Introduction

A business model is a conceptual tool used to draw together the logic behind a business enterprise that defines how it will create value for its customers, profit for its shareholders, and how it will allocate key resources and employ processes to achieve its purpose. From an academic perspective, the business model concept remains a work in progress. However, it has captured the attention of both policy makers and practitioners because without appropriately designed and effective business models, economic growth and business sustainability will be adversely impacted (Teece, Reference Teece2010).

This paper contributes to a better understanding of the nature of the co-operative and mutual enterprise (CME) business model, a unique type of business form that has a long history and global reach (Birchall & Simmons, Reference Birchall and Ketilson2011; International Co-operative Alliance [ICA], 2015). Despite this, the CME business model remains poorly understood, and has been marginalised within the economics and management literature (Kalmi, Reference Kalmi2007). These enterprises have been identified as having a potentially significant role in alleviating poverty (Birchall, Reference Birchall2004; Birchall & Simmons, Reference Black and Robertson2007, Reference Birchall and Simmons2009). They have also been proposed as offering a useful tool for economic development (Gringras, Carrier, & Villeneuve, Reference Gringras, Carrier and Villeneuve2008; Kangayi, Olfert, & Partridge, Reference Kangayi, Olfert and Partridge2009; Vieta, Reference Vieta2010; Tonnesen, Reference Tonnesen2012). However, they have also been identified as having inherent ‘generic’ problems or weaknesses in their business model (LeVay, Reference LeVay1983; Cook, Reference Cook1995; Nilsson, Reference Nilsson2001; Ortmann & King, Reference Ortmann and King2007). Their competitiveness and economic efficiency in relation to investor-owned firms (IOF) has also been questioned (Soboh, Lansink, & Van Dijk, Reference Soboh, Lansink and Van Dijk2012).

The CME is a ‘hybrid’ that can fill the gaps between state-owned enterprises (SOE), not-for-profit social enterprises (NFPSE) and for-profit IOF (Levi & Davis, Reference Levi and Davis2008; Novkovic, Reference Novkovic2008). It has been viewed as offering greater resilience and stability in comparison to many alternative business models (Birchall & Ketilson, Reference Birchall and Simmons2009; Birchall, Reference Birchall2013; Brown et al., Reference Burt2015). The CME business model is also now being actively promoted by governments in the Asia-Pacific region as a complementary organisational form alongside other corporate models (Michie & Lobao, Reference Michie and Lobao2012). For example, Malaysia has positioned the CME sector as a core part of its economic development strategy with the launch of the National Co-operative Policy in 2002 and will continue until 2020 (Othman, Mansor, & Kari, Reference Othman, Mansor and Kari2014).

However, despite the potential value of the CME to economic development, relatively little attention has been given to a systematic analysis of the business model structure that underlies this type of organisation. There is a gap in the literature associated with the design of the CME business model, and in particular the attributes it has that make it of potential value. The aim of this paper is to explain the key elements of the CME business model and in doing so address the following research questions:

1. What are the key attributes, components or building blocks that comprise the CME business model?

2. How might the CME business model be designed to ensure its sustainability and resilience?

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. First, we explain the nature of CMEs before turning to an overview of the business model concept and its evolution. We then review the business model conceptual framework developed by Osterwalder and Pigneur (Reference Osterwalder and Pigneur2010), before discussing the CME business model and how it differs from other types of enterprise. The paper then outlines the CME business model in detail, before discussing the theoretical and applied contribution that this framework makes. Finally, to conclude, the contributions of the paper and implications for further research are discussed. This work is conceptual in nature.

What is a CME?

The acronym CME has its origins in a paper published by Co-operative Futures (2000), as a potential framework for research, policy and practice. Like the acronym SME, for small and medium enterprises, the acronym CME helps to unite the otherwise disparate co-operatives and mutual enterprise sectors (Yeo, Reference Yeo2002). It has now started to gain more common use in academic and industry circles (Ridley-Duff, Reference Ridley-Duff2012, Reference Ridley-Duff2015).

The nature and origins of CMEs

Historically, co-operatives can trace their origins back to the Middle Ages, with more recent examples found in France, Scotland and Germany from the 18th century (Gide, Reference Gide1922; Williams, Reference Williams2007), and globally during the 19th century (Fernández, Reference Fernández2014). However, the origins of the modern co-operative business model can be found in the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers in 1844 (Drury, Reference Drury1937; Fairbairn, Reference Fairbairn1994). Founded by self-employed weavers in Rochdale, England, its purpose was to undertake a range of economic and social activities to enhance the well-being of its members (Wilson, Shaw, & Lonergan, Reference Wilson, Shaw and Lonergan2012). The founding principles laid out by the Rochdale Society have remained a blueprint for co-operatives, encompassing: member ownership, democratic governance (i.e., ‘one-member-one-vote’), accumulation of share capital and profit distribution based on patronage, and member education. Both social and economic objectives were inherent in its constitution (Rochdale Society, 1877: 21). With only a few minor changes, the general principles and values established by the Rochdale Society have continued to guide the global co-operative movement (ICA, 2015; Nelson, Nelson, Huybrechts, Dufays, O’shea, & Trasciani, Reference Nelson, Nelson, Huybrechts, Dufays, O’shea and Trasciani2016). Table 1 outlines these principles and values.

Table 1 Co-operative principles

Source: International Co-operative Association, 2015.

These principles have been viewed as a potential alternative to mainstream approaches to economic development during times of crisis such as the Great Depression (Albrecht, Reference Albrecht1937; Drury, Reference Drury1937; Hall & Watkins, Reference Hall and Watkins1937; Miller, Reference Miller1937; Warbasse, Reference Warbasse1937; Heriot & Campbell, Reference Heriot and Campbell2006; Royer, Reference Royer2016). They have also been seen as a guide to success for co-operatives if followed strictly and abandoned at their peril (Drury, Reference Drury1937).

Mutual enterprises, or societies, can also trace their origins back to the Middle Ages, but they emerged strongly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries offering mutual pooled funds for workers and professionals to provide financial, insurance and health services (Grijpstra, Broek, & Plooij, Reference Grijpstra, Broek and Plooij2011). For example, in the United Kingdom, friendly societies such as the Independent Order of Oddfellows, Independent Order of Rechabites, United Ancient Order of Druids and the Ancient Order of Foresters, emerged to offer pharmaceutical, financial and insurance services for their members (Lyons, Reference Lyons2001). During the 1830s and 1840s these organisations spread to countries such as Australia where they offered affordable medicines and medical services (Green & Cromwell, Reference Green and Cromwell1984).

Today, mutual enterprises remain a significant part of the national economy of most countries. For example, in Europe, it was estimated that mutual enterprises provide health and financial services to around 230 million members and policy holders, employ around 350,000 people and underwrite about €180 billion insurance premiums (Grijpstra, Broek, & Plooij, Reference Grijpstra, Broek and Plooij2011).

Some of the key characteristics or principles that define mutual enterprises are summarised in Table 2, where it can be seen that there are many commonalities between the principles that guide the co-operative and those that guide mutual enterprises.

The history of the co-operative and mutual societies is both long and complex, and it is not the purpose of this paper to address it in detail. However, the CME sector is diverse and its history, as illustrated in Britain, suggests a pattern of periods of rapid growth, followed by periods of relative decline. This was often characterised by problematic relations with political movements and trade unions, plus competitive pressure from IOF (Black & Robertson, Reference Borda-Rodriguez and Vicari2009; Gurney, Reference Gurney2012, Reference Gurney2015). This is a pattern found in many countries (Gide, Reference Gide1922; Balnave & Patmore, Reference Balnave and Patmore2008; Birchall, Reference Birchall2011). It is therefore acknowledged that many differences will exist between CMEs, and within the two sub-sectors. Nevertheless, while these differences are acknowledged, it is our view that sufficient common foundations can be found within their underlying business models, to suggest a framework that can assist directors and managers of these businesses to better understand the strategic issues likely to shape their fortunes.

Defining CMEs

While CMEs share many common attributes, they also have some key differences. These are reflected in the definitions that are used for these firms. The International Co-operative Alliance (ICA), founded in London in 1895, acts as the global steward of the Statement of Co-operative Identity. It defines a co-operative as follows:

A co-operative is an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly-owned and democratically-controlled enterprise.

However, this definition does not fully capture the nature of the mutual enterprise (e.g., mutual insurance firms, mutual health insurance funds, building societies, credit unions and friendly societies), which are not co-operatives, and have not traditionally embraced their principles (Birchall, Reference Birchall and Simmons2014). While there is no universal definition of a ‘mutual enterprise’, the European Union defined them as:

Voluntary groups of persons (natural or legal) whose purpose is primarily to meet the needs of their members rather than achieve a return on investment, which operate according to the principles of solidarity between members, and where members participate in the governance of the business (Grijpstra, Broek, & Plooij, Reference Grijpstra, Broek and Plooij2011: 14).

By contrast, the UK government defines the mutual enterprise as follows:

A mutual is a private company whose ownership base is made of its clients or policyholders. The defining feature of a mutual company is since its customers are also its owners, they are entitled to receive profits or income generated by the mutual company. It is owned by, and run for the benefit of its members (UK Government, 2011).

However, there are many different definitions of ‘mutual enterprise’ found around the world.

Unsurprisingly, the definition of a ‘CME’ remains vague, due to the inherent challenge of classifying CMEs, which share a common focus on member economic and social benefit, but also have dissimilarities in relation to some aspects of governance and ownership. Ridley-Duff suggests that CMEs ‘…are defined by a commitment to (or innovative systems for advancing) trade through democratic/inclusive enterprises’ (Reference Ridley-Duff2015: 46). Yet a formal definition does not exist. Birchall (Reference Birchall2011) proposed one for a ‘member-owned businesses’:

A business organisation that is owned and controlled by its members who are drawn from one (or more) of three types of stakeholder – consumers, producers and employees – and whose benefits go mainly to these members” (Birchall, Reference Birchall2011: 3).

For the purposes of this paper, we use as a working definition of a CME:

A co-operative or mutual enterprise (CME) is a member-owned organisation with five or more active members and one or more economic or social purposes. Governance is democratic and based on sharing, democracy and delegation for the benefit of all its members.

The methodological foundations of this study

The conceptual framework of the CME business model described in this paper has been developed from a ‘bottom-up’ methodology the authors have undertaken over a period of approximately 10 years. Commencing in 2008, we undertook a major review of the literature relating to the CME, and examined it against the extant conceptual foundations of the business model (Mazzarol, Reference Mazzarol2009; Mazzarol et al., Reference Mazzarol, Simmons and Mamouni Limnios2011).

This was followed by a large-scale study involving the collection of data and case studies from multiple countries and the publication of a research handbook that examined the co-operative enterprise business model (Mazzarol, Simmons, Mamouni Limnios & Clark, Reference Mazzarol, Simmons, Mamouni Limnios and Clark2014). In the light of this research, revisions were made to the design of the CME business model development canvas and incorporated it within educational programs. The business model canvas described in this paper was subsequently used in an executive leadership and strategy programme for the directors and senior executive managers of CMEs over a period of 4 years. This provided an opportunity to validate the structure and usefulness of the framework with a wide cross-section of CMEs from multiple industries, sizes and countries. It has also been successfully used in consulting projects with directors and executive managers from CMEs, and has demonstrated its usefulness for both established and young businesses as a strategic planning framework.

The business model as a conceptual framework

Before we explain the CME business model it is appropriate to overview the conceptual and theoretical foundations of the business model concept. The historical antecedents of the term business model can be traced back to the middle of the 20th century, with mentions of ‘business models’ found in the works of Drucker (Reference Drucker1954), Bellman, Clark, Malcolm, Craft, and Riccardi (Reference Berman, Kesterson-Townes, Marshall and Srivathsa1957) and Jones (Reference Jones1960). However, despite some ongoing use of the term in the 1970s (e.g., Mulvarney & Mann, Reference Mulvarney and Mann1976), the concept began to find its way into the management literature in the 1990s and 2000s via the field of electronic commerce (Mahadevan, Reference Mahadevan2000). One of the first definitions was provided by Timmers (Reference Timmers1998), who described it as:

An architecture for the product, service and information flows, including a description of the various business actors and their roles; and a description of the potential benefits for the various business actors; and a description of the sources of revenues (Timmers, Reference Timmers1998: 2).

At the start of the 21st century the concept of the business model began to take a prominent role in the fields of innovation and entrepreneurship (i.e., Chesbrough & Rosenbloom, Reference Chesbrough and Rosenbloom2002; Thomke & von Hippel, Reference Thomke and von Hippel2002; Davis, Reference Davis2002a). Academic researchers investigated and analysed the nature of business models. They acknowledged that there was a paucity of agreed definition, other than being largely associated with ‘the logic of profit generation’ (Stewart & Zhao, Reference Stewart and Zhao2000), and an equal paucity of ‘theoretical underpinnings’ (Amit & Zott, Reference Amit and Zott2001).

A review of the literature undertaken by Morris, Schindehutte, and Allen (Reference Morris, Schindehutte and Allen2005) identified an ‘integrative framework’ for understanding the business model concept. This was based around six key questions: (i) how does the business create value? (ii) who is the business creating value for? (iii) what is the source of the firm’s competence? (iv) how does the business competitively position itself? (v) how does the business make money? and (vi) what are the time, scope and size ambitions for the venture? Around the same time other researchers in the field of management and economics were taking an interest in the business model concept (e.g., Osterwalder, Reference Osterwalder2004; Osterwalder, Pigneur, & Tucci, Reference Osterwalder, Pigneur and Tucci2005; Shafer, Smith, & Linder, Reference Shafer, Smith and Linder2005; Hrebiniak, Reference Hrebiniak2006; Teece, Reference Teece2006; Zott & Amit, Reference Zott and Amit2007; Markides, Reference Markides2008). Chesbrough (Reference Chesbrough2007) provided a list of the key ‘functions of a business model’ (see Table 3).

Despite this growing interest in the business model, by the end of the decade Teece (Reference Teece2010) issued a warning and a challenge to academic researchers, and those using the business model concept for start-up ventures and other purposes. He noted that:

The concept of a business model lacks theoretical grounding in economics or in business studies. Quite simply there is no established place in economic theory for business models; and there is not a single scientific paper in the mainstream economic journals that analyses or discusses business models in the sense they are defined here (Teece, Reference Teece2010: 175).

This ‘challenge’ coincided with a flurry of papers published on the topic of business models (i.e., Chesbrough, Reference Chesbrough2010; Nenonen & Storbacka, Reference Nenonen and Storbacka2010; Zott & Amit, Reference Zott and Amit2010; Casadesus-Masanell & Ricart, Reference Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart2010; George & Brock, Reference George and Brock2011; Zott, Amit, & Massa, Reference Zott, Amit and Massa2011; Amit & Zott, Reference Amit and Zott2012; Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, Reference Baden-Fuller and Haefliger2013; Coombes & Nicholson, Reference Coombes and Nicholson2013; Lambert & Davidson, Reference Lambert and Davidson2013; Markides, Reference Markides2013).

Over time, academic investigation into the business model concept has seen a convergence of research relating to the fields of strategic management, technology and innovation management, and organisation (Wirtz, Göttel, & Daiser, Reference Wirtz, Göttel and Daiser2016a; Wirtz, Pistoia, Ullrich, & Göttel, Reference Wirtz, Pistoia, Ullrich and Göttel2016b). This reflects the interdisciplinary nature of business model research, which has focused on: strategy (e.g., Mitchell & Coles, Reference Mitchell and Coles2004; Shafer, Smith, & Linder, Reference Shafer, Smith and Linder2005; Afuah, Reference Afuah2009); entrepreneurship (Zott & Amit, Reference Zott and Amit2007; Fiet & Patel, Reference Fiet and Patel2008; Doganova & Eyquem-Renault, Reference Doganova and Eyquem-Renault2009); information systems (Berman, Kesterson-Townes, Marshall, & Srivathsa, Reference Birch and Whittam2012; Daas, Hurkmans, Overbeek, & Bouwman, Reference Daas, Hurkmans, Overbeek and Bouwman2013); marketing (Mason & Spring, Reference Mason and Spring2011; Mason & Mouzas, Reference Mason and Mouzas2012; Coombes & Nicholson, Reference Coombes and Nicholson2013); innovation management (Smith, Binns, & Tushman, Reference Smith, Binns and Tushman2010; Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, Reference Baden-Fuller and Haefliger2013); and international business (Casadesus-Masanell & Ricart, Reference Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart2010).

Research has also focused on identifying the conceptual foundations of the business model to help explain its operation and application (Foss & Saebi, Reference Foss and Saebi2017). This has included an activity system perspective involving the firm’s supply or value chain (Zott & Amit, Reference Zott and Amit2010), a value creation, delivery and capture perspective (Teece, Reference Teece2010), and perspectives focused on activities that can be replicated so as to sustain growth (Zook & Allen, Reference Zook and Allen2011), or applied into dynamic and uncertain markets (McGrath, Reference McGrath2010). Similar investigations were also made into the use of business models for opening up new markets and addressing poverty and human suffering (Thompson & MacMillan, Reference Thompson and MacMillan2010), as well as social and environmental sustainability (Lüdeke-Freund, Massa, Bocken, Brent, & Musango, Reference Lüdeke-Freund, Massa, Bocken, Brent and Musango2016). It is in this area that the business model concept offers the most direct potential within the field of regional economic development. This is also where the CME business model has its natural place.

Business model design and the conceptual framework

As the business model moved through its conceptual evolution, a consensus has emerged over what comprise the core components or ‘building blocks’ (Chesbrough & Rosenbloom, Reference Chesbrough and Rosenbloom2002; Osterwalder, Pigneur, & Tucci, Reference Osterwalder, Pigneur and Tucci2005; Johnson, Christensen, & Kagermann, Reference Johnson, Christensen and Kagermann2008; Teece, Reference Teece2010; Zott, Amit, & Massa, Reference Zott, Amit and Massa2011; Wirtz, Göttel, & Daiser, Reference Wirtz, Göttel and Daiser2016a; Wirtz et al., Reference Wirtz, Pistoia, Ullrich and Göttel2016b). Table 4 summarises this literature and the generally agreed building blocks of a business model.

Table 4 The building blocks of business models

An examination of these different components suggests that most recognise the business model as a strategic tool, focused on securing and sustaining a competitive advantage in the market. To achieve this the core focus is on the identification and capture of value, with an emphasis on understanding the value from the customer’s perspective. This leads to the need for the business model to make a ‘customer value proposition’, that will not only attract customers, but that can be sustainably delivered over time. Strategically this focuses the business model design around a clear ‘purpose’ that underlies the competitive strategy. Once this is defined the focus shifts to the ‘profit formula’ (i.e., cost, volume, profit analysis), and the key processes and resources needed to make the business model work. Within these areas attention needs to be given to distribution channels, customer relationships, value chain configuration, strategic partnerships, and both tangible and intangible resources.

These elements draw on a foundation of well-established strategic and marketing concepts. They have been developed into a series of conceptual tools that have become a foundation for students, teachers and practitioners seeking to design and development sustainable and resilient business models. One of these is the Business Model Generation Canvas system for business model design (Osterwalder & Pigneur, Reference Osterwalder and Pigneur2010), with books on its use by entrepreneurs (Osterwalder, Pigneur, Bernarda, & Papadakos, Reference Osterwalder, Pigneur, Bernarda and Papadakos2015).

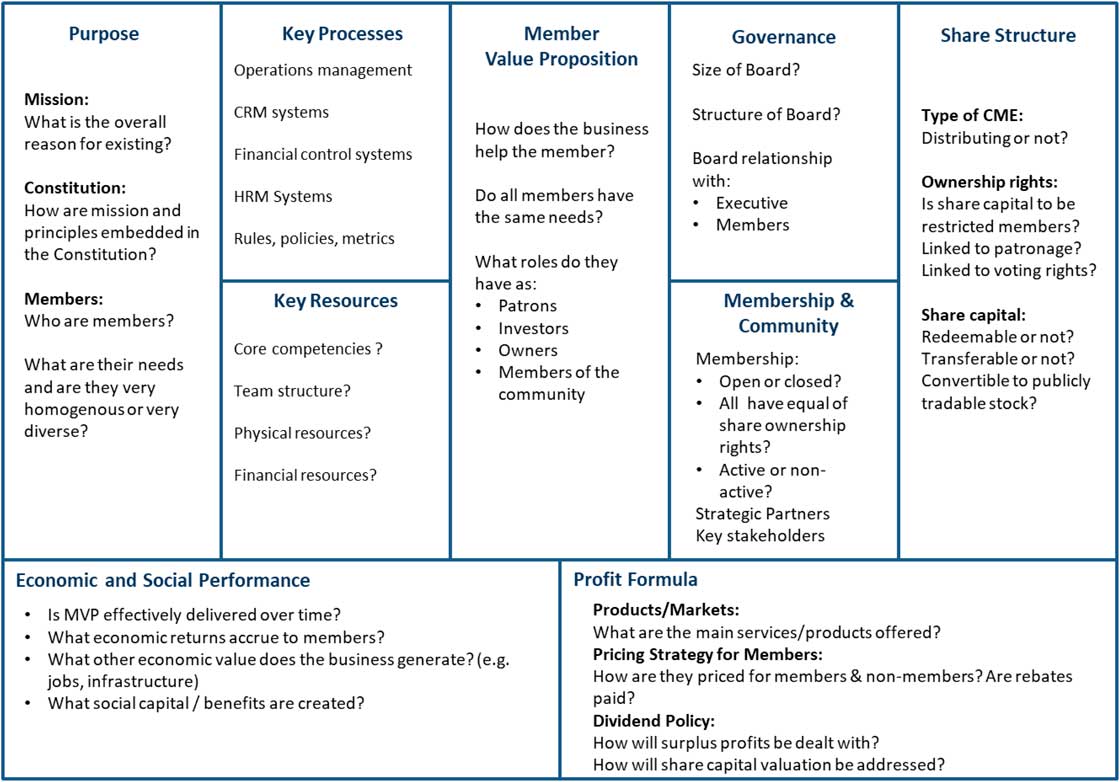

As illustrated in Figure 1, the Business Model Generation Canvas is a schematic framework that comprises nine ‘building blocks’: (i) customer segments; (ii) value proposition; (iii) channels; (iv) customer relationships; (v) revenue streams; (vi) key resources; (vii) key activities; (viii) key partnerships; and (ix) cost structure. Each ‘block’ has a series of questions that need to be addressed to help validate the model and guide strategy (Trimi & Berbegal-Mirabent, Reference Trimi and Berbegal-Mirabent2012). The ‘Business Model Generation Canvas’ has become a popular tool for start-up business ventures. This helps entrepreneurs systematically think through the nine ‘building blocks’, to identify how value is to be generated and delivered, the role of strategic alliance partners, and how the resource configuration will need to be organised so as to secure competitive advantage (Ebel, Bretschneider, & Leimeister, Reference Ebel, Bretschneider and Leimeister2016).

Figure 1 Business model generation canvas

Our analysis has found that although the components of the business model may be discussed using different terminology, or be grouped together in different ways by various authors, there is a high level of consistency in the basic building blocks of business models. This is very important for future work by both scholars and practitioners as they undertake further research on business models or implementation of the business model framework with companies (Lambert & Davidson, Reference Lambert and Davidson2013). It is also useful in helping to understand the CME business model.

CMEs as a distinct business model

An important question in the analysis of the CME business model is whether it is uniquely different from other types of business. It needs to be compared with other existing business forms such as IOF, NFPSE and SOE. The key points of differentiation are purpose, ownership, governance and funding. For example, SOEs can take a variety of forms with ownership and funding being either public, private or public–private. Governance can also be independent of government, but the influence of government on the organisation’s mission and performance metrics is usually strong (Perry & Rainey, Reference Perry and Rainey1988). The role of government also has a strong influence on the purpose of these entities, with the need to provide some element of ‘public good’ as a justification for their activities.

NFPSEs may also have a variety of ownership types, and may have membership models that engage members in its governance. Their purpose is typically focused on delivering services or benefits to the community, or specific groups (e.g., the poor, children with needs, the disabled). However, NFPSEs generally don’t recognise members as owners of the share capital, or allow them to contribute to or receive dividends, rebates or additional shares (Ridley-Duff, Reference Ridley-Duff2015). Although many CMEs are not-for-profit or ‘non-distributing’ enterprises, their ownership structures and treatment of share capital (whether or not distributed), generally differentiates them from NFPSEs (Ridley-Duff, Reference Ridley-Duff2012; Ridley-Duff & Bull, Reference Ridley-Duff and Bull2015).

Differentiating the CME from the IOF is complicated by the many organisational forms that CMEs take. For example, CMEs can be ‘non-distributing’ not-for-profit enterprises, or ‘distributing’ thereby containing a share capital structure in which shares are valued and dividends paid to members (Mamouni Limnios, Watson, Mazzarol, & Soutar, Reference Mamouni Limnios, Watson, Mazzarol and Soutar2016). However, a key difference between CMEs and IOFs is the democratic nature of their governance where the ‘one-share-one-vote’ model of the IOF is replaced with a ‘one-member-one-vote’ model (Bacchiega & de Fraja, Reference Bacchiega and de Fraja2004). Although some CMEs, particularly mutual enterprises, don’t adhere to the ‘one-member-one-vote’ principle, the inherent democracy of the CME business model is a key differentiating attribute (Apps, Reference Apps2016).

Other key differentiators between CMEs and IOFs relate to their purpose, how profits are managed, and the nature of the relationship that such firms have with their shareholders (Roy, Reference Roy1976; Staatz, Reference Staatz1987). In relation to purpose, the IOF is primarily created with the purpose of generating positive returns to its investors, which it achieves by maximising profits (Chaddad & Cook, Reference Chaddad and Cook2004; Birchall, Reference Birchall2011; Royer, Reference Royer2014a, Reference Royer2014b). By comparison, the CME’s purpose is typically focused on providing economic and social benefits to its members, usually through maximising member value through patronage and customer satisfaction (Talonen, Jussila, Saarijavi, & Rintamaki, Reference Talonen, Jussila, Saarijavi and Rintamaki2016). The purpose for which the CME was created remains its overarching raison d’être and should be its primary strategic guide. This typically has both an economic and social aspect (MacPherson, Reference MacPherson2012). Further, if the CME loses sight of its purpose it can be at risk of degeneration and demutualisation (Battilani & Schröter, Reference Battilani and Schröter2012).

In relation to profits, the focus on delivering member benefits rather than investor returns influences the way the CME board and executive management team deal with profits and profit distributions. Rather than maximising profits to provide shareholders with enhanced dividends or increasing share value, the CME is focused on increasing the total welfare of their members (Staatz, Reference Staatz1987). This might take the form of offering lower prices to consumer members, or higher prices to supplier members, even if this pricing strategy reduces the overall profitability of the CME business. Some CMEs might even choose to follow a zero-surplus strategy and generate no net profit margin if that delivers the best value to members (Helmberger & Hoos, Reference Helmberger and Hoos1962).

Within the CME, profits are reinvested in the business, and/or returned to members based upon their level of patronage, and any share capital accumulation that might occur within the CME by members is generally based on patronage (Chaddad & Cook, Reference Chaddad and Cook2004). The organisational design of the CME, particularly those with farmers or small businesses as members, has been likened to that of a ‘network form’, in which the CME as a firm, is owned in mutual by other firms (Sexton, Reference Sexton1983). This has led the CME to be described as a ‘nexus of contracts’ (Staatz, Reference Staatz1987), where the CME, despite being a separate business, is owned and controlled by its members who are also its suppliers and customers.

Condon (Reference Condon1987) explains that while the control over resources and how they are used within an IOF generally rest with the shareholders, it is the size of the shareholding that determines who has the final decision-making power. Further, strategic decisions within IOFs are usually determined on the basis of what will generate the best returns to the capital invested. By contrast, within a CME, the ownership and control rights are vested with the members who are also patrons of the business. If share ownership and voting rights are also linked to active patronage, and the CME has a ‘one-member-one-vote’ rule in place, the ownership and control rights take on a different strategic role. Strategic decisions in the CME are more likely to be made on the basis of member value rather than shareholder or investor returns. In effect, there is a value in use rather than a value in ownership dimension that differentiates the CME from the IOF business model.

Another aspect of the CME business model that differentiates it from the IOF is its focus on both the economic and social well-being of its members (Novkovic, Reference Novkovic2008). This hybrid or dual function of CMEs to simultaneously operate as a business, while also maintaining a union or alliance of members, is reflected in the co-operative principles (Fairbairn, Reference Fairbairn1994). This approach means that while the CME needs to operate effectively and efficiently to generate a financial surplus to operate sustainably, it only retains sufficient funds to continue to deliver services to members (Mooney, Roaring, & Gray, Reference Mooney, Roaring and Gray1996; Mooney, Reference Mooney2004; Levi, Reference Levi2006).

Developing a CME business model conceptual framework

To customise a business model framework for CMEs, we started by drawing upon the core components of the generic business model design and adapted them to suit the nature, activities and outcomes of CMEs. An important starting point in this process was to assess the differences that exist between CMEs and IOFs in relation to strategic decision making at the board level. Table 4 compares the two organisational types. Consistent with our earlier review of the CME versus the IOF, there are quite fundamental differences between these two types of enterprise, which link to their foundational principles and priorities.

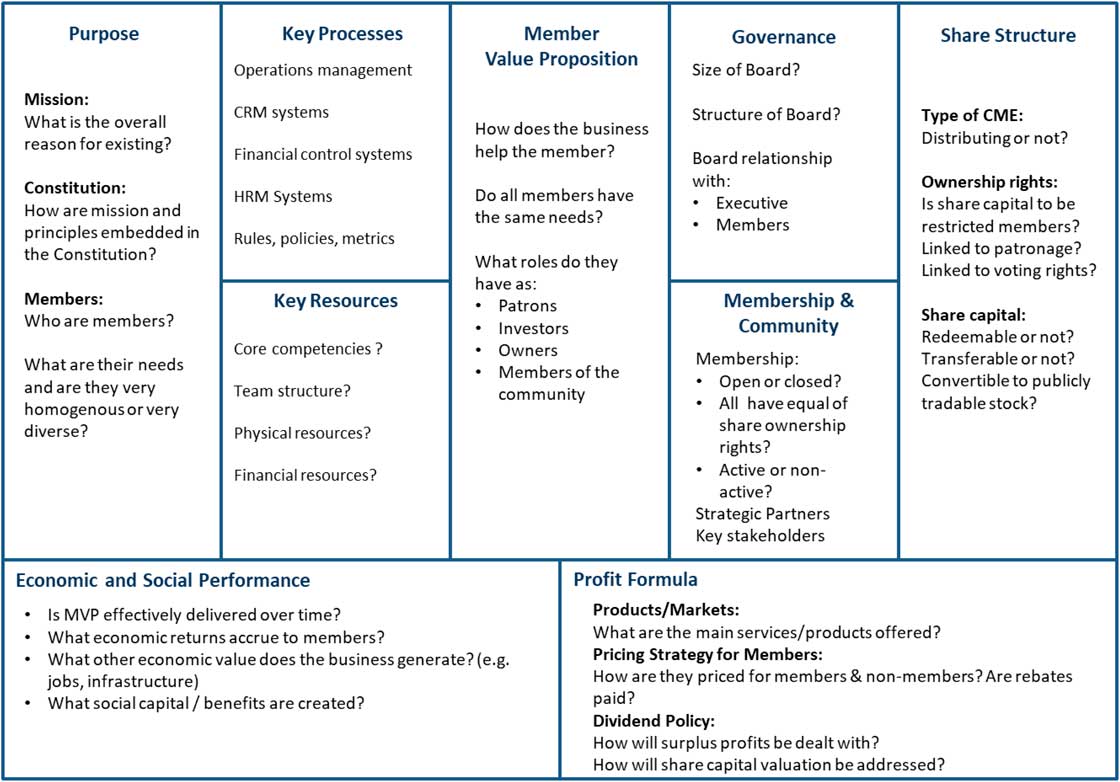

In keeping with the evolution of business model tools such as the Business Model Canvas (Osterwalder & Pigneur, Reference Osterwalder and Pigneur2010), we developed a business model canvas framework for CME business models. This is illustrated in Figure 2, where it can be seen to have nine elements – as is the case for the conventional business model canvas – but these have been adapted to the specific attributes of the CME business model. As can be seen, only three elements are similar.

Figure 2 Co-operative and mutual enterprise (CME) business model key elements

Purpose

The first element of our proposed CME business model framework is purpose, which is one of the three core pillars upon which the business model is constructed. As noted earlier, the purpose for which the CME was created guides the enterprise and is its raison d’être and primary strategic goal. It should be focused on both economic and social objectives (MacPherson, Reference MacPherson2012), and any loss of focus on the purpose can place the CME at risk of degeneration and demutualisation (Battilani & Schröter, Reference Battilani and Schröter2012). It is important to identify the CME’s purpose during its establishment as it assists with keeping the members engaged (Shah, Reference Shah1996), and in fostering shared identity and values (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Nelson, Huybrechts, Dufays, O’shea and Trasciani2016).

The purpose can be enshrined in the organisation’s constitution, along with the seven co-operative principles, to assist with decision making and ensure that the enterprise does not lose sight of its original raison d’être. This type of formalisation of purpose can become particularly important as CMEs increase in scale over time and may seek to diversify their scope. As an example of legislative requirements, under the Australian Co-operatives National Law Act of 2012 all co-operatives must adhere to the co-operative principles and are required to include a clear statement of the purpose for which the co-operative has been established:

…the primary activity or (if more than one) the primary activities taken together must form the basic purpose for which the co-operative exists and a significant contribution to the business of the co-operative; (Co-operatives National Law Act 2012 No. 29, Section 149(2)(a)).

Although this legally applies to co-operatives, many mutual enterprises in Australia are also adopting formal statements of their purpose, which are being used to guide their strategic engagement with their members and the wider community. An example of this is Bank Australia, originally a credit union founded in 1957, that became Australia’s first customer-owned mutual bank in 2011. By 2016 Bank Australia has established a strong presence in the market with 125,327 members and total assets of more than AUD $4 billion (Business Council of Co-operatives and Mutuals [BCCM], Reference Bekkum and Bijman2016). Operating in a highly competitive market Bank Australia has chosen to embrace its mutuality and its formal statement of purpose reads:

Our purpose is to create mutual prosperity for our customers in the form of positive, economic, personal, social, environmental and cultural outcomes (BCCM, Reference Bekkum and Bijman2016: 47).

As illustrated in Figure 2, the purpose encompasses the mission and the reason why the CME was established. This should be developed with an understanding of who the members are, as well as their needs. This is important because the greater the diversity of the membership base within the CME the more difficult it is to generate a common purpose (Staatz, Reference Staatz1987). This purpose can be related to the needs of a particular region or regional community, to address economic and social goals (Allemand, Brullebaut, Ditter, & Reboud, Reference Allemand, Brullebaut, Ditter and Reboud2016; Reboud, Tanguy, & Martin, Reference Reboud, Tanguy and Martin2016). Further, the purpose for which the CME was founded is usually a response to market failure, but if this purpose ceases to be relevant to members the strategic justification for the enterprise is placed at risk and potential dissolution (LeVay, Reference LeVay1983).

Many CMEs face this strategic challenge and move through a life-cycle where their own success can result in their becoming less relevant to their members’ needs and must either revise their purpose and business model, or cease to exist (Cook, Reference Cook1995). Finally, the mission or purpose statement, and the organisational values (or the co-operative principles) should be embedded into the constitution.

Member value proposition

The second major pillar in the CME business model canvas is the ‘member value proposition’ (MVP). As the CME is focussed primarily on creating value for its members, the MVP is central to the CME business model framework and it replaces the customer value proposition component found in conventional business models which focuses on target markets for specific products. Members of a CME can be either individuals (natural persons) or corporate organisations (legal persons) who are users of its services and participate in its business enterprise as consumers, workers, producers or independent business owners. Building on the CME’s purpose, an MVP can be developed that offers a combination of economic and social benefits likely to attract and retain members. This ‘co-operative value’ should be difficult to obtain from alternative business models such as IOFs (Nha, Reference Nha2006).

Talonen et al. (Reference Talonen, Jussila, Saarijavi and Rintamaki2016) suggest that customer or member value in CMEs is generated through patronage and value in use, which follows the service dominant logic theory proposed by Vargo and Lusch (Reference Vargo and Lusch2004, Reference Vargo and Lusch2008). This value can be created within the CME in various ways including: economic value (e.g., better pricing, shareholder returns); functional value (e.g., reliability, quality of service); emotional value (e.g., sense of ownership); social value (e.g., shared identity and mutual purpose) (Talonen et al., Reference Talonen, Jussila, Saarijavi and Rintamaki2016). These four attributes of potential value conform to the roles of: patron, investor, owner and member of a community of purpose proposed by Mazzarol, Simmons, Mamouni Limnios and Clark (Reference Mazzarol, Simmons, Mamouni Limnios and Clark2014).

Sexton and Iskow (Reference Sexton and Iskow1988) suggest that the foundation of the CME requires the ability to assemble as many people as possible in the common purpose for which the enterprise has been created. Early engagement of the wider community that is to form the business will help to clarify the MVP. Birchall and Simmons (Reference Birchall and Simmons2004) note that participation in a CME is contingent on the existence of shared goals, values and a sense of community or what they call the Mutual Incentives Theory.

Share structure

The third key pillar in the CME business model canvas is the design of its share structure and associated distribution of any profits. As noted earlier, this is a critical point of differentiation between the CME and IOF business models. An initial decision needs to be made in relation to dividend policy, or whether the CME is to be distributing or non-distributing. The first of these is viewed as a for-profit enterprise and issues dividends to members based on their ownership of share capital. The second type is essentially a not-for-profit enterprise and apart from rebates, will retain all profits for reinvestment into the business. This decision on the type of dividend policy the CME pursues is likely to depend on the interests and objectives of its members and the purpose for which it was established (Royer, Reference Royer2004). It is a decision that has little to do with its ability to remain competitive, and more to do with the perceived value it offers to members (Sisk, Reference Sisk1982).

Of particular importance in determining share structure is how share capital is to be managed. For example, is it to be issued only to members, and is it linked to patronage and voting rights? These decisions have strategic implications. CMEs suffer from what has been described as five generic problems that can place it at a disadvantage over IOFs, and which have their origins in the vaguely defined property rights associated with mutual ownership structures (Porter & Scully, Reference Porter and Scully1987; Cook, Reference Cook1995; Nilsson, Reference Nilsson2001). These are the: ‘Free Rider’, ‘Horizon’, ‘Portfolio’, ‘Control’ and ‘Influence-Cost’ problems.

The free rider problem is caused by members’ property rights, or share capital ownership in the CME, being insecure, unassigned or incapable of being traded. This can result in members choosing to trade with the CME only when it suits them, or to join only once the CME has been established and the early investment by pioneering members has reduced the risk. The horizon problem is caused when the member’s ownership rights via share capital cannot be transferred or liquidated via a secondary market. The pressure to force many co-operatives into demutualisation has been driven by members seeking to extract value from their ownership rights when no other option for recovery of their share capital is possible (Cook & Iliopoulos, Reference Cook and Iliopoulos1999; Fahlbeck, Reference Fahlbeck2007). The horizon problem also leads to short-term thinking within the membership of the CME because if they cannot redeem or trade their share capital, any long-term investment will not be of perceived value (Nilsson, Reference Nilsson2001).

The portfolio problem is created by the lack of transferability, liquidity and capital appreciation within the share capital structure. Further, the mutual ownership structure means that any diversification of the share capital within the CME is virtually impossible (Nilsson, Reference Nilsson2001). This results in members seeing no value in their membership and ownership of the CME other than through patronage of its services. It also sees members adopting risk averse decisions in relation to the CME because there is no perceived value in the CME undertaking investments that won’t return immediate benefits to the member via services or enhanced pricing (Cook, Reference Cook1995).

The control problem and influence-cost problem are related less to share capital structure and more to governance issues. However, the first occurs where the strategic interests of the membership and their elected representatives on the board, diverge from those of the CME’s management. This can be exacerbated by the CME losing sight of its purpose, or increasing diversity in its membership base (Staatz, Reference Staatz1987). Finally, the influence-cost problem arises from a divergence of objectives if the CME takes on too many diverse purposes and has a highly diverse membership base (Milgrom & Roberts, Reference Milgrom and Roberts1990; Storey, Basterretxea, & Salaman, Reference Storey, Basterretxea and Salaman2014).

Whether the share capital can be issued to members only, and whether it accumulates as a reward for patronage are key decisions that should be made in the design of the CME business model. Its ability to be redeemed, transferred or traded will also have significant impact on the configuration and operation of the CME, with multiple types of business models likely to be generated (Chaddad & Cook, Reference Chaddad and Cook2004).

This need to balance the often-competing interests of the investor and patron functions of the member led to the creation of New Generation Co-operatives in the United States during the 1990s (Harris, Stefanson, & Fulton, Reference Harris, Stefanson and Fulton1996). In traditional co-operatives share capital is restricted to members as patrons and while it may be redeemed at the discretion of the board, it cannot be transferred and carries no residual claims once the member ceases to be an active patron (Chaddad & Cook, Reference Chaddad and Cook2004). However, in the new generation co-operatives, share capital is closely aligned with patronage with the aim of keeping both in balance and membership is restricted rather than open. Their structure is designed to mitigate the generic problems facing traditional CME business models (Katz & Boland, Reference Katz and Boland2002).

In agricultural new generation co-operatives, members must buy stock in the co-operative to secure their patronage rights, and both the member and the co-operative are bound by contract to supply and buy the amount of produce associated with the value of the share capital purchased (Harris, Stefanson, & Fulton, Reference Harris, Stefanson and Fulton1996). Although new generation co-operatives still mostly adhere to the ‘one-member-one-vote’ principle (Carlberg, Ward, & Holcomb, Reference Carlberg, Ward and Holcomb2006), they have become quite common and many are also quite large (Skurnik, Reference Skurnik2002). However, they also demonstrate lower levels of trust between the member and the co-operative (James & Sykuta, Reference James and Sykuta2005).

Ultimately there can be many different ways for the CME to arrange its share capital, each of which has significant strategic implications (Chaddad & Cook, Reference Chaddad and Cook2004; Cook & Chaddad, Reference Cook and Chaddad2004; Bekkum & Bijman, Reference Bellman, Clark, Malcolm, Craft and Riccardi2006). Decisions relating to the final capital structure, and the cost of shares purchased in the CME, may depend on the relative value members place on their role as patrons compared to that of investors. New members might view patronage of greater value than established members (Canassa & de Moura Costa, Reference Canassa and de Moura Costa2016), suggesting that the design of any capital structure and distribution policy should be flexible and linked to the MVP.

Governance

Once the three main pillars of the CME business model (purpose, MVP and share structure) have been determined, the focus can shift to four additional building blocks that serve to link these pillars together. The first of these is governance, or the design of the CME’s corporate structure. This includes consideration of the size and structure of the board, as well as how the board will engage with its members on one side, and its executive management team on the other.

The inclusion of governance as a component in the CME business model reflects the influence of member ownership and participation on how the enterprise is governed and managed (Birchall & Simmons, Reference Birchall and Simmons2007). How the CME sets out its constitution, structures its rules and policies, and appoints its board and executive leadership team is a critical element of the business model which may influence the overall success or failure of the organisation. The design of the CME’s system of governance should consider the best interests of the members, the efficiency of the enterprise as a business and the welfare of its employees, the structure of its board and executive team, and the contribution that the organisation can make to its community (Prakash, Reference Prakash2003). In their study of the administrators’ motivations in a co-operative bank in France, Allemand et al. (Reference Allemand, Brullebaut, Ditter and Reboud2016) identified a willingness to contribute to the economic development of their region as a strong priority, coupled with conviction that being an administrator of the co-operative would serve their community.

Ideally the way the CME structures its system of governance will bring together the membership and management in a process of strong participative democracy (Chaddad & Cook, Reference Chaddad and Cook2004; Cornforth, Reference Cornforth2004; Birchall & Simmons, Reference Birchall and Simmons2007). Implementing a highly democratic approach of one-member-one vote can become difficult as CMEs increase in size, leading to representative systems such as stakeholder councils to increase participation and selection processes for board members. Under Australian co-operative law, the appointment of ‘independent directors’ (i.e., non-members) is possible so long as their numbers are not such that they outnumber the members. These appointments are typically made in order to bring outside expertise onto the board so as to enhance strategic decision making. However, it should be noted that mutual enterprises have different governance structures without the ‘one-member-one-vote’ democracy, but still with a focus on member benefits and mutuality.

Membership and community

To be successful community-based enterprises such as CMEs need to mobilise their community’s skills and find a way to unite a diverse range of individual aims into a common purpose to which all members can participate (Peredo & Chrisman, Reference Peredo and Chrisman2006). As a mutually owned enterprise it is important that the CME business model considers how it will design its relationship with its membership base. Will the membership be open or closed? Will all members have equal share ownership rights, and will membership be contingent on active patronage? These issues have been largely addressed in the previous discussion over share capital structure and governance. How the CME approaches its membership and engenders a sense of shared values, identity, trust and mutually beneficial reciprocal engagement will determine its success and sustainability (Zucker, Reference Zucker1986; Nowak & Sigmund, Reference Nowak and Sigmund2000; Leimar & Hammerstein, Reference Leimar and Hammerstein2001; Palmer, Reference Palmer2002; Pesämma, Pieper, Vinhas da Silva, Black, & Hair, Reference Pesämma, Pieper, Vinhas da Silva, Black and Hair2013; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Nelson, Huybrechts, Dufays, O’shea and Trasciani2016).

Further, as a socially focused enterprise, what will the CME seek to do with respect to its wider network of community stakeholders? Networks are important as they represent the connections between the individual CME members socially, as well as the enterprise’s relationships with key actors, such as suppliers, customers, regulatory agencies and financial institutions. This is also the opportunity for a CME to demonstrate its importance to a region and strengthen its relationships with a regional community (Allemand et al., Reference Allemand, Brullebaut, Ditter and Reboud2016; Reboud, Tanguy, & Martin, Reference Reboud, Tanguy and Martin2016). Social capital connectivity provides access to flows of information, knowledge and resources for individual co-operative members, as well as creating links to communities, and bridging gaps between diverse groups (Burt, 1997; Adler & Kwan, 2002; Peredo & Chrisman, Reference Peredo and Chrisman2006; Chiffeleau, Dreyfus, Stofer & Touzard, Reference Chiffeleau, Dreyfus, Stofer and Touzard2007).

Key resources and processes

The key resources of a CME business model, includes a consideration of the core competencies, team structure, physical and financial resources required to deliver its MVP and fulfil its strategic purpose. These may be similar to competitor IOFs, they might require specific alliances and networks due to the strategic network form that CMEs typically comprise (Gall & Schroder, Reference Gall and Schroder2006; Garcia-Perez & Garcia-Martinez, Reference Garcia-Perez and Garcia-Martinez2007; Simmons & Birchall, Reference Simmons and Birchall2008). This highlights the need for convergence between the region, the community and the development of the CME.

The key processes for a CME includes the processes to generate benefits for members such as the organisational structures, systems and activities that allow for member participation in decision making and delivering its products/services. These key operational elements of the business model will vary from business to business and be defined by the organisation’s purpose and how it seeks to create its MVP. Linked to these operational elements, there is an underlying assumption in our approach to the CME business model, that all such enterprises are essentially service businesses. Irrespective of whether they are processing milk, storing and handling grain, or dealing with financial transactions, the enterprise offers its members a service experience that may involve tangible assets as well in the delivery.

In addition, many large CMEs are key actors in supply chains. For example, producer co-operatives such as found in agricultural sectors, or retail and shared services co-operatives that have members who buy through the business rather than supply to it. There is some evidence that agricultural co-operatives can maintain strong supply chains due to their common ownership structure (Nunez-Nickel & Moyano-Fuentes, Reference Nunez-Nickel and Moyano-Fuentes2004; Katchova & Woods, Reference Katchova and Woods2011). However, their effectiveness is largely contingent on the quality of their corporate governance, the strength of member commitment and the diversity of the membership (Palmer, Reference Palmer2002).

Outputs: profits and economic and social performance

The profit formula component of the CME business model reflects the way in which the enterprise views its purpose from a financial perspective. This includes the basis of the revenue model, costs and benefits, which will be broader than for an IOF as member welfare is maximised rather than just profits (Giannakas & Fulton, Reference Giannakas and Fulton2005). Reflecting the hybrid nature of the CME, the business model framework seeks to map both economic and social performance through the generation of both economic and social capital outcomes (Fairbairn, Reference Fairbairn1994; Novkovic, Reference Novkovic2008; Neck, Brush, & Allen, Reference Neck, Brush and Allen2009). This involves an assessment of the delivery of MVP, as well as the economic value created by the enterprise and other possible benefits such as wealth, jobs and assets.

From an economic development perspective, the outputs generated by the CME can be measured in both direct and indirect effects. Direct outputs are jobs created, infrastructure built and financial benefits to members. Improving the financial position of members may involve encouraging savings (e.g., credit unions and co-operative banks), or increased prices or lower costs from collective production and marketing or procurement (e.g., agricultural producer co-operatives). Job creation can arise from increased productivity, better industrial relations and fewer dichotomies between remuneration of employees and senior managers (Bartlett, Cable, Estrin, Jones, & Smith, Reference Bartlett, Cable, Estrin, Jones and Smith1992; Kalmi, Reference Kalmi2013). CMEs may also create significant assets such as valuable infrastructure that would not have existed without them (Birchall & Simmons, Reference Birchall and Ketilson2010; Birchall, Reference Birchall2011).

However, the CME business model can also make indirect contributions to economic development. This can take the form of fostering entrepreneurship on an individual or collective level (Cook & Plunkett, Reference Cook and Plunkett2006; Peredo & Chrisman, Reference Peredo and Chrisman2006). It can also help to build up community social and economic capacity through the CME offering a potentially resilient business model (Borda-Rodriguez & Vicari, Reference Borda-Rodriguez and Vicari2013, Reference Brown, Carini, Gordon Nembhard, Hammond Ketilson, Hicks, McNamara, Novkovic, Rixon and Simmons2014), which can have positive benefits to social (Defourny & Nyssens, Reference Defourny and Nyssens2012) and environmental (Downing, Volk, & Schmidt, Reference Downing, Volk and Schmidt2005) objectives. Nevertheless, while the CME can make a strong contribution to economic development at the local level, its ability and willingness to do so will depend on the organisation’s purpose and the goals and aspirations of the community that comprises its membership (Levi & Pellegrin-Rescia, Reference Levi and Pellegrin-Rescia1997; Khumalo, Reference Khumalo2014; Kurjanska, Reference Kurjanska2015).

CMEs, the social economy and social entrepreneurship

The CME business model has been described as representing a model of ‘collective entrepreneurship’ (Cook & Plunkett, Reference Cook and Plunkett2006). The hybrid nature of the CME business model, is reflected in their dual focus on economic and social outcomes (Novkovic, Reference Novkovic2014). This positions them between the government sector SOEs and the private sector IOFs, into what has been identified as a third sector (Birch & Whittam, Reference Birchall2008). It comprises what has been labelled as the social economy, a concept that can be traced back to at least the late 19th century (Rabbeno, Reference Rabbeno1892; Rowe, Reference Rowe1893). This represents a ‘third-way’, or ‘middle path’, that seeks to achieve a balance between purely economic and purely social purposes. The values, governance and strategic purpose of the CME generally conform to the characteristics of a social enterprise (Opie, Reference Opie1929; Levi, Reference Levi2006; Hagen, Reference Hagen2007).

Although CMEs share many characteristics with NFPSE (with many CMEs being not-for-profit and charitable enterprises), through their focus on social purposes, they are also economically rational businesses that aim for self-reliance rather than dependency (Moulert & Ailenei, Reference Moulert and Ailenei2005). This has led some observers to suggest that the CME fits within a ‘fourth sector’ that is an ‘intersection between public, private and social sectors of the economy’ (Sabeti, Reference Sabeti2009). However, while this ‘fourth sector’ remains ill-defined and poorly supported by evidence (Alessandrini, Reference Alessandrini2010), the CME business model seems to play a role within the rapidly expanding domain of social entrepreneurship (Ratten & Welpe, Reference Ratten and Welpe2011; Bacq & Janssen, Reference Bacq and Janssen2011) (Table 5).

Table 5 Comparison of business decision making in co-operative and mutual enterprise (CMEs) and investor-owned firms (IOFs)

Neck, Brush, and Allen (Reference Neck, Brush and Allen2009) propose a typology of entrepreneurial ventures which is illustrated in Table 6. As shown they identify a ‘hybrid’ enterprise that encompasses both economic and social goals in its strategic purpose and overall outcomes. However, they do not relate this to CMEs, nor do they elaborate on what this type of venture might be. Based on the characteristics of the CME we have described above, it would seem logical to place the CME into this ‘hybrid’ category, which is not identical to that of the NFPSE organisations.

Table 6 Entrepreneurial venture typology

Source: Neck, Brush, and Allen (Reference Neck, Brush and Allen2009).

It is disappointing that CMEs were given no mention by Neck, Brush, and Allen (Reference Neck, Brush and Allen2009), although they were recognised by Bacq and Janssen (Reference Bacq and Janssen2011) in their examination of social entrepreneurship. Porter and Kramer’s (Reference Porter and Kramer2011) analysis of the concept of shared value and its ability to stimulate and strengthen economic and social conditions described hybrid organisations that served both economic and social purposes, blurring the boundaries between for-profit and not-for-profit enterprises. Yet they also gave no recognition to CMEs, which are acknowledged as operating on a shared value model (Talonen et al., Reference Talonen, Jussila, Saarijavi and Rintamaki2016), as well as process of shared values (i.e., trust) (Pascucci, Gardebroek, & Dries, Reference Pascucci, Gardebroek and Dries2012).

Further evidence of the tendency for entrepreneurship researchers to overlook the potential of the CME business model is the case of Shepherd and Palzelt (Reference Shepherd and Patzelt2017). In their otherwise excellent book on the future directions for entrepreneurship research, they devote an entire chapter to sustainable entrepreneurship with a focus on the importance of social entrepreneurs, the need to provide both economic and social capital outcomes to help sustain communities, as well as fostering self-sustaining, socially responsible economic development for impoverished regions. However, nowhere do they mention CMEs as potentially useful business model, nor anywhere else in the book.

This reflects a historical trend towards the marginalisation of academic research into CMEs (Kalmi, Reference Kalmi2007), which has been attributed to their ‘hybrid’ nature not fitting comfortably into either the mainstream IOF business model, or the NFPSE environment (Levi & Davis, Reference Levi and Davis2008). Although the CME business model challenges some of the assumptions of mainstream economics, it is an alternative form of organisation that has a long history of contributions to individuals, organisations and communities (Novkovic, Reference Novkovic2008; Whyman, Reference Whyman2012; Rowley & Michie, Reference Rowley and Michie2014). However, they have not been widely or routinely studied in the management sciences or core business disciplines.

We seek to address these gaps through the proposal outlined in this paper of a business model ‘Canvas’ for CMEs. This framework has been used in executive education programmes with the directors and executive managers of both small and large CMEs, with positive results that suggest the framework has both relevance and utility for practitioners. In that context, the CME business model ‘Canvas’ has assisted both large established firms and young start-up enterprises to systematically think through the logic of their business model and overall strategy.

For researchers, we seek to stimulate discussion and further investigation into the CME business model. Our business model canvas offers a potential framework for future investigation of the interactions between the nine ‘building blocks’ that comprise it, and comparisons between the CME business model and that of the IOF. One area in which the CME business model can be applied to future research is in the field of regional economic development. Relatively little use has been made of the business model concept in this area (Osterwalder, Rossi, & Dong, Reference Osterwalder, Rossi and Dong2002; Chambers & Patrocinio, Reference Chambers and Patrocinio2011). However, while business model research has been viewed as ‘an extension of strategy, not a new field’ (Massa, Tucci, & Afuah, Reference Massa, Tucci and Afuah2017: 98).

Spear (Reference Spear2000) identifies at least six reasons why the CME business model is a potentially valuable tool for regional economic development. First, the creation of a CME is an effective response when government SOE, or private sector IOF enterprises, are unable or unwilling to provide goods and services (Goddard, Boxall, & Lerohl, Reference Goddard, Boxall and Lerohl2002; Heriot & Campbell, Reference Heriot and Campbell2006; Birch & Whittam, Reference Birchall2008; Yadoo & Cruickshank, Reference Yadoo and Cruickshank2010; van Oorschot, de Hoog, van der Steen, & van Twist, Reference van Oorschot, de Hoog, van der Steen and van Twist2013). Second, due to their democratic governance and mutual ownership, they engender greater community trust than IOFs (Ole Borgen, Reference Ole Borgen2001; Hansen, Morrow, & Batista, Reference Hansen, Morrow and Batista2002; McClintock-Stoel & Sternquist, Reference McClintock-Stoel and Sternquist2004; James & Sykuta, Reference James and Sykuta2005; Rice & Lavoie, Reference Rice and Lavoie2005; Österberg & Nilsson, Reference Österberg and Nilsson2009; Pesämma et al., Reference Pesämma, Pieper, Vinhas da Silva, Black and Hair2013; Sabatini, Modena, & Tortia, Reference Sabatini, Modena and Tortia2014; Verhees, Sergaki, & Van Dijk, Reference Verhees, Sergaki and Van Dijk2015).

Third, they foster economic self-determination within the community that is free of dependence on government welfare or charity (Angelini, Di Salvo, & Ferri, Reference Angelini, Di Salvo and Ferri1998; Davis, Reference Davis2002b; Birchall, Reference Birchall2004; Holford, Aktouf, & Ebrahimi, Reference Holford, Aktouf and Ebrahimi2008; Majee & Hoyt, Reference Majee and Hoyt2011; Chaves & Monzón, Reference Chaves and Monzón2012; Phillips, Reference Phillips2012; Roelants, Hyungsik, & Terrasi, Reference Roelants, Hyungsik and Terrasi2014). Fourth, they foster and strengthen social capital thereby enhancing the underlying civil society within the community (Mutersbaugh, Reference Mutersbaugh2002; Holford, Aktouf, & Ebrahimi, Reference Holford, Aktouf and Ebrahimi2008; Simmons & Birchall, Reference Simmons and Birchall2008; Liang, Huang, Lu, & Wang, Reference Liang, Huang, Lu and Wang2015). Fifth, the co-operative principles outlined in Table 1 encourage community participation and collaboration, and thereby offer more resilient business structures (Doyon, Reference Doyon2002; Birchall, Reference Birchall2013; Sonnino & Griggs-Trevarthen, Reference Sonnino and Griggs-Trevarthen2013; Ketilson, Reference Ketilson2014; Sabatini, Modena, & Tortia, Reference Sabatini, Modena and Tortia2014).

Finally, they create ‘positive externalities’ by building up social capital, individual empowerment and community linkages (Woolcock & Narayan, Reference Woolcock and Narayan2000; Vásquez-León, Reference Vásquez-León2010; Majee & Hoyt, Reference Majee and Hoyt2011; Kalmi, Reference Kalmi2013). This enhances the overall social efficiency within the community (Puusa, Hokkila, & Varis, Reference Puusa, Hokkila and Varis2016; Martinez-Campillo & Fernandez-Santos, Reference Martinez-Campillo and Fernandez-Santos2017). Further, the structure of network relationships in CMEs is generally horizontal in nature rather than vertical, and as such it offers a potentially good foundation for effective policy initiatives (Putnam, Reference Putnam1995; Goddard, Boxall and Lerohl, Reference Goddard, Boxall and Lerohl2002; Swain, Reference Swain2003).

Conclusions

The CME business model framework outlined in this paper shows how these organisations differ from alternative organisational forms such as IOFs, SOEs and NFPSEs. It also highlights the key elements or ‘building blocks’ that should be considered when designing or redesigning the CME business model. In addressing our first research question, our analysis of the CME business model suggest that its structure should focus on the three key pillars of ‘purpose’, ‘MVP’ and ‘share structure’. This differs from the IOF business model due to the strategic importance of focusing on ‘purpose’, which should address both economic and social objectives. While both the CME and IOF business models place the creation of value at the centre of their design. The CME business model is focused on members rather than customers and as such is concerned with the member as a patron, investor, owner and member of a community of purpose.

Within IOFs the allocation and distribution of share capital is based on investment through the purchase of shares and follows procedures that are fairly well established. However, the design of share structure within the CME is more complex and can have a significant impact on the firm’s sustainability if not appropriately designed. It is for these reasons that the elements of ‘governance’ and ‘membership and community’ have replaced those of ‘customer relations’ and ‘channels’ in the CME business model framework. This reflects the centrality of the member and their engagement within a community of purpose within the CME business model. It is an important issue in addressing our second research question, and highlights the need for CME business model design to consider the need to engage the loyalty of members by balancing their often-competing roles of patron, investor, owner and community member.

The CME business model canvas provides a new template that can be used by managers, board members, and consultants to evaluate both current and future activities and performance. It can also be used to help formulate the business model design when establishing a new co-operative or mutual enterprise. This is a potentially valuable tool for practitioners that can identify and isolate the specific factors involved in organising the CME’s activities. It also provides a structure for researchers from universities and government organisations to develop case studies and do comparative research on CMEs. This CME business model framework therefore potentially contributes to future research, practice and policy.

The CME is not a solution to all economic or social problems, and it does not replace the IOF, SOE or NFPSE business models. It is also a complex enterprise to manage due to the hybrid nature of its strategic purpose, and the democratic nature of its governance. The five generic problems that confront the CME business model in its traditional form have been a cause of the demutualisation of many mutual and co-operative enterprises (Lang, Reference Lang1995; Birchall, Reference Birchall2011). For example, many co-operatives have found it difficult to adjust to market changes and increasing competition (Birchall & Simmons, Reference Birchall and Ketilson2010).

Given the dynamics of global and regional markets, organisations including CMEs need to continue to evolve and change over time. Specific challenges that are already evident for implementing the CME business model include how to handle international growth and when, or if to demutualise. The CME business model canvas offers a strategic lens through which these forces can be viewed. For example, the free rider, horizon and portfolio problems all relate to the largely economic issues of investment and patronage. Effective design of the share structure, pricing and dividend policies within the business model design can offer solutions to these issues. By contrast, the control and influence-cost problems are more of a social issue and relate to the memberships’ sense of ownership and community membership. Here the design of governance, membership and community engagement elements within the business model will offer potential solutions.

Our study has some limitations. The CME business model canvas proposed here is conceptual in nature and development from an analysis of a wide cross-section of available literature relating to this type of enterprise, and its value to economic and social development. It is therefore not without some need for further refinement. Future research will need to apply the canvas in a variety of enterprises and organisational contexts. Its application to both CMEs, and CMEs across different industries, membership types (e.g., producer or consumer owned), and jurisdictions, will also be required. Nevertheless, the business model concept has now become relevant to the field of regional economic development, and the CME business model is a potentially valuable tool for use within this context.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the Editors and reviewers of JMO for their comments.

Disclosures

The authors receive some research funding from the co-operative and mutual enterprise sector. However, this paper is not directly funded by industry.