“These people used to call upon the name of Amida, but now when they encounter danger or are alarmed by a sudden change of things, they recite the names of Jesus and Mary. They call each other by baptismal names, and cross themselves before eating meals or drinking tea. This way they are learning Christian customs so naturally that sometimes it even appears to me that these people have been Christians from the old days.”

–Luis Frois, Historia de Japam, 1587Footnote 1Since St. Francis Xavier landed in Kagoshima in 1549, the Jesuit mission in Japan had achieved an amazing number of conversions, even though their activity lasted for merely about fifty years. Their great success came to an abrupt end in 1614 when the Bakufu government began the full proscription and persecution of the religion. An earlier ruler, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, had already banned Christianity and ordered the expulsion of foreign missionaries in 1587, but without strict enforcement. Since the 1630s, the former Christians were required to enroll in local Buddhist temples and annually go through the practice of treading on Christian icons in order to prove their apostasy. However, many Christians secretly retained the faith by disguising their true religious identity with Buddhist paraphernalia. These so-called “underground” (or sempuku) Christians survived more than two hundred years of persecution, and today some groups still continue to practice their own religion, refusing to join the Catholic Church. The present-day religion of the latter, called “hidden” (or kakure) Christians to distinguish them from the former, has drawn the attention of ample anthropological as well as religious studies.Footnote 2

My essay concerns the underground Christians' visual culture in the earlier period of their secretive religion, roughly from the proscription of 1614 to the middle of the eighteenth century.Footnote 3 Even though Christianity was widespread throughout the entire nation, I will focus on the Nagasaki and Bungo regions of Kyushu, where the Jesuits' missionary efforts had been highly concentrated, and the majority of underground Christians were discovered later in a series of crackdowns.Footnote 4 Most of the visual objects I discuss in this essay were recovered from the Nagasaki area and the islands off its coast. During this period of persecution, the underground Christians' religion and practice gradually fused with Pure Land Buddhism, the process of which can be observed in both their verbal and visual culture.

The Jesuits' adaptation method of teaching Christianity in comparison to the indigenous religious tradition had the possibility of confusion from the beginning, especially for the Japanese who were used to the syncretistic co-existence of multiple religious beliefs.Footnote 5 When severe persecution gradually pulled the Japanese away from the Jesuits' guidance,Footnote 6 their isolated Catholicism and imagery came to be conflated with Pure Land Buddhism, from which they adopted verbal, visual, and ritualistic elements to disguise their religion. The lay leader and catechist alone, who had supplemented the shortage of ordained priests in the pre-persecution era, seemed simply insufficient to prevent such a gradual transformation over the generations without regular contacts with the Church.Footnote 7 This conflation would eventually lead to a third religion, not identical to either Catholicism or Buddhism, which has continued up to the present by hidden Christians in the western islands off the coast of Kyushu.

I am arguing that the underground Christians' conflation of Catholicism with Pure Land Buddhism was not only caused by external factors of persecution and the need for camouflage but was also strongly effected by the internal, theological elements common to both religions. Their initial use of Buddhist icons as devotional substitutes was likely motivated by the purpose of disguise based on the similarities among those icons and related rituals. However, the substitution gradually became rationalized and justified, and eventually led to a fusion of two religions. This phenomenon should also be understood in light of the very theology of Pure Land Buddhism, in which bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara (Japanese: Kannon) and Buddha Amitabha (Japanese: Amida) miraculously intervene and conduct soteriological works for sinful human beings. Under severe persecution from the government and isolation from the Church's theological guidance, Japanese Christians not only had to camouflage their true religious identity but also, and more urgently, needed to shape and preserve their religious imagery with the verbal and visual traditions with which they had been deeply infused. Among the multiple religious traditions that had syncretistically co-existed in Japanese culture, Pure Land Buddhism appears to have provided underground Christians with the most justifiable rationale for the substitution of its visual and verbal imagery as alternatives.Footnote 8 As a result, the unusual circumstances of persecution and isolation brought forth an interesting case of the two religions' conflation, first in the realm of their visual imagery, which would then eventually modify what they had originally stood for in theology.Footnote 9

The similar role and appearance of the Virgin Mary and bodhisattva Kannon have been discussed by many scholars of religion and art history, but I believe that not only their common intercessory role or external resemblance but also the latter's power of transformation and manifestation, drawn from the “Universal Gate” chapter of the Lotus Sutra 妙法蓮華經, led to the justification of the iconographic substitute known as Maria-Kannon. In this regard, another occasion of iconographic conflation or proximity was observed between the image of Fifteen Mysteries of the Rosary and Taima Mandara, a schematic representation of Amida's paradisiacal Pure Land.Footnote 10 Their association also needs to be explained, not merely by similar compositions, but also by their analogous function in devotional practices. Both rosary prayer and the sixteen-view contemplation of Pure Land Buddhism utilized these images as visual manuals to guide mental visualization often combined with repetitive, numerically formulated prayers.

On the other hand, the substitute Buddha images used by underground Christians, unlike the case of Maria-Kannon, have rarely been identified as a specific Buddha except for one Amida statuette.Footnote 11 Usually these statues are so small and simply shaped that they do not exhibit distinguishable iconographic features to identify. I argue that their identity should be decided by the perception and religious imagery of underground Christians rather than ambiguous formal traits. I believe that in this regard they were deemed to be Amida, initially disguising but eventually impersonating and fusing with Christ. I will support this argument not only with the theology and imagery of Amida in Japanese Buddhism and its art but also with significant references to him in underground Christians' orally transmitted biblical account, Tenchi Hajimari no Koto (On the Beginning of Heaven and Earth, hereafter THK), recovered in manuscripts circulating in the western islands off the coast of Nagasaki.Footnote 12

I do not, however, argue that underground Christians regarded the Virgin literally as one of Kannon's thirty-three manifestations, or that they identified Amida as another of Christ's hypostases, even though the rather provocative title of this essay may misleadingly suggest as much. Rather I attempt to point out that the Jesuits' remarkable proselytization in Japan must have been, regardless of their awareness of it, greatly facilitated by the Japanese heritage of Pure Land Buddhism, which had shaped their religious disposition to be susceptible to Christianity, alien but analogical regarding its primary deities or personages, soteriology, and even visual culture. The Pure Land School was much stronger and more deeply rooted in Japanese Buddhism than in that of China or Korea, whence the school was transmitted. No matter how much the Jesuit fathers dismissed and despised Buddhism as the devil's poor imitation of the true faith, similarities between Jesuit Christianity and Pure Land Buddhism contributed to Japanese conversion and tenacious adherence to Christianity in the following centuries of persecution.

I. The Jesuits' Presence in Buddhist Japan

The Jesuits' mission in Japan was an unprecedented success at least in numbers, especially when we compare it with the case in China that shared with Japan cultural heritage such as Chinese writing and Buddhism. The Jesuits converted around six thousand Japanese in the first ten years after St. Francis Xavier's arrival, and by the time of proscription in 1614, the number of converts reached around three hundred thousand. Conversion continued even afterward and their number reached 760,000 by the early 1630s.Footnote 13 The Christian mission began first in Kyushu but in the 1560s spread to the main island of Honshu under Oda Nobunaga's permission and support.Footnote 14 Finally, missionaries had free access to all parts of Japan, which also contrasts with the situation in China.Footnote 15

Surprisingly, the maximum number of priests in Japan by 1614 was merely 142, including seven Japanese. This shortage was complemented by the Jesuits' active employment of lay leaders and catechists.Footnote 16 These lay catechists catered to the religious needs of the villagers and were later even endowed the authority to give baptism and funeral services. Furthermore, the Jesuits encouraged the lay organizations called Confraria based on the model of European confraternity, which initially aimed at charitable activities but gradually became devotional organizations under persecution.Footnote 17 These lay brotherhoods and catechists continued to play their roles during the underground era and served as the foundation for the disguise and preservation of their religion. Kawamura interestingly observes that this Christian confraternity resembled the traditional lay organization of True Pure Land Buddhism, and thus could easily be understood and appropriated by the Japanese populace.Footnote 18

The impressive number of conversions is, to a certain extent, ascribed to the unique Japanese political culture that caused the mass conversion. When a local daimyo converted to Christianity, all his subjects in the realm, even including Buddhist monks, had to follow their ruler.Footnote 19 However, the sincerity of these early Christians should not be underestimated merely due to their initial motive for baptism, since the conversion continued even after the national ban of 1587, and more significantly, when the severe persecution began in 1614, many Japanese Christians chose to die as martyrs rather than retreat from their faith. Over the thirty years' persecution after 1614, more than two thousand Japanese Christians were martyred.Footnote 20 Considering the roughly fifty years of the Jesuits' mission activity, the number of martyrs is simply amazing. Even more remarkable about Japanese Christianity is the survival of underground Christians, who secretly retained and continued their religious identity and practice for the next several hundreds of years, even to date. The martyrdom and the survival of underground Christians in Kyushu indicates that Christianity, albeit not fully understood, took firm root among the Japanese.Footnote 21

Such an eager sympathy with, if not the orthodox understanding of, Christianity was possible, in part because the Japanese were already ingrained with a similar set of ideas, deities, and visual culture from Pure Land Buddhism. Early Jesuit fathers in Japan also noted the formal similarities between Catholicism and Buddhism, as Fr. Matteo Ricci did in China.Footnote 22 Fr. Vilela reported, “The monks say matins, tierce, vespers and complines, for the devil wished them to imitate the things of Our Lord in everything.”Footnote 23 Fr. Frois called the Gion festival in Kyoto the devil's attempt to imitate the Feast of Corpus Christi.Footnote 24 No matter how devilish the Jesuits regarded these elements, they attempted to take advantage of such similarities to familiarize the Japanese with their Western religion. For example, St. Francis Xavier borrowed Buddhist terms such as Dainichi (Buddha Vairocana for God), jodo (Pure Land for heavenly paradise), jigoku (hell), and tennin (angel).Footnote 25 However, after the term Dainichi caused serious confusion, the Jesuits preferred to use the transliterations of the original Latin.Footnote 26

The religious and ideological foundation in Japan, though sharing much with China, was rather different. Even though Confucianism was the ruling ideology of China and Korea, it never reached the same status in Japan. It was largely limited to the upper warrior class as their codes of conduct in the later Bakuhu government.Footnote 27 Thus, adaptation to Confucianism, which was Fr. Matteo Ricci's lifelong endeavor in China, was rather unnecessary in Japan.Footnote 28 Whereas Buddhism in China and Korea retreated largely as a religion devoid of political power, Japanese Buddhism maintained a considerable political status with wealth and even military force. Its position in society was quite similar to that of Christianity in Europe.Footnote 29 Already since the Kamakura period (1180–1333), Buddhism had penetrated into every level of Japanese society and was the de facto state religion.Footnote 30 Boxer even observed that, compared with the Confucianist and rather atheistic Chinese and Koreans, the Buddhist Japanese might have had more potential to embrace Christianity as a religion.Footnote 31 Three schools of Buddhism, namely Zen, Pure Land, and Nichiren, became the most dominant in Japan. Pure Land and Nichiren, in particular, held the strongest appeal to the populace.Footnote 32

Pure Land Buddhism as an identifiable school in Japan was launched by Honen 法然 (1133–1212), whose teachings on the simple practice of Nembutsu 念佛, the invocation of Amida, and the reward of rebirth in the Pure Land were easily accessible to a wide range of believers.Footnote 33 As Pure Land Buddhism grew and evolved, one of its sects, True Pure Land 淨土眞宗 founded by Shinran 親鸞 (1173–1262), became especially powerful. The Nichiren School originated in the teachings of former Tendai 天台 monk Nichiren 日蓮 (1222–1282), who deemed the Lotus Stura 妙法蓮華經 to be the gist of the religion. In Pure Land Buddhism, the focus of popular worship centered on two deities, Buddha Amida and bodhisattva Kannon. Pure Land Buddhism teaches that in the degenerate age of the law, sinful human beings are devoid of the ability to achieve nirvana by their own efforts and thus they should rely on Buddha Amida's salvific compassion and power to be reborn in his Pure Land. In this process, his attendant bodhisattva Kannon provides immense help.

The Nichiren School proposes the thorough study and even worship of the Lotus Sutra.Footnote 34 This sutra is probably the one single most widely loved and read sutra in Japan.Footnote 35 Even though the Nichiren School was quite critical of and even hostile to Pure Land Buddhism, their Lotus Sutra also contributed to the great faith in and popularity of Kannon, since its chapter 25, titled “Universal Gate,” details the intercessory power of this bodhisattva. For this reason this chapter is even called Kannon sutra. Kannon's intercession ultimately aims to deliver human beings and transport them to the Pure Land of Amida. Not limited to Pure Land scriptures, the Lotus Sutra also describes Amida's Pure Land as the afterlife paradise in chapter 23.

If within the latter five hundred years after the Buddha entered Nirvana, there is a woman who listens to this sutra and practices as it says, then at the end of this life, she will go to the world of peace and delight, where Amitabha Buddha and the great company of bodhisattvas reside around, and she will be born on a jeweled seat inside the lotus flower.Footnote 36

若如來滅後後五百歲中, 若有女人聞是經典, 如說修行。於此命終, 即往安樂世界, 阿彌陀佛、大菩薩眾, 圍繞住處, 生蓮華中, 寶座之上Footnote 37

Thus, both the Pure Land and Nichiren Schools spawned the cult of these two deities, whose positions in Japanese Buddhism were far more prominent than in Chinese or Korean Buddhism.Footnote 38

The Jesuits' active adaptation to Japanese culture began with Fr. A. Valignano, whose method of so-called modo soave differed from the earlier one-way approach.Footnote 39 He appreciated the firm status of Buddhism in Japanese culture. Its priests were a respected model of decorum and the Jesuits had to emulate them to compete.Footnote 40 Due to Japanese respect for Buddhist monks, the Jesuits also enjoyed a similar esteem, being regarded as their peers.Footnote 41 Both elementary and advanced levels of education were offered in Buddhist temples and monasteries, which further consolidated the respect for Buddhism in the society.Footnote 42 All these circumstances led Valignano to conceive of the adoption of Buddhist models in the shaping of Christian church and community organizations. Furthermore, the Jesuit seminary and college at, respectively, Funai and Nagasaki seriously taught Buddhist theology in their curricula, although only to refute it.Footnote 43

However, such an active interest and approach to Buddhism did not last long. Seeing that Oda Nobunaga and his successor Toyotomi Hideyoshi repressed the militant Buddhists, such as those of True Pure Land and Nichiren, Valignano abandoned the idea of following Buddhist models, regarding the latter no longer as powerful peers.Footnote 44 But Nobunaga and Hideyoshi opposed the secular, political power of certain Buddhist sects, not the religion's status in Japanese culture, which Valignano did not understand.Footnote 45 Thus on the eve of the Jesuits' expulsion from Japan, there remained between Buddhism and Christianity enmity and distrust. The real contact and mutual acculturation between the two were to take place under persecution, in which underground Christians had to continue to shape their religious life and practice, on the one hand, with their isolated memory of Christianity, and on the other hand, with their own cultural heritage of worshiping Buddhist deities through visual experience.

The Jesuits' annual report on the year 1621, written by Fr. Geronimo Majorca from Macao to the Jesuit General Matteo Vitelleschi, recounted two interesting incidents that attest to a strange coexistence, albeit not yet a fusion, of the two religions. The setting of these two events was Bungo province, an important center of mission activity with the Jesuit college built in Funai.

A young man, an ardent worshiper of the idol [Amida], fell ill and asked his Christian parents to bring in a Buddhist monk. The superstitious prayer of the Buddhist monk did not cause any improvement and his condition became worse. His mother repented of her inviting a Buddhist monk and went out to the house garden in the night and harshly flagellated herself for punishment. While beating herself, she saw that a cross surrounded by mysterious light was arising above a nearby mountain. She further whipped herself and cried, asking for Deus's mercy. She called her husband to bring the sick son so that he could also see the mysterious cross. The vision of the cross changed everything for this young man. He thence received baptism and recovered his health.

A Christian lady, without judging from God-fearing reverence, was rather heedlessly drawn to the temptation to visit a pagan [Buddhist] temple. Visiting a temple, she was urged by her company and together with them bowed to the idol. After committing this act of blasphemy, she suddenly felt a sharp pain in her body. When the pain abated for a moment, she came back home with all her strength. To her alarmed husband, she recounted her act of reckless curiosity. He told her that she was being punished and that she should beg for forgiveness from Deus. She earnestly implored Deus for His mercy and the pain disappeared.Footnote 46

Even though the Jesuit writer underscored the eventual triumph and superiority of Christianity, the story more likely demonstrates the coexistence of different religions typical in Japanese culture. Christian parents were calling a Buddhist monk to cure their Buddhist son's illness. A Christian lady was tempted to visit and venerate a Buddhist statue, probably expecting that the act would bring her extra merits in addition to Christian blessing. These Japanese converts did not see much contradiction until they ran into a punishment from the monotheistic Christian God. Furthermore, a beaming cross soaring above the village mountain is strongly reminiscent of the Pure Land Buddhist iconography of Yamagoshi Amida, in which Amida surrounded by light appears above a nearby village mountain.Footnote 47 This common Amida image was christened by changing his image into a cross.

In 1621, even though these Japanese converts were clearly aware of the distinction between Christianity and Buddhism, they were not shunning the latter from their daily lives. In the next decade, priests who were in hiding would be rooted out, and these Japanese Christians actively employed Buddhist terms and images, disguising their secret religion. Without the strict guidance of the ordained priests, as they continued to practice on their own their underground Christianity camouflaged with Buddhism, which they had not strictly detested even in the earlier days, the latter gradually became more and more a part of the former, and the confusion and conflation between the two in words and images became more firmly substantiated as a third entity over the generations.

II. Maria-Kannon: Masquerade and Manifestation

When the persecution of Christianity intensified, Christians were required to declare apostasy and enroll in local Buddhist temples.Footnote 48 However, many of them chose to secretly retain and continue their religious practices, using Buddhist statues and altars as a domestic substitute. The so-called Maria-Kannon is, accurately speaking, the statue of the Son-bringing Kannon, which underground Christians substituted as the icon of the Madonna and the Child in their secret practice of Christian devotion (Fig. 1).Footnote 49 Many of these statues are porcelain figures imported from southern China, where the cult and production of Son-bringing Kannon was very popular.

Fig. 1. Maria-Kannon, seventeenth century, Porcelain, import from Fujian, China. Courtesy of Oura Cathedral, Nagasaki, and Kaibunsha (Kirishitan Ibutsu, 1964)

Studies on this Christian substitution of the Kannon's icon primarily discuss the tactic of disguise relying on the apparent formal similarity between the bodhisattva with a boy and Madonna holding the Christ Child.Footnote 50 In China, where the bodhisattva's feminization as the Son-bringing Kannon (Chinese: Songzi Guanyin 送子觀音) was first established, her figure already caused a serious confusion with the Catholic icon of Mary.Footnote 51 Such confusion reflects Catholicism's fast spread under the mission project of Jesuit Giulio Aleni (1582–1649) in Fujian province, where these figures were made and exported to Kyushu.Footnote 52 A similar phenomenon of iconographic conflation is repeated in Kyushu, but here for the purpose of camouflaging underground Christians' true religious identity and guaranteeing their survival.

Significantly, Takemura indicates that such a conflation of Mary and Kannon could have begun much earlier than the ban of Christianity and persecution. The Japanese populace, ignorant of the outside world, often perceived European missionaries as Indians and thus regarded the female figure Mary they brought as a Buddhist deity. In particular, the Jesuits' traditional manner of venerating Mary was hardly different from Japanese devotional practice to Kannon. Even the swastika carved on Kannon's chest was easily confused with the cross.Footnote 53

The statuettes of Maria-Kannon were made also indigenously in Japan, and as the persecution became severer, the figure of the boy was removed and only the female Kannon remained.Footnote 54 This was apparently an attempt to avoid the persecutors' suspicion that underground Christians' were using the Son-bringing Kannon figure as the icon of the Virgin and the Child. However, paradoxically the Kannon statuette became more indistinguishable from that of Mary, since Mary's single figure had already been made in the fashion of Kannon from the pre-persecution era in Japan. It was an indigenization process, and the Japanese perceived it to be Mary's real appearance.Footnote 55 Compared with other, more technically accomplished Christian art, such as painting and engraving, these Maria-Kannon statuettes have received much less attention from art historians, probably because many of them were Chinese imports appropriated, but not produced, by Japanese Christians, and the point of discussion centers around their unusual use compared to their original iconographic meaning.

I am distinguishing my thesis from these studies by posing different questions. Focusing on the earlier period of persecution after 1614, I am asking what rationale justified these underground Christians in using Kannon's icon as Mary's. If the purpose of Buddhist disguise was the primary one, why would they have chosen this specific bodhisattva out of so many? Because Kannon was the most popular deity in Japanese Buddhism? If so, would they not have wanted to use a rather less renowned deity, since due to her prominence it might have been difficult even for the Christians to perceive Kannon as somebody else? Or, because she is the personification of compassion as Mary is?Footnote 56 Or that her female sex and an attending boy were so reminiscent of Mary and the Child? Could such similarities in attribute and appearance, on the contrary, not have led them to regard the Son-bringing Kannon as detestable and dangerous, as their Jesuit fathers had often accused Buddhist resemblances of being the devil's mockery of the true religion?

Probably in the first instance, it was such an analogy or the prominence of Kannon that led underground Christians to appropriate her image as Mary's substitute. However, once it began, the conflation of the two images gradually became reasonably plausible and even justifiable due to the inherent attribute of this bodhisattva, namely her power to transform in thirty-three manifestations. I need to underscore again that these underground Christians, so determined and devoted enough to risk their lives for faith, were certainly well aware of the difference between the two religions, and they could not have believed that Kannon literally became Mary, at least in the earlier decades of underground faith. The term Maria-Kannon was not used by underground Christians.Footnote 57 However, as I will discuss in the last section of this essay, these devoted Christians' religious imagery was amply infused with their own cultural heritage of Buddhism and, even at this early stage, a unique kind of syncretism or fusion was in the process of germination. The double circumstances of persecution and isolation were bringing their religious imagery of Mary close to that of Kannon, since the latter not only protected their identity, but was filling in their incomplete and fading knowledge of Marian imagery and theology.Footnote 58

Higashibaba observes that in the syncretistic religious culture of Japan, such an assimilation of different religious deities had not been unusual.Footnote 59 It was the concept of hierarchical manifestation that has frequently explained and justified the coexistence of different religious systems or deities.Footnote 60 For instance, the indigenous deity Kami was incorporated into the Buddhist system as a manifestation of bodhisattva or Buddha. Furthermore, Buddhas and bodhisattvas also could be the manifestations of the one original Buddha. And, significantly, this one original Buddha was Amida in the Japanese religious culture, in which Pure Land Buddhism was very powerful. In other words, all deities in the universe could be ultimately encompassed in the one body of Amida, who stands at the apex of the complicated chain of manifestations. If so, the Virgin Mary as the manifestation of Kannon could also be eventually related to Amida along this chain of manifestations and completely incorporated into the Buddhist cosmology. The problem was, however, that Christianity was the first religious idea to enter Japan that did not allow such assimilation to other religious systems. However, Christianity's exclusivity could not be enforced after 1614 due to the expulsion of foreign missionaries and the isolation of Japanese Christians from the European Church authority.

Even in the pre-persecution days when the missionaries were present, Christianity was often understood by the Japanese as compatible with Buddhism. Frois observed an incident in western Kyushu in 1564:

Among those receiving baptism, there was a 90-year-old lady from a very prominent family. She had been a very devoted Buddhist and had made pilgrimages to most of the famous temples in Japan. She was wearing a garment, on which the life [that is, teaching] of Amida was written. Some monks gave her this paper garment and told her that wearing it would bring her to paradise when she died. Wearing this garment of scriptures, she also carried with her the writings of Papal Bulls and edicts. … When she learned about Christian teachings, she became quite pleased and asked to receive baptism. When she learned many Christian prayers despite her old age, she brought the scripture garment and other Buddhist things to the priest to burn them all.Footnote 61

It is always after the priests' intervening admonition that their Japanese converts realized the incompatibility of Christianity with other religions. Another illustrative example is the story of converts bidding farewell to Amida and asking for Amida's understanding before baptism, which I will discuss in the last section of this essay.

The conflation with Buddhism was not entirely discouraged by Buddhists either. Buddhist monks often granted underground Christians the certificates of apostasy without asking for real conversion.Footnote 62 As underground Christians concealed their religious identity literally under the protection of Buddhism, their perception and use of Buddhist symbols and images could gradually become indistinct with the original Christian signs, sometimes with the former overriding the latter. A kind of transculturation, albeit employed for survival, in the realm of visual representation could eventually affect their represented as well.Footnote 63 Quite illustrative of such a bond between the two religions is an incident of arrest in 1623, when a Christian girl, Regina, was arrested near present-day Kawaguchi City in Honshu. Since the head monk of the Chodoku temple helped pardon and free her, out of gratitude her father donated to the temple a seated Amida statue, inside of which a little figure of Maria-Kannon and a cross were later found.Footnote 64 Because it was taboo to freely open an enclosed box inside a Buddha's body, the insertion of Christian objects in the Amida statue could signify quite different messages simultaneously. However, Mary in the figure of Kannon was inserted in the body of Amida, who often impersonated Christ for underground Christians, in order to thank the Buddhist for his help and protection for Christianity. This association of symbols likely exemplifies a certain degree of amalgamation of the two religions, even though those effecting it probably were not precisely aware of the process.

It is true that Kannon could easily be adopted as Mary because of her female sex. However, the aforementioned feminization of Kannon in China was also ascribed to her capability of transformation asserted in the Lotus Sutra. Its “Universal Gate” chapter lists seven female transformations of Kannon. Such transformation stories abound in Japanese folktales as well, where Kannon has been worshiped even more fervently than in China.Footnote 65 In addition, the most widely read and respected sutra in Japan was the Lotus Sutra, the origin of the belief in Kannon's transformation and manifestations. The Lotus Sutra was the primary text of the Nichiren School, but like the worship of Amida and Kannon, it was a Pan-Buddhist scripture in Japan. There are many Japanese miracle stories that attest to the wonder-working power of this sutra and especially its most prominent deity Kannon. The Konjaku Monogatarishu 今昔物語書 (ca. 1107), the largest tale collection in Japan, contains forty stories about Kannon's miraculous intervention, of which many recount her transformation and manifestation. Furthermore, The Miraculous Tales of the Hasedera Kannon (ca. 1210), originating from one of the Saikoku Kannon pilgrimage sites, contains the thirty-three stories of Kannon's manifestations.Footnote 66 The belief in Kannon's manifestation and intervention in human life was further encouraged in the True Pure Land sect. Its founder, Shinran 親鸞 (1173–1262), is said to have received a message from Kannon in a dream that the deity would appear to him as a woman and be his wife in order to lead him to the Pure Land.Footnote 67 The female manifestation of Kannon continued to be depicted in paintings up to the eighteenth century in Japan.Footnote 68

The concept of Kannon's thirty-three manifestations was so firmly rooted in Japanese belief that the aforementioned Saikoku Kannon pilgrimage sites also consist of thirty-three temples, where thirty-three holy icons of Kannon were supposed to personify those manifestations.Footnote 69 However, the specific thirty-three manifestations enumerated in the Lotus Sutra were not literally understood as such, since the thirty-three icons of the Saikoku pilgrimage do not represent those of the sutra. Her manifestations that appear in the miracle stories are not limited to them. In other words, her power to transform was believed to be virtually at will, opening the possibility to manifest even as a Christian personage, Mary.

Alluding to this possibility is a phrase from THK, wherein the Trinity was expounded in a rather strange transformation. “Deusu [Deus] is the Father or Paateru, the Holy One is the Son or Hiiriyo [filius or filho in Portuguese], and the Holy Mother is the Suheruto Santo [Sactus Spiritus]. Deusu became three bodies although they were originally One.”Footnote 70 Apparently referring to the theology of Holy Trinity, however, the hypostasis of the Holy Ghost is identified with the Virgin. This imagery of the central Deus accompanied by two flanking deities or personages, especially one with an apparently female appearance, strongly reminds of the iconography of Amida Triad (Fig. 6), in which the central Amida appears in the company of the female bodhisattva Kannon and male Seiji (Sanskrit: Mahasthamaprapta). This iconography of the Amida Triad was highly popular in Japan and appeared in various Buddhist paintings throughout the ages. In fact, Matteo Ricci in China perceived it to resemble the Christian Trinity.Footnote 71

III. Rosary, Mandara, and Kannon Prayer

The devotion to Mary played a considerable role in the religion of underground Christians. First, the prayer of the rosary, consisting of fifteen narrative themes drawn from Mary's and Christ's life stories, provided them with a mnemonic framework of salvation history, which was absolutely indispensable as their Christian texts were all confiscated. Secondly, due to the yearly trial of treading on Christian icons, penitential prayer and rite became very significant for underground Christians. As a result, their religious orientations moved from the fearful judging Father to the forgiving Mother, Mary. In this context, Maria-Kannon often occupied the central position of their domestic Buddhist-Christian altar.Footnote 72 Underground Christians' penitential prayer book, Konchirisan no Ryaku (Essentials of Contrition), originally published by the Jesuits in 1603 but continuing to circulate among underground Christians up to the nineteenth century, also has a significant reference to the intercessory power of the Virgin. “What you wish, entrust it to the [Holy] Mother. The Mother of Misercordia is the intercessor for sinners. God eagerly listens to her. Apart from God Himself, there is no one who can plead for our souls as much as the Holy Mother does.”Footnote 73 This prayer book and the absolutional power of the Virgin were significant to underground Christians since they could still be assured of the forgiveness for their sins without the presence of priests and the sacrament of confession.Footnote 74 These two elements of the rosary and penitential prayer brought the person of Mary even closer to Kannon.

The importance of the rosary for underground Christians is well demonstrated by the fact that the content of THK is based on the mysteries of the rosary.Footnote 75 Isolated from priests and deprived of any scriptural literature in hand, they must have relied heavily on the memorized sequence of narrative themes in the rosary to compose the oral account of THK and transmit it through memorization. Not only its storyline, but also the words of THK directly urge the practice of the rosary. For example, on the day of St. John the Baptist's birth, THK commands the practice of fifty-three orassho (oratio), which refer to the fifty Ave Marias for the Joyous Mysteries of the Rosary.Footnote 76 In the story of Mary finding her Son in the temple, THK accordingly relates the event to the five Joyous Mysteries and instructs the reader to practice them in the morning.Footnote 77 As I discussed earlier, the Jesuits encouraged lay organization based on European confraternities, and these groups formed the basis of using devotional images and objects.Footnote 78 Rosary prayer was a routine for these groups.Footnote 79 Nishimura points out that rosary practice had been heavily promoted by the Jesuit fathers even before the entry of Dominicans in 1602, as Jesuits' catechistic manual Doctrina Christan attests.Footnote 80 The use of the rosary and devotional images among lay groups likely affected their oral formulation of THK.Footnote 81

The practice of the rosary yielded a splendid illustration of its fifteen mysteries made by an anonymous Japanese artist after 1623 (Fig. 2). These kinds of works, due to their reflection of European modeling technique and their own refinement, have drawn the attention of art historians far more than the aforementioned Maria-Kannon statuettes.Footnote 82 While discussing this painting, Nishimura makes an interesting observation that its composition reminds him of Taima Mandara (Fig. 3), which is not exactly the Mandala of Esoteric Buddhism but a topographic representation of Amida's splendid Pure Land.Footnote 83 He further recounts that when a small Christian community in eastern Nagasaki province was disclosed in 1657, an inspector dispatched to the village reported that a Taima Mandara was hanging on top of a Christian image, thus hiding the latter. Furthermore, the inspector revealed that the Christian family of the house believed in the miraculous healing power of this Buddhist Mandara.Footnote 84 Nishimura pays attention to the latter fact and suggests that these underground Christians were using Mandara to promote Christian teachings. If so, the conflation of two religions was already well underway by the middle of the seventeenth century, at least in the realm of their visual imagery. Mandara, resembling the Fifteen Mysteries of the Rosary, did not simply disguise the latter as the Maria-Kannon statuette did, but it was incorporated into their Christian belief system, or vice versa.

Fig. 2. Fifteen Mysteries of the Rosary, color on paper, 75 × 63 cm, sixteenth century, made by an anonymous Japanese painter, National Historical Study Center, Kyoto University Museum. Courtesy of Kyoto University Museum.

Fig. 3. Schematic representation of a typical Taima Mandara, distributed by Taimadera, Nara prefecture, Japan. Courtesy of Dr. Elizabeth ten Grotenhuis.

The inspector did not record what kind of Christian image had been covered by this Taima Mandara, but Nishimura points out its strong compositional similarity to the Fifteen Mysteries of the Rosary (Fig. 2), thus implying the possibility of their association, as in the case of Maria-Kannon. By formal similarity, he refers to the vertical and horizontal grids along the edges of Mandara, in which Buddha Sakyamuni expounds and shows to Queen Vaidehi the sixteen views of Pure Land in due sequence. This indeed resembles the image of the rosary mysteries, chaining fifteen grids of contemplative themes in sequence. The assumption that Taima Mandara was hiding or even substituting The Mysteries of the Rosary ascribes the interchangeability of two images to their formal similarity, exactly as scholars have explained the rationale of Maria-Kannon.

Rather than the similar grid structure, however, I would like to turn to the common characteristic of methodic visualization practice found both in the rosary prayer and the sixteen-view visualization of Contemplation Sutra 觀無量壽經, for which Taima Mandara was often used as a guiding visual manual.Footnote 85 This sutra and its iconography of Taima Mandara had the strongest appeal and enduring popularity in Japan, far more than in China or Korea. Earlier Pure Land patriarchs in Japan revered this sutra, as did Shinran, the founder of True Pure Land.Footnote 86 Even though Honen urged the laity to practice Nembutsu rather than the more complicated, sequential method of Pure Land visualization, the latter appears in a series of popular Pure Land Rebirth Stories 往生傳 dating from the tenth to the twelfth centuries.Footnote 87 Furthermore, the iconography of Taima Mandara, originally named Bianxiangtu 變相圖, is hard to find in China and Korea after the fourteenth century, but in Japan it continued to be produced and circulated up to the eighteenth century, and even to the present.Footnote 88 Even if the Japanese were not actually practicing the devotional visualization with Taima Mandara, the act itself of beholding the sixteen sequential features of the paradise depicted in the painting closely resembles Contemplation Sutra's meditative method.

The rosary as prayer consists of repetitive sets of the Ave Maria with the Pater Noster intervening. While reciting these sets of prayers, practitioners are supposed to visualize the mysteries of the rosary, which are basically the sequential themes drawn from Christ's and Mary's life narrative.Footnote 89 Interestingly, the visual representations of the fifteen mysteries of the rosary have been frequently used to facilitate the process of mental visualization or contemplation. This method of mental visualization was likely underscored by the Jesuits in their instruction of Japanese laymen since the same method constituted the core of the order's spiritual training. In Spiritual Exercises, which was originally written by the order's founder St. Ignatius of Loyola as an initiation manual for novices, the saint lays out a methodology creatively developing the long medieval tradition of envisioning, specifically visions of Pseudo-Bonaventure and Ludolph of Saxony.Footnote 90 His method of compositio loci could be easily applied to the prayer of the rosary and enhance the latter's powerful affect. St. Ignatius directs as follows in the manual:

The first prelude is a composition made by imagining the place. Here we should take notice of the following. When a contemplation or meditation is about something that can be gazed on, for example, a contemplation of Christ our Lord, who is visible, the composition consists of seeing in the imagination the physical place where that which I want to contemplate is taking place. By physical place I mean, for instance, a temple or a mountain where Jesus Christ or Our Lady happens to be, in accordance with the topic I desire to contemplate.Footnote 91

In this envisioned space, the holy personages are to reenact the biblical narrative.

At this point, the practitioner should further envision him- or herself inside the mental space to join the holy events. Such participation in the mental imagery is most vividly spelled in the moment of Christ's nativity, which also forms one of the Joyful Mysteries of the rosary. “I will make myself a poor, little, and unworthy slave, gazing at them, contemplating them, and serving them in their needs, just as if I were there, with all possible respect and reverence.”Footnote 92 Thus, the composition of place demands that the practitioner not only imagine space but also enter the mental imagery and engage in various activities such as journeying, witnessing, and even contact with the holy personage in the reenactment of the salvation history. Such an active mental engagement, when applied to the rosary, likely magnified the persuasion of contemplating fifteen narrative themes. After all, rosary is a compendium of salvation history recreated in mental imagery. For a similar purpose, the Jesuits produced quite an elaborate visual manual of the rosary in China, Metodo de Rosario 誦念珠規程, published by Ricci's colleague João da Rocha (1565–1623) in 1608.

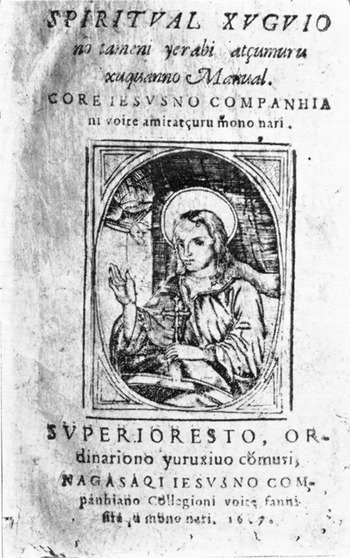

Also in Japan, the Jesuits produced not only the visual images of the fifteen mysteries of the rosary but also its illustrated manuals. One such manual, published in the Jesuit College of Nagasaki in 1607, is particularly noteworthy since it urged the application of the Ignatian method to the rosary. The manual is entitled spiritval xuguio no tameni yerabi atcumuru xuquan no mannual (translated as spiritual exercise, a manual of Bead-Garland selected and collected for it [spiritual exercise]Footnote 93 (Fig. 4). This title demonstrates the typical Jesuit language in Japan—a mixture of Latin or Portuguese transliteration with Japanese. Between the first and the last words (spiritval and mannual) appear Japanese words. Rosary was translated as “bead-garland” 珠冠 (Shukan). Especially interesting are the first two words, spiritval xuguio, the latter of which in Japanese means training or exercise 修行 (Shugyo). This illustrated manual of the rosary, which contains fifteen small engravings representing the mysteries and verbal instructions, places the Ignatian title, spiritual exercise, on the top of the book cover in capital letters, and it places the reference to the rosary below in lowercase letters.

Fig. 4. Title page of Spiritval Xuguio, printed at the Jesuits' Nagasaki college in 1607, Oura Cathedral in Nagasaki. Courtesy of Oura Cathedral.

Such labeling suggests that the Jesuits were indeed underscoring their meditative methodology of visualization in their instruction of the Japanese Christians in the same manner as they did with European believers. The manual begins by explaining that it was published for lay believers' use in meditation 默想 on the fifteen mysteries. The book outlines the meditative method of visualization and its merits:

The people in our age, who are not able to see the Lord in person … nonetheless by visually meditating on what the Lord did, what kind of pains He suffered, and what words He gave us when He was living in the world, [by such a method] they can receive the teaching as they could have received it directly from the Lord in person. The people in our age can be illuminated by the [divine] light and receive the way to the teaching. This kind of contemplation becomes like a clean mirror. When we face this mirror, we can see so many things, not visible by our physical sight, through the eyes of wisdom and understand them. And we can eventually improve our way of life, as St. John said (1 John 2:6): Whoever says, “I abide in Him,” ought to walk just as He walked.Footnote 94

Interestingly, the Ignatian method of visual meditation is related to a passage in the New Testament. In this context, “walk just as He walked” is not merely a metaphor, but it refers to the actual immersion or participation in the visualized scenery of biblical events. Nishimura also observes that the core of the rosary practice was understood as meditation, called mechitasan by underground Christians, rather than mere repetitive sets of verbal prayer.Footnote 95

Similarly, the Contemplation Sutra of Pure Land Buddhism teaches the method of visualizing the sixteen views of Amida's Pure Land as a practice to assure the practitioner of rebirth in the paradise. In this method, practitioners visualize the sixteen views of paradise in a prescribed sequence and often repeat the chanting of Nembutsu 念佛, which means, “I relinquish myself to Amida Buddha” (or sometimes “Kannon”).Footnote 96 Nembutsu is often literally translated as the invocation of Buddha's name, but in fact it is a complete sentence or statement with a verb Namu (Chinese: Nanwu) 南無, thus comparable to “ora pro nobis peccatoribus nunc et in hora mortis nostrae” in the rosary. Pure Land Buddhism emphasized the importance and efficacy of such devotional practices as contemplation, dharani-chanting, and Nembutsu as ways to assure one's salvation. Contemplation Sutra asserted that the practice of visualizing the Pure Land would absolve the supplicants of accumulated sins and enable them to achieve salvation, that is, rebirth in the Pure Land.Footnote 97

The sixteen stages of visualization begin with the contemplation, not of the imaginary, but of the actual sun setting in the West, which is the direction where Buddha Amida resides. This stage serves as a triggering device to immerse the practitioner in meditative visualization. The following stages unfold elaborate and fantastic descriptions of the water, ground, trees, and beautiful pavilions in the Pure Land, which are all radiant with multi-colored, gleaming crystals and jewels. I will cite here the fifth stage, which instructs the practitioner to envision the eight lakes in the Pure Land. This part is especially important since the believer will be reborn inside a lotus flower floating on one of these lakes.

There are eight lakes in the land of extreme delight [that is, Pure Land]. Each lake's water is made of seven jewels. That soft jewel-water comes out of the wish-granting orb and divides into fourteen streams. Each stream makes seven jewel colors. The waterway is made of gold and below it the bottom sands are all composed of multi-colored diamonds.

極樂國土有八池水。一一池水七寶所成。其寶柔軟從如意珠王生。分為十四支。一一支作七寶色。黃金為渠。渠下皆以雜色金剛以為底沙Footnote 98

All these hyperbolic descriptions serve as a psychological device to initiate the practitioner's imaginative meditation.

The text of the sutra aims to assist practitioners in building in their minds the imaginary topography of the Pure Land, as vividly as if they were to perceive a picture or even walk on its holy ground. In this regard, its direction to create a mental space resembles the Jesuit method of compositio loci very closely.Footnote 99 Furthermore, stages fourteen to sixteen are assigned to the visualization of the practitioner him- or herself at the time of death and consequent rebirth in the Pure Land. In this stage, the meditation practitioner visualizes him- or herself within the holy topography and becomes a part of his or her own imaginative meditation, as the trainee of the Spiritval Xuguio is urged to walk with and even talk to the holy personage inside the pictured imagery. Significantly, the bodhisattva Kannon plays the key role in the believer's transition from this world to the Pure Land, which I will discuss in the last section with regard to the iconography of Welcoming Descent (Fig. 6).

According to the believer's spiritual aptitude and accumulation of sin, there are nine levels of rebirth: three grades subdivided into three ranks. I will quote here the case of a person belonging to the lowest rank of the highest grade.

Shortly he himself sees his body seated on a golden lotus flower. After he sits, the flower closes. Following the Buddha, he attains rebirth in the seven-jewel lake. … After twenty-one days … he travels throughout the ten quarters of the universe and worships all the Buddhas. In front of these Buddhas, he hears the most profound dharma.

即自見身坐金蓮花。坐已華合。隨世尊後即得往生七寶池中 … 於三七日後 … 遊歷十方供養諸佛。於諸佛前聞甚深法Footnote 100

As instructed by the Spiritval Xuguio, the practitioner not only visualizes the holy topography but also enters the visualized Pure Land to be reborn, to travel, and to meet with and hear from the buddhas. This moment is called the “Receiving of Revelation” 受記, which I will discuss in the last section in relation to a THK motif.

As I mentioned above, the panoramic Pure Land had been abundantly represented since the time of the Tang Dynasty in order to assist the sixteen-view visualization, but it was especially in Japan that this iconography, indigenously renamed as Taima Mandara (Fig. 3), enjoyed the greatest popularity and continued to be produced as late as in the eighteenth century.Footnote 101 Just as Taima Mandara did not merely represent the Pure Land but also assisted visually-oriented meditation, so too did the Fifteen Mysteries of the Rosary represent more than an abridged version of the biblical narrative as it also served as a visual manual for contemplative prayer. They both served to facilitate a meditation practitioner's mental creation of holy space and encounter with the holy personages therein.Footnote 102

To conclude, the methodic contemplations that proceed in the prescribed sequences of the fifteenth and sixteenth stages bring the rosary and the sixteen-view visualization very close to each other. Therefore, their visual manuals, namely the Fifteen Mysteries of the Rosary (Fig. 2) and Taima Mandara (Fig. 3), likely imprinted the Japanese Christians not merely with a similar appearance, but with their similar and even identifiable devotional methodologies of visualization, often combined with incantatory prayer. In the first instance, their formal similarity could have led to the possible association of Taima Mandara with the Mysteries of the Rosary. However, as the process of mutual acculturation or conflation intensified due to Japanese Christians' isolation from the Church's guidance, their paralleling devotional practices and beneficiary rewards could have further facilitated their iconographic interchange or proximity.

The elements of repetitive prayer and visualization in the rosary also relate to another devotional practice of Pure Land Buddhism: the dharani prayer dedicated to Kannon. Higashibaba points out that Buddhists' repetitive dharani was analogous to Medieval Latin prayer, as both were perceived by the illiterate common populace to have some wonder-working effects.Footnote 103 Kannon is comparable to Mary, not only in her female appearance and personification of compassion, but also in the devotional practice dedicated to her. In this regard, the penitential prayer to the thousand-armed Kannon (Japanese: Senju Kannon) is noteworthy. The pilgrimage to Kannon sites and the prayer to her were believed to absolve one of accumulated sins, which otherwise would prevent one from being reborn in the Pure Land of Amida.Footnote 104 Over half of Saikoku Kannon pilgrimage sites are dedicated to Senju Kennon, to whom penitential dharani prayer was to be directed.Footnote 105 Both Saikoku pilgrimage and the veneration of Senju Kannon continued up to the seventeenth century, and the practice of dharani prayer to Senju Kannon is mentioned amply in the Japanese miracle stories.Footnote 106 Such a Kannon dharani was supposed to be repeated in a set number while beholding or visualizing the image of Kannon.Footnote 107 Thus, the dharani prayer to Kannon also aimed at the absolution of sins through the methodology of repetitive prayer combined with visualization, which is the very essence of the rosary.

As I mentioned at the head of this section, the yearly practice of treading on Christian icons made the penitential prayer and rite important for underground Christians. In this regard, the absolutional efficacy of the rosary likely held great value to them, and in their practice of the rosary in front of Maria-Kannon, they must have been reminded of the like efficacy attributed to the Buddhist prayer dedicated to the porcelain deity (Kannon), who could also transform into Senju as much as into Mary. The growing need to repent, so pressing for the underground Christians under persecution, brought them even closer to the absolutional devotion to Kannon, who posing as Mary received their penitential prayer of the rosary.

IV. Amida and Christ as Savior from Heaven

Underground Christians not only substituted the Son-bringing Kannon as Mary but also Buddha statues as icons of Christ. One of them has been identified as Amida, but the others are hard to identify due to their small size and lack of iconographic details (Fig. 5).Footnote 108 Unlike the concern among scholars to identify the female deity as Kannon, scholars are quite indifferent to the identity of this Buddha. I am arguing that this Buddha was none other than Amida and that its identification should not rely on iconographic analysis, which is almost impossible in these simple statuettes, but in the way underground Christians perceived the deity with their memory of Christianity in conjunction with their cultural heritage of Buddhism. In this light, the aforementioned seventeenth-century seated Amida statue donated to Chodoku temple by a Christian girl's father also may have been perceived by the family as impersonating the Christian God.Footnote 109

Fig. 5. Amida-Christos, wood, height 13.6 cm, Tokyo National Museum. Courtesy of DNP Art Communications.

Due to his role as the savior and lord of afterlife paradise, Amida was the most appealing Buddha to the Japanese populace.Footnote 110 Furthermore he is accompanied and served by Kannon, also the most popular bodhisattva in this country. According to the legend of Zenkoji's wonder-working Amida triad, Amida was the first Buddha icon that was transmitted to Japan from the Korean kingdom of Paekche with the introduction of Buddhism in the year of 538.Footnote 111 Such a legend was probably invented later, as the devotion to Amida grew stronger and even dominant in Japan. Earlier, I mentioned that St. Francis Xavier adopted the name of Buddha Dainichi 大日 (Sanskrit: Mahavairocana) as that of the Christian God, which, despite the saint's great embarrassment later, was not a totally misleading translation. Dainichi's role as the center and origin of the universe resonates with the neo-Platonic idea of God as the One. However, if the issue is not cosmology but soteriology, which naturally concerns the common populace more personally, Amida rather than Danichi was the most suitable as an alternative name for the Christian God.

Amida, unlike other Buddhas, has two distinctive theological aspects that are closely analogous to Christianity. First, the terms of salvation do not rely on the part of the believer, but on the compassion and will of Amida.Footnote 112 When he was still a bodhisattva, he made a vow to this effect.

If I become a Buddha and there are men of ten quarters who hear my name, keep in mind my land, foster [their minds] in the origin of virtue, yearn to be born in my land with utmost heart, and yet do not achieve it, I won't attain the true enlightening.

設我得佛。十方眾生聞我名號係念我國殖諸德本。至心迴向欲生我國。不果遂者。不取正覺Footnote 113

Human beings were understood to be living in the degenerate age of law and thus incapable of achieving their own Buddhahood.Footnote 114 In this distressful world, the only salvation possible for sinful men lies in the total reliance on Buddha Amida.Footnote 115 This is an unusual and even alien idea to the original Indian Buddhism, in which one has to achieve his or her own salvation by realizing the root of earthly pain and escaping the vicious circle of karma and reincarnation.

When Catholicism was introduced, the Japanese likely noted the similar existence of one supreme deity as the savior in both religions. Higashibaba notes that the concept of one supreme divinity was already familiar to the Japanese in the existence of Amida Buddha of Pure Land.Footnote 116 Furthermore, devotional practices in Pure Land Buddhism, very much like good deeds in Catholicism, counted as strong merits to assure rebirth in the Pure Land. In the original scriptures, Amida's avowal specifies that one should “exert all the meritorious virtues” and that they should not have “committed five treacherous sins and blasphemed the true dharma” in order to be reborn in Pure Land.Footnote 117 The constant practice of Nembutsu 念佛 rewards the believer with an encounter with Amida in his or her dream.Footnote 118 Lifelong practice of Nembutsu ultimately leads to rebirth in the Pure Land.

Strictly speaking, True Pure Land patriarch Shinran taught that the practice of Nembutsu was not to attain rebirth in the Pure Land, but that it was a repeated expression of gratitude for salvation already granted by Amida's vow.Footnote 119 However, his heavy emphasis and urge to practice Nembutsu could be interpreted a bit differently by less erudite laity. According to him, Nembutsu was the one, exclusive religious act that could lead to the rebirth in Pure Land, even for those who have violated Buddhist precepts. In his Lamenting the Deviations 歎異抄, he said:

The moment we believe that we can be saved and enlightened through the power of Amida's Original Vow, and conceive the desire to call upon his name, he at once deigns to save us… .

Therefore, if we truly believe in the Original Vow, there is no need for other good works. The Nembutsu is absolutely effective. What good works can compare with it?Footnote 120

While asserting a kind of predestined salvation, Shinran kept urging his followers to practice Nembutsu, which thus sounds like a required qualification to invoke Amida to “deign to save us.” Indeed, devotional practices such as Nembutsu, Pure Land visualization, chanting, and copying of sutra appear frequently as rebirth-bringing good deeds in the aforementioned popular Pure Land Rebirth Stories 往生傳.Footnote 121

Higashibaba notes the similarity between Nembutsu practice and Catholic good deeds since both involve and require human effort.Footnote 122 The power and efficacy of Nembutsu, similar to the dharani of Kannon, were underscored in many popular miracle tales. Another powerful devotional practice to attain one's rebirth in the Pure Land is the aforementioned sixteen-view visualization of Pure Land, for which Taima Mandara was produced and put to use. Contemplation Sutra teaches the practice of sixteen-view visualization as the way to rebirth in paradise. Again, even if the Japanese populace were casting aside the more complex practice of visualization in favor of simpler Nembutsu, the production and contemplation of the painted panorama of Pure Land already constitute the beneficiary deeds.

The second aspect of similarity lies in the concept of afterlife paradise. As we saw above, Amida's vow from The Sutra of Infinite Life 無量壽經 promises rebirth in his Pure Land as an afterlife reward, which is reminiscent of the eschatological vision of the heavenly Jerusalem in Christianity.Footnote 123 Both Ebisawa and Higashibaba regard Christian afterlife salvation as paralleling the theology of Pure Land Buddhism.Footnote 124 It is important, however, to note that in Pure Land Buddhism the rebirth in the Pure Land is not the final goal. Since sinful men do not have the capacity to be freed from the eternal chain of karmic reincarnation and suffering, Amida allows them to be transferred to his paradisiacal Pure Land, where reborn believers will receive the profound teaching 受記 and eventually proceed to attain nirvana.Footnote 125 However, common folk were far more intrigued by the splendor of Pure Land as the reward of their faith rather than the theological liberation of nirvana, which is the extinction of being.

In this regard, Amida Buddhism and its concept of Pure Land are sometimes viewed as a Buddhist protest against the “emptiness” of nirvana.Footnote 126 Indeed, the Jesuits in Japan understood Buddhism as nihilism.Footnote 127 Valignano observed that Buddhist monks were obscure about the afterlife and that some even seemed to believe life ended with this one.Footnote 128 It appears that Valignano encountered the idea of nirvana, that is, extinction. Pessimistic views on life and suffering led to the concept of extinction as the salvific consummation in Indian Buddhism, but this profound teaching could be appreciated and embraced only by the learned few. Ordinary folks' ideas and afterlife expectations were to be vested in the more vividly colorful vision of Pure Land, as is fantastically detailed in Pure Land sutras.

The popular appeal of Amida as savior and lord of heaven is attested to in the ample production and circulation of Amida's Welcoming Descent images dating to the Kamakura period. This theme continued to be painted in Japan up to the eighteenth century (Fig. 6), even though it was not frequently represented in China or Korea after the fourteenth century.Footnote 129 Its iconography was derived from Amitabha's nineteenth vow appearing in the Sutra of Infinite Life.

If I become a Buddha and there are men of ten quarters who strive for the enlightening, exert all the meritorious virtues, make a wish to be born in my land with utmost heart, and at the time of their death, if I do not appear in front of such men with the great [heavenly] host around, I won't attain the true enlightening.

設我得佛。十方眾生發菩提心修諸功德。至心發願欲生我國。臨壽終時。假令不與大眾圍遶現其人前者。不取正覺Footnote 130

Fig. 6. Ike Taiga (1723–1776), Welcoming Descent of Amia Triad, ink on paper, 72 × 31.8 cm, Kumita Collection, Tokyo. Photograph by Patricia J. Graham.

In its typical iconography, Amida, attended by his bodhisattvas, descends from heaven to receive the dying believer. Most significantly, bodhisattva Kannon is holding and offering to the dying the lotus pedestal, which is a kind of vehicle that transports the believer to the Pure Land. As we read from the passages of Lotus Sutra and Contemplation Sutra, the believer is to be reborn in the lotus blossom of the jewel-colored pond. This motif likely strengthened the belief in Kannon's role and power in the process of salvation.

The imagery of Amida as the savior and receiver of the dead was so firmly rooted in the Japanese's minds that Fr. Frois often encountered it even among the converts. He recounted a story of a man living in the Bungo area in 1584:

In the region, a pagan young man fell gravely ill. Since this man had heard the teaching of Christianity before, he called in a priest to receive baptism before death. At the time he said loudly [to the priest], “Three devils appear and tell me to recite Amida's name! I told them I don't believe in Amida, but I believe firmly in Jesus and Mary. So [you] be the witness to my words!” He recited the name of Jesus and Mary many times and drew his last breath.Footnote 131

He recorded another story of a woman convert in the same year:

The lady was a fervent worshipper of Buddha, but after learning the teachings of Christianity, she decided to convert. When a priest came to town to give her baptism, he heard that she had visited a Buddhist temple earlier in the day and prayed in front of a Buddha statue. The priest asked her about it. Without denying it, she answered him. “I heard that two things are important to Christians. First, uprightness and secondly, truthfulness. I have worshipped Amida for thirty years and believed that He is the lord of salvation. Since I decided now that I won't visit a Buddhist temple again, I thought it is an upright act to go visit Amida Buddha and bid Him farewell. Also I made a vow before that I would visit the temple as often as possible. So in order to be truthful to my promise, I visited the temple today.Footnote 132

To this convert, Amida had been, and probably still was, the lord of salvation since there can be two or more lords of salvation in the Japanese religious world. Even after the decision to convert, her respect for Amida and his power remained, which of course would change with the guidance of the priest sooner or later.

Such a belief in Amida as cultural heritage would not have diverted the Japanese Christians but, on the contrary, predisposed them to easily understand and sympathize with Christian soteriology and eschatology. The aforementioned THK presents the verbal and visual imageries of underground Christians, which imply the fusion or even mutual acculturation of two religions on the basis of similar theological terms. Though not committed to writing before 1800, THK originates in the earlier era of persecution.Footnote 133 It was based not only on the mysteries of the rosary but also on Doctrina Christan of 1592, the Jesuits' catechistic textbook of the Japanese mission.Footnote 134 The philological studies of THK's language indicate that it was composed in its current form sometime in the seventeenth century, but drew on the devotional literature and discussions circulating in the latter half of the sixteenth century.Footnote 135 As these underground Christians were gradually isolated from the Jesuits and the Church, they had to fill in the gap of their fading memory of catechism, such as Doctrina Christan, with what they were already familiar with. It was in this process that the elements of Pure Land Buddhism came to the fore and fused with their isolated Christianity.

THK uses a number of Buddhist terms that imbue the whole work with strong Buddhist connotations.Footnote 136 For example, this earthly realm is called Shaba 娑婆, fate is simply Karma 業, abbot is Osho 和尙, and St. Michael is conducting a Buddhist meditation, Sazen 座禪.Footnote 137 However, the most significant is the terminology and imagery that concern God the Father and Christ. In the beginning of THK, God the Creator is referred to as Ikibotoke 生佛, the living Buddha, and he created the world and the angels. “‘Ten thousand angels should be brought into being.’ Then it happened according to His Buddha power. Since He was a freely existing, living Buddha, He created according to His will ten thousand angels. In total, they were of thirty-three kinds of manifestations.”Footnote 138 In addition to his name, his work is strongly reminiscent of Buddhist concepts. The angels he created out of his will have thirty-three appearances, which originate in the thirty-three manifestations of bodhisattva Kannon.Footnote 139 For the Japanese fully ingrained within the Buddhist heritage, the relationship between God and an angel could easily be compared to that of Amida and Kannon. Also, God's capability of creation is called Buddha's power 佛力.Footnote 140 Such an abundant use of Buddhist terms is quite noteworthy given that after the term Dainichi for God caused problems, the Jesuits preferred to use transliterations of the original Latin, thus Deusu for Deus, orassho for oratio, and so forth. Once the isolation began, Buddhist terminology and imagery floated to the surface again.

Furthermore, three episodes in THK carry strong allusions to Amida's Welcoming Descent, which I think is more significant than the terminological adoptions. After Mary displays her supernatural power to bring snow in the middle of summer, God sends from heaven a flower vehicle that transports her to heaven:Footnote 141 “While they were thus making noises, Mary fled away. From Heaven came down a flower vehicle, on which she rode, and it went toward Heaven.”Footnote 142 Tanigawa points out that this motif was probably inspired by Amida's Welcoming Descent imagery.Footnote 143 The lotus pedestal, which Kannon offers to the dying believer, is after all a flower vehicle to transport him or her to paradise (Fig. 6).Footnote 144 Also at the end of THK, Christ brings the ten thousand innocents, three magi, two farmers (probably the shepherds who received the announcement of his birth), and Veronica all up to heaven.

To the ten thousand children, slaughtered by King Yoroutetsu [that is, Herod] and wandering in Koroteru, the Lord gave names and brought them upward to Him into Paradise. Furthermore, He let the innkeeper, who accepted the Family at the time of His birth, three Kings from the three Lands, two farmers, and Veronika all ride up to Heaven. He brought them all to Him into Paradise.Footnote 145

The THK concludes with the happy transport of all good men to heaven as an afterlife reward, which resonates in general with Pure Land Buddhist soteriology.

When the young Christ and Mary were chased by their enemies, God the Father brought Christ up to heaven and conversed with the Son face-to-face 面談. Then God endowed Christ with a crown and an office suitable for his status.Footnote 146 This motif, having no origin in the Gospels or Catholic tradition, appears to reflect the “Receiving of Revelation” 受記 in Contemplation Sutra. When the believer of Amida is reborn in the Pure Land, he meets with Amida there, and directly receives from him the revelation of truth.Footnote 147 A similar motif appears in another part of THK, in which the elect will be awarded a blessing in paradise at the end of the world.Footnote 148 “Those people on the right who received baptism will accompany Deusu [Deus] to Paraiso [Paradise] where, once judged, their good works will be the basis of the ranks they will receive. It is guaranteed that they will all become buddhas and know unlimited fulfillment for eternity.”Footnote 149 The “Receiving of Revelation,” which was phrased as “know unlimited fulfillment,” matters since it further leads to the stage in which “they will all become buddhas.” Tendai Monk Genshin 源信 (942–1017) also counted it among the ten pleasures of rebirth in Pure Land in his Essentials of Rebirth in Pure Land 往生要集:

First is the pleasure of being welcomed by many holy ones… .

Third is the pleasure of obtaining in one's own body the ubiquitous supernatural powers of a Buddha… .

Seventh is the pleasure of joining the holy assembly.

Eighth is the pleasure of beholding the Buddha and hearing the Law.Footnote 150

Also in Genshin's words, the believer beholds Buddha face-to-face and hears the revelation, which will enable to him to proceed to the enlightenment. The believer is also given supernatural power in paradise. Likewise, Christ and the elect in THK receive a crown and proper ranks from God the Father in heaven.

Even though THK has strong Buddhist elements, scholars have emphasized that THK has a clear anti-Buddhist message, and that therefore THK does not attest to a true transculturation or fusion of two religions. This opinion is based on the episode of Christ in the temple, in which the young Christ defeats—rather than Jewish rabbis—a Buddhist monk who was teaching the efficacy of Amida Nembutsu. However, a close reading of this section reveals much to the contrary. In the episode, the young Christ encounters a Buddhist monk, who taught that if one practices Amida Nembutsu, a boat of salvation would come to him at the time of his death and transport him or her to paradise, which is the recurring motif of Welcoming Descent.Footnote 151 Young Christ refutes this view, but ironically in his account of refutation he says that the true God is the Buddha 佛, who would complete the salvation of men in the coming world: “Then said the Lord, ‘The Lord of Heaven, whom men revered as Buddha, this One is the true Buddha, who accomplishes the salvation of mankind in the future world. … This Hotoke [that is, Buddha] has created mankind, all things, and everything there is, according to His will.’”Footnote 152

Concerning this phrase, Miyazaki observes that underground Christians were naming their God Buddha in distinction to Buddhists' Buddha, since the former “accomplishes the salvation of mankind.”Footnote 153 However, such a distinction does not seem to hold, since, in Buddhist teaching, the one Buddha who endeavors to redeem human beings and awards them the “future world” reward of paradise is none other than Amida. In light of this, Christ in this episode is not exactly negating the faith in Amida and his power to transport the believers to paradise, but simply refuting the monk who is teaching Nembutsu as the way to salvation. In this section, Christ refers to God as Hotoke 佛 (Buddha) three times. Nishimura points out that underground Christians' use of Hotoke as God's name not only shows their attempt to disguise, but also their infusion with Buddhism. He also ascribes such infusion with Buddhist rituals and terms to their isolation from the Church's teaching.Footnote 154

V. Conclusion

Japanese Christians were completely isolated from foreign priests by the late 1630s, and by 1700 the fusion of underground Christianity with Buddhism was well in advance, as exemplified in their Mandara usage and THK's language ingrained in Buddhism. This process of conflation would continue and eventually lead to the religion of Kakure Kirishitan, who refused to rejoin the Catholic Church after the ban was lifted in 1873. They could not identify themselves either with Catholics or with Buddhists, so they chose the distinct way of continuing their own religion referred to as hidden or secret Christianity. On the surface, their exclusive choice did not seem to fit the Japanese religious culture, in which multiple belief systems syncretistically assimilated and co-existed.

However, paradoxically, their emergence in Japanese history reflects the very characteristic of the nation's religious culture. Though specific historical conditions played a large role in the process, Catholicism and Buddhism were conflated in their religion since they saw the universal, common elements in the theology, practice, and visuality of the two religions. In other words, the underground Christians' historical continuity with the current hidden Christians is the outcome of the Japanese view itself that all religions are different languages that speak basically the same truth.Footnote 155