INTRODUCTION

In comparison with Panathenaic amphorae (for which see, among others, Valavanis Reference Valavanis1986; Descat Reference Descat, Bresson and Rouillard1993; Bentz Reference Bentz1998; Tiverios Reference Tiverios, Palagia and Spetsieri-Choremi2007; Johnston Reference Johnston2007), initially produced in the sixth century bc, little ink has been spilt over their predecessor and sole Athenian trade amphora, the so-called ‘SOS’ amphora; yet their study has much to contribute to understanding commerce in the Greek Archaic period, and in particular Athenian (and other) participation in overseas trade and colonisation. The seminal work by Johnston and Jones (Reference Johnston and Jones1978) demonstrated that these vessels are capable of contributing rich information, if a concerted effort is undertaken to study them. Although a number of scholars have addressed SOS amphorae over the past 35 years, it has generally been in the context of excavation publications or as part of broader research questions (e.g. Shefton Reference Shefton and Niemeyer1982; Jones Reference Jones1986; Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas, Besios, Tziphopoulos and Kotsonas2012; Bîrzescu Reference Bîrzescu2012). An updated reappraisal of the SOS amphora on its own has yet to be produced. Indeed a great amount of information has been published since 1978, including many excavation reports from Sicily, the Italian peninsula, Iberia, northern Greece, and the Black Sea region. Consequently, the number of sites that have yielded SOS amphorae has almost tripled. Additionally, recent research on Early Iron Age amphorae may help situate the SOS amphora within a broader ceramic milieu. This article therefore aims to provide an update on our knowledge of the SOS amphora with a focus on its creation and distribution. In doing so, I hope to demonstrate how a fresh look at this ceramic shape, however brief, might contribute to existing scholarly debates on cultural interactions and mobility within the Mediterranean basin during the Archaic period.

PRODUCTION: A BRIEF SUMMARY

A short section on the production of SOS amphorae is provided here as a summary of what has already been discussed elsewhere. Johnston and Jones (Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 122–128) published the results of research including a thorough analytical project that chemically tested many SOS amphorae. That examination was followed up a short time later by Jones (Reference Jones1986, 706–712), who added to the number and breadth of samples.Footnote 1 The results of both projects were, at the same time, conclusive and complementary: SOS amphorae were produced in Attica, on Euboea (perhaps Chalcis), and within a number of western colonial settings. Specifically, two distinct chemical signatures determined without a doubt that SOS amphorae were not exclusively Athenian in origin. Although the majority of samples belonged to an Athenian group, a separate chemical signature pointed to an origin on the island of Euboea.Footnote 2 More research on Euboean SOS amphorae might allow for further classification of these vessels by site, including the location of specific workshops. Indeed, the 1969 excavations at Chalcis on Gyphtika hill uncovered a pottery deposit associated with a local workshop (as indicated by the presence of wasters) that contained hundreds of SOS amphora fragments (Johnston and Jones Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 111; Descoeudres Reference Descoeudres2006/7, 4–5, n. 10; see also Choremis Reference Choremis1971, 252 pl. 227a–b).Footnote 3

Understanding the details of Euboean production of SOS amphorae is also complicated by the similarities in the chemical signature of clay originating from the well-known settlement at Pithekoussai, located on the island of Ischia off the western coast of Italy. It is uncertain, therefore, whether the SOS samples taken from jars found at Pithekoussai were imported from Euboea or produced locally (Jones Reference Jones1986, 711). The possibility of local production of SOS amphorae on Ischia seems to be corroborated by a few examples that are morphologically different from both Athenian and Euboean types (Johnston and Jones Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 114; Di Sandro Reference Di Sandro1986, 15). These differences include a thicker vessel wall, red-brown glaze, and slightly concave neck profile (e.g. Buchner and Ridgway Reference Buchner and Ridgway1993, 478, no. 476.1). Other possible production locations for SOS amphorae include Metapontion, Sybaris, and Megara Hyblaea (Johnston and Jones Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 117, 127 n. 24, 118 n. 12; Jones Reference Jones1986, 711). All of these locations, however, have only produced a handful of vessels that could be characterised as local products, suggesting a very limited enterprise.

Stylistic classifications of SOS amphorae seem to match their chemical divisions very well – so well, in fact, that it does not seem necessary to initiate a reconsideration of the stylistic classifications discussed thoroughly by Johnston and Jones (Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 132–5). Only a brief summary will be necessary for the purposes of this paper. Over the course of 150 years, the SOS amphora varied in height between 58 and 75 cm, with an average of 68 cm for most of its existence. Maximum diameter was more stable over time and ranged between 43 and 49 cm. The height of the foot remained 3 or 4 cm, but neck plus lip height varied between 9 and 16 cm – though most stayed within the 11 to 14 cm range (Johnston and Jones Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 133). Because of the variety in size, capacity was not consistent. However, Johnston postulated a loose standardisation by potters based on simple dimensions including maximum diameter (44 cm/22 Attic fingers), height (64 cm/2 Attic feet), and neck diameter (14 cm/7 Attic fingers), with body and neck diameters related by the factor π (Johnston and Jones Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 134 n. 50, 135 n. 53; Jones Reference Jones1986, 706–7). This gives a capacity of 144.4 Attic kotylai or just over one Attic metretes (Johnston and Jones Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 135).

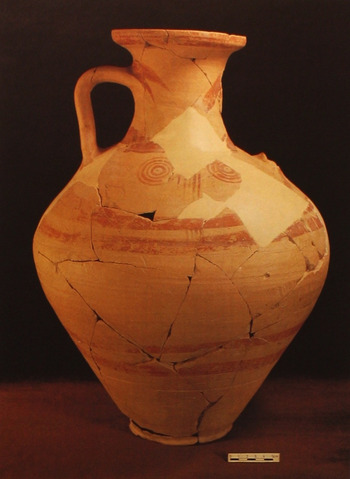

Athenian SOS amphorae have a number of defining characteristics that distinguish them from variants. Their handles are circular in section and, in later examples, their necks are flaring. The characteristic neck profile for early examples incorporates a sharp moulding under a simple vertical lip (Fig. 1a ). Over time, however, the neck became more concave with a taller and more flaring lip, which eventually became echinus- or calyx-mouthed on the latest vases (Fig. 1c ; Fig. 2b ). Other morphological characteristics include a tendency to a higher, broader greatest diameter and a flatter shoulder (Fig. 2a ). These changing morphological characteristics serve as chronological markers during the lifespan of Athenian SOS amphorae, making it relatively easy to distinguish between early and later examples.

Fig. 1. Early Athenian SOS amphorae: (a) from Athenian Agora. After Brann Reference Brann1961, no. P3 pl. 13. Reproduction courtesy of the Trustees of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens; (b) from Phaleron, tomb 47. After Young Reference Young1942, 26; (c) from Incoronata. After Pozzetti Reference Pozzetti1986, 138 pl. 37:1.

Fig. 2. Late Athenian SOS amphorae: (a) from Athenian Agora. After Brann Reference Brann1961, no. F40 pl. 80. Reproduction courtesy of the Trustees of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens; (b) from Himera. After Vassallo Reference Vassallo2003, 340 fig. 5:19.

Regarding the distinct morphology of Chalcidian SOS amphorae, this version differed from the Athenian type in a number of ways (Fig. 3). The foot is lower and more flared, the body has a higher centre of gravity, the handles are ovoid, the lip is thicker, and the neck is slightly convex (Johnston and Jones Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 133). Additionally, the lip is low, at most 4 cm high, and of varying profile with a notch rather than a ridge separating the lip from the neck (Johnston and Jones Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 111). The feet tend to be more flaring with a rounded inner contour and vary from 14.3 to 18.7 cm in diameter, though usually under 17, and range from 2.5 to 3.75 cm in height (Johnston and Jones Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 111). Chalcidian examples can also be distinguished by certain features of their decoration, including a glazed neck interior and a few distinctive neck motifs. A common Chalcidian motif consists of long double zigzags framing a circle with a large triple set of rings around two very small central rings (Fig. 3a ). Others include a spoked wheel (Fig. 3c ) and a wheel with ‘hub’ and ‘tyre’ (Fig. 3b ).

Fig. 3. Euboean SOS amphorae fragments with distinctive characteristics: (a) neck fragment with five-ring Chalcidian variety of ‘O’ framed by long double zigzags, from Morgantina, Sicily. Antonaccio Reference Antonaccio and Lomas2004, 67 fig. 3 (formerly identified as Attic, probably Euboean). Image reproduction courtesy of C. Antonaccio; (b) neck fragment with wheel with ‘hub and ‘tire’ Chalcidian variety, from Scarico Gosetti, Pithekoussai. After Di Sandro Reference Di Sandro1986, Pl. 2 no. SG 7; (c) neck fragment with eight-spoked wheel, from Torone. Paspalas Reference Paspalas, Cambitoglou, Papadopoulos and Tudor Jones2001, no. 5.30. Image reproduction courtesy of Prof. A. Cambitoglou.

THE FEATURES OF SOS AMPHORAE

The origins of the SOS amphora and its decoration are uncertain. In 1978, Johnston and Jones (Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 133) suggested, ‘it would be difficult at present to point to the origin of these details of shape, severally or as a group, or to discuss the relationship of Attic and Chalcidian shapes’. Recent developments in the study of Early Iron Age amphorae, however, may shed some light on the derivation of a number of perplexing elements of early SOS amphorae. Specifically, stylistic and morphological details of the North Aegean amphora, in use from the Protogeometric to the Late Geometric period, display some similarities to SOS amphorae (Figs. 4 and 5; for the North Aegean amphora see Catling Reference Catling1998; Lenz et al. Reference Lenz, Ruppenstein, Baumann and Catling1998; Gimatzidis Reference Gimatzidis2010, 252–69; Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas, Besios, Tziphopoulos and Kotsonas2012, 154–62: ‘Thermaic’ amphorae: Pratt Reference Pratt2014). The initial manifestation (Type I) of North Aegean amphorae dates to the Early and Middle Protogeometric periods and has been found at a few sites on Euboea (including Lefkandi) and in central Greece (Kalapodi, Elateia, Mitrou; Fig. 4). After a short gap in time when these vessels do not seem to be present in central Greece, North Aegean amphorae then became standardised in both shape and decoration (Type II; c.850 bc), and seem to be used once again at sites on Euboea and in central Greece (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4. North Aegean amphora: Type I, from Troy. Catling Reference Catling1998, pl. 1:3. Image reproduction courtesy of E. Pernicka.

Fig. 5. North Aegean amphora: Type II, from Sindos. After Gimatzidis Reference Gimatzidis2010, pl. 43 no. 361. Reproduction courtesy of Dr S. Gimatzidis.

Given the presence of North Aegean amphorae in these regions, it is perhaps possible that Euboean SOS amphorae were influenced by a number of North Aegean amphora features, not solely from neighbouring Athenian SOS amphorae.Footnote 4 These characteristics include morphological traits, like a prominent convex bulge in the neck, as well as decorative motifs. The bulge on the neck is distinctive of ‘Type II’ North Aegean amphorae.Footnote 5 By the end of the ninth century, they were produced at multiple locations around the Thermaic Gulf and shipped throughout the Aegean (Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas, Besios, Tziphopoulos and Kotsonas2012, 154–62). In terms of decoration, the characteristic ‘O’ motif on SOS amphorae also has parallels on North Aegean amphorae. Johnston and Jones (Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 136) posited that Chalcis might have adopted the circular motif on the neck before Athens. In its early manifestation, the Athenian SOS amphora more commonly used a triangular central motif, which, significantly, is also found as the central motif on smaller versions of North Aegean amphorae. When used, the type of circle motif on Athenian SOS amphorae was less complex than Euboean versions and seems to be derivative of Athenian Late Geometric motifs. Alternatively, circular motifs, and in particular concentric circle motifs, had also been used on North Aegean amphorae since their inception two hundred years before. Always located on the shoulder, these concentric circles were very often mechanically drawn, and it has been speculated that North Aegean amphorae were some of the first shapes to receive this distinctive technique (Jacob-Felsch Reference Jacob-Felsch, French and Wardle1988; Catling Reference Catling, Evely, Lemos and Sherratt1996; for the multiple-brush technique in general see Papadopoulos et al. Reference Papadopoulos, Vedder and Schreiber1998). Although concentric circles were used throughout Greece in the Geometric and Archaic periods, the parallel between these two amphora shapes is nevertheless interesting, especially when viewed in combination with other features, discussed below.

Similarities in motifs between early SOS amphorae and North Aegean amphorae continue with the vertical ‘wavy line.’ Early SOS amphorae, both Athenian and Euboean, tend to have very long vertical wavy lines on the neck (forms Sc or Sd in Johnston and Jones' typology). The long vertical wavy line seems to have been very rare on Attic vases prior to Late Geometric Ib, about the same time the SOS first appeared (Coldstream Reference Coldstream1968, 36, 180, pl. 37b–c). This same motif, however, had been present on North Aegean amphorae since the Protogeometric period, generally placed between two concentric circles (Fig. 6). The vertical wavy line motif found on SOS amphorae may indeed imitate a dribble of oil, as suggested by Johnston and Jones (Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 139), but its pedigree may derive from a contemporary transport container, such as the North Aegean amphora, rather than smaller liquid-carrying shapes, such as lekythoi (for possible contents of North Aegean amphorae see Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas, Besios, Tziphopoulos and Kotsonas2012, 162; Tiverios Reference Tiverios, Bats and D'Agostino1998, 250).

Fig. 6. Comparison of the vertical wavy line motif found on the early versions of SOS amphorae with those found on North Aegean amphorae: (a) North Aegean amphora fragment from Xeropolis, Lefkandi. After Catling Reference Catling1998, 158, fig. 2. Image reproduction courtesy of E. Pernicka; (b) SOS fragment. After Johnston and Jones Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 106, fig. 2c,d.

A final decorative motif that early SOS amphorae and North Aegean amphorae share is striped handles. Early SOS amphorae can have two or three stripes running down the length of each handle. Although not exclusive to North Aegean amphorae, this same painted design, generally accompanied by two depressed grooves, is commonly applied throughout the production of this shape. Not all early SOS amphorae have striped handles, but there are enough examples to suggest that they were not uncommon (Johnston and Jones Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 139 n. 72). It has also been observed that Euboean amphorae, more so than other versions, have striped handles if they have decorated necks (Johnston and Jones Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 138).

It is impossible to say with any certainty why these similarities exist between the North Aegean amphora and the SOS amphora. Speculatively, there could be three possibilities: a direct relation, an indirect relation, or pure coincidence. If the SOS design is directly related to the North Aegean amphora design, it necessarily would have been transmitted through direct contact between agents, such as potters or marketers, and the vessels themselves. One argument for this direct connection is that painters tend to produce designs that are in keeping with a cultural repertoire. If, therefore, a new element is introduced (in this case the vertical wavy line), then it might have come from elsewhere. North Aegean amphorae have a much longer tradition of using this motif and have been found in Attica and Euboea. This geographical and temporal overlap, when combined with the similarity in amphora shape, might suggest that the North Aegean amphora was the closest possible connection to, and inspiration for, SOS amphorae. Alternatively, the SOS design could be indirectly related to the North Aegean amphora design. In this case, both shapes would have conveyed the same meaning to consumers (quality or contents), or the potters producing these shapes were following stylistic trends of that particular koine (similar to the widespread production of ‘Euboean’ style skyphoi; see e.g. Papadopoulos Reference Papadopoulos1997, Reference Papadopoulos2011). It is also possible that the SOS design is unrelated to the North Aegean amphora design, and that the two vessels are highly similar because they were both technological innovations that fulfilled the same need (transporting bulk liquids). This idea follows Schiffer's (Reference Schiffer2011) non-adoption model for why specific technologies are used by different people in different geographical regions. In this case, the similarities between the two vessel types would be a function of their designated purpose.

In whatever manner these similar traits occurred on both shapes, it nevertheless seems possible that SOS amphorae from Chalcis shared more North Aegean amphora traits than Athenian versions. The bulgy neck, long wavy lines, ‘O’ motif and striped handles on Euboean SOS amphorae all point to a stronger connection than do the characteristics of early Athenian versions. These traits do not necessarily mean that Chalcis (or some other Euboean workshop) initially created the SOS amphora, as suggested by Gras (Reference Gras and Hackens1988, 293). Instead, these similarities may suggest that producers of the SOS amphora on Euboea had stronger connections to northern Greece, or more contact with North Aegean amphorae, and integrated some of these traits into their own products.

AN UPDATED DISTRIBUTION

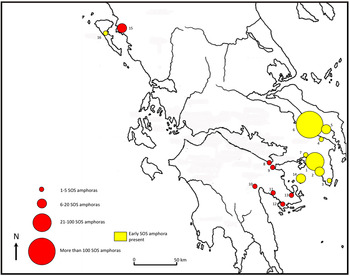

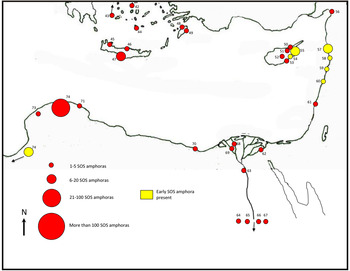

By providing an update of their distribution throughout the Mediterranean, I aim to contribute to what is known of SOS amphorae. In 1978, Johnston and Jones reported about 51 sites with at least one SOS amphora, although they noted others yet unpublished (1978, 103 n. 1). In 1982, that number had remained relatively consistent (Shefton Reference Shefton and Niemeyer1982, 340 fig. 1). Since then, however, over 140 sites have published or reported at least one SOS amphora, and that number continues to increase (Table A1 in the Appendix, Fig. 7). The repercussions of this new and greatly expanded distribution will be discussed below. In the following section I outline the number of sites represented and the volume of SOS amphorae recorded within most geographical regions around the Mediterranean (central Greece, northern Greece, Sicily, Italy, the western Mediterranean, Asia Minor/Black Sea region, eastern Mediterranean islands, and the Levant/Egypt). Where possible, care has been taken to distinguish between SOS amphorae and early examples of their successors, the so-called ‘à la brosse’ or ‘1501’ amphorae (Johnston and Jones Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 121–2; Lawall Reference Lawall and Lynch2011a, 297). This task, however, is not always possible since body sherds from both vessels are very similar.Footnote 6 Because these data are mainly based on published reports, which do not always provide full contextual, chronological, or stylistic details, we may consider this distribution a minimal figure and use it as a starting point for future discussions and analyses.

Fig. 7. Distribution map of SOS amphorae within the Mediterranean, with provenance distinguished.

Attic SOS amphora distribution

Attic SOS amphorae are found throughout the Mediterranean and can be dated from the second half of the eighth century bc to the beginning of the sixth century bc. The distribution presented here is divided chronologically between ‘early’ and ‘late’. Here, ‘early’ is defined as mid-eighth century bc to mid-seventh century bc, and ‘late’ is defined as mid-seventh century bc and later. This division is admittedly a step back from the four groupings initiated by Rizzo (Reference Rizzo1990, 16–17) but is nevertheless necessary since many published examples are too fragmentary for precise dating or are only labelled as ‘early’ or ‘late’ in the text. This brief summary of Attic SOS amphora distribution begins with their place of origin, Greece, then moves west to address first the central Mediterranean, then the western Mediterranean, followed by a discussion of their presence in the eastern Mediterranean. The summary presented here is complemented by Table A1 in the Appendix, which lists all of the sites where SOS amphorae have been found, their quantities, and associated citations.

In central Greece and the Peloponnese, SOS amphorae are found at a total of 16 sites (Fig. 8); of these, nine sites have produced examples of the early version. As perhaps could be expected, the largest group of early and late Attic SOS amphorae come from areas in and around Athens, including the Athenian Agora (44+) and the Kerameikos (13). Closer to the port, at Phaleron, 17 examples, some of which are early, have been published. Additionally, nine Attic SOS amphorae have been found on the island of Aegina in the Saronic Gulf.

Fig. 8. Distribution map of SOS amphorae in central Greece and the Peloponnese, with volumes accounted for and colour-coded for chronology.

Our information for the northern Aegean region, including ancient Macedonia and the Chalkidike, has increased dramatically in the last 30 years due to the publication of many sites with Archaic occupations. As a result, the number of sites that have yielded Attic SOS amphorae has also increased. At least one SOS amphora has been discovered at 14 sites (Fig. 9). Early versions have been discovered at three of these sites (21%). Some sites have produced relatively high concentrations of these vessels, including Methone (around 30 examples) and Karabournaki (over 10 examples, though probably many more when fully published). Most other sites have produced only a few SOS amphorae, many of which are relatively late.

Fig. 9. Distribution map of SOS amphorae in the North Aegean, with volumes accounted for and colour-coded for chronology.

The number of Attic SOS amphorae in Asia Minor and the Black Sea region remains relatively low. A total of 11 sites have produced evidence for the presence of SOS amphorae, none of which are early versions (Fig. 10). Miletos has produced the greatest number of SOS amphorae (12), followed by Old Smyrna (Bayrklı; 6). The remaining sites have produced only one example. However, there is some question as to whether the sherds belong to early ‘à la brosse’ amphorae instead, since the body sherds for both types of pots are virtually identical.

Fig. 10. Distribution map of SOS amphorae in Asia Minor and the Black Sea, with volumes accounted for and colour-coded for chronology.

Attic SOS amphorae have been reported on only five Aegean islands: Delos, Crete, Rhodes, Keos and Thera (Fig. 11). Most of these examples, however, are rather late. On the large island of Cyprus SOS amphorae have been reported on six sites, of which two have early examples (Fig. 11). Cypriot Salamis has produced at least 20 examples, some of which can be identified as early versions. Amathus too has produced 15 fragments, though it is uncertain whether they are of Attic derivation, and they could be later examples (Thalmann Reference Thalmann and Gjerstad1977, 73–4).

Fig. 11. Distribution map of SOS amphorae in the Aegean islands, Levant, Cyprus and North Coast Africa, with volumes accounted for and colour-coded for chronology.

Sites in the Levant, Egypt, and the north-central coast of Africa have also produced examples of Attic SOS amphorae (Fig. 11). A total of 19 sites have produced at least one vessel, four of which are identified as early versions (21%). The most examples that have been recorded are at Cyrene (35), Carthage (16), and Al Mina (14). Many sites in Egypt have only produced one or two SOS amphorae, all of which are later than the middle of the seventh century bc.

Interestingly, the highest concentrations of Attic SOS amphorae are not found in Greece, but in Sicily. A total of 21 sites have produced evidence for at least one Attic SOS amphora (Fig. 12). Of these 21 sites, six have produced early versions of the shape (29%). Sites with the highest concentrations of these vessels include Megara Hyblaea (over 160), Kamarina (35, late), and Syracuse (over 10), although most sites have more than a single example.

Fig. 12. Distribution map of SOS amphorae in Sicily, with volumes accounted for and colour-coded for chronology.

Similarly, 22 sites in Italy have produced at least one example of an Attic SOS amphora, seven of which have produced early versions (32%; Fig. 13). However, unlike Sicily, there are two sites that stand out as having high concentrations of these vessels. Pithekoussai has produced over 55 examples of SOS amphorae, 15 of which are certainly identified as Attic, with many others unidentified (Di Sandro Reference Di Sandro1986). Additionally, 36 SOS amphorae have been found at Cerveteri, providing one of the most complete chronological typologies outside of Athens. In most of the other published sites in Italy the presence of only one or two examples has been reported, although there is the possibility of more discoveries.

Fig. 13. Distribution map of SOS amphorae in Italy, with volumes accounted for and colour-coded for chronology.

The distribution of Attic SOS amphorae in the far west, including Iberia and the north-west coast of Africa, is similar to that in Italy, in that a total of 23 sites have produced Attic SOS amphorae, although most have very few, and early examples have been reported at only five sites (22%; Fig. 14). Two sites stand out as having relatively high concentrations for the region: Toscanos (over 11) and Mogador (over 12).

Fig. 14. Distribution map of SOS amphorae in the western Mediterranean, with volumes accounted for and colour-coded for chronology.

Euboean SOS amphora distribution

Although it is clear that regions of Euboea were producing their own versions of SOS amphorae, as discussed above, it is unclear where or in what quantity they were shipped abroad. Based on the evidence currently available, it seems that Euboean SOS amphorae remained primarily on the island but did have a limited distribution to most of the same regions where Attic versions travelled (Fig. 7). The discrepancy between the quantities of locally produced SOS amphorae found on Euboea and Euboean SOS amphorae found abroad is quite significant. At Chalcis on Euboea over 200 SOS amphorae have been found in a potter's dump, providing direct evidence for their relatively large-scale local production (Johnston and Jones Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 111). In comparison, a maximum of two Euboean SOS amphorae per site have been securely identified or published from sites in the central, western or eastern Mediterranean. This seems to suggest that Euboean SOS amphorae were not as widely exported as Athenian versions. However, since no Attic potter's dump with SOS amphorae has yet been discovered, it is impossible to state statistically that this discrepancy was limited to the Euboean version.

Because of the difficulties surrounding the identification of Euboean SOS amphorae through chemical or petrographic means, only a handful of vessels in the Mediterranean have been identified, mainly through stylistic analysis, as specifically Euboean (Fig. 7). In northern Greece Euboean SOS amphorae have been identified stylistically and by their fabric at three sites: Sindos, Methone, and Torone (Fig. 7). The Aegean islands, while they do produce evidence for Archaic Euboean pottery of other types (Descoeudres Reference Descoeudres2006/7), have yet to produce a securely identified SOS amphora. The only possibility is an SOS from Knossos, which does not seem to fit the typical Athenian standard, nor does it appear to be local (Coldstream, Macdonald and Catling Reference Coldstream, Macdonald and Catling1997, 220 no. H38). In the Levant and Egypt, a few SOS amphorae have been labelled as Euboean at Ras Al Bassit, Tyre, and perhaps one at Marsa Matruh, although this example has been reinterpreted as a Lakonian amphora (see Johnston Reference Johnston, Villing and Schlotzhauer2006a, 27–8).

The central and western Mediterranean regions have also produced a few examples. Two Euboean SOS amphorae have been identified at Pithekoussai, one from Metapontion, and a late version from Policoro, all on the basis of their decorative peculiarities. On Sicily, five sites have published at least one Euboean SOS amphora including Naxos, Syracuse, Kamarina, Morgantina and Zancle. Only one site in Iberia, Guadalhorce, has thus far produced positive evidence for Euboean SOS amphorae in the far west, again based on stylistic details.

On the basis of this limited distribution, it seems likely that Euboean SOS amphorae were never intended to transport goods off the island in large quantities, but perhaps were caught up in the export of Attic SOS amphorae abroad. The fact that all the sites where Euboean SOS amphorae are found have also produced many Attic versions, both early and late, supports this idea. The reasons for Euboean production of SOS amphorae, without their exportation in greater numbers, remain elusive.

INSCRIPTIONS AND GRAFFITI

The number of SOS amphorae found with inscriptions or graffiti has risen steadily over the last 30 years. Indeed, Johnston (Reference Johnston2004, 737) mentions 115 inscribed SOS amphorae in his database (see Johnston Reference Johnston2004, tables B, C, and nos. 175, 221 for 43 examples). A discussion of every example, however, is beyond the scope of this paper. Instead, I highlight a number of discoveries that may further our knowledge of the purpose of these graffiti during the production, distribution and consumption of SOS amphorae and their contents. Marks on SOS amphorae can be divided into three categories: owners' names in the genitive scratched post-firing, single letters that may convey content or capacity, and letters (single or longer abbreviations) or marks, which may stand for abbreviated names. The types of graffito inscriptions found on recently discovered SOS amphorae are consistent with the analyses of Johnston and Jones (Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 128–132). The language of the graffito, the type of script, whether one or two ‘hands’ has written it, where it is placed on the pot, whether it is scratched post-firing or pre-firing, and if there are parallels on other pots (SOS or otherwise), all contribute to how we interpret these graffiti.

SOS amphorae stand out from other contemporary amphorae in that they have by far the longest inscriptions on the largest percentage of inscribed pots (30% of SOS with inscriptions have four or more letters or signs; Johnston Reference Johnston2004, 738). Most of these long inscriptions are names. Names inscribed on SOS amphorae have the most potential for telling us which groups of people came into contact with these vases and at what point in the life cycle of the vases. So-called ‘owners’ names' are often written in the genitive and accompanied by the verb εἰμί, directly implying that the pot belonged to a specific person. These names introduce two problems: What role does the named person have in the trade process and who is the person writing the name on the pot? The name could be written by the producer of the pot, the filler of the pot, or a nearby middleman to ‘reserve it’ for a trader. Alternatively, the name could be written by the trader himself, thereby labelling it as his own (within a cargo-load perhaps?) or written by any ‘owner’ or consumer(s) of the pot. Although any of these options could be possible for a given name, certain characteristics concerning the graffito (language, script, hand) and its placement favour some of these options over others. Additionally, non-Greek or non-Attic Greek names written on pots can help interpret the purpose of the graffito.

An indication that these names were not necessarily written by the eventual buyer/owner or the trader comes from a long graffito written on an SOS from Kamarina on Sicily. It has an inscription around the shoulder of the vessel, one word slightly higher than the other two: ΣΜΟΡΔΟΝΟΣ/ ΣΜΟΡΔΟΝΟ EIMI, the first being a name in the genitive (ΣΜΟΡΔΟΝ in the nominative), the second translated as ‘I am Smordon's’, although here the genitive name lost its final sigma (Cordano Reference Cordano2004, 783). Both of these graffiti were written by the same hand and in Attic script, supported by the use of εἰμί rather than ἐμί.Footnote 7 However, the name is extremely rare and is not typically Greek. Johnston and Jones (Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 129) interpret the name as deriving possibly from the northern Aegean. Why the inscriber felt the need to write the name twice is unclear, although this is not a unique example. Two other cases of name repetition on SOS amphorae are known, one from Vulci with the name ΑΡΧΟΝΟΣ (Johnston and Jones Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 104 no. 2; Johnston Reference Johnston2004, 747 table C no. 48) and one from Incoronata with the abbreviated name(?) ΓΛΑΥ, possibly written in non-Attic script (Johnston Reference Johnston2004, 747 table C no. 27; Stea Reference Stea2004, 801). The name ΣΜΟΡΔΟΝΟΣ written in Attic script could be an indication of an Athenian writing a foreign name, thereby ‘reserving’ the pot for the buyer or trader, or perhaps an Attic metic writing his own name. Whether this Athenian was the potter himself or perhaps a middleman in Attica is impossible to say.

There is also some indication that these names can be written by the trader. For example, an Attic SOS amphora found at Mende in the northern Aegean was inscribed with a Cypriot graffito. This graffito is identical to an inscription on an amphora from a Policoro cemetery in Basilicata (Vokotopoulou and Christidis Reference Vokotopoulou and Christidis1995, 9). In both cases the graffito consists of a name followed by an abbreviated patronymic (te-mi) and an abbreviated ethnic (Se = Salamis). In addition, it has been suggested that three incised horizontal lines on one handle form a common Cypriot capacity potmark accounting for 10 units (Masson Reference Masson1983, 80). Salamis has the highest concentration (c.20 examples) of SOS amphorae on Cyprus, one of which was inscribed (Karageorghis and Masson Reference Karageorghis and Masson1965, 146). Whether there is a connection between the concentration of SOS amphorae at Salamis and the trader's/owner's ethnic designation on the pot found at Mende is impossible to say with certainty. It does seem, however, that a Cypriot either was an owner of the SOS, which he then resold, or was the trader responsible for its consumption in northern Greece.

An inscribed SOS amphora from Gela on Sicily provides an instance where the graffito may indicate an owner's desire to write his name on the pot after purchasing it. This particular SOS amphora was found within a room of the Archaic Temple B, dedicated to Athena, and built within a few decades of the foundation of Gela as a Greek colony (Panvini Reference Panvini and Bergemann2012, 73). On the pot was inscribed a boustrophedon graffito consisting of the name EYΘYMEO followed by EIMI, the verb spelling again suggesting Attic. However, the nominative form of this name is problematic: the dialect is Ionic, but the closest parallel to its spelling is Doric (cf. Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum XLII.868).Footnote 8 While this graffito has a very similar formula to the ΣΜΟΡΔΟΝΟ EIMI above, it is important to take into account the context of the pot. Within a cultic setting, it may have been desirable to put one's own name on the pot to acquire the symbolic capital of having provided the imported Attic oil/wine to the temple. If this is the case, then perhaps this man was a member of the newly established colony, or a transient trader who wanted to participate in the activities of the temple (see Pelagatti Reference Pelagatti2000, 185 for a similar suggestion). Alternatively, this graffito could be a remnant of the trade process and therefore unrelated to its depositional context.

These three cases suggest that names on SOS amphorae can be written at different stages in the life cycle of the pot and that the inscribing of a name does not necessarily belong to a single designated stage in the trade process. Additionally, these names hint at a complicated network of both Greek and non-Greek agents moving these vessels and their contents to both sides of the Mediterranean. While the vast majority of these longer marks on SOS amphorae can be or are written in Attic Greek, many more are found outside than inside Attica (Johnston Reference Johnston2004, 740). However, the presence of graffiti on SOS amphorae within Attica seems to support the idea that some engraving happened before the amphorae were shipped abroad, especially since other contemporary Greek amphorae rarely show this practice, displaying, inter alia, pre-firing marks (e.g. Samian; Johnston Reference Johnston2004, 746 table A). Complicating any identification of the group(s) of people whose names are written on SOS amphorae is the diverse range of names: from ‘elite’ (Archon, Eukles) to ‘servile’ names (Thorax, Myrmex, Klopetion; Johnston and Jones Reference Johnston and Jones1978, 129; Cordano Reference Cordano2004, 783–5). It can also be observed that names (or name abbreviations) range from very common Greek nomenclature (Glau, Aiscron, Eukles, Smikron), to very or relatively rare names (Smordon, Lasargades, Euthuma; see the Lexicon of Greek Personal Names s.vv.). It is tempting to speculate that this diversity in names is a consequence of the occupation within which these people participated, an occupation that perhaps allowed for social mobility or was open to a wider range of the population.

Single letters and marks inscribed on pots can also be useful tools for viewing commercial connections, either in the production or the distribution spheres. Generally, letters and marks scratched post-firing are interpreted as merchant, owner, or reuse symbols, as opposed to pre-firing or painted marks applied by the potter (Papadopoulos Reference Papadopoulos1994; Vanhove Reference Vanhove2006, 74). Unfortunately, the nature of the letters and marks makes it even more difficult to determine the identity of the inscriber. Since the range of marks found on amphorae is extremely wide, the rarity of repetition requires our careful observation when it does occur. In addition, the occasional letter written in non-Attic script on an Attic pot can be instructive.

A few marks on SOS amphorae can be labelled as ‘commercial’ with some certainty. An SOS amphora from the cemetery at Kamarina has two inscribed graffiti on its shoulder written by the same hand. The first is a typical Archaic alpha, the second is a symbol that can be described as an arrow with a perpendicular line through the shaft. Although Manni Piraino (Reference Manni Piraino1987, inv. 5498, pl. XII:5) indicates that this symbol is unique, there is an exact match on an oinochoe from Vulci, dated to 510–500 bc (Johnston Reference Johnston1979, fig. 7e, no. 2E, 6; Munich 1806, not published). That this mark occurs on both an SOS amphora and an oinochoe seems to indicate that the mark refers to commercial transactions and not to production of amphorae or their contents.

A few graffiti on SOS amphorae provide examples of non-Attic letters inscribed by, presumably, non-Attic merchants (Johnston Reference Johnston2004, 747 table C nos. 24, 27a, 28; Manni Piraino Reference Manni Piraino1987, inv. 8452). First, at Kamarina, an Attic SOS amphora was inscribed with two letters on the neck: gamma and upsilon (Manni Piraino Reference Manni Piraino1987, 93 pl. XII:1–2 inv. 3487). Although the upsilon is non-diagnostic, the gamma is non-Attic, and may instead be Ionic (Johnston and Jones Reference Johnston and Jones1978, no. 25). Interestingly, there is another graffito under the attachment of the right handle in a different hand: a cross with an additional mark off the bottom extending to the left. This mark is similar to known merchant marks of a later period (Johnston Reference Johnston1979, 85 type 32A iii [higher perpendicular line], 87 type 36A [additional line off to right]). The association of a non-Attic letter with a known merchant mark written in a different hand may indicate at least two separate transactions. Perhaps the Attic pot was sold to a non-Athenian (Ionian?) who then resold it to a merchant involved with the shipment of other products.

The second example of a possible non-Attic letter again comes from Kamarina, where an SOS was found inscribed at the base of one handle. This graffito has been interpreted by Manni Piraino (Reference Manni Piraino1987, 97, pl. XIII:5) as three letters: ΟΥΣ. The supposed upsilon, however, may in fact be a stray mark, since it is located off to the right and has a distinctive ‘v’ shape. The sigma appears to have been written with five bars, an Archaic Euboean type dated to the second half of the seventh century bc (Manni Piraino Reference Manni Piraino1987, inv. 8452, pl. XIII:5). That both this SOS amphora and the one above, each bearing different non-Attic letters, were reused as burial containers within the same cemetery is indicative of the variable use of these vessels and their status as viable commercial objects over multiple transactions.

A few other examples of probable non-Attic letters inscribed on Attic SOS amphorae are presented by Johnston (Reference Johnston2004, table C nos. 21–30), and briefly summarised here for convenience. These include an hourglass sign from Halieis, perhaps signalling Knidian script (Johnston Reference Johnston2004, 740, 747 no. 30) and an inscription (Ϝεργα) on a jar from Metauros that includes a digamma and is probably written in Euboean script (Johnston Reference Johnston2004, 740, 747 no. 28). Additionally, an SOS from Cypriot Salamis has an inscription (ΓΛΑ) that is neither Attic, nor in the local syllabic script (Johnston Reference Johnston2004, 740, no. 27a). Similarly, a later SOS found at Histria in the Black Sea region was inscribed with a Corinthian beta on its neck, another example where presumably neither the producer of the pot nor the (final) recipient wrote the graffito (Johnston Reference Johnston2004, 740, 747 no. 24). The non-Attic names and letters highlighted here act as markers for non-Greek participation in the distribution of SOS amphorae. They are, however, relatively rare compared to the number of SOS amphorae inscribed with Attic script. This aspect of SOS graffiti, that a large percentage is written in the script of the producing area, stands out among amphora types of the Archaic period. Who are the Athenians responsible for writing these names and marks on Attic amphorae, and why are some of these examples found within Athens itself? The relatively large number of SOS amphorae with long ‘owners’ inscriptions' makes these pots stand out from their contemporaries, perhaps suggesting that SOS amphorae were regarded somewhat differently. Indeed, ‘owners’ inscriptions' are far more common on fine ware vessels and dedicatory objects than on storage and transport containers. Perhaps writing a person's name on an SOS amphora was an attempted to increase the (perceived) value of the pot and its contents. These different attributes of SOS graffiti suggest that one must consider critically the status of SOS amphorae and their interactions with non-Greeks alongside Athenian producers, merchants, and owners.

Finally, it may be useful to discuss briefly the graffiti evidence that has been variously interpreted as indicating contents of SOS amphorae. Graffiti scratched post-firing onto a visible area of an amphora could be interpreted as a sign of reuse, perhaps pointing to a new content different from the original (Vanhove Reference Vanhove2006, 74). Alternatively, the application of a graffito indicating the specific content of the vessel may be an initial action (and not reuse) to separate the vessel from others that might have carried the ‘normal’ or ‘usual’ commodity. It is also possible, though not regularly attested, that a graffito might indicate normal content. In the case of SOS amphorae, it is generally assumed that they carried Attic olive oil (Gras Reference Gras1987; Baccarin Reference Baccarin1990; Descat Reference Descat, Bresson and Rouillard1993; Brun Reference Brun2003). There is some evidence, however, that SOS amphorae might have also (or exclusively? See Lund Reference Lund, Eiring and Lund2004, 213–14) contained wine (Docter Reference Docter1991; see Moore Reference Moore2011, 5 for a summary of arguments). The argument for wine is based primarily on iconographic evidence, most notably the François krater, which depicts Dionysos carrying an amphora with ‘SOS’ marked on its neck. Johnston (Reference Johnston, Villing and Schlotzhauer2006a, 28) rightly points out that while this evidence is important, one must not overlook the Corinthian A amphora, a popular contemporary of SOS amphorae. The view that Corinthian A amphorae held oil is based on the porosity of their fabric, and its similarity to that of contemporary lekythoi and lamps, which suggests, at least, that oil was a product in high demand (Koehler Reference Koehler1981, 452; Whitbread Reference Whitbread1995, 257).

If the following interpretations of them are accepted, graffiti on three SOS amphorae from Pithecussae might indicate that these vessels could carry, or were redeployed for, other commodities. One was inscribed with the word λεῖα, perhaps interpreted as ‘sweet wine’ (Bartonek and Buchner Reference Bartonek and Buchner1995, 170 no. 2; although see Johnston Reference Johnston2006b, 164 no. 8 for a different interpretation of this word). Another graffito, λι[- -], was interpreted as perhaps λί[πος], the word for ‘fat’ (Bartonek and Buchner Reference Bartonek and Buchner1995, 170 no. 29), although this reconstruction is highly speculative. A third SOS amphora was inscribed with hα, interpreted as ἅ(λς), ‘salt’ (Bartonek and Buchner Reference Bartonek and Buchner1995, 171 no. 30; Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas, Besios, Tziphopoulos and Kotsonas2012, 194). In addition, an SOS amphora was found at the south necropolis of Megara Hyblaea with ΟΞΑ inscribed on its neck, perhaps for ὄξος, translated as ‘vinegar’ (Gras Reference Gras1987, 47–9; De Angelis Reference De Angelis2003, 97 n. 155; Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas, Besios, Tziphopoulos and Kotsonas2012, 194). All of these interpretations of content, however, are based on reconstructed words with few parallels on contemporary or later amphorae (Papadopoulos and Paspalas Reference Papadopoulos and Paspalas1999, 171–2; Lawall Reference Lawall, Tzochev, Stoyanov and Bozkova2011b). Indeed, future research using residue analysis might help to elucidate this question of SOS amphora contents.

OBSERVATIONS

Regarding the distribution of these vessels, and by proxy the commodities within, it is now possible to reinvestigate some earlier theories that addressed chronological trends of SOS amphorae and the specific actors involved with their transport.

Based on data available at the time, it had been proposed (e.g. Shefton Reference Shefton and Niemeyer1982) that chronological trends were visible in the distribution of SOS amphorae. In this scenario, earlier SOS amphorae were confined to specific regions, namely the Near East, the central Mediterranean (specifically Pithecoussai and Cerveteri) and (in very small numbers) the western Mediterranean (e.g. Mogador; Cébeillac-Gervasoni Reference Cébeillac-Gervasoni1982, 204; Shefton Reference Shefton and Niemeyer1982, 341). Only later versions were distributed widely in Iberia, Sicily and the North Aegean. Current evidence, however, suggests that this chronological division is not clearly demarcated (Fig. 15). The only regions that have failed to produce early Attic SOS amphorae are Asia Minor and the Black Sea, as well as the non-Saronic Peloponnese. Instead, the presence and quantity of early SOS amphorae in the west, at least, seems to coincide with the distance of the site from their production location (Attica and Euboea). For example, the regions of the western Mediterranean, Sicily, and Italy have around the same number of sites producing SOS amphorae (23, 21, 22 respectively). However, the number of sites with early SOS amphorae appears to decrease as we move west, at least based on the evidence currently available. Seven sites on the Italian peninsula (32%), six sites on Sicily (29%), and five sites in the western Mediterranean (22%) have early SOS amphorae. The Levant and the North Coast of Africa follow a similar pattern, with four out of nineteen sites (21%) producing early versions of SOS amphorae. Interestingly, this pattern does not seem to depend upon the presence of many Greek colonies in the region (i.e. Iberia, Levant, Egypt).

Fig. 15. Distribution map of early SOS amphorae within the Mediterranean

In addition, it seems that quite a few sites imported SOS amphorae and their contents over a relatively long period of time. Although the absolute numbers of vessels recorded at many sites in the Mediterranean are not large (e.g. one to five), it is significant that many sites have different versions. In other words, even if only three SOS amphorae were found at a site, but they span a century (based on morphological traits or context), then it is possible this site had been receiving commodities by way of SOS amphorae for a long period of time. Of course, it is also necessary to take into consideration reuse when SOS amphorae from a broad time span are found in the same context. This, however, is not always the case. Instead, the pattern might suggest that the presence of multiple SOS amphorae at a particular site does not represent a single importation event. Rather, these amphorae may have accumulated over time in a series of interactions, most likely incorporated into different economic networks, and maintained by various actors.

Megara Hyblaea is a unique example, since the site has produced one of the highest volumes of SOS amphorae.Footnote 9 Indeed, SOS amphorae comprise about 90% (159 out of 166) of the imported amphorae down until 580 bc, when the SOS stopped being produced. The Attic amphorae imported after this time (sc. the à la brosse) are both less numerous and more varied in types (85 total including one Panathenaic; De Angelis Reference De Angelis2003, 93). This large quantity provides an opportunity to see patterns of SOS amphora importation over time. Rather than all amphorae appearing during a single moment in time, the distribution of SOS amphorae at the site takes place over almost 150 years. Within that 150-year period, however, there is certainly an era of increased volume. Specifically, there were five SOS amphorae imported during 750–700 bc, none during 700–650, 154 during 650–600 bc, and only two during 600–575 bc (De Angelis Reference De Angelis2003, 93 fig. 33). This example demonstrates not only the long duration of SOS amphora distribution from its place(s) of origin, but also the wave-like pattern of the quantity of SOS amphorae during this time period. It is also important to recognise that SOS amphorae did not necessarily represent a minority of the imported amphorae at a given site, especially in the Early Archaic period.Footnote 10 Indeed, the volume and distribution of SOS amphorae abroad is particularly intriguing because Athens did not have any colonies.

The updated distribution of SOS amphorae provided here also presents an opportunity to re-examine previous suggestions for possible groups or actors involved with the transport of these vessels. Specifically, in his evaluation of SOS amphora distribution, Brian Shefton (Reference Shefton and Niemeyer1982) had posited that Phoenicians might have been heavily involved with the distribution of these Greek vessels throughout the Mediterranean.Footnote 11 Aside from the fact that many sites in Iberia received Greek SOS amphorae before any direct Greek presence, Shefton convincingly demonstrated a connection between the find-spots of early Attic SOS amphorae, early Corinthian aryballoi, and Phoenician enterprise, particularly in Iberia. Based on these distributions, he suggested that in the early part of the Archaic period Phoenicians were the primary movers of Attic SOS amphorae, along with most other Greek goods (for Phoenician distribution of Corinthian pottery see Morris and Papadopoulos Reference Morris, Papadopoulos, Rolle, Schmidt and Docter1998). He went on to suggest that perhaps Pithekoussai, as a settlement with both Greek and Phoenician actors, served as a trans-shipment point (Shefton Reference Shefton and Niemeyer1982, 342).

The expanded SOS distribution provided here continues to support this idea of Phoenician involvement. First, a number of additional Phoenician colonies have produced SOS amphorae, including the well-known sites of Carthage and Motya, as well as many Phoenician colonies in Iberia, such as Toscanos, Guadalhorce, Aljaraque, Gadir, Malaga, Algarroba and Cerro del Villar. Second, a greater number of indigenous Iberian sites, which seem to have had mainly Phoenician contacts in the Early Archaic period, have also produced SOS amphorae (Fig. 12; Gonzales de Canales, Serrano and Llompart Reference Gonzales de Canales, Serrano and Llompart2006, 15). Third, SOS amphorae are found at more sites that show connections to Phoenician trading ventures, including Cerveteri, Veii, Vulci in Etruria, and Methone in northern Greece (see Turfa Reference Turfa1977; Boardman Reference Boardman2001, 38–40; Brody Reference Brody2002, 77; Kasseri Reference Kasseri, Kefalidou and Tsiafaki2012). Finally, new research on the distribution of eighth-century Phoenician ‘torpedo’ amphorae provides an interesting parallel to early SOS amphora distribution (Kasseri Reference Kasseri, Kefalidou and Tsiafaki2012, 307 fig. 3). The distribution of these early Phoenician containers corresponds very closely to the locations of early SOS amphorae. Specifically, eighth-century torpedo amphorae have been found at 14 sites, 7 of which have also produced early SOS amphorae (Doña Blanca, Morro de Mezquitilla, Toscanos, Methone, Pithekoussai, Cypriot Salamis, and Carthage; Kasseri Reference Kasseri, Kefalidou and Tsiafaki2012, 307 fig. 3; Adam-Veleni and Stefani Reference Adam-Veleni and Stefani2012, 161–2, nos. 109–11). Of the remaining seven sites with torpedo amphorae, five are located on the Levantine coast. The lack of SOS amphorae at these sites is not surprising, and in fact supports Phoenician involvement, since traders would have travelled from these places towards Greece, where they would then acquire SOS amphorae.

Additionally, Phoenician presence on Ischia and at Pithekoussai has been further elaborated upon since Shefton's publication. Evidence now suggests that the island was populated by both Greeks and Phoenicians. Particularly striking evidence is a Greek amphora with both Aramaic and Greek graffiti (Garbini Reference Garbini1978; Ridgway Reference Ridgway1992, 112–14; Bartonek and Buchner Reference Bartonek and Buchner1995, 187) found reused for an enchytrismos burial (although the total number of Aramaic or Phoenician inscriptions is not large; Bartonek and Buchner Reference Bartonek and Buchner1995, 187–89). While this site seems to be neither a Phoenician nor a Greek ‘colony’, there is little doubt that both groups interacted with each other and with local populations (Papadopoulos Reference Papadopoulos2001, 443; Kelley Reference Kelley2012, 246 with relevant references). That so many SOS amphorae have been recovered from both the settlements and necropoleis on Ischia attests to a vigorous trade, use, and reuse of these vessels. With this confluence of actors and practices in mind, it is quite possible that Pithekoussai functioned as some sort of trans-shipment point, as Shefton argued, to sites both near and far.

CONCLUSION

The observations discussed here pave the way for further research on Athenian/Phoenician involvement with overseas trade, traders and colonisation. Continued elaboration of the chronological and geographical patterns associated with SOS amphorae might elucidate specific connections between Attica and colonial enterprises westward.Footnote 12 Other insights into the complex web of trade networks in the Early Archaic period may also be generated through comparisons between the distribution of SOS amphorae provided here and distributions of other key commodities, such as metals or amphorae from other regions. Recent emphasis on North Aegean amphorae has already brought to light interesting parallels with SOS amphorae, discussed above, perhaps alluding to some deeper connection that could potentially be clarified with future research. Hence, the many questions introduced by this updated synthesis of the production and distribution of SOS amphorae provide an intriguing glimpse into the intricacies of commercial interconnections at the very outset of the Archaic period.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Dr Alan W. Johnston for his support and guidance concerning the research presented in this article. Thanks are also due to Dr John McK. Camp II for permission to examine the SOS amphorae from the excavations of the Athenian Agora, as well as Sylvie Dumont for her help gathering the materials. I am also grateful to Dr John K. Papadopoulos and Dr Sarah P. Morris for their constructive comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

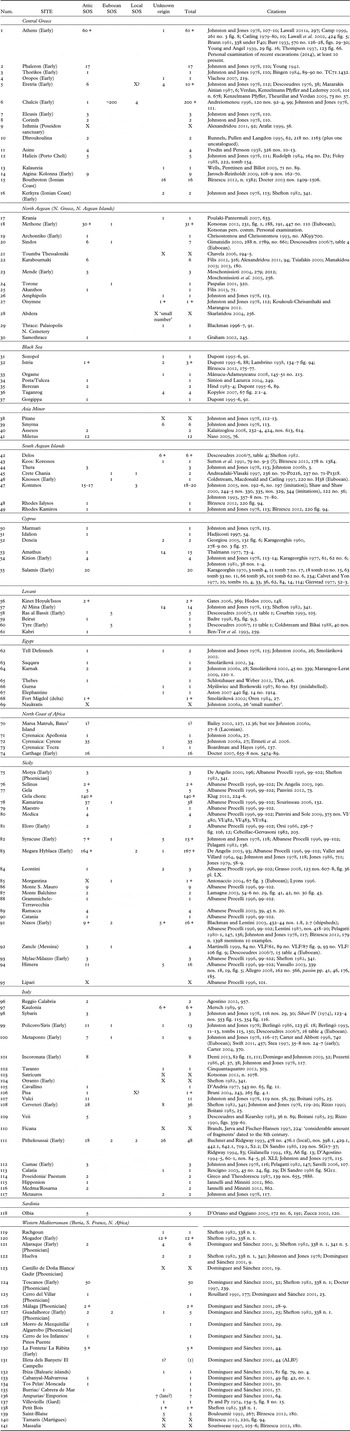

APPENDIX

Table A1. SOS amphora distribution by site (X = SOS amphora mentioned, but not identified in detail).