hitting, failure to comply with parental demands, hyperactivity, and displays of negative affect when frustrated run together and should not necessarily be viewed as pathological. Similar to Tremblay et al.'s (Reference Tremblay, Japel, Pérusse, McDuff, Boivin and Zoccolillo1999) observation made with regard to physical aggression during toddlerhood, externalizing behavior as a whole may be a nearly universal behavior in the first year of life.

Its remarkably high stability, however, suggests that early elevations of externalizing behavior might be the first sign of an incipient deviant pattern of development in some children, perhaps the leading edge of the early onset, persistent trajectory evident by 17 or 24 months in prior studies (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network & Arsenio, Reference Arsenio2004; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Lacourse and Nagin2005; Tremblay et al., Reference Tremblay, Nagin, Séguin, Zoccolillo, Zelazo and Boivin2004). Yet the simultaneously high degree of discontinuity suggests that early increases in externalizing behavior may be transient for other children. About one third to one half of the variation in externalizing behavior at each time point was not explained by earlier externalizing behavior. Accordingly, although some infants retain similar positions over time in the distribution of externalizing behaviors relative to their peers, there is a substantial “reshuffling of the deck” as the infant becomes a toddler. Further research is required to illuminate the first-year trajectories of externalizing behaviors and determine their causes.

Another implication of the present findings concerns the relation of temperament to externalizing behavior. Developmentalists have frequently pointed out the blurring of the constructs of difficult temperament and externalizing behavior (e.g., Rothbart & Bates, Reference Rothbart, Bates, Damon, Lerner and Eisenberg2006). In our approach, infant distress to limitations and activity level (both measures of temperament that are included in typical operationalizations of infant difficulty) were treated as part of the externalizing behavior construct. Yet it could also be argued that physical aggression and defiance are part of the difficult temperament construct. Our findings suggest only that there is a shared underlying construct, not what that construct should be called. Psychopathologists have traditionally viewed the externalizing construct as including behaviors that are similar or identical to those identified in the temperament literature (e.g., anger/frustration/distress, activity level, or resistance to control/defiance). In contrast, physical aggression has not to our knowledge been described as an aspect of difficulty by temperament theorists; it has been described as an aspect of adjustment that is distinct from temperament (e.g., Rothbart & Bates, Reference Rothbart, Bates, Damon, Lerner and Eisenberg2006). Physical aggression is clearly an early appearing and stable individual difference. Perhaps it can be considered an aspect of temperament.

Concern about temperament/externalizing construct overlap has led researchers interested in establishing the prospective association of difficult temperament with later externalizing behavior to measure temperament in the first year of life, prior to what had been assumed to be the developmental viability of the externalizing behavior construct (e.g., Lorber & Egeland, Reference Lorber and Egeland2011). The present findings challenge these assumptions in suggesting that externalizing behavior is developmentally viable by 8 months. What may have appeared in such research to be the relation of an etiological factor (temperament) with later externalizing behavior may instead reflect the stability of the underlying construct that they both reflect.

The consistent stability of activity level and distress to limitations, in comparison to the growing stability of physical aggression and defiance in the first 2 years, also suggests the possibility of an alternative theoretical explanation for our findings. The present factor analytic results are consistent with our hypothesis that activity level and distress to limitations in large part reflect the operation of a single underlying externalizing construct. However, another possibility is a perspective that views activity level and distress to limitations as aspects of temperament that are distinct from, albeit associated with, externalizing behaviors such as aggression and defiance (e.g., Rothbart & Bates, Reference Rothbart, Bates, Damon, Lerner and Eisenberg2006). From this alternative view, the consistent stability of activity level and distress to limitations we found may reflect temperamental dispositions that are already in place before aggression and defiance have stabilized and may thus play a causal role in their development. In support of this notion, higher levels of infant activity level and distress to limitations predict increases in physical aggression and defiance; although bidirectional causation is suggested by the fact that more physical aggression also predicts increases in activity level and distress to limitations (Lorber, Del Vecchio, et al., Reference Lorber, Del Vecchio and Slep2014).

The present findings extend prior work by documenting the validity of the externalizing behavior construct by 8 months of age, earlier than has been previously shown. Exactly when the externalizing behavior construct becomes developmentally viable, however, remains unknown. Our tentative reinterpretation of the findings of Hay et al. (Reference Hay, Perra, Hudson, Waters, Mundy and Phillips2010), that contentiousness in 6-month-old infants reflects externalizing behavior, suggests that one may even need to look prior to 6 months.

Implications for preventive intervention

If externalizing behavior is a valid construct by 8 months, it follows that effective interventions to prevent the earliest manifestations of abnormally high levels of externalizing behaviors might also begin in the first year. Where early childhood externalizing behaviors are concerned, however, infancy-era preventive interventions have often shown null effects (e.g., Stone, Bendell, & Field, Reference Stone, Bendell and Field1988; St. Pierre & Layzer, Reference St. Pierre and Layzer1999), small effects (e.g., Love et al., Reference Love, Kisker, Ross, Raikes, Constantine and Boller2005; Velderman et al., Reference Velderman, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Juffer, van IJzendoorn, Mangelsdorf and Zevalkink2006), and/or effects limited to subpopulations and/or narrow aspects of behavior (e.g., Sidora-Arcoleo et al., Reference Sidora-Arcoleo, Anson, Lorber, Cole, Olds and Kitzman2010; Van Zeijl, Mesman, Stolk, et al., Reference Van Zeijl, Mesman, Stolk, Alink, van IJzendoorn and Bakermans-Kranenburg2006). Each of these interventions was designed prior to the publication of the present study and the two key prior studies that together suggest the emergence of externalizing behaviors in the first year of infancy (Hay et al., Reference Hay, Perra, Hudson, Waters, Mundy and Phillips2010; Van Zeijl, Mesman, van IJzendoorn, et al., Reference Van Zeijl, Mesman, van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Juffer and Stolk2006). None addresses externalizing behavior in the first year. Perhaps interventions that improve parents' management of physical aggression, defiance, activity level, and distress to limitations when they are developing in the first year, and prior to when they are engrained “externalizing problems,” will yield enhanced preventive efficacy. The application of our findings to preventive intervention, however, should be tempered by the need to replicate and extend them to additional population groups and using additional sources of information about child behavior (e.g., nonparental reporters and observations).

The meaning of infant aggression

Finally, we acknowledge the cognitive perspective advocated by some that “true” aggression can only be said to have occurred if the actor understands the act's potential effects on others and that it requires an intention to harm and/or a kind of means–end calculation about what the impact or instrumental value of the aggressive act is (Bandura, Reference Bandura1973; Dodge, Coie, & Lynam, Reference Dodge, Coie, Lynam, Damon, Lerner and Eisenberg2006; Maccoby, Reference Maccoby1980). Such clear intentionality or means–end calculations in an 8-month-old is doubtful. Accordingly, scholars who espouse the cognitive view may argue that such behaviors as kicking, pushing, hitting, smacking, biting, hair pulling, pinching, and scratching in infancy are not actually aggression—that true aggression is not developmentally viable in infancy.

Our approach to defining aggression is topographical (Hay, Hurst, et al., Reference Hay, Hurst, Waters and Chadwick2011; Loeber & Stouthamer-Loeber, Reference Loeber and Stouthamer-Loeber1998; Reid, Patterson, & Snyder, Reference Reid, Patterson and Snyder2002; Tremblay, Reference Tremblay2000) and therefore does not require inferences about underlying cognitive processes. Yet we do not discount the impact of cognitive development on the meaning of physically aggressive behavior. To build on an example from the introductory section of this article, a 1-year-old may kick a parent in a flailing fashion during diapering, but the infant is clearly not capable of making a means–end calculation about the impact of the kicking. In contrast, the same child at age 5 may walk up to the parent while she or he is reading a newspaper and kick him or her with the express goal and expectation of gaining the parent's attention and with the knowledge that the kick will hurt the parent. Thus, kicking may mean something different at 1 and 5 years. Evidence suggests that instrumental forms of aggression increase between infancy and toddlerhood (Hay, Hurst, et al., Reference Hay, Hurst, Waters and Chadwick2011). From our position, however, that does not imply that kicking at age 1 is necessarily less meaningful than kicking at age 5. That is an empirical question that has yet to be answered. The present findings suggest that it is one worth asking.

Limitations

The present sample was selected based on elevated risk for interparental physical aggression. Because aggression tends to run in families via environmental and genetic mechanisms (Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2005), the children of the present sample were themselves at elevated risk for higher levels of externalizing behavior. By increasing the presence of maladaptation in study samples, the at-risk approach provides ample opportunity to observe and juxtapose both deviant and normative development (Masten, Reference Masten2011). Accordingly, our findings were informative where the relative degree of externalizing behavior was concerned, but less so with regard to absolute levels. There is no guarantee that the means we report, and any age-based changes in the means, generalize to normative populations. For these reasons, we have chosen to emphasize relations among constructs, rather than central tendency. The same interpretive caution applies to the interrelations among externalizing behaviors, their stabilities, and their associations with other factors (e.g., family environment).

The present study would also have been strengthened by observational measures of externalizing behaviors. Our reliance on parental report leaves open the possibility that infant externalizing behavior is a subjective, rather than objective, phenomenon. This limitation is tempered somewhat by results presented in Lorber, Del Vecchio, et al. (Reference Lorber, Del Vecchio and Slep2014). Mother–father agreement on infant physical aggression and defiance was reasonably high. In addition, infant physical aggression and defiance were associated with more negative infant affect and physical struggle observed during arm restraint, albeit modestly and inconsistently so. Jointly these findings suggest some degree of objectivity in parents' reports of externalizing behavior.

Finally, it is possible that participation in the Couple CARE for Parents intervention had undetected effects on child behavior. No main effects of the intervention on externalizing behavior were found. Yet this fact does not preclude the possibility of the intervention having impacted subgroups of children differently.

Conclusion

The present results indicate that the externalizing behavior construct is developmentally viable by 8 months of infant age. This conclusion is based on the factor structure, substantial longitudinal stability, and concurrent and predictive validity of externalizing behavior measured at 8, 15, and 24 months of age. Early starting externalizing behavior problems were once defined as those beginning prior to school entry (Campbell, Reference Campbell1995). This view has gradually given way to evidence indicating stable externalizing behavior's emergence between 17 and 24 months of age (e.g., Shaw, Bell, & Gilliom, Reference Shaw, Bell and Gilliom2000; Tremblay et al., Reference Tremblay, Nagin, Séguin, Zoccolillo, Zelazo and Boivin2004). Our findings, in combination with those of Van Zeijl, Mesman, Stolk, et al. (Reference Van Zeijl, Mesman, Stolk, Alink, van IJzendoorn and Bakermans-Kranenburg2006) and Hay et al. (Reference Hay, Perra, Hudson, Waters, Mundy and Phillips2010), suggest yet another downward adjustment to developmental models of early externalizing behavior and perhaps intervention strategies to prevent early externalizing behavior problems.